Abstract

Objective

To develop contemporary and inclusive prostate cancer survivorship guidelines for the Australian setting.

Participants and Methods

A four‐round iterative policy Delphi was used, with a 47‐member expert panel that included leaders from key Australian and New Zealand clinical and community groups and consumers from diverse backgrounds, including LGBTQIA people and those from regional, rural and urban settings. The first three rounds were undertaken using an online survey (94–96% response) followed by a fourth final face‐to‐face panel meeting. Descriptors for men’s current prostate cancer survivorship experience were generated, along with survivorship elements that were assessed for importance and feasibility. From these, survivorship domains were generated for consideration.

Results

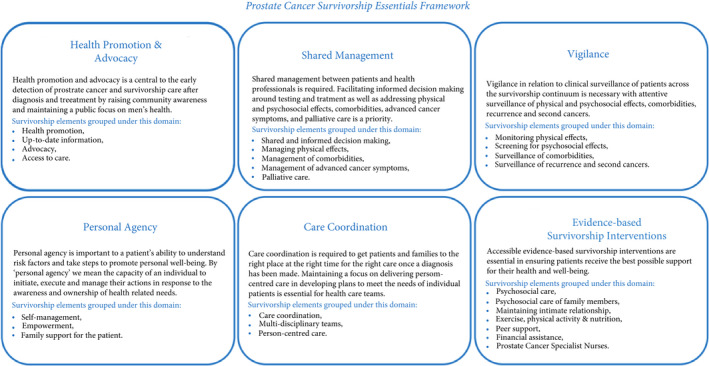

Six key descriptors for men’s current prostate cancer survivorship experience that emerged were: dealing with side effects; challenging; medically focused; uncoordinated; unmet needs; and anxious. In all, 26 survivorship elements were identified within six domains: health promotion and advocacy; shared management; vigilance; personal agency; care coordination; and evidence‐based survivorship interventions. Consensus was high for all domains as being essential. All elements were rated high on importance but consensus was mixed for feasibility. Seven priorities were derived for immediate action.

Conclusion

The policy Delphi allowed a uniquely inclusive expert clinical and community group to develop prostate cancer survivorship domains that extend beyond traditional healthcare parameters. These domains provide guidance for policymakers, clinicians, community and consumers on what is essential for step change in prostate cancer survivorship outcomes.

Keywords: prostate cancer, survivorship, quality of life, implementation, #PCSM, #ProstateCancer

Introduction

In 2018 over 1.2 million men were diagnosed with prostate cancer globally, with overall incidence expected to increase a further 42% by 2030 [1]. As incidence rises, advances in detection and treatment have led to improved survival rates in many countries, with Australia reporting 90.6% 10‐year survival [2], the USA 98% [3], and the UK 84% [4]. Hence the prevalence of prostate cancer continues to rise: in Australia, more than 200 000 men are living with a previous diagnosis [2, 5]; 3 000 000 in the USA [6, 7], and over 300 000 men in the UK [8]. Problematically, after diagnosis and treatment many men (up to 40%) experience poorer quality of life and satisfaction with life over the long term (10 years) [9] and, even with localized disease, one in five men will experience persistent anxiety and depression 1 year after treatment [10], with distress greater in men with advanced disease [11]. Poorer long‐term outcomes are associated with androgen deprivation therapy, multiple comorbidities, younger age at diagnosis, and socio‐economic disadvantage [9]. Survivorship care that seeks to enhance health and well‐being outcomes over both the short and longer term is therefore crucial for this patient group.

Limitations of existing survivorship guidelines include an over‐reliance on expert opinion [12, 13], invisibility of the consumer voice [14, 15], a lack of translation into policy and practice [16], and, in the case of prostate cancer survivorship, gaps in knowledge [17]. Perspectives about masculinity and men’s health are notably absent [18]. Recent commentary proposes that survivorship care for men with prostate cancer needs to take into account unique disease‐specific factors, both clinical and biological, as well as the subjective patient experience [12]. Given the increasing burden of prostate cancer and the lack of clear progress in the development, acceptance and delivery of quality prostate cancer survivorship care, a different approach is needed that connects current evidence, expert opinion and consumer perspectives.

The Delphi technique is a widely used method that seeks to forecast and elicit informed expert opinion and consensus in a structured and iterative approach. In health, the Delphi method has been used to develop the following: health system performance, prescribing and disease indicators [19]; clinical models of care [20, 21]; patient outcome measure sets [22]; and cancer survivorship classifications [23]. The policy Delphi [24] is appropriate for complex health policy issues and uses panel participants with a range of potentially different perspectives who are well informed and have a vested interest in the issue at hand, and specifically considers feasibility as well as importance [20, 25]. This method is cost‐effective as it does not require multiple and ongoing committee meetings, avoids constraining committee processes and, through expert involvement, sets a platform for dissemination [26]. Accordingly, we undertook a policy Delphi to describe the current state of prostate cancer survivorship in Australia and New Zealand and identify survivorship domains and domain elements for inclusion in care guidelines taking into account evidence, importance, feasibility and consensus.

Participants and Methods

Participants

Using purposive sampling through consultation with leading Australian (n = 46) and New Zealand (n = 1) clinical and community groups we identified 47 potential panel members who were leaders in the field with recognized authority in prostate cancer and survivorship care or who were able to represent the experiences of men with prostate cancer. Australian participants spanned six jurisdictions (New South Wales, n = 18; Queensland, n = 8; Victoria, n = 8; South Australia, n = 7; Western Australia, n = 3; and the Australian Capital Territory, n = 2). All of those invited agreed to participate. The panel included 31 nationally leading clinical, allied health, nursing and academic and community leaders and 16 consumers who had experience in the provision of support in the community (Table 1) from a range of professional and academic organizations (Table 2). Representatives from indigenous health, the LGBTIQ community, rural and regional as well as urban consumers, and partners of men with prostate cancer were included. Health professional and academic leaders had between 15 and 40 years of experience with prostate cancer, and, for men, their time since diagnosis ranged from 6 to 20 years (Table 1). Sample sizes for policy Delphi range from 10 to 30, with a maximum of 50 considered appropriate [25, 26].

