Abstract

This preregistered study examined whether child temperament and executive functions moderated the longitudinal association between early life stress (ELS) and behavior problems. In a Dutch population‐based cohort (n = 2803), parents reported on multiple stressors (age 0–6 years), child temperament (age 5), and executive functions (age 4), and teachers rated child internalizing and externalizing problems (age 7). Results showed that greater ELS was related to higher levels of internalizing and externalizing problems, with betas reflecting small effects. Lower surgency buffered the positive association of ELS with externalizing problems, while better shifting capacities weakened the positive association between ELS and internalizing problems. Other child characteristics did not act as moderators. Findings underscore the importance of examining multiple protective factors simultaneously.

Abbreviations

- BRIEF‐P

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function‐Preschool Version

- CBQ‐VSF

Children's Behavior Questionnaire‐Very Short Form

- CFI

comparative fit index

- ELS

early life stress

- RMSEA

root mean square error of approximation

- SRMR

standardized root mean squared residual

- TLI

Tucker‐Lewis index

- VIF

Variance inflation factor

It is increasingly clear that early life stress (ELS) can negatively impact the functioning of children later in life. For instance, children exposed to negative life events or parental psychopathology are at increased risk for subsequent emotional and behavioral difficulties (Bellis et al., 2019; Goodman et al., 2011). Such early risk factors have traditionally been studied in isolation. However, it is known that stressors tend to co‐occur (Appleyard et al., 2005; Evans et al., 2013). For example, psychopathology of mothers often occurs together with stressful life events (e.g., divorce, death in family), but also with socio‐economic strains. The extent to which child outcomes are negatively influenced seems to be a function of the number of risk factors present rather than the type of stressor (e.g., Mistry et al., 2010; Sameroff & Rosenblum, 2006). Moreover, cumulative risk factors are consistently found to explain more variance in children's outcomes than single factors (e.g., Atzaba‐Poria et al., 2004; Flouri & Kallis, 2007). In order to obtain a more complete understanding of the link between ELS and child outcomes, this study employed a broad, latent stress construct to capture the natural covariation of risk factors.

Fortunately, not every child exposed to ELS will develop poorly. In line with the differential reactivity model (Wachs, 1992), some children may be less susceptible to ELS than other children. Those children show resilience after stress exposure, demonstrating a relatively positive adaptation despite challenges and adversities (Luthar, 2006). Adaptation is considered positive if functioning in a domain (e.g., mental health) is better than expected given the level of adversity experienced. Several researchers agree that resilience is neither a fixed quality nor a unidimensional construct (e.g., Luthar, 2006; Rutter, 1999). Rather, it is a dynamic process with two distinct dimensions: risk and positive adaptation. From this perspective, resilience is never directly measured but instead is indirectly inferred from evidence of these two dimensions. Studying both risk and protective factors is essential for identifying possible targets for prevention programs among children at risk. Preventive interventions that teach children how to cope with current and future stressors may be most successful, as it is more (cost‐)effective to maximize positive development in young children, rather than intervening after mental health difficulties become established (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000).

Resilience in the context of cumulative ELS

Research on resilience has identified a variety of protective child characteristics that may buffer the impact of specific contextual stressors (Fritz et al., 2018; Zolkoski & Bullock, 2012). Of these characteristics, child temperament and executive functions are rather stable attributes that have each been repeatedly associated with resilience to specific adversities, such as poverty (Obradović, 2010) and maternal psychopathology (e.g., Davidovich et al., 2016). However, remarkably fewer studies examined protective child characteristics in the context of cumulative ELS (e.g., Agnafors et al., 2017; Flouri & Kallis, 2007; Sheinkopf et al., 2007). Furthermore, research on resilience has generally included single protective factors, whereas most children have access to multiple assets and resources that may facilitate resilience (Fritz et al., 2018; Zolkoski & Bullock, 2012). It is essential to investigate multiple potential protective factors simultaneously to better match the reality of most children's lives. Additionally, to identify possible pathways to positive adaptation, a longitudinal, prospective design is warranted (Luthar, 2006). Unfortunately, relatively few studies have used a longitudinal approach to examine resilience to cumulative ELS in multiple life domains (e.g., Boyes et al., 2016; Fisher et al., 2013; Miller‐Lewis et al., 2013; Northerner et al., 2016). In the current longitudinal study, we aimed to understand how children's characteristics, particularly temperament and executive functions, operate with cumulative ELS to predict behavior problems over time.

Temperament may be an important individual characteristic that determines how a child responds to the experience of ELS. Temperament has been defined as relatively stable, biologically based individual differences in emotional, motor, and attentional reactivity and self‐regulation (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). It has been suggested that temperament may alter the consequences of stress by moderating emotional states and ways of coping (Zimmer‐Gembeck & Skinner, 2016). Three broad temperament dimensions in childhood have repeatedly been identified in research: negative affect, surgency, and effortful control, mapping onto the Big Five personality traits of neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness, respectively (Caspi et al., 2005). First, negative affect refers to psychological instability and proneness to experience feelings of fear, frustration, and sadness (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Children high in negative affect may respond to environmental stressors with heightened arousal, appraisals of threat, and maladaptive coping. In contrast, low negative affect may buffer the effects of ELS. Second, effortful control is usually described as the ability to inhibit a dominant response to perform a subdominant response, enabling individuals to regulate their attention, emotions, and behaviors (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Children high in effortful control may be better able to manage negative emotions and behaviors in response to stress (Eisenberg et al., 2004). Third, surgency reflects a predisposition to be actively involved with the environment, to approach novelty, to enjoy intense activities, and to be sociable and impulsive (Putnam et al., 2001). High surgency has been related to lower levels of internalizing problems and higher levels of externalizing problems among children (e.g., De Pauw & Mervielde, 2010). On the one hand, higher surgency may decrease the risk for internalizing problems as sequela of ELS, for instance by enhancing active coping with stressors and approaching novel situations. On the other hand, higher surgency may increase the risk for externalizing problems in the context of stressors, for example, by being more impulsive and prone to acting out when faced with stress (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Empirical findings indicate that children with lower negative affect and higher effortful control are less adversely affected by contextual stressors, showing better behavioral functioning than other children (Lengua & Wachs, 2012). However, the role of surgency is less studied and still unclear. Some studies found that low surgency moderated (i.e., exacerbated) the association between negative parenting and child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, whereas other studies did not support any moderating effect (Slagt et al., 2016). Perhaps, the interactive effect of temperament traits and ELS on behavior problems depends on the developmental period, although it remains unknown what traits are the best markers for resilience across different ages (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000).

Only a few studies have examined the interaction between cumulative ELS with negative affect, effortful control, and surgency. In a high‐risk sample of predominantly African American preschoolers, negative affect exacerbated the link between cumulative ELS and internalizing problems (Northerner et al., 2016). Similarly, negative affect strengthened the relation between cumulative ELS and social competence in a high‐risk sample of ethnically diverse preschool boys (Chang et al., 2012). However, in a low‐risk community sample of school‐age children from ethnically diverse backgrounds, effortful control but not negative affect mitigated the effects of cumulative ELS on the occurrence (Lengua, 2002) and development (Lengua et al., 2008) of internalizing and externalizing problems. Of these studies, the only one that examined the role of surgency did not support any interaction between cumulative ELS and surgency when predicting internalizing and externalizing problems (Northerner et al., 2016). Yet, stressors related to poverty and the ethnic minority background of the sample may have played a more prominent role in the emergence of behavior problems as compared to children's surgency. These inconclusive findings suggest that the role of temperament in the context of stress may depend on sample characteristics such as the age, socioeconomic context, and ethnic background of children. Hence, it is important for studies examining the interplay between accumulated ELS and temperament traits to consider the potential role of children's age and ethnic background.

