Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)‐T cell therapies have improved the outcome for many patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell lymphomas. In 2017, axicabtagene ciloleucel and soon after tisagenlecleucel became the first approved CAR‐T cell products for patients with high‐grade B‐cell lymphomas or diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who are relapsed or refractory to ≥ 2 prior lines of therapy; lisocabtagene maraleucel was approved in 2021. Safety and efficacy outcomes from the pivotal trials of each CAR‐T cell therapy have been reported. Despite addressing a common unmet need in the large B‐cell lymphoma population and utilizing similar CAR technologies, there are differences between CAR‐T cell products in manufacturing, pivotal clinical trial designs, and data reporting. Early reports of commercial use of axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel provide the first opportunities to validate the impact of patient characteristics on the efficacy and safety of these CAR‐T cell therapies in the real world. Going forward, caring for patients after CAR‐T cell therapy will require strategies to monitor patients for sustained responses and potential long‐term side effects. In this review, product attributes, protocol designs, and clinical outcomes of the key clinical trials are presented. We discuss recent data on patient characteristics, efficacy, and safety of patients treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel or tisagenlecleucel in the real world. Finally, we discuss postinfusion management and preview upcoming clinical trials of CAR‐T cell therapies.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the past three decades, the use of genetically modified autologous cells to treat cancer has moved from concept to clinical trial to the clinic. The most successful technique to date is the introduction of a modified T‐cell receptor into autologous T cells to target specific cell‐surface molecules on malignant cells and mediate their elimination. 1 Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) that target the CD19 antigen on B cells have demonstrated significant efficacy and reasonable safety in patients with relapsed or refractory (r/r) diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL), high‐grade B‐cell lymphoma (HGBCL), DLBCL arising from transformed follicular lymphoma (tFL), and primary mediastinal B‐cell lymphoma (PMBCL). 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6

The first CAR‐T cell therapy to be approved for patients with these lymphomas who have relapsed or progressed after two lines of systemic therapy was axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi‐cel) in 2017. 7 This was followed by approval of tisagenlecleucel (tisa‐cel) in 2018 (except for patients with PMBCL). 8 Most recently, lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso‐cel) was approved in 2021 (includes follicular lymphoma grade 3B [FL3B]). 9 This review explores the clinical trial designs, efficacy and safety results, and practical considerations for patient identification and treatment with CAR‐T cell therapies.

2. CAR CONSTRUCT CHARACTERISTICS

All three products share a core CAR structure: an extracellular anti‐CD19 binding domain (derived from the murine monoclonal antibody FMC63), a transmembrane region, an intracellular co‐stimulatory domain, and an intracellular T‐cell receptor CD3ζ signaling domain (Table 1). 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 10 , 11 , 12 Axi‐cel utilizes a CD28 co‐stimulatory domain, whereas tisa‐cel and liso‐cel both use 4‐1BB. After CD19 binding by the extracellular domain, the CD28 or 4‐1BB elements effectively provide the second signal together with CD3ζ to initiate intracellular T‐cell signaling. CD28 co‐stimulation results in early, rapid CAR‐T cell expansion but relatively limited long‐term CAR‐T cell persistence. 13 , 14 In vitro studies have shown that CD28 mediates immediate antitumor activity; 4‐1BB co‐stimulation leads to a more gradual time to peak expansion and longer persistence of CAR‐T cells which, in vitro, is associated with increased central memory T‐cell differentiation, enduring tumor cell killing, and immunosurveillance. 13 , 14 However, the degree to which these alternate co‐stimulatory domains impact clinical efficacy remains unclear.

TABLE 1.

CAR constructs and trial design

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel ZUMA‐1 4 | Tisagenlecleucel JULIET 2 , 10 , 11 | Lisocabtagene maraleucel TRANSCEND 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR |

α CD19 α CD19 |

α CD19 α CD19 |

α CD19 α CD19 |

|

| Transmembrane domain | CD28 | CD8 | CD28 | |

| Co‐stimulatory domain | CD28 | 4‐1BB | 4‐1BB | |

| T‐cell activation domain | CD3ζ | CD3ζ | CD3ζ | |

| Leukapheresis | Fresh product direct to manufacturing (within US) | Cryopreserved product (could be stored before manufacturing) | Fresh product direct to manufacturing (within US) | |

| Conditioning therapy | Cyclophosphamide‐fludarabine (500 mg/m2, 30 mg/m2 daily × 3 days) | Cyclophosphamide‐fludarabine (250 mg/m2, 25 mg/m2 daily × 3 days) or Bendamustine (90 mg/m2 daily × 2 days) a | Cyclophosphamide‐fludarabine (300 mg/m2, 30 mg/m2 daily × 3 days) | |

| CAR‐T cell target dose | 2 × 106/kg; max dose was 2 × 108/kg | 0.1 × 108 to 6 × 108 flat dose | 0.5 × 108 to 1.5 × 108 each of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR‐T cells at 1:1 dose ratio | |

| CNS disease | No history of, or active, CNS disease allowed | No active CNS disease allowed | Secondary CNS allowed | |

| Prior anti‐CD19 therapy | Not allowed | Not allowed | Allowed, if CD19+ tumor present | |

| Bridging therapy | Not permitted | Permitted b | Permitted b | |

| Outpatient administration | Not allowed | Allowed | Allowed | |

| Patients enrolled, n | 119 | 167 | 344 | |

| Patients infused, n | 7 (phase 1) 101 (phase 2) | 99 (main cohort) 16 (Cohort A) | 294 c | |

| Manufacturing failure, n | 1 | 12 | 2 | |

Note: The purpose of this table is to summarize data. Head‐to‐head studies have not been performed and no comparisons can be made.

Abbreviations: CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CD, cluster of differentiation; CNS, central nervous system; US, United States.

In a subset of patients the lymphodepleting regimen was chosen by the investigator based on the patient's treatment history.

Bridging therapies for disease contol were chosen by the treating physican and based on the patient's disease and treatment history.

Twenty‐five patients received a nonconforming product that failed to meet specifications but was deemed safe to administer.

The axi‐cel CAR is transduced into cells via an immunocompetent gammaretrovirus, 15 whereas tisa‐cel and liso‐cel CARs are introduced into T cells using lentiviral vectors. 16 , 17 All three products have taken slightly different approaches to the specific types of white blood cells transduced by CAR‐carrying vectors after collection of white blood cells from patients via leukapheresis. Following leukapheresis, the axi‐cel CAR is transduced into freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), or, in some geographic regions for logistical reasons, into PBMCs thawed from a previously cryopreserved frozen leukapheresis sample. 15 Tisa‐cel manufacturing begins with a frozen leukapheresis sample, after which the vector is introduced into T cells selected from thawed PBMCs using CD3/CD28 coated magnetic beads. 3 Liso‐cel manufacturing includes separate transduction of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells isolated by immunomagnetic selection from a fresh leukapheresis sample. The final CD4+ and CD8+ liso‐cel cell products are infused separately at equal target doses of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR‐T cells (Table 1 2 , 4 , 6 , 10 , 11 ). 17

3. DESIGN OF KEY CLINICAL TRIALS

Note, ZUMA‐1 was the pivotal phase 1/2, US‐based and Israel‐based trial of axi‐cel for patients with r/r non‐Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL). Phase 1 enrolled seven patients and established the feasibility of manufacturing axi‐cel and its safe administration to patients, using the CAR construct developed at the National Cancer Institute. 18 , 19 These seven patients were followed by an additional two cohorts, totaling 101 patients aged 18 years or older in the pivotal phase 2 portion of ZUMA‐1. 5 Patients with DLBCL, HGBCL, tFL, or PMBCL who had primary refractory disease, disease refractory to second‐line or subsequent therapy, or relapsed within 1 year after autologous stem cell transplant (autoSCT) were eligible for enrollment. Patients with central nervous system (CNS) disease, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≥2, prior allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT), and prior anti–CD19‐directed therapy were excluded. Per protocol, enrollment and leukapheresis occurred after confirmation of the availability of a manufacturing slot. The median time from leukapheresis to delivery of axi‐cel to the treating facility was 17 days and the median time from leukapheresis to infusion was 28 days. 5 , 20 Bridging anti‐lymphoma therapy was not permitted during this interval. Axi‐cel was administered exclusively in an inpatient setting as a single infusion of the target dose of 2 × 106 anti‐CD19 CAR‐T cells/kg with a maximum dose of 2 × 108 cells in patients weighing >100 kg. 5

Note, JULIET was the pivotal, global, phase 2 trial that established the safety and efficacy of tisa‐cel in adult patients aged 18 years and older with r/r DLBCL, HGBCL, or tFL. 2 A total of 167 patients with aggressive NHL who had relapsed after or were resistant to at least two prior lines of therapy and either had relapsed after or were ineligible for autoSCT were enrolled; 115 of these patients received tisa‐cel. Patients with prior alloSCT, active CNS disease, prior treatment with an anti‐CD19 therapy, or an ECOG performance status ≥ 2 were excluded. 11 Leukapheresis was carried out at the treating center regardless of availability of a manufacturing slot. PBMCs were cryopreserved and stored locally, then shipped to the manufacturing facility when a manufacturing slot became available. Data supporting the feasibility of manufacturing CAR‐T cells from cryopreserved patient samples have been previously reported. 21 , 22 The average interval between enrollment and infusion of tisa‐cel was 54 days and patients could receive bridging anti‐lymphoma therapy for disease control during that time. In the JULIET trial, the ability to store cryopreserved apheresis products allowed leukapheresis any time after confirmation of eligibility, rather than after confirmation of an available manufacturing slot; thus, the interval from enrollment to tisa‐cel infusion, rather than the interval from leukapheresis to infusion, was reported. Over the course of the JULIET trial, as manufacturing capacity increased, the time from leukapheresis to manufacturing and, thus, from enrollment to tisa‐cel infusion improved. 22 Tisa‐cel could be infused on an outpatient basis at the treating physician's discretion. The efficacy‐evaluable cohort in JULIET included 99 patients who received tisa‐cel manufactured in the United States; an additional 16 patients (Cohort A) received tisa‐cel manufactured in Germany and were included in the safety analysis. 10

