Abstract

Aims

Recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide (rh‐BNP) is commonly used as a decongestive therapy. This study aimed to investigate the instant effects of rh‐BNP on cardiac output and venous return function in post‐cardiotomy patients with congestive heart failure (CHF).

Methods and results

Twenty‐four post‐cardiotomy heart failure patients were enrolled and received a standard loading dose of rh‐BNP. Haemodynamic monitoring was performed via a pulmonary artery catheter before and after the administration of rh‐BNP. The cardiac output and venous return functions were estimated by depicting Frank‐Starling and Guyton curves. After rh‐BNP infusion, variables reflecting cardiac congestion and venous return function, such as pulmonary artery wedge pressure, mean systemic filling pressure (Pmsf) and venous return resistance index (VRRI), reduced from 15 ± 3 to 13 ± 3 mmHg, from 32 ± 7 to 28 ± 7 mmHg and from 6.7 ± 2.6 to 5.7 ± 1.8 mmHg min m2/L, respectively. Meanwhile, cardiac index, stroke volume index, and the cardiac output function curve remained unchanged per se. The decline in Pmsf [−13% (−22% to −8%)] and VRRI [−12% (−25% to −5%)] was much greater than that in the systemic vascular resistance index [−7% (−14% to 0%)]. In the subgroup analysis of reduced ejection fraction (<40%) patients, the aforementioned changes were more significant.

Conclusions

rh‐BNP might ameliorate venous return rather than cardiac output function in post‐cardiotomy CHF patients.

Keywords: rh‐BNP, Venous return, Cardiac output, Congestive heart failure

Introduction

Patients who undergo cardiac surgery are more likely to develop acute congestive heart failure (CHF) due to pre‐operative cardiac dysfunction, acute structural changes, intraoperative myocardial injury, and improper post‐operative management. 1 Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is an endogenous hormone released by the ventricles 2 to adjust circulatory pressure, volume distribution, and attenuate congestion progression during CHF. 3 Hence, the recombinant human BNP (rh‐BNP), a medicine with the same structure as native BNP, is considered as a decongestant with a significant effect on reducing both right‐sided and left‐sided filling pressures. 4 , 5

Previous studies performed in cardiac surgical populations demonstrated that empiric post‐operative use of rh‐BNP brought neither additional risks nor benefits, 6 , 7 , 8 which implies that a deeper understanding of rh‐BNP's role in haemodynamic regulation to guide the use of rh‐BNP is needed. However, the physiological therapeutic effects of rh‐BNP remain controversial. Early studies showed that rh‐BNP caused an increased cardiac output (CO). 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 However, as we have known, rh‐BNP is not an inotrope and does not have a signalling pathway enabling it to enhance myocardial contractility. 4 , 11 Furthermore, several subsequent studies conducted on cardiac surgical and paediatric patients reported no changes in CO. 13 , 14 , 15 The intrinsic explanation for these inconsistencies in CO function is still unclear. Almost all studies reported an attenuation in overhigh filling pressure without decreasing the blood volume returned to the heart (which is usually equal to CO). 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Therefore, how rh‐BNP can affect venous return and alleviate congestion should be investigated further.

Both CO function (Frank‐Starling) curve 16 and venous return (Guyton) curve 17 are intuitive methods used to describe the working status of the heart and venous system. This physiological study was designed therefore, to investigate the instant effects of rh‐BNP on CO and venous return functions among patients with post‐cardiotomy heart failure.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China: Number B2020‐056), and conducted in a 40‐bed cardiac surgical intensive care unit (ICU). Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they met all of the following criteria 1 : clinical manifestations suggesting CHF {congestion on chest radiograph, rales on chest auscultation, clinically relevant oedema or an elevated filling pressure [either central venous pressure (CVP) ≥ 12 mmHg or pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP) ≥ 15 mmHg], and an increased N terminal pro BNP [NT‐proBNP > 900 pg/mL]}, 2 , 18 , 19 weaning failure (failed spontaneous breathing test) and relied on mechanical ventilation, 3 haemodynamic monitoring via a pulmonary artery catheter, 4 decision from the attending physician to use rh‐BNP. Exclusion criteria were 1 : patients < 18 years old, 2 pregnant, 3 haemodynamic instability (norepinephrine or epinephrine ≥ 0.1 μg/kg/min), 4 unable to tolerate postural and positive end‐expiratory pressure (PEEP) changes, 5 arrythmias, and 6 severe acute kidney injury [KDIGO stage 3 20 or underwent renal replacement therapy (RRT)]. Written informed consent was obtained from patients' legally authorized representatives.

Measurements of haemodynamic effects

Throughout the study, patients were sedated with a combination of remifentanil and midazolam, with the aim of achieving a Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale 21 of −5. Haemodynamic monitoring was conducted by using a pulmonary artery catheter (Swan‐Ganz CCOmbo 774F75, Edwards Lifescience Corporation, Irvine, USA). Pressure transducers were zeroed and fixed at the intersection of the mid‐axillary line and the fourth intercostal space. For each enrolled patient, rh‐BNP (an alternative drug of nesiritide, produced by Tibet Rhodiola pharmaceutical Inc., Chengdu, China) was prepared at a concentration of 10 μg/mL and administered as a standard intravenous bolus of 2 μg/kg (over 15 min) followed by a continuous infusion at a rate of 0.01 μg/kg/min.

