Abstract

The aim of the present study was to develop adjunct strains which can grow in the presence of bacteriocin produced by lacticin 3147-producing starters in fermented products such as cheese. A Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei strain (DPC5336) was isolated from a well-flavored, commercial cheddar cheese and exposed to increasing concentrations (up to 4,100 arbitrary units [AU]/ml) of lantibiotic lacticin 3147. This approach generated a stable, more-resistant variant of the isolate (DPC5337), which was 32 times less sensitive to lacticin 3147 than DPC5336. The performance of DPC5336 was compared to that of DPC5337 as adjunct cultures in two separate trials using either Lactococcus lactis DPC3147 (a natural producer) or L. lactis DPC4275 (a lacticin 3147-producing transconjugant) as the starter. These lacticin 3147-producing starters were previously shown to control adventitious nonstarter lactic acid bacteria in cheddar cheese. Lacticin 3147 was produced and remained stable during ripening, with levels of either 1,280 or 640 AU/g detected after 6 months of ripening. The more-resistant adjunct culture survived and grew in the presence of the bacteriocin in each trial, reaching levels of 107 CFU/g during ripening, in contrast to the sensitive strain, which was present at levels 100- to 1,000-fold lower. Furthermore, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR was employed to demonstrate that the resistant adjunct strain comprised the dominant microflora in the test cheeses during ripening.

Members of the lactic acid bacteria play an essential role in a wide variety of food fermentations, with Lactococcus lactis representing the primary starter cultures exploited for cheddar cheese manufacture. In addition, a population of adventitious microflora, otherwise known as nonstarter lactic acid bacteria (NSLAB), can proliferate during ripening and often form the dominant flora in the cheese. The precise role of NSLAB strains in flavor development remains unclear; however, whether their effect is positive or negative, they certainly contribute to the unpredictability associated with cheddar cheese quality (7). Importantly, NSLAB have also been associated with defects in cheese such as the formation of calcium lactate crystals (27) and slit formation.

Given increasing consumer demand, the challenge now facing the cheesemaker is the development of a safe, well-flavored, consistent cheddar. One approach to improving cheese flavor has been the deliberate addition of selected adjunct lactobacilli during manufacture which would impart beneficial qualities (7). Although some studies reported cheese with improved flavor, in other studies adjunct cultures were responsible for flavor defects (13, 14, 20, 23). In addition, comparisons with control vats were difficult to interpret due to contamination with the adjunct strain or with adventitious NSLAB, which eventually reach levels similar to those in the test vat (1, 28). Hence, in order to study the relevance of NSLAB, as well as examine the role of adjunct cultures in cheddar flavor, there is a requirement for an effective and simple method of controlling adventitious strains during manufacture and ripening.

In previous studies, we reported on a lacticin 3147-producing lactococcal starter which is capable of inhibiting the growth of NSLAB during cheese ripening (6, 25). Lacticin 3147 is a lantibiotic-type, two-component (17) bacteriocin which is inhibitory to a broad spectrum of gram-positive bacteria (24–26). The genetic determinants encoding lacticin 3147 are located on a 60.3-kb conjugative plasmid (5) which has been transferred from the parent L. lactis DPC3147 to a range of cheesemaking lactococcal starters. One such strain previously used to manufacture full-fat cheddar, L. lactis DPC4275, exhibited control over the developing NSLAB population (25). In a further study, this strain was successfully used to manufacture a low-fat cheddar, which was subsequently ripened at the elevated temperature of 12°C in order to accelerate the ripening process while suppressing wild NSLAB populations (6). Importantly, the DPC4275 strain may also be used to improve the safety of some cheese products (16). Although this transconjugant strain has been used successfully in these trials, the parent strain, L. lactis DPC3147, is a more efficient producer of lacticin 3147 and is therefore more effective in reducing NSLAB populations.

It has been observed that some bacteria are capable of developing phenotypes of resistance to bacteriocins. For example, nisin-resistant mutants can be generated from sensitive strains by exposure to sublethal concentrations of the bacteriocin (10). The aim of the present study was to generate an adjunct culture which was more resistant to higher concentrations of lacticin 3147 and to analyze its performance when used in combination with a lacticin 3147 starter. It was envisaged that the resistant strain might survive the levels of bacteriocin produced in the cheese during manufacture, while the growth of adventitious NSLAB would be inhibited, thus allowing for analysis of the performance of the resistant strain throughout ripening.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and cultivation conditions.

