Abstract

The 2020–2021 academic year brought numerous challenges to teachers across the country as they worked to educate students amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. The current study is a secondary data analysis of qualitative responses collected as part of a teacher survey to evaluate a social emotional learning curriculum implemented during the 2020–2021 academic year. The lived experiences of teachers (N = 52) across 11 elementary schools in the Great Plains region were captured through open-ended questions as the teachers transitioned from in-person to remote learning. A phenomenological approach was utilized to analyze the challenges expressed by teachers as they faced instability and additional professional demands. Given that stress and other factors that strain mental health exist within multiple layers of an individual's social ecology, a modified social-ecological framework was used to organize the results and themes. Findings suggest that during the academic year, teachers experienced stressors related to their personal and professional roles, concerns for students’ well-being which extended beyond academics, and frustrations with administration and other institutional entities around COVID safety measures. Without adequate support and inclusion of teacher perspectives, job-related stress may lead to teacher shortages, deterioration of teacher mental health, and ultimately worse outcomes for students. Implications for policy, research, and practice are discussed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12310-022-09533-2.

Keywords: Teacher mental health, Qualitative analysis, COVID-19

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic created new challenges and stressors for educators and highlighted existing pressure points and inequities within the education system (Cipriano et al., 2020). Prior to the pandemic, surveys found teaching to be one of the most stressful careers in the USA (Gallup Education, 2014), especially given that teachers are compensated significantly less than occupations with similar education requirements (Allegretto & Mishel, 2019). Teachers are expected to provide academic instruction, social-emotional support, and build relationships with students and families, often without adequate compensation or support from administration and leadership, which can lead to stress, frustration, burnout, and ultimately teacher turnover (Stauffer & Mason, 2013). In 2017, 61% of teachers reported experiencing job-related stress (American Federation of Teacher and Badass Teachers Association, 2017). Stressors commonly cited by teachers (pre-pandemic) include a lack of control and agency concerning classroom decisions and curricula, challenges with managing student behavior, lack of respect for the profession, and insufficient support and resources (Kyriacou, 2001; Richards, 2012). At the start of the pandemic, many teachers retained these same stressors, with added fears surrounding physical health, safety, and well-being (Will, 2021).

In addition to these fears and existing stressors, COVID-19 caused widespread closure of K-12 schools in districts across the USA, affecting 56.4 million students (Schwalbach, 2021). Each school district reacted differently to the pandemic based on location, politics, severity of infection and hospitalization rates, infrastructure, financial resources, socioeconomics, and community needs. These changes came with an increase in remote (i.e., online instruction) and hybrid learning (i.e., a combination of online and in person instruction), creating dramatic changes to the professional demands of teaching. Though remote learning is not new, many educators struggled with balancing the mental health and academic needs of their students in an online environment (Minkos & Gelbar, 2021). Prior to the pandemic, only 3.4% of primary schools offered completely online classes, a much lower rate than any other age group (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019), yet in spring of 2021, 43% of elementary school students were learning remotely, demonstrating a dramatic shift in the number of elementary students attending school virtually (Kamenetz, 2021). Remote learning was particularly challenging in elementary schools for various reasons—some children lacked sufficient internet or computer access and struggled with video chat fatigue (Fauzi & Khusuma, 2020). By the end of the 2020–2021 school year, elementary school students were, on average, five months behind in math and four months behind in reading (Dorn et al., 2020a). This is partly due to the countless challenges that teachers faced in quickly adapting their classes to online or hybrid environments. A large majority of teachers, particularly those in rural and poverty-stricken areas, struggled with the transition due to limited technology support and training, unexpected and rapid changes, and insufficient bandwidth (Goldberg, 2021). Despite teaching challenges, there was a strong focus on student outcomes during COVID-19 and teachers held the burden of implementing new programs and maintaining day to day order in the face of chaos and disruption. Consequently, there has been an increase in teacher anxiety, stress, and turnover (Steiner & Woo, 2021).

COVID-19 and Stress

As schools shifted to remote or hybrid instruction, discourse surrounding “learning loss” grew rapidly (Dorn et al., 2020a; Engzell et al., 2021; Kuhfeld & Tarasawa, 2020). Though school closures and protocols, such as mask mandates, social distancing, and remote learning, were necessary to curb the spread of the virus, these policies made it more difficult to deliver content and foster relationships in classrooms and schools. For some, remote instruction posed major challenges: In a survey of 1,000 teachers, 25% noted a lack of reliable high-speed internet at home and 40% stated they were unable to deliver remote instruction well (Diliberti et al., 2021). Though these significant challenges continued, grading and testing were reinstated in most schools during the 2020–2021 school year, raising expectations for student achievement and creating extra benchmarks for teachers (Dorn et al., 2020a).

The additional stress of delivering academic content in the pandemic context may negatively impact teachers’ physical and mental health (Guglielmi & Tatrow, 1998; Katz et al., 2016), which has implications for the classroom environment, student outcomes, and teacher turnover (Arens & Morin, 2016). Stressed-out teachers are more likely to have stressed-out students (Schonert-Reichl, 2017). Most teachers who quit during the pandemic cited stress as the driving factor in their decision, followed by a dislike for the way things were run at their school (Diliberti et al., 2021). Additionally, a large-scale teacher survey conducted by the RAND Corporation found that one in four teachers reported they were likely to leave the profession by the end of the 2020–2021 school year, with Black and African American teachers being especially likely to leave (Steiner & Woo, 2021). In addition, the pandemic has been a traumatic event for teachers and students alike, and there is an abundance of evidence that trauma increases the likelihood of negative mental and physical health outcomes (Felitti et al., 1998; Subica et al., 2012). Additionally, teachers who work with students who have experienced trauma often feel unprepared to meet the various needs of their students and as such report experiencing difficulties related to the emotional burden of their work including vicarious trauma (Alisic, 2012). Without adequate support, job-related stress and experiences of vicarious trauma may lead to teacher shortages, compromised teacher mental health, and ultimately worse outcomes for students. Though numerous studies have examined teacher feelings and stress during Covid-19 (e.g., Baker et al., 2021; Diliberti et al., 2021; Steiner & Woo, 2021), we are unaware of any studies that qualitatively examine the ramifications of transitioning from in-person to remote learning as teachers implemented a social emotional learning curriculum. A deeper understanding of teaching-related stress during COVID-19 can help administrators, policymakers, and relevant stakeholders plan additional support for educators, especially as the future of the pandemic remains unknown.

