Abstract

Background:

The COVID-19 infection can result in prolonged illness in those infected irrespective of disease severity. Infectious diseases are associated with a higher risk of mood disorders. A better understanding of convalescence, symptom duration, as well as the prevalence of depression among recovering patients, could help plan better care for the survivors of COVID-19.

Aim:

The study aimed to estimate the immediate and short-term prevalence of major depressive disorder and its correlation with continued symptom experience.

Methods:

In this non-interventional, observational, and cross-sectional telephone survey study, 273 participants were included from January 2021 to April 2021 and 261 completed follow-up by July 2021. The symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing and during the two phone calls were captured and the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 item (PHQ-9) version was administered.

Results:

During the immediate and short-term period following COVID-19, 144/261 (55.1%) and 71/261 (27.2%) patients had not returned to usual health, respectively, and 33/261 (12.8%) and 13/261 (5%) of the patients developed depression, respectively. The binary logistic regression analysis revealed that the independent predictors of depression in short-term period following COVID-19 were comorbid diabetes mellitus (OR = 32.99, 95% CI- 2.19-496, P = 0.011), number of symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing (OR = 1.89, 95% CI 1.23-1.92, P = 0.018), and number of symptoms at short-term period following COVID-19 (OR = 2.85, 95% CI 1.47-5.51, P = 0.002).

Conclusions:

Individuals with a greater number of symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing, with post-COVID symptoms persisting 3 months later, and those who have comorbid diabetes mellitus, are at greater odds to have comorbid depression.

Keywords: COVID-19, depression, post-COVID syndrome, prevalence

BACKGROUND

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues unabated the world over since the end of 2019. Eighty percent of individuals afflicted with COVID-19 have a mild to moderate disease.[1] A US outpatient multi-center telephone survey study with mild COVID-19 patients confirmed that 35% of symptomatic patients had reported not having returned to their usual state of health after a median of 16 days from reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing date.[2] Literature review informs that in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients, two-thirds are symptom-free by 14 days after symptom onset, and 90% are symptom-free by 21 days.[3] Among cohorts of hospitalized patients, the prevalence of residual symptoms at the end of 60 days was 87%.[1] Another study reported that patients hospitalized for severe COVID-19 frequently suffer long-term symptoms. This same study also found that more than 50% of home-quarantined, mild to moderately ill patients with COVID-19 continued to have symptoms even 6 months after infection.[4] Therefore, COVID-19 can result in prolonged illness among those infected with either mild or severe disease severity. Post-COVID syndrome is a term used to describe the presence of symptoms even weeks to months after having a COVID-19 infection irrespective of the viral status. Experiencing more than five symptoms during the first week of illness was associated with post-COVID syndrome (odds ratio = 3.53 (2.76-4.50)).[5] Depending on the duration of symptoms, post-COVID syndrome is divided into two stages: post-acute COVID where symptoms extend beyond 3 weeks, but less than 12 weeks, and chronic COVID, where symptoms extend beyond 12 weeks.[1]

Infectious diseases are associated with a higher risk of mood disorders depending on severity. Findings from the SARS-CoV-1 epidemic revealed depressive symptoms among patients after the infection.[6] A systematic review and meta-analysis done early on during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that the pooled prevalence of depression was 28% (95% confidence interval: 23-32%) in those infected with COVID-19.[7]

Experts anticipate a huge after-wave of patients surviving COVID-19 may suffer from the major depressive disorder (hereafter referred to as depression).[8,9] The primary objective of this study was to estimate the immediate and short-term prevalence of depression and its correlation with continued symptom experience in patients recovering from COVID-19.

The secondary objective was to explore if COVID-19 patients continue to experience disease symptoms at 14-21 days after the RT-PCR test date as well as after 90-97 days from the aforementioned period and if demographic variables of age, gender, or any disease comorbidity were associated with prolonged disease experience.

