Abstract

The analysis of the non‐exchangeable hydrogen isotope ratio (δ2Hne) in carbohydrates is mostly limited to the structural component cellulose, while simple high‐throughput methods for δ2Hne values of non‐structural carbohydrates (NSC) such as sugar and starch do not yet exist. Here, we tested if the hot vapor equilibration method originally developed for cellulose is applicable for NSC, verified by comparison with the traditional nitration method. We set up a detailed analytical protocol and applied the method to plant extracts of leaves from species with different photosynthetic pathways (i.e., C3, C4 and CAM). δ2Hne of commercial sugars and starch from different classes and sources, ranging from −157.8 to +6.4‰, were reproducibly analysed with precision between 0.2‰ and 7.7‰. Mean δ2Hne values of sugar are lowest in C3 (−92.0‰), intermediate in C4 (−32.5‰) and highest in CAM plants (6.0‰), with NSC being 2H‐depleted compared to cellulose and sugar being generally more 2H‐enriched than starch. Our results suggest that our method can be used in future studies to disentangle 2H‐fractionation processes, for improving mechanistic δ2Hne models for leaf and tree‐ring cellulose and for further development of δ2Hne in plant carbohydrates as a potential proxy for climate, hydrology, plant metabolism and physiology.

Keywords: growth, NSC, photoperiod, photosynthesis, secondary metabolism, δ2H

Short abstract

Here, we present a hot water‐vapor equilibration method that is suitable for high‐throughput δ2Hne analysis of sugar and starch. Additionally, we show first insights into differences of δ2Hne values within and between C3, C4 and CAM plant species growing under the same constant climatic conditions.

1. INTRODUCTION

The isotopic composition of carbohydrates, which are the primary building blocks of plant biomass, is well known as a useful proxy for hydro‐climatic conditions and plant physiological processes that have occurred during their biosynthesis (Gaglioti et al., 2017; Gessler et al., 2014; Manrique‐Alba et al., 2020; McCarroll & Loader, 2004; Porter et al., 2014; Sass‐Klaassen et al., 2005; Saurer et al., 2012; Saurer, Borella, & Leuenberger, 1997). Various high‐throughput methods have been developed to study the carbon and oxygen isotopic composition of non‐structural plant carbohydrates (NSC; i.e., sugar and starch) (Lehmann et al., 2020; Richter et al., 2009; Wanek, Heintel, & Richter, 2001), and of structural carbohydrates such as tree‐ring or leaf cellulose (Boettger et al., 2007). In contrast, methods to investigate the non‐exchangeable hydrogen isotopic composition (δ2Hne) in plant carbohydrates are still mainly limited to cellulose (An et al., 2014; Arosio, Ziehmer, Nicolussi, Schlüchter, & Leuenberger, 2020; Epstein, Yapp, & Hall, 1976; Filot, Leuenberger, Pazdur, & Boettger, 2006; Mischel, Esper, Keppler, Greule, & Werner, 2015; Nakatsuka et al., 2020; Sauer, Schimmelmann, Sessions, & Topalov, 2009; Xia et al., 2020). Existing methods to analyse δ2Hne values of NSC use site‐specific natural isotope fractionation nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) or sample derivatization prior to isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) (Abrahim, Cannavan, & Kelly, 2020; Augusti, Betson, & Schleucher, 2008; Dunbar & Schmidt, 1984; Schleucher, Vanderveer, Markley, & Sharkey, 1999; Zhang, Quemerais, Martin, Martin, & Williams, 1994). These methods are, however, very laborious and limited by their sample throughput and/or produce explosive compounds that are difficult to work with. As a result, publications reporting δ2Hne values of NSC are rare (Dunbar & Wilson, 1983; Ehlers et al., 2015; Luo & Sternberg, 1991). However, recent studies show the great potential of δ2H values of plant compounds to retrospectively determine hydrological and climatic conditions (Anhäuser, Hook, Halfar, Greule, & Keppler, 2018; Gamarra & Kahmen, 2015; Hepp et al., 2015, 2019; Sachse et al., 2012), as well as to disentangle metabolic and physiological processes (Cormier et al., 2018; Estep & Hoering, 1981; Sanchez‐Bragado, Serret, Marimon, Bort, & Araus, 2019; Tipple & Ehleringer, 2018) such as the proportional use of carbon sources (i.e., fresh assimilates vs. storage compounds) for plant growth (Lehmann, Vitali, Schuler, Leuenberger, & Saurer, 2021; Zhu et al., 2020). Enabling the analysis of δ2Hne of NSC, especially sugar at the leaf level, will make it possible to study processes and environmental conditions which are shaping the 2H‐fractionation of carbohydrates at a much higher time resolution compared to the analysis of δ2Hne of cellulose. New routines and high‐throughput analytical methods for δ2Hne values of NSC are thus needed to enable widespread application in earth and environmental sciences.

The difficulty of establishing reliable methods for δ2Hne values of NSC and cellulose is mainly caused by the presence of oxygen‐bound hydrogen atoms (Hex) that can freely exchange with hydrogen atoms of the surrounding liquid water and water vapor. The interference of Hex greatly affects the analysis of δ2Hne, which retains useful information on climate, hydrology, metabolism and physiology. The oldest method of measuring δ2Hne is to derivatize hydroxyl groups with nitrate esters, using a mixture of either H2SO4 or H3PO4 with HNO3 (Alexander & Mitchell, 1949; Boettger et al., 2007; DeNiro, 1981; Epstein et al., 1976). However, the nitration process requires a large sample amount, is labour intensive, uses hazardous derivatization reactions and leads to thermally unstable products. A newer derivatization method to measure δ2Hne in sugars is using N‐methyl‐bis‐trifluoroacetamide to replace Hex with trifluoroacetate derivatives, which are measured by gas chromatography ‐ chromium silver reduction/high‐temperature conversion‐IRMS (GC‐CrAg/HTC‐IRMS) (Abrahim et al., 2020). This method still relies on a large sample amount of >20 mg extracted NSC, a relatively long measuring time, and the limitation of measuring only one element per analysis. Potential alternative methods that work without derivatization and use smaller amounts of material are based on water vapor equilibration, which sets Hex to a known isotopic composition that allows the determination of δ2Hne by mass balance (Cormier et al., 2018; Filot et al., 2006; Sauer et al., 2009; Schimmelmann, 1991; Wassenaar & Hobson, 2000). However, established water vapor equilibration methods are mainly calibrated for analysis of δ2Hne values of complex molecules such as cellulose, keratin and chitin (Schimmelmann et al., 1986; Wassenaar & Hobson, 2000) and whether these methods can also be used for the analysis of δ2Hne in NSC remains to be shown. The main purpose of this study was therefore to establish a high‐throughput hot water vapor equilibration method to determine δ2Hne of NSC, based on already established protocols for cellulose (Sauer et al., 2009). Nitration of cellulose and starch was additionally applied as an independent method to verify our results. Finally, we used the method to determine δ2Hne values of NSC and cellulose extracted from leaves of plant species with different photosynthetic pathways (C3, C4 and CAM) grown under the same controlled climatic conditions.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cellulose, starch and sugar standards

As reference materials, we used both commercially available (n = 4; spruce cellulose, Fluka, Honeywell International Inc., Morristown, New Jersey, U.S.A., Prod. No. 22181; IAEA‐CH‐3, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Vienna, Austria; Merck cellulose (Cellulose native no. 2351, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), Wei Ming (CYCLOCEL® Microcrystalline Cellulose, Wei Ming Pharmaceutical MFG. co., LTD., Taipei City, Taiwan), and in‐house produced cellulose standards (n = 5; Isonet, spruce, beech, Spain and Siberia), commercially available starch standards (n = 4; starch from maize, Fluka, Prod. No. 85652; starch from rice, Calbiochem, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, Prod. No. 569380; starch from wheat, Fluka, Prod. No. 85649 and starch from potato, Merck, Prod. No. 1.01259.0250), commercially available standards for sugars of different classes (n = 6; sucrose, Merck, Prod. No. 1.07687; d‐(+)‐glucose ≥99.5%, SIGMA Life Science, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A., Prod. No. 49139; d‐(−)‐fructose ≥99%, Fluka, Prod. No. 47739; d‐(+)‐raffinose pentahydrate ≥99%, Fluka, Prod. No. 83400; d‐(+)‐trehalose dihydrate ≥99%, SIGMA Life Science, Prod. No. T9449 and myo‐Inositol ≥99.5%, Sigma Life Science, Prod. No. 57569) and two household sugars (Finish sucrose from 2019, Suomalainen Taloussokeri, Kantvik, Finland; Russian sucrose, household sugar from a Russian supermarket supplier). All reference materials were oven‐dried at 60°C for 48 hr and stored in an exicator at low relative humidity (2–5%) until further use.

