Abstract

Background

To date, studies that have investigated the bonds between students and their institution have emphasized the importance of student–staff relationships. Measuring the quality of those relationships (i.e., relationship quality) appears to help with investigating the relational ties students have with their higher education institutions. Growing interest has arisen in further investigating relationship quality in higher education, as it might predict students’ involvement with the institution (e.g., student engagement and student loyalty). So far, most studies have used a cross‐sectional design, so that causality could not be determined.

Aims

The aim of this longitudinal study was twofold. First, we investigated the temporal ordering of the relation between the relationship quality dimensions of trust (in benevolence and honesty) and affect (satisfaction, affective commitment, and affective conflict). Second, we examined the ordering of the paths between relationship quality, student engagement, and student loyalty. Our objectives were to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship quality construct in higher education and its later outcomes.

Sample

Participants (N = 1649) were students from three Dutch higher education institutions who were studying in a technology economics or social sciences program.

Methods

Longitudinal data from two time points were used to evaluate two types of cross‐lagged panel models. In the first analysis, we could not assume measurement invariance for affective conflict over time. Therefore, we tested an alternative model without affective conflict, using the latent variables of trust and affect, the student engagement dimensions and student loyalty. In the second type of model, we investigated the manifest variables of relationship quality, student engagement, and student loyalty. The hypotheses were tested by evaluating simultaneous comparisons between estimates.

Results

Results indicated that the relation between relationship quality at Time 1 with student engagement and loyalty at Time 2 was stronger than the reverse ordering in the first model. In the second model, results indicated that cross‐lagged relations between trust in benevolence and trust in honesty at Time 1 and affective commitment, affective conflict, and satisfaction at Time 2 were more likely than the reverse ordering. Furthermore, cross‐lagged relations from relationship quality at Time 1 to student engagement and student loyalty at Time 2 also supported our hypothesis.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the existing higher education literature, indicating that students’ trust in the quality of their relationship with faculty/staff is essential for developing students’ affective commitment and satisfaction and for avoiding conflict over time. Second, relationship quality factors positively influence students’ engagement in their studies and their loyalty towards the institution. A relational approach to establishing (long‐lasting) bonds with students appears to be fruitful as an approach for educational psychologists and for practitioners’ guidance and strategies. Recommendations are made for future research to further examine relationship quality in higher education in Europe and beyond.

Keywords: cross‐lagged panel analysis, higher education, relationship quality, student engagement, student loyalty

Introduction

Recent studies in the field of education have demonstrated that improving and maintaining positive interpersonal relationships between students and teachers is essential (e.g., in a higher education context, see García‐Moya, Bunn, Jiménez‐Iglesias, Paniagua, & Brooks, 2019; Schlesinger, Cervera, & Pérez‐Cabañero, 2017; Xerri, Radford, & Shacklock, 2018; in a school context, see Pianta, Hamre, & Allen, 2012; Pöysä et al., 2019). Those relationships positively stimulate students’ academic and social development, including students’ engagement in their studies and student loyalty intentions (Bonet & Walters, 2016; Parsons & Taylor, 2011; Schaufeli, Martínez, Pinto, Salanova, & Bakker, 2002; Umbach & Wawrzynski, 2005). In turn, student loyalty intentions may result in positive student loyalty behaviour towards their university. An example of loyalty behaviour is positive word‐of‐mouth, which is a critical factor for higher education institutions’ continuity and growth (Snijders et al., 2019, Snijders et al., 2020; Farrow & Yuan, 2011; Hennig‐Thurau, Langer, & Hansen, 2001; Rojas‐Méndez, Vasquez‐Parraga, Kara, & Cerda‐Urrutia, 2009; Sung & Yang, 2008). Thus far, it has remained unclear how students’ relationships with the faculty and staff of their institution (i.e., relationship quality) develop over time and how relationship quality subsequently affects student outcomes in higher education (i.e., student engagement and loyalty; e.g., Cho & Auger, 2013; García‐Moya et al., 2019).

Educational researchers investigating student relationships have mainly focused on primary or secondary education (e.g., Roorda, Jak, Zee, Oort, & Koomen, 2017; Roorda, Koomen, Spilt, & Oort, 2011). Although their research findings are important for gaining insight into educational processes, the instruments used in these studies are not always applicable in all educational settings. Higher education differs from other educational contexts regarding students’ involvement and participation (Leenknecht, Snijders, Wijnia, Rikers, & Loyens, 2020). Education‐related interpersonal relationships within the primary or secondary school context are mainly formed between students and teachers (Roorda et al., 2011). However, the child–adult relationship in primary and secondary education becomes an adult–adult relationship in higher education (Hagenauer & Volet, 2014). Multiple frameworks are relevant for teacher–student relationships, such as self‐determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2008), which focuses on human motivation. However, in higher education, a student also builds relationships with other people within their higher education institution/university. Besides their teachers, students have multiple and sequential interactions with other representatives of their higher education institution, such as librarians, student psychologists, study counsellors, or other staff members. The interpersonal relationships resulting from those interactions form a focal point in the educational process. How students perceive these relational ties – through relationship quality – will affect their future interactions, attitudes, intentions, and behaviours or actions towards their university or higher education institution (Gibbs & Kharouf, 2020; Palmatier, 2008).

In general, relationship quality can be defined as the overall strength of a relationship (Roberts, Varki, & Brodie, 2003). Within the relationship quality construct, two aspects can be distinguished: trust and affect. In line with previous research drawn from the management literature, we believe that trust plays a central role in the relationship quality construct (Crosby, Evans, & Cowles, 1990; Hennig‐Thurau et al., 2001; Jiang, Shiu, Henneberg, & Naude, 2016; Morgan & Hunt, 1994) Without trust, there cannot be a relationship. Hence, trust can be seen as the foundation of a relationship’s strength that, in time, results in the affective relationship quality aspects of satisfaction and (strong) commitment and reduction in conflict (Castaldo, 2007), which are termed ‘affect’ in this study). One must also consider the environment and the relational depth (or intensity) and duration to understand the dynamics of the relationship quality construct. The work by Van Maele, Forsyth, and Van Houtte (2014), for instance, described the role of trust in school life and its importance to learning and teaching in a primary or secondary school context. However, to our knowledge, how students’ trust in their relationship with faculty and staff develops in higher education has been underexplored. Empirical research has emphasized the importance of students’ relationships, indicating that higher education institutions benefit from engaged and loyal students (Bowden, 2011), for example, through active participation in extracurricular activities or loyalty intentions and behaviour during or after enrolment. Other studies have also indicated that students’ perceptions of the quality of their relationship with the educational institution are positively associated with student engagement and student/alumni loyalty (e.g., Snijders et al., 2019, 2020). The relationship quality outcomes are of interest for educational psychologists and higher education institutions. However, previous studies in this field have mainly been cross‐sectional in nature (e.g., Snijders et al., 2020; Miller, Williams, & Silberstein, 2019; Schlesinger et al., 2017), which means that the directionality of the causal relations to indicate cause and effect cannot be determined. The role of trust in a higher education context has also, to our knowledge, rarely been examined. This study addressed these gaps.

