Abstract

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection affects >10% of the general population and is the leading cause of liver cirrhosis and cancer in West Africa. Despite current recommendations, HBV is often not tested for in clinical routine in the region. We included all people living with HIV (PLWH) in care between March and July 2019 at Fann University Hospital in Dakar (Senegal) and proposed hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) test to those never tested. All HBsAg‐positive underwent HIV and HBV viral load (VL) and liver stiffness measurement. We evaluated, using logistic regression, potential associations between patient characteristics and (a) HBV testing uptake; (b) HIV/HBV co‐infection among individual HBsAg tested. We determined the proportion of co‐infected who had HBV DNA >20 IU/ml on ART and sequenced HBV polymerase in those with HBV replication.of 1076 PLWH in care, 689 (64.0%) had never had an HBsAg test prior to our HBV testing intervention. Women and individuals >40 years old were less likely to have been previously tested. After HBV testing intervention,107/884 (12.1%) PLWH were HBsAg‐positive. Seven of 58 (12.1%) individuals newly diagnosed with HIV/HBV co‐infection had a detectable HBV VL, of whom five were HIV‐suppressed. Two patients on ART including 3TC and AZT as backbone showed the presence of the triple resistance mutation 180M/204I/80V. In this Senegalese urban HIV clinic, the majority of patients on ART had never been tested for HBV infection. One in ten co‐infected individuals had a detectable HBV VL despite HIV suppression, and 8% were not receiving a TDF‐containing regimen.

Keywords: hepatitis B, HIV, resistance, screening, sub‐Saharan Africa, testing

1. INTRODUCTION

Over 10% of people living with HIV (PLWH) in West Africa also have chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, the leading cause of liver cirrhosis and cancer in the region. 1 HIV infection has a profound impact on the natural history of HBV, including the acceleration of the progression to end‐stage liver disease and the increase in liver‐related mortality. 2 , 3 Tenofovir‐containing antiretroviral therapy (ART) leads to HBV viral suppression in more than 80% of HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals and reduces the progression of liver fibrosis and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). 4 , 5 , 6 Considering its clinical benefits and high genetic barrier to resistance, tenofovir, either as tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) or tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), should always be included in the ART regimen of HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals, provided there is no contraindication.

Despite international recommendations, the uptake of systematic HBV testing among PLWH has been generally poor in sub‐Saharan Africa. 7 This is problematic for several reasons: As tenofovir should be included in the ART regimen in the presence of HBV infection, knowledge of the individual hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) status is key in informing the prescription of optimal ART for each patient, including second‐line and third‐line treatment regimens. 8 HBV testing among PLWH is also required to identify those who will need a comprehensive liver disease assessment, including the measurement of liver fibrosis and HCC surveillance. In addition, the systematic testing for HBsAg allows health care providers to offer proper counselling on measures to reduce HBV transmission and screening of household members. 9

We aimed to investigate predictors of HBV testing among PLWH in care at a referral HIV outpatient clinic in Senegal and to evaluate their HBV infection status by implementing a simple and systematic HBV testing intervention. We hypothesized that detecting and characterizing HBV infection would allow the improvement of HBV management in this patient population.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study setting

We conducted a cross sectional study at the « Service des Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales/Centre Régional de Recherche et de Formation à la Prise en Charge clinique de Fann» (SMIT/CRCF), an urban adult HIV treatment centre in Dakar, Sénégal. This clinic has been one of the several referral centres for HIV management in Senegal since 1998. Since the publication of the first ART recommendations in 2002, Senegal has been adapting its recommendations in accordance with WHO protocols. Until 2013, recommended initial ART combined two nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), generally lamivudine (LAM) and zidovudine (AZT), and one non‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). In 2013 the Senegalese ART guidelines included the use of TDF alongside LAM or emtricitabine (FTC) as part of the preferred first‐line backbones, in line with WHO recommendations. 8 , 10 However, switching patients with virological suppression to a TDF‐based regimen was not a priority. As part of routine clinical care, all PLWH initiating ART undergo clinical and laboratory visits at day 1, 7, 14, 30, followed by quarterly visits. CD4 cell counts are measured every 6 months and HIV‐1 viral load (VL) annually. This study was part of a larger research programme, SEN‐B, which aims at evaluating the determinants of HBV ‘functional cure’ and liver‐related outcomes among HIV/HBV‐co‐infected and HBV mono‐infected individuals in Senegal.

