Abstract

Background

Human babesiosis is a zoonotic infection caused by an intraerythrocytic parasite. The highest incidence of babesiosis is in the United States, although cases have been reported in other parts of the world. Due to concerns of transfusion‐transmitted babesiosis, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended year‐round regional testing for Babesia by nucleic acid testing or use of an FDA‐approved device for pathogen reduction. A new molecular test, cobas Babesia (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc.), was evaluated for the detection of the four species that cause human disease, Babesia microti, Babesia duncani, Babesia divergens, and Babesia venatorum.

Study design and methods

Analytical performance was evaluated followed by clinical studies on whole blood samples from US blood donations collected in a special tube containing a chaotropic reagent that lyses the red cells and preserves nucleic acid. Sensitivity and specificity of the test in individual samples (individual donation testing [IDT]) and in pools of six donations were determined.

Results

Based on analytical studies, the claimed limit of detection of cobas Babesia for B. microti is 6.1 infected red blood cells (iRBC)/mL (95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.0, 7.9); B. duncani was 50.2 iRBC/mL (95% CI: 44.2, 58.8); B. divergens was 26.1 (95% CI: 22.3, 31.8); and B. venatorum was 40.0 iRBC/mL (95% CI: 34.1, 48.7). The clinical specificity for IDT was 99.999% (95% CI: 99.996, 100) and 100% (95% CI: 99.987, 100) for pools of six donations.

Conclusion

cobas Babesia enables donor screening for Babesia species with high sensitivity and specificity.

Keywords: Babesia, donor blood screening, nucleic acid testing (NAT)

Abbreviation

- AltNAT1

alternative Babesia NAT test 1

- AltNAT2

alternative Babesia NAT test 2

- ARC

American Red Cross

- B. divergens

Babesia divergens

- B. duncani

Babesia duncani

- B. microti

Babesia microti

- B. venatorum

Babesia venatorum

- CI

confidence interval

- cp/mL

copies per milliliter

- CPM

cobas PCR media

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- IC

internal control

- IDT

Individual donation testing

- IFA

immunofluorescence assay

- IND

Investigational New Drug Application

- iRBC

infected red blood cells

- iRBC/mL

infected red blood cells per milliliter

- LoD

limit of detection

- NAT

nucleic acid testing

- neg‐WB/CPM

Babesia negative whole blood in a ratio of 1:7 whole blood to CPM

- NPA

negative percent agreement

- PCR

polymerase chain reactivity

- PPA

positive percent agreement

- RMS

Roche Molecular Systems, Inc.

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- RWBCT

Roche Whole Blood Collection Tube

- TT

transfusion‐transmitted

- TTB

transfusion‐transmitted babesiosis

- US

United States

1. INTRODUCTION

Babesia is an intraerythrocytic parasite that is transmitted to humans via a tick‐bite, most commonly of the Ixodes species 1 , 2 , 3 and may also be transmitted through the transfusion of blood and blood components, solid organ transplantation, or through vertical transmission from mother to child. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Although most infected individuals are asymptomatic, symptoms of babesiosis range from mild to life‐threatening. Severity may be increased in asplenic individuals, the elderly, the immunocompromised, and infants. 1 , 2 , 6

Babesia microti, Babesia duncani, Babesia venatorum, and Babesia divergens are known to cause human infection in different parts of the world. 2 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 B. microti, B. divergens, and B. venatorum have been reported to cause human babesiosis in Europe 14 and China, 15 and B. microti or B. microti‐like organisms have been reported in Singapore, Australia, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. 14 , 16

B. microti is the most common species in the United States where it is endemic to the Northeast and Upper Midwest of the United States; B. duncani has been reported along the Pacific coast and B. divergens‐like organisms in Kentucky, Missouri, and Washington. 2 , 3 In 2011, babesiosis became a nationally reportable disease in the United States, 2 , 6 and the number of reported cases has since risen steadily. 17 More than 200 cases of transfusion‐transmitted babesiosis (TTB) in the United States have been reported due to B. microti primarily and B. duncani. 6 , 8 , 18 , 19 , 20 To date, there have been no reports of TTB due to B. divergens and B. venatorum. In 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) made recommendations to reduce the risk of TTB, including required screening of blood and blood components by nucleic acid testing (NAT) in the states at highest risk for Babesia or the use of an FDA‐approved pathogen reduction device, which currently is only available for platelets and plasma. 21

The performance of the cobas Babesia nucleic acid test for use on the cobas 6800/8800 Systems (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc.) for screening of whole blood samples is described, including clinical sensitivity and specificity studies conducted on US blood donations by individual donation testing (IDT) and in pools of six individual donations.

2. METHODS

2.1. Assay and systems

The cobas Babesia test for use with the cobas 6800/8800 Systems is a qualitative in vitro nucleic acid screening test for the direct detection of Babesia (B. microti, B. duncani, B. divergens, and B. venatorum) DNA and RNA in whole blood samples from donors of blood and blood components and living organ and tissue donors. 22 A volume of approximately 1.1 mL of whole blood sample is collected into the Roche Whole Blood Collection Tube (RWBCT) (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc.), a designated evacuated blood collection tube containing 7.7 mL of cobas PCR media (CPM), a preanalytic chaotropic reagent that will lyse red blood cells and preserve nucleic acid. 23 Following centrifugation, the RWBCT is the primary tube used for this test on the fully automated cobas 6800/8800 Systems. Whole blood samples may be tested either as individual samples or in pools composed of aliquots of individual samples using the cobas Synergy Software (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc.) and the Hamilton Microlab STAR (Hamilton Company) instrument. Synergy Software collates the results of pooling and testing, assigns the outcomes to individual samples according to a testing algorithm, and formats an output file that can be sent to a laboratory information system.