Executive functions have also been found to promote resilience across multiple domains in children exposed to contextual stress (Masten, 2007). Executive functions are cognitive functions involved in control of behavior, emotion, and cognition, including mental flexibility, working memory, planning, goal‐directed problem solving, and inhibitory control (Obradović, 2016). These cognitive information processing skills may be particularly adaptive in stressful environments, as children with higher levels of executive functioning are better able to regulate their emotions when facing challenges. As such, they are less likely to become aroused under stress and thus more likely to adapt effectively to stressful circumstances (Obradović, 2016; Taylor & Ruiz, 2019). Previous findings supported the idea that better executive functions in general (e.g., Horn et al., 2018; Masten et al., 2012), or higher levels of specific executive functions, such as inhibitory control, mental flexibility/shifting (e.g., Davidovich et al., 2016; Taylor & Ruiz, 2019), and emotional control (e.g., Lafavor, 2018; Miller‐Lewis et al., 2013), are related to resilience. However, since previous studies focused either on executive functions in general or on one or two single executive functions, it is still unclear which specific aspects of executive functioning are important for coping adaptively and hence which should be targets for intervention efforts. In most of the aforementioned studies, children's executive functions were assessed by neuropsychological tasks in structured settings. Although these performance‐based measures are useful to assess the processing efficiency of cognitive abilities in highly controlled conditions, it is valuable to additionally explore the role of children's executive functions in daily life (e.g., goal pursuit success), as can be assessed by rating measures (Toplak et al., 2013). For example, Miller‐Lewis et al. (2013) did examine parent‐ and teacher‐rated emotional control as a potential resource factor in the context of cumulative ELS and child behavioral outcomes. Despite the main effect of emotional control on child behavior problems, emotional control did not moderate the link between cumulative ELS and child behavior problems. As suggested by the authors, this finding might be explained by low power related to a relatively small sample size (n = 474) to conduct moderation analyses. Examining multiple executive functions simultaneously in an adequately powered sample may provide a more complete picture of the role of executive functions in the face of cumulative ELS in young children.

Thus, support exists for the role of child temperament and executive functions in resilience, although findings are not entirely consistent across studies. Recent work underscores the importance of controlling for the interrelation between protective factors, as some protective factors may only be significant when being tested in isolation, but not when being tested simultaneously with other protective factors (Fritz et al., 2018). From a theoretical perspective, it is particularly interesting to investigate the unique, independent roles of temperament traits and executive functions in resilience, given the diverse opinions regarding the conceptual differences and similarities between temperament, specifically the component of effortful control, and executive functions (Eisenberg & Zhou, 2016). Both effortful control and executive functions involve self‐regulation in the face of conflicting demands. Factor analyses showed that attentional focusing, inhibitory control, and perceptual sensitivity are among the components of effortful control, pointing to overlap between this temperament trait and specific executive functions (Rothbart et al., 2001). Yet, effortful control is typically considered part of the “hot” system of self‐regulation, specialized in quick emotional processing and reflexive reactions to emotionally laden stimuli, whereas executive functions are mainly involved in the “cool” system, concentrated on complex cognitive processing and reflective planning in response to neutral stimuli. Moreover, working memory is considered a core component of executive functions, but is usually not viewed as part of effortful control or temperament in general (Eisenberg & Zhou, 2016). Recent research including both temperament and executive functions as measured by questionnaires indicated these are related but distinct characteristics, which only partially overlap and contribute differentially to children's mental health problems (Drechsler et al., 2018). Researchers (e.g., Eisenberg & Zhou, 2016) now call for integrated studies that encompass both temperament and executive functions to reduce confusion and overlap in research. Hence, studies are needed that explore the unique contributions of temperament traits and executive functions to resilience within one study, taking into account their interrelatedness.

The current study

This study examined to what extent child temperament traits and executive functions buffer the relation between cumulative ELS and child behavior problems. We focused on ELS exposure and protective factors in early childhood, given that this period is marked by a high sensitivity to environmental influences (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000) and by the emergence, practice, and consolidation of coping, self‐regulation, and executive function skills (Zimmer‐Gembeck & Skinner, 2016). This study builds upon previous research by investigating the unique contributions of multiple protective factors, including parent‐reported temperament traits and executive functions, in combination with multiple risks in a large‐scale population‐based study. We employed a longitudinal, prospective design from birth to age 7 years using reports from mothers, fathers, and teachers to reduce possible rater bias, in contrast to previous work in which cumulative ELS, protective factors, and outcomes were often assessed concurrently (e.g., Lengua, 2002) and by a single reporter (e.g., Northerner et al., 2016). Finally, this study focused on both internalizing and externalizing problems as behavioral outcomes, as resilience may depend on the domain of outcome studied. Broad and multifaceted outcomes, such as internalizing and externalizing problems, consequently better approximate the idea of resilience than do narrower outcomes (Luthar, 2006).

Our first aim was to examine the longitudinal association between cumulative ELS (0–6 years) and internalizing and externalizing problems (7 years) in early childhood. We expected higher levels of cumulative ELS to be prospectively related to higher levels of child internalizing and externalizing problems. Our second aim was to examine whether parent‐reported temperament traits (5 years) and executive functions (4 years) acted as moderators of the association between cumulative ELS and internalizing and externalizing problems. Based on existing literature, we hypothesized that the association between cumulative ELS and internalizing problems was weaker for children with higher levels of surgency and effortful control, and lower levels of negative affect. Furthermore, we expected the association between cumulative ELS and externalizing problems to be weaker for children with lower levels of surgency and negative affect, and higher levels of effortful control. Regarding executive functions, we expected the association between cumulative ELS and internalizing and externalizing problems to be weaker for children with better executive functions in five domains: inhibition, shifting, emotional control, working memory, and planning/organizing. Finally, we additionally examined whether child temperament traits and executive functions uniquely moderated the association between cumulative ELS and internalizing and externalizing problems. Given previous findings supporting the notion that not one protective factor but complex interrelations of protective factors affect the link between ELS and mental health problems (Fritz et al., 2018), we expected that temperament traits acted as moderators when executive functions were controlled for, and vice versa, reflecting their unique contributions to resilience.

METHOD

Our study hypotheses, methods, and analysis plan were preregistered on the Open Science Framework; see https://osf.io/9xsn8. Any exploratory analyses or deviations from the planned methodology are clearly marked as such throughout the manuscript.

Design and study population

This study was embedded in the Generation R Study, a population‐based cohort from fetal life onwards. The design and sample characteristics of the study have been described in detail elsewhere (Kooijman et al., 2016). All pregnant women living in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, with a delivery date between April 2002 and January 2006 were invited to participate (response rate: 61%). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, approved the study.

In total, there were 7295 children whose main caregivers were enrolled in the postnatal phase of the Generation R Study. Information on cumulative ELS was collected by postal questionnaires at multiple time points when children were between 0 and 9 years old. We included all participants with data on at least 50% of items across stress domains (see Measures), one of the moderators (temperament traits or executive functions), and both outcome variables (internalizing and externalizing problems). Of the 7295 children that participated in the postnatal phase, 5992 children had available information on ELS. Subsequently, 3348 of these children's teacher reports were available on internalizing and externalizing problems at age 7 years (n = 2644, 44.1% lost to follow‐up). For 2803 of these children, data were available on either temperament traits at age 5 years or executive functions at age 4 years (n = 545, 16.3% lost to follow‐up). These 2803 children comprised the final sample. The nonresponse analyses showed that families in the final sample (n = 2803) did not differ from families that were not included (n = 3189) regarding the education level of mothers (χ 2(2) = 2.62, p = .269) and fathers (χ 2(2) = 0.57, p = .751), the distribution of child sex (χ 2(1) = 0.18, p = .669), and internalizing and externalizing problems of children at ages 1.5 and 3 years (t(4128–4159) = −0.19–1.18, ps = .237–.852). However, mothers (t(5983) = −7.83, p < .001) and fathers (t(5065) = −3.72, p < .001) of children in our study sample were slightly older, families had a higher income level (χ 2(2) = 15.97, p < .001), and children were more often of Dutch ethnicity (χ 2(2) = 46.08, p < .001) and had lower ELS scores (t(5982) = 8.32, p < .001), compared to those not included in the study.