By conducting this study, we attempted to provide a few leads to help address the following clinical questions: 1) What is the prevalence of depression in immediate and short-term periods following COVID-19 infection? 2) How many patients continue to experience symptoms of COVID-19 over the immediate and short-term periods? 3) Is there any correlation between continued symptom experience and depression?

Hence, a better understanding of COVID-19 convalescence, symptom duration as well as prevalence of depression among patients recovering from COVID-19 could help plan better care for the survivors of COVID-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The hospital institutional ethics committee approved this study on 30 December 2020. The study was a non-interventional, observational, cross-sectional telephone survey study conducted at a tertiary care private hospital in a megalopolis of India. Subjects were included in the study from 08 January 2021 until mid-April 2021 and the last patient follow-up completed in mid-July 2021. The hospital laboratory provided the list containing the name, age, gender, and phone number of patients testing positive on RT-PCR for COVID-19. Asymptomatic, mild, or moderate severity of COVID-19 disease at the time of RT-PCR testing in a subject aged 18 years or greater at time of RT-PCR testing done at the hospital with a positive test report were eligible for the study. The subject who remained hospitalized for 21 days after testing positive for RT-PCR, if they could not speak coherently, or if they had previously had COVID-19, were all excluded from the study. Pre-screened subjects were contacted via telephone initially 14-21 days after testing positive on the RT-PCR test (hereafter referred to as the immediate period following COVID-19) and a verbal informed consent was obtained by the study investigator after explaining the study objective and process. The verbal consent was documented in a short consent form signed by the investigator. The subject was followed up 90-97 days after this initial phone call (hereafter referred to as the short-term period following COVID-19). The study data anonymized for subject identity were updated into a case report form during or immediately following the phone contact. The study was conducted in adherence to the principles of ICH-GCP.

The study had a standard manuscript that was approved by the ethics committee for use by the single coordinator and the two investigators to have a standardized conversation with the subjects both at the time of screening call as well as initial and follow-up phone calls. The language of conversation during the phone call was adapted based on the language best understood by the subject. The PHQ-9 was read out verbatim including the translated versions. This ensured uniformity of the telephone interview in the study for the entire duration. Telephone and in-person assessments using the PHQ-9 yield similar results.[10] There is a validation study that supports telephone administration of the PHQ-9 to assess for the prevalence of MDD in a non-clinical population including for research purposes.[11] Phone interviews were conducted in any of the four languages (English, Hindi, Marathi, or Gujarati). At initial phone contact, subjects issuing their verbal consent were asked to self-report the presence of chronic medical conditions. Subjects were asked to recollect and report the COVID-19–related symptoms experienced at the time of RT-PCR testing and during the phone call, whether symptoms had resolved by the date of the phone call, and whether the patient had returned to their usual state of health. The English or validated translations (in Hindi, Marathi, and Gujarati) of the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 item version (PHQ-9) was administered. The PHQ-9 is a validated, 9-question tool to assess the degree of depression present in an individual.[12] It is available in validated Indian languages; is royalty-free; takes 5 min to complete. The PHQ-9 scores ≥10 were found to be 88% sensitive and 88% specific for detecting a major depressive disorder.[13] For this study, a cutoff score ≥10 on PHQ-9 was used to diagnose patients as having a major depressive disorder.

A previous study by Luo and colleagues found that the prevalence of depression in patients with COVID-19 was 28%. Based on this estimate, with an alpha of 0.05, power of 80%, and delta of 0.08, the estimated sample size after factoring in any missing data was 273. The descriptive statistics included the presentation of data as frequency (percentages) for categorical variables and analyzed the difference in the distribution by Pearson Chi-square and Fisher’s Exact Test. Continuous data were presented as mean [standard deviations (SD)]. The associations were analyzed using binary correlation methods such as Kendall’s Tau coefficient and Spearman’s rank correlation to assess the statistical correlation of the data based on the ranks. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to assess the independent predictor of the dependent variable after adjusting for various other independent variables. The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed). All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 21.0 statistical software.

