Abstract

Although recovery from borderline personality disorder (BPD) is common, not all individuals improve over time. This study sought to examine the features that contribute to response or non‐response for individuals at different stages of recovery from BPD over a longitudinal follow‐up. Participants were individuals with a diagnosis of BPD that were followed up after 1 year of receiving psychological treatment. There were no significant differences between participants at intake across key indices; however, at 1‐year follow‐up, two groups were distinguishable as either ‘functioning well’ (n = 23) or ‘functioning poorly’ (n = 25) based on symptomatology and functional impairment. Participant qualitative responses were analysed thematically and via Leximancer content analysis. Thematic analysis indicated three key themes: (1) love of self and others, (2) making a contribution through work and study and (3) stability in daily life. Participants who were ‘functioning well’ described meaningful relationships with others, enjoyment in vocation, and described less frequent or manageable life crises. The ‘functioning poorly’ group described relationship conflicts, vocational challenges, feelings of aimlessness and purposelessness, instability in daily living and frequent crises. Leximancer content analysis visually depicted these divergent thematic nomological networks. Corroborating quantitative analyses indicated significant differences between these groups for social, occupational and symptom profiles. These findings highlight the centrality of achieving the capacity to ‘love and work’ in fostering a sense of personal recovery. Treatments may need specific focus on these factors, as they appeared to reinforce symptomatic trajectories of either improvement or poor non‐response to therapy.

BACKGROUND

Lived experiences of borderline personality disorder

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a complex and challenging mental illness, often characterised by significant psychosocial impairment and high service use (Lewis et al., 2018). Recent studies show individuals with BPD are over‐represented in mental health care settings, representing up to 12% of outpatients, about a quarter of inpatients and almost 30% of forensic patients (Black et al., 2007; Ellison et al., 2018; Lewis et al., 2018). Mortality rates are also significantly higher than the general population, with up to 10% of patients dying by suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Like other mental illnesses, much of the personality disorders literature focuses on diagnosis, symptoms and treatment outcomes, with a smaller number of studies focusing on the experiences of individuals with BPD (Ng, Carter, et al., 2019). With the increasing interest in recovery, the study of the lived experience of BPD is critical to progressing the field. To date, the small body of qualitative literature exploring the experiences and perspectives of people with BPD have focused on life histories and trauma (Holm et al., 2009), daily life (Spodenkiewicz et al., 2013) experience of the BPD diagnosis (Courtney & Makinen, 2016; Horn et al., 2007; Sulzer et al., 2016), service user perspectives (Fallon, 2003; Morris et al., 2014; Ng et al., 2020; Redding et al., 2017; Rogers & Acton, 2012; Rogers & Dunne, 2011; Stapleton & Wright, 2017) and more recently the emerging area of recovery (Gillard et al., 2015; Holm & Severinsson, 2011; Katsakou & Pistrang, 2017; Lariviere et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2016; Ng, Carter, et al., 2019; Ng, Townsend, et al., 2019). However, few studies have explored the lived experiences and perspectives of individuals with who are at different stages of recovery to understand some of factors that may contribute to outcomes. Central to this understanding is the contributions of ‘love and work’. As Tolstoy argues, ‘One can live magnificently in this world if one knows how to work and how to love, to work for the person one loves and to love one's work’ (Troyat, 1967). For individuals with BPD, difficulties in relationship and vocational functioning often feature in their lives (Miller et al., 2018).

The field of personality disorder has evolved considerably, particularly with the growing body of evidence for improved health professional attitudes (Day et al., 2018) (albeit stigma still remains; Ring & Lawn, 2019), as well as the development and availability of evidence‐based treatments (Bateman et al., 2015) and improved treatment trajectories (Biskin, 2015). Yet at present about a half do not respond to current treatment after about a year of therapy (Woodbridge, Reis, et al., 2021; Woodbridge, Townsend, et al., 2021). Thus, a more nuanced contemporary understanding of the lived experience of BPD is required.

The current study

More often than not, the daily struggles of individuals with BPD extend beyond the experience of symptoms. Meta‐synthesis studies of individuals living with serious mental illness show relationship and occupational functioning are often impaired, and similarly many people who live with serious mental illness have difficulty meeting their basic needs, such as access to adequate physical care, and maintaining stability in finances and living situations (Kaite et al., 2015; Zolnierek, 2011). These factors are related to an individual's symptom severity and presentation, quality of life (QOL) and opportunity for recovery. With the growing emphasis on recovery‐oriented care, particularly in the BPD literature and practice, recognition of the difficulties in daily life is critical to offering a more holistic and person‐centred approach to treatment. The current mixed methods study aims to undertake a longitudinal follow‐up to compare and contrast lived experiences of individuals living with BPD who are at two different stages of recovery to discover some of the factors associated with their differential outcomes.

This study aims to explore the lived experiences of individuals who are functioning well, compared with those who are not. With consideration of the relevant literature (e.g., Zanarini et al., 2018) and in consultation with clinicians experienced in BPD, a set of criteria were developed to classify participants into two groups based on level of functioning.

METHOD

Procedure

Participants were individuals with BPD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) seeking treatment at their local mental health service. Prior to entry into the study, patients underwent a structured comprehensive assessment and clinical diagnosis by trained mental health clinicians using a standard protocol (New South Wales Department of Health, 2001). Patients flowed through a stepped model of care (Grenyer, 2014), described elsewhere (Grenyer, 2013; Grenyer et al., 2018). Briefly, the initial intake diagnostic interview (usually in acute settings) was generally followed by referral to a personality disorders brief intervention clinic designed to plan care (Project Air Strategy for Personality Disorders, 2015). At the brief intervention clinic, patients were invited to participate in the study and provided written informed consent following institutional review board and hospital site approval. Patients were then referred to longer term psychological therapy in a public, private or not‐for‐profit non‐government community mental health setting as indicated (Huxley et al., 2019). Participants were interviewed in the community after 1 year by a trained researcher psychologist, separate from the mental health service.

The interview at 1‐year follow‐up was semi‐structured and included a combination of open‐ended questions and questionnaires. Specifically, participants were asked to give an open response to the following questions: ‘I'd like you to talk to me for a few minutes about your life at the moment—the good things and the bad—what is it like for you?’, and ‘Who is the main person supporting you at the moment, what sort of person are they, and how do you get along together?’. The interviewer gave prompts (e.g., ‘What about the good things’, ‘what about the bad things?’, and ‘can you give me an example’). These are standardised questions routinely administered as part of a content analysis paradigm (e.g., White & Grenyer, 1999). Content analysis is the systematic analysis and interpretation of verbal content, based on the assumption that the nature of individuals' psychological states is contained within their language, and implies a representational or descriptive model of language (rather than a purely functional model) (Viney, 1983). Content analysis methodology has demonstrated reliability and validity (Viney, 1986; Viney & Westbrook, 1986).

Measures

BPD symptom severity

The severity of the nine DSM‐5 symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) were rated (1 = none of the time, 6 = all of the time) to provide a dimensional understanding of symptom experience (Clarke & Kuhl, 2014). Internal consistency of this approach was excellent (α = 0.90). Validity was demonstrated in previous studies of process–outcome (Hashworth et al., 2021; Huxley et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2018; Woodbridge, Reis, et al., 2021). The McLean Screening Instrument (MSI) (Zanarini et al., 2003) cut‐off of 7 was used to group participants as described below.

