Abstract

Purpose:

The identification of actionable oncogenic alterations has enabled targeted therapeutic strategies for subsets of patients with advanced malignancies including lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). We sought to assess the frequency of known drivers and identify new candidate drivers in a cohort of LUAD from patients with minimal smoking history.

Experimental Design:

We performed genomic characterization of 103 LUADs from patients with ≤10 pack-year smoking history. Tumors were subjected to targeted molecular profiling and/or whole-exome sequencing and RNA-seq in search of established and previously uncharacterized candidate drivers.

Results:

We identified an established oncogenic driver in 98 of 103 tumors (95%). From one tumor lacking a known driver, we identified a novel gene rearrangement between OCLN and RASGRF1. The encoded OCLN-RASGRF1 chimera fuses the membrane-spanning portion of the tight junction protein occludin with the catalytic RAS-GEF domain of the RAS activator RASGRF1. We identified a similar SLC4A4-RASGRF1 fusion in a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cell line lacking an activating KRAS mutation and an IQGAP1-RASGRF1 fusion from a sarcoma in The Cancer Genome Atlas. We demonstrate these fusions increase cellular levels of active GTP-RAS, induce cellular transformation, and promote in vivo tumorigenesis. Cells driven by RASGRF1 fusions are sensitive to targeting of the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in vitro and in vivo.

Conclusions:

Our findings credential RASGRF1 fusions as a therapeutic target in multiple malignancies and implicate RAF-MEK-ERK inhibition as a potential treatment strategy for advanced tumors harboring these alterations.

INTRODUCTION

The therapeutic landscape for patients with advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) has been transformed in recent years with the introduction of small molecule targeted therapies and immune-directed therapies (1). The identification of actionable oncogenic drivers in NSCLC and development of an expanding repertoire of small molecule inhibitors of these drivers have provided new therapeutic opportunities for molecular subsets of NSCLC. Currently there are FDA-approved targeted therapies for patients with advanced NSCLC harboring activating alterations in EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF (V600E), KRAS (G12C), RET, MET, and TRK (2,3). In addition, emerging selective inhibitors of oncogenic ERBB2 and strategies targeting oncogenic NRG1 fusions are currently in clinical development (4,5). These activating driver alterations upregulate pathways promoting cell proliferation and survival including the RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K pathways.

Oncogenic drivers in NSCLC are generally mutually exclusive of one another, and many (including EGFR, ALK, ROS1, RET, and TRK alterations) are more prevalent in NSCLC from individuals with little or no smoking history. The frequency of oncogenic drivers in NSCLCs from Asian, European, and North American never-smokers has been reported (6–10). However, some of the more recently recognized drivers (such as MET Exon 14 splice alterations or RET fusions) were not consistently evaluated, and no known driver could be identified in up to 25% of tumors from never-smokers in these studies. In addition, individuals with a light smoking history were not included.

We evaluated a cohort of lung adenocarcinomas (LUADs) resected at our institution from individuals who have either never smoked or have minimal smoking history (≤10 pack-years). We investigated the prevalence of established oncogenic drivers in LUAD in this cohort and searched for novel candidate oncogenic alterations among tumors lacking known drivers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Participants, Sample Preparation, and Tumor Molecular Analysis

Study participants provided informed written consent under a research protocol approved by an institutional review board (Yale HIC #1010007459). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Subjects were enrolled between 2011 and 2019. Tumor molecular studies obtained as part of routine clinical care were performed by the Tumor Profiling Laboratory at Yale-New Haven Hospital. Testing approaches included hotspot mutation detection via polymerase chain reaction, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to identify gene rearrangements, or the Oncomine Comprehensive Assay v3 next generation sequencing platform to identify mutations and rearrangements involving 161 cancer-related genes.

25 tumors were subjected to whole-exome sequencing and RNA-seq. Tumor samples were immediately stored in RNAlater Solution (ThermoFisher Scientific) and flash frozen at the time of surgical resection or biopsy. Peripheral blood and/or normal tissue were also collected from study participants for use as a germline control. Genomic DNA and RNA was isolated using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For tumors without available fresh frozen samples (n=6), formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) slides were reviewed by a pathologist to select areas enriched for tumor. Tissue cores were generated, and nucleic acids were extracted using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Whole-Exome Sequencing and RNA-seq

One microgram of genomic DNA was sheared to a mean fragment length of 140 base pairs with subsequent addition of custom adapters (Integrated DNA Technologies). Adapter-ligated DNA fragments were then PCR amplified using custom-made primers with introduction of a unique 6 base index at one end of each DNA fragment. Exome capture was performed using biotinylated DNA probes (Nimblegen, SeqCap EZ Exome version 2, part #05860504001) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were sequenced using 150 bp paired end sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 according to the manufacturer’s protocols to a mean coverage of 150X for tumor and 75X for matched germline control. For RNA samples, the quality of total RNA was verified using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent). mRNA was isolated from total RNA using the mRNA-seq Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, Cat # 1004814). Samples were sequenced using 150 bp paired end sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 at 50 million reads per sample.

Sequencing reads from exome-captured samples were analyzed with a combination of germline and somatic variant calling. BAM files of aligned reads were created for each sample by aligning the sequencing reads to the GRCh37 human reference with decoy sequences (the “hs37d5” reference) using BWA MEM v0.7.15 (11), marking duplicates using Picard MarkDuplicates v2.17.11 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard), and then performing indel realignment and base quality score recalibration using GATK v3.4 (12). Then, variants were called using the tumor/normal BAM files in three ways: (A) a joint variant call using GATK HaplotypeCaller, GenotypeGVCFs and hard filtering following GATK 3.4 best practices; (B) somatic SNP variant calls using MuTect v2.7.1 (13); (C) somatic indel variant calls using Indelocator v33.3336 (14). The output from the three variant callers were merged using in-house scripts into a single VCF file, containing the union of GATK variants and MuTect/Indelocator somatic variants. Those variants were annotated using Annovar (15) and VEP (16).

Copy-number variant (CNV) regions were identified by calculating the mean read depth for each RefGene coding exon for the tumor and normal samples. Normalized tumor/normal read depth ratios were computed for each exon (normalized by the mean read depth of the tumor and normal across the exome), and a mean ratio for each 20 kb region of the genome containing an exon was computed. Those mean ratios were de-noised and segmented by circular binary segmentation using the DNAcopy (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DNAcopy.html) library from R. Regions with a value deviating from the expected 1.0 ratio were identified as CNVs. For each CNV, ploidy is calculated using a deviation step value of 0.5 for high tumor purity samples (purity ≥80%, a 0.4 step for purity between 40% and 80%, and 0.32 step for purity less than 40%), with the ploidy equaling 2 plus or minus the number of deviation steps.

For RNA-seq, reads were mapped to the human reference genome (hg19) using HISAT2 (v2.1.0) (17). Gene expression levels were quantified using StringTie (v1.3.3b) (18) with gene models (v27) from the GENCODE project. Differentially expressed genes were identified using DESeq2 (v1.22.1) (19). Fusion genes were identified using FusionCatcher v1.00 (https://github.com/ndaniel/fusioncatcher). Gene fusion events and exon-skipping events were manually inspected by loading BAM files into the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) (20).

Cell Lines and Reagents

PaCaDD137 cells were purchased from DSMZ (#ACC-711, RRID: CVCL_1850) and cultured in an 80% mixture of DMEM and Keratinocyte SFM (at 1:1), 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), and penicillin (100 units/mL) / streptomycin (100 μg/mL; Gibco). NIH3T3 cells were obtained from ATCC (#CRL-1658, RRID: CVCL_0594) and maintained in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco) and penicillin / streptomycin (Gibco). SU8686 (#CRL-1837, RRID: CVCL_3881) and HEK 293T (#CRL-3216, RRID: CVCL_0063) cells were obtained from ATCC and maintained in RPMI-1640 (Gibco) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco) and penicillin / streptomycin (Gibco). Ba/F3 cells (RRID: CVCL_0161) were kindly provided by the laboratory of Dr. Matthew Meyerson (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) and were maintained in RPMI-1640 (Gibco) with heat-inactivated 10% FBS (Gibco) and penicillin / streptomycin (Gibco) and 1 ng/mL interleukin-3 (IL-3; Gibco). Ba/F3 cells expressing OCLN-RASGRF1 were cultured in the absence of IL-3. Cell lines were tested for Mycoplasma using LookOut Mycoplasma PCR Detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich #MP0035) and were maintained in culture for no more than 3 months or 20 passages. Trametinib, pictilisib, BAY293, and sunitinib were purchased from Selleck Chemicals.

Cloning of Full-Length OCLN-RASGRF1, SLC4A4-RASGRF1, and IQGAP1-RASGRF1 cDNA

Total RNA from YLCB Tumor 9 (for OCLN-RASGRF1) or PaCaDD137 (for SLC4A4-RASGRF1) was used as a template for cDNA preparation with oligo-dT using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Full-length fusion transcripts were amplified using the Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England BioLabs). PCR primers were designed from the 5’ end of OCLN and SLC4A4 and 3’ end of RASGRF1. For OCLN-RASGRF1, a primary PCR was performed using forward primer CATCCTGAAGATCAGCTGACCATTG and reverse primer CGAATATGTACAGTATCATCTAGCACATGTCC. A secondary PCR was then performed using nested PCR primers with incorporation of attB recombination sites for Gateway cloning (Invitrogen). Sequences for these primers were GGGGACAACTTTGTACAAAAAAGTTGGCACCCCGCCATGTCATCCAGGCCTCTTGAAAGTCCAC (forward) and GGGGACAACTTTGTACAAGAAAGTTGGCAA TCAGGTGGGGAGTTTTGGTTCTATTCG (reverse). For amplification of SLC4A4-RASGRF1, PCR was performed using a forward PCR primer specific to SLC4A4 with incorporation of an attB recombination site (GGGGACAACTTTGTACAAAAAAGTTGGCACCATGGAGGATGAAGCTGTCCTGGACAG) and the same reverse primer with an attB site used for OCLN-RASGRF1.

