Abstract

Objective

To examine cancer‐related mortality in patients with severe mental disorders (SMI) in the Emilia Romagna (ER) Region, Northern Italy, during the period 2008–2017 and compare it with the regional population.

Methods

We used the ER Regional Mental Health Registry identifying all patients aged ≥18 years who had received an ICD‐9CM system diagnosis of SMI (i.e., schizophrenia or other functional psychosis, mania, or bipolar affective disorders) during a 10‐year period (2008–2017). Information on deaths (date and causes of death) were retrieved through the Regional Cause of Death Registry. Comparisons were made with the deaths and cause of deaths of the regional population over the same period.

Results

Amongst 12,385 patients suffering from SMI (64.1% schizophrenia spectrum and 36.9% bipolar spectrum disorders), 24% (range 21%–29%) died of cancer. In comparison with the general regional population, the mortality for cancer was about 50% higher among patients with SMI, irrespective if affected by schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. As for the site‐specific cancers, significant excesses were reported for stomach, central nervous system, respiratory, and pancreas cancer with a variability according to psychiatric diagnosis and gender.

Conclusions

Patients suffering from SMI had higher mortality risk than the regional population with some differences according to cancer type, gender, and psychiatric diagnosis. Proper cancer preventive and treatment interventions, including more effective risk modification strategies (e.g., smoking cessation, dietary habits) and screening for cancer, should be part of the agenda of all mental health departments in conjunction with other health care organizations, including psycho‐oncology.

Keywords: bipolar disorders, cancer, mortality, oncology, psychiatry, psycho‐oncology, schizophrenia

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last decades, a number of studies have brought attention to the problems of disparities and inequalities in the health of individuals affected by severe mental illness (SMI). Available data suggest an increased prevalence of physical illness which results in a life expectancy 15–20 years shorter among individuals with SMI than the general population. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Cancer has been indicated as one of the main culprits, not only because of its negative impact on quality of life and functioning, but also for the heavy toll it exerts on survival. 9

Preliminary investigations on cancer‐related mortality were carried out in the 1980s. They mostly suggested similar or slightly higher mortality rates in SMI populations than in the general population. 10 , 11 , 12 Whereas, more recent studies present a radically different scenario, 13 for example, in a large Swedish cohort study of 6,097,834 people followed for 7 years (2003–2009), patients with schizophrenia displayed a markedly premature mortality: the leading causes were ischemic heart disease and cancer, which appeared to be underdiagnosed. 14 In the United States, Olfson et al. 15 found that patients with schizophrenia had a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) (i.e., the ratio between the observed and the expected number of deaths) of 2.4 (95% CI, 2.4–2.5) for lung cancer, compared with the general population. In a further large Danish study on 56,152 women diagnosed with early‐stage breast cancer, patients with psychotic disorders were less likely to be treated following proper cancer guidelines and this resulted in a significantly shorter survival than women with cancer but no SMI. 16 Similarly, patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 were less likely to receive stage‐appropriate treatment for cancer, resulting in poorer outcomes across several other studies 17–21. 21 Such data have been recently summarized in a meta‐analysis of 1,162,971 subjects, confirming that individuals with schizophrenia run a significantly higher risk of mortality from breast, colon, and lung cancer. 22

Cancer‐related morbidity and premature mortality seem to plague patients with bipolar‐spectrum disorders not less than it does those with schizophrenia. Although this disorder is more prevalent than schizophrenia, less data are available showing a higher risk of developing cancer 23 and a higher SMR with respect to the general population. 24 , 25 , 26 With respect to this, in a 5‐year‐period study carried out in New Zealand among 8762 people with breast and 4022 with colorectal cancer, those affected by schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or bipolar disorders received diagnosis at a later stage and that contributed, after adjusting for several factors, a two and half times higher mortality for breast cancer and three times for colon cancer than people without SMI. 27

A number of international studies on mortality in SMI are based on hospital‐based registry, with the limit that data related to lifestyle and other variables evident in community‐based studies cannot be examined. In Italy, since the closure of long‐stay psychiatric hospitals, and the reorganization of mental health services with the development of community‐based psychiatry, 28 , 29 studies examining the physical health care of people with SMI are important. In the few studies available on this subject, an increased risk of mortality for all causes was found both among outpatients and those who were admitted for the first time as inpatients in psychiatric units. 30 A higher mortality rate caused by several medical disorders was found in other studies carried out in Northern Italy on patients of community mental health. 31 , 32 More recently, Berardi et al., in a large 10‐year retrospective cohort investigation of 137,351 patients, found an SMR of 1.99 with diseases of circulatory and respiratory systems, as well as neoplasms as the principal contributors to the mortality gap. 33

Since no study, however, is available in Italy, specifically exploring cancer‐related mortality in patients with SMI, the aim of the present work was to explore cancer mortality in a population with schizophrenia‐spectrum versus bipolar‐spectrum disorders from a well‐defined community‐based catchment area, over a period of 10 years and compare it with the general population.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study setting and sources of data

This study was carried out in the Emilia Romagna (ER) Region, an area in Northern Italy with about 4.5 million inhabitants and nine provinces (Bologna, as capital of the Region, Ferrara, Forli‐Cesena, Modena, Parma, Piacenza, Ravenna, Reggio‐Emilia, and Rimini). In the late 1960s, the ER Region was one of the first to experience the switch from asylum‐based to community‐based psychiatric care 34 , 35 ER Region rapidly implemented the new organization of mental health services following the 1978 Italian mental health law (13 May 1978, Law 180), within the general reform that instituted the National Health Service (23 December 1978, Law 833).

