Abstract

The culturability of three Campylobacter jejuni strains and their infectivity for day-old chicks were assessed following storage of the strains in saline. The potential for colonization of chicks was weakened during the storage period and terminated 3 to 4 weeks before the strains became nonculturable. The results from this study suggest that the role of starved and aged but still culturable campylobacters may be diminutive, but even more, that the role of viable but nonculturable stages in campylobacter epidemiology may be negligible. Even high levels of maternally derived anti-campylobacter outer membrane protein serum antibodies in day-old chicks did not protect the chicks from campylobacter colonization.

Worldwide, campylobacteriosis is one of the most common enteric diseases. One of the many reservoirs of Campylobacter infection is poultry. Some investigations have indicated that very low doses of thermophilic Campylobacter cells are sufficient to colonize chicks (1, 17, 26, 27, 32). However, the sources of Campylobacter infection in broiler flocks have usually remained undetermined due to the ubiquitous prevalence of the two most common Campylobacter species, Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. According to the results of survival experiments with Campylobacter spp. (3, 16, 30), the strains can survive for prolonged periods in laboratories (24). Campylobacter cells also are known to survive for an undetermined period in culturable form in the environment, most often in water (15, 24). However, the role of a Campylobacter-contaminated environment as a source of infection in broiler flocks is unclear, since the ability of Campylobacter cells to remain infective under environmental conditions has been little investigated. Furthermore, it has been proposed that Campylobacter cells that do survive in the environment are in a viable but nonculturable (VBNC) stage (24). The epidemiological significance of VBNC-stage Campylobacter cells from environmental waters is not clear-cut. On one hand, Campylobacter-contaminated water has been identified as an important risk factor for campylobacteriosis in some risk analyses (2, 6, 12, 14), and several reports of waterborne outbreaks of campylobacteriosis have been published (7, 21, 22). On the other hand, Newell et al. (19) found that an environmentally isolated Campylobacter strain loses most of its virulence after storage in water. Concerning the potential infectivity of VBNC-stage Campylobacter strains produced in laboratories, experimental studies also have been contradictory; some have had a negative outcome (8, 17, 31), and others have suggested that Campylobacter cells in VBNC stages can colonize chicks (13, 25, 28).

This study investigated the ability of three C. jejuni strains to colonize day-old chicks during storage of the strains in saline suspensions. The C. jejuni strains used were a broiler strain (G97-76595, serotype O:27), a human clinical isolate (Kl-5133, serotype O:2) (7), and a laboratory-adapted strain (Pen-6 ATCC 43434, serotype O:6), which was obtained from the Penner serotype collection (23). The dose-response relationship and the ability to colonize chicks on days 1, 9, 19, 30, and 39 of storage in saline were assessed. Suspensions of the strains were prepared from 24-h cultures grown on blood agar (blood agar base 2 [Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom] supplemented with 5% calf blood) by shaking of bacterial material in 0.9% saline at 2 to 4°C. For the dose-response experiments, the suspensions were used within 4 to 6 h. For the storage experiments, the suspensions were kept stationary under aerobic conditions in the dark at 16°C in screw-cap glass bottles. For each experiment, the CFU per milliliter was determined ca. 2 h before and ca. 2 h after each inoculation, and the inoculation dose was calculated as the average of the two CFU-per-milliliter totals. Total cell counts, which were determined by the acridine orange direct-count technique (11), remained constant throughout the experiments in all three suspensions.

Day-of-hatch chicks were obtained from a commercial Danish hatchery. Within 24 h after hatching, the chicks were wing-marked and all chicks were tested to determine whether they carried Campylobacter. The chicks were then inoculated with Campylobacter cells and housed in sterilized isolators (Montair Andersen, type HM 1500) floored with a grid. The dose-response relationship for each strain was assessed by inoculation of each of five groups of 9-day-old chicks with serial dilutions of the Campylobacter suspensions. Chicks were inoculated orally in the crop through a polystyrene tube, and Campylobacter colonization was confirmed on day 4 by culturing from a cloacal swab. For the storage experiment, groups of 10 chicks each were inoculated with stored suspension in the crop at days 1, 9, 19, 30, and 39. Campylobacter colonization was confirmed by culturing from a cloacal swab on day 6 and from a cecal swab on day 9, except for the experiment launched at day 30, which was prolonged for 16 days to allow more time for colonization to become established. A noninoculated group was included in each experiment as a control. Cecal tissue with the cranial end of the cecal tonsilla was removed from all chicks postmortem for histopathological examination.