For IQGAP1-RASGRF1, a primary PCR was performed using cloned OCLN-RASGRF1 as template with a forward primer incorporating the first two exons of IQGAP1 and the same reverse primer with an attB site described above. A secondary PCR was then performed using a forward PCR primer with incorporation of an attB site (GGGGACAACTTTGTACAAAAAAGTTGGCACCATGTCCGCCGCAGACGAGGTTGACGGG) and the same reverse primer used for the primary PCR.

PCR products were gel-purified and cloned into pDONR223 (Invitrogen) using BP Clonase (Invitrogen). OCLN-RASGRF1, SLC4A4-RASGRF1, and IQGAP1-RASGRF1 cDNAs were then recombined into the lentiviral expression vector pLX307 (Addgene, RRID: Addgene_41392) using LR Clonase (Invitrogen). pLX307 directs mammalian expression from the E1Fa promoter and contains a puromycin selectable marker. The entire coding sequences of all three RASGRF1 fusion cDNAs were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Lentivirus was produced using HEK 293T cells as previously described (21).

Antibodies and Immunoblotting

Cell lysis was performed with RIPA buffer (Abcam) supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma) and protease inhibitors (Roche). Lysates were fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad). Chemiluminescence was performed using SuperSignal West Pico or Femto Chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific). Antibody against RASGRF1 (ab111830, RRID: AB_10865863) was obtained from Abcam. Antibodies against AKT (#2920, RRID: AB_1147620), phospho-AKT (Ser 473; #4060, RRID: AB_2315049), ERK1/2 (#4695, RRID: AB_390779), phopho-ERK1/2 (Thr 202 / Tyr 204, #9106, RRID: AB_331768), cleaved human PARP (Asp214; #5625, RRID: AB_10699459), cleaved mouse PARP (#9548, RRID: AB_2160592), and actin (#3700, RRID: AB_2242334) were obtained from Cell Signaling. Anti-vinculin (#V9131, RRID: AB_477629) was obtained from Sigma.

RAS Activation Assay

HEK 293T cells were transduced with OCLN-RASGRF1, SLC4A4-RASGRF1, IQGAP1-RASGRF1, or green fluorescent protein (GFP) in pLX307 in the presence of 4 μg/mL polybrene. Cells were centrifuged at 2250 rpm for 30 minutes. 24 hours later, transduced cells were selected with 1 μg/mL puromycin for at least 5 days. Cell lysates were collected and subjected to RAS activation assays using the Active RAS Detection kit (Cell Signaling #8821). Briefly, cell lysates were incubated with glutathione resin and GST-Raf1-RBD according to the manufacturer’s instructions for affinity precipitation of GTP-bound RAS. Unbound proteins were cleared by centrifugation, and eluted samples containing GTP-bound RAS were subjected to Western immunoblotting using the provided RAS mouse antibody.

Confocal Microscopy

OCLN-RASGRF1, SLC4A4-RASGRF1, and IQGAP1-RASGRF1 cDNAs were separately cloned into the Gateway pcDNA-DEST53 vector (Thermo Scientific #12288015) which introduces an N-terminal GFP tag. HEK 293T cells were seeded in black 24-well, glass-bottom tissue culture plates (Eppendorf) coated with poly-d-lysine (PDL). The following day, cells were transfected with plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 24 hours after transfection, cells were treated with CellMask Deep Red Plasma Membrane stain (Thermo Scientific #C10046) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 880 Airyscan confocal microscope with a 63X oil immersion objective.

Cell Surface Protein Biotinylation and Purification

Cell surface protein biotinylation and purification were performed using the Pierce Cell Surface Protein Isolation kit (Thermo Scientific #89881) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, HEK 293T cells with ectopic expression of OCLN-RASGRF1 and PaCaDD137 cells expressing endogenous SLC4A4-RASGRF1 (3-4 ten cm dishes each) were incubated with the biotinylation reagent for 30 minutes on ice (for HEK 293T cells) or 10 minutes at room temperature (for PaCaDD137 cells). Following cell lysis, labeled surface proteins were affinity purified using NeutrAvidin agarose resin and eluted as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Anchorage-Independent Proliferation and Focus Formation Assays

NIH3T3 cells were transduced with OCLN-RASGRF1, SLC4A4-RASGRF1, IQGAP1-RASGRF1, GFP, or EML4-ALK in pLX307 in the presence of 4 μg/mL polybrene. Cells were centrifuged at 2250 rpm for 30 minutes. 24 hours later, transduced cells were selected with 0.75 μg/mL puromycin for at least 5 days. For anchorage-independent proliferation assays, 40,000 cells were plated in triplicate in growth media containing 0.4% agar on top of a layer of growth media in 0.8% agar in a 6-well tray. Cells were cultured in agar for 14 to 19 days with fresh media added weekly. For focus formation assays, 2 × 105 cells were plated per well of a 6-well tray and cultured for 3 weeks. Images from anchorage-independent proliferation assays and focus formation assays were captured using a Zeiss Observer A1 microscope with a 5X objective. For anchorage-independent proliferation assays, quantification of colony area was performed using ImageJ software.

Ba/F3 Transformation Assays

cDNAs encoding GFP or OCLN-RASGRF1 in pLX307 were introduced into Ba/F3 cells via lentiviral transduction with 8 μg/mL polybrene and centrifugation at 2250 rpm for 30 minutes. 24 hours later, transduced cells were selected with 1 μg/mL puromycin for at least 5 days. IL-3 concentrations were then reduced stepwise from 1 ng/mL to 0.01, 0.005, 0.001, and 0 ng/mL over approximately 2-3 weeks (until IL-3-independent growth was observed for cells expressing OCLN-RASGRF1).

Bioactive Small Molecule Inhibitor Screen

Wild-type Ba/F3 cells (Ba/F3 WT) and Ba/F3 cells expressing OCLN-RASGRF1 (Ba/F3 O-R) were screened with the Pharmakon-1600 (Microsource Discovery Systems) and NCI Approved Oncology Drugs Set (Version V) small molecule inhibitor libraries. Ba/F3 O-R and Ba/F3 WT cells were plated at 2000 cells / well and 200 cells / well, respectively, in 20 μL in black clear-bottom 384-well plates. Growth media for Ba/F3 WT cells was supplemented with 1 ng/mL IL-3. 20 nL of 10 mM DMSO stocks of each screening compound or DMSO drug vehicle control was transferred by Echo Acoustic Dispenser (Labcyte) to assay plates containing Ba/F3 O-R or Ba/F3 WT for a final screening compound concentration of 10 μM. After 72 hours, cell viability was determined with Cell-Titer Glo (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To enable data comparison across all test plates, raw data for the library compounds from each plate was normalized to the vehicle control data from the same plate to calculate percent viability. Compounds inhibiting cell viability >6.5 standard deviations above drug vehicle controls (<25% viability) in Ba/F3 O-R and with >60% viability in Ba/F3 WT were selected for further characterization with dose-response studies at concentrations of 10, 5, 2.5, and 1.25 μM using the same approach as for the screen.

Cell Viability Assays and RASGRF1 knockdown

Ba/F3, PaCaDD137, or SU8686 cells were seeded in 96-well microtiter plates. Drug or drug vehicle was added on the same day (for Ba/F3 cells) or 24 hours after seeding (for PaCaDD137 and SU8686 cells). Following 4-5 days of drug exposure, cell viability was determined using the Cell Titer-Glo luminescent assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was measured with a Spectramax M3 plate reader (Molecular Devices). Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software.

siRNA reagents targeting RASGRF1 (siRNA ID# SASI_Hs01_00211038, SASI_Hs01_00211039, SASI_Hs01_00211040) or negative control (MISSION siRNA Universal Negative Control #1, #SIC001) were purchased from Sigma. PaCaDD137 cells were transfected with 50 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Thermo Scientific #13778075) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for reverse transfection in a 24-well format for Western immunoblotting or a 96-well format for cell viability assays. For Western immunoblotting, lysates were prepared 72 hours after transfection. For cell viability assays, viability was determined using Cell Titer-Glo 7 days after transfection (without repeat siRNA transfection).

Xenograft Studies

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with Yale Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines under an approved research protocol. For tumorigenesis studies, ten million cells (NIH3T3 cells expressing GFP, OCLN-RASGRF1, SLC4A4-RASGRF1, or IQGAP1-RASGRF1) were implanted subcutaneously into the right flank of 8-week-old, female, immune-deficient Rag2/IL2RG (R2G2) double knockout mice (Envigo) in the presence of Matrigel (Corning). Tumor dimensions were recorded by caliper measurements at 3-day intervals. Volumes were calculated using the formula (0.5 x length x width2). Mice were euthanized when tumors reached 1000 mm3 or at the end of the study on Day 28 post-implantation.

For trametinib dosing studies, five million PaCaDD137 cells suspended in a 1:1 mix of Matrigel (Corning) and OptiMEM reduced serum medium (Gibco) were implanted subcutaneously into the right flank of 8-week-old, female R2G2 mice. Mice bearing ~100 mm3 palpable tumors on post-implantation day 7 were randomized to trametinib or vehicle treatment arms (n=10 each). A stock solution of 4 mg/mL trametinib (Cayman Chemical) was formulated in DMSO and diluted to 0.25 mg/mL in PBS. An equivalent volume of DMSO was dissolved in PBS for vehicle. Trametinib (1 mg/kg) or vehicle (6.25% DMSO) in a volume of 100 μL was administered daily by intraperitoneal injection. This trametinib dosing regimen was previously established as well-tolerated with potent MEK inhibition (22). Tumor dimensions were recorded by caliper measurements at 3-day intervals with tumor volumes calculated as above. The experiment was terminated and mice were euthanized when a tumor in any one mouse reached a volume of 1000 mm3.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to assess differences between experimental groups with at least 3 biological replicates per experiment. Data is shown as mean with standard error (SEM). p ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data Availability

Sequencing data has been deposited to dbGaP (study accession phs002556.v1.p1) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap.

