With rising expenditure, growing chronic disease burden, and widening inequalities, the health system is in urgent need of redesign

Although Australia has a high performing health system, like most high income countries, it faces unbridled growth in health care spending — now exceeding 10% of the gross domestic product. 1 In New South Wales, universal access to health care is provided for about 8 million people. In 2017–18, NSW had the largest health system expenditure of all Australian states and territories ($57.06 billion or 31% of national health system expenditure); however, on a per capita basis, this was the lowest in the country ($7202 per person). 1 Despite strong performance, it is experiencing growing pressure from chronic diseases, an ageing population, rising inequities, expensive medicines, diagnostics and other technologies, and now the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic.

In 2009, the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission made recommendations in three areas to support a higher performing health system for Australia: tackling inequality, system redesign, and increasing consumer engagement. 2 The most substantive recommendation was removal of federal–state funding siloes. In the past 3 years, reports have again emerged recommending a funding reform (Box 1).

Box 1. Recent health care reform reports.

|

The consistent message from these reports is that health system reform needs to move to higher value care, overcoming fragmentation, removing perverse incentives that promote inefficiency, and fostering meaningful patient and citizen engagement. This aligns closely with the National Health Reform Agreement addendum 2020–2025, which identifies joint planning and funding at a local level as a strategic priority. 8

Moving to value‐based care in NSW

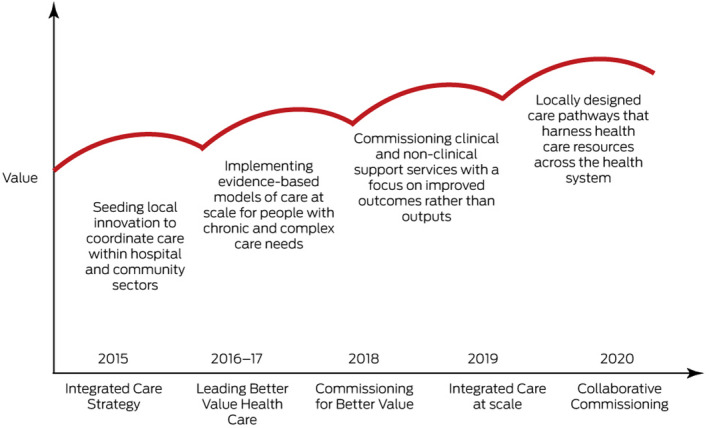

In the face of these pressures, NSW Health has a strategic goal to transition the health system from one driven by volume and activity‐based care towards a system driven by value, focusing on “quadruple aim” outcomes, encompassing improved health, improved health care, lower costs, and improved provider satisfaction. 9 , 10 NSW Health’s value‐based initiatives have matured over the past 5 years and include Integrated Care, which aims to coordinate care between the community and hospital sectors, was initially launched as demonstration and pilot projects, and is now being implemented at scale; 11 Leading Better Value Health Care, which implements evidence‐based care models at scale for people with chronic and complex care conditions; 9 Commissioning for Better Value, which shifts the focus of non‐clinical and clinical support projects from outputs to outcomes; and now Collaborative Commissioning (Box 2).

Box 2. Maturation of NSW Health initiatives to deliver integration and value.

What is Collaborative Commissioning?

Collaborative Commissioning is NSW Health’s latest flagship program to support value‐based health care. 12 It is a whole‐of‐system approach to incentivise local autonomy and accountability for delivering integrated, value‐based health care across the hospital and the community. It draws on key learnings from previous initiatives including:

a focus on improved patient experience and strong consumer participation in the design and implementation of new models of care;

local engagement with care providers in the design of new models of care that address specific problems faced by these providers;

sufficient flexibility in governance and funding arrangements while maintaining consistency in approach across the state;

better use of primary care and linked administrative data to inform model design and expected benefits; and

iterative evaluation cycles to identify early the need for modifications. 13

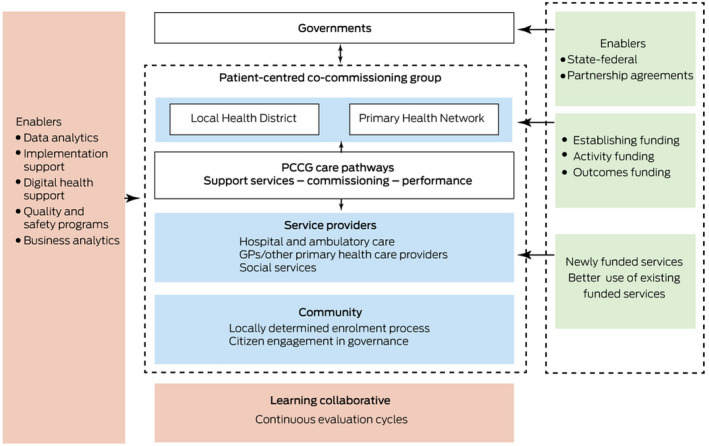

Local Hospital Districts and Primary Health Networks are required to form regional alliances known as patient‐centred co‐commissioning groups (PCCGs), which are jointly responsible for improving care for their communities (Box 3).