The Regional Mental Health Registry was used to identify participants and retrieve demographic data (age, gender, citizenship, and residency) together with psychiatric diagnosis and date of first admittance to the mental healthcare system. The Registry contains demographic and clinical information of all inpatients and outpatients referring to the Mental Health Departments (MHDs) of the Region as detailed in a previous study. 33 Demographic features, as well as diagnoses, are routinely recorded at the first clinical evaluation and then regularly updated by clinicians.

For the purpose of this study, we included patients aged 18 years or over who had received a diagnosis of severe mental disorder, namely schizophrenia or other functional psychosis, mania, or bipolar affective disorders, from a psychiatric service within the MHDs of the ER Region in the period between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2017. Residents outside the ER Region and patients who were registered with the MHDs before 2008 were excluded.

To ascertain the vital status, we linked the Mental Health Registry with the Regional Cause of Death Registry using an anonymous identity code. This code is provided to all health records of the residents by the regional authority. We defined a participant's death if the record of both registries match each other. The Regional Cause of Death Registry covers all the deaths in the Region and it contains anonymized information about sociodemographic characteristics, date, setting, circumstances, and initial cause of death. The cause of death derives from information recorded in the medical section of the death certificate by a certifier (attending physician, medical examiner, coroner), and it is classified according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Disease (ICD‐10) (Table S1) and coded according to the WHO rules. All information is collected following national protocols. Both registries undergo regular systematic quality checks. Change of residence to another region, as retrieved from the Regional Registry Office, indicated a lost to follow‐up because of the impossibility to ascertain the life status of the patients. The regional population was used as the comparator group. The Regional Population Archive provided aggregated data on the age and gender composition of this population. (https://statistica.regione.emilia‐romagna.it/servizi‐online/statistica‐self‐service/popolazione).

The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee (N. 341/2019). All records in the Mental Health Registry were anonymized.

2.2. Mental Health Registry and psychiatric diagnoses

The regional Mental Health Registry was used to identify study participants. The Mental Health Registry was implemented in the 1980s, but was completely operative in the whole regional catchment area only after the early 2000s. We decided to begin data collection from 2008 onwards (and therefore to consider a 10‐year period). This date was chosen to ensure a bedding‐in period of several years during which time any problems in the system should have been resolved. This excluded early data with possible weaknesses, and it ensured that the present study used more reliable and good quality data. Residents outside the ER Region, patients with an access to the MHD before 2008, and patients with intellectual disability, dementia, delirium, or other mental disorders following organic brain damage (ICD9‐CM 290, 293, 294, 299.0, 299.01, 310, 317, 318, 319) were excluded. Demographic features, dates of visits, and treatment (i.e., pharmacological, psychological, rehabilitative) of all inpatients and outpatients who have accessed the MHDs in the region are routinely recorded at the first clinical evaluation and then constantly updated by clinicians; finally, all data are collected via an Information System at regional level.

The Registry contains information on psychiatric diagnoses collected by clinicians and defined according to the International Classification of Disease, 9th and 10th revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9 CM and ICD‐10 CM) (ICD‐9CM diagnosis). Because of the observational nature, the diagnoses in regional psychiatric services are clinically made (therefore not by using the structured Composite International Diagnostic Interview), with however the possibility for the service to discuss the cases, with the patients seen by the team rather than a single physician, according to the team‐centered approach used in ER Region. Schizophrenia or other functional psychoses were defined as ICD‐9 CM codes 295, 297, 298, excl. 298.0, 299 excl. 299.0, 299.00, 299.01 or ICD‐10 F2; and mania and bipolar affective disorders by ICD‐9 CM 296.0*, 296.1*, 296.4*, 296.5*, 296.6*, 296.7, 296.8* excl. 296.82 or ICD‐10 F30, F31, F34.0.

2.3. Statistical analyses

To describe the causes of death, we calculated the proportional mortality, namely the number of deaths within a population due to different causes during a time period over the total. In particular, we considered the proportional mortality for all neoplasms and site‐specific malignant neoplasms in the study population, separately among patients with schizophrenia and other functional psychoses and among patients with mania and bipolar affective disorders and in the regional population.

To compare the risk of mortality between the regional and the study population, we computed the SMR. The SMR was calculated as the ratio of observed deaths in the study population divided by the number of expected deaths if the study population had the same gender, age (grouped in classes)‐specific rates as the regional population, the standard. Rates of the standard population were obtained by using the above mentioned Regional Cause of Death Registry and the Population Archive. An SMR equal to 1 means that the observed deaths are equal to the expected, if it is greater than 1, it means that the observed deaths are higher than the expected and on the contrary, if it is lower than 1, it means that the observed deaths are smaller than the expected. SMRs with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed by gender (controlling for age class only), cancer and psychiatric diagnosis in case of more than 3 observed events. We considered the differences significant if the CI of the SMR excluded the value of one. The denominator was the person‐years, calculated as the difference between 31 December 2017 or the date of leaving to another region or of death (if applicable), and the date of first access to a MHD.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample characteristics

