Abstract

Social isolation has been linked to numerous health risks, including depression and mortality. Parents raising children in low‐income and under‐resourced communities are at an increased risk for experiencing social isolation and its negative effects. Social connectedness (SC), one's sense of belongingness and connection to other people, or a community, has been linked to reduced social isolation and improved health outcomes in the general population, yet little is known about the impact SC has on parents with low incomes. This integrative review aims to describe the current state of the science surrounding SC in parents with low incomes, summarize how SC is being defined and measured, evaluate the quality of the science, and identify gaps in the literature to guide future research. Five electronic databases were searched, yielding 15 articles for inclusion. Empirical studies meeting the following criteria were included: population focused on parents who have low incomes or live in low‐income communities and have dependent children, outcomes were parent‐centered, SC was a study variable or a qualitative finding, and publication date was before March 2021. Findings emphasize SC as a promising construct that may be protective in the health and well‐being of parents and children living in low‐income communities. However, a lack of consensus on definitions and measures of SC makes it difficult to build a strong science base for understanding these potential benefits. Future research should focus on understanding the mechanisms by which SC works to benefit parents and their children.

Keywords: belongingness, low‐income, parenting, social connectedness, social isolation

1. INTRODUCTION

Social isolation has been linked to numerous health risks, including increased depression and mortality (Hämmig, 2019; Holt‐Lunstad et al., 2015). The risks associated with social isolation have been compared to that of smoking and obesity (Pantell et al., 2013). Social isolation, and many of its associated health risks, disproportionately affect some populations over others, further contributing to health inequities. Parents raising children in low‐income, under‐resourced communities are at a heightened risk for experiencing social isolation and its effects due to limited access to resources that bridge and nurture their social connections (e.g., accessible transportation, safe neighborhoods) (Bess & Doykos, 2014; Keating‐Lefler et al., 2004; Rank et al., 1998). This is particularly concerning as social isolation among parents has been associated with a greater risk of child maltreatment (Gracia & Musitu, 2003) and increased health problems for both parents and their children (Thompson et al., 2020). In acknowledgment of this disparity, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine has made reducing social isolation a leading health indicator for improving social environments and closing the gaps in health equity by 2030 (National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine, 2020).

Social connectedness (SC) refers to a person's perception of belongingness and connection to other people, or a community (Haslam et al., 2015; Lee & Robbins, 1995), and has been linked to reduced social isolation and improved physical and mental health outcomes (Cohen, 2004). SC may be a modifiable factor that could potentially improve health outcomes in vulnerable populations through the optimization of interventions that foster a sense of belonging and connectedness (O'Rourke & Sidani, 2017). Although existing research has explored SC in populations such as older adults (Haslam et al., 2015; O'Rourke & Sidani, 2017) and individuals with mental health disorders (Hare Duke et al., 2019), little is known about SC and how it relates to health outcomes among low‐income families. Given that children's health and well‐being are integrally linked to their parents' health and well‐being (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2016), understanding the role of parents’ SC in supporting health outcomes across two generations is an important area of study.

1.1. SC versus social support

SC and social support are related, yet different constructs. Both focus on the qualities of people's relationships with others and have been associated with mental health outcomes (Ozbay et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2018). However, SC and social support are characterized by different aspects of social relationships. Specifically, social support refers to an exchange of resources (e.g., information or money) and has been characterized by four types of support: informational, emotional, instrumental, and appraisal (Mohd et al., 2019; Taylor, 2011). In contrast, SC refers to an individual's sense of belongingness in their relationships with other individuals and groups. These conceptual differences have important implications for how one might approach interventions designed to improve health outcomes by building social support systems versus building social connections within those systems.

The concept of social support has a significant presence in social science literature and its definition and measurement are well‐established (Taylor, 2011). There have been several reviews of the literature on social support and related health outcomes and readers are referred to these sources for more information (Lindsay Smith et al., 2017; Mohd et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018). In contrast, the concept of SC remains underdeveloped, despite increasing interest from health researchers (Holt‐Lunstad et al., 2017; O'Rourke & Sidani, 2017). For example, a 2019 National Institutes of Health funding announcement sought proposals to study mechanisms by which SC influences health, well‐being, and recovery from illness and vulnerable populations (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). The announcement highlighted the potential health benefits of SC as well as the dearth of research examining how SC is developed and its effects on health across the lifespan or generations. This review will focus specifically on this understudied concept of SC.

The purpose of this integrative review is to synthesize existing literature on SC among parents raising children in low‐income communities. Specifically, this review aims to: (a) describe the current state of the science surrounding SC in parents with low incomes, (b) summarize how SC is currently defined and measured, (c) evaluate the quality of the published research, and (d) identify gaps in the literature and recommendations for future research.

2. METHODS

2.1. Literature search strategy

Before conducting the search, a health science librarian was consulted in the development of the search strategy (Supporting Information Appendix 1). The search was conducted in March 2021 using five electronic databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, and Web of Science.

Search terms were established using a combination of medical subject headings (MeSH) and nonindexed terms. Given that SC is a developing concept, it is not an indexed term. Therefore, additional terms were chosen that reflected “a person's perceived sense of belonging to others or the environment” (Haslam et al., 2015) to maximize our ability to identify relevant articles. The following additional terms were included in the search: (a) social cohesion, the sense of belonging among groups in society and the extent of their connectedness (Manca, 2014); (b) group cohesion, the extent individuals in a cohesive group express their sense of belonging to the group (Dyaram & Kamalanabhan, 2005); and (c) social/group identity, individuals' perception of who they are based on groups in which they feel a sense of belonging to (Hogg et al., 2017). The phrase “sense of belonging” was also included to identify potential articles that discuss this concept without using an explicit term. As noted above, social support was excluded from the search to distinguish literature on exchangeable resources (e.g., information) gained through social relationships from a sense of belonging and connection with others.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if (a) the population of focus was parents of dependent children with low incomes or living in low‐income communities, (b) outcomes in the study were parent‐centered (i.e., study outcomes were focused on parents, not just children), (c) it was an empirical study, (d) the concept of SC (or related search term as described above) was a study variable or emerged in qualitative findings, and (e) the study was published in a peer‐reviewed journal before March 2021. Studies were excluded if (a) they were not published in English, (b) the sample consisted entirely of participants that did not have children at the time of the study (e.g., participants pregnant with their first child), or (c) the authors used a measure to assess SC that was specifically designed to evaluate a different term excluded from the search (e.g., studies using a social support measure to evaluate SC). Studies that focused on a population or community level of SC (e.g., overall neighborhood level of SC), rather than an individual's perception of SC (e.g., parent's perception of neighborhood SC), were also excluded.

