Abstract

The study aimed to investigate the efficacy of PCV-VG combined with individual PEEP during laparoscopic surgery in the Trendelenburg position. 120 patients were randomly divided into four groups: VF group (VCV plus 5cmH2O PEEP), PF group (PCV-VG plus 5cmH2O PEEP), VI group (VCV plus individual PEEP), and PI group (PCV-VG plus individual PEEP). Pmean, Ppeak, Cdyn, PaO2/FiO2, VD/VT, A-aDO2 and Qs/Qt were recorded at T1 (15 min after the induction of anesthesia), T2 (60 min after pneumoperitoneum), and T3 (5 min at the end of anesthesia). The CC16 and IL-6 were measured at T1 and T3. Our results showed that the Pmean was increased in VI and PI group, and the Ppeak was lower in PI group at T2. At T2 and T3, the Cdyn of PI group was higher than that in other groups, and PaO2/FiO2 was increased in PI group compared with VF and VI group. At T2 and T3, A-aDO2 of PI and PF group was reduced than that in other groups. The Qs/Qt was decreased in PI group compared with VF and VI group at T2 and T3. At T2, VD/VT in PI group was decreased than other groups. At T3, the concentration of CC16 in PI group was lower compared with other groups, and IL-6 level of PI group was decreased than that in VF and VI group. In conclusion, the patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery, PCV-VG combined with individual PEEP produced favorable lung mechanics and oxygenation, and thus reducing inflammatory response and lung injury.

Clinical Trial registry: chictr.org. identifier: ChiCTR-2100044928

Keyword: Pressure-controlled ventilation-volume guaranteed mode, Individualized PEEP, Lung protection, Laparoscopic surgery, Trendelenburg position

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery has been widely adopted in different surgery fields, due to its advantages such as minimal incision, less stress response and fewer blood loss. During laparoscopic surgeries, CO2 pneumoperitoneum combined with Trendelenburg position is commonly used to provide adequate exposure of surgical viewing and space. However, these methods have a major impact on the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems such as mean arterial pressure increased, increased Ppeak and decreased pulmonary compliance, and increases the risk of atelectasis or barotrauma because of abdominal content to move toward the head and forcing the diaphragm to elevate [1]. Moreover, increased airway pressure or excessive tidal volume may do harm to alveolar epithelial cells during mechanical ventilation, which leads to the destruction of lung parenchyma [2]. Above effects may produce serious consequences especially in patients with morbid obese or chronic lung disease [3]. Therefore, it is necessary to seek for appropriate lung-protective ventilation strategies to reduce cardiopulmonary complications for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery in Trendelenburg position.

Although the volume-controlled ventilation (VCV) is commonly used in general anesthesia, it is still reported to cause volutrauma, barotrauma and uneven gas distribution in the lungs due to offering a high airway pressure [4]. Pressure-controlled ventilation (PCV) achieves the desired tidal volume (VT) at lower airway pressure delivered by a decelerating flow. However, it leads to unfixed minute ventilation [5] and provokes lung injury due to a tractive force on alveoli [6]. PCV-VG, a relatively innovative ventilation mode, has recently been introduced in the field of anesthesiology. It has the features of VCV and PCV, which delivers a target VT with a decelerating airflow, reduces high airway pressure-induced airway and alveolar damage and ensures effective alveolar ventilation according to the patient’s lung compliance [7, 8]. In recent years, many researches have shown that PCV-VG provides lower airway pressure and better lung mechanics and exerts a huge potential lung-protective effect in various fields [8–10]. Additionally, numerous studies also showed that lung mechanics and gas exchange can be improved by the application of PEEP [10–13]. However, it was unreasonable to apply a fixed PEEP for all patients, and it is critical to determine individualized PEEP by the "titration method" to stabilize the lung function and minimize lung injury, thereby contributing to preferable physiologic and lung-protective effects [10, 14]. The optimal PEEP titration determined by Cdyn is relatively simple and practical, which has been proven to reduce the incidence of postoperative respiratory complications (PPCs) in patients with abdominal surgery [13].

Our previous research had shown that the ventilation strategy of PCV-VG plus individualized PEEP during one-lung ventilation exerted lung-protective effects, as indicated by improved respiratory mechanics, favorable ventilation efficiency and reduced inflammation response [10]. Nevertheless, whether the application of PCV-VG together with individualized PEEP can provide the lung-protective effect in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery in the Trendelenburg position is unclear. In this randomized study, we investigated the efficacy of PCV-VG together with individualized PEEP on lung mechanics, oxygenation parameters and lung injury in patients underwent laparoscopic surgery in the Trendelenburg position.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Trial of Hebei General Hospital, China (ethics approval no.2019–48) and performed at the department of anesthesiology from September 2020 to February 2021. Each patient or family member signed informed consent. The clinical trial registration number was ChiCTR2100044928. The trial enrolled 140 patients with ASA I-III who underwent laparoscopic surgery in Trendelenburg position. Of these, 20 patients were excluded and a total of 120 patients completed the study. Before the operation, patients with morbid obesity (body mass index > 30 kg/m2), hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg), bradycardia (heart rate < 60 bpm), cardiologic disease, hypoxia (PaO2 < 60 mmHg or SpO2 < 90%), chronic pulmonary disease or lung infection were excluded. Patients who were younger than 20 years or older than 70 years were also excluded. Dropout criteria were a conversion in type of surgery procedure to laparotomy, intraoperative blood transfusion, CO2 pneumoperitoneum duration < 60 min or > 180 min. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to one of four group using a computerized randomization table by an investigator who was blinded to the group assignment.