The Mental Health Index‐5 (MHI‐5)

The MHI‐5 is a five‐item questionnaire from the Short Form‐36 (SF‐36) used to assess severity of psychological distress (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). Each question assesses one aspect of mental health: depression, anxiety, positive affect, loss of behavioural/emotional control and psychological wellbeing. The MHI‐5 demonstrates good internal consistency with studies reporting Cronbach's alpha between 0.74 and 0.83 (Cuijpers et al., 2009; Rumpf et al., 2001; Strand et al., 2003), as well as good sensitivity and specificity (0.83 and 0.78, respectively) (Rumpf et al., 2001). In our sample, internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.86).

The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHO‐QOL)

We used a brief global item from the WHO‐QOL to assess QOL (‘how would you rate your quality of life?’; WHOQOL Group, 1998), which has been used extensively and demonstrated good reliability, and construct validity in psychiatric populations, including personality disorder (Trompenaars et al., 2005).

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)

The GAF is a clinician‐rated scale, widely used to evaluate the psychological, social and occupational functioning on a scale of 1 to 100, where lower scores indicate poor functioning and higher scores indicate good functioning (Startup et al., 2002).

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule

Items H2 and H3 of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO‐DAS 2.0) were used in the present study to measure occupational functioning, as the WHODAS2 is sensitive to change when measuring function (Lenzenweger et al., 2007). Item H2 asks: ‘in the past 14 days, how many days were you totally unable to carry out your usual activities or work because of any health condition?’ Item H3 asks: ‘not counting the days that you were totally unable, for how many days did you cut back or reduce your usual activities or work?’ These items are frequently used in studies investigating impinged vocational function (Keeley et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2018).

Developed recovery item

One item was developed in order to understand participants' subjective view of their personal recovery at follow‐up. This question was asked, ‘Please rate how much you think you have improved?’ on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is very much worse, 5 is no change and 10 is very much better.

Thematic analysis

NVivo

Semi‐structured interviews were transcribed and then qualitatively analysed to explore the everyday experiences of individuals with BPD. Thematic analysis was used in this study to identify and explore patterns of meaning in the dataset (Braun et al., 2019). Using an inductive approach to analysis, the authors familiarised themselves with the data by re‐reading the responses multiple times. Data were initially free coded, and free codes were then grouped into emergent themes and subthemes using thematic analysis in QSR NVivo, Version 11 (QSR International, 2015). These codes were discussed, reviewed and agreed upon by the research team. Following this, a second researcher independently coded 20% (n = 12) of the transcripts against the list of identified themes. Cohen's Kappa coefficient was used to indicate the level of agreement between the two researchers, overall and for each theme. The overall inter‐rater reliability coefficient was calculated as κ = 0.73, indicating substantial agreement (Viera & Garrett, 2015), and κ = 0.5–0.92 for identified themes, indicating moderate to almost perfect agreement (Viera & Garrett, 2015). A total of 371 node expressions were coded from transcripts. To allow comparison of experiences for those functioning well and those functioning poorly, NVivo attributes were assigned to each case, and subsequently, responses for each group were compared. Transcripts coded varied from 113 to 1204 words (M = 428.88, SD = 244.37) with the average number of words slightly lower for the functioning poorly group (M = 421.44, SD = 282.99) than the functioning well group (M = 434.87, SD = 200.29).

Leximancer

Participant responses were then analysed via qualitative data software Leximancer, Version 5 (Smith, 2021). Leximancer is a computer‐assisted content analysis program used to explore and identify semantic relationships depicted by a visual map that relates concepts from the text. Generated output consists of maps relating to identified qualitative ‘themes’ and ‘concepts’. The software analyses text responses according to an inbuilt word‐based dictionary. During analysis, concepts are formed comprising groupings of word and word‐like instances within a two‐sentence parameter. This includes the combination of words that are similar (e.g., ‘friend’ and ‘friends’) in conjunction with frequently co‐occurring words (e.g., ‘friend’ and ‘happy’). Words that are not relevant to the analysis or words with a low semantic meaning (e.g., ‘um’ and ‘yeah’) were removed from analysis. The resulting concepts are depicted as dots in the map whereby the proximity of any two concept dots represent their relatedness and the size of a concept dot represents its frequency. Themes, on the other hand, reflect superordinate clusters of identified concepts within the text. The use of Leximancer in this analysis serves two main functions. First, it serves to provide a visualisation of the identified themes, to both summarise and aid interpretation of qualitative findings presented. Second, it serves to provide an ancillary analysis to corroborate or contrast the findings of the thematic analysis (via NVivo). While NVivo relies heavily on researcher interpretation (increasing risk of bias), Leximancer is a largely automated analysis that reduces researcher influence (but also limits the process of meaning making). As such, the use of both approaches in conjunction serves to address the limitations of either used in isolation (Sotiriadou & Brouwers, 2014). Leximancer has demonstrated reliability and validity (Smith & Humphreys, 2006), with utility in research designs thematically comparing between groups (Day et al., 2018).

Allocation to groups

Individuals were allocated to the group functioning well group if they met all four criteria at 12‐month follow‐up: (1) scored 71 or above on the GAF (Zanarini et al., 2018); (2) scored below the recommended clinical cut‐offs for the MSI‐BPD (Zanarini et al., 2018) and (3) the MHI‐5 (Berwick et al., 1991); and (4) scored high on the global QOL rating. A GAF score of 60 or below was considered to be an indicator of poor functioning, as were scores above the recommended clinical cut‐offs for the MSI‐BPD and MHI‐5, and low scores on the global QOL rating. Table 1 provides more detail on these criteria. Participants classified in each group met all the corresponding criteria, and those who did not meet criteria for either group were excluded from the analysis.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion criteria for allocation to two groups based on 1‐year follow‐up functioning

| Functioning well | Functioning poorly |

|---|---|

| GAF score of 71 or higher. | GAF score of 60 or below. |

| GAF scores within this range suggest ‘if symptoms are present, they are transient and expectable reactions to psychosocial stressors; no more than slight impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning’ and have been used in other large‐scale studies as a measure of ‘excellent’ recovery (Zanarini et al., 2018). |

GAF scores ranging between 51 and 60 indicate ‘moderate symptoms’ or ‘moderate difficulty in social, occupational or school functioning’. Thus, anything that falls at or below this range indicate moderate to more severe symptoms. |

| + | + |

| Score below 16 on the MHI‐5. | Score of 16 or above on the MHI‐5. |

| Scores in this range are indicative that ‘caseness’ for major psychological distress is unlikely (Berwick et al., 1991). | Scores in this range are indicative of ‘caseness’ for major psychological distress (Berwick et al., 1991). |

| + | + |

|

Score below 7 on the MSI‐BPD. Scores in this range indicate they do not meet the recommended clinical cut‐off for BPD (Zanarini et al., 2003). |

Score of 7 or above on the MSI‐BPD. Scores in this range indicate they meet the recommended clinical cut‐off for BPD (Zanarini et al., 2003). |

| + | + |

| ‘Good’ or ‘very good’ on the WHO‐QOL. | ‘Bad’ or ‘very bad’ on the WHO‐QOL. |

| Scores in this category are the highest ratings of quality of life. | Scores in this category are the lowest ratings of quality of life. |

Abbreviations: BPD, borderline personality disorder; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; MHI‐5, Mental Health Index‐5; MSI‐BPD, McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder; WHO‐QOL, World Health Organization Quality of Life.