Campylobacter cultures from cloacal and cecal swabs were produced by direct streaking of the swabs onto modified charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar (blood-free agar base with cefoperazone at a concentration of 32 mg/liter and amphotericin at a concentration of 10 mg/liter) (Oxoid) and incubated microaerobically in 7% O2–10% CO2–83% N2 at 42°C for 48 h. Plates that were culture negative at 48 h were reincubated for an additional 48 h. Campylobacter sp. identification was performed according to previously described methods (9).

Typing of the flaA gene of the inoculation strains and of strains isolated from colonized chicks was performed as an internal control. DNA was isolated from fecal samples from two randomly chosen Campylobacter-positive chicks within each experimental group. Genomic C. jejuni DNA was purified from a loopful of bacterial culture using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A 1,705-bp fragment of the C. jejuni flaA gene was amplified by PCR as described previously (18). Samples of the flaA PCR product were subsequently digested with DdeI (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) and AluI (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) separately, and the digests were analyzed by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis with a 100-bp DNA ladder (Life Technologies) as the molecular size marker.

Blood samples for monitoring of maternally derived serum anti-Campylobacter antibodies by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) procedure were collected from an extra batch of 10 chicks at each experiment. The average antibody response of this batch served as a reflection of the antibody response of all chicks in an experimental round. A C. jejuni outer membrane protein (OMP) preparation was produced from formalin-killed broth culture of a newly isolated C. jejuni strain (Penner 4-complex,) as described by Tagawa et al. (29). PolySorp microtiter plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with OMP antigen in 0.1 M sodium carbonate (pH 9.6) with 1 M NaCl overnight at 4°C and blocked for 15 min with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (T) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). On each plate, sample and reference sera were diluted 1:200 in BSA-T-PBS and were applied in duplicate for 1 h at room temperature, after which horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit antibody to chicken immunoglobulin (AP 162 P; Chemicon) diluted 1:4,000 in BSA-T-PBS was applied for 1 h. The mixture was then incubated with substrate (o-phenylenediamine–H2O2 in citrate buffer [pH 5.0]) for 20 min. Color development was stopped by adding 0.5 M H2SO2, and optical density was read at 490 nm. Four negative and three positive reference sera were included on all plates in order to control day-to-day variation and interplate variation (see Table 2 below). The OMP ELISA was designed so as to give broad-range detection of anti-C. jejuni antibodies, irrespective of serotype (B. Mariager, T. Nikopensius, E. M. Nielsen, S. On, B. Nielsen, M. Madsen, and P. Lind, unpublished data).

TABLE 2.

Serum antibody response in OMP-ELISA from day-old chicks (batch controls) at the time of the inoculation experiments

| Experimental group of chicks | Strain or day of storage (no. of chicks) | ELISA optical density (median and range)a |

|---|---|---|

| Dose-response experiments | G97-76595 (9) | 1.34 (0.87–1.92) |

| Kl-5133 (9) | 0.92 (0.19–1.34) | |

| Pen-6 (9) | 0.11 (0.06–0.15) | |

| Storage experiments | Day 1 (10) | 0.27 (0.16–0.61) |

| Day 9 (10) | 0.23 (0.10–0.36) | |

| Day 19 (10) | 0.25 (0.13–0.67) | |

| Day 30 (10) | 0.24 (0.12–0.45) | |

| Day 39 (10) | 0.21 (0.08–0.33) |

Mean optical densities at 490 nm of four negative control sera were 0.060, 0.055, 0.095, and 0.118; and those of three positive sera were 0.45, 1.08, and 1.59.

For histopathological examination, the cecal tissue was placed in 4% formaldehyde which was phosphate buffered (pH 7), embedded in paraffin, cut in 3-μm sections, mounted on microscope slides (SuperFrost/Plus; Menzel-Glaser, Braunschweig, Germany), and analyzed for the presence of C. jejuni by in situ hybridization (20).

