Abstract

PURPOSE:

Describe the feasibility and implementation of an electronic health record (EHR)–integrated symptom and needs screening and referral system in a diverse racial/ethnic patient population in ambulatory oncology.

METHODS:

Data were collected from an ambulatory oncology clinic at the University of Miami Health System from October 2019 to January 2021. Guided by a Patient Advisory Board and the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment model, My Wellness Check was developed to assess physical and psychologic symptoms and needs of ambulatory oncology patients before appointments to triage them to supportive services when elevated symptoms (eg, depression), barriers to care (eg, transportation and childcare), and nutritional needs were identified. Patients were assigned assessments at each appointment no more than once in a 30-day period starting at the second visit. Assessments were available in English and Spanish to serve the needs of the predominantly Spanish-speaking Hispanic/Latino population.

RESULTS:

From 1,232 assigned assessments, more than half (n = 739 assessments; 60.0%) were initiated by 506 unique patients. A total of 65.4% of English and 49.9% of Spanish assessments were initiated. Among all initiated assessments, the majority (85.1%) were completed at home via the patient portal. The most common endorsed items were nutritional needs (32.9%), followed by emotional symptoms (ie, depression and anxiety; 27.8%), practical needs (eg, financial concerns; 21.7%), and physical symptoms (17.6%). Across the physical symptom, social work, and nutrition-related alerts, 77.1%, 99.7%, and 78.8%, were addressed, respectively, by the corresponding oncology health professional, social work team member, or nutritionist.

CONCLUSION:

The results demonstrate encouraging feasibility and initial acceptability of implementing an EHR-integrated symptom and needs screening and referral system among diverse oncology patients. To our knowledge, this is the first EHR-integrated symptom and needs screening system implemented in routine oncology care for Spanish-speaking Hispanics/Latinos.

BACKGROUND

There will be an expected 22.1 million cancer survivors (ie, any person with a prior cancer diagnosis, from the point of cancer diagnosis forward) in the United States by the year 2030.1 The experience of survivors across the cancer continuum (ie, from diagnosis to survivorship and end of life) is complex and frequently associated with decrements in health-related quality of life (HRQoL), chronic and debilitating symptom burden, and increases in patient needs including psychosocial, practical, and nutritional needs, among others.2,3 Historically, as highlighted by the National Academy of Medicine, cancer survivors' psychosocial needs and practical concerns are usually not adequately addressed.4,5 In response, organizations such as the National Cancer Institute, American College of Surgeons' Commission on Cancer (CoC), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network (NCCN) have set forth mandated standards for psychosocial distress and symptom screening and management.6,7

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are assessments of health, including psychosocial distress and symptoms, that are directly reported by the patient.8 Emerging evidence suggests that routine collection of PROs may facilitate responsive, patient-centered care, and are associated with better patient-provider communication, satisfaction with care, and clinical outcomes.9-11 The use of technology to collect PROs has also facilitated the timely identification of symptoms thereby improving management and preventing adverse events among cancer survivors. For example, a trial by Basch et al10 demonstrated that the routine collection of PROs, using a web-based platform, improved HRQoL and survival as well as decreased emergency room visits. There has been a recent push to integrate PROs in electronic health records (EHRs)11-15 whereby integrating other health data and promoting real-time delivery and care coordination.16-18 However, best practices are still unclear16 and therefore, studies have focused on identifying barriers/facilitators and challenges/opportunities to implementation of EHR-integrated PROs.12,14,15,19 Additionally, Garcia et al11 demonstrated the feasibility of implementing EHR-integrated PROs collection as standard of care in routine ambulatory oncology care at Northwestern Medicine health care system.

Although there is emerging evidence for the routine collection of PROs in ambulatory oncology,9,10,20-22 implementation guidelines and theoretical frameworks need to be further described to support adoption and scalability of PRO collection. Therefore, the aim of the current paper is to describe the implementation and feasibility and initial acceptability of an EHR-integrated PROs and needs screening and referral system using the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainability (EPIS) framework. Additionally, to date, research examining the routine collection of PROs in oncology has largely focused on English-speaking, non-Hispanic Whites, thereby limiting our understanding of these approaches among Hispanic/Latinos. This is despite the fact that past studies have documented disparities in HRQoL23,24 and greater unmet supportive care needs25-29 among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors, particularly those who are primarily Spanish-speaking. Given the growing Hispanic/Latino population in the United States,30 and to address the under-representation of Hispanics/Latinos in cancer survivorship research, this quality improvement initiative was implemented at the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center (SCCC) ambulatory clinic that serves a very diverse catchment area and therefore adapted for English and Spanish speakers. To our knowledge, this is first time PROs have been implemented in routine oncology care for Spanish-speaking Hispanics/Latinos.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

Initial meetings were held with SCCC leadership and chief physicians to select test clinics to pilot the initiative. Four test clinics were identified and ultimately, the gynecology oncology (GYN-ONC) ambulatory clinic was selected as the lead test clinic for pilot implementation because of its established clinic workflow, available resources, and strong research infrastructure as part of an academic health system. There are a total of four board-certified gynecologic oncologists who perform cancer surgeries, administer chemotherapy, oversee clinical trials, and do survivorship/surveillance care for women with gynecologic malignancies (ovarian/fallopian tube, uterine, cervical, and vulvar/vaginal). Annually, the GYN-ONC clinic sees approximately 1,200 new patients and nearly 9,000 total encounters (ie, visits). The study team met with the chief physician of the GYN-ONC clinic to attain final approval.