Anesthesia and surgery

After entering the operating room, all patients were monitored by electrocardiograpgy (ECG), heart rate (HR), blood pressure, pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) and bispectral index (BIS). All patients underwent radial artery puncture and catheterization were performed to check the blood gases and continuous hemodynamic monitoring. The anesthesia was performed by the same anesthesiologist. Before induction, all patients were preoxygenated with 100% oxygen for at least 3 min. Tracheal intubation was completed after intravenous injection of etomidate 0.3 mg/kg, sufentanil 0.3 μg/kg, cis-atracurium 0.15 mg/kg and midazolam 0.05 mg/kg. Anesthesia was maintained by continuous intravenous remifentanil and propofol infusion, sevoflurane inhalation and intermittent administration of cis-atracurium to maintain the BIS at 40 to 60.

Ventilation protocol

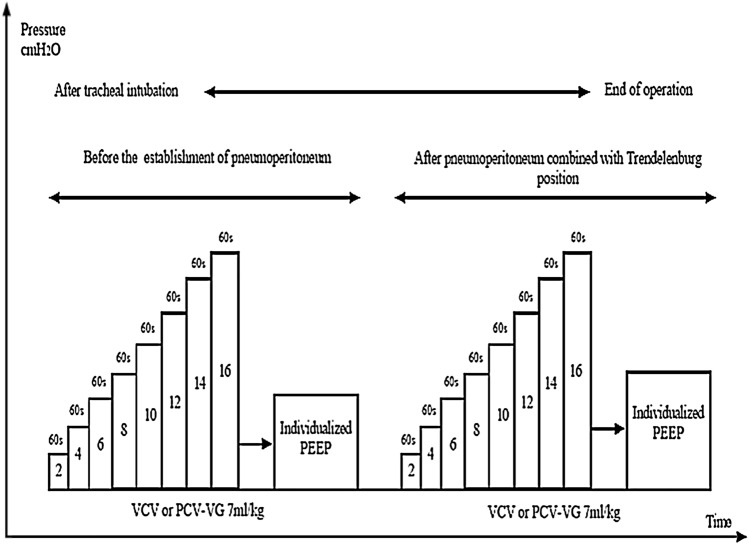

After intubation, all patients in the four groups were ventilated with an anesthesia ventilator (Avance CS2 Pro; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The intraperitoneal pressure was adjusted to 12 ± 2 mmHg with CO2 insufflation, and then 30°Trendelenburg position was set up. Before surgery, all participants were set the same ventilation parameters, consisting of a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 0.8, VT of 7 mL/kg PBW, and an initial PEEP of 5 cmH2O, which was maintained in the VF and PF group throughout the whole procedure. The I:E ratio was 1:2 and respiratory rate (RR) was adjusted to maintain PETCO2 of 35 ± 5 mmHg. The PBW was calculated according to a predefined formula:50 + 0.91 × (centimeters of height-152.4) for men and 45.5 + 0.91 × (centimeters of height-152.4) for women. The incremental PEEP titration [14] was performed two times in VI and PI group. In both groups, the first incremental PEEP titration was performed immediately after intubation, and the individualized PEEP level was set and maintained until the establishment of pneumoperitoneum. The second incremental PEEP titration was performed after the establishment of pneumoperitoneum together with Trendelenburg position, and the individualized PEEP level was set and maintained until the end of pneumoperitoneum together with Trendelenburg position. Also, patients received the individualized PEEP level of the first PEEP titration from the end of pneumoperitoneum together with Trendelenburg position until extubation. The PEEP titration method was as follows (Fig. 1): PEEP was progressively increased by 2 cmH2O steps from ZEEP up to 16 cmH2O, and each PEEP level was kept for 1 min before measuring Cdyn. The individualized PEEP was considered when the greatest Cdyn was produced.

Fig. 1.

Study protocol of the incremental PEEP titration procedure directed by Cdyn in patients of the VI and PI group

Measurements

Researched variables were measured as follows: Blood gas analysis data, PETCO2, PEEP, Ppeak, Pmean, Cdyn, PaO2/FiO2, A-aDO2, VD/VT and Qs/Qt at T1: in the supine position 15 min after the induction of anesthesia, T2: 60 min after CO2 pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg position, and T3: 5 min after placement in the supine position at the end of anesthesia.

Parameters were calculated using the following equations:

The serum concentration of CC-16 and IL-6 in T1 and T3 was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Postoperative complications (WBC count, cough, expectoration and fever) in the four groups were recorded during the first 3 days after operation.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS Inc.). Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR). Normal distribution data were analyzed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data with a normal distribution were compared among the four groups using one-way ANOVA with LSD-t as the post hoc test. Continuous variables with a nonnormal distribution in multiple groups were analyzed by the Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables are described as numbers and were analyzed using the chi-squared test. p-values were two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant difference.