The cobas Babesia test master mix contains amplification primers and detection probes for Babesia and internal control (IC) nucleic acid. The specific Babesia probes, designed to detect ribosomal RNA and DNA of B. microti, B. duncani, B. venatorum, and B. divergens, and the IC detection probes are each labeled with one of two unique fluorescent dyes, which act as a reporter and a second dye that acts as a quencher. The reporter dye is measured at a defined wavelength, thus permitting simultaneous detection and discrimination of the Babesia target and the IC. The assay is not intended to discriminate between the Babesia species.

2.2. Nonclinical performance evaluation

2.2.1. Analytical sensitivity

The analytical sensitivity of the cobas Babesia test was determined by testing the cultured strains of B. microti, B. duncani, B. divergens, and B. venatorum. Three independent dilution panels for each species were prepared to the appropriate concentration above, below, and at the expected limit of detection (LoD) of cobas Babesia by diluting positive samples in Babesia negative human ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) whole blood. B. microti (ATCC, Strain 30221) and B. duncani (ATCC, Strain PRA 302) infected red blood cells (iRBC) were obtained from fresh hamster blood. B. divergens (Oniris, Strain B128) and B. venatorum (Oniris, Strain C201) were obtained from fresh infected sheep blood. The concentration of iRBC was determined by manual counting using a hemocytometer and Giemsa staining to determine percent parasitemia. The panel members were inoculated into the RWBCTs. For each panel member, two different whole blood input volumes (1.1 and 0.4 mL) were added to the collection tubes. The 1.1 mL reflects the expected direct draw volume with the RWBCTs. A reduced input volume of 0.4 mL was also tested for the maximum effect of high altitudes on blood volume collected by the tube. 24 Panels were tested over multiple reagent lots, days, operators, systems, and replicates per run. Approximately 126 replicates per concentration were tested. The resulting data were calculated by probit analysis (SAS Biometric Tools, SAS Institute, Inc.) to determine the 95% and 50% LoD in iRBC/mL for each species.

Analytical sensitivity was also determined by testing in vitro generated 18S RNA transcripts for each species. Panels were prepared from Babesia RNA transcripts serially diluted in buffer specimen diluent. Each panel of five concentration levels plus a blank was tested over multiple days, runs, and reagent lots for a total of 24 replicates per concentration level. Probit analysis on the combined data was used to estimate the 95% and 50% LoD in copies per milliliter (cp/mL) for each species.

2.2.2. Secondary standards

Babesia secondary standards were prepared as dilutions of either Babesia infected hamster red blood cells (B. microti, B.duncani) or sheep red blood cells (B. divergens, B. venatorum) diluted in CPM using the stock titers provided by the vendors (ATCC or Oniris).

2.2.3. Analytical specificity

Analytical specificity was evaluated by testing cross reactivity with 15 microorganisms at 1.00E+05 to 1.00E+06 copies, genome equivalents, international units, or colony‐forming units per mL including five parasites, five viral isolates, four bacterial strains, and one fungus. The microorganisms were added to Babesia‐negative EDTA‐whole blood specimens, which were prediluted with CPM in a ratio of 1:7 whole blood to CPM, to simulate the primary sample in the RWBCT (neg‐WB/CPM). Each microorganism was tested in three replicates each with and without B. microti secondary standard added to a concentration of approximately 3× LoD of cobas Babesia. The reactive rate was calculated for each of the cross reactants with and without the addition of B. microti.

2.2.4. Inclusivity

The inclusivity of cobas Babesia was determined by testing a total of 10 unique clinical specimens of B. microti neat and diluted in neg‐WB/CPM to approximately 4× LoD. Titers of clinical specimens were determined using the B. microti secondary standard. Due to the unavailability of clinical specimens, secondary standards were used for B. duncani, B. divergens, and B. venatorum diluted in neg‐WB/CPM to approximately 4× LoD.

2.3. Clinical performance evaluation

Seven testing sites participated in studies to determine the clinical sensitivity and specificity of cobas Babesia. These sites included the American Red Cross, Gaithersburg, MD; ImpactLife, Davenport, IA; Versiti Blood Center, Indianapolis, IN; Innovative Blood Resources, St. Paul, MN; Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center, Houston, TX; The Community Blood Center, Appleton, WI; and Central Pennsylvania Alliance Laboratory, York, PA. Testing was performed under an Investigational New Drug application approved by the FDA. Each test site obtained approval from their Institutional Review Board in accordance with the FDA.

2.3.1. Clinical sensitivity

A total of 203 specimens, composed of 131 clinical and 72 contrived specimens, known to be positive for Babesia by NAT were tested neat and in a 1:6 dilution in neg‐WB/CPM to simulate a pool of 6 donations. Neat clinical samples were frozen remnant whole blood specimens positive for B. microti by a laboratory‐developed NAT at Mayo Clinic, mixed with neg‐WB/CPM at a 1:7 ratio.