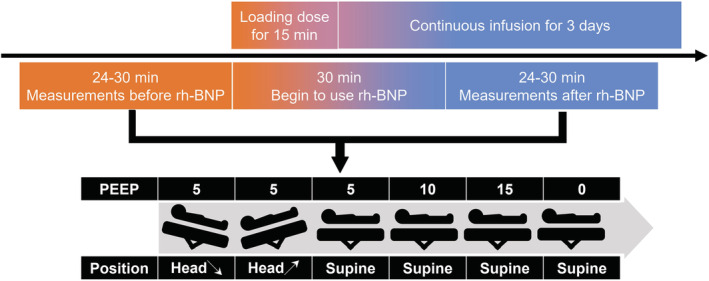

Before using rh‐BNP, a set of baseline haemodynamic parameters, including heart rate, CVP, PAWP, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure (MAP), pulse pressure, mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP), systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI), cardiac index (CI), and stroke volume index (SVI), were recorded. Furthermore, cardiac function and venous return curves were depicted, and their corresponding parameters were calculated based on a detailed protocol. Thirty minutes after initiation of the loading dose, measurements of preceding parameters were repeated. The study protocol was completed within 90 min (Figure 1 ). During the protocol period, diuretics were withheld while other medications remained unchanged, and the total fluid volume and urine output (UO) were recorded. Furthermore, 1 h UO before and after the initiation of rh‐BNP (for 30 min) was also recorded.

Figure 1.

Research flow chart. All patients received a loading dose of 2 μg/kg over 15 min and a continuous infusion of 0.01 μg/kg/min for 3 days. Before and after administration of rh‐BNP, some manoeuvres were performed to measure three points induced by postural changes and four points by positive end‐expiratory pressure gradients to depict the Frank‐Starling and venous return curves before and after using rh‐BNP. rh‐BNP, recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide.

The methods of estimating the cardiac output and venous return function

The Frank‐Starling curve describes how CO changes with preload 22 and the Trendelenburg manoeuvre could be used to simulate changes of the preload. 23 In this section, patients were placed at three different positions (supine and 15° downward or upward bed angulation) but with the same PEEP setting of 5 cmH2O. For each position, after a 3 min stabilization, CVP and its corresponding CI were recorded. Using these three (CVP, CI) coordinate pairs and a horizontal axis intercept of −2 mmHg, the cardiac function curve was regressed as a logarithmic function (A*ln(X + B) + C). 22

To assess the venous return curve, four gradients of the PEEP settings (0, 5, 10, and 15 cmH2O) were used to increased intrathoracic pressure, which would further increase the CVP (representing the backward resistance of venous return). Similarly, four (CVP, CI) coordinate pairs were measured to perform a linear regression. Theoretically, . From this, the horizontal axis intercept and the inverse of the slope of the regression line represented the mean systemic filling pressure (Pmsf) and the venous return resistance index (VRRI), respectively. 17

Data collection

Upon patient inclusion, demographic information, comorbidity, and intraoperative information were recorded. Echocardiographic parameters [left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), left atrial diameter, left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter, and left ventricular end‐systolic diameter] and laboratory parameters (cardiac troponin T, NT‐proBNP, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen,bilirubin, albumin and lactate) of the same day were also collected. All study patients were followed up until hospital discharge or death, to record clinical outcomes, such as RRT rate, length of mechanical ventilation, length of ICU stay, length of hospital stay, and hospital mortality.

Data analysis

The number of patients included in similar haemodynamic studies ranges from 15 to 25. 24 , 25 , 26 Therefore, an initial target of 30 cases was set for this study and an interim analysis was conducted when 80% of the target (24 cases) was reached, at which point the decision was made to terminate enrolment based on the significance of the results. Data were presented as the means ± standard deviations (if normally distributed) or medians with interquartile ranges [IQR] (if non‐normally distributed) for continuous variables, and total numbers with percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons were made using Student's t‐test or Wilcoxon rank‐sum test for continuous variables, and the Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. To describe the overall effects of rh‐BNP, integrated CO and venous return curves were depicted based on the mean values of equation coefficients. Furthermore, we compared the characteristics and therapeutic effects of rh‐BNP between patients with LVEF ≤ or >40%, namely heart failure with reduced EF (HFrEF) or mildly reduced and preserved EF (HFmrEF and HFpEF). 27 , 28 All statistical tests were two‐tailed, and a value of P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patients