The cohort consisted of 12,385 patients suffering from SMI, 7940 with schizophrenia and other functional psychoses (64.1%) and 4445 with mania and bipolar disorders (36.9%). Table 1 shows the main demographic characteristics of the population at the time of their first access to the MHD. The regional population contributed 37,292,694 person‐years.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population at their first access to the Regional Mental Health Department

| Severe mental disorders | Schizophrenia and other functional psychosis | Mania and bipolar affective disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 12,385 | 100.0 | 7940 | 100.0 | 4445 | 100.00 | |

| Gender | Women | 6524 | 52.68 | 3989 | 50.24 | 2535 | 57.03 |

| Men | 5861 | 47.32 | 3951 | 49.76 | 1910 | 42.97 | |

| Age group. years | 18–24 | 1443 | 11.65 | 1174 | 14.79 | 269 | 6.05 |

| 25–44 | 4528 | 36.56 | 3066 | 38.61 | 1462 | 32.89 | |

| 45–64 | 4113 | 33.21 | 2255 | 28.40 | 1858 | 41.80 | |

| 65–74 | 1359 | 10.97 | 777 | 9.79 | 582 | 13.09 | |

| 75–84 | 728 | 5.88 | 505 | 6.36 | 223 | 5.02 | |

| 85+ | 214 | 1.73 | 163 | 2.05 | 51 | 1.15 | |

| Citizenship | Italian | 10,659 | 86.06 | 6561 | 82.63 | 4098 | 92.19 |

| Non Italian | 1726 | 13.94 | 1379 | 17.37 | 347 | 7.81 | |

| Residency | Urban a | 4895 | 39.52 | 2961 | 37.29 | 1934 | 43.51 |

| Rural | 7490 | 60.48 | 4979 | 62.71 | 2511 | 56.49 | |

All residents in municipalities with more than 60,000 inhabitants.

3.2. Proportional mortality for cancer

During the study period there were 1095 deaths for cancer in the study population and 143,311 in the regional population. Among the study population with SMI, 23% of all deaths were due to cancer, a proportion inferior to that of the general population (29.6%; p < 0.001), in particular, among patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (21.2%, p < 0.001), while it was similar among patients with bipolar spectrum disorders (28.6%, p = 0.725). When the population was split by gender, the proportion of male patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders or with bipolar spectrum disorders who died of cancer (21.242%, 18.5% and 26.5%, respectively) was lower than in the male general population (34.2%, p < 0.001). On the contrary, among females, the proportion of death by cancer in the SMI population was 25.5%, as in the female general population and the differences were not significant when considering the two subgroups of patients: 23.3% in patients with schizophrenia (p = 0.339) and 30.6% in patients with bipolar disorders (p = 0.124) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Number of deaths, all causes, all neoplasms, and site‐specific neoplasms with % proportion over the total; regional and study population, whole sample and by gender

| Regional population | Severe mental disorders | Schizophrenia and other functional psychosis | Mania and bipolar affective disorders | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site‐specific neoplasms | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total deaths | 484,102 | 100.00 | 1095 | 100 | 745 | 100 | 350 | 100 | ||

| Total neoplasm | 143,311 | 29.60 | 258 | 23.56 | 158 | 21.21 | 100 | 28.57 | ||

| Esophagus | 1330 | 0.27 | 2 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.13 | 1 | 0.29 | ||

| Stomach | 9149 | 1.89 | 18 | 1.64 | 10 | 1.34 | 8 | 2.29 | ||

| Colon, rectosigmoid, rectum, anus | 15,043 | 3.11 | 25 | 2.28 | 14 | 1.88 | 11 | 3.14 | ||

| Liver, gallbladder, biliary tract | 9144 | 1.89 | 16 | 1.46 | 10 | 1.34 | 6 | 1.71 | ||

| Pancreas | 9834 | 2.03 | 17 | 1.55 | 13 | 1.74 | 4 | 1.14 | ||

| Larynx | 996 | 0.21 | 1 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.29 | ||

| Trachea, bronchus and lung | 28,492 | 5.89 | 52 | 4.75 | 28 | 3.76 | 24 | 6.86 | ||

| Melanoma | 1413 | 0.29 | 1 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.29 | ||

| Breast | 9610 | 1.99 | 22 | 2.01 | 12 | 1.61 | 10 | 2.86 | ||

| Ovary and other female genital organ | 3087 | 0.64 | 1 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Uterus (cervix, corpus, unspecified) | 2338 | 0.48 | 7 | 0.64 | 5 | 0.67 | 2 | 0.57 | ||

| Prostate | 5694 | 1.18 | 7 | 0.64 | 5 | 0.67 | 2 | 0.57 | ||

| Kidney, pelvis, ureter and unspecified urinary organs | 4420 | 0.91 | 9 | 0.82 | 6 | 0.81 | 3 | 0.86 | ||

| Bladder | 4962 | 1.02 | 6 | 0.55 | 4 | 0.54 | 2 | 0.57 | ||

| Meninges, brain other parts of CNS | 3497 | 0.72 | 9 | 0.82 | 2 | 0.27 | 7 | 2.00 | ||

| Lymphoid, hematopoietic and related lymphoid lymphopoietic, hematopoietic and related tissue | 15,316 | 3.16 | 18 | 1.64 | 12 | 1.61 | 6 | 1.71 | ||

| Females | ||||||||||

| Total deaths | 255,264 | 100.00 | 596 | 100.00 | 416 | 100.00 | 180 | 100.00 | ||

| Total neoplasm | 65,137 | 25.52 | 152 | 25.50 | 97 | 23.32 | 55 | 30.56 | ||

| Esophagus | 374 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.24 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Stomach | 3949 | 1.55 | 4 | 0.67 | 3 | 0.72 | 1 | 0.56 | ||

| Colon, rectosigmoid, rectum, anus | 7095 | 2.78 | 15 | 2.52 | 8 | 1.92 | 7 | 3.89 | ||

