Abstract

Aim

To describe fathers’ lived experiences of caring for their preterm infant at the neonatal unit and in hospital‐based neonatal home care after the introduction of an individualised parental support programme.

Method

Seven fathers from a larger study were included due to their rich narrative interviews about the phenomenon under study. The interviews took place after discharge from neonatal home care. The theoretical perspective was descriptive phenomenology. Giorgi’s outlines for phenomenological analysis were used. Findings The general structure of the phenomenon was described by the following four themes: The partner was constantly present in the fathers’ minds; The fathers’ were occupied by worries and concerns; The fathers felt that they were an active partner to the professionals and Getting the opportunity to take responsibility. The fathers were satisfied with the support and treatment during their infant’s hospitalisation. However, there were times when they felt excluded and not fully responsible for their infant. The fathers prioritised the mother, thus ignoring their own needs. Furthermore, they worried about their infant’s health and the alteration of their parental role. Neonatal home care was experienced as a possibility to regain control over family life.

Conclusion

The general structure of fathers’ experiences highlights the importance of professionals becoming more responsive to fathers’ needs and to tailoring support to fathers by focusing on their individual experiences and needs.

Keywords: preterm infant, fathers, experiences, NICU, hospital‐based neonatal home care, interviews, phenomenology

Introduction

Previous studies on parental experiences of having a preterm infant admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) mainly focused on the mother’s experiences and needs (1, 2) However, over the last decade fathers’ experiences have received more attention (3, 4). Fathers’ experiences are complex, thus healthcare professionals’ needs to consider the unique perspective of fathers in neonatal care (5).

The psychological strain and emotional stress experienced by parents of preterm infants might affect their transition to parenthood (6, 7). The altered parental role, combined with concern for the infant’s survival and future development are factors that parents of preterm infants describe as distressing and difficult to handle (6, 8, 9). An important aspect of neonatal care is that fathers seem to view their own needs as less important compared to the needs of their partner and infant (10, 11). A recent study by Hagen, Iversen and Svindseth (2016) also indicates that parents’ coping experiences differ, as fathers tried hard to be a supportive partner and focused on the mother’s well‐being, while the mothers focused on the infant’s needs. Furthermore, the fathers were less open to receiving support from staff compared with the mothers (12). Prioritising their partner may negatively affect fathers’ involvement in their infant’s care (10).

Parents to preterm infants are also at increased risk of post‐traumatic stress disorders, indicating that the initial hospitalisation and the period after discharge are stressful for both mothers and fathers (6, 13). Post‐traumatic stress disorders in parents can lead to difficulties in interaction with the infant and affirmative attachment (13, 14).

The principles of family‐centred care (FCC) (15) have increasingly been implemented in NICUs. Practising FCC is shown to reduce parental stress (16). As part of a FCC approach different supportive nursing interventions such as Kangaroo mother care (17), individualised developmental care (18) and various parent education programmes (19) have been implemented in NICUs aimed at reducing parental stress and supporting parents in their parental role. In a recent review (9), as well as in other studies, such support seems to reduce parental stress among both mothers and fathers of preterm infants (19, 20). However, other studies have failed to demonstrate such positive effects (21, 22). Although these supportive interventions are usually given to both parents, most parental support activities are based on data focusing on mothers’ experiences and needs (3).

Hospital‐based neonatal home care (HNHC) is a relatively new form of care that allows parents to care for their infant at home with support from NICU staff towards the end of the care period (23, 24). Earlier discharge from the NICU has been shown to activate the families’ own resources (25) and to have a positive effect on the parents’ wellbeing (26). Additionally, the cost of HNHC tends to be lower compared to standard hospital care (24). However, there is a lack of knowledge about how parents, especially fathers, experience neonatal care and the HNHC period. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe fathers’ lived experiences of caring for their preterm infant at the NICU and in HNHC after the introduction of an individualised parental support programme.

Method

The theoretical perspective of this study is founded in Edmund Husserl’s descriptive phenomenology (Husserl, 2000; original publication 1913). Husserl aims to describe the meaning of people’s life world as it manifests itself in their speech or writing. The meaning is closely linked to the description of the content of an individual’s consciousness. The focus is on the individual’s narrative of the experienced phenomenon and the analysis aims to describe the most invariant structure of the phenomenon under study (27). Giorgi developed the descriptive phenomenological method and outlined the empirical phenomenological analysis for use in health sciences (27, 28, 29).

