Abstract

Palliative care nurses experience huge pressures, which only increased with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). A reflection on the new demands for nursing care should include an evaluation of which evidence-based practices should be implemented in clinical settings. This paper discusses the impacts and challenges of incorporating coaching strategies into palliative care nursing. Evidence suggests that coaching strategies can foster emotional self-management and self-adjustment to daily life among nurses. The current challenge is incorporating this expanded knowledge into nurses’ coping strategies. Coaching strategies can contribute to nurses’ well-being, empower them, and consequently bring clinical benefits to patients, through humanized care focused on the particularities of end-of-life patients and their families.

Keywords: coaching, mental health, palliative care, nurse leaders, evidence-based practice

Introduction

Palliative care (PC) aims to enhance the quality of life of patients facing life-threatening diseases, as well as improve the well-being of their carers and significant others, through active holistic care (Radbruch et al., 2020). This imposes serious challenges for nurses, such as end-of-life (EOL) decisions and contact with suffering and dying people (Parola et al., 2018). Working in a stressful environment can lead to high levels of emotional exhaustion, job insecurity, and decreased quality of care when not effectively managed (Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2020; McKinless, 2020). Alarming statistics about health care provider burnout indicate a growing need for an emphasis on self-care and recognizing that professionals must attend to their own well-being (Leo et al., 2021; Tawfik et al., 2019).

Workplace well-being is a key issue in the field of health care (Ali et al., 2021). Thus, nursing managers should mobilize strategies that promote well-being and help their nurses develop resilience and facilitating skills to prevent burnout, turnover, job dissatisfaction, and mental illness (Shah et al., 2021; Trepanier et al., 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic has brought increased constraints, caused by a personal life unbalanced by professional demands (Chidiebere Okechukwu et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2021).

Coaching is evolving as a professional skill and has been recommended for nurses exposed to high stressors, particularly in order to empower and guide nurse leaders in supporting their respective nurses (Piamjariyakul et al., 2019; Trepanier et al., 2022). Coaching can influence the health care environment within the field of PC, implying that professionals must understand themselves and behave as part of a multidisciplinary team (Suikkala et al., 2021).

This paper discusses the role of coaching in PC nursing, presents the guiding principles of coaching, and analyzes some applications in palliative nursing practice, education, and leadership. Finally, trends in coaching for EOL and PC are systematized.