| Liver, gallbladder, biliary tract | 3738 | 1.46 | 9 | 1.51 | 4 | 0.96 | 5 | 2.78 | ||

| Pancreas | 5108 | 2.00 | 12 | 2.01 | 11 | 2.64 | 1 | 0.56 | ||

| Larynx | 129.00 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Trachea, bronchus and lung | 8669 | 3.40 | 25 | 4.19 | 15 | 3.61 | 10 | 5.56 | ||

| Melanoma | 572 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.17 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.56 | ||

| Breast | 9518 | 3.73 | 22 | 3.69 | 12 | 2.88 | 10 | 5.56 | ||

| Ovary and other female genital organ | 3087 | 1.21 | 1 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.24 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Uterus (cervix, corpus, unspecified) | 2338 | 0.92 | 7 | 1.17 | 5 | 1.20 | 2 | 1.11 | ||

| Prostate | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Kidney, pelvis, ureter and unspecified urinary organs | 1540 | 0.60 | 3 | 0.50 | 2 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.56 | ||

| Bladder | 1268 | 0.50 | 3 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.24 | 2 | 1.11 | ||

| Meninges, brain other parts of CNS | 1626 | 0.64 | 3 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.24 | 2 | 1.11 | ||

| Lymphoid, hematopoietic and related lymphoid lymphopoietic, hematopoietic and related tissue | 7394 | 2.90 | 13 | 2.18 | 10 | 2.40 | 3 | 1.67 | ||

| Males | ||||||||||

| Total deaths | 228,838 | 100.00 | 499 | 100.00 | 329 | 100.00 | 170 | 100.00 | ||

| Total neoplasm | 78,174 | 34.16 | 106 | 21.24 | 61 | 18.54 | 45 | 26.47 | ||

| Esophagus | 956 | 0..42 | 1 | 0.20 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.59 | ||

| Stomach | 5200 | 2.27 | 14 | 2.81 | 7 | 2.13 | 7 | 4.12 | ||

| Colon, rectosigmoid, rectum, anus | 7948 | 3.47 | 10 | 2.00 | 6 | 1.82 | 4 | 2.35 | ||

| Liver, gallbladder, biliary tract | 5406 | 2.36 | 7 | 1.40 | 6 | 1.82 | 1 | 0.59 | ||

| Pancreas | 4726 | 2.07 | 5 | 1.00 | 2 | 0.61 | 3 | 1.76 | ||

| Larynx | 867 | 0.38 | 1 | 0.20 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.59 | ||

| Trachea, bronchus and lung | 19,823 | 8.66 | 27 | 5.41 | 13 | 3.95 | 14 | 8.24 | ||

| Melanoma | 841 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Breast | 92 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Ovary and other female genital organ | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Uterus (cervix, corpus, unspecified) | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Prostate | 5694 | 2.49 | 7 | 1.40 | 5 | 1.52 | 2 | 1.18 | ||

| Kidney, pelvis, ureter and unspecified urinary organs | 2880 | 1.26 | 6 | 1.20 | 4 | 1.22 | 2 | 1.18 | ||

| Bladder | 3694 | 1.61 | 3 | 0.60 | 3 | 0.91 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| Meninges, brain other parts of CNS | 1871 | 0.82 | 6 | 1.20 | 1 | 0.30 | 5 | 2.94 | ||

| Lymphoid, hematopoietic and related lymphoid lymphopoietic, hematopoietic and related tissue | 7922 | 3.46 | 5 | 1.00 | 2 | 0.61 | 3 | 1.76 | ||

When examining the single cancer diagnoses, trachea, bronchial, and lung cancers were the most frequent cause of cancer death in the regional and in the whole study population. Trachea, bronchial, and lung cancer remained the leading cause of cancer death in female patients with SMI, whereas the leading cause of cancer death in the female regional population was breast cancer. In males, lung cancer was always the first cause, followed by cancers of the stomach in the study population and not by the cancer of the colon, rectum, and anus as in the general population.

Regarding the age of death, there was a higher proportion of deaths in the younger age class among patients with SMI than among the general population. More specifically death at the age 45–64 and 65–74 years was higher (p < 0.001 and p = 0.009) and the death at the age 75–84 or 85+ was lower (p = 0.058 and p < 0.001), irrespective of the psychiatric diagnosis (schizophrenia; bipolar disorders) than the general population (Table S2).

3.3. Standardized mortality ratio for cancer

As reported in Table 3, the all‐cause mortality was more than two times higher in patients with SMI than expected from the regional population (SMR 2.13, 95% CI 2.00–2.25). The mortality for cancer was about 50% higher than in the regional population (SMR 1.49, 95% CI 1.31–1.68). The same excess was registered in patients with schizophrenia and other functional psychosis (SMR 1.49, 95% CI 1.27–1.74) and in patients with mania and bipolar affective disorders (SMR 1.5, 95% CI 1.22–1.82). Males show higher excess of mortality than females when considering total mortality (SMR 2.35, 95% CI: 2.15–2.57 vs. 1.97, 95%. CI: 1.81–2.13), but not when considering only cancer related deaths, where females resulted to have higher SMR than males, although the difference was not significant.

TABLE 3.

