Abstract

This study examined if people with chronic stroke (PwCS) could adapt following non-paretic overground gait-slips and whether such prior exposure to non-paretic slips could improve reactive responses on novel paretic slip. Forty-nine PwCS were randomly assigned to either adaptation group, which received eight unexpected, overground, nonparetic-side gait-slips followed by two paretic-side slips or a control group, which received two paretic-side slips. Slip outcome, recovery strategies, center of mass (CoM) state stability, post-slip stride length and slipping kinematics were analyzed. The adaptation group demonstrated fall-reduction from first to eighth non-paretic slips, along with improved stability, stride length and slipping kinematics (p < 0.05). Within the adaptation group, on comparing novel slips, paretic-side demonstrated comparable pre-slip stability (p > 0.05); however, lower post-slip stability, increased slip velocity and falls was noted (p < 0.05). There was no difference in any variables between the novel paretic slips of adaptation and control group (p > 0.01). However, there was a rapid improvement on the 2nd slip such that adaptation group demonstrated improved performance from the first to second paretic slip compared to that in the control group (p < 0.01). PwCS demonstrated immediate proactive and reactive adaptation with overground, nonparetic-side gait-slips. However, PwCS did not demonstrate any inter-limb performance gain on the paretic-side after prior nonparetic-side adaptation when exposed to a novel paretic-side slip; but they did show significant positive gains with single slip priming on the paretic-side compared to controls without prior adaptation.

Clinical registry number: NCT03205527.

Keywords: Stroke, Adaptation, Fall-risk, Slip-perturbation

Introduction

Stroke is associated with a varying spectrum of sensorimotor impairments, cognitive deficits, balance and postural dysfunctions resulting in significant gait impairments (Tatemichi et al. 1994; Niam et al. 1999; Bansil et al. 2012; Balaban and Tok 2014). About more than 80% of people with stroke demonstrate gait dysfunctions (Duncan et al. 2005; Balaban and Tok 2014). These gait deficits coupled with sensorimotor impairments eventually increase the risk of falling during walking (Hyndman et al. 2002; Batchelor et al. 2012). Spontaneous post-stroke recovery through neural reorganization (Teasell et al. 2005) and therapy induced neuroplastic changes (Arya et al. 2011) have resulted in improvements in gait and balance functions among 75–85% of people with stroke within the first 6 month post-stroke (Patel et al. 2000). Moreover, people with stroke also exhibit a preserved ability to learn new motor skills (Platz et al. 1994; Baguma et al. 2020).

With an aim to restore locomotor capacity and improve walking speed, locomotor training using split-belt treadmill, overground or motorized treadmill-based paradigms have shown improvement in gait symmetry (step length, double support time), gait speed, efficiency and coordination in post-stroke individuals with gait deficits (Reisman et al. 2005, 2007, 2009; Moore et al. 2010; Boyne et al. 2020). While locomotor training improves gait function mainly during unperturbed conditions, to reduce fall-risk associated with perturbations encountered during activities of daily living (walking and standing), there is a need to improve postural stability during such conditions. Recently, task-specific perturbation-based training paradigms have shown promising adaptive changes in postural stability and fall-resisting skills in people with stroke (Mansfield et al. 2017; Handelzalts et al. 2019; Schinkel-Ivy et al. 2019; Dusane and Bhatt 2020). Even a single session of treadmill-based stance slip and trip perturbation training resulted in significant adaptation among people with chronic stroke (PwCS) (Bhatt et al. 2019; Nevisipour et al. 2019; Dusane and Bhatt 2020). While preliminary studies have established the effectiveness of perturbation training in improving fall-resisting skills in PwCS and substantiating their preserved ability to acquire reactive adaptation for fall prevention, these studies were conducted in standing and utilized pull push perturbations or perturbations delivered using a motorized platform or treadmill-belt manipulations. Given the evidence of increased fall-risk especially during walking among PwCS (Hyndman et al. 2002), exposure to overground gait-slips induced using low friction moveable platforms might be ecologically more valid than motorized treadmill or platform induced stance perturbations, as during overground gait-slips the resulting slip intensity (displacement, velocity acceleration) is produced by one’s self-generated forces based on their gait pattern and hence would be more similar to a slip that one would experience in real-life (Kajrolkar and Bhatt 2016; Dusane et al. 2021). However, the effect of overground gait perturbation training on fall-resisting skills in PwCS remains to be determined.

Besides, few studies among PwCS have shown that prior perturbation training results in improved reactive responses on novel task/context (van Duijnhoven et al. 2018; Dusane et al. 2019); however, there is limited evidence examining the effect of prior perturbation training on the unexposed limb. Upper extremity studies in stroke have shown improved performance of the ipsilateral limb following training of the contralateral upper limb (Ausenda and Carnovali 2011; Iosa et al. 2013; Yoo et al. 2013). Evidence from perturbation-based studies in healthy adults have shown improved fall-resisting skills on the contralateral limb following motor adaptation of the ipsilateral limb (Van Hedel et al. 2002; Bhatt and Pai 2008; Marcori et al. 2020; McCrum et al. 2020). For example, the untrained limb demonstrated reduced number of compensatory steps to regain stability following split-belt treadmill induced gait-perturbations (McCrum et al. 2020) and improved performance gains post-unipedal balance training on a moveable platform (Marcori et al. 2020). Furthermore, Van Hedel et al (2002) demonstrated improvement in muscle activation, joint trajectories and foot clearance on the ipsilateral limb following training induced adaptation of the contralateral limb during an obstacle avoidance task while walking. Similarly, Bhatt et al. (2008) demonstrated partial improvement in reactive stability on the novel left-sided slip post-right-sided overground gait-slip training. Thus, it can be deduced that overground gait-perturbation paradigm would allow examination of contributions from both limbs for slip-fall prevention (Kajrolkar and Bhatt 2016; Dusane et al. 2021) and might be suitable to determine if prior training of ipsilateral limb improves gait-slip outcomes on novel contralateral limb in PwCS during walking. Furthermore, some studies have also examined the phenomenon of priming custom defined as rapid adaptation demonstrated after single slip exposure under the contralateral limb after training the ipsilateral limb (Tulving and Schacter 1990; Schacter and Buckner 1998). It can be postulated that priming results from the sensitization and the readiness of the CNS to use the acquired adaptive changes from the limb receiving repeated perturbations and apply to the unperturbed limb (Bhatt and Pai 2009).

Thus, the primary purpose of this study was to examine if PwCS can acquire adaptation to overground slips delivered under the non-paretic side and subsequently determine whether prior exposure to repeated non-paretic overground gait-slips could improve reactive responses on paretic side gait-slips. We first hypothesized that repeated exposure to nonparetic-side slips in PwCS will induce motor adaptation in their fall-resisting skills resulting in improved reactive stability and fall outcomes. We further hypothesized that such adaptation would result in performance gains on the paretic-side slips such that reactive stability will be higher in this group on the first novel slip (inter-limb gain) and on the immediate second slip (priming effect) than the corresponding paretic slips of control group receiving no prior nonparetic-side slips.

