Summary

Despite the acknowledged injustice and widespread existence of parachute research studies conducted in low‐ or middle‐income countries by researchers from institutions in high‐income countries, there is currently no pragmatic guidance for how academic journals should evaluate manuscript submissions and challenge this practice. We assembled a multidisciplinary group of editors and researchers with expertise in international health research to develop this consensus statement. We reviewed relevant existing literature and held three workshops to present research data and holistically discuss the concept of equitable authorship and the role of academic journals in the context of international health research partnerships. We subsequently developed statements to guide prospective authors and journal editors as to how they should address this issue. We recommend that for manuscripts that report research conducted in low‐ or middle‐income countries by collaborations including partners from one or more high‐income countries, authors should submit accompanying structured reflexivity statements. We provide specific questions that these statements should address and suggest that journals should transparently publish reflexivity statements with accepted manuscripts. We also provide guidance to journal editors about how they should assess the structured statements when making decisions on whether to accept or reject submitted manuscripts. We urge journals across disciplines to adopt these recommendations to accelerate the changes needed to halt the practice of parachute research.

Keywords: authorship, ethics, global health, health equity, international health, research, research ecosystem

Recommendations

Journals and journal editors have a responsibility to leverage their formal power within the scientific publication process to promote equitable partnership between international researchers from high‐ and low‐to‐middle‐income country (LMIC) settings. Promotion of equitable partnership may include activities to support research capacity (both personnel and infrastructure) in addition to manuscript authorship.

For research conducted in LMIC settings in partnership with researchers from high‐income countries (HICs), there should be an expectation of inclusion of local researchers in first and/or last authorship positions reflecting significant ownership and/or leadership contribution to the work presented. This could include the use of joint first and joint senior authorship.

Journals should remove arbitrary limits on the numbers of permitted authors within accepted manuscripts to support equitable inclusion of those currently disadvantaged by those limits (e.g. LMIC researchers; early career researchers; minority groups; and women).

For manuscripts reporting research conducted in LMICs by collaborations including one or more HIC partner, journals should require that authors submit a structured reflexivity statement to describe the ways in which equity has been promoted in the partnership that produced the research. This statement should be published within accepted manuscripts, using a similar approach to conflict‐of‐interest, contributorship and patient/public involvement statements. Prospective authors should consider the need for reflexivity statements at the point of research conceptualisation and promote equitable partnership from the outset of their international collaboration. Editors and reviewers should use standardised and transparent methods to examine structured reflexivity statements as a component of the overall assessment for publication.

Publishers and Editors‐in‐Chief should consider making research that has been conducted in LMICs free on their websites, in the interests of advancing scholarship, dissemination and evidence uptake for local and international impact.

Research institutions and funders should consider adoption of similar tools to promote equitable international partnerships.

What other guidelines are available on this topic?

There are reporting guidelines for authorship or contributorship implemented by academic journals and researchers [1, 2, 3, 4], but there is so far no publication or manuscript reporting format specific to international partnerships. There is also no standardised data collection methodology aimed at interrogating or facilitating the equity of such collaborations. Further, while there are guidelines on how to conduct equitable partnerships, these do not make specific recommendations on how to report authorship and contributorship decisions within such partnerships or collaborations [5, 6, 7].

Why was this consensus statement developed?

Parachute (or ‘helicopter’) research is the practice of conducting primary research within a host country and subsequently publishing findings with inadequate recognition of local researchers, staff and/or supporting infrastructure [8]. This issue is particularly pertinent when research is conducted in LMICs by collaborations including one or more HIC partners. This widespread practice has been documented across multiple disciplines and settings across the scientific literature [8, 9, 10]. Lack of equitable partnerships between HIC and LMIC collaborators may lead to extractive approaches to research. This, in turn, is often driven by and may propagate inequities in the broader research ecosystem. Funders, research institutions, researchers and scientific journals may all contribute to this imbalance. The purpose of this consensus statement is to recognise the power and attendant responsibility that journals have within this ecosystem, and to explore actions they can take, not only to discourage parachute research but also to encourage equitable collaborations and redress current imbalances that disadvantage LMICs. We have drawn together international expertise in research and publication from diverse disciplines and from HICs and LMICs to construct guidelines that can be applied by journals to inform editorial decisions regarding the publication of research arising from LMIC–HIC partnerships. Our aim is that these recommendations will be broadly applicable within academic publishing; of use to international researchers at the point of study or partnership conceptualisation; and increase awareness of this issue among the general readership of academic journals.

How and why does this consensus statement differ from existing guidelines?

Academic journals have so far not developed a collective official position or guidelines to promote equity in partnerships between HIC and LMIC researchers. Without such guidelines, many academic journals continue to publish papers indicative of parachute research. In some journals, papers are published with an explanation as to why LMIC contributors were not included as authors (e.g. for reasons that may be personal or political [11]). Other journals have either made public statements (e.g. through an editorial [8, 12, 13]) or indicated explicitly (e.g. on their “information for authors” page [14]) that they will not consider such manuscripts for publication. While these positions and practices exist among journals, there is so far no standardised format in which authors and/or journals may go beyond the binary of publishing or not publishing papers reporting studies conducted in LMICs without LMIC authors.

Introduction

The under‐representation of LMIC researchers in the authorship of research conducted in LMICs is well described [15]. A recent analysis of the nine highest impact medical and global health journals found that almost 30% of publications of primary research conducted in LMICs did not contain any local authors [15]. In this study, half of all LMIC research articles were from Africa. International research collaborations in Africa involving HIC researchers are, therefore, an important area of focus for understanding the phenomenon of parachute research.

