Abstract

As of October 2021, Romania is one of the world’s most affected countries by Covid-19 pandemic, and this occurs on the background of a very slow rate of vaccination. Drawing on the sociology of storytelling, this article highlights various narratives that make the vaccination campaign in Romania difficult. Based on a case study on Romanian official vaccination page “RO Vaccinare,” a thematic analysis on six official narratives and subsequent 137 comments post on the official page highlighted both pro-vaccination narratives and anti-vaccination narratives. The two main narratives reflect different persuasive strategies, so the role of communication experts is vital in avoiding other further mis/disinformation. For example, pro-vaccination narratives repeatedly call for education as the most important variable, given that the detachment from conspiracy theories requires a certain level of socialization in this regard. In addition, the ‘science versus religion’ dichotomy is frequently discussed, with religion being seen as an obstacle to awareness of the role of a vaccination campaign. On the other hand, the motivations invoked in the anti-vaccination narratives discuss the vaccine as an ‘experimental serum,’ while the doctors who administer it are considered ‘killers.’ Also, some of the narratives in this category consider religion to be above science in terms of public health.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43545-022-00427-3.

Introduction

Narratives are a crucial component of everyday life, as they reflect various aspects (social, cultural, economic, political) that go beyond mere discursive rhetoric. The existence of these narratives is all the more important as they accompany individuals even in difficult global contexts, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. The severity of this phenomenon is all the more visible in Eastern Europe, given that only 33% of Romanian adults were vaccinated against Covid-19 by early October 2021, while the average in EU countries is 72% (McGrath 2021). Thus, while vaccine hesitancy is attributed in some studies to the spread of false information (Boghardt 2009; Scannell et al. 2021)—either unintentionally (misinformation) or intentionally (disinformation)—it is observed that individuals tend to adopt their own narratives in response to the vaccination context.

The strategy adopted by RO Vaccinare, the Romanian official page dedicated to vaccination against Covid-19, proposes a different method from the standard messages urging vaccination. In the last two months in particular, the strategy used was to expose the different narratives that vaccinated individuals bring into discussion. Often, the purpose of these messages is not explicitly mentioned, so it is the receiver who must assign meaning to them (Robinson 1981). In such cases, recent studies state that exposure to positive messages, whether subtle or not, increases the chances of convincing individuals to get vaccinated (Caserotti et al. 2021; Capasso et al. 2021).

Thus, the purpose of this research is to observe to what extent the main themes observed in the comments on the Facebook page “RO Vaccinare” reflect, in fact, different ideological and / or socio-cultural components, inscribed in a sociology of storytelling. The structure of this article is as follows: first, the role that narratives have in sociology will be highlighted, along with the main narratives that previous studies identify in relation to vaccination. After that, recent characteristics and statistics of the vaccination campaign in Romania will be mentioned, followed by a thematic analysis of the main topics present on the page RO Vaccinare, the official Facebook group of the vaccination campaign, in response to the official strategy to expose persuasively different personal narratives in the digital environment. Then, the discussion section aims to report on the extent to which the vaccination campaign in Romania is facing similar problems of previous vaccination campaigns, along with some indications on overcoming the stalemate on the poor results of the vaccination campaign in Romania.

Storytelling during the infodemic

Narratives during uncertain times seem to highlight an adjacent role, frequently studied in the social and communication sciences: the role of persuasion. Thus, it is no coincidence that narratives are not just simple rhetorical forms, but also ideological constructions and elements of collective action (Polletta 2015). In this article, narratives and stories are used interchangeably, given that the studies that used them differently did so for very distinct reasons: the level of discursive homogeneity, the level of truth of what is said, or the level of coherence identified between different communities (Maines 1993). Following the explanation offered by Polletta (2011, 2015), it is found that whether these narratives are true or not is less important. It is no coincidence that elements such as universal categories and scientific evidence are also narratives, i.e.: “… moralizing accounts whose claim to truth rested their verisimilitude rather than their veracity” (Polletta 2011: 113).

In addition, empathetic narratives, such as those that provoke fear, are more likely to be assimilated. It is no coincidence that in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, multiple narratives designed to discredit science and health experts lead to an increase in vaccine hesitancy (Chou and Budenz 2020). In many states, pandemic discourses are assimilated by political narratives, so the emotions such as fear and anger seem to correlate with broader attitudes, such as racism, xenophobia, or homophobia (Lwin et al. 2020; Funk et al. 2020).

For most of us, narratives during the pandemic can be assessed as either true or false, and such a trend shows that the Covid-19 pandemic has accentuated a polarization that already exists in society. We already know that such narratives assumed and assimilated in uncertain times lead to an increase in the degree of intimacy between the individual and his favorite narratives (Maly et al. 2012). For this reason, one should know how to handle a sensitive situation, in which we must tell someone that he has erroneous information, given that trying to overturn someone's value system causes obvious defensive reactions. Such situations would have undesirable consequences, such as those described by Dan and Dixon (2021: 676): “… a person convinced to be in a possession of the ultimate truth, but who is frequently informed that they are wrong, might engage in downward social comparisons with those who reject and challenge their beliefs”.

