Abstract

Objective

Internet‐based guided self‐help (GSH) programs increase accessibility and utilization of evidence‐based treatments in binge‐eating disorder (BED). We evaluated acceptance and short as well as long‐term efficacy of our 8‐session internet‐based GSH program in a randomized clinical trial with an immediate treatment group, and two waitlist control groups, which differed with respect to whether patients received positive expectation induction during waiting or not.

Method

Sixty‐three patients (87% female, mean age 37.2 years) followed the eight‐session guided cognitive‐behavioural internet‐based program and three booster sessions in a randomized clinical trial design including an immediate treatment and two waitlist control conditions. Outcomes were treatment acceptance, number of weekly binge‐eating episodes, eating disorder pathology, depressiveness, and level of psychosocial functioning.

Results

Treatment satisfaction was high, even though 27% of all patients dropped out during the active treatment and 9.5% during the follow‐up period of 6 months. The treatment, in contrast to the waiting conditions, led to a significant reduction of weekly binge‐eating episodes from 3.4 to 1.7 with no apparent rebound effect during follow‐up. All other outcomes improved as well during active treatment. Email‐based positive expectation induction during waiting period prior to the treatment did not have an additional beneficial effect on the temporal course and thus treatment success, of binge episodes in this study.

Conclusion

This short internet‐based program was clearly accepted and highly effective regarding core features of BED. Dropout rates were higher in the active and lower in the follow‐up period. Positive expectations did not have an impact on treatment effects.

Keywords: binge‐eating disorder, cognitive‐behavioural therapy, efficacy, guided self‐help, internet‐based treatment

Highlights

The present internet‐based guided self‐help program adds to the existing research regarding online treatment of binge‐eating disorder and is currently one of the two existing validated programs available in German language. It is based on an established cognitive‐behavioural treatment approach, shows high acceptance by patients and high efficacy after eight guided online sessions, thereby representing the shortest duration of currently evaluated treatments

During the internet‐based therapy, the number of weekly binge‐eating episodes, depressive symptoms, eating disorder pathology as well as impairments in psychosocial functioning all significantly decreased. These positive effects were maintained during follow‐up (6 months). Abstainer rate (no binge‐eating during last month) continued to increase during follow‐up with booster sessions

An email‐based pre‐treatment positive expectation induction did not alter the temporal course and thus treatment success, of binge episodes

Abbreviations

- AW

Andrea Wyssen

- AWMF

Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften

- BED

Binge‐Eating Disorder

- BDI‐FS

Beck Depression Inventory Fast Screening

- BMI

Body‐Mass‐Index

- CBT

cognitive‐behavioural therapy

- CBT‐E

cognitive‐behavioural therapy enhanced

- CG

control group

- DBT

dialectic‐behavioural therapy

- DSM‐5

diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- ED

eating disorder

- EDE‐Q

Eating Disorder Examination‐Questionnaire

- EMA

ecological momentary assessment

- GSH

guided self‐help

- IPT

interpersonal psychotherapy

- M

mean

- Mini‐DIPS

Diagnostic interview for mental disorders, short version

- N

sample size

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SD

standard deviation

- SM

Simone Munsch

- TAU

treatment as usual

- TG

treatment group

- WBQ

Weekly Binges Questionnaire

- WSAS

Work and Social Adjustment Scale

1. INTRODUCTION

Binge‐eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent loss of control over eating without compensatory behaviour, which is often associated with feelings of shame and guilt. Since 2013, BED represents a diagnostic entity in the feeding and eating disorders section of the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, DSM‐5 (APA, 2013). BED represents the most prevalent eating disorder (ED), manifests most often during early adulthood and is associated with a high patient burden. Lifetime prevalence of BED in adults in Europe ranges from 1.9% to 4% in women and 0.3%–2.5% in men (Keski‐Rahkonen & Mustelin, 2016; Kessler et al., 2013; Schnyder et al., 2012). BED represents the most frequent comorbid mental disorder of obese or overweight individuals with prevalence rates up to 30%–40% (Kessler et al., 2013). BED usually manifests during the age of 20–30 years with a mean age of first onset around 23 years (Kessler et al., 2013; Schnyder et al., 2012). About 40%–60% of individuals with BED show comorbid depressive or anxiety disorders (de Zwaan, 2001; Kessler et al., 2013).

Manualized cognitive‐behavioural (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), are the treatment of choice in BED according to the current German (AWMF, 2019) and the English (NICE, 2017) treatment guidelines. Independent of the setting (face‐to‐face or guided self‐help (GSH)) both approaches are superior to behavioural weight loss treatments (Iacovino et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2010). Especially CBT‐based face‐to‐face and structured self‐help treatments (guided or unguided programs with given content and procedure) have been superior to waitlist conditions in reducing binge‐eating, ED pathology and depressive symptoms, whereas pharmacological treatments, mostly with antidepressants, proved to be superior to pill placebos in reducing binge‐eating and depressive symptoms but did not improve ED pathology (Hilbert et al., 2019; Iacovino et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2010). None of the treatment options above significantly reduced body weight of individuals (Ghaderi et al., 2018; Vocks et al., 2010). In a current meta‐analysis including 43 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) providing face‐to‐face psychotherapy or structured (guided and unguided) self‐help treatments for BED (overall 36 programs were based on CBT), face‐to‐face psychotherapy produced large effects regarding core binge‐eating psychopathology and highest abstinence rates of 45%–55% compared to inactive control groups (CGs; i.e., lacking the active disorder specific ingredient that targets a reduction of core binge‐eating psychopathology). Structured self‐help treatments resulted in abstinence rates of 46% and a medium to large reduction of core binge‐eating psychopathology, while pharmacological and weight loss treatments led to small effects (Hilbert et al., 2019). Similar results were found in a recent RCT which used ecological momentary assessment (EMA; cell phone‐based real‐time assessment of core symptoms) and a standard assessment procedure to capture treatment effects. The integrative cognitive‐affective individual psychotherapy for BED (21 sessions) was compared with a CBT‐oriented GSH‐program integrating a self‐help book to overcome BED (10 guidance sessions) over a total of 17 weeks (Peterson et al., 2020). Standard and EMA assessment showed both significant and comparable reduction in binge‐eating at the end of treatment. There were further no differences between the two groups regarding general ED pathology nor emotion regulation, but 26.8% of the participants dropped out in the GSH treatment whereas only 8.9% terminated treatment prematurely in the individual psychotherapy treatment (Peterson et al., 2020).

Even though there is substantial evidence on the efficacy of different psychological treatment options for BED, a still considerably large group of individuals do not receive adequate treatment (Hart et al., 2011). In Switzerland, about 50% of all individuals with BED never seek or have access to a specialized treatment (Schnyder et al., 2012) due to the lack of specialized institutions and resources and due to large distances to treatment facilities in remote areas. In addition, stigmatization of overweight, of binge‐eating and of mental illnesses in general, low mental health literacy and financial aspects might be related to limited help‐seeking behaviour (Schnyder et al., 2017). Therefore, treatment approaches that improve access for BED patients and still provide high efficacy are needed.

Research indicates that guidance in self‐help programs is highly appreciated by patients, even if the contact to the therapist is standardized and only rarely offered (Aardoom et al., 2013; Beintner et al., 2014). Grilo and Masheb (2005) showed that a 12‐week GSH manual based program (based on Fairburn, 1995), including guidance with 6 short individual face‐to‐face meetings to motivate patients and to solve emerging problems, is efficacious. The GSH program resulted in a completer rate of 87% and an abstainer rate of 46% (i.e., no binge‐eating episodes during the last month), whereas lower abstainer rates of 18% and respectively 13% were found in a weight loss program and in a CG without any specific intervention (Grilo & Masheb, 2005). Further, Striegel‐Moore et al. (2010) compared a 12‐week (eight sessions) GSH program (based on Fairburn, 1995) with a treatment as usual (TAU; unspecific treatment or case management) in a naturalistic primary care setting. Treatment sessions were guided in presence by master's level therapists, whose main role were to introduce the rational of a cognitive‐behaviourally oriented GSH program, to explain the necessity of realistic outcome expectancies and to support the patient in adhering to the manual‐based program. The abstinence of binge‐eating for one month amounted up to 64.2% for the GSH program and only 44.6% for the TAU after 12 months. The GSH also obtained higher improvements in ED pathology, depression and quality of life compared to TAU (Striegel‐Moore et al., 2010).

The potential of new technologies to provide GSH programs in eating disorders has been underlined by several systematic reviews (Aardoom et al., 2013; Dölemeyer et al., 2013; Schlegl et al., 2015). Aardoom et al. (2013) identified 21 studies applying internet‐based GSH treatments for EDs. Overall, internet‐based GSH programs were highly efficacious and superior to waitlist conditions, especially in individuals with fewer comorbid disorders and in individuals with binge‐eating in contrast to restrictive ED psychopathology. Moreover, patients with BED showed better outcomes than patients with bulimia nervosa. In addition, therapist‐guided programs (e.g., via e‐mail) resulted in increased positive effects compared to non‐guided programs (Aardoom et al., 2013).