Box 3. Conceptual diagram of Collaborative Commissioning.

PCCG = patient‐centred co‐commissioning group. The blue section shows the stakeholders that are engaged as part of the PCCG. The orange boxes shows the enablers provided by NSW Health to support the initiative. The green boxes correspond with the governance and funding reforms to support Collaborative Commissioning.

The alliances are underpinned by six principles:

joint accountability by participating providers across the care spectrum;

strong patient and community engagement, embedding accountability to the communities being served;

commissioning of evidence‐based, locally designed care pathways to improve care and outcomes for defined populations;

funding reform, including flexible purchasing arrangements, realignment of existing resources, and outcome‐based payments;

supporting enablers from NSW Health, including data analytics, use of digital technologies, business analytics, implementation support, and quality and safety programs; and

fostering a learning health system to support continuous improvement and innovation as new knowledge comes available.

To nurture innovation, PCCGs will have wide discretion on how they engage service providers and communities to improve health outcomes. Their mandate is to establish integrated and coordinated care pathways between acute, primary and community care, underpinned by new financial arrangements. They are tasked with uniting diverse organisations and professional groups around a single, patient‐focused vision and commissioning services accordingly. PCCGs have governance, regional commissioning, and funding functions. These functions are expected to be fulfilled through maximising the use of local resources, identifying and avoiding waste, and fostering a shared sense of purpose among providers across the continuum of care, leading to shared accountability for agreed quality and safety outcomes based on local community needs.

Population focus

PCCGs identify priority cohorts for their region based on local needs analyses. Size, target health conditions, diversity, and equity are core considerations in determining the priority populations. Specific equity considerations focus on the “PROGRESS” domains of place of residence; race, ethnicity, culture, and language; occupation; gender and sex; religion; education; socio‐economic status; and social capital. 14 Each PCCG is encouraged to take a systems thinking approach and design care pathways that can be scaled to serve large populations over time. Particular subgroup populations with high health care needs may also be identified to receive higher intensity support, and population analytic tools are playing an important role in determining these priority population groups. This has already proven critical in the development of COVID‐19‐specific care pathways to support acute and ongoing health care needs in the community.

Funding model

Collaborative Commissioning has three funding reforms to support the shift from volume‐driven, purchaser‐provider transactions toward value‐based payments:

establishment funding to support the creation of appropriate governance structures, hiring of operational staff, and engagement with local providers and communities;

activity funding, which includes reorientation and optimisation of existing federal and state funding and new funding from NSW Health to commission the care pathways. This new funding is intended to be temporary, with a broad goal that PCCGs will achieve financial sustainability to implement their care pathways over time;

outcome‐based funding, where payment will be generated as a premium of the total cost of care (leveraged and new service elements) and is contingent on achieving agreed targets for improved patient outcomes. Outcome‐based funds are to be paid to the PCCG based on the payment criteria formalised during the contracting stage. Decisions regarding distribution of these funds among PCCG partners will also be established at the outset of the contract.

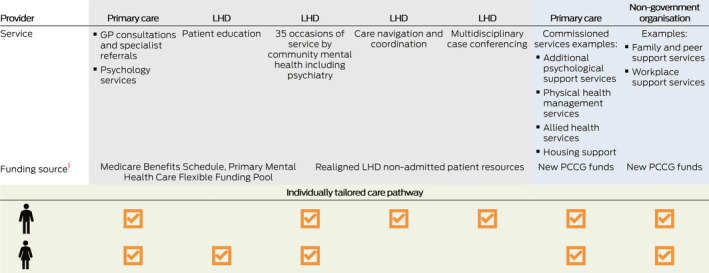

Box 4 provides a worked example of how a PCCG might develop a new pathway to address the problem of fragmented, siloed care for people needing mental health support. The PCCG would review existing services provided by Local Hospital Districts and primary care providers, identify inefficiencies, and optimise quality. In addition, it would commission new services based on local priorities. To support integration, both new and existing services would be overseen under the auspices of the PCCG. Individuals would develop tailored plans with their care providers involving a selection of some or all of these services.