Spending on research by African nations is very low, with no country so far investing the targeted 1% of gross domestic product on research [16]. This shortfall leads to a strong focus on collaborations with HIC institutions [17]. Unequal opportunities for local researchers can arise in such collaborations and are reflected in publications being authored mainly, or exclusively, by researchers from outside the country of study. This deprives African investigators of career‐essential steps to build their research portfolio [18, 19, 20, 21]. Disparities in authorship, particularly in global health research, have been exhaustively discussed, but there has been little perceptible change over time [8, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. While the frequency of publications from Africa has risen since 2000, this has been accompanied by a disproportionate increase in first author positions for HIC compared with LMIC researchers [22]. In another analysis, however, there had been no change in the proportion of LMIC authors over a 10‐year period [26]. Systematic analyses show that lead authors (whether in the first or last author positions) tend to be mainly from middle‐income countries and not from low‐income countries, most of which are in Africa [30, 33]. Even the most recent COVID‐19 literature has been heavily biased with one analysis showing no African authors present in one‐fifth of papers published from the continent [34].

The issue of inequitable authorship distribution is clearly far from resolved and needs defined actions to promote change. Evidence from middle‐income countries in Africa and elsewhere which demonstrate improving inclusion of local authors in prominent author positions shows that positive change is possible [22, 23, 26]. However, structural barriers persist. High‐income country researchers and institutions often drive the study design and funding processes, such that local researchers are frequently offered only technical tasks (e.g. data collection or running questionnaires) with little opportunity to advance beyond middle author positions, the so‐called ‘stuck in the middle’ phenomenon [33]. This issue appears to be particularly stark among the highest‐ranked universities in the USA [33]. For example, a recent analysis of published clinical trials across all LMIC settings found significantly fewer LMIC first authors in US‐funded research compared with non US‐funded research [22].

Low‐ and middle‐income country researchers are also more likely to publish in lower impact journals [22, 33]. In one analysis from 2018, only half of articles published about Africa in Lancet Global Health (currently the highest‐ranked global health journal by impact factor) had LMIC authors [24]. However, the publication of parachute research is not only confined to global health journals; it also occurs in specialised journals across a wide variety of disciplines. Indeed, a series of recent submissions suspected of parachute research led the editorial board of Anaesthesia to launch an enquiry. The subsequent wider ranging consultation resulted in the development of the current consensus statement.

Methods

Development of consensus statement: overview

This consensus statement was developed in five stages, including three workshops and four narrative literature reviews, as follows: workshop 1 (agreement of definitions, discussion of context including equitable partnerships and responsibilities of journals); workshop 2 (preliminary discussion of structure and practicalities of reflexivity statements discussion, identification of priority topics for review to inform recommendations); narrative reviews of prioritised topics; workshop 3 (presentation of narrative reviews, discussion of draft reflexivity statement and iterative online refinement of consensus and reflexivity statements). These were then peer reviewed by experts in global health and senior journal editors who were independent of the core writing team.

Expert group composition

In the light of evidence of the preponderance of parachute research from Africa, invitations were sent to researchers and editors involved in global health research from research institutions in Africa, the UK and Australia. Participants were purposively selected to include representation from East (Kenya and Tanzania), West (Nigeria) and Southern (Malawi and South Africa) Africa (see online Supporting Information, Appendix S1), and representation of researchers and editors of specialist and global health journals from a range of disciplines and all levels of seniority.

Literature review methodology

Narrative reviews were conducted to gain insights from the existing literature in the four areas identified in the first two workshops as essential to the development of the consensus statement and design of reflexivity statements. These areas were themselves issues of some complexity. The hermeneutic narrative review methodology was therefore selected as it allows the ‘interpretive and discursive’ synthesis necessary to address complex and multifaceted issues [35, 36]. Teams of authors completed the reviews as follows: the research ecosystem (AO, BB, MS); the power and responsibility of journals (LR, AV); and harms and safeguarding in relation to publication in HIC and LMIC partnerships (CK, SS). Current guidelines on equitable research partnerships with respect to publication and capacity strengthening were reviewed by RM and NO and they led the initial framing of the reflexivity statement, which, by consensus after both workshops, was structured around existing International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) domains [4].

Given the varied nature of the themes, search strategies differed slightly between the reviews. Overall, they comprised searches of online databases (Medline, CINAHL and Global Health) using a combination of medical subject headings (MESH) and text words relating to respective themes (see Box 1) and to LMIC; review of identified articles; consultation with key guidance (e.g. publicationethics.org guidelines, case studies and discussion relating to authorship); and additional methods including snowballing, author and grey literature searches, coverage of social media and other online sources as well as, citation tracking and recommendations from other review teams [35]. As the early stages of data collection found a surprising lack of existing definitions of the ‘research ecosystem’, AO, BB and MS engaged the services of a librarian to investigate the possibility of omissions. Searching for this theme was therefore somewhat more exhaustive than for the others. Results were reviewed at the third workshop. The reflexivity statements for authors and editors were further refined at the workshop and through subsequent electronic reviews. Due to the substantial synergy between several of the original themes and in response to expert reviewer feedback, we have synthesised the literature review under two distinct themes: the research ecosystem and the role of journals. Within each theme we have described sub‐themes that emerged as important to understanding the issues that need to be addressed. A final section discusses practical issues relating to authorship in the context of north–south collaborations that emerged from the literature review and discussion. This synthesis is presented below.

Box 1. Search terms used for narrative reviews.

| Research ecosystem | Power and responsibility of journals | Harms and safeguarding |

|---|---|---|

|

The research system or partnerships “research system”, or “research process”, or “research actor”, or “research collaboration”, or “research partnership”, or “global health research”, or “research environment” |

“editorial power”, or “editor responsibilities”, or “reviewer bias”, or “publication ethics” |

Initial search terms included the following, individually and in combination: “global health”, international health”, “research partnerships”, “research participants”, “ethic*”, “bioethic*”, “harm”. |

|

Fairness and equity (MH “ethics, research+)”, “ethic” or “fair”, or “fairness”, or “equal*”, or “equit*”, or “inequit*” |

The research ecosystem

Both research and academic publications are produced by processes and partnerships that occur within a broader research ecosystem. Although the term is widely used, there are few definitions of this ecosystem. Where they exist, definitions often refer to the components of the ecosystem with little or no discussion about how the system works [37]. For example, the Wellcome Trust describes the research ecosystem in terms of constituent elements: researchers; their outputs; research managers; research institutions; funders; governments; policymakers; communication specialists; and the private sector. It does not describe how these constituents interact with each other, or the factors that affect those interactions [38]. To understand how parachute research and subsequent inequities in authorship occur, a less horizontal understanding of the research ecosystem is needed.