2.2. Study participants and data

All PLWH in routine clinical care at the SMIT/CRCF as of January 2019 were considered for participation in the study. We used the centralized database from the Programme National de la Lutte contre le SIDA and medical records to identify the past availability of HBsAg test results. Individuals without a recorded HBsAg test result were identified and offered voluntary testing for HBV at the next scheduled follow‐up visit during the study period (March‐July 2019). The following data were retrieved from the clinical chart of all individuals: (a) demographic and clinical characteristics: age, sex, marital status, employment category, date of first positive HIV test, date of ART initiation and date and result of HBV, (b) stage of HIV disease: WHO stage, CD4+ cell counts and HIV‐1 VL, and prior AIDS defining illnesses; (c) treatment history: prior and current ART and reason for treatment changes (eg treatment failure, adverse events).

2.3. Study procedures and laboratory measurements

HBsAg testing was performed using a one‐step lateral flow assay rapid test (NOVATest®). NOVATest® (Atlas Link Biotech–ISO 13485) One‐Step Hepatitis B Virus Surface Antibody (HBsAg) Test Kit is a CE‐marked (CE 2265), rapid immunochromatographic in vitro assay for the detection of HBsAg in human serum samples. In a validation study in Senegal using the Elecsys® HBsAg II test (Cobas e‐411, Roche Diagnostics) as gold standard, the sensitivity of NOVATest® was 89.5% and its specificity 100%. 11 All individuals with a positive HBsAg test result between March and July 2019 were offered additional laboratory and transient elastography measurements, and samples were stored for viral sequencing. We performed HIV‐1 RNA (lower limit of detection 20 cp/ml) and HBV DNA (lower limit of detection 20 IU/ml) viral load quantification using a commercial assay (COBAS®Ampliprep Taqman 96, v2.0, Roche Diagnostics GmbH). HBV sequencing was performed in samples of patients with HBV DNA >20 IU/ml using previously published methodologies. 12 In brief, polymerase was amplified using specific primer sets and PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The Sanger‐sequencing reaction was outsourced to a commercial service provider (Microsynth AG). Additional laboratory measurements included aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), creatinine and CD4+ cell count. We defined ALT as being elevated if ALT >35 IU for men and >25 IU for women, according to AASLD recommendations. 13 If the HBsAg test was positive, the ART regimen was reviewed and replaced by a TDF‐containing combination if not already prescribed.

We measured liver fibrosis in all HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals using transient elastography (Fibroscan®, Echosens). Liver stiffness measurements (LSM) were performed by a single investigator who received manufacturer‐recommended training. Results were expressed as the median (kPa) and the interquartile range (IQR) of all valid measurements. LSM was considered reliable when it included >10 valid measurements with a success rate >60% and IQR/M ≤ 0.30. 14 Significant liver fibrosis (Metavir stages F2–F4) was defined as LSM > 7.1 kPa and cirrhosis (Metavir stage F4) as LSM > 11 kPa, as per WHO thresholds. 15

2.4. Data analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI), and continuous variables as median values with IQR. Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between individuals who had been previously tested and others using the Mann‐Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and Pearson chi–square (χ2) test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Logistic regression was used to evaluate potential associations between patient characteristics and (a) HBV testing uptake among all PLWH and (b) HBV infection status among individual who underwent HBsAg testing. Multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex and any other variable with a p‐value < 0.05 in univariable analyses.

2.5. Ethics

The study was approved by the Senegalese National Health Research Ethics Committee (CNERS) at the Health and Social Action Ministry of Senegal (0061/MSAS/DPRS/CNERS, 576/MSAS/DPRS/CNERS and PSS/BTMB/09611). All SEN‐B participants signed an informed consent.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Chronic hepatitis B virus testing during routine care