Brief Review

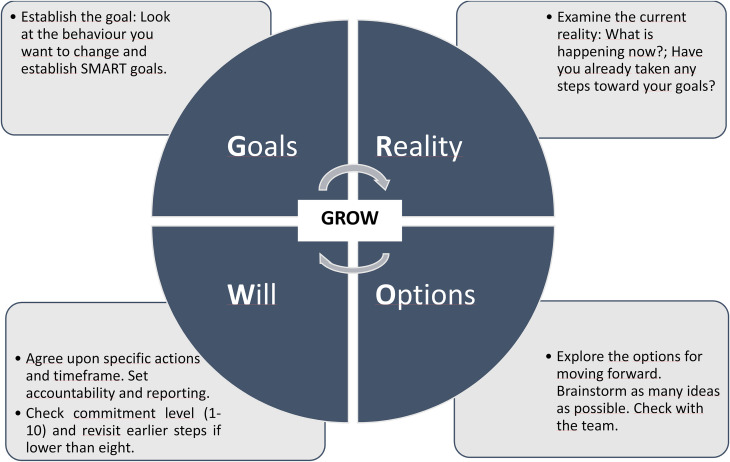

The concept of coaching is often confused with mentoring, but they are two different concepts. Coaching is defined as an interactive and interpersonal process that offers personal and professional support through the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and fundamental actions for professional practice (Sarroeira et al., 2020). The coaching process promotes self-knowledge and the establishment of goals through a deep analysis of the individual, provoking a reflection on perspectives, mindsets, beliefs, and approaches that can lead to more sustainable behavior (Cable & Graham, 2018; Whitmore, 2017). Typically, coaching involves one-to-one learning during a short period. Widely used to structure a coaching conversation, the Goal, Reality, Options, Will (GROW) model (Figure 1) is a succinct framework for coaching grounded on learning through experience: reflection, insight, making choices and pursuing goals. According to Rodenbach et al. (2020), coaching PC conversations could increase health care providers’ preparedness in discussing PC topics and completing goals of care. In contrast, mentoring implies a long period during which the mentor shares their experience and knowledge to help the individual in their development process (Kowalski, 2019; Seehusen et al., 2021). Mentoring is typically less structured than coaching, the latter following a more non-directive and rigorous structure. In mentoring, while having a mentoring agenda of meetings and goals is recommended, the mentee is responsible for this organization.

Figure 1.

Grow model according to Whitmore (2017).

Applications of Coaching in Palliative Nursing Practice, Education, and Leadership

The concept of coaching in nursing was introduced by Benner (1984). She used the Dreyfus Model to explain how nurses progressively develop skills, which included coaching as a strategy (Potter, 2019). More recently, the Theory of Integrative Nursing Coaching was developed to guide coaching practice in nursing, education, research, and health policy (Moore et al., 2022). This middle-range theory focuses essentially on the relationship with the person and emphasizes self-care practices, well-being, intentionality, presence, attention, and therapeutic use of oneself as fundamental means to facilitate recovery. Nurse coaches, by facilitating personal transformation through listening with Healing, Energy, Awareness, Resiliency, Transformation (HEART), progress toward the aim of nourishing people in a sustainable world—from the microcosm to the macrocosm (Moore et al., 2022).

Coaching can be applied to nurses (Dyess et al., 2017; Yusuf et al., 2018), nurse leaders (Waldrop & Derouin, 2019), nurse students (Hurley et al., 2020; Kaldawi, 2022; Sezer & Şahin, 2021) and nursing care support with patients and their families (Flanagan et al., 2022; Johansson et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2022), the latter being the most frequent application. Coaching assists nurses in engaging in dialogs and interactions aimed at improving professional growth, career commitment, and practice (Barr & Tsai, 2021). Thus, Donner and Wheeler (2009) propose a classification of coaching in four domains, namely:

Peer coaching. Can be applied to assist nurses in furthering their careers and increasing job satisfaction. This area is one of the least applied. Peer coaching has been successfully used in inpatient settings to teach primary PC skills (Jacobsen et al., 2017).

Health coaching. A valuable method for nurses who want to assist patients in reaching their aspirations. This focus area is very important to PC nurses who are challenged daily to help patients and families accomplish their last wishes. Coaching conversations should include several communication skills (such as therapeutic presence, deep listening, use of silence and motivational interviewing) in order to help patients identify their individual barriers and facilitators and realize their goals (Rosa et al., 2021a). Coaching can help nurses adopt a person-centered practice but can also be used to prevent ill health and reduce the impact of chronic conditions (Barr & Tsai, 2021; Benzo et al., 2017; Fazio et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2022).

Interprofessional coaching. The emphasis is on advancing interprofessional education and practice, promoting teamwork, and ensuring the team provides comprehensive care. This area fosters the development of professional skills such as multi-professional communication (Ahmann et al., 2021; Douglas & MacPherson, 2021; McKinless, 2020; Niglio de Figueiredo et al., 2015) and is a promising area in PC.

Succession planning. Coaching can be used to help plan successions, facing the changing definitions of work-life balance, the demographic reality and the impending retirement of significant numbers of leaders. Planning for leadership succession is becoming a key component of long-term human resources strategies in many organizations. Since leadership plays an essential role, affecting patients and professional outcomes and even the work environment (Specchia et al., 2021), nurse leaders must develop facilitators skills, especially for less experienced nurses and those beginning their careers (Major, 2019). Leaders have a particularly influential role in the implementation of evidence-based practices by providing a supportive culture and environment (Bianchi et al., 2018).