RESULTS

Evaluation of Established Oncogenic Drivers in LUAD from Light or Never-Smokers

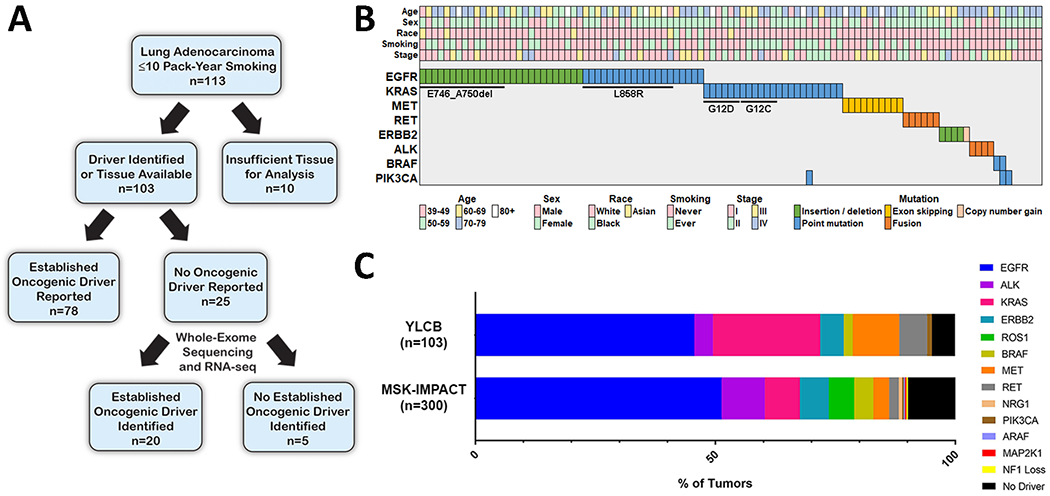

Since 2011, the Yale Lung Cancer Biorepository (YLCB) has acquired tumor specimens and peripheral blood under an IRB-approved research protocol from over 800 individuals with NSCLC treated at our institution. This effort focuses on patients with early-stage NSCLC amenable to surgical resection. Within the YLCB, we identified LUADs obtained from 113 individuals with ≤10 pack-year smoking history (Fig. 1A). Tissue blocks from 10 of these tumors had been previously exhausted before comprehensive molecular profiling could be performed. For the remaining 103 tumors, either an oncogenic driver had already been identified or there was archival tumor available for molecular profiling. Clinical characteristics associated with these 103 study participants are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

Overview of genomic characterization of lung adenocarcinomas (LUADs) from light or never-smokers. A. Schematic summarizing the approach for genomic characterization of LUADs from the Yale Lung Cancer Biorepository (YLCB). B. Established oncogenic drivers identified from 103 LUADs from light (≤10 pack-year) or never-smokers in the YLCB. C. Frequency of oncogenic drivers identified in the 103 profiled LUADs in the YLCB is shown. Below, frequency of oncogenic drivers identified in 300 advanced LUADs from never-smokers in the MSK-IMPACT clinical sequencing cohort is shown. MSK-IMPACT data was accessed via the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (https://cbioportal.org).

78 of the 103 evaluable tumors harbored an established oncogenic driver identified by tumor molecular profiling obtained during routine clinical care (see Materials and Methods). Identified molecular drivers from these 78 tumors included activating alterations in EGFR, KRAS, ALK, ERBB2, RET, and BRAF. An established driver was not reported in the remaining 25 tumors, although these had not been subjected to comprehensive molecular analysis (Fig. 1A). To further characterize these 25 tumors, we isolated DNA and RNA and performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) and RNA-seq. Genomic DNA extracted from matched peripheral blood was subjected to WES as a germline control for each tumor. Among the 25 tumors, an established driver was identified in 20 and included activating alterations in EGFR, KRAS, ERBB2, ALK, RET, PIK3CA, and MET. In all 20 cases, the driver alteration was not previously identified because either no molecular profiling had been performed or a testing platform designed to capture that alteration had not been utilized. In total, an oncogenic driver was identified in 98 of 103 (95%) LUADs evaluated (Fig. 1B, Table 1). Consistent with prior reports, nearly half of the tumors harbored activating EGFR alterations (n=47) (7–10). Among these were 25 tumors with EGFR Exon 19 deletion, 15 with L858R, and 2 with Exon 20 insertions. Activating KRAS alterations were observed in 23 tumors including 6 with a KRAS G12C mutation. One tumor with a KRAS G12A alteration had a concurrent PIK3CA H1047R mutation. We observed MET Exon 14 splice alterations in 10 tumors (Supplementary Fig. S1A). ERBB2 alterations were identified in 5 tumors, including 4 with activating mutations and 1 with marked copy number gain (24X ploidy and 22.9-fold increased expression by RNA-seq; Supplementary Fig. S1B). Activating RET (n=6) and ALK (n=4) rearrangements were associated with increased RET and ALK expression, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1C, D). BRAF V600E was identified in 2 tumors, including one with a concurrent PIK3CA E542K alteration. An activating PIK3CA H1047R mutation was identified in one tumor. Activating alterations in other established oncogenic drivers (including ROS1, TRK, NRAS, NRG1, RIT1, ARAF, and MAP2K1) were not identified in this cohort.

Table 1:

Oncogenic Drivers Identified from YLCB Tumors

| EGFR (n=47) | Alteration | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Exon 18 | p.G719C | 1 |

| Exon 18 | p.G719S; p.S768I | 1 |

| Exon 19 | p.E746_A750del | 14 |

| Exon 19 | p.E746_A750insV; p.T751P | 1 |

| Exon 19 | p.E746_S752delinsV | 4 |

| Exon 19 | p.L747_T751delinsQ | 1 |

| Exon 19 | p.L747_T751del | 2 |

| Exon 19 | p.L747_T751insP | 1 |

| Exon 19 | p.L747_P753insS | 1 |

| Exon 19 | p.A750_K754del | 1 |

| Exon 20 | p.M766delinsMASV | 1 |

| Exon 20 | p.S768_D770dup | 1 |

| Exon 21 | p.L858R | 13 |

| Exon 21 | p.L858R; p.A817G | 2 |

| Exon 21 | p.L861Q | 3 |

| KRAS (n=23) | Alteration | Frequency |

|

| ||

| Exon 2 | p.G12A | 3 |

| Exon 2 | p.G12C | 6 |

| Exon 2 | p.G12D | 6 |

| Exon 2 | p.G12F | 1 |

| Exon 2 | p.G12V | 4 |

| Exon 2 | p.G13C | 1 |

| Exon 2 | p.G13R | 1 |

| Exon 3 | p.Q61H | 1 |

| MET Exon 14 (n=10) | Alteration | Frequency |

|

| ||

| Exon 14 | D1010N | 1 |

| Exon 14 | Splice site alteration (c.2942-1G>C) | 1 |

| Exon 14 | Splice site alteration (c.3082+2T>C) | 1 |

| Exon 14 | Exon 14 skip detected by RNA-seq | 7 |

| RET (n=6) | Alteration | Frequency |

|

| ||

| CCD6-RET | 1 | |

| KIF5B-RET | 5 | |

| ERBB2 (n=5) | Alteration | Frequency |

|

| ||

| p.E770delins EAYVM | 1 | |

| p.A775_G776insYVMA | 2 | |

| p.Y772_A775dup | 1 | |

| 24X copy number gain | 1 | |

| ALK (n=4) | Alteration | Frequency |

|

| ||

| EML4-ALK | 4 | |

| BRAF (n=2) | Alteration | Frequency |

|

| ||

| p.V600E | 2 | |

| PIK3CA (n=1) | Alteration | Frequency |

|

| ||

| p.H1047R | 1 | |

We next sought to confirm the frequency of oncogenic drivers in an independent cohort. Using the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (23), we queried data from the MSK-IMPACT Clinical Sequencing Cohort to identify LUADs from never-smokers profiled with hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing of up to 410 cancer-associated genes using the MSK-IMPACT platform. In contrast to our cohort (which consisted primarily of treatment-naïve early-stage LUAD), most tumors profiled with MSK-IMPACT represent advanced and often heavily treated disease (24). Of 300 profiled LUADs from never-smokers in the database, we found that 271 tumors (90%) harbored established activating alterations (Fig. 1C). Combined findings from these two datasets suggest an established driver oncogene may be identified in upwards of 90% of LUADs from individuals with ≤10 pack-year smoking history.

Identification of RASGRF1 Fusions

An established oncogenic driver was not identified in 5 YLCB tumors (Fig. 1A, B). Four tumors were obtained from never-smokers, while one occurred in a patient with an 8 pack-year smoking history (Fig. 1B). We examined WES and RNA-seq data from these 5 tumors in search of novel candidate drivers. Among these, Tumor 9 was a Stage I LUAD obtained from a 59 year-old Caucasian female never-smoker. This patient presented with an incidental finding of a right lower lobe lung nodule that increased in size to 2 cm on subsequent imaging and was ultimately resected by lobectomy. Histologic analysis demonstrated acinar-predominant features (85%) with minor components of lepidic (10%) and papillary with mucinous features (5%). Adjuvant therapy was not indicated, and to date the patient has not experienced tumor recurrence.