Contrived samples were prepared by spiking neg‐WB/CPM with secondary standards for each Babesia species at low, medium, and high concentrations of approximately 18×, 36×, and 72× LoD for neat samples.

A total of 1218 Babesia‐positive samples were tested across three sites with cobas Babesia. The clinical sensitivity was calculated as the percentage of known positive samples detected, including the two‐sided Clopper–Pearson exact 95% confidence interval (95% CI). 25

2.3.2. Clinical specificity

Samples from donors who met standard donor eligibility criteria for donation were collected in the RWBCT.

Individual donation study

Whole blood samples were collected from October 2017 through September 2018 from US blood donors using the RWBCT and tested with cobas Babesia. The sites were chosen to include different Babesia endemicity levels. States with high endemicity were those identified in the 2018 FDA Draft Guidance for Industry, “Recommendations for Reducing the Risk of Transfusion‐Transmitted Babesiosis.” 26 States with reported cases of babesiosis that were not identified in the draft guidance were considered to be of low endemicity, and states that had no reports of babesiosis were considered to be nonendemic.

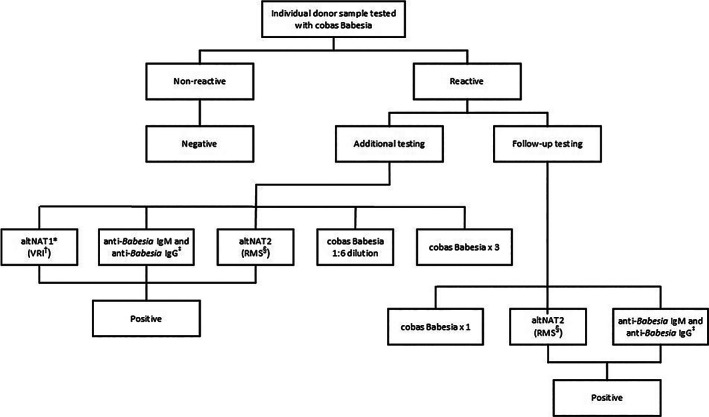

Additional testing was conducted on index donations reactive on cobas Babesia (Figure 1), including repeat testing in triplicate with cobas Babesia; simulated 1:6 pool by testing a dilution of the donor sample in neg‐WB/CPM; two alternative Babesia NAT (AltNAT1, AltNAT2); and anti‐Babesia IgM and anti‐Babesia IgG immunofluorescence assay specific for B. microti to confirm the presence of Babesia infection. AltNAT1 27 (Vitalant Research Institute) detected only B. microti and was less sensitive than the Roche in‐house validated AltNAT2, which used primers and probes different from cobas Babesia for the detection of the four Babesia species.

FIGURE 1.

Index testing algorithm for individual donation samples. *altNAT = alternative NAT, †Vitalant Research Institute, ‡Quest Diagnostics, §RMS = Roche Molecular Systems, Inc

All donors whose samples were reactive on cobas Babesia were eligible for the follow‐up study. Enrolled donors were followed until seroconversion for up to 8 weeks and up to four follow‐up visits. Each follow‐up collection was tested with cobas Babesia, AltNAT2, anti‐Babesia IgM, and anti‐Babesia IgG.

A reactive result on cobas Babesia was considered a true positive if the index donation or follow‐up sample was reactive by either AltNAT, or positive for anti‐Babesia IgM or anti‐Babesia IgG. Status negative or uninfected donations were defined as total donations with valid results on cobas Babesia minus true‐positive donations. The specificity of cobas Babesia was calculated as the frequency of cobas Babesia nonreactive results among status‐negative blood donations for donations overall and separately for donations collected in each of the three Babesia endemicity categories: high, low, and nonendemic.

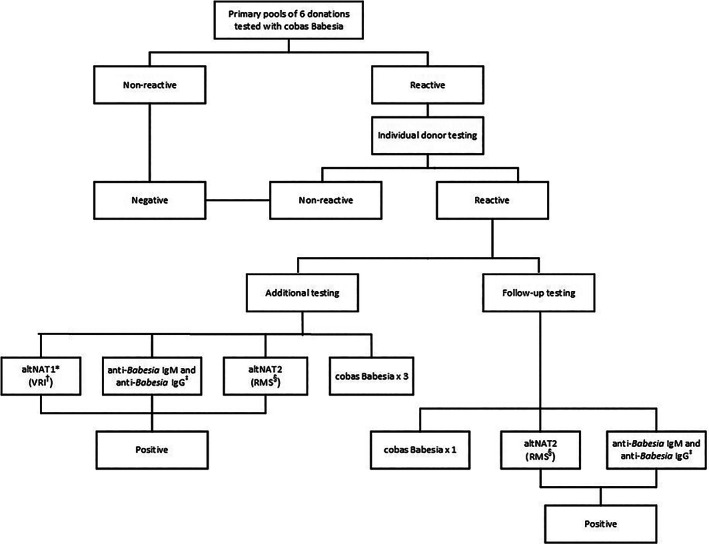

Pooled donations

Donor samples collected between August and November 2019 were tested in pools composed of five or six individual donations at four testing centers. Pooling resolution testing was performed on cobas Babesia reactive pools to determine which donation in the pool was reactive. Each individual reactive sample was then tested as was described earlier for the individual donation study (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Index testing algorithm for pools of six donations. *altNAT = alternative NAT, †Vitalant Research Institute, ‡Quest Diagnostics. §RMS = Roche Molecular Systems, Inc

All donors whose samples were reactive on cobas Babesia were eligible for the follow‐up study. Enrolled donors were followed until seroconversion for up to a 4 weeks and up to two follow‐up visits after the date of their index donation. Each follow‐up collection was tested as described earlier.

