Abstract

Background and Aim

Despite efforts in controlling and managing liver diseases, significant health issues remain. This study aims to evaluate the degree of public awareness and knowledge regarding liver health and diseases in Singapore.

Methods

A cross‐sectional, self‐reported, web‐based questionnaire was administered to 500 adult individuals. Questionnaire items pertained to knowledge and awareness of overall liver health, liver diseases and their associated risk factors.

Results

Sixty‐four percent of respondents were ≥35 years old and 54.0% were male. While majority agreed that regular screening was important for liver health (91.2%), only 65.4% attended health screening within recent 2 years. Hepatitis B had more awareness than hepatitis C among the respondents. About 70% agreed the consequences of viral hepatitis included liver cirrhosis, failure, and/or cancer. Yet, only 15% knew hepatitis C is not preventable by vaccination and more than half mistaken hepatitis B and C are transmissible via contaminated or raw seafood. Despite 75% being aware of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, many were not aware of the related risk factors and complications. Awareness of specific screening and diagnostic tests for liver health was poor as one‐fifth correctly identified the diagnostic tests for viral hepatitis. Preferences for doctor's consultation, TV, or newspapers (online) as information channels contrasted those currently used in the public health education efforts.

Conclusions

The levels of understanding of liver diseases, risk factors, and potential complications are suboptimal among the Singapore public. More public education efforts aligned with respondents' information‐seeking preferences could facilitate addressing misperceptions and increase knowledge about liver diseases.

Keywords: hepatitis, knowledge, liver diseases, non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, public health education

Introduction

Liver diseases afflict millions of people worldwide, with more than 2 million deaths caused by complications from chronic viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). 1 , 2 The commonest etiologies of liver failure and/or HCC include viral hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) infection and cryptogenic causes. 1 , 2 , 3 To date, viral hepatitis remains the main etiology of liver cirrhosis and HCC, making up 70% of new HCC cases in 2017. 1 , 2

In Singapore, HCC was ranked as the second most common cancer‐causing mortality in 2018, 4 while liver cirrhosis, attributing to 0.9% of deaths, was ranked within the top 20 causes for years of life lost due to disease. 5 Majority of hospitalized cirrhosis cases (70.2%) in Singapore between 2006 and 2011 were due to chronic viral hepatitis infection. 6 A study exploring the predictors of HCC revealed that approximately 55.6%, 6.2%, and 0.7% of liver cancer patients had history of HBV, HCV, or both infections, respectively. 7

The National Health Survey 2010 conducted by the Ministry of Health, Singapore, reported a higher seroprevalence of HBsAg in the population aged 50–59 years, despite the overall lower seroprevalence in 2010 than 2004. 8 Moreover, despite the significantly lower prevalence and incidence of HCV infection than HBV, complications arising from chronic hepatitis C infection were considered common indications for liver transplants in Singapore. 9

Emerging studies have attributed the increasing incidences of cryptogenic liver cirrhosis and/or HCC to the rising prevalence of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (FLD) (NAFLD). 10 , 11 In Asia, the estimated prevalence rate of NAFLD was 5–18%, whereas the prevalence rate in Singapore was significantly higher at 40.0%. 11 , 12 Patients with NAFLD can develop non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and potentially progress towards cirrhosis and/or liver failure. 10 NAFLD is associated with metabolic risks such as obesity and metabolic syndrome and hence be managed with timely screenings and appropriate lifestyle interventions. 11 The obesity prevalence in 2010 was higher than 2004 (10.8% vs. 6.7%). 13 Approximately 1.7 million Singaporeans (18–69 years) have a body mass index of ≥23 and are at risk of obesity‐related diseases. 14 Intuitively, this portends higher risks for NASH‐related cirrhosis and/or HCC in Singapore in the future.

Thus, liver diseases remain a significant health issue despite efforts in managing liver diseases. Herein, the study will explore the level of awareness and knowledge of the public on liver‐related health and disease as well as to review and identify any gaps in the current public health education campaigns. The outcomes of this study will provide valuable insight about the unmet needs of public education on liver‐related health issues to improve public awareness and knowledge of liver health in Singapore.

Methods

Study population

Eligible respondents, aged 18 years and older and provided informed consent, were invited by email to participate in a web survey. The invitations were sent out by a web‐based consumer panel over a 3 week period in February 2020 until sample quota of 500 was achieved. Respondents who completed the questionnaire received points that can be accumulated and exchanged for prizes as a participation incentive. Awareness and perceptions of liver diseases were explored using a self‐administered survey. The survey questionnaire was developed in English, and all respondents completed the questionnaire in English. Only de‐identified data were collected. The protocol and questionnaire for the survey was granted exemption by Pearl Institutional Review Board for the periods the data will be used in the study. The protocol and questionnaire were part of a regional liver index study (Lee Mei‐Hsuan et al., unpublished data).

Survey questionnaire

The survey consisted of three parts—(i) two questions on the general knowledge of liver health and care; (ii) 13 questions on the knowledge and awareness of liver diseases, risk factors, as well as liver screening and diagnosis; and (iii) two questions regarding the preferred liver information topic and information channel as described later (Appendix I).

Descriptive data analysis of respondents' characteristics and responses to the survey questions were summarized by frequencies and percentages.

Review of public education program

A narrative literature review of Singapore's national public education programs collected data from a range of information channels, including internet search, internet forum, newspaper archive, and public events and/or forums on digestive diseases and/or gastroenterology/hepatology between 2010 and 2019. The topics are consolidated based the following topics “Fatty Liver Disease” (FLD), “General liver health”, “Hepatitis B/C”, “Liver Cancer”, “Other Liver Diseases”, “Prevention and/or risk factors,” and “Screening and Diagnosis.”

