Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to assess the feasibility of a national pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) programme using smartphone‐compatible data collection.

Methods

This was a multicentre cohort study (NCT03893188) enrolling individuals interested in PrEP in Switzerland. All centres participate in the SwissPrEPared programme, which uses smartphone‐compatible data collection. Feasibility was assessed after centres had enrolled at least one participant. Participants were HIV‐negative individuals presenting for PrEP counselling. Outcomes were participation (number enrolled/number eligible), enrolment rates (number enrolled per month), retention at first follow‐up (number with first follow‐up/number enrolled), and uptake (proportion attending first visit as scheduled). Participant characteristics were compared between those retained after baseline assessment and those who dropped out.

Results

Between April 2019 and January 2020, 987 individuals were assessed for eligibility, of whom 969 were enrolled (participation: 98.2%). The median enrolment rate was 86 per month [interquartile range (IQR) 52–137]. Retention at first follow‐up and uptake were both 80.7% (782/969 and 532/659, respectively). At enrolment, the median age was 40 (IQR 33–47) years, 95% were men who have sex with men, 47% had a university degree, and 75.5% were already taking PrEP. Most reported multiple casual partners (89.2%), previous sexually transmitted infections (74%) and sexualized drug use (73.1%). At baseline, 25.5% tested positive for either syphilis, gonorrhoea or chlamydia. Participants who dropped out were at lower risk of HIV infection than those retained after baseline assessment.

Conclusions

In a national PrEP programme using smartphone‐compatible data collection, participation, retention and uptake were high. Participants retained after baseline assessment were at considerable risk of HIV infection. Younger, less educated individuals were underrepresented in the SwissPrEPared cohort.

Keywords: cohort study, HIV, pre‐exposure prophylaxis, prevention programme

INTRODUCTION

Since its approval in 2016 by the European Medicines Agency, pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been widely used to prevent HIV transmission as an alternative or in addition to conventional prevention measures. As of November 2019, 16 out of 53 countries in Europe and Central Asia reported PrEP reimbursement as part of their national health services [1]. Despite approval in neighbouring countries and growing interest among target populations [such as men who have sex with men (MSM)] [2], PrEP use in Switzerland remained off‐label and poorly controlled (e.g. online purchase without medical prescription or in neighbouring countries) until recently (approval: April 2020). Taking PrEP without medical oversight is of concern, because of possible drug‐related side effects, poor adherence and viral resistance (e.g. in those taking PrEP despite an undiagnosed HIV infection or in those newly infected despite PrEP) [3, 4].

Whilst there is growing evidence that wide PrEP availability contributes to reducing HIV infection rates [5, 6, 7, 8], concerns have been raised as to whether the current resurgence of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as gonorrhoea, chlamydia, syphilis and viral hepatitis, could be attributed to PrEP [9, 10, 11]. Although changes in sexual behaviour, such as an increase in condomless sex after PrEP start, have been associated with PrEP use [12, 13], these findings have been inconsistent [14, 15], and it remains unclear to what extent other factors, such as differences in STI screening rates, may also contribute to the recent rise in STIs.

To address these points, the SwissPrEPared programme (https://www.swissprepared.ch/en) was launched in April 2019. The goals of this national PrEP programme are to provide personalized prevention measures to individuals at considerable risk of HIV infection, to harmonize quality standards of PrEP consultations across Switzerland, and to serve as an official exchange and training platform for health care providers involved in PrEP prescription. Counselling is based on standardized, online, smartphone‐compatible questionnaires that participants complete before their visit. Yearly data analysis and direct feedback from participants and study centres allow continuous adjustments of the programme format. Nested within this prevention programme, the SwissPrEPared cohort study (NCT03893188) follows programme participants longitudinally over a 3‐year period, with the following research objectives: to obtain epidemiological data on PrEP use in Switzerland, to monitor STIs, and to evaluate sexual health and wellbeing in individuals interested in PrEP.

Because the implementation of a national PrEP programme using online, smartphone‐compatible data collection for counselling remains challenging, the primary aim of this study was to provide feasibility data after each participating centre had enrolled at least one participant. More specifically, we assessed participation, enrolment rates, retention at first follow‐up and uptake. We were also interested in exploring the relatively early cohort profile and assessed participant characteristics at cohort registration.

METHODS

We followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for the reporting of feasibility studies [16].

Patient consent statement

The SwissPrEPared study was approved by all ethical committees in cantons with a participating centre (lead canton: Zurich, Switzerland; registration number: 2018–02015) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03893188). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study. No research data were collected from programme participants not explicitly consenting to the SwissPrEPared cohort study.

Study design and setting

The SwissPrEPared study is a national, multicentre cohort study that follows individuals interested in PrEP over a period of 3 years (April 2019 to March 2022). Recruiting centres are located in the seven main cities of Switzerland and consisted, at the time of the feasibility analysis, of seven tertiary referral hospitals, two sexual health clinics (‘Checkpoints’) and two private clinical practices (general practitioner and dermatologist). The study was implemented in April 2019 across Switzerland used a stepwise approach, with centres in the canton of Zurich starting first and those in the French/Italian‐speaking regions last.