Results

Patients enrollment and intraoperative characteristics

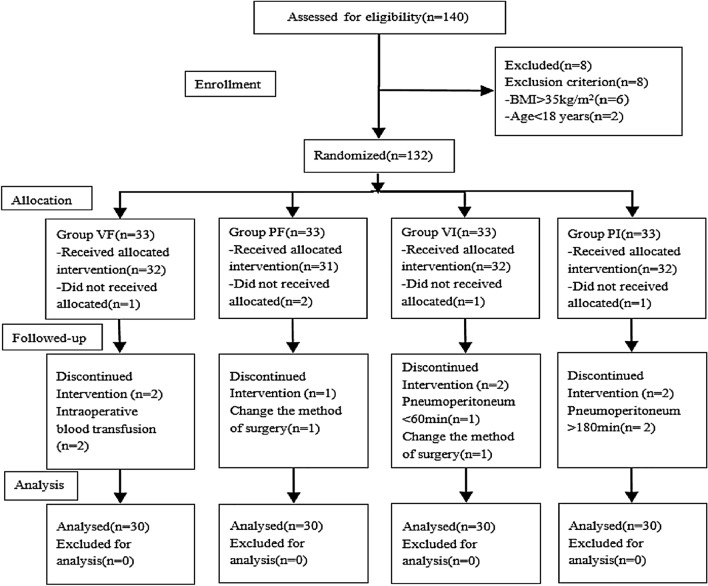

140 patients, who were scheduled to receive laparoscopic surgery in Trendelenburg position, were initially enrolled and follow-up of patients was provided in Fig. 2. Of these, 20 patients were excluded and a total of 120 patients completed the study. There was no significant difference among the groups in terms of characteristics and intraoperative data. (p > 0.05) (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 2.

The study protocol

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Index | VF (n=30) | PF (n=30) | VI (n=30) | PI (n=30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 45.0 ± 14.3 | 43.9 ± 13.8 | 48.8 ± 15.6 | 48.9 ± 13.5 |

| Sex(F/M) | 25/5 | 26/4 | 25/5 | 25/5 |

| Height(cm) | 162.9 ± 6.8 | 163.3 ± 7.4 | 162.2 ± 6.9 | 162.0 ± 6.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.8 ± 3.6 | 24.6 ± 3.1 | 24.7 ± 3.9 | 25.0 ± 3.0 |

| PBW (kg) | 55.1 ± 6.3 | 55.1 ± 6.0 | 54.5 ± 6.4 | 54.3 ± 6.3 |

| ASA(I/II/III) | 0/29/1 | 0/28/2 | 0/27/3 | 0/28/2 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number of patients; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists, BMI: body mass index, F:female, M: male, PBW: estimated weight; VF: VCV plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, PF: PCV-VG plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, VI: VCV plus individual PEEP, PI: PCV-VG plus individual PEEP

Table 2.

Intraoperative Data

| Index | VF (n = 30) | PF (n = 30) | VI (n = 30) | PI(n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Gastrointestinal Surgery | 8(26.7%) | 9(30.0%) | 7(23.3%) | 8(26.7%) |

| Gynecology | 22(73.3%) | 21(70.0%) | 23(76.7%) | 22(73.3%) |

| Vasoactive drugs | 9(30.0%) | 10(33.3%) | 8(26.7%) | 11(36.7%) |

| Volume of fluid (mL) | 1000(1000,1100) | 1000(1000,1500) | 1000(1000,1500) | 1000(1000,1500) |

| Urine output (mL) | 100(50,200) | 100(50,200) | 100(50,150) | 100(50,100) |

| Duration of operation (min) | 82(70,103) | 81(75,107) | 95(76,106) | 95(90,105) |

|

Duration of anesthesia (min) |

112(87,135) | 114(100,141) | 130(105,155) | 130(110,140) |

| Duration of pneumoperitoneum (min) | 68(60,90) | 70(65,93) | 85(65,100) | 85(79,100) |

| Blood loss (mL) | 15(5,23) | 20(10,50) | 20(10,80) | 30(9,50) |

| HR (bpm) | ||||

| T1 | 66.0 ± 9.3 | 66.3 ± 11.2 | 67.1 ± 7.7 | 65.8 ± 6.2 |

| T2 | 75.6 ± 10.9 | 73.6 ± 7.2 | 74.6 ± 4.6 | 75.0 ± 7.0 |

| T3 | 69.2 ± 9.6 | 67.7 ± 9.0 | 67.5 ± 5.1 | 67.6 ± 6.3 |

| MAP (mmHg) | ||||

| T1 | 88.8 ± 12.4 | 82.9 ± 18.1 | 82.1 ± 14.5 | 85.3 ± 11.7 |

| T2 | 96.6 ± 17.7 | 94.9 ± 13.4 | 95.5 ± 13.5 | 94.6 ± 15.1 |

| T3 | 87.8 ± 16.6 | 89.5 ± 14.1 | 87.0 ± 11.5 | 87.4 ± 10.6 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range).VF: VCV plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, PF:PCV-VG plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, VI:VCV plus individual PEEP, PI:PCV-VG plus individual PEEP.T1:in the supine position 15 min after the induction of anesthesia, T2:60 min after CO2 pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg position, T3: 5 min after placement in the supine position at the end of anesthesia