Even the existence of institutions depends on a certain storytelling, and the institution of vaccination is no exception, as we will see later. As mentioned, a successfully conceived narrative is one that knows how to appeal to different emotions when needed. For example, analyses of previous vaccines show that between 76 and 88% of anti-vaccination websites appealed to different emotions of readers, presenting vaccines either as a restriction of freedoms or as a biological intervention full of side effects (Bean 2011; Kata 2010). Although for us some narratives sound absurd from the outset, the same does not happen in the case of individuals who assume those narratives. This issue is also raised by Polletta (2011: 119): “And why are groups unable to discredit that narrative if it is untrue? A plausible answer is that the dominant story meshes with deeply held ideological values”. Since any socially constructed reality shows us that an ideology appears when: “… a particular definition of reality comes to be attached to a concrete interest” (Berger and Luckmann 1967), one might ask how the ideological profiles of the main narratives look like, in relation to the vaccine. As we see during this Covid-19 pandemic, the increased participation on social media has created a sort of “echo chambers,” which encourages ideological isolation from the opposite perspectives, which maintains medical epidemics precisely through fake news (Gunaratne et al. 2019). Vaccination narratives that appeared in the public space may determine a greater resilience to persuasion, given the fact that it involves a situation with ample personal valences (Scannell et al. 2021). In addition, it is observed that anti-vaccine attitudes have an increased propensity especially in those who report low confidence in the government (Larson et al. 2018).

As it was mentioned earlier, the fact that the narrative is true or false is not so important. However, what matters most visibly is to: “… have events that follow along the lives of generic plots” (Polletta and Callahan 2019: 57). Also, narratives have to be allusive, so that their intention is understood by both the sender and the receiver, even if it is not expressly stated. This allusiveness is important because, in the case of narratives, it establishes a more or less fragile boundary between history and memory. It is no coincidence that the concept of “nostalgia narratives” (Maly et al. 2012), through which one’s own identity, is constructed through selective versions of the past. Thus, the most important narratives are those that the sender will consider relevant for the meaning of the discussion.

The wording of a narrative message becomes increasingly important, especially in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, as the reactions of social media users depend on such wording. In the vaccination context, recent studies highlights the discourses focused on “gain frames” versus those focused on “loss frames,” arguing that individuals’ attention is increased in cases where the negative consequences, losses of an action, or lack thereof are mentioned in particular (Unkelbach et al. 2020). Other authors also add the variable related to psychological uncertainty (Huang and Liu 2021) as a suggestive predictor, explaining that the loss frame works better in conditions of high uncertainty. Sociologists might ask to what extent the uncertainty component is actually as inward as described in the study. For many social scientists interested in how different narratives circulate, they seem to follow not only a kind of social contagion, but even a kind of communication environment in which individuals tend to assume experiences they have never lived. Or, as Polletta and Callahan would say (2019: 64): “Sociological accounts have revealed another dynamic: people’s sense of personal experience may encompass experiences that are not their own.” Regarding storytelling during Donald Trump's era, the aforementioned study shows that individuals judge various contemporary global issues, such as global warming, the problem of immigrants or racial disparities, in accordance with their partisan views. The Romanian context shows that even Covid-19, which had to be considered strictly a medical problem, acquires as much political and ideological values as possible.

The Romanian context and its infodemic

Certainly, narratives published in the social media influence vaccination campaigns in all countries of the world, and Romania is no exception. According to data from February 2021, when the vaccine was available only for the essential categories of population, 7% of Romanians had mentioned that they had already been vaccinated, while 51% of the sample mentioned that they would be vaccinated as soon as appointments were available (IPSOS 2021). However, things seem to have taken a visible turn in vaccination in Romania, given that in October 2021, only 33% of Romanians were vaccinated, which is why some media articles talk about the existence of “Two Europes”: on the one hand, Western countries that have exceeded the 70% vaccination threshold and, on the other hand, Eastern European countries, such as Romania and Bulgaria (McGrath 2021). This situation confirms certain taxonomies on the topic of vaccination, where it is highlighted that an important segment of the populations of each country would be vaccinated, but they are also thinking about the potential side effects. Thus, Vulpe and Rughiniș (2021) identifies the so-called trade-off typology, representing approximately 30% of the data collected at European level and highlighting the intermediate category of individuals who are aware of the effectiveness of the vaccine, but who are afraid of the possible side effects that could occur.

Thus, it is observed that the “adverse effects” narratives have widely circulated in the public space, and an important role belongs to new media technologies, which propagate a lot of information with astonishing speed, without applying any filters to correct potential conspiracy theories. In this sense, previous studies on vaccination campaigns in Romania show that some narratives become recurrent, regardless of the diseases for which they were designed. For example, qualitative research on Romanian mothers’ discourses about vaccinating their daughters against Human Papillomavirus (HPV) identified a variety of reasons against vaccination: girls’ infertility appears to be the main cause of anxiety, followed by reasons such as humans as “guinea pigs,” or various conspiracy theories such as the vaccine as a weapon to reduce the world’s population (Crăciun and Băban 2012). In addition, various associations among Romanian samples indicate strongly negative correlations between understanding science and trust in pseudosciences such as astrology (Obreja 2021), along with other negative correlations between the very high level of religiosity in Romania, and the ability to respond to elementary questions of science (Vlăsceanu et al. 2010).

Conspiracy theories remain active even in the context of the Covid-19 vaccine, but this time they are also encouraged at the political level. In this sense, the far-right party AUR [Romanians Unity Alliance] enters parliament with the December 2020 elections, and their anti-system and anti-EU ideas are publicly exposed with visible intensity. AUR has exceeded the electoral threshold amid a very low turnout, and strong support from Romanians in the diaspora (Ulceluse 2020), due to the substantial financial investments that the party has made on their Facebook page. Examples of conspiracy theories are numerous, and in this case, it is worth mentioning the public appearances of Diana Șoșoacă, AUR senator until her recent exclusion from the party, who repeatedly mentioned that the Covid vaccine causes sterility for three generations, and too few were asking, in this context, how the second and third generation could appear (Rusu 2021). Another conspiracy theory that soon went viral was launched by an abbot of a monastery in eastern Romania, who said that those who get vaccinated will have scales on their skin and become zombies (Pricop 2021).