SMR for all causes, all neoplasms and for site‐specific neoplasms, whole sample and by gender

| Severe mental disorders | Schizophrenia and other functional psychosis | Mania and bipolar affective disorders | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site‐specific neoplasms | SMR | 95% CI | SMR | 95% CI | SMR | 95% CI | ||||

| Total deaths | 2.13 | 2.00 | 2.25 | 2.22 | 2.06 | 2.38 | 1.96 | 1.76 | 2.17 | |

| Total neoplasm | 1.49 | 1.31 | 1.68 | 1.49 | 1.27 | 1.74 | 1.50 | 1.22 | 1.82 | |

| Esophagus | 1.21 | 0.15 | 4.38 | |||||||

| Stomach | 1.71 | 1.01 | 2.70 | 1.53 | 0.73 | 2.81 | 2.01 | 0.87 | 3.95 | |

| Colon, rectosigmoid, rectum, anus | 1.42 | 0.92 | 2.09 | 1.28 | 0.70 | 2.14 | 1.65 | 0.82 | 2.95 | |

| Liver, gallbladder, biliary tract | 1.46 | 0.83 | 2.37 | 1.59 | 0.72 | 2.74 | 1.41 | 0.52 | 3.06 | |

| Pancreas | 1.37 | 0.80 | 2.20 | 1.72 | 0.91 | 2.93 | 0.83 | 0.22 | 2.13 | |

| Larynx | ||||||||||

| Trachea, bronchus and lung | 1.52 | 1.14 | 2.00 | 1.38 | 0.92 | 1.99 | 1.73 | 1.11 | 2.58 | |

| Melanoma | ||||||||||

| Breast | 1.51 | 0.95 | 2.29 | 1.34 | 0.69 | 2.34 | 1.79 | 0.86 | 3.29 | |

| Ovary and other female genital organ | ||||||||||

| Uterus (cervix, corpus, unspecified) | 1.96 | 0.79 | 4.03 | 2.28 | 0.74 | 5.31 | ||||

| Prostate | 1.46 | 0.59 | 3.00 | 1.68 | 0.54 | 3.91 | ||||

| Kidney, pelvis, ureter and unspecified urinary organs | 1.79 | 0.82 | 3.40 | 1.93 | 0.71 | 4.21 | ||||

| Bladder | 1.20 | 0.44 | 2.62 | 1.29 | 0.35 | 3.30 | ||||

| Meninges, brain other parts of CNS | 1.79 | 0.82 | 3.41 | 3.47 | 1.40 | 7.15 | ||||

| Lymphoid, hematopoietic and related tissue | 0.99 | 0.59 | 1.57 | 1.06 | 0.55 | 1.86 | 0.88 | 0.32 | 1.91 | |

| Females | ||||||||||

| Total deaths | 1.97 | 1.81 | 2.13 | 2.04 | 1.85 | 2.42 | 1.82 | 1.57 | 2.11 | |

| Total neoplasm | 1.62 | 1.37 | 1.90 | 1.64 | 1.65 | 1.34 | 1.58 | 1.19 | 2.06 | |

| Esophagus | ||||||||||

| Stomach | 0.75 | 0.20 | 1.92 | |||||||

| Colon, rectosigmoid, rectum, anus | 1.55 | 0.87 | 2.55 | 1.29 | 0.56 | 2.54 | 2.01 | 0.81 | 4.15 | |

| Liver, gallbladder, biliary tract | 1.72 | 0.79 | 3.26 | 1.20 | 0.33 | 3.07 | 2.64 | 0.86 | 6.16 | |

| Pancreas | 1.64 | 0.85 | 2.86 | 2.38 | 1.19 | 4.26 | ||||

| Larynx | ||||||||||

| Trachea, bronchus and lung | 1.85 | 1.20 | 2.73 | 1.82 | 1.02 | 3.01 | 1.19 | 0.91 | 3.50 | |

| Melanoma | ||||||||||

| Breast | 1.52 | 0.95 | 2.30 | 1.35 | 0.70 | 2.36 | 1.80 | 0.86 | 3.31 | |

| Ovary and other female genital organ | ||||||||||

| Uterus (cervix, corpus, unspecified) | 1.96 | 0.79 | 4.03 | 2.28 | 0.74 | 5.31 | ||||

| Prostate | ||||||||||

| Kidney, pelvis, ureter and unspecified urinary organs | ||||||||||

| Bladder | ||||||||||

| Meninges, brain other parts of CNS | ||||||||||

| Lymphoid, hematopoietic and related tissue | 1.27 | 0.69 | 2.17 | 1.53 | 0.73 | 2.81 | 1.,27 | 0.69 | 2.17 | |

| Males | ||||||||||

| Total deaths | 2.35 | 2.15 | 2.57 | 2.49 | 2.23 | 2.78 | 2.12 | 1.18 | 2.46 | |

| Total neoplasm | 1.34 | 1.10 | 1.62 | 1.29 | 0.99 | 1.66 | 1.41 | 1.03 | 1.88 | |

| Esophagus | ||||||||||

| Stomach | 2.69 | 1.47 | 4.51 | 2.25 | 0.90 | 4.63 | 3.34 | 1.34 | 6.88 | |

| Colon, rectosigmoid, rectum, anus | 1.26 | 0.60 | 2.31 | 1.26 | 0.46 | 2.74 | 1.25 | 0.34 | 3.20 | |

| Liver, gallbladder, biliary tract | 1.22 | 0.49 | 2.51 | 1.78 | 0.65 | 3.88 | ||||

| Pancreas | 0.99 | 0.32 | 2.30 | |||||||

| Larynx | ||||||||||

| Trachea, bronchus and lung | 1.31 | 0.86 | 1.90 | 1.08 | 0.57 | 1.85 | 1.63 | 0.89 | 2.73 | |

| Melanoma | ||||||||||

| Breast | ||||||||||

| Ovary and other female genital organ | ||||||||||

| Uterus (cervix, corpus, unspecified) | ||||||||||

| Prostate | 1.46 | 0.59 | 3.00 | 1.68 | 0.54 | 3.91 | ||||

| Kidney, pelvis, ureter and unspecified urinary organs | 2.05 | 0.75 | 4.46 | 2.28 | 0.62 | 5.84 | ||||

| Bladder | ||||||||||

| Meninges, brain other parts of CNS | 2.54 | 0.93 | 5.52 | 5.18 | 1.68 | 12.00 | ||||

| Lymphoid, hematopoietic and related tissue | 0.64 | 0.21 | 1.48 | |||||||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