2.2. Plant species, growing conditions and sampling

Ten plant species with different photosynthetic pathways grown under controlled conditions in walk‐in climate chambers (Bouygues E&S InTec Schweiz AG, Zurich, Switzerland) were used to apply the new method, and compare δ2Hne of cellulose, starch and soluble sugars. The species selection covered C3 herbs and grasses (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench, Cannabis sativa L., Hordeum vulgare L., Salvia hispanica L. and Solanum cheesmaniae (L. Riley) Fosberg), C4 grasses (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench, Zea mays L.) and CAM plants (Portulaca grandiflora Hook., Kalanchoe daigremontiana Raym.‐Hamet & H.Perrier and Phalaenopsis Blume hybrid). Seeds or plantlets were sown or planted in 3 L pots containing potting soil (Kübelpflanzenerde, RICOTER Erdaufbereitung AG, Aarberg, Switzerland). The orchid Phalaenopsis was bought in a local supermarket and grown in a special substrate based on bark mulch. The climate chamber conditions were set to 16 daytime hours (30°C and 40% relative humidity), 8 nighttime hours (15°C and 60% relative humidity) and photosynthetically active radiation of 110 μmol m−2 s−1 at plant height with uniform fluorescent tubes (OSRAM L 36 W 777 Fluora, Osram Licht AG, Munich, Germany). All plants were regularly watered to field capacity with tap water (δ2H = −79.9 ± 2.4 ‰ during the experimental period) to avoid any water limitation, except for Phalaenopsis that was watered with 50 ml twice a week to keep the substrate moist but prevent root rot due to excess water. The plants were grown for three months to ensure ample leaf material was grown for harvest.

At the sampling day, three samples of fully developed mature leaves, each from individual plants or three pools of leaves of four plants in the case of H. vulgare, were sampled after 7 hr of light to allow the plants to synthesize enough sugars and starch on the day of harvest and to guarantee steady‐state leaf water enrichment conditions (Cernusak et al., 2016). The leaf samples were immediately transferred to gas‐tight 12 ml glass vials (‘Exetainer’, Labco, Lampeter, UK, Prod. No. 738W), stored on ice until the harvest was complete (≤2 hr), and then at −20°C in a freezer until further use (Appendix 1). The sample material was dried using a cryogenic water distillation method (West, Patrickson, and Ehleringer (2006), crumbled with a spatula (dicotyledon species) or cut with scissors (monocotyledon species) into small pieces, and 100 mg of the fragmented material was separated for cellulose extraction. The remaining leaf material was then ball‐milled to powder (Retsch MM400, Retsch, Haan, Germany) for NSC extraction.

2.3. Cellulose and starch nitration, and isotopic analysis of the nitrated products

Nitrates of cellulose and starch without exchangeable H were used as reference material to assess the δ2Hne values derived from the hot water vapor equilibration method. Nitration of cellulose and starch standards was performed following the method of Alexander and Mitchell (1949), using a mixture of P2O5 and 90% HNO3. δ2H values of nitrated cellulose and starch were analysed with a TC/EA‐IRMS system, using a reactor filled with chromium as described by Gehre et al. (2015). Reference materials for δ2H measurements of cellulose and starch nitrates were the IAEA‐CH‐7 polyethylene foil (PEF; International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria) for a first offset correction and the USGS62, USGS63 and USGS64 caffeine standards (United States Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia, U.S.A.) (Schimmelmann et al., 2016) for the final normalization.

All Isotope ratios (δ) are calculated as given in Equation (1) (Coplen, 2011):

| (1) |

R = 2H/1H of the sample (RSample) and of Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW2; RStandard) as the standard defining the international isotope scale. To express the resulting δ values in permil (‰), results have been multiplied by 1,000.

2.4. Preparation of leaf cellulose and NSC for δ2Hne analysis

Every compound (i.e., sugars, starch and cellulose) was extracted once per sample. Cellulose (hemicellulose) was extracted from 100 mg of the fragmented leaf material in F57 fibre filter bags (made up of polyester and polyethylene with an effective pore size of 25 μm; ANKOM Technology, Macedon NY, U.S.A.). In brief, the samples were washed twice in a 5% sodium hydroxide solution at 60°C, rinsed with deionized water, washed 3 times for 10 hr in a 7% sodium chlorite solution, which was adjusted with 96% acetic acid to a pH between 4 and 5, and subsequently rinsed with boiling hot deionized water, and dried overnight in a drying oven at 60°C. The neutral sugar fraction (‘sugar’, a mixture of sugars, typically glucose, fructose, sucrose and sugar alcohol [Rinne, Saurer, Streit, & Siegwolf, 2012]) were extracted from 100 mg leaf powder and further purified using ion‐exchange cartridges, following established protocols for carbon and oxygen isotope analyses (Lehmann et al., 2020; Rinne et al., 2012). This is needed to separate the sugar from other water‐soluble compounds such as amino acids which would alter the resulting δ2Hne values (Schmidt, Werner, & Eisenreich, 2003). Starch was extracted from the remaining pellet of the sugar extraction via enzymatic digestion following the established method for carbon isotope analysis (Richter et al., 2009; Wanek et al., 2001). The same protocol was used to hydrolyse the commercial starch standards. Aliquots of the extracted sugar (including those derived from starch) were pipetted in 5.5 × 9 mm silver foil capsules (IVA Analysentechnik GmbH & Co. KG, Germany, Prod. No. SA76981106), frozen at −20°C, freeze‐dried, folded into cubes and packed into an additional silver foil capsule of the same type, folded again and stored in an exicator at low relative humidity (2–5%) until isotope analysis.

2.5. δ2Hne analysis of cellulose and NSC using a hot water vapor equilibration method

One microgram of commercial starch or cellulose standard was packed into 3.3 × 5 mm silver foil capsules (IVA, Prod. No. SA76980506), which led to a total peak area between 20 and 30‐V seconds (Vs) of each IRMS analysis. For sugar standards, one mg was transferred first into a 5.5 × 9 mm silver foil capsule (IVA), and additionally packed in a second capsule of the same size and folded again. The reason for the double packing was the observation that sugar samples became liquefied and rinsed out of single‐packed capsules during the hot water vapor equilibration, which led to a loss of sample and to negative impacts on the analysis of δ2Hne in sugars. Such rinsing was prevented by double packing and had no negative impact on the drying time of the sugars (Appendix 2). The double packing did not have a negative impact on the equilibration itself, as indicated by the high xe of the sugars (Table 1). All packed samples were stored in an exicator at low relative humidity (2–5%) until isotope analysis.

Table 1.