To determine whether we had sufficient power to detect the interaction effects specified by our hypotheses, we ran Monte‐Carlo simulations in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Based on the main effects of, and correlations between, predictors in previous literature, we used βs of .20 and .30 in our simulations for the main effect of ELS on externalizing problems, while the βs for ELS on internalizing problems were set to .10 and .20. There was limited literature on the interaction effects of ELS with temperament traits or executive functions on internalizing and externalizing problems. We, therefore, set the size of interaction effects to 25%, 33%, and 50% of the size of the main effect of ELS, which are the realistic relative sizes according to recent studies into interaction effects (e.g., Simonsohn, 2015). Results indicated that our final sample (n = 2803) was likely to be sufficiently large to detect the interaction effects of ELS with temperament on externalizing problems at α = .05. Assuming the main effect of ELS on externalizing problems of β = .20, power was .73, .92, and 1.00 for interaction effects of 25%, 33%, and 50% the size of the main effect, respectively. Assuming the main effect of ELS on externalizing problems of β = .30, power was .97, 1.00, and 1.00 for interaction effects of 25%, 33%, and 50% the size of the main effect, respectively. For internalizing problems, power was likely a bit lower. Assuming the main effect of ELS on internalizing problems of β = .20, power was .73, .92, and 1.00 for interaction effects of 25%, 33%, and 50% the size of the main effect, respectively. Assuming the main effect of ELS on internalizing problems of β = .10, power was .24, .40, and .72 for interaction effects of 25%, 33%, and 50% the size of the main effect, respectively. Based on these results, any significant interaction effects between ELS and temperament traits/executive functions on internalizing problems should be interpreted with caution.

Characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. About 50% of the children were boys. The majority of the children were of Dutch origin (66.0%). Most of the mothers (60.1%) and fathers (60.9%) had college or higher education and were married or lived together (89.0%).

TABLE 1.

Child and family characteristics of study sample (n = 2803)

| Child characteristics | M (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Boys | 49.9% |

| Girls | 50.1% |

| Age at outcome, years | 6.68 (1.28) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Dutch | 66.0% |

| Non‐Dutch Western | 8.4% |

| Non‐Western | 25.6% |

| Family characteristics | Mothers | Fathers |

|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment, years | 31.52 (4.60) | 33.95 (5.34) |

| Education levela | ||

| Primary | 2.8% | 4.3% |

| Secondary | 37.1% | 34.9% |

| Higher | 60.1% | 60.9% |

| Family income/month | ||

| <€1200 | 5.3% | |

| €1200–2000 | 12.6% | |

| >€2000 | 82.0% | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living together | 89.0% | |

| Single/not living together | 11.0% | |

Parental education level was defined by the highest attained education, categorized as primary (elementary; typically from ages 4–12 years), secondary (13–17 years), and higher (college or university; ≥18 years).

Measures

Cumulative ELS

To measure cumulative ELS, main caregivers (range 89.2%–96.2% mothers, 3.2%–7.6% fathers, 0.5%–3.2% others) and their partners (91.4% fathers, 7.1% mothers, 1.5% others) reported on multiple questionnaires administered during childhood (0–9 years). Risk factors that occurred between 0 and 6 years of age were included, given the assessment of our outcome variables at age 7. We created an ELS construct based on a prenatal and postnatal stress construct developed by Cecil et al. (2014) in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children cohort. The prenatal stress construct has previously been implemented with good model fit using Generation R data in the Netherlands (Cortes Hidalgo et al., 2018; comparative fit index [CFI] > .90; Rijlaarsdam et al., 2016; χ 2(2) = 5.07, p < .079; CFI = 1.00, Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] = 1.00, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .01). In this study, we calculated a similar, postnatal latent stress construct, covering five conceptually distinct but related stress domains: life events (13 items; e.g., death in family, illness, work problems), contextual stress (8 items; e.g., financial difficulties, unemployment), parental stress (10 items; e.g., parental psychopathology, parental education level), interpersonal stress (9 items; e.g., family relationship difficulties, household size), and direct victimization (7 items; e.g., harsh parenting). See Table S1 for a detailed overview of instruments and items.

In line with a cumulative risk approach, items in all domains were dichotomized (0 = no risk, 1 = risk) based on previous literature or cut‐off values (for references, see Table S1). After that, a domain score was computed by adding the relevant items and dividing this by the number of completed items. Thus, higher scores represent greater stress exposure. We estimated a latent construct of cumulative ELS with the five stress domains as indicators in R (Lavaan Package version 0.6‐5; Rosseel, 2012). The internal structure of the ELS construct was examined by performing confirmatory factor analysis, showing good model fit, χ 2(5) = 26.04, p < .001; CFI = .97, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .04, standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) = .03 (Byrne, 2013). See the Supporting Information for descriptives of, and inter‐correlations between, stress domains (Table S2) and the confirmatory factor analysis model (Figure S1).

Child behavior problems

Child internalizing and externalizing problems were reported at age 7 by the child's teacher on the well‐validated Teacher's Report Form (TRF/6–18; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The items assessing internalizing (33 items, α = .85) and externalizing (32 items, α = .93) behaviors were answered on a 3‐point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true). We computed internalizing and externalizing problem scores by calculating the mean of the relevant items, with higher scores indicating more problems.

Child temperament

To measure child temperament, main caregivers (89.2% mothers, 7.6% fathers, 3.2% other) filled in the Children's Behavior Questionnaire‐Very Short Form (CBQ‐VSF; Putnam & Rothbart, 2006) at child age 5. The CBQ‐VSF consists of 36 items assessing three temperament scales (each 12 items): Surgency (α = .74), Negative Affect (α = .73), and Effortful Control (α = .70). Caregivers rated their child's reactions during the past 6 months on a 7‐point scale (ranging from 1 = extremely untrue of your child to 7 = extremely true of your child). A “not applicable” response option could be assigned when the child had not been observed in the described situation. Scale scores on the three temperament scales were created by calculating the mean of relevant item scores.

Child executive functioning problems

Problems in child executive functions were measured by main caregiver reports (88.4% mothers, 10.4% fathers, 1.3% other) on the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function‐Preschool Version (BRIEF‐P; Gioia et al., 2003) at child age 4. The BRIEF‐P consists of 63 items forming five theoretically and empirically derived scales: Inhibit (16 items, α = .88), Shift (10 items, α = .80), Emotional Control (10 items, α = .84), Working Memory (17 items, α = .89), and Plan/Organize (10 items, α = .77). Main caregivers indicated the extent to which their child had displayed the behavior during the last month on a 3‐point scale (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often). Scale scores reflect the mean scores on the relevant items, with higher scores indicating more problems in executive functions.

Covariate

As prior research indicates that ethnicity is related to the presentation and prevalence of both early life stressors (e.g., Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007) and child behavior problems (e.g., McLaughlin et al., 2007), we considered the inclusion of child ethnicity as a covariate in the analyses. The ethnicity of the child was categorized according to the classification by Statistics Netherlands (2018), which distinguishes Dutch, non‐Dutch Western, and non‐Western ethnicity, based on the country of birth of children themselves and their parents. Children were considered to have a non‐Dutch ethnic origin if one of their parents was born abroad. If both parents were born abroad, the country of birth of the child's mother determined the ethnic background. Main caregivers reported on the country of birth of both parents at child age 5. In addition, we considered including child age as a covariate, as the role of protective factors in the link between environmental stress and child outcomes may depend on child age (e.g., Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000; Slagt et al., 2016). Despite the results of our nonresponse analyses described above, we did not consider parental age and family income as covariates, since these were included as risk factors in the cumulative ELS score.

