Abstract

The Fisher hypothesis suggests a one-to-one link between nominal interest rate and expected inflation. The indication is that interest rate is independent of expected inflation. This paper empirically examines the Fisher effect in Rwanda using data from 2012m5 to 2020m2. We employ the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) technique for data analysis. We find evidence of partial Fisher effect in Rwanda during the period. This indicates that changes in expected inflation are not fully absorbed in the nominal interest rate which suggests that bank deposits decline over time. Also, the findings suggest that monetary policy may not be efficient in such a circumstance and household’s savings rate may suffer a decrease. Besides, the short-run results show no Fisher effect between nominal interest rate and expected inflation. This calls for great attention while fixing interest rate as a tool for monetary policy.

Keywords: Interest rate, Inflation, Fisher hypothesis, Rwanda

Introduction

The relationship between interest rate and inflation has attracted considerable attention in the economics literature. The link between the two variables is known as the “Fisher hypothesis” and was first developed by Fisher (1980). According to this hypothesis, nominal interest rates have two components: real interest rate and the [expected] rate of inflation. Fisher suggests that a change in the expected inflation does not affect the real interest rate, for it induces the same change in the nominal interest rate in the long run. This implies a one-to-one link between the two macroeconomic variables. In the literature, the Fisher effect has shown important implications for the role of interest rates in the performance of financial markets (Coppock and Poitras 2000). Moreover, real interest rate has been identified as the main determinant of savings and investment activities for both households and businesses. It, therefore, plays an important role in the economic growth and development process of countries (Deutsche Bundesbank 2001).

However, the Fisher effect has been criticized for the lack of an adequate method of inflationary expectations measurement (Cooray 2003). To that end, different approaches have been employed to measure inflationary expectations in the economy. One of these approaches is the use of distributed lag of past values of inflation rates (Fisher 1930). The approach has also been used widely in subsequent empirical studies (Cagan 1956; Meiselman 1962; Sargent 1969; Gibson 1970; Wesso 2000). Another approach is based on the rational expectation procedure by Muth (1961) and Fama’s (1982) efficient market hypothesis. The rational expectation procedure assumes that future inflation rate equals the expected rate of inflation, while efficient market hypothesis suggests that agents use all available information to predict inflationary expectations. Studies based on these approaches include Mishkin (1992), Paleologos and Georgantelis (1996), Awomuse and Alimi (2012), Panopoulou and Pantelidis (2016) and Gylfason et al. (2016).

Despite a number of empirical studies supporting the Fisher effect, some issues warrant investigating the Fisher hypothesis. For example, there is a long-held view against the robustness of the hypothesis across periods and countries (see Fama 1975; Fama and Gibbons 1982; Mishkin 1984, 1988, 1992; Lee 2009; Ray (2012; Arisoy 2013; Caporale and Gil-Alaña 2019). Again, theoretical evidence indicates the existence of partial adjustment between nominal interest rate and inflation, rejecting the one-to-one relationship between the two variables (see Mundell 1963; Tobin 1965; Darby 1975; Feldstein 1980). These theoretical studies on partial adjustment have been justified by other empirical studies (see Mishkin 1984; Peláez 1995). Another issue relates to the problems associated with the econometric techniques used in establishing the Fisher effect (Nelson and Plosser 1982).

We test the Fisher hypothesis for Rwanda. The motivation is that the National Bank of Rwanda (NBR), the central bank, seeks to achieve price stability while maintaining macroeconomic stability (NBR 2020). One of the main drivers of both price and macroeconomic stability is the interest rate (Blot et al. 2015). In view of this, NBR’s monetary policy should take note of the linkages between interest rate and expected inflation. According to the Fisher effect, movements in short-term interest rates would show changes in the expected rate of inflation. This means that these movements would have forecasting power for future inflation. Thus, an increase in short-term nominal interest rate may reflect an increased expected inflation. Therefore, examining the Fisher hypothesis would nudge policymakers to take caution before using nominal interest rate as a tool for monetary policy stance. Importantly, the relevance of the current study for monetary policy authorities in Rwanda is immense, given that the country’s central bank has, since 2019, shifted from the targeting of monetary aggregates to the use of interest rate for the purposes of achieving price stability objective. This follows the break in the paths of inflation and monetary aggregates in the wake of transformation of the Rwandan financial sector and the growing innovation in the country’s financial system. With the transition to the use of interest rate, understanding the nature of the relationship between interest rate and inflation therefore carries substantial policy relevance for Rwanda and many African economies which prioritize price stability as the primary objective of their central banks.

Section 2 reviews some empirical literature on the Fisher effect. Section 3 provides our methodological approach, while Sect. 4 presents and discusses the results. Section 5 concludes the study with some policy recommendations.