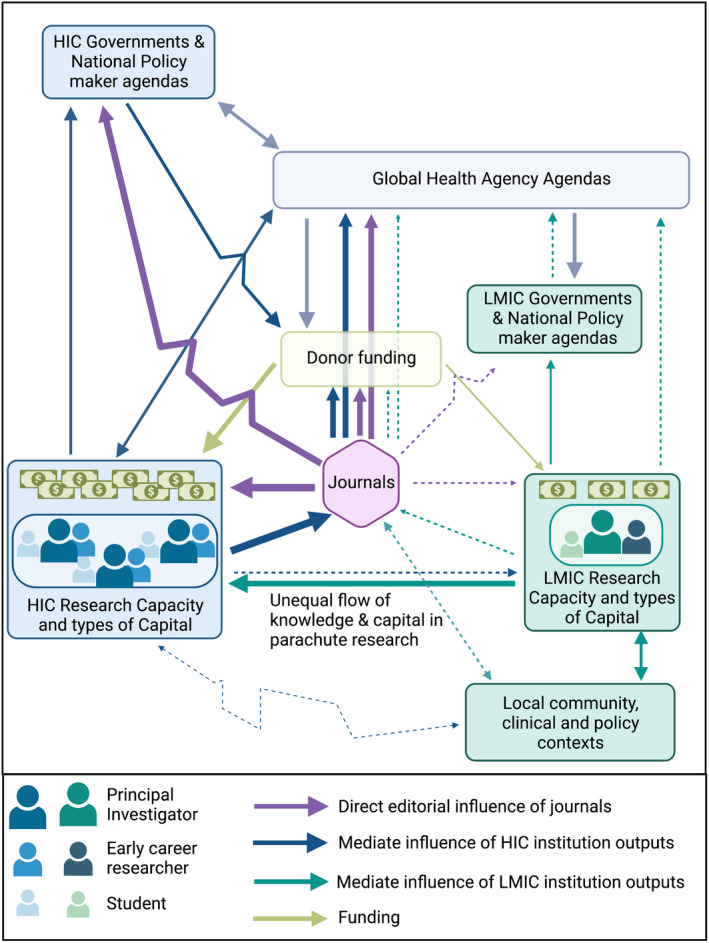

To address this, we propose the global health research ecosystem be defined as “the dynamic system of local, national and international institutions and actors involved in the commissioning, generation, management, curation, dissemination and consumption of research, who, having different interests, types and levels of capital, are linked and affected by feedback loops of influence and power.” (Fig. 1) [39]. Critically, actors and institutions within this system operate from different positions of power [40], in an architecture which is strongly informed by the colonial origins of global health research [41]. This power varies in nature and comes from different kinds of ‘capital’, for example knowledge, skill, status or financial resources [40, 42]. This ranges from power over junior researchers (e.g. by principal investigators), to financial control over international research agendas (by donors, for instance). This power may be used in service of individual or institutional self‐interest [40]. For example, parachute research is possible due to the power that HIC researchers frequently have to dictate the terms of both the conduct and reporting of research. Exemplars of differences in power and influence between HIC and LMIC institutions are illustrated in Figure 1. Action must be taken to redress these power balances if current inequities are to be resolved.

Figure 1.

The position and power of journals within the global health research ecosystem. Journals influence the ecosystem by: (a) brokering research outputs which are predominantly led from HIC institutions; and (b) direct editorial statements (e.g. through ‘commissions’). These journal activities influence research prioritisation and funding allocation. The current predominance of HIC outputs and perspectives in journal activities further amplifies the impact of HIC perspectives on donor funding and research agendas. This can worsen existing inequities.

Equitable partnership

The power imbalance that stems from the control that HIC research partners have over access to funds – and therefore perpetuates ‘colonial’ relations with LMIC partners – is well described [43, 44]. Research agenda and priority‐setting are frequently driven by actors outside the research locality. The negative effects that this can have on the value of research are increasingly recognised [45]. The foreign researcher writing from a foreign gaze may well produce data publishable in high‐impact journals, but this model frequently has little or no impact on local practice or policy [45]. There already exist a number of guidance documents for funding bodies to facilitate equitable partnerships and to ensure that research questions are responsive to LMIC research and policy priorities [46, 47]. These emphasise that responsibility, accountability and governance of research should be jointly shared in international research collaborations. For example, the Research Fairness Initiative encourages equity of participation between partners from research conception to sharing of benefits and outcomes [48]. But while current guidelines recognise authorship as a benefit that should be shared, they all fall short of specifying how this aspiration should actually be achieved [46, 48, 49, 50].

Local infrastructure and training opportunities

Limited training opportunities in some LMIC settings can impact on researchers’ capacity for authorship and career advancement [51, 52, 53, 54]. Where there is limited academic infrastructure and career opportunities, LMIC collaborators may not be able to benefit from the research partnership. This can be particularly relevant to those low‐income countries where immediate economic priorities may take precedence over longer term career advancement opportunities. Research capacity strengthening at multiple levels is therefore required to address imbalances in power and opportunity. This includes the development of individual competencies (e.g. student support) through to improved institutional infrastructure and capacity to engage with local research and policy priorities [44, 55]. Meaningful capacity strengthening is most effectively delivered in an environment where there is equal contribution to the development of research questions and study design from both HIC and LMIC partners [50]. Consistently ensuring such equity of contribution may, over time, help to resolve current imbalances of power and opportunity.

