Abstract

Integrated service delivery, providing coordinated services in a convenient manner, is important in HIV prevention and treatment for adolescents as they have interconnected health care needs related to HIV care, sexual and reproductive health and disease prevention. This review aimed to (1) identify key components of adolescent-responsive integrated service delivery in low and middle-income countries, (2) describe projects that have implemented integrated models of HIV care for adolescents, and (3) develop action steps to support the implementation of sustainable integrated models. We developed an implementation science-informed conceptual framework for integrated delivery of HIV care to adolescents and applied the framework to summarize key data elements in ten studies or programs across seven countries. Key pillars of the framework included (1) the socioecological perspective, (2) community and health care system linkages, and (3) components of adolescent-focused care. The conceptual framework and action steps outlined can catalyze design, implementation, and optimization of HIV care for adolescents.

Keywords: Integrated care, Adolescents, HIV care, Implementation science

Introduction

Adolescence is an important period of growth and development, during which the transition from childhood to adulthood involves not only physical and psychological changes but also significant life experiences like a new relationship, job, or school; a deepening sense of identity; and making decisions in a society of competing demands [1]. Although most adolescents have interconnected needs, the intersection of their health needs with the HIV epidemic requires effective interventions to reduce HIV risk, enhance early knowledge of HIV status through testing, improve adherence to treatment and offer comprehensive health services to ensure overall well-being [2–4].

Different adolescent groups have their own unique health needs [5]. Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) living with and at risk of HIV infection not only seek HIV testing, education, and treatment services but also a range of other services for sexual and reproductive health, such as contraception, treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), options to receive confidential counseling, and preventive services such as the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccination [2, 6, 7]. Besides HIV prevention and care services, young transgender men and women usually seek transgender-specific services to address medical needs related to their gender identity [8]. Adolescent boys and young men living with and at risk of HIV infection also require tailored health services, such as condom promotion and male circumcision, along with STI treatment and confidential counseling.

Studies have acknowledged the need for adolescent-responsive integrated services [9], and several projects, including the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) DREAMS (Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored and Safe) program have utilized an integrated service model [10]. The DREAMS model includes a comprehensive set of services including condom distribution, contraceptive services and care for those exposed to gender-based violence. A recent study in Zambia found that AGYW expressed a preference for a one-stop-shop for both HIV and sexual and reproductive health services. Additionally, they valued having access to care around school or other commitments, assurances of confidentiality and privacy, friendly staff who respects adolescents, and knowledgeable providers that can help adolescents to improve their health outcomes [11]. Combining gender-affirming care to HIV prevention may improve HIV prevention outcomes among transgender women, especially youth [12, 13]. By incorporating direct preferences from adolescents, integrated services can be better targeted with adolescent-focused characteristics to meet the complex needs of adolescents [11]. Although many of these health services are offered directly to adolescents in the clinic setting, offering support in the community setting and reinforcing beneficial strategies through public policy may help to enhance linkages to care and optimize programs for improved HIV outcomes [7]. Furthermore, implementation science based frameworks and methods should be further reinforced in adolescent studies to successfully embed evidence-based interventions and strategies into the practice setting.

Although adolescent-responsive integrated service delivery approaches have been advocated, there is no comprehensive assessment of past and ongoing projects to guide the adoption of optimal models. The purpose of this study is to offer guidance for future program design, implementation and evaluation of adolescent responsive integrated programs. First, we present an implementation science-informed conceptual framework to support the development of comprehensive adolescent-responsive integrated service delivery models in HIV care. Secondly, we summarized characteristics of selected projects that have implemented integrated delivery of health services targeted at adolescents living with and at risk of HIV infection to catalogue features of existing integrated models to identify implementation gaps. Third, we develop action steps to support the implementation and evaluation of adolescent-responsive integrated programs drawing on implementation science theoretical approaches focusing on implementation outcomes and determinants.

Methods

Develop Conceptual Framework

We used a three-step process to develop a tailored conceptual framework focused specifically on the integrated delivery of care to adolescents within HIV care programs. First, we identified key themes on barriers and preferences related to health care service delivery from prior work done by this team to inform this conceptual framework [11]. We had previously conducted interviews and focus groups with 109 AGYW aged 10 to 24 years in Zambia as part of formative research conducted for planning an implementation science trial [7]. The participants included both AGYW living with HIV and those at risk of HIV infection. Furthermore, we undertook two rounds of consultation with the six-member youth advisory board that consisted of both young men and women and was initiated for the above-mentioned study. We developed detailed guides and conducted systematic qualitative analysis to identify emergent themes. These details are included in a recently published manuscript [11]. Second, we created an initial framework that was presented to implementation scientists and researchers attending the Joint Adolescent HIV Prevention and Treatment Implementation Science Alliance (AHISA) and Prevention and Treatment through a Comprehensive Care Continuum for HIV-affected Adolescents in Resource Constrained Settings (PATC3H) meeting in February 2020. The AHISA consortium and the PATC3H program include teams of researchers and implementers working to advance implementation science-based research focused on adolescents and young adults living with or at risk of HIV infection. Feedback received through interactive discussion was incorporated to create an updated framework. Third, we convened a virtual forum via Zoom with individuals implementing health care service delivery programs for adolescents living with and at risk of HIV infection (including the manuscript team representing Brazil, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia) to clarify key themes and further refine the framework components. Through this forum, we also adapted guidance published by the World Health Organization (WHO) to highlight components of adolescent-responsive care that should be included to implement these programs successfully.