Previous self‐help programs using new technologies provide first evidence for high efficacy. A recent RCT examined the efficacy of a 12‐week CBT‐based GSH (ED‐related) with a smartphone app compared to standard care (no ED‐related services) for individuals suffering from binge‐eating with or without purging behaviour (Hildebrandt et al., 2020). Participants in the GSH program showed higher rates of abstinence from binge‐eating after the 12‐week treatment (41.8%) than participants of the standard care condition (16.1%), this difference persisting even at the 52‐week follow‐up assessment (56.7% vs. 30%). Similar results supporting the superiority of the GSH program, were found for the outcome variables compensatory behaviour, ED pathology and clinical impairment (Hildebrandt et al., 2020). The reduction of binge‐eating was also demonstrated in a guided 12‐week self‐help treatment approach based on dialectic‐behavioural therapy (DBT) which integrated six 30‐min video sessions for guided or unguided active control condition (self‐help program to improve self‐esteem). BED symptomatology was effectively reduced with 45% abstinence from binge‐eating in the GSH condition, but the guided DBT‐program received the best subjective evaluation of the participants (i.e., suitability and effectiveness) and dropout rate was 29% in the GSH condition, but highest in the unguided active control condition with 43% of dropouts (Carter et al., 2020). An even shorter internet‐based CBT‐oriented 10‐session GSH program (with weekly written support of a therapist) showed large reduction in BED symptoms, but abstinence rate was not reported and the study was no RCT (Jensen et al., 2020). In sum, GSH programs can be considered to be efficacious in reducing the core BED symptomatology and in increasing accessibility, especially if they are delivered via books or new technologies, as the users benefit from the treatment offer independently of time and location (Moessner et al., 2016; Schnyder et al., 2017).

Out of the CBT‐based GSH internet‐based programs in BED only two non‐English GSH internet‐based programs have been evaluated in RCTs, the German INTERBED program (de Zwaan et al., 2012) and the French SalutBED program (Carrard, Crepin, Rouget, Lam, Van der Linden, et al., 2011). Both programs are based on the same 11 modules inspired by Christopher Fairburns GSH program (1995). The French program SalutBED, includes a treatment period of 6 months and a weekly e‐mail contact with a therapist. This program has shown high acceptance in patients suffering from BED with and without obesity (Carrard, Crepin, Rouget, Lam, Golay, et al., 2011; Carrard, Crepin, Rouget, Lam, Van der Linden, et al., 2011). After participating in SalutBED, 35% abstained from binge‐eating in the active internet‐based treatment group (TG) compared to 8% in the waitlist CG. Abstinence rate at 6‐month follow‐up was 43%. In addition to the reduction of binge‐eating episodes and ED pathology, depressive symptoms decreased, and quality of life increased at post‐treatment and at 6‐month follow‐up compared to a waitlist CG (Carrard, Crepin, Rouget, Lam, Golay, et al., 2011; Carrard, Crepin, Rouget, Lam, Van der Linden, et al., 2011). The only existing internet‐based GSH program in German, INTERBED (de Zwaan et al., 2012) confirmed the efficacy of such a treatment with an improvement of BED core symptoms after the 4 months’ internet‐based treatment including weekly e‐mail contacts with a therapist. Nevertheless, a face‐to‐face treatment outperformed the internet‐based GSH and showed faster and more beneficial effects regarding binge‐eating frequency and ED pathology (in face‐to‐face treatment: abstinence rate of 61% at post‐treatment, 58% at 6‐month follow‐up; in GSH: abstinence rate of 36% at post‐treatment, 38% at 6‐month follow‐up). At 1.5‐year follow‐up, both 4‐month treatment options revealed comparable positive results (de Zwaan et al., 2017).

Despite these promising results, there is currently no study examining the treatment effect of a significantly shorter GSH program, which was therefore the aim of this study.

Alongside the advantages of internet‐based programs, there are also caveats such as the handling of severe crisis and the increased dropout rates in internet‐based GSH programs which vary between 5% and 77% (Aardoom et al., 2013) compared to 12% and 34% in traditional face‐to‐face treatments for BED (Flückiger et al., 2011). Therefore, early detection of potential dropouts and of patients with limited outcome success is required to understand limitations of a treatment program and improve treatment procedures. So far, there is no data on temporal trends available to understand individual changes over GSH program which could help to reduce dropout rates in the long run. Pre‐treatment personal contacts and therapists' e‐mail guidance have shown to increase compliance and reduce dropout rates in internet‐based GSH programs (Aardoom et al., 2013; Brauhardt et al., 2014; Iacovino et al., 2012; Kass et al., 2013). Personal contacts contribute to an improved alliance with the therapist and in combination with positive treatment and outcome expectations can provoke a symptom reduction without providing symptom‐oriented interventions (Greenberg et al., 2006; Wampold et al., 2016). Larger dropout rates of up to 37% need to be expected for GSH treatment of BED patients according to a meta‐analysis (Linardon et al., 2018) and to which extent dropout rates and treatment outcomes can be influenced by expectations remains unclear.

In general, positive outcome expectations have been positively related to treatment outcome as summarized in the meta‐analysis of Constantino et al. (2011) who found small but significant positive effects of pre‐ or early treatment expectations (i.e., beliefs about consequences and benefits of their engagement by following a treatment) on treatment outcome. For instance, in pain treatment, interventions such as verbal suggestion and mental imagery have often been applied to induce positive expectations of a pain treatment. A meta‐analysis revealed positive effects of such interventions on acute pain relief with medium effect sizes and small effects on chronic pain in active and in placebo treatments (Peerdeman et al., 2016). Also in psychotherapy, positive expectations have been positively related to positive treatment outcomes. For example, Price and Anderson (2012) found patients' self‐reported positive expectations to explain up to 33% of variance in treatment outcome in a CBT group intervention and individual virtual reality interventions (no difference between interventions) in adults with social anxiety disorders. Constantino et al. (2012) summarized empirical evidence of clinical interventions (such as motivational enhancement techniques, hope inspiring statements, etc) to address expectations regarding psychotherapy outcome. They found preliminary evidence for the potential of such interventions, and they confirmed the positive influence of expectations on treatment outcome. Therefore, positive expectations might have a potential impact on treatment efficacy and acceptance of GSH treatment approaches, but so far no evidence exists for BED treatments nor for GSH approaches.

In order to advance the evaluation and accessibility of GSH treatment approaches, the original CBT manual of Munsch et al. (2018), relying on the transdiagnostic CBT approach for eating disorders (CBT‐E; Murphy et al., 2010), was shortened to include only eight sessions and has shown short‐ and long‐term efficacy in face‐to‐face group settings (Fischer et al., 2014; Munsch et al., 2007, 2012; Schlup et al., 2009). This manual was then adapted to a book‐based and e‐mail guided GSH program. The book‐based cognitive‐behavioural GSH program included weekly e‐mail contacts in a naturalistic clinical setting. Weekly binge‐eating episodes declined from 4.4 at pre‐ to 1.3 at post‐treatment of the 8‐week program and further to 0.6 at 6‐month follow‐up (including three booster sessions). Abstinence rate increased from 4% at pre‐treatment to 15% at post‐treatment and 47% at 6‐month follow‐up. Also, general ED pathology (including eating, weight and shape concerns as well as restraint eating), anxiety and depressive symptoms also decreased (Wyssen et al., 2019). Based on these encouraging results in such a short treatment program, the results of the internet‐based programs SalutBED (Carrard, Crepin, Rouget, Lam, Van der Linden, et al., 2011), and INTERBED (de Zwaan et al., 2017), in a next step, the content of the original self‐help program was implemented as an internet‐based GSH program named ‘BED‐Online’ to evaluate treatment efficacy and patients' acceptance.

Consequently, the aims of the current study were to detect patients' acceptance of the BED‐Online program (i.e., patients' satisfaction with the program and dropout rates) and to evaluate the eight sessions program's efficacy across time (primary outcome: binge‐eating episodes; secondary outcomes: depressive symptoms, ED pathology, level of psychosocial functioning). Treatment efficacy was tested in two different ways: First, we compared the time course of primary and secondary outcomes between the immediate treatment group (TG) during the first 4 weeks of the internet‐based treatment program (BED‐Online) with the time‐course of the two combined waitlist CGs during their 4‐week waiting period. Second, the temporal course of the primary (binge‐eating episodes, depressive symptoms) and secondary outcomes (ED pathology, level of psychosocial functioning) was followed during the treatment period and during follow‐up in all three groups combined (TG, CGs).

In order to learn more about the influence of patients' expectations regarding the treatment outcome on primary and secondary outcomes, we further explored whether symptoms decreased more strongly when patients received a positive expectation induction while waiting, compared to patients randomized to the pure waiting group.