Statistical analyses

Preliminary analyses

First, assumptions on multivariate normality and multicollinearity were checked. Second, we computed descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables. Third, we tested for measurement invariance in R (Lavaan Package version 0.6‐5; Rosseel, 2012), to examine whether the meaning of the latent ELS construct was similar across boys and girls. Using multigroup models, equality constraints of the loadings, intercepts, and variances of the latent score were progressively implemented. To decide whether a more restricted model fit significantly worse than a less restricted model, three of four of the following criteria should be met: a significant Δχ 2(p < .05), a ΔCFI ≥ .010, a ΔRMSEA ≥ .015, and a ΔSRMR ≥ .030 (Chen, 2007). If the latent ELS score was measurement invariant across child sex, ELS exposure could be validly examined in an unstratified sample.

Main analyses

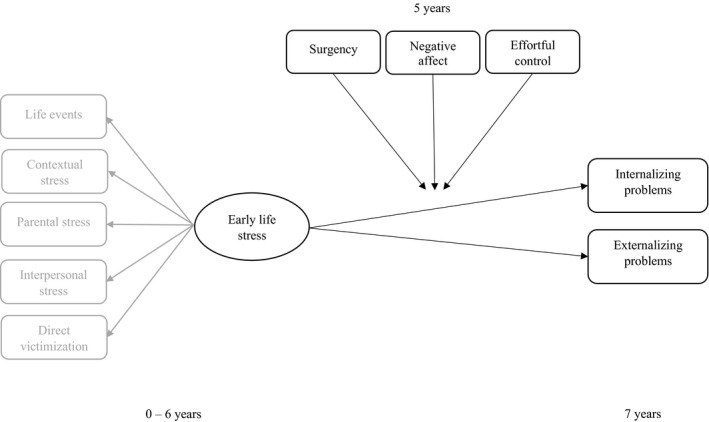

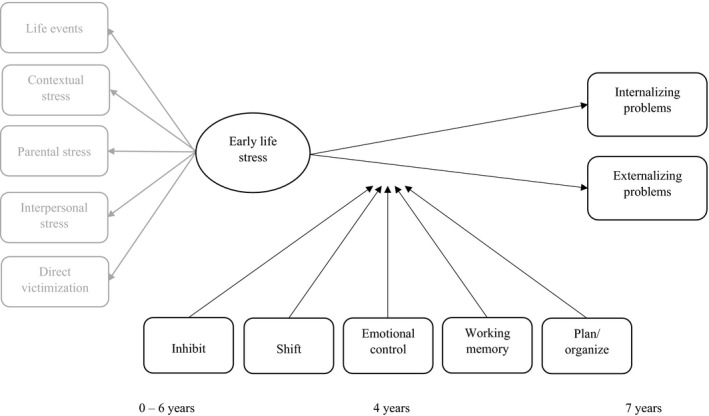

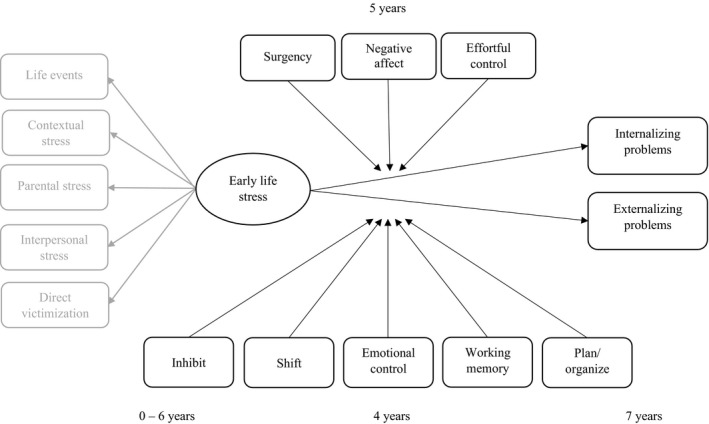

To examine our research questions, we tested four successive longitudinal regression models using structural equation modeling (see Figures 1, 2, 3, 4). Models were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and the Satorra–Bentler χ 2 statistic to account for non‐normality in our data. Due to model complexity (i.e., number of estimated parameters), we chose not to expand the measurement model with structural relations. Instead, we opted to extract the scores on the latent ELS construct based on the final measurement invariance model and use these extracted scores as observed predictors in the main analyses (not preregistered).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual Model 1 depicting the association between cumulative early life stress and child behavior problems

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual Model 2a depicting moderation by temperament traits

FIGURE 3.

Conceptual Model 2b depicting moderation by executive functions

FIGURE 4.

Conceptual Model 2c depicting moderation by temperament traits and executive functions

First, to examine the association between ELS and child outcomes (Model 1), the predictor was the extracted ELS score (0–6 years), and the outcome variables were child internalizing and externalizing problems (7 years). Second, to test whether temperament traits moderated the association between ELS and child outcomes, we created three centered (grand mean centering) interaction terms between ELS and the temperament traits (ELS × surgency, ELS × effortful control, ELS × negative affect). The temperament traits and their interaction terms were added as predictors to Model 1, resulting in Model 2a. Third, to investigate whether executive functions acted as moderators, five centered (grand mean centering) interaction terms were created between early ELS and the executive functions (ELS × inhibit, ELS × shift, ELS × emotional control, ELS × working memory, ELS × plan/organize). The executive functions and their interaction terms were added as predictors to Model 1, resulting in Model 2b. Fourth, in case of any significant interaction effect in Model 2a and/or Model 2b, we tested whether temperament traits and/or executive functions uniquely moderated the association between ELS and child outcomes, by including the interaction terms of both temperament traits and executive functions simultaneously within one model (Model 2c). In all models, standardized regression coefficients (β) and proportions of explained variances in the outcome variables (R 2) were used as measures of effect size. Model fit could not be evaluated, as all tested models were saturated.

To interpret the results of the moderation models in terms of resilience, the direction of the regression coefficient (positive or negative) for any significant interaction term was inspected. For example, a negative regression coefficient of the interaction term ELS × effortful control would indicate the association between early ELS and child behavior problems is weaker for children with higher levels of effortful control, suggesting that effortful control contributes to resilience to ELS. To follow‐up significant interaction effects, we conducted simple slope analyses to explore whether the association between the predictor (i.e., ELS) and outcome (i.e., child behavior problems) differed across levels of the moderator (–1 SD, M, and +1 SD). It was originally planned to also provide Johnson–Neyman intervals and plots to visualize the interaction effects. However, we considered Johnson–Neyman plots to be unusable given that our interaction effects were significant but small. We did not perform the preregistered multiple group analyses for sex, due to insufficient statistical power.

Child ethnicity and age were to be included as covariates in the analyses if these correlated significantly with ELS and both internalizing and externalizing problems and changed the effect estimates of the baseline model substantially (∆B > 10%). Results showed that child ethnicity and age were significantly related to ELS, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems (r range: .07–.39, ps < .001), but did not change the effect estimates of the baseline model substantially (∆B internalizing and ∆B externalizing both <10%). Therefore, we did not include child ethnicity and child age as covariates in the main analyses.

Missing data

For all instruments, weighted scale scores were used allowing a maximum of 25% missing item scores. Moreover, participants were allowed to have missing data at the maximum of 50% of ELS items and on one of the moderators (i.e., temperament traits or executive functions). The amount of missing data on ELS items ranged between 0% and 31.9% (M = 12.6%) and on moderators between 14.3% and 15.1% (M = 14.6%). We imputed the missing data by multivariate imputation by chained equations (not preregistered; Van Buuren & Groothuis‐Oudshoorn, 2010) using 30 imputed datasets and 60 iterations. Passive imputation was used for stress domains, implying that domain scores were computed by summing its ELS items and dividing this by the total number of items within that domain for each generated imputed dataset. Missing ELS items and moderators were imputed using information on ELS items (for missing ELS items only the items relevant to the domain), domain sum scores, internalizing and externalizing problems, and auxiliary variables (Van Buuren & Groothuis‐Oudshoorn, 2010). The auxiliary variables were maternal demographic variables during pregnancy (age, marital status, education level), and pregnancy characteristics (maternal BMI during pregnancy, parity, child gestational age and weight at birth, child ethnicity, and child sex).