Procedures

The My Wellness Check initiative is a quality improvement project implemented in the SCCC GYN-ONC ambulatory clinic. To comply with CoC emotional distress screening standards, My Wellness Check was developed to assess symptoms and needs of patients with cancer in ambulatory oncology before their appointments to triage patients to supportive care services and to address elevated symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety, and fatigue), barriers to care (eg, transportation and childcare), and nutritional needs. To incorporate key recommendations made by patients on the initial acceptability and functionality of the initiative, initial design and implementation was informed by a focus group held with patients from the Patient Advisory Board (n = 9). In the focus group, an overview of the distress screening initiative rationale, workflow, utility, and potential future benefit to patients and health care operations was provided. Then, patients were led through a mock demonstration of completing their assessments in a secured test patient portal environment. The focus group was led by a qualitative methods expert, a cancer care delivery expert, and an information technology (IT) representative, and was audio-recorded for transcription and thematic analysis.

My Wellness Check uses the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, cancer-related diagnosis codes to identify patients via our electronic data warehouse and EHR systems (Epic). Patients scheduled to visit the GYN-ONC ambulatory clinic for a second or later visit were identified since first visits are generally focused on the diagnosis and treatment planning, which create high levels of anxiety that tend to resolve over time and at this point, as part of standard practice, patient distress is already addressed through various methods, including the Distress Thermometer31 and Patient Health Questionnaire.32 Patients were notified by Epic MyChart to complete the assessment via prior stated preferences (ie, via e-mail, MyChart patient portal message, or phone call). Assessments were available in English and Spanish and take approximately 8-10 minutes to complete via the patient's MyChart account (web or smartphone app). Patients were asked to complete these assigned assessments 72 hours before their next appointment. Patients who had multiple visits in a month completed only one PRO assessment within a 30-day period. If the assessment was not completed before their visit, patients were asked by the intake nurse to complete the assessment at the time of the visit via their own smartphone or clinic provided tablet/computer. Moderate or severe symptom elevations in fatigue, pain, and/or physical function as assessed by Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) triggered alerts to the medical team within the EHR, whereas depression and anxiety alerts were routed to social work (described in more detail in the Measures section). Endorsement of any psychosocial or practical need, or a nutritional need, triggered best practice advisory (BPA) alerts to the social work or nutrition teams, respectively. Treatment teams were mandated to address the alert with a disposition (eg, referral, intervention, etc) within 72 hours of the alert (72-hour mandate was not in place for physical needs-pain, fatigue, physical function; Fig 1). Within Epic, providers could see the PRO measures administered, completion date, patients' responses to individual questionnaire items, PROMIS T-scores, corresponding severity threshold classifications (normal, mild, moderate, or severe), and score trends. Providers followed up with patients during clinic visits, by telephone, or through MyChart messages. Dispositions, BPA alerts, and clinician notification processes were developed in collaboration with Epic, IT programmers, SCCC GYN-ONC clinical providers, and supportive oncology services (social work/nutrition team members). The described initiative is part of a performance improvement project and was introduced as standard of care; therefore, it was deemed exempt from institutional review board review, and informed consent was waived.

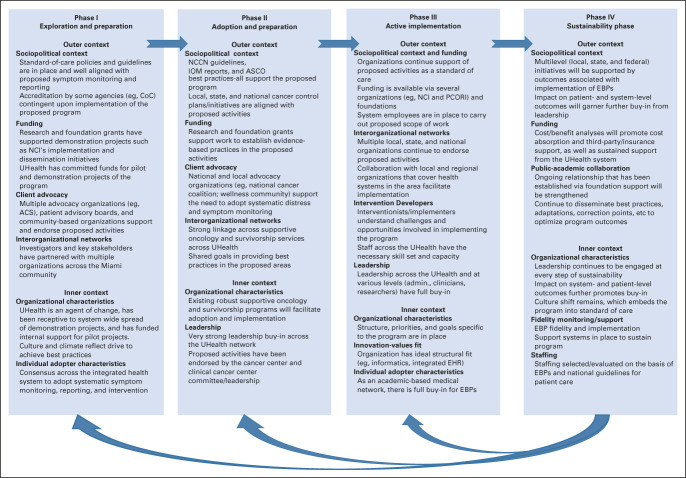

FIG 1.

My Wellness Check initiative workflow. Patients with a scheduled second oncology visit and a confirmed ICD-10 cancer diagnosis who have not received the My Wellness Check assessment within the past 30 days are contacted via text, e-mail, or the patient portal (on the basis of their stated preferences) 72 hours before their appointment and asked to complete the assessments. Patients who do not complete the assessment before their scheduled appointment have an opportunity to complete it within the clinic visit at multiple touchpoints (eg, registration, waiting room, via intake nurse). Once the assessment is completed, the results are populated in real time in the EHR. Best practice alerts are generated and triaged as follows: (1) clinically elevated anxiety, depression, and/or endorsed practical and psychosocial needs (eg, transportation and stress management) generate an alert to Social Work/Cancer Support Services; (2) clinically elevated pain, fatigue, and/or poor physical function generate an alert to the oncology team; and (3) endorsement of nutrition needs generates an alert to the nutrition team. Alerts remain open until a disposition is coded (eg, treatment, referral, etc). The process repeats itself but not more than once every 30 days. CAT, computer adaptive test; EHR, electronic health record; EMR, electronic medical record; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; PRO, patient-reported outcomes.

Measures

Patients completed PROMIS computer adaptive tests (CATs) for depression, anxiety, fatigue, pain, and physical function33; a psychosocial (eg, need for stress management), practical (eg, assistance with childcare), and nutritional needs assessment adapted from NCCN Distress Thermometer Problem Checklist31 and vetted with the GYN-ONC social workers and other clinicians; and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General (7-item version; FACT-G7).34 PROMIS CATs were fully integrated into Epic using the PROMIS Epic App, which is available through App Orchard, Epic's website for sharing apps with the user community.35 Other PRO measures were incorporated into Epic in collaboration with corresponding key Epic and IT support personnel.