Narratives exaggerated to the extreme have the advantage of being memorized for longer periods of time and, in addition, they enjoy increased public attention from media institutions. Or, in the words of Polletta and Callahan (2019: 58): “… the exaggerated stories gained wide publicity, and were told and retold in newspapers, magazines, television talk shows, sit-coms, and movies.” Thus, there are multiple concerns when conspiracy messages circulate at a high intensity during a pandemic, especially when this has serious medical consequences.

Methodology

Within this qualitative content analysis, six narratives and 137 subsequent comments were analyzed, from the RO Vaccinare, the official Facebook page for the Covid-19 vaccination campaign in Romania. Of these, 79 comments (57%) were pro-vaccination messages, while 58 (43%) were anti-vaccination messages. None of the comments identified were completely neutral regarding vaccination, which is why no intermediate narrative category was included. The six posts were published between September 26 and October 10, 2021, and the most popular comments (based on the total number of reactions) were selected. This direction follows previously established patterns, according to which “fake news” and conspiracy narratives are more appreciated and, consequently, more distributed on social media (Davies 2016). Currently, content analysis is widely used in fields such as communication, sociology, psychology, or business (Neundorf 2002) and is an advantageous method especially in the context of quantifying phenomena or patterns (Krippendorff 1980). The grouping of the obtained comments respects the rigors of an inductive content analysis, so an important step is the generation of open codes. These codes facilitate the formation of appropriate categories, given that: “When formulating categories by inductive content analysis, the researcher comes to a decision, through interpretation, as to which things to put in the same category” (Elo and Kyngäs 2008: 111). Open codes and related topics were set up based on two research questions:

RQ1. What are the recurring themes in the comments on vaccination against Covid-19, on “RO Vaccinare” Facebook page?

RQ2. To what extent do these themes appear in response to the official narratives mentioned there?

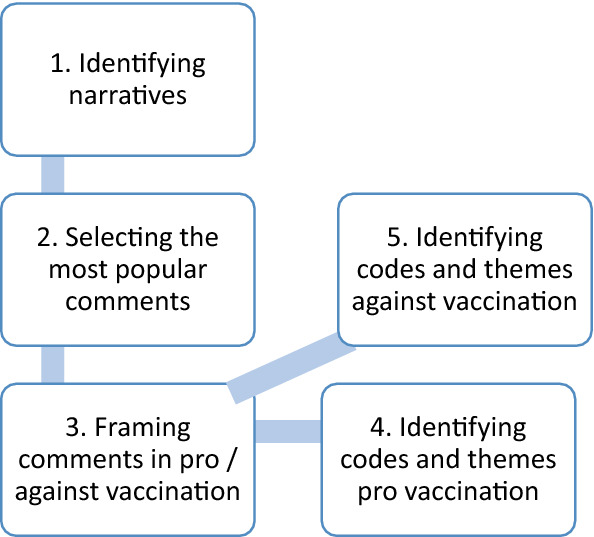

Since an inductive content is favorable for a qualitative data generation, a thematic analysis has a common background with grounded theory. A notable feature of the inductive approach is that: “… is therefore a process of coding the data without trying to fit it into a preexisting coding frame, or the researcher’s analytic preconceptions” (Braun and Clarke 2006: 83) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Main steps followed in the inductive open coding process

By the fact that the six narratives involve individuals from different professional categories: doctors, citizens, vaccination campaign coordinator, etc., it is observed that a concrete intention is to activate positive emotions among commentators, appealing to empathy, understanding, and trust in the role of the vaccine (Bavel et al. 2020). As will be seen, each narrative requires a specific type of approach, and the personalized nature of the messages officially posted on RO Vaccinare shows that capturing readers' interest through persuasive tactics is a recurring motive in studies interested in the communicational environment.

Findings: six official narratives

The six chosen narratives exposed on the official page highlight a frequent strategy of activating the readers’ emotions, especially through positive reactions such as empathy, by caring about the problems of others. However, as will be seen in the comments, not all will have the same effect on users. For example, Narrative 1 chosen belongs to an ICU [Intensive Care Unit] primary physician at the Colentina Hospital (Bucharest). As she mentions, most people who come to the ICU are unvaccinated, because they do not believe in the vaccine or in the doctors. She gives the example of Western countries that have almost empty ICU sections, because they have between 75 and 95% vaccinated. She also rhetorically asks: “I wonder – do I believe in doctors now? Wasn’t it easier to get vaccinated?”.

Narrative 2 on RO Vaccinare describes the experience of a well-known TV producer in Romania, who states that he really wants to smell and taste the coffee and that he can continue to do so, thanks to the vaccine. Finally, the author is ironic toward those who get their information about the vaccine on Facebook: “If you have finished medicine on Google or Facebook, please refrain from comments.” Narrative 3 describes the experience of another ICU physician, from Saint Pantelimon Hospital. She describes that she had sixty Covid patients, 95% of whom are unvaccinated. To draw attention to the gravity of the situation, she says: “They only realize the seriousness of the situation when they arrive at the hospital. We are in a situation where patients, unfortunately, have only now understood, they really take off their CPAP masks and shout: << Vaccinate us! >> What should we vaccinate now? It’s too late”. In his message, he demands understanding from Romanians, to believe in doctors and science and not to listen to all the conspiracy theories on the internet. He also calls for vaccination to reduce pressure on the medical system: “It is a pity that the place of safety is overshadowed by the voices of those who encourage and roll conspiracy theories, without foundation, without scientific basis…”. Narrative 4 is a message from Valeriu Gheorghiță, the military doctor responsible nationally for the vaccination campaign. He also blames the declining interest in vaccination on online conspiracy theories, saying that: “It is a pity that the place of safety is overshadowed by the voices of those who encourage and roll conspiracy theories, without foundation, without scientific basis, but which, through the approach, destabilizes opinions and generates insecurity and hesitation.” This antithesis between science and conspiracy is used to call for an increased trust in medical authorities in the context of the vaccination campaign.

