Abstract

There is no consensus on the optimal treatment duration of anti‐PD‐1 for advanced melanoma. The aim of our study was to gain insight into the outcomes of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, the association of treatment duration with progression and anti‐PD‐1 re‐treatment in relapsing patients. Analyses were performed on advanced melanoma patients in the Netherlands who discontinued first‐line anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy in the absence of progressive disease (n = 324). Survival was estimated after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation and with a Cox model the association of treatment duration with progression was assessed. At the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, 90 (28%) patients had a complete response (CR), 190 (59%) a partial response (PR) and 44 (14%) stable disease (SD). Median treatment duration for patients with CR, PR and SD was 11.2, 11.5 and 7.2 months, respectively. The 24‐month progression‐free survival and overall survival probabilities for patients with a CR, PR and SD were, respectively, 64% and 88%, 53% and 82%, 31% and 64%. Survival outcomes of patients with a PR and CR were similar when anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was not due to adverse events. Having a PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation and longer time to first response were associated with progression [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.81 (95% confidence interval, CI = 1.11‐2.97) and HR = 1.10 (95% CI = 1.02‐1.19; per month increase)]. In 17 of the 27 anti‐PD‐1 re‐treated patients (63%), a response was observed. Advanced melanoma patients can have durable remissions after (elective) anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation.

Keywords: advanced melanoma, anti‐PD‐1, discontinuation, immunotherapy, real‐world

Short abstract

What's new?

Reasons for discontinuing treatment with the anti‐PD‐1 antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab can vary significantly among melanoma patients. Moreover, the optimal treatment duration for these drugs remains unclear. In this observational study on anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, most patients with advanced melanoma who had complete or partial response at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation experienced ongoing response, with potential survival benefits. Shorter time to first response of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy and partial response at discontinuation were associated with later progression of disease. Elective discontinuation, by contrast, was linked to a reduced likelihood of subsequent progression. Anti‐PD‐1 retreatment exhibited clinical activity against melanoma, warranting further investigation.

Abbreviations

- AEs

adverse events

- BOR

best overall response

- CI

confidence interval

- CR

complete response

- DMTR

Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry

- HR

hazard ratio

- OS

overall survival

- PD

progressive disease

- PD‐1

programmed death 1

- PFS

progression‐free survival

- PR

partial response

- SD

stable disease

- ULN

upper limit of normal

1. INTRODUCTION

Anti‐PD‐1 antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab are effective and well‐tolerated immunotherapies for unresectable Stage IIIc/IV (advanced) melanoma with reported complete and partial response rates (CR, PR) of 12% to 19% and 23% to 24%, respectively. 1 , 2 A median overall survival (OS) of 37 months and 9% to 11% any grade treatment‐related adverse events (AEs) leading to discontinuation were observed in Phase III trials. 1 , 2 Early discontinuation of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy could be considered given the risk of AEs, the burden of hospital visits for patients, possible immune exhaustion, hospital capacity and financial costs for society. 3 , 4

There is no clear consensus on the optimal treatment duration of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy. The Checkmate‐153 showed that 1‐year fixed nivolumab treatment duration in non‐small cell lung cancer was associated with unfavourable outcomes. 5 For melanoma, the KEYNOTE‐001/006 trials and three observational studies showed high rates of ongoing responses after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation. 1 , 2 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Factors associated with progression after discontinuation were PR and treatment duration of less than 6 months in patients with a CR who discontinued anti‐PD1 monotherapy early. 8 However, conditions for anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation were different between these studies and, therefore, evidence is fragmented.

More evidence is needed on the optimal treatment duration of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy and conditions for discontinuation. Using a nationwide population‐based registry, 11 we analysed survival outcomes after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation in real‐world and the association of treatment duration with progression‐free survival (PFS).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and patients