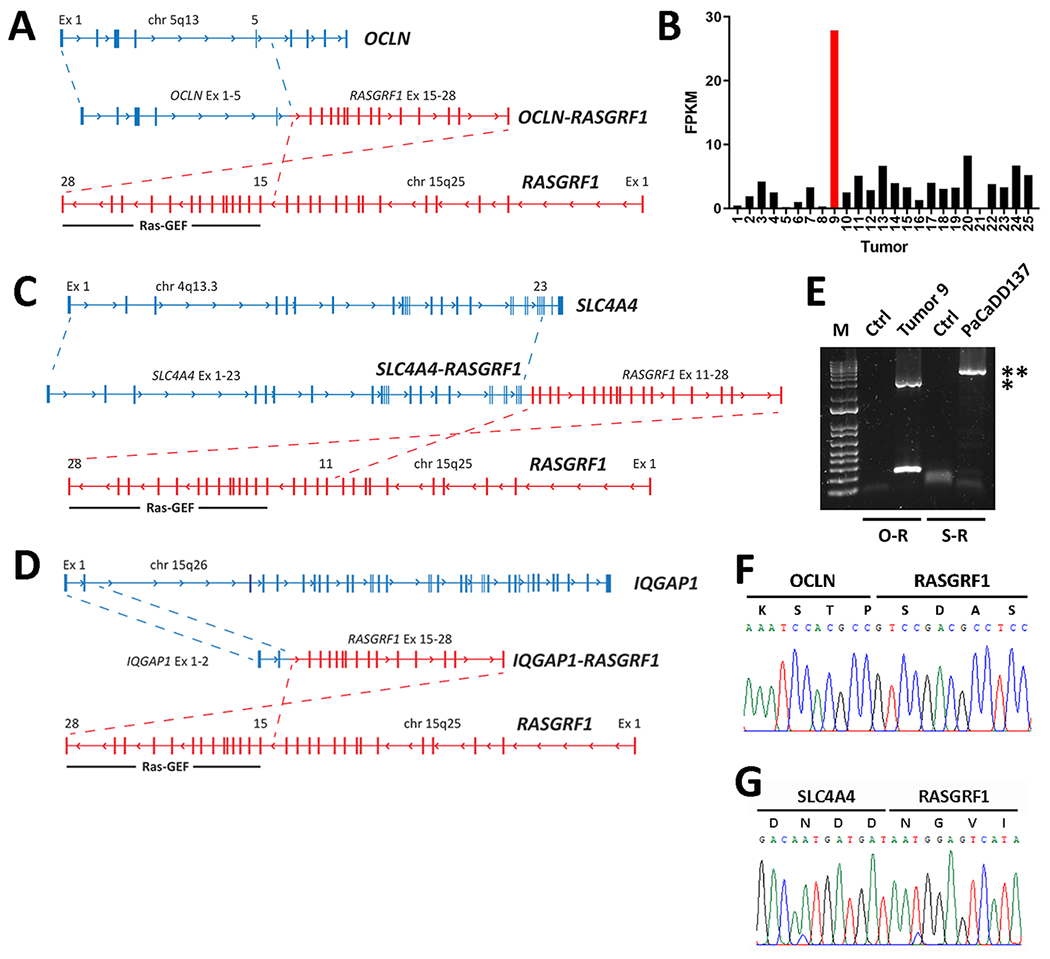

From RNA-seq of Tumor 9, we identified a gene rearrangement predicted to encode an N-terminal segment of the tight junction transmembrane protein occludin (OCLN) fused in-frame with a C-terminal segment of the guanine exchange factor (GEF) RASGRF1 (Fig. 2A). We identified 26 unique reads spanning the fusion, which occurred between the 3’ end of Exon 5 of OCLN and the 5’ end of Exon 15 of RASGRF1. Exons 1-5 of OCLN span all 4 transmembrane domains of the encoded protein but include only a portion of the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail. The C-terminal Ras-GEF domain of RASGRF1 catalyzes the dissociation of GDP from RAS family proteins, promoting RAS activation via transition from inactive GDP-bound RAS to activated GTP-bound RAS (25). The entire Ras-GEF domain of RASGRF1 is preserved within the putative OCLN-RASGRF1 fusion protein and was previously shown to have catalytic activity in the absence of the N-terminus of RASGRF1 (26). Furthermore, overexpression of wild-type RASGRF1 promotes transformation of mouse fibroblasts (26).

Figure 2.

Identification and characterization of RASGRF1 fusions. A. Schematic depicting a gene rearrangement identified from Tumor 9 in the Yale Lung Cancer Biorepository (YLCB) that generates OCLN-RASGRF1 from an in-frame fusion joining Exon 5 of OCLN with Exon 15 of RASGRF1. B. Number of reads mapping to the 3’ portion of RASGRF1 preserved in OCLN-RASGRF1 is shown for the 25 lung adenocarcinomas subjected to RNA-seq. Data is displayed in fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM). Tumor 9 is shown in red. C. Schematic depicting a gene rearrangement identified from PaCaDD137 cells that generates SLC4A4-RASGRF1 from an in-frame fusion joining Exon 23 of SLC4A4 with Exon 11 of RASGRF1. D. Schematic depicting a gene rearrangement identified from a giant cell sarcoma in The Cancer Genome Atlas (ID# TCGA-FX-A3TO) that generates IQGAP1-RASGRF1 from an in-frame fusion joining Exon 2 of IQGAP1 with Exon 15 of RASGRF1. E. RT-PCR amplification of the full-length 3 kb OCLN-RASGRF1 (O-R) and 5.3 kb SLC4A4-RASGRF1 (S-R) fusion transcripts from YLCB Tumor 9 and PaCaDD137 cells, respectively. Control (ctrl) PCR with no template is shown for each primer pair. Bands corresponding to amplified O-R and S-R fusions are indicated by a single asterisk and double asterisk, respectively. A DNA size marker (1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder from Thermo Scientific) is shown. F. Sanger sequencing of OCLN-RASGRF1 spanning the fusion breakpoint. G. As in F, except for SLC4A4-RASGRF1.

In normal human tissues, OCLN is highly expressed in thyroid and lung while RASGRF1 is expressed primarily in brain (with lesser expression in lung) (27). We reasoned that the OCLN-RASGRF1 fusion could promote expression of the C-terminal Ras-GEF domain under the OCLN promoter. To assess this, we compared RASGRF1 expression (using reads mapping to the C-terminal segment included in OCLN-RASGRF1) across all 25 LUADs subjected to RNA-seq. Among these, expression of RASGRF1 in Tumor 9 was 8.7-fold higher than the mean RASGRF1 expression in the other 24 tumors (Fig. 2B).

We next used the Cancer Dependency Map (https://depmap.org/portal) to search for similar fusions in sequenced cancer cell lines (28). We identified a cell line (PaCaDD137) derived from a 75 year-old Caucasian female with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) harboring a similar gene rearrangement fusing Exons 1-23 of SLC4A4 in-frame with Exons 11-28 of RASGRF1 (Fig. 2C) (29). SLC4A4 encodes a transmembrane sodium bicarbonate cotransporter that is highly expressed in kidney and pancreas, suggesting this gene rearrangement could induce expression of the C-terminal RAS-GEF domain in pancreatic cells under the SLC4A4 promoter (27). Unlike most PDACs, PaCaDD137 lacks an activating KRAS mutation. Using RNA-seq data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), we examined RASGRF1 expression across 1378 cancer cell lines (including PaCaDD137 and 51 additional PDAC cell lines) (28). RASGRF1 expression was higher in PaCaDD137 cells than in 82% of PDAC cell lines and 88% of total CCLE lines (Supplementary Fig. S2).

We also searched the Tumor Fusion Gene Data Portal (https://tumorfusions.org) for RASGRF1 fusions. Fusion genes in the portal are identified using RNA-seq data generated from tumors in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (30). We found a giant cell sarcoma of the retroperitoneum obtained from an 87 year-old Caucasian male (ID# TCGA-FX-A3TO) harboring an in-frame gene fusion between Exons 1-2 of IQGAP1 and Exons 15-28 of RASGRF1 (Fig. 2D). IQGAP1 is ubiquitously expressed and encodes a scaffolding protein with roles in cell-cell adhesion, cytoskeletal regulation, and other biological processes (31). Of note, only the first 52 of 1657 amino acids of IQGAP1 are predicted to be included in the IQGAP1-RASGRF1 fusion protein.

Next, we separately isolated RNA from Tumor 9 in the YLCB and from PaCaDD137 cells and prepared cDNA. PCR amplification of the full-length 3 kb OCLN-RASGRF1 and 5.3 kb SLC4A4-RASGRF1 fusion transcripts was performed from cDNA (Fig. 2E). We confirmed the in-frame fusions joining Exons 1-5 of OCLN with Exons 15-28 of RASGRF1 and Exons 1-23 of SLC4A4 with Exons 11-28 of RASGRF1 by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 2F, G; Supplementary Fig. S3, S4). We also derived a full-length 2.1 kb IQGAP1-RASGRF1 cDNA using PCR with cloned OCLN-RASGRF1 as template and a forward primer incorporating the first two exons of IQGAP1 (Supplementary Fig. S5, S6).

