ABSTRACT

Background

Mutations in the GBA gene, which encodes the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase (GCase), are risk factors for Parkinson's disease (PD).

Objective

To explore the association between GCase activity, PD phenotype, and probability for prodromal PD among carriers of mutations in the GBA and LRRK2 genes.

Methods

Participants were genotyped for the G2019S‐LRRK2 and nine GBA mutations common in Ashkenazi Jews. Performance‐based measures enabling the calculation of the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) prodromal probability score were collected.

Results

One hundred and seventy PD patients (102 GBA‐PD, 38 LRRK2‐PD, and 30 idiopathic PD) and 221 non‐manifesting carriers (NMC) (129 GBA‐NMC, 45 LRRK2‐NMC, 15 GBA‐LRRK2‐NMC, and 32 healthy controls) participated in this study. GCase activity was lower among GBA‐PD (3.15 ± 0.85 μmol/L/h), GBA‐NMC (3.23 ± 0.91 μmol/L/h), and GBA‐LRRK2‐NMC (3.20 ± 0.93 μmol/L/h) compared to the other groups of participants, with no correlation to clinical phenotype.

Conclusions

Low GCase activity does not explain the clinical phenotype or risk for prodromal PD in this cohort. © 2021 The Authors. Movement Disorders published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, LRRK2 , GBA , GCase

Mutations in the GBA gene, which encodes the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase (GCase), are common risk factors for Parkinson's disease (PD). Lower GCase activity was found not only in GBA mutation carriers, but also among idiopathic PD patients,1, 2 with reduced GCase activity linked to increased alpha‐synuclein aggregation. 3

GBA mutations affect the phenotype of PD, with a younger age of disease onset and an increased frequency of earlier cognitive and psychiatric disorders compared to idiopathic PD (iPD).4, 5 Mutations are divided into mild (mGBA), severe (sGBA), and variant (vGBA) based on their involvement in Gaucher's disease. 6 sGBA‐PD is associated with worse motor, cognitive, olfactory, and psychiatric symptoms compared to mGBA‐PD7, 8 and a more rapid decline in these parameters. 9 Moreover, the severity of PD phenotype was found to be related to the burden of GBA mutations, with homozygotes or compound heterozygotes displaying an earlier age of motor symptoms onset and worse motor, cognitive, psychiatric, and autonomic symptoms than heterozygotes GBA‐PD and iPD. 10 vGBA mutations are associated with PD but not with Gaucher's disease, 11 confer a high risk for cognitive impairment, 12 but affect PD motor deterioration in a less severe manner. 13 Penetrance estimations for GBA mutations are relatively low, 14 with additional environmental and genetic modifiers including GCase activity 15 suspected to be associated with reduced penetrance.

Despite this proposed genotype–phenotype association, the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism for GBA‐PD remains unknown. While some studies show that the GBA‐regulated sphingolipid pathway has an important role in PD pathophysiology, 3 the specific role of GCase activity requires further clarification.

The G2019S mutation in LRRK2 is common among Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) patients with PD. Conflicting reports on the role of LRRK2 and GCase activity have been published.16, 17

We aimed to assess whether GCase activity is related to PD phenotype and risk for developing disease among PD patients and non‐manifesting family members of PD patients, carriers of mutations in the GBA and LRRK2 genes.

Methods

Participants were recruited from the BEAT‐PD (TLV‐0204‐16), a Biogen‐Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (TASMC) collaborative natural history study. Patients were recruited if they were AJ, diagnosed based on the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) clinical diagnostic criteria for PD. 18 Non‐manifesting participants were recruited if they were first‐degree relatives of a genetic PD patient, older than 40 years of age and were excluded if they were using dopamine‐depleting medications. Additional exclusion criteria for all participants included any significant neurological or psychiatric disorders, malignancy or positive HIV, HBV, or HCV tests. The ethical committee of TASMC, according to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration, approved the study. All participants provided informed written consent prior to participation.

Procedure

Participants were genotyped for the G2019S‐LRRK2 mutation and the seven founder GBA mutations as previously described.4, 6 In addition, all participants were also genotyped for E326K and T369M considered vGBA (supplementary material). Participants with no detectable mutations were considered idiopathic PD (iPD) or healthy non‐manifesting non‐carriers (NMNC).