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Demographic characteristics | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–44 years | 13 (6) |

| 45–54 years | 19 (9) |

| 55–64 years | 26 (12) |

| 65–74 years | 36 (17) |

| 75–84 years | 4 (2) |

| 85+ years | 2 (1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 66 (31) |

| Female | 34 (16) |

| Role* | |

| Health professionals | |

| Urologist | 4 (2) |

| Medical oncologist | 6 (3) |

| Radiation oncologist | 4 (2) |

| General practitioner | 4 (2) |

| Physiotherapist | 2 (1) |

| Exercise physiologist | 6 (3) |

| Registered nurse | 9 (4) |

| Other (health professional) | 19 (9) |

| Consumers | |

| Patients | 30 (15) |

| Partners | 8 (4) |

| Family of survivors | 4 (2) |

| Time since diagnosis for survivors, years | Mean (range) |

| Patients | 12 (6–20) |

| Partners | 15 (9–23) |

| Health professional and academic leaders experience, years | 16 (15–40) |

Some participants were health professionals who also have or had had prostate cancer, therefore, numbers do not add up to 47.

Table 2.

Panel member organizational affiliations.

|

Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate Cancer Trials Group Australia and New Zealand Urological Nurses Society Australian Prostate Centre Cancer Council Australia Queensland Cancer Occupational Therapy Interest Group Cancer Voices New South Wales Centre for Research Excellence in Prostate Cancer Survivorship Exercise and Sports Science Australia Flinders Centre for Innovation in Cancer Healthy Male Macquarie Health Medical Oncology Group of Australia Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre Primary Care Collaborative Cancer Clinical Trials Group Prost! Exercise Group Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia Prostate Cancer Foundation of New Zealand Psychology Board of Australia Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand Regional and Major Urban Prostate Cancer Support Group Leadership |

Procedure

A four‐round policy Delphi was undertaken between 9 September 2019 and 20 February 2020, with ethical approval from the University of Technology Sydney (Approval #ETH19‐3855). The first three rounds were administered using the QualtricsXM survey platform, with the final round conducted at a face‐to‐face meeting. Each survey was pilot‐tested in advance and revised as needed. Survey response rates were 96% (n = 45) for the first survey round, 96% (n = 45) for the second round and 94% (n = 44) for the third round, and 28 panel members attended the face‐to‐face meeting. In Round 1, 47 people replied but only 45 had complete data. After Round 1, one of the expert panel members withdrew from the project owing to a role change.

The purpose of Round 1 was generation of ideas and views about prostate cancer survivorship. Open‐ended questions invited respondents to list three words describing the current survivorship experience for men diagnosed with prostate cancer and then to outline what domains they viewed as essential for prostate cancer survivorship care. To stimulate participant reflection, full‐text article links to the ASCO prostate cancer survivorship guidelines [13] and recently proposed domains for a Cancer Survivorship Care Framework [16] were provided.

In Round 2 a synthesized list of descriptors for the prostate cancer survivorship experience generated in Round 1 were provided for panel members to choose up to five words that most closely represented men’s current experience. Next, participants were asked to rate the survivorship care elements synthesized from Round 1 for importance and feasibility (1 – not important at all, to 7 – extremely important; 1 – not feasible at all, to 7 – extremely feasible). Importance was defined as the degree to which a survivorship element is of significance or value to improving prostate cancer survivorship care. Feasibility was the degree to which a survivorship element can be achieved, performed or implemented.

In Round 3 the survivorship elements from the previous rounds were thematically analysed to derive survivorship domains for the panel to consider the extent to which each domain should be included in prostate cancer survivorship guidelines (1 – not at all, to 7 – absolutely). For each domain, an open‐ended question invited further commentary and suggestions for missing elements.

For Round 4, at a 1‐day face‐to‐face meeting, participants reviewed the evidence for intervention for each survivorship domain through pre‐reading and discussion of relevant systematic literature reviews [17], consumer perspectives [14], and a series of expert presentations. Participants were assigned to groups for each of the survivorship domains, each group was then asked to identify priority actions for change, and to consider feasibility of change in their designated domain to improve the survivorship experience in prostate cancer. Each group reported back to the other expert panel members on their identified priority actions. The expert panel members and two clinician‐researchers (A.K., M.F.) were then given 10 votes each to vote on the top priority actions to target for change to inform future implementation. The top priorities for action were determined by the priority actions that received over 50% of the combined votes.

Analysis

Data from each round were considered verbatim and then underwent independent content and thematic analysis by three authors (J.D., A.G., S.K.C.), followed by discussion and consensus to provide synthesized data for the panel to consider in subsequent rounds. There are no universally accepted rules for consensus in the Delphi method. In the present study we determined the direction of consensus on seven‐point rating scales using score categories of 6–7 as highly important/feasible/essential, 5 as moderately important/feasible/essential, 4 as neutral; 3 as less important/feasible/essential, and 1–2 as not important/feasible/essential [27]. The direction of consensus was defined as the proportion of agreement in either one agreement category (e.g. ‘highly important’), or across two contiguous categories according to the consensus rule [27] (e.g. ‘highly important’ and ‘moderately important’). The consensus rule was: high consensus – 70% in one agreement category or 80% in two contiguous categories; moderate consensus – 60% in one agreement category or 70% in two contiguous categories; low consensus – 50% in one agreement category or 60% in two contiguous categories; and no consensus – less than 50% in one agreement category or less than 60% in two contiguous categories [27, 28].