All PROMIS CATs were previously calibrated using item response theory for each domain, thereby tailoring future items to the patient's previously self-reported symptom severity scores.36-38 PROMIS CATs are brief, reliable, and well-validated adaptive measures of various PROs that have been widely used in ambulatory oncology populations. PROMIS CATs generate T-scores and corresponding severity thresholds (normal, mild, moderate, or severe) on the basis of normative data from patients with cancer and the general population.39 A T-score of 50 is the mean, and 10 is the standard deviation of the reference population. Furthermore, the FACT-G7 is the brief version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy34 used to assess HRQoL.34 Patient responses on the PROMIS CATs that generate T-scores at a moderate or severe level trigger an EHR in-basket alert, specifically ≥ 70 for pain interference and fatigue, ≥ 65 for anxiety, ≥ 60 for depression, and ≤ 30 for physical function.11 Moderate or severe elevations in depression and anxiety were defined as emotional needs and trigger alerts to social work, whereas moderate or severe elevations in pain, fatigue, and/or physical function were defined as physical needs and trigger alerts for the medical team. Overall, individual alerts could be triggered for pain, fatigue, physical function, anxiety, depression, psychosocial/practical needs, and nutritional needs for a maximum of seven alerts possible per assessment. The FACT-G7 did not trigger an alert.

Approach to Implementation

Our work was guided by the EPIS framework, a well-established dissemination and implementation model. The EPIS framework is closely aligned with our overarching goal to create a multilevel, comprehensive model of care with My Wellness Check. The EPIS framework accounts for feedback and dynamic processes on the basis of the needs of the clinic setting while emphasizing minimal system burden. It allows for the ongoing identification and modification of key challenges to successful implementation over time, guided across four stages. In the Exploration Phase, a pressing need among patients, clients, or communities that requires attention is identified, or an improved approach to an organizational challenge is acknowledged. In the Preparation Phase, the barriers and facilitators to implementation of the chosen evidence-based practice (EBP) or innovation are assessed. In the Implementation Phase, the EBPs are initiated, and there is ongoing monitoring to determine adjustments that must be made. Finally, in the Sustainment Phase, the limiting or facilitating factors that support the ongoing delivery of the EBP are addressed to promote the public health impact.40,41 In each stage, the outer system context (eg, policy and interorganizational relationships between entities) and inner organizational context (eg, leadership, organizational structures and resources, and individual adopter characteristics) are considered, and adaptations are made as necessary.41

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to report patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (ie, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, etc). Univariate statistics were used to assess the initial project metric of feasibility, which was defined through patient and provider engagement in accordance with Bowen et al.42 On the basis of prior data from an EHR-based assessment of PROs among patients with cancer,13 feasibility was defined as patient assessment initiation rates of at least 40%, including overall assessment initiation rate as well as by assessment initiation rates among Spanish and English speakers. The proportion of BPAs addressed by the corresponding health care professional was deemed to demonstrate adequate feasibility with a response rate of 70% or higher. Among assessments that were initiated, feasibility was defined as an overall completion rate of 70%. Initial acceptability, defined as overall satisfaction/suitability, perceived appropriateness, and perceived positive effects of My Wellness Check on care,42 was ascertained through qualitative analysis of the Patient Advisory Board focus group. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim, and qualitative analysis of the focus group was conducted using a thematic analysis approach.43 This methodology is used to identify, analyze, and report themes within the data and helps to generate insights and interpretations of the data.44 First, two researchers reviewed the transcriptions and began a thematic analysis by searching for common patterns and themes throughout the text. Second, transcriptions were uploaded to NVivo 12 Plus where parent (themes) and child (subthemes) nodes were identified. Some categories were consolidated, whereas others were expanded upon. The two researchers compared their analyses, discussed differences, and reached a consensus regarding generated themes.