Relationship quality

Previous educational psychology research primarily focused on student–teacher relationships (e.g., Košir & Tement, 2014; Roorda, Verschueren, Vancraeyveldt, Van Craeyevelt, & Colpin, 2014; Zee, Koomen, & Van der Veen, 2013). However, Snijders et al. (2018) demonstrated that relationship quality in higher education could be seen as a multidimensional construct, capturing students’ perceptions of the quality of their relationship with their educational faculty and staff. This study builds on relationship quality research by Snijders et al. (2019, 2020), where they used the relationship quality construct in higher education. Relationship quality consisted of five dimensions, based on students’ perceptions of their educational faculty and staff. These dimensions include trust in honesty and trust in benevolence (in this study, ‘trust’), and affective commitment, satisfaction, and affective conflict (in this study, ‘affect’).

Trust

Trust has been described in various ways, such as the confidence one has in a relationship and the belief that a trusted person or actor is reliable or has integrity (e.g., Bryk & Schneider, 2002; Tschannen‐Moran, 2014). Students’ trust in educational faculty and staff can be subdivided into trust in honesty and trust in benevolence (Snijders et al., 2018; Roberts et al., 2003). Trust in honesty refers to the confidence students have in a university’s credibility as expressed by its educational faculty and staff. Or in other words, it refers to students’ trust in educational faculty/staff's integrity and trustworthiness (i.e., reliability), the staff and faculty’s sincerity, and whether they will perform their roles effectively and reliably. Trust in benevolence in higher education includes the extent to which students believe faculty/staff are concerned about students’ welfare, have intentions and motives beneficial to them, and avoid acting in a way that will result in adverse outcomes for students (Snijders et al., 2018, 2019, 2020; Roberts et al., 2003). Students’ trust in educational faculty and staff’s benevolence is based on students’ perceptions of how faculty and staff respond to students’ questions, such as timely responses to email requests and feedback on assignments and grades (Snijders et al., 2020). For educational practitioners, it is important to think of how they respond to students. For instance, when students confide their problems, it is essential for them to feel that they can count on their educational faculty and staff. Based on commitment–trust theory (Morgan & Hunt, 1994), the factor of trust may lead to positive affect, in this case the affective relationship quality dimensions of commitment and satisfaction (Mohr & Speckman, 1994).

Affect

Affect can be further divided into affective commitment, satisfaction, and affective conflict. Affective commitment compels students’ feelings of belonging or connection to their educational faculty, staff, or institution. In other words, it is the feeling of having a connection or being emotionally attached and genuinely enjoying the relationship students experience with their educational faculty/staff. In general, commitment indicates a relationship’s health and is, therefore, part of the relationship quality construct (Roberts et al., 2003). In higher education, where there are multiple and sequential interactions between students and their educational faculty/staff, affective commitment might develop over time (Castaldo, 2007). In general, satisfaction is the ‘summary measure that provides an evaluation of the quality of all past interactions’ (Roberts et al., 2003, p. 174). Within this study, when we refer to satisfaction, we mean relationship satisfaction: students’ perceptions of their degree of satisfaction with the quality of their relationship with their educational faculty/staff. In other words, we tried to capture the cumulative satisfaction students perceived regarding their relationship with their educational faculty/staff, represented by students’ cognitive and affective evaluation based on their personal experiences across their time at the institution. Affective conflict is determined by students’ evaluations of their relationships with faculty/staff based on their perceived conflicts, such as irritation, frustration, or anger. It can be considered as the tension students experience due to the incompatibility of actual and desired responses from their educational faculty and staff (Snijders et al., 2020). For instance, students who experience conflict in their relationships (with teachers) attain lower achievement levels compared to students who have close, positive, and supportive relationships (Rimm‐Kaufman & Sandilos, 2010). Therefore, conflict reduction might also be necessary for the higher education context and the quality of the relations between students and their higher education institution.

Based on prior research on teacher–student relationships and the association between relationship quality and school outcomes (e.g., Culver, 2015), we assume that relationship quality positively affects student engagement and loyalty (e.g., Snijders et al., 2020; Bonet & Walters, 2016; Bowden, 2011; Hennig‐Thurau et al., 2001; Parsons & Taylor, 2011; Schaufeli et al., 2002; Umbach & Wawrzynski, 2005).

Student engagement

Recent studies conducted in elementary or secondary school (e.g., Engels et al., 2016; Lee, 2012; Manzuoli, Pineda‐Báez, & Vargas Sánchez, 2019; Nicholson & Putwain, 2020) considered student engagement to be a multidimensional construct consisting of emotional, cognitive, and behavioural dimensions (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004). In higher education, student engagement is considered crucial to achieving positive academic outcomes through students’ bonds with their university (Bowden, 2009; Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Sung & Yang, 2008). Student engagement has been widely theorized and researched (e.g., Kahu, 2013) and can be considered a broad concept (Farr‐Wharton, Charles, Keast, Woolcott, & Chamberlain, 2018) or be seen as a meta‐construct (Fredricks et al., 2004) that includes student engagement’s behavioural, cognitive, and emotional aspects. Although multiple definitions have been used in student engagement research in past years, the definition by Kuh (2001) helped to shape our conceptualization of student engagement. Student engagement can be considered to include a variety of constructs that measure both the time and energy students devote to educationally purposeful activities and how students perceive different facets of the institutional environment that facilitate and support their learning. Following the service management literature, where the quality of the relationship may positively affect engagement in term of the actor’s involvement within the process, within our study we, therefore, chose to apply the definition and measurement of student engagement by Schaufeli and Bakker (2003), because it concerns the students' involvement in their studies.

In our study, we adopted the definition by Schaufeli et al., (2002), in line with recent studies (e.g., Snijders et al., 2019, 2020; Farr‐Wharton et al., 2018) that focused on engagement as part of the student’s overall experience in higher education. Schaufeli and Bakker (2003) defined engagement as ‘a positive, fulfilling, work‐related state of mind that is characterized by vigour, dedication and absorption’ (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003, p. 4); see also Schaufeli et al., 2002; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006). Furthermore, ‘Vigour is characterized by high levels of energy and mental resilience while working, the willingness to invest effort in one's work, and persistence even in the face of difficulties’ (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003, p. 4). Dedication refers to ‘being strongly involved in one's work and experiencing a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, and challenge’ (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003, pp. 4‐5). Absorption is ‘characterised by being fully concentrated and happily engrossed in one's work, whereby time passes quickly, and one has difficulties detaching oneself from work’ (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003, p. 5).

Student loyalty

Student loyalty refers to the extent to which students feel connected to the institution and how this is expressed in their attitudes and behaviours (Helgesen & Nesset, 2007; Hennig‐Thurau et al., 2001). In higher education, attitude may refer to students’ (positive) feelings related to their faculty/staff and university. Student loyalty behaviour is expressed, for example, in (positive) recommendations from students about their educational faculty/staff and university, active participation in extracurricular activities, or loyalty intentions, and behaviour during or after their period of enrolment. Higher education institutions benefit from loyal and successful students (Helgesen & Nesset, 2007). Therefore, in the international literature on student behaviour, student loyalty is increasingly considered a critical measure of those institution’ growth or success (Rojas‐Méndez et al., 2009).

The educational psychology literature implies that high‐quality relationships with students result in positive academic outcomes. For instance, positive student–faculty interactions contribute to pedagogical objectives related to intellectual and personal student development, such as increased student motivation, engagement, social integration, and academic performance (Kim & Lundberg, 2016; Klem & Connell, 2004; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005), and may subsequently promote student retention and perseverance in achieving a degree (O'Keeffe, 2013; Vander Schee, 2008a, 2008b). Furthermore, when interpersonal relationships between students and their institution are perceived positively by students, students may develop a sense of belonging or (growing) connection to their institution (García‐Moya, Brooks, & Moreno, 2020; Kim & Lundberg, 2016).