Performance‐based measures were collected enabling the calculation of the probability for prodromal PD (likelihood ratio score) for non‐manifesting participants, based on the updated MDS Task Force guidelines 19 excluding DaT assessments and substantia nigra hyperechogenicity. Levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was calculated for all patients. 20

White blood count (WBC), absolute lymphocyte, monocyte, and neutrophil levels were collected. GCase analysis is described in the supplementary material.

Statistical Analysis

Prior to analysis, all variables were examined for normality (Shapiro–Wilk W test). Outliers were excluded when appropriate if values were two standard deviations (SDs) from the mean. Descriptive statistics were computed for all measures. Differences in sex within each cohort were evaluated using chi‐square (χ2) tests. Multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate differences between groups based on disease and genetic status: The analysis was adjusted for age and sex in both cohorts and for disease duration among patients. For the GCase assessments, months in freezer were also entered as a covariate. Bivariate correlations were performed between GCase activity, laboratory, and behavioral measures. Significance was determined at P < 0.05 for descriptive measures and corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni adjustment. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.

Results

A total of 170 PD patients (102 GBA‐PD [73 mGBA, 16 sGBA, 13 vGBA], 38 LRRK2‐PD, and 30 iPD) and 221 non‐manifesting subjects (129 GBA non‐manifesting carriers [NMC] [80 mGBA, 38 sGBA, and11 vGBA], 45 LRRK2‐NMC, 15 GBA‐LRRK2‐NMC, and 32 NMNC( participated in this study (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | iPD | LRRK2‐PD | GBA‐PD | P value | Control | LRRK2‐NMC | GBA‐NMC | LRRK2‐GBA‐NMC | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 30 | 38 | 102 | 32 | 45 | 129 | 15 | ||

| Mutation type |

N370S‐67 R496H‐6 84GG‐7 370Rec‐4 V394L‐2 IVS2+1G‐>A‐2 L4449‐1 E326K‐7 T369M‐6 |

N370S‐64 R496H‐16 84GG‐14 370Rec‐10 V394L‐5 IVS2+1G‐>A‐4 L444P‐5 E326K‐7 T396M‐4 |

|||||||

| GCase (μmol/L/h) | 4.77 ± 1.23 | 4.94 ± 1.47 | 3.15 ± 0.85 | 0.001 # | 4.85 ± 1.43 | 4.80 ± 1.32 | 3.23 ± 0.91 | 3.20 ± 0.93 | 0.001 ^ |

| Duration of storage (mo) | 35.86 ± 2.98 | 25.51 ± 9.54 | 23.88 ± 8.68 | 0.001 $ | 32.29 ± 3.69 | 29.15 ± 5.46 | 23.62 ± 6.62 | 21.80 ± 8.18 | 0.001% |

| Age (y) | 65.76 ± 10.77 | 65.43 ± 9.25 | 64.91 ± 9.87 | 0.906 | 55.06 ± 10.12 | 52.49 ± 9.54 | 53.43 ± 10.71 | 50.60 ± 10.12 | 0.531 |

| Gender m/f | 20/10 | 23/15 | 65/37 | 0.907 | 14/18 | 24/21 | 41/88 | 4/11 | 0.060 |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | 62.24 ± 11.07 | 62.37 ± 9.30 | 61.93 ± 10.15 | 0.970 | |||||

| Disease duration (y) | 3.52 ± 1.90 | 3.39 ± 2.54 | 3.11 ± 2.59 | 0.686 | |||||

| LEDD (mg/d) | 342.72 ± 285.33 | 377.35 ± 397.75 | 374.37 ± 375.06 | 0.466 | |||||

| MDS‐UPDRS Part III | 24.38 ± 9.50 | 19.00 ± 9.53 | 22.21 ± 12.41 | 0.368 | |||||

| MDS‐UPDRS total | 41.76 ± 16.34 | 31.81 ± 17.12 | 38.39 ± 20.37 | 0.108 | 6.10 ± 4.51 | 5.51 ± 4.34 | 5.02 ± 4.47 | 4.87 ± 4.08 | 0.699 |

| Education (y) | 16.69 ± 3.03 | 16.84 ± 2.65 | 16.08 ± 2.97 | 0.311 | 17.55 ± 2.46 | 16.55 ± 3.18 | 17.40 ± 2.62 | 18.40 ± 2.53 | 0.095 |