The researcher adopts a critical attitude towards their own descriptions of the phenomenon in order to ensure that they do not go beyond the data collected. The analysis applies the phenomenological reduction technique to the spontaneous meaning units, which exclude unimportant content in the narratives of the subjects, who in this study are fathers of preterm infants, on order to clarify the phenomenon (27, 28). The basic aim of the descriptions is to obtain the general structure of the essence of the studied phenomenon

The chosen scientific perspective is caring sciences and in particular FCC. According to the Institute for patient and family‐centred care (15), FCC is ‘an approach to the planning, delivery and evaluation of health care that is grounded in mutually beneficial partnerships among health care providers, patients and families’. Who constitutes the ‘family’ is defined by the family members themselves, who also determine the level at which they will participate in the care and decision‐making. For the professionals, this implies a shift of power towards the patient/family.

Setting

The study was conducted in a Swedish level IIb NICU with 10‐12 beds and approximately 200 admissions per year. The NICU offers short‐term mechanical ventilation for infants over 28 weeks of gestation. The care of infants with a gestational age of less than 28 weeks is centralised. The unit had a family‐centred approach with unlimited access for parents and siblings. In the intensive care room, the parents could not spend the night in a bed next to the infant, but instead had their own single family‐room (SFR) at the unit where they could rest and spend time with their family. When the infants were stable, they could be cared for in the SFR where the parents were the primary caregivers.

HNHC was introduced at the unit in 2009 as a complement to in‐hospital care. During the time in HNHC, the infant was still registered in the NICU. Inclusion criteria for HNHC are presented in Table 1. The infants transferred to HNHC often needed tube feeding and had not achieved the weight considered adequate for discharge. Oxygen supplement treatment including monitoring of oxygen saturation and phototherapy was available in HNHC. The neonatal home care team consisted of three experienced neonatal nurses with a specialist education in paediatric nursing, one neonatologist, a social worker and when necessary a dietician. The nurses worked at both the neonatal unit and in HNHC and delivered care to infants and parents at home based on each family’s individual needs. During their weekly rounds, all team members discussed the infants in HNHC and the time for discharge was decided based on the assessment of the nurses in the HNHC team. The HNHC nurse most often conducted the discharge in the family’s home.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for hospital‐based neonatal home care

| Criteria |

|---|

| Postnatal gestational age of 34 weeks |

| No weight restriction |

| Normal body temperature without heating support for two days |

| Nonsmoking home |

| One parent capable of communicating without an interpreter |

| Having a car available. |

The individualised parental support programme was based on earlier research about parents’ experiences and needs, supportive person‐centred communication (PCC) (30) and FCC (15). PCC is based on trustworthy dialogues, focused on meeting and understanding a person within her/his unique personal context and achieving a mutual understanding and solution based on the person’s needs and experiences (30).

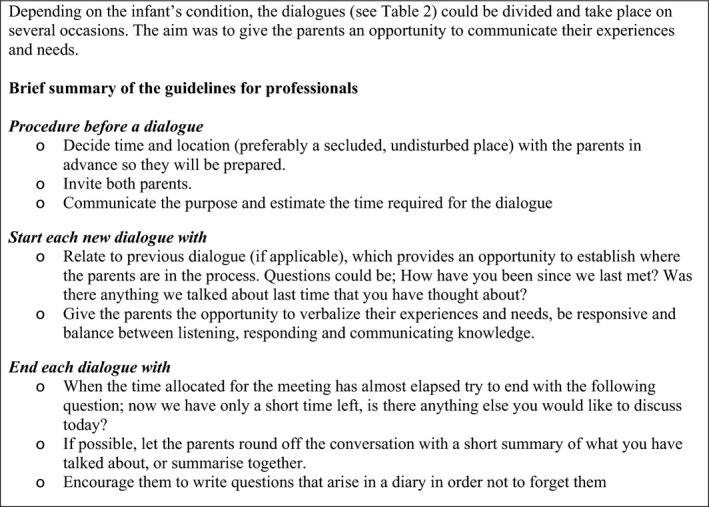

The programme included four dialogues (Table 2) that are briefly summarised in Fig. 1. In addition to regular information about the infant’s condition and care, the nurse provided the dialogues. The last dialogue took place in connection with discharge from HNHC. Before the programme was introduced, the staff received education in FCC and PCC. The content of the FCC education is summarised in Table 3.