2.3. Screening

Search results were uploaded to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, n.d.), a software designed to manage and organize literature for reviews. After removing duplicate results, two authors independently performed a title and abstract screening. Articles included after the initial screening were then independently evaluated in a full‐text review by the same two authors. If there was a disagreement in an article for inclusion, a third author read the article and acted as a “tie‐breaker” to determine the outcome.

2.4. Data evaluation

The following information was extracted from all studies (1) setting in which the research took place, (2) sample size and participant characteristics, (3) research design and methods, and (4) definition of SC or related term, when available. For quantitative studies, measures of SC and related health outcomes (if applicable) were extracted. For intervention studies, intervention programs, settings, programmatic factors, and major outcomes related to SC were extracted. For qualitative studies, text labeled as “results” in the study reports was considered as data for extraction (Thomas & Harden, 2008). In studies that collected SC data from multiple sources (e.g., parents, providers, children), only data from parents were included.

2.5. Quality assessment

Included articles were assessed for quality using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence‐Based Practice (JHNEBP) Evidence Level and Quality Guide (Dang & Dearholt, 2018). JHNEBP is a well‐established quality appraisal tool used to evaluate both qualitative and quantitative studies (Dang & Dearholt, 2018). Per the guide, articles were rated for their level of evidence on a scale from Level I (high evidence level, e.g., experimental studies, randomized controlled trials) to Level V (low evidence level, e.g., nonresearch design, case reports). Quality was then assessed using the guide's criteria of study sample size, recommendations, and generalizability of results with “A” indicating high quality, “B” good quality, and “C” low quality (Dang & Dearholt, 2018). Article quality was assessed independently by two authors. Ratings were then discussed to determine inter‐rater agreement. When a discrepancy occurred, the quality guide was referenced and a third author acted as a “tie‐breaker” until a consensus was reached. The included studies’ evidence and quality ratings are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies on social connectedness and related terms among parents with low‐incomes

| First author (year) | Setting | Sample (N) characteristics | Study methods | Guiding theory | Intervention | Quality appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies | ||||||

| Acri (2019) |

US Poverty‐impacted community |

N = 32 caregivers of children aged 7–11 91% female, 61% mothers 52% Black, 44% White, 67% non‐Hispanic/Latino, 30% household income <$10k/year Substudy of National Institute of Mental Health Study |

Cross‐sectional descriptive Self‐report |

None specified | 4Rs and 2Ss | Level IIIB |

| Adaji (2019) |

Nigeria Rural community |

N = 161 mothers in low‐income setting 16.3% pregnant for first time 53.5% had 1–4 children 30.2% had >5 children |

Prospective observational study Self‐report, group facilitator report, and objective measure |

None specified |

Prenatal care program based on centering pregnancy |

Level IIIB |

| Booth (2020) |

US Pittsburgh Urban |

N = 185 low‐income adolescent males and their parents Adolescents: 56.44% White, 34.67% Black, 8.89% mixed race Parents: 89.6%–93.5% mothers; 64.89% White, 34.22% African American, <1% mixed race |

Longitudinal descriptive study Secondary data from the Pitt Child & Mother Project Self‐report |

Social disorganized theory | N/A | Level IIIA |

| Brisson (2012) |

US Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio Urban |

N = 1495 low‐income mothers (20% poverty rate or more) 43% Black, 48% Hispanic, 8% White |

Longitudinal descriptive study Secondary data from welfare, children, and families: A Three‐cities study Self‐report |

None specified | N/A | Level IIIA |

| Brisson (2019) |

US Western United States Urban |

N = 52 families (37 intervention group, 15 nontreatment group) 96% female, 45% Latino, 22% Black, 14% White in 3 low‐income neighborhoods |

Quasi‐experimental study Self‐report |

Ecological system theory |

Your family, your neighborhood (YFYN) |

Level IIB |

| McCloskey (2019) |

US 20 large cities Urban |

N = 3876 low‐income mothers, 48% Black, 25.9% Hispanic, 22.5% White |

Cross‐sectional descriptive study secondary data from Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study Self‐report |

Pearlin's stress process model | N/A | Level IIIA |

| McLeigh (2018) |

US South Carolina |

N = 483 low‐income primary caregivers of children, 68.4% married, 12.8% separated/divorced 70.3% White, 23.6% Black, 3.7% Hispanic |

Cross‐sectional descriptive study Self‐report and objective data |

None specified | N/A | Level IIIA |

| Prendergast (2019) |

US 20 large cities Urban |

N =3529 children and their mothers |

Longitudinal descriptive study Secondary data from Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study Self‐report |

Social ecological model | N/A | Level IIIA |

| Yuma‐Guerrero (2017) |

US California |

N = 2750 mothers 31.6% incomes at or below federal poverty line 52.8% Latina, 24.1% White, 6.2% Black |

Cross‐sectional descriptive study Secondary data from the Geographic Research on Wellbeing study Self‐report |

N/A | N/A | Level IIIB |

| Qualitative/mixed methods studies | ||||||

| Bess (2014) |

US Nashville Urban |

N = 69 parents of Children 0–4 in low‐income neighborhoods, 85% Black, 87% women, 81% single, 84% unemployed | Qualitative | Prilleltensky's model of well‐being | Tied together | Level IIIA |

| Curry (2019) |

US Midwest Urban |

N = 59 parent participants of 12 focus groups at six elementary schools Majority mothers |