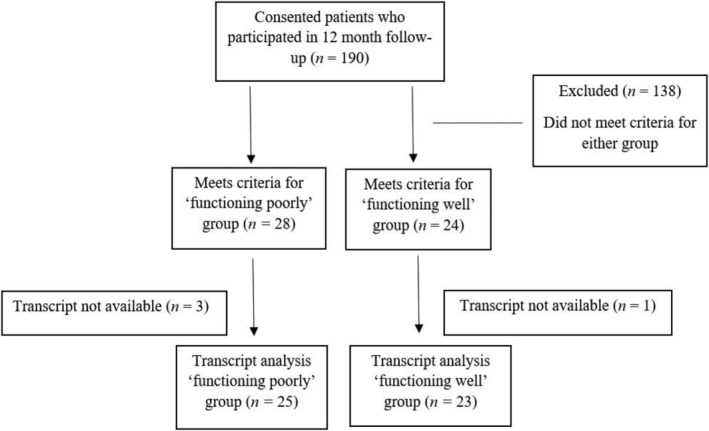

A total of 190 individuals gave consent and participated in both the intake and 12‐month follow‐up interview. When the criteria in Table 1 were applied to the sample, 24 (12.6%) met the ‘functioning well’ criteria, and 28 (14.7%) met the ‘functioning poorly’ criteria. The remaining 138 did not meet criteria for either group and were excluded from the analysis. Similarly, audio recordings were not available for four participants meeting criteria; thus, these participants were also excluded from the qualitative analysis (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of participants meeting inclusion criteria (total n = 48)

RESULTS

Changes over time: Social and occupational functioning

Table 2 presents participant characteristics at intake. There were no significant differences between the two groups for demographics (age and gender), occupational functioning or social supports at intake.

TABLE 2.

Participant characteristics (intake)

| Functioning well (n = 24) | Functioning poorly (n = 28) | t|χ 2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 32.13 (14.01) | 31.14 (13.97) | −0.251 | 0.80 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 8 | 3 | 2.27 | 0.13 | |

| Female | 16 | 25 | 1.98 | 0.16 | |

| Employment (SD) | |||||

| Days unable to do work or activities | 4.33 (5.35) | 6.35 (5.49) | 1.34 | 0.19 | |

| Days cut‐back work or activities | 5.08 (5.59) | 5.35 (5.27) | 0.18 | 0.86 | |

| Main support person | |||||

| Friend/family/partner | 18 | 16 | 0.12 | 0.73 | |

| None, or professional support only | 6 | 12 | 2 | 0.16 | |

Table 3 presents participant characteristics at 1‐year follow‐up. At 1‐year follow‐up, there were significant differences between groups for occupational functioning and social supports. Additional questions were also asked at this follow‐up regarding living arrangements, as well as employment and relationship status. Overall, at 1‐year follow‐up, participants in the ‘functioning poorly’ group demonstrated significantly lower employment and occupational functioning and had significantly lower meaningful social connections.

TABLE 3.

Participant characteristics (1‐year follow‐up)

| Functioning well (n = 24) | Functioning poorly (n = 28) | t|χ 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment (SD) | ||||

| Days unable to do work or activities | 0.5 (1.06) | 5.57 (4.26) | 5.64 | 0.001* |

| Days cut‐back work or activities | 0.75 (2.47) | 4.39 (3.96) | 3.90 | 0.001* |

| Main support person | ||||

| Friend/family/partner | 23 | 15 | 1.68 | 0.19 |

| None, or professional support only | 1 | 13 | 10.29 | 0.001* |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| With others | 19 | 13 | 1.13 | 0.29 |

| Alone, or alone with children | 5 | 15 | 5 | 0.03* |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 13 | 5 | 3.57 | 0.06 |

| Not employed | 11 | 23 | 4.24 | 0.04* |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Single (incl separated) | 9 | 20 | 4.17 | 0.04* |

| Married/defacto/in relationship | 15 | 8 | 2.13 | 0.14 |

Significant at <0.05.

While significant differences were observed for work functioning and social supports between groups (‘functioning well’ vs. ‘functioning poorly’) at 1‐year follow‐up, significant differences were also observed within groups over time. That is, compared with intake scores, the ‘functioning well’ group at 1‐year follow‐up had significantly less days unable to work, t(23) = 3.32, p = 0.003, 95% confidence interval (CI) [1.43, 6.15], d = 0.68, and significantly less days cut‐back work, t(23) = 3.24, p = 0.004, 95% CI [1.57, 7.09], d = 0.66. No such differences were significant for the ‘functioning poorly’ group from intake to follow‐up.

Changes over time: Clinical characteristics and personal recovery

At intake, all participants who participated in the study completed a brief manualised intervention for personality disorders at their local health clinic following a stepped care model of service delivery (Grenyer, 2014). This intervention focuses on identifying and managing risk and psychoeducation, identifying goals and values and promoting self‐care and support networks (see Project Air Strategy for Personality Disorders, 2015, for more details). Table 4 describes what kinds of supports participants were receiving at follow‐up; however, as this was a naturalistic longitudinal follow‐up, the content of individual treatments was not controlled. Differences were not significant between groups for participants receiving more intensive treatments (i.e., psychotherapy and psychiatry consultation) or those receiving more generalised care (i.e., case management, physician appointments and support groups).

TABLE 4.

Participant current clinical supports (1‐year follow‐up)

| Functioning well | Functioning poorly | χ 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive treatment | ||||

| Psychotherapist/psychiatrist | 75% | 100% | 1.46 | 0.23 |

| General care | ||||

| Case manager/physician/support group | 36% | 42% | 1.39 | 0.24 |

Analysis was conducted exploring changes to participant clinical characteristics over time for each group; these results are presented in Table 5. Those allocated to the ‘functioning poorly’ group at follow‐up had also shown little improvement in functioning (i.e., BPD severity, mental health and QOL) after 1 year based on their intake scores. The ‘functioning well’ group, however, had significant improvement across all clinical indices compared with their intake scores.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of clinical characteristics at intake and 1‐year follow‐up

| Measure | Group | Response range | Intake | Follow‐up | df | t | p | 95% CI | Effect size d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPD severity | ||||||||||

| Arguments or breakup | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 3.62 | 1.21 | 20 | 6.05 | <0.001 | [1.56, 3.20] | 1.32* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 4.15 | 3.54 | 25 | 1.34 | 0.19 | [−0.27, 1.27] | 0.26 | ||

| Self‐harm or suicidality | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 20 | 2.09 | 0.04 | [0.00, 0.67] | 0.46* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 2.73 | 1.41 | 24 | 3.52 | 0.002 | [0.48, 1.84] | 0.70* | ||

| Impulsivity | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 3.29 | 1.67 | 20 | 4.26 | <0.001 | [0.80, 2.34] | 0.93* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 4.08 | 4.36 | 25 | −1.20 | 0.24 | [−1.15, 0.30] | −0.24 | ||

| Moody | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 3.62 | 1.67 | 20 | 6.97 | <0.001 | [1.37, 2.54] | 1.52* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 3.92 | 4.43 | 25 | −1.35 | 0.19 | [−1.07, 0.22] | −0.26 | ||

| Angry | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 3.19 | 1.54 | 20 | 4.84 | <0.001 | [0.92, 2.32] | 1.06* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 4.23 | 3.29 | 25 | 3.48 | 0.002 | [0.38, 1.47] | 0.68* | ||

| Distrustful | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 3.48 | 2.09 | 19 | 4.27 | <0.001 | [0.76, 2.23] | 0.95* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 4.77 | 4.46 | 25 | 0.75 | 0.46 | [−0.54, 1.15] | 0.15 | ||