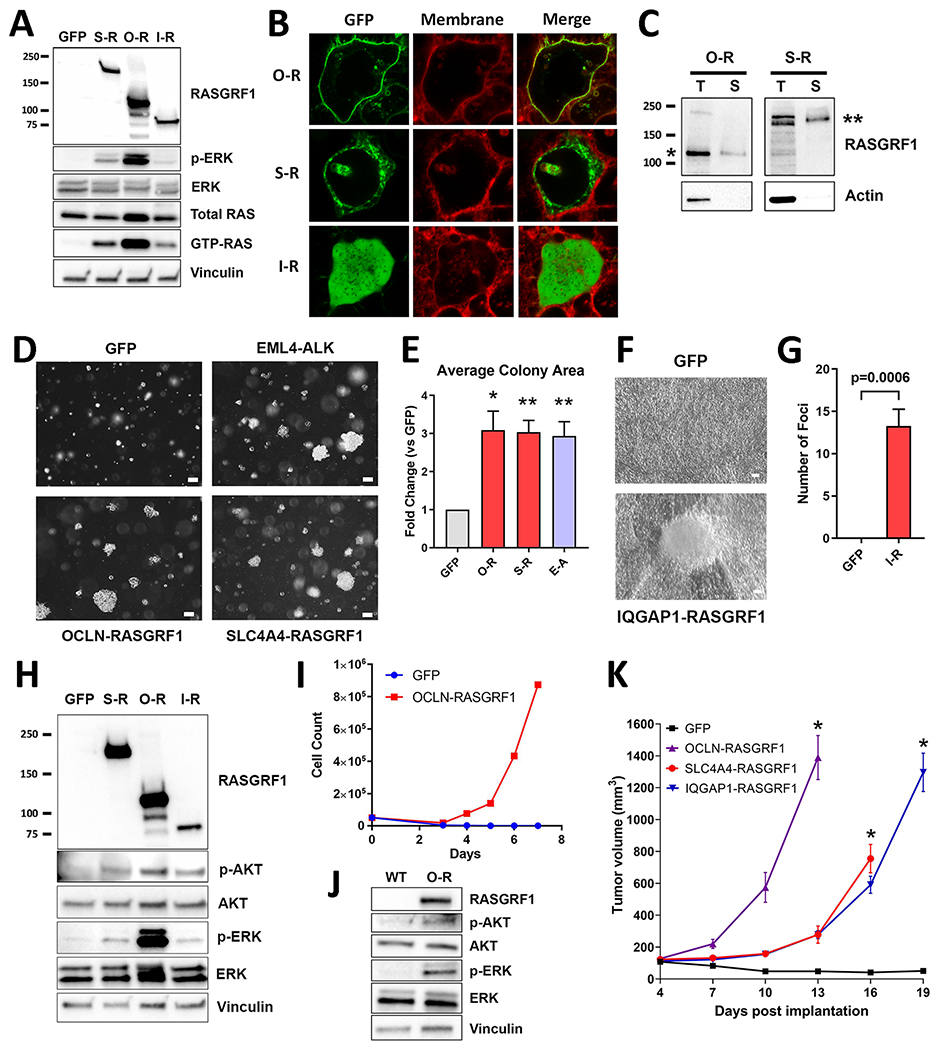

Functional Characterization and Subcellular Localization of RASGRF1 Fusions

RASGRF1 fusion cDNAs were cloned into a lentiviral expression vector and introduced into HEK 293T cells. An antibody against the C-terminus of RASGRF1 was used to confirm ectopic expression of the fusion proteins (Fig. 3A). Given the function of the C-terminal RAS-GEF domain of RASGRF1, we hypothesized that expression of RASGRF1 fusions increases levels of GTP-bound (active) RAS. Using an affinity purification assay for GTP-RAS, we observed a marked increase in levels of GTP-RAS in HEK 293T cells expressing OCLN-RASGRF1, SLC4A4-RASGRF1, or IQGAP1-RASGRF1 compared to green fluorescent protein (GFP; Fig. 3A). Furthermore, RAF-MEK-ERK signaling was upregulated with expression of RASGRF1 fusions, as evidenced by increased p-ERK (Fig. 3A). These effects appeared more robust with OCLN-RASGRF1 compared to SLC4A4-RASGRF1 and IQGAP1-RASGRF1.

Figure 3.

Functional characterization, subcellular localization, and oncogenic phenotypes of RASGRF1 fusions. A. Western immunoblotting of lysates from HEK 293T cells expressing GFP, SLC4A4-RASGRF1 (S-R), OCLN-RASGRF1 (O-R), or IQGAP1-RASGRF1 (I-R) to assess cellular levels of GTP-RAS and ERK activation (p-ERK). Molecular weight (left) is indicated in kDa. B. Confocal imaging of live HEK 293T cells expressing GFP-tagged O-R, S-R, or I-R fusions. Cells were imaged after treatment with CellMask Plasma Membrane stain (red). C. Cell surface protein biotinylation and purification were performed using lysates from HEK 293T cells with ectopic O-R expression or PaCaDD137 cells expressing endogenous S-R. Western immunoblotting of total lysate (T) and lysate after selection for biotinylated surface proteins (S) is shown. Molecular weight (left) is indicated in kDa. Bands corresponding to O-R and S-R are denoted by * and **, respectively. D. Anchorage-independent proliferation of NIH3T3 cells expressing GFP, EML4-ALK (E-A), OCLN-RASGRF1, or SLC4A4-RASGRF1 in soft agar assays. Cells were cultured in soft agar for 19 days. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. White marker represents 100 μm. E. Quantification of average colony area for NIH3T3 cells transduced with the indicated cDNAs (normalized to GFP) after 2-3 weeks. Mean and standard error for 3 independent experiments is shown. *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01 by two-tailed t-test. F. Tumor cell focus formation due to loss of contact inhibition of proliferating NIH3T3 cells expressing IQGAP1-RASGRF1 compared to GFP. Cells were cultured for 21 days. Images are representative of foci observed in 4 independent experiments. White marker represents 100 μm. G. Quantification of foci of NIH3T3 cells transduced with GFP or IQGAP1-RASGRF1 (I-R) after 3-4 weeks. Mean and standard error for 4 independent experiments is shown. H. Western immunoblotting of lysates from NIH3T3 cells expressing GFP, S-R, O-R, or I-R. I. Proliferation of Ba/F3 cells expressing GFP or OCLN-RASGRF1 after withdrawal of IL-3 (Day 0) is shown. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. J. Western immunoblotting of lysates from wild-type (WT) Ba/F3 cells cultured with 1 ng/mL IL-3 and Ba/F3 cells expressing O-R in the absence of IL-3. K. Xenografts of NIH3T3 cells expressing GFP or the indicated RASGRF1 fusions were generated in R2G2 mice (n=5 each), and tumor measurements were recorded. Each curve is terminated when tumor volume of one or more mice in that experimental arm reached 1000 mm3. Mean and standard error is shown. *p<0.001 by two-tailed t-test compared to GFP.

Two of the 3 fusions include a transmembrane protein (OCLN and SLC4A4) with the fusion endpoint occurring within the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail. We introduced GFP-tagged versions of RASGRF1 fusions into HEK 293T cells and assessed subcellular localization using confocal microscopy of live cells. We observed localization of OCLN-RASGRF1 at the plasma membrane while IQGAP1-RASGRF1 (which lacks membrane-spanning domains) was present diffusely throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, SLC4A4-RASGRF1 was not detected at the plasma membrane but instead showed a punctate cytoplasmic distribution (Fig. 3B), suggestive of localization to discrete subcellular (and possibly membranous) structures. To further support these findings, we performed surface protein biotinylation and isolated labeled cell surface OCLN-RASGRF1 from lysates of HEK 293T cells overexpressing the fusion (Fig. 3C). Consistent with imaging studies, we did not detect cell surface expression of SLC4A4-RASGRF1 in HEK 293T. We did, however, detect surface expression of endogenous SLC4A4-RASGRF1 from PaCaDD137 cells (Fig. 3C), suggesting potential differences in subcellular localization of the endogenous fusion in PaCaDD137 compared to exogenous expression in HEK 293T.

RASGRF1 Fusions Promote Cellular Transformation and In Vivo Tumorigenesis

To determine if RASGRF1 fusions induce cellular transformation, we expressed RASGRF1 fusions in NIH3T3 mouse fibroblasts and assayed anchorage-independent proliferation in soft agar. NIH3T3 cells expressing GFP or the established oncogenic fusion EML4-ALK were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Like EML4-ALK, we observed that ectopic expression of OCLN-RASGRF1 and SLC4A4-RASGRF1 induced robust colony formation in soft agar with a 3-fold increase in average colony size compared to GFP (Fig. 3D, E). IQGAP1-RASGRF1 did not promote anchorage-independent proliferation in these assays. However, IQGAP1-RASGRF1 did promote proliferation with loss of contact inhibition leading to tumor cell foci formation in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 3F, G). Ectopic expression of all 3 RASGRF1 fusions in NIH3T3 cells activated the RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K pathways, downstream effectors of RAS signaling (Fig. 3H).

We also expressed OCLN-RASGRF1 in the interleukin-3 (IL-3) – dependent Ba/F3 hematopoietic cell line to determine if OCLN-RASGRF1 induces IL-3 – independent proliferation. We maintained Ba/F3 cells expressing OCLN-RASGRF1 or GFP in 1 ng/mL IL-3. Over the course of 2-3 weeks, IL-3 concentrations were weaned before withdrawing IL-3 from growth media entirely. Ba/F3 cells expressing OCLN-RASGRF1 (but not GFP) demonstrated robust proliferation in the absence of IL-3 (Fig. 3I). Ectopic expression of OCLN-RASGRF1 in Ba/F3 cells was confirmed with Western immunoblotting and promoted RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K activation (Fig. 3J).

To determine whether RASGRF1 fusions promote tumorigenesis in vivo, we implanted NIH3T3 cells expressing RASGRF1 fusions into the flanks of immune-deficient mice. We observed robust tumor formation for each of the 3 RASGRF1 fusions with tumors driven by OCLN-RASGRF1 proliferating more rapidly than those driven by the other 2 fusions (Fig. 3K; Supplementary Fig. S7).