Other models, such as positive psychological coaching (PPC), have emerged as a new paradigm for practitioners interested in professional development (Richter et al., 2021). Also known as strengths-based coaching, PPC “can be defined as a short to medium-term professional, collaborative relationship between a client and coach, aimed at the identification, utilization, optimization, and development of personal strengths and resources in order to enhance positive states, traits and behaviours” (van Zyl et al., 2020, p. 1). A recent study produced a 5-phase PPC model aimed at promoting professional development (Richter et al., 2021).

Both coaching in nursing and the positive psychology model recommend best practices that organizations should incorporate to develop professional staff resiliency, leadership effectiveness, and enhanced team performance (Dyess et al., 2017; Grant & Atad, 2021; Spiva et al., 2021). In this sense, some components, tools, and evaluation strategies of coaching training programs (Table 1) should be used to improve collaborative teamwork (Johansson et al., 2020; Penconek et al., 2021; Yusuf et al., 2018), strengthen team relationships, and promote engagement with the institution (Dyess et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2020). The current challenge is incorporating this expanded knowledge into nurses’ coping strategies. The nursing profession must make strategic plans that develop skills in nursing education, clinical practice, health policy, and even research. Nurses in PC are well-positioned to develop and implement coaching tools as a means to improve their mental health and professional soft skills needed for success on the job (such as empathy, self-motivation, resilience, emotional literacy, critical thinking and work ethic) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of Key Components and Coaching Strategies of Different Training Programs.

| Coaching training program for nursing (Donner & Wheeler, 2009) | Positive psychological coaching (Richter et al., 2021; van Zyl et al., 2020) | |

|---|---|---|

| Content/coaching phases |

|

|

| Learning strategies (techniques and tools) |

|

|

| Evaluation strategies |

|

• Hope assessment tools • Strengths-focused psychometric assessments • Assessment of the learning transfer |

Table 2.

Skills Improved by Coaching Tools.

|

Current Insights and Trends in Coaching for EOL and PC

Clinical environments affect the safety and mental health of nurses as well as the quality of their health care service. The quality of this environment should not be neglected by health decision-makers. Coaching as a process of nurse development and empowerment is a powerful ally (Dossey & Luck, 2015). Used frequently in health care delivery, only rarely is it used to promote the well-being of health professionals. Health care organizations are still very focused on the needs of patients and improving care outcomes while neglecting the needs of health professionals. This may lead to medium and long-term complications in nurses’ health and well-being, and consequently, the care they provide (Rosa et al., 2021a).

The significant advantages of coaching for nurses, especially those subject to high work stressors (i.e., PC nurses), can be obtained using simple and accessible tools during different phases of nurse education. This demands partnership and collaboration between nursing schools and health institutions to improve professional performance, as well as nurse well-being and mental health.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual and mobile phone-based coaching interventions have become more common (Rosa et al., 2021b; Tsiouris et al., 2020; Wittenberg et al., 2018). The added value of such approaches in terms of effectiveness, technology acceptance, and reduced costs has been well documented (Tsiouris et al., 2020). Virtual coaching “enhances personal well-being, improves global health partnerships and knowledge exchange, and fosters communication across all levels of education and clinical practice” (Rosa et al., 2021b, p. 1).

Conclusion

The coaching model offers a systematic, relational strategy that includes tools to enhance nurse competencies, both individual and team skills such as self-analysis, therapeutic presence, compassion, and moral insight for the attainment of specified PC goals. The emphasis is on individual needs, strengths, and shortcomings, employing dialog and reflection in a setting of confidentiality and trust. This method is very beneficial for one-on-one “skill-based” teaching and learning. It also helps the PC team handle communication and psychological concerns while offering emotional support to professionals. Leaders play an, especially, essential role, as they are the most familiar with their employees and can thus best adjust and adopt those tools.