| Unreal | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 2.57 | 1.13 | 20 | 3.93 | 0.001 | [0.69, 2.26] | 0.86* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 3.24 | 3.21 | 24 | 0.10 | 0.92 | [−0.79, 0.87] | 0.02 | ||

| Empty | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 3.67 | 1.17 | 20 | 8.10 | <0.001 | [1.84, 3.11] | 1.77* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 4.85 | 4.75 | 25 | −0.33 | 0.75 | [−0.56, 0.41] | −0.06 | ||

| No identity | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 2.67 | 1.17 | 20 | 4.13 | 0.001 | [0.75, 2.29] | 0.90* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 4.19 | 4.57 | 25 | −1.46 | 0.16 | [−1.02, 0.17] | −0.29 | ||

| Abandonment | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 3.14 | 1.08 | 20 | 5.77 | <0.001 | [1.31, 2.79] | 1.26* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 3.96 | 4.14 | 24 | −0.55 | 0.59 | [−1.14, 0.66] | −0.11 | ||

| Average score | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 3.06 | 1.37 | 20 | 8.36 | <0.001 | [1.27, 2.11] | 1.82* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 4.02 | 3.83 | 25 | .97 | 0.34 | [−0.16, 0.46] | 0.19 | ||

| MHI‐5 | ||||||||||

| Average score | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 1–6 | 4.09 | 1.95 | 20 | 11.81 | <0.001 | [1.80, 2.58] | 2.58* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 1–6 | 4.83 | 4.56 | 25 | 1.18 | 0.25 | [−0.17, 0.65] | 0.23 | ||

| QOL | ||||||||||

| Average score | ||||||||||

| Functioning well | 0–100 | 45.71 | 82.08 | 20 | −6.17 | <0.001 | [−49.70, −24.58] | −1.35* | ||

| Functioning poorly | 0–100 | 30.39 | 41.07 | 25 | −1.91 | 0.07 | [−19.99, 0.76] | −0.37 | ||

Abbreviations: BPD, borderline personality disorder; CI, confidence interval; MHI‐5, Mental Health Index‐5; QOL, quality of life.

Significant at <0.05.

Follow‐up scores were also significantly different between the two groups for all clinical characteristics, including average BPD severity scores, t(50) = 17, p = 0.001, 95% CI [2.17, 2.75], d = 4.73; MHI‐5 scores, t(50) = 15.6, p = 0.001, 95% CI [2.27, 2.94], d = 4.34; and QOL, t(50) = 9.65, p = 0.001, 95% CI [32.48, 49.55], d = 2.69. Participants were also asked at follow‐up if they personally felt that they had ‘improved’ since their initial presentation at the health service. At 1‐year follow‐up, there was a significant difference between participants' conception of their personal recovery between the ‘functioning poorly’ group (M = 6.70, SD = 1.71) and the ‘functioning well’ group (M = 8.75, SD = 1.62), t(49) = 4.38, p = 0.001, 95% CI [1.11, 2.99], d = 1.22.

Associations between occupational and clinical features

Correlation analysis was conducted for all continuous variables under examination including clinical characteristics (QOL, MHI, MSI and self‐rated ‘improvement’) and occupational functioning (days unable to work and days cut‐back work). With the exception of days unable to work and days cut‐back work, all variables were highly significant (p < 0.001). Correlations are presented in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Correlation matrix of clinical characteristics and occupational functioning

| QOL | MHI | MSI | Days unable to work | Days cut‐back work | Self‐rated ‘improvement’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QOL | 1 | −0.84* | −0.76* | −0.58* | −0.49* | 0.56* |

| MHI | ‐ | 1 | 0.88* | 0.60* | 0.55* | −0.64* |

| MSI | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | 0.63* | 0.50* | −0.52* |

| Days unable to work | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | 0.07 | −0.41* |

| Days cut‐back work | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 | −0.46* |

| Self‐rated ‘improvement’ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 |

Abbreviations: MHI, Mental Health Index; MSI, McLean Screening Instrument; QOL, quality of life.

Significant at <0.05.

Qualitative results

Inductive coding identified three overarching themes across the dataset: (1) love of self and others; (2) making a contribution through work and study; and (3) stability in daily life. Patterns in the experiences of each group (functioning well and functioning poorly) are described in relation to these themes.

-

1.

Love of self and others

Functioning well

This group tended to speak more positively about their relationships with others and expressed satisfaction with that aspect of their lives; for example, ‘we have just celebrated our sixth wedding anniversary on the weekend, so that—that part of my life is really—really good’. Another participant stated: ‘We've been together 11 years and he's sort of stuck through me … he's been to my psychologist a couple of times and my psychiatrist with me. And he knows how to calm me down.’

A number of individuals emphasised how being a parent was an important part of their lives. One father stated: ‘They know that I love them, I see them constantly, they are in constant contact with me, so that's good.’ A new mother shares: ‘I just feel, like, really happy since I've got my son. … It's just ever since I've had him I just feel really good about myself. And I feel like I'm going to start getting somewhere in life because I have this little baby that's depending on me. … I'm motivated to do it now.’

Individuals who were functioning well tended to report on importance of longer term relationships that provided support and understanding: ‘I know we have been friends for so many years so we have been like best friends for over six years … I do not have any sisters so [she's like] the sister I never had.’ While individuals in this group did also speak about relationship troubles, there seemed to be a greater sense of acceptance of this experience. For example, ‘I've just come through a separation with my husband, and we are in an area where we, you know, speak really nicely to one another.’

Individuals who were functioning well also spoke more positively about themselves; for example, ‘I think my self‐esteem's come back. My self‐esteem, self‐worth is intact. Uh, my confidence level has improved. Um, I'm happier with who I am’ and ‘I feel like I have not leaned on anyone for quite a while or burdened anyone with any of my personal emotional statuses. I feel very self‐supported, at the moment.’

Functioning poorly

While individuals in this group spoke about some positive romantic and family relationships, they tended to mostly report instability and discontent with their relationships; for example, ‘I've just sort of ended a relationship with my partner after 12 years, which was very, um, toxic, so that's a bit hard to deal with at the moment … I continue, sort of, to ring him and chase him sort of thing, and I know I should not.’

This group also spoke more often about feelings isolation and lacking support. For instance, ‘I'm just living on my own and I'm struggling. And my friends are, like, half an hour away, and I'm struggling to not, like, have my friends around me all the time.’ Several participants could only identify one person in their life that is important to them (e.g., ‘I mostly only talk to my partner, I do not really socialise’), and some individuals could not identify anyone other than their treating clinicians or their pets.

Finally, several participants described their relationships mainly involving other people who were similarly struggling with illness. For instance, ‘my boyfriend also has his own mental health problems so that leads to complications in the relationship and in life in general’ and ‘I have friends who were sick as well—who were sick like me. And that proved very problematic.’

-

2.

Making a contribution through work and study

Functioning well

Study and work, both paid and voluntary, were also frequently referenced by this group. One individual shared: ‘I'm really happy, been busy at work … I've got a job overseas and I move in January, so that's pretty exciting.’ While another individual stated: ‘I'm now one of the committee members of [corporation X]. … I feel quite successful.’

Other participants also echoed the sense of meaningful contribution that they derived from working (e.g., ‘[I work] about 10 hours a week with kids and I love it. Um, the pay's not great, it's, um, a logistical nightmare [at times] … but for my—my self‐esteem it's absolutely worth it.’).