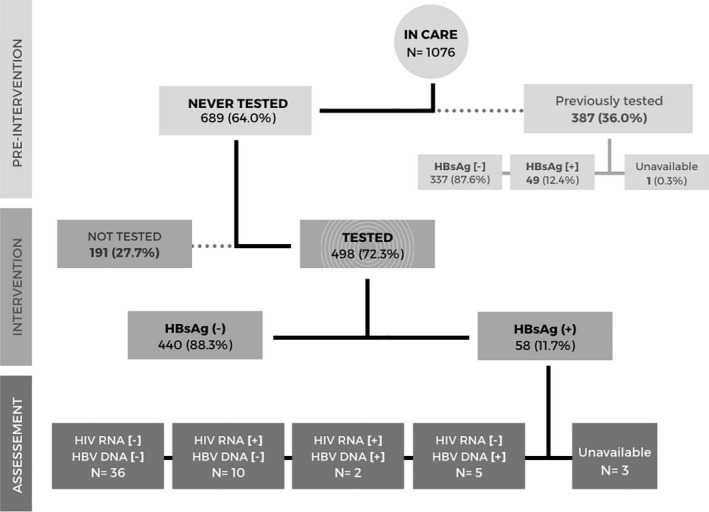

Of 1076 PLWH in care for a median of 5.6 years (IQR 2.3–10.6) at the time of the HBV testing intervention, 689 (64.0%) did not have a documented HBsAg test in the past (Figure 1). Among 387 individuals previously tested, 49 (12.4%) were co‐infected with HBV. Demographic and clinical characteristics of PLWH by HBsAg testing status are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Overall, 158/387 (41.0%) men and 229/689 (33.2%) women had been previously tested. In multivariable analysis, female patients (adjusted odds ratio (aOR: 0.70, 95% CI 0.50–0.98) and those aged >40 years (aOR: 0.55, 95% CI 0.39–0.78) were less likely to have been previously tested for HBV infection, whereas those who initiated ART after 2014 had increased odds of having a known HBV status (aOR: 2.96, 95% CI 2.12–4.15; Table 2 ).

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram. Abbreviations: HBsAg, hepatitis B virus antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; RNA, ribonucleic acid

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of PLWH, by HBsAg testing status

| Characteristics | HBsAg screening status | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Never tested n = 689 |

Previously tested n = 387 |

|||||

| Sex (n[%]) | Male | 227 | [33.0] | 158 | [40.8] | 0.02 |

| Female | 460 | [68.0] | 229 | [59.2] | ||

| Unknown | 2 | [0.3] | 0 | [0] | ||

| Age, years | Median (IQR) | 47 | [39–55] | 45 | [34–53] | <0.001 |

| Employment status (n[%]) | Employed | 468 | [84.8] | 299 | [77.3] | <0.001 |

| Student | 33 | [6.0] | 46 | [11.9] | ||

| Unemployed | 50 | [7.3] | 15 | [3.9] | ||

| Unknown | 138 | [20.0] | 27 | [7.0] | ||

| WHO stage at presentation (n[%]) | I–II | 228 | [33.1] | 152 | [39.3] | <0.001 |

| III–IV | 345 | [50.1] | 215 | [55.6] | ||

| Unknown | 116 | [16.8] | 20 | [5.1] | ||

| Period of ART initiation, years (n[%]) | 1998–2013 | 411 | [59.7] | 132 | [34.1] | <0.001 |

| 2014–2019 | 229 | [33.2] | 254 | [65.6] | ||

| Unknown | 49 | [7.1] | 1 | [0.3] | ||

| CD4 at ART initiation, cel/ul (n[%]) | <200 | 287 | [41.7] | 187 | [48.3] | <0.001 |

| 200+ | 165 | [24.0] | 129 | [33.3] | ||

| Unknown | 237 | [34.4] | 71 | [18.5] | ||

| Time on ART, years | Median (IQR) | 9,3 | [4.8–12.8] | 4,8 | [2.5–8.5] | <0.001 |

| ART line regimen (n[%]) | 1st line | 507 | [73.6] | 334 | [86.3] | <0.001 |

| 2nd/3rd line | 117 | [17.0] | 47 | [12.1] | ||

| Unknown | 65 | [9.4] | 6 | [1.6] | ||

Abbreviations: ART, Antiretroviral treatment; HBsAg, Hepatitis B virus surface antigen; IQR, interquartile range; WHO, world health organization.

TABLE 2.

Factors associated with HBV testing during routine HIV care

| n/N | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |||

| Sex | Male | 158/385 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.02 |

| Female | 229/689 | 0.72 (0.55–0.93) | 0.71 (0.54–0.94) | |||

| Age group, years | 18–40 | 149/339 | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.01 |

| >40 | 237/730 | 0.61 (0.47–0.80) | 0.69 (0.51–0.92) | |||

| WHO stage at presentation (n[%]) | I–II | 152/380 | 1.00 | 0.62 | ||

| III–IV | 215/560 | 0.79 (0.57–1.09) | ||||

| CD4 at ART initiation, cells/mm3 (n[%]) | <200 | 187/474 | 1.00 | 0.23 | ||

| 200+ | 129/294 | 1.19 (0.89–1.61) | ||||

| Period of ART initiation, years (n[%]) | 1998–2013 | 170/632 | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| 2014–2019 | 213/387 | 3.33 (2.55–4.34) | 3.02 (2.27–4.00) | |||

| ART line regimen | 1st line | 334/841 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.26 |

| 2nd/3rd line | 47/164 | 0.61 (0.42–0.88) | 0.80 (0.54–1.18) | |||

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral treatment; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; WHO, world health organization.