The economy of Rwanda

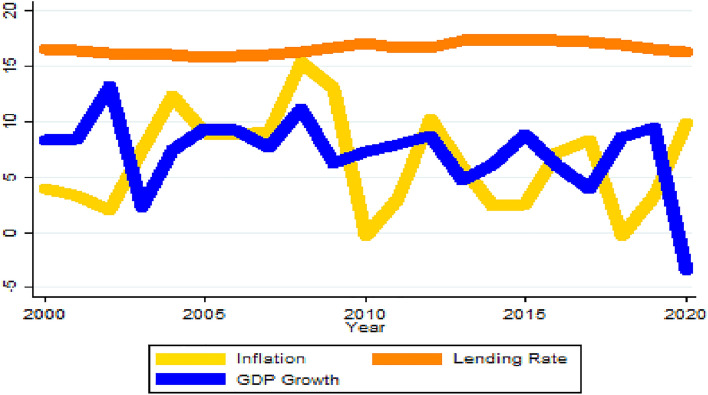

The Rwandan economy, in the last decade (2011–2020), has witnessed significant swings in growth performance, with the economy growing by as much as 9.5% in 2019 (on the back of strong service sector value addition) and shrinking by 3.36% in 2020 following the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. From a growth rate of 8.6% in 2012, the Rwandan economy experienced subdued growth rate in 2013, with growth rate declining by almost half to 4.7% following harsh weather conditions which hampered agricultural sector growth as well as uncertainties in inflows from donors. Growth rebounded in 2014 (6.2%) and even stronger in 2015 (8.9%). In 2016 and 2017, however, economic growth softened, with the economy growing by 5.97% and 3.98% respectively as unfavourable weather conditions affected the agricultural sector at a time when the industrial sector was also registering poor performance. The economy rebounded strongly in 2018 and 2019 to grow by 8.6 and 9.5% respectively as service sector led the way. Overall, the economy of Rwanda grew by 6.1% on the average in the course of the decade, down from an average of 8.2% (Fig. 1) in the prior decade (2001–2010).

Fig. 1.

Inflation, nominal interest rate and GDP growth (2000–2020). Source: Compiled from WDI (2022)

The country’s inflation trajectory, similar to output growth, has been erratic in the last decade (2011–2020), ranging from a minimum of −0.31% in 2018 to a maximum of 10.3% in 2012. Inflation more than tripled in 2012 to 10.3% from 3.1% in 2011, driven chiefly by food prices and depreciation of the domestic currency. Thereafter, inflation dropped consistently to reach 2.53% in 2015 on the back of declining food prices boosted by favourable weather conditions. Following stark food shortages in 2016 and 2017 on the back of unfavourable weather conditions, food prices rose significantly and caused overall inflation to quadruple by 2017 to reach 8.3%. The trend reversed in 2018, with food prices, housing and transport inflation falling. The combined effect of the declines in food prices, housing and transport prices meant greater overall disinflation, with inflation dropping to −0.31% in 2018.

The nominal interest rate (lending rate) has also seen some fluctuations over the last decade, although within a relatively small band of up to 2%. Nominal interest rate rose in 2012 and 2013 to 16.7 and 17.3% respectively from 16.67% in 2011 as a result increasing interest rate paid on deposits by the banks due to competition for deposits amongst these banks. Nominal interest rate remained fairly stable after 2013 up to 2017 with minimal fluctuations. In 2018 and thereafter, nominal interest rates took a downward turn in line with expansionary monetary policy which saw policy rate cut by the central bank.

Over the last decade, the Rwandan franc has seen consistent depreciation against the United States dollar, moving from 600 franc to a dollar in 2011 to 943.3 franc to a dollar in 2020, representing 57.1% depreciation over the period (Fig. 2). A key factor driving the depreciation of the country’s currency has been the increasing import demand, requiring incessant demand for foreign currencies over the years. Declining and uncertain inflows from donors has also engendered foreign currency shortage and occasioned depreciation of the country’s currency. Falling prices of commodities on the international market partly caused the exchange rate depreciation in 2016 and 2017 in particular.

Fig. 2.

Exchange rate of the Rwandan franc to the US dollar (2000–2020). Source: Compiled from WDI (2022)

Empirical literature

Extensive empirical studies conducted to test the validity of the Fisher effect have provided mixed results and conclusions. Various reasons including the study period, econometric methods for analysis and country-specific factors may account for mixed and/or unconvincing results.

Mishkin (1992) re-examined the link between interest rate and inflation for the US, using data from 1953m1 to 1990m12. The results support Fisher’s findings. Interestingly, he finds that the Fisher effect did not hold for the periods between 1979m10 and 1982m9. Fahmy and Kandil (2003) found a similar result for USA. In many of the European economies, the Fisherian relationship has been well documented. For instance, earlier studies on UK have supported the validity of the Fisher effect (Woodward 1992; Granville and Mallick 2004). In Turkey, extant studies have reported the existence of the Fisher effect (Zortuk 2008; Incekara et al. 2012; Güriş et al. 2016). An earlier study by Paleologos and Georgantelis (1996) found that the Fisher effect did not hold in Greece for the period 1980:I–1996:II. In Australia, using Monte Carlo methods, Mishkin and Simone (1995) investigated the Fisher effect. Their findings show that the Fisher effect holds in the long run, but not in the short run.

