Abstract

Aims

Sacubitril/valsartan improves morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Whether initiation of sacubitril/valsartan limits the use and dosing of other elements of guideline‐directed medical therapy for HFrEF is unknown. We examined the effects of sacubitril/valsartan, compared with enalapril, on β‐blocker and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) use and dosing in a large randomized clinical trial.

Methods and results

Patients with full data on medication use were included. We examined β‐blocker and MRA use in patients randomized to sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril through 12‐month follow‐up. New initiations and discontinuations of β‐blocker and MRA were compared between treatment groups. Overall, 8398 (99.9%) had full medication and dose data at baseline. Baseline use of β‐blocker and MRA at any dose was 87% and 56%, respectively. Mean doses of β‐blocker and MRA were similar between treatment groups at baseline and at 6‐month and 12‐month follow‐up. New initiations through 12‐month follow‐up were infrequent and similar in the sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril groups for β‐blockers [37 (9.0%) vs. 42 (10.2%), P = 0.56] and MRA [127 (7.6%) vs. 143 (9.2%), P = 0.10]. Among patients on MRA therapy at baseline, there were fewer MRA discontinuations in patients on sacubitril/valsartan as compared with enalapril at 12 months [125 (6.2%) vs. 187 (9.0%), P = 0.001]. Discontinuations of β‐blockers were not significantly different between groups in follow‐up (2.2% vs. 2.6%, P = 0.26).

Conclusions

Initiation of sacubitril/valsartan, even when titrated to target dose, did not appear to lead to greater discontinuation or dose down‐titration of other key guideline‐directed medical therapies, and was associated with fewer discontinuations of MRA. Use of sacubitril/valsartan (when compared with enalapril) may promote sustained MRA use in follow‐up.

Keywords: β‐blockers, Guideline‐directed medical therapy, Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, Sacubitril/valsartan

Introduction

Despite recommendations supporting the use of guideline‐directed medical therapy (GDMT) for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), 1 , 2 registry data show rates of comprehensive pharmacotherapy for HFrEF care are low in usual care. 3 In the PARADIGM‐HF (Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) trial, the angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan reduced cardiovascular death or heart failure (HF) hospitalization compared with enalapril among patients with chronic HFrEF. 4 As a result, major guidelines recommend switching to sacubitril/valsartan in eligible patients. 1 , 2 The clinical benefits of sacubitril/valsartan were consistently observed irrespective of baseline medical therapy 6 and the effects of randomization on mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) use patterns and incident hyperkalaemia have been described. 7 Patients in PARADIGM‐HF randomized to sacubitril/valsartan had greater blood pressure reductions compared with enalapril. 5 Whether switching to sacubitril/valsartan (and its attendant haemodynamic and clinical effects) requires early alteration in initiation, dosing, and maintenance of foundational GDMT is not known; these data may inform optimal sequencing pathways to implement contemporary multi‐drug regimens in HFrEF. Therefore, we investigated the effects of randomization to sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril on early changes in the use and dosing of β‐blockers and MRA over time in PARADIGM‐HF.

Methods

The design and results of PARADIGM‐HF have been previously reported. 4 , 8 In brief, PARADIGM‐HF was a global, double‐blind, active‐controlled trial that enrolled patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–IV HFrEF (ejection fraction ≤40%). Patients underwent sequential active run‐in phases with enalapril up‐titrated to 10 mg twice daily followed by sacubitril/valsartan up‐titrated to 97/103 mg twice daily to assess tolerability of both study drugs at target doses. Patients completing run‐in were randomized to sacubitril/valsartan 97/103 mg twice daily or enalapril 10 mg twice daily and were followed for a median of 27 months. Use and dose of evidence‐based β‐blockers (carvedilol, extended‐release metoprolol, and bisoprolol) and MRAs (spironolactone and eplerenone) were collected at randomization and at 6 and 12 months post‐randomization. The effects of randomization status on loop diuretic use in follow‐up have been previously reported and therefore were not assessed in this analysis. 9

Statistical analysis

As the objective of this analysis was to determine the association between sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril on use patterns of β‐blockers and MRA, all analyses were performed in the as‐treated cohort (based on treatment received). Patients with full data on medication use/dose at baseline and in follow‐up were included. Follow‐up was limited to 12 months given high missingness further from randomization. The proportion of patients on therapy (at any dose, ≥50% target dose, and ≥100% target dose) was assessed in both treatment arms (sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril) at baseline, 6 months and 12 months. Target doses were based on the 2016 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) HF guidelines. 2 Target doses for β‐blockers were bisoprolol 10 mg daily, carvedilol 25 mg twice daily, and extended‐release metoprolol 200 mg once daily. Given variable definitions of target dosing for MRA and lack of consistant demonstrated dose response on clinical outcomes, dosing was summarized for β‐blocker only.