Results

Experience of Prostate Cancer Survivorship

Round 1 elicited 135 words or phrases to describe the prostate cancer survivorship experience from which 30 unique words/phrases were identified. Of these, 18 were negative, four neutral, and eight positive. In Round 2, the top six words endorsed by at least 25% of the panel as best describing men’s current prostate cancer survivorship experience were: dealing with side effects; challenging; medically focused; uncoordinated; unmet needs; and anxious (Table 3).

Table 3.

Endorsement of prostate cancer survivorship descriptors.

| Descriptors | Endorsement % (n) |

|---|---|

| Dealing with side effects | 78 (35) |

| Challenging | 38 (17) |

| Medically focused | 33 (15) |

| Uncoordinated | 29 (13) |

| Unmet needs | 29 (13) |

| Anxious | 27 (12) |

| Emotional | 24 (11) |

| Family relationships | 22 (10) |

| Variable | 20 (9) |

| Surveillance | 18 (8) |

| Optimistic | 18 (8) |

| Resilience | 18 (8) |

| Mostly ok | 18 (8) |

| Decision‐making | 16 (7) |

| Well‐being | 13 (6) |

| Confusing | 13 (6) |

| Resigned | 11 (5) |

| Distressing | 11 (5) |

| Living | 11 (5) |

| Relief | 9 (4) |

| Learning | 9 (4) |

| Positive | 7 (3) |

| Transformative | 7 (3) |

| Regret | 7 (3) |

| Burdensome | 4 (2) |

| Poor | 2 (1) |

| Isolating | 2 (1) |

| Helping | 0 (1) |

| Diminished | 0 (1) |

| Lifelong | 0 (1) |

Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Elements and Domains

In Round 1, participants described 310 elements of care that were synthesized through content analysis to produce 26 unique prostate cancer survivorship elements. In Round 2, most items were rated as very important with high consensus (22 items) and the remaining four items were very important to important with high consensus (Table 4). For feasibility, six items were rated as very feasible to moderately feasible with high consensus, three items as very feasible to moderately feasible with moderate consensus and the remaining 17 had either no [5] or low [12] consensus (Table 5). Through thematic analysis [29] and data consolidation [30] of these items, six domains of survivorship care were elicited: health promotion and advocacy; shared management; vigilance; personal agency; care coordination and evidence‐based survivorship interventions (see Appendix 1 for domain definitions).

Table 4.

Frequency (%) of response regarding the degree to which each element of survivorship is important (Round 2; N = 45).

| Consensus (direction) |

Very important (6–7) n (%) |

Moderately important (5) n (%) |

Neutral (4) N (%) |

Less important (3) n (%) |

Not important (1–2) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management of advanced symptoms | High (VI) | 45 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Access to care | High (VI) | 45 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Palliative care | High (VI) | 44 (97.8) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multidisciplinary teams | High (VI) | 43 (95.6) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Managing physical effects | High (VI) | 43 (95.6) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Psychosocial care | High (VI) | 42 (93.3) | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Up‐to‐date information | High (VI) | 42 (93.3) | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Surveillance of recurrence and second cancers | High (VI) | 42 (93.3) | 2 (4.4) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Care coordination | High (VI) | 42 (93.3) | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Shared and informed decision | High (VI) | 41 (91.1) | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Person‐centred care | High (VI) | 41 (91.1) | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Family support for the patient | High (VI) | 41 (91.1) | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Prostate cancer specialist nurses | High (VI) | 40 (88.9) | 5 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Monitoring physical effects | High (VI) | 39 (86.7) | 4 (8.9) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Exercise, physical activity and nutrition | High (VI) | 39 (86.7) | 5 (11.1) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Health promotion | High (VI) | 39 (86.7) | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) |

| Screening for psychosocial effects | High (VI) | 39 (86.7) | 5 (11.1) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Self‐management | High (VI) | 39 (86.7) | 4 (8.9) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Management of comorbidities | High (VI) | 38 (84.4) | 5 (11.1) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) |

| Maintaining intimate relationships | High (VI) | 38 (84.4) | 7 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Advocacy | High (VI) | 37 (82.2) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Surveillance of comorbidities | High (VI) | 37 (82.2) | 7 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Empowerment | High (VI‐MI) | 35 (77.8) | 8 (17.8) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Psychosocial care of family members | High (VI‐MI) | 30 (66.7) | 13 (28.9) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Financial assistance | High (VI‐MI) | 28 (62.2) | 9 (20.0) | 6 (13.3) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Peer support | High (VI‐MI) | 27 (60.0) | 12 (26.7) | 6 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

MI, moderately important; VI, very important.

Table 5.