Qualitative | Social network theory | N/A | Level IIIA |

| Davison (2013) |

US Urban |

N = 89 low‐income parents/caregivers of children enrolled in HeadStart 91% female, 52% White, 22% Black, 10% Hispanic |

Mixed‐methods (quantitative measures self‐report) | Family ecological model | N/A | Level IIIC |

| Eastwood (2014) |

Australia Sydney Urban |

N = 8 mothers in low‐income community | Qualitative | None specified | N/A | Level IIIB |

| Lipman (2010) |

Canada Ontario Urban |

N = 8 Single‐mothers, 50% income <$15,000 | Qualitative | None specified | Community‐based program, unspecified | Level IIIB |

| Parsons (2019) |

US Cincinnati Urban |

N = 20 (15 mothers/grandmothers, 5 neighborhood “block captains”) 65% White, 30% Black, 5% mixed race Low‐income neighborhood residents |

Qualitative | None specified | Healthy homes (HH) Block by block (HH) | Level IIIB |

2.6. Analysis

The authors synthesized quantitative and qualitative studies separately, then integrated findings from both sources where applicable (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Given that the included studies addressed multiple research questions across diverse settings, a narrative synthesis was conducted to examine findings from the quantitative studies. Narrative syntheses are used to compare and summarize quantitative data when statistical comparison across studies is not feasible (Lisy & Porritt, 2016; Popay et al. 2006; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Two authors first conducted the narrative synthesis independently, and then three authors met to compare findings and discuss results. The agreed‐upon findings were analyzed and are presented below by specific outcomes.

A thematic synthesis was used to synthesize the results of qualitative studies (Thomas & Harden, 2008). This method uses thematic analysis to integrate the findings of multiple qualitative studies (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Three stages of analysis were conducted iteratively starting with independent line‐by‐line coding of qualitative findings (Thomas & Harden, 2008). Line‐by‐line coding represents the translation of concepts from one study to another (Britten et al., 2002; Qureshi et al., 2006). Codes were developed when necessary and checked for consistency to see if an additional level of coding was needed (Thomas & Harden, 2008). Two authors then compared codes and checked for inter‐coder agreement. The agreed‐upon codes were grouped into descriptive themes representing participants’ perspectives on SC. Analytic themes were then developed based on the descriptive themes to address the aims of the review (Britten et al., 2002; Thomas & Harden, 2008).

3. RESULTS

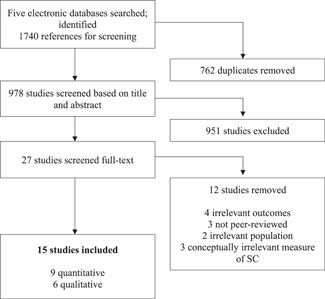

The search resulted in 978 unique records. A total of 951 records were removed through title and abstract screening leaving 27 articles for full‐text review. Following full‐text review, 12 articles were excluded leaving 15 articles for data extraction (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Review process

3.1. Study characteristics

Table 1 highlights the key characteristics of the included study. Twelve studies were conducted in the United States, one in Australia, one in Canada, and one in Nigeria. Most participants were mothers. Seven studies included only mothers, six included a range of caregivers (i.e., mothers, fathers, grandparents), and one included mothers and grandmothers. One study did not report specific caregiver roles (McLeigh et al., 2018).

Nine studies were quantitative and six were qualitative in design. Six studies included an intervention. Of the nine quantitative studies, five utilized a cross‐sectional design, three used a longitudinal design, and one used a quasi‐experimental design. All included studies, except one, were rated as Level III evidence, indicating nonexperimental study designs. The quasi‐experimental study by Brisson et al. (2019) was rated as Level II. Seven studies were rated as high‐quality, Level A, for demonstrating consistent, generalizable results with adequate study designs and sample sizes. Seven studies were rated as quality Level B, indicating good quality by demonstrating reasonably consistent results for the design and sample size. One study was rated as Level C, poor quality, indicating an inadequate study design for the conclusions made (Dang & Dearholt, 2018). Due to the limited number of studies the search produced, the authors decided to not exclude articles based on low‐quality ratings to ensure the most comprehensive review of existing literature.

3.2. SC definition, measures, and guiding theories

Wide variability exists in the terms and measures used to study parental SC in the literature (Table 2). Six studies used the term “social connectedness” or “connectedness” to describe the concept under study. All of these studies used qualitative methods. Ten studies used “social cohesion” to describe parents’ perception of belonging in their relationships. Six of these studies specifically focused on neighborhood social cohesion. One study did not specify an exact term related to SC but reported results in line with the concept of SC (Lipman et al., 2010). The most commonly used measure focused on assessing neighborhood social cohesion; six quantitative articles described using a Likert‐scale measure with questions related to parents’ perception of their neighborhood.

Table 2.

Measures and definitions of social connectedness and related terms used in studies with parents with low incomes

| Quantitative studies | ||

|---|---|---|

| First author (year) | Definition of social connectedness or proxy term | Quantitative measures for social connectedness |

| Acri (2019) | Cohesiveness: feelings of belonging, understood, and accepted by group members | ‐29‐item measure for participants’ perception of the 4Rs 2Ss intervention including 3 items measuring cohesion |

| Adaji (2019) |

Cohesion, Group cohesiveness Definition not specified |

‐3‐item measure of cohesion |

| Booth (2020) |

Neighborhood cohesion‐ Definition not specified |

‐5‐item, Likert scale measure on neighborhood cohesion |

| Brisson (2012) | Social Cohesion: the ability to establish positive relationships and build trust with neighbors | ‐4 items on scale developed to measure social cohesion, informal social control, and collective efficacy |

| Brisson (2019) | Neighborhood social cohesion: Definition not specified | ‐4‐item, Likert scale measure of neighborhood social cohesion, from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods |

| McCloskey (2019) | Neighborhood social cohesion: Mothers’ level of trusting relationships and collective social norms among individuals in a shared community |