Box 4. A sample mental health care pathway.

GP = general practitioner; LHD = Local Hospital District; PCCG = patient‐centred co‐commissioning group. The grey section corresponds to review of existing services; the blue section refers to the commissioning of new services based on local priorities; and the green section describes the development of individualised care pathways involving a mix of relevant services.

Enablers

A 2013 conceptual framework for integrated care highlights several principles associated with implementing health system integration initiatives. 15 These include addressing barriers at the micro‐ (clinical integration), meso‐ (professional and organisational integration) and macro‐ (system integration) levels. Technical and normative processes are required within and across these levels to support the implementation of reforms. To enhance these processes, NSW Health is providing support functions for PCCGs and facilitating sharing knowledge across PCCGs. Four key areas include: business analytics to support organisational sustainability; data analytics; meaningful use of digital health technologies; and developing quality and safety frameworks. The data analytics support leverages the NSW Health Lumos data asset — an ethics committee‐approved program that securely links encrypted data from general practice electronic medical records with other administrative health data in NSW, including hospital, emergency department, mortality and others. 16

To facilitate care pathway design and understand population needs, dynamic simulation modelling is being done to determine historical and projected trends in population demand and service supply, calculation of expenditure benchmarks, and return on investment analyses to understand tipping points for achieving sustainability under a range of scenarios. This data‐driven approach is being taken for all PCCGs to support accountability for outcomes from the outset. To support improvements in care quality, a performance monitoring framework is being developed, tailored to the needs of each PCCG, and includes health, process and experience measures. Careful attention is also being given to potential unintended consequences (eg, encouraging certain indicators at the expense of other aspects of care and diversion of care away from populations not included in the care pathways).

Assessing impact

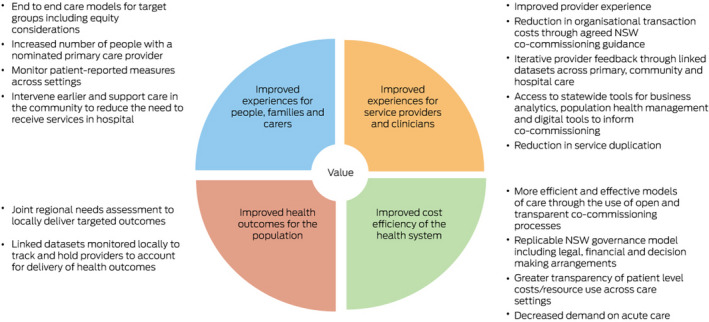

The desired outcomes of Collaborative Commissioning are aligned with the Quadruple Aim (Box 5).

Box 5. Assessing impact for Collaborative Commissioning.

Independent monitoring and evaluation activities are being done for each PCCG and will include developmental, interim, and summative evaluations to support continuous learning throughout implementation. In the development stage, a theory of change is being codesigned with each PCCG to accurately document inputs, activities, and outputs associated with their implementation and the hypothesised path to delivering impact. Following this, rapid cycle, interim evaluations using a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods will be done and fed back to support critical reflection and adaptation. For impact evaluation, quasi‐experimental designs involving comparison groups in regions not receiving the care pathway will be derived from the Lumos dataset to assess whether care pathways improve cost, quality, and experience of care. The impact evaluation will be accompanied by detailed process evaluations to understand implementation barriers and enablers. Findings will be synthesised across all PCCGs to facilitate broader system‐wide learnings and inform future iterations of the policy.

Conclusion

Collaborative Commissioning is a so‐called middle out approach to reform where meso‐tier actors are being supported to become the incubators of health system reform. 17 PCCGs are perhaps best considered as social enterprises, taking a start‐up mentality to their formulation and driven by ground‐up innovation. Consistent with international evidence that successful health reform initiatives require long term payer–provider commitments, NSW Health is affording PCCGs some degree of financial protection to enable them to trial new models and continuously iterate as new information comes to light. 18 Strong leadership and organisational structures are essential in driving success. Investment in both health system hardware (eg, infrastructure, financing, human resources, information systems) and software (eg, network and relationship building, shared ideas, values and norms) is a key enabler. 19 Over time, PCCGs have the potential to be expanded to include payers and providers from public, private, and non‐government sectors to facilitate whole‐of‐system integration. Such models could create opportunities for more effective integration of health, social, aged care, and disability service sectors and create appropriate incentives for providers to work collaboratively across these sectors. Further, the core elements of PCCGs are common to Primary Health Networks and Local Hospital Districts in other states and, therefore, the lessons generated are likely to be relevant to state–federal reform initiatives in other states and territories.