Table 2.

Dialogues in the parental support programme a

| Dialogue | Content based on the parents’ needs |

|---|---|

| A1 | Reflect on the preterm delivery and the unexpected situation |

| A2 | Reflect on the infant’s needs and appearance |

| B | Communicate about how to interpret and interact with the infant |

| C1 | Communicate about parents’ reactions and relationship |

| C2 | Communicate about future discharge |

| D | Summarise the experiences of the care period including HNHC |

The dialogue was conducted in no particular order.

Figure 1.

Brief summary of the parental support programme.

Table 3.

Education in Family‐centred care (FCC)

Sample and data collection

As part of a larger quasi‐experimental longitudinal study to evaluate the parental support programme, 15 fathers participated in individual narrative interviews about their experiences of caring for their preterm infant at the NICU and in HNHC after the support programme was introduced. The interviews were performed over a 15‐month period, and the data collection was completed in 2015. Seven fathers were included in the present study due to their rich narratives about the phenomenon. The excluded interviews had the same major content as those included but were less informative. The fathers’ ages ranged from 25 to 45 years, six had become fathers to singletons and one to twins, they were living with their infant’s mother and worked outside the home. Their infants were born between 302 to 343 gestational weeks with birth weights ranging from 1,255 to 2,615 gm. The length of stay at the neonatal unit and in HNHC varied between 6 to 29 days (md 10) and 13 to 31 days (md 24), respectively.

The interviews were conducted in the fathers’ homes in accordance with their wishes, approximately one to two weeks after discharge from HNHC to give them an opportunity to adapt at home but still have vivid memories. The interviews started with an open‐ended question: ‘Please narrate your experiences of caring for your infant in the neonatal unit and at home in hospital‐based neonatal home care’. Probing questions were posed during the interviews to give the fathers the possibility to expand on their lived experience. The interviews lasted between 40 to 80 minutes were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by a secretary.

Ethical approval and considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 2013 (45) and approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee in Lund (Ref. 2012/96; 2012/680). In accordance with the principle of autonomy, the fathers volunteered for the interview and received oral and written information about the study. They were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time during the interview or at a later stage in the process, that the information they provided would be treated confidentially and that they would not be recognisable by name or other personal characteristics in the presentation of the results. This study aimed to be in line with the principals of benevolence and doing no harm (31). The authors discussed the fact that intimate information about each father’s partner was mentioned in the interviews. As part of the larger study, the mothers were also interviewed about the phenomenon and were aware that they would be indirect participants in the present study. The participants were informed about the opportunities to have support if they became emotionally distressed when talking about the experience of premature birth and living with a preterm infant, but none of them considered it necessary.

Analysis

The authors read and analysed one interview at a time. Phenomenological analysis according to Giorgi’s outlines was applied (28). Giorgi emphasises that phenomenological reduction will infiltrate the entire analysis of the studied phenomenon. This reduction implies that the spontaneous meaning units are reformulated in a scientific language without losing the essential content. The researchers set aside their own preunderstandings in accordance with Giorgi’s phenomenological principle of epoché or bracketing, which aims to avoid preconceptions and expectations in order to facilitate the study of the phenomenon as it appears and to describe it as objectively as possible. However, it is difficult to do that in a full extent but the authors were conscious about their personal experiences as parents and grandfather and marital experiences, their professional experiences as clinical nurses and researchers, marital counsellors and academic teachers. Our personal value systems’ were discussed during the analysis. In the present study, only the third author has experience as a neonatal nurse, which reduces the risk of the interpretation being based on the author’s own experiences of neonatal care. The analysis maintains the naturalistic posture throughout the phenomenological analysis (27, 28). However, it is difficult to totally avoid influences from the authors’ professional backgrounds, life experiences, and values, as such influences are mainly unconscious.

The initial reading of the interviews was intended to provide an overall picture of what each interview was about without creating themes or categories. It became a provisional whole, and later in the process the interviews were analysed to a new whole. In the second step, the first author identified meaning‐giving units by taking out utterances from the original text that described different aspects of the phenomenon. These meaning units were linked to the phenomenon by their capacity to fulfil the aim. This was done with as little interpretation as possible. In the third step, the first author reduced the original, spontaneous meaning units, concentrating the meaning of the utterances to make them more manageable. The subject of the text was transformed from the first to the third person, placing the focus on the relationship of the meaning units and the phenomenon. The reduced meaning units were formulated in the third person singular to enhance objectivity.