‐Social Cohesion and Trust Scale ‐5‐item scale, statements of neighborhood social cohesion |

| McLeigh (2018) | Neighborhood social cohesion: Mutual trust and shared expectations among neighbors |

‐Social Cohesion Scale ‐5‐item Likert‐type scale |

| Prendergast (2019) | Neighborhood social cohesion: mutual trust and support among neighbors | ‐5‐item, Likert scale measure on neighborhood social cohesion |

| Yuma‐Guerrero (2017) | Neighborhood social cohesion: the extent of connectedness and solidarity among residents in a neighborhood | ‐6‐indicator, Likert scale measure on social cohesion in their neighborhood |

| Qualitative studies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Definition of social connectedness or proxy term | Emerging qualitative themes | |

| Bess (2014) |

Social connections Definition not specified |

Access to SC Scarcity Protective avoidance Connectedness Environment of acceptance Normalization |

| Curry (2019) |

Social connections Definition not specified |

Access to SC Scarcity Connectedness |

| Davison (2013) |

Social connectedness Definition not specified |

Access to SC Scarcity Protective avoidance Loss |

| Eastwood (2014) |

Connectedness Social cohesion Definitions not specified |

Access to SC Scarcity Protective avoidance Connectedness |

| Lipman (2010) | Social connectedness term not specified: Article discussed mothers’ connections to participants in a community‐based support/educational group that included components of social connectedness |

Access to SC Scarcity Loss Connectedness Environment of acceptance Normalization |

| Parsons (2019) | Social connection: the ways individuals connect via physical, behavioral, social‐cognitive, and emotional pathways |

Access to SC Scarcity Protective avoidance Connectedness |

|

Environment of acceptance Normalization | ||

Half of the studies provided a theory for guiding their SC research and of those that did include a theory, there was little consistency in the frameworks cited. The most common theory used to frame SC, identified in two studies, was Ecological Theory. Table 1 details the various measures and theories that were used to operationalize the concept of SC.

3.3. Quantitative synthesis

Findings from the nine quantitative studies centered on three overarching themes related to parental SC: parental mental health outcomes, parents' connections to their own community and its resources, and cross‐generational outcomes of SC.

3.3.1. Parental mental health outcomes

Parental mental health outcomes refer to outcomes related to any mental health condition, such as anxiety or depression. McCloskey and Pei (2019) reported higher SC (framed as “neighborhood social cohesion”) was related to lower parenting stress. The study also reported lower parenting stress acted as a partial mediator between SC and maternal anxiety and depression (McCloskey & Pei, 2019).

3.3.2. Connection to community

Five quantitative studies reported various SC outcomes related to parents’ connections to their community, that is, parents’ reported perceptions of or interactions with their communities or neighborhoods, and related resources (Acri et al., 2019; Adaji et al., 2019; Brisson, 2012; Brisson et al., 2019; Yuma‐Guerrero et al., 2017). Yuma‐Guerrero et al. (2017) found SC‐mediated relationships between mothers’ perceptions of neighborhood safety and their engagement in physical activity, suggesting that greater SC may be helpful in improving perceptions of neighborhood safety and parents’ engagement in related activities within the neighborhood. Brisson (2012) reported that SC in their communities (described as “neighborhood social cohesion”) was associated with lower levels of food insecurity.

Interventions were also critical in creating opportunities for parents to gain SC within their communities. Acri et al. (2019) found caregivers who participated in the 4Rs 2Ss program, a family group intervention for children with behavioral difficulties, reported high SC with other caregivers within the program (framed as “group cohesion”; Acri et al., 2019). Brisson et al. (2019) reported low‐income families participating in the intervention, “Your Family, Your Neighborhood,” designed to improve neighborhood social cohesion, showed improvements in SC (framed as “neighborhood social cohesion”). However, these improvements were not significantly greater than those in a comparison group that did not receive the intervention. Adaji et al. (2019) found SC formed during a prenatal care program in Nigeria to be associated with better program outcomes as mothers who participated in the program had higher levels of SC (framed as “group cohesion”) and increased knowledge in pregnancy issues at the end of the program. These findings suggest group‐based interventions may be successful in increasing SC among parents.

3.3.3. Cross‐generational outcomes

Three studies reported findings of how parents’ SC (framed as “neighborhood social cohesion”) influences outcomes for both themselves and their children. For example, McLeigh et al. (2018) found that parents’ perceived SC mediated the impact of neighborhood poverty on child abuse, suggesting increased SC may help to decrease rates of child abuse (McLeigh et al., 2018). Similarly, Prendergast and MacPhee (2020) reported increased SC was significantly associated with decreases in mothers’ aggression toward their children in early childhood (Prendergast & MacPhee, 2020). Finally, Booth and Shaw (2020) discussed perceptions of parental SC were positively associated with parental monitoring of adolescent males in the Pitt Mother and Child Project, suggesting increased SC may be helpful in parenting older children (Booth & Shaw, 2020).

3.4. Qualitative synthesis

Two central themes related to low‐income parents’ experience with SC were discovered from six qualitative studies: (1) parents’ access to SC and (2) connectedness.

