Abstract

Aim

Pharmacotherapy is the primary treatment strategy in major depression. However, two‐thirds of patients remain depressed after the initial antidepressant treatment. Augmented cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression in primary mental health care settings proved effective and cost‐effective. Although we reported the clinical effectiveness of augmented CBT in secondary mental health care, its cost‐effectiveness has not been evaluated. Therefore, we aimed to compare the cost‐effectiveness of augmented CBT adjunctive to treatment as usual (TAU) and TAU alone for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression at secondary mental health care settings.

Methods

We performed a cost‐effectiveness analysis at 64 weeks, alongside a randomized controlled trial involving 80 patients who sought depression treatment at a university hospital and psychiatric hospital (one each). The cost‐effectiveness was assessed by the incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio (ICER) that compared the difference in costs and quality‐adjusted life years, and other clinical scales, between the groups.

Results

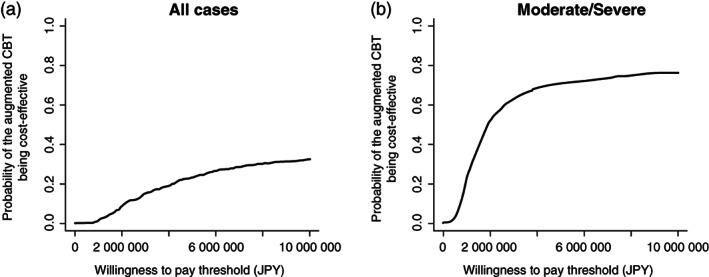

The ICERs were JPY −15 278 322 and 2 026 865 for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression for all samples and those with moderate/severe symptoms at baseline, respectively. The acceptability curve demonstrates a 0.221 and 0.701 probability of the augmented CBT being cost‐effective for all samples and moderate/severe depression, respectively, at the threshold of JPY 4.57 million (GBP 30 000). The sensitivity analysis supported the robustness of our results restricting for moderate/severe depression.

Conclusion

Augmented CBT for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression is not cost‐effective for all samples including mild depression. In contrast, it appeared to be cost‐effective for the patients currently manifesting moderate/severe symptoms under secondary mental health care.

Keywords: antidepressant, cognitive behavioral therapy, combination therapy, cost‐effectiveness, pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression

Pharmacotherapy is the recommended first‐line treatment for depression. However, several patients demonstrate an inadequate response to the initial treatment. Only one‐third of the patients remit with initial antidepressants, and nearly half of them remain depressed following treatment with more than two antidepressants. 1 , 2 , 3

The aforementioned chronic course of depression places a huge burden on society. The 2015 global burden of disease study revealed that severe depression accounts for 2.54% of global disability‐adjusted life years, and is the leading disorder among all mental and behavioral disorders. 4 The impact becomes more obvious when the burden gets translated into monetary costs. The depression‐mediated societal cost was USD 83.1 billion in the United States in 2000, 5 GBP 9.1 billion in the UK in 2000, 6 and JPY 2.0 trillion in Japan in 2005. 7 Investigators have sought an optimized strategy for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression to reduce its burden. Wiles et al. 8 reported the efficacy and cost‐effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) plus treatment as usual (TAU) (augmented CBT) for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression in a primary care setting. Moreover, we reported on the clinical effectiveness of augmented CBT over TAU alone, both at 16 weeks and 12 months post‐treatment. 9 However, its cost‐effectiveness has not yet been evaluated. Therefore, we aimed to present the findings, focusing primarily on the cost‐effectiveness of augmented CBT. We intended to determine if augmented CBT adjunctive to TAU has greater cost‐effectiveness than TAU alone for patients with pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression in secondary mental health care settings.

Methods

We performed this cost‐effectiveness analysis alongside a randomized controlled trial (RCT) on the effectiveness of augmented CBT, compared to TAU at secondary mental health care settings in Japan. The complete study design is described in the article on the RCT protocol. 10 This study was approved by the ethics review committee of Keio University School of Medicine and the ethical committee of the Sakuragaoka memorial hospital. The study was conducted and reported in accordance with the consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) guidelines (Supplementary File S1) 11 , 12 and consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) guidelines (Supplementary File S2). 13

Setting

The participants were recruited from two outpatient clinics in Tokyo, namely a university hospital and a psychiatric hospital.

Participants

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age 20 to 65 years, (ii) had DSM‐IV major depressive disorder (MDD), 14 (iii) had single or recurrent episodes, and (iv) no psychotic features identified by the DSM‐IV‐TR Axis I Disorders‐Patient Edition. 15 Additionally, all participants confirmed the operational criteria of at least a minimal degree of treatment‐resistant depression (Maudsley Staging Method for treatment‐resistant depression score 16 ≥3) and the 17‐item GRID‐Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (GRID‐HDRS17) 17 , 18 score ≥16, despite treatment with adequate therapeutic levels of antidepressants for at least 8 weeks. 16 The detailed method of assessing the degree of pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression has been described in the companion article. 9 The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) a primary DSM‐IV Axis 1 diagnosis other than MDD, (ii) manic or psychotic episodes, (iii) alcohol or substance use disorder or antisocial personality disorder, (iv) serious and exigent suicidal ideation, (v) organic brain lesions or major cognitive deficits, and (vi) serious or unstable medical illness. Moreover, we excluded those who (vii) underwent CBT previously (i.e., eight or more sessions), and (viii) were unlikely to participate in eight or more sessions of treatment (for reasons such as planned relocation). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the data obtained from them were anonymized.

Design

We conducted a pragmatic, multicenter, assessor‐blinded 16‐week RCT, followed by a 12‐month follow‐up with a nested cost‐effectiveness analysis. The participants were randomized (1:1 ratio) to either group, namely the augmented CBT (i.e., CBT plus TAU) or TAU alone, using a web‐based random allocation system to conceal the allocation. Random allocation was independently performed by the Keio Center for Clinical Research Project Management Office, Tokyo, Japan. Randomization was stratified by the study site using the minimization method to balance the age of the participants at entry (<40 years, ≥40 years) and baseline GRID‐HDRS17 scores (16–18, ≥19). Considering the nature of the interventions, we could neither mask the participants nor the treating psychiatrists or therapists to the randomization status. Nonetheless, the outcome assessors were blinded to the allocation to the maximum extent possible. We requested the participants to not indicate their allocated interventions during assessment interviews. The assessors were independent of the treatment provision or study coordination and were forbidden from accessing any allocation‐related information. We evaluated the success of masking by randomly conducting one‐third of the primary outcome interviews with the assessors, by inquiring the group to which the assessed patient was allocated. Considering the probability of agreement and κ coefficients were 0.520 and 0.00 (95% CI, −0.39 to 0.39), respectively, the masking was successful. We estimated the sample size based on the power required to detect clinical differences between the groups. Therefore, it was not calculated on the basis of costs or cost‐effectiveness.

