Abstract

The activity and community structure of methanotrophs in compartmented microcosms were investigated over the growth period of rice plants. In situ methane oxidation was important only during the vegetative growth phase of the plants and later became negligible. The in situ activity was not directly correlated with methanotrophic cell counts, which increased even after the decrease in in situ activity, possibly due to the presence of both vegetative cells and resting stages. By dividing the microcosms into two soil and two root compartments it was possible to locate methanotrophic growth and activity, which was greatest in the rhizoplane of the rice plants. Molecular analysis by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) with family-specific probes revealed the presence of both families of methanotrophs in soil and root compartments over the whole season. Changes in community structure were detected only for members of the Methylococcaceae and could be associated only with changes in the genus Methylobacter and not with changes in the dominance of different genera in the family Methylococcaceae. For the family Methylocystaceae stable communities in all compartments for the whole season were observed. FISH analysis revealed evidence of in situ dominance of the Methylocystaceae in all compartments. The numbers of Methylococcaceae cells were relatively high only in the rhizoplane, demonstrating the importance of rice roots for growth and maintenance of methanotrophic diversity in the soil.

Wetland rice fields are an important source of the greenhouse gas CH4. They contribute up to 20% (20 to 50 Tg year−1) of the global CH4 emissions (28, 34). It is thought that due to the demands of the growing human population, cultivation of wetland rice will increase during the next 3 decades by 60% (14). Therefore, a reduction in CH4 emission from this source due to microbial CH4 oxidation could play an increasingly important role in the global CH4 budget.

Methane-oxidizing bacteria (methanotrophs) oxidize CH4 with molecular O2 and use it as a carbon and energy source (11, 23). Methane is produced as an end product of anaerobic degradation of organic matter, whereas O2 in flooded rice fields occurs only at the soil-floodwater interface and, due to O2 leakage from the rice roots, in a thin soil layer around the roots (3). Methanotrophs have been detected in rice field soil and on rice roots (7, 9, 19, 43), but until now not much has been known about the population structure and dynamics of these microorganisms over the growth period of rice.

The Methanotrophs have been divided into two families: the Methylococcaceae, belonging to the γ subclass of the class Proteobacteria, and the Methylocystaceae, belonging to the α subclass of the Proteobacteria. The family Methylococcaceae includes the genera Methylobacter, Methylomonas, Methylomicrobium, Methylococcus, Methylocaldum, and Methylosphaera, and the family Methylocystaceae includes the genera Methylosinus and Methylocystis (11). Physiological differences between the two families are correlated with different ecological preferences. Graham et al. (21), for example, have shown that Methylosinus trichosporium outcompetes Methylomonas albus in chemostat cultures under N-limiting conditions. Amaral and Knowles (2) found that in CH4-O2 countergradients members of the Methylococcaceae grow preferentially at low CH4 concentrations and members of the Methylocystaceae grow preferentially at high CH4 concentrations. In the complex rice field ecosystem temporal and spatial changes in the microbial environment occur and might result in shifts in the methanotrophic community, which could influence overall CH4 oxidation activity. A better understanding of the methanotrophic community structure in rice fields is therefore important to understand this dynamic ecosystem. It could also facilitate future attempts to activate or affect CH4 oxidation in this or other systems with the aim of reducing CH4 emission. A combination of process measurements and molecular community analysis was used in this study to compare community structure and actual activity of methanotrophs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compartmented microcosms.

The microcosm system used in this study was kindly provided by P. Bodelier (Netherlands Institute of Ecology, Centre for Limnology, Maarssen, The Netherlands) and has been described previously (6). In short, microcosms were built of stainless steel cylinders (height, 12 cm; diameter, 9 cm). In the center of each microcosm, the root compartment was separated by a perforated stainless steel cylinder (diameter, 4 cm; hole diameter, 1 mm) that was covered with two layers of nylon gauze (mesh size, 0.45 μm). In each compartment, one porewater sampler was installed vertically from below. Each porewater sampler consisted of a hydrophilic porous membrane (pore diameter, 0.1 μm) fitted to a steel needle and connected with plastic tubing for sampling. Porewater samples were taken weekly by using evacuated vacuum tubes. The sampling procedure and porewater analysis method used have been described previously (30).

Soil.

Rice field soil was taken after plowing from an Italian rice field in spring 1998 (Istituto Sperimentale per la Cerealicoltura, Vercelli, Italy). This site has been used repeatedly to study the microbial ecology of rice fields (30). The soil is a sandy loam (Cambisol), and it was dried at room temperature, ground with a jaw crusher, and sieved (hole size, ≤2 mm) before it was used in the microcosms. Each bulk soil compartment was filled with 495 g (dry weight) of soil, and each root compartment was filled with 105 g (dry weight). The microcosms were flooded with demineralized water and incubated at 25°C for 10 days before rice seedlings were transplanted.

Rice plants and growth conditions.

Rice seeds (Oryza sativa type japonica variety KORAL) were germinated at 25°C for 12 days before transplanting. Planted microcosms were incubated in a growth chamber with 12-h days and 12-h nights and a light intensity of 0.22 to 0.55 mmol m−2 s−1. The temperature was 25°C during the light phase and 20°C in the dark. The humidity was adjusted to 70%.

Fertilization.

Each of the microcosms was fertilized weekly with 2 ml of a fertilizer solution containing (per liter) 5.5 g of urea, 4.2 g of KH2PO4, and 3.4 g of KCl. The overall amount of fertilizer added during a 13-week growth period was the amount of fertilizer added to rice fields during rice growth, which was (per hectare) 160 kg of N, 140 kg of P2O5, and 155 kg of K2O2 in 1998 (30).

Flux measurements.

For CH4 flux measurement, the microcosms were covered with glass cylinders (volume, 2 liters). In the top of each glass cylinder a fan was installed to ensure complete mixture of the headspace. The increase in the CH4 concentration was monitored for 2 h by taking 1-ml gas samples (n = 18) through a butyl septum. The samples were analyzed with a gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector. The in situ CH4 oxidation activity was determined by comparing flux measurements before and after addition of difluoromethane (CH2F2), a specific inhibitor of methane oxidation (33). The inhibitor was injected into the gas phase (final concentration, 1% [vol/vol]) immediately after the microcosms were covered with the glass cylinders. Methane concentrations were monitored for 2 h as described above. After this the glass covers were removed, and the microcosms were allowed to equilibrate with the amibient air for approximately 1 h outside the growth chamber to remove the CH2F2. The in situ oxidation value was calculated from the difference between CH4 emission with the inhibitor and CH4 emission without the inhibitor. Methane flux was measured weekly in four parallel microcosms. In situ CH4 oxidation was determined every second week in an additional four microcosms of the same plant age in order to allow direct comparison of fluxes with and without inhibitor. The effect of the inhibitor was detectable within 20 to 40 min after it was added by the increase in CH4 emission compared to that of the untreated microcosms. The recovery of the system after CH2F2 treatment was studied by measuring the CH4 fluxes without the inhibitor 1 day and 2 weeks after the inhibitor treatment. After 1 day the CH4 emission from CH2F2-treated microcosms was about 70% of the CH4 emission from the controls. After 14 days the fluxes of the controls and the inhibitor-treated microcosms were equal, which allowed repeated inhibitor measurements with the same microcosms.

