Abstract

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a syndrome causing a sudden and unstoppable need to urinate with significant global prevalence. Several drugs are used to treat OAB; however, they have various side effects. Therefore, new treatment options for OAB are required. A series of novel 5-oxo-N-phenyl-1-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazoline-3-carboxamide derivatives were synthesized and evaluated for their large-conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channel activation through a cell-based fluorescence assay and electrophysiological recordings. Several compounds, including a 7-bromo substituent on the heterocyclic system, showed increased channel currents. Among the derivatives, compound 12h exhibited potent in vitro activity with a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 2.89 μM, good oral pharmacokinetic properties (area under the curve and half-life), and in vivo efficacy in a spontaneously hypertensive rat model.

Keywords: BKCa channel, activator, ion channel, overactive bladder, urinary bladder smooth muscle

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a neurological and muscular aging disease with significant prevalence worldwide.1,2 Patients with OAB syndrome experience regular urgency to urinate at all hours of the day and night.3 Currently, available urinary incontinence medications on the market include antagonists of muscarinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors4,5 and β3-adrenergic receptor agonists.5,6 ACh is released from parasympathetic neurons and binds to muscarinic receptors on bladder smooth muscle cells to cause muscle contraction and subsequent urination.7,8 Muscarinic receptor antagonists are widely used to treat OAB because they reduce ACh-induced urinary bladder smooth muscle contractions.9,10 However, they cause a variety of side effects including dry eyes and mouth, blurred vision, tachycardia, cognitive impairment, and constipation.11 In addition, β3-adrenergic receptor agonists promote the inhibition of tonic contractions of the bladder smooth muscle.12,13 Nevertheless, they are also associated with side effects, including urinary tract infections and high blood pressure, because they target major neurotransmitters.14 Therefore, new therapeutic agents for bladder disorders warrant investigation and discovery.

The large-conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channel, also called the BKCa channel, is activated by either depolarization or an increase of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration.15,16 BKCa channels are found in a variety of tissues, including the brain,17 smooth muscle,18,19 cochlea,19 and bladder.20,21 In particular, this channel is highly distributed in urinary smooth bladder muscle.22 It plays an important role in the repolarization of cell membrane potential and muscle relaxation.23 Recently, researchers found that an overactive bladder and urinary incontinence developed in BKCa channel knockout mice.24 In addition, it has been reported that the expression level of BKCa channels is significantly decreased in patients with excessive contractions of bladder smooth muscles.25 As a result, BKCa channel activation can cause urinary bladder smooth muscle relaxation, suggesting that BKCa channels could be a therapeutic target for the treatment of OAB.

BKCa channels are known to be expressed on smooth muscle cells as well as nerve cells and secretive cells, thus, some possible side effects are raised. However, the various cell types have specific transcript variants and auxiliary subunits.26,27 The specificity would lower the side effects. Blood pressure has been an issue for the side effects of BKCa channel activators as smooth muscles relaxants. However, the smooth muscle cells of the bladder have spontaneous action potentials that occur due to voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. These channels make the bladder smooth muscle cells easily respond to external stimuli compared to the smooth muscle cells on blood vessels.28 In fact, it was reported that two kinds of benzofuroindole derivatives activated BKCa channels in the smooth muscles of the bladder but not of the arteries in rats.29,30 In addition, it has been revealed that there are no BKCa channels on the cellular membrane of adult cardiomyocytes. Instead, mitochondrial BKCa channels show protective effects against cardiac infarction.31

Several BKca channel openers have been developed, including the oxindole derivative BMS-204352,32 bisarylurea NS1608,33 benzimidazolin-2-one NS1619,34 bisarylthiourea NS11021,35 and the benzofuroindole derivative CTBIC.36 Many compounds showed potent activities in a concentration-dependent manner; however, their further study was not progressed on the clinical state yet. On the basis of the aforementioned findings and previous BKCa channel knockout results in an OAB animal model24 as well as reported BKCa channel activators, we attempted to develop a novel BKCa channel activator.