A reactive result on cobas Babesia was considered a true positive if the index donation or follow‐up sample was reactive by either AltNAT or positive for anti‐Babesia IgM or anti‐Babesia IgG.

The donor‐level specificity of the cobas Babesia test was calculated as the percentage of Babesia status‐negative samples that were nonreactive on the cobas Babesia test for donations overall and separately for donations collected in each of the three Babesia endemicity categories. The pool‐level specificity of the cobas Babesia test was calculated as the frequency of cobas Babesia nonreactive pools of six results among pools containing wholly status‐negative donations.

The pooled donation study also included the retesting, in pools of 6, samples that were identified as reactive by individual donation screening with cobas Babesia performed during the time of the pooled donation study.

2.3.3. Pooling deconstruction

A pooling deconstruction study was performed to demonstrate that the sample pooling and functionality of the cobas Synergy Software, together with the Hamilton Microlab STAR for pooling, is capable of identifying Babesia NAT reactive specimens in pools of six samples comprised of Babesia‐positive and Babesia‐negative specimens.

Nine panels of 96 coded panel members consisting of 813 Babesia negative samples and 51 Babesia positive samples, representing all four Babesia species, were pooled into 16 primary pools of five or six samples and tested with cobas Babesia. The concentrations used for the Babesia‐positive panel members were such that after a 1:6 dilution, concentrations were approximately 5× LoD. Reactive pools were deconstructed to identify the individual positive samples.

Statistics of overall percent agreement, positive percent agreement (PPA), and negative percent agreement (NPA) between the sample types and deconstruction results were calculated with one‐sided 95% lower confidence bounds using the SAS FREQ6 procedure (SAS Institute, Inc.).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Analytical sensitivity

For each Babesia species, probit analysis on the data combined across dilution series and reagent lots was used to estimate the 95% and 50% LoD, along with the lower and upper limit of 95% confidence range for Babesia iRBC/mL in human whole blood (Table 1) and with Babesia transcripts in cp/mL (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Limit of detection of Babesia infected red blood cells (iRBC) in human whole blood

| Babesia species | 1.1 ml whole blood input volume | 0.4 ml whole blood input volume | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% reactive rate (iRBC/mL) | 95% confidence range | 50% reactive rate (iRBC/mL) | 95% confidence range | 95% reactive rate (iRBC/mL) | 95% confidence range | 50% reactive rate (iRBC/mL) | 95% confidence range | |

| Babesia microti | 2.8 | 2.3–3.6 | 0.5 | 0.5–0.6 | 6.1 | 5.0–7.9 | 1.2 | 1.1–1.4 |

| Babesia duncani | 52.0 | 45.2–61.7 | 19.7 | 18.1–21.4 | 50.2 | 44.2–58.8 | 21.6 | 20.0–23.4 |

| Babesia divergens | 16.3 | 14.3–19.4 | 6.6 | 6.0–7.1 | 26.1 | 22.3–31.8 | 8.2 | 7.5–9.0 |

| Babesia venatorum | 28.3 | 24.4–34.0 | 9.6 | 8.8–10.5 | 40.0 | 34.1–48.7 | 13.0 | 11.8–14.2 |

TABLE 2.

Limit of detection with Babesia RNA transcripts

| Babesia species | LOD by Probit analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% reactive rate (cp/mL) | 95% confidence range | 50% reactive rate (cp/mL) | 95% confidence range | |

| Babesia microti | 38.0 | 28.9–55.7 | 7.2 | 6.1–8.5 |

| Babesia duncani | 54.7 | 41.8–80.5 | 10.1 | 8.1–12.0 |

| Babesia divergens | 79.7 | 58.0–124.4 | 14.2 | 12.1–16.7 |

| Babesia venatorum | 57.8 | 45.2–81.6 | 12.5 | 10.5–14.6 |

3.2. Analytical specificity

All of the microorganism samples with approximately 3× LoD Babesia tested reactive and all microorganisms without added Babesia tested nonreactive for Babesia, indicating that the specificity of cobas Babesia was not affected by the tested microorganisms (Table S1).

3.3. Inclusivity

All samples of B. microti were 100% detected neat and at 4× LoD, and all samples of B. duncani, B. venatorum, and B. divergens cultures were 100% detected at 4× LoD (data not shown).

3.4. Clinical performance validation/clinical performance evaluation

3.4.1. Clinical sensitivity

Table S2 shows the clinical sensitivity of the 203 known Babesia‐positive samples. The overall clinical sensitivity of the clinical and contrived samples across three test sites was 100% (95% CI: 99.4, 100.0) when tested neat (Table S3) and when tested diluted 1:6 (Table S4).

3.4.2. Clinical specificity

Individual donation studies

Of the 168,981 donations tested by IDT, 143,939 were collected in states with high Babesia endemicity, 14,217 in states with low Babesia endemicity, and 10,825 in a state where Babesia is nonendemic.