RESULTS

Implementation Plan Analysis

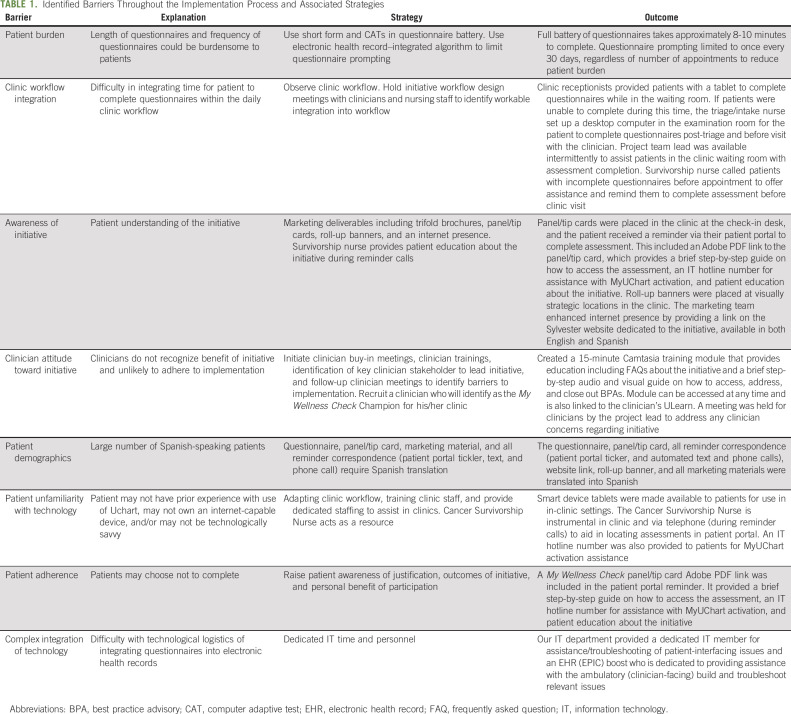

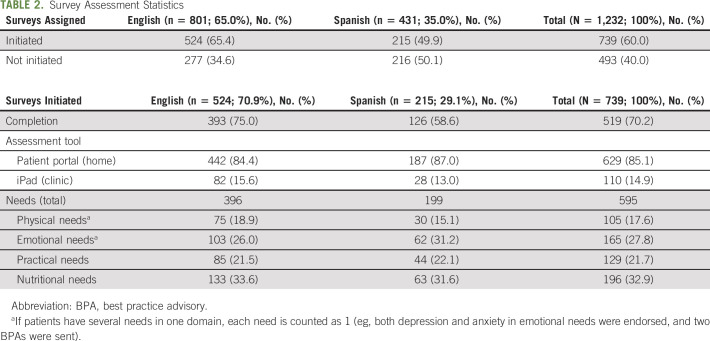

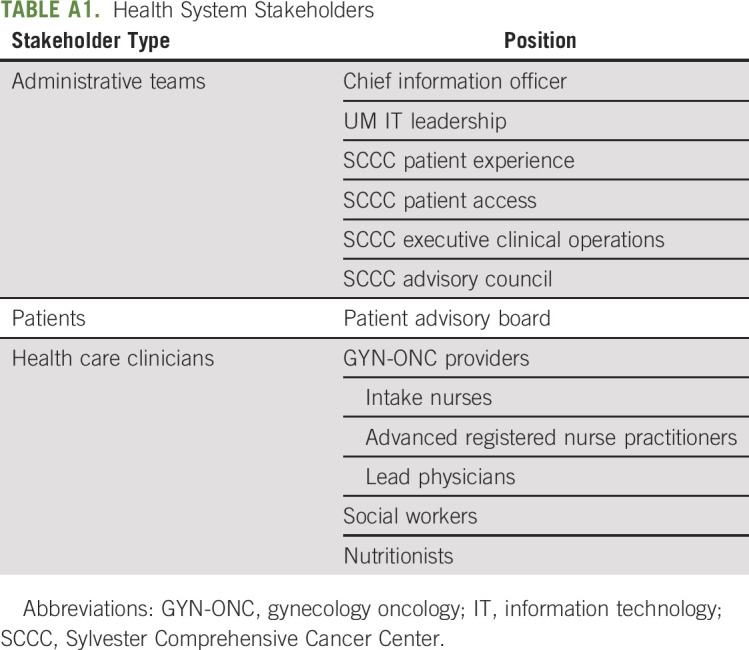

The application of the EPIS framework across each phase of the implementation process of My Wellness Check is shown in Figure 2. A workgroup was established, which was composed of key stakeholders (eg, leadership, investigators, etc; Appendix Table A1, online only). Weekly reporting and fidelity reports informed the current feasibility and uptake of this initiative. As such, the intervention developers and implementers attained an understanding of the challenges and opportunities in implementing My Wellness Check. Considering clinic workflows and patient integration, further modifications were made to improve uptake and reduce patient/clinic burden. The barriers and facilitators to implementation of My Wellness Check were identified according to the phases of the EPIS model and are presented in Table 1. For example, ongoing in-clinic trainings and in-service demonstrations were conducted with nutrition, social work, and the entire SCCC gynecologic oncology staff. Additionally, ongoing collaboration with University of Miami Health System (UHealth; the health system under which SCCC operates) leadership, such as executive directors, clinician early adopters, administrators responsible for oversight, designated clinic workflow managers, and IT programmers, allowed us to gain full buy-in at multiple levels. Furthermore, the availability of institutionally sponsored Spanish language versions of patient materials across UHealth creates the ideal scientific environment to include a diverse, predominantly Spanish-speaking population in this initiative. A detailed description of the EPIS framework across each phase of the implementation process of My Wellness Check is provided in the Data Supplement (online only).

FIG 2.

EPIS framework for My Wellness Check. ACS, American Cancer Society; CoC, Commission on Cancer; EBP, evidence-based practice; EPIS, Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainability; IOM, Institute of Medicine; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network; NCI, National Cancer Institute; PCORI, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

TABLE 1.

Identified Barriers Throughout the Implementation Process and Associated Strategies

Qualitative Data

Qualitative data analysis from the mock demonstration (to the Patient Advisory Board) revealed four overarching themes, which included previous experience with the patient portal; ability to navigate the patient portal and questionnaires; initial acceptability and functionality of questionnaires; and content-related suggestions. Most participants had used the patient portal MyUHealth Chart before, and thought it was easy to navigate. Participants agreed that the My Wellness Check program was useful if feedback and referrals were obtained in a timely manner by their clinicians. Most preferred to complete assessments before their clinic visit. Addressing the lack of supportive care services during their cancer care experience was identified as a major concern that can be addressed by My Wellness Check.