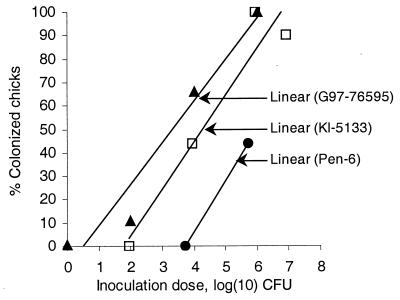

Results from the dose-response experiment are shown in Fig. 1. The dose-response relationship for each strain is expressed as a linear regression line calculated with the Microsoft Excel 97 SR-2 computer program (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, Wash.). Table 1 presents results from all inoculated groups from both the dose-response and the storage experiments, together with data on the inoculation material. In the storage experiments, the infectivity dropped between the day 9 and day 19 experiments; the percentage of infected chicks decreased from 100% on day 9 to 0% on day 19 for both the chicken and the human Campylobacter strains and from 90 to 10% for the laboratory-adapted strain. This decrease represents a conspicuous weakening of infectivity, since the inoculation doses given at day 19 (Table 1) would have been expected to colonize approximately 80% of the group inoculated with the chicken strain, 40% of the group inoculated with the human strain, and 35% of the group inoculated with the laboratory strain based on the dose-response relationship displayed in Fig. 1. None of the chicks was colonized after day 19, despite the fact that all three Campylobacter suspensions maintained culturability until around day 39. Prolongation of the experiment launched at day 30 to permit multiple intestinal passages of Campylobacter did not promote colonization, but we realize that the walking grid that floored the isolators was not optimal for that kind of experiment. Investigation of tissue sections from the ceca showed that the C. jejuni cells were localized in the lumens of the intestinal crypts. No invasion of the intestinal cells was observed.

FIG. 1.

Doses of C. jejuni strains in the dose-response experiments and the corresponding percentage of colonized birds in the experimental groups. The dose-response relationship is displayed as a linear regression line for each series of data. ▴, chicken strain G97-76595; ▫, the human strain Kl-5133; ●, laboratory strain Pen-6.

TABLE 1.

Colonization of day-old chicks after inoculation with three C. jejuni strains in dilution series of 24-h-old bacteria or under storage in saline suspensions at days 1, 9, 19, 30, and 39

| Strain (source) | Serotype and fla type | Dose-response experiments

|

Storage experiments

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial count (CFU/ml) in suspension | Inoculation dose (CFU/ml) | No. of chicks colonized/no. of chicks inoculated | Day of storage | CFU/ml of suspension | Inoculation dose (CFU/ml) | No. of chicks colonized/no. of chicks inoculated | ||

| G97-76595 (chicken) | O:27, flaA type C | 1.0 × 108 | 1.0 × 106 | 9/9 | 1 | 1.6 × 108 | 1.6 × 107 | 10/10 |

| 1.0 × 104 | 6/9 | 9 | 3.1 × 108 | 3.1 × 107 | 10/10 | |||

| 1.0 × 102 | 1/9 | 19 | 1.0 × 106 | 1.0 × 105 | 0/10 | |||

| 1.0 × 100 | 0/9 | 30 | 2.0 × 102 | 2.0 × 101 | 0/10 | |||

| 1.0 × 10−1 | 0/9 | 39 | 3.0 × 10−1 | 3.0 × 10−2 | 0/10 | |||

| Kl-5133 (human) | O:2, flaA type B | 8.8 × 107 | 8.8 × 106 | 8/9 | 1 | 2.2 × 107 | 2.2 × 106 | 10/10 |

| 8.8 × 105 | 9/9 | 9 | 2.3 × 107 | 2.3 × 106 | 10/10 | |||

| 8.8 × 103 | 4/9 | 19 | 4.6 × 104 | 4.6 × 103 | 0/10 | |||

| 8.8 × 101 | 0/9 | 30 | 4.3 × 102 | 4.3 × 101 | 0/10 | |||

| 8.8 × 10−1 | 0/9 | 39 | 9.0 × 10−1 | 9.0 × 10−2 | 0/10 | |||

| Pen-6 (laboratory adapted) | O:6, flaA type A | 5.7 × 107 | 5.4 × 105 | 4/9 | 1 | 3.4 × 108 | 3.4 × 107 | 7/10 |