Results of the hot water vapor equilibrations of cellulose, sugars and starch (including the sugars derived from digested starch) of different classes and origins (referenced against PEF)

| Ref. material | δ2He1 [‰] | SDe1 | δ2He1 [‰] | SDe2 | xe [%] | Xe.pot [%] | δ2Hne [‰] | δ2Hnitro [‰] | δ2Hne‐δ2Hnitro [‰] | Rep. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Isonet | −57.1 | 1.1 | −108.2 | 4.1 | 19.5 | 30.0 | −42.2 | −44.5 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

| Beech | −57.7 | 1.2 | −114.3 | 3.3 | 19.5 | 30.0 | −49.7 | −50.8 | 1.2 | 1.0 | |

| Spruce | −40.2 | 1.7 | −96.3 | 3.3 | 19.4 | 30.0 | −27.9 | −30.7 | 2.7 | 1.1 | |

| Spain | −49.8 | 0.8 | −114.1 | 3.7 | 22.1 | 30.0 | −33.4 | −27.7 | −5.7 | N.A. | |

| Siberia | −164.5 | 2.2 | −224.0 | 1.7 | 20.5 | 30.0 | −184.3 | −184.9 | −0.6 | N.A. | |

| IAEA | −65.1 | 1.0 | −126.0 | 2.8 | 21.0 | 30.0 | −58.2 | −57.3 | −0.9 | 1.4 | |

| Merck | −63.5 | 1.0 | −119.3 | 2.3 | 19.3 | 30.0 | −56.9 | −55.9 | −1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Fluka | −72.9 | 0.9 | −120.3 | 3.0 | 16.4 | 30.0 | −69.3 | −50.5 | −18.8 | 0.8 | |

| Wei Ming | −67.0 | 1.8 | −114.6 | 2.1 | 16.4 | 30.0 | −62.3 | −70.0 | 7.7 | 1.9 | |

| Sugar | Finn. sucrose | −133.5 | 3.7 | −239.1 | 1.3 | 36.4 | 36.4 | −157.8 | N.A. | N.A. | 5.8 |

| Russ. sucrose | −65.0 | 2.0 | −169.7 | 2.2 | 36.1 | 36.4 | −50.3 | N.A. | N.A. | 4.2 | |

| Merck sucrose | −107.5 | 3.2 | −214.2 | 1.7 | 36.8 | 36.4 | −117.0 | N.A. | N.A. | 5.8 | |

| Glucose | −31.3 | 2.2 | −143.4 | 3.6 | 38.7 | 41.7 | 6.4 | N.A. | N.A. | 4.2 | |

| Fructose | −47.6 | 2.9 | −155.3 | 3.9 | 37.1 | 41.7 | −21.9 | N.A. | N.A. | 4.9 | |

| Raffinose | −16.4 | 1.6 | −115.2 | 3.5 | 34.1 | 34.4 | 22.2 | N.A. | N.A. | 4.3 | |

| Trehalose | −91.4 | 2.1 | −196.1 | 3.3 | 36.1 | 36.4 | −91.5 | N.A. | N.A. | 4.0 | |

| Myo‐Inositol | −91.5 | 3.7 | −246.6 | 7.7 | 53.5 | 50.0 | −91.8 | N.A. | N.A. | 8.6 | |

| Starch | Maize | −32.9 | 1.2 | −96.2 | 0.8 | 21.8 | 30.0 | −16.6 | −13.4 | −3.1 | N.A. |

| Maize starch hydrolysed | −41.4 | 0.5 | −132.7 | 1.8 | 31.5 | 41.7 | −18.6 | −13.4 | −5.1 | N.A. | |

| Rice | −71.6 | 2.0 | −136.7 | 0.5 | 22.5 | 30.0 | −65.9 | −67.2 | 1.2 | N.A. | |

| Rice starch hydrolysed | −76.2 | 1.1 | −169.1 | 1.0 | 32.0 | 41.7 | −69.2 | −67.2 | −2.0 | N.A. | |

| Wheat | −58.4 | 2.1 | −110.2 | 0.2 | 17.8 | 30.0 | −51.3 | −53.7 | 2.3 | N.A. | |

| Wheat starch hydrolysed | −71.0 | 0.3 | −162.9 | 0.2 | 31.7 | 41.7 | −61.6 | −53.7 | −8.0 | N.A. | |

| Potato | −127.1 | 1.8 | −194.0 | 4.5 | 23.0 | 30.0 | −137.9 | −143.2 | 5.3 | N.A. | |

| Potato starch hydrolysed | 129.1 | 1.1 | −221.8 | 3.7 | 32.0 | 41.7 | −147.0 | −143.2 | −3.7 | N.A. |

Note: The following variables are given: δ2He1 and δ2He2 are average δ2H values in ‰ of all replicates and repetitions (cellulose and sugars as three independent repetitions with each water, each time in triplicates; starch and digested starch as one measurement per water with three replicates) with e1 representing the equilibration with water 1 and e2 representing the equilibration with water 2, SDe1 and SDe2 are the standard deviations of all repetitions (= precision), xe depicts the proportion of exchanged hydrogen during the equilibration in % [Equation (2)], xe.pot is the potential maximum proportion of exchangeable hydrogen based on the proportion of oxygen‐bound hydrogen in %, δ2Hne represents the calculated δ2H of the non‐exchangeable hydrogen in ‰ [Equation (3)], δ2Hnitro denotes the δ2H of the corresponding nitrated compound in ‰, δ2Hne‐δ2Hnitro depicts the difference between δ2Hne and δ2Hnitro in ‰ (= accuracy), Rep. = reproducibility, given as standard deviation between the resulting δ2Hne of the three independent repetitions for cellulose and sugars in ‰, N.A., not available.

All samples were equilibrated in a home‐built offline equilibration system (Appendix 3), consisting of a heating oven with an in‐house designed equilibration chamber (Appendix 4) connected to a peristaltic pump (Gilson Incorporated, Middleton, USA). The equilibration chamber consisted of a sampler carousel (Zero Blank Autosampler, N.C. Technologies S.r.l., Milano, Italy) for solid samples with 50 cylindrical sample positions, where samples and reference materials could be placed, inserted into a cubic stainless steel chamber with a heat‐stable Viton ® O‐rings (Maagtechnic AG, Dübendorf, Switzerland, Prod. No. 15087359) surrounding the autosampler tray. The top of the chamber was sealed with a stainless steel metal plate using one stainless steel clamp at each corner. In the middle of the top metal plate, one inlet and one outlet connector were installed (Appendix 5). The inlet was connected to a stainless steel tube (i.e., feeding capillary, BGB, Switzerland), which was leading out of the oven where a santoprene pump tubing was fitted into a peristaltic pump (Appendix 6). The end of the santoprene pump tubing was inserted into a 50 ml falcon tube containing the equilibration water. The peristaltic pump provided a constant flow of the equilibration water (1.7 ml h−1) into the equilibration chamber. The temperature setpoint of the preheated oven was set to a constant 130°C, ensuring immediate evaporation of water after entering the equilibration chamber. The end of the outlet metal tube was inserted into a glass vessel and checked for vapor flow and condensation of the blown‐out vapor. After 2 hr of equilibration, the feeding capillary was switched to a capillary delivering dry nitrogen gas (N2 5.0, PanGas AG, Dagmersellen, Switzerland, Prod No. 2220912) with a pressure of one bar for 2 hr to ensure complete removal of gaseous water in the chamber, which was still kept at 130°C. The duration of equilibration and drying, as well as the equilibration temperature, were step‐wise tested for cellulose to ensure maximum equilibration and no residual vapor. However, the high equilibration temperature of 130°C might be important to break down the crystalline structure of sugars and gelatinize starch to enable the access of water vapor (Gudasz, Soto, Sparrman, & Karlsson, 2020). For testing the reproducibility of the adapted method, triplicates of each type of cellulose and sugar samples were equilibrated independently on separate days following a standardized sample sequence (Appendix 7), in total three times with Water 1 (δ2H = −160‰) and three times with Water 2 (δ2H = −428‰). For starch and digested starch, triplicates were equilibrated only once with Water 1 and once with Water 2.