Functioning poorly

Although several people in this group expressed satisfaction and content in their work or study (e.g., ‘work is going quite nicely’, and ‘I've got a great job’), others expressed their struggles with maintaining work or keeping up with study. For example, one individual described their capacity to maintain their study commitments due to the ongoing struggles with their mental health: ‘Ah, sometimes I cannot get to class because I'm not feeling up to leaving the house. If I do come in there's a lot of social anxiety, um, that affects my performance in the classroom, um, and then also just going on top of the workload and getting assignments in and that kind of thing.’

A common experience of this group was the feeling of ‘just getting by’, or the experience of just living ‘day by day’ that lacked a sense of purpose. Several individuals gave examples of feeling unmotivated. For example, one individual states: ‘basically I just hide in my house, on my computer, watching TV … I just do not want to go out anywhere out there. I just want to stay home.’ Similarly, another individual speaks of a similar experience: ‘I just sit around a lot of the time just being upset.’

-

3.

Stability in everyday life

Functioning well

This group spoke less frequently about current traumatic life events; however, when they did, they tended to display greater acceptance and coping. For example, one individual spoke about current relationship and financial burdens: ‘I have just recently engaged a solicitor to deal with the breakup of the mortgage … yeah, I would not even say it's a negative, it's just something that needs to be done.’

Many did report that overall their lives were more stable and this supported their independence and self‐esteem. One individual shared: ‘I've got a roof over my head. I am working, I am studying.’

Several spoke of feeling this stability in their lives supported them to be ready to return to work: ‘I enjoy being with my kids and I enjoy my family; I have good connections with them and some good friendships with people outside of my family as well. And I do volunteer things, like I volunteer, sometimes at our church, for example, like, help run a playgroup and that sort of thing so, help people out here and there. I am ready to almost think about starting to go back to work.’

Functioning poorly

This group spoke about crisis events as current, or recently occurring. For example, ‘I just found out on Thursday that my ex‐boyfriend is having a baby to my best friend … two or three weeks ago I tried taking my own life … I had like two hospital admissions.’ Another individual shared the challenges involving multiple complications, such as deaths in the family, feeling rejected by others, financial challenges and utility disputes, exclaiming ‘oh, could anything go right?’

Difficulties in housing and finance were also evident in other narratives of this group; for example, ‘Everything is going pretty bad. We're trying to find a place to move, and I cannot seem to find a place, because no‐one wants to rent this place and all that. And just all the finances are really stressing me out.’

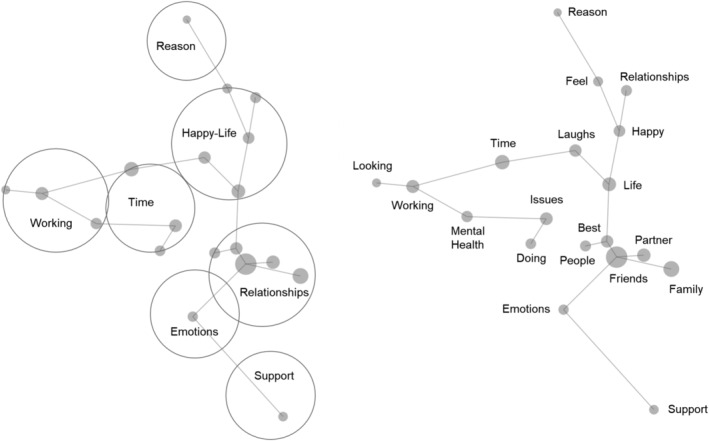

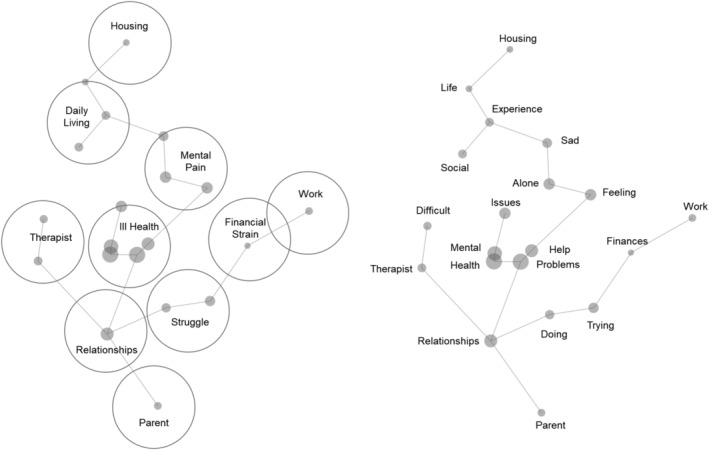

THEMATIC ANALYSIS OF WORD ASSOCIATIONS USING LEXIMANCER

Figures 2 and 3 visually depict the different patterns of participant qualitative responses for either ‘functioning well’ or ‘functioning poorly’ groups. The ‘functioning well’ group shows a nested theme of having diverse relationships (e.g., friends, partners and family), which are related to themes of life being good, emotional support, wellbeing and meaningful vocation. The ‘functioning poorly’ group included manifest issues relating to ill‐health and mental pain (e.g., feeling alone and sad). There were nested themes relating to issues of daily living, such as unstable housing and occupation, as well as impoverished relationships, typically only involving immediate family (e.g., parents) or professionals (e.g., therapist).

FIGURE 2.

‘Functioning well’ qualitative map of participant responses. Showing both clustered overarching themes (left) and individual concepts (right)

FIGURE 3.

‘Functioning poorly’ qualitative map of participant responses. Showing both clustered overarching themes (left) and individual concepts (right)

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the significant divergence in life functioning in patients after a year of psychotherapy who are functioning well or poorly. In recent years, there has been an increased focus on investigating personality disorder recovery (e.g., Zanarini et al., 2018). However, most studies focus on symptom reduction which may not correspond to a sense of personal recovery for individuals with a lived experience of BPD (Katsakou & Pistrang, 2017; Ng et al., 2016). Lived experience perspectives have significantly advanced the field in understanding recovery from BPD (Gillard et al., 2015; Lariviere et al., 2015), highlighting the need for a therapeutic focus on fostering agency, occupational functioning, improving relationships and sense of self (Ng, Townsend, et al., 2019). Our results support these perspectives, with participants who were ‘functioning well’ not only having symptomatic reduction but also elements that constitute a personal recovery and engagement in a life worth living. As such, while challenges remain regarding effective treatment for patients who display a prolonged illness of severe duration (as demonstrated by the ‘functioning poorly’ group), our results also serve to promote hope and optimism to replace therapeutic nihilism (Grenyer, 2013) with the ‘functioning well’ group demonstrating a robust improvement across multiple indices. Importantly, while the two groups were identified and distinguished after a 1‐year follow‐up, at intake, the two groups were approximately equivalent to each other in symptomatology and functioning. That is, at intake, both the ‘functioning well’ and ‘functioning poorly’ groups had high occupational impairment, limited social connections and high BPD and mental health symptomatology. At follow‐up, the ‘functioning well’ group not only demonstrated significant improvement compared with the ‘functioning poorly’ group but also showed significant improvements when compared with their own intake scores. This increases confidence that this group has genuinely achieved ‘recovery’, further evidenced by the high proportion of participants in this group who rated themselves as ‘very much better’ in regard to their subjective sense of recovery from BPD.

Our findings demonstrated a strong convergence between the thematic analysis, content analysis and quantitative analysis. Themes highlighted in the thematic analysis (through NVivo) emphasised how respondents doing well described more stable functioning and good interpersonal relationships and feelings of self‐worth, and consequent improvements in work and study. For these participants, the content analysis (through Leximancer) showed high proximity and frequency of words indicating emotional support and relationships, and working time and positive mental health. Quantitative scores mirrored these in higher self‐reported QOL and lower relationship problems or abandonment fears over the 12 months. Conversely, the doing poorly group showed qualitative themes of isolation and relationship breakup, and being insecure in housing and finances. Leximancer maps for this group plotted relationships between mental health challenges and problems in daily living, and quantitative findings showed more enduring self‐reported emptiness, distrust and mental health symptoms over the 12‐month period. Using multiple tools of analysis can thus show both unique aspects influencing recovery and concordance in the challenges affecting outcomes.