Narrative 5 belongs to a 72-year-old man who attracted public attention by the fact that he came by bicycle from his house to the vaccination center, to be vaccinated with his favorite serum, Moderna. As concluded by the RO Vaccinare staff on his behalf: “If you really want something, you can do it with determination and a smile! We thank him for coming to us this morning and we wish him good health!”. Narrative 6 belongs to another citizen, who has multiple comorbidities, as he himself lists them in the post: “… morbid obesity, reactive hypercorticism, hypothyroidism, hypertension, operated hepatic cyst.” He mentions that his complete vaccination made the Covid virus feel like a cold for ten days. Finally, his wish is: “If you want those around you to live, get vaccinated.”

Main themes

Unlike previous studies that highlighted a visible category of undecided respondents regarding vaccination, the comments analyzed in this article show a more pronounced polarization among Romanian users. In this regard, the 137 comments analyzed reflect from the outset either pro-vaccination narratives or anti-vaccination narratives. All these are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main themes and the related open codes

| Narrative | Themes | Suggestive open codes |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Pro-vaccination narrative (57.5% of all comments) |

1.1 Lack of education among Romanians | 1.1a.Conspirationists with few classes completed (15% of all commentaries) |

| 1.1b .Functional illiterates (6.5%) | ||

| 1.1c .We and Bulgarians are the weakest (3%) | ||

| 1.2 Unvaccinated should avoid hospitals | 1.2a. Pay your own hospitalization (3%) | |

| 1.2b. Do not come if you don’t trust doctors (5%) | ||

| 1.2c. Treat yourself at home with natural products (1.5%) | ||

| 1.3 Science versus God | 1.3a. Priests' propaganda (1.5%) | |

| 1.3b. I believe doctors, not Facebook or TV (11%) | ||

| 1.3c. Vaccine worked very well (9%) | ||

| 1.4 Communism nostalgia | 1.4a. .Vaccination was mandatory (2%) | |

|

2. Anti-vaccination narrative (42.5% of all comments) |

2.1 “They” are paid to promote vaccination | 2.1a. Doctors are paid (3.5%) |

| 2.1b. Other citizens are paid (4%) | ||

| 2.2 Doctors as killers | 2.2a. The other conditions are ignored (3.5%) | |

| 2.2b. Patients are killed with too much oxygen (1.5%) | ||

| 2.3 Vaccine as experimental serum | 2.3a. Why to sign an affidavit? (3%) | |

| 2.3b. Vaccinated ones are guinea pigs (5%) | ||

| 2.3c. Long-term effects (6.5%) | ||

| 2.3d. It is worse for vaccinated ones (7.5%) | ||

| 2.3e. They are forcing us (6%) | ||

| 2.4 God versus Science | 2.4a. Prayers and faith should prevail (2%) |

Pro-vaccine narrative

The lack of education

First of all, lack of education emphasizes the story that Romanians are generally a people with a lower level of education, compared to other EU countries. Also, a common sub-theme in this discourse is that of the increased proportion of functional illiterates. Or, as it is written in a comment:

54. The lack of education can be seen in the comments here, not only in the vaccination rate. We are still wondering what political class we have, given that all these functional illiterates vote. (Pro-vaccine comment, story 4, written on 8 October 2021)

Not coincidentally, this theme also highlights multiple ironies toward those who are against vaccination. These ironies have the role of highlighting the contrast between the anti-vaccination discourses, which have several claims of erudition, and the relatively low level of education of Romanians, materialized in the number of school years. According to Eurostat data, only 25% of Romanians have completed tertiary education, compared to 40% in Europe and with percentages of approx. 60% in countries such as Luxembourg, Ireland, and Lithuania (Eurostat, 2021). In this regard, an ironic comment from a pro-vaccination user is worth mentioning:

86. We do not get vaccinated because we Romanians know them all, we are smarter than all the countries that have been vaccinated 90%. (Story 4, written on 8 October 2021)

Other sub-themes discuss the inclusion of Romania and Bulgaria among the countries with the lowest performance in the multiple statistics made at European level, which, for some users, is reflected in the very low vaccine coverage in the two states. As mentioned in a suggestive comment:

23. Only Romanians and Bulgarians are smart, the foam of the world, who do not get vaccinated because they will no longer have children, which they still raise in poverty anyway, or they feel like they are dying from a needle with serum. They do not inform themselves, they do not read about what the vaccine contains but they assimilate any information from Şoşoacă [a Romanian senator with multiple public statements against vaccine] or the great experts with 6 classes in epidemiology.

Unvaccinated should avoid hospitals

Another popular theme among pro-vaccination comments is the situation in which those who do not want to get vaccinated should avoid coming to the hospital, regardless of the severity of their health, given that the medical system is already almost collapsing, while almost all the patients with Covid-19 are overwhelmingly unvaccinated.