Therapy intervention

Cognitive‐behavioral therapy

Participants allocated to the augmented CBT arm underwent 16 individual weekly CBT sessions, for 50 min each. They underwent up to four additional sessions if judged clinically appropriate by the therapist. The sessions were conducted following the CBT Manual for Depression, 19 developed by the authors (Y.O., D.F., A.N., M.S., and T.K.). It is based on Beck's manual with some adjustments to include the cultural characteristics of Japanese patients.

The therapists offering CBT included four psychiatrists, one clinical psychologist, and one psychiatric nurse. On average, they had practiced CBT for a mean (SD) of 4.0 (2.1) years and had an experience of providing CBT to 12.5 (7.3) patients before the study. All received CBT training, such as a 2‐day intensive workshop by weekly group supervision, led by a senior CBT supervisor (Y.O.). The senior clinician, independent of the study, rated one‐fourth of the audio recorded sessions (10 sessions), mostly in the tenth session, with the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTRS). 20 This helped ascertain whether the therapists were skilled enough to offer CBT and adhered to the CBT manuals. All therapists were judged competent, as reflected by their CTRS scores ≥40. The participants received standard care, similar to patients not enrolled in the study.

Treatment as usual

The TAU included pharmacotherapy, monitoring adverse events, and brief supporting care from a specialized psychiatrist. There were no specific restrictions on pharmacotherapy, including the type of medication or dosage. However, specific psychotherapies, such as CBT, interpersonal therapy, or psychodynamic psychotherapy were prohibited during the study. The 16‐item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self‐Report (QIDS‐SR) was used to monitor depressive symptoms at each visit. 21 , 22 The patients visited the psychiatrists every 2 weeks, and each visit took approximately 10–15 min. Seven psychiatrists, who took charge of the TAU, practiced at a psychiatric specialty care center for a mean (SD) of 7.3 (4.4) years. According to the Statistics of medical care activities in public health insurance, 23 because it is quite rare that other specific psychotherapies are offered to patients with depression (i.e. 0.27% among psychiatrists visit), we judged that the aforementioned TAU definition would be reasonable.

Outcome measures

The assessments were conducted at six time points as follows: baseline (at randomization), 8‐ and 16‐week post‐randomization, and 3, 6, and 12 months following the 16‐week intervention. The primary outcome was the mean difference of the change in the total GRID‐HDRS17 score between the groups from baseline to 16 weeks.

GRID‐HDRS17, 24 a revision of the original Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 17 , 18 provides a standardized, explicit scoring method and a structured interview guide for the administration and scoring. All raters had extensive training in GRID‐HDRS17. Moreover, the inter‐rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient) ranged from 0.94–0.98, indicating excellent agreement.

The secondary outcomes were assessed at the aforementioned time points. They included treatment response (≥50% reduction from the baseline GRID‐HDRS17 score), remission (GRID‐HDRS17 score ≤7), self‐reported depressive symptom measures [Beck Depression Inventory‐II (BDI‐II) 25 , 26 and QIDS‐SR scores], and the quality of life, as measured by summary scores for mental and physical components of the 36‐item Short‐Term Health Survey (SF‐36). 27 , 28 Additionally, the participants completed the Japanese version of the European Quality of Life Questionnaire‐5 Dimensions (EQ‐5D) 29 , 30 for economic evaluation.

We monitored the adverse events. Death, life‐threatening events, events leading to severe disability or functional impairment, and hospitalization are recognized as severe adverse events.

Health service use

Data on healthcare service use were collected using a clinical record format. At each visit, the psychiatrists or CBT therapists checked the service use since the previous visit. The costs of medications, psychiatrist visits, and CBT were included in the analysis. The costs are presented in Japanese yen (JPY) and US dollars (USD). ICER thresholds are presented in UK pounds (GBP). We converted the costs in JPY to USD and GBP based on the purchasing power parity in 2014 (i.e., the year in the middle of the study period: one JPY was equal to 107.45 USD and 152.19 GBP). 31 The details for assessing each cost component were as follows:

Medication costs

Medication costs include the price of medicines and dispensing costs. The psychotropics were divided into four categories: antidepressants, anxiolytics/hypnotics, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers. The daily dose of each drug was expressed as a fraction of the defined daily dose (DDD), regulated by the World Health Organization, the assumed average maintenance dose per day for adults calculated from the dosage recommendations for each drug. 32 This helped us calculate the standardized cost adjusting cost differences among different drugs in the same category (e.g., paroxetine and sertraline in the antidepressant category). Subsequently, we estimated the cost of each drug based on the following formula:

where C med‐n‐d , D n , DDD n , and C med‐c represent the cost of medicine n at a dose d, the dose of the prescribed medicine n, DDD of the medicine n, and the weighted cost of the category C to which the medicine n belongs.

We estimated the mean weighted daily medication cost per DDD for each drug category based on previous studies and government reports. 9 , 32 , 33 , 34 The results and methodology used to estimate them are provided in Table 1 and Table S1‐a to 1‐e.

Table 1.

Unit cost of each healthcare service

| Unit cost (JPY) | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| General consultant fee (per visit) | 720 | MHLW of Japan 28 |

| Psychiatric management fee (per visit) | 3 300 | MHLW of Japan 28 |

| Prescription fee (per prescription) | 1 190 | MHLW of Japan 28 |

| CBT (per session) | 4 800 | MHLW of Japan 28 |

| CBT (per session) (in sensitivity analysis) | 11 110 | Hollinghurst et al. 32 |

| Mean weighted daily cost per DDD of each drug category † | ||

| Antidepressants | 142.3 | Nakagawa et al., 29 MHLW of Japan, 28 WHO 27 |

| Anxiolytics/hypnotics | 37.1 | Nakagawa et al., 29 MHLW of Japan, 28 WHO 27 |

| Antipsychotics | 389.7 | Nakagawa et al., 9 MHLW of Japan, 28 WHO 27 |

| Mood stabilizer | 217.5 | Nakagawa et al., 9 MHLW of Japan, 28 WHO 27 |

For the method to calculate the mean weighted cost per DDD per day of drug category, please refer to Table S1.

CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; DDD, Defined Daily Dose; MHLW, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

We calculated the total medication costs by summing the area of the five trapezoids, squared by the daily medication costs and the duration between the assessments.