Subsequently, all samples (still hot) were immediately transferred into a Zero Blank Autosampler (N.C. Technologies S.r.l.), which was installed on a sample port of a high‐temperature elemental analyser system. The latter was coupled via a ConFlo III interface to a DeltaPlus XP IRMS (TC/EA‐IRMS, Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany). It is crucial to transfer the samples as fast as possible and still hot from the equilibration chamber to the autosampler to avoid any isotopic re‐equilibration of the sample with air moisture and water absorption. The autosampler carousel was evacuated to 0.01 mbar and afterwards filled with dry helium gas to 1.5 bar to avoid any contact with ambient water (vapor). The samples were pyrolysed in a reactor according to Gehre, Geilmann, Richter, Werner, and Brand (2004), and carried in a flow of dry helium (150 ml min−1) to the IRMS. Raw δ2H values of standard material (Table 1) were offset corrected using PEF standards (SD of PEF < 0.7‰ within one run).

Leaf sugar, starch and cellulose samples of three biological replicates were prepared as described above for the commercial standard material and equilibrated using identical settings. This corresponded to one equilibration with Water 1 and one with Water 2. Raw δ2H values of plant‐derived compounds were offset corrected using PEF. The calculated δ2Hne of plant extracted sugar and sugar derived from starch (Table 2) were normalized against the δ2Hne of Finnish, Russian and Merck sucrose from the method implementation (Table 1), while the calculated δ2Hne of plant extracted cellulose were normalized against the δ2H values of the corresponding nitrocellulose of cellulose from spruce, Spain and Siberia.

Table 2.

δ2Hne values of plant‐derived sugar, starch and cellulose from leaf material

| δ2Hne Starch [‰] | δ2Hne Sugar [‰] | δ2Hne Cellulose [‰] | Difference in δ2Hne [‰] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Cell‐starch | Sugar‐starch | Cell‐sugar | |

| C 3 | Cannabis sativa | −125.0 | 27.1 | −99.4 | 15.9 | −56.1 | 6.4 | 68.9 | 25.6 | 43.3 |

| Solanum cheesmaniae | −147.0 | 17.2 | −99.4 | 6.9 | −78.4 | 6.1 | 68.6 | 47.6 | 21 | |

| Salvia hispanica | −133.9 | 23.3 | −75.9 | 9.1 | −50.0 | 18.1 | 83.8 | 58.0 | 25.8 | |

| Abelmoschus esculentus | −126.1 | 12.3 | −110.5 | 7.3 | −63.4 | 10.6 | 62.7 | 15.5 | 47.1 | |

| Hordeum vulgare | −76.7 a | a | −74.8 | 5.1 | −59.0 | 4.9 | 17.7 | 1.9 | 15.8 | |

| mean | −121.7 | 20.0 | −92.0 | 8.9 | −61.4 | 9.2 | 60.3 | 29.7 | 30.6 | |

| C 4 | Zea mays | −60.6 a | a | −44.8 | 2.6 | −7.7 | 9.3 | 52.9 | 15.8 | 37.1 |

| Sorghum bicolor | −61.2 a | a | −20.2 | 3.7 | −25.3 | 6.7 | 35.9 | 41.0 | −5.1 | |

| mean | −60.9 | a | −32.5 | 3.2 | −16.5 | 8.0 | 44.4 | 28.4 | 16.0 | |

| CAM | Portulaca grandiflora | −24.8 | 33.7 | −12.8 | 15.1 | 14.9 | 5.7 | 39.7 | 11.9 | 27.7 |

| Kalanchoe daigremontiana | −18.0 | 2.3 | −13.2 | 3.6 | −5.6 | 5.3 | 12.4 | 4.8 | 7.6 | |

| Phalaenopsis | 12.1 a | a | 44.2 | 2.2 | 23.3 | 1.2 | 11.2 | 32.1 | −20.9 | |

| mean | −10.2 | 18.0 | 6.0 | 6.9 | 10.9 | 4.0 | 21.1 | 16.3 | 4.8 | |

Note: Plant species differing in photosynthetic pathways were grown under the same controlled conditions.

Due to low yields, starch samples of three replicates were pooled for H. vulgare, Z. mays, S. bicolor and Phalaenopsis, and thus could be only measured once.

2.6. Calculation of non‐exchangeable hydrogen isotope ratio (δ2Hne )

According to Filot et al. (2006), the %‐proportion of exchanged hydrogen during the equilibrations [xe, Equation (2)] can be calculated as:

| (2) |

where δ2He1 and δ2He2 are the δ2H values of the two equilibrated samples, δ2Hw1 and δ2Hw2 are the δ2H values of the two waters used, αe‐w is the fractionation factor of 1.082 for cellulose (Filot et al., 2006). While αe‐w needs to be adapted for different compounds and fractions with different functional groups (Schimmelmann, 1991), we consider αe‐w of cellulose to be transferable to other carbohydrates as they all have the exchangeable hydrogen on hydroxyl groups. The fractionation factor we use in our method lies also within the range proposed in other studies (Schimmelmann, Lewan, & Wintsch, 1999; Wassenaar & Hobson, 2000).

δ2Hne can then be calculated with Equation (3) using one of the two equilibrations (in this example equilibration with Water 1 [δ2He1 and δ2Hw1]):

| (3) |

Statistical analyses (one‐way ANOVA and Tukey posthoc test) were performed using R version 3.6.3 (R.Core.Team, 2021).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. A hot water vapor equilibration method for determining δ2Hne of sugar, starch and cellulose

Our in‐house implementation of the hot water vapor equilibration method for cellulose resulted in precise and accurate measurements of δ2Hne values of cellulose (Table 1). δ2Hne values of cellulose, ranging from −44.5 to −70.0‰, were measured with high precision as indicated by the standard deviations (SDe1 and SDe2) ranging between 0.9‰ and 4.1‰ for both equilibration waters. In addition, high accuracy was found, as indicated by a deviation of −1.0 to +5.7‰ between the δ2Hne value of the hot water vapor equilibration and the δ2H value of the corresponding cellulose nitrate (δ2Hne‐ δ2Hnitro), except for two of the commercial cellulose samples from Fluka and Wei Ming, with a deviation of −18.8 and +7.7‰, respectively. For the samples with high accuracy, the calculated xe ranged between 19.3 and 22.1% compared to a theoretical xe.pot of 30%. These xe values are comparable to those 20.5 ± 0.1% observed in the original implementation of the hot water vapor equilibration for cellulose (Sauer et al., 2009). For the two samples with low accuracy, xe reached only 16.4%. The reason for the low xe and the resulting low accuracy of the commercial cellulose from Fluka and the Wei Ming remains elusive. Tentatively, it could be explained by a different extraction method and purification of these cellulose samples, leading to different nanostructures (Jungnikl, Paris, Fratzl, & Burgert, 2007) or particle sizes, which in turn leads to different accessibility of water vapor to the cellulose molecule (Chami Khazraji & Robert, 2013). Nevertheless, the results show that the hot water vapor equilibration is suitable to determine δ2Hne with high accuracy and precision if the principle of identical treatment (Werner & Brand, 2001) is applied, that is, all samples are prepared and measured in the same way. Besides, the calculated xe values of the IAEA‐CH‐7 reference material without any Hex were close to 0 throughout all measurements, denoting the absence of absorbed water on the surface of each compound, as well as the analytical reproducibility for all δ2Hne values of cellulose, was high as indicated by a standard deviation of 0.8 to 1.9‰ for three repetitions.