Review Selected Projects

We initiated a review of programs to identify examples of adolescent-targeted projects to summarize models currently being implemented. Our inclusion criteria were projects that targeted adolescents at risk of or living with HIV for HIV testing or HIV treatment, respectively, and integrated at least one non-HIV-related service. Health care services could include reproductive health, new-born care, gender-affirming care, mental health, substance use services, services for gender-based violence and violence against children, and preventive care (including screenings and vaccinations). We asked study co-authors to submit research projects from their respective countries. Using the conceptual framework, we identified key data elements and measures to compare the selected projects. We report on the populations targeted, socio-ecological levels addressed, and services provided. Given the importance of program setting for implementation science evaluations, we also provide details on contextual factors including HIV prevalence, income level and guidelines related to services for adolescents living with and at risk of HIV infection.

Create Action Steps

In further discussion during the virtual forum described above, participants identified action steps and components for planning, implementing and evaluating integrated adolescent-responsive programs. These were summarized in an “Action Plan” to support adoption of integrated adolescent services.

Framework for Developing and Implementing Adolescent-Focused Integrated Modular Services

The major thematic areas identified from the feedback with adolescents and young adults and consultation with HIV program implementers included: (1) the importance of incorporating multilevel barriers that influence adolescent care seeking behavior and the use of services; (2) community-clinic linkages that include education and other community engagement; (3) integration of services and referral pathways for specialty care; and (4) the importance of ensuring services that are tailored to adolescents. Figure 1 presents the framework that we created for developing and optimizing Adolescent-focused Integrated Modular Services (AIMS) that includes three key pillars based on thematic areas identified. The first pillar, “the socio-ecological perspective,” demonstrates that adolescents operate in an interrelated network that includes many stakeholders who can positively and negatively influence adolescent well-being and that barriers to optimal care exist at multiple levels. Interventions and implementation strategies based on the socio-ecological perspectives can be targeted at the individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy levels. As barriers faced by adolescents can be experienced at each of these levels, successful programs will need to implement multilevel strategies to address these barriers. The second pillar, “community and health care system linkages,” includes processes and features in the community and health care setting and linkages and feedback mechanisms. Programs within the community setting, such as youth clubs, can be leveraged to encourage linkages to integrated adolescent-responsive services within the health care system and can provide referrals to other services or supports within the health system. Integrated services can be delivered using a modular approach that will allow services to be tailored based on ‘who’, which cohort of adolescents, is being targeted. This can guide ‘what’ services are offered, ‘where’ the services are provided, and ‘how’ and ‘when’ the services are offered. The third pillar, “adolescent-focused care,” includes seven tailored elements of care that ensure interventions and services appropriately meet the unique needs of adolescents. These adolescent-focused care elements include adolescent participation, services tailored to adolescents’ level of health literacy, adolescent-responsive services, built-in transitions with pediatric and adult services, age-appropriate care, equity and inclusiveness, and appropriately trained providers. The definitions of key concepts from the framework are included in Table 1. The framework also includes contextual factors, which are features external to the adolescent-responsive program that may shape service delivery and sustainability. Altogether, the components of the AIMS framework relate to each other by including both internal and external attributes across multiple levels of society that can influence the implementation and uptake of adolescent-responsive integrated services. The AIMS framework provides a structured approach to design and develop integrated programs for adolescents that can be tested using implementation science-based trials.

Fig. 1.

Framework for developing and implementing adolescent-focused integrated modular services (AIMS)

Table 1.

Definitions of concepts in AIMS framework

| Construct | Definition and description |

|---|---|

| Socio-ecological perspective | |

| Individual | Knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy |

| Interpersonal | Peer group, friends, family, support groups |

| Organizational | Health system facilities, schools, youth associations |

| Community | Safe spaces, cultural attitudes, transportation |

| Public Policy | Guidelines, laws, and procedures at the national, regional, and local levels |

| Integrated care in the community and health care system | |

| Where is it provided? | Whether service is offered in the community or health care setting and by facility type (e.g., public health centers, private clinics, pharmacies, mobile clinics, youth centers and schools) |

| Who is the target cohort? | Specific cohorts could include specific gender (e.g., girls only) or special populations (e.g., HIV-positive adolescents only) |

| What type of services? | Could include a range of services, including sexual reproductive health, HIV testing, HIV treatment, and mental health or substance abuse counseling |

| How and when is it delivered? | Details on who is delivered the required services, timing of clinic opening hours, clinic location, use of eHealth or mHealth |

| Adolescent-focused care | |

| Adolescent participation | Adolescents are involved in planning, monitoring and evaluating health services and in decisions regarding their own care, as well as in certain appropriate aspects of service provision |

| Tailored to level of health literacy | The health facility implements systems to ensure that adolescents are knowledgeable about their own health and they know where and when to obtain health services |

| Adolescent-responsive services | The health facility has convenient operating hours, provides a welcoming and clean environment and maintains privacy and confidentiality. It has the equipment, medicines, supplies and technology needed to ensure effective service provision to adolescents |

| Built-in transitions with pediatric and adult services | The health facility implements systems to ensure adolescents can access the appropriate package of pediatric services, including through referral linkages and outreach along with planning, coordinating, and transitioning to adult services |

| Age-appropriate care | Adolescence is a time of transition and individual needs should be considered through this transition; ethical, legal, and cultural factors will have to be considered to ensure appropriate care is provided. For example, at what age issues related to sexual and reproductive health are appropriate |

| Equity and inclusiveness | The health facility provides quality services to all adolescents irrespective of their ability to pay, age, gender, marital status, education level, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, or other characteristics |

| Appropriately trained providers | Health care providers demonstrate the technical competence required to provide effective health services to adolescents. Both health care providers and support staff respect, protect, and fulfil adolescents’ rights to information, privacy, confidentiality, non-discrimination, non-judgmental attitude, and respect |