| MoCA | 23.90 ± 3.70 | 25.08 ± 4.06 | 23.29 ± 3.98 | 0.120 | 27.13 ± 3.15 | 27.22 ± 2.56 | 25.86 ± 3.03 | 27.27 ± 2.46 | 0.006 |

| UPSIT | 15.65 ± 10.57 | 20.33 ± 9.35 | 15.15 ± 9.33 | 0.006 | 31.12 ± 7.05 | 32.17 ± 4.51 | 29.85 ± 6.31 | 30.64 ± 6.14 | 0.128 |

| Platelets (10−3/μL) | 213.24 ± 54.78 | 213.11 ± 57.86 | 209.68 ± 48.66 | 0.907 | 228.48 ± 57.23 | 231.09 ± 57.13 | 234.20 ± 60.22 | 239.39 ± 71.11 | 0.958 |

| WBC (10−3/μL) | 6.92 ± 1.53 | 7.28 ± 2.06 | 6.93 ± 1.61 | 0.583 | 7.47 ± 1.73 | 6.70 ± 1.56 | 7.01 ± 2.01 | 6.21 ± 1.03 | 0.144 |

| GCase/WBC | 0.69 ± 0.14 | 0.69 ± 0.19 | 0.48 ± 0.15 | 0.001 # | 0.65 ± 0.14 | 0.73 ± 0.21 | 0.47 ± 0.13 | 0.51 ± 0.11 | 0.001 ^, * |

| GCase/monocytes | 9.71 ± 2.44 | 9.63 ± 3.11 | 6.74 ± 2.76 | 0.001 # | 10.28 ± 3.89 | 10.91 ± 4.18 | 7.18 ± 2.72 | 7.28 ± 2.16 | 0.001 # |

| Probability | 8.68 ± 24.68 | 17.09 ± 30.14 | 27.10 ± 31.43 | 18.87 ± 25.69 | 0.012 |

Abbreviations: iPD, idiopathic Parkinson's disease; NMC, non‐manifesting carriers; GCase, beta glucocerebrosidase; h, hour; mo, month; y, year; m, male; f, female; LEDD, levodopa equivalent daily dose; d, day; MDS‐UPDRS, Movement Disorder Society‐Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; UPSIT, University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test; WBC, white blood count.

Results were adjusted for multiplicity using Bonferroni correction, the original P value is displayed. Bold type indicates significance after correction for multiplicity. #Difference between GBA‐PD and iPD, LRRK2‐PD. $Differences between iPD and LRRK2‐PD, GBA‐PD. ^Difference between controls, LRRK2‐NMC and GBA‐NMC, LRRK2‐GBA‐NMC. %Difference between controls and LRRK2‐NMC, GBA‐NMC, LRRK2‐GBA‐NMC. *Difference between controls and LRRK2‐NMC.

A trend for higher University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) scores among LRRK2‐PD compared to GBA‐PD and iPD (20.33 ± 9.35 [95% CI 17.54–Z23.51], 15.15 ± 9.33 [95% CI 13.19–17.05], and 15.65 ± 10.57 [95% CI 11.48–16.68], P = 0.006, uncorrected) was detected. No significant differences between mGBA‐PD and sGBA‐PD were identified in any measure assessed herein.

GBA‐NMC trended for higher probability scores for prodromal PD compared with the other groups of participants (27.10 ± 31.43 [95% CI 21.90–32.30], 8.68 ± 24.68 [95% CI 0.93–19.28], 17.09 ± 30.14 [95% CI 8.28–25.89], and 18.87 ± 25.69 [95% CI 3.61–34.11], P = 0.012, uncorrected). No difference in the probability score for prodromal PD was detected between the different GBA‐NMC groups (vGBA‐NMC, mGBA‐NMC, and sGBA‐NMC) (19.72 ± 9.51 [95% CI 0.89–38.55], 28.95 ± 3.52 [95% CI 21.96–35.93], and 25.34 ± 5.11 [95% CI 15.21–35.47]). GBA‐NMC demonstrated a trend for lower Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores compared with NMNC, LRRK2‐NMC and LRRK2‐GBA‐NMC (25.86 ± 3.03 (95% CI 25.37–26.32), 27.13 ± 3.15 (95% CI 26.39–28.37), 27.22 ± 2.56 (95% CI 26.38–28.011) and 27.27 ± 2.46 (95% CI 25.53–28.32) P = 0.006, uncorrected). However, no difference in MoCA scores between the different groups of GBA‐NMC was detected (vGBA‐NMC, mGBA‐NMC, and sGBA‐NMC) (26.12 ± 0.84 [95% CI 24.45–27.80], 25.55 ± 0.31 [95% CI 24.93–26.17], and 26.41 ± 0.45 [95% CI 25.52–27.31]).