Initial Project Metrics

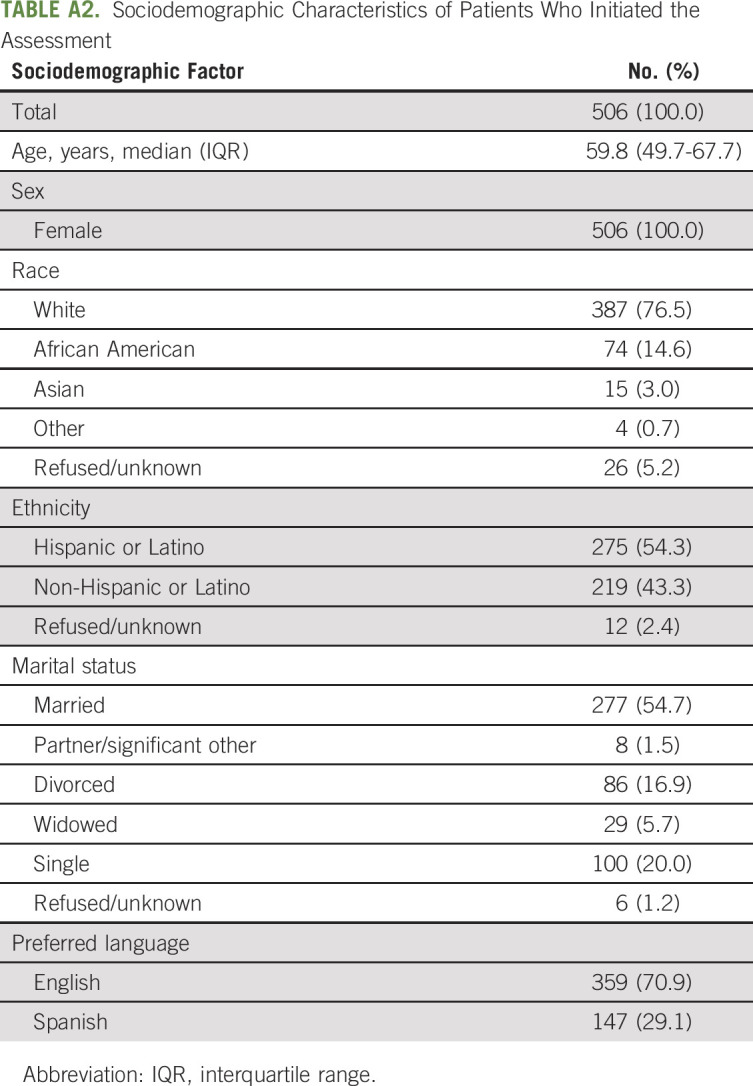

Patient sociodemographic characteristics.

Between October 2019 and January 2021, a total of 834 individual patients were assigned an assessment, of which 506 (60.7%) patients initiated the assessment (ie, completed at least one questionnaire). Appendix Table A2 (online only) shows the sociodemographic characteristics of these patients who initiated the assessment. All patients were females, with a median age of 59.8 years (interquartile range: 49.7-67.7 years), and were primarily married (n = 277; 54.7%). This sample included 387 (76.5%) White, 74 (14.6%) African American, and 15 (3.0%) Asian/Pacific Islander women, of which 70.9% and 29.1% had an English and Spanish language preference, respectively, and 54.3% (n = 275) identified as Hispanic or Latino.

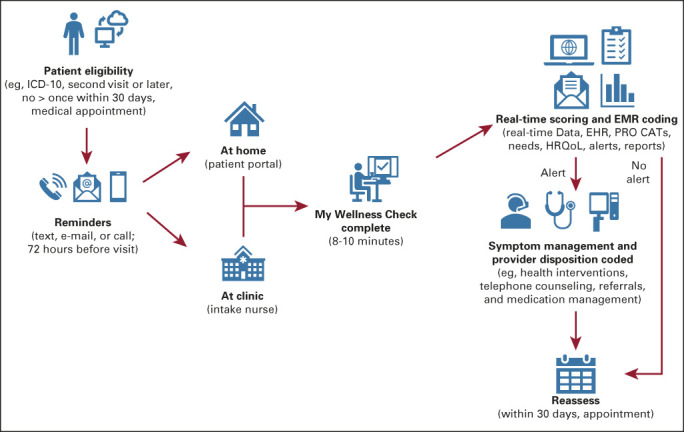

Survey assessment data.

A total of 1,232 assessments (an assessment consists of eight assigned PROs questionnaires: PROMIS CAT Depression, PROMIS CAT Anxiety, PROMIS CAT Pain Interference, PROMIS CAT Fatigue, PROMIS CAT Physical Function, Practical Needs Assessment, Nutritional Needs Assessment, and FACT-G7) were assigned in the target GYN-ONC clinic, of which 739 (60.0%) were initiated and 493 (40.0%) assessments were not opened (Table 2). Among assessments that were initiated, 70.2% were completed. Accordingly, 629 (85.1%) of initiated assessments were completed at home via the patient portal and 110 (14.9%) were completed in-clinic via the intake nurse/clinic staff. A total of 595 BPAs were triggered from 44.9% of initiated assessments (ie, 332 out of 739 initiated assessments triggered an alert), the majority were for nutritional needs (32.9%), followed closely by emotional needs (27.8%, ie, depression and anxiety), practical needs (21.7%), and physical needs (17.6%). In terms of nutritional needs, 23.7% had concerns regarding general nutrition counseling; 21.2% wanted information regarding vitamins, supplements, and herbs; and 16.7% noted difficulty losing weight or had unintentional weight gain. Additionally, the most noted practical and psychosocial needs included financial/insurance concerns (22.5%), coping with their illness and/or managing stress (17.6%), and overall general education and information (15.5%). Of the physical symptom, social work, and nutrition BPAs, 77.1% (n = 81), 99.7% (n = 293), and 78.8% (n = 154), respectively, were addressed by the corresponding GYN-ONC health professional, social work team member, or dietitian. Moreover, 43.4% (n = 127) and 86.4% (n = 133) of the social work and nutrition BPAs were addressed within the 72-hour time frame.

TABLE 2.

Survey Assessment Statistics

Among the total assigned assessments, 801 (65.0%) were in English and 431 (35.0%) in Spanish. For assigned English assessments, exclusively, 524 (65.4%) were initiated, of which 393 (75.0%) were completed. For Spanish, 215 (n = 49.9%) assessments were initiated and of those initiated, 126 (58.6%) were completed. In terms of mode of completion, 87.0% and 84.4% of Spanish- and English-initiated assessments, respectively, were completed at home via the patient portal. For triggered BPAs, there was a higher endorsement of emotional needs among those who completed the assessments in Spanish (31.2%) versus English (26.0%) but lower endorsement of nutritional needs (31.6% v 33.6% for Spanish and English, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Our goal was to implement My Wellness Check, an EHR-integrated screening and referral system, guided by the EPIS framework. Our results demonstrate feasibility and initial acceptability in implementing an EHR-based symptom screening tool in a culturally diverse ambulatory care setting while also operationalizing the implementation of the EPIS framework components used in the process.