2. METHOD

2.1. Patients

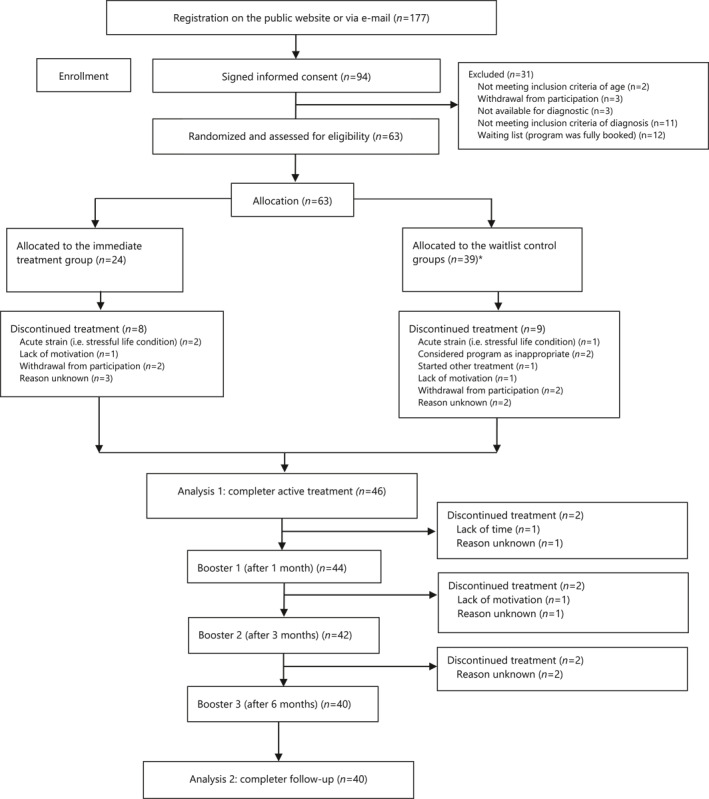

A total of 63 patients (55 women, 8 men (87%/13%)) with a BED were recruited via the outpatient centre for psychotherapy at the department of psychology (University of Fribourg), via public advertisements, media, and cooperating clinicians to participate in the ‘BED‐Online’ study (see Figure 1). Inclusion criteria for study participation were a primary diagnosis of BED according to DSM‐5 (APA, 2013) as assessed with the Mini‐DIPS (Margraf & Cwik, 2017), aged between 18 and 70 years and provided written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were current pregnancy, the presence of another serious psychological or medical condition warranting priority treatment, the lack of sufficient German language or of technical skills to access the program (both self‐reported).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram. Notes. *Allocated to the positive expectation induction wait‐list control group (n = 20), allocated to the pure wait‐list control group (n = 19)

The mean age of patients was 37.2 years (SD = 10.4), and the majority was Swiss (n = 56), six were German and one Austrian. Altogether, 48% hold a university degree, 17% reported a higher education entrance qualification, 32% a degree from a professional school, and 3% had a lower educational attainment. 35.9% of patients suffered from a comorbid depressive or anxiety disorder, 3.1% from another comorbid mental disorder. A total of 43% of the patients were simultaneously involved in another medical, psychological, or other treatment while participating in our BED‐Online program (at pre‐treatment 15.6% of patients took an antidepressant, 1.6% used laxatives, 3.1% other psychopharmacological drugs, 9.4% other medication (not psychopharmacological); 20.3% of patients followed another psychotherapeutic treatment in addition to BED‐Online at pre‐treatment, 17.8% at post‐treatment).

After the diagnostic phase where inclusion criteria were met, patients were randomly allocated (permuted block design; Lachin et al., 1988) to the three groups (TG, pure waitlist CG or positive expectation induction waitlist CG). No blinding procedure was applied.

2.2. Procedures

After participants gave written consent, online questionnaires were provided, and mental disorders were assessed in a clinical interview on the phone. Thereafter, patients were either randomized to the active treatment phase (see Figure 1) including eight weekly online sessions, followed by three booster sessions 1, 3, and 6 months after the last treatment session, or to a 4 weeks’ waiting period before the start of the treatment phase, followed by booster sessions. The time span of 4 weeks was chosen to assess the potential effect of an immediate treatment compared to a waitlist over a reasonable time period. A detailed description of the study design is available in the study protocol (Munsch et al., 2019).

Within the 4 weeks' waiting period, patients were randomly allocated to either a pure waitlist control group (standard CG) or a positive expectation induction waitlist control group (positive CG). Patients in positive CG received four weekly standardized messages from their therapist to induce positive expectation, that is, (a) information on the efficacy of BED treatment offers (e.g., ‘This program relies on an established face‐to‐face CBT program for BED); (b) compliments for accomplishing the first step towards GSH treatment (e.g., ‘By joining this program you have made a first important step on your way to overcome binge‐eating’); (c) quotes from former patients (e.g., ‘I was suffering from binge‐eating for many years. During the GSH program, I developed useful skills and I learnt how to handle my emotions without eating’). In contrast, therapists did not interact with patients of the standard CG (they did not receive any messages during the 4 weeks waiting period). Patients of both CGs were monitored for weekly binge‐eating episodes and changes in weekly mood. After the waiting period, patients of both CGs started with the internet‐based GSH program analogously to the immediate TG.

In the treatment phase, all patients were invited to work on the different exercises during and between the weekly sessions and to implement interventions in daily life.

All patients were accompanied and guided by one of seven therapists who were specifically trained by the first and last author (AW, SM) to deliver the current internet‐based treatment. Therapists were psychotherapists or psychologists in postgraduate training of psychotherapy at the recruiting centre and were continuously supervised by AW and SM in weekly meetings.

The therapists sent a feedback to the patients after each weekly session and after all booster sessions via the integrated communication system of the GSH program (Vanhulst et al., 2020). The therapists' feedback was standardized and based on text templates, which were previously developed and evaluated in a book‐ and e‐mail‐based treatment (Wyssen et al., 2019). Standardized contents of the messages were then customized to the patient's individual needs (e.g., response to specific questions of the patient, comments on individual goals and edited exercises as well as on the progress of the patient). The communication between therapists and patients via the built‐in communication system was continuously supervised by AW and SM.

The content of the eight sessions during active treatment and the three booster sessions is presented in Table 1. Only after having completed a session, the next session was unlocked for the following seven days to guide patients to proceed session by session. The sessions began with an introduction to the contents, how to use the program and development of an individual crisis plan to enable patients to react in case of severe crisis, including a stepped approach of help‐seeking behaviour and tangible instructions (contact details of friends or relatives, of the therapist, of a local 24 h emergency room).

TABLE 1.

Content of therapy sessions in ‘BED‐Online’

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 0 | Introduction in the contents and the how to use the program, individual crisis plan |

| 1 | Setting up an individual etiological model of regular binge‐eating episodes; introduction in how and why to self‐observe eating behaviour |

| 2 | Techniques to increase and maintain motivation; Setting up an individual goal attainment scale |

| 3 | Introduction of techniques on how to implement regular eating, despite experiencing binge‐eating episodes; Identifying triggers of binge‐eating episodes according to the ABC‐model (antecedents – behaviour (reaction) – consequences) |

| 4 | Developing strategies to overcome binge‐eating (trigger and reaction control) |

| 5 | Introduction of positive/enjoyable activities to maintain motivation and increase mood; Planning your relapse! Development of individual emergency cards to improve the coping with binge‐eating episodes |

| 6 | Application and further development of strategies |

| Introduction in the role of dysfunctional thoughts in the maintenance of binge‐eating episodes | |

| 7 | The role of dysfunctional thoughts in the development and maintenance of a negative body image; information about the potential need to reduce overweight and introduction of a step‐by‐step long‐term approach to reach weight loss on a long term |

| 8 | Setting longer‐term goals with respect to binge‐eating and individual goals; Coping with future difficulties; Relapse prevention |

| Booster sessions 1–3 | Further goals; Coping with current difficulties; Relapse prevention |

Weekly binge‐eating episodes (WBQ) and depressive symptoms (BDI‐FS) were both assessed at 14 time points (at pre‐, post‐, and follow‐up measurement of the treatment period and at the beginning of each session) to allow a detailed observation of the temporal course. ED pathology (EDE‐Q) and level of psychosocial functioning (WSAS) were assessed three times (pre, post, and follow‐up). A diagnostic interview took place at the end of the follow‐up.

The study procedure was approved by the cantonal Ethics Committee (Project‐ID: 2017‐00102) and conforms the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were informed in accordance with the study protocol approved by the Ethics Committee (clinical study protocol version 4, 06.07.2017) and gave their written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. The study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Registry (DRKS00012355. Date of registration: 14.09.2017).

2.3. Materials & Measures

Diagnostic interview for mental disorders, short version (Mini‐DIPS; Margraf & Cwik, 2017): Before the start of the treatment (pre‐assessment) and one week after the 8th session (post‐assessment), the Mini‐DIPS, a structured interview to verify the diagnosis of a BED and to assess further mental disorders according to the DSM‐5 was conducted. The acceptance, reliability, validity and interrater reliability of diagnoses according to the Mini‐DIPS had been satisfying in samples of outpatient, inpatient and research populations (Margraf & Cwik, 2017).

The following measures were assessed via online self‐report questionnaires before the start of the treatment (pre‐assessment), one week after the 8th session (post‐assessment) and one week after the third booster session (follow‐up assessment).