Methods

Participants

Forty-nine community dwelling PwCS (> 6 month post-cortical stroke), confirmed by their physician, who were able to ambulate independently with or without an assistive device were included in the study. Participants underwent in-person screening such that those with cognitive impairments (score of ≤ 26/30 on Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale), speech impairments (aphasia score of ≥ 71/100 on Mississippi Aphasia Screening Test), poor bone density (T score < −2 on the heel ultrasound), or any other self-reported neurological, musculoskeletal, or cardiovascular were excluded. Clinical outcome measures such as severity of motor impairment using the Chedoke–McMaster Stroke Assessment scale; functional balance measures using the Berg balance scale and Timed up and go test along with chronicity of stroke were performed. Participants were randomly assigned to either the adaptation group (n = 25) or to the control group (n = 24) using computer-generated random allocation sequence with allocation concealment. The demographic details of the included participants are presented in Table 1. All participants provided written informed consent as approved by the institutional review board of the University of Illinois at Chicago prior to their enrollment.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical outcome measures for study participants

| Adaptation group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 24 | n = 21 | |

| Age (years) | 57 ± 8.7 | 61 ± 12 |

| Height (m) | 1.71 ± 0.09 | 1.69 ± 0.11 |

| Weight (kg) | 81.01 ± 13.9 | 81.2 ± 18.36 |

| Gender (male/female) | 16/8 | 12/9 |

| Severity of disability (modified Rankin scale) | 2 ± 1 | 2.08 ± 1 |

| Stroke type (haemorrhagic/ischemic) | 7/14* | 7/14 |

| Chronicity of stroke (in years) | 11 ± 5.85 | 8.76 ± 4.19 |

| Impairment level | ||

| CMSA (leg) | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 |

| CMSA (foot) | 4 ± 1 | 4 ± 2 |

| Balance (BBS) | 49 ± 4 | 47 ± 9 |

| TUG (s) | 17.6 ± 8.13 | 19.7 ± 16.9 |

CMSA Chedoke–McMaster stroke assessment scale; BBS Berg balance scale; TUG timed up and go test; s seconds

Indicates stroke type for 3 participants in the adaptation group was missing

Repeated overground slip protocol

Slip protocol was performed using a customized overground perturbation system consisting of an 8-m-long walkway with two movable plates used to deliver perturbations. Prior to beginning the session, participants were firmly donned the safety harness to prevent from touching the ground during an event of fall. All the participants were made to walk on the instrumented walkway at their preferred speed for few trials to acquaint themselves to walking in the new laboratory environment. Participants were instructed at the beginning of the session that they ‘may or may not experience a slip under either of their limbs’. Participants were asked to try their best to recover their balance and continue walking on the walkway. The starting position for each participant was adjusted to ensure that they consistently land on the movable plate with their slipping limb and a sudden unexpected slip was induced using a computer-controlled release mechanism. All participants in the adaptation group received a block of total 8 consecutive slips under their non-paretic limb without any breaks in between. This was followed by few walking trials to reduce predictability and to ensure landing on the moveable plate with their paretic limb. Throughout the experiment, participants were unaware of which trial would be a slip trial and slip would be given under which limb. Subsequently unexpected, novel slip was induced under the paretic limb without any prior explicit information about change in the slipping limb (Fig. 1). This novel paretic slip was followed by a consecutive paretic slip. On the other hand, participants in the control group received an unexpected, novel paretic slip followed by a consecutive paretic slip. Both training and control groups were exposed to two consecutive paretic slips to examine priming effect on the paretic-side following exposure to repeated non-paretic slips. The slip distance for all the gait-slips was 45 cm.

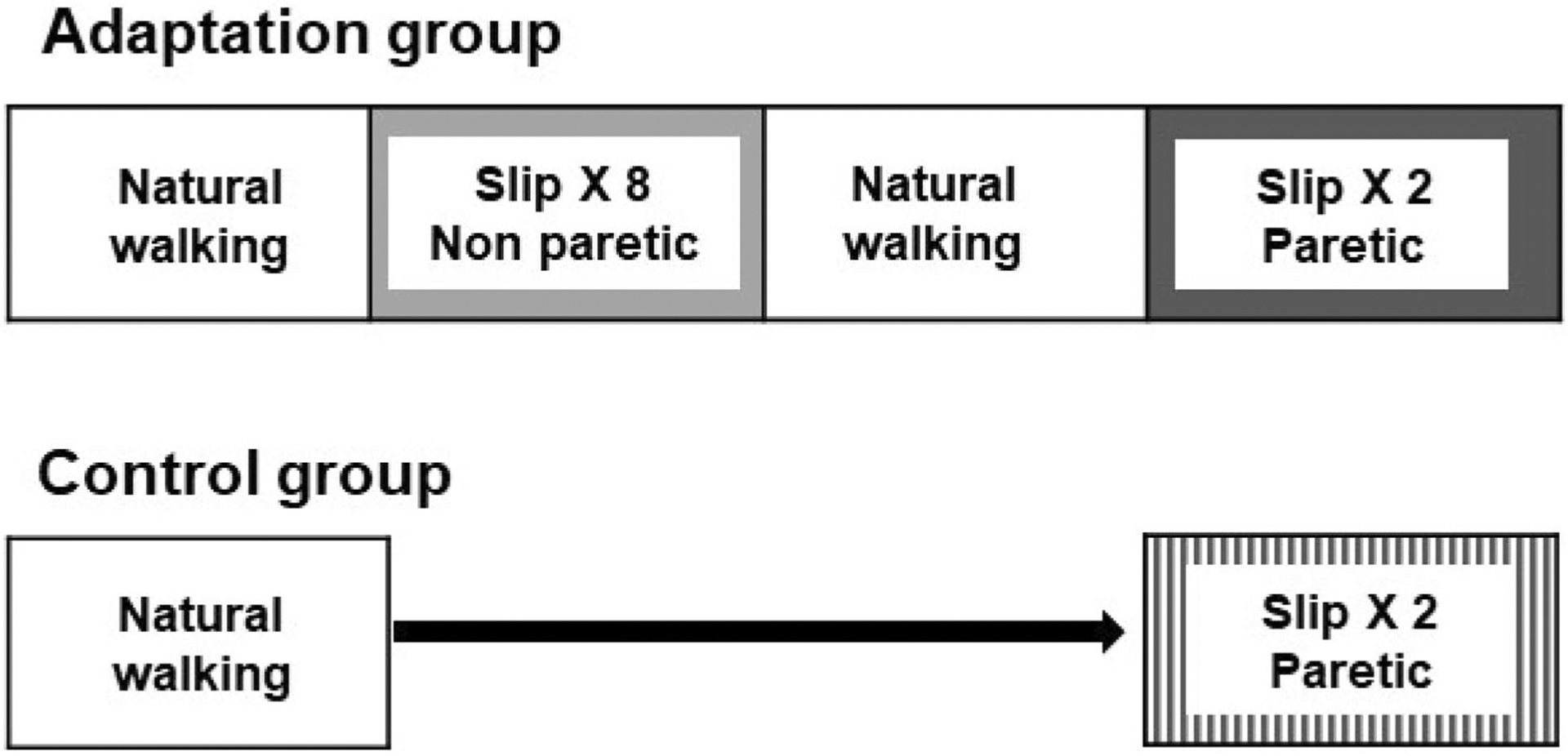

Fig. 1.

Testing protocol used with overground gait slip perturbations shown for both the adaptation and control group. Participants were randomized into either the adaptation or the control group. All participants were made to walk at their natural walking speed before the unexpected gait-slips. The adaptation group received a block of 8 consecutive overground gait-slips under the non-paretic limb (S1–S8). Following those eight slips, participants were made to walk at their natural walking speed until the paretic limb landed on the moveable platform followed by two paretic-side gait-slips. The control group was subjected to two unexpected gait-slip under the paretic limb following few natural walking trials

Data collection and analysis

An eight-camera motion capture system (Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA) was used to record full body kinematics using a set of 30 retro-reflective markers. Kinematic data was sampled at 120 Hz and synchronized with the force plate and load cell data, which was collected at 600 Hz. The instances of recovery step liftoff (LO) and touchdown (TD) were determined from the vertical ground reaction forces using a custom written Matlab program. The marker data collected for 2 participants was not complete (due to markers fallen off from the participants during the key slips trials of interest) and two participants had a mis-trigger of the slip plate for two key trials used for analysis. Therefore, data of these four participants was disregarded (three from the control group and one from the training group).

Outcome measures

Slip outcome: slip trials were categorized as a fall or a recovery. Fall was identified when the weight borne by the harness exceeded 30% of participant’s body weight, while the remaining slip trials were identified as a recovery (Yang and Pai 2011).