Respiratory mechanics

There was no statistically significant difference among the groups in the values of tidal volume (p > 0.05). Compared with the group VF and PF, the level of PEEP was higher in the group VI and PI at T1, T2 and T3 (p < 0.05). At T2, the Pmean was increased in the group VI and PI than that in the group VF and PF (p < 0.05). Compared with the group VF, PF and VI, the Ppeak was decreased in the PI group at T2 (p < 0.05). The Cdyn was higher in the PI group than that in the group VF and PF throughout the study period (p < 0.05), and it was increased in the PI group compared with VI group at T2 and T3 (p < 0.05). Also, the Cdyn of the group VI and PF was better than that in the VF group at T3 (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Respiratory mechanics, Ventilatory and Oxygenation parameters

| Index | Time Point |

VF (n = 30) |

PF (n = 30) |

VI (n = 30) |

PI (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

VT (mL) |

T1 | 386 ± 44 | 386 ± 42 | 382 ± 45 | 383 ± 43 |

| T2 | 384 ± 44 | 384 ± 42 | 381 ± 45 | 381 ± 44 | |

| T3 | 389 ± 43 | 384 ± 42 | 382 ± 43 | 378 ± 44 | |

|

PEEP (cmH2O) |

T1 | 5 | 5 | 6(4,8) ▲△ | 6(4,8) ▲△ |

| T2 | 5 | 5 | 8(6,10) ▲△ | 8(6,10) ▲△ | |

| T3 | 5 | 5 | 6(4,8)▲△ | 6(4,8) ▲△ | |

|

Ppeak (cmH2O) |

T1 | 15.4 ± 1.9 | 15.5 ± 2.3 | 15.9 ± 1.9 | 15.2 ± 3.2 |

| T2 | 24.1 ± 2.4 | 23.4 ± 2.3 | 24.9 ± 2.5△ | 21.9 ± 2.5▲△* | |

| T3 | 15.6 ± 2.4 | 15.2 ± 2.7 | 17.8 ± 2.4▲△ | 15.1 ± 2.9* | |

|

Pmean (cmH2O) |

T1 | 11.0 ± 3.2 | 10.0 ± 2.2 | 10.1 ± 3.4 | 9.8 ± 2.4 |

| T2 | 13.1 ± 2.2 | 13.9 ± 2.9 | 16.5 ± 2.9▲△ |

16.8 ± 2.2▲△ 20▲△ |

|

| T3 | 10.8 ± 1.6 | 11.6 ± 2.3 | 10.0 ± 2.0△ | 9.4 ± 2.4▲△ | |

|

Cdyn (mL/cmH2O) |

T1 | 49.8 ± 8.7 | 51.2 ± 8.8 | 54.5 ± 9.9 | 59.7 ± 16.3▲△ |

| T2 | 25.5 ± 3.7 | 27.4 ± 4.6 | 29.0 ± 5.0 | 33.7 ± 7.1▲△* | |

| T3 | 34.3 ± 3.8 | 42.1 ± 7.0▲ | 43.6 ± 8.0▲ | 53.2 ± 13.1▲△* | |

|

PaO2/FiO2 (mmHg) |

T1 | 374 ± 16 | 378 ± 31 | 378 ± 18 | 379 ± 23 |

| T2 | 278 ± 28 | 332 ± 39▲ | 298 ± 35▲△ | 338 ± 25▲* | |

| T3 | 286 ± 31 | 326 ± 14▲ | 289 ± 30△ | 341 ± 16▲△* | |

| VD/VT | T1 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.02 |

| T2 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.02▲ | 0.44 ± 0.02▲ | 0.34 ± 0.05▲△* | |

| T3 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.07 | |

| Qs/Qt | T1 | 0.12(0.12,0.13) | 0.12(0.11,0.13) | 0.12(0.12,0.13) | 0.12(0.11,0.13) |

| T2 | 0.16(0.15,0.16) | 0.14(0.13,0.16)▲ | 0.15(0.14,0.16)▲△ | 0.13(0.13,0.14)▲* | |

| T3 | 0.15(0.15,0.16) | 0.14(0.13,0.14)▲ | 0.15(0.15,0.16)△ | 0.13(0.13,0.14)▲△* | |

|

A-aDO2 (mmHg) |

T1 | 226.8 ± 14.3 | 222.4 ± 26.7 | 224.0 ± 14.8 | 223.5 ± 18.6 |

| T2 | 298.9 ± 21.6 | 255.6 ± 32.3▲ | 282.8 ± 28.1▲△ | 250.9 ± 20.0▲* | |

| T3 | 291.5 ± 24.5 | 260.0 ± 13.3▲ | 289.1 ± 22.9△ | 248.1 ± 13.9▲△* |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range). VF: VCV plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, PF: PCV-VG plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, VI: VCV plus individual PEEP, PI: PCV-VG plus individual PEEP.T1: in the supine position 15 min after the induction of anesthesia, T2: 60 min after CO2 pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg position, T3: 5 min after placement in the supine position at the end of anesthesia