During the study period (June 2020 to April 2021), 24 patients were included and of them, 20 (83%) received aortic/mitral/tricuspid valve surgery, and four patients (17%) underwent coronary artery bypass surgery, and their characteristics are presented in Table 1 . On the day of rh‐BNP administration, the LVEF, TAPSE, and NT‐proBNP were 50% (IQR: 36–62), 13 mm (IQR 11–17), and 2622 ng/mL (IQR 1506–9966), respectively. During the ICU stay, five patients (21%) received RRT and only one (4%) died. The length of mechanical ventilation, ICU stay, and hospital stay were 3 days (IQR 2–9), 10 days (IQR 6–16) and 20 days (IQR 12–31), respectively. Among those patients, 10 (42%) had HFrEF. Patients with HFrEF had larger left ventricular diameters. They also appeared to have a trend of higher NT‐proBNP and blood urea nitrogen, despite the lack of statistical significance.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical, surgical, laboratory, echocardiographic characteristics and clinical outcomes by ejection fraction

| All patients (n = 24) | HFrEF (n = 10) | HFmrEF or HFpEF (n = 14) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐operative characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 60 ± 14 | 67 ± 13 | 59 ± 15 | 0.688 |

| Male, n (%) | 16 (67) | 9 (90) | 7 (50) | 0.079 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | 22 ± 3 | 0.192 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 6 (25) | 4 (40) | 2 (14) | 0.192 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 6 (25) | 1 (10) | 5 (36) | 0.341 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 3 (13) | 2 (20) | 1 (7) | 0.550 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 9 (38) | 4 (40) | 5 (36) | 1.000 |

| NYHA class III–IV, n (%) | 12 (50) | 6 (60) | 7 (50) | 0.697 |

| Operative information | ||||

| Re‐do surgery, n (%) | 6 (25) | 1 (10) | 5 (36) | 0.341 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time (min) | 142 ± 42 | 143 ± 42 | 141 ± 44 | 0.941 |

| Aortic cross‐clamping time (min) | 84 ± 35 | 92 ± 32 | 76 ± 36 | 0.302 |

| Information on the day of using rh‐BNP | ||||

| Time‐point of rh‐BNP administration (h) | 41 (20–68) | 34 (20–87) | 41 (22–100) | 0.558 |

| LVEF (%) | 50(36–62) | 34(29–37) | 62(56–65) | <0.001 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 13 (11–17) | 12 (10–16) | 15 (11–17) | 0.291 |

| Left atrial diameter (mm) | 45 (42–49) | 45 (44–50) | 43 (41–49) | 0.187 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 47 (44–59) | 60 (47–69) | 44 (41–48) | 0.039 |

| LVESD (mm) | 33 (29–45) | 42 (38–58) | 29 (26–32) | 0.008 |

| cTnT (ng/mL) | 0.58 (0.41–1.38) | 0.78 (0.53–1.80) | 0.52 (0.41–0.91) | 0.219 |

| NT‐proBNP (ng/mL) | 2622 (1506–9966) | 7897 (1955–14 485) | 2192 (1291–4578) | 0.057 |

| Creatinine (μmmol/L) | 121 (98–198) | 158 (105–254) | 115 (84–151) | 0.171 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 10 (8–16) | 14 (9–22) | 10 (7–12) | 0.050 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 20 (14–33) | 16 (14–20) | 27 (18–47) | 0.049 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 37 (34–38) | 37 (35–38) | 36 (33–37) | 0.262 |

| Lactate (μmmol/L) | 1.3 (1.2–1.6) | 1.3 (1.2–1.7) | 1.4 (1.2–1.5) | 0.637 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| Renal replacement therapy, n (%) | 5 (21) | 4 (29) | 1 (10) | 0.358 |

| Length of mechanical ventilation (day) | 3 (2–9) | 4 (3–14) | 3 (2–7) | 0.472 |

| Length of ICU stay (day) | 10 (6–16) | 11 (9–15) | 8 (5–16) | 0.428 |

| Length of hospital stay (day) | 20 (12–31) | 22 (14–28) | 18 (12–33) | 0.445 |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 1 (4) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.417 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; HFmrEF, heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; ICU, intensive care unit; LVEDD, left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end‐systolic diameter; NT‐proBNP, N terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Haemodynamic parameters

The haemodynamic parameters before and after the administration of rh‐BNP were measured and are summarized in Table 2 . During the study period, fluid volume and UO were 73 ± 22 and 85 ± 27 mL, respectively. After the loading dose of rh‐BNP, the heart rate (84 ± 16 to 85 ± 17 beat/min, P = 0.091), CI (3.0 ± 0.5 to 3.0 ± 0.6 L/min/m2, P = 0.542) and SVI (37 ± 8 to 36 ± 9 mL/m2, P = 0.208) remained unchanged. Whereas CVP (12 ± 3 to 11 ± 3 mmHg, P < 0.001), PAWP (15 ± 3 to 13 ± 3 mmHg, P < 0.001), MAP (73 ± 8 to 66 ± 7 mmHg, P < 0.001) and MPAP (25 ± 6 to 22 ± 6 mmHg, P < 0.001) decreased significantly. The percent changes were −8% (IQR 11 to −5), −13% (IQR 22 to −8), −8% (IQR 13 to −3), and −9% (IQR: 13 to −5) for CVP, PAWP, MAP, and MPAP, respectively. However, we only observed a reduction in SVRI (21.1 ± 6 to 19.4 ± 4.9 mmHg min m2/L, P = 0.004) rather than PVRI (mmHg min m2/L, P = 0.199). The declines in CVP and PAWP were 8% (IQR 5 to 11) and 13% (IQR 6 to 18). Besides, we also observed a slight increase of UO after the loading dose of rh‐BNP in both subgroups.

Table 2.