RESULTS

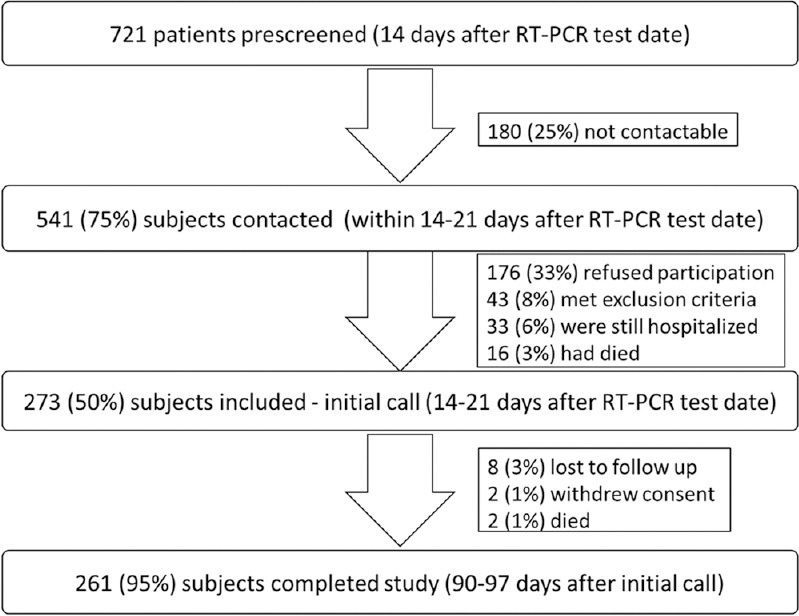

A total of 721 participants were pre-screened, 541 contacted via phone, of which 273 (185 males, 88 females) were finally included in the study. A total of 261 participants (178 males, 83 females) completed the study [see Figure 1 for details]. Only the study completers’ data were included for analysis. The mean age in study completers, for males was 48.5 years ± 15.7 and for females was 49.2 years ± 14.3. Comorbid medical conditions were present in 147/261 (56.3%) patients [see Tables 1-3 for details].

Figure 1.

Details of patients pre-screened, contacted, included and completed in study

Table 1.

Description of study population

| All (n=261) Nb (%) | Male Nb (%) | Female Nb (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||||

| 18-39 | 81 (31.0) | 61 (34.5) | 20 (23.8) | 0.043 |

| 40-59 | 117 (44.8) | 70 (39.5) | 47 (56.0) | |

| ≥60 | 63 (24.1) | 46 (26.0) | 17 (20.2) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 177 (43.7) | |||

| Female | 84 (32.2) | |||

| Number of comorbid conditions | ||||

| None | 114 (43.7) | 86 (48.6) | 28 (33.3) | 0.017 |

| ≤2 | 125 (47.9) | 74 (41.8) | 51 (60.7) | |

| >2 | 22 (8.4) | 17 (9.6) | 5 (5.9) | |

| Number of symptoms at time of RT-PCR testing | ||||

| None | 13 (5.0) | 11 (6.2) | 2 (2.4) | 0.025 |

| 1-5 | 147 (56.3) | 106 (59.9) | 41 (48.8) | |

| 6-10 | 84 (32.2) | 53 (29.9) | 31 (36.9) | |

| >10 | 17 (6.5) | 7.0 (4.0) | 10 (11.9) | |

| Number of symptoms 14 to 21 days after RT-PCR testing (immediate period) | ||||

| None | 117 (44.8) | 85 (48.0) | 32 (38.1) | 0.003 |

| 1-5 | 139 (53.3) | 92 (52.1) | 47 (56.0) | |

| 6-10 | 05 (1.9) | - | 5 (6.0) | |

| >10 | - | - | - | |

| Returned to usual health 14 to 21 days after RT-PCR testing (immediate period) | ||||