To identify BKCa channel activators, we screened a chemical library, named GPCR Library, in the Korea Chemical Bank library. This library is a collection of 8364 unique chemical compounds potentially targeting G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR). 5-Oxo-1-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazoline-3-carboxylic acid (3) was identified as a new chemotype activator with moderately potent BK channel-opening activity. On the basis of a molecular simulation study with known BKCa channel openers (Table S1 and Figure S1) and medicinal chemistry perspective, the hit compound has a unique structure motif, which prompted us to optimize it.

Herein, we report the synthesis and biological evaluation of a series of novel 5-oxo-N-phenyl-1-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazoline-3-carboxamide derivatives for potential use as BKCa channel activators in clinical applications.

A series of 1-thioxo-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazolin-5(4H)-one derivatives (compounds 3, 4, and 5) was synthesized according to Scheme 1. Commercially available methyl 2-aminobenzoate (1) was treated with thiophosgene, resulting in an isothiocyanate intermediate (2), followed by cyclization with methyl 2-cyanoacetate and sulfur to produce the corresponding ester compound. The ester was then hydrolyzed under basic conditions to the corresponding carboxylic acid (3). The amide coupling reaction of carboxylic acid (3) with HATU and ammonia solution resulted in the formation of a primary amide (4). EDCI coupling of carboxylic acid (3) with benzylamine resulted in benzyl amide (5).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 1-Thioxo-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazolin-5(4H)-one Derivatives 3–5.

Reagents and conditions: (a) thiophosgene, triethylamine, THF, 0 to 25 °C, 1 h, 99%; (b) methyl 2-cyanoacetate, sulfur, triethylamine, DMF, 50 °C, 1 h, 63%; (c) NaOH, THF, H2O, 25 °C, 12 h, 42%; (d) 7 M NH3 in MeOH, HATU, 1-hydroxybenzotriazole, DIPEA, DMF, 25 °C, 24 h, 54%; (e) benzylamine, EDCI, 1-hydroxybenzotriazole, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 18 h, 15%.

The synthesis of 5-oxo-N-phenyl-1-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazoline-3-carboxamide derivatives is depicted in Scheme 2. Commercially available cyanoacetic acid (7) was coupled with aniline derivatives (6) to produce cyanoacetamide intermediates (8). Diverse amide derivatives (11a–g and 12a–j) were obtained in two steps from methyl 2-aminobenzoate derivatives following the procedure depicted in Scheme 1. The primary amine of compound 9 was converted to the isothiocyanate intermediate (10). Subsequently, cyclization of intermediate 10 with cyanoacetamide (8) and sulfur gave the desired ring-closure compounds (11a–g and 12a–j). The synthesized compounds were evaluated for their BKCa channel activation potential using a cell-based fluorescence assay. NS11021 was used as the reference since its potency and working mechanism on the BKCa channel were reported.35,37 The fluorescence signals were normalized by their initial values before channel activation to eliminate the influence of natural fluorescence from chemicals into relative fluorescence units (RFUs). Potency was determined on the basis of the initial velocity of channel activation (vi) and apparent EC50 value as obtained from fitting the vi data in a dose–response curve [y = vi,max/{1 + 10^(EC50 – x)p}], where p is a constant). The vi value means the RFUs change for 4 s at the start of the channel opening (vi = {RFU(t=24s) – RFU(t=20s)}/4 s) to determine how fast the compounds work on the channels. The apparent EC50 value indicated the sensitivity of each compound. Also, ΔRFU at 6 μM was measured to interpret their activity retentions (Tables 1–3). ΔRFU refers to a changed value for 80 s after channel opening starts (ΔRFU = {RFU(t=100s) – RFU(t=20s)}/{RFU(t=100s)veh – RFU(t=20s)veh}). Thus, the ΔRFU value was to examine the extent and retention of the activity of each compound. In vitro activity details of compounds were indicated in the Supporting Information page S58.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Target Compounds 11a–g and 12a–j.

Reagents and conditions: (a) EDCI, 1-hydroxybenzotriazole, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 18 h, 35–83%; (b) thiophosgene, triethylamine, THF, 0 to 25 °C, 1 h, 96–99%; (c) sulfur, triethylamine, DMF, 50 °C, 1 h, 5–64%.

Table 1. In vitro Activities of 1-Thioxo-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazolin-5(4H)-one Derivatives.