3.2. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic hepatitis B virus infection

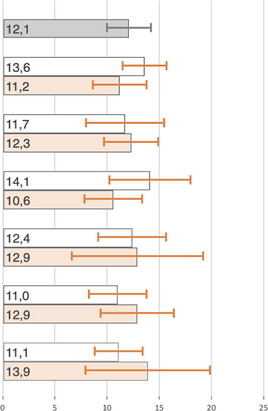

Of 689 previously untested patients, 498 (72.3%) underwent an HBsAg test during the HBV testing intervention. Reasons for not testing were the lack of availability of testing kits or reagents in the laboratory at time of the visit, unwillingness to participate in the study or not attending the follow‐up visit, among others. The main demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals who were not tested during our intervention were similar to those of patients who were tested: they were predominantly women (68% vs. 66% among those tested, p = 0.63), aged above 40 years old (69% vs. 72%, p = 0.67) and presenting with less than 200 CD4 cells/µl (45% vs. 40%; p = 0.01). During the HBV testing intervention, 58/498 (11.7%) PLWH had a positive HBsAg test. Thus, the overall prevalence of HBV infection among PLWH in care at our clinic was 12.1% (107 of 884, 95% CI 9.9–14.3). The prevalence of HIV/HBV‐co‐infection was marginally higher among male participants compared to woman (13.6% vs. 11.2%, p = 0.02), whereas estimates were similar across age categories (Table 3). In multivariable analyses no significant associations were found between potential explanatory variables and HBV infection (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Proportion of people living with HIV co–infected with HBV across sub‐groups

| Characteristics | HIV/HBV | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| n/N | (%; 95% CI) | |

| All | 107/884 |

|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 44/323 | |

| Female | 63/559 | |

| Age group, years | ||

| 18–40 | 33/281 | |

| >40 | 74/598 | |

| WHO stage at presentation | ||

| I–II | 43/304 | |

| III–IV | 49/463 | |

| CD4 at ART initiation, cel/ul | ||

| <200 | 48/386 | |

| 200+ | 30/238 | |

| Period of ART initiation, years | ||

| 1998–2013 | 53/481 | |

| 2014–2019 | 45/347 | |

| ART line regimen | ||

| 1st line | 76/688 | |

| 2nd/3rd line | 18/130 | |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral treatment; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; WHO, World Health Organisation.

TABLE 4.

Correlates for HIV/HBV co‐infection

| n/N | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |||

| Sex | Male | 44/323 | 1.00 | 0.3 | _ | |

| Female | 63/559 | 0.81 (0.53–1.22) | _ | |||

| Age group, years | 18–40 | 33/281 | 1.00 | 0.79 | _ | |

| >40 | 74/598 | 1.06 (0.61–1.81) | _ | |||

| WHO stage at presentation | I–II | 43/304 | 1.00 | 0.14 | _ | |

| III–IV | 49/463 | 0.60 (0.36–1.01) | _ | |||

| CD4 at ART initiation, cel/ul | <200 | 48/386 | 1.00 | 0.95 | _ | |

| 200+ | 18/153 | 0.98 (0.52–1.83) | _ | |||

| Period of ART initiation, years | 1998–2013 | 53/481 | 1.00 | 0.39 | _ | |

| 2014–2019 | 45/347 | 1.20 (0.79–1.84) | _ | |||

| ART line regimen initiation | 1st line | 76/688 | 1.00 | 0.36 | _ | |

| 2nd/3rd line | 18/130 | 1.29 (0.74–2.24) | _ | |||

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral treatment; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; WHO, World Health Organisation.