Psychiatric visit fee

The psychiatric visit fees included general consultant fees, psychiatric management fees, and prescription fees (Table 1). Each unit cost data was derived from the government regulated prices. 33

CBT costs

The unit cost of CBT was set as JPY 4800, the official government‐regulated reimbursement rate (Table 1). 33

Cost‐effectiveness

The cost‐effectiveness was evaluated by the incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios (ICERs), defined as the incremental costs divided by the incremental effectiveness, primarily measured as quality‐adjusted life years (QALYs). The QALYs were derived by estimating the area under the curve of the EQ‐5D‐measured health‐related utilities (at baseline, 8 weeks, 16 weeks post‐randomization, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months post‐intervention). 35 The EQ5D scores were weighted to estimate health‐related utilities based on the value set of the Japanese version of the EQ‐5D. 36 ICER, as per other clinical scales (i.e., GRID‐HDRS17, BDI‐II, and QIDS‐SR), was also estimated as the secondary outcome. We estimated the ICERs at 12 months post‐intervention. The analysis was conducted from a health insurance perspective. The discount rate was not considered because of the short observational period (16 months).

Statistical analyses

Cost‐effectiveness was analyzed only with complete samples in the base‐case analysis because the QALYs require health‐related utility scores at every point. It was the same for cost‐effectiveness analysis with other clinical scales. No imputation was performed. We also performed a sub‐group analysis focusing on the samples with moderate and severe depression, as augmented CBT is recommended for moderate or severe depression, and not for mild depression. 37 The cut‐off points differentiating mild depression from moderate/severe ones were set as 18/19 baseline GRID‐HDRS17 score, according to the classification by The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (subthreshold: 8–13, mild: 14–18, moderate: 19–22, and severe: 23+), 38 same as that used for stratification during randomization for this study.

We used the ICER to assess the cost‐effectiveness of augmented CBT. The mean and standard error of incremental costs and effectiveness were calculated by resampling 1000 from the original samples, using the non‐parametric bootstrap method. Cost‐effectiveness acceptability curves were drawn to provide information for wider clinical and political decision‐making. The aforementioned curves demonstrate the probability of augmented CBT being cost‐effective than TAU alone, in a range of hypothetical values placed on incremental outcome improvements [willingness to pay (WTP) by the decision‐makers in the health and social care system]. The cost‐effectiveness acceptability curves were based on the net monetary benefit approach, defined as:

where λ is the WTP for one unit of additional improvement in the outcome measure (QALYs), and ΔE and ΔC denote the difference in effectiveness and cost, respectively, between the two arms.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed three one‐way sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the cost‐effectiveness‐related results with QALYs. The first analysis was related to the impact of the cost assumption, while the second was related to the QALYs, the final analysis incorporated both QALYs and costs. We performed the first analysis with the different unit cost of CBT {i.e., JPY 11 110 [equivalent to unit cost of CBT adopted in the relevant study in UK (i.e., GBP 73) 31 , 39 ]}. In the second analysis, we assessed the effect of the analysis on all samples, with an imputation of the last observation carried forward (LOCF) to ascertain the effect of missing data. Finally, we analyzed with all samples of different unit costs of CBT, similar to the first sensitivity analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R (4.0.2).

Results

Participants

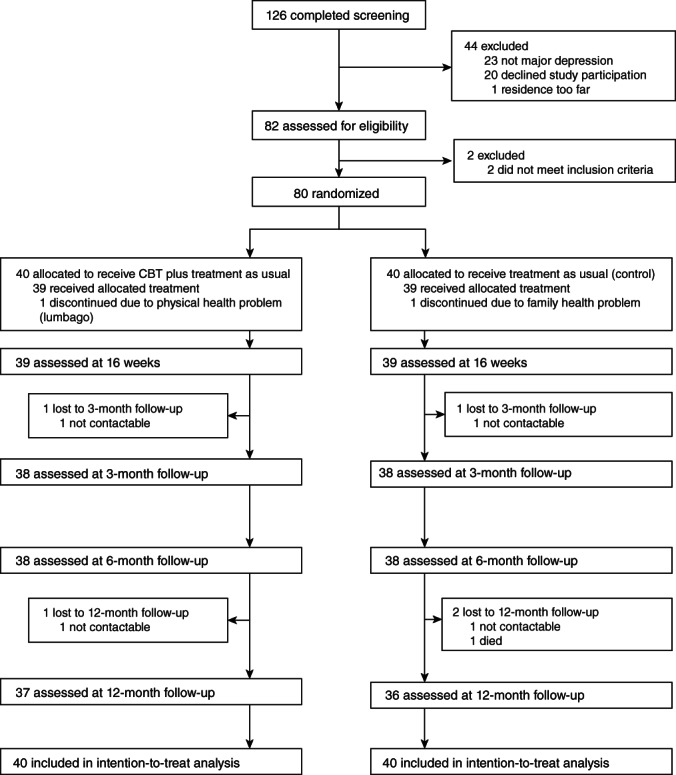

Between 20 September 2008 and 19 August 2013, we screened 126 participants, and the final 12‐month follow‐up was performed on 26 December 2014. Among them, 80 met the inclusion criteria and were randomized either to CBT plus TAU (n = 40) or TAU alone (n = 40) (Fig. 1). The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at the pre‐treatment were described in the original article. 9 The mean duration of index depression episodes exceeded 30 months, and over 70% of participants had moderate or severe depression in the severity of treatment resistance, represented by the Maudsley Staging Method score. Fifty participants (62.5%) had received more than three courses of antidepressants before the study.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the study.

Treatment engagement and health service use

With respect to treatment engagement, all participants except one completed the entire CBT course in the augmented CBT group. There was no significant difference in the psychiatrist visits between the groups. The dose of all drug categories did not statistically differ between the treatment arms at any point in the study, except anxiolytics/hypnotics at week 40 (Table 2). None of the participants had serious adverse events during the intervention period. However, during the follow‐up period, two patients in the TAU group were admitted to the hospital due to aggravated depression. One of them committed suicide shortly after discharge from the psychiatric ward, which was 10 months after the end of the intervention period. The missing data rate in the EQ‐5D was 4.2%.

Table 2.