So, TRANSCEND‐NHL‐001 (TRANSCEND) was the pivotal phase 1 seamless design trial in the United States of liso‐cel in a total of 269 patients aged 18 years and older with DLBCL, tFL, PMBCL, HGBCL, FL3B, and other transformed indolent histologies who had relapsed or progressed after at least two prior lines of therapy with an ECOG performance status of 0–2. 6 A total of 344 patients underwent leukapheresis and 294 of these patients received liso‐cel. Patients with secondary CNS involvement by lymphoma were eligible for enrollment as long as systemic lymphoma was also present, prior alloSCT was permitted in the absence of graft‐versus‐host disease or ongoing immunosuppression if at least 90 days had passed from transplant to leukapheresis, and prior anti‐CD19 treatment was allowed if CD19 was still detectable on tumor cells. Bridging anti‐lymphoma therapy was allowed during product manufacturing. The median interval from leukapheresis to cell availability was 24 days. 6

4. PATIENT POPULATIONS: CLINICAL TRIALS

Patients enrolled in the three registrational CAR‐T cell clinical trials were heavily pre‐treated, relapsing after or refractory to a minimum of two prior lines of standard systemic therapy. Most patients were chemotherapy‐refractory and had either relapsed or were ineligible for autoSCT, primarily because of an insufficient response to salvage chemotherapy. 23

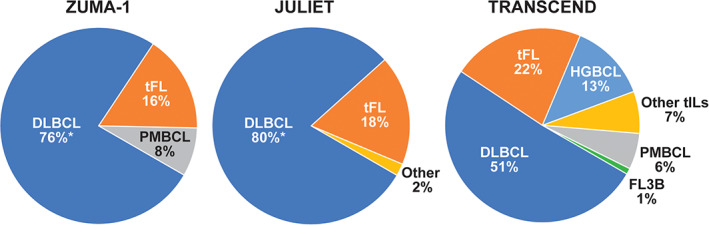

In addition to r/r DLBCL, all studies also included patients with HGBCL, with or without translocations of MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 (double/triple‐hit lymphoma), and tFL. Both ZUMA‐1 and TRANSCEND also included patients with r/r PMBCL. Only TRANSCEND included patients with transformed DLBCL arising from indolent histologies other than FL and FL3B (Figure 1 6 , 10 ). 5 , 11 , 12 So, TRANSCEND is also the only study that included patients with secondary CNS involvement or prior alloSCT.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of NHL subtypes in the ZUMA‐1, 5 JULIET, 10 and TRANSCEND 6 patient populations. DLBCL, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma; FL3B, follicular lymphoma grade 3B; HGBCL high‐grade B‐cell lymphoma; NHL, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma; PMBCL, primary mediastinal B‐cell lymphoma; tFL, transformed follicular lymphoma; tIL, transformed indolent lymphoma. *Includes patients with HGBCL [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Key baseline characteristics, including rates of high‐risk factors, for the populations enrolled in each trial are summarized in Table 2. 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 10 , 12 The median age of the 101 patients in phase 2 of ZUMA‐1 was 58 years (range, 23–76 years) and approximately one quarter were older than 65 years, 4 an age distribution significantly younger than the typical population of patients with DLBCL. 24 Patients in the JULIET trial (inclusive of the main cohort and Cohort A) had a median age of 56 years (range, 22–76 years) and, similar to ZUMA‐1, approximately one quarter were 65 years or older. 10 In the TRANSCEND study, the median age and range are closest to those of lymphoma patients in the general population—63 years (range, 18–86 years) with 42% older than 65 years (Table 2 2 , 4 , 5 , 10 , 12 ). 6

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of patients enrolled in key CAR‐T cell therapy clinical trials

| Patient characteristics | ZUMA‐1 4 , 5 (N = 101) a | JULIET 2 , 10 (N = 115) | TRANSCEND 6 , 12 (N = 269) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 58 (23–76) | 56 (22–76) | 63 (18–86) |

| Patients ≥65 years, % | 24 | 23 | 42 |

| HGBCL/double/triple hit, % | 6 | 17 | 13 |

| Stage III/IV, % | 85 | 76 | – |

| ECOG PS, % | |||

| 0–1 | 100 | 100 | 99 |

| 2+ | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Refractory to last line of therapy, % | 98 b , c | 55 | 67 c |

| Previous autoSCT, % | 21 | 49 | 33 |

| Previous lines of therapy, median (range) | 3 (IQR 2–4) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–8) |

| 1 line, % | 3 | 5 | – |

| 2 lines, % | 28 | 44 | – |

| ≥3 lines, % | 69 | 51 | – |

| ≥4 lines, % | – | 20 | 26 |

| Received bridging therapy, % | 0 | 90 | 59 |

Note: The purpose of this table is to summarize data. Head‐to‐head studies have not been performed and no comparisons can be made.

Abbreviations: autoSCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HGBCL, high grade B‐cell lymphoma; IQR, inter quartile range.

‐ refers to not reported.

Phase 2 cohort.

Refractory to second‐line or later; 2% were primary refractory.

Relapsed < 12 months after autoSCT.

In all three studies, most patients had one or more risk factors for poor survival. In ZUMA‐1, analysis of 47 pre‐treatment tumor samples identified 30 patients with double expressor B‐cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry and seven with HGBCL by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Prior to infusion, 85% had stage III/IV disease, 76% were refractory to second‐line or later therapy, and 21% had relapsed within 12 months of a prior autoSCT (patients who had undergone autoSCT were also eligible if they relapsed beyond 12 months but were refractory to subsequent therapy). 4 In JULIET, 19 of 70 patients with available samples (27%) had HGBCL (defined as double/triple‐hit lymphoma; patients with HGBCL without double/triple hit were recorded as DLBCL not otherwise specified), 76% of infused patients had stage III/IV disease, 55% were refractory to last therapy, and 49% had relapsed after a prior autoSCT. 2 In TRANSCEND, 67% of patients were refractory to their last chemotherapy, 44% had not previously achieved a complete response (CR) with any prior therapy, and 13% had HGBCL (double/triple hit). 6 In ZUMA‐1, most patients (69%) had received ≥ 3 prior lines of therapy (inter‐quartile range, 2–4). 4 In JULIET, over half of patients (51%) had more than three prior lines of therapy and 20% had received more than four (range, 1–6). 10 In TRANSCEND, patients had a median of three prior lines of therapy (range, 1–8) and 26% of patients had received at least four. 6 In JULIET, 90% of patients received bridging therapy, 10 compared with 59% in TRANSCEND. 6 The definitions of tumor burden and bulk varied across the three studies and cannot be easily compared; however, the majority of patients in each study did not meet the clinical definitions for bulky disease in their respective study.

5. EFFICACY AND SAFETY OF CAR‐T CELL THERAPIES: CLINICAL TRIALS

5.1. Efficacy outcomes

Patients with chemorefractory DLBCL treated with conventional therapies have a CR rate of 7%, a median overall survival (OS) of 6 months, and 1‐year OS rate of 28%, as illustrated by the retrospective SCHOLAR‐1 study. 23 The three CAR‐T pivotal trials recruited heavily pre‐treated patients, the majority of whom were chemorefractory (76% in ZUMA‐1, 55% in JULIET, and 67% in TRANSCEND). The overall response rates (ORR) ranged from 52% to 74% with 1‐year OS rates of 48% to 59% (Table 3 5 , 10 ), demonstrating that CAR‐T cell therapies have altered the natural history of chemorefractory DLBCL, in comparison with nonrandomized historical controls. 2 , 4 , 6 , 11

TABLE 3.

Time‐to‐event outcomes of patients in CAR‐T cell therapy clinical trials

| ZUMA‐1 4 (N = 101) | JULIET 2 , 10 , 11 (N = 115) | TRANSCEND 6 (N = 256) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median DOR, (95% CI) | NR (10.9‐NE) | NR (10.0‐NE) | NR (8.6‐NR) |

| DOR at month 12, % (95% CI) | – | 65 (49–78) | 54.7 (46.7–62.0) |

| DOR at month 24, % (95% CI) | – | – | 52.1 (43.6–49.8) |

| Median OS, months (95% CI) | NR (12.8‐NE) a | 11.1 (6.6–23.9) | 21.1 (13.3‐NR) |

| OS at month 12, % (95% CI) | 59 (49–68) 5 | 48.2 (38.6–57.1) | 57.9 (51.3–63.8) |

| OS at month 24, % (95% CI) | 50.5 (40.2–59.7) | 40.0 (30.7–49.1) | 44.9 (36.5–52.9) |

| Median PFS, months (95% CI) | 5.9 (3.3–15.0) a | NR | 6.8 (3.3–14.1) |

| PFS at month 12, % (95% CI) | 44 (34–53) 5 | – b | 44.1 (37.3–50.7) |

| PFS at month 24, % (95% CI) | – c | – | 42.1 (35.0–48.9) |

| Follow‐up, months | 27.1 | 32.6 | 12.0–17.5 d |

Note: The purpose of this table is to summarize data. Head‐to‐head studies have not been performed and no comparisons can be made.