Table 3. In Vitro Characterizations of Compounds 11g and 12a–j.

Compound 3 was found to be a novel hit with moderate BKa channel activation (vi = 0.38 at 6 μM (channel opening velocity), EC50 = 12.72 μM, and ΔRFU = 1.38 at 6 μM (channel activity increase for 80 s)). Its primary amide (4), benzyl amide (5), and anilide (11a) were synthesized and evaluated for their BKCa potency (channel activation), and the results are summarized in Table 1. Anilide (11a) increased channel activation (vi = 0.42 at 6 μM and ΔRFU = 1.03 at 6 μM), while other derivatives (4, 5) showed lower potency (vi of 0.32 and 0.26 at 6 μM, ΔRFU of 0.96 and 1.10 at 6 μM, respectively). On the basis of these data, we further investigated the structure–activity relationship of the 11a anilide analog.

To determine the substitution effects on 1-thioxo-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazolin-5(4H)-one, we introduced several functional groups including an electron-donating group such as a methyl group (11b) and an electron-withdrawing group such as a chloro (11c) or a bromo group (11d) at the 8-position of the phenyl ring. In addition, methyl (11e), chloro (11f), and bromo (11g) groups were introduced at the 7-position. As shown in Table 2, compounds 11b, 11c, 11d, 11e, and 11f resulted in slight activity increases (vi of 0.23–0.84 at 6 μM and ΔRFU of 1.03–1.56 at 6 μM). Fortunately, compound 11g showed significant improvement in channel-opening activity with vi of 5.51 at 6 μM, EC50 of 12.33 μM, and ΔRFU of 3.83 at 6 μM. Thus, it appears that the 7-bromo substituent on the 1-thioxo-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazolin-5(4H)-one side is essential for channel-opening activity. Therefore, we fixed the 7-bromo substituent, compound 11g, in the tricyclic system and further modified the anilide position.

Table 2. In Vitro Characterizations of 5-oxo-N-Phenyl-1-thioxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazoline-3-carboxamide Derivatives.

As a next step, we synthesized diverse analogs on the anilide side, evaluated their activities, and summarized the results (Table 3). Replacement of the simple phenyl (11g) with the ortho-methyl group (12a) resulted in an increase in channel currents (vi = 9.40 at 6 μM, EC50 = 4.60 μM, ΔRFU = 3.68 at 6 μM). Further, the meta-substituted compound 12b (vi = 9.77 at 6 μM, EC50 = 5.74 μM, ΔRFU = 4.98 at 6 μM) was more potent than the ortho-methyl-substituted one (12a). This result prompted us to further modify the meta-position. Replacement of meta-methyl (12b) with meta-methoxy (12d) and meta-hydroxy (12e) resulted in a decrease of activation (12d, vi = 6.00 at 6 μM, EC50 = 6.60 μM, ΔRFU = 3.35 at 6 μM; 12e, vi = 4.03 at 6 μM, EC50 = 11.22 μM, ΔRFU = 4.88 at 6 μM). Halide substituted compounds (12f–i) showed significant improvement. Among the halide substituted compounds, the meta-trifluoromethyl compound 12h exhibited the highest potency for channel activity with vi of 16.77 at 6 μM and EC50 of 2.89 μM. Compound 12i was less potent than 12h (12i, vi = 14.78 at 6 μM, EC50 = 3.82 μM), whereas compound 12j, which has a 3,5-di(trifluoromethyl) substituent, displayed low activity with vi of 2.08 at 6 μM and EC50 of 17.29 μM.

As shown in Figure 1, all synthesized compounds were compared, and we selected 12f and 12h, which showed a good EC50 value and initial velocity, for further evaluation.

Figure 1.

. In vitro activities of 1-thioxo-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazolin-5(4H)-one derivatives in a cell-based fluorescence assay. (A) Initial velocity of channel activation was obtained for the first 4 s after BKCa channel stimulation. Compounds were prepared at a concentration of 6 μM. (B) Apparent EC50 was obtained from the initial velocity of channel activation by fitting data in a dose–response curve, y = Amin + (Amax – Amin)/(1 + 10^{(log EC50 – x)p}). NS11021 was used as a positive control. Each bar represents the mean, and each error bar is the SEM (n = 3). NA, not applicable.