In line with the services management literature, we place the student’s perceptions and attitudes at the centre of the educational experience. In services management research, a customer focus is essential, especially in high‐quality service delivery processes such as those occurring in higher education, where the services consist of frequent human interactions between students and their educational faculty and staff.

In summary, positive student–faculty relationships are vital because they can positively influence student outcomes, such as student engagement (Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005; Pianta et al., 2012) or a willingness to continue to interact and engage in the relationship within the educational service process (Bowden, 2011; Zeithaml, Bitner, Gremler, & Lovelock, 2009), as expressed in student and alumni loyalty, for example (Bowden, 2011). Therefore, a closer look is necessary at how students perceive interpersonal relationships with their educational faculty and staff and the associated outcomes. As a result, the value of investing in positive bonds between faculty/staff and their students could become more evident, if these relationships can contribute in a positive way to students' involvement during and after their time in higher education.

Present study

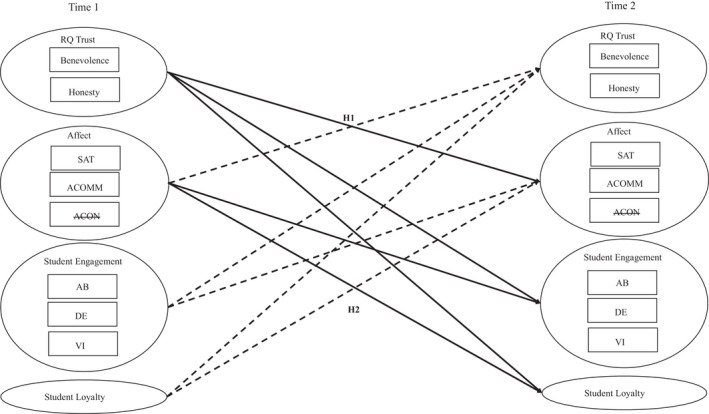

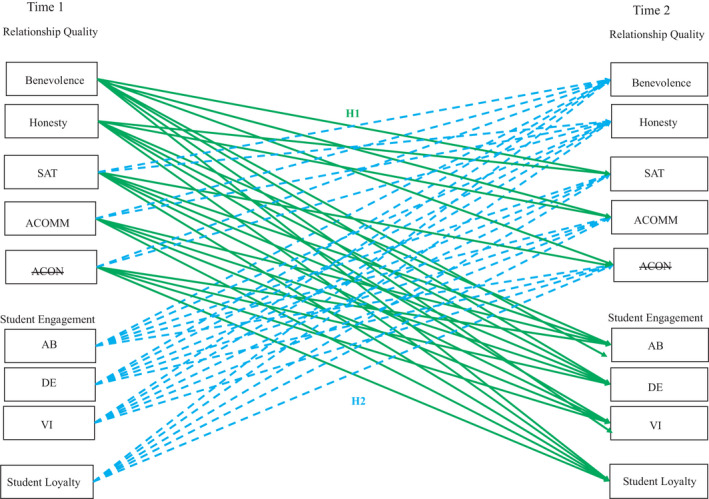

In this study, we applied a cross‐lagged panel analysis to longitudinal data fromtwo time points. The data were based on students’ questionnaire responses about relationship quality (Snijders et al., 2018; Roberts et al., 2003), student engagement (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003), and student loyalty (Hennig‐Thurau et al., 2001). The purpose was twofold: (1) to examine the ordering of the relations between the relationship quality factors of trust at Time 1 and affect at Time 2, and (2) to explore the strength and ordering of the relations between relationship quality (trust and affect), student engagement, and loyalty (see Figures 1 and 2). This study has practical implications for educational psychologists and practitioners who want to understand the relational ties between students and their institution.

Figure 1.

Cross‐Lagged Panel Model. Note. The model shows semi‐longitudinal relations between the relationship quality factors of trust (T1) and affect (T2: Hypothesis 1) and the relations between trust and affect (T1) and student engagement and student loyalty (T2; Hypothesis 2). Solid lines represent stronger cross‐lagged paths than dashed line paths. The model is a simplification of the total model analysed; all possible relations between T1 and T2 were examined, including correlations and residuals; however, for reasons of clarity, they were not shown in the model. RQ = Relationship Quality, SAT = Satisfaction, ACOMM = Affective Commitment, ACON = Affective Conflict; AB = Absorption, DE = Dedication, VI = Vigour. ACON was initially used in the first analysis and excluded from the following analyses due to measurement invariance issues

Figure 2.

Cross‐Lagged Panel Model. Note. The model shows semi‐longitudinal relations between relationship quality dimensions (T1) and relationship quality dimensions (T2), and the relations between relationship quality dimensions (T1) and student engagement (SE) dimensions and student loyalty (SL) (T2) (hypothesis 2). Solid lines represent stronger cross‐lagged paths than the dashed line paths. The model is a simplification of the total model analysed; all possible relations between T1 and T2 were examined, including correlations and residuals; however, for reasons of clarity, they were not shown in the model. SAT = Satisfaction, ACOMM = Affective Commitment, ACON = Affective Conflict; AB = Absorption, DE = Dedication, VI = Vigour. ACON was initially used in the first analysis and excluded from the following analyses due to measurement invariance issues

The first research question that guided this study was: Does trust provide the basis of the relationship quality construct in higher education, that is, does trust influence affect over time? The second was: Does relationship quality at the start of the year predict student engagement and loyalty in the second semester?

Based on prior research (Snijders et al., 2019, 2020; Hennig‐Thurau et al., 2001) and (interpersonal) trust literature (e.g., Castaldo, 2007; Lewicki, Tomlinson, & Gillespie, 2006), our first hypothesis (H1) was that over time, students’ trust would result in (higher) satisfaction and affective commitment and less affective conflict (see Figures 1 and 2). Furthermore, our second hypothesis (H2) was that relationship quality aspects might positively influence students’ engagement in their studies and their loyalty intentions, when students perceive high‐quality relationships with their educational faculty and staff (see Figures 1 and 2). In sum, this study’s purpose was to examine first the strength and directionality of the relations between the five relationship quality dimensions, and second, how the relationship quality dimensions are associated with student engagement and student loyalty over time.

In conformity with multiverse analysis (Steegen, Tuerlinckx, Gelman, & Vanpaemel, 2016), we evaluated two types of cross‐lagged panel models (CLPM): (1) on a higher level (i.e., latent relationship quality factors and a latent factor for engagement; see Figures (1) and (2) on a fine‐grained level (i.e., the manifest constructs, see Figure 2). In a multiverse analysis, multiple analyses are conducted on the same dataset using different researcher decisions (e.g., include versus exclude covariates, dichotomize versus non‐dichotomize variables) to reduce the researcher degrees of freedom. We use it in this article to demonstrate that the results were consistent across model choice (using a latent variable model and a manifest variable model). The following hypotheses were tested in these models:

Hypothesis 1

The relationship quality dimensions of trust in benevolence and honesty (Trust) at Time 1 have stronger relations with the relationship quality dimensions of affective commitment, satisfaction, and affective conflict (Affect) at Time 2 than the reciprocal lagged relations (i.e., the relations between Affect at Time 1 and Trust at Time 2). Hypothesis 2: Relationship quality (i.e., trust in benevolence, trust in honesty, affective commitment, satisfaction, and affective conflict) at Time 1 has a stronger relation with student engagement and student loyalty at Time 2 than the reciprocal lagged relations (i.e., the relations between student engagement and student loyalty at Time 1 and relationship quality dimensions at Time 2).