Abbreviations: CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; DOR, duration of response; NE, not estimable; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival.

‐ refers to not reported or known values; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor.

Investigator assessed; all other data are based on assessment by independent review committee.

Among responders at 3 months the PFS at 12 months was 83% (95% CI, 74% to 96%).

Among responders at 3 months the PFS at 24 months was 72% (95% CI, 56%–83%).

Follow‐up 12.0 months for DOR, 12.3 months for PFS, and 17.5 months for OS.

In ZUMA‐1, which is the only pivotal CAR‐T clinical trial that enrolled a refractory population in which all patients met the SCHOLAR‐1 definition, the best ORR was 74% with 54% in CR; the reported median time to best response was 1 month. 4 Furthermore, 11 of 33 patients who achieved a partial response (PR) at month 1 eventually converted to a CR, with the majority of conversions taking place by month 6. 4 Response rates in ZUMA‐1 were consistent across key covariates. 4 , 5 At a median follow‐up of 27.1 months, 39 of 101 patients (39%) from phase 2 had ongoing responses; two patients underwent alloSCT while in remission and were censored. As assessed by investigator, the median duration of response (DOR) was 11.1 months, median OS was not reached, and the median progression‐free survival (PFS) was 5.9 months (Table 3). 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 25 No correlation was observed between age, disease stage, prior autoSCT, treatment history, infused CD4:CD8 ratio, use of tocilizumab or steroids, or DLBCL cell of origin and efficacy outcomes. However, high baseline tumor burden, high baseline pro‐inflammatory markers, and lower in vivo expansion of CAR‐T cells after adoptive transfer were associated with decreased and less durable responses. 5 , 26 , 27

The best ORR of patients in JULIET was 52%, with 40% of patients achieving CR. 2 Notably, just over half (15/28) of patients who had initially achieved a PR eventually converted to a CR without additional therapy. 10 Response rates in the main cohort were consistent across major demographic and prognostic subgroups. 2 , 10 At 32.6 months of follow‐up, the median DOR was not reached and median OS was 11.1 months (Table 3 4 , 5 , 6 , 10 , 11 ). 2 No correlation was observed between efficacy outcomes and baseline tumor volume, age, sex, baseline characteristics, prior lines of therapy, double/triple‐hit cytogenetics, or the ratio of infused CD4:CD8 CAR‐positive T cells. 2 , 28 , 29 , 30

Patients treated with liso‐cel in the TRANSCEND trial have the shortest follow‐up, with data reported at a median follow‐up of 18.8 months. 6 The best ORR was 73%, with a CR rate of 53% and, notably, ORR and CR rate were comparable across age and tumor histology subgroups. Among the 38% of patients with high disease burden (defined in this study as the sum of the product of diameters ≥50 cm 2 or LDH >500 U/L), there was a trend for lower ORR and CR rate compared with patients not meeting this definition of high disease burden. At 1 year of follow‐up, the median DOR was not reached. The median OS and PFS were 21.1 months and 6.8 months, respectively (Table 3 2 , 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 ). 6

Although efficacy outcomes in all three CAR‐T cell therapy trials are higher than results of historical conventional salvage treatments, there are several nuances inherent in CAR‐T cell therapies that should be considered when comparing clinical trial results. First, not all patients enrolled in CAR‐T cell therapy trials receive a CAR‐T cell product. In ZUMA‐1, 119 patients underwent leukapheresis and 108 (91%) received axi‐cel 4 ; in JULIET, 167 underwent leukapheresis and 115 (69%) received tisa‐cel 11 ; and in TRANSCEND, 344 patients underwent leukapheresis and 294 (85%) received liso‐cel. 6 This is mostly attributable to differences in timing with respect to enrollment and leukapheresis procedures specified by these protocols. Furthermore, CAR‐T cell therapy trials typically report efficacy for only those patients treated, similar to transplantation trials, rather than conventional chemotherapy and targeted therapy trials, which report the intent‐to‐treat population. The timing of therapy cannot be directly compared across these studies even in an intent‐to‐treat analysis, due to the differences in trial designs and patient populations. 31

5.2. Safety outcomes

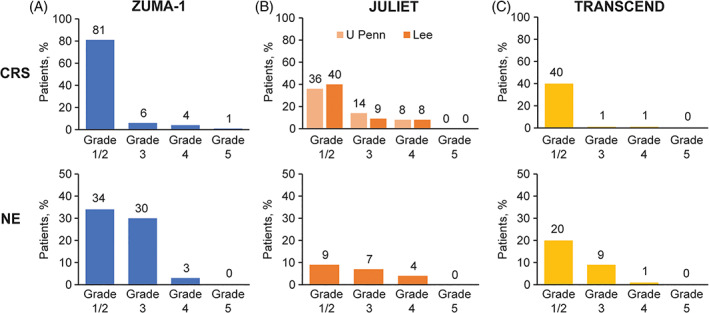

The CAR‐T cell therapies are associated with specific adverse events (AEs) that result from the on‐target action of therapy. Within days of CAR‐T cell infusion, cytokine release syndrome (CRS) can occur, hallmarked by fever, hypotension, and hypoxia. The median time to onset was 2 days following axi‐cel infusion, 3 days following tisa‐cel, and 5 days following liso‐cel. 5 , 12 , 32 The median time to resolution was 8, 7, and 5 days for the three therapies, respectively. 2 Although almost all cases of CRS are reversible, CRS can prompt or prolong a patient's hospital stay, including possible admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), and may require management with the anti–interleukin‐6 therapy tocilizumab, corticosteroids, and other supportive measures, including vasopressors, supplemental oxygen, and dialysis. During the development of the various CAR‐T cell therapies, several study groups established their own guidelines for defining and determining the severity of CRS, as well as suggested algorithms for management. The JULIET study utilized a grading scale and management guide developed by investigators at the University of Pennsylvania, 33 whereas the ZUMA‐1 and TRANSCEND trials used a version created by a consensus panel of experts organized by the National Cancer Institute and published by Lee et al. 34 Although the two systems are generally consistent, there are differences in grading of CRS. 35 More recently, a consensus guideline for immune effector cell therapy toxicity grading has been developed by the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) that is anticipated to become the preferred grading standard. 36 , 37

As shown in Figure 2, 4 , 6 , 10 , 35 overall rates of CRS reported in CAR‐T trials vary from 92% in ZUMA‐1 to 58% in JULIET and 42% in TRANSCEND. Rates of grade 3/4 CRS were 10%, 22%, and 2% in ZUMA‐1, JULIET, and TRANSCEND, respectively, although as stated above the grading scales used in ZUMA‐1 and TRANSCEND are not directly comparable with the grading system used in JULIET, which assigned more patients to the grade 3 CRS category relative to the Lee criteria. 2 , 4 , 6 , 35 To harmonize CRS reporting, patient‐level CRS data from the JULIET study were retroactively regraded using the Lee scale criteria. Regrading resulted in fewer patients designated as grade 3 (14% revised to 9%), more patients designated grade 1 or 2 (36% revised to 40%), and one patient declared as not having CRS at all. 35

FIGURE 2.

Rates of CRS and neurological AEs in CAR‐T cell therapy trials. (A), ZUMA‐1, 4 (B), JULIET [CRS is among 111 patients, 35 while NE is among 115 patients 10 ], (C), TRANSCEND. 6 AE, adverse event; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; NE, neurological events [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Neurological events (NE), now recognized as parts of a syndrome called immune effector cell‐associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), comprise the second unique AE that may occur soon after CAR‐T cell infusion. These NE can range from relatively mild confusion and aphasia to encephalopathy, status epilepticus, and rarely life‐threatening cerebral edema. The onset of ICANS is usually subsequent to the peak of CRS (median of 5 days following axi‐cel to 6 days after tisa‐cel and 9 days following liso‐cel), although the two syndromes frequently overlap. Similar to CRS, virtually all NE resolved (median of 17 days, 14 days, and 11 days following axi‐cel, tisa‐cel, and liso‐cel, respectively). 2 , 4 , 6 Neurological events were reported in 67% of patients in ZUMA‐1, in 21% of patients in JULIET, and in 30% of patients in TRANSCEND. In the three pivotal trials, the severity of NE was determined using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.03; most NE were grade 1 or 2 (Figure 2 4 , 6 , 10 , 35 ). Grade 3/4 NE occurred in 32%, 11%, and 10% of patients in ZUMA‐1, JULIET, and TRANSCEND, respectively. 4 , 6 , 10 Notably, newer and more specialized grading criteria for CAR‐T cell therapy‐associated NE are now available, such as the ASTCT consensus criteria for ICANS that is currently widely used for reporting NE in real‐world studies. 36 , 38

In ZUMA‐1, key AEs were managed with 43% of patients receiving at least one dose of tocilizumab and 27% requiring corticosteroids (Table 4 2 , 4 , 6 ). 5 Severe CRS and NE were more frequent in patients with high tumor volume, and the likelihood that patients experienced severe (grade ≥ 3) NE correlated with having received ≥ 5 prior lines of therapy. 26 Management of CRS and/or NE in the JULIET study included 14% of patients who received tocilizumab and 10% of patients receiving both tocilizumab and corticosteroids (Table 4 4 , 5 , 6 ). 2 High baseline LDH was a significant predictor for severe (grade 3 or 4) CRS. 28 Overall, 24% of patients were admitted to an ICU for care. In TRANSCEND, 20% of patients received tocilizumab (with or without steroids), 21% received corticosteroids (with or without tocilizumab), and 13% of patients received both for CRS and/or NE (Table 4 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). Tumor volume and LDH levels were higher in patients with any‐grade CRS or NE. Admission to an ICU was required due to CRS and neurological AEs for 4% of patients and for treatment of other events for 3% of patients. 6 Of note, tocilizumab (and steroid) administration was guided in the three studies using different criteria, partly based on the protocol‐specified grading system used for CRS.