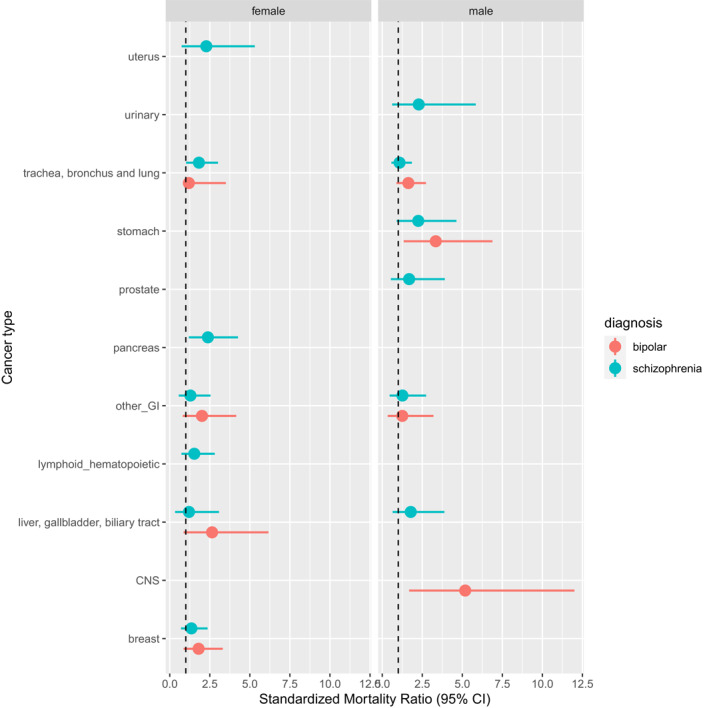

An excess in mortality in comparison to the regional population was found for almost all site‐specific neoplasms, even if the confidence interval of the estimates mostly included 1 except for some site‐specific cancer (Table 3 and Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Standardized mortality ratio for different cancers by psychiatric diagnosis

Regarding the respiratory system, there was a significant excess in mortality for trachea, bronchus, and lung cancer in all and in female patients with SMI, in all patients with mania and bipolar affective disorders, and in females with schizophrenia and other functional psychosis (SMR range 1.52–1.85).

As for the gastrointestinal tract, stomach cancer mortality showed an excess in all and males patients with SMI and in males with mania and bipolar affective disorders (SMR range 1.71–3.34).

Cancer of the meninges and the brain was increased in all patients (in male patients with mania and bipolar affective disorders by more than three times), whereas mortality for pancreas cancer was increased only in females with schizophrenia (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Standardized mortality ratio for different cancers by gender and psychiatric diagnosis

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study examined cancer‐related mortality in a well‐defined representative population of individuals with SMI living in the community, over a period of 10 years. Our main finding was that cancer‐related mortality was higher among patients with SMI, including schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar spectrum disorders, with respect to the general population.

More specifically, as a first result, we showed that the cause of death due to cancer regarded about 25% of deaths in patients with SMI, with a lower proportion amongst males with schizophrenia and higher among females with bipolar spectrum disorders. This is in line with other investigation showing that, as expected, the causes of death among people with SMI can be mainly related to direct complications of the psychiatric disorder itself (e.g., suicide) or indirect complications (e.g., cardiovascular and metabolic side‐effects of drugs). 2 , 3

Regarding the SMR, however, patients with SMI had a higher excess of cancer mortality in comparison with the general population. This was true both in the female and male populations and both for schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar spectrum disorders. The excess in mortality was significant for some kind of cancers, mainly the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., stomach and pancreas), respiratory system, and the central nervous system (CNS), although a variability according to gender and psychiatric diagnosis was registered.

The data confirm other investigations carried out in large population of patients with schizophrenia showing an increased risk of mortality for many forms of cancer, although not all the studies are in agreement with respect to the cancer site. 7

As far as bipolar spectrum disorders are concerned, we also found an increased risk for some types of cancer, in contrast with other studies that showed a similar trend with the general population. 36

The explanation of why patients with SMI have a higher risk of mortality for cancer in comparison with the general population is not easy. Many factors have been postulated as possible causes of these findings in other studies. For example, a less likelihood to participate to cancer screening programs have been demonstrated both in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. 37 , 38 This can have determined a diagnosis of cancer in advanced stages because of less chances for patients to receive adequate screening programs, 39 as well as a lower likelihood to receive specialized interventions after diagnosis, including surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. 40 , 41

In our study we noted a significant excess in mortality for some kind of tumors such as lung, stomach, and pancreas cancers that evidence proved to be more or less attributable to lifestyles risk factors like smoking, diet, or alcohol use. In fact, unhealthy lifestyles such as lacking of good nutrition 42 and physical activity, 43 as well as smoking 44 , 45 and alcohol abuse 46 are largely prevalent among people with mental disorders and might partly explain the elevated risk of dying from these types of cancer.

