Abstract

Obesity-related cardiovascular complications are a major health problem worldwide. Overconsumption of the Western diet is a well-known culprit for the development of obesity. Although short-term weight loss through switching from a Western diet to a normal diet is known to promote metabolic improvement, its short-term effects on vascular parameters are not well characterized. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), an incretin with vasculoprotective properties, is decreased in plasma from patients who are obese. We hypothesize that obesity causes persistent vascular dysfunction in association with the downregulation of vascular glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R). Female Wistar rats were randomized into three groups: lean received a chow diet for 28 wk, obese received a Western diet for 28 wk, and reverse obese received a Western diet for 18 wk followed by 12 wk of standard chow diet. The obese group exhibited increased body weight and body mass index, whereas the reverse obese group lost weight. Weight loss failed to reverse impaired vasodilation and high systolic blood pressure in obese rats. Strikingly, our results show that obese rats exhibit decreased serum levels of GLP-1 accompanied by decreased vascular GLP-1R expression. Weight loss recovered GLP-1 serum levels, however GLP-1R expression remained downregulated. Decreased Akt phosphorylation was observed in the obese and reverse obese group, suggesting that GLP-1/Akt signaling is persistently downregulated. Our results support that GLP-1 signaling is associated with obesity-related vascular dysfunction in females, and short-term weight loss does not guarantee recovery of vascular function. This study suggests that GLP-1R may be a potential target for therapeutic intervention in obesity-related hypertension in females.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Although short-term weight loss successfully improved metabolic parameters, it failed to correct vascular dysfunction present in obese female rats. Vascular GLP-1/Akt signaling was decreased in both obese rats and those with short-term weight loss, suggesting it may be a potential target for therapeutic intervention in obesity-related persistent vascular dysfunction in obese females.

Keywords: GLP-1 receptor, hypertension, obesity, vascular dysfunction, weight loss

INTRODUCTION

Obesity has become a global epidemic with its prevalence doubling in over 70 countries around the world (1, 2). In the United States specifically, the prevalence of obesity has steadily risen from 30.5% in 1999–2000 to 42.4% in 2017–2018, and it is estimated that by 2030, 50% of Americans will be obese (3, 4). A major contributor to the rise in obesity in the United States is the consumption of a high-fat, high-carbohydrate Western diet (WD; 5–7). Human and experimental studies have demonstrated that WD-induced obesity increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD), such as hypertension (8–12).

Treatment and management of obesity include lifestyle changes, bariatric surgery, and pharmacological treatments, all with the common goal to promote weight loss. Although weight loss has been shown to improve metabolic parameters such as insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles, short-term weight loss has been linked to increases in immediate risk for coronary heart disease and stroke (13–15). This suggests that weight loss, at least in the short term, may not improve all cardiovascular disorders.

One promising pharmacological agent that has emerged in the treatment of obesity is the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist (16–19). Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone secreted by intestinal L-cells in response to ingestion of food and stimulates insulin release, slows gastric emptying, and decreases appetite, thus regulating food intake and aiding in weight loss (19, 20). GLP-1Rs are G protein-coupled receptors that are expressed in various tissues including the vasculature (20–22). GLP-1Rs have many downstream signaling molecules including activation of cAMP/PKA/ERK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, and PKC pathways (23, 24). Human studies have demonstrated that in cases of obesity, secretion of GLP-1 is attenuated in both males and females (25, 26). The blood pressure lowering effects of GLP-1 agonists have also been well documented in both human and animal models (27–29). Furthermore, hypertensive mice treated with GLP-1 agonists displayed reduced blood pressure through GLP-1 signaling in vascular endothelial cells (28). However, it is still unknown if vascular GLP-1 signaling plays a role in obesity-related vascular dysfunction.

Sex differences in the prevalence of both obesity and obesity-related CVD are now recognized (30–33). Although new evidence shows that females are more affected by obesity-related CVD, more studies are urgently needed. As a result, a female cohort was the focus of this present study. We aimed to elucidate whether vascular GLP-1 signaling is implicated in obesity-related vascular dysfunction and whether short-term weight loss affects vascular GLP-1 signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal and Dietary Protocols

Female Wistar rats acquired from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) were kept in a temperature-controlled facility under a 12-h:12-h light/dark cycle and in a temperature-controlled environment (21 ± 3°C) with 40–60% humidity. A full bottle of tap water was always available to the rats. Female rats (n = 25; 18-wk old) were randomized into three experimental groups. The lean group was fed a standard chow diet (SD; Zeigler, PA, Cat. No. 5001) consisting of 5.0% fat, 48.7% carbohydrate (3.2% sucrose), and 24.1% protein (% total energy) for 28 wk. The obese group was fed a WD (OpenSource Diets, NJ, Cat. No. D12079B) consisting of 21% fat, 50% carbohydrates (34% sucrose), and 20% protein ad libitum for 28 wk. The reverse obese group (rObese) was fed a WD for 18 wk followed by the SD for 12 wk. Following the 28-wk dietary experimental protocol, terminal experiments were performed. On the day of termination, after 10 h of fasting, body weight was obtained, and glucose was measured with an AimStrip Plus glucometer (Germaine Laboratories, San Antonio, TX). Rats were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane in 100% O2 flow. Termination was then completed with exsanguination. Thoracic aortas were removed and immediately used for vascular reactivity studies. Some thoracic aorta samples were snap-frozen for histological analysis. Mesenteric arteries and thoracic aortas were removed and stored at −80°C for further molecular experiments. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine and with respect to the National Institute of Health (NIH, Publication No. 85-23, Revised 2010) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (34).

Metabolic Parameters

Obesity in humans is typically diagnosed using various measurements such as body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio (35–38). Length (measured from tip of the nares to the anus) and abdominal circumference were recorded before terminal experiments, and BMI (bodyweight/length2) was calculated to characterize the presence of obesity. At the terminal experiments, rats were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane, and blood samples were taken directly from the heart. Samples were centrifuged at 1,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Serum samples were stored at −80°C. Serum was then used to measure levels of total triglycerides (TGs) with an enzymatic commercial kit from Pointe Scientific (Canton, MI), total cholesterol with a kit from Pointe Scientific (Canton, MI), and insulin with an ultrasensitive rat insulin ELISA kit (Crystal Chem, Downers Grove, IL), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Test

To characterize changes in insulin sensitivity after consumption of the WD, an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was performed. At 17 wk into the dietary protocol, after 10 h of fasting, rats received an intraperitoneal injection of 2 g/kg body weight of a glucose solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Blood samples were taken from tail veins immediately before (0 min) and at 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after intraperitoneal injection of the glucose solution. An AimStrip Plus glucometer (Germaine Laboratories, San Antonio, TX) was used to measure blood glucose concentrations.

Insulin Resistance Analysis

Serum collected during terminal experiments as described earlier was used to assess insulin resistance (IR) by the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR). Calculation of HOMA-IR has previously been described and is a well-characterized method to assess IR in rodents (10, 39). It is calculated using the following equation: HOMA-IR = [fasting insulin (in µU/mL)] × [fasting glucose (in mM)]/22.5 (10, 40, 41).

Direct Arterial Blood Pressure Measurements

At terminal experiments, direct arterial blood pressure was obtained, as previously described (10). Rats were anesthetized with inhalation of 2.5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen flow, placed on a warming pad maintained at 37°C, and instrumented with a 1.9 Fr SciSense pressure-volume catheter (Transonic SciScense, Inc., London, ON, Canada) in the right carotid artery for direct blood pressure, recording verified by pressure curves presented in the data acquisition system (PowerLab 4/26, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Once the catheter placement was confirmed, isoflurane was reduced to 1.5% in 100% oxygen flow. Arterial blood pressure was continuously recorded for 30 min. The systolic blood pressures, diastolic blood pressures, mean arterial blood pressures, and heart rate were processed in a data acquisition system with Chart 7 software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Pulse pressure was calculated by taking the difference between systolic and diastolic pressures for each rat.

Vascular Reactivity

Vascular reactivity studies were performed using thoracic aortas to assess how the WD affects endothelial function. The use of thoracic aortas for vascular reactivity studies has served as a reliable model in previous studies, including in hypertension research (10, 42–45). During terminal experiments, thoracic aortas were taken and placed in oxygenated Krebs buffer (130 mM NaCl, 14.9 mM NaHCO3, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.18 mM KH2PO4, 1.17 mM MgSO4, 1.56 mM CaCl2, 0.026 mM EDTA, 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.4). The perivascular fat and adventitia were removed, and the thoracic aortas were cut into 2 mm rings. The rings were mounted on a Multi-Wire Myograph System 620 M (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) for isometric tension recordings by the data acquisition system (PowerLab 8/35, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). After 30 min of equilibration in Krebs buffer, the aortic rings were gassed with 5% CO2 in 95% O2 at 37°C. To assess that the endothelium was functional, the aortic rings were exposed to 1 mM phenylephrine (PE) for contraction and then 1 mM acetylcholine (ACh) for relaxation. Aortic rings with greater than 80% relaxation with exposure to ACh were deemed functional. Concentration-response curves for ACh were performed to assess endothelium-dependent relaxation using final concentrations between 1 nM and 0.1 mM. To assess endothelium-independent relaxation, concentration-response curves for sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 1 nM–0.1 mM) were performed.