Among patients not receiving β‐blocker and MRA at baseline, new initiations were compared by treatment arm in follow‐up. Similarly, among patients receiving β‐blocker and MRA at baseline, discontinuations were compared during follow‐up by treatment arm. New initiations and discontinuations were assessed among patients alive and with available data at each follow‐up time point. A P‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Overall, of 8399 patients validly randomized in PARADIGM‐HF, 8398 (99.9%) had full medication/dose data for β‐blocker and MRA at baseline. Full medication/dose data were available in 7341 (87.4%) and 7340 (87.4%) patients for β‐blocker and MRA, respectively at 12 months. Baseline characteristics by randomization assignment according to baseline β‐blocker and MRA use have been previously reported. 6 , 7 Of note, age, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, and kidney function were well balanced between treatment arms.

β‐blocker use during 12‐month follow‐up

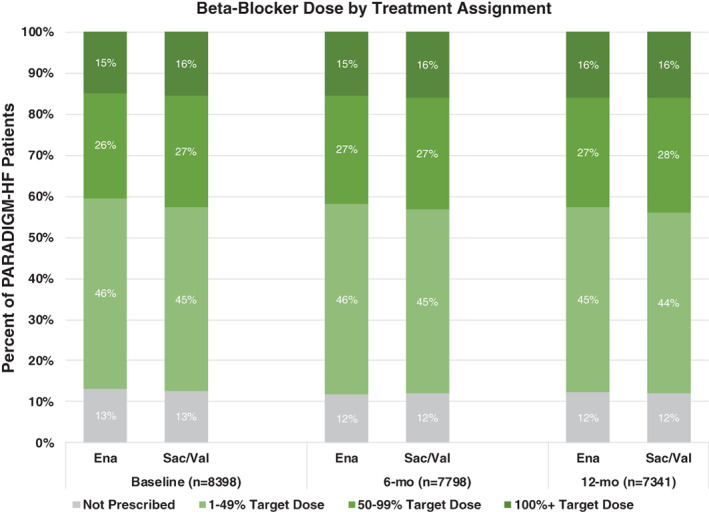

β‐blocker use was similar between groups at baseline (sacubitril/valsartan: 87.4% vs. enalapril: 86.8%, P = 0.40), and at 6‐month (88.0% vs. 88.2%, P = 0.88), and 12‐month follow‐up (87.9% vs. 87.6%, P = 0.63). As previously reported, of all patients on β‐blockers at baseline, 47.7% were on ≥50% target dose and 17.4% were on ≥100% target dose. 6 Mean β‐blocker doses were not significantly different between those on sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril at any time point (Table 1 ). Patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan had higher rates of ≥50% target β‐blocker dose at baseline (42.7% vs. 40.4%, P = 0.036), though there were no significant differences at 6 months (43.2% vs. 41.9%, P = 0.24) and 12 months (43.8% vs. 42.6%, P = 0.24) post‐randomization (Figure 1 ).

Table 1.

Doses of evidence based therapies over time by treatment allocation

| ESC target total daily dose (mg) | Baseline | 6‐month follow‐up | 12‐month follow‐up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enalapril | Sac/Val | P‐value | Enalapril | Sac/Val | P‐value | Enalapril | Sac/Val | P‐value | ||

| β‐blocker | ||||||||||

| Carvedilol | 50 | 22 ± 18 (n = 1658) | 22 ± 18 (n = 1630) | 0.39 | 22 ± 18 (n = 1565) | 22 ± 18 (n = 1554) | 0.84 | 23 ± 19 (n = 1468) | 23 ± 18 (n = 1473) | 0.69 |