The same method was also applied to analyse δ2Hne of NSC (Table 1). δ2Hne values of sugars of different classes, ranging from 6.4 to −157.8‰, were also measured with high precision as indicated by an SD ranging between 1.3 and 7.7‰ for both equilibration waters, which is comparable to the precision of derivatization methods (Dunbar & Schmidt, 1984: 1.9‰; Augusti et al., 2008: 2 and 10‰; Abrahim et al., 2020: 0.4 and 3.6‰). As no nitrated sugars were available due to the safety problems with sugar nitration, we could not calculate the accuracy. We, however, can assume that the accuracies for sugars should be in a comparable range as those derived from digested starch (−8.0 and −2.0‰). The reproducibility of the results for all tested commercial sugars ranged between 4.0 and 8.6‰ for three repetitions. The xe of the different sugars ranged between 34.1 and 53.5% and was thus similar or very close to xe.pot, which gives further confidence in the reliability of the method for sugars. The smaller deviation of xe from xe.pot for sugars than for cellulose might be explained by the dissolution of the sugars during the hot water vapor equilibration, leading to a breakdown of the crystal structure of the sugars. This might have facilitated a complete exchange of Hex with the water vapor in sugars, that is, not feasible for cellulose (Sauer et al., 2009; Schimmelmann, 1991).

The δ2Hne of equilibrated but undigested starch was close to the δ2Hne of the nitrated starch, measured with a precision ranging between 0.2 to 4.5‰ and accuracy between −3.1 and +5.3‰. The xe of the undigested starch was between 17.8 and 23.0%, and thus comparable to the results derived from cellulose. For digested starch, the precision ranged from 0.3 to 3.7‰ and the accuracy between −2.0 and −8.0‰. The xe of the digested starch ranged between 31.5 and 32.0% and was thus lower than the measured xe (38.7%) and xe.pot of pure glucose (41.7%). This lower xe of starch‐derived sugar compared to glucose could be explained by incomplete digestion of the starch to glucose monomers, leading to a mixture of mono‐ and oligosaccharides.

Overall, our results show that sugars of different classes, as well as sugar derived from digested starch, can be measured with high precision, accuracy and reproducibility. On a daily routine, we were able to measure up to 66 NSC samples and 32 standards. This proves that a method is now a reliable tool that enables high‐throughput analysis of δ2Hne of NSC in plants or in other environmental or biological samples.

3.2. Application of the method for analysis of δ2Hne in plant‐derived compounds

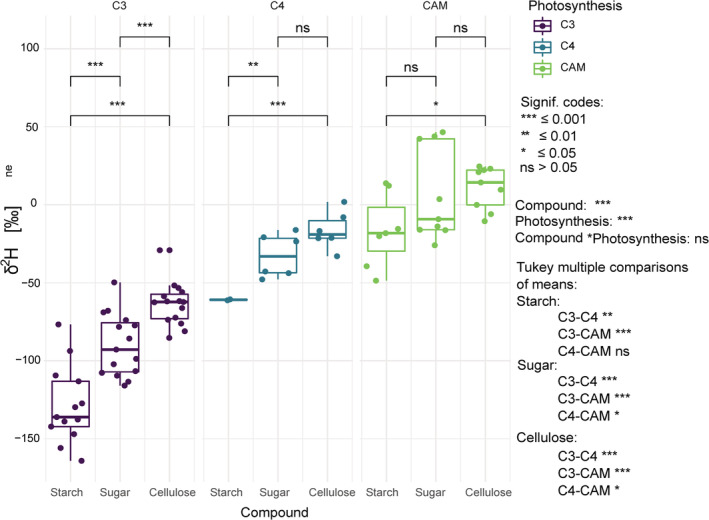

The analyses of non‐exchangeable hydrogen in sugar, starch and cellulose extracted from leaves of the plants grown in a climate chamber under controlled conditions showed strong differences (Figure 1, Table 2). Generally, among all the plant species and photosynthesis pathway types, starch was the most 2H‐depleted compound, followed by sugar, while cellulose was the most 2H‐enriched compound. In C3 plants, all compounds were significantly different from each other and showed the strongest 2H‐depletion of all photosynthetic types, with a mean δ2Hne of −121.7‰ for starch, −92.0‰ for sugar and −61.4‰ for cellulose. In C4 plants, mean δ2Hne values of −60.9‰ for starch were significantly lower compared to those of −32.5‰ and −16.5‰ for sugar and cellulose and thus reflect intermediate δ2Hne values compared to C3 and CAM plants. In CAM plants, only δ2Hne values of starch and cellulose differed significantly and showed the strongest 2H‐enrichment of all photosynthetic types, with a mean δ2Hne of −10.2‰ for starch, 6.0‰ for sugar and 10.9‰ for cellulose. The comparison of the δ2Hne of the same compound between the photosynthetic types resulted in significant differences between C3 and C4 and between C3 and CAM plants. The difference in sugar and cellulose between C4 and CAM plants was only slightly significant and not significant for starch. Our results go along with studies on δ2Hne values of organic matter and cellulose, showing also a 2H‐enrichment in C4 and CAM plants compared to C3 plants (Leaney, Osmond, Allison, & Ziegler, 1985; Sternberg, Deniro, & Ajie, 1984). While the observed variation in δ2Hne of NSC and cellulose among the photosynthetic pathways are unlikely to be explained solely by differences in leaf water 2H enrichment (Kahmen, Schefuß, & Sachse, 2013; Leaney et al., 1985), higher leaf water δ2H values might partially contribute to higher δ2Hne of NSC and cellulose in CAM plants compared to C3 plants (Smith & Ziegler, 1990). Thus, δ2H measurement of leaf water would be important to disentangle the photosynthetic 2H‐fractionation from leaf water to leaf NSC and cellulose within and between the photosynthetic types. However, δ2Hne difference among photosynthetic pathways and compounds are likely explained by 2H‐fractionations in biochemical pathways, including the usage of cytoplasm derived malate as a proton source and glucose precursor in CAM and C4 plants (Yamori, Hikosaka, & Way, 2014; Zhou et al., 2018), which might overlay the signal of the strongly 2H‐depleted NADPH produced via photosystem II (Luo, Steinberg, Suda, Kumazawa, & Mitsui, 1991). In summary, the analyses of δ2Hne in sugars, starch and cellulose might be used to generally distinguish plants with C3, C4 and CAM photosynthesis.

Figure 1.

Comparison of δ2Hne between starch, sugar and cellulose of leaves within and between the three photosynthesis types. The boxplots show the estimated significance levels using a linear model comparing the compounds within the photosynthesis types. On the low‐right side, the significant levels of a Tukey posthoc test comparing the photosynthesis types for all three compounds are given [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Above that, δ2Hne values in CAM plants may indicate if a facultative CAM plant performs C3 or C4 photosynthesis in the absence of water stress (Guralnick, Gilbert, Denio, & Antico, 2020; Winter, Garcia, & Holtum, 2008). The higher the contribution of C3 or C4 photosynthesis to a CAM plant's total carbon dioxide fixation, the more depleted are the δ2Hne values of cellulose and NSC (Luo & Sternberg, 1991; Sternberg, Deniro, & Johnson, 1984), thus indicating the absence of water stress. Among all the tested plant species, the orchid Phalaenopsis was the only species with a positive δ2Hne value in all compounds, and thus likely the only species with no or only a negligible amount of C3 photosynthesis in mature leaves. However, the observation that Phalaenopsis sugars are more 2H‐enriched than cellulose in mature leaves could be explained by the presence of C3 photosynthesis in the developing leaves (Guo & Lee, 2006), leading to 2H‐depleted cellulose during leaf formation. For the other two CAM species, the C3 or C4 photosynthesis contributed a higher fraction to the total carbon dioxide fixation due to the absence of water limitation and thus had lower δ2Hne values for NSC and cellulose.