Empirical studies conducted on Asia are vast. In the context of the Indian economy, studies like Paul (1984) and Sathye et al. (2009) have investigated the existence of Fisher effect. The conclusions from these studies significantly support the Fisher hypothesis in the long run as well as in the short run. Contrary to these findings, Abubakar and Sivagnanam’s (2017) study on India rejected it. In Singapore, Lee (2009) examined the validity of the Fisher hypothesis for the period 1976–2006. He employed Johansen cointegration and error correction techniques. The results indicate the existence of a long-run partial Fisher effect and a strong relationship between the two variables in the short run was found.

Using signal extraction, Garcia (1993) studied the Fisher effect for Brazil using annual data from 1973 to 1990. The findings show that the Fisher effect holds in the Brazilian economy. A similar investigation by Thornton (1996) indicates that the Treasury bill interest–inflation relationship in the Mexican economy validates the Fisher hypothesis. Several studies on the theme exist for African economies. Etuk et al. (2014) and Inam (2014) analysed the link between interest rate and inflation and reported that the long-run Fisher effect holds in the Nigerian economy. Earlier, Awomuse and Alimi (2012) examined the existence of the Fisher effect in the Nigerian economy and found support for the Fisher effect, but not the one-to-one relationship reported by Irving Fisher. On the contrary, some studies reject the long–run Fisher effect in favour of the short-run Fisher effect for Nigeria (Ogbonna 2013; Balparda et al. 2017).

The Fisher effect has also been studied in panel and cross-sectional analytical framework. For example, Phylaktis and Blake (1993) examine the Fisherian relation for 3 high inflation economies (Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico). They found that the full Fisher hypothesis is validated for all the three countries. In OECD economies, Panopoulou and Pantelidis (2016) employed time-varying coefficient and cointegration analyses to examine the Fisher effect for 19 countries. Their findings show that the full Fisher effect is supported by all countries in the sample except Ireland and Switzerland. With respect to the African economies, Yaya (2015) employed the ARDL bounds test cointegration technique to examine the validity of the Fisher effect for 10 African countries. He reported that the full Fisher effect holds for Kenya, while Cote d’Ivoire and Gabon have the partial Fisher effect. The findings did not show any evidence of long-run relationship between interest rate and inflation for the other seven countries within the sample. Additionally, a study by Gylfason et al. (2016) rejects the one-to-one link between the two variables for six cities namely New York, London, Tokyo, Paris, Berlin, and Calcutta. The reasons given for this result are that nominal interest rate grows less rapidly than inflation and changes less than inflation. Therefore, the one-to-one link between the two variables may not be achieved. Phiri and Said (2001) also investigated the Fisherian link for 5 Asian countries using a panel data spanning 1986–1996. They employed Engle–Granger cointegration and found that the Fisher effect holds only for Indonesia, while results for Malaysia, Thailand, South Korea, and Philippines did not support the Fisher effect.

The existing literature on the theme provides mixed findings. While some support the Fisher effect, others do not. The hypothesis has been tested for many countries and regions. However, to our knowledge, no study exists for Rwanda. In this respect, we fill this gap in the literature and provide information to aid monetary policymaking.

Methodology

The model

For the Fisher effect, nominal interest rate has two components: real interest rate and inflation expectation. Its mathematical expression is given as:

| 1 |

Calculating it:

| 2 |

Assuming that is small, the above equation can be written as follows:

| 3 |

where represents nominal interest rate, stands for real interest rate, while is the expected inflation. In the case where money illusion does not hold, changes in inflation expectation should be fully reflected in the nominal interest rate. Thus, is assumed constant in the long run. Then the operational model for the Fisher effect testing is given as:

| 4 |

where β0 represents real interest rate (assumed constant) and β1 is the long–run Fisher effect of πet, while ut is the error term. If there is full Fisher effect, β1 is supposed to be one, which is labeled as full fisher effect by Mishkin (1992), and Mishkin et al. (1995), whereas a value of β1 less than one would indicate a weak or partial form of the Fisher effect.

Variables, measurement, and data sources

To achieve the aim of this paper, monthly time series data were sourced from the National Bank of Rwanda (NBR 2020). The data cover 2012m5 to 2020m2 for expected inflation (π) and nominal interest rates (i). The inflation data are based on the expected inflation, while the nominal interest rates data are proxied by the bank lending rate. Inflation expectation is generated using a moving average of 2 lags, 2 leads and the current period. To deal with possible skewedness in the data and engender normality, the data has been log transformed. The log transformation also helps to interpret the coefficients as elasticities.