Results

Study population characteristics

The age was evenly distributed among the respondents with 64.0% aged 35 years and older, and 54.0% were male. The household income distribution was also even, and 63.6% completed at least university education. A small proportion (5.4%) of respondents did not have any medical insurance (private or public), and 65.4% reportedly attended health screening within recent 2 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents participating in the survey (n = 500)

| Number of respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | ||

| Age group | <25 | 80 | 16.0 |

| 25–34 | 100 | 20.0 | |

| 35–44 | 110 | 22.0 | |

| 45–54 | 110 | 22.0 | |

| ≥55 | 100 | 20.0 | |

| Gender | Male | 270 | 54.0 |

| Female | 230 | 46.0 | |

| Level of education | Primary school | 1 | 0.2 |

| Secondary school | 124 | 24.8 | |

| Vocational certificate | 6 | 1.2 | |

| Junior college | 9 | 1.8 | |

| Polytechnic | 42 | 8.4 | |

| University | 241 | 48.2 | |

| Postgraduate | 77 | 15.4 | |

| Household income | <SGD 2500 | 43 | 8.6 |

| SGD 2500–4499 | 96 | 19.2 | |

| SGD 4500–6499 | 81 | 16.2 | |

| SGD 6500–8499 | 78 | 15.6 | |

| SGD 8500–10 499 | 82 | 16.4 | |

| ≥SGD 10 500 | 107 | 21.4 | |

| Declined to answer | 13 | 2.6 | |

| Medical insurance † | Private insurance—self pay | 358 | 71.6 |

| Private—corporate insurance | 122 | 24.4 | |

| Public insurance (e.g. national [e.g. MediShield] or subsidized) | 347 | 69.4 | |

| None of the above | 27 | 5.4 | |

| Self‐reported last health screening within 2 years | Yes | 327 | 65.4 |

| No | 173 | 34.6 | |

Each respondent could have more than one medical insurance attribute

SGD, Singapore dollar.

Knowledge of liver health and care

On average, at least 40% were knowledgeable about functions of the liver. Majority (85.8%) were aware of the liver's detoxification function (“helps to clean the blood by taking harmful substances out of the blood”). Yet, less than 60% were aware of the other functions of the liver such as the liver produces cholesterol that is needed for normal growth and health (58.6%) and helps with blood clotting (45.6%) (Table S1).

Majority were knowledgeable on the actions to be taken to protect and maintain liver health, with 91.2% agreeing that attending “regular screening to keep a check on the liver” (91.2%) was one such action to protect liver health. At least 3 in 10 people disagreed or were not sure that “drinking alcohol modestly,” “practicing safe sex,” and “taking liver supplements on my own” would help protect and keep the liver healthy (Table S1).

Knowledge and awareness of liver diseases

A higher proportion of respondents heard of hepatitis B (425/500, 85%) than hepatitis C (253/500, 50.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Respondents' understanding and awareness of hepatitis B and C

| Question (correct response) | n, % | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B (n = 425) | Hepatitis C (n = 253) | |||||||||||

| Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | |||||||

| Hepatitis … | ||||||||||||

| …is a bacterial infection (disagree) | 214 | 50.4% | 108 | 25.4% | 103 | 24.2% | 129 | 51.0% | 63 | 24.9% | 61 | 24.1% |

| …is a viral infection (agree) | 229 | 53.9% | 87 | 20.5% | 109 | 25.6% | 145 | 57.3% | 49 | 19.4% | 59 | 23.3% |

| …can cause chronic inflammation of the liver (agree) | 340 | 80.0% | 13 | 3.1% | 72 | 16.9% | 210 | 83.0% | 15 | 5.9% | 28 | 11.1% |

| … can cause liver failure (agree) | 358 | 84.2% | 10 | 2.4% | 57 | 13.4% | 218 | 86.2% | 7 | 2.8% | 28 | 11.1% |

| …can be prevented by vaccination (agree for Hepatitis B; disagree for Hepatitis C) | 319 | 75.1% | 36 | 8.5% | 70 | 16.5% | 169 | 66.8% | 38 | 15.0% | 46 | 18.2% |

| …is airborne (disagree) | 61 | 14.4% | 250 | 58.8% | 114 | 26.8% | 41 | 16.2% | 148 | 58.5% | 64 | 25.3% |

| …is hereditary (disagree) | 135 | 31.8% | 164 | 38.6% | 126 | 29.6% | 78 | 30.8% | 106 | 41.9% | 69 | 27.3% |

| …increases the risk of the development of liver cirrhosis and cancer (agree) | 306 | 72.0% | 17 | 4.0% | 102 | 24.0% | 197 | 77.9% | 7 | 2.8% | 49 | 19.4% |

| Hepatitis … can be transmitted … | ||||||||||||

| a. By touching an infected person (disagree) | 52 | 12.2% | 310 | 72.9% | 63 | 14.8% | 48 | 19.0% | 169 | 66.8% | 36 | 14.2% |

| b. Through sexual intercourse (agree) | 202 | 47.5% | 145 | 34.1% | 78 | 18.4% | 135 | 53.4% | 73 | 28.9% | 45 | 17.8% |

| c. Through blood e.g. contact with an open wound (agree) | 277 | 65.2% | 81 | 19.1% | 67 | 15.8% | 168 | 66.4% | 45 | 17.8% | 40 | 15.8% |

| d. By sharing non‐sterile needles or through needlestick injuries (agree) | 293 | 68.9% | 76 | 17.9% | 56 | 13.2% | 185 | 73.1% | 38 | 15.0% | 30 | 11.9% |

| e. Fecal oral route usually through contaminated food, e.g. an infected person forgets to properly wash hands after using toilet and contaminate the food. (disagree) | 222 | 52.2% | 104 | 24.5% | 99 | 23.3% | 131 | 51.8% | 74 | 29.2% | 48 | 19.0% |

| f. From pregnant mother to her baby at birth (agree) | 257 | 60.5% | 64 | 15.1% | 104 | 24.5% | 147 | 58.1% | 42 | 16.6% | 64 | 25.3% |

| g. By sharing of razors, toothbrushes (agree) | 211 | 49.6% | 121 | 28.5% | 93 | 21.9% | 126 | 49.8% | 66 | 26.1% | 61 | 24.1% |

| h. By receiving tattoos, body piercing from settings with poor infection control standards (agree) | 259 | 60.9% | 90 | 21.2% | 76 | 17.9% | 153 | 60.5% | 51 | 20.2% | 49 | 19.4% |

| i. By eating contaminated or raw seafood, e.g. shellfish (disagree) | 282 | 66.4% | 74 | 17.4% | 69 | 16.2% | 143 | 56.5% | 60 | 23.7% | 50 | 19.8% |

| j. Having received blood (products) before around 1990s (agree) | 174 | 40.9% | 84 | 19.8% | 167 | 39.3% | 108 | 42.7% | 46 | 18.2% | 99 | 39.1% |

| k. Having received long‐term kidney dialysis (agree) | 146 | 34.4% | 113 | 26.6% | 166 | 39.1% | 89 | 35.2% | 70 | 27.7% | 94 | 37.2% |

| l. By mosquito bites (disagree) | 50 | 11.8% | 270 | 63.5% | 105 | 24.7% | 34 | 13.4% | 153 | 60.5% | 66 | 26.1% |

| m. By dining together (e.g. sharing food) with an infected person (disagree) | 110 | 25.9% | 239 | 56.2% | 76 | 17.9% | 74 | 29.2% | 132 | 52.2% | 47 | 18.6% |