Recovery strategies: recovery strategies on slip trials were identified as backward loss of balance (BLOB), characterized by the need to execute a compensatory step (with contralateral recovery limb landing posterior to slipping limb) (Bhatt et al. 2005, 2006b) or as no loss of balance (NLOB), when compensatory stepping was not needed and the participants continued to maintain their regular walking pattern (recovery limb landing anterior to slipping limb)(Bhatt et al. 2006b).

Pre- and post-slip center of mass (CoM) state stability: the CoM state stability was calculated as the shortest distance from CoM state (instantaneous CoM position and velocity) to the computational threshold against BLOB during slipping (Pai and Iqbal 1999). CoM position was computed from 12 segment body representation (De Leva 1996), expressed relative to the posterior edge of the BOS (heel marker) and normalized by participant’s foot length. While CoM velocity was derived from CoM position, normalized by a dimensionless fraction of √g*h, where g is the acceleration due to gravity and h is the participant’s height and expressed relative to the BOS. The CoM stability values < 0 indicated a high possibility of BLOB, while CoM stability values > 0 indicated low possibility of BLOB. Stability was analyzed at the instance of initial touchdown (TD) relative to the slipping limb before slip onset (pre-slip TD), and at post-slip instances of liftoff (LO) and recovery TD relative to the slipping limb.

Post-slip stride length: post-slip stride length during gait-slip was calculated as the distance traveled by the metatarsal marker of the contralateral, recovery limb from its lift off to touchdown. In case of backward loss of balance (BLOB), the contralateral recovery limb landed posterior to the slipping limb and was termed as compensatory stride length while in case of no loss of balance, where compensatory step was not needed, the contralateral limb landed anterior to the slipping limb.

Slipping kinematics: maximum heel displacement and maximum heel velocity were calculated as the peak displacement (i.e., the distance covered by the slipping foot heel marker) and peak velocity (computed as first order derivative of heel displacement) between slipping limb TD to LO, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Both adaptation and control groups at baseline were compared using the Mann–Whitney test for stroke impairment, i.e., Modified Rankin Scale, CMSA leg and foot score, functional status, i.e., Berg balance scale score, Timed up and go test score and chronicity of stroke to determine homogeneity. To examine changes in adaptation following nonparetic-side slips, all 8 nonparetic-slips in the adaptation group were compared using Friedman’s test followed by planned comparisons with Wilcoxon-signed rank test for non-parametric variables (slip outcome and recovery strategy) (NPS1 vs NPS8). A One-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by planned comparisons using the paired t test was used for analysis of parametric variables (pre-slip stability at TD, post-slip stability at LO and TD, post-slip stride length, maximum heel displacement and velocity) (NPS1 vs NPS8).

Selected non-parametric variables such as slip outcome and parametric variables such as pre-slip stability at TD, post-slip stability at TD and maximum heel velocity were analyzed for the second aim examining effect of inter-limb gain and priming on the paretic side after nonparetic side adaptation. To determine inter-limb gain and priming effects the following analysis was done. For the adaptation group, planned comparisons were performed to determine differences in variables of interest between NPS1 vs PS1 and NPS8 vs PS1 using Wilcoxon-signed rank test and paired t test, respectively, for non-parametric and parametric variables. Between adaptation and control groups the 1st and 2nd paretic slips (PS1, PS2, CPS1 and CPS2) were compared using McNemar test (non-parametric) and 2 × 2 ANOVA (parametric). Within group comparison (PS1 vs PS2 and CPS1 vs CPS2) was performed using Wilcoxon-signed rank test and paired t test tests. Between groups comparison (PS1 vs CPS1 and PS2 vs CPS2) was performed using the Mann Whitney U test and the independent t test. Both within and between groups comparison analysis was performed with Bonferroni corrections.

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 24 with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

There were no significant differences noted in any baseline characteristics between the adaptation and control group in the Modified Rankin Scale (Z = − 0.79, p > 0.05), CMSA scores for leg (Z = − 0.33, p > 0.05) and CMSA scores for foot (Z = − 1.65, p > 0.05). In addition, there was no between groups difference in the functional status indicated by Berg balance scale score (Z = − 0.02, p > 0.05) and Timed up and go test score (Z = − 1.08, p > 0.05), and chronicity of stroke in years (Z = − 1.08, p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Nonparetic-side slip adaptation