L. lactis DPC3147 (a natural producer of lacticin 3147), L. lactis DPC4275 (a lacticin 3147-producing transconjugant of a commercial strain) (25), and L. lactis HP (a sensitive indicator strain) were routinely propagated at 30°C in M17 (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.5% lactose or in 10% reconstituted skim milk (RSM). Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei strains were maintained by weekly subculture in MRS (Difco Laboratories) and grown at 37°C. All strains were stocked at −80°C in 40% glycerol and are held in the Dairy Products Research Centre (DPC) collection at Moorepark, Fermoy, Ireland.

Isolation of Lactobacillus strains and development of increased resistance.

Lactobacillus strains were isolated from a well-flavored, commercial, mature cheddar cheese. The cheese was initially macerated in 10-fold-sterile, distilled water, plated on lactobacillus selective agar, which is selective for lactobacilli (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems), and incubated for 5 days at 37°C. Four isolated colonies were selected and propagated in MRS broth. These strains were genetically fingerprinted (see below), following which two of the isolates were further selected and identified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis protein profiling, as outlined by Pot et al. (22).

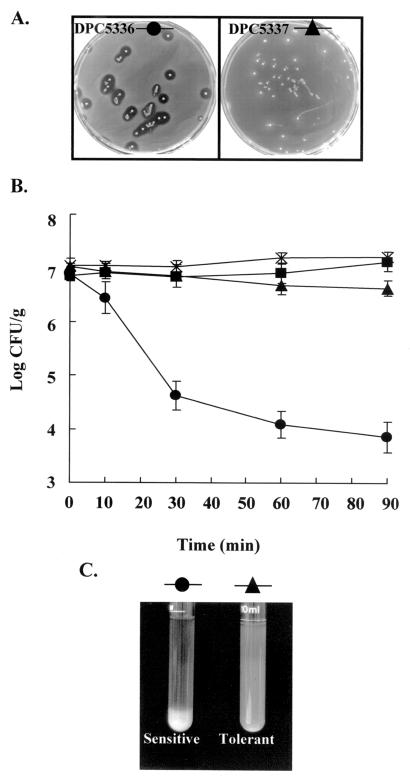

Following typing of these strains, lacticin 3147-resistant variants were selected by stepwise subculture in 1 ml of MRS broth that contained increasing concentrations of bacteriocin as follows: 164, 328, 492, 820, 984, 1,148, 1,640, and 4,100 arbitrary units (AU)/ml. Each subculture was incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The resulting strain, L. paracasei DPC5337, was shown to be resistant to the levels of lacticin 3147 produced by L. lactis DPC3147 by overlaying individual colonies of DPC3147 with a lawn of sensitive (DPC5336) and resistant (DPC5337) cells (Fig. 1A). In addition, ≈1.7 × 108 CFU of the resistant strain were spread plated in MRS agar containing lacticin 3147 (final concentration, 40,960 AU/ml) to assess the rate of development of spontaneous resistance to high levels of lacticin 3147.

FIG. 1.

(A) The agar plates contain isolated colonies of the lacticin 3147-producing strain, L. lactis DPC3147, which are overlaid with a lawns of L. paracasei DPC5336 and DPC5337. The absence of zones of inhibition in the DPC5337 lawn indicates that this strain is more resistant to the levels of lacticin 3147 produced by L. lactis DPC3147 colonies, while strain DPC5336 remains sensitive. (B) Bactericidal activity of lacticin 3147 on L. paracasei DPC5336 (●) and DPC5337 (▴). Bacteriocin was added at a final concentration of 1,000 AU/ml to washed log-phase cells. Controls to which no bacteriocin was added are represented by DPC5336 (▪) and DPC5337 (×). (C) Difference in flocculation during growth between L. paracasei DPC5336 (●) and DPC5337 (▴).

Genetic typing of Lactobacillus strains.

Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)-PCR was subsequently used to verify that these more-resistant strains gave the same genetic fingerprint as the initial L. paracasei DPC5336 strain. The Lactobacillus strains were grown in MRS overnight at 37°C, and 1 ml of each culture was microcentrifuged for 1 min. The genomic DNA from each resultant pellet was isolated by resuspending the pellets in 200 μl of the surfactant, Tergitol (Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd., Poole, Dorset, England) at a final concentration of 10% in sterile distilled water. Amplification of DNA was performed with a Perkin-Elmer DNA Thermal Cycler using R1 primer (5′ ATGTAACGCC 3′) (11) and P5 primer (5′ ACGCGCCCT 3′) (12). Taq DNA polymerase was added during the first temperature cycle (hot start), and DNA was amplified for 35 cycles. Each cycle involved 1 min of denaturation at 93°C followed by an annealing step at 44°C for 1 min and an extension step of 72°C for 1 min. Of the final mixture, 10 μl was analyzed on 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) gels with ethidium bromide staining.

Estimating the relative sensitivities of the resistant variants.

To determine the potency of concentrated lacticin 3147 against L. paracasei DPC5336 and compare it with the potency against the resistant L. paracasei DPC5337 variant strain, the agar well diffusion assay as outlined by Ryan et al. (26) was adopted. The sensitivities of the Lactobacillus strains were expressed relative to the sensitivity of the indicator strain, L. lactis HP. To determine if the increased resistance is a stable feature of these variants, the strains were subcultured daily for 1 week at 37°C in the absence of lacticin 3147 for selection and sensitivity was again determined by the agar well diffusion assay (26).

Effect of concentrated lacticin 3147 on sensitive and resistant strains in buffer.

Both L. paracasei DPC5336 and DPC5337 were grown for 4 h at 37°C (optical density at 600 nm, 0.32), and 2 ml of each was collected in triplicate by centrifugation. These cells were washed in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) and resuspended at approximately 107 CFU/ml in 2 ml of buffer. Lacticin 3147 solution was then added to both strains at a final concentration of 1,000 AU/ml, and the strains were incubated at 37°C. Samples were taken at appropriate intervals over a 90-min period to determine the viable cell count in MRS agar. Control experiments were performed in an identical manner with the exception that no bacteriocin was added. This experiment was performed in triplicate, and error bars in Fig. 1B represent the standard deviations of the counts.

To determine if the survivors from the sensitive and more-resistant cell populations had developed increased resistance following exposure to lacticin 3147 during the experiment, five colonies from each of the MRS plates incubated for 90 min were randomly chosen and the sensitivities of these isolates were determined by the agar well diffusion assay (26).

Analysis of fatty acids in the membranes of Lactobacillus strains.

The procedure for the determination of the fatty acid composition of the membranes was based on the method previously described by van Schaik et al. (29). Both L. paracasei DPC5336 and DPC5337 strains were inoculated at 2% in 1-liter volumes of MRS broth and incubated for 16 h at 37°C. Fatty acids were derivatized to fatty acid methyl esters (FAME), which were subsequently quantified by capillary gas-liquid chromatography using a Varian (Harbor City, Calif.) 3500 gas-liquid chromatograph fitted with a flame ionization detector. Standard FAME C4:0 to C20:2 (all of >99% purity) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). The response factors were calculated relative to the area of C18:0, which was assigned a response factor of 1.00, and quantities were expressed as grams per 100 g of FAME.

Cheesemaking.

For cheesemaking, bulk starters were cultivated in 10% RSM which had been heat treated at 90°C for 30 min and cooled to 21°C before inoculation. All starters were grown separately in 10% RSM and added to the cheese milk at a final rate of 1.4% (vol/vol). Adjunct Lactobacillus strains DPC5336 and DPC5337 were grown overnight at 37°C in MRS broth to approximately 108 CFU/ml and were added at approximately 103 CFU/ml to vats 2 and 3, respectively. Milk was pasteurized (72°C, 15 s) and cooled to 30°C prior to inoculation. Cheese was made as described by Ryan et al. (25) and ripened for 6 months at 7°C.

Analysis of cheese.