3.3. Biological and virological characterization of HIV/chronic hepatitis B virus ‐co‐infected individuals

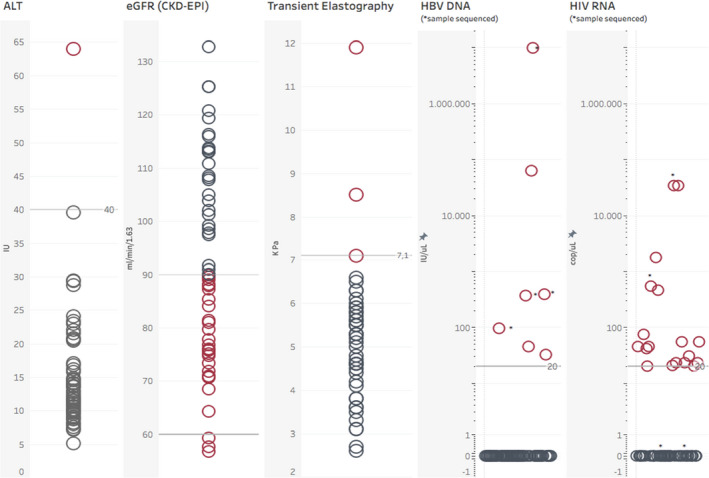

Among 58 individuals who had a newly positive HBsAg test during the HBV testing intervention, 55.2% were women and the median age was 46 years (IQR 39–54). These participants were on ART for a median cumulative time of 7.7 years (IQR 3.0–11.0) and 30% presented to HIV care after 2014, when TDF became available in Senegal. At the time of HBV testing intervention, 54 (93.1%) patients were on a TDF‐containing regimen. Overall, 28/55 (51%) co‐infected individuals (3 individuals had missing creatinine values) had an eGFR (CKD‐EPI formula) below 90 ml/min/1.73m2, including three with values below 60 ml/min. One individual had significant liver fibrosis and one liver cirrhosis, whereas only one participant had an elevated ALT value (Figure 2). Among the 58 HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals, 7 (12.1%) had a detectable HBV VL, of whom 5 were HIV‐suppressed (Figure 1, Figure 2). HBV viral suppression was achieved in 40/47 (85.1%) individuals on TDF‐containing ART and in 1/4 (25.0%) without TDF. HBV reverse trancriptase sequencing was successful in 4 of 5 HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals with HBV DNA >20 IU/ml, and showed the presence of the triple resistance mutation 180 M/204I/80V in two patients who were treated with lamivudine as the only HBV‐active drug (Table 5). The patients without resistance mutations were both on a TDF‐containing regimen and had never been exposed to lamivudine monotherapy for HBV infection.

FIGURE 2.

Liver, renal and virological assessment of HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals screened during the study. Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtrate rate; CKD‐EPI, chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration equation; HBV, hepatitis B virus; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; RNA, ribonucleic acid; IU, international units

TABLE 5.

HBV genotype and drug‐resistance patterns among HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals with HBV DNA viral load > 20 IU/ml during ART

| Patient(ID) | Sex | Age (years) | CD4 counts (cells/mm3) | Current ART | Time on ART (years) | Transient elastography (kPa) | ALT (IU) | HBV viral load (IU/ml) | HIV viral load (cop/ml) | HBV genotype | Resistance mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID 1 | M | 42 | _ | TDF 3TC EFV | 5.8 | 4.6 | 15 | 33 | < 20 | a | a |

| ID 2 | M | 52 | 213 | TDF 3TC EFV | 3.0 | 4.8 | 14 | 46 | < 20 | a | a |

| ID 3 | M | 54 | 399 | AZT 3TC LPV/r | 18.5 | 5.5 | 10 | 97 | 554 | A1 | L180 M–M204I–L80V |

| ID 4 | F | 36 | 336 | TDF 3TC NVP | 7.3 | 5.3 | 9 | 369 | 33.800 | A1 | none |

| ID 5 | F | 45 | 785 | AZT 3TC NVP | 12.1 | 3.1 | 16 | 386 | < 20 | E | L180 M–M204I–L80V |

| ID 6 | M | 54 | 444 | TDF 3TC EFV | 10.3 | 3.1 | 12 | 63.600 | < 20 | a | a |

| ID 7 | M | 60 | 321 | TDF 3TC LPV/r | 2.8 | 5.8 | 8 | > 10.000.000 | < 20 | E | none |

Abbreviations: 3TC, Lamivudine; ART, Antiretroviral treatment; EFV, Efavirenz; ETV, Entecavir; F, Female; HBV, Hepatitis B; ID, Identification; LdT, Telbivudine; LPV/r, Lopinavir/ritonavir; M, Male; NVP, Nevirapine; TDF, Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate. aSample non amplified.

4. DISCUSSION

In this urban HIV clinic in Senegal, approximately two thirds of PLWH had not been tested for the presence of HBV infection during routine clinical care. Although testing rates increased in recent years, they remained sub‐optimal, especially among women and older individuals. During a one‐off HBV diagnostic intervention, we screened 72% of individuals without a previous test and undertook a detailed characterization of HIV/HBV‐co‐infected participants. The overall prevalence of HBV infection was 12.1% in our cohort, and the estimate was similar across all sub‐groups. Of 58 newly diagnosed cases of HBV infection, one‐half had some degree of renal dysfunction, two patients had significant liver fibrosis or cirrhosis, and 12% had detectable HBV DNA levels. Two of four HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals who were receiving LAM as the only HBV‐active drug had developed significant drug resistance, which underlines the need for the systematic HBsAg testing of PLWH in sub‐Saharan Africa.