3.4.1. Access to SC

The theme of “access to SC” was found across all qualitative studies. This theme characterized parents’ access, or lack of access to SC, contributing to either a sense of belonging or a sense of isolation. Often parents described a lack of access to SC within their community, which contributed to subthemes of scarcity and loss. Scarcity refers to a lack of resources that parents experience in their physical, social, or financial environments. Parents in all qualitative studies described their experiences of scarcity in multiple environments, which hindered their ability to participate in activities or connect with others. Furthermore, many parents described purposely having scarce connections as a form of protective avoidance due to concerns of exposing their children to detrimental social influences in communities they felt unsafe in (Bess & Doykos, 2014; Davison et al., 2013; Eastwood et al., 2014; Parsons et al., 2019). For example, one parent described protective strategies in response to harsh living environments, which in turn created disconnection:

There's a lot of people that's protective over their homes and their children due to…the crime rate. So it's kind of hard … to connect with people. (Parsons et al., 2019, p. 9)

Loss is also salient in parents’ experience with a lack of access to SC (Davison et al., 2013; Lipman et al., 2010). The loss of relationships and associated connections was significant to some who became single parents. For example, Lipman et al. (2010) found single mothers enrolled in an educational/support group attributed their feelings of isolation to a loss of connections after separating from their partner:

‘I found that I felt absolutely alone in the absolute world.’ …many of the women disclosed that their connections to their social circles of friends were severed when their marriages ended. (p. 4)

3.4.2. Connectedness

The theme of connectedness emerged from five studies (Bess & Doykos, 2014; Curry & Holter, 2019; Eastwood et al., 2014; Lipman et al., 2010; Parsons et al., 2019). Subthemes of connectedness include an environment of acceptance, which refers to a supportive group dynamic that allows parents to overcome distrust and build connections. For example, Lipman et al. (2010) found a sense of acceptance within a group enabled parents to share and learn from one another, “…having opportunities to interact with mothers in similar circumstances who could relate to their struggles provided [participants] with a much‐needed environment of acceptance….” (p. 6).

Furthermore, Bess and Doykos (2014) found program facilitators of a parent education group, Tied Together, were key in constructing a group environment that was supportive and promoted building connections among parents:

Graduates attributed much of the success of the program to staff members’ ability to create a supportive environment. One graduate put it simply: ‘If a mom knows she has support, I feel like she will be a better mom overall…at Tied Together, we have support.’ (p.724)

Another subtheme of connectedness was normalization as a process through which SC functions among these parents. For example, Lipman et al. (2010) found that bonded by similar life circumstances, parents were enabled to relate and share their struggles with one another:

… being surrounded by others struggling with the same circumstances allowed these women to share their fears and emotions… ‘[I] sat and just sobbed and it was like this is what I needed and then I got guidance and the whole group understood.’ (p. 6)

Parsons et al. (2019) also noted that the shared identities or lived experiences were the building blocks for trust and connections among parents:

I can tell the difference between somebody that actually has been through what I've been through, so they can actually relate to me compared to somebody that's just book smart and learned all this stuff in a book, or what they've heard on the news. (p. 8)

Outcomes related to improved SC for parents included the strengthening of parenting skills, gaining a sense of connection, overcoming neighborhood distrust, and decreased isolation. Curry and Holter (2019) found the building of social connections strengthened parenting skills and redefined their perceived parent roles by learning from one another:

‘I learned from seeing other parents when we started coming to (name of school)’ and ‘I didn't know what to do, so I asked (name of friend) to help me’ … ‘It's a networking thing. I rely on these women and guys to help me (know what to do)’. (p. 551)

Parents in four studies (Bess & Doykos, 2014; Curry & Holter, 2019; Eastwood et al., 2014; Parsons et al., 2019) also described a greater sense of connection to other parents and the reciprocal support exchanged within these connections:

‘It's like a village type mentality of ‘everyone looks out for everyone else.’ Another parent supported her by stating, ‘We are eyes and ears for the other parents. It's good to have open communication because you would want the same thing coming home to you.’ (Curry & Holter, 2019, p. 551)

Finally, parents in two studies described that their created connections helped to reduce the sense of isolation experienced in their life (Bess & Doykos, 2014; Lipman et al., 2010):

They shared their experiences and it helped me a lot to see that everybody has their own problems, and I'm not the only one… (Lipman et al., 2010, p. 6)

4. DISCUSSION

This review is the first to synthesize existing literature on SC among parents raising children in low‐income communities. Results suggest parents from low‐income communities continue to face significant social isolation, however, SC may play an important role in improving parents’ mental health outcomes and connections to their community (McCloskey & Pei, 2019).

4.1. Conceptualization and measurement of SC

Evidence from this review demonstrates the lack of uniformity surrounding the definition, measurement, and theories used to frame the concept of SC. This creates challenges in synthesizing the literature. Future research should prioritize establishing a clear definition of SC, distinct from its related terms. Conceptual clarity would facilitate communication among researchers and the application of research findings related to SC. Conducting a concept analysis could be an important next step in clarifying the term of SC for future research. More specifically, a hybrid concept analysis that integrates theoretical and fieldwork analyses would be beneficial in providing conceptual clarity to the definition and measurement of SC beyond the scope of this review (Schwartz‐Barcott & Kim, 2000).

Due to SC not being an indexed term, three related terms were used in the search. Out of these three terms, only social and group cohesion were used in studies that met the review's inclusion criteria. Furthermore, of the 10 included studies that utilized the concept of social cohesion, six specifically discussed parents’ neighborhood social cohesion, defined as parents’ connection to others in the community they live in (Prendergast & MacPhee, 2020; Yuma‐Guerrero et al., 2017). This is an important finding as evidence suggests the neighborhoods and communities in which parents live greatly influence the social connections they are able to make, which may influence the way they parent their children.

Perhaps the most significant finding of this review was the lack of validated measures used that specifically assess SC. Of the 9 studies using quantitative measures to assess sense of belongingness (SC or social/group cohesion), only four presented the measures’ reliability or validity (Brisson, 2012; McCloskey & Pei, 2019; McLeigh et al., 2018; Prendergast & MacPhee, 2020). Although validated measures of SC do exist, they are not necessarily applicable for measuring SC in parents. For example, Lee and Robbins published the Social Connectedness Scale in 1995, but the measure was developed for use with college students (Lee & Robbins, 1995); it remains unclear whether this scale can be applied or adapted to measure SC in parents. Additionally, measures are often aimed at assessing a person's overall sense of SC, rather than their connectedness to a specific group, which presents difficulties in assessing for changes in SC related to specific group‐based interventions. Creating measures that capture a person's overall SC and SC related to a specific intervention or group, while maintaining consistency in the conceptual definition of SC, would be beneficial for specifying outcomes in future research efforts.