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were higher education students who were enrolled in a variety of programs in the fields of economics, social work, and technology (T1: n = 1031, Mage = 22.73 years, SD = 6.39; T2: n = 876, Mage = 22.42 years, SD = 5.59). The total sample consisted of 1649 students whose responses were collected at three universities of applied sciences located in the southwest part of the Netherlands (Institution 1 = 1203; Institution 2 = 291; Institution 3 = 155). In two consecutive years, the same survey was sent out to enrolled students twice per academic year (Measurements 1–4), during the fall (T1) and spring (T2) semesters. From the total sample (N = 1649), not all students filled out the questionnaires each time, or they did not completely finish the questionnaire. Therefore, we comprised the data. Measurements 1 and 3 (both conducted in the fall semester) were taken together to form Time 1, Measurements 2 and 4 (both conducted in the spring semester) were taken together to form Time 2. When students participated in both academic years, we only included the data from one academic year, based on the number of completed questionnaires. For example, if only one questionnaire was completed in year 1 (e.g., only Measurement 2) but two in year 2 (Measurements 3 and 4), the responses for year 2 were selected.

Descriptive statistics regarding participants’ gender and study year are included in the online supplemental materials (Table S1). Completing the online survey took approximately 15 min. Students were given a two‐month period to respond. A reminder was sent after a two‐ to four‐week period.

At each administration, participants were told that there were no (in)correct answers to the items, as long as the answers reflected their personal opinions. Participants were.

asked for informed consent; only participants who gave their permission to use their responses for research were included in this study and their data were treated anonymously. The institutions provided ethical approval for the organization of the study.

Measures

A survey instrument based on existing scales was used to measure relationship quality,

student engagement, and student loyalty. Items were translated and presented in Dutch. All survey items per construct and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Survey items per construct and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients

| Scales | Items | Cronbach's α | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | Time 2 | ||

| n = 1032 | n = 879 | ||

| Relationship quality a | |||

| Trust | |||

| Trust in benevolence |

My faculty/staff is concerned about my welfare. When I confide my problems to my faculty/staff, I know they will respond with understanding. I can count on my faculty/staff considering how their actions affect me. |

.88 | .85 |

| Trust in honesty |

My faculty/staff is honest about my problems. My faculty/staff has high integrity. My faculty/staff is trustworthy. |

.83 | .80 |

| Affect | |||

| Affective commitment |

I feel emotionally attached to my faculty/staff. I continue to interact with my faculty/staff because I like being associated with them. I continue to interact with my faculty/staff because I genuinely enjoy my relationship with them. |

.87 | .83 |

| Affective conflict |

I am angry with my faculty/staff. I am frustrated with my faculty/staff. I am annoyed with my faculty/staff. |

.90 | .89 |

| Satisfaction |

I am delighted with the performance of my faculty/staff. I am happy with my faculty/staff's performance. I am content with my faculty/staff's performance. |

.95 | .93 |

| Student engagement b | |||

| Absorption |

Times flies when I am studying. When I am studying, I forget everything else around me. I am immersed when I’m studying. |

.79 | .79 |

| Dedication |

I find the studying that I do full of meaning and purpose. My studying inspires me. I am proud of the studying that I do. |

.85 | .82 |

| Vigour |

At university, I feel bursting with energy. At university, I feel strong and vigorous. When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to school. |

.80 | .82 |

| Student loyalty c |

I'd recommend my course of studies to someone else. I'd recommend my university to someone else. I'm very interested in keeping in touch with ‘my faculty’. If I were faced with the same choice again, I'd still choose the same course of studies. If I were faced with the same choice again, I'd still choose the same university. |

.86 | .87 |

Adapted from Roberts et al., (2003), applied in higher education by Snijders et al. (2018, 2019, 2020); item responses: 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Adopted from UWES‐S, short version by Schaufeli and Bakker (2003); item responses: 1 (almost never/a few times a year or less) to 7 (always/every day).

Adopted from Hennig‐Thurau et al., (2001); item responses: 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Relationship quality

An existing relationship quality scale was used to measure relationship quality (Snijders et al., 2018, adapted from Roberts et al., 2003). Five relationship quality dimensions were used to measure the relationship quality construct in higher education with a 15‐item scale. Students had to indicate on a 7‐point Likert scale how much they agreed with the provided statements, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficients reported for trust in benevolence (.88, .85), trust in honesty (.83, .80), satisfaction (.95, .93), affective commitment (.87, .83), and affective conflict (.90, .89) showed good internal consistencies at Times 1 and 2, respectively.

Student engagement

Student engagement was measured with nine items from the Utrecht Work Engagement.

Scale‐Student version (UWES‐S‐short version; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003). Items were rated on a 7‐point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (almost never/a few times a year or less) to 7 (always/every day). Student engagement was divided into the subdimensions of absorption, dedication, and vigour. In this study, Cronbach’s alphas also showed good internal consistencies (absorption .79, .79; dedication .85, .82, and vigour .80, .82) at Times 1 and 2, respectively.

Student loyalty

Student loyalty was measured by an existing scale with five items, from Hennig‐Thurau et al., (2001). On a 7‐point Likert scale, statements had to be rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In this study, Cronbach’s alphas showed good reliability: .86 at Time 1 and .87 at Time 2.

Additional questions

An open‐ended question at the end was included to allow students to express their thoughts about the questionnaire. Students were also asked some general questions related to their age,gender, ethnicity, study year, and educational program/major.

Analyses

First, we tested whether the missing data in our sample were missing completely at random using Little's MCAR test (see Little, 1988). Based on this test, χ2(10) = 10.326, p =.412, we concluded that the missing values pattern did not depend on the data values;that is, the complete‐cases data were a random subset. Therefore, we used complete‐cases data.

Second, the data were used to evaluate two cross‐lagged panel models (CLPM). Since we had only two time points, using random intercept cross‐lagged panel model analysis was impossible (Hamaker, Kuiper, & Grasman, 2015). In Model 1, we considered relationship quality as a higher‐order construct consisting of two latent factors. Furthermore, a latent factor for engagement was included, for which the sum scores of vigour, dedication, and absorption were used as indicators. Finally, student loyalty was incorporated as a manifest variable. Both hypotheses were tested in this model. To evaluate Hypothesis 1, we examined the strength and ordering of the relations between the relationship quality dimensions. We investigated the paths between trust at Time 1 and the ‘resulting’ affective relationship quality dimensions of commitment, conflict, and satisfaction at Time 2.

The primary latent factor is trust, for which trust in honesty and trust in benevolence are used as indicators. The second latent factor is affect, which consists of the relationship quality dimensions of satisfaction, affective commitment, and (lack of) affective conflict.

To test Hypothesis 2, we investigated whether the paths from trust and affect (Time 1) to engagement and loyalty (Time 2) were stronger than from engagement and loyalty (Time 1) to trust and affect (Time 2).