All participating centres are part of the SwissPrEPared programme (also launched in April 2019), which ensures standardization of PrEP counselling and STI screening across providers in the three main linguistic regions of Switzerland (German‐, French‐ and Italian‐speaking). This is mainly achieved through the use of common guidelines, a secured web‐based electronic chart system (consisting of standardized questionnaires for PrEP counselling), and regular interactions between PrEP prescribers (e.g. yearly meetings, training and newsletters). Programme participants receive PrEP counselling and STI screening at regular intervals, following the latest international recommendations (i.e. safety visit 4 weeks after initiation in those starting PrEP, and visit every 3 months in those already on daily PrEP at enrolment) [17]. For those taking PrEP intermittently [i.e. either daily for limited periods of time (‘holiday PrEP’) or before and after sex (‘event‐based’)] [18], screening was recommended at least every 6 months, but could be performed earlier depending on the frequency of sexual contacts (at the physician’s discretion). Counselling and clinical management are facilitated by standardized, online, smartphone‐compatible questionnaires that participants complete before their scheduled counselling visit. These questionnaires are made available to participants a week before the scheduled PrEP consultation by sending them a link (via email or short message service) enabling completion on their personal electronic devices. In 2018, at least 85% of the general population in Switzerland were active smartphone users [19]. A similar trend was found in the MSM population, with reports suggesting use of online platforms in > 75% of the respondents [20, 21].

From April to September 2019, PrEP was mainly obtained from regular Swiss pharmacies (available only with medical prescription), but other sources included online pharmacies and buying/importing PrEP from other countries. As from October 2019, programme participants were given the opportunity to buy PrEP within the SwissPrEPared programme at a preferential price compared to purchasing PrEP in regular Swiss pharmacies.

Study participants

Target populations (MSM and other groups at considerable risk of HIV infection) were informed of programme and study enrolment in print and online magazines. All HIV‐negative individuals presenting for PrEP counselling at participating centres were considered eligible. Those with no indication for PrEP (based on prescription guidelines used by study centres) or those declining further PrEP use were not excluded, provided that they planned to attend at least one follow‐up visit (e.g. for STI screening or revaluation of PrEP). Although the SwissPrEPared study was not restricted to MSM, we anticipated only a small number of participants outside this group.

Evidence suggests that nearly 80 000 MSM aged 15–64 years are living in Switzerland (95% credible interval: 64 000–96 000), of whom 8% (6300 MSM) have been estimated to have diagnosed or undiagnosed HIV infection [22]. Thus, assuming that 14% of non‐HIV‐diagnosed MSM would be very likely to use PrEP [1], we expected that 10 300 MSM (upper limit) in Switzerland would qualify for the SwissPrEPared programme.

Study outcomes

Feasibility outcomes were defined as: participation (number of enrolled participants divided by the number of potentially eligible individuals), enrolment rates (number of participants enrolled per month), retention at first follow‐up (number of participants with first follow‐up visit divided by the number enrolled), and reasons for withdrawing consent. Uptake of the SwissPrEPared programme was defined as the proportion of participants attending the first follow‐up visit as scheduled (i.e. 3 months ± 2 weeks after baseline assessment for those already on daily PrEP, and 4 weeks for those starting PrEP at enrolment). Programme uptake was not assessed for those taking PrEP intermittently (i.e. ‘holiday’ or ‘event‐based’ PrEP), as the schedule for follow‐up visits may differ between centres. For participation and enrolment rates, assessment was performed after cohort deployment, that is, after each participating centre had enrolled at least one participant. Retention at first follow‐up was assessed 6 months after cohort deployment to account for participants not strictly adhering to the study schedule and included participants with any first follow‐up visit, irrespective of the visit schedule.

We also explored participant characteristics at cohort registration (referred to as ‘baseline’) to better define the PrEP user population in Switzerland at an early stage of the study. All participants who contributed to the baseline assessment were considered; that is, those lost to follow‐up or those withdrawing consent after the initial visit were also included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics were compared between those retained in the study after the baseline assessment (i.e. those with a baseline assessment and pending first follow‐up visit) and those who dropped out after the baseline assessment. We assessed demographics [age, gender, sexual orientation, risk group, education, financial situation (self‐reported, subjective assessment) and country of origin], PrEP use (current use, mode of purchase and detailed regimen), PrEP adherence (self‐reported frequency of missing a PrEP dose), behavioural risk factors [number of partners (steady and casual in the previous 3 months), sex with casual partners, use of condoms, previous lifetime STI diagnosis and substance use in the previous 3 months], and results from STI screening at baseline. For substance use, reported substances were stratified into three categories [23]: ‘chemsex’ substances (γ‐hydroxybutyric acid/γ‐butyrolactone, methamphetamine, ketamine, mephedrone and synthetic stimulants other than mephedrone), sex‐enhancing substances other than chemsex substances [cocaine, 3,4‐methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy/3,4‐methylenedioxymethamphetamine), amyl nitrite and amphetamine], and other substances (including alcohol). Assessment of STIs included the following: syphilis [Treponema pallidum haemagglutination (TPHA), followed by Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) or rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test if positive; or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from ulcers], chlamydia and gonorrhoea (pooled PCR from rectal, pharyngeal and urethral swabs), and hepatitis C [hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies and, if positive, reverse transcriptase PCR]. Screening for STIs was performed irrespective of the presence or absence of symptoms. Each centre performed the diagnostic tests that were used in their routine laboratories.