AIMS adolescent-focused integrated modular services

Summary of Selected Programs Using Aims Framework

We identified adolescent HIV programs with integrated service delivery approaches in seven countries. Selected contextual factors of the countries where the programs are implemented are presented in Table 2. Six out of the seven countries included are located in Sub-Saharan Africa (Zambia, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, Tanzania, and South Africa) while the remaining country (Brazil) is located in South America. We provide the income classification, along with the income level, for each country as this may impact the resources available for adolescent-responsive programs [14, 15]. Uganda is classified as a low-income country; Zambia, Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania are classified as lower-middle income countries; and Brazil and South Africa are classified as upper-middle income countries. The adolescent (ages 15–24) HIV prevalence across the included countries (excluding Brazil as no estimates were available) ranges from a low of 0.4% (Nigeria) to a high of 6.9% (South Africa), and the adolescent HIV incidence (per 1000 aged 15–24) ranges from 0.57 (Nigeria) to 8.97 (South Africa) [16]. Among Brazilian young transgender women, HIV prevalence was 24.5% [5]. Updated adolescent HIV guidelines were all developed within the last 5 years for each of the countries [17–23]. Both Nigeria and Uganda’s guidelines included various elements from the conceptual framework, including adolescent-responsive services, the socio-ecological perspective, gender, community engagement, and health literacy. The most recently available general health guidelines for adolescents were largely developed between 2012 and 2018 for each country, with three countries (Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda) explicitly including elements of adolescent-focused care from the framework [24–30]. Adolescent multi-sectoral guidelines were also found for Kenya, Brazil, South Africa and Tanzania and included HIV education in schools and HIV guidelines for key and vulnerable populations [31–36].

Table 2.

Setting of countries included in review (contextual factors in the AIMS framework)

| Country | Programs that link to or provide adolescent care | Geographic location | Income category [14] [per capita income—USD] [15] |

Adolescent HIV prevalence (15–24 years) [16] [range] |

Adolescent HIV incidence per 1000 (15–24 years) [16] [range] |

National guidelines established (Latest year for each) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent HIV guidelines | Adolescent general health guidelines | Adolescent multi-sectoral guidelines | ||||||

| Zambia | DREAMS, SHIELD/IWC | Sub-Saharan Africa |

Lower–middle [$1305] |

4.2 [2.5–5.6] |

6.35 [4.09–8.53] |

2020 [17] | 2015 [24] | – |

| Kenya | DREAMS | Sub-Saharan Africa |

Lower–middle [$1817] |

1.7 [1.2–2.2] |

1.25 [0.73–2.15] |

2018 [18] |

2014 [25] (Adolescent-responsive services, community engagement, transition with pediatric and adult services) |

2016 [31] (Adolescent-responsive services, community engagement) |

| Nigeria | OTZ, Zvandiri Program | Sub-Saharan Africa |

Lower–middle [$2230] |

0.4 [0.2–0.7] |

0.57 [0.27–1.14] |

2020 [19] (Adolescent-responsive services, socio-ecological perspective, integrated services, gender) |

2018 [26] (Adolescent participation, community engagement) |

|

| Uganda | DREAMS, YAPS, G-ANC | Sub-Saharan Africa |

Low [$2220] |

1.9 [1.2–2.5] |

1.63 [1.06–2.24] |

2020 [20] (Community engagement, health literacy) |

2012 [27] (Adolescent-responsive services) |

|

| Brazil | BeT | South America |

Upper–middle [$8717] |

Overall estimates not available 24.5% (among young transgender women) [5] |

No estimates are available | 2018 [21] | 2018 [28] |

2010 [32] 2013(HIV specific) [33] |

| Tanzania | DREAMS, SYV | Sub-Saharan Africa |

Lower–middle [$1,122] |

1.7 [1.0–2.3] |

1.86 [1.16–2.42] |

2019 [22] National HIV guidelines |

2018 [29] |

2002 [34] 2017 [35] |

| South Africa | Beyond Zero, IMARA, DREAMS | Sub-Saharan Africa |

Upper–middle [$6,748] |

6.9 [3.0–10.7] |

8.97 [4.08–14.17] |

2020 [23] | 2017 [30] | 2020 [36] |

AIMS adolescent-focused integrated modular services; DREAMS Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, mentored and safe; SHIELD-IWC support for HIV integrated education, linkages to care, and destigmatization/integrated wellness care; OTZ operation triple zero; YAPS young people and adolescent peer support; G-ANC Group Antenatal Care/Postnatal Care; BeT “Brillar e Transcender” (English: “Shine and Transcend”); SYV Sauti Ya Vijana; IMARA informed motivated aware responsible adolescents and adults

Across the seven countries, we identified 10 adolescent programs which included DREAMS; Support for HIV Integrated Education, Linkages to care, and Destigmatization/Integrated Wellness Care (SHIELD/IWC); Operation Triple Zero (OTZ); Zvandiri Program; Young People and Adolescent Peer Support (YAPS); Group Antenatal Care/Postnatal Care (G-ANC); “Brillar e Transcender” (BeT; English: “Shine and Transcend”); Sauti Ya Vijana (SYV); Beyond Zero; and IMARA (Informed Motivated Aware Responsible Adolescents and Adults) [7, 10, 37–44]. The socio-ecological perspective, first pillar in the AIMS framework, is presented in Table 3 for the programs identified.. Five of the selected programs focused specifically on AGYW (DREAMS, SHIELD/IWC, G-ANC, Beyond Zero, and IMARA), while one program focused on young transgender women ages 18 to 24 (BeT). The other four programs included both adolescent boys and girls largely between the ages of 10 to 24 years (OTZ, Zvandiri Program, YAPS, and SYV). Across the interpersonal level of the socio-ecological perspective, nine of the ten programs included caregivers, and many also included peers, support groups, and partners. Organizationally, seven programs were largely at the health clinic/provider level, one was based out of schools, and another out of the Ministries of Health, Education, and Sports program. To foster linkages to the services offered, most programs included various community mobilization programs, peer navigators, campaigns, digital outreach, and other support networks. At the public policy level, most projects were influenced by or operated in accordance with a national policy such as Ministry of Health and other national guidelines.