For this observational study of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation in real‐world setting, data from the population‐based Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry (DMTR) were used. In 2013, advanced melanoma care in the Netherlands was centralised in 14 melanoma centres and the DMTR was founded for reimbursement and research purposes. The DMTR is a comprehensive nationwide registry in which all advanced melanoma patients in the Netherlands are followed from diagnosis until death. 11 DMTR data are prospectively collected by trained data‐managers and checked by medical oncologists. For the current study, patients had to fulfil the following inclusion criteria: age ≥ 18 years, diagnosed with advanced melanoma between 2014 and 2017, received first‐line anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy and anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation in the absence of progressive disease (PD). The timing of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was determined by joint decision of the patient and treating medical team after a multidisciplinary consultation meeting [consisting of medical oncologist(s), surgical oncologist(s), radiologist(s), pathologist(s) and radiotherapist(s)]. In the real‐world setting of melanoma care in the Netherlands, the response status was in general based on RECIST v1.1 criteria and assessed by the medical team. For clinical relevance, patients were stratified by response status at the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation [CR, PR and stable disease (SD)]. Subgroup analysis was conducted in patients who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy because of AEs and in patients who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy in the absence of AEs or PD (elective discontinuation). Patients with uveal melanoma were excluded from this study. Dataset cut‐off date was 8 August 2019.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Characteristics at the start of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy of patients with CR, PR and SD at the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation were compared using descriptive statistics. OS and PFS after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation were estimated with the Kaplan‐Meier method. Follow‐up time was estimated using the reverse Kaplan‐Meier method. 12 In addition to PFS, the probability of second‐line treatment after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was estimated with a cumulative incidence curve, in which death before second‐line treatment was a competing risk. 13 The association of response status at discontinuation and treatment duration with PFS was analysed with a Cox proportional hazards model. Treatment duration was split into the time from the start of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy to first response (PR or CR) and time from first response to anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation. This analysis was restricted to patients with CR or PR at discontinuation. PFS instead of OS was chosen as primary endpoint, because of the higher number of events and clinical relevance. Data handling and statistical analyses were performed with R (version 3.6.1.; packages tidyverse, car, survival, cmprsk).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics at the start of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy

From 2014 to 2017, 901 patients with advanced melanoma were treated with first‐line anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy, of whom 324 (36%) patients discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy in the absence of PD. At the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, 90 (28%) patients had a CR, 190 (59%) a PR and 44 (14%) SD. Compared to patients with PR or SD at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, patients with a CR were younger and more often had favourable disease stage, normal lactate dehydrogenase level and <3 organ sites with metastases (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics at start of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy stratified by response status at the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation

| Complete response (n = 90) | Partial response (n = 190) | Stable disease (n = 44) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (IQR) | 63 (54‐71) | 66 (58‐73) | 70 (58‐77) | .020 |

| Age categories | .161 | |||

| <50 y | 17 (18.9) | 26 (13.7) | 7 (15.9) | |

| 50‐59 y | 15 (16.7) | 32 (16.8) | 5 (11.4) | |

| 60‐69 y | 33 (36.7) | 58 (30.5) | 9 (20.5) | |

| >70 y | 25 (27.8) | 74 (38.9) | 23 (52.3) | |

| Female | 34 (37.8) | 76 (40.0) | 15 (34.1) | .756 |

| ECOG PS | .195 | |||

| 0 | 66 (76.7) | 126 (70.0) | 26 (60.5) | |

| 1 | 20 (23.3) | 43 (23.9) | 15 (34.9) | |

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | 9 (5.0) | 2 (4.7) | |

| ≥3 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 4 | 10 | 1 | |

| LDH level | .021 | |||

| Normal | 79 (87.8) | 136 (72.7) | 36 (83.7) | |

| 1× ULN | 11 (12.2) | 43 (23.0) | 7 (16.3) | |

| >2× ULN | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Stage | .076 | |||

| Unresectable IIIc | 8 (8.9) | 12 (6.3) | 3 (6.8) | |

| IV‐M1a | 18 (20.0) | 15 (7.9) | 3 (6.8) | |

| IV‐M1b | 14 (15.6) | 41 (21.7) | 10 (22.7) | |

| IV‐M1c | 50 (55.6) | 121 (64.0) | 28 (63.6) | |

| Metastases in ≥3 organ sites | 17 (18.9) | 66 (34.7) | 13 (29.5) | .025 |

| Liver metastasis | 11 (12.4) | 35 (18.5) | 12 (27.3) | .105 |

| Brain metastasis | .434 | |||

| Absent | 78 (87.6) | 159 (84.6) | 37 (86.0) | |

| Asymptomatic | 7 (7.9) | 15 (8.0) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Symptomatic | 4 (4.5) | 14 (7.4) | 5 (11.6) | |

| BRAF‐mutant | 35 (38.9) | 75 (39.5) | 17 (38.6) | .992 |

Note: Categorical variables were analysed with Chi‐square test and numerical variables with the unpaired t test. Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Missing data of less than 2.5% is not shown.

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; IQR, interquartile range; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal.

P value of statistical tests comparing characteristics of patients with a complete, partial response and stable disease at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation (excluding missing values).

3.2. Treatment characteristics

For patients with CR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, the most common reason for discontinuation was by joint decision between the patient and treating medical team (n = 67, 70%). In addition, seven (7.8%) patients with CR discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy because of AEs. Median treatment duration in patients with CR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was 11 months [interquartile range (IQR) = 9‐14; Table 2]. In 98 (52%) patients with PR, anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was by joint decision, whereas 61 (32%) patients discontinued anti‐PD‐1 because of AEs. Patients with PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation had a median treatment duration of 12 months (IQR = 7‐17). In patients with SD, AEs were the most frequently reported reason for anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation (n = 21, 48%), followed by joint decision (n = 15, 34%). Median treatment duration of patients with SD at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was 7 months (IQR = 3‐13).