Aortic Histomorphometric Analysis

Thoracic aortas were harvested after euthanasia, weighed, and snap-frozen slowly in Tissue Tek O.C.T compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) over dry ice and then stored at −80°C. Hematoxylin and eosin staining (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was performed on transverse sections of the aortas to evaluate wall thickness. Slides were digitized using an Olympus BX53 fluorescent microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA), and high-resolution bright light digital images were captured under high-power magnifications (×4 and ×20) using an Olympus DP72 (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). As previously reported, aortas were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, MD) to determine wall thickness, lumen diameter, wall thickness to lumen ratio (WT/L), and cross-sectional area (CSA; 46). Briefly, ImageJ was used to measure the internal and external areas (Ai and Ae, respectively). The internal and external radii (Ri and Re, respectively) were calculated by the equation Ai = π × Ri2 and Ae = π × Re2. The lumen diameter was calculated using the formula diameter = 2 × Ri, and wall thickness was determined by wall thickness = Re − Ri. CSA was calculated as CSA = π (Re2 – Ri2) (46).

GLP-1 Serum ELISA

GLP-1 was measured in serum using an active GLP-1 ELISA kit (Cat. No. EFLP-35K, Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Blood samples were collected from the heart during terminal experiments and samples were centrifuged at 1,000 g for 15 min. Serum was then obtained and stored at −80°C. GLP-1 levels were normalized against known concentrations and presented at as picomolar per milliliter.

Immunofluorescent Staining for GLP-1R in Aortas

Frozen thoracic aorta cross sections were incubated at room temperature for 20 min in goat serum for blockage of nonspecific binding, followed by incubation with GLP-1R primary antibody (1:50 dilutions, sc-390774, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) in humidified chambers at 4°C overnight. After being washed in PBS, the slides were incubated with secondary antibody (1:500 dilutions, Molecular Probes secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 No. A11029, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at room temperature for 30 min in a light-sensitive humidity chamber. After incubation period, the slides were washed with PBS and counterstained with a mounting medium with Dapi (No. 1200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Replacement of the primary antibody with PBS or IgG was used as a negative control. Slides were digitalized using an Olympus BX53 fluorescent microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, MA). Fluorescence from GLP-1R was identified by color thresholding, and images were captured under high-power magnification (×20) by using an Olympus DP73 digital camera.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein content was determined in the supernatant of thoracic aortas and mesenteric arteries extracts using a commercial bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Of note for this study, thoracic aortas and mesenteric arteries were used to explore GLP-1 signaling in the vasculature. Equivalent amounts of protein (40 µg/lane) from thoracic aortas and mesenteric arteries of each experimental group were loaded and separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL), as previously described (47). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk solution in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% tween (TBST) for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the following specific primary antibodies: GLP-1R (1:2,000, sc-390774, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 48–50) and phospho-Akt (Thr308; 1:1,000, Cat. No. 9275, Cell Signaling Technology), a downstream signaling molecule of GLP-1R (51, 52). The stripped thoracic aorta membranes were then probed with GAPDH (1:5,000, Cat. No. 2118, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) as a loading control. Mesenteric artery membranes were probed with GAPDH (1:5,000, Cat. No. 2118, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and Akt (1:1,000, Cat. No. 9272, Cell Signaling Technology) as loading controls for GLP-1R and phospho-Akt, respectively (10, 53). Protein expression was detected using Lumigen enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) ultra (Lumigen, Inc., Southfield, MI). Data are presented as ratios of primary antibody expression over the respective loading control.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SE and analyzed with a Student’s two-tailed t test and ANOVAs, comparing lean versus obese, and lean versus obese versus rObese groups, respectively. The relaxation in response to ACh and SNP is expressed as a percentage of contraction induced by phenylephrine. Concentration-response curves were fitted by nonlinear regression analysis (Graph Pad Prism 4.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Maximum response (Emax) and pD2 (defined as the negative logarithm of the EC50 values) were determined. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

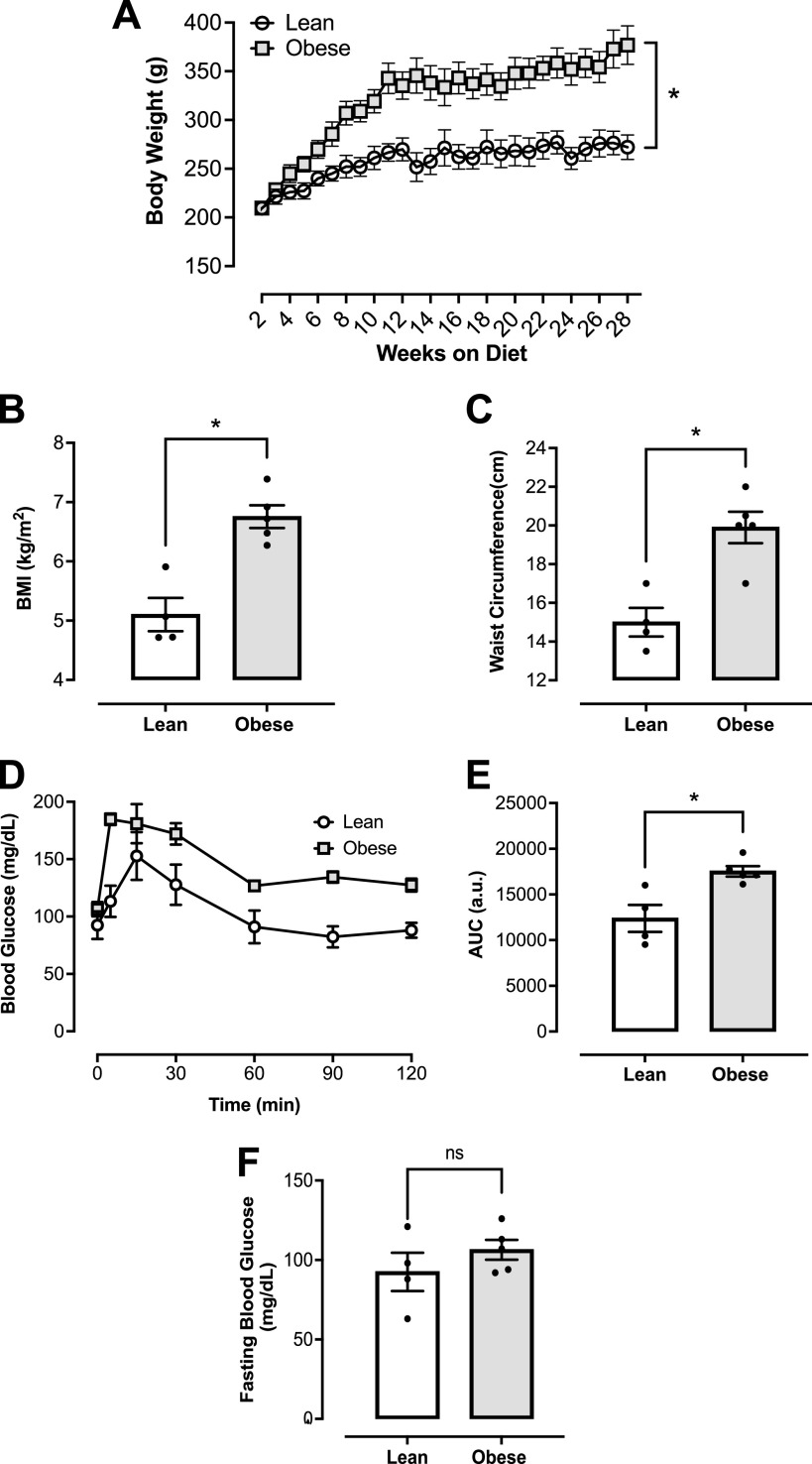

Characterization of WD-Induced Obesity in Female Rats

To characterize obesity in female rats fed a WD, body weight was measured over 28 wk on the diet, and BMI was calculated at the completion of the dietary protocol. Obesity was confirmed by an elevated body weight (Fig. 1A) and BMI (Fig. 1B) in the obese group after 28 wk on the WD. In addition, the obese group demonstrated increased waist circumference as compared with the age-matched lean group (Fig. 1C). Obese female rats were also found to have impaired glucose tolerance as demonstrated by the IPGTT (Fig. 1D). Total blood glucose accumulation in the obese group was higher over the 120-min period compared with the lean group (Fig. 1E). No differences in fasting glucose levels among the experimental groups (Fig. 1F).

Figure 1.