Treatment engagement by study group

| CBT (n = 40) | TAU (n = 40) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of CBT sessions attended, mean (SD) | 15.1 (3.5) | ||

| Completion rate of the full course of CBT sessions, n (%) | 39 (97.5) | ||

| Length of CBT sessions, mean (SD), min | 47.9 (4.5) | ||

| No. of psychiatrists visit, mean (SD) | |||

| Between baseline and 16 weeks (acute 16‐week phase) | 12.0 (2.9) | 10.9 (2.9) | 0.10 |

| Between 16 and 28 weeks (from end point to 3‐month follow‐up) | 4.8 (3.4) | 5.7 (3.3) | 0.21 |

| Between 28 and 40 weeks (from 3‐ to 6‐month follow‐up) | 4.6 (2.6) | 3.8 (2.8) | 0.16 |

| Between 40 and 64 weeks (from 6‐ to 12‐month follow‐up) | 7.2 (4.3) | 6.1 (5.1) | 0.34 |

| Medication | |||

| Antidepressants dose (DDD) at each time point, mean (SD), week | |||

| 0 (baseline) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) | 0.43 |

| 16 | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.9) | 0.30 |

| 28 (3‐month follow‐up) | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.18 |

| 40 (6‐month follow‐up) | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.0 (0.8) | 0.15 |

| 64 (12‐month follow‐up) | 1.1 (1.0) | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.47 |

| Anxiolytics/hypnotics dose (DDD) at each time point, mean (SD), week | |||

| 0 (baseline) | 1.7 (1.6) | 1.4 (1.2) | 0.27 |

| 16 | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.4) | 0.26 |

| 28 (3‐month follow‐up) | 1.6 (1.5) | 1.0 (1.3) | 0.06 |

| 40 (6‐month follow‐up) | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.03 |

| 64 (12‐month follow‐up) | 1.3 (1.5) | 1.0 (1.3) | 0.32 |

| Antipsychotics dose (DDD) at each time point, mean (SD), week | |||

| 0 (baseline) | 0.04 (0.12) | 0.13 (0.27) | 0.07 |

| 16 | 0.08 (0.24) | 0.10 (0.24) | 0.72 |

| 28 (3‐month follow‐up) | 0.06 (0.20) | 0.12 (0.27) | 0.34 |

| 40 (6‐month follow‐up) | 0.09 (0.26) | 0.12 (0.28) | 0.68 |

| 64 (12‐month follow‐up) | 0.11 (0.28) | 0.11 (0.28) | 0.91 |

| Mood stabilizer dose (DDD) at each time point, mean (SD), week | |||

| 0 (baseline) | 0.04 (0.15) | 0.06 (0.18) | 0.68 |

| 16 | 0.05 (0.15) | 0.07 (0.22) | 0.56 |

| 28 (3‐month follow‐up) | 0.05 (0.14) | 0.07 (0.16) | 0.53 |

| 40 (6‐month follow‐up) | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.08 (0.16) | 0.18 |

| 64 (12‐month follow‐up) | 0.03 (0.14) | 0.06 (0.16) | 0.40 |

P values are for t‐test.

This is the intention‐to‐treat‐analysis.

CBT, cognitive‐behavioral therapy; DDD, defined daily dose; TAU, treatment as usual.

Cost consequences

Table 3 summarizes the mean cost and clinical outcomes. Among all samples, the total cost was significantly higher, by JPY 96 726, in the augmented CBT group than in the TAU alone group. With respect to patients with moderate/severe depression, the augmented CBT group incurred lower medication costs. Nonetheless, the total cost increased by JPY 64 786, primarily because of the additional CBT costs. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups.

Table 3.

Cost consequence analysis

| All patients (n = 80) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–16 weeks | 17–64 weeks | ||||

| Cost | CBT (n = 40) | TAU (n = 40) | CBT (n = 40) | TAU (n = 40) | Difference over an entire period (95% CI) |

| Visit Cost | |||||

| JPY | 66 948 (16 115) | 57 050 (15 381) | 81 927 (45 634) | 81 016 (53 026) | 10 811 (−15 445 to 37 066) |

| USD | 623 (150) | 531 (143) | 762 (425) | 754 (493) | 101 (−144 to 345) |

| Drug Cost | |||||

| JPY | 33 166 (18 343) | 31 794 (18 621) | 92 878 (64 904) | 80 814 (62 465) | 13 436 (−22 288 to 49 159) |

| USD | 309 (171) | 296 (173) | 864 (604) | 752 (581) | 125 (−207 to 457) |

| CBT Cost | |||||

| JPY | 57 480 (14 193) | 0 (0) | 15 000 (11 042) | 0 (0) | 72 480 (67 215 to 77 745) |

| USD | 535 (132) | 0 (0) | 140 (103) | 0 (0) | 675 (626 to 724) |

| Total | |||||

| JPY | 157 595 (41 072) | 88 844 (26 595) | 189 805 (93 316) | 161 830 (100 143) | 96 726 (41 238 to 152 215) |

| USD | 1467 (382) | 827 (248) | 1766 (868) | 1506 (932) | 900 (384 to 1417) |

| Effectiveness † | Week 16 | Week 64 | Difference over an entire period (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT (n = 40) | TAU (n = 40) | CBT (n = 40) | TAU (n = 40) | ||

| Change of HAMD (n = 80) | −12.72 (0.90) | −7.39 (0.90) | −15.25 (1.14) | −10.74 (1.15) | −4.506 (−7.672 to −1.339) |

| Change of EQ‐5D (n = 79) | 0.070 (0.028) | 0.074 (0.028) | 0.131 (0.028) | 0.139 (0.028) | −0.009 (−0.085 to 0.068) |

| Moderate/Severe patients (n = 54) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0‐16 weeks | 17–64 weeks | ||||

| Cost | CBT (n = 40) | TAU (n = 40) | CBT (n = 40) | TAU (n = 40) | Difference over an entire period (95% CI) |

| Visit Cost | |||||

| JPY | 68 695 (16 541) | 62 327 (12 801) | 87 219 (52 332) | 93 394 (55 155) | 193 (−33 761 to 34 147) |

| USD | 639 (154) | 580 (119) | 812 (487) | 869 (513) | 2 (−314 to 318) |

| Drug Cost | |||||

| JPY | 33 912 (19 066) | 36 410 (19 077) | 93 181 (63 807) | 100 224 (62 057) | −9541 (−53 166 to 34 085) |

| USD | 316 (177) | 339 (178) | 867 (594) | 933 (578) | −89 (−495 to 317) |

| CBT Cost | |||||

| JPY | 59 200 (15 120) | 0 (0) | 14 933 (11 322) | 0 (0) | 74 133 (67 503 to 80 764) |

| USD | 551 (141) | 0 (0) | 139 (105) | 0 (0) | 690 (628 to 752) |

| Total | |||||

| JPY | 161 807 (42 917) | 98 737 (21 183) | 195 334 (100 204) | 193 618 (96 958) | 64 786 (−3186 to 132 758) |

| USD | 1506 (399) | 919 (197) | 1818 (933) | 1802 (902) | 603 (−30 to 1235) |

| Effectiveness † | Week 16 | Week 64 | Difference over an entire period (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT (n = 40) | TAU (n = 40) | CBT (n = 40) | TAU (n = 40) | ||

| Change of HAMD (n = 80) | −13.87 (1.20) | −8.47 (1.18) | −16.88 (1.59) | −11.45 (1.54) | −5.434 (−9.781 to −1.086) |

| Change of EQ‐5D (n = 79) | 0.095 (0.038) | 0.075 (0.037) | 0.176 (0.039) | 0.144 (0.037) | 0.032 (−0.073 to 0.137) |

Results of a mixed‐effects model for repeated measures.