Compared with group VF, ▲p < 0.05

Compared with group PF,△p < 0.05

Compared with group VI, *p < 0.05

Ventilation efficiency variables

PaO2/FiO2 was increased in group PF and PI than that in the VF group at T2 and T3 (p < 0.05), and it was better in the PI group than in the VI group at T2 and T3 (p < 0.05), Also, compared with the VF group, PaO2/FiO2 was increased in the VI group at T2 (p < 0.05). At T2 and T3, A-aDO2 of the group PI and PF was reduced compared with the group VF and VI (p < 0.05), and it was lower in the VI group than that in the VF group at T2 (p < 0.05). The Qs/Qt was decreased in the PI group, compared with the group VF and VI at T2 and T3 (p < 0.05), and it was lower in the PF group than that in the VF group (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, VD/VT in the PI group was decreased compared with other three groups at T2 (p < 0.05), and it was increased in the VF group than that in the group PF and VI (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Blood gas analysis

PaO2 was increased in the PI group compared with the group VI and VF at T2 and T3 (p < 0.05). Also, it was increased in the PF group compared with the VF group at T2 and T3 (p < 0.05). At T2, PaO2 in the VI group was increased than in the VF group (p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Blood gas analysis

| Index | Time point |

VF (n = 30) |

PF (n = 30) |

VI (n = 30) |

PI (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 7.39 ± 0.04 | 7.39 ± 0.03 | 7.39 ± 0.02 | 7.39 ± 0.02 | |

| pH | T2 | 7.38 ± 0.04 | 7.38 ± 0.04 | 7.39 ± 0.03 | 7.39 ± 0.03 |

| T3 | 7.38 ± 0.04 | 7.38 ± 0.04 | 7.39 ± 0.02 | 7.39 ± 0.04 | |

|

PaCO2 (mmHg) |

T1 | 35.4 ± 3.0 | 36.5 ± 4.1 | 35.4 ± 4.0 | 35.1 ± 1.9 |

| T2 | 39.5 ± 4.1 | 39.4 ± 4.0 | 39.2 ± 1.9 | 39.1 ± 2.3 | |

| T3 | 40.3 ± 2.9 | 40.0 ± 2.6 | 39.9 ± 2.9 | 39.4 ± 3.3 | |

|

PaO2 (mmHg) |

T1 | 299 ± 13 | 302 ± 24 | 302 ± 14 | 303 ± 18 |

| T2 | 222 ± 22 | 266 ± 31▲ | 239 ± 28▲△ | 271 ± 20▲* | |

| T3 | 229 ± 25 | 260 ± 12▲ | 232 ± 24△ | 273 ± 13▲△* |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range). VF: VCV plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, PF: PCV-VG plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, VI: VCV plus individual PEEP, PI: PCV-VG plus individual PEEP.T1: in the supine position 15 min after the induction of anesthesia, T2: 60 min after CO2 pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg position, T3: 5 min after placement in the supine position at the end of anesthesia

Compared with group VF, ▲p < 0.05

Compared with group PF,△p < 0.05

Compared with group VI, *p < 0.05

Serum concentration of CC16 and IL-6

At T3, the concentration of serum CC16 in the PI group was lower than that in other three groups (p < 0.05), and compared with the group VF and VI, the concentration of serum IL-6 was decreased in the PI group (p < 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Serum CC16 and IL-6 concentrations (ng/ml)

| Index | Time point |

VF (n = 30) | PF (n = 30) | VI (n = 30) | PI (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC16 | T1 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 5.0 ± 1.4 |

| T3 | 60.6 ± 11.5 | 53.4 ± 11.1▲ | 53.0 ± 11.0▲ | 47.1 ± 11.9▲△* | |

| IL-6 | T1 | 13.5(5.3,58.6) | 10.6(4.6,57.5) | 10.9(5.3,58.0) | 10.0(4.5,57.4) |

| T3 | 66.0 ± 17.4 | 52.2 ± 18.3▲ | 62.2 ± 17.1△ | 46.0 ± 23.8▲* |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range). VF: VCV plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, PF: PCV-VG plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, VI: VCV plus individual PEEP, PI: PCV-VG plus individual PEEP.T1: in the supine position 15 min after the induction of anesthesia, T3: 5 min after placement in the supine position at the end of anesthesia

Compared with group VF, ▲p < 0.05

Compared with group PF, △p < 0.05

Compared with group VI, *p < 0.05

Other clinical endpoints

There was no significant difference in WBC count, the incidence of cough, expectoration and fever within 3 days after operation among the four groups (p > 0.05) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Postoperative outcomes

| Index | VF (n = 30) | PF (n = 30) | VI (n = 30) | PI (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (× 109) | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.1 | 5.7 ± 1.4 | 6.0 ± 1.2 |

| neutrophile (× 109) | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 4.8 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 1.6 |

| cough | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 2(7%) | 0(0%) |

| expectoration | 1(3%) | 1(3%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) |

| fever | 1(3%) | 1(3%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range). VF: VCV plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, PF: PCV-VG plus fixed PEEP of 5cmH2O, VI: VCV plus individual PEEP, PI: PCV-VG plus individual PEEP

Discussion

The randomized controlled trial observed that PCV-VG ventilation mode combined with individualized PEEP can improve respiratory mechanics and oxygenation, while decreasing lung injury. These results revealed that the PCV-VG ventilation mode combined with individualized PEEP may be beneficial for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery in Trendelenburg position.