Harms and safeguarding within international research

Financial and other power inequities can limit the capacity of an LMIC partner to refuse to collaborate in a given research project [56], and restrict their influence in research priority‐setting and decision‐making around research implementation [5, 57]. Inability to articulate concerns or conflicts in perceptions of the research meaning and implications can undermine the integrity of research implementation [58, 59]. Furthermore, local researchers can experience discomfort or compromise because they have (or perceive) conflicting responsibilities to their community(ies) and HIC research partner(s) [60, 61]. The coercive impact of power differentials can place LMIC researchers at risk of real harm if they are involved in research that fits poorly with local sociocultural norms/priorities. Examples include researchers working on studies that become associated with local issues of concern, such as beliefs around the stealing of blood, with links to extractive colonial relations [62, 63, 64] or, more recently, community concerns around COVID‐19 and vaccination (E. Makepeace, personal communication, 24 March 2021). Some research topics and findings may go against the narrative and interests of autocratic governments [65]. These and other instances of international collaborations addressing issues of local sensitivity or contention can potentially cause social, reputational and security risks to the local researcher. In such instances, local researchers may need to avoid being named as authors on such studies. It is important that discussions of equity and authorship in such collaborations are sensitive to these complexities.

The role of journals

Publication record is a key metric of success in academia. Editorial decisions thus have the power to impact career progression and future grant income streams at individual and institutional levels. More broadly, journal editors drive research agendas by signalling what is valued in scientific publishing (Fig. 1) [42]. In a recent survey, over 80% of authors felt that journal editors exercise considerable power [66]. However, journal editors are influenced by external pressures and internal biases. For example, an editor may accept a manuscript for publication for reasons which they feel may increase the journal impact factor, such as expected number of citations (even though this may not be the best measure of scientific quality or value), or to increase readership by courting senior scientists who are popular or prolific. Further, a manuscript may be judged more favourably if it is within the editors’ or editorial board members’ research interests, is led by members of their peer groups or is from a well‐known research institute [Murray et al., preprint, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/400515v3.full].

Editorial responsibility

To offset these potential pressures and biases, journal editorial boards need to be diverse. However, editorial boards of global health journals [67, 68] and of high‐impact journals [69, 70] are not representative of researchers in LMICs. This inadequate diversity is reflected in what academic journals choose to publish. If opportunities for academic publication, recognition and influence are inequitably distributed among scientists with different personal attributes (race; nationality; religion; class; and personal qualities), this will negatively impact the equity of the research ecosystem [71]. These imbalances in editorial processes represent an important barrier to researchers from LMICs who are attempting to publish their data [45].

Editors exert substantial formal power in the publishing process. The extent and far‐reaching implications of this power mean that editors should exhibit fairness and responsibility. They must be cognisant of the risk of conscious and unconscious biases when deciding to accept or reject a scientific manuscript and of their responsibility to promote equity. This is likely to require formal training. A list of core competencies for scientific editors has been agreed [72]. However, senior editorial appointments are typically made outside of formal regulated processes and training is limited. In one study, 45% of appointees had no formal training and 35% had no previous editorial board experience [73].

Journal editors are responsible for ensuring equity, integrity, transparency and fairness in the publication process. Indeed, failure to discharge this responsibility may further prejudice the very groups that science seeks to serve. While editors primarily make decisions based on research quality, conflict of interests and ethical issues are frequently subjected to less scrutiny and issues of equity can be overlooked [74]. Conversely, attribution for authors and contributors is one of the core principles of publication ethics but, to date, the focus has been on gatekeeping to prevent false claims. For example, the Committee on Publication Ethics provides advice to address suspicions of ghost authorship [75]. More detailed guidance is also required for situations when authors are suspiciously absent.

Verification of equitable authorship is challenging

Journals should have clear policies on authorship and a way to determine if authorship roles are missing or have been unfairly allocated [76]. There is also a clear need to maintain robust ethical standards and to encourage equitable academic partnership [77]. Such positive action is in line with recent calls for journals to be explicit about their power and the increasingly recognised social justice mission of global health research [78, 79]. However, such positive action is not without risk. Blanket judgements that HIC researchers are empowered in relation to LMIC researchers fail to recognise the impact of hierarchies of power such as sex and seniority [80]. For example, it is conceivable that early career female researchers and minorities within HIC research institutions may be disadvantaged in relation to well‐established senior male researchers in LMIC institutions (Fig. 1).

One of the major challenges for studies assessing equity in authorship distribution is that, like most measures, institutional affiliation cannot fully describe the complexity of an author’s identity and positionality. Because, like sex, it is easily measured, institutional affiliation is one of the very few indicators currently available by which equity within partnerships can be measured. However, the complexity of some partnerships may prevent outsiders from understanding their history or constituent relationships. Authorship distribution may therefore not always be the best reflection of, or correct measure to assess, equity within those partnerships. But, despite their limitations, as some of the few attributes that are visible from the outside, indicators such as author’s sex and institutional affiliations remain useful proxies for equity within partnerships.

Nevertheless, there are instances in which an author's institutional affiliation may not be an appropriate measure at all. For example, an author's affiliation may be irrelevant to the content of the article (e.g. authors in a HIC may analyse publicly available data from a number of LMICs to learn how to address a problem in their HIC). Second, an author's affiliation may fail to capture an author’s full positionality or identity (e.g. an author writing about a health issue in their home LMIC, while temporarily affiliated to a HIC institution). Third, an author’s affiliation to a HIC institution may be necessary to write about a contentious issue (e.g. post‐war health implications in a country ruled by a dictator who led the army that committed war atrocities). Fourth, an author’s affiliation may not reflect their experience or knowledge of an issue (e.g. an author writing about a health issue in their home LMIC, where they have lived most of their life or from where they have migrated, while based in a HIC). These dynamics may explain some instances of (apparent) lack of equitable LMIC representation in authorship. Indeed, the ‘academic migration’ that occurs from the LMICs to HICs may significantly skew institutional affiliation. However, such instances ought to be the exception rather than the rule, so the expectations of equity in authorship distribution remain valid. But it is due to such potential exceptions that it is not appropriate to recommend that journals rely solely on author affiliations to assess LMIC representation. Rather each submitted manuscript should be assessed on a case‐by‐case basis.