TABLE 2.

Treatment characteristics of patients with CR, PR and SD at the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation

| Complete response (n = 90) | Partial response (n = 190) | Stable disease (n = 44) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total treatment duration | |||

| Median time; months (IQR) | 11.2 (8.5‐13.8) | 11.5 (7.3‐17.2) | 7.2 (3.4‐12.6) |

| ≥24 months of treatment | 2 (2.2) | 12 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Median treatment duration, months (IQR) | |||

| To first response (CR, PR or SD) | 2.8 (2.6‐2.8) | 2.7 (2.3‐2.8) | 2.7 (1.9‐2.8) |

| From first response to discontinuation | 7.8 (4.8‐10.9) | 8.1 (3.4‐12.7) | 5.3 (0.5‐10.2) |

| To best overall response a | 8.3 (5.5‐11.2) | 2.8 (2.7‐4.9) | 2.7 (1.9‐2.8) |

| From best overall response to discontinuation b | 1.1 (0.0‐4.9) | 8.1 (3.4‐12.7) | 5.3 (0.5‐10.2) |

| Best overall response | |||

| Complete response | 90 (100.0) | 48 (25.3) | 5 (11.4) |

| Partial response | 0 (0.0) | 142 (74.7) | 4 (9.1) |

| Stable disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (79.5) |

| Reason of discontinuation | |||

| Joint decision c | 63 (70.0) | 98 (51.6) | 15 (34.1) |

| Toxicity | 7 (7.8) | 61 (32.1) | 21 (47.7) |

| Patient's choice | 5 (5.6) | 7 (3.7) | 2 (4.5) |

| Other | 13 (14.4) | 22 (11.6) | 6 (13.6) |

| Unknown | 2 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

Note: Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; IQR, interquartile range; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Treatment duration to best overall response before anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation.

Treatment duration from best overall response to anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation.

Elective anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation after joint decision by the patient and medical team.

In patients with CR, PR and SD at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, median time from start of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy to first response was 2.8, 2.7 and 2.7 months, respectively (Table 2). Median time from start of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy to the best overall response (BOR) before anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was 8.3 months (IQR = 5.5‐11.2) for CR, 2.8 months (IQR = 2.7‐4.9) for PR and 2.7 months (IQR = 1.9‐2.8) for SD (Table 2). The median time from this BOR to anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was 1.1 months (IQR = 0‐4.9) for CR, 8.1 months (IQR = 3.4‐12.7) for PR and 5.3 months (IQR = 0.5‐10.2) for SD. In 48 (25.3%) patients with PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, CR as BOR after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was reported. Of patients with SD, 4 (9.1%) and 5 (11.4%) patients finally had PR and CR, respectively.

