Abstract

There is a relative dearth of research on Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD), even if it has been recognized for over 100 years. Thus, the present study aims to review the worldwide prevalence of OCPD in different populations. The search was conducted employing the PubMed database of the US National Library of Medicine and Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde (BVS) to detect available studies showing OCPD prevalence rates. All the prevalence rates were extracted and aggregated through random-effects models. Meta-regression and sensitivity analyses were performed. The final sample was composed of 46 articles, including 89,264 individuals. We found that OCPD reports a high prevalence rate, with 6.5% (95%CI = 4.3–9.1%), and reaching even higher among psychiatric and clinical patient population. OCPD has presented stable prevalence rates worldwide throughout the past 28 years. There was no gender-related effect, but OCPD prevalence rates may decrease with age increase. There is a need to investigate personality disorders epidemiology based on the recently updated classification systems (i.e., DSM-5 and ICD-11). The present meta-analysis may suggest that the current diagnostic tools may detect OCPD in a cross-sectional assessment but not throughout the life of the person.

Keywords: OCPD, Prevalence, Personality disorders, Compulsive personality disorder

Highlights

-

•

OCPD rates do not vary significantly around the globe, with a prevalence of 6.5%.

-

•

Higher rates were found in psychiatric and clinical patients’ population.

-

•

OCPD prevalence has been stable throughout the past 28 years.

-

•

There was no genre-related effect but it may decrease with age increase.

-

•

The current diagnostic instruments may detect OCPD but may not concisely and adequately evaluate its clinical impact.

OCPD; Prevalence; Personality Disorders; Compulsive Personality Disorder.

1. Introduction

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-fifth edition (“DSM-5”), personality traits may constitute personality disorders (PD) in case of a persistent and inflexible pattern of internal experience and behavior that markedly deviates from the expectations of the individual culture that is present in at least two of the following domains: cognition, affectivity, interpersonal functioning, and impulse control. A PD causes clinically significant suffering and impairments to several areas of an individual's life (e.g., social, professional). It is a persistent disorder that shows a stable pattern, and its appearance usually occurs in adolescence or early adulthood (APA, 2013). PD prevalence data in the general population were widely unknown until the 90s (Lenzenweger, 2008). The third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980 included diagnostic criteria and a multiaxial classification system. Also, new diagnostic instruments and structured and semi-structured clinical interviews were proposed. One of the most common PD in the general population is the Obsessive-Compulsive PD (OCPD) (Mancebo et al., 2005; Soeteman et al., 2008): it is associated with a reduction in quality of life, with at least a moderate effect on the psychosocial functioning (Mancebo et al., 2005) and a considerable economic burden (Soeteman et al., 2008). In addition, PDs are associated with high mortality rates and an increased number of comorbidities (Skodol, 2016, Santana et al., 2018), as well as with frequent interpersonal exchange difficulties and lower education (Moran et al., 2016). It has also been described an association between PD and higher alcohol and psychoactive substances consumption rate with elevated risks of self-aggression, suicidal attempts, and committed suicides (Hiroeh et al., 2001). PD may also lead to a significant impairment in the working capability with indirect costs due to the absence at work (Barrett and Byford, 2012). Coid et al. (2006) identified that people with PD were more likely to report unemployment or economic inactivity when compared to people without PD.

Despite the individual and social burden associated with PD, research in epidemiology is currently poor. Also, prevalence rates in different studies are heterogeneous, varying from 4% to 15% in the European and American cross-sectional studies (Coid et al., 2006). These differences can be attributed to different study populations, sampling methods, and diagnostic evaluation methods (Volkert et al., 2018). Ames and Molinari (1994) found 0.5% OCPD prevalence among elderly living in the community. Coid et al. (2006) found an 2.1% OCPD prevalence in a representative sample of individuals living in Great Britain. Jackson and Burgess (2000) found a slightly higher prevalence (3.1%) in a random sample of households in Australia. In other hand, a much higher prevalence of OCPD was found by Chamberlain et al. (2017) among internet users (71.5%). In a stratified sample in Turkey, there was 15.6% of individuals with OCPD (Dereboy et al., 2014).