Division into compartments.

The bulk soil was taken directly from the non-root-containing compartments of the microcosms and mixed 1:3 (by weight) with sterile tap water. The root-containing soil (rhizosphere) was strongly attached to the roots and therefore was removed together with the plants. To separate the soil, the roots were washed twice in 125 ml of sterile tap water. The resulting soil suspensions were subsequently pooled and are referred to below as the rhizosphere. The roots were washed again with tap water to remove the remaining soil particles. The rhizoplane was detached by adding sterile glass beads and tap water to the roots (ratio of roots to glass beads to water, 1:10:10 [wt/wt/wt]) and shaking the preparation at 180 rpm for at least 30 min. The resulting suspension was decanted and is referred to below as the rhizoplane. The remaining roots were thoroughly washed with sterile tap water and cut into small pieces. Root pieces and sterile tap water (1:10, wt/wt) were homogenized for 2 min (Standard Blender 260: catalog no. FD-216; Buddeberg, Mannheim, Germany). The resulting suspension is referred to below as the homogenate.

Potential methane oxidation.

Four microcosms containing plants of each age (28, 57, and 92 days after transplanting [dap]) were used. Slurries of the soils in the two soil compartments of each microcosm were prepared as described above. To study the potential CH4 oxidation rates (MOR) on the rice roots, whole washed roots were used. All samples were measured in three parallel incubations. Soil slurries (20 ml) and roots were transferred into sterile glass bottles (150 ml for slurries; 50 ml for roots), which were closed with stoppers and supplemented with 10,000 ppm (by volume) of CH4 each. The bottles were incubated at 25°C in the dark and shaken at 120 rpm. Methane depletion was monitored by sampling the headspace after the bottles were shaken thoroughly and then performing an analysis with a gas chromtograph equipped with a flame ionization detector. The first sample was taken 30 min after CH4 was added, and this was followed by sampling at 2-h intervals during the first 8 h of the experiments. Then the bottles were left overnight and sampled the next day at 2-h intervals again. From the mean CH4 depletion curves for the three parallel samples from one microcosm, two linear regressions were calculated. The first regression described the initial CH4 oxidation, which corresponded to the CH4 depletion at the beginning of the measurements until the onset of fast (induced) CH4 oxidation. The second regression described the fast (induced) CH4 oxidation period. The initial and induced MOR were calculated from the slopes of these regression lines. The time lag until the onset of induced CH4 oxidation was determined from the point of intersection of the two regression lines.

Cell counting by the MPN technique.

All four compartments (bulk soil, rhizosphere, rhizoplane, and homogenate) of one (20 and 72 dap), two (85 dap), or four (28, 57, and 92 dap) parallel microcosms were used for most-probable-number (MPN) determinations. Each sample was diluted in twofold steps in 2 × 8 parallel dilution series (microtiter plates) by using ammonia mineral salt medium (modified as described by Whittenbury et al. [47]) containing 0.5 g of NH4Cl per liter and 0.54 g of KH2PO4 per liter; the pH was adjusted to 6.8. Trace element solution SL10a (2 ml liter−1), MgSO4 (final concentration, 0.2 g liter−1), and CaCl2 (final concentration, 0.015 g liter−1) were added after autoclaving (19). Inoculated plates were incubated in gas-tight jars at 25°C for 4 weeks in the dark. One of the two parallel microtiter plates was incubated in an atmosphere containing 20% CH4 in synthetic air (20.5% O2 in N2): the other plate was incubated in synthetic air as a control for heterotrophic growth. Cell numbers and standard deviations for the eight parallel dilution series from one sample were calculated from positive dilutions by using the code number system and table of Rowe et al. (38). To illustrate the importance of the compartments for the whole system, the number of cells per total mass of each compartment was calculated. On average, the total root biomasses per plant were 0.24, 0.98, 4.46, 3.06, 2.74, and 3.37 g (dry weight) for the plants 20, 28, 57, 71, 85, and 92 dap, respectively.

16S rRNA targeting oligonucleotide probes.

Different oligonucleotide probes with high specificity for the two families of methanotrophs have been described recently (17). The following probes were used in this study (target sites refer to Escherichia coli numbering [12]): Mα450 (5′ATCCAGGTACCGTCATTATC3′), Mγ84 (5′CCACTCGTCAGCGCCCGA3′), and Mγ705 (5′CTGGTGTTCCTTCAGATC3′). For probe Mα450 no nonmethanotrophic pure culture with sequence identity to the probe was found in the EMBL database. The sequence of Methylocella (15), a new genus of acidotolerant α-protebacterial methanotrophs, exhibited two mismatches with this probe and therefore was not detected under the hybridization conditions used. For probe Mγ84 organisms like Thiorhodovibrio sibirica, Thiothrix eikelboomii, and Thiobacillus neapolitanus (a halophile), as well as Ectothiorodospira strains and phototrophic bacteria, exhibited no mismatches. However, parallel hybridization with probe Mγ84 and probe Mγ705, which showed no identity to cultures other than methanotrophic cultures, and adjustment of specificity with Thiobacillus thiooxidans allowed in situ quantification of both families of methanotrophs with these probes. The probes were synthesized and labeled with fluorochromes (fluorescein, Texas red, CY5) by MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany).

Fixation and whole-cell hybridization.

Samples of diluted soil slurries (2 ml of a 1:100 dilution), rhizoplane (1 to 2 ml), and homogenate (1 ml) were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 8 min. The pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.0) and were fixed with 300 μl of 4% paraformaldehyde (in PBS) for 2 h at room temperature. After they were washed five times with PBS, the pellets were resuspended in ethanol-PBS (1:1) and stored at −20°C until hybridization.