Structured reflexivity statements

Structured reflexivity statements provide a mechanism for such case‐by case assessments. Their use for global health research publications has previously been proposed [45]. For this consensus statement, we have built on this concept to develop an operationalisable checklist of questions that authors from international partnerships involving researchers from both HICs and LMICs should address (Table 1). We recommend that journals who receive manuscript submissions from such partnerships should require authors to specifically address these points in a manner akin to conflict‐of‐interest statements. We suggest that this process will contribute to positive change within the research ecosystem through the explicit description by authors of the measures they have incorporated within their collaboration to promote equitable partnership. As such statements accumulate, and novel methods to engender partnerships emerge, this has the potential to generate new knowledge to address the issue of parachute research.

Table 1.

Structured reflexivity statement to be completed with manuscript submissions from international research partnerships involving researchers from high‐ and low‐to‐middle‐income countries. This describes 15 questions that should be addressed by corresponding authors on behalf of an international research partnership. The questions are intentionally open‐ended and designed to address specific components of equitable research partnership. It may be that not all questions can be addressed (e.g. a small project with minimal or no funding) but researchers should be able to describe individual components that they have considered when developing their partnership.

| Question | |

|---|---|

| Study conceptualisation |

|

| Research management |

|

| Data acquisition and analysis |

|

| Data interpretation |

|

| Drafting and revising for intellectual content |

|

| Authorship |

|

| Training |

|

| Infrastructure |

|

| Governance |

|

However it is essential that the loop of author declaration and editorial assessment is closed to promote a meaningful and transparent process of manuscript assessment. We have therefore also suggested an assessment checklist that editors should use to inform decisions about the risk of parachute research within individual manuscript submissions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Editor/reviewer checklist for assessment of international partnership reflexivity statement. Designed as a transparent tool to help editors and reviewers assess reflexivity statements submitted by international research partnership teams involving collaboration between high‐ and low‐to‐middle‐income country researchers. Editors and reviewers should consider these questions when assessing such submissions to reduce the risk of parachute research and to promote equitable partnership.

| Question | |

|---|---|

| Engagement |

|

| Co‐development |

|

| Authorship |

If not, what is the explanation?

|

| Dissemination |

|

Editorial review of reflexivity statements

We suggest that the structured statement should be mandatory for manuscript submissions reporting research conducted in LMIC by collaborations including one or more HIC partners. These statements should be published as a footnote within the journal. We propose that these statements will be reviewed during the editorial process to inform decisions on manuscript acceptance. Initially, while this process is adopted and progressively embedded as routine practice within journals, we anticipate that the definition of what constitutes an ‘equitable partnership’ will be further refined. We anticipate that, as statements are accrued, quality indicators and tools to systematically assess the equity of research partnerships will also be refined. During this interim period, journals should provide ‘example statements’ graded according to project size and funding, and research methodology to guide authors on what the journal is seeking. These statements should ideally be made available on guidance for authors web pages, bespoke to each journal signatory.

Broader practicalities of promoting equitable authorship

Appropriate acknowledgement of contributors to research conducted in LMICs requires a holistic and inclusive view of what is needed to deliver high‐quality research. This includes building and maintaining collaborations, designing inputs and facilitating research conduct that draws on local knowledge and interpretation. It should therefore go beyond simple acknowledgement of local field workers and data managers [54]. Substantive representation of both HIC and LMIC partners, including first and senior authorship positions for LMIC collaborators, should reflect the fairness of opportunity and leadership in the process that is the aspiration of guidance such as the Research Fairness Initiative [48]. Low‐ and middle‐income country early career researchers and minority groups should be supported in their career development [81, 82, 83].

All authors must have the opportunity for final sign off for research outputs before publication. However, challenges that some research partners have in accessing conventional word processor tools to review research outputs (e.g. limited access to computer hardware and internet connectivity) should be recognised. Alternative communication methods (e.g. WhatsApp and Zoom calls) should be promoted to facilitate inclusivity. Through this process, ICMJE authorship criteria [4] should proactively be leveraged to promote the inclusion of authors rather than facilitate their exclusion as has sometimes been the case.

Another practical way to facilitate equitable first and senior authorship is through the adoption of multiple joint first and senior authors. The abandonment of journal limitations on the number of authors is another practical way to facilitate this process. This would encourage senior authorship teams to constructively use ICMJE criteria [4] to proactively include rather than exclude individuals who make substantial research contributions [83]. Careful consideration should be given by journal editors to promote research whose inclusive authorship can facilitate the usefulness and uptake of research findings in the local setting [54, 84].

Finally, open access publication is extremely valuable to ensure dissemination of global health research findings to the wider research community. This is especially important if the LMIC communities who provide data are to be better enabled to use findings to develop and implement their own research and publications [85, 86, 87]. We suggest editors should encourage and facilitate open access publishing from international research partnerships in this spirit.

Limitations

This consensus statement has several limitations. The authorship team comprises journal editors (BM, AV, EH, BB, LR, SA and NO) and experts in international research (RM, SS, CK, MS, BB, JM, SA, NO and AO). We have provided a detailed reflexivity statement to explore authorship of this piece in more detail (see online Supporting Information, Appendix S1). We have not included stakeholder representatives from major funders, policymakers, civil societies and non‐governmental organisations within this team. While there is a focus on authorship within our recommendations, we explicitly recognise that authorship should not be the sole determinant of equitable partnership. For this reason, we have included training and capacity building questions within the structured reflexivity statement as additional ways in which equitable partnerships can be promoted within international collaborations. There are also limitations associated with our methodology of conducting our narrative review. For example, we have not explicitly assessed included articles for validity, nor have we applied tools to measure potential bias.