Body‐Mass‐Index (BMI): Height and weight of all patients were assessed via self‐report. The BMI was calculated by weight (in kg) divided by the square of the height (in metres).

Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; Mundt et al., 2002): This questionnaire consists of five items to assess the functional impairment in the area of work, family and social functioning. Internal consistency (Cronbach's α) ranges from 0.70 to 0.94, test‐retest reliability of 0.73 has been reported (Mundt et al., 2002). In the present sample, Cronbach's α at baseline was 0.85 (range of further time points was 0.88–0.89).

Eating Disorder Examination‐Questionnaire (EDE‐Q; Hilbert & Tuschen‐Caffier, 2016): The EDE‐Q consists of 28 items. This questionnaire was used for the assessment of ED pathology during the last 28 days. It contains the four subscales restraint eating, eating concerns, weight concerns, shape concerns and a total score. Satisfactory test‐retest reliability ranging from r = 0.66 to 0.94 have been found (Berg et al., 2012). The EDE‐Q subscales and total score also demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach's α) from 0.70 to 0.97 (Hilbert et al., 2012; Hilbert & Tuschen‐Caffier, 2016). In the present sample, Cronbach's α of the total score at baseline was 0.92 (range of further time points was 0.92–0.93).

The following two questionnaires were applied weekly during waiting period and before each treatment session (during active treatment and follow‐up).

Beck Depression Inventory Fast Screening (BDI‐FS; Beck et al., 2013): The BDI‐FS (short version of the BDI‐II) was used to assess depressive symptoms with seven items during the past seven days (weekly assessment). An internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of 0.84 and a convergent validity of r = 0.67 has been reported (Kliem et al., 2014). In the present sample, Cronbach's α at baseline was 0.88 (range of further time points was 0.78–0.91).

Weekly Binges Questionnaire (WBQ; Munsch et al., 2007): The WBQ was used to assess regularity of eating and frequency as well as characteristics of binge‐eating episodes and compensatory behaviour during the last 7 days (weekly assessment). It consists of seven items; in this study only one single item was included to the statistical analyses (item 5: number of binge‐eating episodes; ‘How many binge episodes did you experience during the last week?'). Patients were clearly instructed before how they should identify a binge episode (objectively increased amount of food, more than usual, related to loss of control). A high convergent validity relative to EMA has been found (Munsch et al., 2009).

The following self‐report questionnaire was administered via the online platform at the post‐ and the follow‐up‐assessment.

Treatment Satisfaction (own items): Patients were asked to report their satisfaction with the treatment on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very much) at the end of the active treatment and after follow‐up. The evaluation of the treatment consisted of 11 items (e.g., ‘How satisfied are you with the online treatment program?’, ‘Would you recommend the online treatment program to other people?’, ‘How much have you benefited from the online treatment program regarding overcoming BED?’). In the present sample, Cronbach's α of the total score at baseline was 0.94.

2.4. Statistical analyses

To report patients' acceptance of the program (dropout rates and treatment satisfaction), we used descriptive statistics, that is, means and standard deviations for treatment satisfaction, and counts and percentages for dropouts. Due to the hierarchical nature of the data (time points nested within subjects), we used multilevel models for the statistical analyses, thereby adhering to the intent‐to‐treat principle. Multilevel models have been shown to provide more efficient and less biased results compared with complete case analyses or analyses in which missing values are imputed using the last observation carried forward method (Lane, 2008). To compare the temporal course of each of the two weekly measured outcomes WBQ and BDI‐FS during the first 4 weeks of active treatment in the immediate TG with that of two combined CGs during the waiting period (first aim: immediate treatment vs. waitlist), we used a multilevel model with time (linear trend) and group (TG vs. combined CGs) as fixed effects and a random intercept. To analyse the temporal course of all four outcomes (WBQ, BDI‐FS, EDE‐Q, WSAS) during active treatment and into follow‐up with all three groups combined (second aim: temporal course during treatment and follow‐up), we used a discontinuous model (Singer & Willett, 2003), implying different linear trajectories for active treatment and for follow‐up phase, with a turning point set at the end of active treatment. The model contained time (for active treatment and for follow‐up phase) and group as fixed effects, and intercept and slope (for active treatment and for follow‐up phase) as random effects. Differences between outcomes at specific time points (end of treatment and end of follow‐up) were computed using contrast analyses. Outcomes were transformed, if necessary, to meet model assumptions. Thus, the following transformations were applied: for WBQ, ln (x + 1); for BDI‐FS and WSAS: sqrt(x).

Standardized coefficients (beta) were computed according to Equation 2.13 in Hox et al. (2010). We additionally computed coefficients of determination (R 2 beta) according to Nakagawa and Schielzeth (2013) using the R Package r2glmm (Jaeger, 2017).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics and descriptive results (mean values of all patients at the respective time points) are presented in Table 2. Abstainer rates (i.e., no binge‐eating episodes during the last month) increased from 0 to 18% after the active treatment (eight sessions) and to 38% at follow‐up after three booster sessions during 6 months (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Sample characteristics at pre‐, post‐, and follow‐up‐assessment

| Pre (n = 63) | Post (n = 46) | Follow‐up (n = 40) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||||||||

| Total | TG | Standard CG | Positive CG | Total | TG | Standard CG | Positive CG | Total | TG | Standard CG | Positive CG | |

| Age | 37.21 (10.40) | 36.50 (10.52) | 38.53 (11.62) | 36.80 (9.52) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| BMI | 30.90 (8.62) | 28.71 (9.17) | 31.90 (8.31) | 32.58 (8.08) | 30.79 (8.63) | 29.13 (9.05) | 31.49 (8.84) | 31.93 (8.26) | 29.74 (7.53) | 28.32 (6.65) | 29.74 (8.17) | 31.17 (7.94) |

| WBQ weekly binges | 3.35 (2.38) | 2.79 (2.23) | 4.11 (2.85) | 3.30 (1.95) | 1.66 (1.99) | 1.75 (1.34) | 2.07 (2.89) | 1.14 (1.46) | 1.08 (1.95) | 0.92 (0.95) | 1.62 (3.15) | 0.69 (0.85) |

| BDI‐FS | 4.54 (3.37) | 4.42 (3.28) | 4.79 (3.99) | 4.45 (2.96) | 2.49 (3.47) | 2.44 (2.66) | 2.53 (3.40) | 2.50 (4.50) | 2.03 (2.55) | 2.85 (2.54) | 1.71 (2.33) | 1.54 (2.76) |

| EDE‐Q Item 15: monthly binges | 12.84 (6.98) | 12.04 (8.30) | 14.58 (5.56) | 12.15 (6.48) | 5.61 (6.09) | 6.00 (4.77) | 8.00 (8.50) | 2.61 (2.20) | 2.98 (3.90) | 4.38 (4.17) | 3.14 (4.13) | 1.38 (2.93) |

| EDE‐Q 15 abstainer rate | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 17.8% | 12.5% | 13.3% | 28.6% | 37.5% | 7.7% | 42.9% | 61.5% |

| EDEQ total | 3.12 (1.21) | 3.05 (1.24) | 2.97 (1.31) | 3.33 (1.09) | 2.10 (1.16) | 2.29 (1.26) | 2.16 (0.94) | 1.84 (1.28) | 1.91 (1.22) | 2.40 (1.10) | 1.99 (1.40) | 1.32 (0.95) |

| WSAS | 11.95 (8.04) | 11.92 (8.74) | 12.21 (7.44) | 11.75 (8.10) | 8.04 (8.10) | 6.25 (3.92) | 10.13 (8.98) | 7.86 (10.41) | 7.25 (6.80) | 9.46 (5.70) | 6.79 (5.48) | 5.54 (8.74) |

Notes: Pre = baseline before treatment started, post = after eight sessions of active treatment, follow‐up = after 6 months of follow‐up (with three booster sessions); TG = immediate treatment group, standard CG = pure waitlist control group, positive CG = positive expectation induction waitlist control group; abstainer rate, no binge‐eating episode during the last month.

Abbreviations: BDI‐FS, Beck Depression Inventory Fast Screening; BMI, Body Mass Index; EDE‐Q, Eating Disorder Examination‐Questionnaire; WBQ, Weekly Binges Questionnaire; WSAS, Work and Social Adjustment Scale.

3.2. Patients' acceptance of the program

Out of 63 patients who entered the ‘BED‐Online’ program, 17 (27%) dropped out during the eight sessions of the active treatment phase, and an additional six (9.5%) during the booster sessions (see Table 3). Thus, the overall dropout rate was 36.5%. Reasons for dropouts were discontinuation because of another burden/strain (6.3%), dissatisfaction with the program (4.8%), lack of time (4.8%), lack of motivation (4.8%), switch to another treatment (1.6%), or unknown (14.7%). Dropout rates did not differ among the three groups, neither for the time period baseline to end of active treatment (χ2 (2) = 0.33, p = 0.848) nor for the time period baseline to end follow‐up (χ2 (2) = 1.02, p = 0.600). In addition, dropout rates across the entire study period did not differ between females and males (χ2 (1) = 0.11, p = 0.741), and were neither associated with age (χ2 (1) = 0.01, p = 0.934), nor with weekly pre‐treatment binge‐eating episodes (WBQ, χ2 (1) = 0.63, p = 0.426), weekly pre‐treatment depressive symptom (BDI‐FS, χ2 (1) = 0.19, p = 0.662), pre‐treatment level of psychosocial functioning (WSAS, χ2 (1) = 0.038, p = 0.846), or with pre‐treatment ED pathology (EDE‐Q, χ2 (1) = 0.94, p = 0.332; each test based on a logistic regression model). Treatment satisfaction of the completers was high with a mean value of 8.31 (SD = 1.54) at post‐ and 8.20 (SD = 1.53) at follow‐up assessment. (0 = not at all satisfied, 10 = very satisfied). There was no severe crisis during the study.