My Wellness Check uses feasible measurement instruments that capture clinically relevant outcomes (eg, NIH PROMIS measures) in a highly ethnically/racially diverse sample of patients with cancer and survivors. For example, nearly 20% of our patient population sample consisted of African American women. Additionally, this sample consisted primarily of Hispanic/Latino women (ie, more than 50%), and about one in every four patients were predominantly Spanish-speaking. This quality improvement initiative was adapted from previous work, which demonstrated the successful implementation of distress screening in routine ambulatory cancer care using EHR integration.11 To our knowledge, My Wellness Check is the first EHR-integrated platform to incorporate Spanish language PROMIS CATs. Historically, non–English-speaking populations have been excluded from such initiatives, given the lack of availability of Spanish-translated PRO measures. Therefore, we have built on past studies that have called for PROs to be integrated in the EHR in other languages, allowing patients to select their desired language.45 Technology implementation was also a central approach in this model. Novel and emerging technologies such as use of the patient portal (My Chart) were implemented. My Wellness Check is fully integrated within Epic rather than using third-party applications. Together, all these components contribute to the larger scalability unique to this quality improvement initiative.

In our study, more than half (60%) of the total screening assessments assigned to patients were initiated. Similarly, almost 50% of assessments specifically assigned in Spanish were initiated. This modest response rate is similar to that observed in the study by Garcia et al.11 However, to our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate uptake of PROs screening initiatives among Spanish speakers, thereby informing future efforts to reach racial/ethnic minority populations. Moreover, overall, 70.2% of initiated assessments (ie, 519 of 739) were completed, which suggests that patients who initiate the assessment are more likely than not to complete it. However, lower rates of initiation and completion were observed among Spanish speakers, suggesting targeted efforts are needed to increase engagement among this population. The majority, nearly 90%, were completed at home. Furthermore, 44.9% of assessments triggered a BPA, which is higher than previously observed for oncology outpatients.11 These metrics, as a whole, demonstrate the feasibility of My Wellness Check.

Notably, almost 100% of the BPAs intended for the social work team members were addressed accordingly. This is crucial, given the fact that social work is responsible for addressing the majority of BPAs, which not only include practical and psychosocial needs (eg, financial/insurance concerns, coping with illness/managing stress, general education, transportation, etc), but also those pertaining to anxiety and depression. Past studies documenting provider perceptions on the EHR integration of PROs have shown that medical team personnel as well as social workers may experience task overload45; however, social workers reported reviewing PROs as part of their routine care and using results to guide upcoming patient clinic encounters.45 In our pilot study, our goal was to minimize disruptions to clinic workflow, provider/patient burden, and maximize the use of clinically meaningful data by engaging with providers and stakeholders early on and having recurring meetings and trainings/demonstrations to incorporate feedback from GYN-ONC clinical providers, social work, and nutrition team members. Although there is currently no counteraction in place for providers who do not address alerts accordingly, weekly reporting/fidelity reports and educational newsletters were shared with providers in an effort to promote provider compliance. Given the lower rate of compliance with the 72-hour response mandate, future efforts should aim to increase the response time to BPAs.

Similar to past research,11 the most commonly triggered alert at the UHealth GYN-ONC test clinic was for nutritional needs. Although studies have demonstrated that nutrition is an important concern for cancer survivors and that a high proportion experience diet-related problems and lack of access to dietitians,46 it still remains an often overlooked component of cancer care. For example, in a survey of dietitians participating in the Oncology Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 47% of cancer centers were not screening for malnutrition.47 In accordance with this, there has been a call for the implementation of comprehensive nutritional screening and referral programs to dietitians in ambulatory oncology settings to identify and facilitate early management of nutritional concerns.46 Aside from weight and muscle loss, overnutrition is also equally as important as indicated by our study results, with people wanting to know more about weight loss and weight gain. Therefore, our study informs efforts regarding the importance of nutritional needs among cancer survivors, including those of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Given the overlap between implementation science and quality improvement science, past research has demonstrated that to improve the quality of cancer care, methodology from both disciplines should be used in the research design phase.48 The EPIS framework provided a structure for our scientific team to document the delivery and monitoring of the initiative in a systematic way.40,41 EPIS has been previously used to successfully implement EBPs. The framework demonstrates high adaptability, given its application in a diverse array of settings and topic areas that include mental health, substance use disorder treatment, and child welfare.41 In fact, EPIS has successfully guided the implementation of EHR-integrated distress screening initiatives at large, multisite health care centers.49 In our initiative, during the Adoption and Preparation phase of the EPIS model, the study team had a meeting with stakeholders (eg, administrators, clinicians, and patient advocates) to explain the EPIS framework and attain initial buy-in. Additionally, our strategy targeted multiple levels of the delivery system, which included frequent meetings with key provider stakeholders (eg, GYN-ONC, nutrition, and social work) regarding logistics (eg, triaging), content build (eg, dispositions and needs checklist items), roles, training, and for educational purposes to create initiative awareness/increase uptake. Aside from EPIS, other implementation frameworks used previously in the integration of PRO measures include the Knowledge-to-Action framework, Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), and integrated Promoting Action Research in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework.50,51 Advantages unique to using EPIS include the emphasis on iterative strategies and inner/outer contextual factors throughout different phases of implementation, the latter of which is also true for CFIR.52 Although frameworks such as EPIS place more emphasis on implementation activities (eg, continual trainings, stakeholder meetings, and informing EHR integration processes), future work incorporating/combining multiple models that can also emphasize evaluation such as Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) and CFIR as well as those used for widespread dissemination such as the Framework for Spread are crucial.52 Adhering to a strategy informed by implementation science will facilitate our ability to accelerate translation, develop scalability, and promote sustainability of the My Wellness Check initiative.48