Slip outcome and recovery strategy

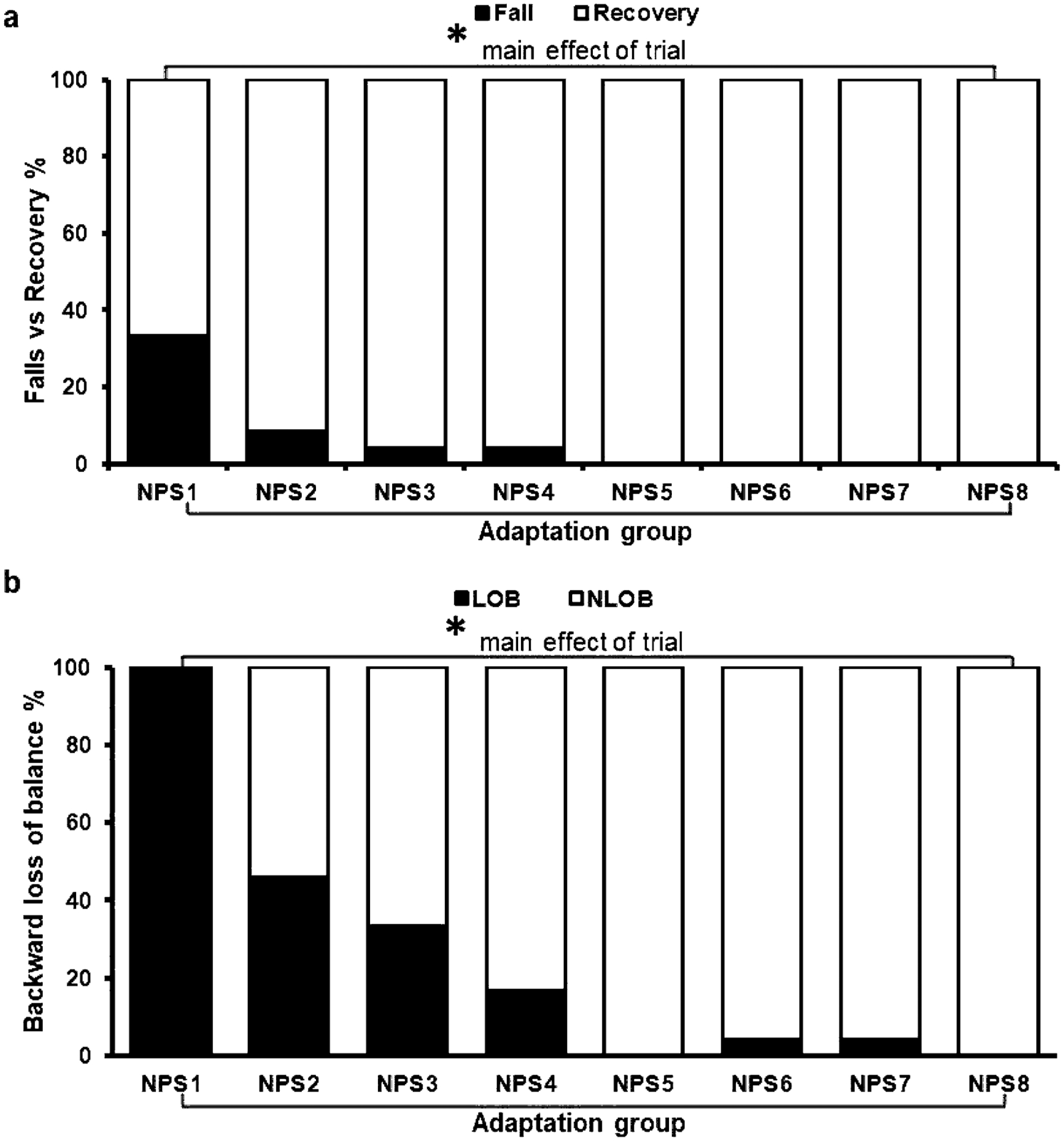

All participants in the adaptation group experienced a BLOB (including falls) on exposure to the first novel nonparetic-side slip (NPS1). Out of 100%, a total of 33% of participants experienced a fall on NPS1 (Fig. 2a). Over repeated nonparetic-side slips, there was a significant reduction in fall percentage from 33% (NPS1) to no falls (NPS8) (X2 = 41.6, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2a), further indicated by planned comparison NPS1 vs NPS8 (Z = − 2.82, p < 0.05). There was a significant reduction in the incidence of BLOB from 100% on NPS1 to no loss of balance (NLOB) on NPS8 (X2 = 103.6, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b), further indicated by planned comparison NPS1 vs NPS8 (Z = − 4.89, p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Showing (a) falls vs recovery and (b) backward loss of balance (BLOB) vs no loss of balance (NLOB) for the adaptation group during the eight consecutive overground gait-slips under the non-paretic limb. Significant differences(p < 0.05) are indicated by*

Stability

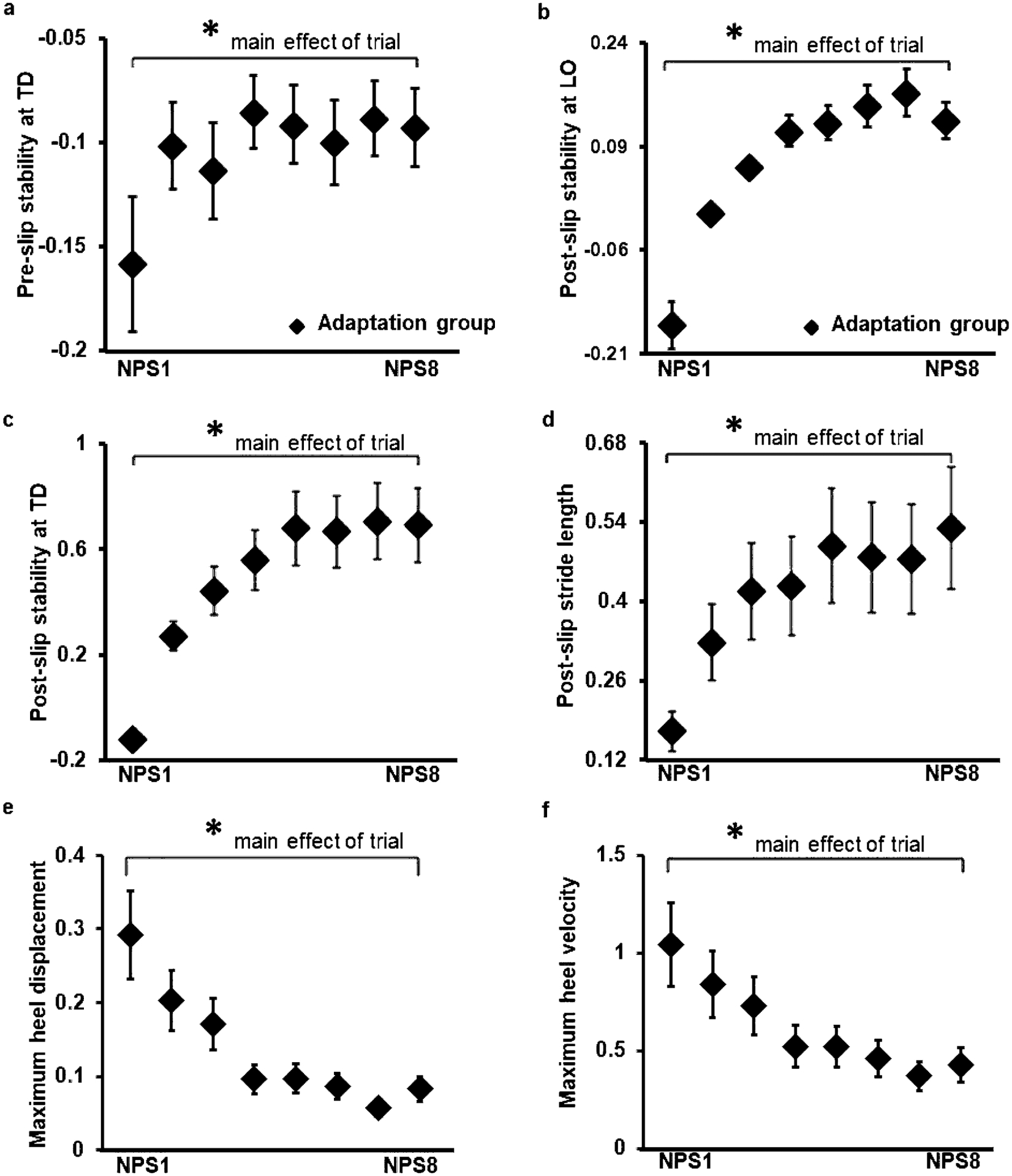

All participants demonstrated improvement in pre-slip and post-slip stability following repeated nonparetic-side slips. Although a significant main effect of trial on pre-slip stability at TD [F (7, 147) = 2.04, p < 0.05] was noted (Fig. 3a), planned comparison between non-paretic first slip (S1) and last slip (S8) demonstrated no significant difference in pre-slip stability (p > 0.05, 95% CI = − 0.14, 0.009). The post-slip stability analysis demonstrated a significant main effect of trial at LO [F (7, 154) = 21.24, p < 0.05] (Fig. 3b) and TD [F (7, 154) = 30.34, p < 0.05] (Fig. 3c) with a significant increase in stability from S1 to S8 for LO (p < 0.05, 95% CI = − 0.36, − 0.22) and TD (p < 0.05, 95% CI = − 0.95, − 0.67), respectively.

Fig. 3.

Showing mean and standard deviation for: (a) pre-slip stability at touchdown (TD), (b) post-slip stability at lift off (LO), (c) post-slip stability at recovery step TD, (d) post-slip stride length, (e) maximum heel displacement and (f) maximum heel velocity of the adaptation group during the eight consecutive overground gait slips under the non-paretic limb. Significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated by*

Post-slip stride length

Increased CoM stability was accompanied with a significant main effect of trial for post-slip stride length of the stepping paretic limb [F (7, 154) = 20.13, p < 0.05] (Fig. 3d) indicating an increase from S1 to S8 (p < 0.05, 95% CI = − 0.42, − 0.29).

Slipping kinematics

There was a significant main effect of trial for maximum heel displacement [F (7, 147) = 15.8, p < 0.05] (Fig. 3e) and maximum heel velocity [F (7, 147) = 17.5, p < 0.05] (Fig. 3f). Planned comparisons indicated a significant decrease in displacement (p < 0.05, 95% CI = 0.15, 0.26) and velocity (p < 0.05, 95% CI = 0.47, 0.75) from S1 to S8, respectively.

