Abstract

Aims

We profile the lack of specific regulation for direct‐to‐patient postal supply (DTP) of clinical trial medications (investigational medicinal products, IMPs) calling for increased efficiency of patient‐centred multi‐country remote clinical trials.

Methods

Questionnaires emailed to 28 European Economic Area (EEA) Medical Product Licensing Authorities (MPLAs) and Swissmedic MPLA were analysed in 2019/2020. The questionnaire asked whether DTP of IMPs was legal, followed by comparative legal analysis profiling relevant national civil and criminal liability provisions in 30 European jurisdictions (including The Netherlands), finally summarising accessible COVID‐19‐related guidance in searches of 30 official MPLA websites in January 2021.

Results

Twenty MPLAs responded. Twelve consented to response publication in 2021. DTP was not widely authorised, though different phrases were used to explain this. Our legal review of national laws in 29 EEA jurisdictions and Switzerland did not identify any specific sanctions for DTP of IMPs; however, we identified potential national civil and criminal liability provisions. Switzerland provides legal clarity where DTP of IMPs is conditionally legal. MPLA webpage searches for COVID‐19 guidance noted conditional acceptance by 19 MPLAs.

Conclusions

Specific national legislation authorising DTP of IMPs, defining IMP categories, and conditions permitting the postage and delivery by courier in an EEA‐wide clinical trial, would support innovative patient‐centred research for multi‐country remote clinical trials. Despite it appearing more acceptable to do this between EU Member States, provided each EU MPLA and ethics board authorises it, temporary Covid‐19 restrictions in national Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidance discourages innovative research into the safety and effectiveness of clinical trial medications.

Keywords: adherence, clinical trials, medication safety, patient safety, pharmacy

1. What is already known about this subject

There is a lack of awareness of potential criminal and civil law implications of sending investigational medicinal product by post directly to a patient's home in Europe.

The COVID‐19 pandemic has accelerated the introduction of patient‐centric approaches and may have exacerbated a lack of harmonisation in clinical trial regulation.

What this study adds

An analysis of selected nationally enacted EU‐wide criminal and administrative offences resulting from Article 95 of Regulation (EU) 536/2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use.

Identification of non‐functioning, outdated, non‐harmonised clinical trial and pharmaceutical regulations at EU and national level (particularly highlighted by Covid‐19 implications for clinical trials) with major implications for decentralised trials.

Low‐risk multi‐centre clinical trials in clearly defined categories and conditions (e.g. listed IMPs), should be legally authorised, permitting the direct supply of IMPs to patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

Direct‐to‐patient supply (DTP) of clinical trial medications, known as Investigational Medicinal Products (IMPs), is used increasingly, along with other remote trial methods, to facilitate efficient patient‐centred clinical trials. In this article, we use the term DTP of IMPs to refer to direct postal or courier delivery of IMP(s) to a trial patient (or participant) at their home address. This approach is accepted and preferred by patients. 1 DTP can reduce the number and duration of required study visits, minimise the inconvenience of trial participation, and facilitate a continued trial activity during a pandemic. DTP has additional operational benefits, such as reducing local IMP storage requirements and staffing costs. 2 , 3 However, a lack of harmonised regulation of DTP of IMPs within and across national borders has posed challenges that threaten large‐scale research in Europe. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7

Good Clinical Practice (GCP), a set of internationally recognised quality standards for clinical trial conduct produced by the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), are designed to be transposed into regulations by legislative bodies. From a European Union (EU) perspective, this was enacted by the Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC 8 and the subsequent Regulation (EU) 536/2014 (henceforth called “the Regulation”). 9 The aim of GCP, and subsequent legislation, is to create favourable environments for conducting clinical trials while maintaining high ethical and safety standards. A recent experience by MEMO Research (MEMO), a UK academic clinical trial centre, suggests that this goal has not been met and may be hampered by outdated legislation.

In expanding a Post Authorisation Safety Study clinical trial, 10 at European Medicine Agency (EMA) request, MEMO encountered barriers to implementing an existing DTP system in additional countries. 3 IMPs were already being posted directly from a UK research pharmacy to patients' home addresses in the UK and Denmark. 11 Several Medical Product Licensing Authorities (MPLAs) advised that it was either illegal or impossible to use DTP to supply IMP from a UK research pharmacy to trial patients in their country. In Sweden, where the supply of IMP from a UK pharmacy was permitted, local regulations required that patients had to collect their study medications from a Swedish pharmacy, negating the convenience of home delivery. 11 These unexpected barriers restricted the planned expansion of this safety study, potentially reducing the utility of the study results for regulators and clinical decision‐makers throughout Europe. Of note, the IMPs in this trial were being used within their marketing authorisation; this clinical trial would be considered part of a “low‐intervention clinical trial” under the terms of the Regulation. 12 This experience prompted us to explore the legal issues around direct IMP supply to patients in Europe. The COVID‐19 pandemic, occurring during this project, unexpectedly forced increased focus on remote trial activities, including DTP. We adjusted our methods to capture any COVID‐specific regulation or guidance.

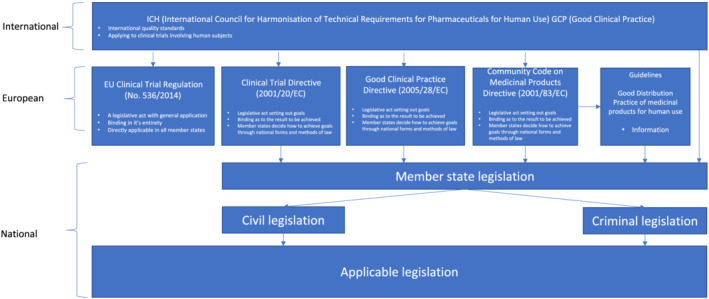

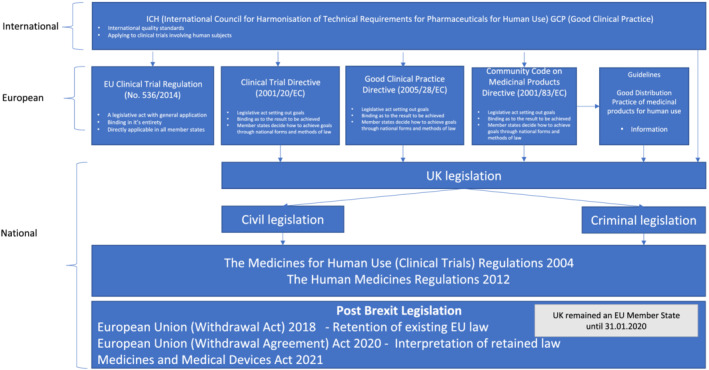

As some legal terms and their usage may be unfamiliar to readers, we have provided a glossary (Table 1). We also provide schematic representations of the interaction of international and national guidelines and legislation (Figure 1) and the legal position of clinical trials in the UK due to withdrawal from the EU in January 2020 (Figure 2).

TABLE 1.

Glossary of legal terms

| Term(s) | Context and explanation |

|---|---|

| European Union (EU) | A political and economic union of 27 Member States that are located in Europe. |

| Member State | EU Member States have agreed by treaty to share sovereignty in some aspects of government through the institutions of the EU. |

| Third country | A country that is not a member of the EU. |

| Regulation | An EU Regulation is a binding legislative act that must be applied in its entirety in every EU Member State. |

| Directive | An EU Directive instructs all Member States on a specific goal to be achieved. Member States then have the freedom to devise their national laws to achieve this goal. |

| National law | A national law is a law devised and enacted in an individual state. EU Directives and Regulations use the phrase “national” in their provisions to denote domestic Member State legislation. |

| “Civil and criminal liability” |

“This Regulation is without prejudice to national and Union law on the civil and criminal liability of a sponsor or an investigator” a And “Where, in the course of a clinical trial, damage caused to the subject leads to the civil or criminal liability of the investigator or the sponsor, the conditions for liability in such cases, including issues of causality and the level of damages and sanctions, should remain governed by national law” b Clinical trial investigators and sponsors are responsible for adhering to applicable legislation, both EU (where this applies) and national. Where legislation allows claims related to breaches to be brought in civil courts, e.g., negligence, this responsibility is termed “civil liability”. Where legislation permits the imposition of a punishment, e.g., administrative fine, or term of imprisonment, this is termed “criminal liability”. |

| Authorised, legalised |

Both terms are commonly used, often interchangeably, in the European clinical trial environment with various meanings, including: (a) the approval of a clinical trial by MPLAs and ethics boards, (b) the approval of a medicinal product(s) for use in particular situations, (c) the approval granted by a national authority to a pharmacy resulting in registration, (d) the approval granted by a national authority to a pharmacy to sell products at a distance in certain circumstances. |

| “Not acceptable” and “not permitted” | Both terms are commonly used, often interchangeably, in spoken communication where a practice is deemed not to be allowed but is not known to have a specific criminal sanction directly imposed or enacted through legal provision. |

| Prohibited and illegal | Both words describe practices specifically sanctioned, i.e., having civil sanctions (e.g. administrative fine) or a criminal penalty (e.g. term of imprisonment) against them in legislation. |

Article 95 Regulation (EU) No. 536/2014 of the European Parliament on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use entered into force on 16 June 2014. https://eur‐lex.europa.eu/legal‐content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014R0536. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Recital 61 Regulation (EU) No. 536/2014 of the European Parliament on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use entered into force on 16 June 2014. https://eur‐lex.europa.eu/legal‐content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014R0536. Accessed 3 May 2021.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic illustration of the interaction of standards, regulations and legislation affecting clinical trials in the EU. Note: Legislation not specific to clinical trials may also be applicable to some aspects of trial conduct

FIGURE 2.