Table 3.

Socio-ecological perspectives of selected adolescent programs (first pillar in AIMS framework)

| Program name | Socio-ecological levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Interpersonal | Organizational | Community | Public policy | |

| DREAMS | AGYW ages 10–24 | AGYW’s partners, Caregivers/family | School-based programs | Community mobilization and norms change programs | Public/private partnerships across member countries |

| SHIELD/IWC | AGYW ages 10–25 | Caregivers/family | Health clinics/clinic providers | Peer navigators/community support | Ministry of Health and national guidelines |

| OTZ | Adolescents and young people (AYP) ages 10–24 | Peers living with HIV, caregivers, AYP support groups | Health clinics/clinic providers | Enrollment in the Orphans and Vulnerable Children’s program | National HIV and Adolescent and Youth Friendly Health Services (AYFHS) guidelines |

| Zvandiri Program | Adolescents ages 10–19 years | Peers, caregivers, family, support groups | Health clinic/clinic providers | Linkages between community and facilities, Radio program engaging adolescents, HIV self-testing in the community | National HIV and AYFHS guidelines |

| YAPS | Adolescents and young people (girls and boys) ages 10–24 years | Care givers, peers, family members, sexual partners | Ministries of Health, Gender, Labour and Social Development, and education and sports | Village health teams, local council, para-social workers, paralegals, community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, religious institutions, schools, people living with HIV networks | National Adolescent Health Policy and service standards; Consolidated guidelines for prevention and treatment of HIV; National Guidelines for Differentiated service delivery |

| G-ANC | Pregnant and lactating AGYW ages 15–24 years | Care givers, peers, family members, sexual partners | Health care workers at health facilities | AGYW safe spaces in the community, community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, paralegals | National Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCAH) Guidelines |

| BeT | Young transgender women ages 18–24 | None | Health clinics/clinic providers | Anti-stigma campaign/Peer health digital navigation | Ministry of Health and National PrEP implementation project |

| SYV Tanzania | 10–24 years with a focus on 15–24 years (AYA living with HIV) | Caregivers/supportive adults | Adolescent HIV clinics | Peer group leaders and youth community advisory board | Engagement with MOH with policy brief to influence importance of adolescent mental health in HIV prevention and treatment programming |

| Beyond Zero | AGYW 15–24 years old | Teens and caregivers | Health clinics | Return to school, economic strengthening, opportunities for bursaries, CSE institutional support, academic support | Operates in 3 provinces in South Africa with local partners on the ground in these communities |

| IMARA | AGYW 15–19 years old | Family based, with a focus on Female care givers, | Family based programs, Lay facilitators delivering the intervention | Gender dynamics, partner relationships, HIV stigma and discrimination | Engagement with Provincial department of health, social development |

AIMS Adolescent-Focused Integrated Modular Services; DREAMS Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored and Safe; SHIELD-IWC Support for HIV Integrated Education, Linkages to care, and Destigmatization/Integrated Wellness Care; OTZ Operation Triple Zero; YAPS Young People and Adolescent Peer Support; G-ANC Group Antenatal Care/Postnatal Care; BeT “Brillar e Transcender” (English: “Shine and Transcend”); SYV Sauti Ya Vijana; IMARA Informed Motivated Aware Responsible Adolescents and Adults; AGYW Adolescents Girls and Young Women; AYP Adolescents and Young People; AYFHS Adolescent and Youth Friendly Health Services

Health services provided along with the community-health system linkages, thesecond pillar in the AIMS framework, are listed in Table 4. Each program offered a range of health services tailored toward the needs of the adolescents included in each program. These services generally included HIV prevention and treatment services (e.g., HIV testing and counseling, pre-exposure prophylaxis [PrEP], and adherence counseling), and some also included family planning services (e.g., condom promotion, contraceptives, pregnancy testing) and adolescent-specific days or hours. Additionally, antenatal and postnatal services (one program), mental health (one program), HPV vaccination (one program), or other supportive services like education subsidies or literacy trainings were also provided. Eight programs also offered community-health system linkages, including peer navigation, youth clubs, school programs, non-governmental organization referrals, or caregiver programs.

Table 4.

Community and healthcare system services and linkages of selected adolescent programs (second pillar in AIMS framework)

| Program name | HIV Testing/counseling | Anti-retroviral adherence counseling | Disclosure counseling | PrEP | Condom promotion | Pregnancy testing/SRH services | Peer navigation/support/mentorship | Educational programs | Other activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DREAMS | X | X | X | X (adolescents and caregivers) | Community/social media engagement, violence prevention and care | ||||

| SHIELD/IWC | X | X | X | X | X | X (adolescents and caregivers) | HPV vaccination, contraceptives, referrals | ||

| OTZ | X | X | X | X (adolescents and caregivers) | Age-band services, community/social media engagement, psychosocial support, viremia clinics | ||||

| Zvandiri Program | X | X | X | Age-band services, community/social media engagement | |||||

| YAPS Program | X | X | X | X | X | X (adolescents) | Age-band services, community/social media engagement, appointment monitoring, tracking and follow-up, school linkages | ||

| G-ANC | X (ANC/PNC care) | ||||||||

| BeT | X | X | X | X | Gender-affirming hormones, mental and endocrinological care | ||||

| SYV Tanzania | X | X | X (adolescents) | Mental health and life skills, referrals | |||||

| Beyond Zero | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | In school and out of school programs demand creation, and biomedical services |

| IMARA | X | X | X | X | X (family-based) | ART referrals, partner notification, STI testing and treatment, mental health education |