OCPD is clinically characterized by an individual concern for order, perfectionism, and mental and interpersonal control at the expense of flexibility, openness, and efficiency (Chamberlain et al., 2017). Patients with OCPD strive to achieve perfectionism that interferes in their task completion: the primary goal of an activity or task may go unnoticed because of the great concern with details, rules, lists, order, or schedules (Costa et al., 2005). These individuals are usually reluctant to delegate tasks to team-workers and often focus on poor relevant details (APA, 2013). They may also be excessively dedicated to their working productivity up to the point of excluding their friendships and hobbies (Torres et al., 2006). Patients with OCPD usually show rigidity and stubbornness, possibly acting with an excess of awareness, scrupulousness, and inflexibility with regard to ethics, values, and moral issues (Mancebo et al., 2005). It is also described as having difficulty discarding objects even when patients do not report any sentimental bond with the object itself. They also usually save money, bearing the perspective of possible future catastrophes (APA, 2013). In the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), it has been included the Anankastic PD (OCPD), characterized by the presence of feelings of doubt, perfectionism, over consciousness, excessive patterns of verification and concern with details, stubbornness, caution, and rigidity (World Health Organization, 1993).

This meta-analysis study aimed to determine the OCPD prevalence in different populations (general, clinical psychiatric, prison, and student), global regions (Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania), and based on different criteria (DSM-III, DSM-IV, DSM-5, and ICD-10).