4.2. Mental health outcomes

Quantitative results demonstrated greater SC in parents with low incomes was associated with decreased anxiety and depression (McCloskey & Pei, 2019). These results are consistent with existing literature showing SC as a protective factor in one's mental health in other populations (Saeri et al., 2018). It is well established that parental mental health can have a significant impact on children's health and well‐being (Manning & Gregoire, 2009). Focusing community efforts on improving SC among parents raising children in low‐income communities could reduce social isolation and improve mental health outcomes for both parents and their children.

4.3. Community connections

Findings from this review suggest that for parents living in communities affected by poverty, low levels of SC may be an unintended consequence of parents’ efforts to protect their children by distancing themselves from others (Bess & Doykos, 2014; Davison et al., 2013; Eastwood et al., 2014). Results also suggest that in the context of community interventions targeted at low‐income families, parents are provided opportunities to gain connections with both their peers and the community (Bess & Doykos, 2014). Interestingly, once parents made social connections with other parents within a group, they benefited from peer advice, support, and connections to other resources. This gaining and exchanging of resources described is more of a function of social support than SC. However, the process of making these social connections that lead to resources being shared suggests SC may act as a precursor for parents’ social support. This finding further emphasizes the need for research evaluating the mechanism by which SC works to influence parents’ health and well‐being.

Our qualitative findings also suggest a possible process and the conditions for which SC develops between low‐income parents and their communities: parents described situations in which they discovered commonalities among their peers which allowed for them to normalize their experiences as parents, gain perspective on other parents’ experiences and develop hope and motivation within their own life (Lipman et al., 2010). Through these shared experiences and positive interactions, parents described a greater sense of connection to other parents, reduced isolation, and new access to peer support and community resources, perhaps contributing to overall improved health outcomes. Future research should focus on identifying programmatic factors of these interventions that promote SC and the long‐term effects of SC on parents to better understand how SC may be obtained and altered through interventions.

4.4. Study focus

Across all studies, the majority of participants identified as mothers. Although this helps to better understand SC related to outcomes for low‐income mothers, there is still very little understanding of how SC may differ in formation and function for other child caregivers. In the United States, the number of children being raised by single fathers and grandparents is increasing (Livingston, 2018; United States Census Bureau, 2014). Further research should investigate how SC affects child caregivers in different roles.

Existing literature also demonstrated a narrow focus on mental health outcomes related to SC. Other health outcomes, such as physical health and general well‐being would be important to assess in future research. Additionally, research that focuses on assessing if SC is a modifiable factor or understanding the process by which health benefits of SC are most likely to be achieved, would be beneficial to inform and optimize interventions for supporting low‐income parents and families. Finally, three studies detailed cross‐generational outcomes related to parent SC, with two of these studies indicating increased SC may be a protective factor against maternal aggression and child abuse (Booth & Shaw, 2020; McLeigh et al., 2018; Prendergast & MacPhee, 2020). Future research should explore other cross‐generational effects of parental SC.

It is also important to note, studies in this review were conducted in several different countries around the world. Differences in cultural norms and expectations may influence parental perceptions of and access to SC. Furthermore, barriers to SC parents' face in low‐income communities may vary based on their country or region. Cultural influences should be evaluated and considered when implementing interventions aimed at improving SC for parents.

4.5. Literature evidence level and quality

Of the 15 studies included in this review, 14 were descriptive studies and one utilized a quasi‐experimental design. The lack of experimental designs is an important limitation as experimental designs are needed to determine causal effects. Although randomized control trials are not always feasible in practice, particularly in community settings, other experimental strategies such as additional quasi‐experimental studies would be beneficial to further enhance the understanding and evaluation of the impact of SC on parents with low incomes.

Most quantitative studies included in this review were cross‐sectional; three used longitudinal design. This creates another limitation in interpreting findings. As previously discussed, a variety of mental health outcomes were associated with SC in parents with low incomes (McCloskey & Pei, 2019). However, due to the cross‐sectional nature, it is difficult to determine if positive mental health enables parents to initiate or cultivate SC or if SC leads to better mental health outcomes. Future research using experimental, longitudinal designs is essential to better understand the potential causal relationship of SC and parents’ health outcomes. Additionally, most quantitative studies included in this review relied solely on self‐reported measures for assessing both SC and its correlates, creating the potential for shared method bias. To minimize such bias, future research should consider using multiple methods and informants to gain a broader perspective of SC.

Of the 15 studies included in this review, five were qualitative and one used a mixed‐method design. Mixed‐method research designs that integrate a qualitative component assessing parents’ perceptions of their SC and related outcomes are important for creating a more in‐depth understanding of these parents’ experiences. A mixed‐method approach would also be beneficial in evaluating interventions to better understand parents’ perceptions of intervention components that facilitate SC.

4.6. Limitations of review

This integrative review is not without its own limitations. First, the authors limited the search to studies published in English peer‐reviewed journals, potentially excluding relevant publications in other languages and reports. This review may also be limited by publication bias, as studies with significant results related to SC among parents are more likely to have been published than studies without significant findings.

Second, the purpose of this review was to establish a clear understanding of SC among parents raising children in low‐income communities. Currently, “social connectedness” is not an indexed term, thus, the authors included additional terms with overlapping definitions in the database search in an attempt to capture all relevant literature. For example, “social cohesion” was included as a related term for SC. Social cohesion is a conceptually well‐established term in both nursing and health sciences that is inclusive of one's “sense of belongingness,” similar to SC, but also extends more broadly to include the connectedness one feels within societal groups (Miller et al., 2020). The authors choose to focus the analysis of the review on areas in which these terms and related measures overlap with SC, and not on how they differ. Therefore, the use of these additional terms potentially limits our conceptual precision of SC. Although the concept of SC is not new, its conceptual clarity is lacking. Establishing a clear definition for SC and indexing “social connectedness” as a MeSH term is essential for building a stronger literature base and ultimately creating more specific measures for evaluating SC. Our goal in this review was to begin that foundational process. It is noteworthy that despite the lack of indexing, the National Institutes of Health has identified SC as a significant area for study, further demonstrating the need to gain conceptual clarity and differentiate SC from other terms (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2019).