Laparoscopic surgery is performed using mechanical ventilation and CO2 pneumoperitoneum on patients in the Trendelenburg position under general anesthesia. However, CO2 pneumoperitoneum and the Trendelenburg position have been reported to increase incidence of PPCs [1]. In addition, inappropriate mechanical ventilation settings may theoretically induce VILI even in patients with normal lungs during general anesthesia [15]. Therefore, it is very important for anesthesiologists to implement ideal lung-protective ventilation strategies to reduce lung injury in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery in Trendelenburg position.

Usually, lung-protective ventilations, which consist of a lower tidal volume (VT), higher PEEP and regular alveolar recruitment maneuvers (ARM), are accepted by anesthesiologists as effective ways to improve oxygenation and reduce VILI during surgeries [16]. However, relevant studies have concluded that the optimal PEEP and actual effects of PEEP remains controversial [17, 18]. Fixed PEEP may not fit each patient and proper PEEP regulation may produce significant lung-protective effect, whereas improper PEEP levels may lead to lung tissue hyperinflation or pulmonary atelectasis [19, 20]. Therefore, it is important to determine individualized PEEP to suit the individual lung physiology of different patient. A recent study showed that an optimal individualized PEEP level determined by a static pulmonary compliance-directed PEEP titration was superior to conventional ventilation mode and exerted a favourable lung-protective effect during general anesthesia in laparoscopic total hysterectomy [12].

At present, the PEEP titration based on lung compliance has two methods: incremental titration and decremental titration. Previous study shown that both the incremental titration and decremental titration were able to decrease intraoperative shunt, but only the decremental titration improved oxygenation and lowered driving pressure [14]. Our previous study suggested that the decremental PEEP titration can improve respiratory mechanics, oxygenation parameters, and the inflammatory reaction during one-lung ventilation [10]. However, another resaerch suggested that the incremental titration can also improve oxygenation [21], which was similar to our present study.

VCV and PCV, commonly used by clinical practice, have some disadvantages in different patterns. PCV-VG is a relatively new ventilation mode, which initially transmits a preset VT by a decelerating flow at a lower airway pressure and automatically adjusts the airway pressure of the next breath by measuring a patient’s inspiratory pressure and pulmonary compliance [22]. Theoretically, PCV-VG is suitable for maintaining an appropriate VT during laparoscopic surgery with Trendelenburg position, where CO2 pneumoperitoneum and position adjustments may cause sudden changes in intra-abdominal pressure. Recently, some studies about the lung-protective effect of PCV-VG superior to other ventilation modes were established during laparoscopic surgery [22, 23]. Nevertheless, lung-protective effects of PCV-VG has not been deeply studied, and the efficacy of PCV-VG combined with individualized PEEP on patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery in Trendelenburg position is not known.

CO2 pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg position leaded to increased intrathoracic pressure, increased Ppeak and decreased lung compliance [8]. The results of the present study are consistent with our expectation that using an individualized PEEP under PCV-VG mode can improve lung mechanics, pulmonary gas exchange, and arterial oxygenation as well as hemodynamic stability. Firstly, our data showed that PCV-VG combined with individualized PEEP produced a lower Ppeak, which was in line with our recent data during one-lung ventilation [10]. Ppeak level was probably not accurately reflect alveolar pressure [24], and it might be worthless due to the resistance of the tracheal tube and the ventilation mode-related difference in endinspiratory flow [25]. Nevertheless, Pmean closely reflects mean alveolar pressure and correlates with alveolar ventilation and gas oxygenation [26]. In the present study, our data indicated that the Pmean in the PI and VI group was higher than that in the group PF and VF, and the Cdyn in the PI group was increased compared with other three groups, which were consisted with the results of our recent study in one-lung ventilation [10], implying the actions of reasonable individualized PEEP is superior to fixed 5 cmH2O of PEEP. Furthermore, it usually requires increased Pmean by the application of extrinsic PEEP to prevent low VT-induced atelectasis and hypoventilation [27]. However, it needs to be noted that an abnormally higher Pmean may lead to hemodynamic instability. In this study, there was no difference in hemodynamics among the four groups, probably due to the higher Pmean did not substantially affect hemodynamic stability.