In the fourth step of analysis Giorgi claims that it is necessary to complement the caring science perspective with some constituents (existential) sensitive to the phenomenon being investigated. The constituents emanate from the data itself and according to Giorgi are used as organising principles in the analysis and cannot be described until the researcher becomes very familiar with the interview data. In discussion with the second and third authors, four constituents were chosen; Time, Space, Body (both mental and physical body) and Relationships. These constituents were used to organise the data set, including the reduced meaning units and were placed in a schematic diagram to gain an overview of the analysis. In the fifth step, the interrelatedness of the constituents was analysed to describe the causal relationships between them in order to determine the specific structure of essence of each interview. Giorgi emphasises the importance of presenting a causal aspect of the specific essence. This is contrary to the claim of most qualitative analyses that causality is not possible. In the sixth step, the first author strived to find a description of the themes within each constituent in the entire data set, taking into account their interrelatedness in order to describe the general structure of the essence of the phenomenon under study (27, 28). The three authors discussed the analysis in an ongoing process until consensus was achieved.

Findings

According to Giorgi (28), the general structure provides the essence of the phenomenon under study. Based on the reduced meaning units linked to the constituents concerning the specific structure of each interview, four themes emerged providing the general structure of the phenomenon. The fathers focused on being present for the mother, as they experienced strong concern for her because they felt that she had a great responsibility for the infant. A certain amount of concern about the infant’s health and development was also present. The fathers perceived that the professionals took them seriously when they communicated their needs and wishes. Although the professionals supported and motivated the fathers to take part in their infant’s care, the fathers would have liked a more active approach. In addition, the fathers expressed that they were not always treated with the same respect and attention as their partner. The fathers described that neonatal home care promotes the development of the father role.

The partner was constantly present in the fathers’ minds

The fathers focused on the relationship with their partner both at the NICU and in HNHC. They felt that the mother was the most important person and that their own role was to support her. Fathers described placing greater responsibility for the infant’s care on the mother. They tried to be sensitive to the needs of their partner, which resulted in their own needs being ignored, and when it came to decision‐making, the mothers had the last word.

‘…I really would not have minded if we could stay another day or two. But then again, it was different for F (the mother) who was hospitalised the whole time, I think she was a bit, well, a bit bored towards the end’(136)

The fathers described feelings of not supporting their partner enough, which were associated with a sense of guilt. These feelings were present both during the period at the NICU and during HNHC.

The fathers felt confident that their partner had a good overview of tasks at home and cared for their infant in a ‘perfect way’ (108). They were not always present when the mother received information about home care or other important issues and realised that this might have prompted the mothers to take a greater responsibility.

The relationship was affected by having fewer hours of sleep, which made them more easily irritated with each other. Nevertheless, the fathers appreciated spending time with their partner, expressed that the experience of having a preterm infant had strengthened their bond, and deepened the relationship. When they arrived home, they tried to show each other appreciation and found it important to nurture their relationship.

‘I feel like it has almost made us even closer’ (140)

The fathers’ were occupied by worries and concerns

The fathers felt distressed by having a preterm infant, even though everything had turned out well. They worried about the infant’s care and health, and if and how the preterm birth would affect the infant’s health in the future.

‘Even if we felt really safe the whole time, we were still worried all the time about this little vulnerability, I would say, about what could happen’ (116)

They felt more secure when the infant had the alarm on and had learned to manage some of the monitoring equipment in the NICU. They worried when it was time to remove it, which negatively affected their sleep. Some of the fathers felt insecure in this situation and wished that the professionals had supported them more actively.

The fathers also wished that the mother had received more attention from the professionals. The focus had mainly been on the infant, and the fathers expressed that the mother would have also needed special attention.

‘… a bit more attention to M (the mother). There is so much focus on the child already’ (144)

However, they felt more secure when the NICU professionals were nearby. The fathers expressed some concern about going home, but the HNHC support made them feel more confident. Concerns about the family’s finances, their work and how things would turn out when they returned to work were expressed, especially in terms of the mother’s burden in taking care of the infant during the day.