Schematic illustration of the interaction of standards, regulations and legislation affecting clinical trials in the UK. Note: Legislation not specific to clinical trials may also be applicable to some aspects of trial conduct

2. METHODS

The study comprised three activities: MPLA questionnaires, comparative legal analysis and review of COVID‐19 specific GCP guidance.

2.1. MPLA questionnaires

A questionnaire, comprising open and closed questions, was emailed to publicly available contact addresses for 28 EEA MPLAs (note in Section 4.3 regarding the inclusion of the Paul‐Ehrlich‐Institut (Germany) and the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO) (Netherlands)) in addition to the Swissmedic MPLA (a non‐EEA member) during June 2019 asking:

“If a Clinical Trial has been authorised in another Member State, would the direct shipment of IMPs to the patient's home in [name of country] be allowed/permitted by national legislation in [your country]?

Are there any domestic or national [name of country] laws that might prohibit this practice?” (see Appendix A)

A Data Protection Impact Assessment was carried out. 13 Follow‐up emails were sent in September and October 2019; 12 further follow‐up emails were sent to non‐responders in January 2020. In January 2021, emails requesting consent to publish direct quotations were sent to the MPLAs and the Paul‐Ehrlich‐Institut who had responded. Questionnaire responses were summarised and compared.

2.2. Comparative legal analysis

2.2.1. Identifying relevant legislation

In addition to national laws referred to by MPLA respondents, we sought to identify relevant national legislation. Beginning in June 2020, we searched the Law of Congress, Google, national governmental databases and websites, using simple word/phrases (including “Medicines/Medicinal Products Act” and “home”, “delivery”, and “IMP”) to identify applicable national legislation. The lack of regulation of DTP of IMPs quickly became apparent. However, we noted that many Member States referenced the Regulation in national clinical trials legislation. Henceforth, we used the Regulation's numerical reference, “536/2014”, as a primary search term in a replicable search strategy (see Appendix B). Where there were no up‐to‐date results in the English language for a particular country, we used the EUR‐Lex link using the CELEX number 14 for Directive 2001/20/EC to identify how a Member State transposed the Directive. 15 We used the Law Library of Congress database for crosschecking. 16 When Microsoft Word or PDF documents were available and downloaded only in their native language from the official webpages of each Member State, we uploaded the documents to the European Commission eTranslation tool. 17 Where there was no mention of civil or criminal liability, we used synonyms such as “infringement” and “offence”. Searches were completed in January 2021.

2.2.2. Analysis

We performed a comparative legal analysis 18 and identified common themes. Two additional issues were also considered: the UK departure from the EU, and delayed implementation of the Regulation pending a functional EU clinical trials database portal. We determined how and if Member States referred to the Regulation when addressing DTP of IMPs or related issues.

2.3. Review of COVID‐19 specific GCP guidance

2.3.1. Identifying COVID‐19 specific GCP guidance issued by MPLAs

In January 2021, we conducted a comprehensive review of current GCP guidelines on COVID‐19 mitigation measures. Guidelines that were not available in English were translated using Google translate 19 as the European Commission eTranslation Tool was no longer accessible after the UK departed the EU.

3. RESULTS

3.1. MPLA questionnaires

By June 2020, replies had been received from 18 MPLAs, the Paul‐Ehrlich‐Institut (Germany) and the CCMO (the Netherlands), a total of 20 replies (69%). Eleven MPLAs and the Paul‐Ehrlich‐Insitut granted consent to publish quotations (41%). Two MPLAs and CCMO declined to consent, and the remaining five MPLAs did not reply. Results are summarised in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Licensing Authorities summary replies 2019/2021 pre‐pandemic

| Country | Licensing Authorities | Date | Is it legal? (yes/no/no response/no, with qualifications) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Bundesamt für Sicherheit im Gesundheitswesen (Federal Office for Safety in Health Care) | 05.07.19 | “No. This is not permitted in Austria. Trial medication may not be shipped directly to trial participants by the manufacturer/depositor/wholesaler or by the investigator/trial site. The dispatch of medicinal products to consumers is distance selling, which is reserved for public pharmacies in Austria and authorised pharmacies in the EEA in accordance with §59 Austrian Medicinal Products Act. However, it is permissible for the manufacturer/deposit taker/wholesaler to send the investigational products for a specific study participant to a pharmacy accessible to this patient at the request of an investigator. The pharmacy then dispatches the investigational products to the trial participant locally. Investigational medicinal products which are not prescription‐only human medicinal specialities and authorised or registered in Austria (e.g. for phase IV clinical trials) can be sent directly to study participants by public pharmacies in Austria or by pharmacies in other EEA member states authorised to sell at a distance by order of the investigator. The GMDP and GCP requirements for the shipping and storage of investigational medicinal products shall in any case be taken into account.” a |

| Belgium | Agence fédérale des médicaments et des produits de santé (Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products) | 11.07.19 | Consent to publish quotation not granted |

| Bulgaria | изпълнителна агенция лo лекарстBATA (Bulgarian Drug Agency) | ‐ | No response |

| Croatia | HALMED Agencija za lijekove i medicinske proizvode (Agency for Medical Devices and Medical Products of Croatia) | ‐ | No response |

| Cyprus | φαρμακευτικές υπηρεσίες ϒπουργείο ϒγείας (Ministry of Health – Pharmaceutical Services) | ‐ | No response |

| Czech Republic | SUKL Státní ústav pro kontrolu léčiv (SUKL State Institute for Drug Control) | 13.06.19 | “No, it is not possible in the Czech Republic. The direct shipment of IMPs by sponsors to the patient's home is not allowed by our national legislation. IMPs have to be dispensed by the investigator at the clinical trial site or by pharmacy involved in the respective clinical trial. All clinical trials ongoing in the Czech Republic have to be approved by State Institute for Drug Control (hereinafter “SÚKL”) and Czech ethics committees (hereinafter the “EC”). A clinical trial authorized in another Member State if not approved by SÚKL and EC cannot be initiated in the Czech Republic. In line with Section 85(1) of Act No. 378/2007 Coll., on Medicinal Products, as amended (the “Medicinal Products Act”), medicinal products can be dispensed by mail‐order delivery only if they are duly authorized in compliance with Medicinal Products Act and provided that such medicinal products are not subject to medical prescription and no further restrictions in terms of dispensing are imposed by the respective decision on marketing authorization. The implementing legal regulation stipulates the method of mail‐order dispensing.” |

| Denmark | Lægemiddelstyrelsen (Danish Medicines Agency) | 21.10.19 | “It is OK to submit IMPs from a depot/store in another EU‐country directly to the trial subjects home as long it is stated in the trial application.” |

| Republic of Estonia | Ravimiamet (State Agency of Medicines) | 19.09.19 | “The short answer would be no. I would like to direct you to our website: https://ravimiamet.ee/en/sending‐medicinal‐products. The regulation is based on our Medicinal products act.” |

| Finland | Lääkealan turvallisuus‐ ja kehittämiskeskus Fimea (Finnish Medicines Agency) | 24.07.19 | “Finnish legislation does not allow such procedure with investigational medical products” b |

| France | ANSM Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé (National Agency for the Safety of Medicine and Health Products) | ‐ | No response |

| Germany | Paul‐Ehrlich‐Institut (Federal Institute for Vaccines and Biomedicines) c | 14.06.19 | “The sending of investigational medicinal product (IMP), directly to the home address of patients/participants of a clinical trial abroad from a different Member State would be illegal. If a clinical trial was licensed by the regulatory authority of the different EU Member State, trial subjects based in Germany cannot be legally allowed to receive the IMP in the post from that Member State, as the approval of the clinical trial from the Competent Authorities in Germany is required.” c |