The pH-versus-time profiles were monitored during cheesemaking. Samples were also removed during manufacture, and bacteriocin activity was assessed by the method outlined by Ryan et al. (25) with L. lactis HP again being used as the indicator strain.

Microbiological analyses were carried out in duplicate at each sampling time according to the methods outlined by Ryan et al. (25). To estimate bacteriocin activity during ripening, cheese was initially macerated in equal volumes of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) for 10 min and heated to 80°C for 10 min and lacticin 3147 activity was determined by a serial well diffusion assay (25).

After 2- and 4-month intervals, five individual Lactobacillus colonies from each cheese were randomly selected from the LBS agar plates, propagated in MRS broth, and analyzed by RAPD-PCR using the technique described above.

Compositional analysis and cheese grading.

The composition (pH, fat, protein, salt, and moisture) was analyzed by the method of Guinee et al. (9). The cheeses were assessed by a commercial grader from a local cheddar cheese factory. The maximum scores for flavor and aroma and body and texture were 45 and 40, respectively. For cheeses to be described as commercial grade, the minimum scores required are 38 for flavor and aroma and 32 for body and texture.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The variable nature of NSLAB populations probably reflects many of the inconsistencies often associated with cheddar flavor and quality, although this has not been proven experimentally (7). The use of lacticin 3147-producing starters in previous cheesemaking studies resulted in significant reductions in NSLAB counts during ripening (6, 25). In this study, we utilized these starters in combination with a lacticin 3147-resistant adjunct strain, which was found to form the dominant flora in the cheese, thereby showing that this strategy is a method of achieving complete control and manipulation of the developing flora in cheddar cheese.

Isolation of Lactobacillus strains.

Four colonies, morphologically identical and randomly selected, were isolated from a commercial cheddar cheese and analyzed using both RAPD-PCR and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis protein profiling (22). While all were typed as L. paracasei subsp. paracasei by protein profiling, RAPD-PCR did indicate that one of the four was a different strain (results not shown). One of the three dominant isolates was chosen for further study and was designated L. paracasei subsp. paracasei DPC5336.

Once the Lactobacillus strain was isolated and typed, it was necessary to determine if it could develop increased resistance to lacticin 3147. By repeated subculture of this strain in increasing concentrations of lacticin 3147, from 164 AU/ml to 4,100 AU/ml, at 37°C for 48 h in MRS broth, a lacticin 3147-resistant variant of DPC5336 was gradually generated. This resistant strain was designated L. paracasei subsp. paracasei DPC5337. Comparisons of the sensitivities of DPC5336 and DPC5337 to concentrated lacticin 3147 indicated that DPC5337 was 32 times less sensitive than the parent Lactobacillus strain, DPC5336. Importantly, the resistance thus acquired was subsequently found to be a stable feature of the strain, as indicated by sensitivity assays carried out on daily subcultures over a 1-week period. Both DPC5336 and DPC5337 were routinely subjected to RAPD-PCR in order to verify that the resistant strain is a variant of the parent sensitive strain. Given that the objective of this study was to add the resistant strain as an adjunct to a lacticin 3147-producing starter, it was important to ensure that it could survive the levels made by a producer. To this end, overnight, isolated colonies of L. lactis DPC3147 were overlaid individually with a lawn of resistant and sensitive lactobacilli. As expected, sufficient bacteriocin to cause zones of inhibition against DPC5336 was produced, whereas no such inhibition against DPC5337 was observed (Fig. 1A). That this strain is not completely resistant to lacticin 3147 was demonstrated by the observation that no colonies were obtained following the plating of ≈108 CFU of the resistant DPC5337 on MRS agar containing 40,960 AU/ml. Thus cells resistant to higher concentrations of the bacteriocin do not seem to emerge spontaneously. Indeed, in our hands, we have only observed resistance to levels marginally in excess of the MIC for any given strain. For this reason we have in the past referred to this gradually acquired phenotype as tolerance rather than resistance (24).

Characterization of the more-resistant Lactobacillus strain.