The fathers felt that they were an active partner to the professionals

The professionals played an important role in empowering the fathers. The fathers described flexibility among the professionals regarding how much guidance and assistance they needed, stating that the professionals had a positive attitude, were helpful and provided good support. They felt that their questions were taken seriously and that both the nurses and doctors had been available to answer questions and encouraged them to play an active part in decision‐making. Although they were grateful for the support, they also found being constantly confronted by professionals exhausting.

However, some feelings of being excluded as a father were expressed, especially in situations where the professionals focused strongly on the mother and, such as breastfeeding. At times, they perceived themselves as a hindrance or forgotten and unimportant. The fathers sometimes did not feel fully responsible for the infant when the nurses were present.

‘It feels like you are a bit forgotten as the father, you are not as important, even if you feel like they are attending to your needs and whatnot’ (160)

Information about the possibility of HNHC gave them time to reflect before making a decision. They received both written and oral information and were generally positive towards going home with the support of HNHC, expressing that the home care nurses met their needs when adopting the parent role. The fathers perceived that they and their partner ‘were treated equally during the home care and that the home care nurses addressed them both’ (116). The content of the information given to them as parents was adapted according to their individual needs, and the home care nurses made sure that the communicated message was understood.

Getting the opportunity to take responsibility

The fathers appreciated spending time with their infant after the birth. Before, they had mainly focused on the mother. The professionals usually acted in a way that enabled the fathers to adapt quickly, which they appreciated. However, they wished that they had been challenged to take greater responsibility at the NICU. They also wished they had been given the possibility to move to a SFR earlier, because this was where they first had the opportunity to take more initiative, which made them more emotionally involved. However, some experienced being ‘thrown into parenthood’ (144) and would have liked the professionals to have guided them more actively.

The hospital environment was taxing, and they felt a strong desire to go home and resume their everyday lives. Some fathers experienced that they could have gone home earlier as they were already taking care of the infant themselves day and night.

‘….the last week, they more or less only came in with the food and then I did the rest.’ (108)

HNHC was a good transition to assuming responsibility for the infant and having more control over family life while still in the safe hands of neonatal professionals. The fathers expressed that it was at home that they really felt like a parent for the first time. HNHC gave the parents extra time to grow together as a family in their own home environment. The fathers stated that HNHC was a good option for them as the environmental change alone meant a great deal.

‘So it was pretty nice to come home… I was thinking about S (sibling) too, especially about her, that the situation was the worst for her’ (140)

The fathers expressed that being by themselves as a family had strengthened them, which was made possible by HNHC without any risk to the infant. Caring for their infant at home was described as providing a sense of freedom and as a reward. They saw it as an acknowledgement that they were ready to take care of the infant by themselves as a family.

Discussion

The present study provides insight into fathers’ lived experiences of caring for their preterm infant at the NICU and in HNHC after the introduction of a parental support programme. The programme was grounded in FCC (15), part of which was introduced at the unit where the study took place. Prior to the start of the study, the professionals underwent education in FCC and PCC. This study focuses on fathers’ experiences as it is an important topic due to fathers’ increased involvement in neonatal care, which is vital for the infant’s psychological and cognitive outcomes (32).

The fathers in our study felt that they were an active partner to the professionals, who encouraged them play an active role in care procedures and decision‐making. The professionals had a positive attitude, provided good support and were flexible regarding how much guidance and assistant the fathers needed. This is in line with a study by Hagen et al. (2019), who found that the most important areas for parent satisfaction with NICU care were being included in decision‐making and treated with respect (33). There is evidence of how important it is for fathers of preterm infants to be engaged in their infant’s care (34, 35). Involving parents in their infant’s care and decision‐making are two important aspects of FCC. However, they are dependent on the establishment of a positive partnership between the parents and the professionals, which may be achieved by close collaboration where they set and achieve the goals for the infants’ care together (36). One of the challenges in establishing a positive partnership is that the nurses need to shift their professional role from an expert to a guide who supports the parents throughout the NICU journey. Accordingly, nurses need both education and training to succeed in this role change (37).