Theoretical Framework

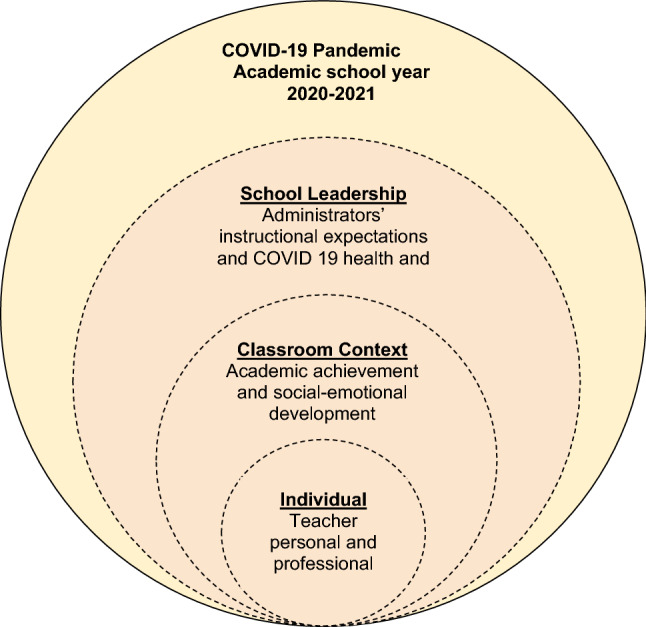

Though job-related stress is significant (Gallup Education, 2014), teachers do not exist in isolation, rather they are impacted by interconnected stressors that exist in their personal lives, their students' lives, and the broader context of society. Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) classic ecological theory states that humans develop within their changing immediate environments, nested within larger social contexts. This framework has been adapted and broadly applied throughout the literature on human development. The current study utilizes this framework to organize and contextualize the stressors teachers experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the multi-level nature of stressors within teachers’ experiences, an adapted socio-ecological framework is utilized to represent individual, classroom context and school leadership ecologies within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Fig. 1). Historical contexts such as the pandemic are expected to impact all levels of the social ecology, and these levels often overlap and interact with each other, hence blurring boundaries.

Fig. 1.

Socio-ecological model

Sources of stress experienced by teachers are unique to the individual and differ based on the teacher’s circumstances, temperament, ability to cope, and their personal strengths and weaknesses (Kyriacou, 2001). For instance, a survey of teachers who quit at the end of the 2021 school year found that younger teachers were more likely to leave the profession because of concerns related to childcare responsibilities, while older teachers were more likely to cite health risks as their top concern (Diliberti et al., 2021). Inherently, stress can emerge during the pandemic as teachers have to also manage relationships with students, families, teachers, and school leadership. A study on burnout during the pandemic included 359 teachers in K-12 and found that the majority reported significant anxiety from teaching demands, managing parent communication, and lack of administrative support (Pressley, 2021). In addition to teaching and following safety protocols during the pandemic, teachers also managed external stressors related to their personal lives which may have been unique to their individual, classroom context and school leadership circumstances. However, this study was conducted with a sample of primarily White and female teachers, and thus it is important to note that it is limited in its examination of how similar stressors may impact teachers of color and the impact of systemic inequalities on their social ecologies (Baker et al., 2021).

Current Study

Understanding stress and the mental health consequences for teachers under pandemic conditions is an immediate research priority (Holmes et al., 2020). As elementary school teachers were exposed to unprecedented levels of stress and increased professional demands, the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to have long lasting consequences on students, educators, and the entire US education system. The current study examined the lived experiences of elementary school teachers during the pandemic as they shifted between in-person, hybrid, and remote learning while navigating changes in professional demands because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of an open-ended prompt in an online survey to evaluate a social emotional learning (SEL) curriculum implemented during the 2020–2021 academic year allowed educators to express important aspects of their COVID-19 experiences. Adopting a socio-ecological theoretical framework and a phenomenological analytic approach, we explored our research question: How does stress associated with the pandemic impact teachers’ mental health, their ability to meet professional demands, and ultimately student outcomes?

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The current study used data collected from third–fifth-grade teachers across 11 elementary schools in the Great Plains region of the USA. Baseline data (N = 52) were collected during the fall of 2020 (T1), and post-test data (T2; N = 42) were collected during the spring of 2021 in collaboration with the public school district and the Sources of Strength program (LoMurray, 2005). Table 1 presents demographic information for the teachers who participated in the survey during the baseline and post-test data collection. Teachers were predominantly female (T1: 80.8%, T2: 83.3%), White, or European American (T1 & T2: 100%) and were evenly divided across third, fourth, and fifth grades. Students in their classrooms were also predominantly White (77.1%), with a smaller percentage of Black (8.8%), Native American or Alaska Native (6.5%), and Hispanic (5.7%) students.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Time 1 (N = 52) | Time 2 (N = 42) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| 18 to 24 | 5 (9.6%) | 2 (4.8%) |

| 25 to 34 | 14 (26.9%) | 16 (38.1%) |

| 35 to 44 | 12 (23.1%) | 11 (26.2%) |

| 45 to 54 | 13 (25.0%) | 7 (16.7%) |

| 55 to 64 | 8 (15.4%) | 6 (14.3%) |

| 65 to 74 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 75 or older | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 42 (80.8%) | 35 (83.3%) |

| Male | 10 (19.2%) | 7 (16.7%) |

| Grade | ||

| 3rd grade | 21 (40.4%) | 14 (33.3%) |

| 4th grade | 17 (32.7%) | 12 (28.6%) |

| 5th grade | 14 (26.9%) | 12 (28.6%) |

| Blended grades | 0 (0%) | 4 (9.5%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White or European American | 52 (100%) | 42 (100%) |

| Black or African American | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Asian American | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 1 (1.9%) | 2 (4.8%) |

| Hawaiian Native or Pacific Islander | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other race | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Teachers could select more than one race/ethnicity