1.I am vaccinated and I got the disease, fortunately I did not get to ICU. I think the vaccine still protected me from a more serious form. But I am amazed at the opinion of some others, and I am upset with those who refuse the vaccine but then call the emergency room and fill the wards of the hospitals. Honestly, I think those who refuse the vaccine should be co-paid for these services! I assume the reactions of the unvaccinated who will jump in my head. Anyway, I wish you all good health. (Story 1, written on 10 October 2021)

Other users point out the ironic situation in which some of those who do not trust doctors express the intention to be treated in hospital when their health is critical. In this regard, it is worth mentioning a suggestive comment:

80. Those of you who are not vaccinated and go to the hospital with Covid should send your doctors home to treat you alone, as they are considered criminals anyway. (Story 4, written on 8 October 2021)

Another popular sub-theme in this discursive category is that unvaccinated people who arrive at the hospital because of Covid-19 should pay the full cost of treatment, given that they avoided getting vaccinated, which was free (comment 64, story 3). On the other hand, other pro-vaccination comments urge anti-vaccine people to either be treated at home with “natural products” (comment 14, story 1), either to be treated in private hospitals where they can pay for treatments, at higher prices (comment 65, story 3).

Science versus god

This theme includes comments that mention a high level of trust in doctors and science, and that criticize actors who have anti-vaccination messages. Thus, an open source suggestive for this topic concerns the criticisms addressed to the church representatives who, in the opinion of some pro-vaccination commentators, tried as much as possible to prevent the citizens from getting vaccinated. As it is written in a comment:

4. We are a people easy to manipulate! Priests urge us not to get vaccinated! I believe in science and I was vaccinated with the 3rd dose! Look, nothing happened to me! (Story 1, written on 10 October 2021)

Another example of suggestive commentary on this topic is aimed at individuals for whom Facebook is a true source of information in the context of the pandemic. Thus, a comment is ironizing certain conspiracy theories that have been circulating for a while in the online space, as follows:

I also read on Facebook that after vaccination you die in about 3 years. I decided to die vaccinated. (Story 1, written on 10 October 2021)

Vaccination during Ceauşescu’s regime

Some pro-vaccination comments use as an argument the way in which the population was vaccinated during Nicolae Ceauşescu, the last communist leader of Romania, between 1965 and 1989. Some Romanians born before 1989 remember that any period of vaccination during the communist regime was done ad hoc, most of the time during school, without the need for any consent or statement on one’s own responsibility. Thus, the reminder made in a commentary that quite accurately describes the way in which vaccination was carried out during the communist regime is suggestive.

85. When I was little, we all knew you had nothing to say about vaccination. The doctor simply came to the classroom and took us all in turn, you didn’t even know how fast time passed and how fast you got vaccinated. I don’t think it took more than 15 minutes to vaccinate a class of 35 kids. Now you all wake up wanting informed consent. (Story 4, written on 7 October 2021)

Another nostalgic user rhetorically addresses those who insist that vaccination must be a personal choice. Thus, he discusses the necessity of compliance with vaccination, along with a background of nostalgia for an authoritarian leader, where vaccination was a natural process of avoiding mass disease, not a matter of democratic choice.

83. I’m really curious if it was in Ceausescu’s time [Last Romanian communist leader, during 1965-1989], did anyone have the courage to say that they don't get vaccinated? However, those who do not get vaccinated show cowardice and selfishness. (Story 4, written on 7 October 2021)

Anti-vaccine narrative

You are paid to say that

A popular theme in the anti-vaccine speeches is the accusation of those who are pro-vaccine, be they doctors or citizens, that they are paid to publicly support vaccination. Thus, an anti-vaccination commentary states that doctors receive very high incomes in order to promote an experimental serum.

31. First of all, you can’t trust someone who makes a fortune for the lies they tell. You don’t have to trust some doctors because they have that € 30,000 income. (Story 1, written on 10 October 2021)

Other comments target other professional categories that have publicly encouraged vaccination. In this regard, addressing a post from a citizen with a multiple comorbidity (Story 6), an anti-vaccination commentary shows accusations and threats against him, by the fact that he was bribed to promote the vaccine.

137. How much money did they give you for advertising, don’t you think that you are urging the world to death? One day you will pay for this! (Story 6, written on 26 September 2021)

The doctors are killing us

Another recurring theme among anti-vaccination speeches is the high number of Covid-19 deaths due to the fact that doctors kill patients in order to clear the beds as soon as possible for other patients. On the one hand, a commentator describes her mother’s death after being admitted to Colentina Hospital, and owes this death to the starvation and thirst she was subjected to.

25. Vaccine, non-vaccine, people in Colentina [a Romanian hospital] die because they don't even receive a glass of water, nor food. Doctors fail to say that. My mother was hospitalized there this winter and with great humiliation and unmanageable queues, being impossible to send water and food to her. My mother called me crying that everyone is starving around her ... we all pay 3 meals / day for prisoners but for those who have paid taxes for years / decades we have only humiliation and contempt! I don't even mention the permanent lack of basic, common medicines, nothing sophisticated ... that’s why the people of “Covid” die!!! (Story 1, written on 10 October 2021)

On the other hand, one comment considers the Story 3—which states that some patients take off their oxygen masks to shout to be vaccinated—to be false, saying that in fact patients take off those masks because they are suffocated with too much oxygen.