Our workshop participants and discussion focus heavily on researchers and research conducted in Africa. There may be contextual and other issues relating to parachute research in other LMIC settings that we have missed. However, Africa’s prominence in international partnerships, in global health research and as a site of much parachute research makes addressing extractive research practices a priority. Also, in reality, the underlying power differentials between HIC and LMIC partners that drive parachute research appear ubiquitous across LMICs. Lessons from Africa are therefore likely to be highly transferable across LMICs elsewhere.

Next steps

Our hope is that these guidelines will be adopted by multiple scientific journals to reduce the risk of parachute research and promote equitable partnership within collaborations between HIC and LMIC partners. As researchers adapt to the new requirements and as journals require them for manuscript submission and publication, our aim is that the equity of partnerships will be considered proactively and addressed from the outset of prospective collaborations, at the point of research conceptualisation. We specifically recommend that structured reflexivity statements should be published with accepted manuscripts. As this process becomes established, and recommendations are iteratively refined, we anticipate that these statements will become a useful resource, providing examples of innovative practice to improve equity within the research ecosystem. Finally, we suggest that research institutions and funders collect and monitor details from employees and applicants on how equitable partnerships are actively being promoted. We hope that widespread adoption of this approach will accelerate progression towards equity in international research collaborations between HIC and LMIC partners.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Reflexivity statement.

Acknowledgements

BM, AV and RM are the joint first authors and SA, AO and NO are the joint senior authors. BM and AV are the editors of Anaesthesia. Figure concept and design AO; figure production by MS and EH using Bio Render™. We thank Alison Derbyshire for her assistance in searching for and retrieving articles. We have provided detailed information on author contributions and positionality within our reflexivity statement in online Supporting Information Appendix S1. No external funding or other competing interests declared.

MS was fully, and AO and JC were partially, funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). We thank the NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Lung Health and TB in Africa at LSTM ‐ “IMPALA” for helping to make this work possible. In relation to IMPALA (grant number 16/136/35) specifically: IMPALA was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research (GHR) using UK aid from the UK Government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This article is accompanied by an editorial by Jumbam, Touray and Totimeh, Anaesthesia, 2022; 77: 243–7.

Contributor Information

B. Morton, @benjamesmorton.

R. Masekela, @Bronchigirl.

E. Heinz, @EvaHeinz7.

S. Saleh, @SepSaleh.

C. Kalinga, @MissChisomo.

M. Seekles, @maaikeseekles.

B. Biccard, @BruceBiccard.

S. Abimbola, @seyeabimbola.

A. Obasi, Email: angela.obasi@lstmed.ac.uk, @Obasi_TropMed.

N. Oriyo, @ndeky.

References

- 1. Rennie D, Yank V, Emanuel L. When authorship fails. A proposal to make contributors accountable. Journal of the American Medical Association 1997; 278: 579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bates T, Anić A, Marusić M, Marusić A. Authorship criteria and disclosure of contributions: comparison of 3 general medical journals with different author contribution forms. Journal of the American Medical Association 2004; 292: 86–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schroter S, Montagni I, Loder E, Eikermann M, Schäffner E, Kurth T. Awareness, usage and perceptions of authorship guidelines: an international survey of biomedical authors. British Medical Journal Open 2020; 10: e036899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors . Defining the role of authors and contributors. 2021. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles‐and‐responsibilities/defining‐the‐role‐of‐authors‐and‐contributors.html (accessed 19/04/2021).

- 5. Carvalho A, IJsselmuiden C, Kaiser K, Hartz Z, Ferrinho P. Towards equity in global health partnerships: adoption of the Research Fairness Initiative (RFI) by Portuguese‐speaking countries. British Medical Journal Global Health 2018; 3: e000978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ward CL, Shaw D, Sprumont D, Sankoh O, Tanner M, Elger B. Good collaborative practice: reforming capacity building governance of international health research partnerships. Global Health 2018; 14: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zaman M, Afridi G, Ohly H, McArdle HJ, Lowe NM. Equitable partnerships in global health research. Nature Food 2020; 1: 760–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Health TLG. Closing the door on parachutes and parasites. Lancet Global Health 2018; 6: e593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Minasny B, Fiantis D, Mulyanto B, Sulaeman Y, Widyatmanti W. Global soil science research collaboration in the 21st century: time to end helicopter research. Geoderma 2020; 373: 114299. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stefanoudis PV, Licuanan WY, Morrison TH, Talma S, Veitayaki J, Woodall LC. Turning the tide of parachute science. Current Biology 2021; 31: R184–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tamming T, Otake Y. Linking coping strategies to locally‐perceived aetiologies of mental distress in northern Rwanda. British Medical Journal Global Health 2020; 5: e002304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Urassa M, Lawson DW, Wamoyi J, et al. Cross‐cultural research must prioritize equitable collaboration. Nature Human Behaviour 2021; 5: 668–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winker MA, Ferris LE, Editors & the World Association of, M. WAME Editorial. Promoting global Health: the World Association of Medical Editors position on editors’ responsibility. Telehealth and Medicine Today 2018; 1. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tropical Medicine and International Health . Author Information Page. 2021. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/page/journal/13653156/homepage/forauthors.html (accessed 19/04/2021).

- 15. Ghani M, Hurrell R, Verceles AC, McCurdy MT, Papali A. Geographic, subject, and authorship trends among LMIC‐based scientific publications in high‐impact global health and general medicine journals: a 30‐month bibliometric analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health 2021; 11: 92–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Bank . Research and development expenditure (% of GDP). 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GB.XPD.RSDV.GD.ZS (accessed 25/05/2021).