Despite the importance of HBV testing for the clinical management of individuals on ART, our study shows that even in tertiary care settings, HBV testing is not a priority in routine clinical care: only one third of PLWH on ART had been tested prior to our intervention and that proportion was lower in women and patients aged 40 and above. The observed gender disparity in access to HBV testing was consistent with previous findings from Zambia and Cameroun, where men were more likely to be HBsAg screened than women in primary and secondary care HIV clinics. 16 , 17 Given the risk of vertical transmission in women with poorly controlled HBV infection, HBV testing should especially be reinforced in women of childbearing age. 18 PLWH were more likely to be tested for HBV infection if enrolled into care after 2014, when Senegalese national guidelines adopted the WHO recommendations on HBV screening before ART initiation and the use of TDF as one of the recommended first‐line regimens. 8 , 10 As the number of PLWH on second‐line regimens is increasing in the region, it is crucial to identify those co‐infected with HBV to maintain TDF as a part of ART. 10 Lack of knowledge of HBV among health workers 19 , 20 as well as the lack of availability of reagents and limited funding for diagnostic tests by national programmes are some of the obstacles that need to be addressed in order to improve testing uptake in the region. 9

Over 90% of newly diagnosed co‐infected individuals in our study were on a TDF‐based regimen for at least 3 years. These estimates are higher than those from similar studies in Cameroon and the Gambia, where only 60.5% and 11.5% of co‐infected individuals were on TDF, most likely due to differences in the timing of roll‐out of TDF in first‐line ART across the region. 16 , 21 Despite the use of ART including TDF, 9% of co‐infected individuals had an HBV VL >20 IU/ml at the time of assessment, the majority being HIV‐suppressed. Our results are in line with those from a small prospective study in Ivory Coast: among 86 HIV/HBV‐co‐infected patients on TDF‐containing ART, 94.2% had a suppressed HBV VL after a median of 35 months. 22 Whereas it remains unclear why a minority of patients experiences continuous HBV replication on TDF despite HIV suppression, a number of risk factors have been described, including sub‐optimal treatment adherence, severe immunosuppression and HBeAg status at ART initiation. 23 Importantly, only two patients on long‐term TDF‐containing ART had a LSM compatible with significant liver fibrosis or cirrhosis in our study. These findings add to the increasing body of literature from SSA showing that potent HBV treatment is associated with a long‐term reduction in liver fibrosis progression among HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals. 5 , 24

Of four individuals newly diagnosed with chronic HBV infection who had never been exposed to TDF, two had HBV replication on a regimen including LAM and AZT. Sequencing of the polymerase showed the presence of LAM‐associated resistance mutations in both patients (one with genotype A1 and the other with genotype E). These findings underline the high likelihood of resistance development during LAM HBV monotherapy, as shown in previous studies in the region. In cohort analyses from Cameroun, Malawi and South Africa, the use of LAM without TDF was linked to the gradual emergence of resistance mutations in the HBV polymerase gene. 25 , 26 , 27 The proportion of individuals with detectable HBV VL on LAM monotherapy who developed resistance reached 88% in an HIV cohort from The Gambia. 20 Given the significant proportion of participants who were on a sub‐optimal ART regimen for HBV therapy and the related virological and clinical consequences, our data highlight the importance of the systematic HBsAg testing of all PLWH entering care and initiating ART.

The use of TDF has been associated with proximal renal tubulopathy, which is of special concern for HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals in SSA, given the lack of treatment alternatives. In one of the largest studies on renal function trajectories in PLWH in SSA to date, individuals on TDF were three times more likely to develop moderate or severe renal dysfunction compared to those on other NRTI, but the incidence of severe renal dysfunction events was low. 28 In our study, more than half of HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals showed some degree of renal dysfunction (eGFR < 90 ml/min/1.73m2) while on ART, but only 5% had an eGFR below 60 ml/min/1.73m2. HBV infection has been identified as a predictor of progressive renal impairment in PLWH. 29 In Zambia, PLWH co‐infected with HBV were twice as likely to have severe renal dysfunction as those who were HBV‐negative. 30 As life expectancy among African PLWH is increasing, their risk of developing cardio‐metabolic complications and associated renal dysfunction is higher. 31 Thus, data on long‐term renal outcomes from prospective cohorts of ageing PLWH co‐infected with HBV in SSA are urgently needed to inform future treatment guidelines and the potential benefit of replacing TDF by TAF. 32