Of 168,981 donations, 11 had reactive cobas Babesia results (Table 3). Nine donations were confirmed as true‐positives by AltNAT on their index donation; all were reactive on their simulated 1:6 pool results and when retested neat for all three replicates. Five of these were positive for anti‐Babesia antibody. Two donations were classified as false reactive cobas Babesia results based on additional testing of their index donation or follow‐up testing. All nine confirmed positive donations were determined to be B. microti on the basis of AltNAT1 or anti‐Babesia IgG reactivity. Of the positives, 8 were from high endemic states (Minnesota and Wisconsin) and 1 was from a nonendemic state (Iowa).

TABLE 3.

Testing reactivity patterns and donation status summary—individual donation testing

| Reactivity category a | Index donation testing | Follow‐up study donation testing | Donation status d | Number of donations (total N = 168,981) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cobas Babesia | Alt. NAT 1 | Alt. NAT 2 | Anti‐Babesia IgM | Anti‐Babesia IgG | Repeat 1:6 pool/R1/R2/R3 cobas Babesia b | cobas Babesia c | Alt. NAT 2 | IgM or IgG positive? | |||

| 1 | Reactive | − | + | − | + | (+)/+/+/+ | ND | ND | ND | Positive | 1 |

| Reactive | + | + | − | + | (+)/+/+/+ | +/+/+/+ | +/+/+/+ | +/+/+/+ | Positive | 1 | |

| Reactive | + | + | ND | ND | (+)/+/+/+ | +/+/ND/ND | +/+/ND/ND | +/+/ND/ND | Positive | 1 | |

| Reactive | + | + | − | + | (+)/+/+/+ | +/−/−/− | +/+/−/ND | +/+/+/+ | Positive | 1 | |

| Reactive | + | + | − | − | (+)/+/+/+ | ND | ND | ND | Positive | 3 | |

| Reactive | + | + | − | + | (+)/+/+/+ | ND | ND | ND | Positive | 1 | |

| Reactive | + | + | + | + | (+)/+/+/+ | ND | ND | ND | Positive | 1 | |

| 3 | Reactive | − | − | − | − | (−)/−/−/− | −/−/−/ND | −/−/−/ND | −/−/−/ND | Negative | 1 |

| Reactive | − | − | − | − | (−)/−/−/− | ND | ND | ND | Negative | 1 | |

| 4 | Nonreactive | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Negative | 168,970 |

Note: Only evaluable donations are included in this summary table.

Abbreviations: ‘−’, negative/non‐reactive; ‘+’, positive/reactive; Alt. NAT, alternative NAT; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; Index donation, donation reactive with cobas Babesia for use with the cobas 6800/8800 Systems; N/A, not applicable; ND, not done; R1\R2\R3, repeat test 1, repeat test 2, repeat test 3.

Reactivity categories were defined as follows: Category 1—cobas Babesia reactive index donations with positive alternative NAT results (AltNAT1 or AltNAT2). Category 2—cobas Babesia reactive index donation with non‐reactive with AltNAT1 or AltNAT2 and positive anti‐Babesia IgM or anti‐Babesia IgG results (n = 0 donations). Category 3—cobas Babesia reactive index donation with no further reactivity on additional index testing or follow‐up testing (i.e., false positive reactive cobas Babesia results). Category 4—donations with non‐reactive cobas Babesia results.

Additional cobas Babesia results from simulated pooling (1:6 dilution), if performed, are displayed in parentheses. cobas Babesia results from additional testing of neat replicates, if performed, are displayed with no parentheses in test order separated by a “/”.

Follow‐up study results from up to 4 follow‐up visits are displayed separated by a “/”.

Donation status was assigned based on the testing reactivity pattern observed on the index donation (initial and additional index testing) and/or based on follow‐up study results.

The clinical specificity of cobas Babesia across all endemicity categories for donations tested individually is 99.999% (95% CI: 99.996, 100.000). The specificity for each endemicity category is shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Clinical specificity of cobas Babesia—individual donation study

| cobas Babesia result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endemicity | Total number status‐negative donations | Reactive | Non‐reactive | Estimate in percent (95% exact CI) |

| Overall | 168,972 | 2 | 168,970 | 99.999 (99.996, 100.000) |

| Nonendemic | 10,824 | 0 | 10,824 | 100.000 (99.996,100,000) |

| Low endemic | 14,217 | 0 | 14,217 | 100.000 (99.974,100,000) |

| High endemic | 143,931 | 2 | 143,929 | 99.999 (99.995,100.000) |

Note: Only evaluable donations are included in this summary table. CI = two‐sided exact binomial confidence interval.

Pooled donations

The majority of donations (15,294 of 27,613) tested with cobas Babesia in pools were from high Babesia endemicity states, 5834 were from low endemicity states, and 6485 were from non‐endemic states.

There were 27,613 donations tested in 4610 pools, including six reactive donations from individual donor screening that were reflexed to the pooled donation study. There were a total of seven reactive pools; each resolved to an individual donation with a reactive cobas Babesia result. All of the reactive individual donations were confirmed positive by AltNAT1 and/or AltNAT2, and all were reactive x 3 by cobas Babesia (Table 5). The seven reactive pools included the six pools containing the donations that had been originally identified by IDT screening; these pools resolved to the IDT‐reactive donation. All seven positives were from high endemic states (Minnesota and Wisconsin).

TABLE 5.