The hybridization protocol used was modified from the protocol of Assmus et al. (5) and has been described in detail previously (17). Prior to hybridization, 20 μl of fixed rhizoplane or homogenate suspension or 40 μl of soil suspension was transferred to eight-well coated slides and left to dry at room temperature overnight. Autofluorescence was quenched with 10 μl of 0.01% (wt/vol) toluidine blue 0 (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) in PBS (pH 7.0) for 30 min at room temperature. After they were rinsed with distilled water, the slides were washed in 50, 80, and 96% aqueous ethanol and hybridized with 20% formamide in hybridization buffer for 2 to 2.5 h at 46°C as described previously (5, 17). Samples were hybridized with universal eubacterial probe Eub338 (1), probe Mα450 (Methylocystaceae [17]), and probes Mγ84 and 705 (Methylococcaceae [17]) at the same time, and the DNA was stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). The slides were analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy with a Leica DMR XE microscope, an ×63 oil immersion lens, and TCS NT 1.6.582 software. Cells were counted by comparing images obtained for the four different single channels (DAPI, Eub338, Mα450, and Mγ84 plus 705). The number of DAPI-stained cells counted was the sum of all of the DAPI signals detected. The number of eubacterial cells was the number of DAPI- and Eub338-positive cells, and the methanotrophs counted were stained with DAPI, Eub338, and the family-specific probe.

DNA extraction.

Soil slurries (2 ml, undiluted) or 5-ml portions of either rhizoplane or homogenate suspensions were pelleted by centrifugation in 2-ml screw-cap tubes (13,000 × g, 5 min). The pellets were stored at −20°C until DNA was extracted. The DNA extraction protocol used was based on cell lysis with 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate in a cell disrupter, followed by DNA purification with ammonium acetate precipitation and isopropanol precipitation. The procedure was described in detail by Henckel et al. (24). To avoid interference from humic acids during PCR amplification, DNA derived from soil samples was purified further by using polyvinylpolypyrrolidine (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany), columns and a modified protocol described by Holben et al. (26). Polyvinylpolypyrrolidine was suspended overnight in 5 M HCl, and then washed with Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8.0), and the pH was adjusted to 8.0 with NaOH. Spin columns (Micro Bio-Spin chromatography columns: BioRad, Munich, Germany) were filled with 2 ml of this suspension and packed and dried by centrifugation (375 × g, 1 min) before they were loaded with 150 μl of DNA extract. DNA concentrations were estimated by spectrometry at a wavelength of 260 nm (GeneQuant spectrophotometer; Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) by using 1:10 dilutions in water. For PCR amplification, all DNA concentrations were adjusted to 2 ng of DNA μl−1.

PCR amplification.

The DNA was amplified by using three primer sets targeting 16S rRNA genes: a universal eubacterial primer set (primers 533f and 907r [45]), the 10γ primer set (primers 197f and 533r [42]) targeting methylotrophs that use the ribulose monophosphate (RuMP) pathway for carbon assimilation (including members of the Methylococcaceae), and the 9α primer set targeting methylotrophs that use the serine pathway for carbon assimilation (including members of the Methylocystaceae) (42). Additionally, one primer set for the α-subunit of the methanol dehydrogenase gene, which is present in all gram-negative (proteobacterial) methylotrophs, mxaF (primers 1003f and 15621r [32]), was used. For all primer pairs a GC clamp was attached to the 5′ end of one primer for subsequent denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analysis. The PCR protocols and primers used have been described in detail previously (24).

DGGE.

DGGE analysis was carried out as described by Henckel et al. (24) at 60°C and 150 V for 5 h (Dcode system; BioRad). Denaturing gradients from 40 to 70% were used for the primer set 9α amplification products, whereas for the amplification products of all other primer sets gradients from 35 to 70% were used (80% corresponded to 6.5% acrylamide, 5.6 M urea, and 32% deionized formamide). Gels were stained after electrophoresis in 1:30,000-diluted SYBR green I (Biozym, Hess Oldendorf, Germany) for 30 min and were scanned with a Storm 860 phosphor imager (Molecular Dynamics).

Reamplification and sequencing of DGGE bands.

DGGE bands were illuminated with a Dark Reader transilluminator (Clare Chemical Research, Ross on Wye, United Kingdom), excised, suspended in 200 μl of PCR grade water, and stored at −20°C. Band purity was controlled by reamplification and subsequent DGGE. Only reamplification products which resulted in a single band with the predicted electrophoretic mobility were sequenced. For sequencing, PCR products were purified by using QIAQuick PCR purification columns (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Sequencing reactions were performed by using an ABI-Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) as specified by the manufacturer. Cycle sequencing products were purified by using Microspin G-50 columns (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) and were analyzed with an ABI 373 DNA sequencer (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems).

Sequences were analyzed by using the Lasergene software package (DNA STAR, Madison, Wis.), 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences were aligned and phylogenetically analyzed with the ARB software package (1998 database, including about 13,000 sequences [41]) by using maximum-parsimony equations and the Jukes-Cantor correction. All sequences were also checked for the closest relatives by performing a BLAST search with a recent EMBL data library. The sequences of the closest relatives found in EMBL data library were aligned and added to the ARB database before trees were constructed. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method (ARB) by using complete 16S rDNA sequences of members of the α and γ subclasses of the Proteobacteria, as well as other species, whose sequences were closely related to the partial sequences retrieved in this study. The partial 16S rDNA sequences were placed in the neighbor-joining tree by keeping the tree topology constant (31). Sequences derived with the mxaF primer set were manually aligned with sequences retrieved from the GenBank database on the basis of amino acid sequences. Trees were constructed by using the neighbor-joining method and the protein correction algorithm PAM included in the ARB software package.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The accession numbers of the nucleotide sequences determined in this study are as follows: sequences obtained from 10γ amplifications, AJ300106 to AJ300120; sequences obtained from 9α amplifications, AJ300121 to AJ300127; and methanol dehydrogenase gene sequences, AJ300128, AJ300129, AJ300159, and AJ300160.

RESULTS

Methane oxidation activity and cell numbers.

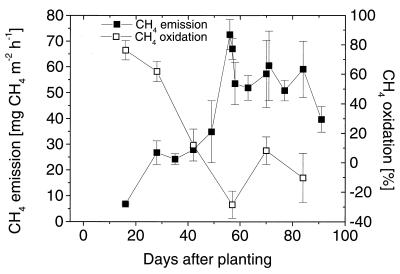

The level of in situ CH4 oxidation in the microcosms decreased from 70% at the beginning of plant growth to negligible values around 60 dap (Fig. 1). In parallel, the level of CH4 emission increased from 25 to 55 mg of CH4 m−2 h−1 and then remained stable until the end of the season (Fig. 1). The in situ CH4 oxidation activity was correlated with the plant growth phase, as the decline coincided with the onset of the reproductive growth phase.

FIG. 1.