Although the fathers in our study were pleased with the support received at the NICU, they described feelings of exclusion and not being fully responsible for their infant. Similar results are presented in earlier studies where fathers experienced an unclear parental role, had trouble finding their place in the NICU and felt less important as a parent compared to the mother (3, 11, 38). Lundqvist, Weis and Sivberg (2019) found that parents experienced ambivalent feelings in their relationship with NICU professionals, fathers to a lesser extent than mothers. The parental support from nurses seemed to depend on the nurses’ preferences and availability (39). The reason why fathers in our study felt excluded is difficult to explain. However, when discussing the support programme’s influence on fathers’ experiences, it is important to consider that although all nurses at the NICU received education in FCC and PCC, the time‐period between the education and the start of the study might have been too short, resulting in a lack of confidence when using the parental support programme in everyday practice. It might have enhanced the programme if a facilitator had been used during the study period to assist the professionals in using it (40). The starting point in the dialogues was PCC, a communication style based on partnership (30). Using PCC is in line with a family‐centred approach (15). Parents’ communication with the professionals is essential for their experiences at the NICU (41, 42). The PCC style was new to the professionals and as described by Hall et al. (2015), NICU nurses are not fully trained to communicate with distressed parents (43).

The theme ‘The partner was constantly present in the fathers’ mind’ is in line with earlier research. Fathers prioritising the mother has been described in several studies (3, 34, 39) and seems to persist, although NICU care has changed over the years towards a family‐centred approach and thereby greater inclusion of fathers. In the present study, the fathers left the majority of responsibility and decision‐making concerning the infant’s care to their partner. When it comes to starting a family, many men in the modern, secularised Swedish society still express ideas and feelings related to a traditional male role, which requires them to take overarching responsibility for the family as a breadwinner and hand over the main responsibility for the infant’s care to the mother. However, in the last two decades, fathers have become more inclined towards the idea of active parenting (44). This is in line with a Danish study discussing fathers’ needs when their infant was admitted to a NICU within a framework of masculinity (34). However, when transferred to a SFR the fathers started to become more involved in their infant’s care and decision‐making and assumed greater responsibility. This responsibility was further increased during the time in HNHC. Tandberg et al. (2019) described that parents in a SFR became more involved in participation and decision‐making due to the fact that they were more present (45).

In our study, the fathers worried about their infant’s health and the alteration of their parental role, in line with earlier research (6, 7). They also found the hospital environment taxing and were positive to HNHC as it gave them more control over family life and promoted the development of their father role. Neonatal home care has been implemented in several neonatal units in Sweden because of its contribution to quality improvements for the family by earlier normalisation of family life and activating the family members’ own resources but also because it is cost‐effective (23, 24).

Strengths and limitations

The authors adhered to the phenomenological descriptive method and made efforts to give a clear and rich description of the method and the analysis to show the conditions under which the knowledge emerged. Furthermore, the analysis process involved all authors. The study has a well‐defined aim, and the authors believe that the phenomenon under study was emphasised. The interviews lasted from 40 to 80 minutes, which provided rich narratives of the fathers’ experiences. There was also variation among the fathers in terms of age, occupation, and number of children, implying more variety in the themes.

The study has some limitations. All fathers were interviewed about two weeks after discharge from HNHC; thus, the short time span could have influenced the fathers’ experiences, due to having more positive memories fresh in their mind and possibly forgetting their NICU experiences. All fathers were Swedish thus represent male Swedish culture and behaviours. It might be that fathers with different ethnicity experiences the phenomenon differently.

Conclusions and clinical implications

The study indicates that the parental support programme might play a role in supporting and encouraging fathers. However, despite the programme some of the fathers felt excluded and not fully responsible for their infant. Although the fathers experienced feelings of worry and distress, their initial focus was on the mother’s needs, implying that they ignored their own needs. The general structure of fathers’ experiences highlights the importance of professionals being more responsive to fathers’ needs and tailoring the support to each father’s individual needs.

As the programme was based on FCC and PCC, an observational study focusing on the dialogues between the nurses and parents might be one way of obtaining valuable information to further develop the parental support programme. Moreover, there is a need to identify and address any barriers that affected the implementation of the programme.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Author’s contribution

The first author was responsible for the analysis and writing the manuscript. The second author assisted with the analysis and writing the manuscript. The third author designed the study, was involved in the data collection and assisted with the analysis and writing the manuscript. All three authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors express their gratitude to the fathers who participated in the study. We thank Maria Nilsson, Ingrid Knutsson and Marie Winqvist, RSCN for their help in the data collection. We also thank Berit Nordström, licensed psychologist, PhD and Lisbeth Jönsson, RSCN, PhD for their valuable comments during the development phase of the support programme. This work was supported by Fanny Ekdahl (no grant number) and The Crafoord foundation (grant number 20130840).