2. Methodology

2.1. Review guidelines and registration

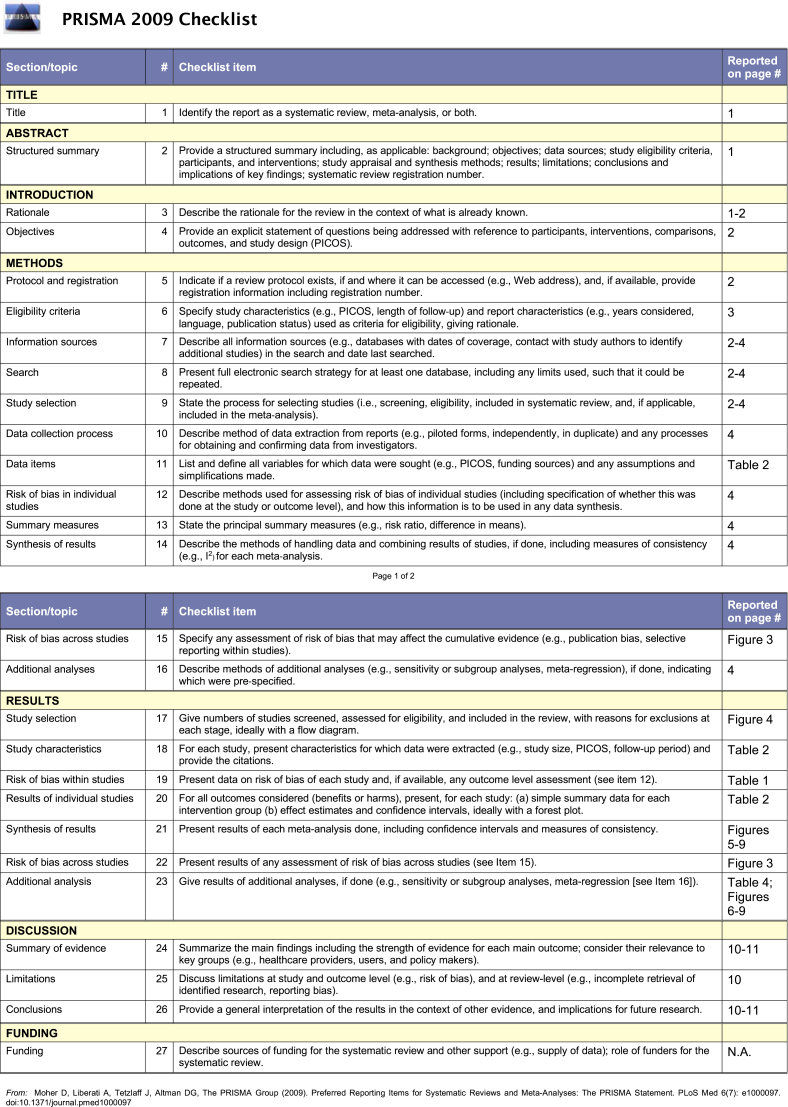

This study followed the PRISMA statement for the transparent report of systematic reviews and meta-analysis (Moher et al., 2009) and MOOSE guidelines for Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (Stroup et al., 2000). Figures 1 and 2 respectively present PRISMA and MOOSE checklists reporting the page of the manuscript in which we considered the item addressed. This study was registered at the Center for Open Science/Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/wnu8t/?view_only=d6433424400b4cf6858d6cc2b98b0ccf).

Figure 1.

PRISMA checklist.

Figure 2.

MOOSE checklist.

2.2. Information sources

We employed the PubMed of the US National Library of Medicine and Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde (BVS) databases. We identified all the relevant articles published in English, Portuguese, and Spanish. The last search was performed on November 17th, 2020.

The utilized search key words with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were: “((("Prevalence"[Mesh]) OR "Epidemiology"[Mesh]) AND "Personality Disorders"[Mesh]) OR "Compulsive Personality Disorder"[Mesh]”, on PubMed and Descritores em Ciências da Saúde (DeCS): “(epidemiologia) OR (prevalência) AND (transtorno da personalidade) OR (transtorno da personalidade compulsiva)” on BVS. The selected articles were processed in two steps.

Step 1. All abstracts were reviewed by the first author and selected on the basis of aiming to describe OCPD prevalence.

Step 2. All abstracts were independently evaluated by two of the authors (first and second) and selected on the base of a consensual agreement on criteria used in Step 1. In case of disagreement, the abstract was evaluated by a third author (last author).

Step 3. The inclusion of the articles was based on a consensual agreement between the first and last authors: 1) original researches about OCPD prevalence were included; 2) studies based on OCPD diagnoses according to ICD (International Classification of Diseases) or DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders); 3) studies based on samples from general population or students; 4) studies including individuals ≥16 years old; 5) studies in English, Portuguese or Spanish.

The main objective of this study was to analyze OCPD prevalence rates in the general population and students worldwide.

Review of Specialized books. Eight books were considered and reviewed: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (“DSM-5”) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); Textbook of Psychiatry (Roberts, 2019); Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry (Sadock et al., 2015); Psychodynamic Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, Fifth Edition (Gabbard, 2014); Clínica Psiquiátrica de Bolso (Forlenza and Miguel, 2014); Psiquiatria: Estudos Fundamentais (Meleiro, 2018); Manual de Psiquiatria Clínica (Paraventi and Chaves, 2016); Transtorno da Personalidade (Neto and Cols, 2011).

Contact with experts. Sixteen specialists in the field of PDs from North America, South America, and Europe were contacted via e-mail to include potentially relevant articles that were not found by our search strategy.

Revision of reference list. The reference list of all selected articles in Step 3 was reviewed.

2.3. Data extraction

Data were extracted from the selected (full-text) articles by the first author and reviewed by the last author. All divergencies between the first and last authors were discussed with the second author.