In situ CH4 oxidation and emission from rice microcosms during the growth period. In situ oxidation was calculated from differences in the fluxes with and without the inhibitor CH2F2. The error bars indicate standard errors based on four parallel microcosms.

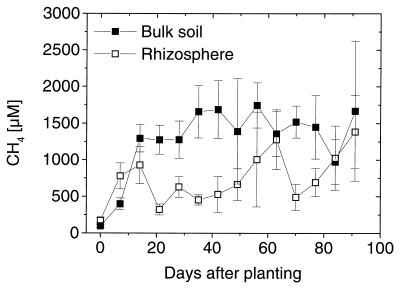

The porewater CH4 concentrations were lower in the rhizosphere than in the bulk soil for the whole growth period but never reached values less than 500 μM (Fig. 2). In the rhizosphere, the CH4 concentration was influenced by CH4 loss via the rice plants, as well as by CH4 oxidation activity.

FIG. 2.

Methane concentrations in the porewater of rhizosphere and bulk soil of rice microcosms during the growth period of rice. The error bars indicate standard errors based on three to six parallel microcosms.

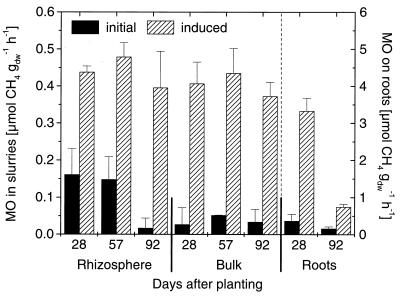

The potential CH4 oxidation in the soil slurries showed constant induced rates during the growth period and did not reflect in situ CH4 oxidation (Fig. 3). In contrast to the rates for the soil compartments, the induced rates measured for the whole, washed roots decreased from 3.3 μmol h−1 g (dry weight)−1 at 28 dap to 0.7 μmol h−1 g (dry weight)−1 at 92 dap and thus corresponded to the in situ activities measured (Fig. 3). For the initial MOR (Fig. 3) and lag phase (Table 1) almost no differences occurred during the growth period in the bulk soil, whereas in the rhizosphere the initial MOR decreased with increasing plant age (Fig. 3). At 92 dap the initial rates measured in the rhizosphere were almost as low as those in the bulk soil, but the lag phase value remained one-third of the bulk soil value, indicating that the physiological state of methanotrophs in the rhizosphere was different. The differences in the initial rates and the lag phase were even more pronounced for the roots, where the initial MOR decreased from 0.4 μmol h−1 g (dry weight)−1 at 28 dap to 0.2 μmol h−1 g (dry weight)−1 at 92 dap and the length of the lag phase increased from 16 to 52 h. Due to the different but unknown weight/surface ratios of soil and roots, a direct comparison of the rates in the soil compartments and on the roots was not possible. Nevertheless, the increasing lag phase and the decreasing potential rates of CH4 oxidation on roots with increasing plant age, which occured parallel to the decrease in in situ oxidation, indicated the importance of the roots for the overall oxidation.

FIG. 3.

Initial and induced rates of potential CH4 oxidation (MO) in soil slurries and on roots from rice microcosms containing plants of different ages. Bulk, bulk soil. The error bars indicate standard errors for samples from four parallel microcosms. The standard error for the initial MOR in bulk soil at 57 dap was too small to be seen. gdw, grams (dry weight).

TABLE 1.

Lag times until the onset of induced CH4 oxidation in vitro in samples from rice microcosms containing plants of different ages

| Time (dap) | Sample | Lag time (h) |

|---|---|---|

| 28 | Rhizosphere | 7.7 |

| Bulk soil | 21.1 | |

| Root | 16 | |

| 57 | Rhizosphere | 7.6 |

| Bulk soil | 26.4 | |

| Root | NDa | |

| 92 | Rhizosphere | 7.0 |

| Bulk soil | 22.9 | |

| Root | 51.5 |

ND, not determined.

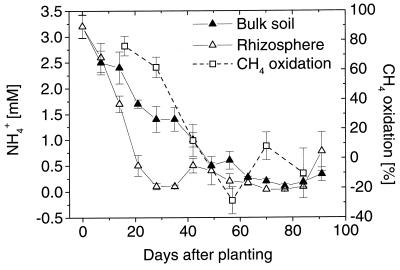

The initial MOR in the soil compartments decreased more slowly than the in situ CH4 oxidation and were still relatively high at 57 dap (0.15 and 0.05 μmol g [dry weight]−1 h−1 for rhizosphere and bulk soil, respectively) (Fig. 3). This less pronounced decrease indicates that there was in situ limitation of methane oxidation. The parallel decreases in porewater NH4 concentrations and in situ CH4 oxidation (Fig. 4) indicate that methanotrophs are limited by N sources.

FIG. 4.

Ammonia concentrations in the porewater of rice microcosms during the growth period. The in situ CH4 oxidation from Fig. 1 is given for comparison. The error bars indicate standard errors based on four parallel microcosms.

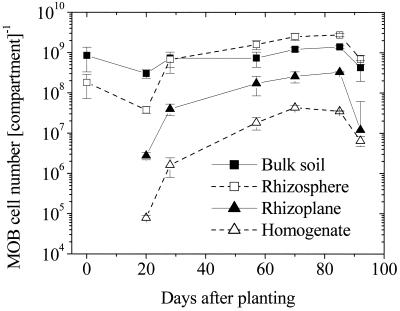

Like the potential MOR, the methanotrophic cell numbers reflected the stimulating effect of the roots, and the highest numbers per compartment were detected in the rhizosphere (Fig. 5). Even in the homogenate relatively high numbers of methanotrophs were detected, indicating that strong attachment of methanotrophs to the roots occurred. The increase in cell numbers continued after in situ CH4 oxidation decreased. The ongoing growth may be explained by a partially active methanotrophic population with an overall level of activity below the detection limit of the inhibitor measurements. Additionally, in the MPN assay vegetative cells plus resting stages were detected, which resulted in overestimation of the active population.

FIG. 5.

MPNs of methanotrophs (MOB) in the different compartments of rice microcosms during the growth period. Cell numbers were calculated based on the total masses in the compartments. The error bars indicate standard errors based on two to four parallel microcosms. At 20 and 72 dap only one microcosm was counted.

Community analysis.