Among these respondents, majority agreed hepatitis B and C could cause liver inflammation (HBV: 80.0%; HCV: 83.0%) and liver failure (84.2%; 86.2%) as well as increase risks of liver cirrhosis and cancer (72.0%; 77.9%). About 75% were aware hepatitis B is preventable by a vaccine, while only 15% were aware that there is no available vaccine for hepatitis C (Table 2).

When questioned about the modes of transmission, more than 60% of respondents were aware that the transmission risks included mother‐to‐child transmission (HBV: 60.5%; HCV: 58.1%), blood contact (65.2%; 66.4%), sharing of non‐sterile needles/through needle injuries (68.9%; 73.1%), instead of touching an infected individual (72.9%; 66.8%). However, more than half misperceived “fecal oral route usually through contaminated food” (HBV: 52.2%; HCV: 51.8%) or “eating contaminated raw seafood e.g. shellfish” (66.4%; 56.5%) as modes of hepatitis B and C transmission, and were also unaware that “sexual intercourse” was a transmission risk (52.5%; 46.6%) (Table 2).

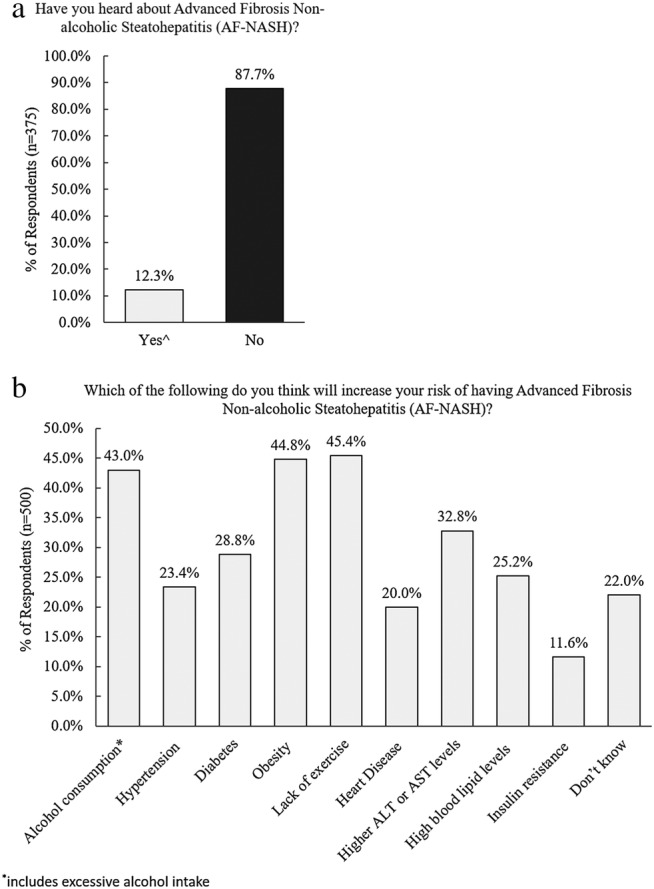

A total of 375 respondents (75%) associated fatty liver and NASH with liver disease. However, only 12.3% were aware of advanced fibrosis NASH (AF‐NASH) (Fig. 1a). The top three risk factors associated with AF‐NASH perceived by the respondents were (i) lack of exercise (45.8%), (ii) obesity (44.8%), and (iii) alcohol consumption or excessive alcohol intake (43.0%); whereas about one‐quarter perceived diabetes (28.8%), high blood lipid levels (25.2%), and hypertension (23.4%) as risk factors of AF‐NASH (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

(a,b) Respondents' awareness towards NASH and its associated risk factors. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Awareness of liver disease complications and diagnostic tests

Table 3 shows the awareness of the respondents towards liver disease complications. Six out of ten respondents were aware hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver, whereby long‐term liver inflammation could lead to fibrosis, that cirrhosis is the final stage of liver scarring and lead to disease complications such as liver failure, cancer, or death. About half recognized viral hepatitis, particularly chronic hepatitis infection could cause liver failure and cancer and were aware of a related statement by WHO (World Health Organization) regarding the risks of untreated viral hepatitis. Only 21.0% comprehended the various stages of liver scarring/fibrosis, and 61.2% reported not knowing that liver fibrosis and cirrhosis are key determinants of liver progression‐related ill health (Table 3).

Table 3.

Respondents' awareness of the complications and risks of liver diseases (n = 500)

| Question (correct response) | n (%) (n = 500) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Based on what you understand about liver diseases, please indicate if you agree or disagree with the following statements: | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | |||

| Liver diseases are only caused by alcohol consumption (disagree) | 98 | 19.6% | 358 | 71.6% | 44 | 8.8% |

| Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver (agree) | 312 | 62.4% | 43 | 8.6% | 145 | 29.0% |

| Cirrhosis can lead to number of complications including organ failure, liver cancer or death (agree) | 319 | 63.8% | 25 | 5.0% | 156 | 31.2% |

| Long‐term injury/inflammation to the liver leads to excessive scar tissue formation called fibrosis (agree) | 323 | 64.6% | 19 | 3.8% | 158 | 31.6% |

| Cirrhosis is the final stage of scarring and it can have a serious effect on the health (agree) | 278 | 55.6% | 22 | 4.4% | 200 | 40.0% |

| Yes | No | Not sure | ||||

| Do you know that viral hepatitis is one of the key causes of liver failure in the world? | 212 | 42.4% | 158 | 31.6% | 130 | 26.0% |

| Do you know that chronic viral hepatitis can cause liver cancer? | 264 | 52.8% | 110 | 22.0% | 126 | 25.2% |

| Are you aware that World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that viral hepatitis if left untreated could lead to complications such as liver failure or liver cancer? | 254 | 50.8% | 138 | 27.6% | 108 | 21.6% |

| Are you aware of the various staging of liver scarring/fibrosis? | 105 | 21.0% | 395 | 79.0% | ||

| Do you know liver fibrosis and cirrhosis is a key determinant of progression for liver disease related death or ill health? | 194 | 38.8% | 306 | 61.2% | ||