| Metoprolol succinate | 200 | 74 ± 54 (n = 892) | 79 ± 60 (n = 922) | 0.06 | 76 ± 54 (n = 862) | 78 ± 59 (n = 873) | 0.58 | 77 ± 57 (n = 816) | 78 ± 59 (n = 832) | 0.60 |

| Bisoprolol | 10 | 6 ± 6 (n = 1111) | 5 ± 3 (n = 1114) | 0.39 | 6 ± 7 (n = 1070) | 5 ± 3 (1087) | 0.40 | 6 ± 7 (n = 1006) | 5 ± 3 (n = 1047) | 0.31 |

| MRA | ||||||||||

| Spironolactone | – | 29 ± 17 (n = 2206) | 30 ± 17 (n = 2101) | 0.42 | 29 ± 16 (n = 2075) | 30 ± 17 (n = 1991) | 0.41 | 29 ± 16 (n = 1935) | 30 ± 17 (n = 1911) | 0.79 |

| Eplerenone | – | 28 ± 12 (n = 173) | 28 ± 10 (n = 158) | 0.98 | 29 ± 13 (n = 167) | 29 ± 10 (n = 175) | 0.97 | 29 ± 14 (n = 176) | 28 ± 11 (n = 173) | 0.39 |

Based on as‐treated cohort.

ESC, European Society of Cardiology; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; Sac/Val, sacubitril/valsartan.

Figure 1.

β‐blocker dosing categorized into patients not on therapy, and patients on 1–49%, 50–99%, and 100%+ of target dose by treatment assignment with enalapril (Ena) vs. sacubitril/valsartan (Sac/Val) at baseline, and 6‐ and 12‐month follow‐up. 100%+ reflects dosing that equals or exceeds target doses recommended in clinical practice guidelines.

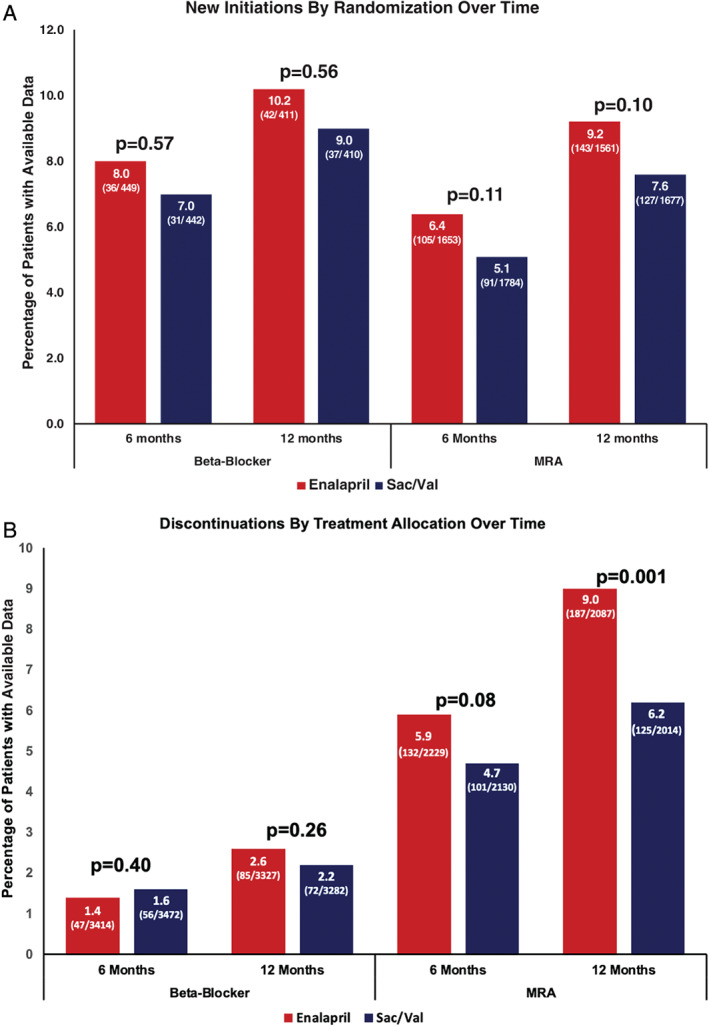

Among patients not on β‐blocker, new initiations were infrequent and similar based on treatment with sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril at 6‐month [31 (7.0%) vs. 36 (8.0%), P = 0.57] and 12‐month follow‐up [37 (9.0%) vs. 42 (10.2%), P = 0.56] (Figure 2A ). Among patients on β‐blocker, discontinuations occurred at similar rates at 6 months [56 (1.6%) vs. 47 (1.4%), P = 0.40] and 12 months [72 (2.2%) vs. 85 (2.6%), P = 0.26] (Figure 2B ).