| Greece | Ο Εθνικός Οργανισμός Φαρμάκων (The National Organisation for Medicines) | ‐ | No response |

| Hungary | Országos Gyógyszerészeti és Elelmezés‐egészségügyi Intézet (The National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition) | ‐ | No response |

| Ireland | An tÚdarás Rialála Táirgí Sláinte (The Health Products Regulatory Authority) | ‐ | Consent to publish quotation not granted |

| Italy | AIFA Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (Italian Medicines Agency) | ‐ | No response |

| Latvia | Zāļu valsts aǵentūra (State Agency of Medicines of the Republic of Latvia) | ‐ | Consent to publish quotation not granted |

| Lithuania | Valstybinė Vaistų Kontrolės Tarnyba (State Medicines Control Agency) | 13.06.19 | “Regarding your question – There is no direct provisions in local legislation regarding such specific situation or prohibition for direct shipment of IMP to the patient's home. However, according to our legislation this is not possible in Lithuania. There are statements in the legislation that importer or receiver of IMP should have specific licences for IMP related activities in order to ensure control, accountability and/or appropriate storage conditions. So this is not possible to ensure at patient's home.” d |

| Luxembourg | SANTE (Ministère de la Santé) (SANTE Ministry of Health) | 15.10.19 | Consent to publish quotation not granted |

| Malta | Awtorità tal‐mediċini ta ‘Malta (Malta Medicines Authority) | ‐ | Consent to publish quotation not granted e |

| Netherlands | Centrale commissie met onderzoek naar mensen (Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects) | ‐ | Consent to publish quotation not granted f |

| Norway | Statens legemiddelverk (Norwegian Medicines Agency) |

20.08.19 08.10.19 |

“No. Manufacturers/importers and wholesalers may only deliver medicines for clinical trials to pharmacies and exceptionally, if approved by the Norwegian Medicines Agency, direct to the clinical trial site (Regulation: 1993‐12‐21 Forskrift om grossistvirksomhet med legemidler §13, https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/1993‐12‐21‐1219). Generally the patient shall receive the medication at the clinical site or at the pharmacy. The clinical site, or pharmacy on behalf of clinical site, only in exceptional cases and only if approved by the Norwegian Medicines Agency in connection with the application, may send IMPs to patients provided the trial site is responsible for the medication (all relevant aspects as described below). Regulation: §4–5 i forskrift om kliniskutprøving (https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2009‐10‐30‐1321#KAPITTEL_4).” “It is not allowed to send investigational medicinal products (IMPs) from abroad and directly to trial subjects/patients. According to the Norwegian Regulation relating to clinical trials on medicinal products for human use (Forskrift om klinisk utprøving av legemidler til mennesker 2009‐10‐30‐1321) paragraph 4–5, IMP should in general be handled by a pharmacy or the clinical site. Only in exceptional cases it is possible to apply in the application for a clinical study to handle IMP a different way. In such a case a detailed justification would be required. ICH GCP and Annex 13 should be followed. (ICH GCP sections 4.6.1–4.6.6 are applicable.) IMP should not be sent through the post.” |

| Poland |

Urząd Rejestracji Produktów Leczniczych, Wyrobów Medycznych i Produktów Biobójczych (Office for Registration of Medicinal Products, Medical Devices and Biocidal Products) |

‐ |

Consent to publish quotation not granted |

| Portugal |

Autoridade Nacional do Medicamento e Produtos de Saúde (National Authority of Medicines and Health Products) |

‐ |

No response |

| Romania | Agenţia Naţionalǎ a Medicamentului și a Dispozitivelor Medicale din România (National Authority of Medicines and Medical Devices) | ‐ |

No response |

| Slovakia | SUKL Štátní ústav pre kontrolu liéčiv (State Institute for Drug Control) | 03.02.20 | “As per national legislation Act No. 362/2011, §38, point 10, IMP can be stored only in the pharmacy or at the investigational site (if suitable storage area/conditions available) and only pharmacist or investigator can dispense IMP to the patient therefore direct shipment of IMPs to the patient's home in Slovakia is not allowed. Unfortunately English version of the national legislation is not available. Please see below link to national legislation Act No. 362/2011: https://www.slov‐lex.sk/pravne‐predpisy/SK/ZZ/2011/362/20200101” |

| Slovenia | Agencija Republike Slovenije za zdravila in medicinske pripomočke (Agency for Medicinal Products and Medical Devices of the Republic of Slovenia) | ‐ | No response |

| Spain | Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products) | 12.07.19 | “No. If the clinical trial is performed in Spain, the medication must be collected in the hospital for traceability of the investigational product (IP). If the patient is Spanish (living in Spain) but the trial is not in Spain, it will depend on what the national authority that authorized the trial allows based on the characteristics of the research and patients safety.” g |

| Sweden | Läkemedelsverket (Swedish Medical Products Agency) | 19.06.19 | “If a Swedish subject participates in a clinical trial in another member state, the IMP should be distributed to the subject by an investigator at a trial site in that member state according to the legislation in that country. For clinical trials with investigational sites in Sweden the IMP has to pass a Swedish based wholesaler or a Swedish pharmacy before it is sent to the site. In certain circumstances it could be justified to send the IMP to the subject's home, from the trial site or the wholesaler/pharmacy.” |

| Switzerland | Schweizerisches Heilmittelinstitut/Institut suisse des produits thérapeutiques/Istituto svizzero per gli agenti terapeutici (Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products) | 21.06.19 | Consent to publish quotation not granted |

| UK | Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency |

11.06.19 05.11.19 |

“CTA authorisation by a competent authority is required in any country where trial activity takes place. For example, if there is trial activity such as screening and safety monitoring then the facilities where these are done would be considered trial sites and regulatory approval is required in that country. Please note, however, that legislation in other EU, non‐UK countries may result in different requirements and we therefore suggest you contact the relevant competent authorities in the countries where trial activity may take place.” “There is nothing in current legislation to prevent sending investigational medicinal products (IMPs) through the post, if appropriate, as long as the relevant checks and balances are in place and a risk assessment has been carried out, for example to ensure that the product integrity will not be compromised during any such transit. Sufficient monitoring will need to be in place for products that are more liable to degrade and the sponsor will need to ensure that there is a mechanism for confirming that the subjects themselves receive the IMP and that it is not delivered to someone else in error. We would always recommend that a trial sponsor speak to MHRA first if they are proposing such a mechanism for provision of IMP to the trial participant.” |

Austrian MPLA issued up‐to‐date guidance in January 2021 to reflect the changing situation following the pandemic. Investigator‐to‐patient shipment is now possible. Direct sponsor‐to‐patient shipment is not permitted.

Some sections of the Finnish Medicines Act are currently under revision (January 2021) to permit the national implementation of the Regulation later this year.

The Paul‐Ehrlich‐Institut in January 2021 emphasised that the correct wording of the initial question posed is important. The response in 2019 was framed in a context and on the understanding that no approval was granted by the competent authorities of that EU country. In January 2021, the Paul‐Ehrlich‐Institut noted that, “there is definitively a paramount difference in sending IMPs by post with or without the approval of the clinical trial in a country.” Bundesinstitut für Impfstoffe und biomedizinische Arzneimittel (The Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices) should have been included as the German Licensing Authority instead of the Paul‐Ehrlich‐Institut for completeness and continuity.

Lithuanian MPLA issued up‐to‐date guidance in January 2021. It is now possible.

Maltese MPLA confirmed in January 2021 that a clinical trial cannot be started in Malta without approvals from the health ethics committee and the licensing authority.

The Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO) in the Netherlands contact email was included in the empirical analysis following non‐response from the incorrectly spelt contact email address (info-bi@cgb-meb.nl) for the College ter Beoordeling van Geneesmiddelen in Nederland/Medicines Evaluation Board in the Netherlands; correct spelling is info-bi@cbg-meb.nl.

Spanish MPLA confirmed in January 2021 that, in light of the pandemic, EMA GCP Volume 10 guidance is followed and also that Pharmacy Departments can consider other forms of delivery but must be assessed in each particular case.

DTP was not widely authorised, though different phrases were used to convey this message. In Austria and the Republic of Estonia, it was “not permitted”; in the Czech Republic and Lithuania, it was “not possible”; in Finland, Norway, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden, it was “not allowed”; and in Germany, it was “illegal”. In contrast, in Denmark and the UK, DTP of IMPs was acceptable provided it was outlined in the trial application and a “risk assessment” regarding both product and patient completed.

A deeper contextual analysis demonstrated that, due to the lack of specific domestic regulation for DTP of IMPs, some MPLAs referred to “distance selling” legislation and “dispensation by mail‐order delivery” practices, e.g. the Austrian and Czech Republic MPLAs. Other MPLAs, e.g. Estonia, said “no”, indicating that the practice is neither allowed nor permitted, but not stipulating which legislation applied. The UK MPLA indicated “there is nothing in current legislation to prevent sending IMPs in the post” provided authorisation, screening, safety monitoring and risk assessments are carried out.