Sensitivity analyses

To test the robustness of our findings, we tested Models 1–2c again using the stricter inclusion criteria that were originally preregistered. In these sensitivity analyses, participants were included with data on at least four of the five stress domains (and at least 75% of complete items per domain), both sets of moderators (temperament traits and executive functions), and both outcome variables (internalizing and externalizing problems), resulting in a sample of 1676 children. Missing stress domains were handled by using a full information maximum likelihood approach. This enabled us to test to what extent the results would hold if an alternative missing data strategy were used. Subsequently, we tested Model 2a and 2b again with less strict inclusion criteria regarding the moderators. Namely, participants with data available on ELS, child behavior problems, and on only one of the two moderators (Model 2a: temperament, n = 1757; Model 2b: executive functions, n = 1877) were included in these analyses.

RESULTS

Preliminary analysis

Results of assumption checking showed that the study variables were normally distributed, except for working memory, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems (range: skewness = 0.11–3.72, kurtosis = −0.15–26.12). Collinearity statistics did not point to multicollinearity between the predictors (range: tolerance = 0.30–0.99, Variance Inflation factor (VIF )= 1.01–2.79, condition index = 1.98–43.03), thus supporting the suitability of including the different predictors in one analysis.

Means and standard deviations of the variables and bivariate correlations between the variables are shown in Table 2. On average, children experienced 4.57 out of 46 risk factors (9.9%). ELS was positively and significantly correlated with child internalizing and externalizing problems, reflecting a small effect size. Furthermore, higher levels of ELS were significantly but weakly correlated with higher levels of negative affect and lower levels of effortful control, and with more difficulties in all five executive function domains. Lower levels of surgency and higher levels of effortful control were significantly correlated with higher levels of negative affect (small effects). The correlations between all executive function domains were positive and significant, ranging from small to large effect sizes. Finally, most correlations between temperament traits and executive function domains represented small to medium effects sizes.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics and spearman correlations for study variables (n = 2803)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ELSa | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Internalizing | .14*** | — | |||||||||

| 3. Externalizing | .21*** | .29*** | — | ||||||||

| 4. Surgency | .02 | −.16*** | .19*** | — | |||||||

| 5. Negative affect | .19*** | .14*** | .06** | −.17*** | — | ||||||

| 6. Effortful control | −.04* | −.01 | −.12*** | −.03 | .05* | — | |||||

| 7. Inhibit | .24*** | .04 | .20*** | .20*** | .24*** | −.19*** | — | ||||

| 8. Shift | .08*** | .16*** | −.04 | −.35*** | .31*** | .03 | .29*** | — | |||

| 9. Emotional control | .11*** | .11*** | .07** | −.07** | .40*** | −.03 | .52*** | .48*** | — | ||

| 10. Working memory | .25*** | .08*** | .14*** | .05* | .22*** | −.23*** | .71*** | .37*** | .44*** | — | |

| 11. Plan/organize | .23*** | .06** | .11*** | .02 | .23*** | −.20*** | .64*** | .32*** | .41*** | .75*** | — |

| M | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 4.41 | 3.70 | 5.29 | 1.38 | 1.36 | 1.42 | 1.27 | 1.37 |

| SD | 1.00 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.30 |

Abbreviation: ELS, early life stress.

ELS concerned a standardized, latent variable. Descriptive statistics for the observed indicators of ELS are displayed in Table S2.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Results of the analyses of measurement invariance across child sex are displayed in Supporting Information (Table S3). The ELS construct showed partial scalar invariance across child sex. A scalar invariance model in which loadings and intercepts (except for direct victimization) were constrained to be equal across sex did not fit significantly worse than a metric model in which loadings were constrained to be equal but all intercepts were freely estimated across boys and girls. The fit indices of the final partial invariance model indicated a good fit. The standardized loadings of the ELS construct on each stress indicator variable ranged from 0.09 (life events) to 0.72 (contextual stress).

Main analyses

Results of the structural equation models are shown in Table 3 and in the Supporting Information (Figures S2–S5). In Model 1, higher levels of ELS between ages 0–6 years were significantly associated with higher levels of teacher‐reported internalizing (β = .14) and externalizing problems (β = .22) at age 7. Concerning Model 2a, the results indicated a significant but small interaction effect of ELS and surgency on externalizing problems (β = .09). The positive association between ELS and externalizing problems became weaker as surgency levels declined. Simple slope analyses indicated that higher levels of ELS were significantly related to more externalizing problems at both high (+1 SD, B = 0.06, p < .001) and low levels of surgency (–1 SD, B = 0.03, p < .001). Negative affect and effortful control did not moderate the association between ELS and externalizing problems. Regarding child internalizing problems, no significant moderation effects by temperament were found. The results of Model 2b pointed to a significant but small interaction effect of ELS and shifting on internalizing problems (β = .09), although this result should be interpreted carefully because of power issues. The association between ELS and internalizing problems became weaker as shifting problems declined (i.e., with better shifting capacities). Simple slope analyses showed that higher levels of ELS were significantly related to more internalizing problems at both high (+1 SD, B = 0.01, p = .024) and low levels of shifting problems (–1 SD, B = 0.02, p < .001). No significant moderation effects by other executive functions were found. In Model 2c, in which both temperament traits and executive functions were included as moderators, the interaction effect of ELS and surgency on externalizing problems (β = .07) and of ELS and shifting on internalizing (β = .07) problems remained significant. In total, 4 out of 16 (25%) interaction tests were significant.

TABLE 3.

Regression parameters of the four structural equation models predicting internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (n = 2803)

| Internalizing problems | Externalizing problems | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | β | R 2 | B | SE | p | β | R 2 | |

| Model 1 | .02 | .05 | ||||||||

| ELS | 0.02 | 0.003 | <.001 | .14 | 0.05 | 0.01 | <.001 | .22 | ||

| Model 2a | .06 | .09 | ||||||||

| ELS | 0.02 | 0.003 | <.001 | .11 | 0.04 | 0.01 | <.001 | .20 | ||

| ELS × surgency | 0.002 | 0.003 | .592 | .01 | 0.02 | 0.004 | .001 | .09 | ||

| ELS × negative affect | 0.004 | 0.003 | .158 | .03 | 0.01 | 0.004 | .135 | .04 | ||

| ELS × effortful control | −0.002 | 0.003 | .532 | −.01 | 0.00 | 0.004 | .994 | .00 | ||

| Model 2b | .06 | .09 | ||||||||

| ELS | 0.02 | 0.004 | <.001 | .11 | 0.04 | 0.01 | <.001 | .18 | ||

| ELS × inhibit | 0.003 | 0.004 | .368 | .03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .165 | .07 | ||

| ELS × shift | 0.01 | 0.003 | .012 | .08 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .190 | −.04 | ||

| ELS × emotional control | −0.003 | 0.003 | .380 | −.03 | −0.001 | 0.01 | .784 | −.01 | ||

| ELS × working memory | −0.002 | 0.004 | .666 | −.02 | −0.00 | 0.01 | .955 | −.00 | ||

| ELS × plan/organize | 0.00 | 0.004 | .983 | .001 | −0.002 | 0.01 | .802 | −.01 | ||

| Model 2c | .08 | .11 | ||||||||

| ELS | 0.01 | 0.004 | <.001 | .09 | 0.04 | 0.01 | <.001 | .17 | ||

| ELS × surgency | 0.003 | 0.003 | .363 | .02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .009 | .07 | ||

| ELS × negative affect | 0.003 | 0.003 | .331 | .02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .119 | .05 | ||

| ELS × effortful control | −0.001 | 0.003 | .782 | −.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .997 | .00 | ||

| ELS × inhibit | 0.002 | 0.004 | .552 | .02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .255 | .05 | ||

| ELS × shift | 0.01 | 0.003 | .019 | .07 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .249 | −.04 | ||

| ELS × emotional control | −0.003 | 0.003 | .272 | −.03 | −0.003 | 0.01 | .545 | −.02 | ||

| ELS × working memory | −0.002 | 0.004 | .616 | −.02 | −0.00 | 0.01 | .994 | −.00 | ||

| ELS × plan/organize | 0.00 | 0.004 | .912 | .004 | −0.001 | 0.01 | .861 | −.01 | ||

Significant coefficients (p < .05) are displayed in bold. In Models 2a, 2b, and 2c, predictor and interaction terms were simultaneously included. Main effects of the predictors are reported in Table S4.