TABLE 3.

Overview of dropouts (N = 63 allocated patients)

| Group (Number of Allocated patients) | Dropout from baseline to the end of active treatment | Dropout from baseline to the end of follow‐up | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| TG (n = 24) | n = 8 (33.3%) | n = 3 (12.5%) | n = 11 (45.8%) |

| Standard CG (n = 19) | n = 4 (21.1%) | n = 1 (5.3%) | n = 5 (26.3%) |

| Positive CG (n = 20) | n = 5 (25.0%) | n = 2 (10.0%) | n = 7 (35.0%) |

| Total (N = 63) | n = 17 (27.0%) | n = 6 (9.5%) | n = 23 (36.5%) |

Note: Dropout rates among the three groups did neither differ at the end of active treatment (c2 = 0.87, p = 0.64) nor at the end of follow‐up (c2 = 0.55, p = 0.76).

Abbreviations: standard CG = pure waitlist control group; TG, immediate treatment group; positive CG = positive expectation induction waitlist control group.

3.3. Program efficacy

3.3.1. Immediate treatment versus waitlist (first study aim)

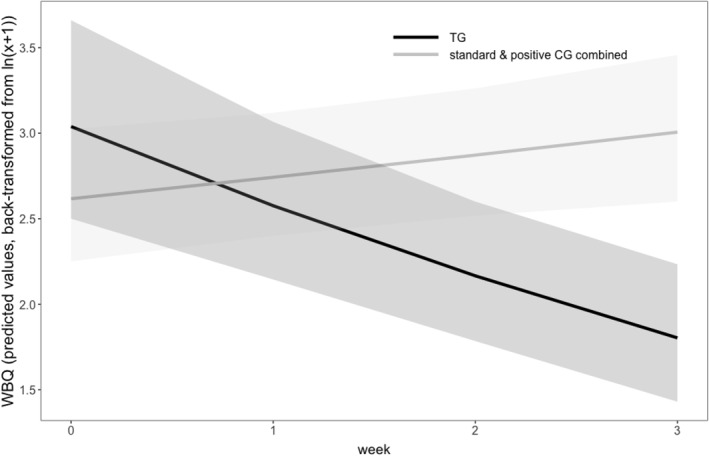

The comparison of the temporal trend during the 4 weeks of waiting period in the combined CGs with that of the first 4 weeks of active treatment in the TG (see Figure 2 and Table 4) revealed a strong linear decline in TG relative to CGs for WBQ (b = −0.156, SE = 0.055, t 159 = −2.81, p = 0.006, beta = −0.124, R 2 beta = 0.02). Thus, the trend in symptom reduction during the first four treatment sessions was significant in the TG (p = 0.007), but not in the combined CGs (p = 0.305). In contrast, no such differences in trend lines were observed for BDI‐FS (b = 0.024, SE = 0.070, t 160 = 0.34, p = 0.736, beta = −0.011, R 2 beta < 0.001), with trend lines of both CGs during waitlist and TG during the first 4 weeks of active treatment not exhibiting significant temporal changes (p = 0.779 for TG, p = 0.348 for CGs).

FIGURE 2.

Comparing temporal trends of active treatment with waitlist during the first 4 weeks (N = 63). Notes. TG = immediate treatment group; standard CG = pure waitlist control group; positive CG = positive expectation induction waitlist control group; WBQ = weekly binges questionnaire. Shaded areas denote ±1 standard error. Time points 0–3 indicate sessions 1–4 in the TG and 4‐week waiting period in the CGs

TABLE 4.

Descriptive statistics of WBQ and BDI‐FS during the first 4 weeks of treatment (TG)/4 weeks of the waiting period prior to treatment (standard CG and positive CG)

| WBQ | BDI‐FS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG | Standard CG | Positive CG | TG | Standard CG | Positive CG | |

| N | n | N | N | n | N | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Week 1 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 17 |

| 4.05 (3.97) | 4.00 (3.22) | 2.65 (2.52) | 4.00 (3.14) | 4.94 (4.24) | 4.65 (4.44) | |

| Week 2 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 18 |

| 3.63 (4.18) | 4.22 (2.62) | 2.33 (1.91) | 3.68 (3.54) | 4.17 (3.84) | 4.00 (4.24) | |

| Week 3 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 19 |

| 2.53 (2.07) | 5.06 (4.28) | 2.68 (2.43) | 3.90 (3.95) | 4.72 (3.94) | 4.58 (4.89) | |

| Week 4 | 20 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 16 | 18 |

| 2.35 (1.95) | 4.25 (3.28) | 3.89 (3.95) | 4.15 (3.67) | 4.75 (4.42) | 4.44 (5.02) | |

Notes: Week = waiting week in the CGs, treatment in the TG . Note that for patients in the TG group values refer to time points 1–4 within the treatment phase whereas for patients in standard CG and positive CG values refer to time points 1–4 within the waiting period.

Abbreviations: BDI‐FS, Beck Depression Inventory Fast Screening; positive CG, positive expectation induction waitlist control group; standard CG, pure waitlist control group; TG, immediate treatment group; WBQ, Weekly Binges Questionnaire.

When exploring the differences between the trajectories of the two CGs during the waiting period, we observed no differences in linear trend lines between the standard CG and the positive CG, neither for WBQ (b = 0.040, SE = 0.067, t 103 = 0.60, p = 0.549, beta = 0.034, R 2 beta < 0.001), nor for BDI‐FS (b = 0.037, SE = 0.091, t 103 = 0.40, p = 0.689, beta = 0.017, R 2 beta < 0.001).

3.3.2. Temporal course during treatment and follow‐up (second study aim)

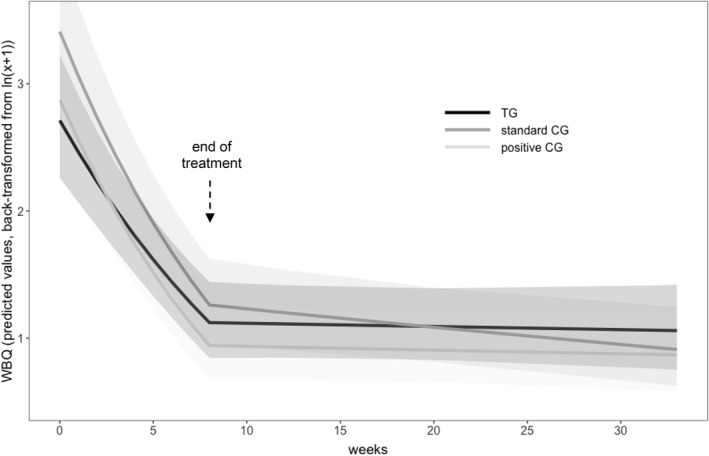

Figure 3 shows the temporal trend of the WBQ during active treatment and during follow‐up for each of the three groups (TG, CG1, and CG2). For the results presented below data of the three groups were combined. Significant linear decreases over time were found in all outcome variables during the active treatment phase: BQ (b = −0.080, SE = 0.011, t 571 = −7.14, p < 0.001, beta = −1.16, R 2 beta = 0.076), BDI‐FS (b = −0.076, SE = 0.013, t 578 = −5.68, p < 0.001, beta = −0.71, R 2 beta = 0.042), EDE‐Q (b = −0.125, SE = 0.021, t 83 = −5.87, p < 0.001, beta = −1.38, R 2 beta = 0.047), and WSAS (b = −0.090, SE = 0.024, t 83 = −3.76, p < 0.001, beta = −0.88, R 2 beta = 0.017). Explorative analyses showed that the linear trend estimates reported above did not differ among the three groups (TG, standard CG, and positive CG), except for EDE‐Q where the slope was more negative in positive CG during active treatment, compared to the other two groups (omnibus test among the three groups, p = 0.043, for EDE‐Q, and p > 0.08 for the other three outcomes).

FIGURE 3.