All data were de-identified and provided by Sources of Strength. The school district distributed the survey link using an anonymous Survey Monkey link via email. The institutional IRB of the lead authors approved this protocol as exempt for secondary analysis. The current study is a secondary data analysis of teacher qualitative responses in a survey conducted by their school district as part of the evaluation of the Sources of Strength elementary school curriculum. Thus, responses specifically discussing the experiences of teachers and students during the pandemic were not the primary focus of data collection. Sources of Strength is a social emotional learning (SEL) program that utilizes a strengths-based lens to encourage help seeking and healthy coping skills. The teacher self-report survey at both time points included largely quantitative measures (e.g., Likert scale items) to capture student and teacher social emotional skills and wellbeing before and after implementing the program. The survey also included the open-ended prompt “please provide examples and comments” after each subscale for teachers to describe their experiences qualitatively. Teacher examples and comments provided on the survey across both time points were analyzed (see supplemental Table 1).

School District Context

Due to the variability in instruction as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to understand the context of the schools in this study. According to publicly available data from the district website and contextual information provided by the district, remote instruction began in March of 2020 and continued until May 2020. In April 2020, weeks were shortened to four days with Friday being a “flex” day where students could make-up assignments and parents could contact teachers. Throughout the pandemic, the district worked to implement safety, sanitation, and social distancing policies, including regularly disinfecting surfaces, requiring masks and a mandatory quarantine period for those exposed to COVID-19 or traveling internationally. In July 2020, parents were given the option to have their child return to school or continue remote learning. In August 2020, only 610 elementary students (8%) in the district were learning remotely and the majority returned in-person. At the time of survey administration (T1) in October 2020, the district alerted parents that they were heading into the severe risk category and would be monitoring the situation in the school and community closely. Remote learning began again in November 2020 with a plan to return in-person in January. Between October and November 2020, the student and staff COVID-19 percentage rate ranged from 1.4 to 3.3%. In January 2021, school began again with an option for in-person or remote learning. During the 2020–2021 school year, a teacher at a participating school died from COVID-19. The district has remained in-person since, including during survey administration in March 2021 (T2), when the student and staff infection rate was 0.2%. The district planned to return in-person with masks optional but recommended for the upcoming school year in August 2021.

Analytic Approach

The current study utilizes a phenomenological qualitative research approach to examine the lived experiences of teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Groenewald, 2004). Phenomenological research has been defined as “research that seeks to describe the essence of a phenomenon by exploring it from the perspective of those who have experienced it” (Neubauer et al., 2019, p.91). By including an open-ended prompt on the survey for teachers to express their experiences implementing the SEL program during the COVID-19 pandemic, we gained a better understanding of how the pandemic impacted education and the health and well-being of teachers and their students. The goal of the present study is to understand how teachers' experiences of stress during the pandemic affected their personal and professional lives. Therefore, we choose to identify the essential themes by immersing ourselves in the teacher's perspectives without assigning any prior interpretations to the data. In this step, researchers employed the technique of bracketing, putting aside personal ideas and beliefs to have an open mind to participant experiences (Eddles-Hirsch, 2015). Only after this step, we used the social-ecological theoretical framework to organize and discuss our findings in relation to the broader systems where these experiences occur while noting the blurring of boundaries.

Research Team Positionality

Our research team consisted of the laboratory director, the laboratory coordinator, three graduate research assistants in the fields of education and school psychology, and two undergraduate research assistants in the field of education and psychology. Two members of our research team had experiences working as school psychology interns in schools during the 2020–2021 academic year. One of the graduate research assistants was a full-time teacher in elementary schools prior to the pandemic which provided an insider perspective on the methodological approach and subsequent analysis. All members of the team had experience conducting school-based research and were familiar with analyzing qualitative research, the Sources of Strength program, the broader literature on teacher mental health and the theoretical orientation of this study. Although our research team did not directly interact with participants, our positionality allowed us to conduct an informed analysis of teachers' thoughts and experiences.

The secondary qualitative analysis of open-ended responses from the teacher surveys began following post-test data collection, starting in May of 2021, and ending in August of 2021. In the first round of analysis, every member of the team engaged in analytic induction and abduction as we read the full transcripts of teacher responses to the open-ended prompts listed in Supplemental Table 1. During this process, the team wrote memos on their first impressions and noted meaningful themes emerging from the data (Saldaña & Omasta, 2021). Weekly meetings with all team members were held to engage in analytic deduction as we compared and discussed our individual memos. We grouped the emerging codes according to the categories of the social ecological framework and condensed codes with similar meaning across our individual memos to develop a codebook. All available transcripts from T1 and T2 were reviewed and coded simultaneously because we were interested in the emerging themes from teachers shared across both time points to capture their lived experiences during the 2020–2021 academic year. The codebook was then used to conduct a second round of individual analysis where each team member assigned one or more codes to each open-ended response independently. Following independent coding, our team met again as a group to establish intercoder agreement and resolve any conflicts that arose during coding (Saldaña & Omasta, 2021). This process resulted in a final set of codes for every open-ended response in the transcripts. Additionally, we examined as a group whether there were distinctions in the codes assigned at T1 and T2 and noted any salient differences in the comments. Lastly, two coders met to discuss the final set of codes, deliberate, and select the most salient examples that are presented in the findings section of the paper.