The comparisons of haemodynamic parameters and urine output before and after using rh‐BNP

| Parameters | All patients (n = 24) | HFrEF (n = 10) | HFmrEF or HFpEF (n = 14) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before rh‐BNP | After rh‐BNP | Percent change (%) | Before rh‐BNP | After rh‐BNP | Percent change (%) | Before rh‐BNP | After rh‐BNP | Percent change (%) | |

| HR (beat/min) | 84 ± 16 | 85 ± 17 | 1 (0 to 1) | 89 ± 18 | 90 ± 18 | 1 (0 to 1) | 80 ± 15 | 82 ± 15 | 0 (−1 to 3) |

| CVP (mmHg) | 12 ± 3 | 11 ± 3* | −8 (−11 to −5) | 11 ± 2 | 10 ± 2* | −9 (−11 to −8) | 14 ± 4† | 12 ± 4*,† | −7 (−11 to −2) |

| PAWP (mmHg) | 15 ± 3 | 13 ± 3* | −13 (−22 to −8) | 16 ± 4 | 13 ± 4* | −17 (−24 to −13) | 14 ± 3 | 12 ± 3* | −10 (−12 to −7) |

| Pmsf (mmHg) | 32 ± 7 | 28 ± 7* | −13 (−18 to −6) | 31 ± 8 | 26 ± 5* | −18 (−22 to −13) | 32 ± 8 | 29 ± 7* | −10 (−15 to −4)† |

| Pmsf‐CVP (mmHg) | 19 ± 7 | 17 ± 6* | −13 (−1 to −23) | 21 ± 9 | 16 ± 6* | −24 (−11 to −30) | 18 ± 7 | 17 ± 6 | −6 (−17 to 9)† |

| SBP (mmHg) | 113 ± 13 | 105 ± 13* | −4 (−13 to −1) | 110 ± 14 | 102 ± 14* | −5 (−11 to −2) | 116 ± 13 | 107 ± 12* | −3 (−13 to 1) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 55 ± 7 | 51 ± 6* | −8 (−11 to −2) | 54 ± 8 | 50 ± 5* | −9 (−11 to −3) | 56 ± 7 | 51 ± 7* | −8 (−11 to −2) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 73 ± 8 | 66 ± 7* | −8 (−13 to −3) | 70 ± 8 | 64 ± 6* | −10 (−11 to −5) | 75 ± 7 | 68 ± 7* | −8 (−14 to −2) |

| PP (mmHg) | 58 ± 14 | 54 ± 13* | −3 (−15 to 4) | 55 ± 17 | 52 ± 14 | −5 (−14 to 2) | 60 ± 13 | 56 ± 12 | −2 (−14 to 6) |

| MPAP (mmHg) | 25 ± 6 | 22 ± 6* | −9 (−13 to −5) | 26 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | −11 (−15 to −6) | 24 ± 7 | 22 ± 7* | −7 (−10 to −5) |

| SVRI (mmHg min m2/L) | 21.1 ± 6 | 19.4 ± 4.9* | −7 (−14 to 0) | 20.6 ± 5.2 | 19.3 ± 4.3* | −3 (−9 to 0) | 21.5 ± 6.7 | 19.5 ± 5.5* | −10 (−15 to −1) |

| PVRI (mmHg min m2/L) | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 1.3 | 1 (−2 to 8) | 3.2 ± 1 | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 0 (−2 to 9) | 3.4 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 1.7 | 1 (−3 to 5) |

| VRRI (mmHg min m2/L) | 6.7 ± 2.6 | 5.7 ± 1.8* | −12 (−25 to −5) | 7.2 ± 3.2 | 5.5 ± 1.9* | −22 (−32 to −12) | 6.3 ± 2.2 | 5.8 ± 1.8* | −7 (−16 to 1)† |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | −2 (−6 to 5) | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | −1 (−6 to 2) | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | −2 (−6 to 7) |

| SVI (mL/m2) | 37 ± 8 | 36 ± 9 | −2 (−7 to 2) | 35 ± 8 | 33 ± 8 | −2 (−7 to 0) | 38 ± 8 | 37 ± 9 | −2 (−6 to 5) |

| UO (mL/kg/h) | 0.92 ± 0.27 | 1.03 ± 0.34* | 13 (7 to 24) | 0.82 ± 0.24 | 0.95 ± 0.30* | 22 (2 to 27) | 0.99 ± 0.27 | 1.09 ± 0.36* | 12 (8 to 15) |

CI, cardiac index; CVA, central venous pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HFmrEF, heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PAWP, pulmonary artery wedge pressure; Pmsf, mean systemic filling pressure; PP, pulse pressure; PVRI, pulmonary vascular resistance index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SVI, stroke volume index; SVRI, systemic vascular resistance index; VRRI, the resistance index to venous return; UO, Urine output.

P < 0.05 for comparison between pre‐ and post‐ nesiritide.

P < 0.05 for comparison between patients with HFrEF and HFpEF.