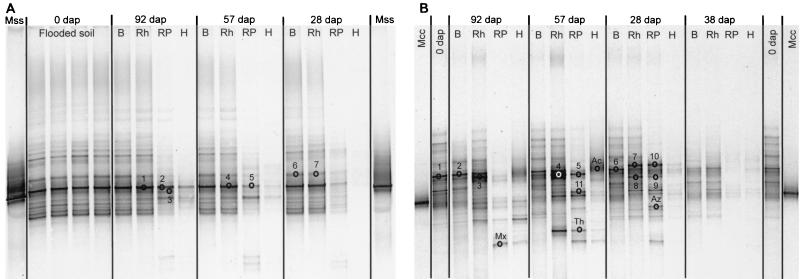

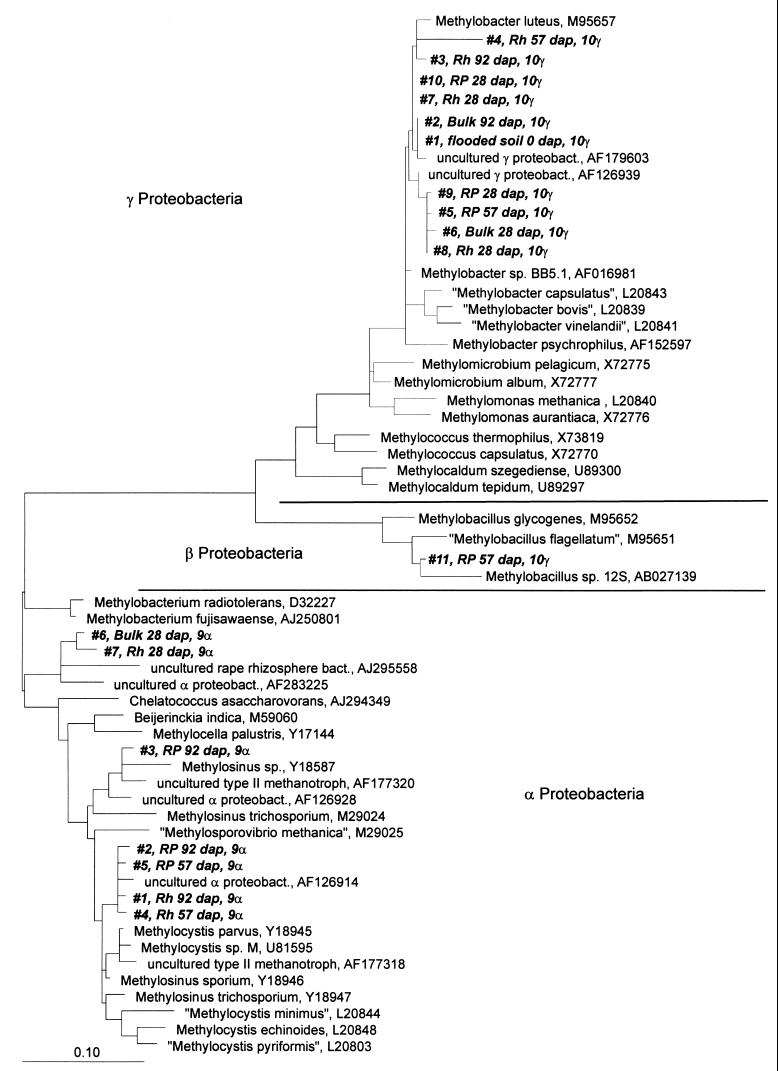

16S rDNA amplification with the universal eubacterial primer set resulted in PCR products for all of the samples investigated. The sequences of the DGGE bands obtained did not cluster with methanotroph sequences, indicating that this group was not dominant among the eubacteria. However, DGGE analysis based on amplifications with the 9α and 10γ primer sets and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) revealed the presence of members of both families of methanotrophs in all compartments during the whole season. The DGGE band patterns of the 9α amplification products indicated that there was a stable population of serine pathway methylotrophs (including members of the Methylocystaceae) during the whole growth period and in all compartments (Fig. 6A). The major bands in different DGGE lanes (Fig. 6A, bands 1, 2, 4, and 5) were excised and sequenced, and they clustered with the group of Methylosinus and Methylocystis spp.; the most closely related sequences were those found by Henckel et al. (24) (accession no. AF126928 and AF126914) in rice field soil and those found by Wise et al. (48) (accession no. AF177318 and AF177320) in landfill soil (Fig. 7). Minor bands with lower electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 6A, bands 6 and 7) clustered distantly with Methylobacterium sp. and were most closely related to sequences found in the rape rhizosphere (O. Kaiser, A. Puehler, and W. Selbitschka, unpublished data) (EMBL Data Library accession no. AJ295558) and in rice field soil (25) (accession no. AF283225) (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

DGGE band patterns retrieved after 16S rDNA amplification from soil and root compartments of rice microcosms. The bands that were excised and sequenced are indicated. B, bulk soil; Rh, rhizosphere; RP, rhizoplane; H, homogenate. (A) Band patterns of primer set 9α amplification products. Mss, amplification product obtained with DNA from a Methylosinus sporium culture. (B) Band patterns of primer set 10γ amplification products. Mcc, amplification product obtained with DNA from a Methylococcus capsulatus culture; Ac, sequence that clustered with Acinetobacter; Az, sequence that clustered with Azoarcus; Mx, sequence that clustered with Myxococcales; Th, sequence that clustered with Thiothrix.

FIG. 7.

Phylogenetic placement of sequences retrieved from DGGE gels after PCR amplification of rice microcosm samples with the 9α and 10γ primer sets for 16S rDNA. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method, using the maximum-parsimony algorithm and the Jukes-Cantor correction. Sequences are indicated as follows: running number (DGGE band number in Fig. 6), followed by the compartment (B, bulk soil; Rh, rhizosphere; RP, rhizoplane; H, homogenate), the age of the microcosm (in dap), and the primer set used for DNA amplification (primer set 9α or 10γ). proteobact., proteobacterium; bact., bacterium.

The band patterns resulting from 10γ amplifications suggested dynamics in the population structure of methylotrophs that use the RuMP pathway for carbon assimilation, including members of the Methylococcaceae (Fig. 6B). The changes in band patterns were found to be changes in the genus Methylobacter but could not be correlated with other genera of this family (Fig. 7). Additionally, sequencing showed that this assay was not specific for RuMP pathway methylotrophs, as some sequences clustered with the genus Acinetobacter, the genus Azoarcus, the order Myxococcales, and the genus Thiothrix. Therefore, the changes in the band patterns of the 10γ amplification products cannot be interpreted only as an indication of changes in the methylotrophic community. In the bulk soil, PCR amplification of the functional gene mxaF (encoding the α-subunit of methanol dehydrogenase) resulted in only faint DGGE bands, which could not be excised and analyzed further (Fig. 8A). Four bands from the rhizosphere and rhizoplane compartments could be exised and sequenced. The sequences obtained clustered with sequences of members of the family Methylococcaceae (Fig. 8B), and were most closely related to other sequences from rice field soil (25) (accession no. AF283243 and AF283244). Unfortunately, many single bands from the original DGGE gel resulted in multiple bands after reamplification and therefore could not be sequenced. Hence, the four bands analyzed do not reflect the complete diversity of the methylotrophic community in the system. However, these results illustrate that members of the Methylococcaceae were present in the root-influenced compartments.