Effect of prior nonparetic-side slip adaptation on novel paretic slip

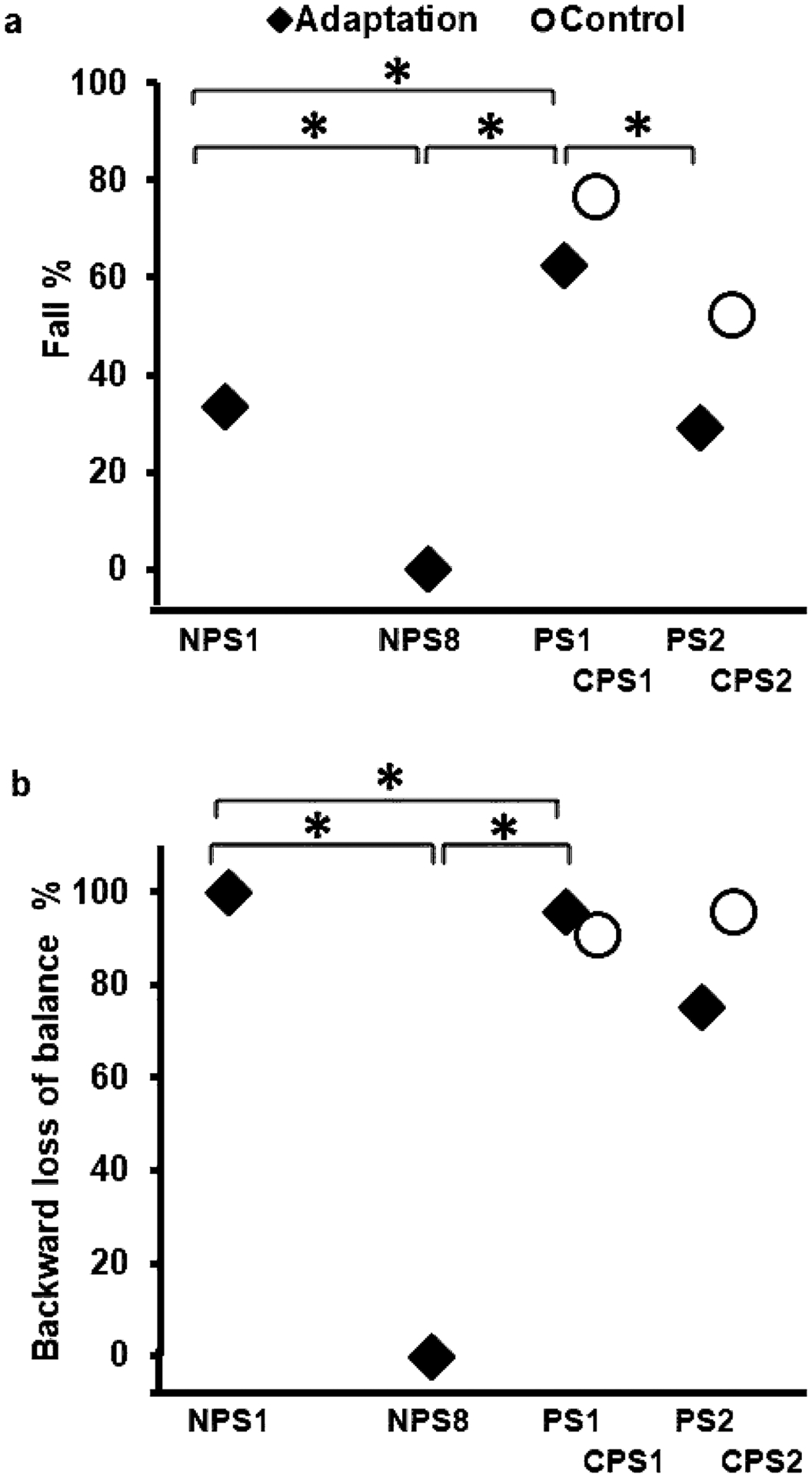

Novel slips of adaptation group demonstrated a significant increase in falls between NPS1 (33%) and PS1 (63%) (Z = − 2.11, p < 0.05) and between NPS8 (0%) and PS1 (63%) (Z = − 3.87, p < 0.05) (Fig. 4a). While no significant difference was noted in BLOB between NPS1 (100%) and PS1 (96%) (Z = − 1, p > 0.05), a significant increase in BLOB between NPS8 (0%) and PS1 (96%) (Z = − 4.79, p < 0.05) was seen (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Showing (a) falls vs recovery and (b) backward loss of balance (BLOB) vs no loss of balance (NLOB) of both the adaptation group and the control group for non-paretic and paretic overground gait-slips. Significant differences are indicated by*. Solid line indicates difference between trials of the adaptation group, while dotted line indicates difference between trials of the control group

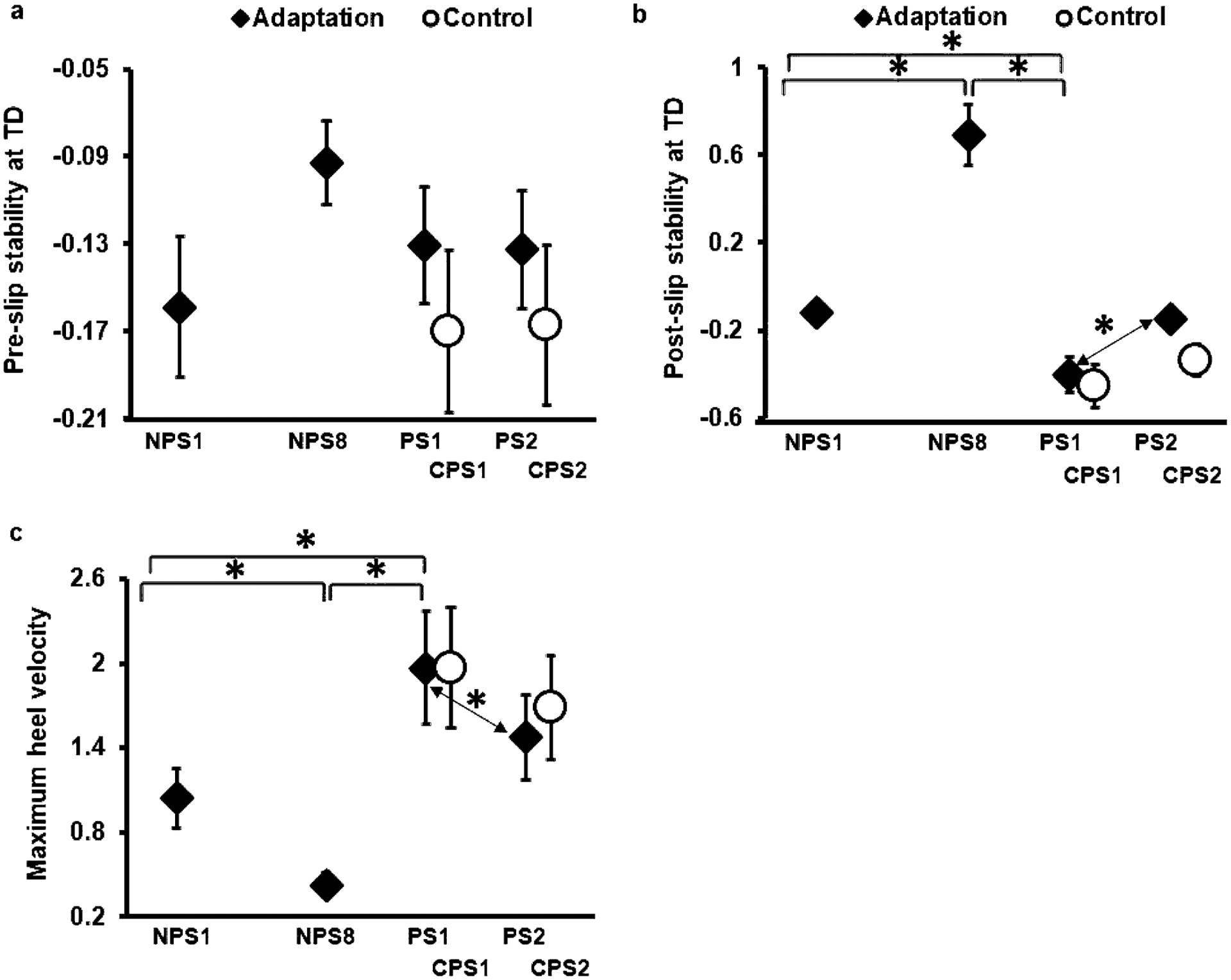

Planned comparison within the adaptation group showed that pre-slip stability at TD on PS1 was comparable to that on NPS1 (p > 0.05, 95% CI = − 0.11, 0.05) and NPS8 (p > 0.05, 95% CI = − 0.01, 0.08) (Fig. 5a). Whereas the post-slip stability at TD on PS1 was significantly lower than NPS1 (p < 0.05, 95% CI = 0.09, 0.46) and NPS8 (p < 0.05, 95% CI = 0.93, 1.24) (Fig. 5b). In addition, there was a significant increase in heel velocity on PS1 compared to NPS1 (p < 0.05, 95% CI = − 1.2, − 0.64) and NPS8 (p < 0.05, 95% CI = − 1.81, − 1.26), respectively (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Showing mean and standard deviation for: (a) pre-slip stability at TD, (b) post-slip stability at TD, and (c) maximum heel velocity of both the adaptation and control group for non-paretic and paretic over ground gait-slips. Significant differences are indicated by*. Solid line indicates difference between trials of the adaptation group, while dotted line indicates difference between trials of the control group