Temporal course of WBQ during active treatment and follow‐up in all groups (N = 63). Notes. TG = immediate treatment group; standard CG = pure waitlist control group; positive CG = positive expectation induction waitlist control; WBQ = weekly binges questionnaire. Shaded areas denote ±1 standard error

During the follow‐up phase (with three booster‐sessions within 6 months after the end of treatment), there was neither an improvement nor a deterioration for any of the outcomes WBQ (see Figure 3); (b = −0.003, SE = 0.003 t 571 = −1.00, p = 0.318, beta = −0.04, R 2 beta = 0.001), BDI‐FS (b = −0.002, SE = 0.006, t 578 = −0.34, p = 0.738, beta = −0.02, R 2 beta < 0.001), EDE‐Q (b = −0.008, SE = 0.008, t 83 = −1.05, p = 0.297, beta = −0.08, R 2 beta = 0.003), and WSAS (b = −0.007, SE = 0.008, t 578 = −0.88, p = 0.382, beta = −0.06, R 2 beta = 0.002). As for the active treatment phase, explorative analyses showed that the linear trend estimates reported for the follow‐up period did not differ among the three groups (TG, standard CG, and positive CG), except for WSAS where the slope was more positive during follow‐up in TG compared to the other two groups (omnibus test among the three groups, p = 0.048 for WSAS, and p > 0.12 for the other three outcomes).

4. DISCUSSION

Evidence‐based GSH programs are recommended as first line treatment in a stepped care approach to BED (AWMF, 2019; NICE, 2017). Following this recommendation, the present study investigated the effects of a short internet‐based GSH program including only eight sessions called BED‐Online (Munsch et al., 2019).

The aim of this study was to evaluate this eight‐sessions therapy's acceptance and its short (8 weeks active treatment) and long‐term efficacy (6‐month follow‐up with three booster‐sessions) with respect to the number of binge‐eating episodes, to ED pathology, to depressive symptoms, and to the level of psychosocial functioning. Efficacy was first evaluated by contrasting the temporal course of binge‐eating and depressive symptoms during the first 4 weeks of treatment with two combined waitlist conditions across the same time period. We further explored for the first time, potential beneficial effects of a waiting period with positive expectation induction prior to a disorder‐specific treatment relative to a pure waiting period on binge‐eating and depressive symptoms.

BED‐Online proved high treatment satisfaction in completers with values slightly above 8 on a scale between 0 and 10. Dropout rates were 27% during active treatment and an additional 9.5% during follow‐up and did not differ between the immediate TG and the two combined CGs. The rate of prematurely treatment termination during the active treatment phase was comparable to estimates from internet‐based treatments that did not include a face‐to‐face contact (24% on average), as summarized in the review by Aardoom et al. (2013). The dropout rates in our study were lower than in other GSH programs (37%) as shown in the meta‐analysis of Linardon et al. (2018). Including post‐treatment and follow‐up measures, with 36.5%, BED‐Online had a higher dropout rate compared to SalutBED (21.6%) and INTERBED (23.6%) (Carrard, Crepin, Rouget, Lam, Van der Linden, et al., 2011; de Zwaan et al., 2017), but a lower dropout rate compared to other studies applying an internet‐based GSH with values ranging between 27% and 50% (Carter et al., 2020; Hildebrandt et al., 2020; Jensen et al., 2020). The dropout rates in our study might be explained by the fact that BED‐Online did include a telephone contact at the beginning and weekly e‐mail contacts with a therapist, but no face‐to‐face contacts as in some other studies (e.g., Carrard, Crepin, Rouget, Lam, Golay, et al., 2011; Jensen et al., 2020).

In contrast to the comparably high dropout rates during the active treatment phase, in our study, the dropout rate of 9.5% during the follow‐up period was lower than the mean level of 29% reported in a review by Aardoom et al. (2013). This may be due to the implementation of three booster sessions during the 6‐month follow‐up period in BED‐Online. Still, previous studies of our research group, evaluating the equivalent CBT manual in a face‐to‐face group setting, resulted in lower dropout rates of 13% (Schlup et al., 2009) and of 23% in the book‐based and email‐supported GSH of Wyssen et al. (2019) and that therefore a restriction of direct contact might play a role. Future studies should improve the understanding of predictors of dropouts in GSH programs, as none of the potential factors influencing dropouts such as age, sex, or pre‐treatment psychopathology turned out to be of relevance in this study (Berger et al., 2018; Karyotaki et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2017). Lower adherence of patients (i.e., engagement in the program such as time spent in a session, written exchange with therapist, doing homework) predicted dropouts in an internet‐based GSH program for BED and therefore adherence needs to be monitored and fostered during the program in the future (Puls et al., 2020).

The comparison between the first 4 weeks of active treatment in the immediate TG and the corresponding waiting time in the combined CGs led to three insights: First, weekly binge‐eating episodes (WBQ) decreased from 4.05 to 2.35 in the TG (whereas in the combined CGs, WBQ remained more or less the same during the waiting period of same length), which equals a 42% reduction. This result supports the efficacy of the GSH program of Munsch et al. (2019) as an internet‐based intervention ‘BED‐Online’ including disorder‐specific interventions to cope with core symptoms of BED early in treatment.

Second, the temporal linear trends between the two CGs during the waiting period did not differ. As we did not test, whether positive expectation increased after the intervention, based on our findings we can only conclude that waiting did not decrease the frequency of binge‐eating episodes, independently of whether positive expectations were induced or not, while participating in the immediate TG led to an important reduction of binge‐eating during the first 4 weeks of treatment. So far, there is preliminary evidence that interventions to induce hope for a positive treatment outcome improve treatment effects (Constantino et al., 2012). Future studies might investigate whether frequency and type (e.g., face‐to‐face meetings vs. emails as in our study) of positive expectations induction may alter treatment effect. Nevertheless, based on our findings we assume that specific CBT interventions (such as understanding the causes and learning specific strategies to cope with binge‐eating) are more likely to lead to a decrease in the number of binge‐eating episodes than the transfer of information about expected positive treatment effects.

Third, depressive symptoms (BDI‐FS) did not decrease during the first 4 weeks of treatment in the immediate TG but improved till the end of the active treatment in all three groups, which is in line with other internet‐based and face‐to‐face studies where depressive symptoms improved after BED specific treatment (e.g., Striegel‐Moore et al., 2010). If replicated in larger studies, investigating changes in an early phase of treatment, the ‘delayed’ reduction of depressive symptoms compared to the more rapidly appearing reduction of binge‐eating might indicate a priority of processes in that an initial reduction of core BED‐symptoms may pave the way for a subsequent favourable course of depressive symptoms.

BED‐Online proved to be efficacious during the active treatment of only 8 weeks regarding all primary and secondary outcomes with high effect sizes (beta values in the range 0.71–1.38). Our results are furthermore favourable than a recent meta‐analysis that reveals efficacy of internet‐based programs for BED, but with lower effect sizes ranging from 0.31 to 0.32 for binge‐eating and negative affect (Melioli et al., 2016). None of those interventions had used such a short treatment period using an RCT design to assess therapy efficacy. Furthermore, individuals functioning at work, at home and at a social level improved, which might be seen as a correlate of clinical meaningfulness (Jensen & Corralejo, 2017) and needs to be considered as highly relevant for patients reducing high subject burden and impaired psychosocial functioning (e.g., Agh et al., 2015; Rieger et al., 2005). All three groups (immediate TG, pure CG, and positive expectation waitlist CG) exhibited comparable improvements with the onset of the active treatment, including subsequent stabilization during follow‐up. Exceptions concerned stronger improvements in EDE‐Q (ED pathology) in positive CG (waitlist CG with positive expectation induction) during active treatment, and stronger deterioration in WSAS (level of psychosocial functioning) during follow‐up in the TG, compared to the respective two other groups. These two effects which were preliminary since they were both based on exploratory analyses, were in addition of limited size and could not be interpreted in a meaningful way. Of note that no corrections for multiple testing were applied (Rothman, 1990).

Abstainer rates at post‐treatment (18%) and at 6‐month follow‐up (38%) in the present internet‐based GSH program were comparable to our recent book‐ and e‐mail‐based GSH program (abstainer rate of 15% at post‐treatment and of 47% at 6‐month follow‐up) (Wyssen et al., 2019), but lower than in a previous study applying the same manualized treatment in a face‐to‐face group setting (abstainer rate of 39% at post‐treatment) (Schlup et al., 2009). Post‐treatment abstainer rates in our study were comparable to other internet‐based interventions for eating disorders, showing abstainer rates of 10%–45% at post‐treatment and 15%–55% at follow‐up. However, in comparison with other GSH internet‐based programs such as INTERBED or SalutBED, abstainer rates in this study were lower which can be attributed to the shorter treatment duration in our study, especially as they caught up with time and were comparable at 6‐month follow‐up (INTERBED post‐treatment: 36%, 6‐month follow‐up: 38%; SalutBED post‐treatment: 35%, 6‐month follow‐up: 43%), while age range and symptom severity at pre‐treatment were similar. Further studies will be needed to directly compare face‐to‐face treatments with e‐mail and internet‐based treatments of different length in order to evaluate non‐inferiority of different approaches (Wagner et al., 2014).