Frequency (%) of response regarding the degree to which element of survivorship is feasible (Round 2; N = 45).

| Consensus (direction) |

Very feasible (6–7) n (%) |

Moderately feasible (5) n (%) |

Neutral (4) n (%) |

Less feasible (3) n (%) |

Not feasible (1–2) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveillance of recurrence and second cancers | High (VF‐MF) | 32 (71.1) | 8 (17.8) | 3 (6.7) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Up‐to‐date information | High (VF‐MF) | 27 (60.0) | 11 (24.4) | 5 (11.1) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Monitoring physical effects | High (VF‐MF) | 26 (57.8) | 15 (33.3) | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Management of advanced symptoms | High (VF‐MF) | 25 (55.6) | 15 (33.3) | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) |

| Palliative care | High (VF‐MF) | 22 (48.9) | 15 (33.3) | 6 (13.3) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Advocacy | High (VF‐MF) | 20 (44.4) | 16 (35.6) | 4 (8.9) | 4 (8.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| Health promotion | Moderate (VF‐MF) | 19 (42.2) | 14 (31.1) | 8 (17.8) | 2 (4.4) | 2 (4.4) |

| Exercise, physical activity and nutrition | Low (VF‐MF) | 18 (40.0) | 12 (26.7) | 8 (17.8) | 4 (8.9) | 3 (6.7) |

| Family support for the patient | Low (VF‐MF) | 18 (40.0) | 13 (28.9) | 9 (20.0) | 2 (4.4) | 3 (6.7) |

| Shared and informed decision | Low (VF‐MF) | 17 (37.8) | 12 (26.7) | 11 (24.4) | 5 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Prostate cancer specialist nurses | Low (VF‐MF) | 17 (37.8) | 10 (22.2) | 9 (20.0) | 9 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Screening for psychosocial effects | Low (VF‐MF) | 17 (37.8) | 10 (22.2) | 12 (26.7) | 4 (8.9) | 2 (4.4) |

| Surveillance of comorbidities | Moderate (VF‐MF) | 16 (35.6) | 17 (37.8) | 8 (17.8) | 4 (8.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Peer support | Low (MF‐N) | 15 (33.3) | 10 (22.2) | 16 (35.6) | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.2) |

| Management of comorbidities | Low (VF‐MF) | 15 (33.3) | 13 (28.9) | 10 (22.2) | 4 (8.9) | 3 (6.7) |

| Empowerment | Low (VF‐MF) | 15 (33.3) | 12 (26.7) | 11 (24.4) | 4 (8.9) | 3 (6.7) |

| Person‐centred care | Low (VF‐MF) | 13 (28.9) | 18 (40.0) | 10 (22.2) | 4 (8.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Managing physical effects | Moderate (VF‐MF) | 13 (28.9) | 22 (48.9) | 7 (15.6) | 2 (4.4) | 1 (2.2) |

| Multidisciplinary teams | Low (MF‐N) | 12 (26.7) | 14 (31.1) | 15 (33.3) | 2 (4.4) | 2 (4.4) |

| Psychosocial care | Low (MF‐N) | 11 (24.4) | 18 (40.0) | 13 (28.9) | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Self‐management | Low (VF‐N) | 10 (22.2) | 18 (40.0) | 10 (22.2) | 6 (13.3) | 1 (2.2) |

| Care coordination | None (MF‐N) | 10 (22.2) | 13 (28.9) | 15 (33.3) | 6 (13.3) | 1 (2.2) |

| Maintaining intimate relationships | None (MF‐N) | 9 (20.0) | 12 (26.7) | 12 (26.7) | 7 (15.6) | 5 (11.1) |

| Access to care | None (MF‐N) | 8 (17.8) | 17 (37.8) | 14 (31.1) | 5 (11.1) | 1 (2.2) |

| Psychosocial care of family members | None (N‐LF) | 5 (11.1) | 8 (17.8) | 17 (37.8) | 12 (26.7) | 3 (6.7) |

| Financial assistance | None (N‐LF) | 1 (2.2) | 8 (17.8) | 15 (33.3) | 14 (31.1) | 7 (15.6) |

LF, Less feasible; MF, moderately feasible; N, neutral; VF, very feasible.

In Round 3, participants rated all six domains as very important with high consensus (Table 6). In Round 4, participants identified 31 priority actions for change across the six domains of survivorship care (Table 7). Participants then cast a total of 293 votes to identify the top priority actions to target for change. Seven priorities for action received over half of the combined votes (n = 163). These top priority actions were: a patient communication kit for health professionals; a ‘My Journey Kit’ from diagnosis for patients; alternative delivery models to improve access; advocacy for Medicare Benefit Schedule (Commonwealth) payments for care programmes; exercise as an avenue for personal agency; better use of technology; and innovative models for specialist nurses (Table 8).

Table 6.

Frequency (%) of response regarding the degree to which each survival domain is essential (Round 3; N = 44).

| Consensus (Direction) |

Very essential (6–7) n (%) |

Moderately essential (5) n (%) |

Neutral (4) n (%) |

Less essential (3) n (%) |

Not Essential (1–2) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health promotion and advocacy | High (VE) | 39 (88.6) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) |

| Shared management | High (VE) | 41 (93.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Vigilance | High (VE) | 37 (84.1) | 5 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Personal agency | High (VE) | 41 (93.2) | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Care coordination | High (VE) | 42 (95.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) |

| Evidence‐based survivorship interventions | High (VE) | 43 (97.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

VE, very essential.

Table 7.

Priority actions for change in each domain (N = 31; Round 4).