Priming effect on paretic-side slip

Comparison of 1st and 2nd paretic slips of both groups, i.e., PS1, PS2, CPS1 and CPS2 showed significant difference in falls (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4a); however, no difference was noted in BLOB (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4b). There was no significant between groups difference in falls between PS1 and CPS1 (U = 217.5, p > 0.01), and between PS2 and CPS2 (U = 204, p > 0.01) (Fig. 4a). Within the adaptation group, PS2 showed a significant decrease in falls compared to PS1 (Z = − 2.33, p < 0.01), while the control group demonstrated no significant difference between PS1 and PS2 (Z = − 2.23, p > 0.01).

A 2 × 2 ANOVA for pre-slip stability at TD including PS1, PS2, CPS1 and CPS2 trials of both groups resulted in no significant main effect [F (1, 43) = 0.23, p > 0.05], group effect [F (1, 43) = 1.43, p > 0.05] and time *group interaction [F (1, 43) = 0.35, p > 0.05] (Fig. 5a). While post-slip stability at TD demonstrated a significant main effect [F (1, 43) = 11.53, p < 0.05], there was no group effect [F (1, 43) = 1.92, p > 0.05] and time *group interaction [F (1, 43) = 1.54, p > 0.05] noted. There was no significant between groups difference in post-slip stability at TD between PS1 and CPS1 (p > 0.01, 95% CI = − 0.12, 0.23), and between PS2 and CPS2 (p > 0.01, 95% CI = − 0.03, 0.41) (Fig. 5b). Within the adaptation group, PS2 showed a significant increase in post-slip stability at TD (p < 0.01, 95% CI = − 0.42, − 0.86) compared to PS1, while control group demonstrated no significant difference in post-slip stability at TD between CPS1 and CPS2 (p > 0.01, 95% CI = − 0.26, 0.03).

A 2 × 2 ANOVA for maximum heel velocity including PS1, PS2, CPS1 and CPS2 trials of both groups resulted in a significant main effect [F (1, 41) = 21.62, p < 0.05] and time *group interaction [F (1, 41) = 4.13, p < 0.05]; however, there was no group effect noted [F (1, 41) = 0.09, p > 0.05]. Between groups comparison resulted in no significant difference in maximum heel velocity between PS1 and CPS1 (p > 0.01, 95% CI = − 0.39, 0.4), and between PS2 and CPS2 (p > 0.01, 95% CI = − 0.63, 0.21) (Fig. 5c). Within the adaptation group, PS2 showed a significant decrease in velocity (p < 0.01, 95% CI = 0.25, 0.72) compared to PS1. However, the control group demonstrated no significant difference in velocity between CPS1 and CPS2 (p > 0.01, 95% CI = 0.02, 0.35) (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

Our results supported our first hypothesis that PwCS demonstrated successful proactive and reactive adaptation for acquiring fall-resisting skills following repeated overground nonparetic-side gait-slips. However, our results only partially supported the second hypothesis. Following prior exposure to nonparetic-slips PwCS in the adaptation group showed no inter-limb performance gain on the novel paretic slip. Nonetheless, evidence of priming in this group was indicated by the significant performance gain from their first to the second paretic-side slip compared to that seen in the control group (receiving no prior non-paretic slip exposure) for the same two trials.

Adaptation to overground nonparetic-side slips

On the novel overground nonparetic-side gait-slip (S1), all participants demonstrated a negative CoM stability at both pre- and post-slip instances (Fig. 3a, b, c). Since participants were unaware of the exact timing of the upcoming novel slip, they demonstrated a lower pre-slip CoM stability at TD. Similar to previous studies in healthy adults (Bhatt et al. 2006b; Espy et al. 2010; Pai et al. 2010) and PwCS (Kajrolkar et al. 2014; Kajrolkar and Bhatt 2016), all participants exhibited a negative CoM stability at post-slip LO signifying that the COM state lay below the computational threshold of backward balance loss (Pai and Patton 1997). This indicated that the COM position was more posterior to the anteriorly moving slipping base of support and its velocity moving slower than the velocity of the base of support. Thus, all participants with nonparetic-side slip demonstrated a BLOB associated with or without a fall (Fig. 2b) and performed a compensatory stepping response using their otherwise non-preferred, paretic limb. The compensatory stepping performed by PwCS in response to large magnitude slip helped to re-establish a greater BoS via longer post-slip stride length and provide rotational counter-torque at recovery TD to restrain further posterior CoM displacement (Maki and McIlroy 1997). Such longer post-slip stride length led to significant reduction of BLOB over repeated nonparetic-side slips. Thus, our results indicated that PwCS in the adaptation group demonstrated improved reactive responses with a single block of nonparetic-side gait-slips.

Similar to healthy adults (Bhatt et al. 2006a, 2006b), with repeated nonparetic-side slips, PwCS demonstrated rapid adaptive changes in anticipatory and reactive balance control. Following the novel nonparetic-side slip, participants’ demonstrated improved pre-slip stability at TD (Fig. 3a), which might be associated with anticipatory adjustments in the form of reduced step length, flat foot landing and increased knee flexion (Cham and Redfern 2002; Marigold and Patla 2002; Lockhart et al. 2003). It can be postulated that repeated exposure to non-paretic slips might have resulted in recalibration of the internal representation of stability limits against BLOB, wherein the CNS updates the existing models or builds new models leading to an emergence of a predictive feedforward control (Kawato and Gomi 1992; Bhushan and Shadmehr 1999; Witney et al. 1999). Such control leads to proactive adjustments in a pre-defined way based on prior experiences to improve pre-slip stability in anticipation of a similar upcoming perturbation (Cham and Redfern 2002; Marigold and Patla 2002; Pai et al. 2003). Such anticipatory changes along with adaptive changes in reactive control in the early phase post-slip have been known to alter the braking impulse and reduce slip intensity, thereby reducing the reliance on reactive responses via feedback processes for fall prevention (Bhatt et al. 2006a, 2006b; Wang et al. 2020). PwCS similarly demonstrated a reduced slip intensity (displacement and velocity) under non-paretic limb (Fig. 3e, f) and improved stride length (Fig. 3d) of the stepping paretic limb resulting in an increased postural stability both at liftoff and post-slip touchdown of the recovery step. Thus, PwCS demonstrated a significant decreased in BLOB from NPS1 to NPS8 resulting in emergence of an increased incidence of NLOB (well-restored balance) leading to reduced falls (Fig. 2a, b).

Facilitation of reactive response on novel paretic slip and priming effect

Within the adaptation group, our results indicate that although both novel nonparetic- and paretic-side slips demonstrated comparable BLOB and pre-slip stability at TD, there was significantly greater falls noted on the first paretic-side slip (Figs. 4a, b, 5a). This might be associated with impaired reactive control from the paretic limb to effectively control the slipping kinematics resulting in significantly greater post-slip heel velocity and hence a lower post-slip stability at TD, similar to that previously reported in Dusane (2021) (Fig. 5b, c).