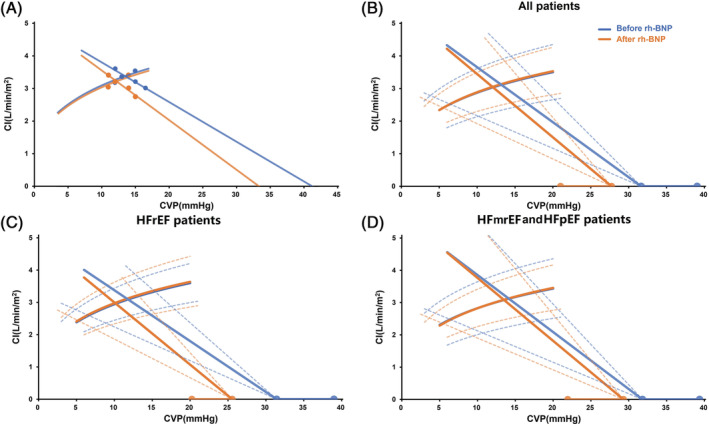

Frank‐Starling and venous return curves

The instant effects of rh‐BNP on the function of CO and venous return are shown in Figure 2 . Three points induced by postural changes and four points by PEEP gradients were used to depict the CO function (Frank‐Starling) and venous return (Guyton) curves before and after the use of rh‐BNP (Figure 2A). The averaged effects of rh‐BNP are presented in Figure 2B where (i) the CO function curves did not change after rh‐BNP treatment; (ii) the intercept of the X‐axis and the inverse of the slope of the venous return curves decreased significantly. Prior to rh‐BNP, the Pmsf was 32 ± 7 mmHg, which was much higher than the values for patients without heart failure (16 to 23 mmHg). 29 , 30 , 31 After rh‐BNP treatment, this value reduced to 28 ± 7 mmHg (P = 0.002). Besides, the parameter for the resistance to venous return, VRRI, was also significantly reduced from 6.7 ± 2.6 to 5.7 ± 1.8 mmHg min m2/L (P = 0.002) and the reduction in VRRI and SVRI was 12% (IQR 5 to 25) and 7% (IQR 0 to 14), respectively. Furthermore, the reduction in venous return pressure gradient (Pmsf‐CVP) was 13% (IQR 1 to 23), which was very close to the VRRI.

Figure 2.

The cardiac output function and venous return curves. (A) An example of plotting venous return curves and cardiac output function curves. (B, C and D) The instant effects of rh‐BNP on cardiac output function and venous return function curves for all patients, patients with HFrEF or HFmrEF and HFpEF. The blue and orange lines indicated the status before and after using rh‐BNP. The solid lines or curves were the averaged effects while the dashed lines and line segments represented the standard deviation. CI, cardiac index; CVP, central venous pressure; HFmrEF, heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; rh‐BNP, recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide.

Comparison between patients with HFrEF and HFmrEF or HFpEF

The instant haemodynamic changes were more significant in HFrEF patients when compared with HFmrEF and HFpEF patients (Table 2 & Figure 2C,D). The main haemodynamic parameters, such as CVP, MAP, CI, SVI, SVRI, MPAP, and PVRI, showed a similar tendency in both subgroups. Despite very close Pmsf (31 ± 8 vs. 32 ± 8 mmHg, P = 0.841) before using rh‐BNP, Pmsf decreased more dramatically in HFrEF patients [percent change: −18% (IQR 22 to −13) vs. −10% (IQR 15 to −4), P = 0.022]. The reduction in the VRRI was also greater in patients with HFrEF [percent change: −22% (−32 to −12) vs. −7% (−16 to 1), P = 0.026]. Moreover, in patients with HFrEF, the reduction in the VRRI was much larger than that in the SVRI [percent change: −22% (−32 to −12) vs. −3% (−9 to 0), P = 0.041].

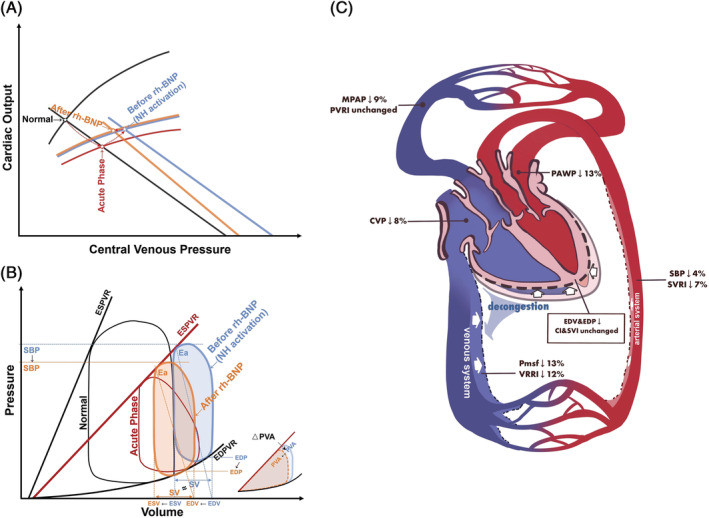

Comprehensive interpretation of the role of recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide on systemic circulation