Following the initial generation of DPC5337, a number of biochemical tests on both resistant and parent strains were performed. Previous studies have reported on the development of acquired or spontaneous resistance by Listeria subsp. (3, 10, 18, 19) to nisin, a commercially available broad-spectrum bacteriocin. Studies of Listeria mutants suggest that resistance may be caused by alterations in the fatty acid composition of the cell membrane (18, 19, 30). However, evidence which suggests that cell wall adaptations may also be responsible has also been presented (3, 4, 15). An important distinction between strains DPC5336 and DPC5337 was observed: the resistant derivative did not flocculate as readily during growth (Fig. 1C); this indicates that the resistant phenotype may be associated with changes on the cell surface. Furthermore, preliminary results from adsorption assays suggest that the resistant cells adsorb less bacteriocin than the sensitive cells (results not shown). Gas chromatographic analysis was used to determine whether the increased resistance was associated with changes in the membrane lipids. However, no significant differences between the membranes of DPC5336 and DPC5337 were observed, implying that the membrane lipids remain unaffected by the development of resistance to lacticin 3147 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Membrane fatty acid composition of L. paracasei DPC5336 and L. paracasei DPC5337

| Fatty acid | % of total fatty acids for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| DPC5336 | DPC5337 | |

| C12:0 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| C14:0 | 12.3 | 11.02 |

| C15:0 | 0.94 | 0.99 |

| C16:0 | 18.08 | 18.23 |

| C16:1 | 12.48 | 12.18 |

| C17:0 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| C18:0 | 0.56 | 0.62 |

| C18:1 | 45.19 | 46.14 |

| C18:2 | 0.54 | 0.58 |

| Others | 9.43 | 9.76 |

Inhibition of resistant strain by concentrated lacticin 3147.

Lacticin 3147 was shown to cause rapid cell death when added to log-phase cells of both DPC5336 and DPC5337, in contrast to results for control cultures to which no bacteriocin was added (Fig. 1B). However, the rate of killing and degree of inhibition were far greater for the sensitive strain than for the more-resistant strain. The addition of bacteriocin to approximately 107 actively growing cells resulted in >99.9% killing of sensitive cells, whereas only approximately 40% of the more-resistant cells were killed under identical conditions.

The surviving cells from the sensitive population which had been exposed to bacteriocin did not develop resistance during the course of the experiment, as representative isolates were shown to exhibit the same level of sensitivity to lacticin 3147 as isolates from the sensitive control. Furthermore, survivors from the resistant population did not display an increased level of resistance over that for the DPC5337 control.

Cheesemaking using resistant lactobacilli as adjuncts.

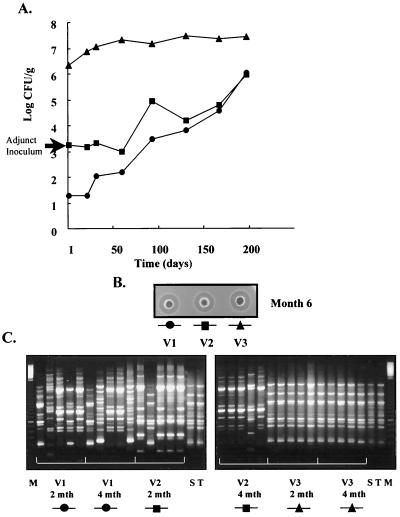

A pilot cheddar cheese trial was initially carried out using L. lactis DPC3147 as the starter strain, even though previous trials using this strain suggest that it is associated with the development of off-flavors in cheese. This strain, however, produces sufficient acid to manufacture cheddar and is also the most efficient producer of lacticin 3147 identified to date. As observed in the previous trial, L. lactis DPC3147 produced sufficient acid to reduce the pH to 5.2 within the desired manufacturing time. Lacticin 3147 activity was assayed during manufacture and reached approximately 1,280 to 2,560 AU/g of cheese. This level of activity was maintained throughout ripening and correlated with a reduction in the growth rate of NSLAB in the control cheeses (Fig. 2). During the first 3 months of ripening, the levels of lactobacilli in vats 1 and 2 remained relatively low at approximately 3 × 103 CFU/g. In contrast, the experimental vat had at least 100-fold more lactobacilli at day 1, and this value increased to 6 × 106 CFU/g after 50 days. This represented a 1,000-fold increase in lactobacillus numbers over those found in control vats. Given that the initial inoculum of each adjunct culture was only 103 CFU/ml, this indicated that the more-resistant strain grew (vat 3) during cheese manufacture whereas growth of the sensitive strain was inhibited (vat 2).