PCV-VG can improve oxygenation and reduce the pulmonary shunt due to decelerating flow and higher Pmean. However, the data from a recent study indicated PCV-VG did not produce better oxygenation than VCV, despite the increased Pmean and higher Cdyn observed during robot-assisted laparoscopic gynecologic surgery in the Trendelenburg position [8]. Moreover, it requires intraoperative use of PEEP to prevent unwanted pulmonary pathophysiological effects induced by CO2 pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg position [28]. Hence, we designed this trial to explore the effect of PCV-VG plus individualized PEEP on alveolar ventilation and oxygenation. Our results suggested that PaO2/FiO2 was increased in the PI group compared with other groups, and the lower A-aDO2, Qs/Qt and VD/VT in the PI group were detected in this study, which suggested that PCV-VG combined with individualized PEEP mode resulted in superiority for improving ventilation and oxygenation. It might be associated with the impact of higher Pmean on oxygenation and the prevention of atelectasis under the automatic adjustment of PCV-VG mode. In fact, decelerating flow of PCV-VG mode with high initial flow velocity is different with the constant flow pattern observed in VCV mode, which contributes to ventilation-perfusion matching and reduces pulmonary shunt [29]. Moreover, optimal PEEP results in minimal dead-space and maximal arterial oxygen tension and compliance. According to our study, 8cmH2O might be the optimal PEEP level for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery in Trendelenburg position, which is consist with a previous study [28]. As a matter of fact, excessively higher Pmean could result in Qs/Qt disturbance. Nevertheless, the Qs/Qt was lower in the PI group in our study, indicating that acceptable Pmean made alveoli properly open.

Laparoscopic surgery itself induces increased inflammatory biomarkers after operation despite minimally invasive surgical procedure [12]. Recently, the data of a study from our team showed that the inflammatory mediator neutrophil elastase participated in acute lung injury during one-lung ventilation and the PCV-VG combined with individualized PEEP ventilation strategy exerted a protective effect against lung injury by decreasing neutrophil elastase concentration [10]. CC-16, as an inflammatory mediator, secretes mainly from Clara cells in the airway epithelium of the distal lung. Research has shown that CC-16 may indicate the occurrence of atelectasis and lung hyperinflation in general anesthesia patients undergoing mechanical ventilation [30]. IL-6 is also an early predictor of VILI, reflecting the degree of lung damage and inflammation [31]. In current study, significant differences were obtained in the serum levels of CC16 and IL-6 in the PI group compared with other groups, indicating the ventilation strategy of PCV-VG combined with individualized PEEP could alleviate ventilator-induced inflammatory response and lung injury. However, a recent study showed that the individualized PEEP alone did not make a difference to the inflammatory process compared with conventional ventilation mode in patients undergoing laparoscopic total hysterectomy surgery [12]. It was possible that PCV-VG aside from individualized PEEP was adopted in our study. Unfortunately, we did not found significant differences about the postoperative complications among the groups such as fever, infection, cough and expectoration. Whether the strategy of PCV-VG combined with individualized PEEP could improve postoperative outcomes requires further study using more accurate parameters.

There were some potential limitations in our present study. Firstly, the study population in this research was relatively small and further studies should be conducted to confirm these results at multiple centers. Secondly, our study did not include patients with obesity or respiratory disease, which were important factors for compromising oxygenation and respiratory mechanics.

In conclusion, the ventilation strategy of PCV-VG combined with an individualized PEEP was beneficial to intraoperative respiratory mechanics, oxygenation parameters, and the inflammatory reaction. This ventilation strategy may be a feasible alternative ventilation mode in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery in Trendelenburg position.

Author contributions

Jianli Li designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Saixian Ma conducted the study and analyzed the data. Xiujie Chang, Songxu Ju and Meng Zhang conducted the study. Dongdong Yu analyzed the data. And Junfang Rong edited the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Hebei Province (Grant No. 19277714D).