About 40% of respondents were aware of the implications of blood transaminase enzyme levels aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT). Less than 10% knew elevated AST/ALT levels were not indicators of lung damage or bacterial infection (Table 4). The specific diagnostic anti‐HCV antibody test and HBsAg test were correctly identified by 28.0% and 23.8%, respectively. However, 40.2% and 46.8% of all respondents wrongly declared that none of the tests indicated in the questionnaire were applicable for diagnosing HBV and HCV, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Respondents' awareness of liver screening and diagnostic tests

| Question (correct response) | n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Others have told us what do elevated liver enzymes such as AST/ALT levels mean to them. Which of the following applies to you? (n = 500) | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | |||

| i. Elevated AST/ALT levels are main indicators of the damage to the lungs (disagree) | 195 | 39.0% | 47 | 9.4% | 258 | 51.6% |

| ii. Elevated AST/ALT levels could indicate infection with viral hepatitis (agree) | 224 | 44.8% | 27 | 5.4% | 249 | 49.8% |

| iii. Elevated AST/ALT levels could indicate risk of liver cancer (agree) | 242 | 48.4% | 20 | 4.0% | 238 | 47.6% |

| iv. Elevated AST/ALT levels are indicators of damage to the liver (agree) | 249 | 49.8% | 18 | 3.6% | 233 | 46.6% |

| v. Elevated AST/ALT levels could indicate bacterial infection (disagree) | 215 | 43.0% | 31 | 6.2% | 254 | 50.8% |

| vi. Elevated AST/ALT levels could indicate risk of having non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) or non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (agree) | 225 | 45.0% | 16 | 3.2% | 259 | 51.8% |

| Which of the following tests are you aware of for diagnosis of Hepatitis B and C? (n = 500) | Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | — | — | ||

| Anti‐HCV antibody test | 133 | 26.6% | 140 | 28.0% | — | — |

| HBsAg test | 119 | 23.8% | 109 | 21.8% | — | — |

| Liver function tests such as liver enzyme levels (AST/ALT levels) | 204 | 40.8% | 170 | 34.0% | — | — |

| Other, please specify (e.g. blood tests, ultrasound & cholesterol tests) | 4 | 0.8% | 2 | 0.4% | — | — |

| None of the above | 201 | 40.2% | 234 | 46.8% | — | — |

| Yes | No | |||||

| Apart from liver biopsy, are you aware of any non‐invasive tools (i.e. that which does not involved puncturing the skin or entering a body cavity) for screening of Advanced Fibrosis Non‐alcoholic Steatohepatitis (AF‐NASH) (n = 46) † | 40 | 87.0% | 6 | 13.0% | — | — |

Number of individuals who answered yes to “Have you heard about AF‐NASH?”

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Preferred information topics and information channels regarding liver diseases by the public

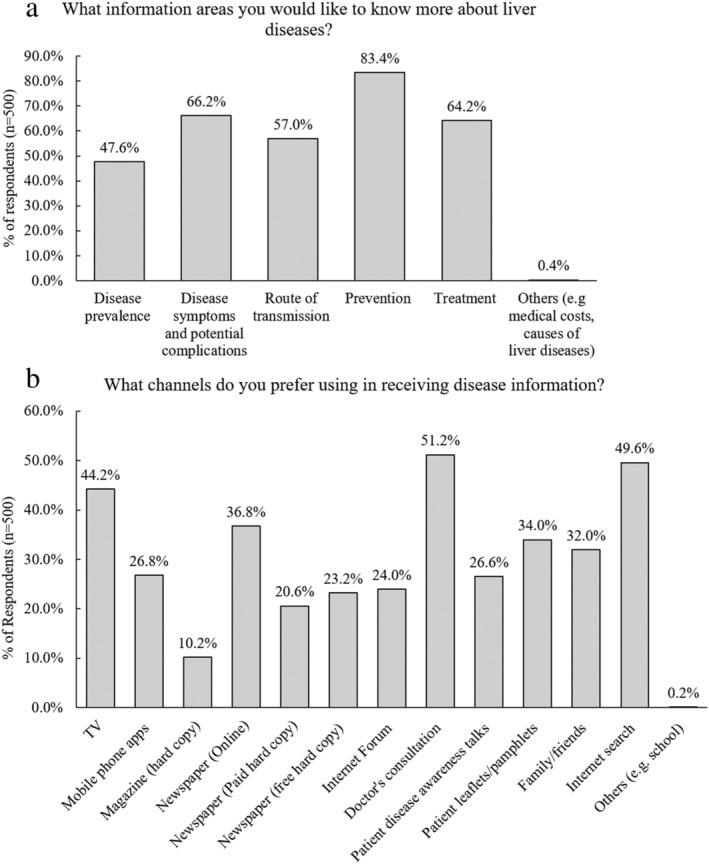

“Prevention” (83.4%), “Disease symptoms and potential complications” (66.2%), and “Treatment” (64.2%) were the top three highly sought information topics regarding liver diseases by the public (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

(a,b) Respondents' preference towards information topics and information channels regarding liver disease‐related information (n = 500).

The top 5 preferred information channels included “Doctor's consultation” (51.2%), “Internet search” (49.6%), “TV” (44.2%), “Newspapers (online)” (36.8%), and “Patient leaflets/pamphlets” (34%) (Fig. 2b).

Overview of existing public education programs in the past 10 years in Singapore

To understand the public health awareness efforts in Singapore, a review of public health educational events was conducted. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36

Based on our search of press releases, a total of 22 public health education forums and campaigns were hosted in the past 10 years (average of two events per year) covering liver‐related health and diseases. These events were commonly held in public healthcare institutions and conducted in English and Mandarin. Fourteen out of 22 public health forums and campaigns were organized by the National Foundation for Digestive Diseases. Table 5 shows the coverage area of various information topics during public health education forum events and campaigns held between 2010 and 2019.