FIG. 2.

(A) Growth of NSLAB during cheese ripening in trial 1. The adjunct cultures were added to vats 2 and 3 at a level 103 CFU/ml (arrow). No adjunct was added to vat 1. The cheese in vat 1 (●) was manufactured with L. lactis DPC3147, the natural producer of lacticin 3147; that in vat 2 (▪) was manufactured with L. lactis DPC3147 and L. paracasei DPC5336, and that in vat 3 (▴) was manufactured with L. lactis DPC3147 and L. paracasei DPC5337. (B) Residual lacticin 3147 activity in the cheese after 6 months of ripening is observed as zones of inhibition against the indicator, L. lactis HP. V1 to V3, vats 1 to 3, respectively.

By the end of the investigation period of 6 months, there was approximately a 100-fold difference between the DPC5336 and DPC5337 adjunct strains in the respective cheeses. The significant difference in counts throughout ripening should ensure that this adventitious flora does not interfere in the interpretation of results and may be sufficient to result in flavor differences in the cheese. As expected, the cheese manufactured with L. lactis DPC3147 as the starter did not pass the standards set by the commercial grader, due to an overriding off-flavor associated with this strain. To date, however, more than 30 lacticin 3147-producing transconjugant starters have been generated for possible application in cheesemaking (2, 21). Although, in general, they are less efficient producers of lacticin 3147, one such strain, L. lactis DPC4275, which has previously been used to manufacture cheddar, was found to significantly reduce NSLAB counts. Hence, it was necessary to determine whether this strain could also be used as a tool to manipulate the developing microflora in cheddar.

To this end, a second trial, similar to trial 1 except that transconjugant L. lactis DPC4275 was used as the starter culture, was set up. This strain was previously reported to perform satisfactorily as a starter (6, 25), and in this study it also reduced the pH within the desired time. Although reduced concentrations of bacteriocin were produced compared to those produced in trial 1, levels of up to 640 AU/g were detected during manufacture and these levels remained stable throughout ripening (Fig. 3B). However, these levels of bacteriocin were not sufficient to completely inhibit the developing NSLAB. As in trial 1, the resistant adjunct culture grew during manufacture and for the first 3 months there were approximately 100-fold more lactobacilli in the cheese made in vat 2 than in that made in vat 1. However, a highly significant difference between the control vats and vat 3 was observed. Levels of 10 6 to 10 7 CFU of resistant Lactobacillus/g were enumerated in this cheese throughout ripening, and, at 50 days, a 3-log-unit difference between vat 3 and the control vats was observed (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

(A) Growth of NSLAB during cheese ripening in trial 2. The adjunct cultures were added to vats 2 and 3 at a level 103 CFU/ml (arrow). No adjunct was added to vat 1. The cheese in vat 1 (●) was manufactured with L. lactis DPC4275, that in vat 2 (▪) was manufactured with L. lactis DPC4275 and L. paracasei DPC5336, and that in vat 3 (▴) was manufactured with L. lactis DPC4275 and L. paracasei DPC5337. (B) Residual lacticin 3147 activity in the cheese after 6 months of ripening is observed as zones of inhibition against the indicator, L. lactis HP. V1 to V3, vats 1 to 3, respectively. (C) RAPD-PCR profiles of a representative number of NSLAB isolates from each of the cheeses at months 2 and 4. Lanes S and T, profiles of DPC5336 and DPC5337, respectively; lane M, 100-bp ladder.