AIMS Adolescent-Focused Integrated Modular Services; PrEP pre-exposure prophylaxis; SRH Sexual and Reproductive Services; DREAMS Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored and Safe; SHIELD-IWC Support for HIV Integrated Education, Linkages to care, and Destigmatization/Integrated Wellness Care; OTZ Operation Triple Zero; YAPS- Young People and Adolescent Peer Support; G-ANC Group Antenatal Care/Postnatal Care; BeT “Brillar e Transcender” (English: “Shine and Transcend”); SYV Sauti Ya Vijana; IMARA Informed Motivated Aware Responsible Adolescents and Adults; HPV Human Papillomavirus; ART antiretroviral treatment; STI sexually transmitted infection

Adolescent-focused care elements, the third pillar of the AIMS framework, are presented in Table 5 for each of the included programs. All programs had some degree of adolescent participation through either a delivery or advisory role. Nine of the programs specifically tailored their content to the health literacy of the adolescents included. Eight programs specifically tailored their intervention to be adolescent-responsive by providing services with convenient opening hours, dedicating time and space for adolescents while maintaining privacy and confidentiality, and providing integrated services tailored towards the need of adolescents. Five programs offered built-in transitions with pediatric and adult services, all ten explicitly ensured age-appropriate care, seven programs included a focus on equity and inclusiveness (by age, gender, HIV status), and all ten ensured having appropriately trained providers.

Table 5.

Elements of adolescent-focused care among selected programs (third pillar in AIMS framework)

| Program name | Adolescent-focused care elements | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent participation | Tailored to level of health literacy | Adolescent-responsive services | Built-in transitions with pediatric and adult services | Age-appropriate care | Equity and inclusiveness | Appropriately trained providers | |

| DREAMS | X (delivery) | X | X (with referrals to facilities) | X | X | X (mentors receive training) | |

| SHIELD/IWC | X (advisory) | X | X (integrated) | X | X (age, gender, HIV status) | X (stigma, adolescent-responsive care) | |

| OTZ | X (delivery) | X | X (dedicated time & space) | X | X | X | |

| Zvandiri Program | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| YAPS Program | X (delivery) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| G-ANC | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| BeT | X | X | X | X | X (gender) | X | |

| SYV Tanzania | X (delivery) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Beyond Zero | X (advisory) | X | X | X | X (have other programs for men who have sex with men and transgender adults, 15–49 years | X (clinic staff and counsellors) | |

| IMARA | X | X | X | X | X (HIV status, sexually active and non-sexually active girls) | X (Nurse, adolescent trained counsellors, facilitators) | |

AIMS Adolescent-Focused Integrated Modular Services; DREAMS Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored and Safe; SHIELD-IWC Support for HIV Integrated Education, Linkages to care, and Destigmatization/Integrated Wellness Care; OTZ Operation Triple Zero; YAPS Young People and Adolescent Peer Support; G-ANC Group Antenatal Care/Postnatal Care; BeT “Brillar e Transcender” (English: “Shine and Transcend”); SYV Sauti Ya Vijana; IMARA Informed Motivated Aware Responsible Adolescents and Adults

Action Plan for Implementing and Evaluating Aims Programs

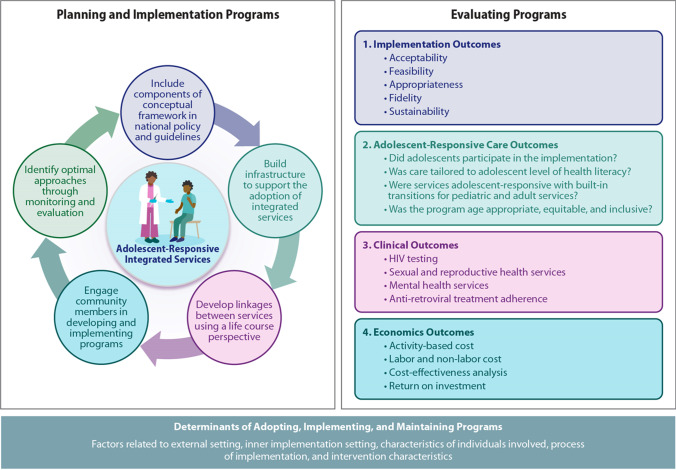

Key actions to support the adoption of adolescent-responsive integrated services for populations living with and at risk of HIV infection are presented in Fig. 2. The actions consist of (1) including components of the AIMS conceptual framework in national policy and guidelines; (2) building infrastructure to support the adoption of integrated services; (3) developing linkages between services using a life course perspective; (4) engaging community members in developing and implementing programs; and (5) identifying optimal approaches through program monitoring and evaluation. These actions are essential components to ensure clear, policy-oriented steps are in place to support the processes required to implement, assess, and modify approaches to ensure sustainable program models that deliver optimized services to adolescents.

Fig. 2.

Action plan to support adoption of adolescent-responsive integrated services for HIV-affected populations using an implementation science approach

The first step is to ensure the inclusion of key components of the AIMS conceptual framework for integrated adolescent-responsive services in national policy and guidelines. National policy should acknowledge the multiple levels of influence on adolescent health, adopt a process to foster community-clinic linkages, identify services that will be integrated, develop referral pathways for other specialty services, and support all elements of adolescent-focused care such as adolescent participation and education materials tailored to age-appropriate health literacy levels.