TABLE 4.

Selected safety outcomes in trials of CD19‐targeted CAR‐T cell therapy in NHL

| ZUMA‐1 4 , 5 (N = 108) | JULIET 2 (N = 111) | TRANSCEND 6 (N = 269) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment of CRS and/or NE, % | |||

| Tocilizumab | 43 | 14 | 20 |

| Corticosteroids | 27 | 10 a | 21 |

| Admitted to intensive care unit | – | 24 | 4 |

| Prolonged cytopenias, b % | |||

| Any cytopenia (grade ≥ 3), ≥28 days | 38 | 32 | 37 |

| Neutropenia (grade ≥ 3), ≥28 days | 26 | 24 | 60 |

| Neutropenia (grade ≥ 3), ≥3 months | 11 | 0 | – |

| Anemia (grade ≥ 3), ≥28 days | 10 | – | 37 |

| Anemia (grade ≥ 3), ≥3 months | 3 | – | – |

| Thrombocytopenia (grade ≥ 3), ≥28 days | 24 | 41 | 27 |

| Thrombocytopenia (grade ≥ 3), ≥3 months | 7 | 38 | – |

| Infections (grade ≥ 3), % | 28 | 20 | 12 |

| Tumor lysis syndrome (grade ≥ 3), % | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia (grade ≥ 3), % | 0 | – | 0 |

| Treatment‐related mortality, % | 2 c | 0 | 1 d |

Note: The purpose of this table is to summarize data. Head‐to‐head studies have not been performed and no comparisons can be made.

Abbreviations: CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CD, cluster of differentiation; CRS, cytokine release cyndrome; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; NE, neurological events; NHL, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma.

− refers to not reported or known values.

Corticosteroids and tocilizumab.

Not resolved by study day 30 for ZUMA‐1, day 28 for JULIET, and day 29 for TRANSCEND.

One patient died with HLH and one patient died of cardiac arrest in the setting of CRS.

One patient died of diffuse alveolar damage that was related to liso‐cel treatment.

Normal B cells, like malignant B cells, are eliminated/destroyed by CAR‐T cells; therefore, B‐cell aplasia is an on‐target AE resulting from CAR‐T cell therapy. Several consequences can arise, including hypogammaglobulinemia and an increased risk of infection, which can potentially affect patients over the long term. In general, severe hypogammaglobulinemia caused by sustained B‐cell aplasia was uncommon in all three pivotal CAR‐T cell studies, and supplemental immunoglobulin therapy was administered at the treating physicians' discretion. Overall, 33 of 108 patients (31%) received supplemental immunoglobulin therapy, including 17 of the 39 patients with responses ongoing at the time of data cutoff in the ZUMA‐1 study. 4 Similarly, in the JULIET trial, 38 of 115 patients (33%) received supplemental immunoglobulin therapy (38% of responders vs 27% of nonresponders). 39 In the TRANSCEND trial, hypogammaglobulinemia (immunoglobulin G < 500 mg/dL) was reported as an AE in 14% of patients (all events grade 1 or 2), but immunoglobulin supplementation was administered to 21% of patients (Table 4 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). 12 Finally, in a long‐term follow‐up study of patients with r/r DLBCL and FL who were treated with tisa‐cel, within 2 years, 11 of 16 (69%) patients in CR for >1 year had B‐cell recovery. At 5 years, 11 of 16 patients (69%) had normal immunoglobulin M levels, nine of 16 (56%) had normal immunoglobulin A levels, and six of 16 (38%) had normal immunoglobulin G levels. Supplemental immunoglobulin therapy was started in six of 22 patients (27%) who had a response. 40 Notably, patients are often hypogammaglobulinemic even prior to CAR‐T cell therapy as a result of multiple prior lines of lymphoma‐directed treatments that also cause B‐cell depletion; thus, the contribution of CAR‐T cell therapy to hypogammaglobinemia observed in adult CAR‐T cell lymphoma studies is difficult to ascertain. Furthermore, it is difficult to reach conclusions regarding the benefit of immunoglobulin replacement therapy due to differences in institutional practices.

Prolonged cytopenias, defined as cytopenias not resolved within 1 month of infusion, have also been reported in a significant proportion of patients enrolled in the ZUMA‐1, JULIET, and TRANSCEND clinical trials. Prolonged cytopenias occurred in 55% of patients treated with axi‐cel in the ZUMA‐1 trial (38% grade ≥ 3). In particular, grade ≥ 3 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (26% and 24% at ≥ 30 days postinfusion) were still evident in 11% and 7% of patients, respectively, 3 months after infusion. 4 In the JULIET trial, grade 3 or 4 cytopenias lasting longer than 28 days postinfusion occurred in 32% of patients. At ≥ 28 days postinfusion, grade 3/4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were reported in 24% and 41% of patients, respectively. At 3 months after tisa‐cel infusion, grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia persisted in 38% of patients; no grade 3/4 neutropenia persisted in patients beyond month 3. 2 Prolonged grade 3 or 4 cytopenias (not resolved by 29 days after liso‐cel infusion) were reported in 37% of patients in TRANSCEND. 24 Additional data on resolution of cytopenias over time are not yet available for this trial. 6

The feasibility of outpatient delivery of CAR‐T cell therapy was demonstrated in both the JULIET and TRANSCEND trials. In JULIET, 27% of patients were infused in the outpatient setting. 8 An initial assessment of 69 patients treated with liso‐cel showed low rates of CRS and NE with outpatient delivery. 41 Of the first 114 patients treated in TRANSCEND, 18 received liso‐cel as outpatients; 11 of 18 (61%) were admitted to the hospital following outpatient administration. Outpatient infusion of liso‐cel was associated with a 68% decrease in hospital length of stay compared with inpatient administration and did not result in greater utilization of or need for tocilizumab, intubation, or dialysis. 42

6. REAL‐WORLD EVIDENCE

Following their approvals in 2017 and 2018, axi‐cel and tisa‐cel moved rapidly into clinical practice. By the end of 2019, about 1800 people had received tisa‐cel (including children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic lymphoma). 43 At present, CAR‐T cell therapy is available only at specialized centers that are trained to administer axi‐cel or tisa‐cel; liso‐cel is very recently commercially available. Evidence from real‐world administration of CAR‐T cell therapies addresses several important questions, primarily which patients can or should be referred for CAR‐T cells, how manufacturing processes compare with those reported in clinical trials, and how efficacious and safe these products are in a real‐world setting.

6.1. Characteristics of patients treated with CAR‐T cells in the real‐world setting

Patient selection for CAR‐T cell therapy in the real world is based on the product prescribing information and clinical experience. Clinical trial inclusion criteria are very specific with respect to life expectancy, performance status, organ function, and exclusion of certain prior therapies; however, axi‐cel and tisa‐cel prescribing information provide only general guidance for patient selection that may allow treatment of less fit patients than patients enrolled in clinical trials. In brief, the prescribing information indicates that patients considered for CAR‐T cell therapy should have r/r disease that is not rapidly progressing to allow time for leukapheresis, manufacturing, and infusion of the CAR‐T cells. Patients should not have an active, uncontrolled infection, or a diagnosis of primary CNS lymphoma. Finally, it is recommended that patients have adequate renal, hepatic, pulmonary, and cardiac function (although the exact parameters vary slightly between products).

Several retrospective studies have reported on the use of axi‐cel and tisa‐cel as standards of care. The US Lymphoma CAR T Consortium reported results from a retrospective analysis of axi‐cel administration at 17 centers in the United States that involved a total of 298 patients. 44 Jacobson et al. reported on 122 patients treated with axi‐cel at seven academic medical centers across the United States. 45 Riedell et al. reported on 158 patients treated with axi‐cel and 86 treated with tisa‐cel at eight academic medical centers in the United States. 20 In addition, real‐world data obtained from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database was analyzed from 533 patients treated with axi‐cel and 155 patients treated with tisa‐cel, respectively (Table 5 20 , 44 , 48 ). 46 , 47

TABLE 5.

Characteristics of patients who have received commercial CAR‐T cells in the real world [Correction added on August 27, 2021, after first online publication: In the heading of Table 5, the horizontal bars under Axicabtagene ciloleucel and Tisagenlecleucel were corrected in this version.]