From the in vitro data, 12f and 12h were further evaluated for their liver microsomal stability (Table 4) and plasma protein binding (for 12h). Although 12f showed moderate liver microsomal stability with 56% of the parent remaining after 30 min of incubation in human liver microsomes, 12h showed better liver microsomal stability with 76% of the parent remaining after exposure to the same conditions. We could also expect good metabolic stability in rat from in vivo PK study (Table 5). Thus, meta-(trifluoromethyl)-substituted compound 12h was selected for further optimization.

Table 4. Liver Microsomal Stability of Compounds 12f and 12ha.

| liver microsomal stability (human) | results |

|---|---|

| 12f | 56% parent remained after 30 min of incubation |

| 12h | 76% parent remained after 30 min of incubation |

Buspirone was used as a positive control [4% (parent) remained after 30 min of incubation].

Table 5. Pharmacokinetic Properties of Compound 12h in Male Rats.

| parameter | IV (5 mg/kg)a | PO (10 mg/kg)a |

|---|---|---|

| Tmax (h) | NA | 6.67 ± 2.31 |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | NA | 1.19 ± 0.35 |

| T1/2 (h) | 6.59 ± 3.86 | 8.5 ± 3.57 |

| AUC0–8h (μg·h/mL) | 26.8 ± 20.01 | 13.64 ± 2.93 |

| AUC∞ (μg·h/mL) | 30.63 ± 25.88 | 17.2 ± 3.52 |

| CL (L/kg/h) | 0.27 ± 0.21 | NA |

| VSS (L/kg) | 1.83 ± 1.15 | NA |

| F (%) | NA | 25.45 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Compound 12h activated BKCa channels in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2A). The initial velocity of channel activation (vi) of 1 μM 12h was increased significantly, and the value was similar to that of 5 μM NS11021. In the cell-based assay system, the effects of 12h started to saturate below 5 μM (Figure 2B). The results of other compounds are displayed in the Supporting Information pages S59–S67.

Figure 2.

Activation effects of compound 12h on BKCa channels in a dose-dependent manner. (A) Raw trace of RFU following treatment with 12h at a concentration range of 0.2–6 μM. NS11021 (5 μM) was used as a positive control. (B) Initial velocity of channel activation upon treatment with 12h in a range of concentrations during the first 4 s. Each dot and bar represents the mean, and each error bar is the SEM (n = 3). A Student’s t-test was performed for statistical analysis; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared to the vehicle group.

To observe the activation mode of 12h on the BKCa channel, we measured macroscopic currents directly using patch-clamp recordings. When we drew the conductance–voltage relationship curve of the BKCa channel, perfusion with 12h shifted the curve to the left at a single concentration of 10 μM (Figure 3A,B). By Boltzmann function fitting, the voltage at half activation (V1/2) was shifted to the left by 42.6 ± 7.35 mV, indicating that the channels opened more easily at a lower membrane depolarization in the presence of 12h (Figure 3C). Because the BKCa channel was closed at the hyperpolarized membrane potential and activated by the depolarization of membrane potential with 12h, the channels could be opened with a smaller voltage stimulation. V1/2 was related to the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of channel activation by the Nernst equation, ΔG = −zFV1/2.38 The negative ΔV1/2, left-shifted, indicates a decrease in ΔG, and the channel activation was more stabilized by 12h binding (−1.92 kcal/mol). The maximum conductance (Gmax) increased 1.5 ± 0.11-fold compared to the vehicle group, implying either an increase in channel open probability or single-channel conductance (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Activation effects of compound 12h on macroscopic currents of BKCa channels. (A–D) The current was recorded in an outside-out configuration with 3 μM intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Ionic currents were elicited with 100 ms voltage step pulses from −80 to 200 mV in 10 mV increments. The holding voltage was 100 mV. Each trace corresponds to a voltage step. (A) Representative current trace after treatment with 10 μM 12h. (B) Conductance (G)–voltage (V) relationship curve after treatment with 10 μM 12h. (C) V1/2 (voltage at half activation) shift of 12h at 10 μM. (D) The maximum conductance (Gmax) increased with 10 μM 12h compared to the vehicle group. (E–H) The current was recorded in an inside-out configuration with 3 μM intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Ionic currents were elicited with 100 ms voltage step pulses from 80 to −200 mV in 10 mV decrements. The holding voltage was −100 mV. (E) Representative current trace after treatment with 10 μM 12h. (F) G–V relationship curve after treatment with 10 μM 12h. (G) V1/2 shift of 12h at 10 μM. (H) The maximum conductance (Gmax) increased with 10 μM 12h compared to the vehicle group. G was obtained from the mean outward current for 5 ms after saturation. The values were normalized by the maximum conductance of the vehicle group fitted by the Boltzmann function; G/Gmax = {(Gmax – Gmin)/(1 + exp[(V1/2 – V)/k])} + Gmin, where k is a constant. The dots and bars represent the means, and the error bars are SEMs (n = 4). The Student’s t-test was performed for statistical analysis; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared to the vehicle group.