Abbreviation: ELS, early life stress.

Sensitivity analyses

When we applied stricter inclusion criteria in accordance with our preregistration (n = 1676), Models 1, 2a and 2b yielded the same conclusions as in our main analyses. There was one small difference in results for Model 2c, in which both temperament traits and executive functions were included as moderators: Only the interaction effect between ELS and shifting on internalizing problems remained significant (B = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p < .001, β = .16), while the interaction effect between ELS and surgency on externalizing problems was no longer significant (B = 0.01, SE = 0.00, p = .135, β = .04). Subsequently, in the sensitivity analysis with alternative inclusion criteria regarding missing values on the moderators, Model 2a (n = 1757) and Model 2b (n = 1877) yielded the same conclusions as in our main analyses. These results should be interpreted carefully because of power issues. Except for the aforementioned difference in moderation effects, the sensitivity analyses supported the robustness of our main findings.

DISCUSSION

This preregistered study aimed to identify the interplay between cumulative ELS and multiple child characteristics on child behavior problems. First, we calculated a comprehensive, latent cumulative ELS score from birth through age 6 years and assessed its associations with internalizing and externalizing problems at age 7 years. In line with previous studies (e.g., Evans et al., 2013; Northerner et al., 2016), we found evidence of associations between greater cumulative ELS and higher levels of teacher‐reported internalizing and externalizing problems. Our sensitivity analyses supported these findings among slightly different subsets of participants. This study expands on previous resilience research by including a comprehensive ELS measure with a large number of potential stressors over a 6‐year period. Moreover, these results provide additional support for considering a family's constellation of stressors in multiple life domains when examining pathways to behavior problems in school‐age children.

Second, we examined children's temperament and executive functions as potential protective factors moderating the associations between cumulative ELS and internalizing and externalizing problems. We found little evidence in favor of child temperament and executive functions as protective factors. Of the three temperament traits that were considered, we found weak evidence only for lower levels of surgency buffering the association between cumulative ELS and externalizing problems. These results align with the notion that children with lower levels of surgency may be at a decreased risk for developing externalizing problems when faced with stressors, as these children show less reward sensitivity, pleasure‐seeking, and impulsivity compared to children with higher surgency levels (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). However, a previous study did not find any interaction between cumulative ELS and surgency among toddlers from low‐income families (Northerner et al., 2016). The relevance and expression of temperament traits and coping strategies likely differ with age (Zimmer‐Gembeck & Skinner, 2016). It is possible that the contribution of temperamental surgency to resilience is larger in the current sample of school‐age children, since the regulation of activity levels, impulsivity, and lack of shyness become particularly relevant as toddlers enter childhood (Holmboe, 2016). At first glance, our result that children with lower surgency levels showed less externalizing behavior in the face of cumulative ELS might seem puzzling, given the potential conceptual overlap between surgency and externalizing behaviors. Yet, empirical findings suggest that content overlap in measurement cannot account for the relation between child temperament and externalizing behavior, indicating these are distinct constructs (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). The lack of support in our study for low negative affect and high effortful control as protective factors conflicts with some previous findings that these temperament traits promote resilience to stress (Masten, 2007). However, the few studies examining the interaction of cumulative ELS with negative affect and effortful control provided mixed results (Chang et al., 2012; Lengua, 2002; Northerner et al., 2016). Concerning the role of executive functions, our results suggest that better shifting capacities might buffer the impact of cumulative ELS on children's internalizing problems. Although this finding should be interpreted with caution due to low statistical power, this result fits and expands on cross‐sectional findings pointing to shifting/mental flexibility as a protective factor against adolescent internalizing problems (e.g., Davidovich et al., 2016). We found no support for other parent‐reported executive functions as protective factors, in contrast to earlier work suggesting that neuropsychologically assessed (general) executive functions are related to resilience (e.g., Horn et al., 2018; Masten et al., 2012; Taylor & Ruiz, 2019). However, the interplay between cumulative ELS and multiple executive function domains has not been previously examined.

Several explanations are possible for the limited evidence supporting child temperament and executive functions as protective factors in this study. First, most of the studies that did support temperament and executive functions as protective factors against cumulative ELS were limited by cross‐sectional designs (Lengua, 2002) or sole reliance on parent report (Northerner et al., 2016), possibly overestimating the strength of the associations. Yet, given that other methodologically rigorous studies have found evidence in favor of temperament and executive functions as factors contributing to resilience (Fritz et al., 2018), there may be alternative reasons we found only limited evidence in this study. That is, the ability to detect any moderation effect by protective factors on the association between ELS and behavior problems may have been reduced by the relatively low level of stress exposure in this community sample. While our cumulative ELS construct showed sufficient variability, few children experienced high levels of cumulative ELS. Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, there is a growing consensus in the field of resilience that protective factors may not be universal. Whether given factors are protective may depend on, amongst others, the developmental time period, the population under study, and the types of stress an individual experiences (Fritz et al., 2018). For example, although lower temperamental fearfulness and irritability have often been found to be protective in relation to behavior problems (e.g., Lengua, 2002; Rothbart & Bates, 2006), the results of Bush et al. (2010) suggest these child characteristics were vulnerabilities rather than protections against psychosocial problems in the context of neighborhood stress. The outcomes under study, the severity of stressors, and the presence of other protective factors may also impact the roles of some protective factors (Zolkoski & Bullock, 2012). However, more research is essential to generate more specific hypotheses about the differences and generalizability of protective factors across people and situations. Based on a recent systematic review (Fritz et al., 2018), only two amenable protective factors were significant contributors of child resilience in more than one study, which additionally highlights the crucial need for replication studies.

A unique aspect of this study was the examination of multiple temperament traits and multiple executive functions as potential protective factors in the context of cumulative ELS. Interestingly, when temperament and executive functions were simultaneously included as moderators in the models, both children's surgency and shifting capacities remained significant protective factors. This result emphasizes the notion that multiple individual characteristics affect children's adaptation in the face of ELS (Fritz et al., 2018). By examining both temperament traits and executive functions, we contributed to recent calls (Eisenberg & Zhou, 2016) to integrate two bodies of work that have traditionally been studied rather separately. Our findings showed that parent‐reported temperament traits and executive functions were only weakly to moderately associated, supporting other findings indicating these are related but distinct individual characteristics (e.g., Drechsler et al., 2018). We encourage future studies to attempt to better capture the unique and overlapping contributions of temperament and executive functions to resilience in childhood.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This study builds upon previous work on resilience in childhood by the use of a cumulative risk approach in a prospective, population‐based cohort, assessing the accumulation of ELS over 6 years. We employed a multi‐informant design to examine child emotional and behavioral problems in combination with multiple potential protective factors, namely child temperament and executive functions, to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the individual attributes that may promote children's resilience. The use of a relatively large sample with adequate power, the testing for measurement invariance across sex, and the performance of sensitivity analyses reinforced the robustness of our findings.

Nonetheless, the findings of this study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, owing to the large sample, we relied on a parental rating of children's executive functions using the BRIEF‐P. Although the BRIEF‐P provides important information about children's executive functions in daily, unstructured situations, aspects of executive functions at a fine‐grained functional level and performance‐based tasks are not assessed (Toplak et al., 2013). This should be taken into account when interpreting our findings concerning executive functions. Additionally, as both executive functions and temperament traits were assessed by parental report, our results may have been affected by shared method variance. Future studies using a multimethod strategy (e.g., combining questionnaires with neuropsychological assessments of executive functions or behavioral observations of temperament) may further reduce rater bias and the possible influence of parents’ social desirability or mood states on their ratings (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Furthermore, some of the stressors in our ELS construct were retrospectively reported by parents. Despite findings pointing to similar associations regardless of whether retrospective or prospective measures of childhood experiences were used (Reuben et al., 2016), we do not know if and to what extent parental responses in this study were affected by recall bias.