70. They take off their masks because you give them too much oxygen and hurt them, you destroy their lungs, you are ashamed, you don't want to be bothered by the patients' agitations, and you sedate them! (Story 3, written on 8 October 2021)

Expressing distrust in medical staff is a common problem observed in this thematic analysis, and many patients even launch concrete allegations of malpractice, as was the case in comment 25. In addition, another comment (71) states that it has completely lost confidence in doctors since they have not noticed a patient with a tumor, who was walking agonizingly in the hospital hallways, and who eventually died, completely ignored by the medical staff.

Experimental vaccine

This category includes several sub-themes. One of these is the one regarding new and unknown side effects, but also the fact that no one assumes the legal consequences in case of severe effects (comment 26, story 1, written on 10 October 2021). Another sub-theme concerns the medium and long-term effects of the vaccine, as asked in a comment:

33. Will this vaccine affect us in the long run? In 3, 5 or 10 years? What are the long-term effects? What guarantee do I have that I will not suffer anything in time? Who is responsible for the side effects? (Story 1, written on 10 October 2021)

Furthermore, another sub-theme considers vaccinated people as "guinea pigs", while minimizing the symptoms of Covid-19:

51. Let’s be guinea pigs for an experimental flu vaccine, a little different than the ones for which vaccines have not been able to eliminate them from our lives. Why are we vaccinated and not treated? I wonder why?! (Story 2, written on 10 October 2021)

One comment also likens the vaccine to a poison, precisely because of the potentially lethal effects the vaccine will generate in a few years.

105. You are pathetic and instigate the world to inject, with what??? Do you even know what that poison contains, what side effects do you expect over time??? (Story 4, written on 7 October 2021).

Finally, some anti-vaccination comments consider that the cure of those vaccinated takes longer than to those not vaccinated, which is why vaccination should remain strictly a personal decision (comment 134, story 6, written on 26 September 2021).

God versus science

This theme deserves to be highlighted in antithesis with 1.3. Science versus God, present in the pro-vaccination narrative. Although the leadership of the Romanian Orthodox Church has never officially declared itself against the vaccination campaign, it is known that the statements and attitudes of Romanian priests are mainly anti-vaccination, which is even reflected in many of the comments on social media. Also, the call to prayer, existing in several anti-vaccination comments, seems to be associated with an increased contempt for medical staff, already exhausted by the fourth wave of the pandemic.

74. Oh God, who else still believes you? A patient who is dying, better says a prayer rather than shouting for the vaccine!!!! (Story 3, written on 8 October 2021)

The antithesis between God and science appears in another comment included in the analysis, and this comparison comes with additional explanations from a user. Thus, faith comes with freedom and individual choice, which places the pandemic context around a socially constructed vaccine discourse: its benefits do not (anymore) have a strictly medically determined objectivity, but gain advantages and disadvantages established intersubjective.

108. I don't believe in science. I believe in God. And stop forcing vaccination! Who wants to get vaccinated, let them do it. And whoever does not want to, respect their choice because in the end everyone does what he wants with his life and body. (Story 4, written on 7 October 2021)

Discussion

The thematic analysis performed on the RO Vaccinare official page manages to confirm a series of recurring assumptions in the vaccination campaigns carried out over time. On the one hand, many obviously pro-vaccination comments are present in the narratives that bring into question all the negative, potentially lethal consequences that non-vaccination can bring, as we can see in Story 3, where we talk about patients who take off their oxygen masks and beg the doctors to vaccinate them when it's too late. This confirms previous results (Huang and Liu 2021) which show that the loss frame creates a stronger impact than the gain frame. In other words, individuals react more promptly to vaccine discourses that highlight mainly the losses that may be present in the absence of the vaccine. On the other hand, many of the anti-vaccination comments confirm various previously reported topics. In this sense, the vaccine as an “experimental serum” or as a biological weapon is a recurring theme in previous studies, both in international studies (Bean 2011; Kata 2010) and in studies conducted in Romania (Crăciun and Băban 2012).

The situation in Romania remains one of the worst in Europe and in the world in terms of the death rate caused by Covid-19, and this situation occurs due to reduced vaccine coverage. The gravity of the Romanian medical context is already evident worldwide, given the fact that the WHO announced, on October 17, 2021, that it will send to Romania a delegation of experts to verify the reasons for such a low vaccination (Neacşu 2021). In this context, one may ask how it is that different conspiracy theories are so attractive for Romanian Facebook users. One possible explanation is the inducing of a sense of injustice and anger, which leads individuals to reject information from official sources. The association of a medical act with politics in general confirms what Polletta (2011: 119) said about some narratives: “And why are groups unable to discredit that narrative if it is untrue? A plausible answer is that the dominant story meshes with deeply held ideological values” (own emphasis). Another function of narratives, also described in this study, is that of outlining a nostalgia framework. According to Maly et al. (2012), “nostalgia narratives” refer to selective versions of the past, through which the events that favor the message that the sender intends to convey are evoked. A similar situation is encountered in the case of comments that evoke childhood memories, when Romania was led by Nicolae Ceaușescu, the last communist leader of the country (1965–1989). Pro-vaccination comments in this category ironically look at how freedom is understood today, describing in appreciative terms that vaccination was an obligation during the communist regime. Although Romanians experienced a severe lack of food and their rationalization during Nicolae Ceaușescu’s time, this does not prevent certain users from evoking this notable advantage, that of maintaining public health through compulsory vaccination.

Romanian health and communication experts also applied, through the official page RO Vaccinare, certain persuasion strategies in order to improve the vaccination campaign. Thus, by evoking personal narratives of Romanian citizens of different ages and comorbidities, the intention is to generate empathy among readers (Chou and Budenz, 2020). However, the situation of Romania in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic remains a sensitive one, given the fact that the lack of any legal filtering in the digital environment determines the easy propagation of conspiracy theories on social networks. Thus, the lack of digital literacy among Romanians causes additional difficulties in identifying possible fake news related to vaccination, and various politicians with concrete political agendas manage, through charisma and anti-system statements, to generate enough collective emotions among the population.