| Yes | 117 (44.8) | 85 (48.0) | 32 (38.1) | 0.084 |

| No | 144 (55.2) | 92 (52.0) | 52 (61.9) | |

| Number of symptoms 90 to 97 days after immediate period (short-term period) | ||||

| None | 190 (72.8) | 129 (72.9) | 61 (72.6) | 0.038 |

| 1-5 | 68 (26.1) | 48 (27.1) | 20 (23.8) | |

| 6-10 | 03 (1.1) | - | 03 (3.6) | |

| >10 | - | - | - | |

| Returned to usual health 90 to 97 days after immediate period (short-term period) | ||||

| Yes | 190 (72.8) | 129 (72.9) | 61 (72.6) | 0.538 |

| No | 71 (27.2) | 48 (27.1) | 23 (27.4) | |

| Depression 14 to 21 days after RT-PCR testing (immediate period) | ||||

| No | 228 (87.4) | 159 (89.8) | 69 (82.2) | 0.063 |

| Yes | 33 (12.6) | 18 (10.2) | 15 (17.9) | |

| Depression 90 to 97 days after immediate period (short-term period) | ||||

| No | 248 (95.0) | 170 (96.0) | 78 (92.9) | 0.36 |

| Yes | 13 (5.0) | 7 (4.0) | 06 (7.1) |

Table 3.

Description of the study population at 90-97 days (short-term period) after an immediate period concerning depression

| Depression at short-term period | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No (n=248) Nb (%) | Yes (n=13) Nb (%) | ||

| Age (in years) | |||

| 18-39 | 79 (31.9) | 02 (15.4) | 0.056 |

| 40-59 | 107 (43.1) | 10 (76.9) | |

| ≥60 | 62 (25) | 01 (7.7) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 170 (68.5) | 07 (53.8) | 0.21 |

| Female | 78 (31.5) | 06 (46.2) | |

| Number of comorbid medical conditions | |||

| None | 111 (44.8) | 03 (23.1) | 0.086 |

| ≤2 | 118 (47.6) | 07 (53.8) | |

| >2 | 19 (7.7) | 03 (23.1) | |

| Number of symptoms at time of RT-PCR testing | |||

| None | 13 (5.2) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| 1-5 | 144 (58.1) | 3 (23.1) | |

| 6-10 | 8 (32.3) | 04 (30.8) | |

| >10 | 11 (4.4) | 06 (46.2) | |

| Number of symptoms 14 to 21 days after RT-PCR testing (immediate period) | |||

| None | 115 (46.4) | 02 (15.4) | 0.039 |

| 1-5 | 129 (52.0) | 10 (76.9) | |

| 6-10 | 04 (1.6) | 01 (7.7) | |

| >10 | - | - | |

| Returned to usual health 14 to 21 days after RT-PCR testing (immediate period) | |||

| Yes | 115 (46.4) | 02 (15.4) | 0.042 |

| No | 133 (53.6) | 11 (84.6) | |

| Number of symptoms 90 to 97 days after immediate period (short-term period) | |||

| None | 190 (76.6) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| 1-5 | 57 (23.0) | 11 (84.6) | |

| 6-10 | 01 (.4) | 02 (15.4) | |

| >10 | |||

| Returned to usual health 90 to 97 days after immediate period (short-term period) | |||

| Yes | 190 (76.6) | - | 0.001 |

| No | 58 (23.4) | 13 (100) | |

| Depression 14 to 21 days after RT-PCR testing (immediate period) | |||

| No | 222 (89.5) | 06 (46.2) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 26 (10.5) | 07 (53.8) | |

Table 2.