Figure 3 presents the plots of nominal interest rate and expected inflation over the period under study, whereas Table 1 displays the summary statistics of the variables. For the period under study, both nominal interest rate and expected inflation are positive. Their averages are 17 and 3.6% respectively.

Fig. 3.

Interest rate and Expected Inflation from 2012m5 to 2020m2. Source: Compiled from NBR (2020)

Table 1.

Summary statistics

| Variable | Observation | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| it | 94 | 17.095 | 0.390 | 16.020 | 17.850 |

| πet | 94 | 3.579 | 2.138 | 0.480 | 8.020 |

Source: Author’s compilation

Methods of analysis

Unit root test

Generally, macroeconomic variables tend to be non-stationary. Estimating a model with nonstationary variables may lead to spurious results. Thus, to deal with such problem, the unit root test is conducted (Gujarati 2004). To this end, Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) unit root test by Dickey and Fuller (1979, 1981a, b) was employed to examine the order of integration. The advantage of this test is that the ADF remedies serial correlation in error terms through an autoregressive parametric approach. The ADF test is conducted using Eqs. (5) and (6) respectively.

| 5 |

| 6 |

To allow for detection of possible breaks in the series, which is characteristic of many macroeconomic series such as inflation and interest rates, we resorted to the approach developed by Zivot and Andrews (1992) to test for unit root and ascertain whether structural breaks exist.

ARDL analysis

To examine whether the Fisher effect holds in Rwandan economy, we sought to investigate the connection between nominal interest and expected inflation rates. In this regard, we employ the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) method proposed by Pesaran et al. (2001). The ARDL technique is chosen due to its several advantages. First, it accommodates variables with I(1) and I(0) order of integration. Secondly, ARDL gives robust estimates in finite samples and addresses endogeneity or simultaneity issues (Pesaran et al. 2001; Haug 2002; Sakyi et al. 2016; Boachie 2017; Boachie et al. 2020). Simultaneity is expected because changes in expected inflation causes economic agents to demand higher interest rates to compensate for the loss in purchasing power of the currency. Changes in nominal interest rate may also cause changes in expected inflation. The reason is that when the central bank increases interest rates in response to expected inflation for instance, it sends a signal to the market of the central bank’s resolve to tame future inflation which then feeds into the expectation formation of economic agents in respect of the path of future inflation. For central banks with impeccable credibility, economic agents would expect a tamed inflation with such monetary policy stance. The ARDL approach resolves the joint causation issues to allow us to examine the link between expected inflation and nominal interest rates. From Eq. 4, we can write the unrestricted error correction model (ECM) and ARDL as follows:

| 7 |

where α0 is a constant, ∆ represents the first difference operator, ɛ is the error term, λs indicate long-run relationship coefficients, φ and ϕ indicate short-run coefficients. Wald test (F-statistics) was used to test the existence of long-run relationship between the two variables. The computed F-statistics are compared to the critical value generated by Pesaran et al. (2001). This comparison follows two assumptions: first, the series integrated of order zero, I(0) represents the lower bound critical values, while the series integrated of order one, I(1) refers to the upper bound critical values. The null hypothesis of no cointegration is not rejected if computed F-statistic is below the lower bound value, I(0). In contrast, the variables considered in the study are cointegrated if computed F-statistic is greater than the upper bound value, I(1). The test is inconclusive if computed F-statistic falls within the two bounds.

Following cointegration test, we proceed with both long-run relationship and short-run error correction estimation; the long-run and short-run models are given in Eqs. (8) and (9) respectively:

| 8 |

| 9 |

where represents the coefficient of the error correction model (ECTt − 1). It measures the speed of adjustment towards long-run equilibrium following a shock to the system.

Results and discussion

Results from unit root test

Table 2 reports the results of the ADF unit root tests.

Table 2.

Unit root test results

| Variable | Level | First difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | Trend | Constant | Trend | |

| lnit | −2.637* | −2.971 | −4.573*** | −4.709*** |

| lnπet | −3.0923** | −2.953 | −3.228** | −3.937** |

Source: Author’s compilation

*,**,***Denote significance at 10, 5, and 1% levels

The test results show that both nominal interest rate and expected inflation are not stationary at levels. However, after the first differencing all of them become stationary. Thus, the two variables are integrated of order one, I(1); there is no I(2) variable. This permits us to examine the long-run relationship between nominal interest rate and inflation using the ARDL procedure.

The results of the Zivot-Andrews test, presented in Table 3, confirm that both nominal interest rate and expected inflation are non-stationary at the levels as the minimum t-statistics for both series fall below the respective critical values at 1, 5 and 10%.

Table 3.