Second, our sample concerned a relatively homogenous community sample, recruited from only one urban setting in a single country. Although there was some degree of ethnic heterogeneity among the participating families, the majority consisted of middle‐class families of Dutch origin. The roles of temperament and executive functions in children's response to ELS are potentially different in families from other subpopulations. For instance, individual resources that promote resilience may differ depending on where families live (i.e., urban, suburban, rural) or on their cultural context (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005; Zolkoski & Bullock, 2012). It is also important to note that in the families that were excluded due to nonresponse, parents were younger, families had a lower income, and children were less often of Dutch ethnicity and were exposed to higher levels of ELS, compared to the families in our final sample. Hence, the absence of these families in our study may affect the generalizability of our findings. To generalize our results to other settings, it is critical that future studies investigate the effects of cumulative ELS and protective factors across families from different subpopulations.

Third, this study focused on temperament traits and executive functions as potential protective factors. Other individual child characteristics (e.g., self‐efficacy, self‐concept) as well as characteristics of the environment (e.g., family relationships) and community (e.g., school quality) may contribute to resilience in childhood (Fritz et al., 2018; Luthar, 2006). Although out of the scope of this study, the examination of potential protective factors at the internal child and external environmental level is crucial for a more nuanced understanding of why some children show more resilience than others in the face of cumulative ELS.

Fourth, despite our relatively large sample size, we still potentially had low statistical power for the moderation analyses with respect to internalizing outcomes because of the relatively weak main effects of the predictors reported in previous literature. Accordingly, the significant moderation effect by shifting could be the result of chance, considering the number of tests conducted, or be overestimated relative to the actual size in the population. Low power is an inherent concern in interaction analyses and has been described previously in the field of resilience (e.g., Luthar, 2006). Therefore, we encourage researchers to replicate the observed interaction effects in future studies that have the required power to detect these effects. In addition, alternative methodologies such as a “residuals approach” or person‐centered approaches could be considered in future studies. Since there is no “gold standard” for operationalizing and assessing resilience, it is valuable to conduct multi‐method resilience studies (e.g., Miller‐Lewis et al., 2013) to examine to what degree findings converge across methods.

CONCLUSION

In sum, this study adds to the literature on childhood resilience by assessing cumulative ELS, multiple protective factors, and emotional and behavioral outcomes among a prospective, population‐based cohort. We found support for associations between cumulative ELS from birth through age 6 years and internalizing and externalizing problems at age 7 years. However, we found limited evidence for the roles of child temperament and executive functions as protective factors against behavioral problems after ELS exposure. Our results highlight the need for additional research to further examine these and other possible protective factors in the context of cumulative ELS. A better understanding of children's responses to stress early in life could inform policy and prevention programs aimed at preventing the development of later behavior problems.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The general design of Generation R Study is made possible by financial support from the Erasmus Medical Center and the Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, and the Ministry of Youth and Families. This study was supported by the Erasmus Initiatives “Vital Cities and Citizens” of the Erasmus University Rotterdam (grant number 14000000.005). Stephen A. Metcalf was supported by an open research award from the Fulbright U.S. Student Program.

de Maat, D. A. , Schuurmans, I. K. , Jongerling, J. , Metcalf, S. A. , Lucassen, N. , Franken, I. H. A. , Prinzie, P. , & Jansen, P. W. (2022). Early life stress and behavior problems in early childhood: Investigating the contributions of child temperament and executive functions to resilience. Child Development, 93, e1–e16. 10.1111/cdev.13663