Description of study population at 14-21 days (immediate period) after RT-PCR testing concerning depression

| Depression at immediate period | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No (n=228) Nb (%) | Yes (n=33) Nb (%) | ||

| Age (in years) | |||

| 18-39 | 73 (32.0) | 08 (24.2) | 0.288 |

| 40-59 | 98 (43.0) | 19 (57.6) | |

| ≥60 | 57 (25.0) | 06 (18.2) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 159 (68.7) | 18 (54.5) | 0.063 |

| Female | 69 (30.3) | 15 (45.5) | |

| Number of comorbid medical conditions | |||

| None | 104 (45.6) | 10 (30.3) | 0.060 |

| ≤2 | 103 (45.2) | 22 (66.7) | |

| >2 | 21 (9.2) | 01 (3.0) | |

| Number of symptoms at time of RT-PCR testing | |||

| None | 13 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| 1-5 | 140 (61.4) | 07 (21.2) | |

| 6-10 | 64 (28.1) | 20 (60.6) | |

| >10 | 11 (4.8) | 06 (18.2) | |

| Number of symptoms 14 to 21 days after RT-PCR testing (immediate period) | |||

| None | 116 (50.9) | 01 (3.0) | 0.001 |

| 1-5 | 112 (49.1) | 27 (81.8) | |

| 6-10 | 5 (15.2) | ||

| >10 | |||

| Returned to usual health 14 to 21 days after RT-PCR testing (immediate period) | |||

| Yes | 116 (50.9) | 1 (3.0) | 0.001 |

| No | 112 (49.1) | 32 (97) | |

The three most frequent symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing were fever, fatigue, and cough present in 178/261 (68%), 141/261 (54.2%), and 123/261 (47.2%), respectively. The three most frequent symptoms during the immediate period following COVID-19 were fatigue, cough, and loss of taste present in 106/261 (40.7%), 44/261 (16.8%), and 33/261 (9.1%), respectively. The three most frequent symptoms during the short-term period following COVID-19 were fatigue, breathlessness, and body ache present in 47/261 (18%), 21/261 (8%), and 21/261 (8%), respectively.

Overall, in 261 study participants, the mean number of symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing was 4.9 [± 3.3], in the immediate period following COVID-19 was 1.3 [± 1.6], and in the short-term period following COVID-19 was 0.7 [± 1.4].

In those found to have depression, the mean number of symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing was 8.4 [±3.4], in immediate period following COVID-19 was 3.5 [±2] and in the short-term period following COVID-19 was 1.9 [±2.1].

During the immediate period following COVID-19, 144/261 (55.1%) patients had not returned to usual health. During this immediate period following COVID-19 infection, 33/261 (12.8%) of the patients developed depression. Out of these 33 depressed patients, 20 (60.6%) had reported hospitalization following COVID-19. Binary logistic regression analysis was done after adjusting for age, gender, number of symptoms at RT-PCR, number of symptoms at immediate period, and all comorbid medical conditions. The number of symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing (OR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.04-1.51, P = 0.018) as well as number of symptoms at immediate period (OR = 3.64, 95% CI 2.31-5.73, P = 0.001) were associated with increased odds of depression in the immediate period following COVID-19.

The short-term period following COVID-19, 71/261 (27.2%) had not returned to usual health. The short-term period following COVID-19 infection, 13/261 (5%) of the patients had depression. Binary logistic regression analysis was done after adjusting for age, gender, number of symptoms at RT-PCR, number of symptoms in the immediate period following COVID-19, and number of symptoms in the short-term period following COVID-19, and all comorbid medical conditions. Comorbid diabetes mellitus (OR = 32.99, 95% CI- 2.19-496, P = 0.011), number of symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing (OR = 1.89, 95% CI 1.23-1.92, P = 0.018), and number of symptoms in short-term period following COVID-19 (OR = 2.85, 95% CI 1.47-5.51, P = 0.002) were associated with increased odds of depression in the short-term period following COVID-19.