| Health promotion and advocacy | Shared management | Vigilance | Personal agency | Care coordination | Evidence‐based survivorship interventions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priority action | Votes | Priority action | Votes | Priority action | Votes | Priority action | Votes | Priority action | Votes | Priority action | Votes |

| Advocacy for MBS payment for care programmes | 20 | Better use of technology | 19 | Define vigilance best practice for each patient group | 9 | Exercise as an avenue for personal agency | 20 | Alternative delivery models to improve access | 22 | Patient communication kit for health professionals | 32 |

| Innovative models for specialist nurses | 18 | Use of community nurses/teams | 13 | Advocate for PBS support for surveillance tools | 8 | Health professional role | 8 | Define care coordination | 13 | ‘My Journey Kit’ from diagnosis for patients | 32 |

| Health professional education in health promotion | 11 | Knowledge and information for patients, partners, family members and friends | 7 | Vigilance pathways for health professionals | 1 | Peer support | 7 | Patient‐centred | 6 | Communicating information about interventions | 3 |

| Australian online resources to connect people to local services | 11 | Improved health communication | 4 | Adaptability to changing circumstances | 2 | Improved communication | 4 | ||||

| Empowering consumers to communicate | 5 | Resources on side effects | 4 | Information dissemination | 2 | Team‐based care delivery | 1 | ||||

| Engage partners, family members and friends to promote healthy choices | 4 | Health professional education on appropriate communication | 0 | Addressing personal attitudes through diverse avenues for support | 2 | ||||||

| Continuous monitoring of consumer needs | 2 | ||||||||||

| High profile policy advocates | 3 | ||||||||||

MBS, the Medicare Benefits Schedule is a list of Medicare services subsidized by the Australian Government; PBS, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme provides medicines to patients at a Government‐subsidized price.

Table 8.

Overall ranking of priority actions for change (Round 4).

| Priority actions | Votes |

|---|---|

| Patient communication kit for health professionals | 32 |

| ‘My Journey Kit’ from diagnosis for patients | 32 |

| Alternative delivery models to improve access | 22 |

| Advocacy for MBS payment for care programmes | 20 |

| Exercise as an avenue for personal agency | 20 |

| Better use of technology | 19 |

| Innovative models for specialist nurses | 18 |

| Define care coordination | 13 |

| Use of community nurses/teams | 13 |

| Health professional education in health promotion | 11 |

| Australian online resources to connect people to local services | 11 |

| Define vigilance best practice for each patient group | 9 |

| Advocate for PBS support for surveillance tools | 8 |

| Health professional role | 8 |

| Peer support | 7 |

| Knowledge and information for patients, partners, family members and friends | 7 |

| Patient‐centred | 6 |

| Empowering consumers to communicate | 5 |

| Engage partners, family members and friends to promote healthy choices | 4 |

| Improved communication | 4 |

| Improved health communication | 4 |

| Resources on side effects | 4 |

| High profile policy advocates | 3 |

| Communicating information about interventions | 3 |

| Continuous monitoring of consumer needs | 2 |

| Adaptability to changing circumstances | 2 |

| Information dissemination | 2 |

| Addressing personal attitudes through diverse avenues for support | 2 |

| Team‐based care delivery | 1 |

| Vigilance pathways for health professionals | 1 |

| Health professional education on appropriate communication | 0 |

MBS, the Medicare Benefits Schedule is a list of Medicare services subsidized by the Australian Government; PBS, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme provides medicines to patients at a Government‐subsidized price.

Discussion

Consistent with our previous research, this expert panel described the current experience of prostate cancer survivorship in Australia as medically focused, not well coordinated and challenging, exacerbating the difficulty of treatment side effects and leading to unmet needs and anxiety [14, 21]. The burden of prostate cancer in the individual has been well described, with the chronic nature and prolonged natural history of this disease, along with accumulated toxicities from existing and emerging treatments, exacerbating the need for survivorship guidelines [12]. Problematically, a survivorship response from a policy, research and practice perspective has been slow to emerge and where it does exist is fragmented [31]. The present study applying the Delphi method as a policy practice planning tool uniquely presents a collective high consensus statement from the Australian and New Zealand clinical and consumer community about the essential domains for prostate cancer survivorship care. Six essential survivorship domains were identified, each with important elements (Fig. 1), to guide action not only in this context, but likely elsewhere. These domains in practice will articulate closely with each other, which we propose is a strength that mirrors the realities of life as a cancer survivor where different domains of quality of life intersect and influence long‐term physical and mental well‐being and life satisfaction [9].

Fig. 1.

Prostate cancer survivorship essentials framework.

Health Promotion and Advocacy

Health promotion and advocacy is central to the early detection of prostate cancer and survivorship care after diagnosis and treatment by raising community awareness and maintaining a public focus on men’s health. Key to this domain is the provision of up‐to‐date information to increase the Australian and New Zealand community’s knowledge of men’s health and prostate cancer. Information should be evidence‐based, providing consistent messaging around prostate cancer, and tailored to take into account health literacy and preferences for different mediums [32, 33]. Information should be targeted specifically to primary care providers and community workers along with dedicated training in men’s health promotion to work effectively with men. Advocacy is required from the non‐government sector for the effective promotion of men’s health to government and to health service providers and to engaging community support. Advocacy is also required to bring attention to the support needs of survivors and their families, including advocating for programmes around peer support and self‐management. This involves facilitating public access to information about prostate cancer, the provision of evidence‐based interventions and improving access to survivorship care for all men and their families, including those living in rural and remote areas, LGBTQIA people, indigenous people, and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds [34, 35, 36].

Shared Management

Shared management between patients and health professionals is required to improve outcomes and ensure quality survivorship care. Development of models which facilitate informed decision‐making around testing and treatment and address physical and psychosocial effects, comorbidities, advanced cancer symptoms, and palliative care is a priority [37]. Clear explanation is required that palliative care relates to the prevention and control of symptoms earlier in the survivorship journey as well as to end‐of‐life issues. Informed decision‐making involves access to decision aids to facilitate understanding of treatment options, side effects and associated financial costs, as well as open communication and delivery of consistent information. Shared management extends to respecting a patient’s wishes to engage in decision‐making around care to the extent they prefer, involves acknowledging and supporting the role family members and carers play, and requires access to patient records. Once shared and informed management decisions are made, these decisions should be supported by effective care coordination, with primary care providers and prostate cancer specialist nurses playing a central role as navigators [21].