Table 5.

Public forum events/campaign efforts in Singapore between 2010 and 2019 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36

| Public education forums | Year | Location | Language | Topics covered as part of the public education forum campaign | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty liver disease | General liver health | Hepatitis B/C | Liver cancer | Other liver diseases | Prevention and/or risk factors | Screening and diagnosis | ||||

| NFDD Day | 2019 | Public hospital | EN/CH | Y | – | Y | – | – | Y | – |

| 2018 | Convention hall | EN/CH | – | Y | – | – | – | – | Y | |

| 2017 | Public hospital | EN/CH | Y | Y | Y | – | Y | Y | Y | |

| 2016 | Public hospital | EN/CH | – | Y | – | Y | – | Y | Y | |

| 2015 | Public hospital | EN/CH | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | – | |

| 2014 | Public hospital | EN/CH | – | – | – | Y | – | – | – | |

| 2012 | Convention hall | EN/CH | Y | – | – | Y | – | Y | – | |

| 2011 | Convention hall | EN/CH | – | Y | Y | – | – | Y | – | |

| 2010 | Convention hall | EN/CH | Y | – | Y | Y | – | Y | – | |

| World Hepatitis Day (WHD) hosted by NFDD | 2019 | Public hospital | EN/CH | Y | Y | Y | – | – | Y | Y |

| 2018 | Public hospital | EN/CH | Y | – | Y | Y | – | Y | – | |

| 2017 | Public hospital | EN/CH | – | – | Y | – | Y | Y | – | |

| 2016 † | Public hospital | EN/CH | – | – | Y | – | – | Y | Y | |

| 2014 | Public hospital | EN/CH | – | – | Y | – | – | Y | Y | |

| Liver Diseases Awareness Week (LDAW) | 2015 | Public hospital | EN/CH | Y | – | Y | Y | Y | Y | – |

| 2013 | Public hospital | EN/CH | Y | – | Y | Y | – | Y | Y | |

| Other awareness campaigns | ||||||||||

| SKH Public Forum | 2019 | Public hospital | EN | Y | – | – | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Public forum on Liver, Gallbladder and Pancreas Health and Diseases | 2017 | Public hospital | EN | – | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | – |

| Free health screenings for liver cancer | 2014 | Public hospital | EN | – | – | – | Y | – | – | Y |

| Did you know? Information Segment about Hepatitis B transmission | 2013 | Print media information sheet | EN | – | – | Y | – | – | Y | – |

| Public forum on liver health | 2011 | Public atrium | EN | Y | – | Y | – | Y | Y | Y |

| The importance of hepatitis B vaccination | 2010 | Convention hall | EN | – | – | Y | – | – | Y | – |

Hosted in collaboration with public healthcare institutions

CH, Mandarin; EN, English; NFDD, National Foundation of Digestive Diseases; SKH, Sengkang General Hospital; WHD, World Health Organization World Hepatitis Day; Y, was covered during the forum.

Majority (19/22, 86.4%) were centered around the prevention of liver diseases and/or the associated risk factors of various liver diseases including viral hepatitis, FLD, and liver cancer. There was a greater emphasis on hepatitis B and/or C (16/22, 72.7%) while FLD and liver cancer were equally covered. Less than half of topics covered (45.5%) focused on screening and diagnostic tests for liver disease (Table 5).

Discussion

These study findings revealed that Singapore general public's knowledge and awareness about liver‐related health and disease(s) was suboptimal. To begin with, more than half did not know that apart from detoxification function, the liver had other physiological functions including blood clotting and being essential for normal growth and health. Interestingly, only 65.4% attended health screening within the recent 2 years, consistent with previous findings from National Health Survey 2010, 37 despite 91.2% having indicated regular screening as a way to maintain and protect liver health. Reasons for this observation were not explored and would warrant further investigation.

The findings also identified many misperceptions surrounding viral hepatitis, especially HBV, which were previously identified. 38 , 39 The commonest misperceptions included the beliefs that HBV and HCV were transmissible by fecal‐oral route or consuming contaminated food, for example, raw seafood. A study in 2005 reported that 66.4% of HBV patients incorrectly thought that eating contaminated or raw seafood could transmit HBV. 38 These misperceptions were also observed in another local study in 2007 as self‐reported by more than half of the study population. 39 Currently, 15 years later, the same confusions surrounding hepatitis B persists. In addition to these misperceptions, our study revealed that a substantial proportion of respondents were unaware of the vertical and horizontal transmission risks of viral hepatitis, which could hinder efforts to control the spread of HBV and HCV within the community. These findings were not unique to Singapore and were also commonly observed in community studies conducted across Southeast Asia. 40 , 41

Like HBV, HCV is also a blood‐borne disease; however, there is currently no available vaccine to prevent HCV, which remains a common misperception globally. 42 Instead, the recent development of oral DAA treatment regimens for HCV resulted in a successful initial cure rate of up to 99% with minimal side effects, prompting a step closer towards WHO's viral HCV eradication goal. 43 , 44 Although HCV prevalence in Singapore is estimated to be 300 times lower than HBV, 7 the inadequate knowledge and awareness of HCV transmission risks could inadvertently impede measures taken to reduce transmission or undertake treatment within the community, 45 especially among high‐risk groups such as persons who inject drugs. This strongly implies that there is an unmet need to dispel the misperceptions of viral hepatitis to address the knowledge and awareness gaps within the community.

A modeling study of NAFLD disease burden predicted NAFLD prevalence for all ages in Singapore would increase by ~20% in 2030 as compared to 2019. 46 The prevalence of NASH in Singapore was also projected to increase 35% between 2019 and 2030, 46 in tandem with the growing prevalence of NAFLD/NASH risk factors, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. 5 , 12 Our findings showed that many (75%) recognized NAFLD/NASH as liver‐related diseases. This is consistent with findings from an Asian‐based community study, where 71.2% of the study population heard of NAFLD. 12 However, less than half were aware of the associated risk factors for NAFLD/NASH. Patients with NAFLD and NASH are often asymptomatic and hence remain undiagnosed. 10 This poor awareness of the associated risk factors is concerning as the progression of NAFLD to NASH to liver cirrhosis and/or liver failure could be prevented by addressing the risk factors. 10 , 11 Therefore, there is a need for the public to be better educated about the associated risk factors, screening, diagnosis, and management of NAFLD and NASH.