The present RCT adds to the evidence on treatment efficacy of internet‐based treatments for BED with different treatment durations. The relatively short treatment duration of BED‐Online might represent an advantage. Nevertheless, the weekly efforts to guide the patients through the program were high in BED‐Online, and it would rise false expectations, if these first positive effects are interpreted in favour of an increased cost‐effectiveness of this internet‐based treatment option. Patients' narrative feedback revealed that the structured but still individualized content of the guidance of the therapist, who continuously motivated and validated them for their efforts, was appreciated. More research is needed with respect to the education and experience levels of the therapists, their expressive writing skills, and their ability to establish complementary and need‐oriented relationships with the patient in internet‐based treatments (Linardon et al., 2018; Sucala et al., 2012; Wilson & Zandberg, 2012). Beintner et al. (2014) reported results in favour of more experienced therapists regarding the outcome in a CBT‐GSH for BED.

Our study findings must be seen against the background of several limitations. The sample size was relatively small, resulting in limited power to detect effects among the groups. A potentially reduced generalizability of the results may arise from the inclusion of predominantly women of Swiss nationality. Moreover, participants following additional medical or psychotherapeutic treatments were not excluded, which might influence the results. Despite offering regular guidance, there was a considerable but comparable dropout rate in our RCT to other internet‐based treatments. We tested multiple reasons for dropouts (group, age, sex and pre‐treatment binge‐eating episodes, depressive symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and ED pathology) and did not find differences between participants adhering and those preliminarily terminating treatment. Further, there was no manipulation check considered in this study to assess the positive expectation induction.

In the future, interventions to reduce dropouts and studies to understand predictors of outcome, potential moderators or mediators in internet‐based treatment offers for BED should be investigated. Recent efforts from the field of human‐computer interaction towards user‐induced adaptation in order to personalize the content or alerts of the therapy according to the patient needs (Dumas et al., 2012) have the potential to contribute to increased efficacy and compliance. Additional integration of new technologies to facilitate the implementation of the new learnt strategies into the patient's life could potentially help to improve efficacy. During further development, additional modules, for example, to train emotion regulation could also be added for non‐responders as previous research has underlined the benefit of such trainings in anxiety or depressive disorders (Ehring et al., 2008).

To conclude, our program has proven high efficacy in a shorter duration than existing programs for BED and is only the second program available in German language. Temporal trends using a discontinuous model and dropout rates were investigated in detail and the role of positive expectation was assessed for the first time. Active and disorder specific treatment were not influenced by our efforts to increase positive expectations towards the upcoming treatment via email contacts with the patients in the corresponding waitlist group. The overall positive evaluation of the BED‐Online program adds to increased accessibility of evidence‐based treatments, even though implementation and dissemination still require improvements (Bauer et al., 2019). The current COVID‐19 pandemic underlines the necessity of the translation of effective face‐to‐face treatments to internet‐based GSH treatments and their dissemination (Bauer et al., 2019). Moreover, the potential of internet‐based treatment studies to continue recruiting and examining larger samples will foster a more fine‐grained research on potential moderators and mediators which will specify etiological models and improve treatment effects.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CLINICAL TRIALS REGISTRATION

German Clinical Trials Register: DRKS00012355. Date of registration: 14.09.2017. https://www.drks.de/drks_web/navigate.do?navigationId=trial.HTML&TRIAL_ID=DRKS00012355

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Swiss Anorexia Nervosa Foundation (project no. 52‐15) for supporting this project. Moreover, we would like to thank the participating patients and psychotherapist for trusting us with the scientific analysis of their psychotherapeutic work. We thank Master and Bachelor students at the University of Fribourg who helped with recruitment and study procedure. We thank the student Johannes Walpert for supporting the preparation of the manuscript.

Open Access Funding provided by Universite de Fribourg.

Wyssen, A. , Meyer, A. H. , Messerli‐Bürgy, N. , Forrer, F. , Vanhulst, P. , Lalanne, D. , & Munsch, S. (2021). BED‐online: Acceptance and efficacy of an internet‐based treatment for binge‐eating disorder: A randomized clinical trial including waitlist conditions. European Eating Disorders Review, 29(6), 937–954. 10.1002/erv.2856

REFERENCES

- Aardoom, J. J. , Dingemans, A. E. , Spinhoven, P. , & Van Furth, E. F. (2013). Treating eating disorders over the internet: A systematic review and future research directions. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(6), 539–552. 10.1002/eat.22135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agh, T. , Kovacs, G. , Pawaskar, M. , Supina, D. , Inotai, A. , & Voko, Z. (2015). Epidemiology, health‐related quality of life and economic burden of binge eating disorder: A systematic literature review. Eating and Weight Disorders, 20(1), 1–12. 10.1007/s40519-014-0173-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- AWMF . (2019). S3‐Leitlinie: Diagnostik und Therapie der Essstörungen. Retrieved from https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/051‐026.html, AWMF Online https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/051‐026.html [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, S. , Bilic, S. , Ozer, F. , & Moessner, M. (2019). Dissemination of an internet‐based program for the prevention and early intervention in eating disorders. Zeitschrift für Kinder‐ und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 48(1), 1–8. 10.1024/1422-4917/a000662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T. , Brown, G. K. , & Steer, R. A. (2013). Deutsche Bearbeitung von Sören Kliem & Elmar Brähler. Pearson Assessment.Beck‐depressions‐inventar‐FS (BDI‐FS) [Google Scholar]

- Beintner, I. , Jacobi, C. , & Schmidt, U. H. (2014). Participation and outcome in manualized self‐help for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder—a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(2), 158–176. 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, K. C. , Peterson, C. B. , Frazier, P. , & Crow, S. J. (2012). Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorder examination and eating disorder examination‐questionnaire: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(3), 428–438. 10.1002/eat.20931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, T. , Krieger, T. , Sude, K. , Meyer, B. , & Maercker, A. (2018). Evaluating an e‐mental health program (‘deprexis’) as adjunctive treatment tool in psychotherapy for depression: Results of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 455–462. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauhardt, A. , de Zwaan, M. , Herpertz, S. , Zipfel, S. , Svaldi, J. , Friederich, H.‐C. , & Hilbert, A. (2014). Therapist adherence in individual cognitive‐behavioral therapy for binge‐eating disorder: Assessment, course, and predictors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 61, 55–60. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrard, I. , Crepin, C. , Rouget, P. , Lam, T. , Golay, A. , & Van der Linden, M. (2011). Randomised controlled trial of a guided self‐help treatment on the Internet for binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(8), 482–491. 10.1016/j.brat.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrard, I. , Crepin, C. , Rouget, P. , Lam, T. , Van der Linden, M. , & Golay, A. (2011). Acceptance and efficacy of a guided internet self‐help treatment program for obese patients with binge eating disorder. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 7, 8–18. 10.2174/1745017901107010008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, J. C. , Kenny, T. E. , Singleton, C. , Van Wijk, M. , & Heath, O. (2020). Dialectical behavior therapy self‐help for binge‐eating disorder: A randomized controlled study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(3), 451–460. 10.1002/eat.23208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, M. J. , Ametrano, R. M. , & Greenberg, R. P. (2012). Clinician interventions and participant characteristics that foster adaptive patient expectations for psychotherapy and psychotherapeutic change. Psychotherapy, 49(4), 557–569. 10.1037/a0029440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, M. J. , Arnkoff, D. B. , Glass, C. R. , Ametrano, R. M. , & Smith, J. Z. (2011). Expectations. Journal of clinical psychology, 67(2), 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwaan, M. (2001). Binge eating disorder and obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 25(1), S51–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwaan, M. , Herpertz, S. , Zipfel, S. , Svaldi, J. , Friederich, H.‐C. , Schmidt, F. , Mayr, A. , Lam, T. , Schade‐Brittinger, C. , & Hilbert, A. (2017). Effect of internet‐based guided self‐help vs individual face‐to‐face treatment on full or subsyndromal binge eating disorder in overweight or obese patients: The interbed randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(10), 987–995. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwaan, M. , Herpertz, S. , Zipfel, S. , Tuschen‐Caffier, B. , Friederich, H. C. , Schmidt, F. , Gefeller, O. , Mayr, A. , Lam, T. , Schade‐Brittinger, C. , & Hilbert, A. (2012). INTERBED: Internet‐based guided self‐help for overweight and obese patients with full or subsyndromal binge eating disorder. A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Trials, 13, 220. 10.1186/1745-6215-13-220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dölemeyer, R. , Tietjen, A. , Kersting, A. , & Wagner, B. (2013). Internet‐based interventions for eating disorders in adults: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 207. 10.1186/1471-244X-13-207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, B. , Signer, B. , & Lalanne, D. (2012). Fusion in multimodal interactive systems: An HMM‐based algorithm for user‐induced adaptation. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 4th ACM SIGCHI symposium on Engineering Interactive Computing Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Ehring, T. , Fischer, S. , Schnülle, J. , Bösterling, A. , & Tuschen‐Caffier, B. (2008). Characteristics of emotion regulation in recovered depressed versus never depressed individuals. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(7), 1574–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G. (1995). Overcoming binge eating. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, S. , Meyer, A. H. , Dremmel, D. , Schlup, B. , & Munsch, S. (2014). Short‐term cognitive‐behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder: Long‐term efficacy and predictors of long‐term treatment success. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 36‐42. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger, C. , Meyer, A. H. , Wampold, B. E. , Gassmann, D. , Messerli‐Bürgy, N. , & Munsch, S. (2011). Predicting premature termination within a randomized controlled trial for binge‐eating patients. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 716–725. 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi, A. , Odeberg, J. , Gustafsson, S. , Råstam, M. , Brolund, A. , Pettersson, A. , & Parling, T. (2018). Psychological, pharmacological, and combined treatments for binge eating disorder: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. PeerJ, 6, e5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, R. P. , Constantino, M. J. , & Bruce, N. (2006). Are patient expectations still relevant for psychotherapy process and outcome? Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 657–678. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo, C. M. , & Masheb, R. M. (2005). A randomized controlled comparison of guided self‐help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(11), 1509–1525. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, L. M. , Granillo, M. T. , Jorm, A. F. , & Paxton, S. J. (2011). Unmet need for treatment in the eating disorders: A systematic review of eating disorder specific treatment seeking among community cases. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(5), 727–735. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, A. , De Zwaan, M. , & Braehler, E. (2012). How frequent are eating disturbances in the population? Norms of the eating disorder examination‐questionnaire. PloS One, 7(1), e29125. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, A. , Petroff, D. , Herpertz, S. , Pietrowsky, R. , Tuschen‐Caffier, B. , Vocks, S. , & Schmidt, R. (2019). Meta‐analysis of the efficacy of psychological and medical treatments for binge‐eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(1), 91–105. 10.1037/ccp0000358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, A. , & Tuschen‐Caffier, B. (2016). Eating disorder examination‐questionnaire: Deutschsprachige Übersetzung. Verlag für Psychotherapie. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt, T. , Michaeledes, A. , Mayhew, M. , Greif, R. , Sysko, R. , Toro‐Ramos, T. , & DeBar, L. (2020). Randomized controlled trial comparing health coach‐delivered smartphone‐guided self‐help with standard care for adults with binge eating. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(2), 134–142. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox, J. , Moerbeek, M. , & Van de Schoot, R. (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Iacovino, J. M. , Gredysa, D. M. , Altman, M. , & Wilfley, D. E. (2012). Psychological treatments for binge eating disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14(4), 432–446. 10.1007/s11920-012-0277-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, B. (2017). r2glmm: Computes R squared for mixed (multilevel) models. R package version 0.1.2. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R‐project.org/package=r2glmm