Figure 2.

New initiations (A) and discontinuations (B) of β‐blocker and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) at 6 and 12 months post‐randomization. Sac/Val, sacubitril/valsartan. Note: Percentage for new initiations are calculated as the proportion of patients newly initiating therapy among all patients not previously on this particular therapy. Percentages for discontinuations are calculated as the proportion of patients discontinuing therapy among all patients previously on this particular therapy.

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist use during 12‐month follow‐up

Patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan had lower MRA use as compared with those receiving enalapril at baseline (53.9% vs. 56.4%, P = 0.02) and at 6 months post‐randomization (53.4% vs. 56.9%, P = 0.05). At 12 months post‐randomization, there were no significant differences in MRA use by treatment arm (54.6% vs. 56.0%, P = 0.23). Mean doses of spironolactone and eplerenone were similar between groups at all time points (Table 1 ).

Among patients not on MRA, new initiations did not significantly differ by treatment with sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril at 6 months [91 (5.1%) vs. 105 (6.4%), P = 0.11] and 12 months [127 (7.6%) vs. 143 (9.2%), P = 0.10] (Figure 2A ). However, in patients on MRA, there were fewer discontinuations of MRA in patients assigned to sacubitril/valsartan as compared to enalapril at 6 months post‐randomization [101 (4.7%) vs. 132 (5.9%), P = 0.08], reaching significance at 12 months post‐randomization [125 (6.2%) vs. 187 (9.0%), P = 0.001] (Figure 2B ).

Discussion

Given multiple disease‐modifying benefits in patients with HFrEF, 10 achieving comprehensive combination regimens is a high treatment priority. However, many of these therapies influence haemodynamics, electrolytes, and kidney function; upfront initiation of certain GDMT components may influence the subsequent tolerability of other core elements. Integration of new GDMT without compromising other foundational therapies is a major therapeutic goal in HFrEF management, and these data from PARADIGM‐HF provide some reassurance that this can be practically achieved when initiating sacubitril/valsartan. This tolerability should be interpreted within the context of the PARADIGM‐HF study design, in which enrolled subjects were optimized on these classes of therapies and tolerated sequential open‐label run‐in phases (including with full‐dose sacubitril/valsartan) prior to enrolment.

Patients on sacubitril/valsartan had lower discontinuation rates of MRA in follow‐up. This finding suggests that transitioning to sacubitril/valsartan may facilitate sustained MRA use. Favourable effects on kidney function 11 may promote sustained MRA therapy. Previous reports have also found lower rates of incident hyperkalaemia with sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril, which may also contribute to lower MRA discontinuation rates. 7 Similar findings of lower treatment‐attendant hyperkalaemia have been observed with the sodium–glucose co‐transporter 2 inhibitors, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin 12 , 13 As sacubitril/valsartan is well‐recognized to promote clinical stability, 14 it is plausible that lower frequency of MRA discontinuation was related to lower rates of HF hospitalization and therapeutic destabilization in the sacubitril/valsartan‐treated patients. 15 As therapeutic changes to GDMT may be more likely to occur during hospitalization, this may also in part account for the reduction in MRA discontinuations in those on sacubitril/valsartan. We observed a non‐significant trend towards fewer MRA new initiations among sacubitril/valsartan‐treated participants by 12 months compared with enalapril‐treated participants. Similar patterns of MRA use in follow‐up have been observed in contemporary evaluations with the sodium–glucose co‐transporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin. 13 These consistent patterns reinforce that clinicians may be less like to modify GDMT among patients who are considered clinically stable. Contemporary consensus statements now recommend early ARNI initiation among eligible patients, in addition to other core GDMT elements. 16 These data support that sacubitril/valsartan does not appear to lead to discontinuation of other foundational GDMT.