FIG. 8.

(A) DGGE band patterns of mxaF amplification products from soil and root samples of rice microcosms. The bands that were excised and sequenced are indicated. Mss, amplification product obtained with DNA from a Methylosinus sporium culture; B, bulk soil; Rh, rhizosphere; RP, rhizoplane; H, homogenate. (B) Unrooted phylogenetic tree for mxaF sequences from rice microcosm samples compared to previously published sequences. Sequences are indicated as follows: running number (DGGE band number in Fig. 8A), followed by the compartment (Rh, rhizosphere; RP, rhizoplane), and the age of the microcosm (in dap). uncul. putative methanotr., uncultivated putative methanotroph.

The in situ dominance of both families of methanotrophs was investigated by using family-specific probes for FISH. This approach was limited by the relatively low number of methanotroph cells compared to the total number of cells determined by DAPI counting. In most cases the percentages of methanotrophs compared to the DAPI counts ranged from 0.5 to 0.9% in the soil compartments during the whole season; the flooded soil before planting was the only exception (3.4% of the DAPI counts) (Table 2). Only the rhizoplane and the homogenate at 92 dap contained higher percentages of methanotrophs (1.3 to 4.9%). Nevertheless, the results obtained with this method indicated the in situ dominance of the family Methylocystaceae over the whole season and in all compartments. Despite their low proportional cell numbers, members of the family Methylococcaceae were present in all compartments. In the rhizoplane higher percentages of these organisms were detected, and they accounted for one-half to two-thirds of the detectable methanotrophic population. Thus, the rhizoplane seems to be the most important site for growth of methanotrophs and maintenance of their diversity in the rice field ecosystem.

TABLE 2.

Relative numbers of eubacteria and methanotrophs detected by FISH in relation to the total DAPI counts during growth of rice in different microcosm compartments

| Time (dap) | Sample | DAPI count (no. of DNA- stained cells) | % of DAPI count with the following probesa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eub338 | Mα450 | Mγ84 + Mγ705 | |||

| 0 | Bulk soil | 697 | 41.9 | 3.0 | 0.4 |

| 28 | Bulk soil | 405 | 33.1 | <0.3 | 0.5 |

| Rhizosphere | 770 | 25.6 | 0.8 | 0.1 | |

| Rhizoplane | 596 | 43.3 | 3.0 | 1.9 | |

| Homogenate | 499 | 13.0 | 0.4 | <0.2 | |

| 57 | Bulk soil | 637 | 24.0 | 0.6 | <0.2 |

| Rhizosphere | 811 | 22 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Rhizoplane | 1,196 | 28.3 | 1.2 | 0.1 | |

| Homogenate | 1,150 | 21.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 92 | Bulk soil | 763 | 37.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Rhizosphere | 1,085 | 25.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | |

| Rhizoplane | 898 | 33.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | |

| Homogenate | 902 | 19.1 | 0.8 | 0.6 | |

The high relative proportions of members of both families detected in flooded soil before planting illustrate the ability of the organisms to survive starvation and stress, such as drying of the soil in winter.

DISCUSSION

Limitation of in situ CH4 oxidation activity.

The short period of high levels of in situ CH4 oxidation at the beginning of the growth period is in contrast to the results of previous studies, which showed that in situ CH4 oxidation occurred during the whole growth period of rice (10, 19). However, the latter in situ oxidation was determined by using other methods (e.g., CH3F inhibition or N2 headspace), another rice variety, and different growth conditions for the plants. All these factors might affect the percentage of in situ CH4 oxidation measured. The time pattern for in situ CH4 oxidation and CH4 emission detected in our study was confirmed by obtaining measurements in a rice field (30) using the inhibitor CH2F2 and the same rice variety that was used in the microcosms (KORAL).

The comparison of potential oxidation and in situ CH4 oxidation in this study indicated that there was in situ limitation of methanotrophs in the microcosms, as the initial MOR in the soil slurries decreased more slowly than the in situ CH4 oxidation. The most obvious limiting factor for methanotrophs is the availability of CH4 and O2. In this study the CH4 concentrations in the porewater always remained above 500 μM (Fig. 2) and thus did not limit methanotrophs. In microcosms of the same type incubated in parellel, rhizospheric O2 was detectable even 70 dap (4). Thus, the O2 concentration in the rhizosphere should allow a period of in situ CH4 oxidation longer than that detected in this study. Another important factor for methanotrophs is the availability of N sources (21, 23). The NH4+ concentrations in both soil compartments decreased during the first few weeks of plant growth to values around the detection limit, illustrating that the N cycle in the rice microcosms was dominated by N uptake by the rice plants. The parallel decreases in in situ CH4 oxidation and the NH4+ concentration in the porewater are consistent with experiments in which a positive effect of ammonia fertilization on methanotrophs in rice microcosms was shown (7). These recent findings are in contrast to the results of other studies, in which NH4+ fertilization had an inhibitory effect on CH4 oxidation in soils (22, 39, 40), sediments (8, 44), and dryland rice fields (16). However, a flooded rice field is characterized by elevated CH4 concentrations even in the rhizosphere, which leads to less pronounced competitive inhibition of the methane monooxygenase by NH4+ (13, 29, 44). Additionally, fast uptake of NH4+ and other ions by rice plants affects the influence of NH4+ fertilization on methanotrophs, as toxic compounds (e.g., NO2−) cannot accumulate in the porewater.

Community structure of methanotrophs.

The DGGE band patterns of the 9α primer set PCR amplification products showed that the community of serine pathway methylotrophs (including members of the Methylocystaceae) remained stable during the whole growth period and in all compartments of the system. Most sequences derived from the DGGE gel clustered with the known genera of the Methylocystaceae, Methylocystis and Methylosinus, and were most closely related to sequences detected previously in rice field soil after cloning of PCR amplification products (24). No differences in band intensities or numbers were detected after the decrease in in situ CH4 oxidation; thus, DGGE band patterns showed no direct correlation with in situ activities. Henckel et al. (24), in contrast, found that there were increases in the number and intensities of bands after the onset of CH4 oxidation in rice field soil with a nonsaturated water content in their experiment. In our system, the soil was flooded for 10 days before the first samples were taken. Therefore, the effects of increasing CH4 concentrations in the soil porewater and the onset of CH4 oxidation in the unplanted system on the methanotrophic community could not be monitored.