Our study is among the first to provide comprehensive HBV virological data from HIV/HBV‐co‐infected individuals in West Africa, and illustrates how a simple diagnostic intervention can help improve the control of HBV infection in a busy urban HIV clinic. Unfortunately, we were unable to include one quarter of individuals without a previous HBsAg test, mainly due to logistical reasons. As the demographic characteristics of individuals not included in the study did not differ significantly from those of our participants, and given the stable prevalence of HBV infection across sub‐populations, we do not anticipate a significant selection bias. Given that our analysis of renal dysfunction relied on a single creatinine measurement, we were not able to differentiate acute from chronic renal injury and may have over‐estimated the true burden of renal impairment in our cohort. Finally, we may have under‐estimated the prevalence of HBV treatment failure with emerging drug resistance as we were not able to sequence the virus of each individual with detectable VL during ART.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In this urban West African referral HIV clinic, the majority of PLWH on ART never had an HBV test performed during routine care. Among newly diagnosed HBV‐co‐infected individuals, one in ten had a detectable HBV viral load despite HIV suppression, and 8% were not receiving a TDF‐containing regimen. Considering the increased risk of liver‐related complication in individuals with HBV replication and the beneficial impact of TDF on reducing their incidence, HBV testing should be performed routinely during HIV clinical care. The early diagnosis of HBV infection should trigger additional investigations, including the evaluation of liver fibrosis and the initiation of HCC screening among high‐risk patients. As the wider implementation of simple diagnostic interventions, such as HBsAg testing and reflex liver fibrosis evaluation, could help reduce liver‐related complications among PLWH in sub‐Saharan Africa, their feasibility and cost‐effectiveness should be urgently evaluated in large, prospective cohort settings.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no competing interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AR, JT and GW conceptualized and designed the research study. AR, JT, ON contributed to data collection and management. AR analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the SEN‐B study staff and patients at the SMIT/CRCF. Special thanks to Aminata Diallo, Khady Ndow, Ndeye Amy and Astou Ndiaye for operational assistance. Open Access Funding provided by Universitat Bern.

Ramírez Mena A, Tine JM, Fortes L, et al. Hepatitis B screening practices and viral control among persons living with HIV in urban Senegal. J Viral Hepat. 2022;29:60–68. 10.1111/jvh.13615

Funding information

This study was supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation Professorship grant. (PP00P3_176944 to Gilles Wandeler).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Leumi S, Bigna JJ, Amougou MA, Ngouo A, Nyaga UF, Noubiap JJ. Global burden of hepatitis B infection in people living with human immunodeficiency virus: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;71(11):2799–2806. 10.1093/cid/ciz1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nikolopoulos GK, Paraskevis D, et al. Impact of hepatitis B virus infection on the progression of AIDS and mortality in HIV‐infected individuals: a cohort study and meta‐analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(12):1763–1771. 10.1086/599110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thio CL, Seaberg EC, Skolasky R, et al. HIV‐1, hepatitis B virus, and risk of liver‐related mortality in the Multicenter Cohort Study (MACS). The Lancet. 2002;360:1921–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Price JC, Seaberg EC, Badri S, Witt MD, D'Acunto K, Thio CL. HIV Monoinfection is associated with increased aspartate aminotransferase‐to‐platelet ratio index, a surrogate marker for hepatic fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(6):1005–1013. 10.1093/infdis/jir885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vinikoor MJ, Sinkala E, Chilengi R, et al. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on liver fibrosis among human immunodeficiency virus‐infected adults with and without HBV coinfection in Zambia. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(10):1343–1349. 10.1093/cid/cix122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wandeler G, Mauron E, Atkinson A, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV/HBV‐coinfected patients on tenofovir therapy: Relevance for screening strategies. J Hepatol. 2019;71(2):274–280. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coffie PA, Egger M, Vinikoor MJ, et al. Trends in hepatitis B virus testing practices and management in HIV clinics across sub‐Saharan Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:706. 10.1186/s12879-017-2768-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection 2013. [updated 2013]. [PubMed]