Footnotes

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the finding has been attached to the editorial office.

Authors’ Contributions: All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and have approved it for publication.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (UIDB/05704/2020 and UIDP/05704/2020) and under the Scientific Employment Stimulus—Institutional Call—(CEECINST/00051/2018).

ORCID iDs: Cristina Costeira https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4648-355X

Ana Querido https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5021-773X

Carlos Laranjeira https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1080-9535

References

- Ahmann E., Saviet M., Fouché R., Missenda M., Rosier T. (2021). ADHD Coaching and interprofessional communication: A focus group study. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 19(2), 70–87. 10.24384/fvjs-dp63 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M., Islam T., Ali F. H., Raza B., Kabir G. (2021). Enhancing nurses well-being through managerial coaching: A mediating model. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare, 14(2), 143–157. 10.1108/IJHRH-10-2020-0088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barr J. A., Tsai L. P. (2021). Health coaching provided by registered nurses described: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 74. 10.1186/s12912-021-00594-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P. (1984). From novice to expert excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Benzo R. P., Kirsch J. L., Hathaway J. C., McEvoy C. E., Vickers K. S. (2017). Health coaching in severe COPD after a hospitalization: A qualitative analysis of a large randomized study. Respiratory Care, 62(11), 1403–1411. 10.4187/respcare.05574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M., Bagnasco A., Bressan V., Barisone M., Timmins F., Rossi S., Pellegrini R., Aleo G., Sasso L. (2018). A review of the role of nurse leadership in promoting and sustaining evidence-based practice. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(8), 918–932. 10.1111/jonm.12638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable S., Graham E. (2018). “Leading better care”: An evaluation of an accelerated coaching intervention for clinical nursing leadership development. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(5), 605–612. 10.1111/jonm.12590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidiebere Okechukwu E., Tibaldi L., La Torre G. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of nurses. La Clinica Terapeutica, 171(5), e399–3400. 10.7417/CT.2020.2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner G. J., Wheeler M. M. (2009). Coaching in nursing: an introduction. International Council of Nurses, Sigma Theta Tau International. http://www.donnerwheeler.com/documents/STTICoaching.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dossey B. M., Luck S. (2015). Nurse coaching through a nursing lens: The theory of integrative nurse coaching. Beginnings (American Holistic Nurses' Association), 35(4), 10–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas N. F., MacPherson M. K. (2021). Positive changes in certified nursing assistants’ communication behaviors with people with dementia: Feasibility of a coaching strategy. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(1), 239–252. 10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyess S. M., Sherman R., Opalinski A., Eggenberger T. (2017). Structured coaching programs to develop staff. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 48(8), 373–378. 10.3928/00220124-20170712-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio S., Edwards J., Miyamoto S., Henderson S., Dharmar M., Young H. M. (2019). More than A1C: Types of success among adults with type-2 diabetes participating in a technology-enabled nurse coaching intervention. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(1), 106–112. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan J., Post K., Hill R., DiPalazzo J. J. (2022). Feasibility of a nurse coached walking intervention for informal dementia caregivers. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 44(5), 466–476. 10.1177/01939459211001395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Urquiza J. L., Albendín-García L., Velando-Soriano A., Ortega-Campos E., Ramírez-Baena L., Membrive-Jiménez M. J., Suleiman-Martos N. (2020). Burnout in palliative care nurses, prevalence and risk factors: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7672. 10.3390/ijerph17207672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant A. M., Atad O. I. (2021). Coaching psychology interventions vs. positive psychology interventions: The measurable benefits of a coaching relationship. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(4), 532–544. 10.1080/17439760.2021.1871944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J., Hutchinson M., Kozlowski D., Gadd M., Vorst S. (2020). Emotional intelligence as a mechanism to build resilience and non-technical skills in undergraduate nurses undertaking clinical placement. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(1), 47–55. 10.1111/inm.12607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen J., Alexander Cole C., Daubman B. R., Banerji D., Greer J. A., O’Brien K., Doyle K., Jackson V. A. (2017). A novel use of peer coaching to teach primary palliative care skills: Coaching consultation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(4), 578–582. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson I., Torgé C. J., Lindmark U. (2020). Is an oral health coaching programme a way to sustain oral health for elderly people in nursing homes? A feasibility study. International Journal of Dental Hygiene, 18(1), 107–115. 10.1111/idh.12421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J., Simms-Ellis R., Janes G., Mills T., Budworth L., Atkinson L., Harrison R. (2020). Can we prepare healthcare professionals and students for involvement in stressful healthcare events? A mixed-methods evaluation of a resilience training intervention. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1094. 10.1186/s12913-020-05948-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldawi K. H. (2022). The impact of a clinical coaching education on faculty’s coaching behavior. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 17(1), 22–26. 10.1016/j.teln.2021.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski K. (2019). Differentiating mentoring from coaching and precepting. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 50(11), 493–494. 10.3928/00220124-20191015-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo C. G., Sabina S., Tumolo M. R., Bodini A., Ponzini G., Sabato E., Mincarone P. (2021). Burnout among healthcare workers in the COVID 19 era: A review of the existing literature. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 750529. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.750529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major D. (2019). Developing effective nurse leadership skills. Nursing Standard, 34(6), 61–66. 10.7748/ns.2019.e11247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinless E. (2020). Impact of stress on nurses working in the district nursing service. British Journal of Community Nursing, 25(11), 555–561. 10.12968/bjcn.2020.25.11.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maini, A., Fyfe, M., & Kumar, S. (2020). Medical students as health coaches: Adding value for patients and students. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 182. 10.1186/s12909-020-02096-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. K., Avino K., McElligott D. (2022). Analysis of the theory of integrative nurse coaching. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 40(2), 169–180. 10.1177/08980101211006599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niglio de Figueiredo M., Rudolph B., Bylund C. L., Goelz T., Heußner P., Sattel H., Fritzsche K., Wuensch A. (2015). ComOn coaching: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of a varied number of coaching sessions on transfer into clinical practice following communication skills training. BMC Cancer, 15(1), 503. 10.1186/s12885-015-1454-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola V., Coelho A., Sandgren A., Fernandes O., Apóstolo J. (2018). Caring in palliative care. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 20(2), 180–186. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penconek T., Tate K., Bernardes A., Lee S., Micaroni S., Balsanelli A. P., de Moura A. A., Cummings G. G. (2021). Determinants of nurse manager job satisfaction: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 118, 103906. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piamjariyakul U., Petitte T., Smothers A., Wen S., Morrissey E., Young S., Sokos G., Moss A. H., Smith C. E. (2019). Study protocol of coaching end-of-life palliative care for advanced heart failure patients and their family caregivers in rural appalachia: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Palliative Care, 18(1), 119. 10.1186/s12904-019-0500-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter C. U. (2019). Effect of INTERACT on promoting nursing staff’s self-efficacy leading to a reduction of rehospitalizations from short-stay care. Open Journal of Nursing, 9(08), 835–854. 10.4236/ojn.2019.98063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radbruch L., De Lima L., Knaul F., Wenk R., Ali Z., Bhatnaghar S., Blanchard C., Bruera E., Buitrago R., Burla C., Callaway M., Munyoro E., Centeno C., Cleary J., Connor S., Davaasuren O., Downing J., Foley K., Goh C, Pastrana T. (2020). Redefining palliative care: A new consensus-based definition. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(4), 754–764. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter S., van Zyl L. E., Roll L. C., Stander M. W. (2021). Positive psychological coaching tools and techniques: A systematic review and classification. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 667200. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.667200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenbach R., Kavalieratos D., Tamber A., Tapper C., Resick J., Arnold R., Childers J. (2020). Coaching palliative care conversations: Evaluating the impact on resident preparedness and goals-of-care conversations. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(2), 220–225. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa W. E., Karanja V., Kpoeh J., McMahon C., Booth J. (2021b). A virtual coaching workshop for a nurse-led community-based palliative care team in Liberia, West Africa, to promote staff well-being during COVID-19. Nursing Education Perspectives, 42(6), E194–E196. 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa W. E., Levoy K., Battista V., Dahlin C., Thaxton C., Greer K. (2021a). Using the nurse coaching process to support bereaved staff during the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing: JHPN : The Official Journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, 23(5), 403–405. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarroeira C., Cunha F., Simões J. (2020). Coaching & nursing: A qualitative analysis of literature. Journal of UIIPS- Research Unit of the Polytechnic Institute of Santarém, 8, 42–56. 10.25746/ruiips.v8.i1.19877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seehusen D. A., Rogers T. S., Al Achkar M., Chang T. (2021). Coaching, mentoring, and sponsoring as career development tools. Family Medicine, 53(3), 175–180. 10.22454/FamMed.2021.341047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sezer H., Şahin H. (2021). Faculty development program for coaching in nursing education: A curriculum development process study. Nurse Education in Practice, 55, 103165. 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah M., Roggenkamp M., Ferrer L., Burger V., Brassil K. (2021). Mental health and COVID-19: The psychological implications of a pandemic for nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 25(1), 69–75. 10.1188/21.CJON.69-75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H. K., Kennedy G. A., Stupans I. (2022). Competencies and training of health professionals engaged in health coaching: A systematic review. Chronic Illness, 18(1), 58–85. 10.1177/1742395319899466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specchia M. L., Cozzolino M. R., Carini E., Di Pilla A., Galletti C., Ricciardi W., Damiani G. (2021). Leadership styles and nurses’ job satisfaction: Results of a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1552. 10.3390/ijerph18041552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiva L., Hedenstrom L., Ballard N., Buitrago P., Davis S., Hogue V., Box M., Taasoobshirazi G., Case-Wirth J. (2021). Nurse leader training and strength-based coaching: Impact on leadership style and resiliency. Nursing Management, 52(10), 42–50. 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000792024.36056.c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suikkala A., Tohmola A., Rahko E. K., Hökkä M. (2021). Future palliative competence needs - A qualitative study of physicians’ and registered nurses’ views. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 585. 10.1186/s12909-021-02949-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik D. S., Scheid A., Profit J., Shanafelt T., Trockel M., Adair K. C., Sexton J. B., Ioannidis J. (2019). Evidence relating health care provider burnout and quality of care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 171(8), 555–567. 10.7326/M19-1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepanier S., Henderson R., Waghray A. (2022). A health care system’s approach to support nursing leaders in mitigating burnout amid a COVID-19 world pandemic. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 46(1), 52–59. 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiouris K., Tsakanikas V., Gatsios D., Fotiadis D. (2020). A review of virtual coaching systems in healthcare: Closing the loop with real-time feedback. Frontiers in Digital Health, 2, 567502. 10.3389/fdgth.2020.567502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zyl L. E., Roll L. C., Stander M. W., Richter S. (2020). Positive psychological coaching definitions and models: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 793. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop J., Derouin A. (2019). The coaching experience of advanced practice nurses in a national leadership program. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 50(4), 170–175. 10.3928/00220124-20190319-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore J. (2017). Coaching for performance. Principles and practice of coaching and leadership (5th ed.). Nicholas Brealey Publishing, pp. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg E., Ferrell B., Koczywas M., Del Ferraro C., Ruel N. H. (2018). Pilot study of a communication coaching telephone intervention for lung cancer caregivers. Cancer Nursing, 41(6), 506–512. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf F. R., Kumar A., Goodson-Celerin W., Lund T., Davis J., Kutash M., Paidas C. N. (2018). Impact of coaching on the nurse-physician dynamic. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 29(3), 259–267. 10.4037/aacnacc20186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]