Testing reactivity patterns and donation status summary—pooled donations

| Reactivity category a | Index donation testing | Follow‐up study donation testing | Donation status d | Number of donations (N = 27,729) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cobas Babesia result | Alternative NAT 1 | Alternative NAT 2 | Anti‐Babesia IgM +? | Anti‐Babesia IgG +? | R1/R2/R3 cobas Babesia testing results reactive? b | Follow‐up study cobas Babesia results reactive? c | Follow‐up study alternative NAT 2 results reactive? c | Follow‐up study IgM and IgG positive? c | |||

| 1 | Reactive | + | ND | + | + | +/+/+ | ND | ND | ND | Positive | 1 |

| 1 | Reactive | + | + | + | + | +/+/+ | +/+/+/+ | +/+/+/+ | +/+/+/+ | Positive | 1 |

| 1 | Reactive | + | + | − | − | +/+/+ | ND | ND | ND | Positive | 1 |

| 1 | Reactive | + | + | + | − | +/+/+ | ND | ND | ND | Positive | 1 |

| 1 | Reactive | + | + | + | + | +/+/+ | ND | ND | ND | Positive | 3 |

| 4 | Non‐Reactive | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Negative | 27,722 |

Note: Only evaluable donations are included in this summary table.

Abbreviations: −, negative/non‐reactive; +, positive/reactive;?, inconclusive; cobas Babesia, cobas Babesia for use with the cobas 6800/8800 Systems; E, equivocal; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IgG, immunoglobulin G; index donation, donation reactive on cobas Babesia for use with the cobas 6800/8800 Systems; N/A, not applicable; NAT = nucleic acid test; ND, not done; I, invalid.

Reactivity categories were defined as follows: Category 1—cobas Babesia‐reactive index donations with positive alternative NAT 1 and/or alternative NAT 2 results. Category 2—cobas Babesia‐reactive index donations with non‐reactive alternative NAT (1 & 2) and positive anti‐Babesia IgM or anti‐Babesia IgG results. Category 3—cobas Babesia‐reactive index donations with no further reactivity on additional index testing or follow‐up testing (i.e., false‐reactive cobas Babesia results). Category 4—Donations with non‐reactive cobas Babesia results.

cobas Babesia results from additional testing of neat replicates, if performed, are displayed with no parentheses in test order separated by a “/”.

Follow‐up study results from up to 4 follow‐up visits are displayed separated by a ‘/’.

Donation Status was assigned based on the testing reactivity pattern observed on the index donation (initial and additional index testing) and/or based on follow‐up study results.

The clinical specificity of cobas Babesia across all endemicity categories for donations tested in pools of six donations is shown in Table 6. There were no false reactive pools (pool specificity 100%, 95% CI: 99.920, 100).

TABLE 6.

Clinical specificity of cobas Babesia—pools of 6 (donation level)

| Endemicity | Total number of status‐negative donations | cobas Babesia reactive | cobas Babesia nonreactive | Estimate in percent (95% exact CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonendemic | 6485 | 0 | 6485 | 100.000 (99.943, 100.000) |

| Low endemic | 5834 | 0 | 5834 | 100.000 (99.937, 100.000) |

| High endemic | 15,287 | 0 | 15,287 | 100.000 (99.976, 100.000) |

| Overall | 27,606 | 0 | 27,606 | 100.000 (99.987, 100.000) |

Note: Only evaluable donations are included in this summary table. CI, two‐sided exact binomial confidence interval.

Pooling deconstruction

A summary of the positive, negative, and overall percent agreement of the cobas Babesia test with sample type for the deconstruction of the nine panels is shown in Table S5. All 864 samples initially tested in pools of six were correctly identified with an overall agreement of 100% (95% CI: 99.7, 100), 100% PPA (95% CI: 94.3, 100), and 100% NPA (95% CI: 99.6, 100).

4. DISCUSSION

The performance of the cobas Babesia test in both clinical and nonclinical studies demonstrates its high sensitivity and specificity both by IDT and in pools of six donations. In addition, cobas Babesia can detect all four species of Babesia that cause human babesiosis, providing utility not only in the United States but also in other regions where there has been an increase in the detection of Babesia.

The analytical sensitivity of B. microti at 95% and 50% LoD was 2.8 iRBC/mL (95% CI: 2.3, 3.6) and 0.5 iRBC/mL (95% CI: 0.5, 0.6), respectively, with a sample volume of 1.1 mL in 7.7 mL CPM, which simulates the expected blood sample volume collected in the RWBCT under routine conditions. Taking a conservative approach to account for differences in high altitude that could impact sample collection, 24 a sample volume of 0.4 mL was used for the analytical sensitivity claim for the assay. The detection of known positives further supports the sensitivity of cobas Babesia for the detection of all four species of Babesia by IDT and in pools of six.

The cobas Babesia assay targets ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as well as DNA. Using infected human clinical samples, Hanron et al. found that B. microti rRNA was greater than 1000 times more abundant than coding genes. 28 Therefore, each parasite in a donor sample would be expected to release more than 1000 copies of target into the lysate in the RWBCT. Given the high expected target copy number in the lysate from even a single parasite, it is not surprising that in our studies all of the confirmed positive samples detected by individual donation screening were also detectable when diluted 1:6 in a pool or simulated pool. The clinical specificity was excellent for both IDT at 99.999% (95% CI: 99.996, 100.000) and in pools of six at 100% (95% CI: 99.987, 100.000).