Although the compounds were assumed to be accessed from the outside of the cellular membrane, the effects on the inside of the membrane were also examined (Figure 3E). The G–V curve shifted significantly, but the degree decreased compared to the that of the outside-out configuration (ΔV1/2 = 7.5 ± 2.20 mV) (Figure 3F). The Gmax increased 1.3 ± 0.07-fold compared to the vehicle group at the inside-out configuration (Figure 3G). One possible explanation is that the compounds are membrane permeable and thus had access to the binding sites located on the outside of the membrane.

To observe the effects of 12h on channel gating kinetics, the time constants of activation (τactivation) and deactivation (τdeactivation) were derived using the exponential equation from the outward current with voltage stimulation and tail current without voltage stimulation, respectively. Both τactivation and τdeactivation were significantly affected by 12h. This indicated that the channel opening was shortened, and the channel closing was delayed with 12h binding (Figure 4A–C). The decrease in τactivation disappeared when 12h was perfused to the inside of the membrane with an inside-out configuration, while τdeactivation values were significantly affected by 12h (Figure 4D–F). The effects on channel gating kinetics were dependent on the membrane side on which the compound perfused.

Figure 4.

Effects of compound 12h on BKCa channel gating. (A) Representative current trace following treatment with 10 μM 12h on the outside of the membrane at 170 mV pulse stimulation. (B) Time constant of activation (τactivation). (C) Time constant of deactivation (τdeactivation). (D) Representative current trace following treatment with 10 μM 12h on the inside of the membrane. (E) Time constant of activation (τactivation) for the inside-out patch. (F) Time constant of deactivation (τdeactivation) for the inside-out patch. The outward current was analyzed for τactivation on voltage simulation. The tail current after the peak was analyzed for τdeactivation after the end of the voltage pulse. The time constant (τ) was obtained by fitting every independent data set using the single exponential function (y = A exp(−t/τ) + C). Each dot represents the mean, and each error bar is the SEM (n = 4–5). The Student’s t-test was performed for statistical analysis; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, compared to the vehicle group at the same voltage pulse.

The pharmacokinetic results of 12h in male rats are summarized in Table 5. Compound 12h showed good blood concentration (AUC, 26.8 μg·h·mL–1), a long half-life (6.59 h), and reasonable oral bioavailability (25.45%). The plasma protein binding study was also conducted. Compound 12h showed >97% protein binding in rat and human samples (Table S2).