GCase activity did not differ between men and women in any group of participants. Duration of sample storage in months differed among the total cohort (P < 0.001), with iPD and NMNC having the longest duration of storage. Storage time was positively correlated with GCase activity among the total cohort (r = 0.150, P = 0.03) but not among GBA‐PD or GBA‐NMC.

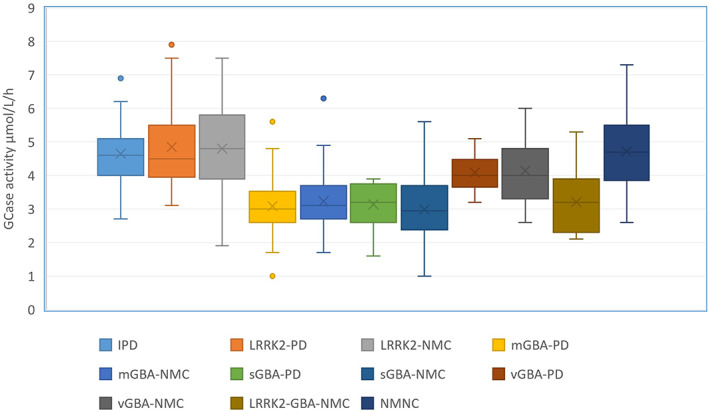

GBA‐PD had significantly lower GCase activity compared to iPD and LRRK2‐PD (3.15 ± 0.85 μmol/L/h [95% CI 2.94–3.37], 4.77 ± 1.23 μmol/L/h [95% CI 4.42–5.31], and 4.94 ± 1.47 μmol/L/h [95% CI 4.65–5.35], P < 0.001). GCase activity did not differ between mGBA‐PD and sGBA‐PD (3.08 ± 0.77 μmol/L/h [95% CI 2.90–3.26], 3.13 ± 0.65 μmol/L/h [95% CI 2.77–3.49], P = 0.797) (Fig. 1); however, vGBA‐PD had higher GCase activity compared with the two other groups (4.09 ± 0.61 μmol/L/h [95% CI 3.64–4.49]). The same results were obtained when using the GCase/WBC ratio hence we present the results of GCase activity not corrected for WBC. Age and GCase activity were not correlated and no association between GCase activity, MoCA, or the Movement Disorder Society‐Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS‐UPDRS) score was detected in the total PD cohort, or among any genetic PD subgroups.

FIG. 1.

Glucocerebrosidase (GCase) activity among study subgroups. The line in each box indicates the median, the 95% confidence intervals are displayed as the whiskers, and mean is depicted by the X. P < 0.001. IPD, idiopathic Parkinson's disease; mGBA, mild GBA; sGBA, severe GBA; vGBA, variant GBA; NMC, non‐manifesting carriers; PD, Parkinson's disease. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

GBA‐NMC (3.23 ± 0.91 μmol/L/h [95% CI 3.04–3.42] and GBA‐LRRK2‐NMC 3.20 ± 0.93 μmol/L/h [95% CI 2.65–3.76]) had significantly lower GCase activity compared with LRRK2‐NMC (4.80 ± 1.32 μmol/L/h [95% CI 4.41–5.27] and NMNC 4.85 ± 1.43 μmol/L/h [95% CI 4.48–5.17], P = 0.001). LRRK2‐NMC had higher GCase/WBC ratio compared with the three other groups of NMC participants (NMNC, GBA‐NMC, and LRRK2‐GBA‐NMC) (0.73 ± 0.21 [95% CI 0.69–0.78], 0.65 ± 0.28 [95% CI 0.59–0.71], 0.47 ± 0.14 [95% CI 0.45–0.50], and 0.51 ± 0.42 [95% CI 0.43–0.59], P < 0.001). A stepwise increase in GCase activity was detected between sGBA‐NMC, mGBA‐NMC, vGBA‐NMC, and NMNC (2.98 ± 0.17 μmol/L/h [95% CI 2.64–3.31], 3.23 ± 0.11 μmol/L/h [95% CI 3.00–3.46], 4.14 ± 0.31 μmol/L/h [95% CI 3.51–4.77], and μmol/L/h 4.85 ± 1.43 [95% CI 4.07–5.36], P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). No correlations between GCase activity and age, or the MDS probability score for prodromal PD, were detected among any group of non‐manifesting participants.