3.3. PFS after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation

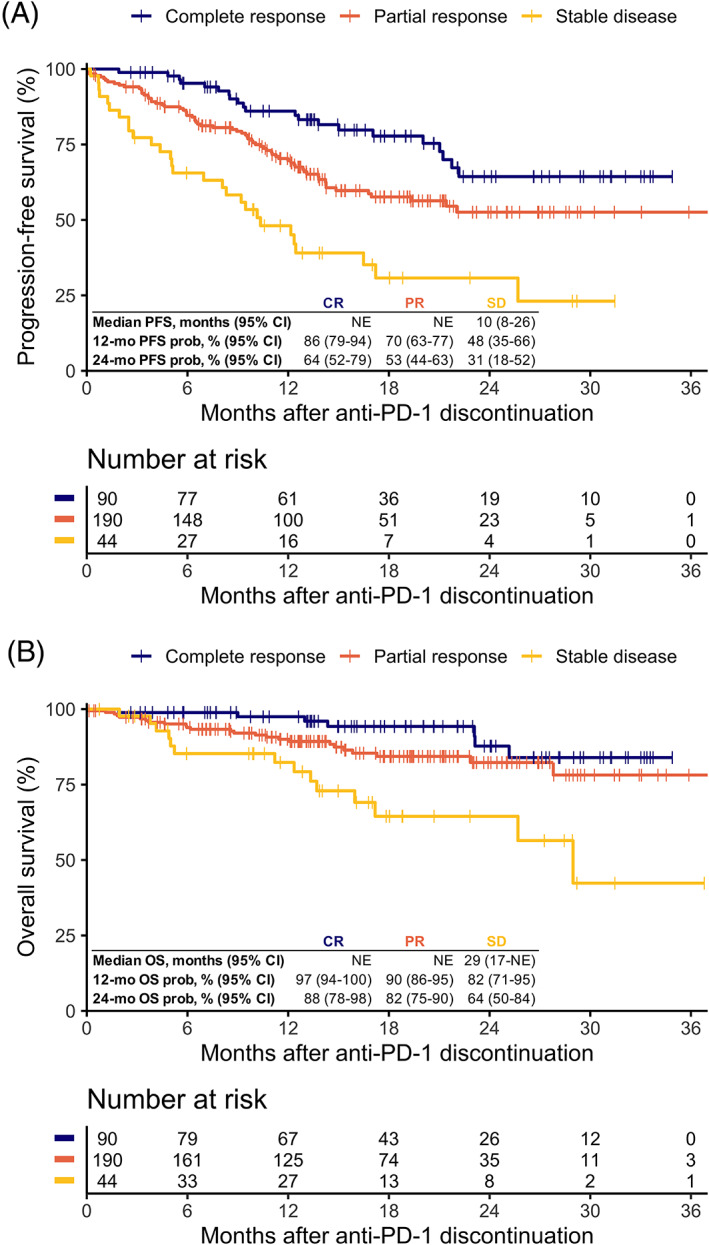

In patients with CR, PR and SD at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, median follow‐up time after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was 18, 16 and 17 months, respectively. Patients with CR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation had a 12‐month PFS probability after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation of 86% [95% confidence interval (CI) = 79‐94] and a 24‐month PFS probability of 64% (95% CI = 52‐79; Figure 1A). Patients with PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation had 12‐ and 24‐month PFS probabilities of 70% (95% CI = 63‐77) and 53% (95% CI = 55‐63), respectively. In patients with SD, the 12‐ and 24‐month PFS probabilities were 48% (95% CI = 35‐66) and 31% (95% CI = 18‐52), respectively. Median PFS for patients with a CR or PR was not reached and for patients with SD the median PFS was 10 months (95% CI = 8‐26; Figure 1A). Median time to progression after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was 5.1 months for SD, 7.5 months for PR and 9.5 months for CR.

FIGURE 1.

Off‐treatment survival outcomes of patients who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy by response status at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation. Kaplan‐Meier curves of off‐treatment (A) progression‐free survival (log‐rank P < .0001) and (B) overall survival after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation (log‐rank P < .001). CI, confidence interval; mo, months; NE, not estimable; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; prob, probability [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.4. OS after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation

The 12‐ and 24‐month OS probabilities for patients with CR were 97% (95% CI = 94‐100) and 88% (95% CI = 78‐98), respectively (Figure 1B). For patients with PR, the 12‐ and 24‐month OS probabilities were 90% (95% CI = 86‐95) and 82% (95% CI = 75‐90). The 12‐ and 24‐month OS probabilities of patients with SD were 82% (95% CI = 71‐95) and 64% (95% CI = 50‐84). Median OS for patients with CR or PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was not reached, whereas median OS in patients with SD was 29 months (95% CI = 17 to not estimable; Figure 1B).

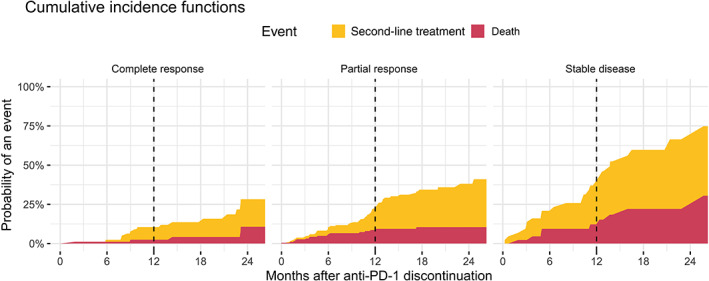

3.5. Second‐line treatment after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation

In the competing risks analysis, patients with CR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation had an 18‐month probability of being alive and not having received second‐line treatment after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation of 86% (95% CI = 75‐97; Figure 2). The 18‐month probability of second‐line treatment was 9.4% (95% CI = 2.7‐16) and of the competing risk death 4.2% (95% CI = 0‐9.0). Patients with PR had an 18‐month probability for being alive and not having received second‐line treatment of 66% (95% CI = 54‐78). For patients with PR, the 18‐month probability of second‐line treatment was 24% (95% CI = 17‐31) and of death before second‐line treatment 11% (95% CI = 5.6‐15; Figure 2). For patients with SD at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, the 18‐month probability for death before second‐line treatment was less favourable [22% (95% CI = 7.9‐36); Figure 2].