Unfortunately, few were aware of the risks associated with liver diseases. Many were unaware that untreated viral hepatitis could progress towards liver failure and/or liver cancer, or that liver fibrosis is a key determinant of liver disease progression, or of the relevant screening and diagnostic tests to the respective liver diseases. This is an alarming observation especially because many liver diseases tend to remain undiagnosed until the advanced stages of the disease 10 , 47 due to the negative impact of gaps in knowledge and awareness on the effective management of liver disease(s). For example, the gap in the knowledge and awareness of viral hepatitis could hinder the success of viral hepatitis eradication despite existence of effective treatment therapies.

Over the years, public gastroenterology forums and campaigns focusing on liver‐related diseases, particularly prevention and/or associated risk factors of liver diseases, were largely conducted in our public hospitals. These public health education forums and campaigns were centered on the commonest causes of liver cirrhosis and/or HCC, with a greater emphasis towards viral hepatitis than fatty liver disease, seemingly overlapping with the needs of the respondents. Yet, interestingly, our findings revealed that the knowledge and awareness among the respondents pertaining to liver diseases, including, but not limited to, to viral hepatitis, were significantly lacking. The findings highlighted the unmet need for better education efforts to boost awareness and knowledge of liver diseases development and their associated screening/diagnostic tests.

The discrepancy between liver disease(s) information coverage at these public health events and the knowledge/awareness gaps among the study population further suggest that the information outreach to the public might not be sufficiently extensive. A review of the nation's public health education efforts implied a potential misalignment of the channels of outreach. Currently, most of the public health programs are being held as public forums in public hospitals. However, the respondents indicated greater preferences for doctor's consultation, TV, or newspapers (online) than patient disease awareness talks. This finding suggests a gap in effective transmission and reception of liver disease information within the community and points to the need to increase the awareness and knowledge effectively through other media channels. Thus, we will encourage doctors to spend more time to educate the patients during their consultation with them. We will also increase the usage of online media to disseminate educational material to the public.

Importantly, this study revealed that while a significant proportion were aware of the various liver diseases, especially HBV, HCV, and fatty liver disease, the level of knowledge was superficial. There are limitations within the study. Being a cross‐sectional study, no causal associations could be made, and we did not consider the participation incentive as a factor influencing the completion rate of the survey. As all data are self‐reported through a web‐based survey, verification could not be performed to exclude recall bias and respondents without internet access or comfort with online administration could be under‐represented. Furthermore, there remains a considerable proportion (older or less educated) within the population with inadequate command of English, albeit English is one of Singapore's main official languages. 48 As such, it is plausible that the respondents represented a more educated cohort as compared with non‐respondents and may not be applicable to the general population at large.

Individual factors such as profession, health consciousness, health characteristics (e.g. body mass index or history of ever‐diagnosed with liver disease[s]) and family history of liver diseases can potentially influence the awareness level among the study population and should be considered in future studies to confirm the factors associated with the knowledge/awareness gaps to optimize outreach of public health education efforts. Negative attitude and social stigma could also contribute to superficial awareness and knowledge towards liver diseases in the public 49 ; therefore, the attitude towards liver diseases, treatment, and diagnosis should be further investigated.

Another limitation of the study was that the mode in which the respondents received their prior information was not explored, whereby respondents who had attended the public health education forums could be more knowledgeable about liver diseases. Also, the degree of information disseminated at the public health forums could not be identified to evaluate potential gaps in the existing public health education campaigns.

Conclusion

There is an unmet need in Singapore's public health education efforts to raise the awareness of liver diseases among the community. While people were generally aware about hepatitis, the degree of understanding was superficial, with many still having misperceptions of the risk factors and complications of hepatitis. Furthermore, majority were not aware of the complications and association of untreated liver diseases including NAFLD in the development of liver cirrhosis/cancer or liver‐related deaths. Future patient and public health education efforts should focus on dispelling misperceptions and raising awareness about liver‐related diseases including recent increasing prominence of NAFLD/NASH. Notably, such efforts should also be expanded to broaden the accessibility of the information by aligning to the preferred information channels of the public.

Supporting information

Table S1. Respondents' understanding and awareness of general liver health and maintenance (n = 500).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable support from Dr Vince Grillo for his contribution to this research at all stages, along with Dr. Amanda Woo, a medical writer in Kantar Health, who provided medical writing and editorial support.

Section 1: public's overview of overall liver health and liver care

Q1. Based on your understanding of the function of your liver, please indicate whether you “agree,” “disagree,” or “not sure” with the following statements: (select single response per row)

| Liver helps to clean blood by taking harmful substances out of the blood | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Liver stores vitamins and minerals | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Liver stores nutrition/energy we take in from food | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Liver makes bile that helps digest food | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Liver helps with blood clotting, which helps in stopping the bleeding when there is a cut/wound | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Liver produces cholesterol which our body needs for normal growth and health | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

Q2. How can you protect your liver and keep it healthy? Please indicate whether you “agree,” “disagree,” or “not sure” with the following statements: (select single response per row)

| By exercising regularly | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| By eating a balanced diet | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| By drinking alcohol modestly | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| By practicing safe sex | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Follow directions on all medications | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| By getting vaccinated | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Go for regular screening to keep a check the liver | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| By taking liver supplements on my own | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| By sleeping well with good quality of sleep | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

Section 2: public's knowledge and awareness of liver diseases

Q3. Please indicate whether you “agree,” “disagree,” or “not sure” with the following statements regarding hepatitis B or C: (select single response per row)

| i. Hepatitis B … | ii. Hepatitis C … | |||||

| is a bacterial infection | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| is a viral infection | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| can cause chronic inflammation of the liver | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| can cause liver failure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| can be prevented by vaccination | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| is airborne | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| is hereditary | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| increases the risk of the development of liver cirrhosis and cancer | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