No difference in GCase activity between GBA‐PD and GBA‐NMC (3.15 ± 0.85 μmol/L/h [95% CI 2.94–3.37], 3.20 ± 0.93 μmol/L/h [95% CI 2.65–3.76], P = 0.511), mGBA‐PD and mGBA‐NMC (3.08 ± 0.77 μmol/L/h [95% CI 2.90–3.26] and 3.23 ± 0.11 μmol/L/h [95% CI 3.00–3.46], P = 0.231), or sGBA‐PD and sGBA‐NMC (3.13 ± 0.65 μmol/L/h [95% CI 2.77–3.49] and 2.98 ± 0.17 μmol/L/h [CI 95%2.64–3.31], P = 0.239) were detected.

Discussion

While GCase activity among GBA‐PD and GBA‐NMC was low, activity among iPD, LRRK2‐PD, and LRRK2‐NMC were within normal range. In addition, no significant difference in GCase activity was detected between mGBA‐PD and sGBA‐PD, and no genotype–phenotype correlations were detected between GCase activity and disease severity measures. Among NMC, a stepwise increase in GCase activity was detected between sGBA‐NMC, mGBA‐NMC, vGBA‐NMC, and NMNC with no correlation between GCase activity and the MDS prodromal probability scores.

Pathological studies have detected reduced GCase activity in GBA‐PD and iPD 1 with the reduction in GCase activity inversely related to the accumulation of α‐synuclein. 2 A bidirectional loop between GCase activity and α‐synuclein has been postulated in which reduced lysosomal GCase activity causes damage to macroautophagy and chaperone‐mediated autophagy, leading to the accumulation of intracellular α‐synuclein21, 22 and release of α‐synuclein from neurons, potentially enabling transmission to adjacent neurons. Furthermore, excessive α‐synuclein levels cause a decrease in wild‐type GCase trafficking to the lysosome. 23

An association between lower GCase activity and shorter disease duration, suggesting a more rapid progression of PD symptoms, was previously reported. 17 However, subsequent longitudinal studies failed to replicate these results, demonstrating a correlation between GCase activity and GBA genotype, but not between GCase activity and PD phenotype.24, 25

While we detected a stepwise reduction in GCase activity between sGBA‐NMC, mGBA‐NMC, and vGBA‐NMC, we did not find an association with risk for prodromal PD, as was previously reported. 25 GCase activity was lower among vGBA‐NMC compared to healthy NMNC as previously reported 26 but still within normal limits. In addition, no difference in GCase activity between mGBA‐PD and mGBA‐NMC or between sGBA‐PD and sGBA‐NMC was found, indicating that GCase activity cannot be considered a biomarker for PD risk or phenotype.

GCase activity among LRRK2‐PD and LRRK2‐NMC was within normal limits, contrary to previous reports on patients with PD.16, 17 Furthermore, GCase/WBC levels were higher among LRRK2‐NMC compared with the rest of the non‐manifesting participants, as was previously reported. 27

Dual mutation carriers (LRRK2‐GBA‐PD) tend to exhibit a milder phenotype compared with GBA‐PD.28, 29 GBA‐LRRK2‐NMC had significantly lower GCase activity as compared with LRRK2‐NMC, suggesting that the postulated LRRK2 ‘dominant effect’ is not explained by an effect on GCase activity.

Several limitations need to be addressed: the cross‐sectional design of this study, the relatively small number of severe GBA‐PD and sGBA‐NMC participants, and the small group of vGBA‐PD. The GBA gene was not sequenced but rather analyzed for specific AJ‐related mutations, which represent more than 96% of the known mutations among AJ. 30 For GCase activity measurement, we used dried blood spots, but peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or cerebrospinal fluid might have been better suited. 31 The correlations between GCase activity and PD symptoms were performed when all patients were “ON” medications, but no data regarding “OFF” state was collected.