FIGURE 2.

Competing risks analysis of second‐line treatment from anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation by response status at discontinuation, with death as competing risk. The 12‐month probabilities of second‐line treatment and death before second‐line treatment following anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation were for complete response 8.0% (95% CI = 1.8‐14) and 2.5% (95% CI = 0‐5.9); partial response 15% (95% CI = 9.0‐20) and 8.7% (95% CI = 4.4‐13); stable disease 28% (95% CI = 13‐42) and 12% (95% CI = 2.0‐23). CI, confidence interval [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.6. Cox model for PFS

In the Cox proportional hazards model analysing patients with CR or PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, PR was associated with progression [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.81 (95% CI = 1.11‐2.97; P = .018); Table 3]. Longer time from start of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy to first reported PR or CR was also associated with progression [HR per month increase = 1.10 (95% CI = 1.02‐1.19; P = .009)]. The treatment duration from first reported PR or CR to anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was not associated with progression [HR = 0.98 (95% CI = 0.94‐1.02)]. HR of the total treatment duration was 0.99 (95% CI = 0.96‐1.02) per month increase.

TABLE 3.

Multivariable Cox model to assess the association of response status at the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation (restricted to CR and PR), time from the start of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy to first reported response and time from first response to anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation with progression‐free survival

| n | Events | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (months) | |||||

| Start anti‐PD‐1 to first response (PR or CR a ) | 277 | — | 1.10 | 1.02‐1.19 | .009 |

| First response to anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation | 277 | — | 0.98 | 0.94‐1.02 | .236 |

| Status at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation | |||||

| Complete response | 89 | 21 | 1 | ||

| Partial response | 188 | 68 | 1.81 | 1.11‐2.97 | .018 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; HR, hazard ratio; PR, partial response.

Whichever came first and not necessarily equal to the response status at the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation.

3.7. Elective discontinuation vs discontinuation because of AEs

In patients who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy in the absence of AEs or PD (ie, elective discontinuation), median treatment duration was 12 months (IQR = 8.9‐14), 13 months (IQR = 9.7‐23) and 11 months (IQR = 5.7‐16) in patients with CR, PR or SD at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, respectively. In patients with anti‐PD1 discontinuation because of AEs, the median treatment duration was shorter [CR: 6.9 months (IQR = 5.6‐9.0); PR: 7.2 months (IQR = 3.6‐12) and SD: 3.5 months (IQR = 0.9‐7.8)].

The 18‐month PFS and OS probabilities in patients with PR at elective discontinuation were higher [62% (95% CI = 53‐73) and 91% (95% CI = 85‐98)] compared to patients who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy because of AEs [48% (95% CI = 36‐64) and 72% (95% CI = 61‐85); Figure S1]. Survival differences were small between patients with SD or CR at discontinuation who electively discontinued anti‐PD‐1 and who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 because of AEs. The survival probabilities in patients with PR at elective discontinuation were similar to the survival probabilities in patients who had CR at elective discontinuation of anti‐PD‐1 (Figure S1). Except for patients discontinuing anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy because of AEs being younger, other baseline characteristics were not significantly different between patients discontinuing electively or because of AEs (Table S1). Survival outcomes of patients with SD at discontinuation were similar between patients who electively discontinued anti‐PD‐1 and those who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 because of AEs.

3.8. Re‐treatment with anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy

Twenty‐seven out of 87 patients (31%) with PD after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation were re‐treated with anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy. Of these re‐treated patients, 2 (6.7%) achieved CR, 6 (20%) PR and 9 (30%) patients had SD as BOR. Six (20%) patients had PD and in 4 (13%) patients response status was still unknown at dataset cut‐off. In patients with PD after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, BOR after re‐treatment with anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy was stratified by response status at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation shown in Figure 3. In the supplement, details of all second‐line systemic therapies in patients with PD after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation are described (Figures S2 and S3).

FIGURE 3.

Best overall response of re‐treatment with anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy in patients who relapsed after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation. CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease

4. DISCUSSION

In this real‐world study, the majority of advanced melanoma patients who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy with CR or PR experienced an ongoing response with promising OS. Longer time from start of anti‐PD‐1 treatment to first response and PR at discontinuation were both statistically significantly associated with progression after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation. Probability of progression after discontinuation was lower when anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy was electively discontinued. The median treatment duration was less than 12 months. Anti‐PD‐1 re‐treatment showed clinical activity, although results are preliminary. Anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation during SD seems less favourable, but still 31% had no disease progression 2 years after discontinuation.