Test for structural breaks

| Variable | Minimum t-statistic | Critical values | Break point | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 5% | 10% | |||

| lnit | −4.247 | −5.57 | −5.08 | −4.82 | 2013 m8 |

| lnπet | −2.803 | −5.57 | −5.08 | −4.82 | 2018 m9 |

m Month

For the nominal interest rate, the break point occurred in the eighth month of the year 2013 whiles that of the expected inflation occurred in the ninth month of 2018. To account for these breaks, we introduced dummy variables for both nominal interest rates and expected inflation with the identified break point dates designated as 1 and 0 for all other periods. We first estimated our baseline model without the dummies. We then expanded the baseline model to include the dummies. The results of the expanded model (including the dummies) are shown in the Appendix (from Tables 8, 9 and 10). The coefficients of the dummy variables are statistically insignificant, implying that the breaks in the series did not materially affect the relationship between the variables of interest (nominal interest rates and inflation). As a consequence, we focus the analysis on the baseline model (without the dummies) for the rest of the sections.

Table 8.

ARDL bounds test results

| Model | F-Statistic | K | Critical values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | I(0) | I(1) | |||

| 7.10 | 3 | 10 | 2.72 | 3.77 | |

| 5 | 3.23 | 4.35 | |||

| 1 | 4.29 | 5.61 | |||

K denotes the number of regressors

Table 9.

ARDL long run results based on ARDL (1, 2, 2, 2)

| Predictor | Coefficient | SE |

|---|---|---|

| πe | 0.0103* | 0.006 |

| DMLR | 0.079 | 0.067 |

| DMI | 0.006 | 0.076 |

Source: Author’s compilation

**,***Indicate significance at 5 and 1% levels, respectively. DMLR denotes dummy variable for the break in nominal interest rate. DMI denotes dummy variable for the break in expected inflation

Table 10.

Error correction model (ECM) based on ARDL (1, 2, 2, 2)

| Predictor | Coefficient | SE |

|---|---|---|

| ∆πe | 0.0080 | 0.0172 |

| ECM(-1) | −0.521*** | 0.101 |

Source: Author’s compilation

***Indicate significance at 1% level

Cointegration test, long-, and short-run coefficients

We apply the bounds test approach to cointegration to test the existence of long-run equilibrium relationship between nominal interest rate and expected inflation. Summarised in Table 4 are the bounds test results. The null hypothesis is that there is no long-run equilibrium relationship between nominal interest rate and expected inflation. If the estimated F-statistic is below the lower critical values (bounds) at 1, 5 and 10% significance levels, then we cannot reject the null hypothesis. If the estimated F-statistic is above the upper critical values (bounds) at 1, 5 and 10% significant levels, then the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating that nominal interest rate and expected inflation have a long-run equilibrium relationship or there is cointegration. Where the estimated F-statistic falls between the upper and lower bounds, then the results cannot be conclusive (Table 5).

Table 4.

ARDL bounds test results

| Model | F-Statistic | K | Critical values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | I(0) | I(1) | |||

| 4.89 | 1 | 10 | 3.02 | 3.51 | |

| 5 | 3.62 | 4.16 | |||

| 1 | 4.94 | 5.58 | |||

Source: Author’s compilation

K denotes the number of regressors

Table 5.

ARDL long run results based on ARDL (2, 3)

| Predictor | Coefficient | SE |

|---|---|---|

| πe | 0.0168** | 0.0083 |

| C | 2.8236*** | 0.0097 |

Source: Author’s compilation

**,***Indicate significance at 5 and 1%levels, respectively

From the results presented in Table 4, there is a cointegration relation between nominal interest rate and expected inflation; the computed F-Statistic (4.89) is greater than the upper bound value (4.16) at 5% significance level. Having established long-run equilibrium association between the two variables, we estimate the long-run coefficients. Presented in Table 5 are the ARDL long-run coefficients.

In respect of the long run, the elasticity of expected inflation is 0.0168 and is statistically significant at 5% level. This implies that an increase in expected inflation rate by 1% increases the nominal interest rate by 0.0168% in the long run. This result indicates that changes in expected inflation are not fully absorbed in the nominal interest rate. That is, the full Fisher effect is not supported in the Rwandan economy. The results show the existence of the partial Fisher effect. The findings support those reported, for example, by Huizinga and Mishkin (1986), Kandel et al. (1996), Lee (2009), Awomuse and Alimi (2012), and Yaya (2015), while deviating from those of Panopoulou and Pantelidis (2016) for Ireland and for Switzerland (Paleologos and Georgantelis 1996). Similar findings have been reported for Malaysia, Thailand, South Korea, Philippines, and India as well (Phiri and Said 2001; Abubakar and Sivagnanam 2017).