Findings

To understand the multifaceted layers of stressors teachers encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic, findings are organized using a modified socio-ecological framework and then divided into relevant themes. Figure 1 represents the different levels examined within the context of the pandemic during the 2020–2021 academic school year and the dotted lines represent the blurred distinction between each level. Qualitative data from survey responses are copied directly from the survey and have not been altered. Quotes from participants are followed by their randomized IDs to distinguish different teacher perspectives and when they were captured (T1-October 2020; T2-March 2021). There were no salient differences found between the two time points, and the research questions were aimed at capturing the entire academic year, and thus they are presented together. Although challenging to detangle given the blurring of boundaries within teachers’ social ecology during the pandemic, data on the disruptions and instability from the 2020–2021 academic school year were best organized at the individual, classroom context, and school leadership level. During the 2020–2021 academic year, teachers expressed a variety of additional stressors within multiple levels of their social ecology because of the pandemic.

Individual Level

Individual-level stressors were conceptualized as any stressor that teachers experienced in their professional and personal lives. At the individual level, teachers mentioned personal experiences with anxiety, the impact of professional demands, and work responsibilities as stressors during the academic year.

Personal and Professional Experiences

When teachers were asked about work anxiety, most acknowledged the existing professional demands and responsibilities as a contributor. One teacher said:

Teaching and stress have been hand-in-hand for many years. Because things are constantly changing in education and expectations are constantly rising it is stressful. I think since teachers spend 7 hours a day with kids it just feels overwhelming at the end of the day to plan for the next day/week (0074, T2).

Similarly, another teacher said:

When trying to do my best to meet the needs of all of my students in a 4th/5th combination classroom, it is a lot of work. Many early morning and late evenings are spent at school to be sure that I am ready for my students each day (0054, T2).

Another teacher mentioned an overwhelming set of expectations for teachers with little support:

“It's a lot on our plates ALL of the time to juggle planning and being innovative is asking a lot. PLUS taking care of social and emotional needs without much support from parents” (0047, T1).

Besides the existing stressors of the teaching profession, one teacher summarized the burden of the pandemic:

The pandemic has placed added pressures on teachers. I am not only teaching the children face-to-face but must provide materials/lessons for any of my students who have had to quarantine. As a district we have had to pivot from face-to-face learning to online learning and back again (0076, T2).

It was common for teachers to mention overlapping stressors related to how their professional role impacts their personal lives, thus blurring the work-life balance boundaries. One teacher shared “Thinking about school has provided quite a bit of stress in my personal life. The needs of my students, changes due to the pandemic, how to support all the various needs, etc.” (0029, T1). Another teacher mentioned how her work impacts her ability to rest after work: “I have nights where I can't sleep thinking about school related activities” (0045, T1).

In addition to professional stressors, some teachers also expressed personal experiences with anxiety. One teacher offered this comment: “I suffer from anxiety and sometimes my anxiety can cause panic attacks. My anxiety happens most when I am being evaluated/observed or when I am overstressed and or sleep-deprived” (0077, T1). A few teachers who mentioned having anxiety also mentioned using medication to treat their mental health. However, it is unknown if these teachers were already on medication prior to the pandemic or if medication began because of pandemic-related stress. One teacher said: “I am on anxiety medication. If I forget it I feel more anxious about school, but when I am on it I am not very anxious” (0011, T1). The same teacher expressed utilizing other coping strategies after exposure to the Sources of Strength curriculum in addition to medication for their mental health challenges: “I do have anxiety, but I am on medications and use some of the tips and tricks talked about in our sources of strength lessons, as well as calm classroom, to help control the anxiety before it affects my job” (0011, T2).

Although teachers have multiple roles and responsibilities outside of school as it pertains to their family and friends, this was not a common theme. However, one teacher did acknowledge the intersection of stress from their personal life interfering with their ability to manage stress at school and the transition to remote learning:

Extenuating circumstances will cause anxiety that I usually don't feel. For example when my husband passed away, I was not able to focus on school for a few months. When we went remote, I couldn't sleep or take time for myself- I became unbalanced (0071, T1).

At the individual level, teachers mainly highlighted their experiences with stress during the pandemic as it related to the professional demands and expectations of their role as well as their personal experiences with anxiety.

Classroom Context Level

Classroom context-level stressors were conceptualized as any stressor that was a result of direct teacher relationships or interactions with students. At the classroom context level, teachers mentioned their relationships with their students as a stressor and expressed concerns given the educational instability and changing professional demands experienced during the 2020–2021 academic year. Specifically, teachers shared concerns around their students’ academic achievement, social and emotional well-being, home life, and disruptive behaviors.

Academic Achievement

Many of these themes overlapped, as concerns for students attending school remotely were often interconnected with academic disparities experienced by students having challenges with this mode of instruction. One teacher expressed needing to work more as a result and said:

Distance learning did not work very well for some students. These students didn't show up for our scheduled Zoom meetings, and they did very little work. This has put some students behind. I have been working hard to get them caught up (0054, T2).

In addition, existing academic gaps appeared to have widened for one teacher’s students. This teacher stated:

When we pivoted to distance learning to slow the curve it was very difficult for some of my students who already struggle with reading and math. Without adult support beside them to keep them on task and learning they have fallen behind their peers (0076, T2).

One teacher acknowledged the many unknowns of teaching during the 2020–2021 academic year and expressed worry that despite their best efforts they may not be able to catch students up:

Teaching during a pandemic is something no one saw coming. It is stress, it is new. No one has the right answer as we are all learning how to do this. I worry that my students are playing major catch up and in their learning and I worry that I won’t teach them enough to get caught up (0060, T1).

Another teacher summarized the intersecting nature of academics and student well-being, as the pandemic has impacted multiple aspects of their student’s lives:

The large majority of my class is doing well academically, socially, emotionally, and behaviorally right now. They are excelling. However, there are a few students in my class that struggle for different reasons. I have one student struggling soci-emotionally because parents are going through a divorce, distance learning was a nightmare for her and she has a lot of stress on her plate. I have others that struggle with managing their behavior and emotions (0056, T2).