In seeking consent to publish responses, we obtained updates from four MPLAs. The Austrian MPLA confirmed that “investigator‐to‐patient” shipment is now permitted but that only in exceptional circumstances can “sponsor‐to‐patient” delivery occur. The Paul‐Ehrlich‐Institut emphasised a need for careful wording and highlighted: “So there is definitively a paramount difference in sending IMPs by post with or without the approval of the clinical trial in a country.” The Lithuanian MPLA confirmed DTP is currently possible due to the pandemic, referring to recent EMA guidance issued in March 2020. 20 The Spanish MPLA confirmed that guidance issued in November 2020 applies: provided the Pharmacy Department has assessed each particular case, there is scope for DTP to apply to all clinical trials. 21

3.2. Legal interpretation and comparison

We did not identify a specific reference to DTP of IMPs for clinical trials in national civil and criminal sanctions. Many sanctions imposed by national legislation for contraventions of different clinical trial regulations were open to interpretation whether they applied to DTP of IMP. We identified four common themes: GCP, suitability of clinical trial sites, distribution of medicines, and patient safety. Measures and penalties applied for breaches of these themes are summarised below. Due to the extent of the project, it was not possible to include every potentially applicable sanction.

3.2.1. GCP

Specific monetary fines with the potential for increased fines for repeat breaches of GCP are imposed in several countries, ranging from approx. €500 in Bulgaria to €120 000 in Slovenia. Custodial sentences may also be applied, with the longest stipulated duration “not exceeding three years” in Swiss legislation. These results are summarised in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

National legislative penalties imposed for breach of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Guidelines

| Country | Penalties for breach of GCP section/article listed in third column | Related and linked articles and sections to “GCP” in second column |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 84(1) (18) “EUR 25000 in repetitive cases of up to EUR 50000″ | Section 28 – GCP a |

| Bulgaria | Article 294 “Whoever infringes the provisions of this Act or the regulations for its implementation, except for the cases according to Art. 281–293, shall be penalised with a fine from BGN 1000 to BGN 3000 and in case of repeated perpetration of the same infringement – with a fine from BGN 3000 to BGN 5000.” | Article 86(1) – GCP b |

| Denmark | 35(iv) “fine or imprisonment for up to four months” | Art 47 – Protocol and GCP c |

| Germany | 96 sub‐section 10 penal provision | Section 40 sub‐section 1 ‐ GCP.” d |

| Ireland | 44 “€3000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or both” | Reg 24(1) (2) – GCP e |

| Italy | 41(4) “Subject to pecuniary administrative sanction from 15 000 to 90 000 euros” | Art 3 – GCP f |

| Latvia | (85) “The State Agency of Medicines has the right to prohibit a clinical trial.” | Reg 13 – GCP g |

| Lithuania | 1(2) “If signs of a criminal offence or administrative misconduct are identified during a GCP inspection …. Shall be forwarded to the authority competent to investigate the relevant cases” | 1(2) – GCP inspection h |

| Luxembourg |

(19) “Breaches of the provisions of these regulations are punishable (48) … law of August 28, 1998 … Who have obtained … assistance … shall be liable to the penalties … in Article 496 of the Criminal Code” … “EUR 251 to EUR 2.500″. |

Article 1(3) GCP i |

| Poland | (126(a)) “punishable by a fine, restricted freedom or imprisonment for up to 2 years.” | Article 126a. (384) GCP (chapter 2a) j |

| Romania | (180) “should promptly induce the sponsor to take action to ensure compliance.” | (180) GCP k |

| Slovakia | (138(18)(j)) “The contracting authority commits another administrative offense if does not follow the principles of good clinical practice.” | Section 44(l) GCP l |

| Slovenia | (117) (1) “EUR 8000 to 120 000” | Article 54(3) “Principles of Good Practice” m |

| Switzerland | (86(1)(f)) “A custodial sentence not exceeding three years or a monetary penalty” | Art 22(2) “Good Clinical Trial Practice” n |

Austria: Section 84(1) (18) and Section 28 Austrian Medicinal Products Act ‐ Breach of Good Clinical Practice. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10010441. Accessed 20 December 2020.

Bulgaria: Article 86(1) and 294 Medicinal Products in Human Medicine Act Amended and Supplemented SG 64/13 August 2019. https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/legal_acts/201910_MEDICINAL%20PRODUCTS%20IN%20HUMAN%20MEDICINE%20ACT.pdf. Accessed 30 January 2021.

Denmark: Section 35 and Section 47 The Danish Act on Clinical Trials of Medicinal Products Law on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products Law No. 620 of 08/06/2016 (Applicable). https://laegemiddelstyrelsen.dk/en/news/2016/new‐danish‐act‐on‐clinical‐trials/~/media/0BDD2C209E3A472EB4DFC00661683433.ashx. Accessed 20 December 2020.

Germany: Section 97 sub‐section 10 and Section 40 sub‐section 1 Medicinal Products Act. http://www.gesetze‐im‐internet.de/englisch_amg/englisch_amg.html#p2059. Accessed 21 January 2021.

Ireland: Regulation 24(1) (2) and 44 Statutory Instrument No. 190/2004 European Communities (Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use), Regulations 2004. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2004/si/190/made/en/print. Accessed 20 December 2020.

Italy: Article 41(4) and 3 Legislative Decree 6 November 2007 n. 200. Implementation of Directive 2005/28/EC containing detailed principles and guidelines for good clinical practice relating to investigational medicinal products for human use as well as requirements for the authorization to manufacture or import such medicinal products. https://www.normattiva.it/uri‐res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo:2007;200. Accessed 22 January 2021.

Latvia: Regulation 13 and 85 Regulations Regarding the Procedures for Conduct of Clinical Trials and Non‐interventional Trials of Medicinal Products, Labelling of Investigational Medicinal Products and the Procedures for Assessment of Conformity of Clinical Trial of Medicinal Products with the Requirements of Good Clinical Practice No 289/2010. https://likumi.lv/ta/en/id/207398‐regulations‐regarding‐the‐procedures‐for‐conduct‐of‐clinical‐trials‐and‐non‐interventional‐trials‐of‐medicinal‐products‐labelling‐of‐investigational‐medicinal‐products‐and‐the‐procedures‐for‐assessment‐of‐conformity‐of‐clinical‐trial‐of‐medicinal‐products‐with‐the‐requirements‐of‐good‐clinical‐practice. Accessed 20 December 2020.

Lithuania: Regulation 1(2) Order Approval of the Procedure for the Authorisation of the Control of the Certificates and Authorisations for the Conduct of a Clinical Trial of a Medicinal Product 2006 V‐435. https://e‐seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalActEditions/lt/TAD/TAIS.277308?faces‐redirect=true. Accessed 20 December 2020.

Luxembourg: Regulation 1(3) and 19 Grand Ducal Regulation of 30 May 2005 on the application of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials of medicinal products for human use. http://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/rgd/2005/05/30/n5/jo. Accessed 20 December 2020. Article 48 Act of 28 August 1998 on hospital establishments. https://www.cner.lu/Portals/0/loi%20hospitali%C3%A8re%201998.pdf. Accessed 20 December 2020.

Poland: Article 126a Act of 6 September 2001 Pharmaceutical Law – Breach of Good Clinical Practice (Chapter 2a Article 37(b) (1) and Article 37(b) (2)). https://www.gif.gov.pl/download/3/5000/pharmaceuticallaw‐june2009.pdf. Accessed 1 January 2021.

Romania: Article 180 Annex to HCS no. 2/24.10.2017. The Guide on good practice in the clinical trial – Deviation from Compliance. https://www.anm.ro/medicamente‐de‐uz‐uman/studii‐clinice/legislatie‐specifica‐pentru‐studii‐clinice/. Accessed 31 December 2020. Article 67 – Order No. 904 of 25 July 2006 for the approval of the Rules on the implementation of good practice rules in the conduct of clinical trials conducted with medicinal products for human use. (No. 671, 4 August 2006). https://www.anm.ro/medicamente‐de‐uz‐uman/studii‐clinice/legislatie‐specifica‐pentru‐studii‐clinice/. Accessed 31 December 2020.

Slovakia: Section 138(18)(j) – Act no. 362/2011 Coll. Act on Medicinal Products and Medical Devices and Amendments to Certain Acts. https://www.zakonypreludi.sk/zz/2011‐362. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Slovenia: Article 117 for breach of Article 54(3) – Medical Products Act. http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO4280. Accessed 2 January 2021.