Data availability

The clinical data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Trial of Hebei General Hospital, China (ethics approval no.2019–48).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Arvizo C, Mehta S, Yunker A. Adverse events related to Trendelenburg position during laparoscopic surgery: recommendations and review of the literature. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:272–78. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Protti A, Cressoni M, Santini A, Langer T, Mietto C, Febres D, et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation: any safe threshold? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1354–62. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1757OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assad O, El Sayed A, Khalil M. Comparison of volume-controlled ventilation and pressure-controlled ventilation volume guaranteed during laparoscopic surgery in Trendelenburg position. J Clin Anesth. 2016;34:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pu J, Liu Z, Yang L, Wang Y, Jiang J. Applications of pressure control ventilation volume guaranteed during one-lung ventilation in thoracic surgery. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:1094–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball L, Dameri M, Pelosi P. Modes of mechanical ventilation for the operating room. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2015;29:285–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeda Y, Fujino Y, Uchiyama A, Matsuura N, Mashimo T, Nishimura M. Effects of peak inspiratory flow on development of ventilator-induced lung injury in rabbits. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:722–28. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200409000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komatsuzaki M, Hamaguchi S. Anesthesia and Anesthesia-related Technology. Kyobu geka. Japanese J Thoracic Surgery. 2018;71:725–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J, Lee S, Rhim C, Seo K, Han M, Kim S, et al. Comparison of volume-controlled, pressure-controlled, and pressure-controlled volume-guaranteed ventilation during robot-assisted laparoscopic gynecologic surgery in the Trendelenburg position. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:2728–34. doi: 10.7150/ijms.49253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J, Lee S, Kim K, Kim Y, Park E. Comparison of volume-controlled ventilation mode and pressure-controlled ventilation with volume-guaranteed mode in the prone position during lumbar spine surgery. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019;19:133. doi: 10.1186/s12871-019-0806-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Cai B, Yu D, Liu M, Wu X, Rong J. Pressure-controlled ventilation-volume guaranteed mode combined with an open-lung approach improves lung mechanics, oxygenation parameters, and the inflammatory response during one-lung ventilation: a randomized controlled trial. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1403053. doi: 10.1155/2020/1403053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu C, Yao J, An L, Bai Y, Li W. Effects of intraoperative individualized PEEP on postoperative atelectasis in obese patients: study protocol for a prospective randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21:618. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04565-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Huang X, Hu S, Meng Z, He H. Individualized lung protective ventilation vs. conventional ventilation during general anesthesia in laparoscopic total hysterectomy. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2020;19:3051–59. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrando C, Soro M, Unzueta C, Suarez-Sipmann F, Canet J, Librero J, et al. Individualised perioperative open-lung approach versus standard protective ventilation in abdominal surgery (iPROVE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:193–203. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spadaro S, Grasso S, Karbing D, Santoro G, Cavallesco G, Maniscalco P, et al. 2020 Physiological effects of two driving pressure-based methods to set positive end-expiratory pressure during one lung ventilation. Journal of clinical monitoring and computing [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Slutsky A, Ranieri V. Ventilator-induced lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2126–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Güldner A, Kiss T, Serpa Neto A, Hemmes S, Canet J, Spieth P, et al. Intraoperative protective mechanical ventilation for prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications: a comprehensive review of the role of tidal volume, positive end-expiratory pressure, and lung recruitment maneuvers. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:692–713. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoftman N, Canales C, Leduc M, Mahajan A. Positive end expiratory pressure during one-lung ventilation: selecting ideal patients and ventilator settings with the aim of improving arterial oxygenation. Ann Card Anaesth. 2011;14:183–87. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.83991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kacmarek R, Villar J. Lung-protective ventilation in the operating room: individualized positive end-expiratory pressure is needed! Anesthesiology. 2018;129:1057–59. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villar J, Blanco J, Kacmarek R. Current incidence and outcome of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22:1–6. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin M, McCormick P, Lin H, Hosseinian L, Fischer G. Low intraoperative tidal volume ventilation with minimal PEEP is associated with increased mortality. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:97–108. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H, Wu X, Li J, Liu Y, Huang Y, Zhang M, et al. Individualized PEEP ventilation between tumor resection and dural suture in craniotomy. Clin Neurol Neurosurgery. 2020;196:e106027. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gad M, Gaballa K, Abdallah A, Abdelkhalek M, Zayed A, Nabil H. Pressure-controlled ventilation with volume guarantee compared to volume-controlled ventilation with equal ratio in obese patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy. Anesth Essays Res. 2019;13:347–53. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_82_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lian M, Zhao X, Wang H, Chen L, Li S. Respiratory dynamics and dead space to tidal volume ratio of volume-controlled versus pressure-controlled ventilation during prolonged gynecological laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3605–13. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5392-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozé H, Lafargue M, Batoz H, Picat M, Perez P, Ouattara A, et al. Pressure-controlled ventilation and intrabronchial pressure during one-lung ventilation. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:377–81. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slinger P, Lesiuk L. Flow resistances of disposable double-lumen, single-lumen, and Univent tubes. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1998;12:142–44. doi: 10.1016/S1053-0770(98)90320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee K, Oh Y, Choi Y, Kim S. Effects of a 1:1 inspiratory to expiratory ratio on respiratory mechanics and oxygenation during one-lung ventilation in patients with low diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide: a crossover study. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27:445–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grichnik K, Shaw A. Update on one-lung ventilation: the use of continuous positive airway pressure ventilation and positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation–clinical application. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:23–30. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32831d7b41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haliloglu M, Bilgili B, Ozdemir M, Umuroglu T, Bakan N. Low tidal volume positive end-expiratory pressure versus high tidal volume zero-positive end-expiratory pressure and postoperative pulmonary functions in robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Med Prin Pract: Intl J Kuwait Uni, Health Sci Centre. 2017;26:573–78. doi: 10.1159/000484693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prella M, Feihl F, Domenighetti G. Effects of short-term pressure-controlled ventilation on gas exchange, airway pressures, and gas distribution in patients with acute lung injury/ARDS: comparison with volume-controlled ventilation. Chest. 2002;122:1382–88. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAuley D, Matthay M. Clara cell protein CC16. A new lung epithelial biomarker for acute lung injury. Chest. 2009;135:1408–10. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez-Bustamante A, Klawitter J, Repine J, Agazio A, Janocha A, Shah C, et al. Early effect of tidal volume on lung injury biomarkers in surgical patients with healthy lungs. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:469–81. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The clinical data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.