| 5.4 × 103 | 0/9 | 9 | 3.7 × 107 | 3.7 × 106 | 9/10 | |||

| 5.4 × 101 | 0/9 | 19 | 2.7 × 106 | 2.7 × 105 | 1/10 | |||

| 5.4 × 10−1 | 0/9 | 30 | 1.5 × 103 | 1.5 × 102 | 0/10 | |||

| 5.4 × 10−3 | 0/9 | 39 | <1.0 × 10−1 | <1.0 × 10−2 | 0/10 | |||

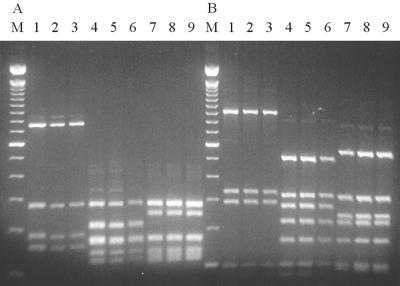

Figure 2 shows the results from the typing of the flaA gene of the inoculated strains and of isolates obtained from the cloacal or cecal swabs of colonized chicks at day 9 of the experiment. The three strains had clearly distinguishable flaA types. The flaA types were designated as follows: the Pen-6 strain, flaA type A; the Kl-5133 strain, flaA type B; and the G97-76595 strain, flaA type C. No changes in the Fla type were observed throughout the experiment. Thus, the storage in saline and the passage through the chickens had no influence on the stability of the fla types obtained with two different enzymes, which demonstrates the applicability of fla typing as a method of controlling possible contamination of strains between experimentally infected chickens in short-term studies. For long-term studies, others (10) have found that Fla typing cannot be considered a stable method for monitoring of Campylobacter strains, since intragenomic recombination between flaA and flaB genes may occur with time.

FIG. 2.

Fla typing of inoculation strains and strains isolated from infected chicks. The flaA gene was amplified by PCR and digested with either (A) AluI or (B) DdeI. M, molecular size marker (100-bp DNA ladder); lane 1, Pen-6 inoculation strain; lanes 2 and 3, isolates from chickens colonized with the Pen-6 strain; lane 4, Kl-5133 inoculation strain; lanes 5 and 6, isolates from chickens colonized with the Kl-5133 strain; lane 7, G97-76595 inoculation strain; lanes 8 and 9, isolates from chickens colonized with the G97-76595 strain. Lane numbers refer to the same information in both panels A and B.

The chicks that were used for the reported study had serum anti-Campylobacter OMP antibodies at levels that ranged from negative (no antibodies) to highly positive (Table 2), as evidenced by the ELISA responses of the corresponding batch control animals. This finding probably reflects the condition of Danish broiler flocks at stocking time, since Danish broiler parent flocks are often infected with Campylobacter. Surveillance of 16 parent flocks at a hatchery with a high biosecurity standard revealed no Campylobacter-free flocks at all, not even during the cold season (B. Hald and M. Madsen, unpublished data). In the dose-response experiment, the chicks inoculated with the Pen-6 strain had low levels of antibodies, whereas the chicks used for inoculation with the Kl-5133 and G97-76595 strains showed high levels of antibodies (Table 2). The reported serological levels do not indicate a potential protective effect for the OMP antibodies, because the groups with high antibody responses in the dose-response experiments were the groups that were colonized by low doses of either the chicken or human strain, whereas the group that needed high doses for colonization with the laboratory strain had OMP antibody levels that were close to the negative level. Thus, we consider it very unlikely that the low levels of antibody that were present in the groups of chickens inoculated with the stored bacteria interfered with establishment of colonization.

The minimal colonization dose (MCD), that is, the dose that would colonize at least one chick in one experimental group, can be extracted from the dose-response relationship displayed in Fig. 1. The calculated MCD was ca. 10 CFU for the chicken strain, ca. 100 CFU for the human strain, and ca. 10,000 CFU for the laboratory strain. For the chicken strain, the calculated dose has been confirmed in a recent experiment, in which the MCD obtained was between 2.7 and 27 CFU (B. Hald and M. Madsen, unpublished data).

The results from this study suggest that higher doses of Campylobacter strains from nonchicken sources are needed to colonize chicks when compared with doses of Campylobacter strains originating in chickens. This is in agreement with other data that point to chicken passage as a way of enhancing the ability of a strain to colonize chicks. Cawthraw et al. (5) have found that the colonization dose of a laboratory-adapted strain, C. jejuni 81116, decreased 10,000-fold to a dose of only 40 CFU per chick for maximal cecal colonization after a single chicken passage. Likewise, Stern et al. (27), by repeated chicken passages of a strain that was originally a poorly colonizing human strain, have produced a C. jejuni strain that consistently colonizes chickens. Furthermore, Newell et al. (19) suggest that the virulence of clinical strains is induced by the intestinal passage of the host.