Values are means and standard deviation unless stated otherwise.

CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; CI, confidence intervals; JPY, Japanese yen; TAU, treatment as usual; USD, United States dollars.

Despite a difference of 4.51 in GRID‐HDRS17 between the groups, the difference in the EQ‐5D score was negative (−0.009) in all samples. In contrast, patients with moderate/severe depression in the intervention group scored 5.43 points less (i.e., less depressed) on the GRID‐HDRS17, and enjoyed better health‐related utility than the control group at 12 months post‐intervention, measured by the EQ‐5D (0.032). Both results for the GRID‐HDRS17 were statistically significant. However, results on the EQ‐5D were insignificant.

Cost‐effectiveness

Table 4 summarizes the results of the base‐case cost‐effectiveness analysis. The ICER was negative (JPY −15 278 322) in all samples (n = 73: augmented CBT 37 vs TAU 36), considering the incremental cost of JPY 97 297 and the negative incremental QALYs (−0.006) in the intervention group. The probability of the augmented CBT being cost‐effective was 0.221 at a WTP of JPY 4 565 710 (GBP 30 000) (Fig. 2a). The respective ICERs for HDRS‐17, BDI‐II, and QIDS‐SR became JPY 21 844/HDRS, JPY −178 788/BDI‐II, and JPY −751 905/QIDS‐SR (Table 5).

Table 4.

Cost effectiveness analysis in base case

| Mean differences (95% CI) and ICERs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | All patients (n = 73: CBT 37 vs TAU 36) | Moderate/severe patients (n = 50: CBT 24 vs TAU 26) | |

| Incremental costs | (JPY) | 97 297 (43 818 to 149 761) | 84 315 (28 718 to 144 589) |

| (USD) | 905 (408 to 1394) | 785 (267 to 1346) | |

| Incremental QALY gain | −0.006 (−0.077 to 0.065) | 0.042 (−0.049 to 0.126) | |

| ICER | (JPY per QALY) | −15 278 322 | 2 026 865 |

| (USD per QALY) | −142 184 | 18 863 | |

These values were estimated in complete samples.

CI, confidence intervals; ICER, Incremental cost effectiveness ratio; JPY, Japanese yen; QALY, quality adjusted life years; USD, United States dollars.

Fig. 2.

Cost effectiveness acceptability curves of the base‐case analysis with (a) all samples, and (b) the patients with moderate/severe depression.

Table 5.

Cost effectiveness analysis in base case (with clinical outcomes)

| Mean differences (95% CI) and ICERs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | All patients (n = 73: CBT 37 vs TAU 36) | Moderate/severe patients (n = 50: CBT 24 vs TAU 26) | |

| Incremental costs | (JPY) | 97 297 (43 818 to 149 761) | 84 315 (28 718 to 144 589) |

| (USD) | 905 (408 to 1394) | 785 (267 to 1346) | |

| Incremental GRID‐HDRS17 gain | 4.45 (1.16 to 7.7) | 5.91 (1.51 to 10.05) | |

| ICER | (JPY per GRID‐HDRS17) | 21 844 | 14 262 |

| (USD per GRID‐HDRS17) | 203 | 133 | |

| Incremental BDI‐II gain | −0.54 (−5.65 to 4.58) | 3.61 (−2.75 to 10.43) | |

| ICER | (JPY per BDI‐II) | −178 788 | 23 347 |

| (USD per BDI‐II) | −1664 | 217 | |

| Incremental QIDS gain | −0.13 (−2.66 to 2.61) | 2.33 (−0.77 to 5.66) | |

| ICER | (JPY per QIDS‐SR) | −751 905 | 36 166 |

| (USD per QIDS‐SR) | −6997 | 337 | |

These values were estimated in complete samples.

BDI‐II, Beck Depression Inventory‐II; CI, confidence intervals; GRID‐HDRS17, the 17‐item GRID‐Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; ICER, Incremental cost effectiveness ratio; JPY, Japanese yen; QIDS‐SR, The 16‐item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self‐Report; USD, United States dollars.

The results of the sub‐group analysis revealed that patients with moderate/severe depression (n = 50: augmented CBT 24 vs TAU 26) in the augmented CBT enjoyed better QALYs (an increase by 0.042). Additionally, the incremental cost was JPY 84 315. Therefore, the ICER was JPY 2 026 865, substantially below the threshold adopted in the UK (i.e., GBP 20 000–30 000 per QALY gained). The probability of the augmented CBT being cost‐effective was 0.701 at a WTP of JPY 4 565 710 (GBP 30 000) (Fig. 2b). The respective ICERs for GRID‐HDRS17, BDI‐II, and QIDS‐SR appeared to be JPY 14 262/GRID‐HDRS17, JPY 23 347/BDI‐II, and JPY 36 166/QIDS‐SR (Table 5). The acceptability curves are given in Figs [Link], [Link].

Sensitivity analysis

In the first scenario, while considering all patients, the ICER became negative (JPY −30 373 442) for a CBT unit cost of JPY 11 110 (Table S2). In contrast, the ICER for moderate/severe depression remained JPY 4 463 769, still below the NICE threshold. The acceptability curve depicts the probabilities of the augmented CBT being cost effective were 0.094 and 0.535 for all samples and moderate/severe depression, respectively, at a WTP of JPY 4 565 710 (GBP 30 000) (Fig. S4).

In scenario 2, we analyzed the samples, including those with missing values (n = 79: augmented CBT 40 vs TAU 39). LOCF was performed for imputation of the missing EQ‐5D scores (no imputation was performed for the cost). The incremental QALY improved to 0.005 while considering all samples, leading to a positive ICER (i.e., JPY 17 032 680). However, it was markedly beyond the threshold. However, augmented CBT appeared cost‐effective for moderate/severe depression (i.e., ICER: JPY 1 822 956) (Table S3). The augmented CBT was 36.2% and 69.3% cost‐effective for all samples and those with moderate/severe depression, respectively, at a WTP of JPY 4 565 710 (Fig. S5). The final sensitivity analysis with a CBT unit cost of JPY 11 110, including the samples with missing values, revealed that the ICERs were JPY 33 638 171 and JPY 4 223 761 for all participants and participants with moderate/severe depression, respectively (Table S4). The probability of the augmented CBT being cost‐effective was 0.173 and 0.537 for all participants and those with moderate/severe depression, respectively, at a WTP of JPY 4 565 710 (Fig. S6).