Second, it is essential to build infrastructure to support the adoption of integrated services. HIV care services for adolescents should be strengthened along six key indicators, identified by WHO [45], which make for strong health-systems, including service delivery, governance, health workforce, information systems, medical products (e.g., medicines, vaccines, and technology), and financing.

The third action step is to develop linkages between services using a life course perspective. Adolescent care requires intentional planning to ensure smooth transitions from pediatric care to adult care. These transitions should focus beyond HIV services to allow for transitions in integrated services such as sexual and reproductive health.

Fourth, community members and key stakeholders should be engaged in developing and implementing programs. Adolescents, their caregivers, and community leaders can offer valuable insights to generate demand for services offered, and providers involved in care processes can help design appropriate services to ensure adolescent-responsive supply-side procedures.

Fifth, a critical component is ensuring a continual learning system by identifying optimal approaches through monitoring and evaluating the implementation processes and outcomes.

Figure 2 also provides four components that should be included in comprehensive implementation science-based evaluations comprising of implementation outcomes, adolescent-focused care outcomes, relevant clinical outcomes and economics outcomes. The evaluation components specifically include adolescent responsive measures to assess implementation of adolescent-focused care identified in Fig. 1. Furthermore, the action plan highlights the importance of considering external and internal determinants of successfully adapting, implementing and maintaining programs.

Discussion

We have presented a comprehensive framework to guide the design and implementation of adolescent-responsive integrated services. The AIMS framework includes three pillars: the socioecological perspective to highlight the importance of multilevel strategies; modular set of integrated services in the community and clinic settings that can be tailored to the target cohort and implementation setting; and comprehensive set of practices to deliver adolescent-focused care. Adolescents living with and at risk of HIV infection need services beyond those directly related to HIV [46]. Support services such as those related to sexual health and reproductive services and mental health can supplement efforts to prevent and treat HIV among adolescents. Fortunately, there is growing recognition of the need for integration and there are many ongoing programs and initiatives, including those reviewed in this study. Examples of additional programs include Ariel adherence clubs, REACH (Re-Engage Adolescents and Children with HIV) and Baylor College of Medicine International Pediatric AIDS Initiative Teen Club Programme [47, 48]. The AIMS framework offers standardized components and definitions to compare and evaluate programs delivering services to adolescents living with or at risk of HIV infection to optimize integrated care delivery.

Several of the guidelines reviewed for this study include components of adolescent-responsive care but additional advocacy is required to ensure the comprehensive inclusion of components across all guidelines. Importantly, guidelines do not specifically address integrated delivery of services for adolescents and action steps based on implementation science approaches outlined in this manuscript can support the implementation and evaluation of integrated service delivery programs. Furthermore, COVID-19 has disrupted health care access and reduced number of in-person visits which has highlighted the importance of offering integrated one-stop-shop services to maximize the reach of care essential for adolescent wellbeing [49]. The AIMS framework offers structured components to support the inclusion of adolescent-responsive integrated care models in guidelines for ameliorating COVID-19 pandemic impacts on adolescents living with or at risk of HIV infection. As indicated in the AIMS framework, adolescent participation is essential in the design, implementation and evaluation of these programs [50].

This review of selected projects focused on implementing integrated services for adolescents at risk of and living with HIV and identified several gaps that should be addressed in future programs and studies. First, research is needed to identify the appropriate mix of services for the targeted population in terms of what services should be offered in a single visit or in one setting and which specialty services should be provided via referrals. Adolescent girls and adolescent boys each require a different service mix whereas other groups such as transgender adolescents as well as pregnant adolescents may need additional types of care. Second, evidence-based multilevel strategies are needed to support adolescent-responsive services. For example, many of the projects reviewed in this study are implementing peer navigation and education support but these strategies may not address barriers faced at multiple levels of the socioecological model. Systematic implementation science research is required to identify which strategies and features of each strategy work best for targeted adolescent cohorts. Additionally, as outlined in Fig. 2, standardized implementation outcomes such as those related to acceptability and appropriateness should be collected across projects to optimize the delivery of adolescent-responsive components. Third, to support comparison across projects offering integrated services, we need outcome measures beyond the assessment of impact along the HIV continuum. Outcome measures and metrics that currently exist for HIV [51] should be expanded to capture services that impact other important domains such as sexual and reproductive health and mental health. Fourth, cost-effectiveness assessments should be incorporated as a key research component in all projects offering integrated services to adolescents so policy makers can identify the most efficient use of available resources.

Conclusion

Despite resource constraints and capacity challenges, countries with populations disproportionately impacted by HIV are attempting to implement programs to improve delivery of adolescent health care services. By adopting a life course perspective and recognizing that adolescent-focused care is a vital link between pediatric and adult health services, governments can adopt tailored strategies to ensure adolescents use available services with support from their caregivers. The conceptual framework and action steps outlined in this manuscript can serve as an important catalyst to design, implement, and optimize adolescent-responsive services for those living with and at risk of HIV infection.

Funding

The RTI international and Population Council team members were supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development grant number UH3 HD096908 (Sujha Subramanian, Principal Investigator).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Adolescent health and development: Q&A. 2020. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/news/q-a-detail/adolescent-health-and-development accessed 19 Oct 2020

- 2.World Health Orgnization Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Global consultation on lessons from sexual and reproductive health programming to catalyse HIV prevention for adolescent girls and young women. Brocher Foundation, Hermance; 27–29 April 2016; Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.