DISCUSSION

About the primary objective of this study, it is revealed that 33/261 (12.8%) patients experienced depression in the immediate period following COVID-19 infection and this reduced to 13/261 (5%) in the short-term period. Of the 13 patients who had depression in the short-term period, six (46%) did not have depression in the immediate period. In five of these six patients, they had an increased number of post-COVID symptoms in the short-term period compared to the immediate period. The prevalence rate of depression found in our study is in line with that reported in a scoping review that found that it ranged from 4 to 31% in follow-up studies extending beyond 1 month up to 3 months.[14] The prevalence of mental health symptoms is found to be directly associated with the severity of COVID-19.[9,14] Inconsistent findings are reported for correlation between age and experience of psychological symptoms.[14]

Concerning the secondary objective, 44.8% of patients did not have any continued COVID-19 symptoms experienced in the immediate period following COVID-19 infection and this further increased to 72.8% in the short-term period. A recently published study on 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors found that majority of the patients had good physical recovery at the end of the study period.[15] Despite differences in follow-up period and study design, our study finding is similar in that the majority of patients improved in their physical health over the study duration of 3 months. In our study, fatigue (18%), body ache (8%), breathlessness (8%), and joint pain (6.5%) were the most common symptoms experienced in the short-term period following COVID-19 for those 27.2% of patients with post-COVID syndrome. A scoping review found that fatigue (range 28–87%) was the most commonly reported physical symptom post-COVID in studies up to 3- months.[14] The same scoping review[14] reported that the other two most commonly reported physical health problems were pain (myalgia 4.5–36%), and arthralgia (6.0–27%). Studies found fatigue correlated with the severity of COVID-19 infection.[16,17,18,19,20] Our study had excluded severely ill patients who remained hospitalized for 21 days after RT-PCR testing. Perhaps this could explain the lower prevalence of fatigue reported as a continued symptom experience post-COVID.

The association between depression and physical symptoms is reported by some studies.[17,18,21] Comorbid medical conditions at baseline when infected with COVID-19 have also been reported to be essential for the development of depression.[9,22] Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are the most common comorbid diseases in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.[22] A recent meta-analysis found that people with diabetes and comorbid depression had a 47.9% increase in cardiovascular mortality, 36.8% increase in coronary heart disease, and 32.9% increase in stroke.[23] In our study, persons having diabetes mellitus were at elevated odds (OR = 32.99, 95% CI- 2.19-496, P = 0.011) to have comorbid depression in short term following COVID-19. Complications like stroke and mortality could, therefore, plausibly be mitigated if diabetes mellitus patients who develop depression along with post-COVID symptoms are identified and treated early. The prevalence of depression in this study is in keeping with a scoping review that reports a wide range of 4–31% for prevalence of depression. The prevalence of mental health symptoms including depression varies widely among studies. This may be due to differences in the scales used to measure these outcomes as well as differences between countries in culture and in efforts to cope with the psychological effect of the coronavirus disease.[14] Psychiatric sequelae are reported to be part of the post-COVID symptoms and are known to improve over time.[9] This study too finds that the percentage of patients suffering from depression reduced over the study period.

Limitations

The results may be confounded by several factors as the patients were surveyed over the phone only without clinical and relevant lab investigations. So, a reliance on patient self-reporting with an inherent possibility of a recall bias or incomplete recall is always a confounding variable. Additionally, data about prior treatment or those administered at the time of COVID-19 infection and during follow-up were not probed and this is yet another confounding variable. Exclusion of patients who continued to remain hospitalized at day 21 after RT-PCR testing could have biased the results of this study.