The DGGE band patterns for the RuMP pathway methylotrophs (including members of the Methylococcaceae) suggested that there were changes in the community of these methanotrophs. Sequencing showed that these changes occurred only with the genus Methylobacter, as all sequences related to the Methylococcaceae clustered with this genus. This indicates that members of the genus Methylobacter might be the dominant members of the family Methylococcaceae in the system studied, possibly reflecting the type of resting stage formed. The immature cysts of Methylomonas, Methylococcus, and Methylomicrobium strains do not survive desiccation (46); however, the Azotobacter-like cysts of Methylobacter strains, the exospores formed by Methylosinus strains, and the lipid cysts of Methylocystis strains are all desiccation resistant for several months (46). Drying of the rice field soil before use in the microcosm experiments might therefore have selected for Methylobacter strains as the only desiccation-resistant methanotrophs belonging to the Methylococcaceae. Drying of rice fields during the winter might have a similar effect in the natural environment. This hypothesis has to be proven with field studies.

The variation in the Methylococcaceae community that occurred parallel to the stability of the Methylocystaceae community led to the assumption that members of the two families behaved differently in response to changing environmental conditions. It is possible that members of the Methylococcaceae did react to changes in O2 leakage from the roots, which varies with root type and age (3, 18) and thereby influences the availability of O2 for methanotrophs. However, previously published data for the predominance of either family of methanotrophs based on CH4 and O2 concentrations are contradictory. The CH4 concentration seems to be the most important factor, influencing the dominance of one family, whereas no differences in the preferred O2 concentrations were found (2, 25, 35).

On the other hand, the change in the Methylococcaceae community occurred parallel to the decrease in the NH4+ concentration in the porewater (Fig. 4 and 6B) and might therefore be explained by a stronger influence of the availability of N sources on members of the Methylococcaceae than on members of the Methylocystaceae. A positive effect of NH4+ on members of the Methylococcaceae was suggested previously by Hanson and Hanson (23) and was shown experimentally with soil slurries from rice microcosms by Bodelier et al. (7), who observed a greater increase in the biomass of members of the Methylococcaceae than of members of the Methylocystaceae after NH4+ fertilization. Graham et al. (21) found that members of the Methylocystaceae dominated under nitrogen-limited conditions in a pulp mill treatment pond and in a laboratory continuous-flow reactor, suggesting that members of the genera of this family can outcompete members of the Methylococcaceae under these conditions.

In situ dominance of Methylocystaceae.

This is the first study to show the in situ dominance of either family of methanotrophs with family-specific probes (17) and FISH. Despite the low percentage of methanotrophic cells compared to the overall DAPI counts, there was evidence of in situ dominance of members of the Methylocystaceae during the whole season and in all compartments. Members of the Methylococcaceae occurred at higher relative proportions only in the rhizoplane, illustrating the importance of the rice roots for the methanotrophic diversity of the rice field ecosystem. In previous studies strains belonging to the Methylocystaceae have been isolated from the highest positive MPN dilutions of rice root and rice field soil incubation mixtures (7, 43), indicating the numerical dominance of this family. Our FISH results indicate that these data were not influenced by cultivation biases but reflected the numerical ratio of members of the methanotrophic families in situ.

Members of the Methylocystaceae were detected by FISH at constant relative amounts even in the bulk soil, where no methanotrophic growth and activity should have been possible due the lack of O2. The cells of these organisms have a high ribosome content and might have entered a stage of anaerobic dormancy, in which they survive as vegetative cells (36, 37). This corresponds to the initial MOR in bulk soil even 92 dap.

The large increase in the overall methanotrophic cell counts in the root compartments compared to the more stable numbers in the soil compartments (Fig. 5) showed the importance of the roots for the growth of methanotrophs. This conclusion was supported by amplification of the gene for methanol dehydrogenase (mxaF), which resulted in visible DGGE bands only for the rhizosphere and the rhizoplane, indicating that there were higher target numbers and thus growth of methanotrophs in these compartments (24). The O2 supplied by the roots thus seems to be the key factor regulating methanotrophic growth in rice microcosms, followed by the availability of N sources.

The finding that the MPNs in the homogenate were nearly 10% of MPNs obtained from the rhizoplane is intriguing, because CH4 oxidation has been shown to be associated with the stems of rice plants (9) and methanotrophs have been detected even in the xylem of rice roots (20). However, our observation should not be taken as proof that methanotrophs are endophytic; rather, it shows that strong binding of methanotrophs to rice roots occurs.

Conclusions.

Both families of methanotrophs occur in the rice microcosm system, but drying of the soil selected for genera with a desiccation-resistant resting stage. The main population growth occurred during the first 2 months of the growth period, accounting for the losses during the remainder of the year. The rhizoplane supported the greatest diversity of methanotrophs. FISH analysis provided evidence that in situ dominance by members of the family Methylocystaceae occurred during the whole season and in all compartments. The methanotrophic activity in the rice microcosms seemed to be influenced mainly by the rice roots and the availability of N sources.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants Fr1054 and SFB 395 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