Limitations of post‐hoc investigation should be acknowledged. We did not have information regarding prior medication trials, including previous attempts at initiation of β‐blockers and MRA. While patients were well‐balanced with respect to most baseline characteristics, differences that emerged over time may have influenced initiations or discontinuations that were not fully captured within this analysis. Baseline medication use differs slightly from those reported in the original PARADIGM‐HF trial 4 as this analysis focused only on evidence‐based β‐blocker and MRA recommended in current HFrEF guidelines as opposed to any drug within the respective class. 1 , 2 Target doses included in this study (derived from ESC clinical practice guidelines) may differ from those included in other international guidelines or those tested in pivotal randomized clinical trials. Sequential run‐in phases may have selected for patients who had demonstrated ability to tolerate sacubitril/valsartan in addition to background therapy. Unmeasured confounding leading to differential tolerability to MRA in each arm may also in part explain these findings. Finally, reasons for treatment changes in background therapies were not prospectively collected from site investigators.

Conclusion

Multi‐drug regimens in HFrEF require simultaneous balancing of multiple factors (haemodynamics, kidney function, electrolytes, affordability, and adherence). In PARADIGM‐HF, initiation of sacubitril/valsartan did not influence use and dosing of β‐blocker and was associated with less discontinuations of background MRA therapy, compared with enalapril. These data are reassuring that in a well‐monitored clinical trial cohort, initiation of sacubitril/valsartan leads to minimal disruption of other background HFrEF therapy and may promote sustained MRA use. Further data are needed from usual care settings to understand the practicalities of various combinations and sequencing of contemporary GDMT in HFrEF.

Funding

The PARADIGM‐HF trial was funded by Novartis AG.

Conflict of interest: A.S.B. has received consulting/speaking fees from Sanofi Pasteur, Verve Therapeutics, and Clarivate and is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) T32 postdoctoral training grant T32HL094301. M.V. has received research grants from and/or serves on advisory boards for American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Relypsa, and Roche Diagnostics, has participated in speaking engagements supported by Roche Diagnostics and Novartis, and participates in clinical endpoint committees for studies sponsored by Galmed and Novartis. B.L.C. received consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, AOBiome, Novartis, Myokardia, and Corvia. M.P. has received personal fees from Akcea Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Actavis, AbbVie, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardiorentis, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Relypsa, Sanofi, Synthetic Biologics, and Theravance. A.S.D. has received grants from Abbott, Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Novartis; and has been a consultant for Abbott, Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Biofourmis, Boston Scientific, Cytokinetics, DalCor Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, and Relypsa. J.L.R. has received personal fees from Novartis, Abbott, Bayer, Myokardia Aventis and AstraZeneca. V.C.S. and M.P.L. are employees of Novartis. M.R.Z. has received research funding from Novartis; and has been a consultant for Novartis, Abbott, Boston Scientific, CVRx, EBR, Endotronics, Ironwood, Merck, Medtronic, and MyoKardia V Wave.

K.S. has served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Pfizer. Dr. Anand has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, ARCA, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, LivaNova, and Zensun. O.V. reports grants and non‐financial support from Sanofi‐Pasteur, personal fees from Novartis, and grants from AstraZeneca and Bayer. J.J.V.M. has received consulting payments through Glasgow University from Bayer, Cardiorentis, Amgen, Theracos, AbbVie, DalCor Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Merck, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Vifor‐Fresenius, Kidney Research UK, Novartis, and Theraco. S.D.S. has received research grants from Actelion, Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bellerophon, Bayer, BMS, Celladon, Cytokinetics, Eidos, Gilead, GSK, Ionis, Lilly, Mesoblast, MyoKardia, NIH/NHLBI, Neurotronik, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Respicardia, Sanofi Pasteur, Theracos, and has consulted for Abbott, Action, Akros, Alnylam, Amgen, Arena, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boeringer‐Ingelheim, BMS, Cardior, Cardurion, Corvia, Cytokinetics, Daiichi‐Sankyo, GSK, Lilly, Merck, Myokardia, Novartis, Roche, Theracos, Quantum Genomics, Cardurion, Janssen, Cardiac Dimensions, Tenaya, Sanofi‐Pasteur, Dinaqor, Tremeau, CellProThera, Moderna, American Regent, Sarepta.