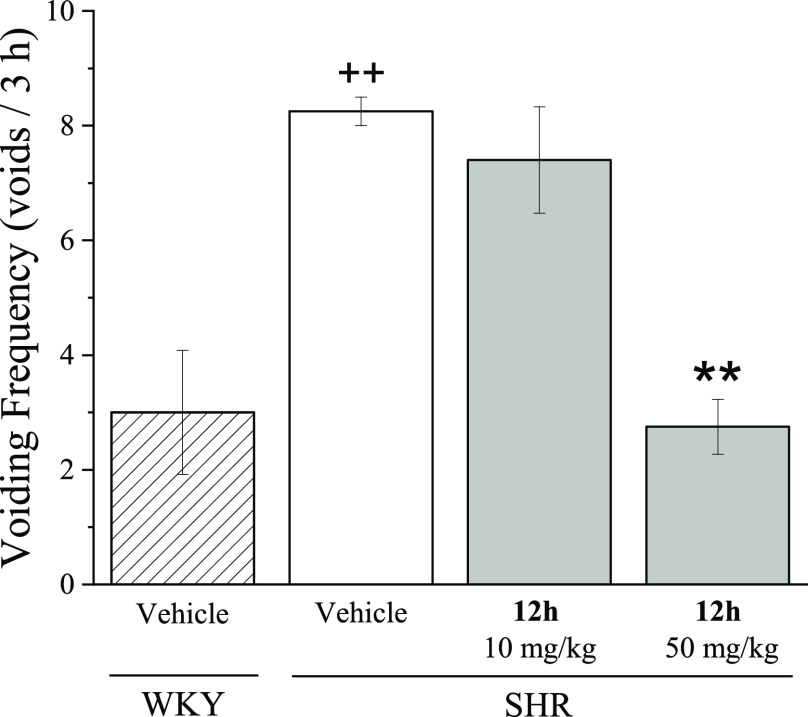

The in vivo therapeutic effects of 12h were investigated in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) that had OAB symptoms, following oral administration (10 and 50 mpk). Wistar-Kyoto rats (WKYs) were used as healthy animal controls, and the voiding frequency was increased in SHRs by more than 2.8-fold compared to WKYs. At a 10 mpk dose, compound 12h did not showed a meaningful voiding frequency reduction; presumably, high protein binding rate is one of the reasons. However, compound 12h significantly decreased the voiding frequency in SHRs at 50 mg/kg by 33%, which was close to that of the normal group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of compound 12h on voiding behavior of spontaneous hypertensive rats. Voiding frequency was measured for 3 h after oral administration of 12h in WKYs and SHRs. The vehicle was composed of DMSO/PEG400/distilled water (v/v, 5:40:55). Each bar represents the mean, and each error bar is the SEM (n = 4–5). One-way ANOVA was performed for statistical analysis; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, compared to the vehicle group of the SHRs; +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01, and +++p < 0.001, compared to the vehicle group of the WKYs.

In summary, a series of new 1-thioxo-1H-thiazolo[3,4-a]quinazolin-5(4H)-one derivatives was identified and evaluated for their ability to activate BKCa channels. Among them, heterocyclic derivatives with bromo substituents were found to be potent BKCa channel openers. Compound 12h showed good BKCa channel activation as it shifted the G–V relationship of the channels and increased the maximum conductance. In addition, 12h fastened the channel opening and delayed channel closing. Moreover, 12h showed good oral pharmacokinetic results (AUC and half-life) and efficacy in vivo using an SHR model.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a GIST Research Project grant funded by the GIST in 2021 to C.-S.P. as well as grants from the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (MSIP)/National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (2021R1A2C2008062). This work was also supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korean government (MOTIE) (20202020800330, Development and demonstration of energy efficient reaction–separation–purification process for fine chemical industry). We would like to express our gratitude to Prof. Jaebong Kim of Hallym University for providing X. laevis from the Korean Xenopus Resource Center for Research (ROK).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- G–V relationship

conductance–voltage relationship

- EC50

half-maximal effective concentration

- AUC

area under the curve

- CL

clearance

- F

bioavailability.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00070.

Experimental procedures, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS spectra, HPLC assessment of purity for all new compounds, and in vitro assay results (PDF)