Statistical methods

The primary aim of this feasibility report was descriptive; that is, we assessed participation, enrolment rates and retention at first follow‐up, reasons for withdrawing consent, programme uptake, and baseline participant characteristics. Categorical variables were expressed as proportions, and continuous variables as median and interquartile range (IQR). We compared participant characteristics between those with baseline assessment retained in the study and those who dropped out. Two‐sided tests were performed (Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables; Fisher exact test for binary variables), and a level of significance of 0.05 was used. All statistical analyses were conducted in r, version 3.6.1.

RESULTS

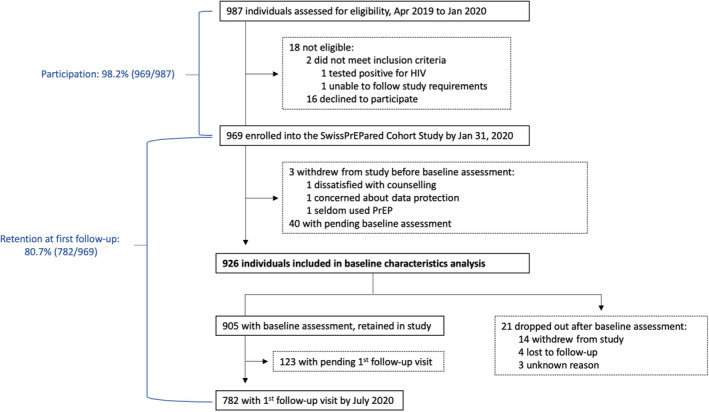

Full cohort recruitment had occurred by the end of January 2020, after 10 months of enrolment conducted by 11 participating centres. Between 10 April 2019 and 31 January 2020, 987 individuals were assessed for eligibility (Figure 1). Of these, two were deemed ineligible (one tested positive for HIV and one was unable to meet the study requirements), and 16 declined study participation, which corresponded to a participation rate of 98.2% (969/987). Monthly enrolment rates increased over time (Figure S1a), reflecting stepwise study implementation across Switzerland (Figure S1b). A median of 86 participants were enrolled per month (IQR 52–137), over nearly 10 months.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Of 969 enrolled participants, baseline assessment was still pending in 40, whilst three withdrew consent before the initial assessment. Thus, 926 participants were included in the analysis of baseline characteristics: 905 had a baseline visit and were scheduled for first follow‐up (thus considered retained in the study), whilst 21 dropped out after the baseline assessment. Of these, 14 withdrew consent because they either stopped or did not initiate PrEP (n = 10), had no time to participate (n = 2), expressed concerns about a potential increase in STIs or adverse drug reactions related to PrEP (n = 1), or found counselling questions too intrusive (n = 1) (Figure S2). Four participants were considered lost to follow‐up (three left Switzerland and one died for a reason unrelated to the study). In three cases, no reason for dropping out was reported.

Retention at first follow‐up was 80.7% (782/969) (Figure 1). Programme uptake was 80.7%, with 532 out of 659 study participants adhering to the visit schedule: among those on daily PrEP at baseline or those who started PrEP at baseline, the median time between baseline assessment and first follow‐up visit was 13 weeks (IQR 10–14 weeks; Figure S3).

Baseline characteristics of the 926 participants included in the analysis are presented in Table 1. The median age was 40 years (IQR 33–47 years). Participants were predominantly MSM (880/926; 95%) and born in Switzerland (546/926; 59%), with a university degree (435/926; 47%) and a comfortable financial situation (471/926; 50.9%). Individuals defining themselves as female constituted 1.4% of the study cohort. Participants retained in the study after baseline assessment were more likely to possess a university degree compared to those who dropped out. Other baseline characteristics were well balanced between groups.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the SwissPrEPared participants

|

Total (n = 926) |

Retained in study (n = 905) |

Dropouts (n = 21) |

P‐value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [median (IQR)] | 40 (33–47) | 39 (33–47) | 41 (34–54) | 0.292 |

| Gender [n (%)] | ||||

| Male | 907 (97.9) | 886 (97.9) | 21 (100) | 1.0 |

| Cis b ‐male | 904 (99.7) | 883 (99.7) | 21 (100) | |

| Trans c ‐male | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Female | 13 (1.4) | 13 (1.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Cis b ‐female | 4 (30.8) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Trans c ‐female | 9 (69.2) | 9 (69.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Nonbinary | 6 (0.6) | 6 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Sexual orientation [n (%)] | ||||

| Homosexual | 833 (90.0) | 815 (90.1) | 18 (85.7) | 0.467 |

| Bisexual | 58 (6.3) | 56 (6.2) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Heterosexual | 11 (1.2) | 11 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Not defined | 24 (2.6) | 23 (2.5) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Risk group [n (%)] | ||||

| MSM | 880 (95.0) | 860 (95.0) | 20 (95.2) | 0.661 |

| Cis b ‐MSM | 877 (99.7) | 857 (99.7) | 20 (100) | |

| Trans c ‐MSM | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Heterosexual | 11 (1.2) | 11 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Cis b | 9 (81.8) | 9 (81.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Trans c | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 35 (3.8) | 34 (3.8) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Education [n (%)] | ||||