- Jensen, E. S. , Linnet, J. , Holmberg, T. T. , Tarp, K. , Nielsen, J. H. , & Lichtenstein, M. B. (2020). Effectiveness of internet‐based guided self‐help for binge‐eating disorder and characteristics of completers versus noncompleters. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(12), 2026–2031. 10.1002/eat.23384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, S. A. , & Corralejo, S. M. (2017). Measurement Issues: Large effect sizes do not mean most people get better–clinical significance and the importance of individual results. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 22(3), 163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyotaki, E. , Kleiboer, A. , Smit, F. , Turner, D. T. , Pastor, A. M. , Andersson, G. , Berger, T. , Botella, C. , Breton, J. M. , Carlbring, P. , Christensen, H. , de Graaf, E. , Griffiths, K. , Donker, T. , Farrer, L. , Huibers, M. J. H. , Lenndin, J. , Mackinnon, A. , Meyer, B. , … Cuijpers, P. (2015). Predictors of treatment dropout in self‐guided web‐based interventions for depression: An ‘individual patient data’ meta‐analysis. Psychological Medicine, 45(13), 2717–2726. 10.1017/S0033291715000665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass, A. E. , Kolko, R. P. , & Wilfley, D. E. (2013). Psychological treatments for eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 26(6), 549–555. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328365a30e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keski‐Rahkonen, A. , & Mustelin, L. (2016). Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: Prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(6), 340–345. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , Berglund, P. A. , Chiu, W. T. , Deitz, A. C. , Hudson, J. I. , Shahly, V. , Aguilar‐Gaxiola, S. , Alonso, J. , Angermeyer, M. C. , Benjet, C. , Bruffaerts, R. , de Girolamo, G. , de Graaf, R. , Maria Haro, J. , Kovess‐Masfety, V. , O’Neill, S. , Posada‐Villa, J. , Sasu, C. , Scott, K. , … Xavier, M. (2013). The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health surveys. Biological Psychiatry, 73(9), 904–914. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliem, S. , Mößle, T. , Zenger, M. , & Braehler, E. (2014). Reliability and validity of the beck depression inventory‐fast screen for medical patients in the general German population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 156, 236–239. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachin, J. M. , Matts, J. P. , & Wei, L. J. (1988). Randomization in clinical trials: Conclusions and recommendations. Controlled Clinical Trials, 9(4), 365–374. 10.1016/0197-2456(88)90049-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, P. (2008). Handling drop‐out in longitudinal clinical trials: A comparison of the LOCF and MMRM approaches. Pharmaceutical Statistics, 7(2), 93–106. 10.1002/pst.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon, J. , Hindle, A. , & Brennan, L. (2018). Dropout from cognitive‐behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A meta‐analysis of randomized, controlled trials. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(5), 381–391. 10.1002/eat.22850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margraf, J. , & Cwik, J. C. (2017). Mini‐DIPS Open Access: Diagnostisches Kurzinterview bei psychischen Störungen. Forschungs‐ und Behandlungszentrum für psychische Gesundheit, Ruhr‐Universität Bochum. [Google Scholar]

- Melioli, T. , Bauer, S. , Franko, D. L. , Moessner, M. , Ozer, F. , Chabrol, H. , & Rodgers, R. F. (2016). Reducing eating disorder symptoms and risk factors using the internet: A meta‐analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(1), 19–31. 10.1002/eat.22477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moessner, M. , Minarik, C. , Ozer, F. , & Bauer, S. (2016). Effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of school‐based dissemination strategies of an internet‐based program for the prevention and early intervention in eating disorders: A randomized trial. Prevention Science, 17(3), 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt, J. C. , Marks, I. M. , Shear, M. K. , & Greist, J. H. (2002). The work and social adjustment scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 461–464. 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch, S. , Biedert, E. , Meyer, A. , Michael, T. , Schlup, B. , Tuch, A. , & Margraf, J. (2007). A randomized comparison of cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss treatment for overweight individuals with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(2), 102‐113. Doi 10.1002/Eat.20350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch, S. , Meyer, A. H. , & Biedert, E. (2012). Efficacy and predictors of long‐term treatment success for cognitive‐behavioral treatment and behavioral weight‐loss‐treatment in overweight individuals with binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(12), 775–785. 10.1016/j.brat.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch, S. , Meyer, A. H. , Milenkovic, N. , Schlup, B. , Margraf, J. , & Wilhelm, F. H. (2009). Ecological momentary assessment to evaluate cognitive‐behavioral treatment for binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42(7), 648–657. 10.1002/eat.20657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch, S. , Wyssen, A. , & Biedert, E. (2018). Binge eating – Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie bei Essanfällen (d., vollständig überarbeitete auflage ed.). Beltz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Munsch, S. , Wyssen, A. , Vanhulst, P. , Lalanne, D. , Steinemann, S. T. , & Tuch, A. (2019). Binge‐eating disorder treatment goes online–feasibility, usability, and treatment outcome of an internet‐based treatment for binge‐eating disorder: Study protocol for a three‐arm randomized controlled trial including an immediate treatment, a waitlist, and a placebo control group. Trials, 20(1), 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R. , Straebler, S. , Cooper, Z. , & Fairburn, C. G. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 33(3), 611–627. 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, S. , & Schielzeth, H. (2013). A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed‐effects models. Methods in ecology and evolution, 4(2), 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- NICE . (2017). Eating disorders: Recognition and treatment. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69 [Google Scholar]

- Peerdeman, K. J. , van Laarhoven, A. I. M. , Keij, S. M. , Vase, L. , Rovers, M. M. , Peters, M. L. , & Evers, A. W. M. (2016). Relieving patients' pain with expectation interventions: A meta‐analysis. Pain, 157(6), 1179–1191. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C. B. , Engel, S. G. , Crosby, R. D. , Strauman, T. , Smith, T. L. , Klein, M. , Crow, S. J. , Mitchell, J. E. , Erickson, A. , Cao, L. , Bjorlie, K. , & Wonderlich, S. A. (2020). Comparing integrative cognitive‐affective therapy and guided self‐help cognitive‐behavioral therapy to treat binge‐eating disorder using standard and naturalistic momentary outcome measures: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(9), 1418–1427. 10.1002/eat.23324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, M. , & Anderson, P. L. (2012). Outcome expectancy as a predictor of treatment response in cognitive behavioral therapy for public speaking fears within social anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy, 49(2), 173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puls, H. C. , Schmidt, R. , Herpertz, S. , Zipfel, S. , Tuschen‐Caffier, B. , Friederich, H. C. , Gerlach, F. , Mayr, A. , Lam, T. , Schade‐Brittinger, C. , Zwaan, M. , & Hilbert, A. (2020). Adherence as a predictor of dropout in Internet‐based guided self‐help for adults with binge‐eating disorder and overweight or obesity. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(4), 555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]