According to our results, the infectivity of the C. jejuni strains weakened during the storage in saline, whereas the strains maintained normal culturability. None of the three Campylobacter suspensions investigated here colonized any of the chicks, even 3 to 4 weeks before loss of culturability. We propose the term “culturable but not infectious” for such populations of Campylobacter. Therefore, the results from this study question the epidemiological significance of environmental survivors, even ones that can readily be cultured and, even more, survivors that are viable but cannot be cultured. Newell et al. (19) have also found a weakening of strains from water sources. They found that water strains were less invasive and less cytotoxic to HeLa cells than were clinical strains of the same serotype and biotype. Most recent VBNC infection studies also have had a negative outcome (8, 17, 31), and it is noteworthy that none of those studies determined at which time the infectivity of the examined strains had actually terminated, since the infection experiments were not launched until after nonculturability was ensured. Some other studies claim, however, that the Campylobacter cells in the VBNC stage from aqueous suspensions can be resuscitated by intestinal passage (13, 28). According to our results, the chicken gut would not be the optimal site to expect the potential resuscitation of VBNC stages; the chance for resuscitation would be better under exquisite laboratory conditions. That is what a recent study (4) has shown by reported resuscitation of VBNC Campylobacter cells in eggs. VBNC stages seem to possess potential importance if judged by such results; nevertheless, our findings devalue the role of VBNC stages under natural conditions.

We conclude that the ability of three saline-stored C. jejuni strains to multiply under in vitro laboratory conditions did not reflect the potential for colonization of chickens and that the infectivity weakened and terminated before transformation into a VBNC stage could occur. The results from this study point to skepticism about an important epidemiological role for injured or aged environmental Campylobacter cells, even those that can still be cultured, and to the negligible role of VBNC stages in Campylobacter epidemiology. The fact that the chicks for these experiments were obtained under the same conditions as chicks for stocking at Danish broiler farms makes the results of this study relevant to ordinary broiler production. Even high levels of anti-Campylobacter OMP serum antibodies did not protect chicks from Campylobacter colonization when inoculated with doses of less than 100 CFU.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge laboratory technicians Annie Brandstrup, Connie Jenning Sørensen, and Helena Ellegaard Christiansen for excellent technical assistance during the experiments. We thank Eva Møller Nielsen for serotyping of strain G97-76595.