Discussion

Overall results

The analysis with all samples failed to provide sufficient evidence for the cost‐effectiveness of augmented CBT for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression. In contrast, augmented CBT was observed to be cost‐effective for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression, currently manifesting moderate/severe symptoms. As shown in Table 4, this discrepancy appeared to be mainly due to the difference of the incremental QALYs between all participants and participants with moderate/severe depression (−0.006 vs 0.042). The result for the moderate/severe depression appeared robust, considering that ICERs remained below the threshold for all hypotheses in all sensitivity analyses. Our findings are consistent with the NICE clinical guidelines, which recommend augmented CBT for moderate or severe depression. 40

Comparison with other studies

Limited studies have assessed the cost‐effectiveness of CBT adjunct to TAU for treatment‐resistant depression. 41 , 42 However, a large‐scale RCT by Wiles et al. 8 , 39 targeted 469 patients with treatment‐resistant depression in a primary care setting. The cost‐effectiveness analysis revealed that patients who received augmented CBT enjoyed better QALYs (0.057 higher) than those with usual care, with an incremental cost of GBP 850. Therefore, the ICERs resulted in GBP 14 911. The ICERs ranged between GBP 13 000 and 30 000 as a consequence of the sensitivity analysis, which were all below the NICE threshold (i.e., GBP 20 000 to 30 000). Our results are consistent with those of Wiles et al.ʼs study when targeting moderate/severe depression, considering the incremental QALYs were adequate (i.e., 0.042) and the sensitivity analysis generated robust results. However, they differed in that augmented CBT did not prove cost‐effective in all samples, including those with mild depression.

The difference in the severity of the study participants between the two trials might have caused the discrepancy. The mean BDI‐II score at baseline was 31.8 in the study conducted by Wiles et al. This is categorized as ‘moderate to severe’ by the NICE guideline. However, our study participants scored 27.4 (‘mild to moderate’). The baseline‐mean BDI‐II score increased to 29.6 among patients with moderate/severe depression, close to the score obtained by Wiles et al. Furthermore, the ICERs became relatively stable (i.e., all ICERs were below the threshold for any hypothesis in sensitivity analyses). Therefore, it seems reasonable to consider that the difference in the severity of the participants resulted in the discrepancy.

A comparison between the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness

Augmented CBT significantly improved depressive symptoms measured by the HDRS in all samples, including those with mild depression, as shown in the original article. However, it appeared cost‐effective only for moderate/severe depression.

Several factors might have contributed to this difference. The first is the difference in the nature of the scales. The HDRS is a specific scale to comprehensively assess depressive symptoms. In contrast, the EQ‐5D comprehensively assesses the quality of life of patients from five functional dimensions, namely mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Therefore, the responsiveness of the EQ‐5D to depressive symptoms should be restricted. This can be attributed to the relevance of only one dimension to mental health conditions such as anxiety/depression. 43 Mulhern et al. 44 compared the responsiveness of EQ‐5D with that of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) among 327 depressed patients and reported that EQ‐5D was less responsive than HADS. Crick et al. 43 compared the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder‐2 scores with those of EQ‐5D among 495 patients with diabetes. More than half of the patients with either improved or deteriorated symptoms revealed no change in the anxiety/depression dimension in EQ‐5D‐3L. The anxiety/depression dimension of the EQ‐5D‐3L demonstrated weak performance in the receiver operating characteristic analysis, with C‐indices ranging between 0.58–0.63. The aforementioned weak responsiveness in the EQ‐5D‐3L could explain the discrepancy between the clinical and cost‐effectiveness outcomes.

The EQ‐5D‐3L‐mediated ceiling effect also contributed to the discrepancy. The EQ‐5D‐3L has been associated with some concerns, such as the ceiling effect, reliability, and sensitivity (discriminatory power). 45 This necessitated the development of the 5‐level version of the EQ‐5D (EQ‐5D‐5L). Mulhern et al. 44 investigated the samples from an RCT 46 and demonstrated that EQ‐5D‐3L showed a larger ceiling effect compared to the HADS. This is similar to observations from a study in a Japanese setting, where Ninomiya et al. reported that EQ‐5D‐5L possibly reduces the ceiling effect. 47 In this study on the effectiveness of mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy in anxiety disorders, 20 patients simultaneously rated both EQ‐5D‐3L and EQ‐5D‐5L. Despite a high baseline score of EQ‐5D (0.80), the EQ‐5D‐5L detected a significant difference between the intervention group and control group post‐treatment. Nonetheless, there was no difference in the EQ‐5D‐3L scores.

We used the EQ‐5D‐3L as the EQ‐5D‐5L was unavailable at the beginning of the trial. The baseline EQ‐5D scores of the patients with moderate/severe depression was 0.647, and that of the patients with mild depression was relatively high (0.733). Therefore, the inclusion of patients with mild depression boosted the baseline EQ‐5D scores. This might have generated a ceiling effect, thus failing to detect adequate differences in the QALYs. As the EQ‐5D‐5L improves the ceiling effect, the difference might have been observed if we had been able to use the EQ‐5D‐5L instead.

Another possible explanation would be the differences between the clinician‐administered scale (i.e., HDRS) and self‐rated scale (i.e., EQ‐5D). Even among the clinical scales, we observed a discrepancy between the clinician‐rated scale (HDRS) and self‐rated scales (BDI‐II and QIDS‐SR). As discussed in the original article, 9 several possible factors may account for the discrepancy, such as lack of statistical power, clinician, or patient biases in describing symptomatology, evaluating different components of depressive symptomatology in respective scales. Such factors may have also affected the relationship between EQ‐5D and HDRS.

Clinical and policy implications

The application of augmented CBT to patients with pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression

We recommend augmented CBT for patients with pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression, currently manifesting moderate/severe symptoms. This is supported by both clinical and economic perspectives. Nonetheless, there is no indication to recommend augmented CBT for patients with mild depression from a cost‐effectiveness perspective. As the EQ‐5D‐3L‐mediated ceiling effect possibly affected the results, a more accurate analysis should be performed to draw conclusions, such as an analysis with the EQ‐5D‐5L.