Switzerland: Regulation 86(1)(f) and 22(2) Federal Act on Medicinal Products and Medical Devices (Therapeutic Products Act, TPA 812.21). https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified‐compilation/20002716/202001010000/812.21.pdf. Accessed 2 January 2021.

3.2.2. Suitability of clinical trial sites

The “suitability of clinical trial sites”, detailed in Article 50 of the Regulation, does not explicitly mention DTP of IMPs, simply stating that the “facilities where the clinical trial is to be conducted shall be suitable for the conduct of the clinical trial in compliance with the requirements of this Regulation.” A patient's home is not mentioned as a site of trial activity in the context of clinical trial regulations; indeed, the EMA has provided a “site suitability form”, which makes no mention of the patient's home. 22 Specific monetary fines with the potential for increased fines for repeat breaches of the general provisions of The Regulation are imposed in several countries, ranging from €251 in Luxembourg to €250 000 in Belgium (for breach of Article 50, specifically). Belgian legislation also details a custodial sentence of up to two years for Article 50 breaches. These results are summarised in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

National legislative penalties for breach of “Suitability of Trial Sites” (The Regulation)

| Country | Penalties for breach of section of relevant legislation in third column | Related and linked articles and sections to “suitability of trial sites” in second column |

|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | (286) “BGN 5000 to BGN 10000 and in case of repeated … commitment …. BGN 10 000 to BGN 20 000.” | (294) “This Act or The Regulation” a |

| Belgium | (44) “imprisonment for a term of one month to two years and/or €500 to €250 000, …” | Art 37 “ Without prejudice to Article 50 of the Regulation, phase I centres may be accredited by the AFMPS” b |

| Italy | (95 of The Regulation) “This Regulation is without prejudice to national and Union law on the civil and criminal liability of a sponsor or an investigator. | (5) “the discipline regarding the suitability of the facilities where the clinical trial is conducted is adapted to the provisions of Regulation (EU) No. 536/2014” c |

| Latvia | (25) “The sponsor shall be responsible … the supply thereof to the clinical trial site (research centre), … the specification of conditions and duration of storage and, where necessary, the dilution liquids and medical devices for the infusion of the medicinal product.” | (25) “Such persons have the duty to observe the storage conditions of the investigational medicinal product.” d |

| Luxembourg |

(19) “Breaches of the provisions of these regulations are punishable (48) … law of August 28, 1998 … Who have obtained … assistance … shall be liable to the penalties … in Article 496 of the Criminal Code,” … “EUR 251 to EUR 2500″. |

Article 1(4) “The provisions of these regulations apply regardless of the environment, hospital or extra‐hospital, in which the research is conducted.” e |

| Malta | 13(2)(b) “the Licensing Authority may exclude from subregulation (1) the process of making changes to the packaging of investigational medicinal products..” | (13(2)(b)) “where this process is carried out by pharmacists or persons authorised to carry out such processes in hospital, health centre or clinic within which solely such investigational medicinal products are intended for use.” f |

| Romania | (181) “If serious and/or persistent deviations from the investigator/institution are identified through monitoring and/or auditing, the sponsor shall stop the institution/investigator's participation in the study; … the sponsor shall promptly inform the competent authorities.” | (164(b)) “Responsibilites of the Monitor …. The suitability of the facilities for conducting the study, including laboratories, equipment and work team for the proper and safe conduct of the study …” g |

| Portugal | (45(1)(c)) “at least €500 and maximum €50 000, and … legal persons, a minimum … €5000 and maximum €750 000″ | (45(1)(c)) “Conduct or continuation of clinical study in a clinical study centre not endowed with adequate material and human resources.” h |

Bulgaria: Article 286 and Article 294 Medicinal Products in Human Medicine Act Amended and Supplemented SG 64/13 August 2019. https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/legal_acts/201910_MEDICINAL%20PRODUCTS%20IN%20HUMAN%20MEDICINE%20ACT.pdf. Accessed 20 December 2020.

Belgium: Article 37, 44 and 45 Federal Medicines and Health Products Agency [C‐2017/12146] May, 7, 2017 – Human Drugs Clinical Trials Act, 1. http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=fr&la=F&table_name=loi&cn=2017050704. Accessed 21 December 2020.

Italy: Article 5 Legislative Decree No. 52 of 14 May 2019. Implementation of the delegation for the reorganization and reform of the legislation on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use pursuant to Article 1, paragraphs 1 and 2 of Law No. 3 of 11 January 2018 (19G00059). https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2019/06/12/19G00059/SG. Accessed 22 January 2021. Article 95 of Regulation (EU) No. 536/2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. https://eur‐lex.europa.eu/legal‐content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014R0536&from=EN. Accessed 22 January 2021.

Latvia: Regulation 25 of Number 289. Regulations regarding the procedures, for conduct of clinical trials and non‐interventional trials of medicinal products and the procedures for assessment of conformity of clinical trial of medicinal products with the requirements of good clinical practice. https://likumi.lv/ta/en/id/207398‐regulations‐regarding‐the‐procedures‐for‐conduct‐of‐clinical‐trials‐and‐non‐interventional‐trials‐of‐medicinal‐products‐labelling‐of‐investigational‐medicinal‐products‐and‐the‐procedures‐for‐assessment‐of‐conformity‐of‐clinical‐trial‐of‐medicinal‐products‐with‐the‐requirements‐of‐good‐clinical‐practice. Accessed 31 December 2020.

Luxembourg: Regulation 1(3) and 19 Grand Ducal Regulation of 30 May 2005 on the application of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials of medicinal products for human use. http://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/rgd/2005/05/30/n5/jo. Accessed 31 December 2020. Article 48 of Act of 28 August 1998 on hospital establishments. https://www.cner.lu/Portals/0/loi%20hospitali%C3%A8re%201998.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2020.

Malta: Section 13(2)(b) of Clinical Trials Subsidiary Legislation (S.L. 458/43). http://justiceservices.gov.mt/DownloadDocument.aspx?app=lom&itemid=11281&l=1. Accessed 31 December 2020.

Romania: Article 5(34), 5(57),164(b) and 181 Annex to HCS no. 2/24.10.2017. The Guide on good practice in the clinical trial. https://www.anm.ro/medicamente‐de‐uz‐uman/studii‐clinice/legislatie‐specifica‐pentru‐studii‐clinice/. Accessed 31 December 2020. Note, in Article 5(57), there is a definition for “multi‐centre clinical study” – “the clinical study carried out after a single protocol, but in several centres and therefore by several investigators, and the centres in which the study is conducted can only be found in Romania or in several countries.”

Portugal: Article 45(1)(c) Law No. 21/2014 of 16 April approves the law of clinical investigation. Contra‐ordinations. Approves the law of clinical investigation. Also Article 26(1)(e) Law No. 21/2014 of 16 April approves the law of clinical investigation. The Application for Authorisation is to include: “The identification of the clinical study centres involved and the statement issued by the head of the clinical study centres indicating the terms of their participation”. https://www.infarmed.pt/documents/15786/1068535/036‐B1_Lei_21_2014_1alt.pdf. Accessed 21 December 2020.

3.2.3. Distribution of medicines

Sanctions that could be applied for breach of regulations regarding distribution of medicinal products in clinical trials included monetary fines of between €500 (Belgium) and €1000 (Spain) and custodial sentences of between one month and two years (Belgium).

Responses to questionnaires drew our attention to some MPLAs also identifying legislation referring to distance selling and mail‐order services prohibitions. For example, Austria has an administrative offence for providing medicinal products by vending machines or “other self‐service forms”, with a monetary fine of €7500–€14 000. Similarly, a €5000 fine may be levied for the distribution of medicinal products by mail order. In jurisdictions where medicinal products may be sold without a prescription, e.g., in Poland, mail‐order sales are permitted. These results are summarised in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

National legislative penalties for breach of Distribution of Medicines

| Country | Penalties for breach of section of relevant legislation in third column | Related and linked articles and sections to Distribution of Medicines in second column |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | (83(1)(5)) “Who dispenses medicinal products contrary to Sections 57 … guilty of an administrative offence … fine of up to 7500 euros … or 14 000 euros | (59(9)) “Self‐service or distance selling of medicinal product is prohibited.” a |

| Belgium | (44) “imprisonment for a term of one month to two years and/or a fine of EUR 500 to EUR 250 000″ | (44(3)) “a person who …, delivered, distributed, supplied, imported or exported … knowing that they … are not in conformity with the provisions of this law.” b |

| Germany |

97(2) (12) “an administrative offence shall be deemed to have been committed” 97(2) (16) “an administrative offence shall be deemed to have been committed in breach of section 52 sub‐section 1” 25(5) (2) “€5000” |