We thank Paul L. E. Bodelier and Martin Krüger for cooperation, Stephan Stubner for an introduction to confocal laser scanning microscope use, and Alexandra Hahn and Bianca Wagner for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Binder B J, Olson R J, Chisholm S W, Devereux R, Stahl D A. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaral J A, Knowles R. Growth of methanotrophs in methane and oxygen counter gradients. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;126:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong W. Radial oxygen losses from intact rice roots as affected by distance from the apex, respiration and waterlogging. Physiol Plant. 1971;25:192–197. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arth I, Frenzel P. Nitrification and denitrification in the rhizosphere of rice: the detection of processes by a new multichannel electrode. Biol Fertil Soils. 2000;31:427–435. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assmus B, Hutzler P, Kirchhof G, Amann R, Lawrence J R, Hartmann A. In situ localization of Azospirillum brasilense in the rhizosphere of wheat with fluorescently labeled, rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes and scanning confocal laser microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.1013-1019.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodelier P L E, Duyts H, Blom C W P M, Laanbroek H J. Interactions between nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria in gnotobiotic microcosms planted with the emergent macrophyte Glyceria maxima. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodelier P L E, Roslev P, Henckel T, Frenzel P. Stimulation by ammonium-based fertilizers of methane oxidation in soil around rice roots. Nature. 2000;403:421–424. doi: 10.1038/35000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosse U, Frenzel P, Conrad R. Inhibition of methane oxidation by ammonium in the surface layer of a littoral sediment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1993;13:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosse U, Frenzel P. Activity and distribution of CH4-oxidizing bacteria in flooded rice microcosms and in rice plants (Oryza sativa) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1199–1207. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1199-1207.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosse U, Frenzel P. Methane emissions from rice microcosms: the balance of production, accumulation and oxidation. Biogeochemistry. 1998;41:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowman J P. The prokaryotes. [Online.] New York, N.Y: Springer Verlag; 1999, posting date.. The methanotrophs—the families Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae. In M. Dworkin (ed.)http://link.springer-ny.com . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brosius J, Palmer M L, Kennedy P J, Noller H H. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 16S ribosomal RNA gene from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4801–4805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai Z C, Mosier A R. Effect of NH4Cl addition on methane oxidation by paddy soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2000;32:1537–1545. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassman K G, Peng S, Olk D C, Ladha J K, Reichardt W, Doberman A, Singh U. Opportunities for increased nitrogen-use efficiency from improved resource management in irrigated rice systems. Field Crops Res. 1998;56:7–39. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dedysh S N, Liesack W, Khmelenina V N, Suzina N E, Trotsenko Y A, Semrau J D, Bares A M, Panikov N S, Tiedje J M. Methylocella palustris gen. nov., sp. nov., a new methane-oxidizing acidophilic bacterium from peat bogs, representing a novel subtype of serine-pathway methanotrophs. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:955–969. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-3-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubey S K, Singh J S. Spatio-temporal variation and effect of urea fertilization on methanotrophs in a tropical dryland rice field. Soil Biol Biochem. 2000;32:521–526. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eller G, Stubner S, Frenzel P. Group specific 16S rRNA targeted probes for the detection of type I and type II methanotrophs by fluorescence in situ hybridisation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;198:31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flessa H, Fischer W R. Plant-induced changes in the redox potentials of rice rhizosphere. Plant Soil. 1992;143:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert B, Frenzel P. Methanotrophic bacteria in the rhizosphere of rice microcosms and their effect on porewater methane concentration and methane emission. Biol Fertil Soils. 1995;20:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert B, Aßmus B, Hartmann A, Frenzel P. In-situ localization of two methanotrophic strains in the rhizosphere of rice plants by combined use of fluorescently labeled antibodies and 16S rRNA signature probes. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham D W, Chaudhary J A, Hanson R S, Arnold R G. Factors affecting competition between type-I and type-II methanotrophs in 2-organism, continuous-flow reactors. Microb Ecol. 1993;25:1–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00182126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gulledge J, Doyle A P, Schimel J P. Different NH4+-inhibition patterns of soil CH4 consumption—a result of distinct CH4-oxidizer populations across sites. Soil Biol Biochem. 1997;29:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanson R S, Hanson T E. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:439–471. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.439-471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henckel T, Friedrich M, Conrad R. Molecular analyses of the methane-oxidizing microbial community in rice field soil by targeting the genes of the 16S rRNA, particulate methane monooxygenase, and methanol dehydrogenase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1980–1990. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1980-1990.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henckel T. Charakterisierung der methanotrophen Lebensgemeinschaften im Reisfeld- und Waldboden. Ph.D. thesis. Marburg, Germany: Phillips-Universität Marburg/Lahn; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holben W E, Jansson J K, Chelm B K, Tiedje J M. DNA probe method for the detection of specific microorganisms in the soil bacterial community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:703–711. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.3.703-711.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holzapfel-Pschorn A, Conrad R, Seiler W. Effects of vegetation on the emission of methane from submerged paddy soil. Plant Soil. 1986;92:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Radiative forcing of climate change and evaluation of the IPCC IS92 emission scenarios. Climate change. New York, N.Y: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.King G M, Schnell S. Ammonium and nitrite inhibition of methane oxidation by Methylobacter albus BG8 and Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b at low methane concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3508–3513. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3508-3513.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krüger M, Frenzel P, Conrad R. Microbial processes influencing methane emission from rice fields. Global Change Biol. 2001;7:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludwig W, Strunk O, Klugbauer S, Klugbauer N, Weizenegger M, Neumaier J, Bachleitner M, Schleifer K H. Bacterial phylogeny based on comparative sequence analysis. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:554–568. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald I R, Kenna E M, Murrell J C. Detection of methanotrophic bacteria in environmental samples with the PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:116–121. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.116-121.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller L G, Sasson C, Oremland R S. Difluoromethane, a new and improved inhibitor of methanotrophy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4357–4362. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4357-4362.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neue H U. Fluxes of methane from rice fields and potential for mitigation. Soil Use Manag. 1997;13:258–267. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ren T, Amaral J A, Knowles R. The response of methane consumption by pure cultures of methanotrophic bacteria to oxygen. Can J Microbiol. 1997;43:925–928. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roslev P, King G M. Survival and recovery of methanotrophic bacteria starved under oxic and anoxic conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2602–2608. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2602-2608.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roslev P, King G M. Aerobic and anaerobic starvation metabolism in methanotrophic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1563–1570. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1563-1570.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rowe R, Todd R, Waide J. Microtechnique for most-probable-number analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:675–680. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.3.675-680.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schnell S, King G M. Mechanistic analysis of ammonium inhibition of atmospheric methane consumption in forest soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3514–3521. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3514-3521.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steudler P A, Bowden R D, Melillo J M, Aber J D. Influence of nitrogen fertilization on methane uptake in temperate forest soils. Nature. 1989;341:314–316. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strunk O, Ludwig W. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. [Online.] Munich, Germany: Technische Universität München; 1996, posting date.. http://www.biol.chemie.tu-muenchen.de/pub/ARB . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsien H C, Bratina B J, Tsuji K, Hanson R S. Use of oligodeoxynucleotide signature probes for identification of physiological groups of methylotrophic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2858–2865. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2858-2865.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Bodegom P. Methane emissions from rice paddies; experiments and modelling. Ph.D. thesis. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Wageningen University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Nat F J W A, de Brouwer J F C, Middelburg J J, Laanbroek H J. Spatial distribution and inhibition by ammonium of methane oxidation in intertidal freshwater marshes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4734–4740. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4734-4740.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whittenbury R, Davies S L, Davey J F. Exospores and cysts formed by methane-utilizing bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;61:219–226. doi: 10.1099/00221287-61-2-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whittenbury R, Philips K C, Wilkinson J F. Enrichment, isolation, and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;61:205–218. doi: 10.1099/00221287-61-2-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wise M G, McArthur J V, Shimkets L J. Methanotroph diversity in landfill soil: isolation of novel type I and type II methanotrophs whose presence was suggested by culture-independent 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4887–4897. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4887-4897.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]