Increasingly, dominant diagnostic and classification systems are moving towards classification of personality within a spectrum of severity (e.g., personality functioning, American Psychiatric Association, 2013; personality organisation, Lingiardi & McWilliams, 2017; and personality severity, World Health Organization, 2019). While there currently exists a number of effective and evidence‐based treatments for personality disorder (Bateman et al., 2015), a subgroup of patients remain unwell despite therapeutic intervention (Woodbridge, Reis, et al., 2021; Woodbridge, Townsend, et al., 2021). As reflected by the ‘functioning poorly’ group, our results highlight a group of severely unwell patients with unique challenges. This group appear locked in cycles of mutually re‐enforcing internal and external dysfunction, consistent with research highlighting difficulties in meeting basic needs (e.g., adequate physical care, stable finances and housing) for individuals with severe illness (Kaite et al., 2015; Zolnierek, 2011). Such patients exhibit a lack of autonomy, feelings of emptiness, prominent emotion dysregulation, a view of life as meaninglessness, interpersonal chaos and difficulty maintaining long‐term relationships (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Lingiardi & McWilliams, 2017). As such, these results point to the need for a specific focus on the development of tailored therapeutic interventions for patients with severe presentations, focusing on issues of daily living and interpersonal relationships.

Clinical implications

A number of implications are apparent from the current research regarding the treatment of personality disorders. Beyond that which have already been mentioned (e.g., extending conceptions of recovery beyond symptomatic improvement and the need for tailored treatments for severe presentations), a clear clinical implication is the need for the treatment to extend outside of the one‐on‐one clinical encounter. That is, treatment of personality disorders must involve factors of ‘real life’ beyond the individual, such as social functioning, occupational (i.e., work, study and volunteering) and issues of daily living (i.e., finances and housing). Some treatments have an explicit focus on these external factors, through engaging in a collaborative discussion with the patient regarding their treatment goals and ‘contracting’ a joint agreement regarding the patient's active engagement in the areas of social and occupational functioning (Clarkin et al., 2006). Other approaches include linking the patient with ancillary support services (e.g., housing, social groups and disability support) in combination with a treatment focusing more specifically on symptom reduction. Some authors have suggested that as personality severity increases, there is a greater need to engage ancillary supports as the patient is less able to muster internal resources to stabilise functioning in various domains (Kernberg, 2008), which appears consistent with our results. However, a fine balance needs to be struck between providing supports to help the patient achieve independence and avoiding inadvertently maintaining factors that prolong illness via secondary gain (Caligor et al., 2015). This challenge was discussed by a participant in our study, who said ‘whilst I continue to work full time, I become ineligible for every single service under the sun, so basically, the way our system works is I have to collapse everything to be able to get the support I need’. This response points to the need for social supports to be integrated with a treatment geared towards fostering autonomy, rather than dependency.

Limitations

First, this study involved partitioning participants into two groups based on their level of severity on clinical indicators. While this approach was effective in creating two highly divergent groups which allowed for the comparison and identification of key differences, this approach resulted in the majority of participants being screened out who did not meet criteria for either group. As such, by virtue of studying participants which exist at polar extremes of functioning, the representativeness of the included participants may be somewhat lessened. Rather, a typical patient with a personality disorder seen as a part of clinical work more likely resembles the excluded group, displaying a more mixed recovery journey of gains and set‐backs—rather than all of one or the other. We also note that in studying these two groups, the follow‐up period chosen (1 year) is relatively brief. While this follow‐up period is commonly employed in research paradigms investigating change over time (Cristea et al., 2017), we acknowledge the value in conducting a longer term follow‐up period to further assess the stability of an individual's recovery. Second, there was a modest sample size of participants in this study. In employing a mixed methods approach to analysis, our sample size is robust for qualitative analysis (Crouch & McKenzie, 2006; Guest et al., 2006), however may be underpowered for interpreting quantitative findings in isolation. As such, results should be interpreted in an integrative fashion, with quantitative results viewed as supporting the qualitative findings presented. Third, while this study has sought to explore differences in recovery through the prism of ‘love and work’, a limitation of the study is not systematically examining other key variables that may influence treatment trajectory, such as childhood trauma (Soloff et al., 2002), genetic vulnerability, age of onset and early remission, or the presence of other severe co‐morbid conditions including eating disorders or substance use disorders. Fourth, the age of participants in this sample (32–33 years) raises questions of representativeness, as research suggests symptoms of personality disorder typically emerge at a younger age than the current sample (Newton‐Howes et al., 2015) and that symptoms decline over time (Winsper, 2021). As such, it may be expected for participants to achieve recovery by the approximate age of our sample. On the other hand, we note that it is common for individuals to experience a protracted period of illness before receiving an accurate diagnosis and treatment. Further, systematic reviews of BPD patients in treatment report a mean age of 30 years (Woodbridge, Townsend, et al., 2021), which approximates our sample age. However, irrespective of these points, the case could also be made that as this is an older cohort, the sample is more relevant, not less, as the study identifies two groups: one doing well around this expected age of recovery, and one group not. Our focus is thus on exploring the differences in recovery outcomes for these two groups. Finally, this study was presented in a retrospective format through identifying participants functioning at follow‐up, then allocating group membership and analysis. To some extent, this research approach could be construed as just proving what we already know—that people with enduring mental health problems have ongoing challenges managing emotions and establishing stability in living. While a limitation of retrospective studies such as this one, what is remarkable however is how ‘love and work’ themes were spontaneously discussed by participants as either critical elements in either their recovery over the 12 months (for those doing well) or helped explain why they were still functioning poorly. We thus see these ‘love and work’ themes as important areas of future clinical and research focus. Future research should also focus on the effects of therapeutic interventions related to clinical change mechanisms in a proactive or predictive fashion, in order to further our understanding of effective therapeutic interventions for personality disorder. It may be that the diverse outcomes are due to the psychotherapy approach, or alternatively the presence of good relationships and work spurred the patient to improve in therapy. We suspect that there is a relationship between the two and change happens in both domains, but further research is required to understand these processes.