The generally lower δ2Hne values of NSC compared to cellulose (Table 2) can be explained by the 2H‐depletion during photosystem II NADPH formation and the subsequent transfer of the 2H‐depleted H during the reduction of glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate, continuous enzymatic H‐exchange between carbohydrates and water and kinetic isotope effects during metabolic processes (Cormier et al., 2018; Cormier, Werner, Leuenberger, & Kahmen, 2019). Our results are supported by a previous study (Luo & Sternberg, 1991; Schleucher et al., 1999), showing that nitrated starch was more 2H‐depleted than nitrated cellulose within the same autotrophic photosynthetic tissue, which can be interpreted as another proof for the reliability of the new method for δ2Hne values of NSC. The high variability in 2H‐fractionation in the sequence from sugars to starch to cellulose (Table 2) between all tested species indicates high variability in common 2H‐fractionation processes, which is also supported by recent studies (Cormier et al., 2018; Sanchez‐Bragado et al., 2019). Thus, the variability in 2H‐fractionation may find application in future plant physiological studies, investigating stress responses or short‐ and long‐term carbon dynamics. We assume that δ2Hne of NSC are susceptible to diel or seasonal changes in environmental conditions such as temperature and light intensity due to their short turnover time (Fernandez et al., 2017; Gibon et al., 2004). The variability in 2H‐fractionation between different species might also be important if multiple tree species are used during the establishment of tree‐ring isotope chronologies in dendroclimatological studies (Arosio, Ziehmer‐Wenz, Nicolussi, Schlüchter, & Leuenberger, 2020).

In conclusion, we show that a hot water vapor equilibration method originally developed for cellulose can be adapted for accurate, precise and reproducible analyses of δ2Hne in non‐structural carbohydrates (NSC) such as sugar and starch. By applying the method for compounds from different plant species, we demonstrated that this analytical method can now be used to estimate 2H‐fractionation among structural and NSC and to distinguish plant material from plants with different photosynthetic pathways. It should be noted that the method presented herein enables analysis of δ2Hne of bulk sugar and sugar derived from digested starch and is therefore not compound‐specific nor position‐specific. Yet, our δ2Hne method allows us to measure NSC samples in high‐throughput and we thus expect that it will help to identify important 2H‐fractionation processes. These findings could then eventually be studied in more detail with compound‐specific methods (GC‐IRMS [Abrahim et al., 2020]) or methods giving positional information (NMR [Ehlers et al., 2015]). We therefore expect that the method will find widespread applications in plant physiological, hydrological, ecological and agricultural research to study NSC fluxes and plant performance, and the beverage and food industry, to distinguish between sugars of different origins, which could be applied to check if a certain product is altered by the addition of low‐cost supplements. We also expect that the method can help to improve mechanistic models for 2H distributions in organic material (Roden, Lin, & Ehleringer, 2000; Yakir & DeNiro, 1990). The method may further help, in combination with other hydrogen isotope proxies (e.g., fatty acids, n‐alkanes or lignin methoxy groups), researchers to better understand metabolic pathways and fluxes, shaping the hydrogen isotopic composition of plant material.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting Information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Patrick Flütsch at ETH Zurich for technical support, as well as Manuela Laski, Manuela Oettli, Oliver Rehmann and Neptun at WSL Birmensdorf for laboratory assistance. Our work was supported by the innovative project ‘HDoor2020’ at WSL, by the SNF Ambizione project ‘TreeCarbo’ (No. 179978, granted to M.M.L.), the SNF‐project ‘Isodrought’ (No. 182092, granted to MS), and by funding from the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (received by M.‐A.C). Open access funding provided by Lib4RI Library for the Research Institutes within the ETH Domain Eawag Empa PSI and WSL.

Schuler, P. , Cormier, M.‐A. , Werner, R. A. , Buchmann, N. , Gessler, A. , Vitali, V. , Saurer, M. , & Lehmann, M. M. (2022). A high‐temperature water vapor equilibration method to determine non‐exchangeable hydrogen isotope ratios of sugar, starch and cellulose. Plant, Cell & Environment, 45, 12–22. 10.1111/pce.14193

Funding informationOur work was supported by the innovative project ‘HDoor2020’ at WSL, by the SNF Ambizione project ‘TreeCarbo’ (No. 179978, granted to M.M.L.), and the SNF‐project ‘Isodrought’ (No. 182092, granted to MS). M.‐A.C. received funding from the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

Funding information Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council; Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung, Grant/Award Numbers: SNF Ambizione project “TreeCarbo” (No. 179978), SNF‐project "Isodrought" (No. 182092)

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Abrahim, A. , Cannavan, A. , & Kelly, S. D. (2020). Stable isotope analysis of non‐exchangeable hydrogen in carbohydrates derivatised with N‐methyl‐bis‐trifluoroacetamide by gas chromatography–Chromium silver reduction/High temperature Conversion‐isotope ratio mass spectrometry (GC‐CrAg/HTC‐IRMS). Food Chemistry, 318, 126413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, W. , & Mitchell, R. (1949). Rapid measurement of cellulose viscosity by nitration methods. Analytical Chemistry, 21(12), 1497–1500. [Google Scholar]

- An, W. , Liu, X. , Leavitt, S. W. , Xu, G. , Zeng, X. , Wang, W. , … Ren, J. (2014). Relative humidity history on the Batang–Litang Plateau of western China since 1755 reconstructed from tree‐ring δ18O and δD. Climate Dynamics, 42, 2639–2654. [Google Scholar]

- Anhäuser, T. , Hook, B. A. , Halfar, J. , Greule, M. , & Keppler, F. (2018). Earliest Eocene cold period and polar amplification‐Insights from δ2H values of lignin methoxyl groups of mummified wood. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 505, 326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Arosio, T. , Ziehmer, M. M. , Nicolussi, K. , Schlüchter, C. , & Leuenberger, M. (2020). Alpine Holocene tree‐ring dataset: Age‐related trends in the stable isotopes of cellulose show species‐specific patterns. Biogeosciences, 17(19), 4871–4882. [Google Scholar]

- Arosio, T. , Ziehmer‐Wenz, M. , Nicolussi, K. , Schlüchter, C. , & Leuenberger, M. (2020). Larch cellulose shows significantly depleted hydrogen isotope values with respect to evergreen conifers in contrast to oxygen and carbon isotopes. Frontiers in Earth Science, 8(579), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Augusti, A. , Betson, T. R. , & Schleucher, J. (2008). Deriving correlated climate and physiological signals from deuterium isotopomers in tree rings. Chemical Geology, 252(1‐2), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Boettger, T. , Haupt, M. , Knöller, K. , Weise, S. M. , Waterhouse, J. S. , Rinne, K. T. , … Schleser, G. H. (2007). Wood cellulose preparation methods and mass spectrometric analyses of δ13C, δ18O, and nonexchangeable δ2H values in cellulose, sugar, and starch: An interlaboratory comparison. Analytical Chemistry, 79(12), 4603–4612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak, L. A. , Barbour, M. M. , Arndt, S. K. , Cheesman, A. W. , English, N. B. , Feild, T. S. , … Farquhar, G. D. (2016). Stable isotopes in leaf water of terrestrial plants. Plant, Cell & Environment, 39(5), 1087–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chami Khazraji, A. , & Robert, S. (2013). Interaction effects between cellulose and water in nanocrystalline and amorphous regions: A novel approach using molecular modeling. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2013, 409676. [Google Scholar]