Representative NSLAB were isolated from the cheeses after 2 and 4 months from both trials 1 and 2 and analyzed using RAPD-PCR fingerprinting. Five colonies at each time period from trial 2 were analyzed, and all 10 isolates from vat 3 were identical to the adjunct strain (Fig. 3C). As expected, these isolates also displayed resistance to lacticin 3147. Hence, the isolates from cheese made with the resistant adjunct were phenotypically more resistant to lacticin 3147 and contained fingerprints genotypically identical to those of the added strain. In contrast, only 1 of the 10 isolates from vat 2 cheese gave rise to a genetic fingerprint corresponding to the sensitive, parent Lactobacillus strain, and this information coupled with the overall Lactobacillus numbers in vat 2 indicates that this adjunct strain was inhibited by the lacticin 3147 present in the cheese. Similarly, 20 isolates from the experimental cheese in trial 1 were analyzed, and these also gave rise to fingerprints corresponding to the resistant strain, DPC5337 (results not shown). From these results, it can be deduced that the resistant adjunct strain formed the dominant Lactobacillus population in the experimental cheeses. We deliberately used food grade adjunct Lactobacillus strains so that cheese could be manufactured at pilot scale and subjected to subsequent sensory analysis.

Compositional and sensory analysis.

The gross compositions of all cheeses were within the parameters set out by Giles and Lawrence (8) for cheddar cheese. There was no noteworthy difference in water-soluble nitrogen, phosphotungstic acid-nitrogen, and free amino acid composition between the control cheeses and cheese made with the adjunct cultures.

Even though the purpose of this study was to demonstrate that lacticin 3147-producing starter cultures can be used to manipulate and exert control over the developing microflora in cheddar, the cheeses were presented for commercial grading after 7 months of ripening to determine if there was any detectable concomitant influence on flavor. In the graders opinion, all three cheeses were found to be of commercial grade. The control cheeses were graded with a value of 38 for flavor but were described as somewhat bitter, while the test cheese was awarded a higher value of 39, with the bitter flavor being almost undetectable.

Conclusions.

This study illustrates how lacticin 3147, in combination with resistant strains, can be applied as a tool to control the microbial flora of cheese products. In this way, proliferation of adventitious gram-positive flora can be limited, allowing both the producing starters and resistant adjuncts to flourish. This system offers obvious advantages over techniques such as aseptic production and antibiotic addition for NSLAB control, in that it can be adapted to large-scale production, as well as allowing sensory analysis of the final product. A number of potential adjuncts may be considered in the future, and, apart from flavor-enhancing strains, adjuncts with probiotic characteristics might also be worthy of analysis, given their associated health benefits. If such strains are to be examined, it should be ensured that the acquisition of lacticin 3147 resistance does not somehow compromise the health-promoting properties of the strain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded in part by grant aid under the Food Sub-Programme of the Operational Programme for Industrial Development, which is administered by the Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry and which is supported by national and European Union funds. M.P.R was supported by the Teagasc Walsh Fellowship Programme.