Model 2 included the five manifest constructs for relationship quality, the three student engagement manifest constructs, and student loyalty. To evaluate Hypothesis 1, we tested whether the combined paths from trust in honesty and benevolence (Time 1) to affective commitment, affective conflict, and satisfaction (Time 2) were stronger than the combined paths from the affective constructs (Time 1) to trust in honesty and benevolence (Time 2). To examine Hypothesis 2, we examined whether the sequence in which the combined paths from the relationship quality constructs (Time 1) go to engagement and loyalty (Time 2) was more likely than the other way around, in which engagement and loyalty (Time 1) lead to the relationship quality constructs (Time 2).

This study’s analysis was conducted using the lavaan package for structural equation modelling in R (R Core Team, 2012), in line with previous research in the field of educational psychology that has examined cross‐lagged relations (e.g., Burns, Crisp, & Burns, 2020; Košir & Tement, 2014; Morinaj & Hascher, 2019; Nicholson & Putwain, 2020; Sánchez‐Álvarez, Extremera, & Fernández‐Berrocal, 2019). The R code for the CLPM analyses, including the two types of evaluation of the hypotheses using the GORICA function, and supplemental materials, can be downloaded (https://github.com/rebeccakuiper/GORICA_in_CLPM).

The specific hypothesized orderings of cross‐lagged parameters cannot be tested with straightforward hypothesis testing. However, they can easily be evaluated with (order‐constrained) model selection. We used GORICA weights (Altinisik et al., 2018; Kuiper, 2020; Kuiper, Hoijtink, & Silvapulle, 2011), an Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1978) type of criterion, which can evaluate order‐restricted, theory‐based hypotheses as in this study. We evaluated each of our hypotheses against its complement, representing all possible orderings (i.e., all other possible hypotheses; Vanbrabant, Van Loey, & Kuiper, 2020). The resulting GORICA weights quantify the support for the hypotheses and their complements (cf. Akaike, 1978; Burnham & Anderson, 2002; Wagenmakers & Farrell, 2004). To calculate these GORICA weights, we used the goric function (Vanbrabant & Kuiper, 2020) of the restriktor R package (Vanbrabant & Rosseel, 2020).

Results

Descriptive statistics

In Table 2, means and standard deviations of the constructs at Times 1 and 2 are shown. The sample sizes differed between Times 1 and 2 (i.e., n at T1 = 1031 and n at T2 = 876). The means and standard deviations for relationship quality dimensions, student engagement dimensions, student loyalty at the two time points did not seem to differ much from each other.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations (SD) of Constructs

| Time 1 | Time 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean a | SD | n | Mean a | SD | |

| Relationship quality dimensions | ||||||

| Trust in benevolence | 1024 | 15.62 | 3.76 | 864 | 14.97 | 3.76 |

| Trust in honesty | 1024 | 15.79 | 3.24 | 864 | 15.09 | 3.27 |

| Satisfaction | 1024 | 14.70 | 3.85 | 864 | 14.33 | 3.92 |

| Affective commitment | 1024 | 14.96 | 4.07 | 864 | 14.41 | 3.94 |

| Affective conflict | 998 | 14.37 | 4.34 | 864 | 15.06 | 4.14 |

| Student engagement dimensions | ||||||

| Absorption | 998 | 12.96 | 3.78 | 798 | 12.41 | 3.81 |

| Dedication | 998 | 16.00 | 3.57 | 798 | 15.51 | 3.47 |

| Vigour | 998 | 12.86 | 3.62 | 798 | 12.32 | 3.59 |

| Student loyalty | 998 | 26.01 | 6.41 | 798 | 25.36 | 6.63 |

The means are based on the sum scores of variables (relationship quality dimensions range: 3–21; student engagement dimensions range: 3–21; student loyalty range: 5–35).

CLPM with latent factors for trust and affect

Before we evaluated the hypotheses, we first checked for measurement invariance to examine whether the same constructs were measured over both time points (i.e., that the constructs had the same meaning across measurement occasions, see Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). To that end, a model without constraints was compared with a model where the factor loadings were constrained (i.e., weak measurement invariance) using the χ2 difference test (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Fit Indices for Models 1a & b

| Model | χ2 | df | p Δχ2 | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | |||||||

| Unconstrained model | 885.53 | 114 | |||||

| Weak factorial invariance | 865.45 | 109 | .001 | ||||

| Model 1b | |||||||

| Configural invariance | 715.87 | 78 | ‐ | ||||

| Weak factorial invariance | 721.02 | 82 | .272 | ||||

| Strong factorial invariance | 725.49 | 84 | .107 | .07 | .05 | .94 | .92 |

RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker‐Lewis index.

First, we evaluated both hypotheses in a model where the latent relationship quality constructs for trust and affect were included (i.e., Model 1a). Because the χ2 difference test was statistically significant (see Table 3), we could not assume weak measurement invariance, although it has been argued that the criteria for testing measurement invariance may be too strict (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2013). Based on the comparisons of standardized factor loadings at Times 1 and 2, affective conflict measures differed over time (see also Table 3).

Therefore, we tested a new model in which affective conflict was excluded (i.e., Model 1b). When affective conflict was removed from the analyses, we could assume strong measurement invariance, since the χ2 difference test was not statistically significant (see Table 3), indicating that the same constructs were measured over time. Both hypotheses were evaluated using Model 1b. Results indicated that order‐restricted hypothesis 1 had 1.7 times more support than its complement. This means that there is support for the hypothesis that the relation between trust at Time 1 and affect at Time 2 is stronger than the reverse ordering. Furthermore, order‐restricted hypothesis 2 had 1.4 times more support than its complement. In other words, there is some support that the relation between relationship quality at Time 1 and student engagement and loyalty at Time 2 is stronger than the reverse ordering.

CLPM with manifest variables

Subsequently, we tested a model in which we examined all five dimensions of relationship quality and the three dimensions of engagement and student loyalty separately. All variables were included as manifest variables. Because our previous analyses indicated that we could not assume measurement (i.e., factorial) invariance for affective conflict over time, we estimated a model with affective conflict (i.e., Model 2a) and without affective conflict (i.e., Model 2b). Results for Model 2a revealed that, as hypothesized, the results showed that order‐restricted hypothesis 1 had 4.1 times more support than its complement. This result indicates that cross‐lagged relations from trust in benevolence and trust in honesty at Time 1 to affective commitment, affective conflict, and satisfaction at Time 2 are more likely than the reverse ordering. Furthermore, cross‐lagged relations from relationship quality at Time 1 to student engagement and student loyalty at Time 2 also supported our hypotheses. The results showed that order‐restricted hypothesis 2 had 148.3 times more support than its complement. Evaluation of the model without affective conflict (Model 2b) still confirmed the hypotheses, albeit the results were less strong, that is, order‐restricted hypothesis 1 had 2.6 times more support than its complement; order‐restricted hypothesis 2 had 14.0 times more support than its complement.

Discussion

Within this study, based on the theoretical underpinnings, we were interested in the strength and directionality of the relations between the relationship quality factors of trust and affect and of the associations between relationship quality, student engagement, and loyalty. This study used a relational approach by applying a newly developed relationship quality scale for higher education (Snijders et al., 2018, 2019, 2020). The focus was on students’ perceptions of the quality of their relationships with all contact persons from their educational institution (e.g., teachers, professors, mentors, exam committee, librarians, and other faculty/staff members). Students’ perceptions were examined to illuminate the associations between relationship quality dimensions in higher education over time, and also with likely outcomes (i.e., engagement with studies and loyalty intentions).