In May 2019, the US FDA recommended that blood centers implement year‐round regional testing by NAT for blood donations collected in Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Washington, DC. 21 Pathogen reduction using an FDA‐approved device is also allowable; however, it is not currently available for red cells. The cobas Babesia test was licensed by the US FDA in August 2019 by IDT and for pooling in May 2020; the test is currently in use to screen donations from these endemic regions.

Of the nine confirmed‐positive donations detected by IDT, eight were collected in Wisconsin and Minnesota, states considered to be high endemic for Babesia. This confirms the presence of Babesia in donations in these states which were included in the requirement for testing in the final FDA guidance, 21 although the prevalence is lower than in the Northeast United States. 29 The remaining confirmed‐positive donation was collected in Iowa, a Babesia nonendemic state. The detection of Babesia in a nonendemic state may not be surprising, especially in donors who travel to endemic states. The donor from Iowa was reported to have visited Martha's Vineyard in Massachusetts prior to their donation. A recent analysis by Menis et al. reported an increase of babesiosis in US nonendemic states such as Florida, California, Texas, North Carolina, and Illinois, reinforcing the importance of nationwide monitoring of babesiosis to understand local and travel‐associated infections. 30 Four of the confirmed positive donations were collected in November, December, January, and March (data not shown). Most cases of babesiosis in the United States occur from late spring to early autumn in endemic areas, 1 although TTB may occur year‐round in nonendemic areas, 3 supporting the FDA recommendation for year‐round testing.

The cobas Babesia test is the first test for the cobas 6800/8800 Systems that utilizes whole blood as the sample type. The ability to use whole blood for NAT is remarkable as heme is a natural inhibitor of polymerase chain reactivity (PCR) by reducing or blocking amplification. 31 The RWBCT with the addition of a proprietary chaotropic reagent that lyses red blood cells and preserves DNA and RNA has made it possible to minimize the inhibitory effects of heme and provides new opportunities to apply PCR‐based technology for the detection of other transfusion‐transmitted (TT)‐intraerythrocytic pathogens by NAT, such as malaria. The lysate material could be used for multiple tests without having to draw “another tube” from the donor. Another advantage of the RWBCT is that once the sample is received in the laboratory and following centrifugation, no additional steps are required for pipetting or transferring the sample to another test tube prior to testing by IDT; the Whole Blood Collection Tube can be placed directly on the cobas 6800/8800 Systems. This reduction in touchpoints in the preanalytic stage streamlines workflow, reduces opportunities for contamination, and minimizes occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens. Once the sample is placed on the cobas 6800/8800 Systems, universal sample preparation steps, including nucleic acid extraction and purification, followed by PCR amplification and detection, require minimal operator interaction.

In summary, the performance of the cobas Babesia test for use on the automated cobas 6800/8800 Systems demonstrates excellent sensitivity and specificity for the detection of all four species of Babesia known to cause human infection.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The studies described in this manuscript were sponsored by Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. JS, LLP, and SAG are employees of Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. PA is an employee of Roche Diagnostics International Ltd. SLS, YE, JC, JG, MJ, SNR, and TS were principal investigators for the studies.

Supporting information

Table S1. Performance of cobas Babesia ‐ potentially cross‐reactive microorganisms.

Table S2. Clinical sensitivity of known Babesia positive samples.

Table S3. Sensitivity of cobas Babesia for Neat Known Babesia‐Positive Samples.

Table S4. Sensitivity of cobas Babesia for Diluted Known Babesia‐Positive Samples.

Table S5. Summaries of positive, negative and overall percent agreement of deconstruction results with respect to known sample type (Primary pools of 6 samples)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr Michael Busch and Dr Sonia Bakkour at Vitalant Research Institute, San Francisco for performing the alternate NAT testing for Babesia. We would also like to thank those responsible for collection, testing, statistical analysis, and study management at the ARC Scientific Support Office, ImpactLife, Versiti Blood Center Indiana, Versiti Blood Center Wisconsin, Innovative Blood Resources, Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center, The Community Blood Center, Central Pennsylvania Alliance Laboratory, Roche Diagnostics International Ltd., Rotkreuz; and Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton.

Appendix A. cobas Babesia IND study group members

American Red Cross—Susan L. Stramer, Kacie E. Grimm

ImpactLife—Yasuko Erickson

Versiti Blood Center Indiana—Julie Cruz

Versiti Blood Center Wisconsin—Jerome L. Gottschall

Innovative Blood Resources—Jed Gorlin, Mark Janzen

Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center—Susan N. Rossmann

The Community Blood Center—Todd Straus

Central Pennsylvania Alliance Laboratory—Jennifer Thebo

Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. and Roche Diagnostics International, Ltd.—Patrick Albrecht, Ann Butcher, Marizen Cunanan, John R. Duncan, Susan A. Galel, Matthew Lin, Enrique Marino, Christopher Noutsios, Lisa Lee Pate, Keerti Sharma, June Sunga

Stanley J, Stramer SL, Erickson Y, Cruz J, Gorlin J, Janzen M, et al. Detection of Babesia RNA and DNA in whole blood samples from US blood donations. Transfusion. 2021;61:2969–2980. 10.1111/trf.16617

List of cobas Babesia IND study group members is available in the Appendix.