References

- 1. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride P, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW, Westlake C. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College Of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2017;136:e137–e161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, DeVore AD, Sharma PP, Duffy CI, Hill CL, McCague K, Mi X, Patterson JH, Spertus JA, Thomas L, Williams FB, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC. Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the CHAMP‐HF registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:351–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR; PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Committees . Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vardeny O, Claggett B, Kachadourian J, Pearson SM, Desai AS, Packer M, Rouleau J, Zile MR, Swedberg K, Lefkowitz M, Shi V, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes associated with hypotensive episodes among heart failure patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan or enalapril: the PARADIGM‐HF trial (Prospective Comparison of Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitor with Angiotensin‐Converting Enzyme Inhibitor to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure). Circ Heart Fail 2018;11:e004745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Okumura N, Jhund PS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Solomon SD, Packer M, McMurray JJ; PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Committees . Effects of sacubitril/valsartan in the PARADIGM‐HF trial (Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) according to background therapy. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9:e003212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Desai AS, Vardeny O, Claggett B, McMurray JJV, Packer M, Swedberg K, Rouleau JL, Zile MR, Lefkowitz M, Shi V, Solomon SD. Reduced risk of hyperkalemia during treatment of heart failure with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists by use of sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril: a secondary analysis of the PARADIGM‐HF trial. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau J, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR; PARADIGM‐HF Committees and Investigators . Dual angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition as an alternative to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: rationale for and design of the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM‐HF). Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:1062–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vardeny O, Claggett B, Kachadourian J, Desai AS, Packer M, Rouleau J, Zile MR, Swedberg K, Lefkowitz M, Shi V, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Reduced loop diuretic use in patients taking sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril: the PARADIGM‐HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Jhund PS, Cunningham JW, Pedro Ferreira J, Zannad F, Packer M, Fonarow GC, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Estimating lifetime benefits of comprehensive disease‐modifying pharmacological therapies in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a comparative analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2020;396:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Damman K, Gori M, Claggett B, Jhund PS, Senni M, Lefkowitz MP, Prescott MF, Shi VC, Rouleau JL, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Packer M, Desai AS, Solomon SD, McMurray JJV. Renal effects and associated outcomes during angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shen L, Kristensen SL, Bengtsson O, Böhm M, de Boer RA, Docherty KF, Inzucchi SE, Katova T, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Langkilde AM, Lindholm D, Martinez MFA, O'Meara E, Nicolau JC, Petrie MC, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Schou M, Sjöstrand M, Solomon SD, Jhund PS, McMurray JJV. Dapagliflozin in HFrEF patients treated with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists: an analysis of DAPA‐HF. JACC Heart Fail 2021;9:254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferreira JP, Zannad F, Pocock SJ, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Steubl D, Schueler E, Packer M. Interplay of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and empagliflozin in heart failure: EMPEROR‐Reduced. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:1397–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Packer M, McMurray JJV, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile M, Andersen K, Arango JL, Arnold JM, Bělohlávek J, Böhm M, Boytsov S, Burgess LJ, Cabrera W, Calvo C, Chen CH, Dukat A, Duarte YC, Erglis A, Fu M, Gomez E, Gonzàlez‐Medina A, Hagège AA, Huang J, Katova T, Kiatchoosakun S, Kim KS, Kozan Ö, Llamas EB, Martinez F, Merkely B, Mendoza I, Mosterd A, Negrusz‐Kawecka M, Peuhkurinen K, Ramires FJ, Refsgaard J, Rosenthal A, Senni M, Sibulo AS Jr, Silva‐Cardoso J, Squire IB, Starling RC, Teerlink JR, Vanhaecke J, Vinereanu D, Wong RC; PARADIGM‐HF Investigators and Coordinators . Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation 2015;131:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Srivastava PK, DeVore AD, Hellkamp AS, Thomas L, Albert NM, Butler J, Patterson JH, Spertus JA, Williams FB, Duffy CI, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC. Heart failure hospitalization and guideline‐directed prescribing patterns among heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients. JACC Heart Fail 2021;9:28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maddox TM, Januzzi JL Jr, Allen LA, Breathett K, Butler J, Davis LL, Fonarow GC, Ibrahim NE, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, Motiwala SR, Oliveros E, Patterson JH , Walsh MN, Wasserman A, Yancy CW, Youmans QR. 2021 Update to the 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for optimization of heart failure treatment: answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:772–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]