Relationship quality over time

The relationship quality factors of trust and affect were tested at both a higher level (i.e., latent factors for trust and affect) and a more fine‐grained level (i.e., all relationship quality constructs taken separately). Both types of analyses confirmed that trust seems to be a precursor for affect; trust in benevolence and honesty at Time 1 have a stronger relation with affective commitment, satisfaction, and affective conflict at Time 2 than the reverse ordering. Our study’s findings indicate that educational practitioners should focus on the way students perceive trust in faculty/staff. The current research adds value to the body of knowledge on interpersonal relationships in education.

A psychological approach to trust development (Lewicki et al., 2006) mentioned the existence of a trust‐distrust continuum. Our study’s findings indicate that educational practitioners should focus on the way students perceive trust in faculty/staff and their higher education institution and that they should take into account the relational phase students are in (i.e., relationship intensity, see Castaldo, 2007).

When evaluating a second model leaving out affective conflict, the findings indicated that the path from trust to affect (i.e., satisfaction and affective commitment) is stronger than the reverse. Within this study, students responded differently over time to how they interpreted affective conflict, as evidenced by the test of factorial invariance, perhaps due to the multiple encounters within a student’s experience. First‐year students may initially understand the meaning of conflict differently from the conflict they later experience during that year (e.g., arising from unclear feedback on assignments or slow responsiveness to questions versus from negative binding study advice). Similarly, seniors might also interpret the meaning of conflict differently at the beginning of the year than near the end of the year (e.g., arising from adequate guidance versus from feedback on graduation research).

For students, the consequences of affective conflict seem to be bigger near the end of the year (e.g., difficulties surrounding internships, graduation research, negative binding study advice). Hence, our findings indicate that the meaning of affective conflict may change over time.

Relationship quality, student engagement, and loyalty

The second hypothesis focused on the strength of the ordering of relations between relationship quality, student engagement, and student loyalty. Our results confirmed H2, which proposed that relationship quality at Time 1 had a stronger association with student engagement and student loyalty at Time 2 than the reverse ordering. This study’s findings contribute to the theoretical implications of student relationships in higher education (e.g., Hagenaur & Volet, 2014), which cover a broad array of positive student outcomes such as motivational outcomes (Gehlbach, Brinkworth, & Harris, 2012). This study’s findings add to that body of knowledge, indicating that relationship quality is essential for student engagement and loyalty. Hence, building positive relationships with students through relationship quality might positively influence students’ involvement. Following Castaldo’s (2007) ideas of phases of relationship building, this study implies that relationship quality might eventually lead to loyalty during the relationship between students and faculty/staff. These findings are in line with previous studies (e.g., Hennig‐Thurau et al., 2001). Student loyalty is essential for higher education institutions in several ways, for instance, positive word‐of‐mouth such as students' recommendations to others (Farrow & Yuan, 2011).

Limitations and future directions

Although this study adds value to the existing literature in higher education, several limitations need to be mentioned. First, the data were based on self‐reported student responses. Although surveys are an acceptable way to collect data on students’ perceptions and attitudes, including responses from other actors, teachers, or mentors might help get a more objective view (e.g., Demetriou, Ozer, & Essau, 2015). Therefore, it would be interesting to replicate the study and also include teachers’ perceptions and compare them with students’ perceptions (see, for example, Koomen & Jellesma, 2015, who investigated both students’ and teachers’ perspectives in an elementary school setting).

Second, the sample used was based on students from three Dutch higher education institutions. Students were relatively evenly distributed concerning age, gender, and different educational programs of study. However, we recommend investigating the perceptions of students from several institutions from other countries, so that the intercultural interpretations of the constructs under study can be further examined (e.g., the relevance of intercultural competency through social exchange theory in a higher education setting; Pillay & James, 2015). Further investigation of student responses by study year and by gender might also reveal specific information on the relationship quality students perceive.

Next, the relationship quality construct was measured with the same items per relationship quality dimension per measurement point; however, weak measurement invariance could not be assumed for affective conflict. This means that students evaluated the affective conflict items differently over time. A possible explanation might be that in the second semester, students have had more positive or negative experiences and can better interpret what conflict means for them (i.e., irritations, frustration, and anger). Possibly, the more negative emotions (i.e., high levels of anxiety) students perceive in the relationships they have with their educational faculty and staff, the lower students’ trust is in faculty and staffs’ integrity, reliability, and helpfulness (see also control–value theory; Artino & Pekrun, 2014).

Future work may focus on how conflict develops over time; for example, what defining moments students indicate as conflicts and why they are critical incidents in students’ academic lives (Snijders et al., 2020). Conflict within a student‐teacher relationship might be due to the perception of reciprocal discontentment, disapproval, and unpredictability (Marengo et al., 2018).

Finally, collecting data from multiple time points over a closer interval could be used to apply a random‐intercept cross‐lagged panel analysis (Hamaker et al., 2015; e.g., Košir & Tement, 2014). Please also note that the relationships that were found only apply to the time intervals used in this study. When using a shorter time interval, the associations between variables would probably have been stronger, which is interesting to examine in future research. Furthermore, when investigating the development of loyalty, it would also be important to look over time periods such as from year to year and from students to alumni.

Conclusion

This study was a first attempt to explore the temporal ordering of the relationship quality dimensions of trust (i.e., trust in honesty and trust in benevolence) and affect (i.e., affective commitment, satisfaction, and affective conflict). We also investigated the temporal ordering between relationship quality, student engagement, and student loyalty. To that end, we used data from two time points.

This research adds to the existing body of knowledge that students’ trust in the quality of their relationships with faculty/staff in higher education is essential for the development of commitment and satisfaction. Second, relationship quality factors positively influence students’ engagement with their studies and their loyalty. Therefore, we recommend that higher education institutions apply a relational approach that considers students’ relationship quality evaluations in more depth. We examined the hypotheses by evaluating simultaneous comparisons between estimates. The findings supported our hypotheses; however, further research is needed to empirically capture the role of relationship quality in higher education more firmly. Moreover, we recommend investigating further the consequences of relationship quality for students’ involvement and reciprocal effects using short‐term longitudinal data.

Author contributions

Remy Rikers (Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing – review & editing) Sofie Loyens (Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing – review & editing) Rebecca M. Kuiper (Formal analysis; Methodology; Software; Validation; Writing – review & editing) Ingrid Snijders, (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing) Lisette Wijnia (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing).

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. Gender and study year.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research.

For critical comments and suggestions, we would like to thank Dr. Emily Fox and anonymous reviewers.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material for this article.