The feasibility of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation has been investigated in different populations of melanoma patients with a tumour response. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 14 , 15 The KEYNOTE‐001 and ‐006 trials showed that advanced melanoma patients with CR, who completed 2 years of pembrolizumab or who were treated with pembrolizumab 6 months after a confirmed CR, had a 2‐year PFS probability of >80% from last dose of pembrolizumab. 6 , 7 Interestingly, the median treatment duration in the KEYNOTE‐001 was 2 years and in the KEYNOTE‐006, most patients (n = 103) completed 2 years of pembrolizumab. 6 , 7 The median treatment duration of patients who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 early (n = 23) was not reported. 7 Retrospective research in 185 unselected advanced melanoma patients who electively discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy (discontinuation in the absence of AEs or PD) showed similar results from last cycle of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy in patients with who achieved CR as a BOR. 8 In a large single centre retrospective study in 396 unselected advanced melanoma patients who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy for any reason (including AEs and PD), a 3‐year treatment failure free survival probability of 72% in patients with CR as BOR was observed. 9 However, survival times were estimated from BOR, which makes interpretation for daily practice difficult, because in clinical setting BOR is only known retrospectively. 9

Heterogeneity in aforementioned studies complicates a fair comparison of outcomes. Our study aimed to present clinically interpretable outcomes and avoid immortal time bias. This occurs when outcomes are analysed from diagnosis for groups whose membership patients only acquire some time after baseline, such as discontinuation with CR. We stratified outcomes by patients' reported CR, PR or SD at time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation estimating survival times after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation. This approach showed that in real‐world setting, which also included patients not represented in Phase III trials, the PFS was considerably lower than in aforementioned studies in patients with CR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 This may be due to the fact that we also included patients who discontinued treatment due to AEs and that more patients in our real‐world cohort had unfavourable patient and/or disease characteristics. In addition, patients who discontinued with CR were only treated for 1.1 months from BOR which could also have had an unfavourable effect on survival. 6 , 8 Despite lower PFS, the competing risks analysis for second‐line treatment indicated that patients could receive next‐line systemic treatment after PD with a promising OS. In line with previous studies, re‐treatment with anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy showed clinical activity in patients with CR or PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation and to a lesser extent also in patients with a SD. 7 , 8 , 9 , 15

The optimal treatment duration of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy in responders is still a matter of debate. In the KEYNOTE‐006 trial, the 2‐year PFS after treatment completion was similar to patients with CR who had been treated for at least 6 months, but who discontinued pembrolizumab early. 7 In the CheckMate‐153, however, nivolumab discontinuation after 1 year of treatment showed unfavourable OS and PFS compared to continuous nivolumab treatment for metastatic non‐small cell lung cancer. 5 This randomised study on early nivolumab discontinuation raises questions on the feasibility of early anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation. However, melanoma is a different disease, patients in the CheckMate‐153 had failed to prior treatment before they were exposed to nivolumab and a 1‐year fixed nivolumab treatment duration was chosen regardless of response status. Further analysis of the nivolumab group that discontinued after 1 year would have been interesting, because it is not known how to select patients eligible for early discontinuation of anti‐PD‐1 treatment. Other factors relevant for early and safe anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation may be duration and deepness of response combined with favourable patient and disease characteristics. The <12 months median treatment duration in our cohort and the association of shorter time to first anti‐PD‐1 response with favourable PFS suggests that anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy can be discontinued before 2 years in some cases.

Jansen et al 8 found that treatment duration of <6 months in patients with CR as BOR before anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was associated with a higher probability of progression. 8 Betof Warner et al 9 found no association between time until CR and treatment failure after CR. Unfortunately, the association of the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation with PD was not analysed. Our study adds that outcomes after anti‐PD1 discontinuation of patients with an early first response are favourable. Studies have shown that responders to anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy have changes in tumour microenvironment within 2 weeks after treatment initiation. 16 , 17 However, there is no literature on whether an early response is associated with the durability of the response. Thus, the evidence to date suggests that early responders have favourable outcomes and could be treated for a shorter duration with anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy.

As compared to CR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was associated with progression after discontinuation. 8 , 18 Most CRs initially start as a PR, 1 , 6 but it is impossible to determine whether patients with PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation who relapsed would have achieved CR if anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy was continued. Conversely, it is also impossible to determine whether patients with a CR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation would have achieved a durable CR if treatment was discontinued during PR. We observed in our cohort that 25% of patients with a PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation achieved CR as BOR. This may provide evidence that there is an ongoing immune response after anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation, but may also be due to the difference in (or delay of) radiological and pathological response. 19 An interesting treatment strategy to investigate is whether anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy can be discontinued upon first confirmed PR or CR. Relapsing patients can be re‐treated with anti‐PD‐1 based therapy and continued until a better and durable response occurs. In this way, the best responders can be treated shorter and experience less toxicity. The currently running ‘Safe Stop Trial’ investigates whether this is a safe and effective strategy (Netherlands Trial Register – Trial NL7293). 20 Another trial on anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation is the PET‐STOP trial (NCT04462406) in which discontinuation is guided by positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging and tumour biopsy.