Despite these aforementioned limitations, this study has its strengths that includes adequate sample size and follow-up duration of 3 months along with the use of PHQ-9 scale with a cutoff score of 10 or more to detect depression. A 5% dropout rate in the study that included asymptomatic cases and mimicked the real-world scenario during the pandemic where patients would often consult remotely via telemedicine without access to physical examination and often investigations are the other strengths of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study highlights that individuals with a greater number of symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing, in whom post-COVID symptoms persist 3 months later and those who have comorbid diabetes mellitus, are at greater odds to have depression. In practice, clinicians should actively search for the existence of depression in patients experiencing post-COVID syndrome. Physicians should ensure that post-COVID symptoms, diabetes mellitus, and depression are managed proactively during the post-COVID period to mitigate the negative impact on health outcomes. At the public health level, policymakers need to focus resources on patients with comorbid diabetes mellitus and patients experiencing a greater number of COVID-19 infection symptoms initially at the time of testing, to detect and address early comorbid depression – a disorder that is already known to have a high impact on disability-adjusted life years.[24] Additionally, this study finds that people with reduced severity of illness at baseline had reduced chances of developing post-COVID symptoms and depression. It is known that vaccination against COVID-19 reduces the chance of an individual contracting severe COVID-19 infection. Therefore, it is important to vaccinate in priority the general population to mitigate the chance of severe COVID-19 infection, and thereafter, post-COVID symptoms and depression.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raveendran AV, Jayadevan R, Sashidharan S. Long COVID:An overview. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15:869–75. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, Rose EB, Shapiro NI, Files C, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network —United States, March–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:993–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenhalgh T, Knight M. Long COVID:A primer for family physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102:716–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blomberg B, Mohn KG, Brokstad KA, Zhou F, Linchausen DW, Hansen BA, et al. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat Med. 2021;27:1607–13. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID [published correction appears in Nat Med 2021;27:1116] Nat Med. 2021;27:626–31. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iris ES, Bakker PR. What can psychiatrists learn from SARS and MERS outbreaks? Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:565–6. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30219-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public –A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlis RH, Ognyanova K, Santillana M, Baum MA, Lazer D, Druckman J, et al. Association of acute symptoms of COVID -19 and symptoms of depression in adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e213223. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schou TM, Joca S, Wegener G, Bay-Richter C. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 –A systematic review. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;97:328–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto-Meza A, Serrano-Blanco A, Peñarrubia MT, Blanco E, Haro JM. Assessing depression in primary care with the PHQ-9:Can it be carried out over the telephone? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:738–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine TH, Contractor AA, Tamburrino M, Elhai JD, Prescott MR, Cohen GH, et al. Validation of the telephone-administered PHQ-9 against the in-person administered SCID-I major depression module. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:1001–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9:validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD:The PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanbehzadeh S, Tavahomi M, Zanjari N, Ebrahimi-Takamjani I, Amiri-arimi S. Physical and mental health complications post-COVID-19:Scoping review. J Psychosom Res. 2021;147:110525. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, Wang Q, Ren L, Wang Y, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19:A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:747–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daher A, Balfanz P, Cornelissen C, Muller A, Bergs I, Marx N, et al. Follow up of patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19):Pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease sequelae. Respir Med. 2020;174:106197. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, Adams A, Harvey O, McLean L, et al. Post discharge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection:A cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1013–22. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Townsend L, Dyer AH, Jones K, Dunne J, Mooney A, Gaffney F, et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0240784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Xu H, Jiang H, Wang L, Lu C, Wei X, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of discharged coronavirus disease 2019 patients:A prospective cohort study. QJM. 2020;113:657–65. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamal M, Abo Omirah M, Hussein A, Saeed H. Assessment and characterization of post-COVID-19 manifestations. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e13746. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomasoni D, Bai F, Castoldi R, Barbanotti D, Falcinella C, Mule G, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms after virological clearance of COVID-19:A cross-sectional study in Milan, Italy. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1175–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farooqi AT, Snoek FJ, Khunti K. Management of chronic cardiometabolic conditions and mental health during COVID-19. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15:21–3. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farooqi A, Khunti K, Abner S, Gillies G, Morriss R, Seidu S. Comorbid depression and risk of cardiac events and cardiac mortality in people with diabetes:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;156:107816. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017:A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 [published correction appears in Lancet 2019;393:e44] Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]