It must be noted that while there may be limited generalization, we do not think there could be an interference resulting from any proactive adaptation. It has been previously shown that improved pre-slip stability following exposure to repeated gait-slips under one limb facilitated improvements with reduced fall incidence on slipping the other limb, thereby indicative of transfer effect rather than interference among healthy adults (Bhatt and Pai 2008). On similar lines, while our findings demonstrated a significant main effect of trial on pre-slip stability at TD with repeated non-paretic slips and comparable proactive stability between the last non-paretic slip (NP-S8) and the subsequent novel paretic slip (P-S1), such changes in PwCS might not be sufficient or large enough to compensate for impairment-induced reduction in reactive balance control on the paretic side to affect outcome determination.

Previous studies have postulated that with repeated perturbations the CNS updates the internal representation of the stability limits, and sensitizes the central set (Bhushan and Shadmehr 1999; Witney et al. 1999) along with contributions from anticipatory changes induced during walking (before slip onset). The internal representation undergoes recalibration followed by downloading the information from the side receiving repeated perturbations and effectively applying it to the unperturbed side, thereby developing a non-effector specific generalized motor program (Sainburg and Wang 2002). Moreover, the knowledge of upcoming perturbation and knowledge of performance during training facilitates improved recovery response on the unperturbed limb (Van Hedel et al. 2002; Bhatt and Pai 2009). Van Hedel et al (2002) informed the participants about upcoming obstacle via a warning sign (explicit acoustic feedback), thus resulting in improved recovery on the unperturbed limb. Similarly, Bhatt et al. (2009) demonstrated that knowledge of upcoming slip resulted in a better gait-slip outcome compared to the group without any knowledge of impeding left slip after slip training under the right limb.

Given the nature of overground gait-slips, it must also be noted that both the limbs perform different functions during non-paretic and paretic slips for effective recovery. During gait-slip, the slipping nonparetic-side aim to reduce the slip intensity and maintain vertical limb support, while the trailing paretic side performs compensatory stepping by generation of an adequate propulsive impulse. These task demands are reversed while testing for effect of prior exposure to slips on recovery from unexposed slip. Thus, in the absence of any explicit information or warning cue, the CNS may not be able to sufficiently transfer acquired limb specific information due to limited communication between both hemispheres (Sainburg and Wang 2002; Bloom and Hynd 2005; Perez et al. 2007; Bhatt and Pai 2008, 2009), further affected by presence of a stroke induced cortical lesion. It is also postulated that cognitive bias while predicting the upcoming slip might impede the inter-hemispheric communication resulting in inability of the CNS to employ acquired adaptive changes to contralateral effector system (Bhatt and Pai 2008).

However, even with a lesioned cortex the participants in the adaptation group were able to demonstrate a priming effect compared to the control group, resulting from the prior exposure to nonparetic-side slips. Previous evidence indicates that PwCS have greater difficulty recovering from large magnitude slips under the paretic-side compared to the non-paretic side (Dusane et al. 2021). Our findings show that on the 2nd paretic slip the adaptation group demonstrated significant improvement in performance, with reduction in falls from 63 to 33% (Fig. 4a), along with an associated increase in post-slip stability at recovery TD due to reduction in maximum heel velocity (Fig. 5b, c). Although there was a lack of significant between group difference on PS2 between the adaptation and control group, a significant improvement in performance (post-slip stability and balance loss) from PS1 to PS2 in the adaptation group compared to the non-significant change seen in the control group (CPS1 and CPS2) provides support for a possible priming effect on the paretic-side. It can be postulated that previous exposure to repeated nonparetic-side slips sensitizes the generalized motor program such that exposure to a single paretic-side slip facilitates improved recovery on the second slip rather than the natural course of adaptation (Sainburg and Wang 2002; Wang and Sainburg 2003). In summary, it is possible that greater or robust changes in pre-slip stability and/or a higher dosage of non-paretic slips and/or more knowledge of upcoming slip context conditions could facilitate transfer between the limbs or induce a stronger priming effect resulting in improved or equal slip outcomes and stability on the paretic side.

Our current findings could have significant clinical implications for fall-risk reduction in PwCS. Our results are indicative of the application of overground slip-perturbation training to enhance fall-resisting skills in PwCS and that such training could be incorporated as part of stroke rehabilitation to improve locomotor balance control and lower fall-risk under both limbs. Our results were also suggestive of the need for bilateral perturbation training to reduce fall-risk among PwCS. However, the findings of this study must be interpreted with caution considering certain limitations. The exposure to only eight, large magnitude slips may not be sufficient to facilitate improved recovery on novel paretic slip in PwCS and exposure to more gait-slips might be beneficial. The study design did not allow for a paretic pre-test slip to be given before exposing participants to non-paretic side slips. However, this was done intentionally to keep the paretic slips “novel”. Participants were also completely unaware of the timing (trial) of the first paretic slip. It is possible that prior information and the awareness of the upcoming paretic slip could have resulted in better performance on this side. Furthermore, it is not yet known if individuals with sub-acute or acute stroke will demonstrate similar adaptation and priming results.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that PwCS have the preserved ability to demonstrate immediate proactive and reactive adaptation with overground, nonparetic-side gait-slips. While cortical stroke impeded improvement in their reactive responses on novel paretic-side slip (inter-limb performance gain) despite prior exposure to non-paretic slips, PwCS in the adaptation group demonstrated priming effect on the paretic-side slips compared to the control group receiving no prior nonparetic-slip exposure. Our findings are suggestive of a need for bilateral perturbation training to reduce fall-risk on both non-paretic and paretic-side among PwCS.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Riddhi Panchal, MS PT, Lakshmi Kannan, MS PT and Rachana Gangwani, BPT for assistance with data collection, and Shuaijie Wang, PhD for assistance with data analysis.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH) [1R01HD088543-01A1] awarded to Dr. Tanvi Bhatt.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval This research was approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago, Human Subject Research Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Protocol #2016–0933).