- Coplen, T. B. (2011). Guidelines and recommended terms for expression of stable‐isotope‐ratio and gas‐ratio measurement results. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 25(17), 2538–2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier, M.‐A. , Werner, R. A. , Leuenberger, M. C. , & Kahmen, A. (2019). 2H‐enrichment of cellulose and n‐alkanes in heterotrophic plants. Oecologia, 189(2), 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier, M.‐A. , Werner, R. A. , Sauer, P. E. , Gröcke, D. R. , Leuenberger, M. C. , Wieloch, T. , … Kahmen, A. (2018). 2H‐fractionations during the biosynthesis of carbohydrates and lipids imprint a metabolic signal on the δ2H values of plant organic compounds. New Phytologist, 218(2), 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNiro, M. J. (1981). The effects of different methods of preparing cellulose nitrate on the determination of the D/H ratios of non‐exchangeable hydrogen of cellulose. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 54(2), 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, J. , & Schmidt, H.‐L. (1984). Measurement of the 2H/1H ratios of the carbon bound hydrogen atoms in sugars. Fresenius' Zeitschrift für Analytische Chemie, 317(8), 853–857. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, J. , & Wilson, A. (1983). Oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in fruit and vegetable juices. Plant Physiology, 72(3), 725–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, I. , Augusti, A. , Betson, T. R. , Nilsson, M. B. , Marshall, J. D. , & Schleucher, J. (2015). Detecting long‐term metabolic shifts using isotopomers: CO2‐driven suppression of photorespiration in C3 plants over the 20th century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(51), 15585–15590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, S. , Yapp, C. J. , & Hall, J. H. (1976). The determination of the D/H ratio of non‐exchangeable hydrogen in cellulose extracted from aquatic and land plants. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 30(2), 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Estep, M. F. , & Hoering, T. C. (1981). Stable hydrogen isotope fractionations during autotrophic and mixotrophic growth of microalgae. Plant Physiology, 67(3), 474–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, O. , Ishihara, H. , George, G. M. , Mengin, V. , Flis, A. , Sumner, D. , … Stitt, M. (2017). Leaf starch turnover occurs in long days and in falling light at the end of the day. Plant Physiology, 174(4), 2199–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filot, M. S. , Leuenberger, M. , Pazdur, A. , & Boettger, T. (2006). Rapid online equilibration method to determine the D/H ratios of non‐exchangeable hydrogen in cellulose. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 20(22), 3337–3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaglioti, B. V. , Mann, D. H. , Wooller, M. J. , Jones, B. M. , Wiles, G. C. , Groves, P. , … Reanier, R. E. (2017). Younger‐Dryas cooling and sea‐ice feedbacks were prominent features of the Pleistocene‐Holocene transition in Arctic Alaska. Quaternary Science Reviews, 169, 330–343. [Google Scholar]

- Gamarra, B. , & Kahmen, A. (2015). Concentrations and δ2H values of cuticular n‐alkanes vary significantly among plant organs, species and habitats in grasses from an alpine and a temperate European grassland. Oecologia, 178(4), 981–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehre, M. , Geilmann, H. , Richter, J. , Werner, R. , & Brand, W. (2004). Continuous flow 2H/1H and 18O/16O analysis of water samples with dual inlet precision. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 18(22), 2650–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehre, M. , Renpenning, J. , Gilevska, T. , Qi, H. , Coplen, T. , Meijer, H. , … Schimmelmann, A. (2015). On‐line hydrogen‐isotope measurements of organic samples using elemental chromium: An extension for high temperature elemental‐analyzer techniques. Analytical Chemistry, 87(10), 5198–5205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessler, A. , Ferrio, J. P. , Hommel, R. , Treydte, K. , Werner, R. A. , & Monson, R. K. (2014). Stable isotopes in tree rings: Towards a mechanistic understanding of isotope fractionation and mixing processes from the leaves to the wood. Tree Physiology, 34(8), 796–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon, Y. , Bläsing, O. E. , Palacios‐Rojas, N. , Pankovic, D. , Hendriks, J. H. , Fisahn, J. , … Stitt, M. (2004). Adjustment of diurnal starch turnover to short days: Depletion of sugar during the night leads to a temporary inhibition of carbohydrate utilization, accumulation of sugars and post‐translational activation of ADP‐glucose pyrophosphorylase in the following light period. The Plant Journal, 39(6), 847–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudasz, C. , Soto, D. X. , Sparrman, T. , & Karlsson, J. (2020). A novel method to quantify exchangeable hydrogen fraction in organic matter. Paper presented at the EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts.

- Guo, W.‐J. , & Lee, N. (2006). Effect of leaf and plant age, and day/night temperature on net CO2 uptake in Phalaenopsis amabilis var. formosa. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 131(3), 320–326. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick, L. J. , Gilbert, K. E. , Denio, D. , & Antico, N. (2020). The development of crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) photosynthesis in cotyledons of the C4 species, Portulaca grandiflora (Portulacaceae). Plants, 9(1), 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepp, J. , Glaser, B. , Juchelka, D. , Mayr, C. , Rozanski, K. , Schäfer, I. K. , … Zech, M. (2019). Validation of a coupled δ2H n‐alkane‐δ18O sugar paleohygrometer approach based on a climate chamber experiment. Biogeosciences Discussions, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hepp, J. , Tuthorn, M. , Zech, R. , Mügler, I. , Schlütz, F. , Zech, W. , & Zech, M. (2015). Reconstructing lake evaporation history and the isotopic composition of precipitation by a coupled δ18O–δ2H biomarker approach. Journal of Hydrology, 529, 622–631. [Google Scholar]

- Jungnikl, K. , Paris, O. , Fratzl, P. , & Burgert, I. (2007). The implication of chemical extraction treatments on the cell wall nanostructure of softwood. Cellulose, 15(3), 407. [Google Scholar]

- Kahmen, A. , Schefuß, E. , & Sachse, D. (2013). Leaf water deuterium enrichment shapes leaf wax n‐alkane δD values of angiosperm plants I: Experimental evidence and mechanistic insights. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 111, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Leaney, F. , Osmond, C. , Allison, G. , & Ziegler, H. (1985). Hydrogen‐isotope composition of leaf water in C3 and C4 plants: Its relationship to the hydrogen‐isotope composition of dry matter. Planta, 164(2), 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, M. M. , Egli, M. , Brinkmann, N. , Werner, R. A. , Saurer, M. , & Kahmen, A. (2020). Improving the extraction and purification of leaf and phloem sugars for oxygen isotope analyses. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 34(19), e8854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, M. M. , Vitali, V. , Schuler, P. , Leuenberger, M. , & Saurer, M. (2021). More than climate: Hydrogen isotope ratios in tree rings as novel plant physiological indicator for stress conditions. Dendrochronologia, 65, 125788. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.‐H. , Steinberg, L. , Suda, S. , Kumazawa, S. , & Mitsui, A. (1991). Extremely low D/H ratios of photoproduced hydrogen by cyanobacteria. Plant and Cell Physiology, 32(6), 897–900. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.‐H. , & Sternberg, L. (1991). Deuterium heterogeneity in starch and cellulose nitrate of CAM and C3 plants. Phytochemistry, 30(4), 1095–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Manrique‐Alba, À. , Beguería, S. , Molina, A. J. , González‐Sanchis, M. , Tomàs‐Burguera, M. , del Campo, A. D. , … Camarero, J. J. (2020). Long‐term thinning effects on tree growth, drought response and water use efficiency at two Aleppo pine plantations in Spain. Science of the Total Environment, 728, 138536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarroll, D. , & Loader, N. J. (2004). Stable isotopes in tree rings. Quaternary Science Reviews, 23(7‐8), 771–801. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel, M. , Esper, J. , Keppler, F. , Greule, M. , & Werner, W. (2015). δ2H, δ13C and δ18O from whole wood, α‐cellulose and lignin methoxyl groups in Pinus sylvestris: A multi‐parameter approach. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies, 51(4), 553–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka, T. , Sano, M. , Li, Z. , Xu, C. , Tsushima, A. , Shigeoka, Y. , … Mitsutani, T. (2020). A 2600‐year summer climate reconstruction in central Japan by integrating tree‐ring stable oxygen and hydrogen isotopes. Climate of the Past, 16(6), 2153–2172. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, T. J. , Pisaric, M. F. , Field, R. D. , Kokelj, S. V. , Edwards, T. W. , de Montigny, P. , … LeGrande, A. N. (2014). Spring‐summer temperatures since AD 1780 reconstructed from stable oxygen isotope ratios in white spruce tree‐rings from the Mackenzie Delta, northwestern Canada. Climate Dynamics, 42(3‐4), 771–785. [Google Scholar]