5. CONCLUSIONS

Findings from this review emphasize SC as a promising concept that may be protective in the health and well‐being of parents and their children living in low‐income communities. Nevertheless, the absence of a clear conceptual definition and specific measures for SC create challenges in advancing the scientific understanding of these potential benefits. Future work should focus on clarifying the conceptual understanding of SC and developing specific SC measures to better evaluate the mechanisms by which SC works to benefit parents and their children.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Corinne M. Plesko contributed to the conception and design of the integrative review. All authors (Corinne M. Plesko, Zhiyuan Yu, Karin Tobin, and Deborah Gross) contributed to the development of the search strategy for the review. Corinne M. Plesko and Zhiyuan Yu independently preformed the title and abstract screenings and full‐text review of relevant articles. In the event of disagreements in articles for inclusion, Deborah Gross acted as a “tie‐breaker” and independently reviewed the articles in question for inclusion. All four authors contributed to the interpretation of review findings, writing, and revisions of the manuscript. All four authors provided final approval of the version of the manuscript to be published.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Stella Seal, MLS, for her assistance in developing the search strategy for this review. Additionally, the corresponding author, Ms. Plesko, would like to acknowledge Jonas Philanthropies and the Morton K. and Jane Blaustein Foundation for their academic support during the time of this review.

Plesko, C. M. , Yu, Z. , Tobin, K. , & Gross, D. (2021). Social connectedness among parents raising children in low‐income communities: An integrative review. Res Nurs Health, 44, 957–969. 10.1002/nur.22189

REFERENCES

- Acri, M. C. , Hamovitch, E. K. , Lambert, K. , Galler, M. , Parchment, T. M. , & Bornheimer, L. A. (2019). Perceived benefits of a multiple family group for children with behavior problems and their families. Social Work with Groups, 42(3), 197–212. 10.1080/01609513.2019.1567437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adaji, S. E. , Jimoh, A. , Bawa, U. , Ibrahim, H. I. , Olorukooba, A. A. , Adelaiye, H. , Garba, C. , Lukong, A. , Idris, S. , & Shittu, O. S. (2019). Women's experience with group prenatal care in a rural community in northern Nigeria. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 145(2), 164–169. 10.1002/ijgo.12788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bess, K. D. , & Doykos, B. (2014). Tied together: Building relational well‐being and reducing social isolation trhough place‐based parent education. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(3), 268–284. 10.1002/jcop.21609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booth, J. M. , & Shaw, D. S. (2020). Relations among perceptions of neighborhood cohesion and control and parental monitoring across adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(1, SI), 74–86. 10.1007/s10964-019-01045-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brisson, D. (2012). Neighborhood social cohesion and food insecurity: A longitudinal study. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 3(4), 268–279. 10.5243/jsswr.2012.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brisson, D. , Pena, S. L. , Mattocks, N. , Plassmeyer, M. , & McCune, S. (2019). Effects of the your family, your neighborhood intervention on neighborhood social processes. Social Work Research, 43(4), 235–246. 10.1093/swr/svz020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Britten, N. , Campbell, R. , Pope, C. , Donovan, J. , Morgan, M. , & Pill, R. (2002). Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 7(4), 209–215. 10.1258/135581902320432732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59(8), 676–684. 10.1177/0194599813477823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry, K. A. , & Holter, A. (2019). The influence of parent social networks on parent perceptions and motivation for involvement. Urban Education, 54(4), 535–563. 10.1177/0042085915623334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dang, D. , & Dearholt, S. (2018). Johns Hopkins nursing evidence‐based practice: Model and guidelines (3rd ed.). Sigma Theta Tau International. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, K. K. , Jurkowski, J. M. , & Lawson, H. A. (2013). Reframing family‐centred obesity prevention using the Family Ecological Model. Public Health Nutrition, 16(10), 1861–1869. 10.1017/s1368980012004533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyaram, L. , & Kamalanabhan, T. J. (2005). Unearthed: The other side of group cohesiveness. Journal of Social Sciences, 10(3), 185–190. 10.1080/09718923.2005.11892479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood, J. , Kemp, L. , & Jalaludin, B. (2014). Explaining ecological clusters of maternal depression in South Western Sydney. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, 15. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, E. , & Musitu, G. (2003). Social isolation from communities and child maltreatment: A cross‐cultural comparison. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 153–168. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00538-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hämmig, O. (2019). Health risks associated with social isolation in general and in young, middle and old age. PLoS One, 14(7), e0219663. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare Duke, L. , Dening, T. , de Oliveira, D. , Milner, K. , & Slade, M. (2019). Conceptual framework for social connectedness in mental disorders: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245(July 2018), 188–199. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, C. , Cruwys, T. , Haslam, S. A. , & Jetten, J. (2015). Social connectedness and health. Pachana N, Encyclopedia of Geropsychology.Springer. 10.1007/978-981-287-080-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M. A. , Abrams, D. , & Brewer, M. B. (2017). Social identity: The role of self in group processes and intergroup relations. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 20(5), 570–581. 10.1177/1368430217690909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt‐Lunstad, J. , Robles, T. F. , & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist, 72(6), 517–530. 10.1037/amp0000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt‐Lunstad, J. , Smith, T. B. , Baker, M. , Harris, T. , & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta‐analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating‐Lefler, R. , Hudson, D. B. , Campbell‐Grossman, C. , Fleck, M. O. , & Westfall, J. (2004). Needs, concerns, and social support of single, low‐income mothers. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 25(4), 381–401. 10.1080/01612840490432916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R. M. , & Robbins, S. B. (1995). Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(2), 232–241. 10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay Smith, G. , Banting, L. , Eime, R. , O'Sullivan, G. , & van Uffelen, J. G. Z. (2017). The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 56. 10.1186/s12966-017-0509-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman, E. L. , Kenny, M. , Jack, S. , Cameron, R. , Secord, M. , & Byrne, C. (2010). Understanding how education/support groups help lone mothers. BMC Public Health, 10(4), 1–9. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisy, K. , & Porritt, K. (2016). Narrative synthesis: Considerations and challenges. JBI Evidence Implementation, 14(4), 201. https://journals.lww.com/ijebh/Fulltext/2016/12000/Narrative_Synthesis__Considerations_and_challenges.33.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G. (2018). About one‐third of U.S. children are living with an unmarried parent. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/27/about-one-third-of-u-s-children-are-living-with-an-unmarried-parent/