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | Tisagenlecleucel | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nastoupil et al. 44 (N = 298) | Pasquini et al. 46 CIBMTR (N = 533) | Riedell et al. 20 (N = 158) | Riedell et al. 20 (N = 86) | Pasquini et al. 47 CIBMTR (N = 155) | |

| Histology, % | |||||

| DLBCL | 68 | – | 87 | 95 | – |

| tFL | 26 | 30 | – | – | 27 |

| PMBCL | 6 | – | – | – | – |

| Other | 0 | – | 13 | 5 | – |

| Median age, years (range) | 60 (21–83) | 61 (19–86) | 59 (18–85) | 67 (29–88) | 65 (18–89) |

| Patients ≥65 years, % | 52 a | 37 | 34 | 62 | 53 |

| HGBCL/double/triple hit, % | 23 b | 36 | – | – | 11 |

| Refractory/resistant to last line of therapy, % | 42 | 62 | 55 | 82 | – |

| ECOG PS, % | |||||

| 0–1 | 80 | 80 | 90 | 95 | 83 |

| 2+ | 19 | 4 | – | – | 5 |

| Previous autoSCT, % | 33 | 32 | 27 | 26 | 26 |

| Previous lines of therapy, median (range) | 3 (2–11) | – | 3 (2–10) | 4 (2–9) | 4 (0–11) |

| ≥3, % | 75 | 66 c | 73 | 86 | – |

| Received bridging therapy, % | 53 d | – | 61 | 75 | – |

| Patients who underwent leukapheresis, n | 298 | – | 170 | 94 | – |

| Patients who received CAR‐T cells, n (%) | 275 (92) | 750 | 158 (93) | 86 (91) | 155 |

Note: The purpose of this table is to summarize data. Head‐to‐head studies have not been performed and no comparisons can be made.

Abbreviations: autoSCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CIBMTR, Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research; DLBCL, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HGBCL, high‐grade B‐cell lymphoma; PMBCL, primary mediastinal B‐cell lymphoma; tFL, transformed follicular lymphoma.

‐ refers to not reported or known values.

Patients ≥60 years.

Double/triple hit.

>3 prior lines of therapy.

Bridging therapies included chemotherapy (54%), steroids only (23%), radiation therapy (12%), and targeted regimens (10%).

Similar to ZUMA‐1 and JULIET, the majority of real‐world CAR‐T cell therapy patients had DLBCL and a smaller proportion of patients had tFL, PMBCL, or other lymphomas. In general, patients treated with commercial products were older than those in the clinical trials; strikingly, more than half of patients treated with tisa‐cel were over 65 years of age, whereas only one third of patients treated with axi‐cel in the real world were over 65. There were also more patients in the real‐world studies with ECOG performance status ≥ 2 (per protocol, ZUMA‐1 and JULIET only enrolled patients with ECOG performance status of 0–1). There were also more patients in the CIBMTR database with double/triple‐hit lymphomas than in ZUMA‐1. 2 , 4 , 20 , 46 , 47 Finally, just over half of patients treated with axi‐cel in the real world received bridging chemotherapy, which was not permitted in ZUMA‐1. 4 , 20 Nastoupil et al. noted that 43% of patients treated in the retrospective study would have been ineligible for ZUMA‐1 based on comorbidities at the time of apheresis, whereas 62% reported by Jacobson et al. would have been ineligible for ZUMA‐1. 44 , 49

The effect of bridging therapy on outcomes remains complex and unclear. On one hand, it has been suggested that the increased use of bridging therapy may improve disease control prior to CAR‐T cell infusion, providing a response benefit and decreased severe toxicity. The typical patient with aggressive lymphoma being considered for CAR‐T cell therapy has at least some degree of chemotherapy resistance, which is a factor when considering bridging therapy. However, novel agents have promising results that may translate into improved treatment eligibility for CAR‐T cell therapy. With the increasing number of targeted therapies available for this patient population, such as polatuzumab vedotin and loncastuximab tesirine, and the availability of radiation therapy as an option for bridging therapy in patients with localized disease or a dominant lesion, treating physicians may have more options to consider when selecting a drug for bridging therapy. Conversely, the analyses by Jain et al. suggest that patients who receive bridging therapy may have inferior outcomes compared with patients who do not receive bridging therapy prior to axi‐cel infusion. 50 One likely explanation is that the type of patients who require bridging at the discretion of their treating physician have bulkier, more rapidly progressive, or symptomatic disease compared with patients with lower tumor burden, who can safely forgo disease control via bridging therapy while their CAR‐T cell products are being manufactured. Another possibility that requires further investigation is whether bridging therapy itself confers additional treatment toxicity or immunosuppression. For example, Pinnix et al. reported that patients bridged with radiation therapy had a longer median PFS than patients bridged with systemic therapy. 51

6.2. Manufacturing CAR‐T cells for patients in the real world

For patients treated with axi‐cel, leukapheresis material is provided to a manufacturing facility in the United States or the Netherlands where the final product is prepared; patients prescribed tisa‐cel can receive a product manufactured in the United States, France, Switzerland, or Germany. Although the number of patients who underwent leukapheresis is not available from CIBMTR for either product, the proportion of patients who underwent leukapheresis and received either axi‐cel or tisa‐cel in three other real‐world studies ranged from 90% to 93%. 20 , 44 , 49 Nastoupil, Jacobson, and Riedell reported 275 of 298 (92%), 122 of 135 (90%), and 158 of 170 (93%) leukapheresed patients, respectively, received axi‐cel. 20 , 44 , 49 In the tisa‐cel cohort, Riedell et al. reported that 86 of 94 (91%) leukapheresed patients received CAR‐T cell product. 20 Nastoupil et al. reported that seven products did not meet manufacturing specifications (2.3%) in their cohort 44 ; Jacobson et al. reported three manufacturing failures out of 135 patient samples (2.2%). 49 Finally, the median time from leukapheresis to the start of conditioning therapy was 21 days in the Nastoupil et al. cohort receiving axi‐cel. 44 Riedell et al. reported that the vein‐to‐vein time from leukapheresis to infusion was 28 days for patients receiving axi‐cel and 44 days for patients receiving tisa‐cel. 20 The 155‐patient cohort analyzed by Pasquini et al. had a median interval of 32 days from the start of leukapheresis acceptance to infusion of tisa‐cel (the start of manufacture could be of variable length of time after leukapheresis). 47 Of 47 out‐of‐specification (OOS) tisa‐cel products, 43 (91%) reported by the CIBMTR occurred due to low viability; this viability threshold only applies to the United States and is higher than in the other countries in which tisa‐cel is approved. Low or high cell count (n = 3) and low or high interferon‐gamma release (n = 2) were the reasons for the additional products being OOS. 47 Continuous process improvements in manufacturing has resulted in a consistent and optimized process for tisa‐cel. 22 Taken together, these early reports indicate that both axi‐cel and tisa‐cel are successfully manufactured and delivered to the majority of patients in the real‐world setting.

6.3. Efficacy and safety of CAR‐T cell therapy in the real‐world setting

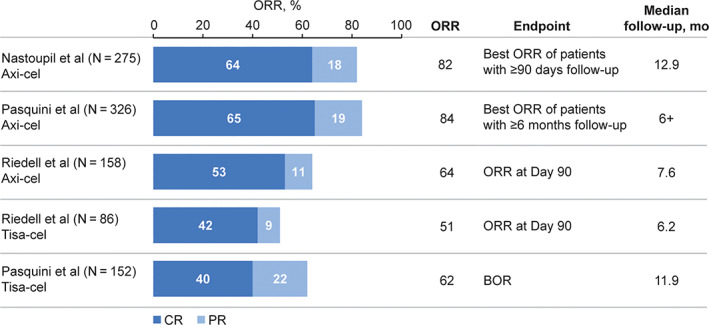

In the three real‐world studies of axi‐cel shown in Table 5, ORRs reported by Jacobson et al., Nastoupil et al., and Riedell et al. were 70% (best overall response [BOR]), 82% (BOR), and 64% (assessed at 90 days), respectively, 20 , 44 , 49 and 84% reported by Pasquini et al. in patients with 6 months of follow‐up (Figure 3 20 , 44 , 47 ). 46 These data are remarkably similar to outcomes from ZUMA‐1, which reported an ORR of 83% as BOR. 4 With additional follow‐up (median 13.8 months), the median PFS in the Nastoupil cohort was 7.2 months; median OS has not been reached. 44

FIGURE 3.

ORR of patients receiving commercially available CAR‐T cell therapy. 20 , 44 , 46 , 47 BOR, best overall response; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CR, complete response; ORR, objective response rate; PR, partial response [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Two studies reported real‐world efficacy outcomes for tisa‐cel. Riedell et al. and Pasquini et al. report very similar ORRs—51% (at 90 days) and 62% (BOR), respectively, 20 , 47 which are comparable with the ORR reported in the JULIET study (52% [BOR], Figure 3 20 , 44 , 46 , 47 ). 11 In addition, the data show that ORRs are comparable between patients with in‐specification product (≥80% viable CAR‐T cells) and those with OOS products (<80% viable CAR‐T cells), at 65% and 52%, respectively. Finally, Pasquini et al. reported that the PFS and OS in the CIBMTR cohort at 6 months were 39% and 71%, respectively. 47

In real‐world studies of commercially available CAR‐T cells, 82% to 91% of patients who received axi‐cel had CRS reported; rates of grade ≥ 3 CRS ranged from 7% to 9% (Table 6 20 , 34 , 37 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 52 , 53 ). These rates are generally similar to what was observed in ZUMA‐1 (Figure 2 4 , 6 , 10 , 35 ). Likewise, rates of any‐grade (53%–69%) and grade ≥ 3 (19%–33%) NE are generally comparable with ZUMA‐1. 4 , 20 , 44 , 46 However, notably higher rates of tocilizumab (61%–62% of patients) and steroid use (53%–54%) were reported in the real‐world studies, probably reflecting evolving management strategies rather than increased toxicity. Any‐grade CRS and NE occurred in 41% to 45% and 14% to 18% of patients, respectively, who received commercial tisa‐cel; the majority of events were grade 1 or 2. Overall, rates of CRS and NE with tisa‐cel are lower in reports from studies in a real‐world setting than in JULIET. Rates of tocilizumab and corticosteroid use were generally similar to JULIET, whereas ICU admissions appear to be lower in the real‐world studies than in the JULIET trial (Table 6 34 , 37 , 44 , 46 , 52 , 53 ). 2 , 20 , 47

TABLE 6.