Western diet (WD) induces obesity and an altered metabolic profile in female rats. A: body weight over 28 wk on diet. B: BMI (kg/m2). C: waist circumference (centimeter). D: intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) performed over 120 min after administration of glucose (2 g/kg of body weight). E: total blood glucose accumulation reported as area under the curve (AUC) in arbitrary units (au). F: fasting blood glucose levels (mg/dL). *P < 0.05 vs. lean; n = 4 or 5 rats/group. Values are means ± SE. BMI, body mass index. Differences between groups were assessed with the use of two-tailed Students’s t test.

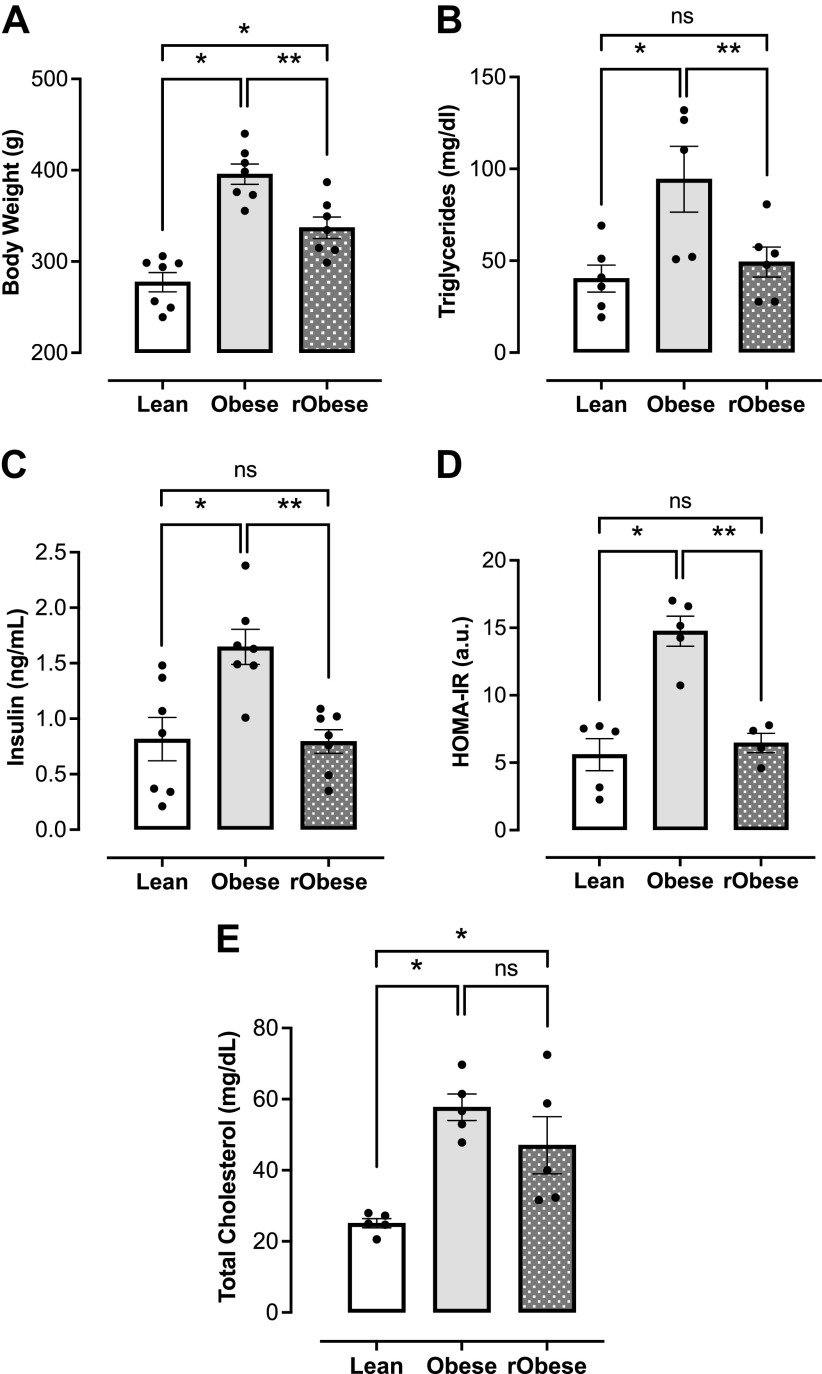

Obese Female Rats Returned to a SD Exhibit Weight Loss and Normalized Metabolic Parameters

The rObese group was placed on the WD for 18 wk and then returned to a SD for 12 wk before terminal experiments. As expected, the rObese group lost weight after returning to the SD (Fig. 2A). In human studies, patients with obesity who lost weight and patients with metabolic syndrome who lost weight exhibited decreased triglyceride levels as compared with baseline levels before weight loss (15, 54). Similarly, the rObese female rats also had decreased triglyceride levels as compared with the obese group (Fig. 2B). In addition, insulin levels and HOMA-IR were calculated to assess for insulin resistance. Although the obese group demonstrated increased insulin levels and insulin resistance as noted by their elevated HOMA-IR (Fig. 2, C and D), rats with short-term weight loss had insulin levels that returned to baseline and were not insulin resistant (Fig. 2, C and D). High levels of cholesterol detected in the obese group did not drop with short-term weight loss (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Obese female rats submitted to short-term weight loss display improvement of metabolic parameters. A: terminal body weight (g), n = 7 rats/group. B: fasting triglyceride levels (mg/dL), n = 5 or 6 rats/group. C: fasting insulin levels (ng/mL), n = 7 rats/group. D: homeostatic model of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), n = 4 or 5 rats/group. E: total cholesterol levels (mg/dL), n = 5 rats/group. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. lean, **P < 0.05 vs. obese. Differences between groups were assessed with the use of one-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons analysis.

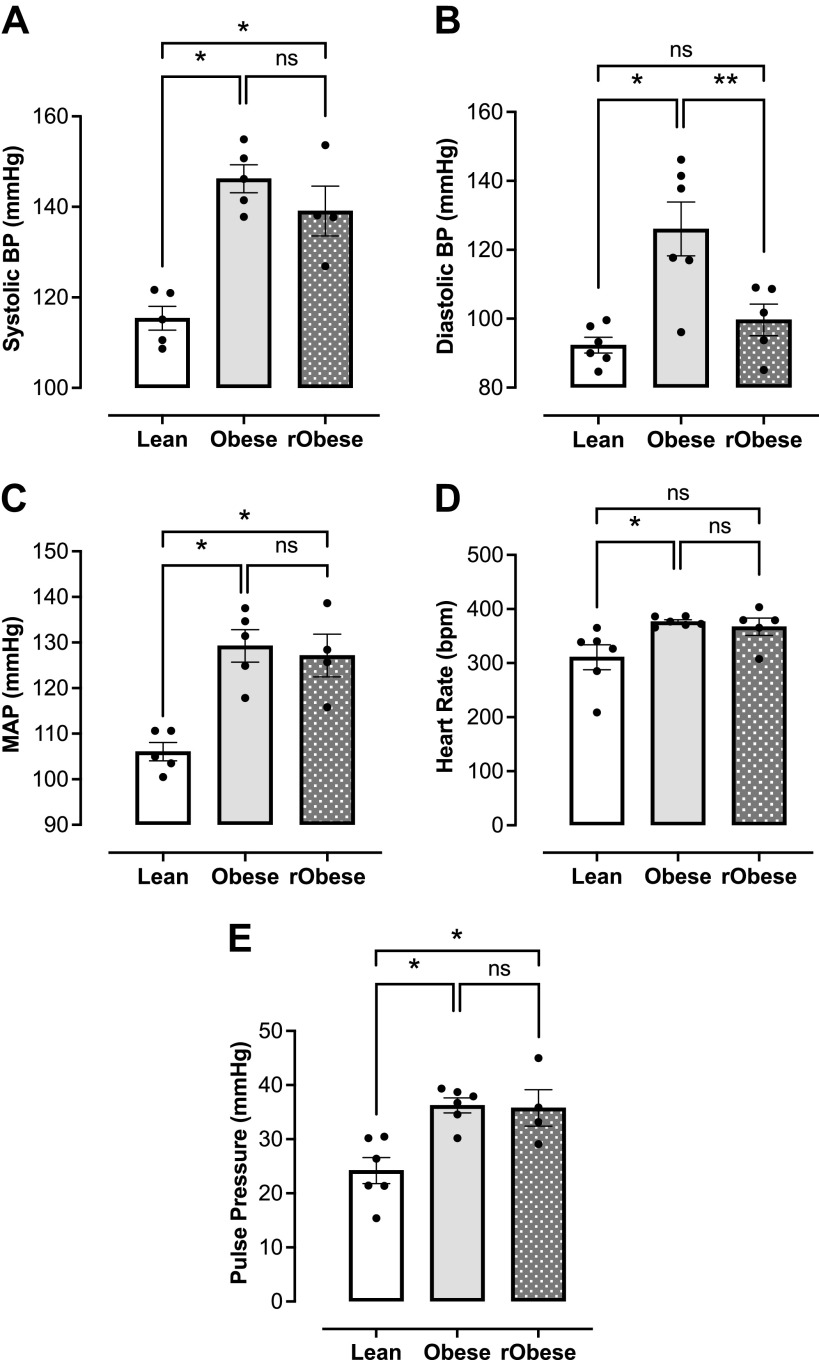

Short-Term Weight Loss Does Not Resolve Elevated Arterial Blood Pressure Found in Obese Female Rats