This partial Fisher hypothesis implies that changes in expected inflation are not fully absorbed in the nominal interest rate, which suggests that the value of bank deposits decline over time. As a result, investors would look for alternatives such as real estate and foreign currency to hedge against inflation. Theoretically, this result validates the Mundell-Tobin wealth effect (Tobin 1965; Mundell 1963, 1965) which stipulates that nominal interest rate would increase by less than one-for-one relative to expected inflation. The idea is that, because inflation erodes or penalises money balances, economic agents would necessarily reduce holdings of money balances in favour of other assets. As a consequence, real interest rates tumble, making any increase in nominal interest rate falling short of one-for-one with expected inflation (Woodward 1992).

The short–run results in Table 6 show that the coefficient of inflation (0.0056) is positive and statistically insignificant at 5% level. The coefficient implies that 1% increase in expected inflation increases nominal interest rate by 0.0056% in the short run. Thus, the findings support Fisher’s (1980) idea of no strong short-run association between interest rate and expected inflation. While the short-run results on Fisher effect agrees with previous studies such as Paul (1984), Mishkin and Simone (1995), and Sathye et al. (2009), they are not in tandem with those reported by Lee (2009), Ogbonna (2013), and Balparda et al. (2017).

Table 6.

Error correction model (ECM) based on ARDL (2, 3)

| Predictor | Coefficient | SE |

|---|---|---|

| ∆πe | 0.0056 | 0.0980 |

| ECM(−1) | −0.3725*** | 0.0961 |

Source: Author’s compilation

***Indicate significance at 1% level

This short-run result suggest that changes in the short-term nominal interest rate for the Rwandan economy indicates the stance of monetary policy instead of variation in the expected inflation as recommended by Fisher (1980). The reason is that short-term interest rate is decided by monetary authorities and not expectation formed by economic agents (Mishkin and Simone 1995). This indicates a positive progress for NBR monetary authorities. This is because nominal short-term interest rates are considered as a poor indicator of the stance of monetary policy in case Fisher effect holds (see Mishkin and Simon 1995).

Finally, the results show that the error correction term has expected and correct sign. The coefficient on ECM (i.e., adjustment term) equals –0.3725 and statistically significant at 1% level. This provides further evidence on the existence of stable cointegration relationship between nominal interest rate and inflation expectation in Rwanda. In particular, the ECM coefficient of 0.3725 implies that about 37% of the disequilibrium due to a shocks is rectified within a year. The coefficient also suggests that nominal interest rate eliminates about 37% of the previous period’s disequilibrium in the current period.

The diagnostics of the model are satisfactory (Table 7). The statistics show no signs of serial correlation, heteroscedasticity and parameter instability. Thus, to some extent, our ARDL estimates are satisfactory. Moreover, both “CUSUM (Fig. 4) and CUSUMQ (Fig. 5)” of the residuals revealed that the model is well fitted. That is, the two graphs are cramped within the 5% critical bounds of parameter stability.

Table 7.

The diagnostic statistics tests

| Autocorrelationa | Heteroscedasticityb | Normalityc |

|---|---|---|

| 0.8998 | 0.8160 | 1.2393 |

| [0.4106] | [0.5605] | [0.5381] |

Source: Author’s compilation

The above tests are based on: aBreusch-Godfrey LM; bBreusch-Pagan; cJarque-Bera

Probabilities in []

Fig. 4.

CUSUM results for Fisher model. Source: Author’s compilation

Fig. 5.

CUSUMQ results for Fisher model. Source: Author’s compilation

Conclusion

This paper examined the existence of Fisher effect in Rwandan economy using monthly time series data from 2012m5 to 2020m2. We adopted the ARDL approach to estimate the Fisher model and found that long-term nominal interest rates moved in the same direction with inflation expectations of the public for the period. However, the full Fisher effect does not hold for Rwandan economy; partial Fisher effect exists. This partial Fisher hypothesis implies that changes in expected inflation are not fully absorbed in the long-term nominal interest rate, which suggests that the value of bank deposits decline over time. Also, the findings suggest that monetary policy may not be effective in such a circumstance and household’s saving rate may suffer a decrease.

The results further show that no Fisher effect exist in the short run for Rwanda. In fact, for conventional central banking, monetary transmission mechanism depends on the fact that the fisher effect is missing in the short run. The implication is that short-term interest rates reflect changes in monetary policy rather than in the expected inflation in the short run. The reason is that short-term interest rate is decided by NBR monetary authorities not expectations formed by economic agents. Besides, this transmission mechanism investigation indicates that the NBR is effective when it uses its control over nominal interest rate to influence expected inflation. The implication is that, the Fisherian theory of interest suggests that, short-term nominal interest rates are not long-run predictors of inflation. This study evidently indicates that during the period interest rate failed to perform as a forecaster of inflation. Great attention should be taken while fixing interest rate as a tool for communicating monetary policy stance.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the valuable suggestions from Dr. Kigabo Thomas and other participants at the 4th Annual Eastern Africa Business and Economic Watch International Conference (June 12–14, 2019): College of Business and Economics, University of Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda.

Appendix

Authors’ Contributions

All authors have contributed equally.

Funding

No funding to declare.