- 3.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global epidemic update: Communities at the centre: UNAIDS; 2019.

- 4.Karim S, Baxter C. HIV incidence rates in adolescent girls and young women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(11):e1470–e1471. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson EC, Jalil EM, Moreira RI, et al. High risk and low HIV prevention behaviours in a new generation of young trans women in Brazil. AIDS Care. 2021;33(8):997–1001. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2020.1844859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Republic of Zambia, Ministry of Health . Adolescent health strategy: 2017 to 2021. Lusaka: Republic of Zambia, Ministry of Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subramanian S, Edwards P, Roberts S, Musheke M, Mbizvo M. Integrated care delivery for HIV prevention and treatment in adolescent girls and young women in Zambia: protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(10):e15314. doi: 10.2196/15314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson EC, Garofalo R, Harris RD, et al. Transgender female youth and sex work: HIV risk and a comparison of life factors related to engagement in sex work. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):902–913. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9508-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Making health services adolescent friendly. 2012. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75217/9789241503594_eng.pdf;sequence=1#:~:text=Making%20health%20services%20adolescent%20friendly%20sets%20out,being%2C%20including%20sexual%20and%20reproductive%20health%20services.

- 10.USAID. DREAMS: Partnership to reduce HIV/AIDS in adolescent girls and young women. Washington, DC: USAID. https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-areas/hiv-and-aids/technical-areas/dreams.

- 11.Edwards PV, Roberts ST, Chelwa N, et al. Perspectives of adolescent girls and young women on optimizing youth-friendly HIV and sexual and reproductive health care in Zambia. Front Glob Women's Health. 2021;2:723620. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2021.723620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sevelius JM, Deutsch MB, Grant R. The future of PrEP among transgender women: the critical role of gender affirmation in research and clinical practices. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(7):21105. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sevelius JM, Keatley J, Calma N. 'I am not a man': trans-specific barriers and facilitators to PrEP acceptability among transgender women. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(7–8):1060–1075. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1154085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The World Bank. Data for low income, middle income, high income, upper middle income, lower middle income. 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=XM-XP-XD-XT-XN.

- 15.The World Bank. GDP per Capita (current US$). 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD.

- 16.HIV prevalence and HIV incidence for ages 15–24, 2020. https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/

- 17.Ministry of Health, Zambia. Zambia consolidated guidelines for treatment and prevention of HIV infection. 2020. https://www.moh.gov.zm/wp-content/uploads/filebase/Zambia-Consolidated-Guidelines-for-Treatment-and-Prevention-of-HIV-Infection-2020.pdf.

- 18.Ministry of Health, National AIDS and STI Control Programme. Guidelines on use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health [Kenya], NASCOP; 2018. http://cquin.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ICAP_CQUIN_Kenya-ARV-Guidelines-2018-Final_20thAug2018.pdf.

- 19.National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA), Nigeria. National HIV strategy for adolescents and young people 2016–2020. Abuja, Nigeria: NACA; 2017. https://naca.gov.ng/national-hiv-strategy-adolescents-young-people/.

- 20.Ministry of Health, Uganda. Consolidated guidelines for prevention and treatment of HIV and AIDS in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Health, Uganda; 2020. https://differentiatedservicedelivery.org/Portals/0/adam/Content/HvpzRP5yUUSdpCe2m0KMdQ/File/Uganda_Consolidated%20HIV%20and%20AIDS%20Guidelines%202020%20June%2030th.pdf.

- 21.Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Manejo da Infecção pelo HIV em Crianças e Adolescentes http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2017/protocolo-clinico-e-diretrizes-terapeuticas-para-manejo-da-infeccao-pelo-hiv-em-criancas-e

- 22.Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children, NACP. National guidelines for the management of HIV and AIDS, 7th Edition. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: MOHCDGEC, NACP; 2019. https://differentiatedservicedelivery.org/Portals/0/adam/Content/NqQGryocrU2RTj58iR37uA/File/NATIONAL_GUIDELINES_FOR_THE_MANAGEMENT_OF_HIV_AND_AIDS_2019.pdf.

- 23.South African National Department of Health. National guidelines for the management of HIV of adults, adolescents, children and infants and prevention of mother-to-child transmission; 2020. www.knowledgehub.org.za/system/files/elibdownloads/2020-07/National%20Consolidated%20Guidelines%2030062020%20signed%20PRINT%20v7.pdf

- 24.Ministry of Health, Zambia. Adolescent Health Strategic Plan 2011 to 2015. Lusaka, Zambia: Ministry of Health, Zambia; 2012. https://bettercarenetwork.org/sites/default/files/Zambia%20-%20Adolescent%20Health%20Strategic%20Plan%202011-2015.pdf.

- 25.Ministry of Health, National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP),. Adolescent’s package of care in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health [Kenya], NASCOP; 2014. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a29b53af9a61e9d04a1cb10/t/5bedc983352f53c1f4dcd722/1542310282943/HCW+Training+-+Guideline_Adolescent+package+of+care+in+Kenya.pdf.

- 26.Ministry of Health, Nigeria, with support from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Nigeria national standards & minimum service package for adolescent & youth-friendly health services. Ministry of Health, Nigeria; 2018. https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Nigeria-National-Standards-Minimum-Service-Package-for-Adolescent-Youth-Friendly-Health-Services-2018.pdf.

- 27.Ministry of Health. Adolescent health policy guidelines and service standards, Third Edition. Kampala, Uganda: The Reproductive Health Division, Department of Community Health, Ministry of Health; 2012. https://library.health.go.ug/sites/default/files/resources/Adolescent%20Health%20Policy%20and%20Service%20Standards%20-%20May%20%202012.pdf.