| University | 435 (47.0) | 433 (47.8) | 2 (9.5) | 0.001 |

| Apprenticeship | 171 (18.5) | 167 (18.5) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Higher education (not university) | 99 (10.7) | 92 (10.2) | 7 (33.3) | |

| High school/Baccalaureate | 72 (7.8) | 70 (7.7) | 2 (9.5) | |

| No or compulsory school | 11 (1.2) | 11 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 138 (14.9) | 132 (14.6) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Financial situation [n (%)] | ||||

| Very comfortable | 191 (20.6) | 189 (20.9) | 2 (9.5) | 0.447 |

| Comfortable | 471 (50.9) | 459 (50.7) | 12 (57.1) | |

| Neither comfortable nor difficult | 194 (21.0) | 187 (20.7) | 7 (33.3) | |

| Difficult | 48 (5.2) | 48 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Very difficult | 22 (2.4) | 22 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Country of origin [n (%)] | ||||

| Switzerland | 546 (59.0) | 531 (58.7) | 15 (71.4) | 0.723 |

| Germany | 104 (11.2) | 103 (11.4) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Brazil | 23 (2.5) | 23 (2.5) | 0 (0) | |

| France | 22 (2.4) | 21 (2.3) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Italy | 18 (1.9) | 18 (2.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other (each < 18 participants) | 213 (23.0) | 209 (23.1) | 4 (19.0) | |

| European countries | 91 (42.7) | 89 (42.6) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Non‐European countries | 122 (57.3) | 120 (57.4) | 2 (50.0) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables; Fisher exact test for binary variables.

Cis refers to individuals for whom sex assigned at birth matches gender identity.

Trans refers to a discrepancy between sex assigned at birth and the reported gender identity.

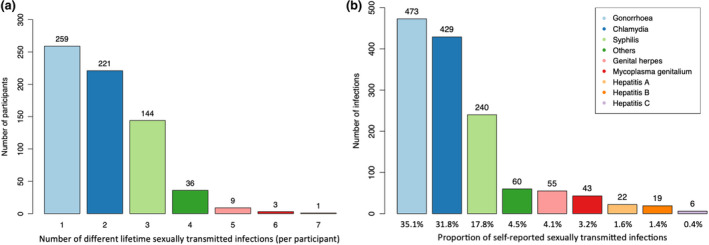

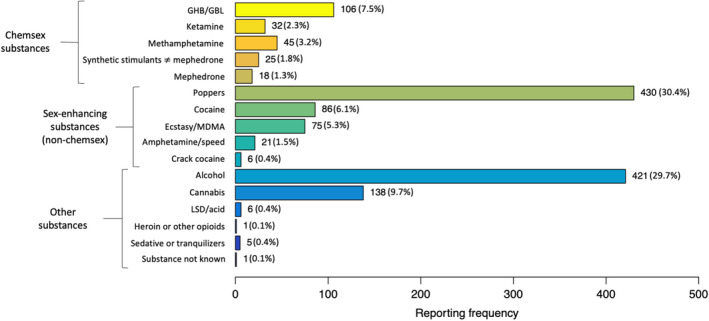

Table 2 outlines data on PrEP use and behavioural risk factors. Most participants were taking daily PrEP at baseline (687/910; 75.5%), which they purchased with a medical prescription in a regular pharmacy in Switzerland. In those taking daily PrEP for a limited period of time (‘holiday PrEP’), the median intake was 2 days (IQR 1–5 days) before and 2 days (IQR 2–3.5 days) after sexual exposure. In those using an ‘event‐based’ regimen [18], it was 1 day (IQR 1–1 days) before and 2 days (IQR 2–3 days) after. Assessment of PrEP adherence revealed that 60% (317/528) of daily, 59.3% (35/59) of holiday, and 74.2% (66/89) of event‐based PrEP users never missed taking their medication. In those missing a dose, this was mostly the case once a month (daily PrEP) or once/twice (other regimens). The vast majority had sex with casual partners (812/910; 89.2%), for which 12.7% reported systematic use of condoms. Previous use of post‐exposure prophylaxis was reported by 29.8% of the study participants. The median number of sexual partners in the previous 3 months was 5 (IQR 2–10). Previous lifetime STIs were reported by 74% (673/910) of the study participants. Among those, most reported 1 to 3 different STIs (Figure 2a). The most commonly self‐reported infection was gonorrhoea (35.1%), followed by chlamydia (31.8%) and syphilis (17.8%) (Figure 2b). The vast majority (93.5%) reported substance use (including alcohol consumption) in the previous 3 months. Substance use in a sexual context was reported by 665 participants (73.1%), of whom 74.6% (496/665) used either chemsex substances or sex‐enhancing drugs other than chemsex substances (Figure 3).

TABLE 2.

Pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use and behavioural risk factors among SwissPrEPared participants

|

Total (n = 910) |

Retained in study (n = 890) |

Dropouts (n = 20) |

P‐value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taking PrEP at baseline [n (%)] | 687 (75.5) | 678 (76.2) | 9 (45.0) | 0.003 |

| PrEP regimen at baseline [n (%)] | ||||

| Daily, constant | 528 (76.9) | 523 (77.1) | 5 (55.6) | 0.080 |

| Before and after planned sex (‘event‐based’) | 89 (13.0) | 87 (12.8) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Daily, limited time periods (‘holiday PrEP’) | 59 (8.6) | 58 (8.6) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Other regimen | 11 (1.6) | 10 (1.5) | 1 (11.1) | |

| PrEP intake: daily, for limited time periods [median (IQR)] | ||||

| Days before | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) | 1 (1–1) | 0.320 |

| Days after | 2 (2–3.5) | 2 (2–3.75) | 2 (2–2) | 0.475 |

| Number of days on PrEP (past 3 months) | 38 (17–60) | 39 (16–60) | 36 (36–36) | 0.953 |

| PrEP intake: event‐based regimen [median (IQR)] | ||||

| Days before | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1.5 (1.25–1.75) | 0.297 |

| Days after | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2.5–3.5) | 0.353 |

| Number of days on PrEP (past 3 months) | 20 (15–35) | 20 (15–36) | 12 (7–16) | 0.206 |

| PrEP adherence (i.e. frequency of missed medication) [n (%)] | ||||

| In daily PrEP users | (n = 528) | |||

| Never | 317 (60.0) | 313 (59.8) | 4 (80.0) | 0.915 |

| Once a month | 169 (32.0) | 168 (32.1) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Once every second week | 34 (6.4) | 34 (6.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Once a week | 7 (1.3) | 7 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

| More than once a week | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| In ‘holiday PrEP’ users | (n = 59) | |||

| Never | 35 (59.3) | 34 (58.6) | 1 (100.0) | 0.874 |

| Once or twice | 21 (35.6) | 21 (36.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Three to five times | 2 (3.4) | 2 (3.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Six to 10 times | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | |

| More than 10 times | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| In ‘event‐based’ PrEP users | (n = 89) | |||

| Never | 66 (74.2) | 64 (73.6) | 2 (100) | 0.700 |

| Once or twice | 22 (24.7) | 22 (25.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Three to five times | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Six to 10 times | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| More than 10 times | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Purchase mode [n (%)] | ||||

| In a regular pharmacy in Switzerland | 233 (34.0) | 230 (34.0) | 3 (33.3) | 0.757 |

| Through the SwissPrEPared programme (option available as from Oct 2019) | 145 (21.1) | 143 (21.1) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Online pharmacy (outside Europe) | 137 (20.0) | 136 (20.1) | 1 (11.1) | |

| In a regular pharmacy outside Switzerland | 108 (15.7) | 105 (15.5) | 3 (33.3) | |

| Online pharmacy (Europe) | 46 (6.7) | 46 (6.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Other mode | 17 (2.5) | 17 (2.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Number of sexual partners in previous 3 months [median (IQR)] | 5 (2–10) | 5 (2–10) | 2 (1–4) | 0.003 |

| Sex with casual partners [n (%)] | 812 (89.2) | 795 (89.3) | 17 (85.0) | 0.467 |

| Condom use with casual partners [n (%)] | ||||

| Never | 326 (35.8) | 320 (36.0) | 6 (30.0) | 0.022 |

| Sometimes | 316 (34.7) | 313 (35.2) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Mostly | 152 (16.7) | 148 (16.6) | 4 (20.0) | |

| Always | 116 (12.7) | 109 (12.2) | 7 (35.0) | |

| Previous use of post‐exposure prophylaxis [n (%)] | 271 (29.8) | 267 (30.0) | 4 (20.0) | 0.460 |

| Previous sexually transmitted infection [n (%)] | 673 (74.0) | 663 (74.5) | 10 (50.0) | 0.020 |

| Substance use, past 3 months [n (%)] | ||||

| Any substance use (including alcohol) | 851 (93.5) | 832 (93.5) | 19 (95.0) | 1.0 |

| Substance use in a sexual context (including alcohol) | 665 (73.1) | 654 (73.5) | 11 (55.0) | 0.076 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables; Fisher exact test for binary variables.

FIGURE 2.

Number of different previous sexually transmitted infections (STIs) self‐reported at baseline (a) and type of self‐reported STIs (b) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

FIGURE 3.

Substances used before/during sex in the previous 3 months among 665 SwissPrEPared participants. GHB/GBL, γ‐hydroxybutyric acid/γ‐butyrolactone; LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; ecstasy/MDMA, 3,4‐methylenedioxymethamphetamine [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Compared to those retained in study after baseline assessment, participants who dropped out were significantly less likely to take PrEP at baseline, had fewer sexual partners, were more likely to always use condoms with casual partners and were less likely to report previous lifetime STIs. Although not statistically significant, substance use in a sexual context was less frequent in participants who dropped out.

Results of STI screening at the baseline visit are provided in Table 3: 9.6% of study participants tested positive for gonorrhoea, 11.3% for chlamydia, and 3.7% for syphilis. There was no positive hepatitis C screening test. Overall, 25.5% tested positive for any of these STIs. Although not statistically significant, participants retained in the study after baseline assessment had a higher prevalence of STIs at baseline than those who dropped out.

TABLE 3.