- 9. Spearman CW, Afihene M, Ally R, et al. Hepatitis B in sub‐Saharan Africa: strategies to achieve the 2030 elimination targets. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(12):900–909. 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30295-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ngom NF, Faye MA, Ndiaye K, et al. ART initiation in an outpatient treatment center in Dakar, Senegal: a retrospective cohort analysis (1998–2015). PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0202984. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diakhaby M, Ndiaye M, Diop M, et al. Evaluation du test de diagnostic rapide NOVA utilisé pour rechercher l'antigène HBs de l'Hépatite B chez les donneurs de sang au centre hospitalier national mathlaboul fawzaini de touba. Int J Progressive Sci Technol. 2021;25(2):678–683. 10.52155/ijpsat.v25.2.2942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hirzel C, Wandeler G, Owczarek M, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in Switzerland: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:483. 10.1186/s12879-015-1234-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67(4):1560–1599. 10.1002/hep.29800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boursier J, Konaté A, Gorea G, et al. Reproducibility of liver stiffness measurement by ultrasonographic elastometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(11):1263–1269. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. WHO Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection 2015. [updated 2015]. [PubMed]

- 16. Liégeois F, Boyer S, Eymard‐Duvernay S, et al. Hepatitis B testing, treatment, and virologic suppression in HIV‐infected patients in Cameroon (ANRS 12288 EVOLCAM). BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):49. 10.1186/s12879-020-4784-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vinikoor MJ, Musukuma K, Munamunungu V, et al. Implementation of routine screening for chronic hepatitis B virus co‐infection by HIV clinics in Lusaka, Zambia. J Viral Hepatitis. 2015;22(10):858–860. 10.1111/jvh.12404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gueye SB, Diop‐Ndiaye H, Lo G, et al. HBV carriage in children born from HIV‐seropositive mothers in Senegal: the need of birth‐dose HBV vaccination. J Med Virol. 2016;88(5):815–819. 10.1002/jmv.24409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tine J, Diallo MB, Dabis F, et al. Prevention and care of hepatitis B in Senegal; awareness and attitudes of medical practitioners. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(2):389–395. 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Djaogol T, Coste M, Marcellin F, et al. Prevention and care of hepatitis B in the rural region of Fatick in Senegal: a healthcare workers' perspective using a mixed methods approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):627. 10.1186/s12913-019-4416-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ndow G, Gore ML, Shimakawa Y, et al. Hepatitis B testing and treatment in HIV patients in the Gambia—compliance with international guidelines and clinical outcomes. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179025. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boyd A, Moh R, Gabillard D, et al. Low risk of lamivudine‐resistant HBV and hepatic flares in treated HIV‐HBV‐coinfected patients from Côte d'Ivoire. Antivir Ther. 2015;20(6):643–654. 10.3851/IMP2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boyd A, Gozlan J, Maylin S, et al. Persistent viremia in human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis B coinfected patients undergoing long‐term tenofovir: virological and clinical implications. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):497–507. 10.1002/hep.27182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grant JL, Agaba P, Ugoagwu P, et al. Changes in liver stiffness after ART initiation in HIV‐infected Nigerian adults with and without chronic HBV. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(7):2003–2008. 10.1093/jac/dkz145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aoudjane S, Chaponda M, González del Castillo AA, et al. Hepatitis B virus sub‐genotype A1 infection is characterized by high replication levels and rapid emergence of drug resistance in HIV‐positive adults receiving first‐line antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(11):1618–1626. 10.1093/cid/ciu630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kouanfack C, Aghokeng AF, Mondain A‐M, et al. Lamivudine‐resistant HBV infection in HIV‐positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a public routine clinic in Cameroon. Antivir Ther. 2012;17(2):321–326. 10.3851/IMP1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lukhwareni A, Gededzha MP, Amponsah‐Dacosta E, et al. Impact of lamivudine‐based antiretroviral treatment on hepatitis B viremia in HIV‐coinfected South Africans. Viruses. 2020;12(6):634. 10.3390/v12060634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mulenga L, Musonda P, Mwango A, et al. Effect of baseline renal function on tenofovir‐containing antiretroviral therapy outcomes in Zambia. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(10):1473–1480. 10.1093/cid/ciu117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mocroft A, Neuhaus J, Peters L, et al. Hepatitis B and C co‐infection are independent predictors of progressive kidney disease in HIV‐Positive, antiretroviral‐treated adults. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40245. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mweemba A, Zanolini A, Mulenga L, et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus coinfection is associated with renal impairment among Zambian HIV‐infected adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(12):1757–1760. 10.1093/cid/ciu734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mtisi TJ, Ndhlovu CE, Maponga CC, Morse GD. Tenofovir‐associated kidney disease in Africans: a systematic review. AIDS Res Ther. 2019;16(1):12. 10.1186/s12981-019-0227-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Surial B, Béguelin C, Chave J‐P, et al. Brief report: switching From TDF to TAF in HIV/HBV‐coinfected individuals with renal dysfunction‐a prospective cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(2):227–232. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.