Scand J Caring Sci;2021; 35: 1143–1151 Fathers' lived experiences of caring for their preterm infant at the neonatal unit and in neonatal home care after the introduction of a parental support programme: A phenomenological study

References

- 1. Shelton SL, Meaney‐Delman DM, Hunter M, Lee S‐Y. Depressive symptoms and the relationship of stress, sleep, and well‐being among NICU mothers. JNEP 2014; 4: 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Woodward LJ, Bora S, Clark CAC, Montgomery‐Hönger A, Pritchard VE, Spencer C et al. Very preterm birth: maternal experiences of the neonatal intensive care environment. J Perinatol 2014; 34: 555–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garten L, Nazary L, Metze B, Buhrer C. Pilot study of experiences and needs of 111 fathers of very low birth weight infants in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol 2013; 33: 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lundqvist P, Hellstrom‐Westas L, Hallstrom I. Reorganizing life: A qualitative study of fathers' lived experience in the 3 years subsequent to the very preterm birth of their child. J Pediatr Nurs 2014; 29: 124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hollywood M, Hollywood E. The lived experiences of fathers of a premature baby on a neonatal intensive care unit. J Neonatal Nurs 2011; 17: 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Busse M, Stromgren K, Thorngate L, Parents' Thomas KA. responses to stress in the neonatal intensive care unit. Crit care nurse 2013; 33: 52–59; quiz 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mansson C, Sivberg B, Selander B, Lundqvist P. The impact of an individualised neonatal parent support programme on parental stress: a quasi‐experimental study. Scand J Caring Sci 2019; 33: 677–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abuidhail J, Al‐Motlaq M, Mrayan L, Salameh T. The Lived Experience of Jordanian Parents in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Phenomenological Study. J Nurs Res 2017; 25: 156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Welch MG, Myers MM. Advances in family‐based interventions in the neonatal ICU. Curr Opin Pediatr 2016; 28: 163–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feeley N, Waitzer E, Sherrard K, Boisvert L, Zelkowitz P. Fathers' perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to their involvement with their newborn hospitalised in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs 2013; 22: 521–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lundqvist P, Westas LH, Hallstrom I. From distance toward proximity: fathers lived experience of caring for their preterm infants. J Pediatr Nurs 2007; 22: 490–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hagen IH, Iversen VC, Svindseth MF. Differences and similarities between mothers and fathers of premature children: a qualitative study of parents' coping experiences in a neonatal intensive care unit. BMC Pediatr 2016; 16: 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hynan MT, Mounts KO, Vanderbilt DL. Screening parents of high‐risk infants for emotional distress: rationale and recommendations. J Perinatol 2013; 33: 748–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoffenkamp HN, Braeken J, Hall RA, Tooten A, Vingerhoets AJ, van Bakel HJ. Parenting in Complex Conditions: Does Preterm Birth Provide a Context for the Development of Less Optimal Parental Behavior? J Pediatr Psychol 2015; 40: 559–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Institute for Patient and Family‐ Centered Care (IPFCC) . Available from: http://www.ipfcc.org/faq.html