Results of screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) at baseline visit

|

Total n (%) |

Retained in study n (%) |

Dropouts n (%) |

P‐value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any of the STIs listed below | ||||

| Negative | 438 (74.5) | 429 (74.2) | 9 (90.0) | 0.465 |

| Positive | 150 (25.5) | 149 (25.8) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Gonorrhoea | ||||

| Negative | 642 (90.4) | 628 (90.2) | 14 (100) | 0.383 |

| Positive | 68 (9.6) | 68 (9.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Chlamydia | ||||

| Negative | 630 (88.7) | 616 (88.5) | 14 (100) | 0.387 |

| Positive | 80 (11.3) | 80 (11.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Syphilis | ||||

| Negative | 704 (96.3) | 689 (96.4) | 15 (93.8) | 0.456 |

| Positive | 27 (3.7) | 26 (3.6) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Hepatitis C | ||||

| Negative | 606 (100) | 595 (100) | 11 (100) | NA |

| Positive | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables; Fisher exact test for binary variables.

DISCUSSION

In this feasibility assessment conducted 10 months after the initiation of a large, multicentre cohort study on PrEP, participation, retention at first follow‐up and programme uptake were high (98.2, 80.7 and 80.7%, respectively). Of 926 included individuals, most were middle‐aged, well‐educated MSM on PrEP at baseline, with overall good PrEP adherence. The majority reported multiple casual partners, inconsistent condom use, previous STI and substance use in a sexual context. At baseline, > 25% of the participants tested positive for syphilis, gonorrhoea or chlamydia. None of the participants were found to be positive for HCV.

In this study, we found high participation and high retention at first follow‐up, and high programme uptake, with > 80% of the participants adhering to the anticipated visit schedule of the SwissPrEPared programme. Of 969 enrolled participants, only five withdrew for reasons related to the design of the PrEP programme. These findings may reflect the growing need for large‐scale PrEP programmes with integrated, comprehensive care. Our study findings are in line with those of two PrEP implementation studies conducted in Australia that showed widespread interest, rapid enrolment, and high retention among gay, bisexual and other MSM [24, 25]. The high participation and retention at first follow‐up might also be related to the innovative design of the questionnaires used in the SwissPrEPared programme, which consisted of self‐reported data collected through online, self‐administered questionnaires compatible with smartphones. This particular design may also have contributed to minimizing the risk of social desirability bias and interviewer bias, which may occur when collecting data of a sensitive nature [26]. These assumptions will be further explored through the introduction of specific feedback forms assessing end‐user experience (implementation planned in spring 2022).

Further exploratory analyses revealed that the small number of participants who dropped out exhibited a different risk profile from those retained in the study after the baseline assessment: less prone to use PrEP at baseline, these participants also reported fewer sexual partners, more systematic condom use, fewer previous STIs and less substance use in a sexual context. Among those declining further study participation, forgoing or stopping PrEP (e.g. because they were in a stable relationship) was the most frequently reported reason. These findings seem to indicate that the SwissPrEPared programme is not only targeted at, but also adequately retaining those at considerable risk of HIV infection.

Participants in our study were found to have higher proportions of positive STI‐screening test results at baseline compared to previous reports [10, 27, 28, 29]. One reason for this discrepancy may lie in the large proportion of participants already on PrEP at baseline (75.5%), in whom some degree of behavioural risk compensation may have already occurred at the time of enrolment [30, 31, 32, 33], although the association between PrEP and risk compensation has been recently hotly debated [34]. This large proportion of PrEP users contrasts with other PrEP cohorts, which included mostly PrEP‐naïve participants [10, 24, 35, 36]. The large on‐PrEP population seen in our study may be attributable to several factors, such as high PrEP awareness and demand (as suggested by an online survey conducted in January 2017 among MSM in Switzerland) [2], pre‐existing structures facilitating access to PrEP (e.g. sexual health clinics), and PrEP access through alternative channels (e.g. online or from neighbouring countries).

This study has some limitations. Firstly, even though the assessment was performed after cohort implementation in the seven main cities of Switzerland, one centre dominated the analysis (‘Checkpoint Zurich’, i.e. centre 1; Figure S1b). Although this limits the generalizability of our findings (i.e. population characteristics may vary according to recruitment site), it also underlines the importance of checkpoints for the sexual health of MSM [37]. Future reassessments of the SwissPrEPared cohort will provide centre‐specific data, and a more granular picture of MSM and other groups at considerable risk of HIV infection (such as trans women) seeking PrEP in Switzerland. Secondly, the cohort profile assessment identified a middle‐aged, cis‐gender, homosexually identified, well‐educated study population, with good PrEP adherence. Although this profile is partly consistent with other PrEP cohorts [10, 24, 35, 36], it also indicates that current efforts should be focused on the enrolment of younger, less educated individuals with lower PrEP awareness who might be at higher risk of HIV infection [38]. Several approaches have been described to improve the recruitment of younger individuals belonging to a sexual minority, such as particular sampling strategies (e.g. venue‐based or snowball sampling methods), internet‐based recruitment (e.g. targeted advertisement on social media or on geosocial networking applications such as Grindr®), the involvement of community‐based organizations, financial incentives, and the promotion of a nonstigmatizing attitude in health care providers [39, 40, 41]. Some of these measures – such as advertisement on social media or free‐of‐charge STI screening for subgroups deemed vulnerable – should soon be implemented in the SwissPrEPared cohort study. Thirdly, although enrolment into the SwissPrEPared cohort is not restricted to PrEP users, most participants tended to withdraw consent when forgoing or interrupting PrEP. However, as individuals discontinuing PrEP have been found to be at much higher risk of contracting HIV infection than their on‐PrEP counterparts [35, 42, 43, 44], particular attention should be paid to ensure continuity of care and to evaluate PrEP reinitiation in this specific subgroup.