Q4. Please indicate whether you “agree,” “disagree,” or “not sure” with the following statements regarding the transmission of hepatitis B or C from one person to another. (select single response per row)

| Hepatitis infection can be transmitted by the following means: | i. Hepatitis B | ii. Hepatitis C | ||||

| a. By touching an infected person | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| b. Through sexual intercourse | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| c. Through blood, e.g. contact with an open wound | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| d. By sharing non‐sterile needles or through needlestick injuries | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| e. Fecal oral route usually through contaminated food, e.g. an infected person forgets to properly wash hands after using toilet and contaminate the food. | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| f. From pregnant mother to her baby at birth | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| g. By sharing of razors, toothbrushes | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| h. By receiving tattoos, body piercing from settings with poor infection control standards | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| h. By eating contaminated or raw seafood, e.g. shellfish | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| i. Having received blood (products) before around 1990s | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| j. Having received long‐term kidney dialysis | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| k. By mosquito bites | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| l. By dining together (e.g. sharing food) with an infected person | Agree | Disagree | Not sure | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

Q5. Have you heard about advanced fibrosis non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (AF‐NASH)? (Select ONE response only)

☐ Yes

☐ No

Q6. Which of the following do you think will increase your risk of having advanced fibrosis non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (AF‐NASH)? (Multiple responses allowed)

☐ Alcohol consumption (or excessive alcohol intake)

☐ Hypertension

☐ Diabetes

☐ Obesity

☐ Lack of exercise

☐ Heart disease

☐ Higher ALT or AST levels

☐ High blood lipid levels

☐ Insulin resistance

☐ Others, please specify: ________________

☐ Don't know

Q7. Based on what you understand about liver diseases, please indicate whether you “agree,” “disagree,” or “not sure” with the following statements. (select single response per row)

| Liver diseases are only caused by alcohol consumption | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Cirrhosis can lead to number of complications including organ failure, liver cancer or death | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Long term injury/inflammation to the liver leads to excessive scar tissue formation called fibrosis | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| Cirrhosis is the final stage of scarring and it can have a serious effect on the health | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

Q8. Do you know that viral hepatitis is one of the key causes of liver failure in the world? (Select ONE response only)

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Not sure

Q9. Do you know that chronic viral hepatitis can cause liver cancer? (Select ONE response only)

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Not sure

Q10. Are you aware that World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that viral hepatitis if left untreated could lead to complications such as liver failure or liver cancer? (Select ONE response only)

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Not sure

Q11. Are you aware of the various staging of liver scarring/fibrosis? (Select ONE response only)

☐ Yes

☐ No

Q12. Do you know that liver fibrosis and cirrhosis is a key determinant of progression for liver disease related death or ill health? (Select ONE response only)

☐ Yes

☐ No

Q13. Others have told us what do elevated liver enzymes such as AST/ALT levels mean to them. Which of the following applies to you? Please indicate whether you “agree,” “disagree,” or “not sure” with the following statements. (select single response per row)

| i. Elevated AST/ALT levels are main indicators of the damage to the lungs | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| ii. Elevated AST/ALT levels could indicate infection with viral hepatitis | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| iii. Elevated AST/ALT levels could indicate risk of liver cancer | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| iv. Elevated AST/ALT levels are indicators of damage to the liver | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| v. Elevated AST/ALT levels could indicate bacterial infection | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

| vi. Elevated AST/ALT levels could indicate risk of having Non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) or Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) | Agree | Disagree | Not sure |

Q14. Which of the following tests are you aware of for diagnosis of Hepatitis B and C? (Multiple responses allowed)

| Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | |

| Anti‐HCV antibody test | □ | □ |

| HBsAg test | □ | □ |

| Liver function tests such as liver enzyme levels (AST/ALT levels) | □ | □ |

| Other, please specify:______________ | □ | □ |

| None of the above (exclusive) | □ | □ |

Q15. Apart from liver biopsy, are you aware of any non‐invasive tools (i.e. that which does not involved puncturing the skin or entering a body cavity) for screening of advanced fibrosis non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (AF‐NASH)? (Select ONE response only)

☐ Yes

☐ No

Section 3: preference towards liver‐related health and disease information and channels

Q16. What channels do you prefer using in receiving disease information? (Multiple responses allowed)

☐ TV

☐ Mobile phone apps

☐ Magazine (hard copy)

☐ Newspaper (Online)

☐ Newspaper (Paid hard copy)

☐ Newspaper (free hard copy)

☐ Internet Forum

☐ Doctor's consultation

☐ Patient disease awareness talks

☐ Patient leaflets/pamphlets

☐ Family/friends

☐ Internet search

☐ Others (please specify): ____________

Q17. What information areas you would like to know more about liver diseases? Please select from the below list. (Multiple responses allowed)

☐ Disease prevalence

☐ Disease symptoms and potential complications

☐ Route of transmission

☐ Prevention

☐ Treatment

☐ Others (please specify):_______________

Tan, C.‐K. , Goh, G. B.‐B. , Youn, J. , Yu, J. C.‐K. , and Singh, S. (2021) Public awareness and knowledge of liver health and diseases in Singapore. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 36: 2292–2302. 10.1111/jgh.15496.

Financial support: This study was funded by Gilead Sciences. Kantar Health received funding from Gilead Sciences for the conduct of the study and development of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Sepanlou SG, Safiri S, Bisignano C et al. The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5: 245–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lin L, Yan L, Liu Y, Qu C, Ni J, Li H. The burden and trends of primary liver cancer caused by specific etiologies from 1990 to 2017 at the global, regional, national, age, and sex level results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Liver Cancer 2020; 9: 563–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 16: 589–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Global Cancer Observatory . Singapore|Source: Globocan 2018 [Internet]. International Agency for Research on Cancer|World Health Organization; 2020. Oct [cited 2020 Dec 3] p. 2. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/702-singapore-fact-sheets.pdf

- 5. Epidemiology & Disease Control Division, Singapore Burden of Disease and Injury Working Group . Singapore Burden of Disease Study 2010 [Internet]. Epidemiology & Disease Control Division|Ministry of Health, Singapore; 2014. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/resources-statistics/reports/singapore-burden-of-disease-study-2010-report_v3.pdf