- 16. De Bernardo G, Svelto M, Giordano M, Sordina D, Riccitelli M. Supporting parents in taking care of their infants admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study. Ital J Pediatr 2017; 43: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anderzen‐Carlsson A, Lamy ZC, Tingvall M, Eriksson M. Parental experiences of providing skin‐to‐skin care to their newborn infant–part 2: a qualitative meta‐synthesis. Int J Qual Stud Health Weel‐being 2014; 9: 24907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Westrup B. Family‐centered developmentally supportive care: the Swedish example. Arch Pediatr 2015; 22: 1086–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arshadi Bostanabad M, Namdar Areshtanab H, Balila M, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Ravanbakhsh K. Effect of a Supportive‐Training Intervention on Mother‐Infant Attachment. Iran J Pediatr 2017; 27: e10565. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Turan T, Basbakkal Z, Ozbek S. Effect of nursing interventions on stressors of parents of premature infants in neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs 2008; 17: 2856–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weis J, Zoffmann V, Greisen G, Egerod I. The effect of person‐centred communication on parental stress in a NICU: a randomized clinical trial. Acta Paediatr 2013; 102: 1130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glazebrook C, Marlow N, Israel C, Croudace T, Johnson S, White IR et al Randomised trial of a parenting intervention during neonatal intensive care. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal ED 2007; 92: F438–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lundberg B, Lindgren C, Palme‐Kilander C, Ortenstrand A, Bonamy AK, Sarman I. Hospital‐assisted home care after early discharge from a Swedish neonatal intensive care unit was safe and readmissions were rare. Acta Paediatr 2016; 105: 895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hammarstrand E, Jönsson L, Hallström I. A neonatal home care program ‐ an evaluation for the years 2002–2005. Vård i Norden 2008; 90: 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hadian Shirazi Z, Sharif F, Rakhshan M, Pishva N, Jahanpour F. Lived Experience of Caregivers of Family‐Centered Care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: "Evocation of Being at Home. Iran J Pediatr 2016; 26: e3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Awindaogo F, Smith VC, Litt JS. Predictors of caregiver satisfaction with visiting nurse home visits after NICU discharge. J Perinatol 2016; 36: 325–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giorgi A (ed). Phenomenology and Psychological Research. 1985, Duquesne University Press, Pittsburgh. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Giorgi A. The Theory, Practice, and Evaluation of the Phenomenological Method as a Qualitative Research Procedure. J Phenomenol Psychol 1997; 28: 235–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Giorgi A. The status of Husserlian phenomenology in caring research. Scand J Caring Sci 2000; 14: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL, Duberstein P. Measuring patient‐centered communication in patient‐physician consultations: theoretical and paractical issues. Soc Sci Med 2005; 61: 1516–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Helsinki Declaration (2013). Ethical Principles for Medical Research involving Human Subjects. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies‐post/wma‐declaration‐of‐helsinki‐ethical‐principles‐for‐medical‐research‐involving‐human‐subjects/.

- 32. Sarkadi A, Kristiansson R, Oberklaid F, Bremberg S. Fathers' involvement and children's developmental outcomes: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatr 2008; 97: 153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hagen IH, Iversen VC, Nesset E, Orner R, Svindseth MF. Parental satisfaction with neonatal intensive care units: a quantitative cross‐sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019; 19: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Noergaard B, Ammentorp J, Fenger‐Gron J, Kofoed PE, Johannessen H, Thibeau S. Fathers' Needs and Masculinity Dilemmas in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Denmark. Adv Neonatal Care 2017; 17: E13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stefana A, Padovani EM, Biban P, Lavelli M. Fathers' experiences with their preterm babies admitted to neonatal intensive care unit: A multi‐method study. J Adv Nurs 2018; 74: 1090–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brødsgaard A, Pedersen JT, Larsen P, Weis J. Parents' and nurses' experiences of partnership in neonatal intensive care units: A qualitative review and meta‐synthesis. J Clin Nurs 2019; 28: 3117–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Trajkovski S, Schmied V, Vickers M, Jackson D. Neonatal nurses' perspectives of family‐centred care: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 2477–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Logan RM, Dormire S. Finding My Way: A Phenomenology of Fathering in the NICU. dv Neonatal Care 2018; 18: 154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lundqvist P, Weis J, Sivberg B. Parents' journey caring for a preterm infant until discharge from hospital‐based neonatal home care‐A challenging process to cope with. J Clin Nurs 2019; 28: 2966–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rogers M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th edn. 2003, Free Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Russell G, Sawyer A, Rabe H, Abbott J, Gyte G, Duley L, Ayers S. Parents' views on care of their very premature babies in neonatal intensive care units: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr 2014; 2014: 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wigert H, Dellenmark Blom M, Bry K. Parents' experiences of communication with neonatal intensive‐care unit staff: an interview study. BMC Pediatr 2014; 14: 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hall SL, Cross J, Selix NW, Patterson C, Segre L, Chuffo‐Siewert R, Geller PA, Martin ML. Recommendations for enhancing psychosocial support of NICU parents through staff education and support. J Perinatol 2015; 35(Suppl 1): S29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Livia SZ, Oláh IE, Richter K, Richter R. The new roles of men and women and implications for families and societies. In A Demographic Perspective on Gender, Family and Health in Europe. (Doblhammer G, Gumà J eds), 2018, Springer Nature, Cham, 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tandberg BS, Flacking R, Markestad T, Grundt H, Moen A. Parent psychological wellbeing in a single‐family room versus an open bay neonatal intensive care unit. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0224488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Als H, McAnulty GB. The Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) with Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC): Comprehensive Care for Preterm Infants. Curr Womens Health Rev 2011; 7: 288–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]