Combined with the method of pressure–volume analysis, 32 we made rational extrapolations for the comprehensive effects of rh‐BNP on systemic circulatory system (Figure 3A,B). During the immediate aftermath of heart injury, the cardiac function curve fell to its lowest point and the P‐V loop narrowed and shifted to the right and downwards (red curves), resulting in low CO and SBP but high end‐diastolic volume (EDV) and filling pressures. After this, neuro‐hormonal activation caused a modest increase in contractility and shifted the venous return curve significantly rightward (blue curves). This led to a compensatory increase in SBP at the expense of further increasing EDV and filling pressure, the potential energy (represents the residual energy stored in the myofilaments at the end of systole that is not converted to external work 32 ) and pressure–volume area (linearly related to total mechanical energy 33 ) increased accordingly. After the use of rh‐BNP, the CO function curve remained unchanged while both the Pmsf and VRRI decreased, shifting the working condition of the heart to the orange point with the same CO but lower CVP. However, the P‐V loop moved left and downwards lowering EDV and end‐systolic volume, 25 thus reducing the potential energy and pressure–volume area, at a price of slightly decreased SBP.

Figure 3.

The schematic picture of the mechanism of rh‐BNP's effects. (A and B) Different stages of acute heart failure and receiving rh‐BNP illustrated by cardiac output function–venous return relation and pressure–volume relation. The black, red, blue, and orange curves indicate normal, acute phase, before and after rh‐BNP, respectively. (C) The comprehensive effects of rh‐BNP. CI, cardiac index; CVP, central venous pressure; EDP, end‐diastolic pressure; EDPVR, end‐diastolic pressure–volume relationship; EDV, end‐diastolic volume; ESV, end‐systolic volume; ESVPR, end‐systolic pressure–volume relationship; MPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PAWP, pulmonary artery wedge pressure; Pmsf, mean systemic filling pressure; PVA, pressure–volume area; PVRI, pulmonary vascular resistance index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVRI, systemic vascular resistance index; VRRI, venous return resistance index.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the instant therapeutic effects of rh‐BNP on CO and venous return function in mechanically ventilated post‐operative heart failure patients. Our work demonstrated that rh‐BNP (i) did not alter the CO function (ii) but ameliorated the venous return function by decreasing the systemic filling pressure and resistance to venous return.

Effects of recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide on cardiac output function

It is widely acknowledged that BNP is not an inotrope 4 , 11 and in our study, neither the value of CO nor the CO function curve changed after infusion of rh‐BNP. This finding is consistent with other studies based on cardiac surgical population. 13 , 14 Moreover, a physiological study performed on patients who underwent left heart catheterization and echocardiography demonstrated that rh‐BNP did not improve cardiac contractility or functional parameters (CO, LVEF and ‐dP/dt, etc.). 34 However, a number of earlier stage researches have reported an increment in CO 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 and of note, the population in these studies had higher baseline blood pressure or vascular resistance, indicating an overhigh afterload, which was probably due to the enhanced autonomic tone and over‐activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system in the acute phase of heart failure. 35 Under this circumstance, reducing vascular resistance may shift upwards the CO function curve and therefore improve CO. On the contrary, among the cardiac surgical population, we should not anticipate that the use of rh‐BNP will improve CO.

Effects of recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide on venous return function

In the acute phase of heart failure, the compensatory mechanism transferred unstressed volume (mainly in the venous system 36 ) to stressed volume (functional circulating blood volume) in order to ameliorate the reduction of CO, which contributes to a congestive state. 32 , 37 rh‐BNP has a widely recognized physiological effect of reducing cardiac filling pressures (both CVP and PAWP) and by studying these post‐cardiotomy heart failure patients, we found that rh‐BNP could also significantly reduce Pmsf and VRRI. Moreover, rh‐BNP induced a greater decline in VRRI than in SVRI (especially among HFrEF patients), implying a greater increase in venous compliance. In contrast, nitroglycerin, a vasodilator frequently used in heart failure treatment, only reduced the Pmsf rather than the VRRI. 38 It is also important to note that, according to the VAMC study, nitroglycerin caused a delay and smaller decline in CVP and PAWP than rh‐BNP. 5

Effects of recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide on pulmonary circulation system

In the present study, we also observed a significant decrease in pulmonary artery pressure, which may introduce a misconception that rh‐BNP can exert similar effects to those of pulmonary hypertension drugs. However, we should note that there is actually no significant change in pulmonary circulatory resistance and that the reduction in pulmonary artery pressure is more attributable to a reduction in backward left atrial pressure. Several well‐performed physiological studies published in recent years have also confirmed that rh‐BNP reduces pulmonary artery pressure but does not alter pulmonary circulatory resistance. 25 , 26 , 34

Effects of recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide on short‐term urine output

Negative fluid balance may also have an effect on filling pressure, and this study also found a slight degree of acute increase in UO, although it was not the primary study objective. The actual fluid balance during the 90 min measurement period was very small, so this small increase in UO cannot explain the dramatic effect on venous return with rh‐BNP. There is still some controversy about the diuretic effect of rh‐BNP. Elkayam et al. found that although rh‐BNP increased renal artery diameter, there was no significant increase in renal blood flow due to reduced perfusion pressure. 26 The NAPA study showed that even a low dose of rh‐BNP regimen (0.01 μg/kg/min without bolus for at least 24 h) could lead to an increase in UO. 14 Another study performed on a paediatric population also confirmed that the use of rh‐BNP was associated with a trend toward a significant increase in UO. 39 However, Gottlieb et al. suggested that a greater UO during the use of rh‐BNP was more attributable to concomitant diuretic use. 40