REFERENCES

- Achenbach, T. M. , & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school‐age forms and profiles. University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Agnafors, S. , Svedin, C. G. , Oreland, L. , Bladh, M. , Comasco, E. , & Sydsjö, G. (2017). A biopsychosocial approach to risk and resilience on behavior in children followed from birth to age 12. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 48, 584–596. 10.1007/s10578-016-0684-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard, K. , Egeland, B. , van Dulmen, M. H. , & Sroufe, L. A. (2005). When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 235–245. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzaba‐Poria, N. , Pike, A. , & Deater‐Deckard, K. (2004). Do risk factors for problem behaviour act in a cumulative manner? An examination of ethnic minority and majority children through an ecological perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 707–718. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis, M. A. , Hughes, K. , Ford, K. , Ramos Rodriguez, G. , Sethi, D. , & Passmore, J. (2019). Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 4, e517–e528. 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes, M. E. , Hasking, P. A. , & Martin, G. (2016). Adverse life experience and psychological distress in adolescence: Moderating and mediating effects of emotion regulation and rumination. Stress & Health, 32, 402–410. 10.1002/smi.2635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush, N. R. , Lengua, L. J. , & Colder, C. R. (2010). Temperament as a moderator of the relation between neighborhood and children's adjustment. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 351–361. 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. 10.4324/9780203807644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi, A. , Roberts, B. W. , & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484. 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil, C. A. M. , Lysenko, L. J. , Jaffee, S. R. , Pingault, J. B. , Smith, R. G. , Relton, C. L. , Woodward, G. , McArdle, W. , Mill, J. , & Barker, E. D. (2014). Environmental risk, oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) methylation and youth callous‐unemotional traits: A 13‐year longitudinal study. Molecular Psychiatry, 19, 1071–1077. 10.1038/mp.2014.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H. , Shelleby, E. C. , Cheong, J. , & Shaw, D. S. (2012). Cumulative risk, negative emotionality, and emotion regulation as predictors of social competence in the transition to school: A mediated moderation model. Social Development, 21, 780–800. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00648.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 464–504. 10.1080/10705510701301834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes Hidalgo, A. P. , Neumann, A. , Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M. J. , Jaddoe, V. W. V. , Rijlaarsdam, J. , Verhulst, F. C. , White, T. , van IJzendoorn, M. H. , & Tiemeier, H. (2018). Prenatal maternal stress and child IQ. Child Development, 91, 347–365. 10.1111/cdev.13177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich, S. , Collishaw, S. , Thapar, A. K. , Harold, G. , Thapar, A. , & Rice, F. (2016). Do better executive functions buffer the effect of current parental depression on adolescent depressive symptoms? Journal of Affective Disorders, 199, 54–64. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw, S. S. , & Mervielde, I. (2010). Temperament, personality and developmental psychopathology: A review based on the conceptual dimensions underlying childhood traits. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 41, 313–329. 10.1007/s10578-009-0171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsler, R. , Zulauf Logoz, M. , Walitza, S. , & Steinhausen, H. C. (2018). The relations between temperament, character, and executive functions in children with ADHD and clinical controls. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22, 764–775. 10.1177/1087054715583356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N. , Spinrad, T. L. , Fabes, R. A. , Reiser, M. , Cumberland, A. , Shepard, S. A. , Valiente, C. , Losoya, S. H. , Guthrie, I. K. , & Thompson, M. (2004). The relation of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency adjustment. Child Development, 75, 25–46. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N. , & Zhou, Q. (2016). Conceptions of executive function and regulation: When and to what degree do they overlap? In Griffin J. A., McCardle P., & Freund L. S. (Eds.), Executive function in preschool‐age children: Integrating measurement, neurodevelopment, and translational research (pp. 115–136). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14797-006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. W. , Li, D. , & Whipple, S. S. (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 139, 1342–1396. 10.1037/a0031808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus, S. , & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, H. L. , Schreier, A. , Zammit, S. , Maughan, B. , Munafò, M. R. , Lewis, G. , & Wolke, D. (2013). Pathways between childhood victimization and psychosis‐like symptoms in the ALSPAC birth cohort. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39, 1045–1055. 10.1093/schbul/sbs088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flouri, E. , & Kallis, C. (2007). Adverse life events and psychopathology and prosocial behavior in late adolescence: Testing the timing, specificity, accumulation, gradient, and moderation of contextual risk. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 1651–1659. 10.1097/chi.0b013e318156a81a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, J. , de Graaff, A. M. , Caisley, H. , Van Harmelen, A. L. , & Wilkinson, P. O. (2018). A systematic review of amenable resilience factors that moderate and/or mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and mental health in young people. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 1–17. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, G. A. , Espy, K. A. , & Isquith, P. K. (2003). Behavior rating inventory of executive function—Preschool version. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S. H. , Rouse, M. H. , Connell, A. M. , Broth, M. R. , Hall, C. M. , & Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta‐analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 1–27. 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, S. L. , & Dohrenwend, B. P. (2007). Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, sex, SES and age: A review of the research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40, 313–332. 10.1007/s10464-007-9134-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmboe, K. (2016). The construct of surgency. In Zeigler‐Hill V. & Shackelford T. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (pp. 1–6). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_2123-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horn, S. R. , Roos, L. E. , Beauchamp, K. G. , Flannery, J. E. , & Fisher, P. A. (2018). Polyvictimization and externalizing symptoms in foster care children: The moderating role of executive function. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 19, 307–324. 10.1080/15299732.2018.1441353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman, M. N. , Kruithof, C. J. , van Duijn, C. M. , Duijts, L. , Franco, O. H. , van IJzendoorn, M. H. , de Jongste, J. C. , Klaver, C. C. W. , van der Lugt, A. , Mackenbach, J. P. , Moll, H. A. , Peeters, R. P. , Raat, H. , Rings, E. H. H. M. , Rivadeneira, F. , van der Schroeff, M. P. , Steegers, E. A. P. , Tiemeier, H. , Uitterlinden, A. G. , … Jaddoe, V. W. V. (2016). The generation R study: Design and cohort update 2017. European Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 1243–1264. 10.1007/s10654-016-0224-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafavor, T. (2018). Predictors of academic success in 9‐ to 11‐year‐old homeless children: The role of executive function, social competence, and emotional control. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38, 1236–1264. 10.1177/0272431616678989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua, L. J. (2002). The contribution of emotionality and self‐regulation to the understanding of children’s response to multiple risk. Child Development, 73, 144–161. 10.1111/1467-8624.00397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua, L. J. , Bush, N. R. , Long, A. C. , Kovacs, E. A. , & Trancik, A. M. (2008). Effortful control as a moderator of the relation between contextual risk factors and growth in adjustment problems. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 509–528. 10.1017/S0954579408000254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua, L. J. , & Wachs, T. D. (2012). Temperament and risk: Resilient and vulnerable responses to adversity. In Zentner M. & Shiner R. L. (Eds.), Handbook of temperament (pp. 519–540). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In Cicchetti D. & Cohen D. J. (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (pp. 740–795). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar, S. S. , & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 857–885. 10.1017/s0954579400004156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. (2007). Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Developmental Psychopathology, 19, 921–930. 10.1017/S0954579407000442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. , Herbers, J. E. , Desjardins, C. D. , Cutuli, J. J. , McCormick, C. M. , Sapienza, J. K. , Long, J. D. , & Zelazo, P. D. (2012). Executive function skills and school success in young children experiencing homelessness. Educational Researcher, 41, 375–384. 10.3102/0013189X12459883 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, K. A. , Hilt, L. M. , & Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. (2007). Racial/ethnic differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 801–816. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller‐Lewis, L. R. , Searle, A. K. , Sawyer, M. G. , Baghurst, P. A. , & Hedley, D. (2013). Resource factors for mental health resilience in early childhood: An analysis with multiple methodologies. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 7, 1–23. 10.1186/1753-2000-7-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry, R. S. , Benner, A. D. , Biesanz, J. , Clark, S. , & Howes, C. (2010). Family and social risk, and parental investments during the early childhood years as predictors of low‐income children’s school readiness outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 432–449. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Northerner, L. M. , Trentacosta, C. J. , & McLear, C. M. (2016). Negative affectivity moderates associations between cumulative risk and at‐risk toddlers’ behavior problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 691–699. 10.1007/s10826-015-0248-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradović, J. (2010). Effortful control and adaptive functioning of homeless children: Variable‐focused and person‐focused analyses. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 109–117. 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradović, J. (2016). Physiological responsivity and executive functions: Implications for adaptation and resilience in early childhood. Child Development Perspectives, 10, 65–70. 10.1111/cdep.12164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M. , MacKenzie, S. B. , & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, S. P. , Ellis, L. K. , & Rothbart, M. K. (2001). The structure of temperament from infancy through adolescence. In Eliasz A. & Angleitner A. (Eds.), Advances in research on temperament (pp. 165–182). Pabst Science. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, S. P. , & Rothbart, M. K. (2006). Development of short and very short forms of the Children's Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 87, 102–112. 10.1207/s15327752jpa8701_09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben, A. , Moffitt, T. E. , Caspi, A. , Belsky, D. W. , Harrington, H. , Schroeder, F. , Hogan, S. , Ramrakha, S. , Poulton, R. , & Danese, A. (2016). Lest we forget: Comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57, 1103–1112. 10.1111/jcpp.12621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijlaarsdam, J. , Pappa, I. , Walton, E. , Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M. J. , Mileva‐Seitz, V. R. , Rippe, R. C. A. , Roza, S. J. , Jaddoe, V. W. V. , Verhulst, F. C. , Felix, J. F. , Cecil, C. A. M. , Relton, C. L. , Gaunt, T. R. , McArdle, W. , Mill, J. , Barker, E. D. , Tiemeier, H. , & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2016). An epigenome‐wide association meta‐analysis of prenatal maternal stress in neonates: A model approach for replication. Epigenetics, 11, 140–149. 10.1080/15592294.2016.1145329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02 [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart, M. K. , Ahadi, S. A. , Hershey, K. L. , & Fisher, P. (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children's Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development, 72, 1394–1408. 10.1111/1467-8624.00355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart, M. K. , & Bates, J. E. (2006). Temperament. In Eisenberg N., Damon W., & Lerner R. M. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (Vol. 3, 6th ed., pp. 99–166). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. (1999). Resilience concepts and findings: Implications for family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy, 21, 119–144. 10.1111/1467-6427.00108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff, A. J. , & Rosenblum, K. L. (2006). Psychosocial constraints on the development of resilience. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 116–124. 10.1196/annals.1376.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheinkopf, S. J. , Lagasse, L. L. , Lester, B. M. , Liu, J. , Seifer, R. , Bauer, C. R. , Shankaran, S. , Bada, H. , & Das, A. (2007). Vagal tone as a resilience factor in children with prenatal cocaine exposure. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 649–673. 10.1017/S0954579407000338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsohn, U. (2015). No‐way interactions. The Winnower, 2, 1–3. 10.15200/winn.142559.90552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slagt, M. , Dubas, J. S. , Deković, M. , & van Aken, M. A. G. (2016). Differences in sensitivity to parenting depending on child temperament: A meta‐analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 142, 1068–1110. 10.1037/bul0000061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Netherlands . (2018). Jaarrapport integratie [Annual report integration]. CBS. https://www.cbs.nl/nl‐nl/publicatie/2018/47/jaarrapport‐integratie‐2018 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Z. E. , & Ruiz, Y. (2019). Executive function, dispositional resilience, and cognitive engagement in Latinx children of migrant farmworkers. Children and Youth Services Review, 100, 57–63. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.02.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toplak, M. E. , West, R. F. , & Stanovich, K. E. (2013). Practitioner review: Do performance‐based measures and ratings of executive function assess the same construct? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 5, 131–143. 10.1111/jcpp.12001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren, S. , & Groothuis‐Oudshoorn, K. (2010). mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–67. 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wachs, T. D. (1992). The nature of nurture. Sage. 10.4135/9781483326078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer‐Gembeck, M. J. , & Skinner, E. A. (2016). Developmental psychopathology: Risk, resilience, and intervention. In Cichetti D. (Ed.), The development of coping: Implications for psychopathology and resilience (pp. 485–545). John Wiley & Sons Inc. 10.1002/9781119125556.devpsy410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]