Social and Emotional Development

The concerns of teachers go beyond academics, as they are aware that student’s social and emotional well-being has also been affected by the pandemic. One teacher said, “Due to the pandemic, lack of parenting, lack of home support, too much screen time, etc.… many students are struggling with staying on task, anxiety, appropriate social interactions, self-worth, confidence, safety…” (0033, T2).

The concerns with social and emotional well-being overlapped with concerns around disruptive behaviors and how students may be perceived, which may exacerbate existing social and emotional skill deficits. One teacher commented: “I have some students who have been acting out lately and I am concerned about how adults are perceiving them and how their friends might be pulling away” (0011, T2). Teachers were asked about their students' social and emotional skills as well as disruptive behaviors in their classrooms. Given these questions, the bulk of the data were centered on teachers' concerns around emotional regulation and their students’ ability to control their behaviors. One teacher said: “This year, but I feel like we are having more and more disruptive behaviors in class each year. These disruptive students have limited resources and often stop learning in the classroom which is not fair to the other students who want to learn and feel safe!” (0072, T1).

It is important to note that our teachers work in elementary schools and developmentally their students are beginning to learn their social and emotional skills outside of the home. One teacher expressed a typical developmental process among girls as it relates to peer aggression in their class but noted a lack of parental involvement, which may impact their students’ mental health:

The girls in my classroom seem to go through phases of treating others nicely and being rude to others. I do see several of them as somewhat "fragile" and things happening outside of school that they don't tell their families which wears on their mental health (0057, T2).

Similarly, another teacher noted that specific students struggled with managing their emotions and behaving in ways that were disruptive to the class: “4 students constantly need reminders to show self-control, make better choices with body and voice (blurting, ignoring adult directions, back talking, shutting down when person doesn't get his way). 1 student in particular riles up a couple other kids” (0068, T1). Classroom behavior is learned in school and teachers often remind students of appropriate and inappropriate behavior.

Despite the challenges during the 2020–2021 academic year, teachers were also asked to reflect on prosocial student behaviors and resiliency. Several teachers expressed prosocial behaviors in their classrooms. One teacher expressed their role in cultivating prosocial behaviors: “This year especially, I've really focusing on building a strong classroom community. My students have been so good about being kind to one another and making everyone feel like they belong! "Our class is a family" is our motto” (0074, T2). Another teacher expressed prosocial behaviors towards a student in their class with a disability: “I have a student with special needs and many of my other students will make sure to include him in activities” (0011, T2). The Sources of Strength curriculum focuses on healthy coping skills and teacher responsibility in cultivating healthy coping and resilience. Related to the pandemic, one teacher mentioned validating student feelings and noticing resiliency in their class throughout the school year:

My students have proven to be so resilient throughout this crazy last year of a global pandemic. I'm impressed with how well they have adapted and how strong they are. That being said, I don't expect them to hide their feelings. If they are feeling sad, worried, upset or any other emotions I make sure to validate those feelings (0074, T2).

Teachers and students have faced numerous challenges in their pursuit of teaching and learning, but in the face of adversity teachers have also witnessed various strengths and points of resiliency among their students. One teacher mentioned receiving praise from an administrator for her students' behaviors: “My principal even commented during an observation at how resilient my class is this year and how well they can continue working when there is an outburst” (0056, T2). At the classroom context level, teacher stressors cannot be separated from their relationships with their students and their concerns for their education and well-being. The concerns teachers expressed are interconnected with their role as educators who help to shape the academic, social, and emotional skills of their students, and the 2020–2021 academic year proved to be challenging in numerous ways.

School Leadership Level

School leadership-level stressors were conceptualized as any stressor that was mentioned because of teacher interactions with school administrators, district, and government entities at the local, state, and federal level.

Administrators’ Instructional Expectations

At the school leadership level, teachers did not explicitly express support from the educational institutions (e.g., school, district) they are a part of. One teacher summarized these frustrations:

The expectations that the school system has as it relates to this unique year often feel unrealistic. It is frustrating to continually be asked to do new things and have more put on our plate when this year is very unique, and quite frankly, already enough work as it is (004, T1).

During the pandemic, educators and students were still expected to function and partake in standardized testing as if it were a traditional year. One teacher commented:

With the extra layer of COVID, there has been a lot expected of teachers and those in education in general. Testing and accreditations have still been pushed even in the midst of a pandemic school year and the protocols on top of it all (0062, T1).

Teachers were also frustrated with government entities, as the instability and variability in educational action plans were a result of different decisions made at the state and federal levels. One teacher said:

Teaching face to face during the Covid-19 pandemic is extremely stressful. It was stressful teaching remotely last spring too. I believe our nation and our state and our city lack leadership willing to put the health of our students/families and teachers/staff first (0032, T1).

COVID Health and Safety Protocols

COVID-19 safety measures made education challenging and concerns for safety and well-being were common, but they often overlapped with frustrations felt over how school administration handled in-person learning.

One teacher expressed how COVID-19 health measures felt impossible in the classroom:

Having so many students, especially during a pandemic where they cannot be adequately spaced, is very stressful. I feel like the administration is not doing an adequate job informing us or keeping us safe. There are also so many things they want us to teach and not enough time to teach it (0067, T1).

Another teacher questioned their own self-efficacy as the pandemic related safety “elements” interfered with their ability to be an effective teacher. “This school year is already stressful with the COVID elements, but there are expectations at our school that cause extra stress and make me feel like I can't do my job as well as I would like” (0042, T1). Furthermore, the teaching profession was significantly strained, as the stories of these teachers made it clear that it was difficult to not only teach but to also provide a safe space where students can develop socially. One teacher summarized this concern:

With everything going on, it is stressful to find a delicate balance between allowing for social interaction to maintain social skills and friendships for students while also protecting them and making sure you are doing whats best for their safety (005, T1).

The 2020–2021 academic year was a stressful year for educators and students. As we approach another uncertain school year, the stories around the stressful events at all levels of teachers' social ecology must not be forgotten. Rather there is much to learn from these lived experiences and the ways in which individual, classroom context and school leadership level stressors add or detract from teachers and their role.