In this study, we assessed the feasibility and uptake of a PrEP programme among MSM and – to a lesser extent – among other groups at considerable risk of HIV infection. We found high participation, retention at first follow‐up and programme uptake in MSM and confirmed that participants retained in the study after the baseline assessment were at considerable risk of HIV infection. Through this assessment, we were also able to identify that younger, less educated individuals with lower PrEP awareness were underrepresented in our cohort. These individuals will be the focus of efforts throughout the next enrolment phases of the SwissPrEPared cohort study.

Conflicts of interest

The institution of EB received fees for his participation on advisory boards and travel grants from Gilead Sciences, MSD, ViiV Healthcare, Abbvie, Pfizer, and Sandoz. DLB received honoraria for advisory board participation from Gilead Sciences, MSD and ViiV Healthcare. The institution of KD received research funding unrelated to this publication from Gilead Sciences and sponsorship for attendance at specialist meetings from MSD. MS is an advisory board member of Gilead Sciences, MSD and ViiV Healthcare, and received travel grants from Gilead Sciences. The institution of BS received travel grants from Gilead Sciences. The institution of PT received grants and advisory fees from ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences, outside the submitted work. JSF received research grants unrelated to the submitted work from Merck & Co, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare. The institution of BH received research and travel grants from ViiV Healthcare, MSD and Gilead Sciences. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. Open Access Funding provided by Universitat Zurich.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

FH, EM, MRe, RDK, JSF and BH participated in study conception and design, data acquisition and interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. FH and EM produced the first draft of the manuscript. FH and RDK performed the statistical analyses. MRa, EB, EBEA, DLB, AC, KD, VC, CD, CH, SL, JN, MS, BS and PV participated in data acquisition and critical revision of the manuscript. PB, PT, DH, AJS, RB, NL, AL and JB participated in study conception and design, and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors listed on the title page have read the manuscript, attest to the validity and legitimacy of the data and its interpretation, and agree to its submission.

Supporting information

App S1

Hovaguimian F, Martin E, Reinacher M, et al. Participation, retention and uptake in a multicentre pre‐exposure prophylaxis cohort using online, smartphone‐compatible data collection. HIV Med. 2022;23:146–158. 10.1111/hiv.13175

Funding information

This work was supported by the Federal Office of Public Health (approval number: 19.022422), Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (grant number: SHCS_281). FH and BH were supported by the Federal Office of Public Health (approval number: 19.022422); FH and RDK were supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant #BSSGI0_155851). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung

Swiss HIV Cohort Study

Federal Office of Public Health

Merck Sharp and Dohme

REFERENCES

- 1. Hayes R, Schmidt AJ, Pharris A, et al. Estimating the ‘PrEP Gap’: how implementation and access to PrEP differ between countries in Europe and Central Asia in 2019. Euro Surveill. 2019;24:1900598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hampel B, Kusejko K, Braun DL, Harrison‐Quintana J, Kouyos R, Fehr J. Assessing the need for a pre‐exposure prophylaxis programme using the social media app Grindr(R). HIV Med. 2017;18:772‐776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gibas KM, van den Berg P, Powell VE, Krakower DS. Drug resistance during HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis. Drugs. 2019;79:609‐619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pilkington V, Hill A, Hughes S, Nwokolo N, Pozniak A. How safe is TDF/FTC as PrEP? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the risk of adverse events in 13 randomised trials of PrEP. J Virus Erad. 2018;4:215‐224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown AE, Mohammed H, Ogaz D, et al. Fall in new HIV diagnoses among men who have sex with men (MSM) at selected London sexual health clinics since early 2015: testing or treatment or pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? Euro Surveill. 2015;2017:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buchbinder SP, Havlir DV. Getting to zero San Francisco: a collective impact approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82(Suppl 3):S176‐S182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nwokolo N, Hill A, McOwan A, Pozniak A. Rapidly declining HIV infection in MSM in central London. Lancet HIV. 2017;4:e482‐e483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whitlock G, Scarfield P, Dean Street Collaborative G . HIV diagnoses continue to fall at 56 Dean Street. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;19:100263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kojima N, Davey DJ, Klausner JD. Pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection and new sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2016;30:2251‐2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Traeger MW, Cornelisse VJ, Asselin J, et al. Association of HIV preexposure prophylaxis with incidence of sexually transmitted infections among individuals at high risk of HIV Infection. JAMA. 2019;321:1380‐1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Werner RN, Gaskins M, Nast A, Dressler C. Incidence of sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men and who are at substantial risk of HIV infection ‐ A meta‐analysis of data from trials and observational studies of HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0208107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Newcomb ME, Moran K, Feinstein BA, Forscher E, Mustanski B. Pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use and condomless anal sex: evidence of risk compensation in a cohort of young men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77:358‐364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Traeger MW, Schroeder SE, Wright EJ, et al. Effects of pre‐exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus infection on sexual risk behavior in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:676‐686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carlo Hojilla J, Koester KA, Cohen SE, et al. Sexual behavior, risk compensation, and HIV prevention strategies among participants in the San Francisco PrEP demonstration project: a qualitative analysis of counseling notes. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:1461‐1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marcus JL, Glidden DV, Mayer KH, et al. No evidence of sexual risk compensation in the iPrEx trial of daily oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. European AIDS Clinical Society . Guidelines Version 10.0. Vol November, 2019.