47(1) “in breach of Section 47 sub‐section 1, dispenses medicinal products which may be dispensed to consumers without prescription to persons or bodies other than those specified therein or dispenses them in breach of Section 47 sub‐section 1a or obtains the same in breach of Section 47 sub‐section 2 sentence 1.” 52(1) “Medicinal products as defined in Section 2 sub‐section 1 or sub‐section 2 number 1 may: 1. Not be placed on the market by means of vending machines, 2. Nor be placed on the market using other forms of self‐service.” (21(2)(1a)) “distribution of which by mail order is not permitted for reasons of medicinal product safety, or consumer protection, unless the medicinal product safety and consumer protection can be guaranteed by appropriate means and the acceptance of the risks are justified and the risks and disproportionate” c |

| Ireland | (21) “Enforcement and execution (authorized officer can demand the furnishing of particulars, seizes the medicinal product, be required to break open any container or package, open any vending machine)” | (19) “A person shall not supply by mail order any medicinal product.” d |

| Latvia | (14(5)) “Officials of the State Pharmaceutical Inspectorate … have the right … | 14(5) … to prohibit the manufacture or distribution of medicinal products and withdraw and confiscate medicinal products if their manufacture or distribution is performed in violation of the requirements specified in regulatory enactments in the field of pharmacy.” e |

| Netherlands | (110) “Our Minister may impose an administrative fine of no more than the amount of the sixth category (€870 000), referred to in Article 23, fourth paragraph, of the Criminal Code for a violation of the provisions by or pursuant to” |

(34(2)) “Medicines are only supplied by the manufacturer to other manufacturers, wholesalers and to those who are authorized to hand over the relevant medicines. Contrary to the first paragraph, medicines for research by the manufacturer are only supplied to: a. a person who carries out medical scientific research as referred to in Article 1, first paragraph, under f, of the Medical Scientific Research with Human Rights Act, and who has a pharmacy in which a pharmacist works; b. a pharmacist who is registered in the register of established pharmacists as referred to in Article 61, fifth paragraph, and who is involved in that examination by the person who carries out an examination as referred to under a, other than on the basis of employment.” f |

| Spain |

(114(1)(b)) “EUR 30 001 – EUR 90 000 (114) (1)(c)) … EUR 90 001 to EUR 1000” |

(111(11)(b) (1)) “fails to comply with Good Distribution Practice will be a ‘serious infringement’” (111 (2) (c) (23)) to carry out, by pharmacy offices, distribution activities of medicines to … centres or natural persons without authorisation … or to carry out shipments of medicines outside the national territory will be a “very serious infringement” g |

| Slovakia |

S138 (3)(ag) “The holder of an authorization for the wholesale distribution of medicinal products for human use shall commit another administrative offense if … delivers a human medicinal product included in the list of categorized medicinal products … to a person other than the person provided for in § 18 par. 1 letter aa) (138(33)) “For other administrative offenses under paragraph 1 letter p), paragraph 2, letter bf), paragraph 3, letter (ag) and (al) impose a fine of between EUR 100 000 and EUR 1 000 000 on the Ministry of Health.” |

S18 (1)(aa) The holder of an authorization for the wholesale distribution of medicinal products is obliged … to supply a medicinal product for human use included in the list of categorized medicinal products only (1) the holder of an authorization to provide pharmaceutical care in a public pharmacy or in a hospital pharmacy (2) an outpatient medical facility to the specified extent.” h |

| Slovenia | “A fine of 8000 to 120 000 euros shall be imposed on a legal or natural person referred to in point 15 of Article 6 of this Act” | “The authorization for the manufacture of medicinal products shall also include the authorization for the wholesale distribution of medicinal products to the wholesaler and shall relate to medicinal products covered by the authorization for the manufacture of medicinal products.” i |

| Switzerland | (Article 27) “In principle, mail order trade in medicinal products is prohibited.” | (Article 27) “In principle, mail order trade in medicinal products is prohibited.” j |

| Norway | (Section 4, 5) | (Section 4, 5) “Unless the Norwegian Medicines Agency has decided otherwise in connection with the application for clinical trials, the trial preparation shall be handed out from the pharmacy or the individual trial site.” k |

| Poland | “It shall be permissible to conduct mail order sale of medicinal products dispensed without physician's prescription by generally accessible pharmacies and pharmacy outlets” | “It shall be permissible to conduct mail order sale of medicinal products dispensed without physician's prescription by generally accessible pharmacies and pharmacy outlets” l |

| UK | (49) “… liable … on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum and/or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three months or to both;” |

(13) “Supply of investigational medicinal products for the purpose of clinical trials.” (46) “provided that the conditions specified in Regulation 13(2) of those regulations are satisfied.” m |

| UK | (34) A person is guilty of an offence if the person contravenes the provisions of regulation 17(1), 18(1) or 32. |

(17) (1) “A person may not except in accordance with a licence (a ‘manufacturer's licence’) manufacture, assemble or import from a state other than an EEA State any medicinal product; or (b) possess a medicinal product for the purpose of any activity in sub‐paragraph (a). (17) (6) “Paragraph (1) does not apply to a person who imports a medicinal product for administration to himself or herself or to any other person who is a member of that person's household.” n |

Austria: Articles 59(5) and 83(1) (5) Medicines Act. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10010441. Accessed 24 January 2021.

Belgium: Article 44 and 44(3) Federal Medicines and Health Products Agency [C‐2017/12146] May, 7, 2017 – Human Drugs Clinical Trials Act, 1. http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=fr&la=F&table_name=loi&cn=2017050704. Accessed 21 December 2020.

Germany: Sections 47(1), 52(1), 97(2) (12), 97(2) (16) The Medicines Act. http://www.gesetze‐im‐internet.de/englisch_amg/englisch_amg.pdf. Accessed 13 January 2021. Sections 21(2)(1a) and 25(5) (2) The Pharmacy Act. https://www.gesetze‐im‐internet.de/apog/BJNR006970960.html. Accessed 13 January 2021.

Ireland: Regulation 19 and 21 Statutory Instrument 540/2003 (Medicinal Products (Prescription and Control of Supply) Regulations 2003. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2003/si/540/made/en/print. Accessed 13 January 2021.

Latvia: Section 14(5) Pharmacy Law. https://www.vestnesis.lv/ta/id/43127‐farmacijas‐likums. Accessed 24 January 2021.

Netherlands: Article 110 and 34(2) Dutch Medicines Act. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0021505/2019‐04‐02. Accessed 17 January 2021.

Spain: Regulation 111(2)(c) (23), 111(11)(b) (1) and 114(1)(b), 114(1)(c) Royal Decree 1090/2015 This is an unofficial English translation of the Royal Decree 1090/2015, revised by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices. https://www.aemps.gob.es/legislacion/espana/investigacionClinica/docs/Royal‐Decree‐1090‐2015_4‐December.pdf. Accessed 21 December 2020.

Slovakia: Section 138(33) and Section 138(3)(ag) and Section 18(1)(aa) of Act no. 362/2011 Coll. Act on Medicinal Products and Medical Devices and Amendments to Certain Acts. https://www.zakonypreludi.sk/zz/2011‐362. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Slovenia: Article 66(4) and 117(1) (8) Medical Products Act. http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO4280. Accessed 2 January 2021.

Switzerland: Article 27 Ordinance on Licensing in the Medical Products Sector (Medicinal Products Licensing Ordinance, MPLO, 812.212.1) https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified‐compilation/20180857/202001010000/812.212.1.pdf. Accessed 4 January 2021.

Norway: Section 4, 5 Regulation on Clinical Trials of Drugs for Humans 2009‐10‐30‐1321. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2009‐10‐30‐1321. Accessed 21 December 2020.

Poland: Article 68(3) and 68(3a)Act of 6 September 2001 Pharmaceutical Law. –https://www.gif.gov.pl/download/3/5000/pharmaceuticallaw‐june2009.pdf. Accessed 1 January 2021.

UK: Regulation 13 and 49 The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2004/1031/contents/made. Accessed 21 December 2020. Regulation 46 The Human Medicines Regulations 2012. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/1916/contents/made. Accessed 21 December 2020.

UK: Regulation 17(1), 17(6) and 34 The Human Medicines Regulations 2012. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/1916/contents/made. Accessed 21 December 2020.