In addition, we observed that patients who electively discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy (discontinuation in the absence of AEs or PD) had favourable survival compared to patients who discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy because of AEs. The survival of patients with PR who electively discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy even matched the survival of patients with CR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation. Previous research of patients treated with immunotherapy showed that grade ≥ 3 AEs were positively associated with OS. 21 Poor survival of patients who discontinued due to AEs may be due to shorter treatment duration rather than AEs if there is a minimum treatment duration for anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy to be effective. Having the ability to electively discontinue anti‐PD‐1 treatment at any given moment may, in real‐world, result in effective timing of discontinuation based on sustained response to anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy.

There are limitations to this observational study and its retrospective design. The unanswerable question that remains is whether the OS in patients with a CR or PR at anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation would have been even better if treatment had not been discontinued. Uncertainty remains as to whether (early) anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation is at the expense of OS.

Another important limitation is that our study was not performed in a controlled setting. In all melanoma centres, the response status reported was not strictly based on RECIST v1.1, but on (clinical) judgement by the medical team. Use of RECIST v1.1 (which was developed for use in clinical trials) in real‐world as the sole measure of disease assessment is not completely feasible, because of the difference between pathological and radiological response and its labour‐intensiveness. 19 , 22 In our study, this may have led to heterogeneity in ‘deepness’ of PR. Based on the survival outcomes, patients with PR whom electively discontinued anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy may have had a deeper and above all clinically relevant PR. We assume that the results of our study are generalisable to daily clinical practice, because in the real‐world setting, in addition to radiological evaluation, clinical judgement is crucial.

Another consequence of the uncontrolled real‐world setting was that the decision for anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation was not protocolised between hospitals. In some melanoma centres, patients may be treated longer while having CR or PR than in other melanoma centres. Therefore, our study does not answer what the minimal (or optimal) treatment duration after first response is. We also could not create evidence for what the optimal conditions for anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation were, because patient and disease characteristic at the time of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation were not available in the DMTR.

Despite that this is the largest population‐based cohort, the cohort size did not permit us to genuinely correct for all confounding factors. Patients with CR had favourable characteristics at the start of anti‐PD‐1 treatment, which could explain favourable outcomes. However, it is questionable whether correction for confounding factors is useful when interpreting response status as a predictor. Also due to the small number of patients receiving re‐treatment with anti‐PD‐1 and short follow‐up, conclusions cannot yet be drawn on the effectiveness of anti‐PD‐1 re‐treatment.

To our knowledge, this is the largest population‐based study on anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation with nationwide data. We believe that our study delivers clinically interpretable and relevant results for discontinuation of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy in responders that are generalisable to daily clinical practice. We showed that a durable response is possible after discontinuation of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy when a CR or PR is achieved. To a lesser extent, this also holds for SD. CR at discontinuation, shorter time to first response and the absence of AEs necessitating treatment discontinuation were important factors for favourable off‐treatment survival outcomes. For now, these factors and previous results on minimum treatment duration can be used to consider anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation in individual patients. Further randomised studies are warranted to determine the optimal timing of anti‐PD‐1 discontinuation and/or treatment duration of anti‐PD1 monotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Alfons J. M. van den Eertwegh has received study grants for Sanofi, Roche, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, TEVA, Idera; travel expenses from MSD Oncology, Roche, Pfizer, Sanofi; speaker honoraria from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis; advisory relationships with Bristol‐Myers Squibb, MSD Oncology, Amgen, Roche, Novartis, Sanofi, Pfizer, Ipsen, Merck and Pierre Fabre. Jan‐Willem B. de Groot has advisory relationships with Bristol‐Myers Squibb, MSD, Pierre Fabre, Servier. Geke A. P. Hospers has advisory relationships with MSD, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novartis; received research grant from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Seerave. Karijn P. M. Suijkerbuijk has advisory relationships with Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, MSD, Pierre Fabre, Abbvie; received honoraria from MSD, Roche and Novartis. Astrid A.M. van der Veldt has consultancy relationships with Bristol‐Myers Squibb, MSD, Merck, Eisai, Sanofi, Pfizer, Novartis, Ipsen, Roche. John B. A. G. Haanen has advisory relationships with Achilles Tx, BioNTech, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Immunocore, MSD, Merck Serono, Molecular Partners, Novartis, Pfizer, PokeAcel, Roche, Sanofi, T‐Knife, Third Rock Ventures, Neogene Tx (including stock options); received research grants from Asher Bio, Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, BioNTech, MSD, Novartis. Maureen J. B. Aarts has advisory relationships with Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, MSD, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi, Pfizer, Ipsen, Merck, Astellas; received research grants from Pfizer. All grants/fees were not related to this article and paid to the institutions. The funders had no role in the writing of this article or decision to submit it for publication. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