- 18. Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. On‐demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV‐1 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2237‐2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O'Dea S Forecast of the smartphone user penetration rate in Switzerland 2018‐2024. Vol 2021, Statista, 2020.

- 20. Badal HJ, Stryker JE, DeLuca N, Purcell DW. Swipe right: dating website and app use among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:1265‐1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grov C, Breslow AS, Newcomb ME, Rosenberger JG, Bauermeister JA. Gay and bisexual men's use of the Internet: research from the 1990s through 2013. J Sex Res. 2014;51:390‐409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmidt AJ, Altpeter E. The denominator problem: estimating the size of local populations of men‐who‐have‐sex‐with‐men and rates of HIV and other STIs in Switzerland. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95:285‐291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hampel B, Kusejko K, Kouyos RD, et al. Chemsex drugs on the rise: a longitudinal analysis of the Swiss HIV cohort study from 2007 to 2017. HIV Med. 2020;21:228‐239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grulich AE, Guy R, Amin J, et al. Population‐level effectiveness of rapid, targeted, high‐coverage roll‐out of HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: the EPIC‐NSW prospective cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e629‐e637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryan KE, Asselin J, Fairley CK, et al. Trends in human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted infection testing among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men after rapid scale‐up of preexposure prophylaxis in Victoria, Australia. Sex Transm Dis. 2020;47:516‐524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krumpal I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Qual Quant. 2013;47:2025‐2047. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beymer MR, DeVost MA, Weiss RE, et al. Does HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis use lead to a higher incidence of sexually transmitted infections? A case‐crossover study of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, California. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94:457‐462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lal L, Audsley J, Murphy DA, et al. Medication adherence, condom use and sexually transmitted infections in Australian preexposure prophylaxis users. AIDS. 2017;31:1709‐1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Hare CB, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in a large integrated health care system: adherence, renal safety, and discontinuation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73:540‐546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Coyer L, van den Elshout MAM, Achterbergh RCA, et al. Understanding pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) regimen use: switching and discontinuing daily and event‐driven PrEP among men who have sex with men. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29–30:100650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gafos M, Horne R, Nutland W, et al. The context of sexual risk behaviour among men who have sex with men seeking PrEP, and the impact of PrEP on sexual behaviour. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:1708‐1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre‐exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:820‐829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre‐exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV‐1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open‐label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387:53‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rojas Castro D, Delabre RM, Molina JM. Give PrEP a chance: moving on from the “risk compensation” concept. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(Suppl 6):e25351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Greenwald ZR, Maheu‐Giroux M, Szabo J, et al. Cohort profile: l'Actuel pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) cohort study in Montreal, Canada. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vuylsteke B, Reyniers T, De Baetselier I, et al. Daily and event‐driven pre‐exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men in Belgium: results of a prospective cohort measuring adherence, sexual behaviour and STI incidence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22:e25407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schmidt A. From HIV‐testing to Gay Health Centres: A Mapping of European “Checkpoints". 2017.

- 38. Weber P, Gredig D, Lehner A, Nideröst S. European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS‐2017) ‐ Rapport national de la Suisse. Fachhochschule Nordwestschweiz, Hochschule für Soziale Arbeit, Olten; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, et al. Reaching the hard‐to‐reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jaiswal J, Griffin M, Singer SN, et al. Structural barriers to pre‐exposure prophylaxis use among young sexual minority men: the P18 cohort study. Curr HIV Res. 2018;16: 237‐249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parchem B, Molock SD. Brief report: identified barriers and proposed solutions for recruiting young black sexual minority men in HIV‐related research. J Adolesc. 2021;87:1‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Krakower D, Maloney KM, Powell VE, et al. Patterns and clinical consequences of discontinuing HIV preexposure prophylaxis during primary care. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22:e25250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shover CL, Shoptaw S, Javanbakht M, et al. Mind the gaps: prescription coverage and HIV incidence among patients receiving pre‐exposure prophylaxis from a large federally qualified health center in Los Angeles, California : mind the gaps: cobertura de recetas e incidencia de VIH entre pacientes recibiendo profilaxis pre‐exposicion de un centro de salud grande y federalmente calificado en Los Angeles, CA. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:2730‐2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Spinelli MA, Laborde N, Kinley P, et al. Missed opportunities to prevent HIV infections among pre‐exposure prophylaxis users: a population‐based mixed methods study, San Francisco, United States. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23:e25472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

App S1