- 17. Simpkin V, Namubiru‐Mwaura E, Clarke L, Mossialos E. Investing in health R&D: where we are, what limits us, and how to make progress in Africa. British Medical Journal Global Health 2019; 4: e001047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hasnida A, Borst RA, Johnson AM, Rahmani NR, van Elsland SL, Kok MO. Making health systems research work: time to shift funding to locally‐led research in the South. Lancet Global Health 2017; 5: e22–e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uthman OA, Uthman MB. Geography of Africa biomedical publications: an analysis of 1996–2005 PubMed papers. International Journal of Health Geography 2007; 6: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fourie C. The trouble with inequalities in global health partnerships. Medicine Anthropology Theory 2018; 5: 142–55. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tijssen RJW. Africa’s contribution to the worldwide research literature: new analytical perspectives, trends, and performance indicators. Scientometrics 2007; 71: 303–27. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kelaher M, Ng L, Knight K, Rahadi A. Equity in global health research in the new millennium: trends in first‐authorship for randomized controlled trials among low‐ and middle‐income country researchers 1990–2013. International Journal of Epidemiology 2016; 45: 2174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schneider H, Maleka N. Patterns of authorship on community health workers in low‐and‐middle‐income countries: an analysis of publications (2012–2016). British Medical Journal Global Health 2018; 3: e000797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iyer AR. Authorship trends in the Lancet Global Health. Lancet Global Health 2018; 6: e142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adedokun BO, Olopade CO, Olopade OI. Building local capacity for genomics research in Africa: recommendations from analysis of publications in Sub‐Saharan Africa from 2004 to 2013. Global Health Action 2016; 9: 31026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rees CA, Lukolyo H, Keating EM, et al. Authorship in paediatric research conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries: parity or parasitism? Tropical Medicine and International Health 2017; 22: 1362–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cash‐Gibson L, Rojas‐Gualdrón DF, Pericàs JM, Benach J. Inequalities in global health inequalities research: a 50‐year bibliometric analysis (1966–2015). PLoS One 2018; 13: e0191901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Volmink J, Dare L. Addressing inequalities in research capacity in Africa. British Medical Journal 2005; 331: 705–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shuchman M, Wondimagegn D, Pain C, Alem A. Partnering with local scientists should be mandatory. Nature Medicine 2014; 20: 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mbaye R, Gebeyehu R, Hossmann S, et al. Who is telling the story? A systematic review of authorship for infectious disease research conducted in Africa, 1980–2016. British Medical Journal Global Health 2019; 4: e001855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ettarh R. Patterns of international collaboration in cardiovascular research in sub‐Saharan Africa. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa 2016; 27: 194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mêgnigbêto E. International collaboration in scientific publishing: the case of West Africa (2001–2010). Scientometrics 2013; 96: 761–83. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hedt‐Gauthier BL, Jeufack HM, Neufeld NH, et al. Stuck in the middle: a systematic review of authorship in collaborative health research in Africa, 2014–2016. British Medical Journal Global Health 2019; 4: e001853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naidoo AV, Hodkinson P, Lai King L, Wallis LA. African authorship on African papers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Medical Journal Global Health 2021; 6: e004612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boell SK, Cecez‐Kecmanovic D. A Hermeneutic approach for conducting literature reviews and literature searches. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 2014; 34: 257–86. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? European Journal of Clinical Investigation 2018; 48: e12931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pandey SC, Pattnaik PN. University research ecosystem: a conceptual understanding. Review of Economic and Business Studies 2015; 8: 169–81. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wellcome Trust . Africa and Asia: building strong research ecosystems. 2021. https://wellcome.org/what‐we‐do/our‐work/research‐ecosystems‐africa‐and‐asia (accessed 25/05/2021).

- 39. Jones CM, Ankotche A, Canner E, et al. Strengthening national health research systems in Africa: lessons and insights from across the continent. London: LSE Health; 2021. https://www.lse.ac.uk/lse‐health/assets/documents/research‐projects/HSR‐africa/Final‐report‐Strengthening‐NHRS‐in‐Africa‐lessons‐and‐insights‐2021.pdf (accessed 21/09/2021). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shiffman J. Global health as a field of power relations: a response to recent commentaries. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 2015; 4: 497–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khan M, Abimbola S, Aloudat T, Capobianco E, Hawkes S, Rahman‐Shepherd A. Decolonising global health in 2021: a roadmap to move from rhetoric to reform. British Medical Journal Global Health 2021; 6: e005604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shiffman J. Knowledge, moral claims and the exercise of power in global health. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 2014; 3: 297–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Costello A, Zumla A. Moving to research partnerships in developing countries. British Medical Journal 2000; 321: 827–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Council on Health Research for Development . Health Research: Essential Link to Equity in Development (1990 Commission Report). 1990. http://www.cohred.org/publications/open‐archive/1990‐commission‐report/ (accessed 21/09/2021).

- 45. Abimbola S. The foreign gaze: authorship in academic global health. British Medical Journal Global Health 2019; 4: e002068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Swiss Commission for Research Partnership with Developing Countries . Guidelines for research in partnership with developing countries. 1998. https://www.ircwash.org/resources/guidelines‐research‐partnership‐developing‐countries‐11‐principles (accessed 19/03/2021).

- 47. Afsana KHD, Hatfield J, Murphy J, Neufeld V. Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research. Promoting More Equity in Global Health Research and Better Health Worldwide. Partnership Tool Kit. 2009. https://www.elrha.org/wp‐content/uploads/2014/08/PAT_Interactive_e‐1.pdf (accessed 21/09/2021).

- 48. UK Collaborative on Development Research . Equitable Partnerships Resource Hub. https://www.ukcdr.org.uk/guidance/equitable‐partnerships‐hub/ (accessed 25/05/2021).

- 49. Essence on Health Research . Five keys to improving research costing in low‐ and middle‐income countries. 2012. https://www.who.int/tdr/publications/five_keys/en/ (accessed 28/03/2021).

- 50. Montreal Statement on Research Integrity in Cross‐Boundary Research Collaborations . 2013. https://wcrif.org/guidance/montreal-statement (accessed 19/03/2021).