- 6. Chang PE, Wong GW, Li JW, Lui HF, Chow WC, Tan CK. Epidemiology and clinical evolution of liver cirrhosis in singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2015; 44: 218–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muthiah M, Chong CH, Lim SG. Liver disease in Singapore. Euroasian J Hepato‐Gastroenterol 2018; 8: 66–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ang LW, Cutter J, James L, Goh KT. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection among adults in Singapore: a 12‐year review. Vaccine 2013; 32: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wai CT, Da Costa M, Sutedja D et al. Long‐term results of liver transplant in patients with chronic viral hepatitis‐related liver disease in Singapore. Singapore Med J 2006; 47: 588–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abd El‐Kader SM, El‐Den Ashmawy EMS. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: the diagnosis and management. World J Hepatol 2015; 7: 846–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ngu J, Goh G, Poh Z, Soetikno R. Managing non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Singapore Med J 2016; 57: 368–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goh GBB, Kwan C, Lim SY et al. Perceptions of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease—an Asian community‐based study. Gastroenterol Rep 2016; 4: 131–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Epidemiology & Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health, Singapore . National Health Survey 2010 Singapore [Internet]. Ministry of Health, Singapore; 2011. [cited 2020 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/resources-statistics/reports/nhs2010---low-res.pdf

- 14. Health Promotion Board, Singapore . 1.7 Million Singaporeans already at risk of obesity-related diseases [Internet]. Health Promotion Board. 2014. [cited 2020 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.hpb.gov.sg/article/1.7-million-singaporeans-already-at-risk-of-obesity-related-diseases

- 15. 22nd NFDD Day Public Symposium . The Straits Times. 2010; p. 26.

- 16. 23rd NFDD Public Symposium . The Straits Times. 2011; p. 14.

- 17. 24th NFDD Day Public Symposium . The Straits Times. 2012; p. 2.

- 18. 25th NFDD Day Public Symposium . The Straits Times. 2014; p. 5.

- 19. 26th NFDD Day Public Symposium . The Straits Times. 2015; p. 16.

- 20. 27th NFDD Public Symposium|Take Charge of Your Gut and Liver . The Straits Times. 2016; p. 4.

- 21. 28th NFDD Public Symposium|War on Gastrointestinal Cancers: Prevention is Better than Cure . The Straits Times. 2017; p. 2.

- 22. 29th NFDD Public Symposium , Help, my tummy hurts! 2018.

- 23. 30th NFDD Public Symposium How my weight affects my digestive health. 2019.

- 24. The Straits Times . Free hepatitis C screening and talks. 2016; p. 12.

- 25. World Hepatitis Day 2017 . ABC of Hepatitis|Public Symposium|SingaporeThe Straits Times. 2017; p. 2.

- 26. Acute & Chronic Hepatitis New Cure and Prevention . World Hepatitis Day 2014. TODAY. 2nd Edition. 2014.

- 27. World Hepatitis Day 2018|Singapore. 2018.

- 28. World Hepatitis Day 2019|Liver Strong , Live Strong|Singapore. 2019.

- 29. Liver Disease Awareness Week ‐ Public Symposium . The Straits Times. 2nd Edition. 2013; p. 10.

- 30. 2015 liver disease awareness event . TODAY. 2015; p. 18.

- 31. SKH Public Forum July 20—Sengkang General Hospital [Internet]. Sengkang General Hospital. [cited 2020. Oct 29]. Available from: https://www.skh.com.sg:443/events/patient-care/skh-public-forum-july-20

- 32. National University Hospital . Liver, Gallbladder and Pancreas Health and Diseases [Internet]. Eventfinda. [cited 2020. Oct 29]. Available from: https://www.eventfinda.sg/2017/liver-gallbladder-and-pancreas-health-and-diseases/singapore/ang-mo-kio

- 33. Did you know? The new paper. 2013; p. 21.

- 34. Public forum on liver health . TODAY. 2nd Edition. 2011; p. 11.

- 35. Public Forum: The Importance of Hepatitis B Vaccination. The Straits Times. 2010; p. 5.

- 36. Detect liver cancer early with free health screenings. The Straits Times. 2014; p. 2.

- 37. Wong HZ, Lim WY, Ma SS, Chua LA, Heng DM. Health screening behaviour among Singaporeans. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2015; 44: 326–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wai C‐T, Mak B, Chua W et al. Misperceptions among patients with chronic hepatitis B in Singapore. World J Gastroenterol: WJG 2005; 11: 5002–5005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu W, Mak B, Lim S‐G, Aung MO, Wong M‐L, Wai C‐T. Public misperceptions about transmission of hepatitis B virus in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2007; 36: 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Soe KP, Pan‐ngum W, Nontprasert A et al. Awareness, knowledge, and practice for hepatitis B infection in Southeast Asia: a cross‐sectional study. J Infect Dev Ctries 2019; 13: 656–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wait S, Kell E, Hamid S et al. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C in Southeast and Southern Asia: challenges for governments. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 1: 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ha S, Timmerman K. Awareness and knowledge of hepatitis C among health care providers and the public: a scoping review. Can Commun Dis Rep 2018; 44: 157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization . Draft Global Health Sector Strategies: Viral Hepatitis, 2016–2021: Report by the Secretariat [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Apr [cited 2020 Jan 21] p. 56. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252690

- 44. Trepo C. A brief history of hepatitis milestones. Liver Int Off J Int Assoc Study Liver 2014; 34: 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zickmund SL, Brown KE, Bielefeldt K. A systematic review of provider knowledge of hepatitis C: is it enough for a complex disease? Dig Dis Sci 2007; 52: 2550–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Estes C, Chan HLY, Chien RN et al. Modelling NAFLD disease burden in four Asian regions—2019–2030. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020; 51: 801–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hirnschall G. WHO There's a reason viral hepatitis has been dubbed the “silent killer” [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2015. [cited 2020 Sep 29]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/commentaries/viral-hepatitis/en/

- 48. Department of Statistics Singapore . General Household Survey 2015 [Internet]. Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry, Republic of Singapore; 2016. Mar [cited 2021 Feb 1] p. 469. Report No.: ISBN 978–981–09-8924-8. Available from: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/ghs/ghs2015/ghs2015.pdf

- 49. Burnham B, Wallington S, Jillson IA et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of patients with chronic liver disease. Am J Health Behav 2014; 38: 737–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Respondents' understanding and awareness of general liver health and maintenance (n = 500).