Vigilance

Vigilance in relation to the clinical surveillance of patients is critical to prostate cancer survivorship. Vigilance from health professionals across the survivorship continuum from diagnosis to end‐of‐life care is necessary, with attentive surveillance of physical and psychosocial effects, comorbidities, recurrence and second cancers. This extends to monitoring psychosocial effects on partners and family members [38]. The level of vigilance should be tailored to the changing needs of patients through screening early on and then systematically over the survivorship journey. Additional sources of information to evaluate patients, including observations from partners and other family members, are important to take into account. Health professionals should take action on the outcomes of clinical surveillance as required.

Personal Agency

Personal agency enables a patient’s ability to understand risk factors and take steps to promote personal well‐being; therefore, a focus on personal agency and the ability of individual patients to be self‐aware in assessing their needs, seek assistance when required, and manage their own health is central to improving outcomes. By 'personal agency' we mean the capacity of an individual to initiate, execute and manage their actions in response to the awareness and ownership of health‐related needs. Recognizing patients as actors in building personal resilience, managing their own health and with mastery in navigating the healthcare system will lead to improved survivorship outcomes. Family members and wider social support networks also play a key role in supporting patients to achieve objectives. Patient education and knowledge should be supported by the provision of information across the spectrum of survivorship care tailored to the health literacy levels of individual patients [33]. A health professional workforce skilled in supporting personal agency is required.

Care Coordination

Care coordination is required to get patients and families to the right place at the right time for the right care once a diagnosis has been made [39]. Care coordination in consultation with patients and families is critical to survivorship outcomes. Clinical teams, primary care clinicians, nurses and allied health professionals, as well as community‐based health and welfare services, should all be active participants. This requires systems to support the sharing of relevant patient information between healthcare teams, and referral to community‐based peer support groups where required. Underlying care coordination is the need for healthcare teams to maintain a focus on delivering person‐centred care in developing plans to meet the needs of individual patients. This includes approaching care in a men‐centred way, acknowledging that men‐centred care is deeply contextual and dynamic, but includes a consideration of how healthcare services for men intersect with masculinity and with men’s preferences for the design and delivery of prostate cancer survivorship care [14, 18]. Specific consideration of access issues for indigenous men, those living in rural and remote areas, and men from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds is required.

Evidence‐based Survivorship Interventions

Accessible evidence‐based survivorship interventions ensure patients receive the best possible support for their health and well‐being. Key evidence‐based survivorship interventions include psychosocial care, exercise and physical activity, nutrition, peer support, financial assistance, and prostate cancer specialist nurses. It is important that psychosocial care interventions to maintain intimate relationships comprise sexual health support tailored to individual men including those in different age groups and from LGBTQIA backgrounds.

Feasibility, Priorities and Limitations

It is not surprising that, while experts reached consensus about the domains and elements of prostate cancer survivorship and their importance, there was low consensus around feasibility. The extent to which a survivorship intervention element can be implemented will depend on the healthcare, social and community systems in which each individual man exists, as well as his own and his family’s personal preferences. Healthcare inequities are widespread in almost all societies globally, not only in Australia, and men’s healthcare outcomes have specific challenges that are seldom addressed in mainstream healthcare delivery [32]. In response, our expert panel identified seven priority actions as a practical platform for change. Action on each priority can be expected to have an impact for men across the six survivorship domains, and cumulatively could make a measurable difference in the face of prostate cancer in this country.

A limitation of this study is the Australian and New Zealand setting, such that this framework may not generalize to countries with markedly different cultural and health system characteristics. However, we would argue that a workable survivorship model requires this level of specificity and local ownership and knowledge. Additionally, a number of the participants in this Delphi study held leadership positions in support groups in their community. Although these participants had deep community understanding and awareness of survivorship issues facing men with prostate cancer, their views may not be representative of all men with prostate cancer. Most importantly, the high participation and response rates we report are evidence of rigour in our approach and of the commitment of clinicians and community to work together in novel ways to improve outcomes for men with prostate cancer.

In conclusion, the policy Delphi provided a mechanism to form a uniquely inclusive expert clinical and community group from which a set of prostate cancer survivorship domains were developed that extend beyond traditional healthcare parameters. Guidance that spans personal agency, health promotion and advocacy, shared management, care coordination, evidence‐based interventions, across to a shared vigilance between the patient and the clinician, is a new way of thinking about care. Each of these domains intersects or articulates with each other and this mirrors both the patient experience and how services operate at their best. New ways of thinking will be needed as the healthcare burden of our aging population grows, and as technological innovations in personalized medicine emerge, with their attendant costs and benefits [40, 41, 42]. New partnerships across disciplines that include consumers are needed in order to respond to these challenges, as well as to facilitate implementation [43]. This study establishes these partnerships for prostate cancer survivorship and provides a model for consideration in cancer more broadly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Prostate Cancer Survivorship (APP1098042), Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia, and Gandel Philanthropy.

Appendix 1.