GCase activity does not seem to hold promise as a biomarker for disease risk or severity in PD but is rather an endophenotype of mutations in the GBA gene. An interaction between GCase activity and other mutations or environmental factors might still have relevance to PD pathogenesis.

Author Roles

N.O.: organization, execution, draft of manuscript.

N.G.: review and critique.

T.G.: review and critique.

A.B.S.: execution, review and critique.

M.G.W.: organization, review and critique.

T.G.: organization, review and critique.

O.G.: execution, review and critique.

M.K.: organization, review and critique.

J.M.C.: review and critique.

O.S.M.: review and critique.

K.B.F.: review and critique.

J.C.S.: review and critique.

A.O.U.: review and critique.

A.M.: conception, review and critique.

A.T.: conception, statistical analysis, draft of manuscript.

Financial Disclosures

N.O.: Nothing to report.

N.G.: Serves on the Editorial Board of the Journal of Parkinson's Disease. Serves as consultant to Sionara, Accelmed, Teva, NeuroDerm, Intec Pharma, Pharma2B, Denali, and Abbvie. Receives royalties from Lysosomal Therapeutics (LTI) and payment for lectures from Teva, UCB, Abbvie, Sanofi‐Genzyme, Bial, and the Movement Disorder Society. Received research support from The Michael J. Fox Foundation, the National Parkinson Foundation, the European Union 7th Framework Program, the Israel Science Foundation, Teva NNE program, Biogen, LTI, and Pfizer.

T.G.: Advisory board membership with honoraria from Abbvie Israel, Neuroderm Ltd., and Allergan; research support from Phonetica Ltd., Israeli Innovation Authority, Sagol School of Neuroscience, and Parkinson's Foundation. Receiving travel support from Abbvie, Allergan, Medisson, and Medtronic.

A.B.S.: Nothing to report.

M.G.W.: Nothing to report.

T.G.: Nothing to report.

O.G.: Nothing to report.

M.K.: Payment for lectures from Abbvie and Teva.

J.M.C.: A former employee and shareholder in Biogen, Inc.

O.S.M.: A current employee and shareholder in Biogen Inc.

K.B.F.: A current employee and shareholder in Biogen Inc.

J.C.S.: A current employee and shareholder in Biogen Inc.

A.O.U.: Research support from The Michael J. Fox Foundation, Chaya Charitable Fund, and Biogen Inc. and payment for lectures from Sanofi Genzyme and Pfizer.

A.M.: Serving as an advisor to Neuroderm.

A.T.: Receiving honoraria from Abbvie Israel.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting Information

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: O.S.M., K.B.F., and J.C.S. are employees and shareholders of Biogen Inc. None of the other authors reports any conflict of interest.