References

- Akaike, H. (1978). On the likelihood of a time series model. The Statistician, 27, 217–235. 10.2307/2988185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altinisik, Y. , Nederhof, E. , Van Lissa, C. J. , Hoijtink, H. , Oldehinkel, A. , & Kuiper, R. M. (2018). Evaluation of inequality constrained hypotheses using a generalisation of the AIC [Unpublished manuscript]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artino, A. R. , & Pekrun, R. (2014). Using control‐value theory to understand achievement emotions in medical education. Academic Medicine, 89, 1696. 10.1097/acm.0000000000000536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonet, G. , & Walters, B. R. (2016). High impact practices: Student engagement and retention. College Student Journal, 50, 224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, J. L. H. (2009). The process of customer engagement: A conceptual framework. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 17(1), 63–74. 10.2753/mtp1069-6679170105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, J. L. H. (2011). Engaging the student as a customer: A relationship marketing approach. Marketing Education Review, 21, 211–228. 10.2753/mer1052-8008210302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk, A. , & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, K. P. , & Anderson, D. R. (2002). Model selection and multi‐model inference: A practical information‐theoretic approach. New York: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, R. A. , Crisp, D. A. , & Burns, R. B. (2020). Re‐examining the reciprocal effects model of self‐concept, self‐efficacy, and academic achievement in a comparison of the cross‐lagged panel and random‐intercept cross‐lagged panel frameworks. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 77–91. 10.1111/bjep.12265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaldo, S. (2007). Trust in market relationships (1st. ed.). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M. , & Auger, G. A. (2013). Exploring determinants of relationship quality between students and their academic department. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 68, 255–268. 10.1177/1077695813495048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell, J. P. , & Wellborn, J. G. (1991). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self‐system processes. In Gunnar R. & Sroufe L. (Eds.), Self processes and development: Minnesota symposium on child psychology (pp. 43–77). Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, L. A. , Evans, K. R. , & Cowles, D. (1990). Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. Journal of Marketing, 54, 68–81. 10.2307/1251817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culver, J. (2015). Relationship quality and student engagement [doctoral dissertation]. Wayne State University. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L. , & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self‐determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49, 182–185. 10.1037/a0012801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou, C. , Ozer, B. U. , & Essau, C. A. (2015). Self‐report questionnaires. The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology, 1–6. 10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engels, M. C. , Colpin, H. , Van Leeuwen, K. , Bijttebier, P. , Van Den Noortgate, W. , Claes, S. , … Verschueren, K. (2016). Behavioral engagement, peer status, and teacher‐student relationships in adolescence: A longitudinal study on reciprocal influences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1192–1207. 10.1007/s10964-016-0414-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, H. , & Yuan, Y. C. (2011). Building stronger ties with alumni through Facebook to increase volunteerism and charitable giving. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 16, 445–464. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01550.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farr‐Wharton, B. , Charles, M. B. , Keast, R. , Woolcott, G. , & Chamberlain, D. (2018). Why lecturers still matter: The impact of lecturer‐student exchange on student engagement and intention to leave university prematurely. Higher Education, 75(1), 167–185. 10.1007/s10734-017-0190-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks, J. A. , Blumenfeld, P. C. , & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. 10.3102/00346543074001059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Moya, I. , Brooks, F. , & Moreno, C. (2020). Humanising and conducive to learning: An adolescent students' perspective on the central attributes of positive relationships with teachers. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 35(1), 1–20. 10.1007/s10212-019-00413-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Moya, I. , Bunn, F. , Jiménez‐Iglesias, A. , Paniagua, C. , & Brooks, F. M. (2019). The conceptualisation of school and teacher connectedness in adolescent research: A scoping review of literature. Educational Review, 71, 423–444. 10.1080/00131911.2018.1424117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlbach, H. , Brinkworth, M. E. , & Harris, A. D. (2012). Changes in teacher‐student relationships. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 690–704. 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, T. , & Kharouf, H. (2020). The value of co‐operation: an examination of the work relationships of university professional services staff and consequences for service quality. Studies in Higher Education, 1–15. 10.1080/03075079.2020.1725878 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenauer, G. , & Volet, S. E. (2014). Teacher‐student relationship at university: An important yet under‐researched field. Oxford Review of Education, 40, 370–388. 10.1080/03054985.2014.921613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaker, E. L. , Kuiper, R. M. , & Grasman, R. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross‐lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. 10.1037/a0038889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgesen, Ø. , & Nesset, E. (2007). What accounts for students' loyalty? Some field study evidence. International Journal of Educational Management, 21, 126–143. 10.1108/09513540710729926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig‐Thurau, T. , Langer, M. F. , & Hansen, U. (2001). Modeling and managing student loyalty. Journal of Service Research, 3, 331–344. 10.1177/109467050134006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z. , Shiu, E. , Henneberg, S. , & Naude, P. (2016). Relationship quality in business to business relationships—Reviewing the current literature and proposing a new measurement model. Psychology & Marketing, 33, 297–313. 10.1002/mar.20876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38, 758–773. 10.1080/03075079.2011.598505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. K. , & Lundberg, C. A. (2016). A structural model of the relationship between student‐faculty interaction and cognitive skills development among college students. Research in Higher Education, 57, 288–309. 10.1007/s11162-015-9387-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klem, A. M. , & Connell, J. P. (2004). Relationships matter: Linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. Journal of School Health, 74, 262–273. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koomen, H. M. Y. , & Jellesma, F. C. (2015). Can closeness, conflict, and dependency be used to characterise students' perceptions of the affective relationship with their teacher? Testing a new child measure in middle childhood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 479–497. 10.1111/bjep.12094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Košir, K. , & Tement, S. (2014). Teacher‐student relationship and academic achievement: A cross‐lagged longitudinal study on three different age groups. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29, 409–428. 10.1007/s10212-013-0205-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh, G. D. (2001). Assessing what really matters to student learning inside the national survey of student engagement. Change: the Magazine of Higher Learning, 33, 10–17. 10.1080/00091380109601795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper, R. M. (2020). AIC‐type theory‐based model selection for structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal (Teachers' Corner), 10.1080/10705511.2020.1836967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper, R. M. , Hoijtink, H. , & Silvapulle, M. J. (2011). An Akaike‐type information criterion for model selection under inequality constraints. Biometrika, 98, 495–501. 10.1093/biomet/asr002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. (2012). The effects of the teacher‐student relationship and academic press on student engagement and academic performance. International Journal of Educational Research, 53, 330–340. 10.1016/j.ijer.2012.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leenknecht, M. J. M. , Snijders, I. , Wijnia, L. , Rikers, M. J. M. P. , & Loyens, S. M. M. (2020). Building relationships in higher education to support students’ motivation. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–22. 10.1080/13562517.2020.1839748 33173242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, R. J. , Tomlinson, E. C. , & Gillespie, N. (2006). Models of interpersonal trust development: Theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. Journal of Management, 32, 991–1022. 10.1177/0149206306294405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manzuoli, C. , Pineda‐Báez, C. , & Vargas Sánchez, A. D. (2019). School engagement for avoiding drop out in middle school education. International Education Studies, 12, 35–48. 10.5539/ies.v12n5p35 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marengo, D. , Jungert, T. , Lotti, N. O. , Settanni, M. , Thornberg, R. , & Longobardi, C. (2018). Conflictual student–teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/ victims. Educational Psychology, 38, 1201–1217. 10.1080/01443410.2018.1481199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. L. , Williams, L. M. , & Silberstein, S. M. (2019). Found my place: The importance of faculty relationships for seniors' sense of belonging. Higher Education Research & Development, 38, 594–608. 10.1080/07294360.2018.1551333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, J. , & Spekman, R. (1994). Characteristics of partnership success: Partnership attributes, communication behaviour, and conflict resolution techniques. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 135–152. 10.1002/smj.4250150205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R. M. , & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment‐trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58, 20–38. 10.2307/1252308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morinaj, J. , & Hascher, T. (2019). School alienation and student well‐being: A cross‐lagged longitudinal analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34, 273–294. 10.1007/s10212-018-0381-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B. , & Asparouhov, T. (2013). New methods for the study of measurement invariance with many groups. Mplus Technical Report. http://www.statmodel.com [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, L. J. , & Putwain, D. W. (2020). A cross‐lagged panel analysis of fear appeal appraisal and student engagement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 830–847. 10.1111/bjep.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keeffe, P. (2013). A sense of belonging: Improving student retention. College Student Journal, 47, 605–613. https://www.ingentaconnect.org/content/prin/csj/2013/00000047/00000004/art00005 [Google Scholar]