- Manca, A. R. (2014). Social cohesion BT. In Michalos A. C. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well‐being research (pp. 6026–6028). Springer Netherlands. 10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manning, C. , & Gregoire, A. (2009). Effects of parental mental illness on children. Psychiatry, 8(1), 7–9. 10.1016/j.mppsy.2008.10.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey, R. J. , & Pei, F. (2019). The role of parenting stress in mediating the relationship between neighborhood social cohesion and depression and anxiety among mothers of young children in fragile families. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(4), 869–881. 10.1002/jcop.22160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeigh, J. D. , McDonell, J. R. , & Lavenda, O. (2018). Neighborhood poverty and child abuse and neglect: The mediating role of social cohesion. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 154–160. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, H. N. , Thornton, C. P. , Rodney, T. , Thorpe, R. J. , & Allen, J. (2020). Social cohesion in health: A concept analysis. Advances in Nursing Science, 43(4), 375–390. 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd, T. A. M. T. , Yunus, R. M. , Hairi, F. , Hairi, N. N. , & Choo, W. Y. (2019). Social support and depression among community dwelling older adults in Asia: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 9(7), 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Enginerring, and Medicine (2016). In Gadsden, V. L. , Ford, M. , & Breiner, H. (Eds.), Parenting matters: Supporting parents of children ages 0‐8. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/21868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine . (2020). Leading health indicators 2030: Advancing health, equity, and well‐being. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/25682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke, H. M. , & Sidani, S. (2017). Definition, determinants, and outcomes of social connectedness for older adults: A scoping review. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 43, 43–52. 10.3928/00989134-20170223-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbay, F. , Johnson, D. C. , Dimoulas, E. , Morgan, C. A. , Charney, D. , & Southwick, S. (2007). Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry, 4(5), 35–40. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20806028%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC2921311 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantell, M. , Rehkopf, D. , Jutte, D. , Syme, S. L. , Balmes, J. , & Adler, N. (2013). Social isolation: A predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. American Journal of Public Health, 103(11), 2056–2062. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, A. A. , Leggett, D. , Vollmer, D. , Perez, V. , Smith, R. , Goodman, E. , & Riley, C. (2019). Cultivating social relationships and disrupting social isolation in low‐income, high‐disparity neighbourhoods in Ohio, USA. Health & Social Care in the Community. 10.1111/hsc.13301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J. , Roberts, H. , Sowden, A. , Petticrew, M. , Arai, L. , Rodgers, M. , & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. ESRC Methods Programme [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast, S. , & MacPhee, D. (2020). Trajectories of maternal aggression in early childhood: Associations with parenting stress, family resources, and neighborhood cohesion. Child Abuse & Neglect, 99, 104315. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, H. , Fisher, M. , Hardyman, W. , & Homewood, J. (2006). Using qualitative research in systematic reviews: Older people's views of hospital discharge. SCIE Report 9. Social Care Institute for Excellence. https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/113021/ [Google Scholar]

- Rank, M. R. , Duncan, G. J. , & Brooks‐Gunn, J. (1998). Consequences of growing up poor. Contemporary Sociology, 27(6), 568. 10.1016/j.jnnfm.2013.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saeri, A. K. , Cruwys, T. , Barlow, F. K. , Stronge, S. , & Sibley, C. G. (2018). Social connectedness improves public mental health: Investigating bidirectional relationships in the New Zealand attitudes and values survey. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(4), 365–374. 10.1177/0004867417723990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz‐Barcott, D. , & Kim, H. (2000). An expansion and elaboration of the hybrid model of concept development. In Rodgers, B. L., & Knafl, K. A. (Eds.), Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications (2nd ed., pp. 129–159).W.B. Saunders Company. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review. In Friedman H. S. (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 192–217). Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. , & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 1–10. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, T. , Rodebaugh, T. L. , Bessaha, M. L. , & Sabbath, E. L. (2020). The association between social isolation and health: An analysis of parent–adolescent dyads from the family life, activity, sun, health, and eating study. Clinical Social Work Journal, 48(1), 18–24. 10.1007/s10615-019-00730-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau . (2014). 10 percent of grandparents live with a grandchild, census bureau reports. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2014/cb14-194.html

- US Department of Health and Human Services . (2019). Funding opportunity: Research on biopsychosocial factors of social connectedness and isolation on health, wellbeing, illness, and recovery. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-19-373.html

- Veritas Health Innovation (n.d.), Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org

- Wang, J. , Mann, F. , Lloyd‐Evans, B. , Ma, R. , & Johnson, S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore, R. , & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuma‐Guerrero, P. J. , Cubbin, C. , & von Sternberg, K. (2017). Neighborhood social cohesion as a mediator of neighborhood conditions on mothers’ engagement in physical activity: Results from the geographic research on wellbeing study. Health Education & Behavior, 44(6), 845–856. 10.1177/1090198116687537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.