Prostate cancer survivorship essential domain names, elements and definitions

| Domain name | Domain elements | Domain definition |

|---|---|---|

| Health promotion and advocacy |

|

Health promotion and advocacy is central to the early detection of prostate cancer and survivorship care after diagnosis and treatment by raising community awareness and maintaining a public focus on men’s health. Key to this domain is the provision of up‐to‐date information to increase the Australian community’s knowledge of men’s health and prostate cancer. It is important that up‐to‐date information is evidence‐based, provides consistent messaging around prostate cancer, and is tailored, taking into account varying levels of health literacy and preferences for different mediums. Information should also be targeted specifically to primary care providers and community workers along with dedicated training in men’s health promotion to work effectively with men. Advocacy is required from the non‐government sector for the effective promotion of men’s health to government and to health service providers and to engaging community support. Advocacy is also required to bring attention to the support needs of survivors and their families, including advocating for programmes around peer support and self‐management. ‘Making men’s health a priority’ This involves facilitating public access to up‐to‐date information, the provision of evidence‐based interventions and improving access to survivorship care for all men and their families. Including those living in rural and remote areas, from LGBTQIA and culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds |

| Shared management |

|

Once a diagnosis of prostate cancer has been made, shared management between patients and health professionals is required to improve outcomes and ensure quality survivorship care. Developing models of shared management to facilitate informed decision‐making around testing and treatment, as well as addressing physical and psychosocial effects, comorbidities, advanced cancer symptoms, and palliative care, is a priority. Clear explanation that palliative care not only relates to end‐of‐life issues but also that the prevention and control of symptoms earlier in the survivorship journey is required. Informed decision‐making that includes health professional and patient access to decision aids to facilitate understanding of treatment options and side effects, associated financial costs, as well as open communication and delivery of consistent information, is important. Shared management extends to respecting a patient’s wishes to engage in decision‐making around care to the extent they prefer. It is important for health professionals to acknowledge the role family members and carers play in shared management for some patients and support their involvement. ‘Fully informed decision‐making’ Health professional access to patient records is important to informing shared management. Once shared and informed management decisions are made by patients and health professionals, these decisions should be supported by effective care coordination, with primary care providers and prostate cancer specialist nurses playing a central role as navigators |

| Vigilance |

|

Vigilance in relation to clinical surveillance of patients is critical to prostate cancer survivorship. Vigilance from health professionals across the survivorship continuum from diagnosis to end‐of‐life care is necessary with attentive surveillance of physical and psychosocial effects, comorbidities, recurrence and second cancers. Health professionals’ vigilance is important in monitoring psychosocial effects on the partners and family members of patients. The level of vigilance should be tailored to the changing needs of patients through screening early on and then systematically over the survivorship journey. Additional sources of information to evaluate patients, including observations from partners and other family members, are important to take into account. ‘Surveillance of recurrence is very important and gives you hope as you survive your journey’ Vigilance includes health professionals taking action on the outcomes of clinical surveillance as required |

| Personal agency |

|

Personal agency is important to a patient’s ability to understand risk factors and take steps to promote personal well‐being. Therefore, a focus on personal agency and the ability of individual patients to be self‐aware in assessing their needs, seek assistance when required, and manage their own health is central to improving outcomes. Family members and wider social support networks play a role in building personal agency and supporting patients to achieve objectives By 'personal agency' we mean the capacity of an individual to initiate, execute and manage their actions in response to the awareness and ownership of health‐related needs. Recognizing ‘patients as actors’ in building personal resilience, in managing their own health and with mastery in navigating the healthcare system will lead to improved survivorship outcomes. Patient education and knowledge enables personal agency and should be supported by the provision of information across the spectrum of survivorship care tailored to the health literacy levels of individual patients. A health professional workforce skilled in supporting the personal agency of patients is important ‘Survivors should be encouraged to assess their own needs, learn how and where to seek assistance…and what questions they should be asking of health professionals’ |

| Care coordination |

|

Care coordination is required to get patients and families to the right place at the right time for the right care once a diagnosis has been made. ‘Guidance navigating the health system’ Care coordination in consultation with patients and families is critical to survivorship outcomes. Clinical teams, primary care clinicians, nurses and allied health professionals as well as community‐based health and welfare services should all be active participants in Care coordination. This requires systems to support the sharing of relevant patient information between healthcare teams, and referral to community‐based peer support groups where required. ‘A central healthcare professional connecting all the services, appointments and treatments’ Underlying care coordination is the need for healthcare teams to maintain a focus on delivering person‐centred care in developing plans to meet the needs of individual patients. This includes approaching care in a men‐centred way, acknowledging that men‐centred care is deeply contextual and dynamic but includes a consideration of how healthcare services for men intersect with masculinity and in the context of this study with men’s preferences for the design and delivery of prostate cancer survivorship care. Specific consideration of access issues to care coordination for men living in rural and remote areas and men from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds is required. ‘Whole of person care…creation of personal packages’ |

| Evidence‐based survivorship interventions |

|

Accessible evidence‐based survivorship interventions are essential in ensuring patients receive the best possible support for their health and well‐being. Key evidence‐based survivorship interventions include psychosocial care, exercise and physical activity, nutrition, peer support, financial assistance, and prostate cancer specialist nurses. ‘Management of a well‐planned exercise programme to meet your needs is a great help, and makes you feel good about yourself’ Psychosocial care interventions to maintain intimate relationships that include sexual health support tailored to individual men including those in different age groups and from LGBTQIA backgrounds are important |

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 394–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cancer Australia . 10‐year relative survival [Web Page]. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government, 2020. Available at: https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/outcomes/relative‐survival‐rate/10‐year‐relative‐survival. Accessed April 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Cancer Society . Survival Rates for Prostate Cancer [Web Page]. American Cancer Society, 2019. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate‐cancer/detection‐diagnosis‐staging/survival‐rates.html. Accessed February 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cancer Research UK . Prostate Cancer Survival Statistics. Cancer Research UK, 2019. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health‐professional/cancer‐statistics/statistics‐by‐cancer‐type/prostate‐cancer/survival#heading‐Two. Accessed February 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yu XQ, Smith DP, Clements MS, Patel MI, McHugh B, Connell DL. Projecting prevalence by stage of care for prostate cancer and estimating future health service needs: protocol for a modelling study. BMJ Open 2011; 1: e000104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016; 66: 271–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2013; 22: 561–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service . The Macmillan‐NCRAS UK Cancer Prevalence Project, 2019. Available at: http://www.ncin.org.uk/about_ncin/segmentation. Accessed April 2020

- 9. Ralph N, Ng SK, Zajdlewicz L et al. Ten‐year quality of life outcomes in men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2020; 29: 444–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Occhipinti S, Zajdlewicz L, Coughlin GD et al. A prospective study of psychological distress after prostate cancer surgery. Psychooncology 2019; 28: 2389–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zajdlewicz L, Hyde MK, Lepore SJ, Gardiner RA, Chambers SK. Health‐related quality of life after the diagnosis of locally advanced or advanced prostate cancer: a longitudinal study. Cancer Nurs 2017; 40: 412–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Narayan V, Harrison M, Cheng H et al. Improving research for prostate cancer survivorship: A statement from the Survivorship Research in Prostate Cancer (SuRECaP) working group. Urol Oncol. 2020; 38: 83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Skolarus TA, Wolf AMD, Erb NL et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64: 225–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dunn J, Ralph N, Green A, Frydenberg M, Chambers S. Contemporary consumer perspectives on prostate cancer survivorship: fifty voices. Psychooncology 2020; 29: 557–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Armstrong MJ, Bloom JA. Patient involvement in guidelines is poor five years after institute of medicine standards: review of guideline methodologies. Res Involv Engagem 2017; 3: 19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, Mayer DK, Shulman LN, Geiger AM. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019; 111: 1120–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crawford‐Williams F, March S, Goodwin BC et al. Interventions for prostate cancer survivorship: a systematic review of reviews. Psychooncology 2018; 27: 2339–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chambers SK, Hyde MK, Zajdlewicz L et al. Measuring masculinity in the context of chronic disease. Psychol Men Masc 2015; 17: 228–42 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One 2011; 6: e20476‐e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meskell P, Murphy K, Shaw DG, Casey D. Insights into the use and complexities of the policy Delphi technique. Nurse Res 2014; 21: 32–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ralph N, Green A, Sara S et al. Prostate cancer survivorship priorities for men and their partners: Delphi consensus from a nurse specialist cohort. J Clin Nurs 2020; 29: 265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD et al. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. An international modified Delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196: 1122–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geerse OP, Wynia K, Kruijer M, Schotsman MJ, Hiltermann TJN, Berendsen AJ. Health‐related problems in adult cancer survivors: development and validation of the cancer survivor core set. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25: 567–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Turoff M. The policy Delphi. In Linstone HA, Turoff M eds, The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. London: Addison‐Wesley, 1975: 81–3 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rayens MK, Hahn EJ. Building consensus using the policy Delphi method. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 2000; 1: 308–15 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Turoff M. The policy Delphi. In Linstone HA, Turoff M eds, The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Newark, NJ: New Jersey Institute of Technology, 2002: 80–96 [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Loughlin R, Kelly A. Equity in resource allocation in the Irish health service. A policy Delphi study. Health Policy 2004; 67: 271–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Loe RC. Exploring complex policy questions using the policy Delphi: a multi‐round, interactive survey method. Appl Geogr 1995; 15: 53–68 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Caracelli VJ, Greene JC. Data analysis strategies for mixed‐method evaluation designs. Educ Eval Policy Anal 1993; 15: 195–207 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skolarus TA, Wittmann D, Hawley ST. Enhancing prostate cancer survivorship care through self‐management. Urol Oncol 2017; 35: 564–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Australian Government Department of Health . National Men's Health Strategy 2020–2030. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goodwin BC, March S, Zajdlewicz L, Osbourne RH, Dunn J, Chambers SK. Health literacy and the health status of men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2018; 27: 2374–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ussher J, Perz J, Rose D et al. Threat of sexual disqualification: the consequences of erectile dysfunction and other sexual changes for gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer. Arch Sex Behav 2017; 46: 2043–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rodger JC, Supramaniam R, Gibberd AJ et al. Prostate cancer mortality outcomes and patterns of primary treatment for Aboriginal men in New South Wales, Australia. BJU Int 2015; 115: 16–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A et al. Survival of African American and non‐Hispanic white men with prostate cancer in an equal‐access health care system. Cancer 2020; 126: 1683–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nekhlyudov L, Levit L, Hurria A, Ganz PA. Patient‐centered, evidence‐based, and cost‐conscious cancer care across the continuum: translating the Institute of Medicine report into clinical practice. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64: 408–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holland J, Watson M, Dunn J. The IPOS new International Standard of Quality Cancer Care: integrating the psychosocial domain into routine care. Psycho‐Oncology 2011; 20: 677–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. NEJM Catalyst . What is care coordination? NEJM Catal 2018; 4. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0291. Accessed April 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hofman MS, Emmett L, Violet J et al. TheraP: a randomized phase 2 trial of (177) Lu‐PSMA‐617 theranostic treatment vs cabazitaxel in progressive metastatic castration‐resistant prostate cancer (Clinical Trial Protocol ANZUP 1603). BJU Int 2019; 124(Suppl 1): 5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ong WL, Koh TL, Lim Joon D et al. Prostate‐specific membrane antigen‐positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PSMA‐PET/CT)‐guided stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer: a single‐institution experience and review of the published literature. BJU Int 2019; 124(Suppl 1): 19–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ahn T, Roberts MJ, Strahan A et al. Improved lower urinary tract symptoms after robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy: implications for survivorship, treatment selection and patient counselling. BJU Int 2019; 123(Suppl 5): 47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Francke AL, Smit MC, de Veer AJE, Mistiaen P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta‐review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008; 8: 38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]