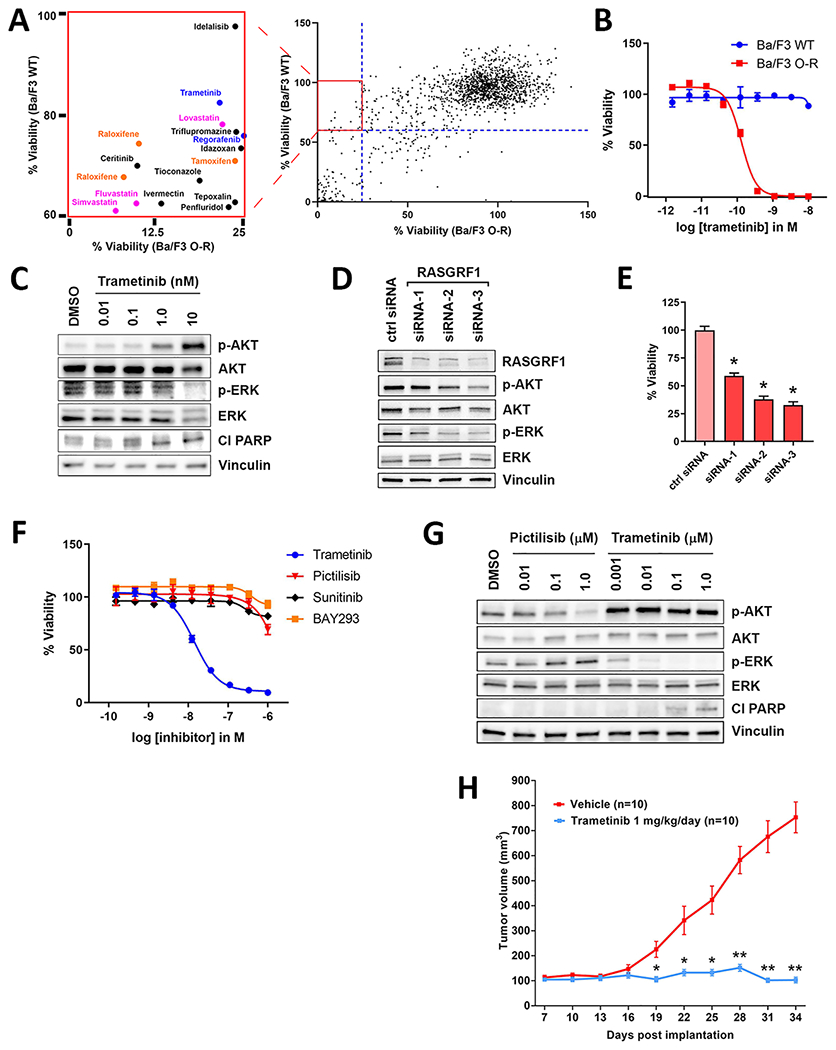

Ba/F3 Cells Driven by OCLN-RASGRF1 are Sensitive to RAF-MEK-ERK Inhibition

We next performed a screen of 1728 bioactive small molecule inhibitors to identify compounds with selective activity against Ba/F3 cells driven by OCLN-RASGRF1 (Ba/F3 O-R) compared to wild-type Ba/F3 cells (Ba/F3 WT). We identified 16 compounds that (at 10 μM) impaired viability of Ba/F3 O-R cells >6.5 standard deviations above drug vehicle controls (<25% viability) with >60% viability in Ba/F3 WT (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Table S2, S3). Among these 16 compounds were RAF-MEK-ERK inhibitors (the MEK inhibitor trametinib and multi-kinase inhibitor regorafenib), a delta subunit-specific PI3K inhibitor (idelalisib), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (fluvastatin, lovastatin, simvastatin), and anti-estrogens (raloxifene, tamoxifen; Fig. 4A; Supplementary Table S2). In addition to these 16 compounds, a second MEK inhibitor (cobimetinib) demonstrated potent activity against Ba/F3 O-R (<1% viability) although there was also activity against Ba/F3 WT (18% viability; Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 4.

Ba/F3 cells expressing OCLN-RASGRF1 (Ba/F3 O-R) and PaCaDD137 cells are sensitive to targeting of the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway with the MEK inhibitor trametinib. A. Viability of Ba/F3 O-R versus wild-type Ba/F3 cells (Ba/F3 WT) exposed to 1728 bioactive compounds at 10 μM for 72 hours is shown. Compounds with selective activity against Ba/F3 O-R (<25% viability for Ba/F3 O-R and >60% viability for Ba/F3 WT; boxed insert) were selected for further characterization. RAF-MEK-ERK inhibitors, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors, and anti-estrogens are indicated in blue, pink, and orange, respectively. B. Ba/F3 O-R or Ba/F3 WT cells were exposed to trametinib at the indicated concentrations. After 4 days, cell viability was determined using Cell Titer-Glo. Ba/F3 WT cells were cultured in the presence of 1 ng/mL IL-3. Mean and standard error is shown for all cell viability experiments, and each experiment was performed 3 times. C. Western immunoblotting of lysates from Ba/F3 cells expressing OCLN-RASGRF1 treated with trametinib at the indicated concentrations for 24 hours following serum starvation for 4 hours. Cl PARP, cleaved PARP. D. Western immunoblotting of lysates from PaCaDD137 cells transfected with non-targeting control siRNA (ctrl) or siRNAs targeting RASGRF1. E. Viability of PaCaDD137 cells assayed 7 days after transfection with the indicated siRNAs (normalized to control siRNA). Mean and standard error for 3 independent experiments is shown. *p<0.0001 by two-tailed t-test. F. PaCaDD137 cells were exposed to inhibitors at the indicated concentrations. After 5 days, cell viability was determined using Cell Titer-Glo. G. Western immunoblotting of lysates from PaCaDD137 cells treated with pictilisib or trametinib at the indicated concentrations for 48 hours. H. Xenografts of PaCaDD137 cells were generated in R2G2 mice (n=20). Once tumors reached 100 mm3, trametinib (1 mg/kg) or vehicle was administered daily (n=10 each) via intraperitoneal injection. Mean and standard error is shown. *p<0.01; **p<0.0001 by two-tailed t-test.

We next performed limited dose response studies of these 17 compounds in Ba/F3 O-R and Ba/F3 WT. Among the assayed compounds, the MEK inhibitors trametinib and cobimetinib showed the greatest selective activity against Ba/F3 O-R with <20% cell viability at 1.25 μM (Supplementary Fig. S8). To validate trametinib as a selective inhibitor of Ba/F3 O-R, we used a new drug stock in extended dose response studies and demonstrated that Ba/F3 O-R (but not Ba/F3 WT) are exquisitely sensitive to trametinib with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of approximately 150 pM (Fig. 4B). Trametinib potently inhibited ERK signaling (p-ERK) and induced apoptosis in Ba/F3 O-R (as evidenced by induction of PARP cleavage; Fig. 4C). Increased p-AKT levels with MEK inhibition suggests compensatory PI3K activation (Fig. 4C).

PaCaDD137 Cells are Sensitive to SLC4A4-RASGRF1 Depletion and RAF-MEK-ERK Inhibition

We next used siRNAs targeting RASGRF1 to knockdown SLC4A4-RASGRF1 levels in PaCaDD137 cells. Depletion of SLC4A4-RASGRF1 downregulated RAF-MEK-ERK and (to a lesser extent) PI3K signaling and markedly impaired cell viability (Fig. 4D, E). These findings suggest SLC4A4-RASGRF1 is a potential genetic dependency and therapeutic target in PaCaDD137 cells.

Like Ba/F3 O-R, PaCaDD137 cells are highly sensitive to trametinib (IC50 ~20 nM; Fig. 4F). Treatment of PaCaDD137 cells with trametinib potently inhibited ERK signaling and induced apoptosis (Fig. 4G). In contrast, the KRAS-mutant PDAC cell line SU8686 has limited sensitivity to trametinib (Supplementary Fig. S9A). To more broadly assess the sensitivity of PDAC cell lines to trametinib, we queried data from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer Project (GDSC2 dataset; https://www.cancerrxgene.org). Of 29 PDAC cell lines profiled with trametinib (including 27 KRAS-mutant lines), only 3 demonstrated an IC50 < 100 nM (Supplementary Fig. S9B) (32). These findings suggest PaCaDD137 cells are generally more sensitive to MEK inhibition than most PDAC cell lines.

Similar to our findings with the delta subunit-specific PI3K inhibitor idelalisib in Ba/F3 O-R, PaCaDD137 and Ba/F3 O-R cells showed only modest sensitivity to the pan-PI3K inhibitor pictilisib (Fig. 4F; Supplementary Fig. S9C). Unlike trametinib, pictilisib did not promote apoptosis in PaCaDD137 cells (Fig. 4G). Furthermore, the addition of pictilisib to trametinib did not show a substantial increase in activity compared to trametinib alone (Supplementary Fig. S9D, E). Taken together, our data indicates that cells driven by RASGRF1 fusions are markedly sensitive to inhibition of RAF-MEK-ERK but not PI3K signaling.

While direct inhibitors of the Ras-GEF domain of RASGRF1 have not been reported, inhibitors of the catalytic domain of the GEF SOS1 are in clinical development (33,34). However, these inhibitors are not predicted to have activity against RASGRF1 due to limited shared sequence identity between SOS1 and RASGRF1 (33). Consistent with this, neither PaCaDD137 cells nor Ba/F3 O-R cells were markedly sensitive to the SOS1 inhibitor BAY-293 in our assays (Fig. 4F; Supplementary Fig. S9F). Of note, a recent report described a patient with NSCLC harboring a TMEM87A-RASGRF1 fusion similar to those presented here who experienced an exceptional therapeutic response to the multi-kinase inhibitor sunitinib; however, the molecular basis of this response could not be identified (35). We did not observe marked sensitivity of PaCaDD137 cells or Ba/F3 O-R cells to sunitinib (Fig. 4F; Supplementary Fig. S9G).

Given the potent activity of trametinib in PaCaDD137 cells with endogenous SLC4A4-RASGRF1, we asked whether trametinib impairs proliferation of PaCaDD137 tumors in a xenograft model. PaCaDD137 xenografts were established by subcutaneous injection into the flanks of immune-deficient mice. Treatment with trametinib (1 mg/kg/day) resulted in marked tumor growth inhibition compared to vehicle (Fig. 4H; Supplementary Fig. S10). These findings suggest RAF-MEK-ERK inhibition as a potential therapeutic strategy for tumors harboring RASGRF1 fusions.