CONCLUSION

This study aimed to explore the lived experiences of individuals with BPD who were functioning well, compared with those who were not. Importantly, both groups were equivalent at intake in terms of demographics and severity of clinical symptom profile. At 1‐year follow‐up, two groups were distinguishable based on clinical characteristics. This was despite the fact that both groups maintained equivalent engagement in both intensive treatment (regular psychotherapy and psychiatry consultation) and general care (physician and case management supports). The ‘functioning well’ group was found to have significant improvement on social and occupational functioning domains, as well as clinical indicators (BPD severity, mental health and QOL) over time. This group had qualitative themes of meaningful and long‐term relationships with others, enjoyment in vocation, and described less frequent or manageable life crises. The ‘functioning poorly’ did not significantly improve on clinical characteristics, or social and occupational functioning at follow‐up. Their qualitative responses included relationship instability, discontent or isolation, difficulties with maintaining study or work, feelings of aimlessness and purposelessness and instability in tasks of daily living and frequent crises. These qualitative themes had clear divergent nomological networks when analysed via content analysis software. While these results support evidence of robust recovery from personality disorder, patients with severe presentations may have less positive recovery trajectories. Clinical implications include the need for an explicit focus on ‘love and work’ in the treatment of personality disorder, extending beyond only the individual and their symptoms and focusing on elements that foster a life worth living.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There were no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Data were collected in accordance with health service guidelines and approved by the University of Wollongong and the Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee. Site‐specific approval was given at the local health district sites. All participants provided written consent prior to taking part in the study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Project Air Strategy acknowledges the support of the NSW Ministry of Health (grant number DOH09‐33). The funding body had no role in the study design, collection, data analysis and interpretation, or preparation of the manuscript. Open access publishing facilitated by University of Wollongong, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of Wollongong agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Grenyer, B. F. S. , Townsend, M. L. , Lewis, K. , & Day, N. (2022). To love and work: A longitudinal study of everyday life factors in recovery from borderline personality disorder. Personality and Mental Health, 16(2), 138–154. 10.1002/pmh.1547