2.4. Quality assessment

The purpose of this evaluation was to analyze the methodological quality of the studies included. The Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Prevalence Studies (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017) was applied to all studies included in the current systematic review, which evaluates sample frame, process and size, setting description, data analysis coverage, valid and reliable evaluation methods, appropriate statistical analysis, and an adequate response rate (Table 1). As a result, all the 46 studies scored ≥6 on the scale (maximum = 9 points) and were included in the present meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Results of the quality assessment.

| Authors | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torgersen S et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Jackson JH et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Lenzenweger MF et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Coid J et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Samuels J et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Mike A et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Chamberlain SR et al. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Jalenques I et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Gawda B el at | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Ansari Z et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Nicoletti et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Quirk SE et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Kayhan F el at | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Black DW et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Yılmaz A et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Dereboy C et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Sahingöz M et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Uguz F et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Kempke S et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Samuel DB et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Moore EA et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Coolidge FL et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Sassoon SA et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Cheng H et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Crawford TN et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Moldin SO et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Maier W et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Black DW et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Aycicegi-Dinn A et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| ECHEBURÚA E et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Yang M et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Torres AR et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Larsson JO et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Anderluh MB et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Sinha BK et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Maggini C et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Moran P et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Bodlund O et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Ames A et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Samuels JF et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Moran P et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Grant BF et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Wongpakaran N et al. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| HYUN HA J et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kulkarni RR et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Ekselius L. et al. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 1 = Yes | 0 = No/Unclear | |||||||||

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for studies reporting prevalence data | ||||||||||

| 1. Was the sample frame appropriate to address the target population? | ||||||||||

| 2. Were study participants sampled in an appropriate way? | ||||||||||

| 3. Was the sample size adequate? | ||||||||||

| 4. Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | ||||||||||

| 5. Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? | ||||||||||

| 6. Were valid methods used for the identification of the condition? | ||||||||||

| 7. Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants? | ||||||||||

| 8. Was there appropriate statistical analysis? | ||||||||||

| 9. Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately? | ||||||||||

2.5. Data analysis

We used R software version 3.5.0 to run the analysis (Syntax reported in Supplementary File 1). The first step of our previously defined data analysis strategy was to determine the prevalence of OCPD in the general population and among students worldwide. As recommended by Barendregt et al. (2013), we used Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation because the prevalences found were close to 0 or 1 (i.e., as in the present study) to normalize its distribution and stabilize the variances. A heterogeneity test (Q test) was used to determine if the differences between prevalence estimations in the studies were bigger than those expected by chance. Heterogeneity between the studies was measured using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of variability among effect estimates beyond that expected by chance. If the value is below 25%, it implies there being low heterogeneity. A value of 50% implies moderate, and a value of 75% high levels of heterogeneity (Chiang et al., 2022). We used the DerSimonian-Laird estimator for tau2. Significant heterogeneity was detected for the combined estimation. Hereupon, we conducted leave-one-out meta-analysis. In addition, we conducted subgroup analysis by type of population, diagnostic criterion, and global region. The Egger's regression method (Figure 3) was used to assess publication bias (Lim et al., 2019). The presence of statistically significant publication bias was defined as p-values of 0.05 or less. The presence of publication bias was then investigated further using a fail-safe N test (Figure 3) to estimate the number of additional studies needed to make the eventual effect size insignificant (Lim et al., 2019). Then, we plotted an adjusted meta-analysis and forest plot for all the studies, using the ‘trim-and-fill’ technique (Idris, 2012). The trim-and-fill method works by trimming the studies that cause asymmetry in a funnel plot so that the overall effect estimate produced by the remaining studies is minimally influenced by publication bias, and then filling in imputed missing studies in the funnel plot using the bias-corrected overall estimate (Shi and Lin, 2019).

Figure 3.

Publication Bias: Results of funnel plot and tests for all studies included in the meta-analysis for OCPD prevalence. Egger's regression test of funnel plot asymmetry: t = 2.2603, df = 75, p-value = 0.02671. Fail-safe N Calculation Using the Orwin Approach: 1 (Average Effect Size: 0.139; Target Effect Size: 0.0695).