Discussion

This study examined qualitative responses from elementary school teachers about stressors experienced while teaching and implementing an SEL curriculum during the 2020–2021 academic school year. While teachers are always under tremendous amounts of stress, conditions associated with the pandemic exacerbated these feelings, resulting in challenges in the classroom and broader community. An adapted socio-ecological framework considers how these experiences are shaped by the intersectional nature of individual, classroom context, and school leadership experiences, framed within the societal context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Individual

At the individual level, teachers frequently cited the heightened demands they faced while teaching during a pandemic. Increased workload associated with preparing for and facilitating online learning as well as supporting students with social-emotional concerns or issues associated with the pandemic caused the lines between home and work to become blurred. Many teachers may have experienced elevated levels of stress and anxiety associated with the pandemic; however, our findings indicated there was not any way to discern if the anxiety was evident prior to the pandemic or because of the pandemic. Outside of the current context, teaching is one of the most stressful professions contributing to high levels of burnout and turnover and negatively affecting school climates (Schonert-Reichl, 2017). During the pandemic, 84% of teachers say morale is lower than ever and one third of them report being more likely to leave the teaching profession or retire early (Rosenberg & Anderson, 2021). These feelings may have been exacerbated by the fact that most of the sample is female, and research shows that women often report difficulty carrying the heavy workload of both their personal and professional responsibilities leading to heightened stress (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021). Both the personal and professional stressors identified by participants align with the current state of literature on teaching in a pandemic which emphasizes high rates of teacher stress, depression, and burnout (Steiner & Woo, 2021). Addressing these concerns is key to not only individual well-being but protecting schools already in disarray from developing an overwhelmed and understaffed workforce.

Classroom Context

In addition to individual stressors, several classroom context concerns were also noted by teachers. Relationships between teachers and students are a key aspect of the educational experience, which shape student success (Ansari et al., 2020; Stauffer & Mason, 2013). In this time of uncertainty, educators felt high levels of concern for their students' academic achievement and well-being. Research shows that teachers working with younger students showed the highest levels of anxiety, perhaps due to a heightened sense of responsibility for addressing their student’s needs (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021). Additionally, there were existing educational inequities which have been exacerbated by the pandemic. Preliminary research shows that teachers in schools with lower resources are more concerned about their students' ability to access and engage in new learning modalities (Chen et al., 2021) and that Black, Latinx, and students experiencing poverty will likely experience the most significant harm because of the pandemic (Dorn et al., 2020b). Without immediate access to their students, many teachers worried that students in unstable homes, or those without the necessary support or safety provided by school, would fall behind. Teachers were particularly worried about students who were already struggling academically and felt additional stress ensuring that these students had the support they needed. In addition to academics, teachers were cognizant of the effect the pandemic had on social-emotional problems and skills such as anxiety, social interactions, and staying on task. One teacher also explicitly mentioned the impact of their students' home life on their experiences. Traumatic familial experiences such as divorce, loss, or financial issues, commonly experienced during the pandemic may intensify student stress resulting in behavioral issues and/or decreased performance (Cénat & Dalexis, 2020). Despite the numerous challenges associated with the pandemic, teachers reported significant resilience from students. While teachers were impressed with this, some commented on the importance of allowing students space to express their emotions and the need to be intentional about building a positive classroom climate and creating spaces where students feel safe and supported.

School Leadership

Finally, teachers experienced high levels of stress due to decisions made by leadership both at the school and community level. Teachers felt overburdened by the expectations of school leadership and governmental entities to constantly adopt new safety guidelines while expected to provide the same level of instruction. One teacher cited frustrations with standardized testing, which was still seen by the district as a priority, even amidst the pandemic. Concerns around physical and mental health and safety were also cited. Teachers expressed stressful situations when trying to keep students safe in classrooms that were not designed for social distancing, while also prioritizing student social development and well-being. Additionally, teachers reported feeling that school and state leadership did not consider the health and safety of their students or teachers when making decisions. Many of these concerns align closely with those of educators across the country, contributing to high levels of dissatisfaction, frustration, and burnout (Kim & Asbury, 2020; PBS, 2020). Lack of administrative support is one of the primary reasons for burnout and turnover among teachers and addressing these issues is key to sustaining a healthy teacher workforce (Talley, 2017). Particularly in a time where everyone is directly impacted, administrators need to support and include their teachers in the discussions around mode of instruction to understand what works best for their teachers, students, and families. Educators for Excellence (2021) surveyed educators nationwide and found that many were dissatisfied with the level of support and input they had from local and district administrators. Leadership must consider the needs and desires of teachers to protect not only their staff but also student learning, and thus it is imperative to elevate teacher perspectives. Moving forward, schools should strongly consider including teachers in decisions about reopening plans (remote vs. hybrid vs. in person), student safety, and curriculum to ensure that teacher perspectives are heard and represented in their schools' decision making.

Limitations

Due to the lack of research on teacher experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study provides valuable insight from teachers on job-related stress. Despite its contribution, there are limitations to consider when interpreting the results. First, data were collected from one school district in the Great Plains region of the USA from participants who were predominantly White and taught students who were also predominantly White. Because of this, findings may not generalize to other populations, specifically among teachers and students of color who may have experienced different stressors and/or navigated similar stressors differently during the pandemic (Baker et al., 2021). Secondly, despite the socioecological framework used in this paper, we were unable to consider the effects of outside school influences on teacher stress. Interpersonal relationships outside of the classroom, such as students and their families, were not represented in this data because questions about external stressors were not specifically asked. This is a weakness as these factors may have a significant impact on teacher stress in the classroom. Further, our classification of stressors in discrete categories of the socio-ecological model may be overly simplified, as these stressors are often interrelated and can cross multiple social-ecological domains. Finally, data for this paper were collected as part of a larger study on the implementation of a social emotional learning program, so responses specifically discussing the experiences of teachers and students during the pandemic were not the primary focus. Additionally, because this paper utilized secondary data rather than focus groups or interviews, we were unable to have teachers expand on their answers (provide more detail, explain whether an issue was caused or exacerbated by the pandemic, etc.) resulting in some interpretation on the part of the research team. The lack of feedback from teachers may have impacted our ability to detect any differences in the comments between T1 and T2, and therefore we suggest caution when interpreting these findings.

Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research

As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on, schools will continue to face various challenges. Stakeholders including school leaders, researchers, and policymakers must consider ways to address the issues highlighted here to mitigate harms to teachers and build better support for them.

Support for Teachers and Students

In addition to caring for students, schools are also responsible for supporting their staff and teacher workforce. As uncertainties around COVID-19 continue, leadership must prioritize physical health measures by encouraging appropriate masking and distancing guidelines as well as providing adequate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). In addition to physical health, it is imperative that teacher mental health is considered a priority to reduce stress and improve physical and psychological safety, minimizing teacher burnout and turnover. Schools must prioritize programming and resources for adults in the school building, such as mental health, sick leave and vacation days, flexibility on lesson planning and setting collaborative academic expectations as well as hiring additional teachers and mental health staff (Diliberti & Schwartz, 2021; Giannini et al., 2021). Furthermore, state and local school leadership should reconsider learning benchmarks and expectations surrounding testing considering the current climate to ensure that schools are serving students equitably (National Academy of Education, 2021). Teachers need the flexibility and resources to effectively address the needs of their students.

Schools have the potential to support the well-being of their students, teachers, and staff during and after the pandemic. First, schools can prepare for students who will be returning to school with additional trauma and may struggle socially, behaviorally, and academically (Cénat & Dalexis, 2020). Programming that is trauma-informed to support the school community in strengthening their academic, social, and emotional skills to build resilience and minimize the harm caused by the pandemic may be effective (Collin-Vezina et al., 2020; Taylor, 2021). Students may also need additional academic support to ensure that their learning needs are being met (e.g., tutoring, summer camp) (Kuhfeld et al., 2022; US Department of Education, 2021).

Research

There is a need for more research that is inclusive of educators and their experiences to inform education policy and practice. Specifically, more data are needed on the effects of the pandemic, including the impact on the mental health of other school staff, children, families, and other community members (Nawaz et al., 2020). Additional qualitative and quantitative research is needed to understand and address ways to support educators throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, to ensure that elementary school children are receiving the school-based academic, social, and emotional support they need (Song et al., 2020). Historically, research has failed to capture the experiences of marginalized students and teachers (Codding et al., 2020). It is imperative that future research center the experiences of students and teachers of color, and students and teachers with disabilities, as these populations were hit particularly hard by the pandemic and will likely face additional challenges in the coming years.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Robinson, Valido, Drescher, Woolweaver, Wright, and Dailey conducted analysis, and all authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Funding

The study did not receive any funding.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Availability of data and material

The qualitative data are available upon request.

Code availability

The qualitative codebook is available upon request.

Ethics approval

There were no ethical issues concerning human participants/animals in the study. Informed consent was not required for the study.

Consent to participate

N/A

Consent for publication

N/A

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alisic E. Teachers' perspectives on providing support to children after trauma: A qualitative study. School Psychology Quarterly. 2012;27(1):51. doi: 10.1037/a0028590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allegretto, S., & Mishel, L. (2019). The teacher weekly wage penalty hit 21.4 percent in 2018, a record high: Trends in the teacher wage and compensation penalties through 2018. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/teacher-pay-gap-2018/

- American Federation of Teachers and Badass Teachers Association. (2017). Educator Quality of Work Life Survey. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/ 2017_eqwl_survey_web.pdf

- Ansari A, Hofkens TL, Pianta RC. Teacher-student relationships across the first seven years of education and adolescent outcomes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2020;71:101200. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2020.101200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arens AK, Morin AJS. Relations between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and students’ educational outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2016;108(6):800–813. doi: 10.1037/edu0000105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CN, Peele H, Daniels M, Saybe M, Whalen K, Overstreet S, Collaborative T-I. The experience of COVID-19 and its impact on teachers' mental health, coping, and teaching. School Psychology Review. 2021;50(4):491–504. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2020.1855473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist. 1977;32:513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat JM, Dalexis RD. The complex trauma spectrum during the COVID-19 pandemic: A threat for children and adolescents’ physical and mental health. Psychiatry Research. 2020;293:113473. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LK, Dorn E, Sarakatsannis J, Wiesinger A. Teacher survey: Learning loss is global—and significant. Public & Social Sector Practice; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano, C., Rappolt-Schlichtmann, G., & Brackett, M. A. (2020). Supporting school community wellness with social and emotional learning (SEL) during and after a pandemic. Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center, Pennsylvania State University. https://www.conexionternura.com/media/documents/Supporting_School_Community_Wellness.pdf

- Codding RS, Collier-Meek M, Jimerson S, Klingbeil DA, Mayer MJ, Miller F. School psychology reflections on COVID-19, antiracism, and gender and racial disparities in publishing. School Psychology. 2020;35(4):227–232. doi: 10.1037/spq0000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin-Vézina D, Brend D, Beeman I. When it counts the most: Trauma-informed care and the COVID-19 global pandemic. Developmental Child Welfare. 2020;2(3):172–179. doi: 10.1177/2516103220942530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diliberti, M. K., Schwartz, H. L., & Grant, D. (2021). Stress topped the reasons why public school teachers quit, even before COVID-19. Research Report. RR-A1121–2. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1100/RRA1121-2/RAND_RRA1121-2.pdf

- Diliberti, M. K., & Schwartz, H. L. (2021). The K–12 Pandemic Budget and Staffing Crises Have Not Panned Out—Yet: Selected Findings from the Third American School District Panel Survey. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA956-3.html.

- Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., & Viruleg, E. (2020a). COVID-19 and learning loss—disparities grow and students need help. McKinsey & Company, December, 8.

- Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., & Viruleg, E. (2020b). COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime. McKinsey & Company, 1.

- Eddles-Hirsch K. Phenomenology and educational research. International Journal of Advanced Research. 2015;3(8):251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Educators for Excellence. (2021). Voices From The Classroom A Survey Of America’s Educators. https://e4e.org/sites/default/files/teacher_survey_2021_digital.pdf

- Engzell P, Frey A, Verhagen MD. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022376118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi I, Khusuma IHS. Teachers’ elementary school in online learning of COVID-19 pandemic conditions. Jurnal Iqra Kajian Ilmu Pendidikan. 2020;5(1):58–70. doi: 10.25217/ji.v5i1.914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup Education (2014). State of America’s schools: The path to winning again in education. http://products.gallup.com/168380/state-education-report-main-page.aspx

- Giannini, S., Jenkins, R., Saavedra, J. (2021, October 5). There will be no recovery without empowered, motivated and effective teachers. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/there-will-be-no-recovery-without-empowered-motivated-and-effective-teachers

- Goldberg SB. Education in a pandemic: The disparate impacts of COVID-19 on America’s students. Department of Education; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald T. A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2004;3(1):42–55. doi: 10.1177/160940690400300104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi RS, Tatrow K. Occupational stress, burnout, and health in teachers: A methodological and theoretical analysis. Review of Educational Research. 1998;68(1):61–99. doi: 10.3102/00346543068001061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Ballard C, Christensen H, Silver RC, Everall I, Ford T, Bullmore E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetz, A. (2021). New Data Highlight Disparities In Students Learning In Person. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/03/24/980592512/new-data-highlight-disparities-in-students-learning-in-person

- Katz DA, Greenberg MT, Jennings PA, Klein LC. Associations between the awakening responses of salivary α-amylase and cortisol with self-report indicators of health and wellbeing among educators. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2016;54:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim LE, Asbury K. ‘Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: The impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2020;90(4):1062–1083. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., Lewis, K., and Emily Morton, E. (2022, March 3). The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up? Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2022/03/03/the-pandemic-has-had-devastating-impacts-on-learning-what-will-it-take-to-help-students-catch-up/

- Kuhfeld, M., & Tarasawa, B. (2020). The COVID-19 slide: What summer learning loss can tell us about the potential impact of school closures on student academic achievement. Brief. NWEA. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED609141.pdf

- Kyriacou C. Teacher stress: Directions for future research. Educational Review. 2001;53(1):27–35. doi: 10.1080/00131910120033628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minkos ML, Gelbar NW. Considerations for educators in supporting student learning in the midst of COVID-19. Psychology in the Schools. 2021;58(2):416–426. doi: 10.1002/pits.22454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Education (2021). Educational Assessments in the COVID-19 Era and Beyond. https://naeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Educational-Assessments-in-the-COVID-19-Era-and-Beyond.pdf

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Distance Learning. Fast Facts. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=79

- Nawaz K, Saeed HA, Sajeel TA. Covid-19 and the State of Research from the Perspective of Psychology. International Journal of Business and Psychology. 2020;2:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education. 2019;8(2):90. doi: 10.1007/S40037-019-0509-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Berasategi Santxo N, Idoiaga Mondragon N, Dosil Santamaría M. The psychological state of teachers during the COVID-19 crisis: The challenge of returning to face-to-face teaching. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;11:3861. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.620718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PBS. (2020). “I’m scared” – 21 teachers on what it’s like teaching in a global pandemic. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/extra/2020/12/im-scared-21-teachers-on-what-its-like-teaching-in-a-global-pandemic/

- Pressley T. Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educational Researcher. 2021;50(5):325–327. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211004138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J. Teacher stress and coping strategies: A national snapshot. The Educational Forum. 2012;76(3):299–316. doi: 10.1080/00131725.2012.682837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, D., & Anderson, T. (2021). Teacher turnover before, during & after COVID. https://www.erstrategies.org/cms/files/4773-teacher-turnover-paper.pdf

- Saldaña J, Omasta M. Qualitative research: Analyzing life. 2. Sage Publishing Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl KA. Social and emotional learning and teachers. The Future of Children. 2017;27(1):137–155. doi: 10.1353/foc.2017.0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbach, J. (2021, August 5). Outsized and Opaque: K–12 Pandemic Education Spending. The Heritage Foundation. https://www.heritage.org/education/report/outsized-and-opaque-k-12-pandemic-education-spending

- Song SY, Wang C, Espelage DL, Fenning P, Jimerson SR. COVID-19 and school psychology: Adaptations and new directions for the field. School Psychology Review. 2020;49(4):431–437. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2020.1852852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer SD, Mason EC. Addressing elementary school teachers’ professional stressors: Practical suggestions for schools and administrators. Educational Administration Quarterly. 2013;49(5):809–837. doi: 10.1177/0013161X13482578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, E. D., & Woo, A. (2021). Job-related stress threatens the teacher supply: Key findings from the 2021 State of the U.S. Teacher Survey. RAND Corporation. RR-A1108–1, 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-1.html

- Subica AM, Claypoole KH, Wylie AM. PTSD'S mediation of the relationships between trauma, depression, substance abuse, mental health, and physical health in individuals with severe mental illness: Evaluating a comprehensive model. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;136(1–3):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley, P. (2017). Through the lens of novice teachers: A lack of administrative support and its influence on self-efficacy and teacher retention issues (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Southern Mississippi).

- Taylor SS. Trauma-informed care in schools: A Necessity in the time of COVID-19. Beyond Behavior. 2021;30(3):124–134. doi: 10.1177/10742956211020841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. (2021). Strategies for Using American Rescue Plan Funding to Address the Impact of Lost Instructional Time, Washington, DC. https://www2.ed.gov/documents/coronavirus/lost-instructional-time.pdf.

- Will, M. (2021). Teachers are stressed out, and it’s causing some to quit. Education Week.https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/teachers-are-stressed-out-and-its-causing-some-to-quit/2021/02

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.