DISCUSSION

Here we report that over 90% of LUADs from individuals with ≤10 pack-year smoking history in a single-institution cohort harbor an established oncogenic driver. We observe similar findings in advanced LUADs from never-smokers in the MSK-IMPACT Clinical Sequencing Cohort. This represents a higher proportion than in some prior published reports in never-smoker North American and European populations, likely due to the growing number of driver oncogenes identified in recent years (7–10). In addition to frequent driver oncogenes in LUADs from never-smokers, nearly all (39 of 40) LUADs from patients with a light smoking history in our study harbored an established oncogenic driver. Notably, most of the identified driver mutations are actionable with FDA-approved targeted therapies currently available for alterations identified in 73 of the 103 tumors (71%). Our findings underscore the critical importance of comprehensive molecular profiling of LUADs (especially among light or never-smokers) as these studies can have important treatment implications in the advanced disease setting.

From one of the 5 tumors in our cohort without an established oncogenic driver, we cloned and characterized a novel in-frame OCLN-RASGRF1 gene fusion associated with increased RASGRF1 expression compared to other LUADs. A similar fusion (SLC4A4-RASGRF1) was identified from the PDAC cell line PaCaDD137, and a third fusion (IQGAP1-RASGRF1) was identified from a giant cell sarcoma characterized in TCGA. We demonstrate all 3 fusions increase endogenous levels of activated GTP-bound RAS, upregulate RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K signaling, and promote cell transformation and tumor formation. As approximately 90% of PDACs harbor activating KRAS alterations, it is notable that KRAS is not mutated in PaCaDD137 (29,36). This raises the possibility that PaCaDD137 could represent a RAS-driven tumor mediated by aberrant RASGRF1 activity rather than a primary activating alteration in KRAS itself. Indeed, other oncogenic gene fusions including NRG1 and ROS1 fusions have been identified in PDACs with wild-type KRAS (37–39). Our findings motivate the search for other RASGRF1 fusions in PDACs, particularly those with wild-type KRAS.

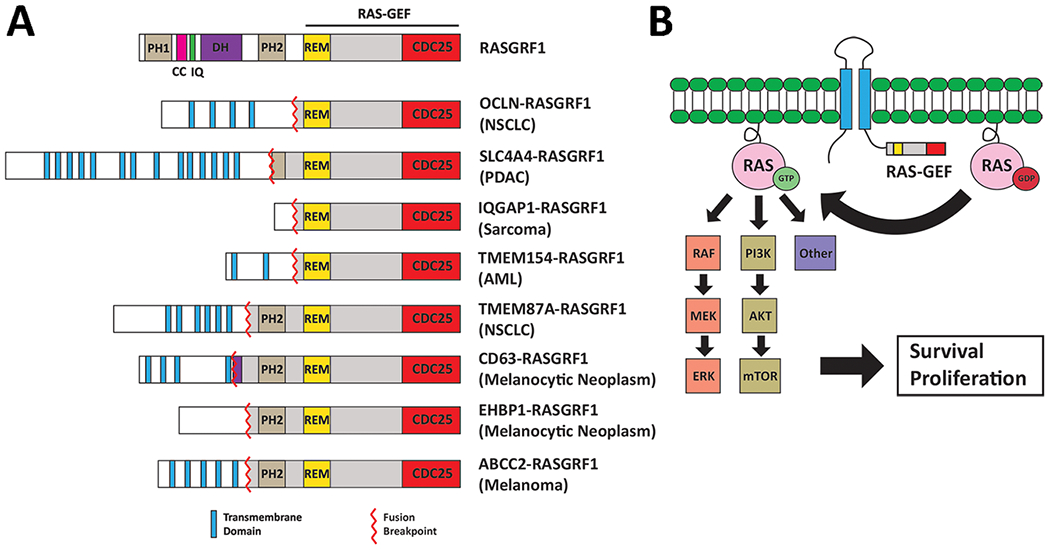

Additional RASGRF1 fusions have been recently reported. A TMEM154-RASGRF1 fusion containing Exons 15-28 of RASGRF1 was identified in tumor cells from a patient with relapsed acute myeloid leukemia, and a TMEM87A-RASGRF1 fusion containing Exons 8-28 of RASGRF1 was identified from an advanced LUAD in a never-smoker (35,40). Three additional RASGRF1 fusions were found in melanocytic neoplasms with spitzoid features (including one melanoma) (41). Strikingly, 6 of the 8 identified RASGRF1 fusions feature a transmembrane protein as the 5’ fusion partner with the rearrangement predicted to anchor the RAS-GEF catalytic domain of RASGRF1 to the cell membrane within a cytoplasmic C-terminal tail (Fig. 5A, B). As membrane association is required for RAS activation, the 5’ transmembrane fusion partner may serve to localize the RAS-GEF domain to membrane-associated RAS and thus facilitate activation (Fig. 5B). Consistent with this, prior studies have shown that targeting of the RASGRF1 catalytic domain to the cell membrane is sufficient to promote RAS activation and transformation (42). RAS signaling also occurs from endomembranes such as the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi, which may also be relevant sites in the context of transmembrane RASGRF1 fusions (43,44). We demonstrate that OCLN-RASGRF1 (but not SLC4A4-RASGRF1 or IQGAP1-RASGRF1) localizes to the plasma membrane in HEK 293T cells. We do not observe plasma membrane localization of SLC4A4-RASGRF1 (which includes membrane-spanning domains) in HEK 293T cells although localization to endomembranes cannot be excluded. In contrast, we did detect cell surface expression of endogenous SLC4A4-RASGRF1 in PaCaDD137 with cell surface biotinylation assays. Further studies will be required for comprehensive characterization of the localization of distinct RASGRF1 fusion proteins in different cell contexts and to determine whether the stronger RAS activating and transforming phenotypes we observe with OCLN-RASGRF1 are related to plasma membrane localization of this fusion in our models. In addition, it is unclear which specific RAS isoforms are activated by RASGRF1 fusions, although prior studies suggest wild-type RASGRF1 preferentially activates HRAS compared to KRAS or NRAS (45,46).

Figure 5.

Summary of known RASGRF1 fusions. A. Functional domains of full-length RASGRF1 are shown at the top. Below are 8 reported RASGRF1 fusions (including the 3 identified in the present study). TMEM154-RASGRF1, TMEM87A-RASGRF1, CD63-RASGRF1, EHBP1-RASGRF1, and ABCC2-RASGRF1 are previously reported (35,40,41). In 6 of the 8 fusions, the 5’ fusion partner is a membrane-spanning protein. The entire RAS-GEF catalytic domain of RASGRF1 is preserved in all fusions. The tumor type from which each RASGRF1 fusion was identified is indicated on the right. PH1, pleckstrin homology domain 1. CC, coiled coil domain. IQ, isoleucine-glutamine domain. DH, dbl-homology region. PH2, pleckstrin homology domain 2. REM, Ras-exchanger stabilization motif domain. NSCLC, non-small cell lung carcinoma. PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. AML, acute myeloid leukemia. B. Proposed model of RAS activation by transmembrane RASGRF1 fusions. The transmembrane N-terminal portion of the fusion anchors the catalytic RAS-GEF domain of RASGRF1 to the membrane, facilitating activation of membrane-associated RAS.

Our findings indicate that gene fusions involving the RAS-GEF domain of RASGRF1 are a recurrent driver alteration in multiple cancers. Of note, activating somatic mutations in the GEF SOS1 have been described in NSCLC, suggesting additional potential mechanisms of GEF-mediated oncogenic RAS activation in cancer (47). In addition, RASGRF2 fusions have recently been reported in melanocytic lesions (48). Further studies will be required to establish the frequency of RASGRF1 fusions and other GEF alterations in NSCLC, PDAC, and other malignancies. Our findings nominate the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway as a potential therapeutic target in RASGRF1-rearranged tumors. Other mechanisms of targeting RAS signaling (such as SHP2 or farnesyltransferase inhibition) may be relevant to explore in this context as well. Our work provides a rationale for broad assessment of RASGRF1 fusions as potentially actionable alterations in cancer. More generally, our findings highlight the potential of genomic characterization of LUADs from light and never-smokers without established oncogenic drivers to uncover oncogenic alterations that may be relevant for multiple malignancies.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

The identification of new oncogenic drivers has the potential to reveal unexpected mechanisms of tumorigenesis and to expand the reach of precision therapies in the treatment of advanced malignancies. Among a cohort of lung adenocarcinomas (LUADs) from patients with ≤10 pack-year smoking history, we identify an established oncogenic driver in 95% of tumors and a previously unreported OCLN-RASGRF1 gene rearrangement in a LUAD lacking a known driver. We report similar RASGRF1 fusions in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and sarcoma, indicating these are recurrent events across cancer lineages. RASGRF1 fusions promote RAS signaling, cellular transformation, and tumor formation. Cells driven by RASGRF1 fusions are sensitive to RAF-MEK-ERK inhibition, suggesting a therapeutic approach for advanced RASGRF1-rearranged tumors. Our findings motivate the search for additional RASGRF1 fusions in NSCLC, PDAC, sarcoma, and other cancers. This study also underscores the potential of comprehensive genomic characterization of LUAD from light or never-smokers to unveil oncogenic events occurring in diverse malignancies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the patients for their participation in this study. This work was supported by a Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Grant 2019080, F. Wilson), the National Institute of Health (K08CA204732, F. Wilson), the Beatrice Kleinberg Neuwirth Fund at Yale Cancer Center, and the Robert M. Harris Fund for Lung Cancer Research at Yale Cancer Center. The Yale Lung Cancer Biorepository is supported by the Yale SPORE in Lung Cancer (P50CA196530). We thank Mark Lemmon, Katerina Politi, Markus Müschen, and Mandar Muzumdar for helpful discussions. We thank Kaya Bilguvar, Irina Tikhonova, and Christopher Castaldi of the Yale Center for Genome Analysis for assistance with tumor sequencing. We thank Al Mennone and Sreevidya Santha for technical assistance with confocal microscopy and NIH3T3 tumor xenograft studies, respectively.