Funding information NSW Ministry of Health, Grant/Award Number: DOH09‐33

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise research participant privacy and consent and permission to release them was not given.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association . (Ed.) (2000). Diagnostic and statistic manual of mental disorders (Fourth ed., Text Revision ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (Ed.) (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, A. W. , Gunderson, J. , & Mulder, R. (2015). Treatment of personality disorder. The Lancet, 385(9969), 735–743. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61394-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick, D. M. , Murphy, J. M. , Goldman, P. A. , Ware, J. E. , Barsky, A. J. , & Weinstein, M. C. (1991). Performance of a five‐item mental health screening test. Medical Care, 29(2), 169–176. 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskin, R. S. (2015). The lifetime course of borderline personality disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(7), 303–308. 10.1177/070674371506000702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, D. W. , Gunter, T. , Allen, J. , Blum, N. , Arndt, S. , Wenman, G. , & Sieleni, B. (2007). Borderline personality disorder in male and female offenders newly committed to prison. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(5), 400–405. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , Clarke, V. , Hayfield, N. , & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In Liamputtong P. (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer Singapore. 10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caligor, E. , Levy, K. N. , & Yeomans, F. E. (2015). Narcissistic personality disorder: Diagnostic and clinical challenges. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(5), 415–422. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14060723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D. E. , & Kuhl, E. A. (2014). DSM‐5 cross‐cutting symptom measures: A step towards the future of psychiatric care? World Psychiatry, 13(3), 314–316. 10.1002/wps.20154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin, J. F. , Yeomans, F. E. , & Kernberg, O. F. (2006). Psychotherapy for borderline personality: Focussing on object relations. American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney, D. B. , & Makinen, J. (2016). Impact of diagnosis disclosure on adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(3), 177–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristea, I. A. , Gentili, C. , Cotet, C. D. , Palomba, D. , Barbui, C. , & Cuijpers, P. (2017). Efficacy of psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 74, 319–328. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.4287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, M. , & McKenzie, H. (2006). The logic of small samples in interview‐based qualitative research. Social Science Information, 45(4), 483–499. 10.1177/0539018406069584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P. , Smits, N. , Donker, T. , ten Have, M. , & De Graaf, R. (2009). Screening for mood and anxiety disorders with the five‐item, the three‐item and the two item mental health inventory. Psychiatry Research, 168(3), 250–255. 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day, N. J. S. , Hunt, A. , Cortis‐Jones, L. , & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2018). Clinician attitudes towards personality disorder: A 15 year comparison. Personality and Mental Health, 12, 309–320. 10.1002/pmh.1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, W. D. , Rosenstein, L. K. , Morgan, T. A. , & Zimmerman, M. (2018). Community and clinical epidemiology of borderline personality disorder. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 41(4), 561–573. 10.1016/j.psc.2018.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, P. (2003). Travelling through the system: The lived experience of people with borderline personality disorder in contact with psychiatric services. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10, 393–400. 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00617.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillard, S. , Turner, K. M. T. , & Neffgen, M. (2015). Understanding recovery in the context of lived experience of personality disorders: A collaborative, qualitative research study. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 183. 10.1186/s12888-015-0572-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenyer, B. F. S. (2013). Improved prognosis for borderline personality disorder: New treatment guidelines outline specific communication strategies that work. The Medical Journal of Australia, 198(9), 464–465. 10.5694/mja13.10470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenyer, B. F. S. (2014). An integrative relational step‐down model of care: The project air strategy for personality disorders. The ACPARIAN, 9, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Grenyer, B. F. S. , Lewis, K. L. , Fanaian, M. , & Kotze, B. (2018). Treatment of personality disorder using a whole of service stepped care approach: A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 13(11), e0206472. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G. , Bunce, A. , & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. 10.1177/1525822X05279903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashworth, T. , Reis, S. , & Grenyer, B. F. (2021). Personal agency in borderline personality disorder: The impact of adult attachment style. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2224. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm, A. L. , Begat, I. , & Severinsson, E. (2009). Emotional pain: Surviving mental health problems related to childhood experiences. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16, 636–645. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm, A. L. , & Severinsson, E. (2011). Struggling to recover by changing suicidal behaviour: Narratives from women with borderline personality disorder. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 20, 165–173. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00713.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn, N. , Johnstone, L. , & Brooke, S. (2007). Some service user perspectives on the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Mental Health, 16(2), 255–269. 10.1080/09638230601056371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, E. , Lewis, K. L. , Coates, A. D. , Borg, W. M. , Miller, C. E. , Townsend, M. L. , & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2019). Evaluation of a brief intervention within a stepped care whole of service model for personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 341. 10.1186/s12888-019-2308-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaite, C. P. , Karanikola, M. , Merkouris, A. , & Papathanassoglou, E. D. E. (2015). “An ongoing struggle with self and illness”: A meta‐synthesis of the studies of the lived experience of severe mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29, 458–473. 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsakou, C. , & Pistrang, N. (2017). Clients' experience of treatment and recovery in borderline personality disorder: A meta‐synthesis of qualitative studies. Psychotherapy Research, 28, 1468–4381. 10.1080/10503307.2016.1277040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, J. W. , Flanagan, E. H. , & McCluskey, D. L. (2014). Functional impairment and the DSM‐5 dimensional system for personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28(5), 657–674. 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg, O. (2008). Aggressivity, narcissism, and self‐destructiveness in the psychotherapeutic relationship: New developments in the psychopathology and psychotherapy of severe personality disorders. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lariviere, N. , Couture, E. , Blackburn, C. , Carbonneau, M. , Lacombe, C. , Schinck, S. A. , Larivière, N. , David, P. , & St‐Cyr‐Tribble, D. (2015). Recovery, as experienced by women with borderline personality disorder. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 86, 555–568. 10.1007/s11126-015-9350-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger, M. F. , Lane, M. C. , Loranger, A. W. , & Kessler, R. C. (2007). DSM‐IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 62(6), 553–564. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K. L. , Fanaian, M. , Kotze, B. , & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2018). Mental health presentations to acute psychiatric services: 3‐year study of prevalence and readmission risk for personality disorders compared with psychotic, affective, substance or other disorders. BJPsych Open, 5(1). 10.1192/bjo.2018.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi, V. , & McWilliams, N. (2017). Psychodynamic diagnostic manual (PDM‐2) (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. 10.4324/9780429447129-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C. E. , Lewis, K. L. , Huxley, E. , Townsend, M. L. , & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2018). A 1‐year follow‐up study of capacity to love and work: What components of borderline personality disorder most impair interpersonal and vocational functioning? Personality and Mental Health, 12(4), 334–344. 10.1002/pmh.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C. , Smith, I. , & Alwin, N. (2014). Is contact with adult mental health services helpful for individuals with a diagnosable BPD? A study of service users views in the UK. Journal of Mental Health, 23(5), 251–255. 10.3109/09638237.2014.951483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New South Wales Department of Health . (2001). Your guide to MH‐OAT: Clinicians' reference guide to NSW Mental Health outcomes and assessment tools. NSW Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Newton‐Howes, G. , Clark, L. A. , & Chanen, A. (2015). Personality disorder across the life course. The Lancet, 385(9969), 727–734. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61283-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, F. Y. Y. , Bourke, M. E. , & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2016). Recovery from borderline personality disorder: A systematic review of the perspectives of consumers, clinicians, family and carers. PLoS ONE, 11(8), e0160515. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, F. Y. Y. , Carter, P. E. , Bourke, M. E. , & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2019). What do individuals with borderline personality disorder want from treatment? A study of self‐generated treatment and recovery goals. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 25(2), 148–155. 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, F. Y. Y. , Townsend, M. L. , Jewell, M. , Marceau, E. M. , & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2020). Priorities for service improvement in personality disorder in Australia: Perspectives of consumers, carers and clinicians. Personality and Mental Health, 14(4), 350–360. 10.1002/pmh.1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, F. Y. Y. , Townsend, M. L. , Miller, C. E. , Jewell, M. , & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2019). The lived experience of recovery in borderline personality disorder: A qualitative study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 6(1), 10. 10.1186/s40479-019-0107-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project Air Strategy for Personality Disorders . (2015). Brief intervention manual for personality disorders. University of Wollongong, Illawarra Health and Medical Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International . (2015). NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Redding, A. , Maguire, N. , Johnson, G. , & Maguire, T. (2017). What is the lived experience of being discharged from a psychiatric inpatient stay? Community Mental Health Journal, 53(5), 568–577. 10.1007/s10597-017-0092-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring, D. , & Lawn, S. (2019). Stigma perpetuation at the interface of mental health care: A review to compare patient and clinician perspectives of stigma and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Mental Health, 1–21. 10.1080/09638237.2019.1581337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, B. , & Acton, T. (2012). ‘I think we're all guinea pigs really’: A qualitative study of medication and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19, 341–347. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01800.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, B. , & Dunne, E. (2011). ‘They told me I had this personality disorder … all of a sudden I was wasting their time’: Personality disorder and the inpatient experience. Journal of Mental Health, 20(3), 226–233. 10.3109/09638237.2011.556165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf, H.‐J. , Meyer, C. , Hapke, U. , & John, U. (2001). Screening for mental health: Validity of the MHI‐5 using DSM‐IV Axis I psychiatric disorders as gold standard. Psychiatry Research, 105(3), 243–253. 10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00329-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. E. (2021). Leximancer user guide, 4.5. Leximancer. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. E. , & Humphreys, M. S. (2006). Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behavior Research Methods, 38(2), 262–279. 10.3758/BF03192778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff, P. H. , Lynch, K. G. , & Kelly, T. M. (2002). Childhood abuse as a risk factor for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 16(3), 201–214. 10.1521/pedi.16.3.201.22542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriadou, P. , Brouwers, J. , & Le, T. A. (2014). Choosing a qualitative data analysis tool: A comparison of NVivo and Leximancer. Annals of Leisure Research, 17(2), 218–234. 10.1080/11745398.2014.902292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spodenkiewicz, M. , Speranza, M. , Taïeb, O. , Pham‐Scottez, A. , Corcos, M. , & Révah‐Levy, A. (2013). Living from day to day—Qualitative study on borderline personality disorder in adolescence. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de l'Academie canadienne de psychiatrie de l'enfant et de l'adolescent, 22(4), 282–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, A. , & Wright, A. (2017). The experiences of people with borderline personality disorder admitted to acute psychiatric inpatient wards: A meta‐synthesis. Journal of Mental Health, 28, 443–457. 10.1080/09638237.2017.1340594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Startup, M. , Jackson, M. C. , & Bendix, S. (2002). The concurrent validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 41(4), 417–422. 10.1348/014466502760387533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand, B. H. , Dalgard, O. S. , Tambs, K. , & Rognerud, M. (2003). Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: A comparison of the instruments SCL‐25, SCL‐10, SCL‐5 and MHI‐5 (SF‐36). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 57(2), 113–118. 10.1080/08039480310000932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer, S. H. , Muenchow, E. , Potvin, A. , Harris, J. , & Gigot, G. (2016). Improving patient‐centered communication of the borderline personality disorder diagnosis. Journal of Mental Health, 25(1), 5–9. 10.3109/09638237.2015.1022253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trompenaars, F. J. , Masthoff, E. D. , Van Heck, G. L. , Hodiamont, P. P. , & De Vries, J. (2005). Content validity, construct validity, and reliability of the WHOQOL‐Bref in a population of Dutch adult psychiatric outpatients. Quality of Life Research, 14(1), 151–160. 10.1007/s11136-004-0787-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troyat, H. (1967). Tolstoy: A biography. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Viera, A. J. , & Garrett, J. M. (2015). Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Family Medicine, 37(5), 360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viney, L. L. (1983). Assessment of psychological states through content analysis of verbal communications. Psychological Bulletin, 94(3), 542–563. 10.1037/0033-2909.94.3.542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viney, L. L. (1986). Expression of positive emotion by people who are physically ill: Is it evidence of defending or coping? Content analysis of verbal behavior (pp. 215–224). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-642-71085-8_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viney, L. L. , & Westbrook, M. T. (1986). Psychological states in patients with diabetes mellitus. In Content analysis of verbal behavior (pp. 157–169). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-642-71085-8_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J. E. , & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 35‐item short‐form health survey (SF‐36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 476–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, Y. , & Grenyer, B. F. S. (1999). The biopsychosocial impact of end‐stage renal disease: The experience of dialysis patients and their partners. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 30(6), 1312–1320. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL Group . (1998). Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL‐BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine, 28(3), 551–558. 10.1017/S0033291798006667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsper, C. (2021). Borderline personality disorder: Course and outcomes across the lifespan. Current Opinion in Psychology, 37, 94–97. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodbridge, J. , Reis, S. , Townsend, M. L. , Hobby, L. , & Grenyer, B. F. (2021). Searching in the dark: Shining a light on some predictors of non‐response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. PLoS ONE, 16(7), e0255055. 10.1371/journal.pone.0255055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodbridge, J. , Townsend, M. , Reis, S. , Singh, S. , & Grenyer, B. F. (2021). Non‐response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 00048674211046893. 10.1177/00048674211046893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2019). The ICD‐11 classification of mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders (11th ed.). Author. 10.5005/jp-journals-10067-0030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini, M. C. , Temes, C. M. , Frankenburg, F. R. , Reich, D. B. , & Fitzmaurice, G. M. (2018). Description and prediction of time‐to‐attainment of excellent recovery for borderline patients followed prospectively for 20 years. Psychiatry Research, 262, 40–45. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini, M. C. , Vujanovic, A. A. , Parachini, E. A. , Boulanger, J. L. , Frankenburg, F. R. , & Hennen, J. (2003). A screening measure for BPD: The McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI‐BPD). Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(6), 568–573. 10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnierek, C. D. (2011). Exploring lived experiences of persons with severe mental illness: A review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32(1), 46–72. 10.3109/01612840.2010.522755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise research participant privacy and consent and permission to release them was not given.