We thank Sheila Morgan for helpful discussion and experimental assistance and Fergal Lawless for fatty acid analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Broome M C, Krause D A, Hickey M W. The use of non-starter lactobacilli in cheddar cheese manufacture. Aust J Dairy Technol. 1990;45:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coakley M, Fitzgerald G F, Ross R P. Application and evaluation of the phage resistance- and bacteriocin-encoding plasmid pMRC01 for the improvement of dairy starter cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1434–1440. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1434-1440.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies E A, Adams M R. Resistance of Listeria monocytogenes to the bacteriocin nisin. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;21:341–347. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies E A, Falahee M B, Adams M R. Involvement of the cell envelope of Listeria monocytogenes in the acquisition of nisin resistance. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb04491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dougherty B A, Hill C, Weidman J F, Richardson D R, Venter J C, Ross R P. Sequence and analysis of the 60 kb conjugative, bacteriocin-producing plasmid pMRC01 from Lactococcus lactis DPC3147. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1029–1038. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenelon M A, Ryan M P, Rea M C, Guinee T P, Ross R P, Hill C, Harrington D. Elevated temperature ripening of reduced fat cheddar made with or without lacticin 3147 producing starter culture. J Dairy Sci. 1999;82:10–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox P F, McSweeney P L H, Lynch C M. Significance of non-starter lactic acid bacteria in cheddar cheese. Aust J Dairy Technol. 1998;53:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giles J, Lawrence R C. The assessment of cheddar cheese quality by compositional analysis. N Z J Dairy Sci Technol. 1973;8:148–151. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guinee T P, Pudja P D, Mulholland E O. Effect of milk protein standardization by ultrafiltration on the manufacture, composition and maturation of cheddar cheese. J Dairy Res. 1994;61:117–131. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris L J, Fleming H P, Klaenhammer T R. Sensitivity and resistance of Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115, Scott A and UAL500 to nisin. J Food Prot. 1991;54:836–840. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-54.11.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayarao B M, Oliver S P. Polymerase chain reaction-based DNA fingerprinting for identification of Streptococcus and Enterococcus species isolated from bovine milk. J Food Prot. 1994;57:240–245. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-57.3.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansson M L, Quednau M, Molin G, Ahrne S. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) for rapid typing of Lactobacillus plantarum strains. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;3:155–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch C M, McSweeney P L H, Fox P F, Cogan T M, Drinan F B. Contribution of starter lactococci and non-starter lactobacilli to proteolysis in cheddar cheese with a controlled microflora. Lait. 1997;77:441–459. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch C M, McSweeney P L H, Fox P F, Cogan T M, Drinan F B. Manufacture of cheddar cheese with and without adjunct lactobacilli under controlled microbiological conditions. Int Dairy J. 1996;6:851–867. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maisnier-Patin S, Richard J. Cell wall changes in nisin-resistant variants of Listeria innocua grown in the presence of high nisin concentrations. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;140:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAuliffe O, Hill C, Ross R P. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes in cottage cheese manufactured with a lacticin 3147 producing starter culture. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:251–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAuliffe O, Ryan M P, Ross R P, Hill C, Breeuwer P, Abee T. Lacticin 3147, a broad-spectrum bacteriocin which selectively dissipates the membrane potential. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:439–445. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.439-445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ming X, Daeschel M A. Correlation of cellular phospholipid content with nisin resistance of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. J Food Prot. 1995;58:416–420. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-58.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ming X, Daeschel M A. Nisin resistance of foodborne bacteria and the specific resistance responses of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. J Food Prot. 1993;56:944–948. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-56.11.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muir D D, Banks J M, Hunter E A. Sensory properties of cheddar cheese: effect of starter type and adjunct. Int Dairy J. 1996;6:407–423. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Sullivan D, Coffey A, Fitzgerald G F, Hill C, Ross R P. Design of a phage-insensitive lactococcal dairy starter via sequential transfer of naturally occurring conjugative plasmids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4618–4622. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4618-4622.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pot B, Hertel C, Ludwig W, Descheemaeker P, Kersters K, Schleifer K H. Identification and classification of Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. gasseri, and L. johnsonii strains by SDS-PAGE and rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe hybridization. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:513–517. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-3-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puchades R, Lemieux L, Simard R E. Evolution of free amino acids during the ripening of cheddar cheese containing added Lactobacillus strains. J Food Sci. 1989;54:885–888. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross R P, Galvin M, McAuliffe O, Morgan S M, Ryan M P, Twomey D P, Meaney W J, Hill C. Developing applications for lactococcal bacteriocins, examples using the broad-spectrum lacticin 3147 and the narrow spectrum lactococcins A, B and M. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:337–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan M P, Rea M C, Hill C, Ross R P. An application in cheddar cheese manufacture for a strain of Lactococcus lactis producing a novel broad-spectrum bacteriocin, lacticin 3147. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:612–619. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.612-619.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan M P, Meaney W J, Ross R P, Hill C. Evaluation of lacticin 3147 and a teat seal containing bacteriocin for the inhibition of mastitis pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2287–2290. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2287-2290.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas T D, Crow V L. Mechanism of D(-)-lactic acid formation in cheddar cheese. N Z J Dairy Sci Technol. 1983;18:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trepanier G, Simard R E, Lee B H. Lactic acid bacteria relation to accelerated maturation of cheddar cheese. J Food Sci. 1991;57:898–902. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Schaik W, Gahan C G M, Hill C. Acid adapted Listeria monocytogenes display enhanced tolerance against the lantibiotics nisin and lacticin 3147. J Food Prot. 1999;62:536–539. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-62.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verheul A, Russell N J, van T'Hof R, Rombouts F M, Abee T. Modification of membrane phospholipid composition in nisin-resistant Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3451–3457. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3451-3457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]