In contrast, it is less easy to explain the excess in mortality for brain tumors in patients with SMI. Although it is well known that psychotic symptoms can emerge in patients with brain tumors, 47 other studies showed a lower risk (e.g., glioma) in patients with SMI (e.g., schizophrenia). 48 Since we do not have information about the possible role of brain tumors in causing SMI in our sample, more research is necessary to explore this relationship.

We did not observe a significant difference in risk of mortality for the groups of neoplasms that included cancers such as breast, colorectum, and cervix cancer whose prognosis is related to screening attendance. Mortality for these cancers is higher than in the general population but the difference in not significant. This finding could be due to the small number of patients that limits the robustness of the estimates. In addition, the lack of significant differences in mortality for these cancers could be ascribed to the attention devoted to screening activities in the ER Region. Some studies underlined that screening programs could be effective in reducing inequalities in survival after the diagnosis of some cancer, breast cancer in particular, at least where they are characterized by high coverage and by a free facilitated care pathway for screened positive subjects. 49

In our study, we could not examine these specific issues and further research is needed to evaluate, as done in other studies, cancer‐risk behavior of patients with SMI, their participation to cancer screening programs, and the quality and characteristics of cancer care.

In conclusion, the study in a large population of the Italian ER Region indicated a higher mortality among patients with SMI with respect to the general population. Importantly, our results are representative for the people with SMI in the Region, since most, if not the totality of them, are in fact taken care by the Regional Health Trust DMH, which includes a series of different mental health services (e.g., outpatient clinics, rehabilitation and day‐care facilities, inpatient psychiatric units). Although the different organizational system do not allow to make correct comparison with studies carried put in other countries (e.g., United Kingdom, United States), examining the same field of mortality in SMI, our data confirm the problem of lower survival caused by cancer when patients have a severe psychiatric condition, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders.

5. STUDY LIMITATIONS

The results of our study should be weighed considering various limitations, which warrant discussion. A first limitation is that we examined mortality of people of one of wealthiest Italian regions, with an advanced and efficient regional health system, and a policy of integration between primary care and mental health. 50 Therefore, our results cannot be generalized to the whole country. Also, our cohort was entirely composed of people resident in the region and this theoretically could have caused an underestimation of mortality since non‐resident or homeless people may be prone to higher mortality. However, the proportion of persons excluded as not being resident is low (about 1% of the caseload). In spite of the fairly long time span of the study, for some site‐specific cancers, the number of events was very small, leading to estimates with relatively large confidence interval requiring confirmation in larger studies.

6. CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

The most important clinical implication of the study is related to the need for more attention to this vulnerable segment of the population affected by SMI. Both community healthcare providers, such as primary care physicians, and mental health professionals should be aware of difficulties in the pathway to care. With respect to this, models of improving the healthcare system have been proposed, including the enhancement of cancer screening rate and early detection of cancer for patients with SMI. Activation of public health services, promotion of healthy behavior (e.g., smoking cessation programs and services, given the high rate of mortality for lung cancer) and healthy lifestyles (e.g., dietary habits, physical exercise) for this vulnerable population, via specific campaigns involving both mental health, psychosocial oncology and oncology departments, is mandatory. 51 , 52 Therefore, physical health related to cancer risk, diagnosis, and treatment should be an essential component of intervention in psychiatry, in order to favor the access to health services which, in turn, facilitates longer term benefits, such as reduced morbidity and mortality. 52 , 53

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the work described in their manuscript. LG received grants from Eisai and Angelini and royalties from Springer, Wiley, and Oxford University Press.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee (N. 341/2019). All records in the Mental Health Register were anonymized.

Supporting information

Table S1

Table S2

ACNKOWLEDGMENT

The authors are indebted to all the Regional Health Care Services and Mental Health Departments involved.

Open Access Funding provided by Universita Politecnica delle Marche within the CRUI–CARE Agreement.

Grassi L, Stivanello E, Belvederi Murri M, et al. Mortality from cancer in people with severe mental disorders in Emilia Romagna Region, Italy. Psychooncology. 2021;30(12):2039‐2051. 10.1002/pon.5805