Data availability

The original data will be made available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- Arya KN, Pandian S, Verma R, Garg R (2011) Movement therapy induced neural reorganization and motor recovery in stroke: a review. J Bodyw Mov Ther 15:528–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausenda C, Carnovali M (2011) Transfer of motor skill learning from the healthy hand to the paretic hand in stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 47:417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baguma M, Doost MY, Riga A, Laloux P, Bihin B, Vandermeeren Y (2020) Preserved motor skill learning in acute stroke patients. Acta Neurologica Belgica 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban B, Tok F (2014) Gait disturbances in patients with stroke. PMR 6:635–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansil S, Prakash N, Kaye J, Wrigley S, Manata C, Stevens-Haas C, Kurlan R (2012) Movement disorders after stroke in adults: a review. Tremor and other hyperkinetic movements 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor FA, Mackintosh SF, Said CM, Hill KD (2012) Falls after stroke. Int J Stroke 7:482–490. 10.1111/j1747-4949.2012.00796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt T, Pai YC (2008) Immediate and latent interlimb transfer of gait stability adaptation following repeated exposure to slips. J Mot Behav 40:380–390. 10.3200/jmbr.40.5.380-390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt T, Pai Y-C (2009) Role of cognition and priming in interlimb generalization of adaptive control of gait stability. J Mot Behav 41:479–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt T, Wening J, Pai Y-C (2005) Influence of gait speed on stability: recovery from anterior slips and compensatory stepping. Gait Posture 21:146–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt T, Wang E, Pai Y-C (2006a) Retention of adaptive control over varying intervals: prevention of slip-induced backward balance loss during gait. J Neurophysiol 95:2913–2922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt T, Wening J, Pai Y-C (2006b) Adaptive control of gait stability in reducing slip-related backward loss of balance. Exp Brain Res 170:61–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt T, Dusane S, Patel P (2019) Does severity of motor impairment affect reactive adaptation and fall-risk in chronic stroke survivors? J Neuroeng Rehabil 16:43. 10.1186/s12984-019-0510-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan N, Shadmehr R (1999) Computational nature of human adaptive control during learning of reaching movements in force fields. Biol Cybern 81:39–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JS, Hynd GW (2005) The role of the corpus callosum in inter-hemispheric transfer of information: excitation or inhibition? Neuropsychol Rev 15:59–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyne P, Scholl V, Doren S et al. (2020) Locomotor training intensity after stroke: effects of interval type and mode. Top Stroke Rehabil 27:483–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cham R, Redfern MS (2002) Changes in gait when anticipating slippery floors. Gait Posture 15:159–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leva P (1996) Adjustments to Zatsiorsky-Seluyanov’s segment inertia parameters. J Biomech 29:1223–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan PW, Zorowitz R, Bates B et al. (2005) Management of adult stroke rehabilitation care: a clinical practice guideline. Stroke 36:e100–e143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusane S, Bhatt T (2020) Mixed slip-trip perturbation training for improving reactive responses in people with chronic stroke. J Neurophysiol 124:20–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusane S, Wang E, Bhatt T (2019) Transfer of reactive balance adaptation from stance-slip perturbation to stance-trip perturbation in chronic stroke survivors. Restor Neurol Neurosci 37:469–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusane S, Gangwani R, Patel P, Bhatt T (2021) Does stroke-induced sensorimotor impairment and perturbation intensity affect gait-slip outcomes? J Biomech 118:110255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy DD, Yang F, Bhatt T, Pai Y-C (2010) Independent influence of gait speed and step length on stability and fall risk. Gait Posture 32:378–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handelzalts S, Kenner-Furman M, Gray G, Soroker N, Shani G, Melzer I (2019) Effects of perturbation-based balance training in subacute persons with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 33:213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman D, Ashburn A, Stack E (2002) Fall events among people with stroke living in the community: circumstances of falls and characteristics of fallers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 83:165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosa M, Morone G, Ragaglini M, Fusco A, Paolucci S (2013) Motor strategies and bilateral transfer in sensorimotor learning of patients with subacute stroke and healthy subjects. A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 49:291–299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajrolkar T, Bhatt T (2016) Falls-risk post-stroke: examining contributions from paretic versus non paretic limbs to unexpected forward gait slips. J Biomech 49:2702–2708. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajrolkar T, Yang F, Pai YC, Bhatt T (2014) Dynamic stability and compensatory stepping responses during anterior gait-slip perturbations in people with chronic hemiparetic stroke. J Biomech 47:2751–2758. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.04.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawato M, Gomi H (1992) A computational model of four regions of the cerebellum based on feedback-error learning. Biol Cybern 68:95–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart TE, Woldstad JC, Smith JL (2003) Effects of age-related gait changes on the biomechanics of slips and falls. Ergonomics 46:1136–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki BE, McIlroy WE (1997) The role of limb movements in maintaining upright stance: the “change-in-support” strategy. Phys Ther 77:488–507. 10.1093/ptj/77.5.488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield A, Schinkel-Ivy A, Danells CJ et al. (2017) Does perturbation training prevent falls after discharge from stroke rehabilitation? A prospective cohort study with historical control. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 26:2174–2180. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.04.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcori AJ, Teixeira LA, Mathias KR, Dascal JB, Okazaki VH (2020) Asymmetric interlateral transfer of motor learning in unipedal dynamic balance. Exp Brain Res 238(12):2745–2751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigold DS, Patla AE (2002) Strategies for dynamic stability during locomotion on a slippery surface: effects of prior experience and knowledge. J Neurophysiol 88:339–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrum C, Karamanidis K, Grevendonk L, Zijlstra W, Meijer K (2020) Older adults demonstrate interlimb transfer of reactive gait adaptations to repeated unpredictable gait perturbations. GeroScience 42:39–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JL, Roth EJ, Killian C, Hornby TG (2010) Locomotor training improves daily stepping activity and gait efficiency in individuals poststroke who have reached a “plateau” in recovery. Stroke 41:129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevisipour M, Grabiner M, Honeycutt C (2019) A single session of trip-specific training modifies trunk control following treadmill induced balance perturbations in stroke survivors. Gait Posture 70:222–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niam S, Cheung W, Sullivan PE, Kent S, Gu X (1999) Balance and physical impairments after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 80:1227–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai Y-C, Iqbal K (1999) Simulated movement termination for balance recovery: can movement strategies be sought to maintain stability in the presence of slipping or forced sliding? J Biomech 32:779–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai Y-C, Patton J (1997) Center of mass velocity-position predictions for balance control. J Biomech 30:347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai Y-C, Wening J, Runtz E, Iqbal K, Pavol M (2003) Role of feedforward control of movement stability in reducing slip-related balance loss and falls among older adults. J Neurophysiol 90:755–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai Y-C, Bhatt T, Wang E, Espy D, Pavol MJ (2010) Inoculation against falls: rapid adaptation by young and older adults to slips during daily activities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 91:452–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AT, Duncan PW, Lai S-M, Studenski S (2000) The relation between impairments and functional outcomes poststroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81:1357–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez MA, Wise SP, Willingham DT, Cohen LG (2007) Neurophysiological mechanisms involved in transfer of procedural knowledge. J Neurosci 27:1045–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platz T, Denzler P, Kaden B, Mauritz K-H (1994) Motor learning after recovery from hemiparesis. Neuropsychologia 32:1209–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman DS, Block HJ, Bastian AJ (2005) Interlimb coordination during locomotion: what can be adapted and stored? J Neurophysiol 94:2403–2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman DS, Wityk R, Silver K, Bastian AJ (2007) Locomotor adaptation on a split-belt treadmill can improve walking symmetry post-stroke. Brain 130:1861–1872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman DS, Wityk R, Silver K, Bastian AJ (2009) Split-belt treadmill adaptation transfers to overground walking in persons poststroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 23:735–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL, Wang J (2002) Interlimb transfer of visuomotor rotations: independence of direction and final position information. Exp Brain Res 145:437–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Buckner RL (1998) Priming and the brain. Neuron 20:185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel-Ivy A, Huntley AH, Aqui A, Mansfield A (2019) Does perturbation-based balance training improve control of reactive stepping in individuals with chronic stroke? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 28:935–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatemichi T, Desmond D, Stern Y, Paik M, Sano M, Bagiella E (1994) Cognitive impairment after stroke: frequency, patterns, and relationship to functional abilities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57:202–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasell R, Bayona NA, Bitensky J (2005) Plasticity and reorganization of the brain post stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 12:11–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E, Schacter DL (1990) Priming and human memory systems. Science 247:301–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijnhoven HJ, Roelofs J, den Boer JJ et al. (2018) Perturbation-based balance training to improve step quality in the chronic phase after stroke: a proof-of-concept study. Front Neurol 9:980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hedel H, Biedermann M, Erni T, Dietz V (2002) Obstacle avoidance during human walking: transfer of motor skill from one leg to the other. J Physiol 543:709–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Sainburg RL (2003) Mechanisms underlying interlimb transfer of visuomotor rotations. Exp Brain Res 149:520–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wang Y, Pai Y-CC, Wang E, Bhatt T (2020) Which are the key kinematic and kinetic components to distinguish recovery strategies for overground slips among community-dwelling older adults? J Appl Biomech 1:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witney AG, Goodbody SJ, Wolpert DM (1999) Predictive motor learning of temporal delays. J Neurophysiol 82:2039–2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Pai Y-C (2011) Automatic recognition of falls in gait-slip training: harness load cell based criteria. J Biomech 44:2243–2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo I-g, Jung M-y, Yoo E-y, Park S-h, Park J-h, Lee J, Kim H-s (2013) Effect of specialized task training of each hemisphere on inter-limb transfer in individuals with hemiparesis. NeuroRehabilitation 32:609–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original data will be made available from the corresponding author on request.