- 28.Proteger e cuidar da saúde de adolescentes na atenção básica Available at: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/proteger_cuidar_adolescentes_atencao_basica_2ed.pdf

- 29.Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. National adolescent health and development strategy 2018–2022. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: MOHCDGEC; 2018. https://tciurbanhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/020518_Adolescent-and-Development-Strategy-Tanzania_vF.pdf.

- 30.South African National Department of Health. National adolescent and youth health policy; 2017. https://www.datocms-assets.com/7245/1574921711-national-adolescent-and-youth-health-policy-2017.pdf

- 31.Ministry of Health, Kenya. National guidelines for provision of adolescent and youth friendly services in Kenya, Second Edition. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health, Kenya; 2016. https://faces.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra4711/f/YouthGuidelines2016.pdf.

- 32.Diretrizes Nacionais para a Atenção Integral à Saúde de Adolescentes e Jovens na Promoção, Proteção e Recuperação da Saúde https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/diretrizes_nacionais_atencao_saude_adolescentes_jovens_promocao_saude.pdf

- 33.Recomendações para a Atenção Integral a Adolescentes e Jovens Vivendo com HIV/Aids. 2013 http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2013/recomendacoes-para-atencao-integral-adolescentes-e-jovens-vivendo-com-hivaids-2013

- 34.Ministry of Education and Culture. Guidelines for implementing HIV/AIDS? STDs and life skills education in schools and teachers’ colleges, version 2. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Ministry of Education and Culture; 2002. https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Guidelines-for-Implementing-HIV-AIDS-STDs-and-Life-Skills-Education-in-Schools-and-Teachers-Colleges-Version-2-2002.Tanzania.pdf.

- 35.The United Repubic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. National guideline for comprehensive package of HIV interventions for key and vulnerable populations, Second Edition. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children, NACP; 2017. https://hivpreventioncoalition.unaids.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Tanzania-KP-GUIDELINE-1.pdf.

- 36.South African Department of Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities. National youth policy 2020–2030; http://www.women.gov.za/images/articles/NYPDraft-2030-28-July-2020.pdf

- 37.Operation Triple Zero Promotes Positive Action for Youth Living with HIV. 2021. https://www.jhpiego.org/story/operation-triple-zero-promotes-positive-action-for-youth-living-withhiv

- 38.Zvandiri Program. 2007. https://www.africaid-zvandiri.org/programmes-1

- 39.Peer to Peer support brings positive outcomes among adolescents in Northern Uganda. 2022. https://www.unicef.org/uganda/stories/peer-peer-support-brings-positive-outcomes-among-adolescents-northern-uganda

- 40.Grenier L, Suhowatsky S, Kabue MM, Noguchi LM, Mohan D, Karnad SR, Onguti B, Omanga E, Gichangi A, Wambua J, Waka C, Oyetunji J, Smith JM. Impact of group antenatal care (G-ANC) versus individual antenatal care (ANC) on quality of care, ANC attendance and facility-based delivery: A pragmatic cluster-randomized controlled trial in Kenya and Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10):e0222177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dow DE, O'Donnell KE, Mkumba L, Gallis JA, Turner EL, Boshe J, Shayo AM, Cunningham CK, Mmbaga BT. Sauti ya Vijana (SYV; the voice of youth): longitudinal outcomes of an individually randomized group treatment pilot trial for young people living with HIV in Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(6):2015–2025. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03550-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson EC, Jalil EM, Jalil CM, et al. Results from a peer-based digital systems navigation intervention to increase HIV prevention and care behaviors of young trans women in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Glob Health Reports. 2021;5:e2021077. doi: 10.29392/001c.28347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beyond Zero. 2021 https://beyondzero.org.za/

- 44.Donenberg GR, Atujuna M, Merrill KG, Emerson E, Ndwayana S, Blachman-Demner D, Bekker LG. An individually randomized controlled trial of a mother-daughter HIV/STI prevention program for adolescent girls and young women in South Africa: IMARA-SA study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1708. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11727-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization. Everybody’s business : Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHO's framework for action. 2007. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf?ua=1.

- 46.Folayan MO, Sam-Agudu NA, Adeniyi A, Oziegbe E, Chukwumah NM, Mapayi B. A proposed one-stop-shop approach for the delivery of integrated oral, mental, sexual and reproductive healthcare to adolescents in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;21(37):172. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.172.22824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ariel Adherence Clubs: Increasing Retention in Care and Adherence to Life-Saving Antiretroviral Therapy among Children and Adolescents Living with HIV in Tanzania—PEPFAR Solutions Platform. 2018. https://www.pepfarsolutions.org/solutions/2018/1/13/ariel-adherence-clubs-increase-retention-and-adherence-among-children-and-adolescents-living-with-hiv-in-tanzania-fzwjc

- 48.Adolescent-Friendly Health Sevices for Adolescents Living with HIV: From Theory to Practice. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329993/WHO-CDS-HIV-19.39-eng.pdf

- 49.van Staden Q, Laurenzi CA, Toska E. Two years after lockdown: reviewing the effects of COVID-19 on health services and support for adolescents living with HIV in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2022;25(4):e25904. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aarons GA, Reeder K, Sam-Agudu NA, Vorkoper S, Sturke R. Implementation determinants and mechanisms for the prevention and treatment of adolescent HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: concept mapping of the NIH Fogarty International Center Adolescent HIV Implementation Science Alliance (AHISA) initiative. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00156-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCumber M, Cain D, LeGrand S, et al. Adolescent medicine trials network for HIV/AIDS interventions data harmonization: rationale and development of guidelines. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7(12):e11207. doi: 10.2196/11207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]