Our group has previously shown that WD-induced obesity is associated with elevated arterial blood pressure and heart rate in female Wistar rats (10). As expected, the obese group developed elevated systolic (Fig. 3A), diastolic (Fig. 3B), and mean arterial blood pressure (Fig. 3C) as compared with the lean group. Despite the weight loss, the rObese group sustained an elevated systolic (Fig. 3A) and mean arterial pressure (Fig. 3C). Heart rate was significantly elevated in the obese group. No changes in heart rate were found between obese and rObese groups nor between lean and rObese groups (Fig. 3D). Increased arterial stiffness frequently leads to increased pulse pressure, and thus pulse pressure is a surrogate marker of vascular stiffness (55, 56). The obese group exhibited increased pulse pressure, which was not resolved with weight loss (rObese group; Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Elevated arterial blood pressure in obese female rats does not decrease with short-term weight loss. A: systolic blood pressure (mmHg), n = 4 or 5 rats/group. B: diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), n = 5 or 6 rats/group. C: mean arterial pressure (MAP; mmHg), n = 4 or 5 rats/group. D: heart rate [beats/min (bpm)], n = 5 or 6 rats/group. E: pulse pressure (mmHg), n = 4 or 5 rats/group. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. lean, **P < 0.05 vs. obese.

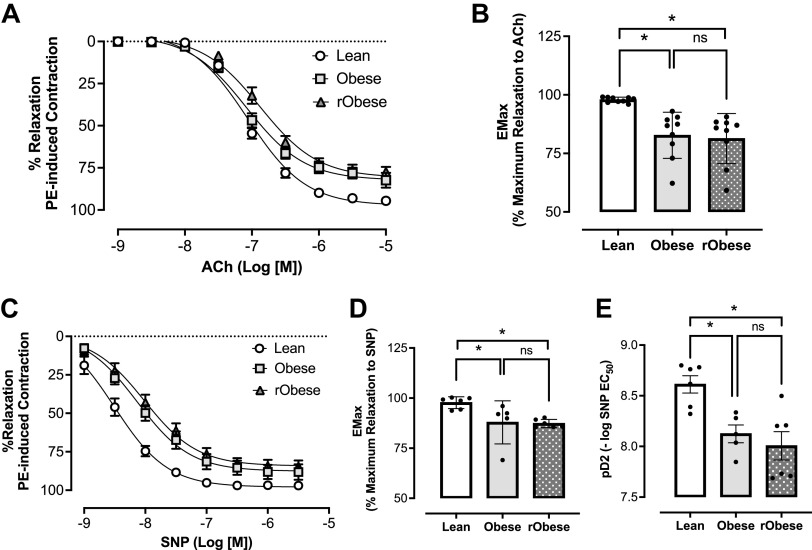

Impaired Vasodilation in Obesity Persists after Short-Term Weight Loss

Concentration-response curves to ACh and SNP were conducted in thoracic aortic rings to examine endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent relaxation, respectively. The obese group showed impaired response to ACh (Fig. 4A) with a significant reduction in maximal relaxation response (Fig. 4B). Likewise, the obese group showed decreased relaxation to SNP (Fig. 4C) with a significant reduction in maximal relaxation response (Fig. 4D) and sensitivity to SNP (Fig. 4E). This impaired vasodilation response to ACh and SNP was also observed in the rObese group (Fig. 4, A–E).

Figure 4.

Western diet (WD) induced vascular dysfunction in obesity persists after short-term weight loss. A: cumulative concentration-response curves to acetylcholine (ACh). Each point represents the maximal response to each concentration of ACh, n = 9 rats/group. B: maximal relaxation response at the maximal effect generated by ACh (Emax), n = 9 rats/group. C: cumulative concentration-response curves to sodium nitroprusside (SNP), n = 5 or 6 rats/group. D: maximal relaxation response at the maximal effect generated by SNP (Emax), n = 5 or 6 rats/group.E: sensitivity (pD2) to SNP, n = 5 or 6 rats/group. One-way ANOVA with repeated-measurements were used for statistical analysis. *P < 0.05 vs. lean, Sidak’s multiple comparison tests. Values are means ± SE.

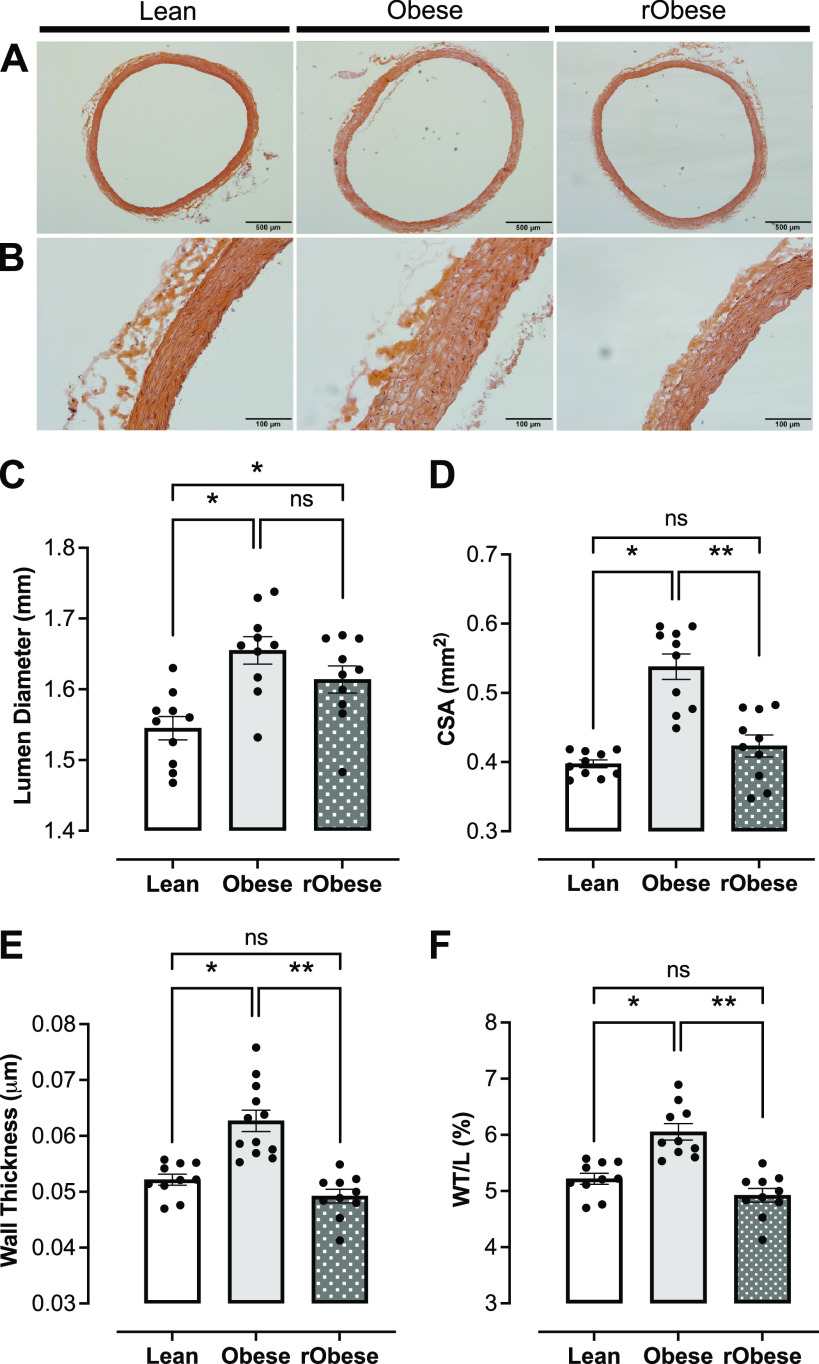

Arterial Remodeling in Obesity Resolves with Short-Term Weight Loss

Obesity has been linked to vascular remodeling in humans and animals, increasing the risk for cardiovascular events (57–59). Representative cross-sectional images of thoracic aortas from the lean, obese, and rObese groups are shown in Fig. 5, A (×4) and B (×20). Histomorphometric analysis of these aortas revealed increased CSA (Fig. 5D), wall thickness (Fig. 5E), lumen diameter (Fig. 5C), and WT/L (Fig. 5F) in obese female rats. In contrast, rats with short-term weight loss (rObese) demonstrated resolution of all vascular remodeling parameters except lumen diameter which remained increased (Fig. 5, C–F).

Figure 5.

Short-term weight loss resolves arterial remodeling in WD-induced obesity. A and B: representative photomicrographs of thoracic aortic cross sections from lean, obese, and reverse obese groups stained with hematoxylin and eosin: magnification of × 4 (A) and magnification of ×20 (B). C: lumen diameter (mm) of thoracic aortas. D: cross-sectional area (CSA; mm2) of thoracic aortas. E: wall thickness (µm) of thoracic aortas. F: wall-to-lumen ratio (W/L; %) of thoracic aortas. C–F were obtained using ImageJ software. *P < 0.05 vs. lean, **P < 0.05 vs. obese; n = 10 rats/group. Differences were assessed with the use of one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test. Values are means ± SE. WD, Western diet.

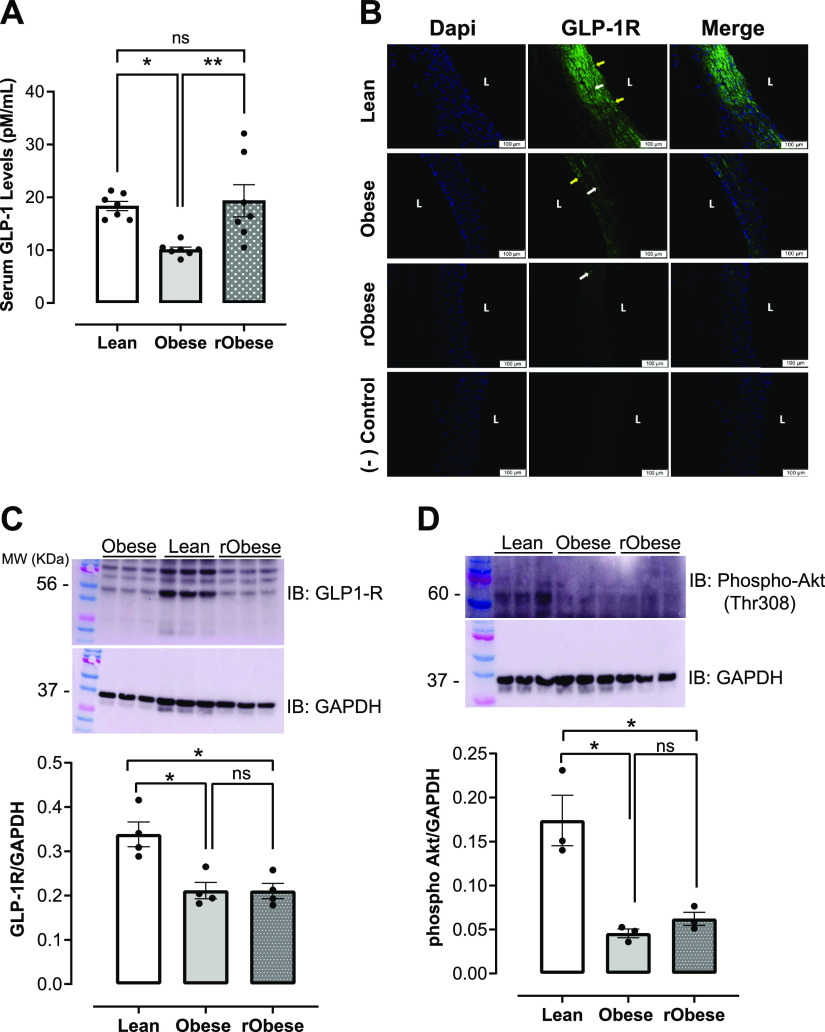

Decreased GLP-1 Signaling in Obesity Continues after Short-Term Weight Loss

To address whether GLP-1 signaling plays a role in persistent elevation of arterial blood pressure (BP) and impaired vasodilation after weight loss, GLP-1 serum levels were first measured. The obese group demonstrated decreased serum GLP-1 levels as compared with the lean group (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, GLP-1 serum levels were restored in the rObese group (Fig. 6A). GLP-1R expression detected by immunofluorescence in aortic rings demonstrated decreased GLP-1R expression in the obese animals and this decreased expression persisted with short-term weight loss in the rObese group (Fig. 6B). Quantification of aortic GLP-1R expression by Western blot demonstrated a significant decrease in GLP-1R in aortas from obese and rObese groups (Fig. 6C). To assess if downstream vascular GLP-1R signaling was impaired, phosphorylation of Akt at the threonine 308 residue was measured in aortas. Reduced levels of phosphorylated Akt were found in the aortas from obese and rObese groups compared with those in the lean group (Fig. 6D). GLP-1R expression was also measured in the mesenteric arteries of all three experimental groups (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Figure 6.

Downregulated GLP-1 signaling in obesity remains unchanged after short-term weight loss. A: serum GLP-1 levels (pM/mL), n = 7 rats/group. B: representative images of aortic cross sections with immunofluorescence staining for GLP-1R in lean, obese, and rObese groups, n = 5 rats/group. L: lumen; endothelial cells (yellow arrows); vascular smooth muscle cells (white arrows). Scale bar: 100 µm. C: protein expression of GLP-1R in aortas from lean, obese, and rObese groups. Top: representative immunoblot of GLP-1R. Bottom: bar graphs are means ± SE of 4 independent experiments as determined from densitometry relative to GAPDH, n = 4 rats/group. D: levels of phosphorylated Akt (Thr308) in aortas from lean, obese, and rObese groups. Top: representative immunoblot of phospho-Akt (Thr308). Bottom: bar graph of means ± SE of 3 independent experiments as determined from densitometry relative to GAPDH, n = 3 rats/group. *P < 0.05 vs. lean. **P< 0.05 vs. obese. GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; GLP-1R, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor.

DISCUSSION

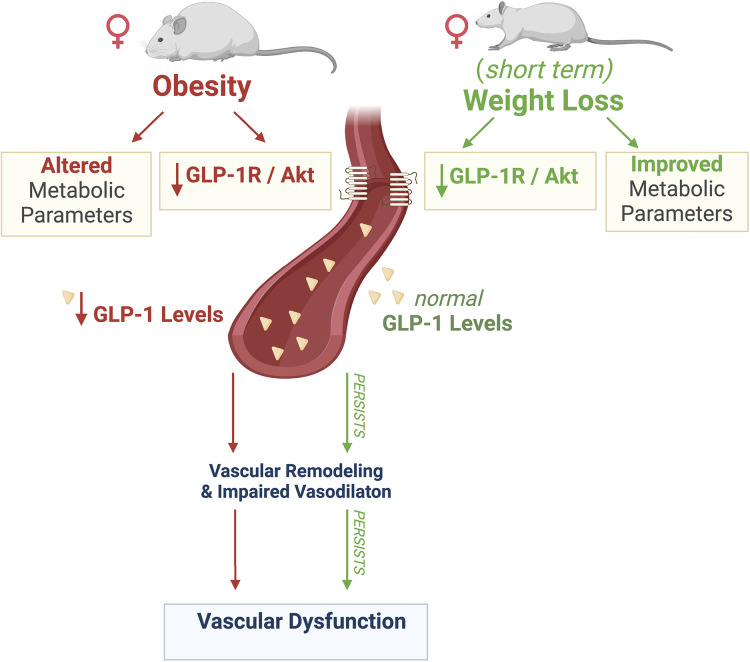

This study provides evidence that vascular complications caused by obesity are associated with downregulation of vascular GLP-1R. Although short-term weight loss ameliorated metabolic parameters, it was unable to resolve vascular complications nor restore vascular GLP-1 signaling. The main findings of this study are 1) obesity-induced impaired vasodilation and elevated systolic blood pressure are accompanied by downregulation of GLP-1/Akt signaling in aortas and 2) short-term weight loss failed to resolve vascular complications and rescue vascular GLP-1 signaling (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic summary of the present study. Obesity leads to altered metabolic parameters, decreased serum GLP-1 levels and vascular GLP-1 receptor expression, which may contribute to impaired vasodilation and vascular remodeling. Despite short-term weight loss improving metabolic parameters and restoring normal serum levels of GLP-1, it was unable to rescue GLP-1 receptor expression and GLP-1/Akt signaling and failed to reverse impaired vasodilation and vascular remodeling, resulting in persistent vascular dysfunction. Created with BioRender.com, and used with permission. GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; GLP-1R, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor.

As we previously demonstrated, female Wistar rats exposed to a Western diet develop obesity, impaired vasodilation, and high blood pressure (10). Our present results show that female rats gain significant body weight as early as 8 wk on the Western diet, along with an increased BMI and waist circumference. Together, these results characterize obesity in our model, which is in accordance with previous reports (60, 61). Currently, there is a lack of standardization when defining obesity in rodents. Our data suggest that noninvasive measurements, such as BMI and waist circumference, are useful tools to characterize central obesity.

In conjunction with developing obesity, female rats fed a Western diet developed glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. Despite this, the obese rats had normal fasting glucose levels, confirming that our model of Western diet-induced obesity does not develop type 2 diabetes. Our data revealing disruption of glucose and insulin homeostasis with fasting normoglycemia in obese female rats suggest a prediabetic state with an increased risk of eventually developing type 2 diabetes (62).

It has been well documented that obesity leads to vascular dysfunction in humans and experimental rodent models (63–66). Our model of Western diet-induced obesity in female rats exhibited elevated blood pressure and impaired endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation, indicating that obesity negatively affects both endothelial and vascular smooth muscle layers. Studies have demonstrated that vasodilation is a parameter frequently impaired in animal models of obesity; however, the underlying mechanism is not fully understood (67, 68).

Weight loss has been an effective approach to resolving cardiovascular complications caused by obesity. Studies have demonstrated that long-term weight loss frequently improves arterial blood pressure; however, it is still unclear if short-term weight loss has the same positive impact in ameliorating vascular function (69). Our results show that short-term weight loss was effective in correcting all metabolic parameters studied, including hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance, except for high total cholesterol levels. In fact, weight loss can lead to a temporary increase in cholesterol levels because of the mobilization of cholesterol stores, especially when on a high-fat diet (70, 71). Nevertheless, short-term weight loss failed to improve vascular dysfunction as indicated by the persistence of elevated blood pressure, impaired endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation, and increased pulse pressure in the rObese group. This suggests that short-term weight loss is not sufficient to fully restore vascular function.

Elevated systolic and mean arterial pressure found in obese female rats were not reversed with short-term weight loss. Isolated systolic hypertension has been linked to both endothelial dysfunction and increased arterial stiffness (72). In line with these findings, our data show persistent impairment of endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation and elevated pulse pressure in the rObese group. Moreover, a persistent increase in pulse pressure suggests a potential increase in arterial stiffness, which frequently leads to elevated systolic blood pressure. Elevated heart rate has been reported in high-fat diet-fed male rats (73, 74), which is mostly due to autonomic dysregulation, such as increased sympathetic activity (75, 76). Interestingly, animal studies have demonstrated that the activation of GLP-1R can cause an increase in heart rate via multiple mechanisms, including decreased parasympathetic modulation of the heart (77–79). Our data show that obese female rats exhibited elevated heart rate in the context of decreased vascular GLP-1 expression. Despite decreased vascular GLP-1R expression, the rObese group showed no changes in heart rate compared with obese group. Further studies are needed to fully address the involvement of autonomic dysregulation in the context of short-term weight loss and vascular GLP-1 expression.

GLP-1 has a protective effect within the vascular system (28, 80). Human studies have shown that circulating levels of GLP-1 are reduced in obesity (26, 81). This is in concordance with our results showing low serum levels of GLP-1 in obese female rats. The novelty of our findings is that together with reduced circulating GLP-1 levels, GLP-1 signaling is also decreased in aortas from obese female rats. Thus, decreased vascular GLP-1 signaling may be a potential mechanism involved in obesity-related vascular complications. GLP-1Rs are expressed in the vasculature, and more specifically endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells (21, 22). Although GLP-1R agonists were primarily developed to treat diabetes by stimulating insulin release, recent studies have demonstrated that GLP-1R agonists also have a beneficial effect on the vascular system. For example, human studies have demonstrated that GLP-1R agonists reduce blood pressure and improve endothelial function in diabetes (82, 83). Experimental studies have provided evidence that GLP-1R agonists reduces vascular inflammation and oxidative stress (28, 84). Vascular GLP-1 signaling is implicated in hypertensive vascular complications (28). In the obesity context, human studies have revealed that vascular GLP-1R is downregulated in human subjects with obesity (85). Accordingly, our results show that GLP-1R expression is decreased in aortas from obese female rats. More intriguingly, weight loss did not restore GLP-1R expression back to baseline levels, suggesting that obesity causes a persistent downregulation of vascular GLP-1R.

Obesity-induced downregulation of aortic GLP-1 signaling was also associated with aortic remodeling as detected by increased CSA, wall thickness, lumen diameter, and WT/L, consistent with outward hypertrophic remodeling (86). This is in accordance with previous studies showing that increased aortic diameter is a frequent finding in the classic hypertensive aortic phenotype (87). Interestingly, increased aortic diameter was also observed in the rObese group, indicating that short-term weight loss did not reverse this structural change. Outward hypertrophic vascular remodeling and vascular stiffness have also been shown to lead to increased pulse pressure (86). Therefore, we used pulse pressure measurements as a surrogate marker of arterial stiffness. Obese female rats exhibited an increased pulse pressure indicating arterial stiffness, which often precedes the development of hypertension and is an indirect biomarker in the detection of CVD (56, 87). It has been well documented that GLP-1R agonists reduce oxidative stress and inflammation in vascular endothelial cells along with reducing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through the ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt pathways (24, 28, 88). Thus, we hypothesize that downregulated vascular GLP-1 signaling in the obese animals contributes to a decrease in the anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1 signaling and a subsequent increase in vascular remodeling. Together, these findings strongly suggest that GLP-1 signaling might play a role in maintaining vascular homeostasis, and studying vascular GLP-1 signaling in the context of obesity is crucial.

In summary, results from this study revealed for the first time that persistent vascular dysfunction after short-term weight loss is paired with continued downregulation of vascular GLP-1R.

Study Limitations

A limitation of this study is that we have not inhibited GLP-1R specifically in the vasculature. Thus, future studies are required to target GLP-1R in the vascular system.

Future studies are needed to evaluate vascular dysfunction in resistance vessels (mesenteric arteries), which are more suitable for evaluating blood pressure regulation mechanisms.

Conclusions

The results of this study revealed that short-term weight loss does not guarantee recovery of vascular function and that vascular GLP-1 signaling may be implicated in obesity-related development of impaired vasodilation, increased systolic blood pressure, and increased pulse pressure that persists after weight loss. Thus, vascular GLP-1 signaling may be a potential candidate for mediating obesity-induced vascular dysfunction.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20231673.v1.

GRANTS

This study was supported by a Faculty Development grant from NYITCOM (to M.A.C.-S.) and 2021 Scholarship in Cardiovascular Disease from the American Heart Association (to R.K.). W.C. is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 MH125903 and K01 DK120740.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.K., D.P., N.M., and M.A.C.-S. conceived and designed research; R.K., D.P., N.M., and M.A.C.-S. performed experiments; R.K., D.P., N.M., W.C., and M.A.C.-S. analyzed data; R.K., D.P., N.M., W.C., and M.A.C.-S. interpreted results of experiments; R.K., D.P., and M.A.C.-S. prepared figures; R.K., D.P., N.M., and M.A.C.-S. drafted manuscript; R.K., D.P., N.M., W.C., and M.A.C.-S. edited and revised manuscript; R.K., D.P., N.M., W.C., and M.A.C.-S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedrich MJ. Global obesity epidemic worsening. JAMA 318: 603, 2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James WP. WHO recognition of the global obesity epidemic. Int J Obes (Lond) 32, Suppl 7: S120–S126, 2008. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Adult Obesity Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html[2021 Jan 19].

- 4.Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, Barrett JL, Giles CM, Flax C, Long MW, Gortmaker SL. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med 381: 2440–2450, 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1909301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, Mann N, Lindeberg S, Watkins BA, O'Keefe JH, Brand-Miller J. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr 81: 341–354, 2005. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murtaugh MA, Herrick JS, Sweeney C, Baumgartner KB, Guiliano AR, Byers T, Slattery ML. Diet composition and risk of overweight and obesity in women living in the southwestern United States. J Am Diet Assoc 107: 1311–1321, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopp W. How Western diet and lifestyle drive the pandemic of obesity and civilization diseases. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 12: 2221–2236, 2019. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S216791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egan BM, Li J, Hutchison FN, Ferdinand KC. Hypertension in the United States, 1999 to 2012: progress toward Healthy People 2020 goals. Circulation 130: 1692–1699, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen JB. Hypertension in obesity and the impact of weight loss. Curr Cardiol Rep 19: 98, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11886-017-0912-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer B, França LM, Zhang Y, Paes AMDA, Gerdes AM, Carrillo-Sepulveda MA. Western diet triggers toll-like receptor 4 signaling-induced endothelial dysfunction in female Wistar rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H1735–H1747, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00218.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shihab HM, Meoni LA, Chu AY, Wang N-Y, Ford DE, Liang K-Y, Gallo JJ, Klag MJ. Body mass index and risk of incident hypertension over the life course: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Circulation 126: 2983–2989, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.117333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vileigas DF, de Souza SLB, Corrêa CR, Silva CCVDA, de Campos DHS, Padovani CR, Cicogna AC. The effects of two types of Western diet on the induction of metabolic syndrome and cardiac remodeling in obese rats. J Nutr Biochem 92: 108625, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2021.108625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens J, Erber E, Truesdale KP, Wang C-H, Cai J. Long- and short-term weight change and incident coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol 178: 239–248, 2013. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clamp LD, Hume DJ, Lambert EV, Kroff J. Enhanced insulin sensitivity in successful, long-term weight loss maintainers compared with matched controls with no weight loss history. Nutr Diabetes 7: e282–e282, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2017.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harder H, Dinesen B, Astrup A. The effect of a rapid weight loss on lipid profile and glycemic control in obese type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28: 180–182, 2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grill HJ. A role for GLP-1 in treating hyperphagia and obesity. Endocrinology 161: bqaa093, 2020. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanoski SE, Hayes MR, Skibicka KP. GLP-1 and weight loss: unraveling the diverse neural circuitry. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R885–R895, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00520.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab 27: 740–756, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, Greenway F, Halpern A, Krempf M, Lau DCW, Le Roux CW, Violante Ortiz R, Jensen CB, Wilding JPH. A Randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of Liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med 373: 11–22, 2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holst JJ. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol Rev 87: 1409–1439, 2007. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pyke C, Heller RS, Kirk RK, Ørskov C, Reedtz-Runge S, Kaastrup P, Hvelplund A, Bardram L, Calatayud D, Knudsen LB. GLP-1 receptor localization in monkey and human tissue: novel distribution revealed with extensively validated monoclonal antibody. Endocrinology 155: 1280–1290, 2014. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen EP, Poulsen SS, Kissow H, Holstein-Rathlou N-H, Deacon CF, Jensen BL, Holst JJ, Sorensen CM. Activation of GLP-1 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells reduces the autoregulatory response in afferent arterioles and increases renal blood flow. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F867–F877, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00527.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh YS, Jun HS. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on oxidative stress and Nrf2 signaling. Int J Mol Sci 19: 26, 2017. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi L, Ji Y, Jiang X, Zhou L, Xu Y, Li Y, Jiang W, Meng P, Liu X. Liraglutide attenuates high glucose-induced abnormal cell migration, proliferation, and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells by activating the GLP-1 receptor, and inhibiting ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Cardiovasc Diabetol 14: 18, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12933-015-0177-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muscelli E, Mari A, Casolaro A, Camastra S, Seghieri G, Gastaldelli A, Holst JJ, Ferrannini E. Separate impact of obesity and glucose tolerance on the incretin effect in normal subjects and type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 57: 1340–1348, 2008. doi: 10.2337/db07-1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranganath LR, Beety JM, Morgan LM, Wright JW, Howland R, Marks V. Attenuated GLP-1 secretion in obesity: cause or consequence? Gut 38: 916–919, 1996. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.6.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B, Zhong J, Lin H, Zhao Z, Yan Z, He H, Ni Y, Liu D, Zhu Z. Blood pressure-lowering effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists exenatide and liraglutide: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab 15: 737–749, 2013. doi: 10.1111/dom.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helmstädter J, Frenis K, Filippou K, Grill A, Dib M, Kalinovic S, Pawelke F, Kus K, Kröller-Schön S, Oelze M, Chlopicki S, Schuppan D, Wenzel P, Ruf W, Drucker DJ, Münzel T, Daiber A, Steven S. Endothelial GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) receptor mediates cardiovascular protection by liraglutide in mice with experimental arterial hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 40: 145–158, 2020. doi: 10.1161/atv.0000615456.97862.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katout M, Zhu H, Rutsky J, Shah P, Brook RD, Zhong J, Rajagopalan S. Effect of GLP-1 mimetics on blood pressure and relationship to weight loss and glycemia lowering: results of a systematic meta-analysis and meta-regression. Am J Hypertens 27: 130–139, 2014. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpt196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji H, Niiranen TJ, Rader F, Henglin M, Kim A, Ebinger JE, Claggett B, Merz CNB, Cheng S. Sex differences in blood pressure associations with cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 143: 761–763, 2021. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.049360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manrique-Acevedo C, Chinnakotla B, Padilla J, Martinez-Lemus LA, Gozal D. Obesity and cardiovascular disease in women. Int J Obes (Lond) 44: 1210–1226, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-0548-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Templeton A. Obesity and women's health. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 6: 175–176, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Overweight & Obesity Statistics. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/overweight-obesity[2021 Sep 8].

- 34.National Research Council (U.S.). Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th ed.). Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html[2021 Sep 8].

- 36.Vazquez G, Duval S, Jacobs DR Jr, Silventoinen K. Comparison of body mass index, waist circumference, and waist/hip ratio in predicting incident diabetes: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Rev 29: 115–128, 2007. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44583/?sequence=1[2021 Sep 8].

- 38.Ahmad N, Adam SI, Nawi AM, Hassan MR, Ghazi HF. Abdominal obesity indicators: waist circumference or waist-to-hip ratio in Malaysian adults population. Int J Prev Med 7: 82, 2016. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.183654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antunes LC, Elkfury JL, Jornada MN, Foletto KC, Bertoluci MC. Validation of HOMA-IR in a model of insulin-resistance induced by a high-fat diet in Wistar rats. Arch Endocrinol Metab 60: 138–142, 2016. doi: 10.1590/2359-3997000000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lozano I, Van der Werf R, Bietiger W, Seyfritz E, Peronet C, Pinget M, Jeandidier N, Maillard E, Marchioni E, Sigrist S, Dal S. High-fructose and high-fat diet-induced disorders in rats: impact on diabetes risk, hepatic and vascular complications. Nutr Metab (Lond) 13: 15, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s12986-016-0074-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bender SB, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Garro M, Reyes-Aldasoro CC, Sowers JR, DeMarco VG, Martinez-Lemus LA. Regional variation in arterial stiffening and dysfunction in Western diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H574–H582, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00155.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hink J, Thom SR, Simonsen U, Rubin I, Jansen E. Vascular reactivity and endothelial NOS activity in rat thoracic aorta during and after hyperbaric oxygen exposure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1988–H1998, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00145.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agbor LN, Nair AR, Wu J, Lu K-T, Davis DR, Keen HL, Quelle FW, McCormick JA, Singer JD, Sigmund CD. Conditional deletion of smooth muscle Cullin-3 causes severe progressive hypertension. JCI Insight 5: e129793, 2019. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.129793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Q, Zhuo K, Cai R, Su X, Zhang L, Liu Y, Zhu L, Ren F, Zhou M-S. Activation of yes-associated protein/PDZ-binding motif pathway contributes to endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation in angiotensinII hypertension. Front Physiol 12: 732084, 2021. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.732084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Syed AA, Shafiq M, Reza MI, Bharati P, Husain A, Singh P, Hanif K, Gayen JR. Ethanolic extract of Cissus quadrangularis improves vasoreactivity by modulation of eNOS expression and oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Hypertens 44: 63–71, 2021. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2021.1991942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maia AR, Batista TM, Victorio JA, Clerici SP, Delbin MA, Carneiro EM, Davel AP. Taurine supplementation reduces blood pressure and prevents endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in post-weaning protein-restricted rats. PLoS One 9: e105851, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carrillo-Sepulveda MA, Spitler K, Pandey D, Berkowitz DE, Matsumoto T. Inhibition of TLR4 attenuates vascular dysfunction and oxidative stress in diabetic rats. J Mol Med (Berl) 93: 1341–1354, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00109-015-1318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katsurada K, Nandi SS, Sharma NM, Zheng H, Liu X, Patel KP. Does glucagon-like peptide-1 induce diuresis and natriuresis by modulating afferent renal nerve activity? Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 317: F1010–F1021, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00028.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu X, Patel KP, Zheng H. Role of renal sympathetic nerves in GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) receptor agonist exendin-4-mediated diuresis and natriuresis in diet-induced obese rats. J Am Heart Assoc 10: e022542, 2021. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie Z, Enkhjargal B, Nathanael M, Wu L, Zhu Q, Zhang T, Tang J, Zhang JH. Exendin-4 preserves blood-brain barrier integrity via glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor/activated protein kinase-dependent nuclear factor-kappa B/matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibition after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rat. Front Mol Neurosci 14: 750726, 2021. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.750726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taguchi K, Bessho N, Kaneko N, Okudaira K, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi T. Glucagon-like peptide-1 increased the vascular relaxation response via AMPK/Akt signaling in diabetic mice aortas. Eur J Pharmacol 865: 172776, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang JL, Chen WY, Chen SD. The emerging role of GLP-1 receptors in DNA repair: implications in neurological disorders. Int J Mol Sci 18: 1861, 2017. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rozentsvit A, Vinokur K, Samuel S, Li Y, Gerdes AM, Carrillo-Sepulveda MA. Ellagic acid reduces high glucose-induced vascular oxidative stress through ERK1/2/NOX4 signaling pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem 44: 1174–1187, 2017. doi: 10.1159/000485448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan DC, Watts GF, Ng TWK, Yamashita S, Barrett PHR. Effect of weight loss on markers of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism in the metabolic syndrome. Eur J Clin Invest 38: 743–751, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mackenzie IS, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR. Assessment of arterial stiffness in clinical practice. QJM 95: 67–74, 2002. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Said MA, Eppinga RN, Lipsic E, Verweij N, van der Harst P. Relationship of arterial stiffness index and pulse pressure with cardiovascular disease and mortality. J Am Heart Assoc 7: e007621, 2018. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu S, Touyz RM. Reactive oxygen species and vascular remodelling in hypertension: still alive. Can J Cardiol 22: 947–951, 2006. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(06)70314-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carmo LS, Burdmann EA, Fessel MR, Almeida YE, Pescatore LA, Farias-Silva E, Gamarra LF, Lopes GH, Aloia TPA, Liberman M. Expansive vascular remodeling and increased vascular calcification response to cholecalciferol in a murine model of obesity and insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 39: 200–211, 2019. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aroor AR, Jia G, Sowers JR. Cellular mechanisms underlying obesity-induced arterial stiffness. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 314: R387–R398, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00235.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Novelli ELB, Diniz YS, Galhardi CM, Ebaid GMX, Rodrigues HG, Mani F, Fernandes AAH, Cicogna AC, Novelli Filho JLVB. Anthropometrical parameters and markers of obesity in rats. Lab Anim 41: 111–119, 2007. doi: 10.1258/002367707779399518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Engelbregt MJ, van Weissenbruch MM, Popp-Snijders C, Lips P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Body mass index, body composition, and leptin at onset of puberty in male and female rats after intrauterine growth retardation and after early postnatal food restriction. Pediatr Res 50: 474–478, 2001. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burgeiro A, Cerqueira MG, Varela-Rodríguez B, Nunes S, Neto P, Pereira F, Reis F, Carvalho E. Glucose and lipid dysmetabolism in a rat model of prediabetes induced by a high-sucrose diet. Nutrients 9: 638, 2017. doi: 10.3390/nu9060638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elmarakby AA, Imig JD. Obesity is the major contributor to vascular dysfunction and inflammation in high-fat diet hypertensive rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 118: 291–301, 2010. doi: 10.1042/CS20090395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roberts CK, Barnard RJ, Sindhu RK, Jurczak M, Ehdaie A, Vaziri ND. A high-fat, refined-carbohydrate diet induces endothelial dysfunction and oxidant/antioxidant imbalance and depresses NOS protein expression. J Appl Physiol (1985) 98: 203–210, 2005. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00463.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Virdis A, Colucci R, Bernardini N, Blandizzi C, Taddei S, Masi S. Microvascular endothelial dysfunction in human obesity: role of TNF-α. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 104: 341–348, 2019. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang L, Wheatley CM, Richards SM, Barrett EJ, Clark MG, Rattigan S. TNF-alpha acutely inhibits vascular effects of physiological but not high insulin or contraction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Physiol 285: E654–E660, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00119.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiang L, Dearman J, Abram SR, Carter C, Hester RL. Insulin resistance and impaired functional vasodilation in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1658–H1666, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01206.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sweazea KL, Lekic M, Walker BR. Comparison of mechanisms involved in impaired vascular reactivity between high sucrose and high fat diets in rats. Nutr Metab (Lond) 7: 48, 2010. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stevens VJ, Obarzanek E, Cook NR, Lee IM, Appel LJ, Smith West D, Milas NC, Mattfeldt-Beman M, Belden L, Bragg C, Millstone M, Raczynski J, Brewer A, Singh B, Cohen J; Trials for the Hypertension Prevention Research Group. Long-term weight loss and changes in blood pressure: results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Ann Intern Med 134: 1–11, 2001. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hernandez TL, Sutherland JP, Wolfe P, Allian-Sauer M, Capell WH, Talley ND, Wyatt HR, Foster GD, Hill JO, Eckel RH. Lack of suppression of circulating free fatty acids and hypercholesterolemia during weight loss on a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet. Am J Clin Nutr 91: 578–585, 2010. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Phinney SD, Tang AB, Waggoner CR, Tezanos-Pinto RG, Davis PA. The transient hypercholesterolemia of major weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr 53: 1404–1410, 1991. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.6.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wallace SML, Yasmin, McEniery CM, Mäki-Petäjä KM, Booth AD, Cockcroft JR, Wilkinson IB. Isolated systolic hypertension is characterized by increased aortic stiffness and endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension 50: 228–233, 2007. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Speretta GF, Lemes EV, Vendramini RC, Menani JV, Zoccal DB, Colombari E, Colombari DSA, Bassi M. High-fat diet increases respiratory frequency and abdominal expiratory motor activity during hypercapnia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 258: 32–39, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Durak A, Olgar Y, Tuncay E, Karaomerlioglu I, Kayki Mutlu G, Arioglu Inan E, Altan VM, Turan B. Onset of decreased heart work is correlated with increased heart rate and shortened QT interval in high-carbohydrate fed overweight rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 95: 1335–1342, 2017. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2017-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rossi RC, Vanderlei LCM, Gonçalves ACCR, Vanderlei FM, Bernardo AFB, Yamada KMH, da Silva NT, de Abreu LC. Impact of obesity on autonomic modulation, heart rate and blood pressure in obese young people. Auton Neurosci 193: 138–141, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.07.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bruder-Nascimento T, Ekeledo OJ, Anderson R, Le HB, Belin de Chantemèle EJ. Long term high fat diet treatment: an appropriate approach to study the sex-specificity of the autonomic and cardiovascular responses to obesity in mice. Front Physiol 8: 32, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Griffioen KJ, Wan R, Okun E, Wang X, Lovett-Barr MR, Li Y, Mughal MR, Mendelowitz D, Mattson MP. GLP-1 receptor stimulation depresses heart rate variability and inhibits neurotransmission to cardiac vagal neurons. Cardiovasc Res 89: 72–78, 2011.doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baggio LL, Ussher JR, McLean BA, Cao X, Kabir MG, Mulvihill EE, Mighiu AS, Zhang H, Ludwig A, Seeley RJ, Heximer SP, Drucker DJ. The autonomic nervous system and cardiac GLP-1 receptors control heart rate in mice. Mol Metab 6: 1339–1349, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nyström T, Gutniak MK, Zhang Q, Zhang F, Holst JJ, Ahrén B, Sjöholm A. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on endothelial function in type 2 diabetes patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Physiol 287: E1209–E1215, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00237.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Almutairi M, Al Batran R, Ussher JR. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor action in the vasculature. Peptides 111: 26–32, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Otten J, Ryberg M, Mellberg C, Andersson T, Chorell E, Lindahl B, Larsson C, Holst JJ, Olsson T. Postprandial levels of GLP-1, GIP and glucagon after 2 years of weight loss with a Paleolithic diet: a randomised controlled trial in healthy obese women. Eur J Endocrinol 180: 417–427, 2019. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sun F, Wu S, Guo S, Yu K, Yang Z, Li L, Zhang Y, Quan X, Ji L, Zhan S. Impact of GLP-1 receptor agonists on blood pressure, heart rate and hypertension among patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 110: 26–37, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Koska J, Schwartz EA, Mullin MP, Schwenke DC, Reaven PD. Improvement of postprandial endothelial function after a single dose of exenatide in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance and recent-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 33: 1028–1030, 2010. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Drucker DJ. The cardiovascular biology of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab 24: 15–30, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kimura T, Obata A, Shimoda M, Shimizu I, da Silva Xavier G, Okauchi S, Hirukawa H, Kohara K, Mune T, Moriuchi S, Hiraoka A, Tamura K, Chikazawa G, Ishida A, Yoshitaka H, Rutter GA, Kaku K, Kaneto H. Down-regulation of vascular GLP-1 receptor expression in human subjects with obesity. Sci Rep 8: 10644, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28849-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Edwards JM, Roy S, Tomcho JC, Schreckenberger ZJ, Chakraborty S, Bearss NR, Saha P, McCarthy CG, Vijay-Kumar M, Joe B, Wenceslau CF. Microbiota are critical for vascular physiology: germ-free status weakens contractility and induces sex-specific vascular remodeling in mice. Vascul Pharmacol 125–126: 106633, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2019.106633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schiffrin EL. Vascular remodeling in hypertension: mechanisms and treatment. Hypertension 59: 367–374, 2012. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.187021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eriksson L, Saxelin R, Röhl S, Roy J, Caidahl K, Nyström T, Hedin U, Razuvaev A. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation does not affect re-endothelialization but reduces intimal hyperplasia via direct effects on smooth muscle cells in a nondiabetic model of arterial injury. J Vasc Res 52: 41–52, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000381097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20231673.v1.