Safety of commercial CAR‐T cell therapy in the real‐world setting [Correction added on August 27, 2021, after first online publication: In the heading of Table 6, the horizontal bars under Axicabtagene ciloleucel and Tisagenlecleucel were corrected in this version.]

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | Tisagenlecleucel | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nastoupil et al. 44 (N = 275) | Pasquini et al. 46 CIBMTR (N = 533) | Riedell et al. 20 (N = 158) | Riedell et al. 20 (N = 86) | Pasquini et al. 47 CIBMTR (N = 155) | |

| Any‐grade CRS, % | 91 a | ~82 a | 85 b | 41 b | 45 b |

| Grade ≥ 3 CRS | 7 | ~9 | 8 | 1 | 5 |

| Any‐grade neurological AEs, % | 69 c | 58 d | 53 e | 14 e | 18 d |

| Grade ≥ 3 neurological AEs | 31 | ~19 | 33 | 0 | 5 |

| Tocilizumab, % | 62 | – | 61 | 15 | 19 |

| Corticosteroids, % | 54 | – | 53 f | 8 f | 5 |

| Admitted to ICU, % | 33 | – | 39 | 7 | – |

| Treatment‐related mortality, n (%) | 2 (1) | 12 (2) | – | – | – |

Note: The purpose of this table is to summarize data. Head‐to‐head studies have not been performed and no comparisons can be made.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; ASTCT, American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CARTOX, CAR T cell‐therapy‐associated TOXicity; CIBMTR; Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; ICANS, immune‐effector cell associated encephalopathy‐associated neurotoxicity syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit.

‐ refers to not reported or known values.

Graded using the Lee criteria. 34

Graded using the ASTCT scale.

Graded using ICANS. 37

Graded according to CARTOX, ASTCT, and CTCAE.

Steroid use.

The multicenter study reported by Riedell et al. and a single‐center study presented by Denlinger et al. both addressed the issue of resource utilization with axi‐cel and tisa‐cel administration. Axi‐cel was administered outpatient to 8% and 16% of patients in the Riedell and Denlinger cohorts, respectively, compared with 64% and 22% of patients treated with tisa‐cel. 20 , 54 In addition to the lower rates of use of tocilizumab and corticosteroids with tisa‐cel, tisa‐cel was also associated with lower rates of ICU admission and fewer days in the hospital overall than axi‐cel. 20 Both studies concluded that axi‐cel is associated with higher overall resource utilization. 20 , 54

Although limited by short follow‐up, these real‐world studies demonstrate at least similar efficacy and safety profiles for CAR‐T cell therapy compared with the outcomes observed in ZUMA‐1 and JULIET. 2 , 4 , 20 , 44 , 46 , 47 It should be noted that these real‐world studies were conducted exclusively in the United States, whereas limited real‐world data for CAR‐T cell therapy are available from studies conducted in Europe. Findings from 61 patients treated with either axi‐cel or tisa‐cel in a single European center reported an ORR of 45% (at 3 months); 8% and 10% of patients experienced grade ≥ 3 CRS and ICANS, respectively. No significant differences were found between axi‐cel and tisa‐cel for efficacy and safety. 55

These results are encouraging and additional real‐world studies and longer follow‐up are needed to better determine which patients may benefit most from each CAR‐T cell product.

7. POSTINFUSION PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Since the first patients were treated with CAR‐T cells in 2010, there are now hundreds of patients who have survived years after CAR‐T cell therapy, and more are joining their ranks every year. Monitoring remission status and managing long‐term AEs of CAR‐T cell therapy are important ongoing goals of postinfusion patient management.

7.1. Markers of sustained response

The CAR‐T cells can persist for weeks to months—and in some cases years—after infusion. 2 , 56 Thus, CAR‐T cell persistence and expansion have been proposed as potentially informative markers for efficacy or safety outcomes and continue to be heavily investigated.

Axi‐cel expansion in the first 28 days, but not transgene persistence, was associated with ongoing response in ZUMA‐1. By month 24, 11 of 32 (34%) assessable patients no longer had detectable transgene. 4 In the JULIET study, neither the rate of CAR‐T cell expansion nor the maximum expansion correlated with response. Tisa‐cel transgene has been detected for more than 2 years in responding patients. The presence of the transgene is not, however, essential for ongoing response as several patients lost detectable transgene but maintained remission. 2 , 3 Similar to tisa‐cel, liso‐cel demonstrated long‐term persistence with detectable transgene found in over half of patients 1 year after infusion. 6 It is interesting to note that the differences in cellular kinetics between the CARs may be attributable to the use of CD28 vs 4‐1BB co‐stimulatory domains. 13 Regardless of the pharmacodynamics, some degree of CAR‐T cell expansion is needed for a durable response, although CAR‐T cell efficacy in lymphoma does not appear to be dependent upon a specific level of expansion or duration of CAR transgene persistence and these parameters may vary between products. Monitoring of CAR‐T cells beyond 1 month is therefore unlikely to be a useful strategy to monitor ongoing response, although additional data are needed to support this conclusion.

Because B‐cell aplasia is an on‐target effect of anti‐CD19 CAR‐T cells, monitoring of B‐cell recovery has been investigated as a marker of ongoing efficacy. Similar to CAR transgene levels, however, B‐cell aplasia appears to be highly variable and not closely related to ongoing response in patients with B‐cell lymphoma. In ZUMA‐1, 20 of 33 assessable patients (61%) had regained detectable B cells by 9 months postinfusion; by 24 months, 24 of 32 patients (75%) had regained B cells while remaining in ongoing remission. 4 In JULIET, six of 48 responding patients (13%) regained normal B‐cell levels (one patient within 3 months and five patients >6 months postinfusion). 11 Finally, Logue et al. reported undetectable B cells in 30 of 34 patients (88%) in their retrospective cohort by Day 30, with 11 of 19 patients (58%) regaining detectable B cells by 1 year post axi‐cel infusion. 57

7.2. Management of long‐term adverse events following CAR‐T cell therapy

Patients who have received CAR‐T cell therapy have unique long‐term health considerations in addition to those common to all lymphoma patients who have been treated with multiple therapeutic regimens. Management of the long‐term consequences of CAR‐T cell therapy include monitoring and treating the sequelae of B‐cell aplasia that can include hypogammaglobulinemia, increased risk of infections, and the potential for reactivation of latent viruses. 7 , 8 , 57 Patients may also have prolonged CD4 T‐cell lymphopenia and remain at risk for opportunistic infections, warranting consideration of prophylaxis. 57 In addition, prolonged neutropenia and thrombocytopenia may impact infection and bleeding risks.

Finally, treatment with multiple chemotherapy drugs is a risk factor for secondary malignancies, and most CAR‐T cell‐treated patients have received multiple lines of therapy. Chong et al. reported secondary cancers in six of 38 patients (16%) with 5 years of follow‐up in the University of Pennsylvania CTL019 study. 40 Four cases (<1%) of myelodysplastic syndrome were reported in the CIBMTR cohort of axi‐cel treated patients and one case in the phase 1 study of ZUMA‐1. 18 , 46 Additionally, CAR‐T cell therapy patients have a theoretical risk of malignancies arising from the portions of the CAR transgenes derived from viruses. Of note, no cases of insertional mutagenesis have been reported in DLBCL patients treated with either axi‐cel or tisa‐cel as of the most recent data cuts. 4 , 11 To track the rate of malignancies, the CIBMTR and European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) have established registries to follow patients receiving various gene and cell therapies for up to 15 years.

7.3. Ongoing trials of CD19 CAR‐T cell therapies in DLBCL and aggressive B‐cell lymphomas

With the results of the ZUMA‐1, JULIET, and TRANSCEND trials, the number of additional studies of CD19 CAR‐T cell therapies has increased. In general, there are three directions for these ongoing studies. First, there are several ongoing and planned clinical trials of CAR‐T cells in patients with r/r DLBCL focused on improving outcomes in the third‐line patient population through combination regimens. These include ZUMA‐6 (NCT02926833), a study of axi‐cel in combination with atezolizumab; PORTIA (NCT03630159), a study of tisa‐cel plus pembrolizumab; NCT03876028, a study of tisa‐cel plus ibrutinib; and PLATFORM (NCT03310619), a trial of liso‐cel in combination with durvalumab or ibrutinib. Next, a group of studies is investigating CAR‐T cells in other patient populations. ZUMA‐12 (NCT03761056) is studying axi‐cel in high‐risk patients with suboptimal interim response to first‐line therapy, BIANCA (NCT03610724) is investigating tisa‐cel in children and young adults with B‐cell NHL, and TRANSCEND WORLD (NCT03484702) is investigating liso‐cel in adults with B‐cell NHL including patients with primary CNS involvement. In addition, ELARA (NCT03568461), ZUMA‐5 (NCT03105336), and TRANSCEND FL (NCT04245839) are investigating efficacy and safety of tisa‐cel, axi‐cel, and liso‐cel, respectively, in patients with r/r FL (grades 1‐3a). TARMAC (NCT04234061) and TRANSCEND are investigating the efficacy and safety of tisa‐cel and liso‐cel in r/r mantle cell lymphoma, respectively, and TRANSCEND‐CLL‐044 (NCT03331198) is investigating the efficacy and safety of liso‐cel in r/r chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. ZUMA‐2 (NCT02601313) led to the approval of brexucabtagene autoleucel in patients with r/r mantle cell lymphoma. A third approach involves randomized, phase 3 trials vs standard‐of‐care salvage chemotherapy followed by high‐dose chemotherapy and autoSCT in responding patients to front‐line therapy. These include ZUMA‐7 (NCT03391466), a randomized phase 3 trial of axi‐cel versus standard of care; BELINDA (NCT03570892), a randomized phase 3 trial of tisa‐cel vs standard of care; and TRANSFORM (NCT03575351), a randomized phase 3 trial of liso‐cel vs standard of care (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Clinical trials of CAR‐T cell therapy in aggressive B‐cell lymphomas