- R.Core.Team . (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Richter, A. , Wanek, W. , Werner, R. A. , Ghashghaie, J. , Jäggi, M. , Gessler, A. , … Gleixner, G. (2009). Preparation of starch and soluble sugars of plant material for the analysis of carbon isotope composition: A comparison of methods. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry: An International Journal Devoted to the Rapid Dissemination of Up‐to‐the‐Minute Research in Mass Spectrometry, 23(16), 2476–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne, K. T. , Saurer, M. , Streit, K. , & Siegwolf, R. T. (2012). Evaluation of a liquid chromatography method for compound‐specific δ13C analysis of plant carbohydrates in alkaline media. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 26(18), 2173–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden, J. S. , Lin, G. , & Ehleringer, J. R. (2000). A mechanistic model for interpretation of hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios in tree‐ring cellulose. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 64(1), 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sachse, D. , Billault, I. , Bowen, G. J. , Chikaraishi, Y. , Dawson, T. E. , Feakins, S. J. , … Kahmen, A. (2012). Molecular paleohydrology: Interpreting the hydrogen‐isotopic composition of lipid biomarkers from photosynthesizing organisms. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 40, 221–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez‐Bragado, R. , Serret, M. D. , Marimon, R. M. , Bort, J. , & Araus, J. L. (2019). The hydrogen isotope composition δ2H reflects plant performance. Plant Physiology, 180(2), 793–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sass‐Klaassen, U. , Poole, I. , Wils, T. , Helle, G. , Schleser, G. , & Van Bergen, P. (2005). Carbon and oxygen isotope dendrochronology in sub‐fossil bog oak tree rings‐a preliminary study. IAWA Journal, 26(1), 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, P. E. , Schimmelmann, A. , Sessions, A. L. , & Topalov, K. (2009). Simplified batch equilibration for D/H determination of non‐exchangeable hydrogen in solid organic material. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry: An International Journal Devoted to the Rapid Dissemination of Up‐to‐the‐Minute Research in Mass Spectrometry, 23(7), 949–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurer, M. , Borella, S. , & Leuenberger, M. (1997). δ18O of tree rings of beech (Fagus silvatica) as a record of δ18O of the growing season precipitation. Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology, 49(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Saurer, M. , Kress, A. , Leuenberger, M. , Rinne, K. T. , Treydte, K. S. , & Siegwolf, R. T. (2012). Influence of atmospheric circulation patterns on the oxygen isotope ratio of tree rings in the Alpine region. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 117(D5), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmelmann, A. (1991). Determination of the concentration and stable isotopic composition of nonexchangeable hydrogen in organic matter. Analytical Chemistry, 63(21), 2456–2459. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmelmann, A. , Deniro, M. J. , Poulicek, M. , Voss‐Foucart, M.‐F. , Goffinet, G. , & Jeuniaux, C. (1986). Stable isotopic composition of chitin from arthropods recovered in archaeological contexts as palaeoenvironmental indicators. Journal of Archaeological Science, 13(6), 553–566. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmelmann, A. , Lewan, M. D. , & Wintsch, R. P. (1999). D/H isotope ratios of kerogen, bitumen, oil, and water in hydrous pyrolysis of source rocks containing kerogen types I, II, IIS, and III. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 63(22), 3751–3766. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmelmann, A. , Qi, H. , Coplen, T. B. , Brand, W. A. , Fong, J. , Meier‐Augenstein, W. , … Werner, R. A. (2016). Organic reference materials for hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen stable isotope‐ratio measurements: Caffeines, n‐alkanes, fatty acid methyl esters, glycines, l‐valines, polyethylenes, and oils. Analytical Chemistry, 88(8), 4294–4302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleucher, J. , Vanderveer, P. , Markley, J. L. , & Sharkey, T. D. (1999). Intramolecular deuterium distributions reveal disequilibrium of chloroplast phosphoglucose isomerase. Plant, Cell & Environment, 22(5), 525–533. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H.‐L. , Werner, R. A. , & Eisenreich, W. (2003). Systematics of 2H patterns in natural compounds and its importance for the elucidation of biosynthetic pathways. Phytochemistry Reviews, 2(1), 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. , & Ziegler, H. (1990). Isotopic fractionation of hydrogen in plants. Botanica Acta, 103(4), 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, L. , Deniro, M. , & Johnson, H. (1984). Isotope ratios of cellulose from plants having different photosynthetic pathways. Plant Physiology, 74(3), 557–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, L. , Deniro, M. J. , & Ajie, H. (1984). Stable hydrogen isotope ratios of saponifiable lipids and cellulose nitrate from CAM, C3 and C4 plants. Phytochemistry, 23(11), 2475–2477. [Google Scholar]

- Tipple, B. J. , & Ehleringer, J. R. (2018). Distinctions in heterotrophic and autotrophic‐based metabolism as recorded in the hydrogen and carbon isotope ratios of normal alkanes. Oecologia, 187(4), 1053–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanek, W. , Heintel, S. , & Richter, A. (2001). Preparation of starch and other carbon fractions from higher plant leaves for stable carbon isotope analysis. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 15(14), 1136–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenaar, L. I. , & Hobson, K. A. (2000). Improved method for determining the stable‐hydrogen isotopic composition (δD) of complex organic materials of environmental interest. Environmental Science & Technology, 34(11), 2354–2360. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, R. A. , & Brand, W. A. (2001). Referencing strategies and techniques in stable isotope ratio analysis. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 15(7), 501–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West, A. G. , Patrickson, S. J. , & Ehleringer, J. R. (2006). Water extraction times for plant and soil materials used in stable isotope analysis. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry: An International Journal Devoted to the Rapid Dissemination of Up‐to‐the‐Minute Research in Mass Spectrometry, 20(8), 1317–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter, K. , Garcia, M. , & Holtum, J. A. (2008). On the nature of facultative and constitutive CAM: Environmental and developmental control of CAM expression during early growth of Clusia, Kalanchoë, and Opuntia. Journal of Experimental Botany, 59(7), 1829–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z. , Zheng, Y. , Stelling, J. M. , Loisel, J. , Huang, Y. , & Yu, Z. (2020). Environmental controls on the carbon and water (H and O) isotopes in peatland Sphagnum mosses. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 277, 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Yakir, D. , & DeNiro, M. J. (1990). Oxygen and hydrogen isotope fractionation during cellulose metabolism in Lemna gibba L. Plant Physiology, 93(1), 325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori, W. , Hikosaka, K. , & Way, D. A. (2014). Temperature response of photosynthesis in C3, C4, and CAM plants: Temperature acclimation and temperature adaptation. Photosynthesis Research, 119(1‐2), 101–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B. L. , Quemerais, B. , Martin, M. L. , Martin, G. J. , & Williams, J. M. (1994). Determination of the natural deuterium distribution in glucose from plants having different photosynthetic pathways. Phytochemical Analysis, 5(3), 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. , Zhang, B. , Stuart‐Williams, H. , Grice, K. , Hocart, C. H. , Gessler, A. , … Farquhar, G. D. (2018). On the contributions of photorespiration and compartmentation to the contrasting intramolecular 2H profiles of C3 and C4 plant sugars. Phytochemistry, 145, 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z. , Yin, X. , Song, X. , Wang, B. , Ma, R. , Zhao, Y. , … Zhou, Y. (2020). Leaf transition from heterotrophy to autotrophy is recorded in the intraleaf C, H and O isotope patterns of leaf organic matter. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 34(19), e8840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting Information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.