Funding information Roche Molecular Systems, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Krause PJ. Human babesiosis. Int J Parasitol. 2019;49:165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vannier E, Krause PJ. Human babesiosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vannier EG, Diuk‐Wasser MA, Ben Mamoun C, Krause PJ. Babesiosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:357–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iyer S, Goodman K. Congenital Babesiosis from maternal exposure: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:e39–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saetre K, Godhwani N, Maria M, Patel D, Wang G, Li KI, et al. Congenital Babesiosis after maternal infection with Borrelia burgdorferi and Babesia microti . J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018;7:e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herwaldt BL, Linden JV, Bosserman E, Young C, Olkowska D, Wilson M. Transfusion‐associated babesiosis in the United States: a description of cases. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:509–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fang DC, McCullough J. Transfusion‐transmitted Babesia microti . Transfus Med Rev. 2016;30:132–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Linden JV, Prusinski MA, Crowder LA, Tonnetti L, Stramer SL, Kessler DA, et al. Transfusion‐transmitted and community‐acquired babesiosis in New York, 2004 to 2015. Transfusion. 2018;58:660–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mascarenhas TR, Silibovsky RS, Singh P, Belden KA. Tick‐borne illness after transplantation: case and review. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018;20:e12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martinot M, Zadeh MM, Hansmann Y, Grawey I, Christmann D, Aguillon S, et al. Babesiosis in immunocompetent patients, Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:114–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gabrielli S, Totino V, Macchioni F, Zuñiga F, Rojas P, Lara Y, et al. Human Babesiosis, Bolivia, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1445–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hildebrandt A, Gray JS, Hunfeld KP. Human babesiosis in Europe: what clinicians need to know. Infection. 2013;41:1057–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou X, Xia S, Huang JL, Tambo E, Zhuge HX, Zhou XN. Human babesiosis, an emerging tick‐borne disease in the People's Republic of China. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lobo CA, Singh M, Rodriguez M. Human babesiosis: recent advances and future challenges. Curr Opin Hematol. 2020;27:399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen Z, Li H, Gao X, Bian A, Yan H, Kong D, et al. Human Babesiosis in China: a systematic review. Parasitol Res. 2019;118:1103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lim PL, Chavatte JM, Vasoo S, Yang J. Imported human Babesiosis, Singapore, 2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:826–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Surveillance for babesiosis — United States, 2017 Annual Summary. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tonnetti L, Townsend RL, Dodd RY, Stramer SL. Characteristics of transfusion‐transmitted Babesia microti, American red Cross 2010‐2017. Transfusion. 2019;59:2908–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bloch EM, Herwaldt BL, Leiby DA, Shaieb A, Herron RM, Chervenak M, et al. The third described case of transfusion‐transmitted Babesia duncani. Transfusion. 2012;52:1517–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burgess MJ, Rosenbaum ER, Pritt BS, Haselow DT, Ferren KM, Alzghoul BN, et al. Possible transfusion‐transmitted Babesia divergens‐like/MO‐1 infection in an Arkansas patient. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1622–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: recommendations for reducing the risk of transfusion‐transmitted Babesiosis. Silver Spring, MD: CBER: Office of Communication OCOD; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. cobas Babesia nucleic acid test for use on the cobas 6800/8800 Systems; 08842604001–3EN.

- 23. Roche Whole Blood Collection Tube; 08848424001‐02EN.

- 24. Bush V, Cohen R. The evolution of evacuated blood collection tubes. Lab Med. 2003;34 304–10. 10.1309/JCQE33NBYGE0FFQR [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clopper C, Pearson E. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26(4):404–13. 10.1093/biomet/26.4.404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. US Food and Drug Administration. Draft guidance for industry: recommendations for reducing the risk of transfusion‐transmitted Babesiosis. Silver Spring, MD: CBER: Office of Communication OCOD; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bloch EM, Lee TH, Krause PJ, Telford SR 3rd, Montalvo L, Chafets D, Usmani‐Brown, S, Lepore TJ, Busch MP. Development of a real‐time polymerase chain reaction assay for sensitive detection and quantitation of Babesia microti infection. Transfusion. 2013;53:2299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hanron AE, Billman ZP, Seilie AM, Chang M, Murphy SC. Detection of Babesia microti parasites by highly sensitive 18S rRNA reverse transcription PCR. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;87:226–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tonnetti L, Townsend RL, Deisting BM, Haynes JM, Dodd RY, Stramer SL. The impact of Babesia microti blood donation screening. Transfusion. 2019;59:593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Menis M, Whitaker BI, Wernecke M, Jiao Y, Eder A, Kumar S, et al. Babesiosis occurrence among United States Medicare Beneficiaries, ages 65 and older, during 2006–2017: overall and by state and county of residence. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofaa608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Al‐Soud WA, Rådström P. Purification and characterization of PCR‐inhibitory components in blood cells. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:485–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Performance of cobas Babesia ‐ potentially cross‐reactive microorganisms.

Table S2. Clinical sensitivity of known Babesia positive samples.

Table S3. Sensitivity of cobas Babesia for Neat Known Babesia‐Positive Samples.

Table S4. Sensitivity of cobas Babesia for Diluted Known Babesia‐Positive Samples.

Table S5. Summaries of positive, negative and overall percent agreement of deconstruction results with respect to known sample type (Primary pools of 6 samples)