We note limitations to the implementation of this quality improvement initiative. My Wellness Check was first launched in the GYN-ONC clinic at SCCC, which limited our sample to women only. Previous research has noted differences in attitudes, reported needs (eg, dietary problems), and distress by sex in the cancer setting,53 with women experiencing higher levels of health problems (including nutritional problems), depression, anxiety, distress, and lower HRQoL.54,55 Additionally, adherence to distress screening protocols has been shown to be better for female patients with cancer.56 Therefore, this could limit the generalizability of our implementation to other clinics and patient populations throughout the University of Miami Health System. Future research needs to identify differences in patient sociodemographic/clinical profiles in regards to completion of PRO measures.57 Training documents have been developed to adapt the initiative procedures for implementation to other clinics systemwide, taking into account their specific workflow processes and needs. Moreover, protocols were modified, taking into consideration COVID-19 contingencies and new limited-contact clinic workflows. Full integration of PROs within the EMR and CAT technology is costly and complex, and may vary according to the current institutional infrastructures and additional interfaces needed; however, the costs to maintaining an independent PRO system may be higher.16,58

In conclusion, our results demonstrate promising feasibility and initial acceptability in implementing My Wellness Check within an ambulatory oncology clinic with a diverse patient population. In using the EPIS framework, strong institutional, administrative, and clinician support were instrumental to the successful implementation of this initiative. Although patient engagement was modest among both English and Spanish speakers alike, future systemwide implementation and marketing efforts can improve uptake. Future efforts focus on tracking the impact of this initiative on PROs, patient-identified needs, and system-level outcomes (eg, emergency room/urgent care visits, hospital admissions, days of stay, unscheduled visit count, etc). Additionally, the EPIS framework will be used to guide sustainability efforts. Data received from pilot implementation will be used to develop reports for presentations to clinical operations leadership and stakeholders to justify expansion into other test clinics. The results from the initiative can be used in the planning and implementation of a systemwide EHR-based symptom and needs screening, monitoring, and referral model. My Wellness Check data generated will be used to inform and guide patient-centered care, clinical decision making, and health policy decisions.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Health System Stakeholders

TABLE A2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Patients Who Initiated the Assessment

Frank J. Penedo

Employment: Blue Note Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Blue Note Therapeutics

Matthew P. Schlumbrecht

Consulting or Advisory Role: Tesaro

Jessica MacIntyre

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer

Honoraria: Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: Pfizer

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

This study was funded, in part, by grants: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R18HS026170-01 [S.F.G. and F.J.P.; Co-PIs]) and National Cancer Institute (P30 CA 240139 [Nimer, S.: PI; Penedo, F.: Cancer Control Co-Lead]).

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Deidentified data from this study are not available in a public archive. Deidentified data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by e-mailing the corresponding author.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Frank J. Penedo, Patricia I. Moreno, Vandana Sookdeo, Akina Natori, Carmen Calfa, Jessica MacIntyre, Sofia F. Garcia

Administrative support: Jessica MacIntyre

Collection and assembly of data: Frank J. Penedo, Vandana Sookdeo, Akina Natori, Carmen Calfa

Data analysis and interpretation: Frank J. Penedo, Heidy N. Medina, Patricia I. Moreno, Vandana Sookdeo, Akina Natori, Cody Boland, Matthew P. Schlumbrecht, Carmen Calfa, Tracy E. Crane, Sofia F. Garcia

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Implementation and Feasibility of an Electronic Health Record–Integrated Patient-Reported Outcomes Symptom and Needs Monitoring Pilot in Ambulatory Oncology

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Frank J. Penedo

Employment: Blue Note Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Blue Note Therapeutics