Funding agencies: This work was funded by Biogen Inc., The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, and The Silverstein Foundation for Parkinson's with GBA.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Gegg ME, Burke D, Heales SJ, et al. Glucocerebrosidase deficiency in substantia nigra of parkinson disease brains. Ann Neurol 2012;72(3):455–463. 10.1002/ana.23614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murphy KE, Gysbers AM, Abbott SK, et al. Reduced glucocerebrosidase is associated with increased alpha‐synuclein in sporadic Parkinson's disease. Brain 2014;137(pt 3):834–848. 10.1093/brain/awt367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mazzulli JR, Xu YH, Sun Y, et al. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and alpha‐synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell 2011;146(1):37–52. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gan‐Or Z, Giladi N, Rozovski U, et al. Genotype‐phenotype correlations between GBA mutations and Parkinson disease risk and onset. Neurology 2008;70(24):2277–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2009;361(17):1651–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goldstein O, Gana‐Weisz M, Cohen‐Avinoam D, et al. Revisiting the non‐Gaucher‐GBA‐E326K carrier state: is it sufficient to increase Parkinson's disease risk? Mol Genet Metab 2019;128(4):470–475. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.10.001. Epub 2019 Oct 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thaler A, Bregman N, Gurevich T, et al. Parkinson's disease phenotype is influenced by the severity of the mutations in the GBA gene. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018;55:45–49. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.05.009. Epub 2018 May 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cilia R, Tunesi S, Marotta G, et al. Survival and dementia in GBA‐associated Parkinson's disease: the mutation matters. Ann Neurol 2016;80(5):662–673. 10.1002/ana.24777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu G, Boot B, Locascio JJ, et al. Specifically neuropathic Gaucher's mutations accelerate cognitive decline in Parkinson's. Ann Neurol 2016;80(5):674–685. 10.1002/ana.24781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thaler A, Gurevich T, Bar Shira A, et al. A "dose" effect of mutations in the GBA gene on Parkinson's disease phenotype. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;36:47–51. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greuel A, Trezzi JP, Glaab E, et al. GBA variants in Parkinson's disease: clinical, metabolomic, and multimodal neuroimaging phenotypes. Mov Disord 2020;35(12):2201–2210. 10.1002/mds.28225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Straniero L, Asselta R, Bonvegna S, et al. The SPID‐GBA study: sex distribution, penetrance, incidence, and dementia in GBA‐PD. Neurol Genet 2020;6(6):e523. 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maple‐Grodem J, Dalen I, Tysnes OB, et al. Association of GBA genotype with motor and functional decline in patients with newly diagnosed Parkinson disease. Neurology 2021;96(7):e1036–e1044. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anheim M, Elbaz A, Lesage S, et al. Penetrance of Parkinson disease in glucocerebrosidase gene mutation carriers. Neurology 2012;78(6):417–420. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318245f476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schierding W, Farrow S, Fadason T, et al. Common variants coregulate expression of GBA and modifier genes to delay Parkinson's disease onset. Mov Disord 2020;35(8):1346–1356. 10.1002/mds.28144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ysselstein D, Nguyen M, Young TJ, et al. LRRK2 kinase activity regulates lysosomal glucocerebrosidase in neurons derived from Parkinson's disease patients. Nat Commun 2019;10(1):5570. 10.1038/s41467-019-13413-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alcalay RN, Levy OA, Waters CC, et al. Glucocerebrosidase activity in Parkinson's disease with and without GBA mutations. Brain 2015;138(pt 9):2648–2658. 10.1093/brain/awv179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2015;30(12):1591–1601. 10.1002/mds.26424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heinzel S, Berg D, Gasser T, et al. Update of the MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2019;34(10):1464–1470. 10.1002/mds.27802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, et al. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2010;25(15):2649–2653. 10.1002/mds.23429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hruska KS, LaMarca ME, Scott CR, et al. Gaucher disease: mutation and polymorphism spectrum in the glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA). Hum Mutat 2008;29(5):567–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nilsson O, Svennerholm L. Accumulation of glucosylceramide and glucosylsphingosine (psychosine) in cerebrum and cerebellum in infantile and juvenile Gaucher disease. J Neurochem 1982;39(3):709–718. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb07950.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nilsson O, Grabowski GA, Ludman MD, et al. Glycosphingolipid studies of visceral tissues and brain from type 1 Gaucher disease variants. Clin Genet 1985;27(5):443–450. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00229.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alcalay RN, Wolf P, Chiang MSR, et al. Longitudinal measurements of glucocerebrosidase activity in Parkinson's patients. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2020;7(10):1816–1830. 10.1002/acn3.51164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Avenali M, Toffoli M, Mullin S, et al. Evolution of prodromal parkinsonian features in a cohort of GBA mutation‐positive individuals: a 6‐year longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2019;90(10):1091–1097. 10.1136/jnnp-2019-320394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pchelina S, Baydakova G, Nikolaev M, et al. Blood lysosphingolipids accumulation in patients with Parkinson's disease with glucocerebrosidase 1 mutations. Mov Disord 2018;33(8):1325–1330. 10.1002/mds.27393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alcalay RN, Wolf P, Levy OA, et al. Alpha galactosidase a activity in Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis 2018;112:85–90. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Omer N, Giladi N, Gurevich T, et al. A possible modifying effect of the G2019S mutation in the LRRK2 Gene on GBA Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2020;35(7):1249–1253. 10.1002/mds.28066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ortega RA, Wang C, Raymond D, et al. Association of dual LRRK2 G2019S and GBA variations with Parkinson disease progression. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(4):e215845. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beutler E, Nguyen NJ, Henneberger MW, et al. Gaucher disease: gene frequencies in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Am J Hum Genet 1993;52(1):85–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Avenali M, Cerri S, Ongari G, et al. Profiling the biochemical signature of GBA‐related Parkinson's disease in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Mov Disord 2021;36(5):1267–1272. 10.1002/mds.28496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.