| Trial Name (NCT number) | Phase | Indication | Treatment | Key Endpoints | Line of Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BELINDA (NCT03570892) | 3 | Adult B‐cell NHL | Tisa‐cel vs standard of care a | EFS, OS, ORR, DOR, QoL | 2nd |

| TRANSFORM (NCT03575351) | 3 | Adult r/r B‐cell NHL | Liso‐cel vs standard of care b | EFS, CRR, PFS, OS, ORR, DOR, QoL, AEs | 2nd |

| ZUMA‐7 (NCT03391466) | 3 | Adult r/r DLBCL | Axi‐cel vs standard of care c | EFS, ORR, OS, mEFS, PFS, DOR, QoL, safety | 2nd |

| TRANSCEND WORLD (NCT03484702) | 2 | Adult aggressive B‐cell NHL | Liso‐cel | ORR, AEs, CRR, EFS, PFS, OS, DOR, QoL, pharmacokinetics | ≥2nd |

| ZUMA‐12 (NCT03761056) | 2 | Adult high‐risk LBCL | Axi‐cel | CR, ORR, DOR, EFS, PFS, OS, safety | 1st |

| PORTIA (NCT03630159) | 1b | Adult r/r DLBCL | Tisa‐cel + pembrolizumab | ORR, DOR, PFS, OS, cellular kinetics | ≥3rd |

| NCT03876028 | 1b | Adult r/r DLBCL | Tisa‐cel + ibrutinib | Safety, ORR, DOR, PFS, OS, cellular kinetics | ≥3rd |

| PLATFORM (NCT03310619) | 1/2 | Adult r/r B‐cell NHL | Liso‐cel + durvalumab or CC‐122 | OS, ORR, DOR, CRR, AEs, PFS, QoL | ≥3rd |

| ZUMA‐6 (NCT02926833) | 1/2 | Adult r/r DLBCL | Axi‐cel + atezolizumab | CRR, ORR, DOR, PFS, OS, AEs | ≥3rd |

| BIANCA (NCT03610724) | 2 | Pediatric and young adult B‐cell NHL | Tisa‐cel | ORR, DOR, EFS, RFS, PFS, OS, cellular kinetics | ≥2nd |

| ELARA (NCT03568461) | 2 | Adults with r/r FL (grades 1, 2, or 3a) | Tisa‐cel | CR, ORR, OS, cellular kinetics, safety, PRO | ≥2nd |

| TRANSCEND FL (NCT04245839) | 2 | Adult r/r FL (grades 1, 2, or 3a) or MZL | Liso‐cel | CR, ORR, DOR, PFS, OS, safety, pharmacokinetics, QoL | ≥2nd |

| ZUMA‐5 (NCT03105336) | 2 | Adults with r/r FL (grades 1, 2, or 3a) or MZL | Axi‐cel | ORR, safety, DOR, PFS, OS | ≥3rd |

| TARMAC (NCT04234061) | 2 | Adults with r/r MCL | Tisa‐cel + ibrutinib | CR, OR, safety, DOR, PFS, OS | ≥2nd |

| ZUMA‐2 (NCT02601313) | 2 | Adults with r/r MCL | Brexucabtagene autoleucel | OR, DOR, BOR, PFS, OS, safety, pharmacokinetics, QoL | ≥3rd |

| NCT03331198 | 1/2 | Adults with r/r CLL or SLL | Liso‐cel ± ibrutinib | CR, safety, ORR, PFS, OS, QoL | ≥3rd d |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; axi‐cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; BOR, best objective response; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CR, complete response; CRR, complete response rate; DLBCL, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma; DOR, duration of response; EFS, event‐free survival; FL, follicular lymphoma; LBCL, large B‐cell lymphoma; liso‐cel, lisocabtagene maraleucel; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; mEFS, modified event‐free survival; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; NHL, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma; OR, objective response; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; PRO, patient‐reported outcomes; QoL, quality of life; r/r, relapsed or refractory; RFS, relapse‐free survival; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; tisa‐cel, tisagenlecleucel.

Patients will receive investigator's choice of platinum‐based immunochemotherapy followed in responding patients by high‐dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Salvage therapy per physician's choice before proceeding to high‐dose chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Platinum‐containing salvage chemotherapy followed by high‐dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant in responders.

Patients in the liso‐cel cohort only.

8. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Collectively ZUMA‐1, JULIET, and TRANSCEND demonstrate the feasibility of manufacturing and delivering a “living drug” to patients. The efficacy and safety results with axi‐cel, tisa‐cel, and liso‐cel confirm the utility of CAR‐T cells as a therapeutic option for many patients with r/r aggressive B‐cell lymphomas. There are nearly 6 years of efficacy and safety data for CAR‐T cell therapy in more than 500 patients with r/r B‐cell NHLs. 3 , 40 , 58 This collective experience—and the consistency of the range of AEs across trials—has served to define a safety profile of CAR‐T cell therapy and is aiding in the development of consensus grading and management tools. These important factors are supporting the successful implementation of CAR‐T cell therapy into clinical practice.

The three trials enrolled patients with somewhat different histologies as described previously in this review (Figure 1). Additionally, the timing between apheresis and cell infusion, the use of bridging therapy, and the lymphodepleting regimens utilized varied across studies. These dissimilarities pose a challenge in performing direct comparisons of the three trials. Nevertheless, these comparisons provide the highest level of evidence currently available in the absence of prospective head‐to‐head studies, which are unlikely to occur. We believe that the second‐line therapy randomized trials of standard chemotherapy and transplant vs CAR‐T cell therapy will have enough similarities to facilitate more confident comparisons.

Another area for consideration is the method and timing of response assessments. It appears that response at month 1 is not as predictive of long‐term benefit as responses at months 3 and 6. Additionally, the timing of conversion from PR or stable disease to CR may be related to the method used to define and follow response, as different imaging modalities (eg, computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography) may be used for response assessment at different protocol‐specified timepoints.

The different imaging modalities and timing used to evaluate the response of each patient have resulted in primary endpoints that were nonconventional relative to those used with trials evaluating new therapeutic agents in lymphoma; however, nonconventional endpoints were essential due to the nature of these “living drugs.” Criteria used to measure objective response also varied among the three trials, with ZUMA‐1 using the International Working Group response criteria for malignant lymphoma and the TRANSCEND and JULIET trials both using the Lugano criteria. These factors resulted in nonstandard endpoints, thereby limiting comparison across trials.

With real‐world CAR‐T cell therapy data becoming available for axi‐cel and tisa‐cel, several important insights are emerging. Axi‐cel has a higher degree of toxicity and requires inpatient administration, but also appears to have the quickest turnaround time (less than 3 weeks). Tisa‐cel tends to be favored in older adults due to the lesser toxicity and may be administered in the outpatient setting but has a manufacturing turnaround time of approximately 1 month. Furthermore, the threshold for intervention with tocilizumab and/or steroids in the real world appears lower than in ZUMA‐1 or JULIET, which may be contributing to lower rates of grade 3/4 CRS and NE in real‐world settings compared with clinical trials. Finally, the use of bridging therapy prior to axi‐cel infusion in the real‐world setting seems to be associated with decreased efficacy, although this may be a result of higher risk patients being treated in the real world. 44 Additional investigation is needed to determine whether this is indeed associated with selection bias, as more aggressive disease biology may necessitate bridging, or whether the bridging therapy itself actively impacts outcomes.