- Palmatier, R. W. (2008). Interfirm relational drivers of customer value. Journal of Marketing, 72, 76–89. 10.1509/jmkg.72.4.76 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, J. , & Taylor, L. (2011). Improving student engagement. Current Issues in Education, 14(1), 1–32. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/53580 [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella, E. T. , & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students. Indianapolis: Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R. C. , Hamre, B. K. , & Allen, J. P. (2012). Teacher‐student relationships and engagement: Conceptualizing, measuring, and improving the capacity of classroom interactions. In Christenson S. L., Reschly A. & Wylie C. (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 365–386). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7-17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay, S. , & James, R. (2015). Examining intercultural competency through social exchange theory. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 27, 320–329. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1093704.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pöysä, S. , Vasalampi, K. , Muotka, J. , Lerkkanen, M. K. , Poikkeus, A. M. , & Nurmi, J. E. (2019). Teacher‐student interaction and lower secondary school students' situational engagement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 374–392. 10.1111/bjep.12244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnick, D. L. , & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. 10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm‐Kaufman, S. , & Sandilos, L. (2010). Improving students' relationships with teachers. http://www.apa.org/education/k12/relationships [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K. , Varki, S. , & Brodie, R. (2003). Measuring the quality of relationships in consumer services: An empirical study. European Journal of Marketing, 37, 169–196. 10.1108/03090560310454037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas‐Méndez, J. I. , Vasquez‐Parraga, A. Z. , Kara, A. , & Cerda‐Urrutia, A. (2009). Determinants of student loyalty in higher education: A tested relationship approach in Latin America. Latin American Business Review, 10(1), 21–39. 10.1080/10978520903022089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roorda, D. L. , Jak, S. , Zee, M. , Oort, F. J. , & Koomen, H. M. (2017). Affective teacher‐student relationships and students' engagement and achievement: A meta‐analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psychology Review, 46, 239–261. 10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roorda, D. L. , Koomen, H. M. Y. , Spilt, J. L. , & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher‐student relationships on students' school engagement and achievement. Review of Educational Research, 81, 493–529. 10.3102/0034654311421793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roorda, D. L. , Verschueren, K. , Vancraeyveldt, C. , Van Craeyevelt, S. , & Colpin, H. (2014). Teacher–child relationships and behavioral adjustment: Transactional links for preschool boys at risk. Journal of School Psychology, 52, 495–510. 10.1016/j.jsp.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez‐Álvarez, N. , Extremera, N. , & Fernández‐Berrocal, P. (2019). The influence of trait meta‐mood on subjective well‐being in high school students: A random intercept cross‐lagged panel analysis. Educational Psychology, 39, 332–352. 10.1080/01443410.2018.1543854 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , & Bakker, A. B. (2003). UWES Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Preliminary manual. https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/Test%20Manuals/Test_manual_UWES_English.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , Bakker, A. B. , & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 701–716. 10.1177/0013164405282471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , Martínez, I. M. , Pinto, A. , Salanova, M. , & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 33, 464–481. 10.1177/0022022102033005003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger, W. , Cervera, A. , & Pérez‐Cabañero, C. (2017). Sticking with your university: The importance of satisfaction, trust, image, and shared values. Studies in Higher Education, 42, 2178–2194. 10.1080/03075079.2015.1136613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, I. , Rikers, R. M. J. P. , Wijnia, L. , & Loyens, S. M. M. (2018). Relationship quality time: the validation of a relationship quality scale in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development, 37(2), 404–417. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07294360.2017.1355892?journalCode=cher20 [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, I. , Wijnia, L. , Rikers, R. M. J. P. , & Loyens, S. M. M. (2019). Alumni loyalty drivers in higher education. Social Psychology of Education, 22(3), 607–627. 10.1007/s11218-019-09488-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, I. , Wijnia, L. , Rikers, R. M. J. P. , & Loyens, S. M. M. (2020). Building bridges in higher education: Student‐faculty relationship quality, student engagement, and student loyalty. International Journal of Educational Research, 100, 101538. 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101538 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steegen, S. , Tuerlinckx, F. , Gelman, A. , & Vanpaemel, W. (2016). Increasing transparency through a multiverse analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 702–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, M. , & Yang, S. (2008). Student–university relationships and reputation: A study of the links between key factors fostering students' supportive behavioural intentions towards their university. Higher Education, 57, 787–811. 10.1007/s10734-008-9176-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tschannen‐Moran, M. (2014). Trust matters: Leadership for successful schools. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Umbach, P. D. , & Wawrzynski, M. R. (2005). Faculty do matter: The role of college faculty in student learning and engagement. Research in Higher Education, 46, 153–184. 10.1007/s11162-004-1598-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Maele, D. , Forsyth, P. B. , & Van Houtte, M. (2014). Trust and school life. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Vanbrabant, L. , & Kuiper, R. M. (2020). Restriktor: Goric function. R package version 0.2‐15. http://restriktor.org [Google Scholar]

- Vanbrabant, L. , & Rosseel, Y. (2020). Restriktor: Restricted statistical estimation and inference for linear models. R package version 0.2‐15. http://restriktor.org [Google Scholar]

- Vanbrabant, L. , Van Loey, N. , & Kuiper, R. M. (2020). Evaluating a theory‐based hypothesis against its complement using an AIC‐type information criterion with an application to facial burn injury. Psychological Methods, 25, 129–142. 10.1037/met0000238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Schee, B. A. (2008a). Review of "Minority student retention: The best of the Journal of College Student Retention: Research, theory & practice" [Review of the book Minority student retention: The best of the Journal of College Student Retention: Research, theory & practice, by A. Seidman (Ed.)]. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 45(2). 10.2202/1949-6605.1954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Schee, B. A. (2008b). The utilisation of retention strategies at church‐related colleges: A longitudinal study. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 10, 207–222. 10.2190/cs.10.2.f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmakers, E. , & Farrell, S. (2004). AIC model selection using Akaike weights. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 11(1), 192–196. 10.3758/bf03206482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xerri, M. J. , Radford, K. , & Shacklock, K. (2018). Student engagement in academic activities: A social support perspective. Higher Education, 75, 589–605. 10.1007/s10734-017-0162-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zee, M. , Koomen, H. M. , & Van der Veen, I. (2013). Student‐teacher relationship quality and academic adjustment in upper elementary school: The role of student personality. Journal of School Psychology, 51, 517–533. 10.1016/j.jsp.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V. A. , Bitner, M. J. , Gremler, D. D. , & Lovelock, C. (2009). Services marketing. New York: McGraw‐Hill/Irwin. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Gender and study year.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material for this article.