Author Contributions

‡ E.J.B. and H.J. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Milsom I.; Gyhagen M. The prevalence of urinary incontinence. Climacteric 2019, 22 (3), 217–222. 10.1080/13697137.2018.1543263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian V. A.; Drutz H. P.; Al-Badr A. Urinary incontinence as a worldwide problem. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2003, 82 (3), 327–338. 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerruto M. A.; Asimakopoulos A. D.; Artibani W.; Del Popolo G.; La Martina M.; Carone R.; Finazzi-Agro E. Insight into new potential targets for the treatment of overactive bladder and detrusor overactivity. Urol. Int. 2012, 89 (1), 1–8. 10.1159/000339251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple C. R.; Cardozo L.; Steers W. D.; Govier F. E. Solifenacin significantly improves all symptoms of overactive bladder syndrome. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006, 60 (8), 959–966. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham N.; Goldman H. B. An update on the pharmacotherapy for lower urinary tract dysfunction. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2015, 16 (1), 79–93. 10.1517/14656566.2015.977253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vij M.; Drake M. J. Clinical use of the beta3 adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder syndrome. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2015, 7 (5), 241–248. 10.1177/1756287215591763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglio D.; Tobin G. Muscarinic receptor subtypes in the lower urinary tract. Pharmacology 2009, 83 (5), 259–269. 10.1159/000209255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chess-Williams R. Muscarinic receptors of the urinary bladder: detrusor, urothelial and prejunctional. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 2002, 22 (3), 133–145. 10.1046/j.1474-8673.2002.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilvebrant L.; Hallen B.; Larsson G. Tolterodine-a new bladder selective muscarinic receptor antagonist: preclinical pharmacological and clinical data. Life Sci. 1997, 60 (13–14), 1129–1136. 10.1016/S0024-3205(97)00057-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welk B.; Richardson K.; Panicker J. N. The cognitive effect of anticholinergics for patients with overactive bladder. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18 (11), 686–700. 10.1038/s41585-021-00504-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte L. P.; Mulder W. M.; de la Rosette J. J.; Michel M. C. Muscarinic receptor antagonists for overactive bladder treatment: does one fit all?. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2009, 19 (1), 13–19. 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32831a6ff3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. M.; Bentcheva-Petkova L. M.; Liu L.; Hristov K. L.; Chen M.; Kellett W. F.; Meredith A. L.; Aldrich R. W.; Nelson M. T.; Petkov G. V. Beta-adrenergic relaxation of mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle in the absence of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2008, 295 (4), F1149–1157. 10.1152/ajprenal.00440.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi O.; Chapple C. R. Beta3-adrenoceptors in urinary bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007, 26 (6), 752–756. 10.1002/nau.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basra R. K.; Wagg A.; Chapple C.; Cardozo L.; Castro-Diaz D.; Pons M. E.; Kirby M.; Milsom I.; Vierhout M.; Van Kerrebroeck P.; Kelleher C. A review of adherence to drug therapy in patients with overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2008, 102 (7), 774–779. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson W. F. Potassium channels in the peripheral microcirculation. Microcirculation 2005, 12 (1), 113–127. 10.1080/10739680590896072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallotta B. S.; Magleby K. L.; Barrett J. N. Single channel recordings of Ca2+-activated K+ currents in rat muscle cell culture. Nature 1981, 293 (5832), 471–474. 10.1038/293471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald S. H.; Ruth P.; Knaus H. G.; Shipston M. J. Increased large conductance calcium-activated potassium (BK) channel expression accompanied by STREX variant downregulation in the developing mouse CNS. BMC Dev. Biol. 2006, 6, 37. 10.1186/1471-213X-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayden J. E.; Nelson M. T. Regulation of Arterial Tone by Activation of Calcium-Dependent Potassium Channels. Science 1992, 256 (5056), 532–535. 10.1126/science.1373909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras G. F.; Castillo K.; Enrique N.; Carrasquel-Ursulaez W.; Castillo J. P.; Milesi V.; Neely A.; Alvarez O.; Ferreira G.; Gonzalez C.; Latorre R. A BK (Slo1) channel journey from molecule to physiology. Channels (Austin) 2013, 7 (6), 442–458. 10.4161/chan.26242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatta S.; Nimmagadda D.; Xu X.; O’Rourke S. T. Large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels: structural and functional implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 110 (1), 103–116. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorneloe K. S.; Meredith A. L.; Knorn A. M.; Aldrich R. W.; Nelson M. T. Urodynamic properties and neurotransmitter dependence of urinary bladder contractility in the BK channel deletion model of overactive bladder. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2005, 289 (3), F604–610. 10.1152/ajprenal.00060.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner M. E.; Knorn A. M.; Meredith A. L.; Aldrich R. W.; Nelson M. T. Frequency encoding of cholinergic- and purinergic-mediated signaling to mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle: modulation by BK channels. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 292 (1), R616–624. 10.1152/ajpregu.00036.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner T. J.; Bonev A. D.; Nelson M. T. Ca2+-activated K+ channels regulate action potential repolarization in urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 273 (1), C110–C117. 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.C110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith A. L.; Thorneloe K. S.; Werner M. E.; Nelson M. T.; Aldrich R. W. Overactive bladder and incontinence in the absence of the BK large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279 (35), 36746–36752. 10.1074/jbc.M405621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov K. L.; Afeli S. A.; Parajuli S. P.; Cheng Q.; Rovner E. S.; Petkov G. V. Neurogenic detrusor overactivity is associated with decreased expression and function of the large conductance voltage- and Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels. PLoS One 2013, 8 (7), e68052 10.1371/journal.pone.0068052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle B. D.; Braun A. P. The regulation of BK channel activity by pre- and post-translational modifications. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 316. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Yan J. Modulation of BK channel function by auxiliary beta and gamma subunits. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2016, 128, 51–90. 10.1016/bs.irn.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkov G. V. Central role of the BK channel in urinary bladder smooth muscle physiology and pathophysiology. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2014, 307, R571–R584. 10.1152/ajpregu.00142.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butera J. A.; Antane S. A.; Hirth B.; Lennox J. R.; Sheldon J. H.; Norton N. W.; Warga D.; Argentieri T. M. Synthesis and potassium channel opening activity of substituted 10H-benzo[4,5]furo[3,2-b]indole-and 5,10-dihydro-indeno[1,2-b]indole-1-carboxylic acids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 2093–2097. 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dela Peña I. C.; Yoon S. Y.; Kim S. M.; Lee G. S.; Ryu J. H.; Park C.-S.; Kim Y. C.; Cheong J. H. Bladder-Relaxant Properties of the Novel Benzofuroindole Analogue LDD175. Pharmacology. 2009, 83, 367–378. 10.1159/000218739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H.; Lu R.; Bopassa J. C.; Meredith A. L.; Stefani E.; Butera L. T. mitoBKCa is encoded by the Kcnma1 gene, and a splicing sequence defines its mitochondrial location. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110 (26), 10836–10841. 10.1073/pnas.1302028110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewawasam P.; Gribkoff V. K.; Pendri Y.; Dworetzky S. I.; Meanwell N. A.; Martinez E.; Boissard C. G.; Post-Munson D. J.; Trojnacki J. T.; Yeleswaram K.; Pajor L. M.; Knipe J.; Gao Q.; Perrone R.; Starrett J. E. Jr The synthesis and characterization of BMS-204352 (MaxiPostTM) and related 3-fluorooxindoles as openers of maxi-K potassium channels. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12 (7), 1023–1026. 10.1016/S0960-894X(02)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemer C.; Bushfield M.; Newgreen D.; Grissmer S. Effects of NS1608 on MaxiK channels in smooth muscle cells from urinary bladder. J. Membr. Biol. 2000, 173 (1), 57–66. 10.1007/s002320001007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X.; Xi L.; Wang H.; Huang X.; Ma X.; Han Z.; Wu P.; Ma X.; Lu Y.; Wang G.; Zhou J.; Ma D. The potassium ion channel opener NS1619 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in A2780 ovarian cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 375 (2), 205–209. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne J. J.; Nausch B.; Olesen S. P.; Nelson M. T. BK channel activation by NS11021 decreases excitability and contractility of urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 298 (2), R378–384. 10.1152/ajpregu.00458.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormemis A. E.; Ha T. S.; Im I.; Jung K. Y.; Lee J. Y.; Park C. S.; Kim Y. C. Benzofuroindole analogues as potent BK(Ca) channel openers. Chembiochem. 2005, 6 (10), 1745–1748. 10.1002/cbic.200400448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman M. E.; Vouga A. G.; Rothberg B. S. Molecular mechanism of BK channel activation by the smooth muscle relaxant NS11021. J. Gen. Physiol. 2020, 152 (6), e201912506 10.1085/jgp.201912506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orio P.; Latorre R. Differential effects of beta 1 and beta 2 subunits on BK channel activity. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005, 125 (4), 395–411. 10.1085/jgp.200409236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.