As can be seen, narratives around vaccination provide a socially constructed interpretation, which is why a medical act that should be viewed and evaluated uniformly among the population is, in fact, subject to disputes that reflect different values, attitudes, and interests. Thus, vaccination narratives become “vehicles of ideology” (Polletta 2011: 112): on the one hand, some see them as a very effective medical method for combating the pandemic and, on the other hand, others consider them a form of betrayal of God, faith, or free choice. Although this illusory opposition between medicine and religion may sound ridiculous to some readers, it is important to know that narratives (scientific facts included) do not gain public interest because they are true, but rather because they are made to seem true (Latour and Woolgar 1986).

Further studies could study the impact that conspiracy theories have on the formation of opinions in the digital environment, given that their influence seems to give visible results in terms of the effectiveness of the vaccination campaign in Romania. Previous studies show that a visible role belongs to bots that repeatedly send messages to a specific audience. Thus, the role of these boots is that of: “… promoting conflict, sharing polarizing and Anti-Vaccine sentiment, and creating the illusion of an even-sided debate” (Scannell et al. 2021: 444). If it is found that the role of such bots is a decisive one in shaping the opinions and values on new media technologies, this could decisively influence the way in which future public information campaigns will take place.

Limitations and implications

Of course, this study also has some limitations. One of the limits can be found in its inductive exploratory character, by the fact that only six narratives and subsequent 137 comments were included in the analysis. It should also be noted that this study is limited to Romanian Facebook users, so it cannot be extended to the level of the entire population. However, even in the presence of an exploratory approach, the thematic analysis manages to reveal certain ideological substrates existing among the users’ comments. Thus, this study offers different implications for future quantitative research, in order to observe to what extent different behaviors regarding vaccination contribute, in fact, to the shaping of certain human typologies. Such research also demonstrates its usefulness in policymaking, as it illustrates some of the recurring themes gained online from the vaccination campaign. As can be seen, several themes appear also in some previous vaccination campaigns, which is why communication experts should consider how to mitigate this sort of digital discourses.

Conclusion

A valuable sociology of storytelling shows that any discursive structure around us respects certain principles of narratives: allusiveness, value and ideological partisanship, their ability to be memorized in the medium or long term, plausibility (not veracity), but also their ability to generate empathy when needed. As we have seen, even the discourses around vaccination respect these principles of narratives, which makes the polarization around this phenomenon more and more accentuated. Thus, the thematic analysis carried out in this article shows that even the medical phenomenon of vaccination is, in essence, a socially constructed one, so that the effectiveness of vaccination depends, in fact, on the efficiency that individuals assign to it. The partisan treatment of vaccination narratives, fueled by various narratives meant to increase skepticism about vaccination, led Romania to the critical situation of reporting over 400 daily Covid-19 deaths in mid-October 2021, which is why possible interventions by scientists, health experts and communication experts must be performed simultaneously.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was necessary for this study.

Data availability

All the stories and comments included in the analysis were added in the supplemental file.

Code availability

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Granted by the Ethics Commission of the University of Bucharest & Faculty of Sociology and Social Work (available in original, at the next page).

Consent to participate

As it was an anonymous selection of comments on the Facebook group, the consent was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Research involved in humans and/or animals rights

Not applicable.

References

- Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M, Crockett MJ, Crum AJ, Douglas KM, Druckman JN, Drury J, Dube O, Ellemers N, Finkel EJ, Fowler JH, Gelfand M, Han S, Haslam SA, Jetten J, Willer R. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(5):460–471. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean SJ. Emerging and continuing trends in vaccine opposition website content☆. Vaccine. 2011;29(10):1874–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P. & Luckmann, T. (1967) The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Anchor

- Boghardt T. Soviet block intelligence and Its AIDS disinformation campaign. Studies in Intelligence. 2009;53(4):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso M, Caso D, Conner M. Anticipating pride or regret? Effects of anticipated affect focused persuasive messages on intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Soc Sci Med. 2021;289:114416. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserotti M, Girardi P, Rubaltelli E, Tasso A, Lotto L, Gavaruzzi T. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc Sci Med. 2021;272:113688. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou WYS, Budenz A. Considering Emotion in COVID-19 vaccine communication: addressing vaccine hesitancy and fostering vaccine confidence. Health Commun. 2020;35(14):1718–1722. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1838096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciun C, Baban A. “Who will take the blame?”: Understanding the reasons why Romanian mothers decline HPV vaccination for their daughters. Vaccine. 2012;30(48):6789–6793. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan V, Dixon GN. Fighting the infodemic on two fronts: reducing false beliefs without increasing polarization. Sci Commun. 2021;43(5):674–682. doi: 10.1177/10755470211020411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, D. (2016) Fake News Expert On How False Stories Spread And Why People Believe Them. NPR. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from https://choice.npr.org/index.html?origin=https://www.npr.org/2016/12/14/505547295/fake-news-expert-on-how-false-stories-spread-and-why-people-believe-them

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. (2021) Educational attainment statistics - Statistics Explained. Ec.Europa.Eu. Retrieved October 16, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Educational_attainment_statistics&fbclid=IwAR3P84hxxMPal8zS3e5MGFU5phfRAzq54V5UblUxJS1ISLvZztP4FOokZhw