3.2.4. Patient safety

This comparison was more straightforward than others as specific provisions often referred to “patient safety”. Defined monetary penalties ranged from €3000 minimum in Ireland to €7.2 million in Germany, imposed in the case of death. Specified terms of imprisonment ranged from three months to two years (UK). These results are summarised in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

National legislative penalties for breach of patient safety

| Country | Penalties for breach of section of relevant legislation in third column | Related and linked articles and sections to patient safety in second column |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | (84(1) (18)) “EUR 25 000 in repetitive cases … up to EUR 50 000.” | (34(5)) “The supply of the test subjects with the investigational product is safe and appropriate” a |

| Denmark | (35) “a fine or imprisonment up to 4 months” | (48 – The Regulation) – “Monitoring – Rights, safety and well‐being of subjects.” b |

| France | (6) “Failure to comply with articles 37, 42, 43 and 93 of European regulation (EU) No. 536/2014 … on the communication of information intended to be made available to the public in the union database is punishable by one year imprisonment and a fine of 15 000 euros.” | (42 – The Regulation) – “Reporting of SUSARS by the Sponsor to the Agency” c |

| Germany | (97) “not exceeding 25 000 euros. … In the case of the death … up to … 600 000 euros or … annuity … up to 36 000 euros, in the case of the death … up to … 120 million euros or … annuity … up to 7.2 million euros” | (97(2) (9)) “conducts the clinical trial of a medicinal product in breach of Section 40 sub‐section 1 sentence 3 number 7, (foreseeable risks involved in the clinical trial)” d |

| Ireland | (44) “not exceeding €3000 and/or to imprisonment … not exceeding six months” | (24) “Protection of clinical trial subjects” e |

| Italy | 41(4) “subject to pecuniary administrative sanction from 15 000 to 90 000 euros” | Art 3(1) – “The protection of the rights, safety and well‐being of subjects of experimentation prevails over the interests of science and of the company.” f |

| Malta | “It shall be an offence for the sponsor to start a clinical trial in Malta unless the Ethics Committee has issued a favourable opinion and the Licensing Authority has not informed the sponsor of any grounds for non‐acceptance.” | “Section 9 ‐ Commencement of a clinical trial” g |

| UK | (52) “a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum and/or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three months … on conviction on indictment and/or to a fine or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years” | (28) “Protection of clinical trial subjects” h |

Austria: Section 34(5) and Section 84(1) (18) Austrian Medicinal Products Act. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10010441. Accessed 20 December 2020.

Denmark: Regulation 35 and 48 The Danish Act on Clinical Trials of Medicinal Products Law on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products Law No. 620 of 08/06/2016 (Applicable). https://laegemiddelstyrelsen.dk/en/news/2016/new‐danish‐act‐on‐clinical‐trials/~/media/0BDD2C209E3A472EB4DFC00661683433.ashx. Accessed 20 December 2020.

France: Article L 1126‐12 Public Health Code. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000032719520&dateTexte=&categorieLien=id. Accessed 30 January 2021. Article 6 Ordinance No. 2016‐800 of June 16, 2016 relating to research involving the human person. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000032719520/. Accessed 30 January 2021.

Germany: Regulation 97 and 97(2) (9) Medicinal Products Act. http://www.gesetze‐im‐internet.de/englisch_amg/englisch_amg.pdf. Accessed 4 January 2021.

Ireland: Regulation 24 and 44 Statutory Instrument No. 190/2004 European Communities (Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use), Regulations 2004. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2004/si/190/made/en/print. Accessed 4 January 2020.

Italy: Article 41(4) and 3(1) Legislative Decree 6 November 2007 n. 200. Implementation of Directive 2005/28/EC containing detailed principles and guidelines for good clinical practice relating to investigational medicinal products for human use as well as requirements for the authorization to manufacture or import such medicinal products. https://www.normattiva.it/uri‐res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo:2007;200. Accessed 22 January 2021.

Malta: Section 9 Clinical Trials Subsidiary Legislation (S.L. 458/43). http://justiceservices.gov.mt/DownloadDocument.aspx?app=lom&itemid=11281&l=1. Accessed 22 January 2021.

UK: Regulation 28 and 52 The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2004/1031/contents/made. Accessed 21 December 2020. Regulation The Human Medicines Regulations 2012. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/1916/contents/made. Accessed 21 December 2020.

3.3. Review of COVID‐19 specific GCP guidance

It is clear from most MPLA websites that DTP of IMPs by courier or post may now be acceptable to mitigate COVID‐19 restrictions, subject to strict conditions. COVID‐19 specific GCP guidance results are summarised in Table 7.

TABLE 7.

Covid‐19 specific guidance

| Source | Date | Clinical trial COVID‐19 guidelines—What is now possible? |

|---|---|---|

| European Medicines Agency—European Commission, EudraLex – Volume 10 – Clinical trial guidelines. | 28.04.20 | “Member States are encouraged to implement the harmonised guidance to the maximum possible extent to mitigate and slow down the disruption of clinical research in Europe during the public health crisis. At the same time, sponsors and investigators need to take into account that national legislation and derogations cannot be superseded. Member States shall complement this guidance to create additional clarity on specific national legal requirements and derogations to them.” a |

| (Austria) Bundesamt für Sicherheit im Gesundheitswesen (Federal Office for Safety in Health Care) | 29.04.20 | “As stated in the current version of the EU Guideline (see above), in exceptional cases where the site is unable to handle the additional burden, the delivery can also be handled by the sponsor via an independent third party. In these cases, a substantial amendment (!) should be submitted to the BASG for each study. In this amendment, the investigator must confirm in writing that all the measures described here, including involvement of contract staff by trial site, have been exhausted and shipment from the centre to the participant is still not possible. The other recommendations of the guideline should also be observed.” b |

| (Belgium) Agence fédérale des médicaments et des produits de santé (Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products) | 20.04.20 | “On an exceptional basis during the COVID‐19 pandemic, the FAMHP is authorising hospital pharmacies to organise deliveries of medicinal products directly to the homes of ambulatory patients who are unable to go to the hospital. The progress of some “ambulatory” patients undergoing medical treatment is monitored by hospital doctors, but these patients are not hospitalised and pursue their treatment at home … For the duration of the COVID‐19 pandemic, the FAMHP is allowing hospital pharmacies to deliver medicinal products to the patient's home. It concerns medicines that may only be dispensed and/or reimbursed after delivery by the hospital pharmacist.” c |

| (Bulgaria) изпълнителна агенция лo лекарстBATA (Bulgarian Drug Agency) | 26.05.20 | “The patients' safety and health is a main priority and the changes in the conduct of clinical trials must be based on a detailed risk assessment. Due to the variability of clinical trials and possible cases, it is not practicable to cover all the situations. Trial subject safety in ensuring data validity and hence the quality of the clinical trial conduct, is the responsibility of the sponsor. Each stage of the process of taken measures and decisions should be documented.” d |

| (Croatia) HALMED Agencija za lijekove i medicinske proizvode (Agency for Medical Devices and Medical Products of Croatia) | ‐ |

HALMED website searched January 2021 for relevant guidance, none located. e |

| (Cyprus) φαρμακευτικές υπηρεσίες ϒπουργείο ϒγείας (Ministry of Health – Pharmaceutical Services) | 25.06.20 | Guidance in Greek language PDF file only. Not automatically translatable. English title: “Home delivery of medicines.” f |

| (Czech Republic) SUKL Státní ústav pro kontrolu léčiv (SUKL State Institute for Drug Control) | 22.12.20 | “In case it is not practicable to supply the study medication directly to the patient during the upcoming visit, it is possible, as an emergency situation, to send the study medication by courier service. The courier service would collect the medicinal products at the trial site, from the investigator who is responsible for the investigational medicinal products and this fact would be recorded by the investigator in the trial subject's documentation. The courier service would deliver the study medication to the patient's (= trial subject's) home, i.e. to the address provided by the investigator to the courier service. Thereafter, the investigator would make sure by phone that the patient has received the study medication and would record this fact to the trial subject's documentation.” g |

| (Denmark) Lægemiddelstyrelsen (Danish Medicines Agency) | 18.03.20 | “Temporary option to distribute directly to clinical trial subjects (temporary exemption from § 23 (2), of the GDP executive order because of COVID‐19): We acknowledge that clinical trials may experience acute IMP shortages caused by COVID‐19 related quarantines and cancellations of on‐site visits. Considering these highly unusual circumstances, we have decided upon a temporary possibility for sponsors to distribute trial medicine directly to the trial subjects without involving the investigator or hospital pharmacies. This temporary option is valid until 17 June 2020. We will assess whether an extension is needed two weeks before expiry. … The Danish Medicines Agency Q&A guidelines on supplying trial medicine directly to trial subjects (within the section ‘virtual/telemedicine trials’) must be followed to the greatest extent possible with patient safety as utmost priority.” h |

| (Republic of Estonia) Ravimiamet (State Agency of Medicines) | 07.10.20 | “Direct supply to patient of IMP/NIMP (sponsor to subject): Under exceptional conditions, having exhausted all other options, with every measure taken to ensure that the subjects' personal data are protected and that blinding procedures remain intact, under the supervision of the principal investigator and with proper documentation of the responsibilities of all parties involved (e.g. SOP, contract between the courier and the sponsor), direct shipments of IMP/NIMP from the sponsor to trial subjects may be allowed. The sponsor must apply for a substantial amendment where they must describe: Shipping arrangements, means of re‐consenting the subjects, measures of protecting the subjects' personal data from the sponsor (i.e. address, contact details), measures of ensuring that the blind remains intact (if applicable).” i |

|

(Finland) Lääkealan turvallisuus‐ ja kehittämiskeskus Fimea (Finnish Medicines Agency) |