This study was supported by grant 96–01173 from the Danish Agricultural and Veterinary Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achen M, Morishita T Y, Ley E C. Shedding and colonization of Campylobacter jejuni in broilers from day-of-hatch to slaughter age. Avian Dis. 1998;42:732–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adak G K, Cowden J M, Nicholas S, Evans H S. The Public Health Laboratory Service national case-control study of primary indigenous sporadic cases of campylobacter infection. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:15–22. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buswell C M, Herlihy Y M, Lawrence L M, McGuiggan J T, Marsh P D, Keevil C W, Leach S A. Extended survival and persistence of Campylobacter spp. in water and aquatic biofilms and their detection by immunofluorescent-antibody and -rRNA staining. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:733–741. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.733-741.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappelier J M, Minet J, Magras C, Colwell R R, Federighi M. Recovery in embryonated eggs of viable but nonculturable Campylobacter jejuni cells and maintenance of ability to adhere to HeLa cells after resuscitation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5154–5157. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.5154-5157.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cawthraw S A, Wassenaar T M, Ayling R, Newell D G. Increased colonization potential of Campylobacter jejuni strain 81116 after passage through chickens and its implication on the rate of transmission within flocks. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:213–215. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800001333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eberhart-Phillips J, Walker N, Garrett N, Bell D, Sinclair D, Rainger W, Bates M. Campylobacteriosis in New Zealand: results of a case-control study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:686–691. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.6.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engberg J, Gerner-Smidt P, Scheutz F, Nielsen E M, On S L W, Mølbak K. Water-borne Campylobacter jejuni infection in a Danish town—a 6-week continuous source outbreak. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998;4:648–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1998.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fearnley C, Ayling R D, Newell D G. The failure of viable but non-culturable Campylobacter jejuni to colonize the chick model. Report of a WHO consultation on epidemiology and control of campylobacteriosis in animals and humans, Bilthoven, 25–27 April 1994. 85-87. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hald B, Wedderkopp A, Madsen M. Thermophilic Campylobacter spp. in Danish broiler production: a cross sectional survey and a retrospective analysis of risk factors for occurrence in broiler flocks. Avian Pathol. 2000;29:123–131. doi: 10.1080/03079450094153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrington C S, Thomson-Carter F M, Carter P E. Evidence for recombination in the flagellin locus of Campylobacter jejuni: implications for the flagellin gene typing scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2386–2392. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2386-2392.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hobbie J E, Daley R J, Jasper S. Use of Nucleopore filters for counting bacteria by fluorescence microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976;33:1225–1228. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.5.1225-1228.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins R S, Olmsted R, Istre G R. Endemic Campylobacter jejuni infection in Colorado: identified risk factors. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:249–250. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.3.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones D M, Sutcliffe E M, Curry A. Recovery of viable but non-culturable Campylobacter jejuni. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2477–2482. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-10-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapperud G, Skjerve E, Bean N H, Ostroff S M, Lassen J. Risk factors for sporadic Campylobacter infections: results of a case-control study in southeastern Norway. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3117–3121. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3117-3121.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korhonen L K, Martikainen P J. Comparison of the survival of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in culturable form in surface water. Can J Microbiol. 1991;37:530–533. doi: 10.1139/m91-089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazaro B, Carcamo J, Audicana A, Perales I, Fernandez-Astorga A. Viability and DNA maintenance in nonculturable spiral Campylobacter jejuni cells after long-term exposure to low temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4677–4681. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4677-4681.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medema G J, Schets F M, van de Giessen A W, Havelaar A H. Lack of colonization of 1 day old chicks by viable, non-culturable Campylobacter jejuni. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:512–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nachamkin I, Bohachick K, Patton C M. Flagellin gene typing of Campylobacter jejuni by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1531–1536. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1531-1536.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newell D G, McBride H, Saunders F, Dehele Y, Pearson A D. The virulence of clinical and environmental isolates of Campylobacter jejuni. J Hyg Camb. 1985;94:45–54. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400061118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordentoft S, Christensen H, Wegener H C. Evaluation of a fluorescence-labeled oligonucleotide probe targeting 23S rRNA for in situ detection of Salmonella serovars in paraffin-embedded tissue sections and their rapid identification in bacterial smears. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2642–2648. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2642-2648.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer S R, Gully P R, White J M, Pearson A D, Suckling W G, Jones D M, Rawes J C, Penner J L. Water-borne outbreak of campylobacter gastroenteritis. Lancet. 1983;i:287–290. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91698-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson A D, Greenwood M, Healing T D, Rollins D, Shahamat M, Donaldson J, Colwell R R. Colonization of broiler chickens by waterborne Campylobacter jejuni. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:987–996. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.987-996.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penner J L, Hennessy J N, Congi R V. Serotyping of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli on the basis of thermostable antigens. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1983;2:378–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02019474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rollins D M, Colwell R R. Viable but nonculturable stage of Campylobacter jejuni and its role in survival in the natural aquatic environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:531–538. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.3.531-538.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saha S K, Saha S, Sanyal S C. Recovery of injured Campylobacter jejuni cells after animal passage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3388–3389. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3388-3389.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanker S, Lee A, Sorrell T C. Experimental colonization of broiler chicks with Campylobacter jejuni. Epidemiol Infect. 1988;100:27–34. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800065523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern N J, Bailey J S, Blankenship L C, Cox N A, McHan F. Colonization characteristics of Campylobacter jejuni in chick coeca. Avian Dis. 1988;32:330–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stern N J, Jones D M, Wesley I, Rollins D M. Colonization of chicks by non-culturable Campylobacter spp. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;13:333–336. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tagawa Y, Haritani M, Ishikawa H, Yuasa N. Characterization of a heat-modifiable outer membrane protein of Haemophilus somnus. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1750–1755. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1750-1755.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terzieva S I, McFeters G A. Survival and injury of Escherichia coli, Campylobacter jejuni, and Yersinia enterocolitica in stream water. Can J Microbiol. 1991;37:785–790. doi: 10.1139/m91-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van de Giessen A W, Heuvelman C J, Abee T, Hazeleger W C. Experimental studies on the infectivity of non-culturable forms of Campylobacter spp. in chicks and mice. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:463–470. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800059124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young C, Ziprin R, Hume M, Stanker L. Dose response and organ invasion of day-of-hatch leghorn chicks by different isolates of Campylobacter jejuni. Avian Dis. 1999;43:763–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]