A summary of the comprehensive effects of recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide on the circulatory system

To help to elucidate the instant effects of rh‐BNP on circulatory pressure and volume distribution, we plotted a diagram of circulatory system changes as seen in Figure 3 C and found (i) slight dilatation of the arterial system (small reductions in SBP and SVRI); (ii) significant dilatation of the venous system (larger reduction in Pmsf and VRRI), which increased venous capacity to buffer the redundant blood volume; (iii) unchanged CO with reduced heart volume (preload) 25 and filling pressures, as a result of a gradual transfer of the blood volume from the overfilled heart to the enlarged venous bed; and (iv) blood volume returning to the heart did not increase. As we know, the venous return = pressure gradient/resistance. In this study, the pressure gradient showed a similar or greater decline when compared with the VRRI, leading to a balanced or very small reduction in venous return; and (iv) unchanged pulmonary vasculature despite a decreased pulmonary pressure.

The main function of the venous system is to contain blood (the main blood reservoir) and to collect blood flowing through the tissues and transport it back to the heart. 22 For patients with post‐cardiotomy CHF, we postulate that the rh‐BNP could rapidly transfer the overfilled blood from the heart to the venous bed, thereby reduce filling pressures and improve the workload of heart. The excess fluid in the venous bed is then excreted gradually by the diuretic effect of rh‐BNP, or by supplementing diuretics. Therefore, we recommend against prophylactic or empiric use of rh‐BNP in cardiac surgical population. Conversely, rh‐BNP should only be administrated in patients with evidence about congestion.

Limitations

There are several limitations in our study. Firstly, it was conducted in a single centre and cardiac surgical population. Secondly, the CVP or PAWP were not very high in some patients, however, the Pmsf was above 20 mmHg for all the study population. Thirdly, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation under deep sedation allowed us to perform the measurements required for this study; however, it may limit the range of study population. Fourth, we did not measure the diameter of the heart which may represent a deficiency in the study design. Finally, based on our technical conditions, we were not able to measure the P‐V loop directly. However, based on previous studies, we can still make a reasonable extrapolation about the heart volume changes.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that rh‐BNP might ameliorate venous return function (reducing both systemic filling pressure and resistance to venous return) rather than CO function in mechanically ventilated post‐cardiotomy heart failure patients. This study provides a more detailed interpretation of rh‐BNP's effects on haemodynamic profiles in CHF patients, which will facilitate clinicians to make the decision regarding the appropriate use of rh‐BNP.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This article was supported by grants from Clinical Research Project of Zhongshan Hospital (2020ZSLC38 and 2020ZSLC27), Research Funds of Zhongshan Hospital (2019ZSYXQN34), Smart Medical Care of Zhongshan Hospital (2020ZHZS01), Project for elite backbone of Zhongshan Hospital (2021ZSGG06), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (20ZR1411100 and 21ZR1412900), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (20DZ2261200), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070085).

Luo, J. , Zhang, Y.‐J. , Huang, D. , Wang, H. , Luo, M. , Hou, J. , Hao, G. , Su, Y. , Tu, G. , and Luo, Z. (2022) Recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide ameliorates venous return function in congestive heart failure. ESC Heart Failure, 9: 2635–2644. 10.1002/ehf2.13987.

Jing‐chao Luo and Yi‐Jie Zhang contributed equally to this article and are co‐first authors.

Contributor Information

Guo‐wei Tu, Email: tu.guowei@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Zhe Luo, Email: luo.zhe@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