19.03.20 | “As the epidemic worsens, exceptional arrangements may have to be made for the delivery of the investigational medicinal products to the patient (e.g. delivery to the home address instead of handing over the medicinal products during subjects' visits to the research location). In such cases, these exceptional arrangements must be essential for ensuring the continuation of the study, the safety of the subjects and the reliability of the research results. The sponsor must notify Fimea of any exceptional arrangements as soon as possible and submit the protocol amendment. Fimea will prioritise the evaluation of these amendments. Delivery of investigational medicinal products from the sponsor directly to the subject is not in accordance with Finnish law.” j |

| (France) ANSM Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé (National Agency for the Safety of Medicine and Health Products) | ‐ |

ANSM website searched January 2021 for relevant guidance, none located. k |

| (Germany) Paul‐Ehrlich‐Institut (Federal Institute for Vaccines and Biomedicines) c | 26.05.20 | “In view of the impact of the pandemic on European healthcare systems, the European authorities published a guidance document on 20 March 2020 that provides sponsors with recommendations regarding clinical trials and the persons involved in them. This guidance document was revised again, adopted on 28 April and published as version 3 both in the collection of laws of the European Commission (Eudralex, Volume 10) 2 and on the homepage of the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The guideline is a harmonised package of recommendations at EU level, which was co‐developed and co‐adopted by Germany. Some recommendations require closer consideration and interpretation, also with regard to the German legal area. These include, in particular, temporarily applicable measures for source data verification, if on‐site monitoring at the trial sites is not indicated due to the coronavirus pandemic.” l |

| (Greece) Ο Εθνικός Οργανισμός Φαρμάκων (The National Organisation for Medicines) | 13.05.20 | “The possibility of sending a research drug directly from the sponsor to the participating patient “direct from sponsor to trial participant” is not acceptable in Greece and can only be made possible by amending relevant national legislation. Direct sending of YEFP from the centre … It is pointed out that such a direct shipment from the centre can be done only when YEFP can be taken at home. Identification information and addresses of participants should not be disclosed off‐centre in addition to the necessary accompanying documents of its direct dispatch.” m |

| (Hungary) Országos Gyógyszerészeti és Elelmezés‐egészségügyi Intézet (The National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition) | 04.06.20 | “Questions and Answers on Regulatory Expectations for Medicinal Products for Human Use during the COVID‐19 Epidemic, 4 June 2020.” Document not available in the English language. n |

| (Ireland) An tÚdarás Rialála Táirgí Sláinte (The Health Products Regulatory Authority) | 04.12.20 | “The supply of IMP from sponsor contracted distributor directly to subjects is not currently considered acceptable. The allocation of IMP is the responsibility of the investigator (ref: ICH GCP E6 4.6). As outlined under the investigator and site staff considerations section of this guidance (point A.4), the supply of IMP from the investigator site to the subject's home via a delivery service may be considered, and the sponsor may provide assistance and advice to the investigator in relation to this.” o |

|

(Italy) AIFA Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (Italian Medicines Agency) |

17.09.20 | “The conduct of clinical trials must be managed according to common sense principles, with the utmost protection of study participants and maintaining adequate supervision by the principal investigators (PIs). To this end, please consult the Guidance on the Management of Clinical Trials during the COVID‐19 (coronavirus) pandemic published on the European Commission website, EudraLex Volume 10 Clinical trials (https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/eudralex/vol‐10_en).” p |

| (Latvia) Zāļu valsts aǵentūra ff (State Agency of Medicines of the Republic of Latvia) | 11.06.20 | “Until the end of this year (2020), general pharmacies will have the opportunity to deliver medicines to people at home, including by attracting volunteers. This is not a mandatory obligation for pharmacies, but an opportunity to meet people who do not have the opportunity to go to the pharmacy themselves or ask others to do so, for example, if a person is isolated at home due to Covid‐19 informs the Ministry of Health.” A legislative amendment to the domestic laws enabled this to happen in Latvia. q |

| (Lithuania) Valstybinė Vaistų Kontrolės Tarnyba (State Medicines Control Agency) | 08.07.20 | “In exceptional cases, if it is not possible to deliver the TVP (IMP) to the patient from the study centre (e.g. the research centre is temporarily unavailable due to quarantine), the possibility of sending the TVP to the patient's home directly from a contracted contractor may be considered. In this case, the written consent of the patient must be obtained. The supplier must keep the patient's personal data for no longer than is necessary for the TVP sending process. Once the potential risk has been assessed, the possibility of providing TVD directly to patients should not be considered in early‐phase clinical trials where it is necessary to ensure that patients are monitored, including when initiating TVP. This option should not be considered until the patient has gained sufficient experience with TVP.” r |

| (Luxembourg) SANTE (Ministère de la Santé) (SANTE Ministry of Health) | ‐ | SANTE website searched January 2021 for relevant guidance, none located. s |

| (Malta) Awtorità tal‐mediċini ta ‘Malta (Malta Medicines Authority) | ‐ | Malta Medicines Authority webpage website searched January 2021 for relevant guidance, none located. t |

| (Netherlands) Centrale commissie met onderzoek naar mensen (Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects) | 25.08.20 | “During the COVID‐19 situation, the IGJ allows: – IMP to be sent by courier from the (hospital) pharmacy to the trial participant; − IMP to be sent from the hospital pharmacy to the public pharmacy. Please refer to additional information on the website of IGJ (Health and Youthcare Inspectorate); − verbal consent by trial participants to use personal information necessary for sending IMP. The obtained verbal consent should be documented and, if possible, be confirmed by the trial participant via e‐mail; there is no requirement to obtain written consent retrospectively. The IGJ emphasises that shipment of IMP by the sponsor to the trial participant is not allowed.” u |

| (Norway) Statens legemiddelverk (Norwegian Medicines Agency) | 20.05.20 |

“Yes, the Norwegian Medicines Agency (NoMA) considers the sending of study drugs to the patient's home acceptable. Study drugs must be acquired using standard routines by the principal investigator or by the study physician who has been delegated this task. The study drugs must be delivered directly to the patient, at their place of residence. They cannot be left in the patient's letterbox. All individual deliveries of the study drug must be documented.” “The covid‐19 situation may present additional challenges when conducting clinical trials in accordance with the approved protocol. The sponsor will need to make a risk assessment (see ICH‐GCP, section 5) for changes that are deemed as necessary … the direct shipping (from outside of Norway) of study drugs from the sponsor to the patient's address is not acceptable. For further information, please see guidance document “Guidance on the Management of Clinical Trials during the COVID‐19 (coronavirus) pandemic (Version 3, 28/04/2020), section 9 (Changes in the distribution of the investigational medicinal products). Import of medicinal products for clinical studies in Norway may only be performed by a company which has the necessary authorisation. For this reason it is not possible to send study drugs from abroad directly home to the patient.” v |

| (Poland) Urząd Rejestracji Produktów Leczniczych, Wyrobów Medycznych i Produktów Biobójczych (Office for Registration of Medicinal Products, Medical Devices and Biocidal Products) | 15.04.20 | “The document explains the possibility of applying a certain ‘flexibility’ to regulatory issues (regulatory flexibilities) to help pharmaceutical companies deal with the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, while ensuring a high level or quality, safety and efficacy of medicinal products for patients in the European Union. The document published by the European Commission identified areas where regulatory flexibility is possible to address some of the restrictions that MAHs may face in the context of COVID‐19.” w |

| (Portugal) Autoridade Nacional do Medicamento e Produtos de Saúde (National Authority of Medicines and Health Products) | ‐ | INFARMED website searched January 2021 for relevant guidance, none located. x |

| (Romania) Agenţia Naţionalǎ a Medicamentului și a Dispozitivelor Medicale din România ff (National Authority of Medicines and Medical Devices) |

23.03.20 25.03.20 |

Domestic legislation was enacted to bring in emergency measures for 14 days from 24 March 2020. “In all other non‐urgent situations, NAMMD strongly recommends: rescheduling visits or replacing them with telephone visits; identifying solutions for transmitting medication to the patient's home; remote monitoring; postponing the initiation of new clinical trials or new investigation centers.” y |