Availability of data and material

Data used in this paper are available on the National Bank of Rwanda website (NBR).

Declaration

Conflict of interest

The authors declare to have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abubakar J, Sivagnanam KJ. Fisher’s effect: An empirical examination using India’s time series data. Quant. Econ. J. 2017;15(3):611–628. doi: 10.1007/s40953-016-0065-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arısoy I. Testing for the fisher hypothesis under regime shifts in Turkey: New evidence from time-varying parameters. Int. J. Econ. Finance. 2013;3(2):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Awomuse, B., Alimi, S.: The relationship between nominal interest rates and inflation: new evidence and implications for Nigeria. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 3(9),158–165 (2012) http://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEDS/article/view/2563

- Boachie, M. K., Ruzima, M., and Immurana, M.: The concurrent effect of financial development and trade openness on private investment in India. South Asian J. Macro. P. Finance, 1–31 (2020) . 10.1177/2277978720906049

- Balparda B, Caporale GM, Gil-Alana LA. The fisher relationship in Nigeria. J. Econ. Fin. 2017;41(2):343–353. doi: 10.1007/s12197-016-9355-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blot C, Creel J, Hubert P, Labondance F, Saraceno F. Assessing the link between price and financial stability. J. Econ. Finance. 2015;16:71–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jfs.2014.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boachie MK. Health and economic growth in Ghana: an empirical investigation. Fudan J. Human Soc. Sci. 2017;10(2):253–265. doi: 10.1007/s40647-016-0159-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cagan, P.: The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation. In M. Friedman (ed.), Studies in the quantity theory of money, University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1956)

- Caporale GM, Gil-Alaña L. Testing the Fisher hypothesis in the G-7 countries using I(d) techniques. Int. Econ. 2019;159:140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.inteco.2019.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooray A. The fisher effect: A survey. Sing. Econ. Rev. 2003;48(2):135–150. doi: 10.1142/S0217590803000682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coppock L, Poitras M. Evaluating the Fisher effect in long-term cross-country averages. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 2000;9(2):181–192. doi: 10.1016/S1059-0560(99)00057-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darby, M. R.: The financial and tax effects of monetary policy on interest rates. Econ. Inquiry, 13(2), 266–276 (1975) . 10.1111/j.1465-7295.1975.tb00993.x

- Deutsche Bundesbank: Real Interest Rates: Movement and Determinants. Monthly Report: 31–47 (2001)

- Dickey DA, Fuller WA. Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979;74(366):427–431. doi: 10.2307/2286348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey DA, Fuller WA. Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econom. 1981;49(4):1057–1072. doi: 10.2307/1912517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey DA, Fuller WA. Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econometrica. 1981;49(4):1057–1072. doi: 10.2307/1912517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etuk IE, James TO, Asare BK. Fractional cointegration analysis of Fisher hypothesis in Nigeria. Asian J. Appl. Sc. 2014;2(1):88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy YAF, Kandil M. The Fisher effect: New evidence and implications. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 2003;12(4):451–465. doi: 10.1016/S1059-0560(02)00146-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fama EF. Short-term interest of rates inflation as predictors. Am. Econ. Rev. 1975;65(3):269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Fama EF, Gibbons MR. Inflation, real returns and capital investment. J. Mon. Econ. 1982;9(3):297–323. doi: 10.1016/0304-3932(82)90021-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein, M.: Tax rules and the mismanagement of monetary policy. Am. Econ. Rev. 70(2),182–209 (1980) https://www.jstor.org/stable/1815463

- Fisher I. The theory of interest. New York: Macmillan; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MGP. The Fisher effect in a signal extraction framework The recent Brazilian experience. J. Dev. Econ. 1993;41(1):71–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-3878(93)90037-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson WE. Price-expectations effects on interest rates. J. Fin. 1970;25(1):19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.1970.tb00410.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granville B, Mallick S. Fisher hypothesis: UK evidence over a century. Appl. Econ. Let. 2004;11(2):87–90. doi: 10.1080/1350485042000200169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Güriş, S., Güriş, B., Ün, T.: Interest rates,fisher effect and economic development in Turkey,1989–2011. Rev.Galega Econ. 25(2), 95–100 (2016) . 10.15304/rge.25.2.3740

- Gylfason T, Tómasson H, Zoega G. Around the world with Irving Fisher. North Am. J. Econ. Finance. 2016;36:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.najef.2016.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga J, Mishkin FS. Monetary policy regime shifts and the unusual behavior of real interest rates. Carnegie-Rochester Conf. Ser. Public Policy. 1986;24:231–274. doi: 10.1016/0167-2231(86)90011-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inam US. Cointegration, causality and Fisher effect in Nigeria : An empirical analysis (1970–2011) Res. Human. Soc. Sc. 2014;4(24):98–107. [Google Scholar]