References

- 1. Mebazaa A, Pitsis AA, Rudiger A, et al. Clinical review: practical recommendations on the management of perioperative heart failure in cardiac surgery. Crit Care. 2010; 14: 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baughman KL. B‐type natriuretic peptide—a window to the heart. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347: 158–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Potter LR, Yoder AR, Flora DR, Antos LK, Dickey DM. Natriuretic peptides: their structures, receptors, physiologic functions and therapeutic applications. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009: 341–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hobbs RE, Mills RM. Therapeutic potential of nesiritide (recombinant b‐type natriuretic peptide) in the treatment of heart failure. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 1999; 8: 1063–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Publication Committee for the VI . Intravenous nesiritide vs nitroglycerin for treatment of decompensated congestive heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002; 287: 1531–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang Y, Duan Y, Yan J, et al. Impact of nesiritide infusion on early postoperative recovery after total cavopulmonary connection surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. 2018; 39: 1598–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Costello JM, Dunbar‐Masterson C, Allan CK, et al. Impact of empiric nesiritide or milrinone infusion on early postoperative recovery after Fontan surgery: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2014; 7: 596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ejaz AA, Martin TD, Johnson RJ, et al. Prophylactic nesiritide does not prevent dialysis or all‐cause mortality in patients undergoing high‐risk cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009; 138: 959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hobbs RE, Miller LW, Bott‐Silverman C, et al. Hemodynamic effects of a single intravenous injection of synthetic human brain natriuretic peptide in patients with heart failure secondary to ischemic or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1996; 78: 896–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abraham WT, Lowes BD, Ferguson DA, et al. Systemic hemodynamic, neurohormonal, and renal effects of a steady‐state infusion of human brain natriuretic peptide in patients with hemodynamically decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 1998; 4: 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mills RM, LeJemtel TH, Horton DP, et al. Sustained hemodynamic effects of an infusion of nesiritide (human b‐type natriuretic peptide) in heart failure: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Natrecor Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 34: 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colucci WS, Elkayam U, Horton DP, et al. Intravenous nesiritide, a natriuretic peptide, in the treatment of decompensated congestive heart failure. Nesiritide Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343: 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salzberg SP, Filsoufi F, Anyanwu A, et al. High‐risk mitral valve surgery: perioperative hemodynamic optimization with nesiritide (BNP). Ann Thorac Surg. 2005; 80: 502–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mentzer RM Jr, Oz MC, Sladen RN, et al. Effects of perioperative nesiritide in patients with left ventricular dysfunction undergoing cardiac surgery: the NAPA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49: 716–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Behera SK, Zuccaro JC, Wetzel GT, Alejos JC. Nesiritide improves hemodynamics in children with dilated cardiomyopathy: a pilot study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009; 30: 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Han JC, Loiselle D, Taberner A, Tran K. Re‐visiting the Frank‐Starling nexus. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2021; 159: 10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guyton AC. Determination of cardiac output by equating venous return curves with cardiac response curves. Physiol Rev. 1955; 35: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sopek Merkas I, Sliskovic AM, Lakusic N. Current concept in the diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of patients with congestive heart failure. World J Cardiol. 2021; 13: 183–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Voors AA, Angermann CE, Teerlink JR, et al. The SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: a multinational randomized trial. Nat Med. 2022; 28: 568–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ostermann M, Bellomo R, Burdmann EA, et al. Controversies in acute kidney injury: conclusions from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) conference. Kidney Int. 2020; 98: 294–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, et al. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation‐Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA. 2003; 289: 2983–2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guyton AC. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology, International edition ed. Elsevier; 2016. p 250. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luo JC, Su Y, Dong LL, et al. Trendelenburg maneuver predicts fluid responsiveness in patients on veno‐arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Intensive Care. 2021; 11: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Persichini R, Silva S, Teboul JL, et al. Effects of norepinephrine on mean systemic pressure and venous return in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2012; 40: 3146–3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Efstratiadis S, Michaels AD. Acute hemodynamic effects of intravenous nesiritide on left ventricular diastolic function in heart failure patients. J Card Fail. 2009; 15: 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elkayam U, Akhter MW, Liu M, Hatamizadeh P, Barakat MN. Assessment of renal hemodynamic effects of nesiritide in patients with heart failure using intravascular Doppler and quantitative angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008; 1: 765–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cholley B, Caruba T, Grosjean S, et al. Effect of levosimendan on low cardiac output syndrome in patients with low ejection fraction undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting with cardiopulmonary bypass: the LICORN randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017; 318: 548–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021; 42: 3599–3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maas JJ, de Wilde RB, Aarts LP, Pinsky MR, Jansen JR. Determination of vascular waterfall phenomenon by bedside measurement of mean systemic filling pressure and critical closing pressure in the intensive care unit. Anesth Analg. 2012; 114: 803–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maas JJ, Pinsky MR, Geerts BF, de Wilde RB, Jansen JR. Estimation of mean systemic filling pressure in postoperative cardiac surgery patients with three methods. Intensive Care Med. 2012; 38: 1452–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berger D, Takala J. Determinants of systemic venous return and the impact of positive pressure ventilation. Ann Transl Med. 2018; 6: 350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brener MI, Rosenblum HR, Burkhoff D. Pathophysiology and advanced hemodynamic assessment of cardiogenic shock. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2020; 16: 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Araki J, Shimizu J, Mikane T, et al. Ventricular pressure‐volume area (PVA) accounts for cardiac energy consumption of work production and absorption. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998; 453: 491–497 discussion 497‐498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shah SJ, Michaels AD. Acute effects of intravenous nesiritide on cardiac contractility in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2010; 16: 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Adams KF Jr. Pathophysiologic role of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems in heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004; 61: S4–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sorimachi H, Burkhoff D, Verbrugge FH, et al. Obesity, venous capacitance, and venous compliance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Whitehead EH, Thayer KL, Sunagawa K, et al. Estimation of stressed blood volume in patients with cardiogenic shock from acute myocardial infarction and decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Imai Y, Ito H, Minatoguchi S, et al. The effects of phentolamine and nitroglycerin on right‐sided hemodynamics in cardiac patients can be explained by a shift of the systemic venous return curve and right‐ventricular output curve. Jpn Circ J. 1992; 56: 801–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bronicki RA, Domico M, Checchia PA, Kennedy CE, Akcan‐Arikan A. The use of nesiritide in children with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017; 18: 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gottlieb SS, Stebbins A, Voors AA, et al. Effects of nesiritide and predictors of urine output in acute decompensated heart failure: results from ASCEND‐HF (acute study of clinical effectiveness of nesiritide and decompensated heart failure). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62: 1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]