Matthew P. Schlumbrecht

Consulting or Advisory Role: Tesaro

Jessica MacIntyre

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer

Honoraria: Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: Pfizer

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society : Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2019-2021. Atlanta, GA, American Cancer Society, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benedict C, Penedo FJ: Psychosocial interventions in cancer, in Carr BI, Steel J. (eds): Psychological Aspects of Cancer. New York, NY, Springer, 2013, pp 221-250 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland J: NCCN practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distress. Oncology 13:113-147, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) National Cancer Policy Board , Hewitt M, Herdman R, Holland J. (eds): Meeting Psychosocial Needs of Women with Breast Cancer. Washington, DC, National Academies Press (US), 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting , Adler NE, Page AEK. (eds): Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC, National Academies Press (US), 2008. The National Academies Collection: Reports Funded by National Institutes of Health [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Commission on Cancer : Optimal Resources for Cancer Care (2020 Standards), 2019. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/cancer/coc/optimal_resources_for_cancer_care_2020_standards.ashx [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donovan KA, Deshields TL, Corbett C, et al. : Update on the implementation of NCCN guidelines for distress management by NCCN member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17:1251-1256, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. (eds): Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane, 2021. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. : Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 318:197-198, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. : Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 34:557-565, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia SF, Wortman K, Cella D, et al. : Implementing electronic health record-integrated screening of patient-reported symptoms and supportive care needs in a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 125:4059-4068, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horn ME, Reinke EK, Mather RC, et al. : Electronic health record–integrated approach for collection of patient-reported outcome measures: A retrospective evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res 21:626, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner LI, Schink J, Bass M, et al. : Bringing PROMIS to practice: Brief and precise symptom screening in ambulatory cancer care. Cancer 121:927-934, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papuga MO, Dasilva C, McIntyre A, et al. : Large-scale clinical implementation of PROMIS computer adaptive testing with direct incorporation into the electronic medical record. Health Syst (Basingstoke) 7:1-12, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold HT, Karia RJ, Link A, et al. : Implementation and early adaptation of patient-reported outcome measures into an electronic health record: A technical report. Health Informatics J 26:129-140, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snyder C, Wu AW: Users’ Guide to Integrating Patient-Reported Outcomes in Electronic Health Records. Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University, 2017. https://dcricollab.dcri.duke.edu/sites/NIHKR/KR/17-10-13%20GR-Slides.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Browne JP, Cano SJ, Smith S: Using patient-reported outcome measures to improve health care: Time for a new approach. Med Care 55:901-904, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gensheimer SG, Wu AW, Snyder CF: Oh, the places we'll go: Patient-reported outcomes and electronic health records. Patient 11:591-598, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson TA, Anderson B, Bian J, et al. : Planning for patient-reported outcome implementation: Development of decision tools and practical experience across four clinics. J Clin Transl Sci 4:498-507, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. : Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 22:714-724, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis K, Yount S, Del Ciello K, et al. : An innovative symptom monitoring tool for people with advanced lung cancer: A pilot demonstration. J Support Oncol 5:381-387, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lattie EG, Bass M, Garcia SF, et al. : Optimizing health information technologies for symptom management in cancer patients and survivors: Usability evaluation. JMIR Form Res 4:e18412, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knobf MT, Ferrucci LM, Cartmel B, et al. : Needs assessment of cancer survivors in Connecticut. J Cancer Surviv 6:1-10, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moadel AB, Morgan C, Dutcher J: Psychosocial needs assessment among an underserved, ethnically diverse cancer patient population. Cancer 109:446-454, 2007. (2 suppl) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Guadagnoli E, et al. : Patients' perceptions of quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity, and language. J Clin Oncol 23:6576-6586, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno PI, Ramirez AG, San Miguel-Majors SL, et al. : Unmet supportive care needs in Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors: Prevalence and associations with patient-provider communication, satisfaction with cancer care, and symptom burden. Support Care Cancer 27:1383-1394, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penedo FJ, Dahn JR, Shen BJ, et al. : Ethnicity and determinants of quality of life after prostate cancer treatment. Urology 67:1022-1027, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL: Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: A systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv 5:191-207, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butow PN, et al. : Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 12:1240-1248, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones N, Marks R, Ramirez R, et al. : 2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country. United States Census Bureau, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. : Distress management. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 11:190-209, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16:606-613, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. : The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol 63:1179-1194, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yanez B, Pearman T, Lis CG, et al. : The FACT-G7: A rapid version of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) for monitoring symptoms and concerns in oncology practice and research. Ann Oncol 24:1073-1078, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epic Systems Corporation : App Orchard. https://apporchard.epic.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cella D, Gershon R, Lai JS, et al. : The future of outcomes measurement: Item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Qual Life Res 16:133-141, 2007. (suppl 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai JS, Cella D, Choi S, et al. : How item banks and their application can influence measurement practice in rehabilitation medicine: A PROMIS fatigue item bank example. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92:S20-S27, 2011. (10 suppl) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai JS, Cella D, Dineen K, et al. : An item bank was created to improve the measurement of cancer-related fatigue. J Clin Epidemiol 58:190-197, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cella D, Choi S, Garcia S, et al. : Setting standards for severity of common symptoms in oncology using the PROMIS item banks and expert judgment. Qual Life Res 23:2651-2661, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM: Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health 38:4-23, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, et al. : Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implement Sci 14:1, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. : How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med 36:452-457, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E: Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 5:80-92, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braun V, Clarke V: Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77-101, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang R, Burgess ER, Reddy MC, et al. : Provider perspectives on the integration of patient-reported outcomes in an electronic health record. JAMIA Open 2:73-80, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan ES, Rice N, Kingston E, et al. : A national survey of oncology survivors examining nutrition attitudes, problems and behaviours, and access to dietetic care throughout the cancer journey. Clin Nutr ESPEN 41:331-339, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trujillo EB, Claghorn K, Dixon SW, et al. : Inadequate nutrition coverage in outpatient cancer centers: Results of a national survey. J Oncol 2019:7462940, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Check DK, Zullig LL, Davis MM, et al. : Improvement science and implementation science in cancer care: Identifying areas of synergy and opportunities for further integration. J Gen Intern Med 36:186-195, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith JD, Garcia SF, Penedo FJ, et al. : An effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial for informatics-based cancer symptom management. J Clin Oncol 38, 2020. (29 suppl; abstr 236) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Howell D, Rosberger Z, Mayer C, et al. : Personalized symptom management: A quality improvement collaborative for implementation of patient reported outcomes (PROs) in ‘real-world’ oncology multisite practices. J Patient Rep Outcomes 4:47, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stover AM, Haverman L, van Oers HA, et al. : Using an implementation science approach to implement and evaluate patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) initiatives in routine care settings. Qual Life Res 30:3015-3033, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanson RF, Self-Brown S, Rostad WL, et al. : The what, when, and why of implementation frameworks for evidence-based practices in child welfare and child mental health service systems. Child Abuse Negl 53:51-63, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark K, Bergerot CD, Philip EJ, et al. : Biopsychosocial problem-related distress in cancer: Examining the role of sex and age. Psychooncology 26:1562-1568, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, et al. : Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord 141:343-351, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Traeger L, Cannon S, Keating NL, et al. : Race by sex differences in depression symptoms and psychosocial service use among non-Hispanic black and white patients with lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:107-113, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zebrack B, Kayser K, Sundstrom L, et al. : Psychosocial distress screening implementation in cancer care: An analysis of adherence, responsiveness, and acceptability. J Clin Oncol 33:1165-1170, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Natori A, Sookdeo VD, Koru-Sengul T, et al. : Predictors of adherence to patient reported outcomes and psychosocial needs questionnaire in a culturally diverse ambulatory oncology setting: The My Wellness Check Program. J Clin Oncol 39, 2021. (28 suppl; abstr 173) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu AW, Jensen RE, Salzburg C, et al. : Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records: Including Case Studies Landscape Review Prepared for the PCORI National Workshop to Advance the Use of PRO Measures in Electronic Health Records. Atlanta, GA, 2013. http://www.pcori.org/assets/2013/11/PCORI-PRO-Workshop-EHR-Landscape-Review-111913.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data from this study are not available in a public archive. Deidentified data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by e-mailing the corresponding author.