- İncekara A, Demez S, Ustaoğlu M. Validity of Fisher effect for Turkish economy: Cointegration analysis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012;58:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen S. Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. J. Econ. Dyn. Contr. 1988;12(2–3):231–254. doi: 10.1016/0165-1889(88)90041-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel S, Ofer AR, Sarig O. Real interest rates and inflation: An ex-ante empirical analysis. J. Financ. 1996;51(1):205–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.1996.tb05207.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KF. The Dynamic relation between nominal interest rate and inflation in Singapore. Sing. Econ. Rev. 2009;54(1):75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Meiselman, D.: The term structure of interest rate. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice–Hall Inc (1962)

- Mishkin, F. S.: Is the Fisher effect for real?. A reexamination of the relationship between inflation and interest rates. Journal of Monetary Economics, 30(2), 195–215 (1992) . 10.1016/0304-3932(92)90060-F

- Mishkin FS. Are real interest rates equal across countries? An Empirical investigation of international parity Conditions. J. Finance. 1984;39(5):1345–1357. doi: 10.2307/2327731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishkin FS. Understanding real interest rates: discussion. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1988;70(5):1076–1077. doi: 10.2307/1241739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mundell R. Inflation and real interest. J. Pol. Econ. 1963;71(3):280–283. doi: 10.1086/258771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mundell, R.: Growth, stability, and inflationary finance. J. Polit. Econ, 97–109 (1965)

- Muth JF. Rational expectations and the theory of price movements. Econometrica. 1961;29(3):315–335. doi: 10.2307/1909635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NBR.: Economic Statistics 2020. https://www.NBR.rw/browse-in/statistics/economic-statistics/. (Accessed March 29, 2020).

- NBR.: Monthly Interest Rates 2020. https://www.NBR.rw/browse-in/financial-market/money-market-interest-rates/monthly-interest-rates/. (Accessed March 29, 2020).

- NBR: Monetary Policy Framework 2020. https://www.NBR.rw/monetary-policy/. (Accessed July 25, 2020).

- Nelson, C. R., Plosser, C. R.: Trends and random walks in macroeconmic time series. Some evidence and implications. J. Mon. Econ. 10(2), 139–162 (1982) . 10.1016/0304-3932(82)90012-5

- Ogbonna BC. Testing for Fisher’s hypothesis in Nigeria (1970–2012) Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2013;4(16):163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Panopoulou E, Pantelidis T. The Fisher effect in the presence of time-varying coefficients. Comput. Stat. Data Analy. 2016;100:495–511. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2014.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul MT. Interest rates and the fisher effect in India. An empirical study. Econ Let. 1984;14(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/0165-1765(84)90022-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peláez RF. The Fisher effect: Reprise. J. Macro. 1995;17(2):33–346. doi: 10.1016/0164-0704(95)80105-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econ. 2001;16(3):289–326. doi: 10.1002/jae.616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phylaktis K, Blake D. The fisher hypothesis: Evidence from three high inflation economies. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv. 1993;129(3):591–599. doi: 10.1007/BF02708004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S. Empirical testing of International Fisher effect in United States and selected Asian economies. Adv. Inform. Tech. Man. 2012;2(1):216–228. [Google Scholar]

- Sakyi D, Kofi BM, Immurana M. Does financial development drive private investment in Ghana? Economies. 2016;4(4):1–12. doi: 10.3390/economies4040027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent TJ. Commodity price expectations and the interest rate. Q. J. Econ. 1969;83(1):127–140. doi: 10.2307/1883997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sathye M, Sharma D, Liu S. The Fisher effect in an emerging economy: The Case of India. Int. Bus. Res. 2009;1(2):99–104. doi: 10.5539/ibr.v1n2p99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton J. The adjustment of nominal interest rates in Mexico: A study of the fisher effect. Appl. Econ. Lett. 1996;3(4):255–257. doi: 10.1080/758520875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin J. Money and economic growth. Econometrica. 1965;33(4):671–684. doi: 10.2307/1910352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wesso, G. R.: Long-term bond yields and future inflation in South Africa : a vector error-correction analysis. Quarterly Bulletins, South Africa Researve Bank (2000).

- Woodward, G. T.: Evidence of the Fisher Effect From U.K. Indexed Bonds. The Rev. Econ. Stat. 74(2), 315–320 (1992). . 10.2307/2109663

- Yaya K. Testing the long-run Fisher effect in selected African Countries: Evidence from ARDL Bounds test. Int. J. Econ Finance. 2015;7(12):168–175. doi: 10.5539/ijef.v7n12p168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zivot E, Andrews D. Further evidence of great crash, the oil price shock and unit root hypothesis. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1992;10:251–270. [Google Scholar]

- Zortuk M. New Assessment on the Fisher hypothesis: the case of Turkey. Inv. Man. Financial Innov. 2008;5(3):134–138. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this paper are available on the National Bank of Rwanda website (NBR).