- 51. Chu KM, Jayaraman S, Kyamanywa P, Ntakiyiruta G. Building research capacity in Africa: Equity and Global Health Collaborations. PLoS Medicine 2014; 11: e1001612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. National Institute for Health Research . Global Health Research Programmes ‐ Core Guidance. 2020. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/nihr‐global‐health‐research‐programmes‐stage‐2‐applications‐core‐guidance/24952#Equitable_and_Sustainable_Partnerships (accessed 24/02/2021).

- 53. Adegnika AA, Amuasi JH, Basinga P, et al. Embed capacity development within all global health research. British Medical Journal Global Health 2021; 6: e004692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smith E, Hunt M, Master Z. Authorship ethics in global health research partnerships between researchers from low or middle income countries and high income countries. BMC Medical Ethics 2014; 15: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gautier L, Sieleunou I, Kalolo A. Deconstructing the notion of "global health research partnerships" across Northern and African contexts. BMC Medical Ethics 2018; 19: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kerasidou A. The role of trust in global health research collaborations. Bioethics 2019; 33: 495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pratt B, Sheehan M, Barsdorf N, Hyder AA. Exploring the ethics of global health research priority‐setting. BMC Medical Ethics 2018; 19: 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kingori P, Gerrets R. The masking and making of fieldworkers and data in postcolonial Global Health research contexts. Critical Public Health 2019; 29: 494–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kingori P, Gerrets R. Morals, morale and motivations in data fabrication: medical research fieldworkers views and practices in two Sub‐Saharan African contexts. Social Science and Medicine 2016; 166: 150–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Madiega PA, Jones G, Prince RJ, Geissler PW. ‘She's My Sister‐In‐Law, My Visitor, My Friend’ – challenges of staff identity in home follow‐up in an HIV Trial in Western Kenya. Developing World Bioethics 2013; 13: 21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kingori P. Experiencing everyday ethics in context: frontline data collectors perspectives and practices of bioethics. Social Science and Medicine 2013; 98: 361–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Masina L. “A symbolic representation of life”: Behind Malawi’s blood‐sucking beliefs. African Arguments 2017. https://africanarguments.org/2017/11/09/a‐symbolic‐representation‐of‐life‐behind‐malawis‐blood‐sucking‐beliefs/ (accessed 05/06/2020).

- 63. Geissler PW, Pool R. Editorial: popular concerns about medical research projects in sub‐Saharan Africa–a critical voice in debates about medical research ethics. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2006; 11: 975–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. White L. Speaking With Vampires: Rumor and History in Colonial Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Janenova S. The boundaries of research in an authoritarian state. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2019; 18: 1609406919876469. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Evans L, Homer M. Academic journal editors' professionalism: perceptions of power, proficiency and personal agendas. Society for Research into Higher Education. 2014. https://srhe.ac.uk/wp‐content/uploads/2020/03/EvansHomerReport.pdf (accessed 21/09/2021).

- 67. Nafade V, Sen P, Pai M. Global health journals need to address equity, diversity and inclusion. British Medical Journal Global Health 2019; 4: e002018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bhaumik S, Jagnoor J. Diversity in the editorial boards of global health journals. British Medical Journal Global Health 2019; 4: e001909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Goyanes M, Demeter M. How the geographic diversity of editorial boards affects what is published in JCR‐ranked communication journals. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 2020; 97: 1123–48. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wu D, Lu X, Li J, Li J. Does the institutional diversity of editorial boards increase journal quality? The Case Economics Field. Scientometrics 2020; 124: 1579–97. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Crane D. The gatekeepers of science: some factors affecting the selection of articles for scientific journals. American Sociologist 1967; 2: 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Moher D, Galipeau J, Alam S, et al. Core competencies for scientific editors of biomedical journals: consensus statement. BMC Medicine 2017; 15: 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Garrow J, Butterfield M, Marshall J, Williamson A. The reported training and experience of editors in chief of specialist clinical medical journals. Journal of the American Medical Association 1998; 280: 286–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wilkes MS, Kravitz RL. Policies, practices, and attitudes of North American medical journal editors. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1995; 10: 443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Committee on Publication Ethics . Ghost, guest, or gift authorship in a submitted manuscript, 2021. https://publicationethics.org/resources/flowcharts‐new/changes‐authorship (accessed 14/06/2021).

- 76. Allen L, O’Connell A, Kiermer V. How can we ensure visibility and diversity in research contributions? How the Contributor Role Taxonomy (CRediT) is helping the shift from authorship to contributorship. Learned Publishing 2019; 32: 71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Glickman SW, McHutchison JG, Peterson ED, et al. Ethical and scientific implications of the globalization of clinical research. New England Journal of Medicine 2009; 360: 816–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 2009; 373: 1993–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Pratt B, Wild V, Barasa E, et al. Justice: a key consideration in health policy and systems research ethics. British Medical Journal Global Health 2020; 5: e001942. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bukusi EA, Manabe YC, Zunt JR. Mentorship and ethics in global health: fostering scientific integrity and responsible conduct of research. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2019; 100: 42–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Jones CM, Gautier L, Kadio K, et al. Equity in the gender equality movement in global health. Lancet 2018; 392: e2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shefer T, Shabalala N, Townsend L. Women and authorship in postapartheid psychology. South African Journal of Psychology 2004; 34: 576–94. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Obasi AI. Equity in excellence or just another tax on Black skin? Lancet 2020; 396: 651–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Abimbola S. The uses of knowledge in global health. British Medical Journal Global Health 2021; 6: e005802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Gotham D, Meldrum J, Nageshwaran V, et al. Global health equity in United Kingdom university research: a landscape of current policies and practices. Health Research Policy and Systems 2016; 14: 76‐. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Suber P. Ensuring open access for publicly funded research. British Medical Journal 2012; 345: e5184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Saha S, Afrad MMH, Saha S, Saha SK. Towards making global health research truly global. Lancet Global Health 2019; 7: e1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Reflexivity statement.