The cost of CAR‐T cell therapy has been extensively reported. 59 , 60 Based on previous studies, the cost per quality‐adjusted life year of axi‐cel and tisa‐cel for large B‐cell lymphoma therapy in the United States is below the willingness‐to‐pay threshold in cancer treatment. 61 , 62 , 63 Cost‐effectiveness studies for liso‐cel and CAR‐T cell therapy in other countries are not yet available. A substantial amount of the costs incurred from CAR‐T cell therapy is attributed to hospitalization and office visits. 64 Improving therapies in the outpatient setting may reduce costs and therefore allow additional patients to be treated. Expanding outpatient administration to nonacademic specialty oncology networks may decrease travel expenses for some patients and alleviate inpatient hospital capacity. 64

Aside from CAR‐T cell therapy, other novel immunotherapies are currently being investigated. Antibody‐drug conjugates are therapies that direct the delivery of highly cytotoxic compounds to lymphoma cells to decrease systemic toxicity. 65 Bispecific antibodies are also being evaluated in r/r NHL; these antibodies mediate cell death by one receptor targeting one antigen at the surface of malignant cell and another activating immune cells, allowing those cells to exert their cytotoxic potential. 66

Several limitations are evident when considering the use of alloSCT for treatment of patients with DLBCL. First, fewer than 20% of patients who relapsed after autoSCT can undergo alloSCT. Additionally, treatment with alloSCT as consolidation therapy typically necessitates a prior response to salvage chemotherapy. Lastly, many patients are not eligible due to poor response, older age, comorbidities, or absence of a donor; hence, a novel treatment approach, such as CAR‐T cell therapy, is needed to address the chemorefractory and ineligible fraction of patients with r/r DLBCL. 4

The next hurdle in the field is addressing the long‐term needs of patients treated with CAR‐T cell therapy. Because of the unique nature of CAR‐T cells, monitoring ongoing responses and assessing the risk of relapse are novel challenges. Cellular pharmacokinetic data thus far suggest that the structural aspects of the CAR products (co‐stimulatory domains in particular) may influence aspects of cell kinetics, transgene persistence, and B‐cell aplasia. However, more research is needed to determine whether any of these attributes is clinically relevant for patient monitoring. Early reports of utilizing circulating tumor DNA as a marker of minimal residual disease detection highlight a new approach that shows promise for identifying patients at risk of relapse. 67 Immune dysregulation was found to be a major factor in CAR‐T cell therapy failure. A recent study found that patients with poor response to treatment had a significant amount of gene expression for tumor interferon signaling as compared to responders. Elevated interferon signaling was associated with increased expression of T‐cell inhibiting binders such as programmed death‐ligand 1. An interferon gene signature linked to T‐cell exhaustion and worse outcomes in solid tumor patients was also found to correlate with CAR‐T cell resistance. Ferritin and myeloid‐derived suppressor cells were found to be prevalent in patients with poor response to axi‐cel. Both high levels of myeloid‐derived suppressor cells and tumor interferon signaling were associated with decreased CAR‐T cell growth, and systemic inflammation often coexisted with strong interferon signaling in these patients. These findings suggest that improving the quality of a patient's immune cells before leukapheresis for a better CAR‐T cell product and preparing and priming the immune system to receive CAR‐T cells to heighten response following administration may improve therapy outcomes. 68 , 69 , 70

The success of these pivotal CAR‐T trials has led to a boom of additional ongoing and planned trials. These efforts will attempt to address key questions, such as, will combination therapies improve on results thus far? Can CAR‐T cell treatment be expanded to other patient groups (children and patients with primary CNS lymphoma) with equal success? And, can CAR‐Ts be used earlier in the treatment paradigm; for example, with primary refractory disease or high‐risk disease?

Future strategies to improve CAR‐T cell therapy include the use of additional targets and modification of the constructs. So, CARs targeting solid tumor‐specific antigens such as mesothelin, a marker for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, showed promising results without concurrent toxicities. 71 Additionally, CAR‐T cell therapies detecting more than one antigen are being evaluated to minimize escape via antigen loss and to improve outcomes. Two CARs may be expressed from a single vector (bicistronic or dual CAR), thereby creating two separate populations of T cells comprising a single therapy. 72

Both CARs with novel signaling domains and those that produce accessory signals promise a safer delivery of therapy to patients. The synthetic notch receptors, or synNotch, allow for specific recognition of tumor sites and controlled CAR expression. On‐switch CARs consist of an extracellular antigen‐binding domain, costimulatory domains, and a key downstream signaling element that requires a priming small molecule on top of an antigen to trigger therapeutic activity. 73

Allogeneic CAR‐T cells are also being developed to make readily available CAR‐T cells for patients. Allogeneic CAR‐T cell therapy makes use of healthy donor T cells to create CAR‐T cells for patients, 74 which has the potential to remove the significant temporal barriers of both leukapheresis and manufacturing currently required for patient treatment.

In conclusion, CAR‐T cell therapy is a novel therapeutic strategy for adult patients with r/r DLBCL and aggressive B‐cell lymphomas who previously had few treatment options. The pivotal JULIET, ZUMA‐1, and TRANSCEND trials have demonstrated the efficacy and acceptable safety of CAR‐T cell therapies. Real‐world evidence confirms that these clinical trial findings can be translated to the clinic. Additional studies are needed to determine those patients for whom CD19‐directed CAR‐T cell therapy alone will be sufficient therapy and those patients who continue to have an unmet therapeutic need. Ongoing and planned trials hold the promise of enhancing CAR‐T cell efficacy through combination regimens, expanding CAR‐T cell therapies to other patient populations and B‐cell malignancies, and potentially advancing CAR‐T cell therapy to an earlier‐line therapy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Jason R. Westin is an advisor or consultant for Celgene, Curis, Genentech, Janssen, Juno, Kite, MorphoSys, and Novartis; and reports research support from Celgene, Curis, Forty Seven Inc, Genentech, Janssen, Kite, Novartis, and Unum. Marie José Kersten is an advisor or consultant for, and reports honoraria and travel support from Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Kite/Gilead, Miltenyi Biotec, MSD, Novartis, and Roche; and research support from Celgene, Roche, Kite/Gilead, and Takeda. Gilles Salles is an advisor or consultant for AbbVie, Allogene, Autolus, BeiGene, Celgene, Epizyme, Genmab, Gilead, Janssen, Kite, Merck, MorphoSys, Novartis, Roche, and VelosBio; reports honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celgene, Epizyme, Gilead, Janssen, Kite, Merck, MorphoSys, Novartis, and Roche; and reports participation in educational events for AbbVie, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Kite, MorphoSys, Novartis, and Roche. Jeremy S. Abramson is an advisor or consultant for Celgene, Genentech/Roche, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, and Seattle Genetics; and reports research funding from Celgene (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Millennium (Inst), and Seattle Genetics (Inst). Stephen J. Schuster is an advisor or consultant for Acerta, Allogene, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Celgene/Juno, Genentech/Roche, Loxo Oncology, Novartis, and Tessa Therapeutics; reports honoraria from Acerta, Allogene, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Celgene, Genentech/Roche, Loxo Oncology, Novartis, Nordic Nanovector, Pfizer, and Tessa Therapeutics; reports steering committee participation for AbbVie, Celgene, Novartis, Juno, Nordic Nanovector, and Pfizer; reports research support from AbbVie, Acerta, Celgene/Juno, DTRM Bio, Genentech, Incyte, Merck, Novartis, Portola, and TG therapeutics; and holds a patent with Novartis. Frederick L. Locke is a scientific advisor for Allogene, Amgen, BlueBird Bio, BMS/Celgene, Calibr, GammaDelta Therapeutics, Iovance, Janssen, Kite Pharma, Legend, Novartis, and Wugen; reports consultancy for Cellular Biomedicine Group Inc; reports research funding from Allogene (Inst), Kite (Inst), and Novartis (Inst); and reports his institution holding unlicensed patents in his name, in the field of cellular immunotherapy. Charalambos Andreadis is an advisor or consultant for Genentech, Gilead Sciences/Kite Pharma, and Karyopharm; reports honoraria from Bristol‐Myers Squibb/Celgene/Juno, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals; reports research funding from Bristol‐Myers Squibb/Celgene/Juno, Incyte, Merck, and Novartis; and is a current equity holder in Genentech.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support was provided by Mike Hobert, PhD (Healthcare Consultancy Group), and funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Westin JR, Kersten MJ, Salles G, et al. Efficacy and safety of CD19‐directed CAR‐T cell therapies in patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive B‐cell lymphomas: Observations from the JULIET, ZUMA‐1, and TRANSCEND trials. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(10):1295‐1312. 10.1002/ajh.26301

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION: NCT02445248 (JULIET), NCT02348216 (ZUMA‐1), and NCT02631044 (TRANSCEND‐NHL‐001).

[Correction added on July 23, 2021, after first online publication: The copyright was changed.]

Funding information Novartis

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. June CH, Sadelain M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):64‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):45‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B‐cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2545‐2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long‐term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B‐cell lymphoma (ZUMA‐1): a single‐arm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):31‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T‐cell therapy in refractory large B‐cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2531‐2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B‐cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet. 2020;396(10254):839‐852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) [US prescribing information]. Santa Monica, CA: Kite Pharma, Inc; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) [US prescribing information]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Breyanzi (lisocabtagene maraleucel) [US prescribing information]. Bothell, WA: Juno Therapeutics, Inc, A Bristol Myers Squibb Company; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam C, et al. Sustained disease control for adult patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma: an updated analysis of JULIET, a global pivotal phase 2 trial of tisagenlecleucel. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):1684. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Westin JR, Tam CS, Borchmann P, Jaeger U, McGuirk JP, Holte H, et al. Correlative analyses of patient and clinical characteristics associated with efficacy in tisagenlecleucel‐treated relapsed/refractory diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma patients in the JULIET trial. Presented at: 61st ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition; December 7–10, 2019; Orlando, FL. Abstract 4103.

- 12. Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Pivotal safety and efficacy results from TRANSCEND NHL 001, a multicenter phase 1 study of lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso‐cel) in relapsed/refractory (R/R) large B cell lymphomas. Blood. 2019;134(suppl 1):241. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawalekar OU, O'Connor RS, Fraietta JA, et al. Distinct signaling of coreceptors regulates specific metabolism pathways and impacts memory development in CAR T cells. Immunity. 2016;44(3):712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Milone MC, Fish JD, Carpenito C, et al. Chimeric receptors containing CD137 signal transduction domains mediate enhanced survival of T cells and increased antileukemic efficacy in vivo. Mol Ther. 2009;17(8):1453‐1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kochenderfer JN, Feldman SA, Zhao Y, et al. Construction and preclinical evaluation of an anti‐CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Immunother. 2009;32(7):689‐702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]