With rising expenditure growth, widening inequalities, and acute pressures related to the COVID‐19 pandemic, our health system is in need of redesign to ensure value in the system. Transformative health care delivery models that go beyond minor, incremental changes are required. Collaborative Commissioning represents the next stage of NSW Health’s strategic commitment to move the state further toward a more sustainable, equitable, and value‐driven health system.

Competing interests

No relevant disclosures.

Provenance

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The research associated with Collaborative Commissioning is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Partnership Projects grant (1198416). The funding source had no role in the planning, writing or publication of the work. Special thanks to Anne‐Marie Feyer and Louise Fisher for their input and critical feedback on the manuscript.

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Health expenditure Australia 2017–18 [Cat. No. HWE 77]. Canberra: AIHW. 2019. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/91e1dc31‐b09a‐41a2‐bf9f‐8deb2a3d7485/aihw‐hwe‐77‐25092019.pdf.aspx (viewed May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission . A healthier future for all Australians; final report of the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2009. http://www.cotasa.org.au/cms_resources/documents/news/nhhrc_report.pdf (viewed May 2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Primary Health Care Advisory Group . Better outcomes for people with chronic and complex health conditions. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2015. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/76B2BDC12AE54540CA257F72001102B9/$File/Primary‐Health‐Care‐Advisory‐Group_Final‐Report.pdf (viewed May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Productivity Commission . Shifting the dial: 5 year productivity review [Inquiry Report No. 84]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2017. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity‐review/report/productivity‐review.pdf (viewed May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Australian Healthcare and Hospitals Association . Healthy people, healthy systems — strategies for outcomes‐focused and value‐based healthcare: a blueprint for a post‐2020 National Health Agreement. Canberra: AHHA, 2017. https://ahha.asn.au/sites/default/files/docs/policy‐issue/ahha_blueprint_2017_0.pdf (viewed May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Swerissen H, Duckett S. Mapping primary care in Australia. Melbourne: Grattan Institute, 2018. https://grattan.edu.au/wp‐content/uploads/2018/07/906‐Mapping‐primary‐care.pdf (viewed May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 7. George Institute for Global Health, Consumers Health Forum of Australia, University of Queensland MRI Centre for Health System Reform and Integration. Snakes and Ladders: the journey to primary care integration; 2018. https://www.georgeinstitute.org/sites/default/files/phc_report_0.pdf (viewed May 2021).

- 8. Council on Federal Financial Relations . Addendum to the National Health Reform Agreement: revised public hospital funding and health reform arrangements takes effect. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. www.federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/content/national_health_reform.aspx (viewed May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koff E, Lyons N. Implementing value‐based health care at scale: the NSW experience. Med J Aust 2020; 212: 104–106. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/212/3/implementing‐value‐based‐health‐care‐scale‐nsw‐experience [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med 2014; 12: 573–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. NSW Health . NSW Health Strategic Framework for Integrating Care; 2018. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/integratedcare/Pages/strategic‐framework.aspx (viewed May 2021).

- 12. NSW Health . Collaborative Commissioning; 2020. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Value/Pages/collaborative‐commissioning.aspx (viewed May 2021).

- 13. Billot L, Corcoran K, McDonald A, et al. Impact evaluation of a system‐wide chronic disease management program on health service utilisation: a propensity‐matched cohort study. PLoS Med 2016; 13: e1002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V, et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67: 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, et al. Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care 2013; 13: e010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. NSW Health . Lumos; 2020. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/lumos/Pages/default.aspx (viewed May 2021).

- 17. Belasen A, Luber EB. Innovation implementation: leading from the middle out. In: Pfeffermann N, Gould J; editors. Strategy and communication for innovation: integrative perspectives on innovation in the digital economy. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017; pp 229–243. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peiris D, News M, Nallaiah K. Evidence Check: Accountable care organisations: an evidence check rapid review brokered by the Sax Institute for the NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation, 2018. https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/Accountable‐care‐organisations.pdf (viewed May 2020).

- 19. Sheikh K, Gilson L, Agyepong IA, et al. Building the field of health policy and systems research: framing the questions. PLoS Med 2011; 8: e1001073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]