In compliance with Dutch regulations, the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry was approved by the medical ethical committee and was not subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting information

van Zeijl MCT, van den Eertwegh AJM, Wouters MWJM, et al. Discontinuation of anti‐PD‐1 monotherapy in advanced melanoma—Outcomes of daily clinical practice. Int. J. Cancer. 2022;150(2):317-326. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33800

Funding information For the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry (DMTR), the Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing foundation received a start‐up grant from governmental organisation The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW, grant number 836002002). The DMTR is structurally funded by Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novartis and Roche Pharma. Roche Pharma stopped and Pierre Fabre started funding of the DMTR in 2019. For this work, no funding was granted

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data that are minimally required to replicate the outcomes of the study will be made available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ascierto PA, Long GV, Robert C, et al. Survival outcomes in patients with previously untreated BRAF wild‐type advanced melanoma treated with nivolumab therapy: three‐year follow‐up of a randomized phase 3 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:187‐194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival results of a multicentre, randomised, open‐label phase 3 study (KEYNOTE‐006). Lancet. 2017;390:1853‐1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bantia S, Choradia N. Treatment duration with immune‐based therapies in cancer: an enigma. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verma V, Sprave T, Haque W, et al. A systematic review of the cost and cost‐effectiveness studies of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waterhouse DM, Garon EB, Chandler J, et al. Continuous versus 1‐year fixed‐duration nivolumab in previously treated advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: CheckMate 153. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3863‐3873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robert C, Ribas A, Hamid O, et al. Durable complete response after discontinuation of pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1668‐1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robert C, Ribas A, Schachter J, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE‐006): post‐hoc 5‐year results from an open‐label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1239‐1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jansen YJL, Rozeman EA, Mason R, et al. Discontinuation of anti‐PD‐1 antibody therapy in the absence of disease progression or treatment limiting toxicity: clinical outcomes in advanced melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1154‐1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Betof Warner A, Palmer JS, Shoushtari AN, et al. Long‐term outcomes and responses to retreatment in patients with melanoma treated with PD‐1 blockade. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1655‐1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pokorny R, McPherson JP, Grossmann KF, et al. Clinical outcomes with early‐elective discontinuation of PD‐1 inhibitors (PDi) at one year in patients (pts) with metastatic melanoma (MM). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:10048. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jochems A, Schouwenburg MG, Leeneman B, et al. Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry: quality assurance in the care of patients with metastatic melanoma in the Netherlands. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:156‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schemper M, Smith TL. A note on quantifying follow‐up in studies of failure time. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:343‐346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Putter H, Fiocco M, Gekus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risk and multi‐state models. Stat Med. 2007;26:2389‐2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Topalian SL, Sznol M, McDermott DF, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long‐term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1020‐1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Long GV, Schachter J, Ribas A, et al. 4‐year survival and outcomes after cessation of pembrolizumab (pembro) after 2‐years in patients (pts) with ipilimumab (ipi)‐naive advanced melanoma in KEYNOTE‐006. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:9503. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rashidian M, LaFleur MW, Verschoor VL, et al. Immuno‐PET identifies the myeloid compartment as a key contributor to the outcome of the antitumor response under PD‐1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:16971‐16980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vilain RE, Menzies AM, Wilmott JS, et al. Dynamic changes in PD‐L1 expression and immune infiltrates early during treatment predict response to PD‐1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5024‐5033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gauci ML, Lanoy E, Champiat S, et al. Long‐term survival in patients responding to anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1 therapy and disease outcome upon treatment discontinuation. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:946‐956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rozeman EA, Menzies AM, van Akkooi ACJ, et al. Identification of the optimal combination dosing schedule of neoadjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma (OpACIN‐neo): a multicentre, phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:948‐960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mulder EEAP, de Joode K, Litière S, et al. Early discontinuation of PD‐1 blockade upon achieving a complete or partial response in patients with advanced melanoma: the multicentre prospective Safe Stop trial. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verheijden RJ, May AM, Blank CU, et al. Association of anti‐TNF with decreased survival in steroid refractory ipilimumab and anti‐PD1‐treated patients in the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2268‐2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228‐247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting information

Data Availability Statement

Data that are minimally required to replicate the outcomes of the study will be made available upon reasonable request.