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Thornicroft G. Physical health disparities and mental illness: the scandal of premature mortality. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):441‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu NH, Daumit GL, Dua T, et al. Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):30‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Momen NC, Plana‐Ripoll O, Agerbo E, et al. Association between mental disorders and subsequent medical conditions. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1721‐1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123‐1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Viron MJ, Stern TA. The impact of serious mental illness on health and healthcare. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(6):458‐465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334‐341. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grassi L, Riba M. Cancer and severe mental illness: bi‐directional problems and potential solutions. Psycho‐oncology. 2020;29(10):1445‐1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:425‐448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(2):138‐151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mortensen PB, Juel K. Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenic patients in Denmark. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;81(4):372‐377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saku M, Tokudome S, Ikeda M, et al. Mortality in psychiatric patients, with a specific focus on cancer mortality associated with schizophrenia. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(2):366‐372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lawrence D, D’Arcy C, Holman J, Jablensky AV, Threfall TJ, Fuller SA. Excess cancer mortality in Western Australian psychiatric patients due to higher case fatality rates. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(5):382‐388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhuo C, Tao R, Jiang R, Lin X, Shao M. Cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;211(1):7‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):324‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, Stroup TS. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172‐1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dalton SO, Suppli NP, Ewertz M, Kroman N, Grassi L, Johansen C. Impact of schizophrenia and related disorders on mortality from breast cancer: a population‐based cohort study in Denmark. Breast. 2018;40:170‐176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chou FHC, Tsai KY, Su CY, Lee CC. The incidence and relative risk factors for developing cancer among patients with schizophrenia: a nine‐year follow‐up study. Schizophr Res. 2011;129(2‐3):97‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bradford DW, Goulet J, Hunt M, Cunningham NC, Hoff R. A cohort study of mortality in individuals with and without schizophrenia after diagnosis of lung cancer. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(12):e1626‐e1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tran E, Rouillon F, Loze JY, et al. Cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia: an 11‐year prospective cohort study. Cancer. 2009;115(15):3555‐3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fried DA, Sadeghi‐Nejad H, Gu D, et al. Impact of serious mental illness on the treatment and mortality of older patients with locoregional high‐grade (nonmetastatic) prostate cancer: retrospective cohort analysis of 49 985 SEER‐Medicare patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2013. Cancer Med. 2019;8(5):2612‐2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bergamo C, Sigel K, Mhango G, Kale M, Wisnivesky JP. Inequalities in lung cancer care of elderly patients with schizophrenia: an observational cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(3):215‐220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ni L, Wu J, Long Y, et al. Mortality of site‐specific cancer in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. BarChana M, Levav I, Lipshitz I, et al. Enhanced cancer risk among patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1‐2):43‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McGinty EE, Zhang Y, Guallar E, et al. Cancer incidence in a sample of Maryland residents with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(7):714‐717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen WY, Huang SJ, Chang CK, et al. Excess mortality and risk factors for mortality among patients with severe mental disorders receiving home care case management. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021;75(2):109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lawrence WR, Kuliszewski MG, Hosler AS, et al. Association between preexisting mental illnesses and mortality among medicaid‐insured women diagnosed with breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2021;270:113643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cunningham R, Sarfati D, Stanley J, Peterson D, Collings S. Cancer survival in the context of mental illness: a national cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(6):501‐506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burti L, Benson PR. Psychiatric reform in Italy: developments since 1978. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1996;19(3‐4):373‐390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amaddeo F, Barbui C. Celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Italian Mental Health reform. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(4):311‐313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grigoletti L, Perini G, Rossi A, et al. Mortality and cause of death among psychiatric patients: a 20‐year case‐register study in an area with a community‐based system of care. Psychol Med. 2009;39(11):1875‐1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berardi D, Pavarin RM, Chierzi F, et al. Mortality rates and trends among bologna community mental health service users: a 13‐year cohort study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(12):944‐949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Starace F, Mungai F, Baccari F, Galeazzi GM. Excess mortality in people with mental illness: findings from a Northern Italy psychiatric case register. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(3):249‐257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Berardi D, Stivanello E, Chierzi F, et al. Mortality in mental health patients of the Emilia–Romagna region of Italy: a registry‐based study. Psychiatry Res. 2021;296:113702. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tansella M, Williams P. The Italian experience and its implications. Psychol Med. 1987;17(2):283‐289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fioritti A, Russo L, Melega V. Reform said or done? The case of Emilia‐Romagna within the Italian psychiatric context. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(1):94‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hippisley‐Cox J, Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Parker C. Risk of malignancy in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: nested case‐control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1368‐1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hwong A, Wang K, Bent S, Mangurian C. Breast cancer screening in women with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(3):263‐268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ouk M, Edwards JD, Colby‐Milley J, Kiss A, Swardfager W, Law M. Psychiatric morbidity and cervical cancer screening: a retrospective population‐based case–cohort study. C Open. 2020;8(1):E134‐E141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Solmi M, Firth J, Miola A, et al. Disparities in cancer screening in people with mental illness across the world versus the general population: prevalence and comparative meta‐analysis including 4 717 839 people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(1):52‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kisely S, Crowe E, Lawrence D. Cancer‐related mortality in people with mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(2):209‐217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nielsen RE, Kugathasan P, Straszek S, Jensen SE, Licht RW. Why are somatic diseases in bipolar disorder insufficiently treated? Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dipasquale S, Pariante CM, Dazzan P, Aguglia E, McGuire P, Mondelli V. The dietary pattern of patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(2):197‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch FB, et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a global systematic review and meta‐analysis. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):308‐315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Prochaska JJ, Das S, Young‐Wolff KC. Smoking, mental illness, and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:165‐185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sharma R, Gartner CE, Hall WD. The challenge of reducing smoking in people with serious mental illness. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(10):835‐844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sánchez Autet M, Garriga M, Zamora FJ, et al. Screening of alcohol use disorders in psychiatric outpatients: influence of gender, age, and psychiatric diagnosis. Adicciones. 2017;30(4):251‐263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Madhusoodanan S, Ting MB, Farah T, Ugur U. Psychiatric aspects of brain tumors: a review. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(3):273‐285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gao X, Mi Y, Guo N, et al. Glioma in schizophrenia: is the risk higher or lower? Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pacelli B, Carretta E, Spadea T, et al. Does breast cancer screening level health inequalities out? A population‐based study in an Italian region. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(2):280‐285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Berardi D, Ferrannini L, Menchetti M, Vaggi M. Primary care psychiatry in Italy. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(6):460‐463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tosh G, Clifton AV, Xia J, White MM. General physical health advice for people with serious mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(3):CD008567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chou FHC, Tsai KY, Wu HC, Shen SP. Cancer in patients with schizophrenia: what is the next step? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70(11):473‐488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Irwin KE, Henderson DC, Knight HP, Pirl WF. Cancer care for individuals with schizophrenia. Cancer. 2014;120(3):323‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Table S2

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.