- Funk, C., Kennedy, B., & Johnson, C. (2020) Trust in Medical Scientists Has Grown in U.S., but Mainly Among Democrats. Pew Research Center Science & Society. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/05/21/trust-in-medical-scientists-has-grown-in-u-s-but-mainly-among-democrats/

- Gunaratne K, Coomes EA, Haghbayan H. Temporal trends in anti-vaccine discourse on Twitter. Vaccine. 2019;37(35):4867–4871. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Liu W. Promoting COVID-19 vaccination: the interplay of message framing, psychological uncertainty, and public agency as a message source. Sci Commun. 2021 doi: 10.1177/10755470211048192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPSOS. (2021, February 18). Controverse şi convingeri despre vaccinarea anti-COVID-19 în România. Retrieved October 9, 2021, from https://www.ipsos.com/ro-ro/controverse-si-convingeri-despre-vaccinarea-anti-covid-19-romania

- Kata A. A postmodern Pandora’s box: Anti-vaccination misinformation on the Internet. Vaccine. 2010;28(7):1709–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Levine Z, Schulz WS, Paterson P. Measuring trust in vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1599–1609. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour B, Woolgar S. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lwin MO, Lu J, Sheldenkar A, Schulz PJ, Shin W, Gupta R, Yang Y. Global sentiments surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic on twitter: analysis of twitter trends. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e19447. doi: 10.2196/19447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines DR. Narrative’s moment and sociology’s phenomena: toward a narrative sociology. Sociol Q. 1993;34(1):17–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1993.tb00128.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maly M, Dalmage H, Michaels N. The end of an idyllic world: nostalgia narratives, race, and the construction of white powerlessness. Crit Sociol. 2012;39(5):757–779. doi: 10.1177/0896920512448941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, S. (2021) Two Europes: Low vaccine rates in east overwhelm ICUs. AP NEWS. Retrieved October 16, 2021, from https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-health-pandemics-bulgaria-bucharest-a7541bb8eb92fdc7756983cbf2371a6c

- Neacșu, B. (2021) OMS trimite o delegație în România, ca „să înțeleagă de ce avem o vaccinare așa de redusă” [WHO sends delegation to Romania to "understand why we have such low vaccination"]. Libertatea. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.libertatea.ro/stiri/presedintele-colegiului-medicilor-o-delegatie-a-oms-vine-in-romania-sa-inteleaga-de-ce-avem-o-vaccinare-asa-de-redusa-3788372

- Neundorf K. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Obreja D. Which one to trust? Exploratory analysis on astrology, science and religiosity among students in Bucharest. Sociologie Romaneasca. 2021;19(1):117–133. doi: 10.33788/sr.19.1.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polletta F. Characters in political storytelling. Storytelling, Self, Society. 2015;11(1):34–55. doi: 10.13110/storselfsoci.11.1.0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polletta F, Callahan J. Deep stories, nostalgia narratives, and fake news: Storytelling in the Trump era. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham: In Politics of meaning/meaning of politics; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Polletta F, Chen PCB, Gardner BG, Motes A. The sociology of storytelling. Ann Rev Sociol. 2011;37(1):109–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pricop, S. (2021, June 8). Un stareț din Neamț le-a spus enoriașilor că le vor crește solzi și vor deveni zombi, dacă se Libertatea. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://www.libertatea.ro/stiri/predica-unui-staret-din-neamt-despre-vaccinare-oamenii-se-vor-umple-de-solzi-ca-la-pesti-pozitia-bor-3590647

- Robinson JA. Personal narratives reconsidered. J Am Folklore. 1981;94(371):58–85. doi: 10.2307/540776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, I. (2021, September 30). Diana Șoșoacă, umilită crunt de un epidemiolog după ce a declarat că vaccinul provoacă „sterililtate pe trei generații”. Ce a putut să-i transmită senatoarei antivacciniste. Playtech. Retrieved October 9, 2021, from https://playtech.ro/stiri/diana-sosoaca-umilita-crunt-de-un-epidemiolog-dupa-ce-a-declarat-ca-vaccinul-provoaca-sterililtate-pe-trei-generatii-ce-a-putut-sa-i-transmita-senatoarei-antivacciniste-401208

- Scannell D, Desens L, Guadagno M, Tra Y, Acker E, Sheridan K, Rosner M, Mathieu J, Fulk M. COVID-19 vaccine discourse on twitter: a content analysis of persuasion techniques, sentiment and mis/disinformation. J Health Commun. 2021;26(7):443–459. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2021.1955050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlăsceanu, L., Rughiniș, C., & Dușa, A. (2010). Publicul și Știința. Știință și societate. Interese și percepții ale publicului privind cercetarea științifică și rezultatele cercetării. București: STISOC. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329885093_Publicul_si_stiinta_Stiinta_si_societate_Interese_si_perceptii_ale_publicului_privind_cercetarea_stiintifica_si_rezultatele_cercetarii.

- Ulceluse, M. (2020) How the Romanian diaspora helped put a new far-right party on the political map. LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) blog (2020). Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/108302/1/europpblog_2020_12_17_how_the_romanian_diaspora_helped_put_a_new_far.pdf

- Unkelbach C, Alves H, Koch A. Negativity bias, positivity bias, and valence asymmetries: explaining the differential processing of positive and negative information. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/bs.aesp.2020.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vulpe SN, Rughiniş C. Social amplification of risk and “probable vaccine damage”: a typology of vaccination beliefs in 28 European countries. Vaccine. 2021;39(10):1508–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the stories and comments included in the analysis were added in the supplemental file.

None.