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

V.M. reports grants from AstraZeneca, Cybrexa Therapeutics, Enlivex Therapeutics, and Stradefy Biosciences outside the submitted work. K.A.S. reports personal fees from Moderna Inc, Shattuck Labs, Pierre-Fabre, AstraZeneca, EMD Serono, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Clinica Alemana de Santiago, Dynamo Therapeutics, PeerView, Abbvie, Fluidigm, Takeda/Millenium Pharmaceuticals, Merck-Sharp & Dohme, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Agenus, Torque Therapeutics, and research funding from Navigate Biopharma, Tesaro/GlaxoSmithKline, Moderna Inc, Takeda, Surface Oncology, Pierre-Fabre Research Institute, Merck-Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Ribon Therapeutics, and Eli Lilly outside the submitted work. R.S.H. reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bolt Biotherapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Candel Therapeutics, Checkpoint Therapeutics, Cybrexa Therapeutics, DynamiCure Biotechnology, eFFECTOR Therapeutics, Eli Lilly and Company, EMD Serono, Genentech and Roche, Gilead, HiberCell, I-Mab Biopharma, Immune-Onc Therapeutics, Immunocore, Janssen / Johnson and Johnson, Loxo Oncology, Mirati Therapeutics, NextCure, Novartis, Ocean Biomedical, Oncocyte, Oncternal Therapeutics, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Revelar Biotherapeutics, Ribon Therapeutics, Sanofi, and Xencor; R.S.H. reports research support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech and Roche, and Merck outside the submitted work; R.S.H. also serves as a board member (non-executive, independent member) for Immunocore and Junshi Pharmaceuticals. F.H.W. reports personal fees from Loxo Oncology and grants from Agios outside the submitted work. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang M, Herbst RS, Boshoff C. Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med 2021;27(8):1345–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang SR, Schultheis AM, Yu H, Mandelker D, Ladanyi M, Buttner R. Precision medicine in non-small cell lung cancer: Current applications and future directions. Semin Cancer Biol 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong DS, Fakih MG, Strickler JH, Desai J, Durm GA, Shapiro GI, et al. KRAS(G12C) Inhibition with Sotorasib in Advanced Solid Tumors. N Engl J Med 2020;383(13):1207–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh DY, Bang YJ. HER2-targeted therapies - a role beyond breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020;17(1):33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odintsov I, Lui AJW, Sisso WJ, Gladstone E, Liu Z, Delasos L, et al. The Anti-HER3 mAb Seribantumab Effectively Inhibits Growth of Patient-Derived and Isogenic Cell Line and Xenograft Models with Oncogenic NRG1 Fusions. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27(11):3154–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha SY, Choi SJ, Cho JH, Choi HJ, Lee J, Jung K, et al. Lung cancer in never-smoker Asian females is driven by oncogenic mutations, most often involving EGFR. Oncotarget 2015;6(7):5465–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couraud S, Souquet PJ, Paris C, Dô P, Doubre H, Pichon E, et al. BioCAST/IFCT-1002: epidemiological and molecular features of lung cancer in never-smokers. Eur Respir J 2015;45(5):1403–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korpanty GJ, Kamel-Reid S, Pintilie M, Hwang DM, Zer A, Liu G, et al. Lung cancer in never smokers from the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. Oncotarget 2018;9(32):22559–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grosse C, Soltermann A, Rechsteiner M, Grosse A. Oncogenic driver mutations in Swiss never smoker patients with lung adenocarcinoma and correlation with clinicopathologic characteristics and outcome. PLoS One 2019;14(8):e0220691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devarakonda S, Li Y, Martins Rodrigues F, Sankararaman S, Kadara H, Goparaju C, et al. Genomic Profiling of Lung Adenocarcinoma in Never-Smokers. J Clin Oncol 2021;39(33):3747–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009;25(14):1754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010;20(9):1297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Sivachenko A, Jaffe D, Sougnez C, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31(3):213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerji S, Cibulskis K, Rangel-Escareno C, Brown KK, Carter SL, Frederick AM, et al. Sequence analysis of mutations and translocations across breast cancer subtypes. Nature 2012;486(7403):405–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38(16):e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLaren W, Gil L, Hunt SE, Riat HS, Ritchie GR, Thormann A, et al. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol 2016;17(1):122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 2019;37(8):907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol 2015;33(3):290–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 2011;29(1):24–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kryukov GV, Wilson FH, Ruth JR, Paulk J, Tsherniak A, Marlow SE, et al. MTAP deletion confers enhanced dependency on the PRMT5 arginine methyltransferase in cancer cells. Science 2016;351(6278):1214–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown CN, Atwood DJ, Pokhrel D, Ravichandran K, Holditch SJ, Saxena S, et al. The effect of MEK1/2 inhibitors on cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) and cancer growth in mice. Cell Signal 2020;71:109605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2012;2(5):401–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, Syed A, Middha S, Kim HR, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med 2017;23(6):703–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernández-Medarde A, Santos E. The RasGrf family of mammalian guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1815(2):170–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cen H, Papageorge AG, Vass WC, Zhang KE, Lowy DR. Regulated and constitutive activity by CDC25Mm (GRF), a Ras-specific exchange factor. Mol Cell Biol 1993;13(12):7718–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Oksvold P, Kampf C, Djureinovic D, Odeberg J, et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 2014;13(2):397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghandi M, Huang FW, Jané-Valbuena J, Kryukov GV, Lo CC, McDonald ER 3rd, et al. Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature 2019;569(7757):503–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rückert F, Aust D, Böhme I, Werner K, Brandt A, Diamandis EP, et al. Five primary human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines established by the outgrowth method. J Surg Res 2012;172(1):29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu X, Wang Q, Tang M, Barthel F, Amin S, Yoshihara K, et al. TumorFusions: an integrative resource for cancer-associated transcript fusions. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46(D1):D1144–D9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei T, Lambert PF. Role of IQGAP1 in Carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(16). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang W, Soares J, Greninger P, Edelman EJ, Lightfoot H, Forbes S, et al. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41(Database issue):D955–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hillig RC, Sautier B, Schroeder J, Moosmayer D, Hilpmann A, Stegmann CM, et al. Discovery of potent SOS1 inhibitors that block RAS activation via disruption of the RAS-SOS1 interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116(7):2551–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofmann MH, Gmachl M, Ramharter J, Savarese F, Gerlach D, Marszalek JR, et al. BI-3406, a potent and selective SOS1::KRAS interaction inhibitor, is effective in KRAS-driven cancers through combined MEK inhibition. Cancer Discov 2020;11(1):142–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper AJ, Kobayashi Y, Kim D, Clifford SE, Kravets S, Dahlberg SE, et al. Identification of a RAS-activating TMEM87A-RASGRF1 Fusion in an Exceptional Responder to Sunitinib with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26(15):4072–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buscail L, Bournet B, Cordelier P. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;17(3):153–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heining C, Horak P, Uhrig S, Codo PL, Klink B, Hutter B, et al. NRG1 Fusions in KRAS Wild-Type Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov 2018;8(9):1087–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones MR, Williamson LM, Topham JT, Lee MKC, Goytain A, Ho J, et al. NRG1 Gene Fusions Are Recurrent, Clinically Actionable Gene Rearrangements in KRAS Wild-Type Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25(15):4674–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aguirre AJ, Nowak JA, Camarda ND, Moffitt RA, Ghazani AA, Hazar-Rethinam M, et al. Real-time Genomic Characterization of Advanced Pancreatic Cancer to Enable Precision Medicine. Cancer Discov 2018;8(9):1096–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watts JM, Perez A, Pereira L, Fan YS, Brown G, Vega F, et al. A Case of AML Characterized by a Novel t(4;15)(q31;q22) Translocation That Confers a Growth-Stimulatory Response to Retinoid-Based Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goto K, Pissaloux D, Fraitag S, Amini M, Vaucher R, Tirode F, et al. RASGRF1-rearranged Cutaneous Melanocytic Neoplasms With Spitzoid Cytomorphology: A Clinicopathologic and Genetic Study of 3 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quilliam LA, Huff SY, Rabun KM, Wei W, Park W, Broek D, et al. Membrane-targeting potentiates guanine nucleotide exchange factor CDC25 and SOS1 activation of Ras transforming activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91(18):8512–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiu VK, Bivona T, Hach A, Sajous JB, Silletti J, Wiener H, et al. Ras signalling on the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi. Nat Cell Biol 2002;4(5):343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arozarena I, Matallanas D, Berciano MT, Sanz-Moreno V, Calvo F, Muñoz MT, et al. Activation of H-Ras in the endoplasmic reticulum by the RasGRF family guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24(4):1516–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones MK, Jackson JH. Ras-GRF activates Ha-Ras, but not N-Ras or K-Ras 4B, protein in vivo. J Biol Chem 1998;273(3):1782–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrero A, Reis-Cardoso M, Jiménez-Gómez I, Doherty C, Agudo-Ibañez L, Pinto A, et al. Characterisation of HRas local signal transduction networks using engineered site-specific exchange factors. Small GTPases 2020;11(5):371–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cai D, Choi PS, Gelbard M, Meyerson M. Identification and Characterization of Oncogenic SOS1 Mutations in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Res 2019;17(4):1002–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Houlier A, Pissaloux D, Tirode F, Lopez Ramirez N, Plaschka M, Caramel J, et al. RASGRF2 gene fusions identified in a variety of melanocytic lesions with distinct morphological features. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2021;34(6):1074–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data has been deposited to dbGaP (study accession phs002556.v1.p1) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap.