Abstract

Organisations spanning social services, public health and healthcare have increasingly experimented with collaboration as a tool for improving population health and reducing health disparities. While there has been progress, the results have fallen short of expectations. Reflecting on these shortcomings, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) recently proposed a new framework for cross‐sector alignment intended to move the field towards improved outcomes. A central idea in this framework is that collaboratives will be more effective and sustainable if they develop collaborative systems in four core areas: shared purpose, governance, finance and shared data. The goal of this paper is to provide a foundation for research on the four core areas of the cross‐sector alignment framework. Accordingly, this study is based on two guiding questions: (1) how are collaboratives currently implementing systems in the four core areas identified in the framework, and (2) what strategies does the literature offer for creating sustainable systems in these four areas? Given the emergent nature of research on health‐oriented cross‐sector collaboration and the broad research questions, we conducted a systematic scoping review including 179 relevant research papers and reports published internationally from the years 2010–2020. We identified the main contributions and coded each based on its relevance to the cross‐sector alignment framework. We found that most papers focused on programme evaluations rather than theory testing, and while many strategies were offered, they tended to reflect a focus on short‐term collaboration. The results also demonstrate that starting points and resource levels vary widely across individuals and organisations involved in collaborations. Accordingly, identifying and comparing distinct pathways by which different parties might pursue cross‐sector alignment is an imperative for future work. More broadly, the literature is ripe with observations that could be assessed systematically to produce a firm foundation for research and practice.

Keywords: aligning, collaboration, cross‐sector, population health, social determinants of health

What is known about this topic

Factors beyond health care, especially the social determinants of health, affect population health and health disparities.

Areas with denser cross‐sector networks tend to have better population health outcomes.

Efforts to collaborate across sectors have met with considerable challenges.

What this paper adds

Most studies we reviewed suggest that the four core components of the RWJF cross‐sector alignment framework are important for successful collaboration and health outcomes.

Optimal strategies for cross‐sector collaboration will vary depending on the resources and starting points of the individuals and organisations involved.

Many of the observations in the literature on health‐oriented cross‐sector collaboration strategies have yet to be systematically assessed.

What is known about this topic

Factors beyond health care, especially the social determinants of health, affect population health and health disparities.

Areas with denser cross‐sector networks tend to have better population health outcomes.

Efforts to collaborate across sectors have met with considerable challenges.

What this paper adds

Most studies we reviewed suggest that the four core components of the RWJF cross‐sector alignment framework are important for successful collaboration and health outcomes.

Optimal strategies for cross‐sector collaboration will vary depending on the resources and starting points of the individuals and organisations involved.

Many of the observations in the literature on health‐oriented cross‐sector collaboration strategies have yet to be systematically assessed.

1. INTRODUCTION

Health‐oriented cross‐sector collaboration has become an increasingly important area of research and practice across the globe. Many factors contributed to this movement, but perhaps foremost are increased recognition of the social determinants of health (SDoH) and the consequent increased attention to the role that factors outside clinical care play in shaping population health (Hood et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2003, 2008). The resulting concern for health determinants beyond clinical care has drawn attention to cross‐sector collaboration (Gottlieb et al., 2017). Yet, while collaboratives have achieved success (Mays et al., 2016), the outcomes have fallen short of expectations (Abraham et al., 2019; Gottlieb et al., 2019; Hall & Jacobson, 2018; Holt et al., 2017).

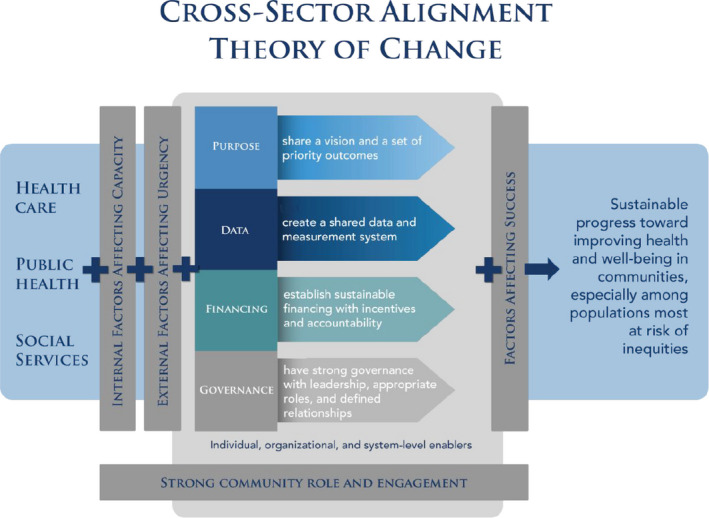

In response, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) recently consolidated learnings from its experiences with research and practice in cross‐sector collaboration over the past three decades. The result of this effort was the cross‐sector alignment theory of change (Figure 1; Landers, G., Minyard, K., Lanford, D., & Heishman, H., 2020). A theory of change for aligning health care, public health, and social services in a time of COVID‐19. American Journal of Public Health, 110(S2), S178–S180). The cross‐sector alignment theory of change is based on lessons learned from a large portfolio of projects that were motivated by a range of historical events including, among other things, organising around the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, the increasing recognition of the importance of SDoH and the rise to prominence of Accountable Communities of Health as a means of addressing rising healthcare costs. Key motivations for creating the cross‐sector alignment theory of change included consolidating learnings from earlier projects and spurring the development of theory that could inform practical decisions while being amenable to further development in the academic literature.

FIGURE 1.

The cross‐sector alignment theory of change. This image was reprinted with permission from Landers et al. (2020) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The principal idea to emerge from RWJF's review of investments in cross‐sector collaboration was that stubborn population health and health disparity challenges are better addressed when healthcare, public health and social service organisations move beyond small‐scale collaboration towards aligned and sustainable systems, particularly in four core areas: shared purpose, governance, finance and data and measurement. Accordingly, these four core areas are located at the centre of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change (Landers et al., 2020). We draw on the cross‐sector alignment theory of change to define aligning in this context as a specific condition in which organisations in the healthcare, public health and social service sectors are sharing systems in each of the four core areas. Aligning in this sense can be contrasted with general collaboration, which does not require a particular cooperative structure. The purpose of the present paper is to provide a foundation for systematic research on the cross‐sector alignment theory of change by assessing existing academic research on health‐oriented cross‐sector collaboration for key themes related to the four core areas of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change and for strategies that might help move research and practice from a focus on short‐term collaboration to a focus on sustainable alignment. The guiding questions for this study are: (1) how are collaboratives currently implementing systems in the four core areas identified in the cross‐sector alignment theory of change, and (2) what strategies does the literature offer for creating sustainable systems in these four areas?

2. METHODS

This literature review is a scoping review, meaning that it focuses on describing and analysing an emerging literature on a broad topic rather than summarising findings regarding a specific causal relationship or assessing the quality of a narrowly related set of articles, as in a Cochrane‐style systematic review (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). Accordingly, this study is not intended to compare the relative importance of different factors for cross‐sector collaboration. Rather, the goals of this scoping review are to summarise, organise and disseminate prior research findings; identify common themes; and identify research gaps and opportunities related to the cross‐sector alignment theory of change (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). As outlined below, documents for this review were collected using a three‐part approach: a systematic scan of academic search engines, a systematic scan of key journals and a purposive scan of material outside the peer‐reviewed literature including white papers and conference presentations.

2.1. Systematic scan of academic search engines

Academic Search Complete, PubMed and the Cochrane Library were each searched using a search term that reflects the objective of identifying studies addressing health‐oriented cross‐sector collaboration:

(multi‐sector OR multisector OR “multi sector” OR cross‐sector OR “cross sector” OR intersectoral OR inter‐sectoral OR multisite OR multi‐site)

AND (collab* OR partner* OR integrat* OR joint OR alliance OR allied OR coalition)

AND health

AND (((healthcare OR “health care”) AND (social OR communit*))

OR ((healthcare OR “health care”) AND “public health”)

OR ((social OR communit*) AND “public health”))

Articles were scanned by two researchers and included if they met the following criteria:

Published from 2010 to 2020

Addressed health‐oriented collaboratives

Addressed at least two of three key sectors of interest (social services, public health and healthcare)

Articles were excluded if they identified or recommended collaboration but did not substantially discuss it in the core of the paper. Articles were also excluded if a version in English was unavailable. Disagreements about inclusion and exclusion were resolved in conference, and documents were included where disagreements could not be resolved.

2.2. Systematic scan of key journals

Using the academic search engine scans as a guide, four journals were identified as being particularly relevant to the project. These include Health & Social Care in the Community, the International Journal of Integrated Care, Social Work in Public Health, and the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as with the academic search engines (above).

2.3. Purposive scan

The research team employed several purposive strategies to leverage the relevant professional networks of RWJF and the authors. These strategies included reviewing documents of interest identified by RWJF, such as those used in the preliminary development of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change; conducting a systematic scan of the RWJF website for relevant work on cross‐sector alignment, including a search for projects in the Grants Explorer database which contained the text “align;” scanning for reports on the websites of key contacts and organisations identified throughout the project; collecting key documents identified through RWJF's and the authors' contacts encountered before and during the project; and searches on general search engines using the terms above. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as above. Notably however, we follow Arksey and O'Malley (2005) in including papers that came from a wide variety of sources besides academic journals and that came in a number of different formats including reports, briefs and conference presentations.

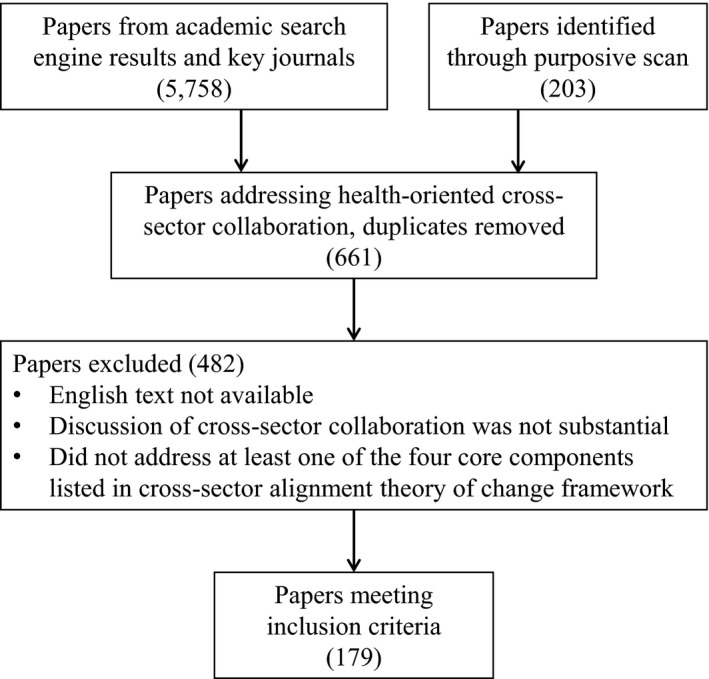

2.4. Coding

The results below are based on 179 documents identified as substantially addressing one of the four core areas of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change. A PRISMA diagram is presented in Figure 2. Information for each document was collected in a data extraction matrix, including author; year; title; type of document; key contributions identified in abstracts; findings and conclusions; whether each component of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change was addressed; key findings related to the main elements of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change; the evidence basis of the key contributions; what outcome measures were used if any; and who funded the work. Key contributions from each document were then thematically coded, assessed for their relevance to the four core areas of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change and organised into sub‐themes, which constitute the findings below.

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA diagram for the four core areas of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change

3. RESULTS

Research on cross‐sector collaboration is still in an early phase. Most of the studies reviewed were programme evaluations and were based on qualitative interviews with a small number of experts from convenience samples. This method limited the ability of these studies to test theory. However, it is well suited to theory building and the generation of hypotheses that can be tested in future research. The findings therefore represent a rich source of ideas for practitioners to consider. They also provide a foundation for future research on the cross‐sector alignment theory of change by offering a starting point for studies that assess causal relationships and consider variations in context. Most significantly, this body of literature provides a starting point for such research by identifying important challenges for collaboratives as well as strategies for overcoming these challenges. Specifically in regard to the four core areas of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change, this review revealed considerable nuance as well as several important considerations for each core area.

3.1. Shared purpose

Out of the 179 documents included in the literature review, 41 contained information directly relating to shared purpose. As with each of the four core areas discussed in this review, several papers cautioned against overemphasising shared purpose, while most viewed it as helpful or even critical for collaboration.

Among those suggesting caution should be taken, several suggested that organisational differences should be kept in mind so that collaboratives remain responsive to the diverse goals of participating organisations (Beers et al., 2018; Browne et al., 2016; Kyriacou & Vladeck, 2011; Willis et al., 2015). Others noted that the process of developing shared purpose can slow collaboration (Amarasingham et al., 2018; Clavier et al., 2012; Davis & Tsao, 2015; Hearld & Alexander, 2018; Hearld et al., 2018, 2019).

The remaining papers viewed the development of shared purpose as useful for overcoming challenges that collaboratives often face. These challenges usually concerned problems with different organisations starting in different places and moving in different and sometimes conflicting directions. The papers we reviewed tended to focus on methods and timing for developing a sense of shared purpose.

3.1.1. Methods and timing for developing a sense of shared purpose

The papers reviewed varied widely in their recommendations for how to achieve a sense of shared purpose. Several suggested implementing structured planning processes and connecting accountability measures to shared purpose (Mahlangu et al., 2017; Nichols et al., 2017; Spencer & Freda, 2016; Zahner et al., 2014). Others suggested less formal tactics, recommending flexible or organic approaches to the development of a sense of shared purpose (Dalton et al., 2019; Kritz, 2017). This may be difficult depending on who is included in this process. Several papers suggested that the process of developing a sense of shared purpose should include community members, especially during planning and agenda setting (Association for Community Health Improvement, American Hospital Association, & Public Health Foundation, n.d.; Mt. Auburn Associates, 2014; Sirdenis et al., 2019).

Opportunities to include the community often emerge during community health needs assessments and in the development of community health improvement plans (van Eyk et al., 2019; George et al., 2019), but importantly, collaboratives can also expand focus beyond healthcare settings by focusing on SDoH (Clavier et al., 2012) and addressing population‐level outcomes (Kyriacou & Vladeck, 2011). Working to develop a sense of shared purpose with the community or other partners may help build trust among the stakeholders involved, and several papers suggested that building trust will likely help partners collaborate (Khayatzadeh‐Mahani et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; Scutchfield et al., 2016; Shrimali et al., 2014; The Health Foundation, 2012; Valaitis et al., 2018).

Most likely, the relationship is circular, with increased trust also helping partners develop a sense of shared purpose. This raises questions about timing. Most of the papers addressing timing suggested developing shared purpose at the initiation of a collaboration (Baum et al., 2017; Cashman et al., 2012; Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation, 2017; Center for Sharing Public Health Services & Public Health National Center for Innovations, 2019, 2011; Freda, 2017; Freda et al., 2018; Humowiecki et al., 2018; Mahlangu et al., 2019; Nakagawa et al., 2015; Partnership for Healthy Outcomes, 2017; Scally et al., 2017; Siegel et al., 2015; Turner, 2016). However, the beginning may not be soon enough. One study suggested that drawing on relationships already in place might kick‐start the development of a sense of shared purpose, which in turn leads to collaboration (Crooks et al., 2018).

3.2. Governance

Out of the 179 documents included in the literature review, 61 contained information directly relating to governance. Two of the papers reviewed were sceptical of an emphasis on governance. Ovseiko et al., (2014) suggest that, within a collaborative, the idea of governance may be more important than governance itself. Holt et al., (2018) were concerned about dedicating too many resources to governance, suggesting that, even where structures are reorganised across sectoral boundaries, new boundaries will inevitably be created.

The remaining papers view governance as critical for effective functioning across organisations. Most of the governance strategies discussed concerned either institutionalisation or roles specifically. As with shared purpose, the underlying goal tended to be providing order for the collective enterprise, bringing the collective into focus as a thing in itself.

3.2.1. Institutionalisation

Several strategies involved advanced planning, for example, defining project scope, identifying a model for action and laying out standard procedures (Baker et al., 2012; van Duijn et al., 2018; Esparza et al., 2014; Kassianos et al., 2015; Khayatzadeh‐Mahani et al., 2018; Lillefjell et al., 2018; Public Health Leadership Forum, 2018). Narrowing the focus of the collaborative was also recommended, as was focusing on structures and systems (Chutuape et al., 2015). Several papers proposed focusing on understanding local systems already in place (Rasanathan et al., 2018). Collaboratives can build on these (Kyriacou & Vladeck, 2011; Vermeer et al., 2015), adding new layers of contracts, agreements, incentives and expectations (Erwin et al., 2016; Sabina, 2019). Agreements can be formal or quasi‐formal (Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017a; Shrimali et al., 2014), but in either case they are likely to help define expectations, align incentives and align services (Brewster et al., 2018; Rudkjobing et al., 2014).

Transparency and inclusiveness were common subjects. One paper recommended reductions in bureaucratic barriers to data and information, as with Medicaid managed care data that is held by managed care organisations (Gottlieb et al., 2016). Websites and frequent meetings were also recommended (Heo et al., 2018). Others recommended transparent agendas, budgets and role definitions (van Duijn et al., 2018; Eckart et al., 2019; Green et al., 2014; Hedberg et al., 2019; Ho et al., 2019; Kennedy et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2012).

For promoting inclusiveness, distributed leadership was recommended, especially for the period of time after a collaborative's initiation when strong central leadership may be more important (Rasanathan et al., 2018). Several papers recommended group problem solving and working from consensus across partners (Calancie et al., 2017; Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017a). Targeting outcomes that have a visible impact on the surrounding community may also help demonstrate attentiveness to community needs (Vermeer et al., 2015).

Notably, contracts were in some places criticised for their bilateral nature (Brewster et al., 2018), suggesting that while contracts are often considered important (see above), they may not be appropriate in all cases if they create unproductive trade‐offs in inclusiveness.

At a tactical level, the development of work groups and task forces was recommended (Tsuchiya et al., 2018). Implementing wrap‐around services was also suggested as a pathway to coordinated efforts (Pires & Stroul, 2013). Building the human capacity of individuals was also recommended. In one case, professionalised leadership was recommended (Buffardi et al., 2012). In another, dedicated administrative functions were recommended (Grudinschi et al., 2013).

Time management was a key concern in several studies, even to the extent that several papers suggested avoiding some forms of institutionalisation. For example, it was suggested that avoiding complex legal arrangements may save time in the short run and that alternative agreements may be sufficient (Corbin et al., 2018; Freda, 2017; Ovseiko et al., 2014).

Time was also important in that change management was a recurring theme. Formal change management processes were recommended (The Health Foundation, 2012), and processes for continuous improvement, monitoring and learning were recommended (Corbin et al., 2018; van Duijn et al., 2018; Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017a; Pires & Stroul, 2013).

3.2.2. Roles

Another common theme was the emphasis placed on roles. Several individual and organisational roles were discussed, including collaborator or partner organisations, leadership committees, funders, conveners, implementers and data managers, community representatives and individual leaders.

For collaborators, or partners in a collaborative, recommendations included building leadership within individual organisations, building collaborative relationships up front, engaging in training, experimentation and fostering partnership values (van Duijn et al., 2018; Fernandez et al., 2016; Kanste et al., 2013; Khayatzadeh‐Mahani et al., 2018; Laar et al., 2017; Lillefjell et al., 2018; Mt. Auburn Associates, 2014; Partnership for Healthy Outcomes, 2017; Southby & Gamsu, 2018). For leadership committees, suggested strategies included connecting partners, setting strategy, guiding group work and enforcing accountability (Curry et al., 2013; McKay & Nigro, 2017; de Montigny et al., 2019). Strategies for funders included providing funding, providing incentives and synchronising across grantees (Center for Sharing Public Health Services & Public Health National Center for Innovations, 2019, 2011; Clary et al., 2017).

Conveners, or backbone organisations, were linked to a wide variety of strategies. They were considered well positioned to provide momentum for the collaborative, facilitate interaction, help create a shared vision, develop strategy, build public will, promote transparency, facilitate convenings, manage the budget, engage the target community, facilitate information and resource sharing, build trust and help develop management practices (Center for Sharing Public Health Services & Public Health National Center for Innovations, 2019, 2011; Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017a; Hoe et al., 2019; Mongeon et al., 2017; Spencer & Freda, 2016).

At the front line, recommendations for implementers, care coordinators and data managers included avoiding overwork and offering training (Higuchi et al., 2017; Ho et al., 2019; Holland et al., 2019). Co‐location was recommended in some cases (Hunt, 2019), but its effectiveness was viewed with scepticism by others, especially where there are not added directives and incentives for collaboration (Kousgaard et al., 2019; Scheele & Vrangbaek, 2016).

Community members can contribute in many ways, for example, by helping develop priorities, contributing to programme design, contributing to implementation and contributing to evaluation (Fastring et al., 2018; Humowiecki et al., 2018; Kuo et al., 2018; Sirdenis et al., 2019; Vermeer et al., 2015).

Of all the roles, leadership was discussed most often. Leaders are well positioned to create a shared sense of purpose, promote and maintain a big‐picture focus, create a climate of problem solving, find resources, bring in strategic partners and implement change management (Baker et al., 2012; Gehlert et al., 2010; Mays & Scutchfield, 2010; Tsuchiya et al., 2018; van Dijk et al., 2019; Wallace et al., 2012). The term strong leadership was observed often, though this was not systematically defined and was taken to mean different things by different authors, sometimes referring to more directive leadership and sometimes referring to more facilitative leadership. This highlights a need for research on types of collaborative leadership as well as the context of collaboration and leadership. The weight given to leadership also raises questions about the relative roles and impacts of structured institutions versus leadership.

3.3. Finance

Of the 179 documents included in the literature review, 49 discussed collaborative finance. Most implied or stated that emphasising financing is generally a benefit to collaboratives, though again, several papers suggested this assumption may not always hold. Perhaps most importantly, financing often comes with restrictions (Fisher & Elnitsky, 2012). In some cases, cuts in funding brought focus to collaboratives (Kennedy et al., 2019; Zahner et al., 2014) or were themselves a catalyst for collaboration (Cantor et al., 2015a).

The remaining papers considered an emphasis on financing to be critical for addressing the challenges collaboratives face, especially regarding fiscal capacity and accountability. They focused primarily on obtaining funding and managing resources.

3.3.1. Obtaining funding

The financing mechanism most addressed was grants. Grants are critical for most collaboratives and were perhaps unsurprisingly recommended by many authors (Au‐Yeung et al., 2019; Bell et al., 2019; Cheadle et al., 2019; Freda et al., 2018; Hargreaves et al., 2017; Kyriacou & Vladeck, 2011; Lapiz et al., 2012; Mitchell et al., 2018; RTI International, 2018). Notably however, several papers identified problems with grants such as their tendency to last for only a short period. For that reason, several papers recommended obtaining long‐term grants (Erickson et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017; Mt. Auburn Associates, 2019), transitioning from grants after a start‐up period (Au‐Yeung et al., 2019; Freda et al., 2018) or diversifying funding sources, for example by securing investments from private donors (Hiatt et al., 2018) or by obtaining funds from stakeholders that are likely to benefit from the collaborative (Cantor et al., 2015a). Pooling funds, or blending and braiding funds from multiple sources, was also suggested in several papers (Cantor et al., 2019; Clary & Riley, 2016; Fisher & Elnitsky, 2012; McGinnis et al., 2014; Mt. Auburn Associates, 2014; Scally et al., 2017).

Working together, in itself, may help organisations obtain funding. Networking and collaboration with communities and other partners were identified as processes that can help organisations identify and obtain funding since these activities draw together diverse ideas and require organisations to develop effective value statements (Carney et al., 2014; Mt. Auburn Associates, 2019).

At a broader level, implementing tax‐exempt status for hospital community benefit dollars was also recommended (Scutchfield et al., 2011).

3.3.2. Managing resources

An important task for collaborating organisations is determining how resources will be used. A common theme was the recommendation to allocate funds to collaboration itself or to incentivising collaboration (Brandt et al., 2019; Eckart et al., 2019; Gyllstrom et al., 2019; Henize et al., 2015; Kindig & Isham, 2014; L&M Policy Research, 2018; Prevention Institute, 2018, n.d.).

Incentives were discussed in many papers addressing finance. Incentives were discussed in regard to performance‐based payment systems (Association of State & Territorial Health Officials, 2017; Cantor et al., 2015b; ChangeLab Solutions, 2015; Goldberg et al., 2018; Kleinman et al., 2017; Lantz & Iovan, 2018; Lin & Houchen, 2019; Mongeon et al., 2017). Strategies for implementing performance‐based payment systems included implementing community wellness funds, Medicaid waiver demonstrations, social impact bonds, hospital community benefit programmes, value‐based purchasing and capitated care plans, where payments are defined before services are requested or provided (Association of State & Territorial Health Officials, 2017; Goldberg et al., 2018; Kleinman et al., 2017; Mongeon et al., 2017).

While performance‐based systems have intuitive appeal and there are cases that suggest they can be effective, it is noteworthy that performance‐based systems were generally discussed in terms of cost savings. Accountability systems were typically not very strong, and quality measures were often ignored. Thus, performance‐based systems do not always meet the high expectations many have for them.

Another series of financing strategies emphasised inclusiveness. For example, one paper suggested including community voice and the voice of non‐health partners in finance decisions (Heinrich et al., 2020). Another paper suggested that transparent finances would help build trust (Cantor et al., 2015a).

Several of the papers we reviewed addressed financing in relation to policy. Policies funding preventive care were considered important (Gottlieb et al., 2016). Several papers also called for the implementation of policies that encourage collaborative finance, such as the ACA (Abbott, 2011; Abraham et al., 2019; Cramm et al., 2013; Heider et al., 2016; Lin & Houchen, 2019; Maxwell et al., 2014; Scutchfield et al., 2011; Stanek & Takach, 2015). Others suggested taking advantage of underutilised flexibilities in existing policies, for example with the flexibilities that managed care organisations have under the Medicaid programme (Goldberg et al., 2018). Notably however, another suggestion was to maintain systems such as traditional fee‐for‐service Medicaid, where direct payments from funders are used for services instead of funds passed through collaborative sources. The latter may be especially helpful where consumer autonomy would be helpful in managing complex care (Gridley et al., 2014).

3.4. Data and shared measurement

Out of the 179 documents included in the review, 75 addressed shared data and measurement. While several papers noted that data systems can be resource intensive, most concluded that shared data and measurement provide significant benefits, especially in terms of identifying need and assessing programme effectiveness. These papers generally focused on three topics: uses for shared data, obtaining data and bringing data systems together across organisations.

3.4.1. Uses for shared data

One of the most common uses for data is identifying needs, gaps and opportunities (Chandran et al., 2019, 2011; Harper et al., 2018; Hawk et al., 2015; Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017b; Henize et al., 2015; Heyman & McGeough, 2018; Klaiman et al., 2016; Mays & Scutchfield, 2010; Mikkelsen & Haar, 2015; O'Malley et al., 2017; Pires & Stroul, 2013; Reyes & Meyer, 2019; Scally et al., 2017; Shahzad et al., 2019; Spencer & Freda, 2016; Spencer & Hashim, 2018a; The National Center for Complex Health & Social Needs, 2018a). Often, using data to identify need involves finding specific locations or ‘hot spots’ in need of focused interventions (Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017a; Jacoby et al., 2018; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016).

Recommended practices include linking data to an evaluation plan and tying data to collaborative goals (Bodurtha et al., 2017; Connolly et al., 2016; Koo et al., 2016; Public Health Leadership Forum, 2018; Scally et al., 2017; Siegel et al., 2015). Ultimately, data linked in this way can be used to implement feedback loops, where needs, efforts and outcomes are tied together cyclically to assess progress (Beers et al., 2018; Browne et al., 2016; Center for Health Care Strategies & Nonprofit Finance Fund, 2018; Center for Sharing Public Health Services & Public Health National Center for Innovations, 2019, 2011; Chandran et al., 2019, 2011; Corbin et al., 2018; Costenbader et al., 2018; Davis & Tsao, 2015; Fastring et al., 2018; Fuller et al., 2015; Gottlieb et al., 2019; Jones, 2018; Prevention Institute, 2018; Public Health Leadership Forum, 2018; Spencer & Freda, 2016).

Such data could also be used to bring in investors or new partners (Fernandez et al., 2016). For example, data being used in a feedback loop can be used to demonstrate impact to outside parties (Mattessich & Rausch, 2014). Collaboratives also can create online dashboards to help orient partners (Nemours, 2012), share data with policy advocacy partners (Bull et al., 2015; de Leeuw, 2017; Rodriguez et al., 2015; Tsai & Petrescu‐Prahova, 2016) or work with researchers on theoretical research, providing a firmer basis for practice across the entire field (Bodurtha et al., 2017; Liljas et al., 2019; Liljegren, 2013; Maxwell et al., 2014; Rasanathan et al., 2018; Spencer & Freda, 2016).

3.4.2. Obtaining data

Health data often come from healthcare providers (Mikkelsen & Haar, 2015), but in the context of cross‐sector collaboration, useful data can come from a variety of sources including interviews, surveys and information systems from the full range of involved partners (Bull et al., 2015). A mix of data sources can address a variety of levels, for example the individual level (Discern Health, 2018; Sabina, 2019) or community level (Sreedhara et al., 2017).

Outcome measures were recommended in many of the documents reviewed (Cantor et al., 2015b; Fastring et al., 2018; Humowiecki et al., 2018; Rediger & Miles, 2018; Riazi‐Isfahani et al., 2018; Scally et al., 2017; Schulman & Thomas‐Henkel, 2019). Some papers recommended direct measures of health outcomes (Scally et al., 2017), even if these measures are difficult to obtain (van Dijk et al., 2019). Other papers suggest using indirect measures or proxies where necessary (Brewster et al., 2019; Humowiecki et al., 2018; Kozick, 2017; Rediger & Miles, 2018; Schober et al., 2011; Spencer & Freda, 2016; Vickery et al., 2018). Measures that reflect realistic goals were suggested (McGinnis et al., 2014), and one paper cautioned against developing too many indicators (Siegel et al., 2015).

Collaborating organisations can obtain data in simple forms, for example from publicly available sources or shared spreadsheets (The National Center for Complex Health & Social Needs, 2018b). However, obtaining data is often complex, and obtaining end‐user data can be particularly challenging. There were several recommendations for overcoming such challenges, for example by obtaining consent for follow‐on services during an initial service encounter (Mongeon et al., 2017; Spencer & Hashim, 2018b). Others recommended developing ways of providing services to those who are unable to give consent (The National Center for Complex Health & Social Needs, 2018c).

3.4.3. Bringing data systems together

Shared data systems require investment (Hawk et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2017). To make the most of these investments, collaborating organisations might consider engaging with partners, members of the community and front‐line workers or volunteers when designing their systems (Mikkelsen & Haar, 2015; Spencer & Hashim, 2018b; The National Center for Complex Health & Social Needs, 2018c). Also, data governance processes will also have to be established (Connolly et al., 2016; Flood et al., 2015; Mongeon et al., 2017). These may need to include formal agreements and contracts (Kozick, 2017; Pires & Stroul, 2013; Public Health Leadership Forum, 2018). Because of the legal and technical complexities involved in sharing data, collaboratives may need to retain legal counsel with experience in information sharing (The National Center for Complex Health & Social Needs, 2018c).

Many of the papers reviewed discussed data interoperability. Standardised systems and data input tools were recommended (AcademyHealth & NRHI, 2018; Wong et al., 2017). Policies may be especially helpful in establishing standards. Several studies noted that data are more useful when synchronised across systems and shared in real time (AcademyHealth & NRHI, 2018; Brandt et al., 2019; Mikkelsen & Haar, 2015). Allowing data to flow in multiple directions was also recommended (Mikkelsen & Haar, 2015).

Ease of use can be a major challenge for shared data. Data can be especially difficult to manage and use among non‐experts. Data processes can be facilitated with written guides for practitioners and end users (Spencer & Hashim, 2018a; The National Center for Complex Health & Social Needs, 2018c). Backbone organisations may also be able to coordinate data processes (Brewster et al., 2018). Several studies recommended setting up IT support and case management systems for handling technical issues (Amarasingham et al., 2018; McGinnis et al., 2014).

Technical assistance may be especially important when systems are first initiated. Hospitals often have experience with data and can contribute technical expertise (Amarasingham et al., 2018), though several studies recommended developing technical capacity across organisations (Center for Healthcare Strategies & Nonprofit Finance Fund, 2018; Tab ano et al., 2017). Other studies recommended hiring specialist contractors (Jones, 2018; Spencer & Hashim, 2018a) or leveraging familiar consumer technology, for example tablets, online portals, cloud technology and push notifications (Center for Health Care Strategies & Nonprofit Finance Fund, 2018; Jones, 2018; Mahadevan & Houston, 2015; Schulman & Thomas‐Henkel, 2019; Spencer & Hashim, 2018b).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Shared purpose

Shared purpose was primarily discussed in terms of a thing to be established at a point in time, and very few papers addressed the development of shared purpose over time. Reflecting on the cross‐sector alignment theory of change, this highlights the importance of expanding the literature to address the over‐time development of, maintenance of or evolution of shared purpose. As partnerships evolve, how does the sense of shared purpose evolve with them? For now, this appears to be an open question, but as partnerships develop, leadership changes, and partnerships grow, for example by including new organisations or by increasingly involving community members, shared purpose may need to evolve in response.

Another theme that emerged across papers addressing shared purpose is that partners tend to have different starting points and different missions. How these different starting points and missions are best reconciled (or not) with a collective sense of shared purpose would appear to be an open question. For example, organisations in healthcare may find themselves in new roles as they increasingly concern themselves with SDoH, and those starting with public health and social services backgrounds will have unique challenges as they enter conversations and processes previously dominated by clinical concerns. Different organisations will likely have different pathways to the development of shared purpose.

4.2. Governance

The literature on governance primarily emphasises institutions and leadership. In the case studies we reviewed, one is often prioritised over the other. However, the literature as a whole suggests there may be a need to strategically balance the two. While many studies highlight the importance of charismatic leadership for the success or failure of collaboration, many others underscore the need for collaborative institutions that are able to function without relying on the intervention of leadership and that can survive, or even facilitate, changes in leadership.

Many of the concerns raised over leadership and institutionalisation reflect the tendency of the papers we reviewed to focus on the short term. Building robust institutions requires time and effort, and in the short term, emphasising leadership might help with flexibility, for example by bypassing time‐consuming institutionalisation processes and allowing the direction of resources to where they are most needed. Over time, however, the relative need for leadership and sustainable institutions may shift. For example, many studies described challenges in maintaining inter‐organisational relationships or a sense of shared purpose after charismatic leaders left or shifted focus. Those studies with an explicit focus on governance over time often emphasised the need for stable institutions like data sharing agreements, regularly scheduled interactions, contracts and change management processes. Such institutions may be critical for moving organisations in a short‐term collaborative towards sustained and effective alignment.

As with shared purpose, research on governance also makes it clear that different people will have different starting points. This is most obvious in the case of roles. The papers we reviewed identified many different roles, each of which signifies a different set of resources and a different set of strategies necessary for promoting effective and sustainable cross‐sector collaboration.

4.3. Financing

Financing can do more than fund services. It can also be used to provide incentives and promote accountability, though this is often challenging. The literature suggests that current approaches to accountability could be both more realistic and idealistic: realistic in that challenges with effective accountability are more difficult to overcome than many anticipate and idealistic in that the lack of funding seems often to be considered nearly fatal even while organisations with limited resources continue to do impressive work. Certainly, budget shortfalls are very real, and communities often suffer because of this, but much good can also be accomplished with creative use of available funds, even when they are not as plentiful as they could be (Cantor et al., 2015a; Kennedy et al., 2019; Zahner et al., 2014).

The literature also suggests that challenges associated with short‐term financing are a common concern. Collaboration can be time and resource intensive, and many papers identified problems with projects coming to an end before outcomes could be effectively demonstrated to funders or to the community. This may lead to wasted effort, the elimination of promising initiatives and a loss of trust in the eyes of the community.

In the case of financing at least, collaboratives do tend to have an eye on sustainability, and they have identified several strategies to develop sustainable financing. These include encouraging long‐term funding, diversifying funding, employing reinvestment strategies, advocating policy change and even making‐do. Nevertheless, sustainability still seems almost universally in question.

Importantly, things like long‐term financing, policy and resource availability will vary widely by context. This again underscores the fact that finance strategies will, in turn, almost necessarily vary across contexts.

4.4. Shared data

Shared data can help make a case to investors, facilitating financial assistance and buy‐in. Shared data can also either contribute to the creation of, or can be used to assess progress towards, goals reflecting a shared purpose. Shared data may also be useful for collective governance, where it can be used for decision making and for implementing accountability systems. Yet while shared data have many benefits, these can also have drawbacks. The requirement for technical capacity and resources can be intense. Legal issues in obtaining and sharing data can also create significant barriers. Often these barriers protect consumers, for example, by preventing the public release of personal medical records. Managing these barriers can take time and resources since it often requires negotiating contracts and dealing with the legal system, which can be time consuming and expensive.

Ethical and moral issues create challenges for data sharing. Data that are used legally can still be used in unethical ways either intentionally or unintentionally, for example when data are collected from community members and then are used in the interest of the party that collected the data rather than the community itself.

An organisation's starting point in terms of resources, legal capacity and experience with ethical data management will have a significant effect on its ability to share data. Notably however, even when there are significant challenges in sharing data, modest data sharing arrangements may still be surprisingly fruitful (The National Center for Complex Health & Social Needs, 2018b). Perhaps because of the intense resource investments often involved, shared data are conceived in terms of lasting collaboratives perhaps more often than some of the other core areas.

4.5. Implications for the cross‐sector alignment theory of change

With few exceptions, the papers we reviewed suggested that developing sustainable systems in the four core areas identified in the cross‐sector alignment theory of change is beneficial to collaboratives. Looking across the core areas, two themes emerged. First, there is a need to move towards research that emphasises sustainability. Research on shared purpose tends to conceive of it as being developed at a point in time, with little consideration for how shared purpose may evolve along with a collaborative. Research on governance often eschews institutionalisation, in part because it tends to focus on short‐term collaboration, though several papers did address sustainability by pointing out a need to consider changes over time and, specifically, change management. Research on finance regularly noted challenges securing sustainable funding, though effective ways of addressing these challenges have been difficult to identify and implement. Finally, papers addressing shared data seem relatively oriented towards sustainable systems, likely because many of the major challenges for shared data systems occur as the data systems are first being implemented and the investment is expected to pay off mostly in the long run.

Another theme from across studies is that starting points will greatly affect an organisation's approach to cross‐sector collaboration. Most organisations are going to come to the collaborative with unique missions, different resources and potentially divergent goals. Shared purpose may mitigate issues with divergent goals, but it cannot eliminate all of them. Organisations and individuals will also have meaningfully different starting points as a function of their different roles, for example, with convening organisations, funding organisations and organisations from different sectors each playing a different role in moving a collaborative towards its objectives. In terms of finance, geopolitical variations in long‐term financing arrangements and policies will necessarily shape how organisations in different contexts align. Relatedly, different organisations' approaches to shared data will vary considerably depending on the resources available.

4.6. Study limitations

While this is a scoping review designed to summarise a body of literature, identify common themes and point out opportunities for future research, and it is not intended to serve as an evaluation of the strength of individual papers or a narrow set of research findings as might be done in a Cochrane‐style review, we do consider it a limitation that stronger conclusions about the effectiveness of different solutions could not be made. Most studies in this review did not systematically assess the general efficacy of the strategies offered. Very rarely did they compare cases or theoretical explanations for differences between them. This long‐standing gap continues to need attention from both the research community and those practitioners involved with programme evaluation (Gottlieb et al., 2017; Winters et al., 2016). Future research should balance the theory‐building research that composes most of this study with research that systematically assesses causal relationships and compares competing theoretical explanations for observed outcomes. To move in this direction, it may also be helpful to root future research on health‐oriented cross‐sector collaboration in established theoretical paradigms, for example, in systems dynamics, organisational behaviour or medical sociology.

In terms of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change specifically, a second limitation is that this review cannot rule out the importance of factors besides the four core areas discussed here. This is an area that should be explored in future studies. Researchers should not feel constrained by these four core areas, and while the present study is not designed to be conclusive about the relative importance of key concepts, this review does identify several factors that may be attributed increasing importance in time. Examples noted above include contexts, pathways and resources, and others may eventually emerge.

4.7. Contribution

This paper makes several important contributions to the study of health‐oriented cross‐sector collaboration. First, this study successfully identified several themes across the papers reviewed. Consistent with the cross‐sector alignment theory of change, there is a need for a better understanding of the shift from short‐term collaboratives to sustained and effective collaboration. Second, this paper highlights the need for future versions of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change to account for the different pathways that will be taken by organisations with different resources in different contexts. Finally, this paper presents a host of practical strategies and observations that can be used in future theoretical and empirical research attempting to determine the best strategies for aligning across sectors. Some example strategies that could be used as a starting point include using the development of shared purpose as an opportunity to build a sense of trust among community stakeholders, using quasi‐formal agreements to clarify roles, diversifying funding portfolios and making front‐end investments in the user‐friendliness of data systems.

5. CONCLUSION

The papers we reviewed tend to suggest that development in the four core areas of the cross‐sector alignment theory of change is likely to help collaboratives, even if the optimal pathways to effective and sustainable cross‐sector alignment have to date been difficult to identify. Future research on the cross‐sector alignment theory of change should employ rigorous methods and account for varying starting points and pathways. Nevertheless, the literature on cross‐sector collaboration is already ripe with observations that identify important considerations for practitioners and that could be assessed systematically in future studies to produce firmer research foundations for practice models.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report in connection with this research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Christiana Oshotse, Kodasha Thomas, Ana LaBoy, Brandy Holloman, Eungjae Kim and participants of the research seminar at the Georgia Health Policy Center for their support on this project. We would also like to thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for providing financial support for this research.

Lanford D, Petiwala A, Landers G, Minyard K. Aligning healthcare, public health and social services: A scoping review of the role of purpose, governance, finance and data. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30:432–447. 10.1111/hsc.13374

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data for this study are available from the authors upon request.

REFERENCES

- Abbott, A. L. (2011). Community benefits and health reform. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 17(6), 524–529. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31822da124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A. J. , Smith, B. T. , Andrews, C. M. , Bersamira, C. S. , Grogan, C. M. , Pollack, H. A. , & Friedmann, P. D. (2019). Changes in state technical assistance priorities and block grant funds for addiction after ACA implementation. American Journal of Public Health, 109(6), 885–891. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AcademyHealth and NRHI . (2018). Fostering collaboration to support a culture of health: Update from five communities. AcademyHealth. [Google Scholar]

- Amarasingham, R. , Xie, B. , Karam, A. , Nguyen, N. , & Kapoor, B. (2018). Using community partnerships to integrate health and social services for high‐need, high‐cost patients. The Commonwealth Fund. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (2017). A transformed health system in the 21st century. A. o. S. T. H. Officials Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Association for Community Health Improvement, American Hospital Association, & Public Health Foundation . (n.d.). Taking action: Leveraging community resources to address mental health. Available from: https://www.healthycommunities.org/sites/default/files/achi/Case%20Study%20‐WellSpan.pdf [last accessed 30 March 2021].

- Au‐Yeung, C. , Blewett, L. A. , & Lange, K. (2019). Addressing the rural opioid addiction and overdose crisis through cross‐sector collaboration: Little falls, Minnesota. American Journal of Public Health, 109(2), 260–262. 10.2105/ajph.2018.304789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E. A. , Wilkerson, R. , & Brennan, L. K. (2012). Identifying the role of community partnerships in creating change to support active living. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(5), S290–S299. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, F. , Delany‐Crowe, T. , MacDougall, C. , Lawless, A. , van Eyk, H. , & Williams, C. (2017). Ideas, actors and institutions: Lessons from South Australian Health in All Policies on what encourages other sectors' involvement. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 10.1186/s12889-017-4821-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers, A. , Spencer, A. , Moses, K. , & Hamblin, A. (2018). Promoting better health beyond health care. Retrieved from, https://www.chcs.org/media/BHBHC_Report_053018.pdf .

- Bell, O. N. , Hole, M. K. , Johnson, K. , Marcil, L. E. , Solomon, B. S. , & Schickedanz, A. (2019). Medical‐financial partnerships: Cross‐sector collaborations between medical and financial services to improve health. Academic Pediatrics, 20(2), 166–174. 10.1016/j.acap.2019.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodurtha, P. , Siclen, R. V. , Erickson, E. , Legler, M. S. , Thornquist, L. , Vickery, K. D. , & Owen, R. (2017). Cross‐sector service use and costs among medicaid expansion enrollees in Minnesota's Hennepin County. Center for Health Care Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, H. M. , Vanderpool, R. C. , Curry, S. J. , Farris, P. , Daniel‐Ulloa, J. , Seegmiller, L. , Stradtman, L. R. , Vu, T. , Taylor, V. , & Zubizarreta, M. (2019). A multi‐site case study of community‐clinical linkages for promoting HPV vaccination. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(7–8), 1599–1606. 10.1080/21645515.2019.1616501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, A. L. , Brault, M. A. , Tan, A. X. , Curry, L. A. , & Bradley, E. H. (2018). Patterns of collaboration among health care and social services providers in communities with lower health care utilization costs. Health Services Research, 53(4), 18. 10.1111/1475-6773.12775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, A. L. , Tan, A. X. , & Yuan, C. T. (2019). Development and application of a survey instrument to measure collaboration among health care and social services organizations. Health Services Research, 54(6), 1246–1254. 10.1111/1475-6773.13206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne, K. O. , Graham, R. , & Siegel, B. (2016). Leading multi‐sector collaboration: Lessons from the aligning forces for Quality National Program Office. The American Journal of Managed Care, 22(12), S337–S340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffardi, A. L. , Cabello, R. , & Garcia, P. J. (2012). Toward greater inclusion: Lessons from Peru in confronting challenges of multi‐sector collaboration. Revista Panamericana De Salud Publica, 32(3), 245–250. 10.1590/S1020-49892012000900011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull, F. , Milton, K. , Kahlmeier, S. , Arlotti, A. , Juričan, A. B. , Belander, O. , Martin, B. , Martin‐Diener, E. , Marques, A. , Mota, J. , Vasankari, T. , & Vlasveld, A. (2015). Turning the tide: National policy approaches to increasing physical activity in seven European countries. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(11), 749–756. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calancie, L. , Stritzinger, N. , Konich, J. , Horton, C. , Allen, N. E. , Ng, S. W. , Weiner, B. J. , & Ammerman, A. S. (2017). Food policy council case study describing cross‐sector collaboration for food system change in a rural setting. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 11(4), 441–447. 10.1353/cpr.2017.0051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, J. , Powers, P. E. , & Masters, B. (2019). Establishing a local wellness fund: Early lesson from the California accountable communities for health initiative. California Accountable Communities for Health Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, J. , Tobey, R. , Houston, K. , & Greenberg, E. (2015a). Accountable communities for health: Strategies for financial sustainability‐April. JSI. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, J. , Tobey, R. , Houston, K. , & Greenberg, E. (2015b). Accountable communities for health: Strategies for financial sustainability‐May. JSI. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M. T. , Buchman, T. , Neville, S. , Thengampallil, A. , & Silverman, R. (2014). A community partnership to respond to an outbreak: A model that can be replicated for future events. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 8(4), 531–540. 10.1353/cpr.2014.0065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, S. B. , Flanagan, P. , Silva, M. A. , & Candib, L. M. (2012). Partnering for health: Collaborative leadership between a community health center and the YWCA central Massachusetts. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 18(3), 279–287. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182294fe7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Health Care Strategies, & Nonprofit Finance Fund (2018). Advancing partnerships between health care and community‐based organizations to address social determinants of health: Executive summary. 5. Retrieved from https://www.chcs.org/media/KP‐CBO‐Exec‐Summ__080918.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation . (2017). Health and human services integration: A report to the Kresge Foundation (p. 29). Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Healthcare Strategies & Nonprofit Finance Fund (2018). Advancing partnerships between health care and community‐based organizations to address social determinants of health: Executive summary. C. f. H. C. Strategies Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Sharing Public Health Services and Public Health National Center for Innovations . (2019). Cross‐sector innovation initiative: Environmental scan full report. C. f. S. P. H. Services & P. H. N. C. f. Innovations Eds. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran, A. , Puvanachandra, P. , & Hyder, A. (2011). Prevention of violence against children: A framework for progress in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Journal of Public Health Policy, 32(1), 121–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ChangeLab Solutions . (2015). Accountable communities for health legal & practical recommendations. 1–40. Retrieved from https://cachi.org/uploads/resources/ChangeLab‐Solutions_ACH‐legal‐recs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle, A. , Rosaschi, M. , Burden, D. , Ferguson, M. , Greaves, B. O. , Houston, L. , McClendon, J. , Minkoff, J. , Jones, M. , Schwartz, P. , Nudelman, J. , & Maddux‐Gonzalez, M. (2019). A Community‐wide collaboration to reduce cardiovascular disease risk: The hearts of Sonoma County initiative. Preventing Chronic Disease, 16, E89. 10.5888/pcd16.180596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape, K. S. , Willard, N. , Walker, B. C. , Boyer, C. B. , Ellen, J. , & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIVAIDS Interventions . (2015). A tailored approach to launch community coalitions focused on achieving structural changes: Lessons learned from a HIV prevention mobilization study. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 21(6), 546–555. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clary, A. , & Riley, T. (2016). Braiding and blending funding streams to meet the health‐related social needs of low‐income persons: Considerations for state health policymakers. National Academy for State Health Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Clary, A. , Riley, T. , Rosenthal, J. , & Kartika, T. (2017). Blending, braiding, and block‐granting funds for public health and prevention: Implications for states. National Academy for State Health Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Clavier, C. , Gendron, S. , Lamontagne, L. , & Potvin, L. (2012). Understanding similarities in the local implementation of a healthy environment programme: Insights from policy studies. Social Science and Medicine, 75(1), 171–178. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, K. , Finocchio, L. , Newman, M. , & Linkins, K. (2016). Accountable communities for health: An evaluation framework and user's guide.

- Corbin, J. H. , Jones, J. , & Barry, M. M. (2018). What makes intersectoral partnerships for health promotion work? A review of the international literature. Health Promotion International, 33(1), 4–26. 10.1093/heapro/daw061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costenbader, E. , Mangone, E. , Mueller, M. , Parker, C. , & MacQueen, K. M. (2018). Rapid organizational network analysis to assess coordination of services for HIV testing clients: An exploratory study. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Servicess, 17(1), 16–31. 10.1080/15381501.2017.1384779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramm, J. M. , Phaff, S. , & Nieboer, A. P. (2013). The role of partnership functioning and synergy in achieving sustainability of innovative programmes in community care. Health & Social Care in the Community, 21(2), 209–215. 10.1111/hsc.12008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, C. V. , Exner‐Cortens, D. , Siebold, W. , Moore, K. , Grassgreen, L. , Owen, P. , Rausch, A. , & Rosier, M. (2018). The role of relationships in collaborative partnership success: Lessons from the Alaska Fourth R project. Evaluation and Program Planning, 67, 97–104. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry, N. , Harris, M. , Gunn, L. , Pappas, Y. , Blunt, I. , Soljak, M. , Mastellos, N. , Holder, H. , Smith, J. , Majeed, A. , Ignatowicz, A. , Greaves, F. , Belsi, A. , Costin‐Davis, N. , Jones Nielsen, J. D. , Greenfield, G. , Cecil, E. , Patterson, S. , Car, J. , & Bardsley, M. (2013). Integrated care pilot in north‐west London: A mixed methods evaluation. International Journal of Integrated Care, 13(3), e027. 10.5334/ijic.1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, H. , Read, D. M. Y. , Booth, A. , Perkins, D. , Goodwin, N. , Hendry, A. , Handley, T. , Davies, K. , Bishop, M. , Sheather‐Reid, R. , Bradfield, S. , Lewis, P. , Gazzard, T. , Critchley, A. , & Wilcox, S. (2019). Formative evaluation of the Central Coast Integrated Care Program (CCICP), NSW Australia. International Journal of Integrated Care, 19(3), 15. 10.5334/ijic.4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R. A. , & Tsao, B. (2015). A multi‐sector approach to preventing violence: A companion to multi‐sector partnerships for preventing violence. A collaboration multiplier guide. Prevention Institute. [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw, E. (2017). Engagement of sectors other than health in integrated health governance, policy, and action. Annual Review of Public Health, 38, 329–349. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Montigny, J. G. , Desjardins, S. , & Bouchard, L. (2019). The fundamentals of cross‐sector collaboration for social change to promote population health. International Journal of Integrated Care, 26(2), 41–50. 10.1177/1757975917714036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckart, P. , Guardado, K. , Heishman, H. , Hernandez, A. , & Wight, D. (2019). Aligning for systems change: A conversation between funders and communities. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, J. , Milstein, B. , Schafer, L. , Pritchard, K. E. , Levitz, C. , Miller, C. , & Cheadle, A. (2017). Progress along the pathway for transforming regional health: A pulse check on multi‐sector partnerships. ReThink Health. [Google Scholar]

- Erwin, P. C. , Harris, J. , Wong, R. , Plepys, C. M. , & Brownson, R. C. (2016). The Academic Health Department: Academic‐Practice Partnerships among Accredited U.S. Schools and Programs of Public Health, 2015. Public Health Reports, 131(4), 630–636. 10.1177/0033354916662223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparza, L. A. , Velasquez, K. S. , & Zaharoff, A. M. (2014). Local adaptation of the National Physical Activity Plan: Creation of the Active Living Plan for a Healthier San Antonio. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 11(3), 470–477. 10.1123/jpah.2013-0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fastring, D. , Mayfield‐Johnson, S. , Funchess, T. , Egressy, J. , & Wilson, G. (2018). Investing in Gulfport: Development of an academic‐community partnership to address health disparities. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 12(1S), 81–91. 10.1353/cpr.2018.0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, M. A. , Desroches, S. , Turcotte, M. , Marquis, M. , Dufour, J. , & Provencher, V. (2016). Factors influencing the adoption of a healthy eating campaign by federal cross‐sector partners: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 16, 904. 10.1186/s12889-016-3523-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M. P. , & Elnitsky, C. (2012). Health and social services integration: A review of concepts and models. Social Work in Public Health, 27(5), 441–468. 10.1080/19371918.2010.525149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood, J. , Minkler, M. , Hennessey Lavery, S. , Estrada, J. , & Falbe, J. (2015). The collective impact model and its potential for health promotion: Overview and case study of a healthy retail initiative in San Francisco. Health Education & Behavior, 42(5), 654–668. 10.1177/1090198115577372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freda, B. (2017). Housing is a health intervention: Transitional respite care program in Spokane. Center for Health Care Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- Freda, B. , Kozick, D. , & Spencer, A. (2018). Partnerships for health: Lessons for bridging community‐based organizations and health care organizations. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, Center for Health Care Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, J. , Oster, C. , Muir Cochrane, E. , Dawson, S. , Lawn, S. , Henderson, J. , O'Kane, D. , Gerace, A. , McPhail, R. , Sparkes, D. , Fuller, M. , & Reed, R. L. (2015). Testing a model of facilitated reflection on network feedback: A mixed method study on integration of rural mental healthcare services for older people. British Medical Journal Open, 5(11), e008593. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert, S. , Murray, A. , Sohmer, D. , McClintock, M. , Conzen, S. , & Olopade, O. (2010). The importance of transdisciplinary collaborations for understanding and resolving health disparities. Social Work in Public Health, 25(3), 408–422. 10.1080/19371910903241124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, A. , LeFevre, A. E. , Jacobs, T. , Kinney, M. , Buse, K. , Chopra, M. , Daelmans, B. , Haakenstad, A. , Huicho, L. , Khosla, R. , Rasanathan, K. , Sanders, D. , Singh, N. S. , Tiffin, N. , Ved, R. , Zaidi, S. A. , & Schneider, H. (2019). Lenses and levels: The why, what and how of measuring health system drivers of women's, children's and adolescents' health with a governance focus. BMJ Global Health, 4(Suppl 4), e001316. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, S. H. , Lantz, P. M. , & Iovan, S. (2018). Expanding upstream interventions with federal matching funds and social‐impact investments under the 2016 Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, L. , Fichtenberg, C. , Alderwick, H. , & Adler, N. (2019). Social determinants of health: What's a healthcare system to do? Journal of Healthcare Management, 64(4), 243–257. 10.1097/JHM-D-18-00160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, L. , Garcia, K. , Wing, H. , & Manchanda, R. (2016). Clinical interventions addressing nonmedical health determinants in Medicaid managed care. American Journal of Managed Care, 22(5), 370–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, L. , Wing, H. , & Adler, N. (2017). A systematic review of interventions on patients' social and economic needs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(5), 719–729. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, A. , DiGiacomo, M. , Luckett, T. , Abbott, P. , Davidson, P. M. , Delaney, J. , & Delaney, P. (2014). Cross‐sector collaborations in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childhood disability: A systematic integrative review and theory‐based synthesis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13, 126. 10.1186/s12939-014-0126-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley, K. , Brooks, J. , & Glendinning, C. (2014). Good practice in social care for disabled adults and older people with severe and complex needs: Evidence from a scoping review. Health and Social Care in the Community, 22(3), 234–248. 10.1111/hsc.12063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudinschi, D. , Kaljunen, L. , Hokkanen, T. , & Hallikas, J. (2013). Management challenges in cross‐sector collaboration‐elderly care case study. Innovation Journal, 18(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gyllstrom, E. , Gearin, K. , Nease, D. , Bekemeier, B. , & Pratt, R. (2019). Measuring local public health and primary care collaboration. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 25(4), 382–389. 10.1097/phh.0000000000000809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R. L. , & Jacobson, P. D. (2018). Examining whether the health‐in‐all‐policies approach promotes health equity. Health Affairs, 37(3), 364–370. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, M. B. , Orfield, C. , Honeycutt, T. , Vine, M. , Cabili, C. , Coffee‐Borden, B. , Morzuch, M. , Lebrun‐Harris, L. A. , & Fisher, S. K. (2017). Addressing childhood obesity through multisector collaborations: Evaluation of a National Quality Improvement Effort. Journal of Community Health, 42(4), 656–663. 10.1007/s10900-016-0302-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper, K. , Abdi, F. , & Ne'eman, A. (2018). A State Multi‐Sector Framework for Supporting Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs. Child Trends. [Google Scholar]

- Hawk, M. , Ricci, E. , Huber, G. , & Myers, M. (2015). Opportunities for social workers in the patient centered medical home. Social Work in Public Health, 30(2), 175–184. 10.1080/19371918.2014.969862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health, D. (2018). Approaches to cross‐sector population health accountability. AcademyHealth. [Google Scholar]

- Health Research and Educational Trust . (2017a). Hospital‐community partnerships to build a culture of health: A compendium of case studies. Health Research and Educational Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Health Research and Educational Trust . (2017b). Social determinants of health series: Housing and the role of hospitals. Health Research and Educational Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Hearld, L. R. , & Alexander, J. A. (2018). Sustaining participation in multisector health care alliances: The role of personal and stakeholder group influence. Health Care Management Review, 45(3), 196–206. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearld, L. R. , Alexander, J. A. , Wolf, L. J. , & Shi, Y. (2018). Funding profiles of multisector health care alliances and their positioning for sustainability. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 32(4), 587–602. 10.1108/JHOM-01-2018-0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearld, L. R. , Alexander, J. A. , Wolf, L. J. , & Shi, Y. (2019). The perceived importance of intersectoral collaboration by health care alliances. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(4), 856–868. 10.1002/jcop.22158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg, K. , Bui, L. T. , Livingston, C. , Shields, L. M. , & Van Otterloo, J. (2019). Integrating public health and health care strategies to address the opioid epidemic: The Oregon Health Authority's Opioid Initiative. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 25(3), 214–220. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. , Kniffin, T. , & Rosenthal, J. (2016). State levers to advance accountable communities for health. National Academy for State Health Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, J. , Levi, J. , Hughes, D. , & Mittmann, H. (2020). Wellness funds: Flexible funding to advance the health of communities. 1–14. Retrieved from https://accountablehealth.gwu.edu/sites/accountablehealth.gwu.edu/files/Wellness%20Fund%20Brief%20‐%20Final.pdf

- Henize, A. W. , Beck, A. F. , Klein, M. D. , Adams, M. , & Kahn, R. S. (2015). A road map to address the social determinants of health through community collaboration. Pediatrics, 136(4), e993–1001. 10.1542/peds.2015-0549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo, H. H. , Jeong, W. , Che, X. H. , & Chung, H. (2018). A stakeholder analysis of community‐led collaboration to reduce health inequity in a deprived neighbourhood in South Korea. Global Health Promotion, 27(2), 35–44. 10.1177/1757975918791517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman, I. , & McGeough, E. (2018). Cross‐disciplinary partnerships between police and health services for mental health care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 25(5–6), 283–284. 10.1111/jpm.12471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt, R. A. , Sibley, A. , Fejerman, L. , Glantz, S. , Nguyen, T. , Pasick, R. , Palmer, N. , Perkins, A. , Potter, M. B. , Somsouk, M. A. , Vargas, R. A. , van ’t Veer, L. J. , & Ashworth, A. (2018). The San Francisco cancer initiative: A community effort to reduce the population burden of cancer. Health Affairs, 37(1), 54–61. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, K. S. , Davies, B. , & Ploeg, J. (2017). Sustaining guideline implementation: A multisite perspective on activities, challenges and supports. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), 4413–4424. 10.1111/jocn.13770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S. , Javadi, D. , Causevic, S. , Langlois, E. V. , Friberg, P. , & Tomson, G. (2019). Intersectoral and integrated approaches in achieving the right to health for refugees on resettlement: A scoping review. British Medical Journal Open, 9(7), e029407. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoe, C. , Adhikari, B. , Glandon, D. , Das, A. , Kaur, N. , & Gupta, S. (2019). Using social network analysis to plan, promote and monitor intersectoral collaboration for health in rural India. PLoS One, 14(7), e0219786. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland, D. E. , Vanderboom, C. E. , & Harder, T. M. (2019). Fostering cross‐sector partnerships: Lessons learned from a community care team. Professional Case Management, 24(2), 66–75. 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, D. H. , Carey, G. , & Rod, M. H. (2018). Time to dismiss the idea of a structural fix within government? An analysis of intersectoral action for health in Danish municipalities. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(22_suppl), 48–57. 10.1177/1403494818765705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, D. H. , Waldorff, S. B. , Tjørnhøj‐Thomsen, T. , & Rod, M. H. (2017). Ambiguous expectations for intersectoral action for health: A document analysis of the Danish case. Critical Public Health, 28(1), 35–47. 10.1080/09581596.2017.1288286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hood, C. M. , Gennuso, K. P. , Swain, G. R. , & Catlin, B. B. (2016). County health rankings: Relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(2), 129–135. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humowiecki, M. , Kuruna, T. , Sax, R. , Hawthorne, M. , Hamblin, A. , Turner, S. , & Cullen, K. (2018). Blueprint for complex care: Advancing the field of care for individuals with complex health and social needs. National Center for Complex Health and Social Needs, Center for Health Care Strategies, Institute for Healthcare Improvement. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, A. (2019). Consumer‐focused health system transformation: What are the policy priorities? Retrieved from https://www.healthcarevaluehub.org/events/consumer‐focused‐health‐system‐transformation‐what‐are‐policy‐priorities. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, S. F. , Kollar, L. M. M. , Ridgeway, G. , & Sumner, S. A. (2018). Health system and law enforcement synergies for injury surveillance, control and prevention: A scoping review. Injury Prevention, 24(4), 305–311. 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]