The unit cost of CBT in Japan

The ICERs considerably differed for the Japanese and UK‐based unit cost of CBT. This is solely because of the difference in the unit cost between the two countries. Thus, the unit fee of the government‐regulated CBT in Japan was likely underestimated (i.e., 4 800 yen per session does not possibly represent the actual human capital cost to offer CBT sessions). Government statistics reported that only 0.06% of all patients under treatment for depression were offered CBT in 2012. 48 Among the various reasons for this (e.g., the shortage of skillful CBT therapists), the low reimbursement of CBT cost was very likely, discouraging incentives for the healthcare providers on providing CBT. Augmented CBT was cost‐effective for moderate/severe depression even with the UK‐based unit cost (i.e., JPY 11 110). Therefore, we should consider optimizing the CBT fee. This might enable the dissemination of CBT to the patients who require it.

Limitations

Despite adding significant knowledge to relevant fields, our study had some limitations. First, we used the EQ‐5D‐3L to assess the health‐related utility. Therefore, the accuracy of cost‐effectiveness may be restricted, particularly for mild depression. Second, as the study was conducted at a university hospital and a local psychiatric hospital, the participants may not represent the typical background of depressed patients in Japan. Similarly, given the probably longer than average pre‐training period, the competence of CBT therapists in this study might differ from that of an average CBT therapist in Japan. Third, the analysis was conducted from a narrow health insurance perspective (i.e. the costs of the healthcare utilization and medication were included, but others (e.g. welfare services) were not included. Fourth, the impact from a societal perspective is unclear, due to the perspective taken in the analysis. Fifth, the ICER threshold in the study was defined originally for the UK. This is solely because there is no established threshold for Japan. However, cost‐effectiveness must be ideally judged in the local context. Sixth, we did not perform a budget impact analysis. Hence, the total budget required to introduce the intervention to all patients was uncertain. Seventh, we estimated the sample size based on the power required to detect clinical differences rather than the difference in costs or cost‐effectiveness. Thus, attention should be paid to the aforementioned issues while interpreting the results.

In conclusion, augmented CBT for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression is not cost‐effective for all patients, including mild depression. However, it appeared to be cost‐effective if offered to patients with moderate/severe depression. This is according to the clinical recommendations by NICE. Researchers should use the EQ‐5D‐5L to obtain a more accurate estimate.

Disclosure statement

This study was funded by Health Labour Sciences Research grants from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. YO has received research support from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare and royalties from Igaku‐Shoin, Seiwa‐Shoten, Sogensha, and Kongo‐ Shuppan. DF has received royalties from Seiwa‐Shoten. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions

A.N. and M.S. conceived and designed the study. D.F. and T.K. refined the study protocol and its implementation. Y.O. offered cognitive‐behavioral therapy expertise and supervised the therapists. In the paper on cost‐effectiveness analysis, M.S. drafted the manuscript and conducted the cost‐effectiveness analyses with A.K. and Y.S. A.N., C.K., and D.M. contributed to the development of the dataset and conducted the cost analysis. Y.S. provided the methodological and statistical expertise. A.N. designed the study and was responsible for the study implementation, including the data collection, data integrity, analysis results, and analysis accuracy. M.S., A.K., M.M., and A.N. interpreted the results. M.S. and A.N. had complete access to all data, relevant to the cost‐effectiveness analysis, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analyses. All authors have critically reviewed the manuscript for its content and approved the final version.

Data availability

Data are available from the Department of Neuropsychiatry, the Keio University School of Medicine, if researchers meet the access criteria for sensitive data, as defined by the Ethics Committee of the Keio University.

Supporting information

Table S1‐a The formula to calculate mean weighted cost per DDD per day of each drug category.

Table S1‐b. Mean dose and prescription rates of antidepressants analyzed in the Nakagawa et al.

Table S1‐c. Mean dose and prescription rates of anti‐anxieties and hypnotics analyzed in the Nakagawa et al.

Table S1‐d. Mean dose and prescription rates of antipsychotics analyzed in the Nakagawa et al.

Table S1‐e. Mean dose and prescription rates of mood stabilizers analyzed in the Nakagawa et al.

Table S2. Sensitivity analysis with the CBT's unit cost of JPY 11 110 (equivalent to the unit cost in UK).

Table S3. Sensitivity analysis with all samples with LOCF method.

Table S4. Sensitivity analysis with the CBT's unit cost of JPY 11 110 (equivalent to the unit cost in UK) and with all samples with LOCF method.

Figure S1. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves when GRID‐HDRS17 is set as the clinical outcome.

Figure S2. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves when BDI‐II is set as the clinical outcome.

Figure S3. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves when QIDS‐SR is set as the clinical outcome.

Figure S4. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves of the sensitivity analysis (scenario 1) with the CBT unit cost of JPY 11 110 [equivalent to unit cost of CBT adopted in the relevant study in UK (GBP 73)] with (a) all samples, and (b) the patients with moderate/severe depression.

Figure S5. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves of the sensitivity analysis (scenario 2) with an imputation of the last observation carried forward (LOCF) with (a) all samples, and (b) the patients with moderate/severe depression.

Figure S6. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves of the sensitivity analysis (scenario 3) with the CBT unit cost of JPY 11 110 [equivalent to unit cost of CBT adopted in the relevant study in UK (GBP 73)], and with an imputation of the last observation carried forward (LOCF) with (a) all samples, and (b) the patients with moderate/severe depression.

Supplementary File S1. CONSORT check list.

Supplementary File S2. CHEERS check list.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kimio Yoshimura, MD, PhD of the Keio University School of Medicine, for his comments as a member of the Data Safety Monitoring Committee. The authors also appreciate the support provided by Yoko Ito, MS and Kayoko Kikuchi, PhD of the Project Management Office at the Keio Center for Clinical Research, for the construction of the electronic system and data management. These individuals reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Trial Registration: UMIN Clinical Trials Registry identifier: UMIN000001218

References

- 1. Souery D, Amsterdam J, de Montigny C et al. Treatment resistant depression: Methodological overview and operational criteria. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999; 9: 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR et al. Bupropion‐SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine‐XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006; 354: 1231–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement‐based care in STAR*D: Implications for clinical practice. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006; 163: 28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murray CJL. Choosing indicators for the health‐related SDG targets. Lancet 2015; 386: 1314–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: How did it change between 1990 and 2000? J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003; 64: 1465–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomas CM, Morris S. Cost of depression among adults in England in 2000. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003; 183: 514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sado M, Yamauchi K, Kawakami N et al. Cost of depression among adults in Japan in 2005. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011; 65: 442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiles N, Thomas L, Abel A et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care based patients with treatment resistant depression: Results of the CoBalT randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 381: 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakagawa A, Mitsuda D, Sado M et al. Effectiveness of Supplementary cognitive‐behavioral therapy for pharmacotherapy‐resistant depression: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017; 78: 1126–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakagawa A, Sado M, Mitsuda D et al. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy augmentation in major depression treatment (ECAM study): Study protocol for a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e006359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, CONSORT Group . Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008; 148: 295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Group C . CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010; 340: c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ 2013; 346: f1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV‐TR). American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV‐TR Axis I Disorders‐ Patient Edition (SCID‐I/P). Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fekadu A, Wooderson S, Donaldson C et al. A multidimensional tool to quantify treatment resistance in depression: The Maudsley staging method. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2009; 70: 177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tabuse H, Kalali A, Azuma H et al. The new GRID Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression demonstrates excellent inter‐rater reliability for inexperienced and experienced raters before and after training. Psychiatry Res. 2007; 153: 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams JB, Kobak KA, Bech P et al. The GRID‐HAMD: Standardization of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008; 23: 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Japanese Ministry of Health LaW . CBT Manual for Depression, a Therapist's Manual. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Young J, Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale Manual. University of Pennsylvania, Psychotherapy Research Unit, Philadelphia, PA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM et al. The 16‐Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS‐C), and self‐report (QIDS‐SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2003; 54: 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fujisawa D, Nakagawa A, Tajima M et al. Development of the Japanese version of quick inventory of depressive symptomatology self‐reported (QIDS‐SR16‐J). Stress Science 2010; 25: 43–52 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ministry of Health LaW . Statistics of medical care activities in public health insurance. In: Director‐General for Statistics and Information Policy. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: Results from a European multicenter study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007; 68: 1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory‐II. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kojima M, Furukawa TA, Takahashi H, Kawai M, Nagaya T, Tokudome S. Cross‐cultural validation of the Beck Depression Inventory‐II in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2002; 110: 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM et al. Validating the SF‐36 health survey questionnaire: New outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 1992; 305: 160–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fukuhara S, Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Wada S, Gandek B. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF‐36 Health Survey. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998; 51: 1045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. EuroQol Group . EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health‐related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fukuhara S, Ikegami N, Torrance GW, Nishimura S, Drummond M, Schubert F. The development and use of quality‐of‐life measures to evaluate health outcomes in Japan. Pharmacoeconomics 2002; 20: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development . National Accounts at a Glance. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development, Paris, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization . Defined Daily Dose (DDD). World Health Organization, Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Japanese Ministry of Health LaW . Medical Fee Revision in FY 2018. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, 2018. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakagawa A. International Comparison Study Related to the Prescription of Psychotropics. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, 2011. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 35. Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SS, Polsky D. Economic Evaluation in Clinical Trials. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tsuchiya A, Ikeda S, Ikegami N et al. Estimating an EQ‐5D population value set: The case of Japan. Health Econ. 2002; 11: 341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Commissioned by NICE . Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition). National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, London, 2009; 297. [Google Scholar]

- 38. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Commissioned by NICE . Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition). National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, London, 2009; 638. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hollinghurst S, Carroll FE, Abel A et al. Cost‐effectiveness of cognitive‐behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment‐resistant depression in primary care: Economic evaluation of the CoBalT trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014; 204: 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Commissioned by NICE . Depression: the Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition). National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, London, 2009; 568. [Google Scholar]

- 41. McPherson S, Cairns P, Carlyle J, Shapiro DA, Richardson P, Taylor D. The effectiveness of psychological treatments for treatment‐resistant depression: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2005; 111: 331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thase ME, Friedman ES, Biggs MM et al. Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second‐step treatments: A STAR*D report. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007; 164: 739–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Crick K, Al Sayah F, Ohinmaa A, Johnson JA. Responsiveness of the anxiety/depression dimension of the 3‐ and 5‐level versions of the EQ‐5D in assessing mental health. Qual. Life Res. 2018; 27: 1625–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mulhern B, Mukuria C, Barkham M et al. Using generic preference‐based measures in mental health: Psychometric validity of the EQ‐5D and SF‐6D. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014; 205: 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five‐level version of EQ‐5D (EQ‐5D‐5L). Qual. Life Res. 2011; 20: 1727–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kendrick T, Peveler R, Longworth L et al. Cost‐effectiveness and cost‐utility of tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and lofepramine: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2006; 188: 337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ninomiya A, Sado M, Park S et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy in patients with anxiety disorders in secondary‐care settings: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020; 74: 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Survey of Medical Care Activities in Public Health Insurance. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1‐a The formula to calculate mean weighted cost per DDD per day of each drug category.

Table S1‐b. Mean dose and prescription rates of antidepressants analyzed in the Nakagawa et al.

Table S1‐c. Mean dose and prescription rates of anti‐anxieties and hypnotics analyzed in the Nakagawa et al.

Table S1‐d. Mean dose and prescription rates of antipsychotics analyzed in the Nakagawa et al.

Table S1‐e. Mean dose and prescription rates of mood stabilizers analyzed in the Nakagawa et al.

Table S2. Sensitivity analysis with the CBT's unit cost of JPY 11 110 (equivalent to the unit cost in UK).

Table S3. Sensitivity analysis with all samples with LOCF method.

Table S4. Sensitivity analysis with the CBT's unit cost of JPY 11 110 (equivalent to the unit cost in UK) and with all samples with LOCF method.

Figure S1. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves when GRID‐HDRS17 is set as the clinical outcome.

Figure S2. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves when BDI‐II is set as the clinical outcome.

Figure S3. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves when QIDS‐SR is set as the clinical outcome.

Figure S4. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves of the sensitivity analysis (scenario 1) with the CBT unit cost of JPY 11 110 [equivalent to unit cost of CBT adopted in the relevant study in UK (GBP 73)] with (a) all samples, and (b) the patients with moderate/severe depression.

Figure S5. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves of the sensitivity analysis (scenario 2) with an imputation of the last observation carried forward (LOCF) with (a) all samples, and (b) the patients with moderate/severe depression.

Figure S6. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves of the sensitivity analysis (scenario 3) with the CBT unit cost of JPY 11 110 [equivalent to unit cost of CBT adopted in the relevant study in UK (GBP 73)], and with an imputation of the last observation carried forward (LOCF) with (a) all samples, and (b) the patients with moderate/severe depression.

Supplementary File S1. CONSORT check list.

Supplementary File S2. CHEERS check list.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the Department of Neuropsychiatry, the Keio University School of Medicine, if researchers meet the access criteria for sensitive data, as defined by the Ethics Committee of the Keio University.