Once significant heterogeneity was found among all the studies, the second step was to conduct univariate analysis to test the individual association of each variable (methodological variables + geographic location of studies) to estimate OCPD combined prevalence by using a meta-regression analysis. In the third step, a random-effects regression model was used to evaluate the variability in estimating OCPD prevalence, following previous studies (Foo et al., 2018). By assuming that the selected studies are random samples from a larger population, the random-effects model attempted to generalize findings beyond the included studies. For these analyses, a significance level of 5% was established.

3. Results

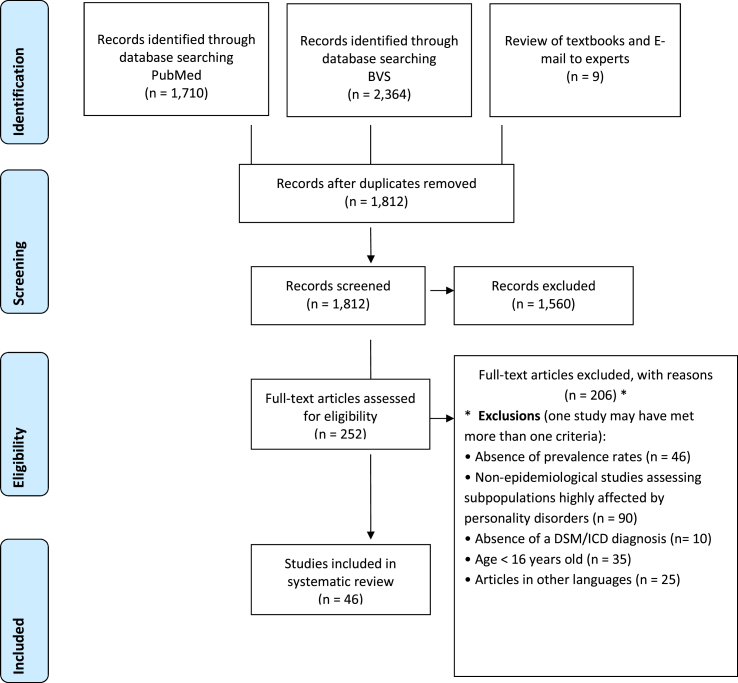

Figure 4 (PRISMA) shows the study selection flow. In order to select the articles of this review, the first and the last authors read the titles and abstracts of all studies searched (n = 4,083). Duplicate studies were excluded, and 1,812 studies were evaluated by titles and abstracts. After that, 252 articles were selected for full-text reading. During this step, 206 articles were excluded: 46 did not report prevalence rates for OCPD; 90 of them reported data of samples at risk for mental disorders or composed by prison population or mentally ill in psychiatric treatment; 10 of them reported any ICD/DSM 5-based diagnosis; 35 of them including individuals younger than 16 years old; and 25 of them were written in languages others than English, Portuguese or Spanish. Table 2 presents the main results of the included studies.

Figure 4.

Study's selection flow chart.

Table 2.

Main results of the included studies.

| Author, year | Study population | Specific population assessed | Setting | Diagnostic criteria, Scale |

Prevalence, N of the OCPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torgersen et al. (2001) | N: 2053 Female/Male (F/M): 0.556 Continent: Europe Mean age: 18-65 |

N: 2053 F/M: 0.556 |

Community | DSM III-R/SCID-II | 2.00% 39 |

| Jackson and Burgess (2000) | N: 10641 F/M: 0.557 Continent: Oceania Mean age: ≥ 18 |

N: 10641 F/M: 0.557 |

Community | CID-10/IPDE | 3.09% 329 |

| Lenzenweger et al. (2007) | N: 5692 F/M: - Continent: North America Mean age: ≥ 18 |

N: 214 F/M: - |

Community | DSM-IV/IPDE | 2.40% 5 |

| Coid et al. (2006) | N: 626 F/M: 0.567 Continent: Europe Mean age: 16 - 74 |

N: 626 F/M: 0.567 |

Community | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 1.90% 13 |

| Samuels et al. (2002) | N: 742 F/M: 0.63 Continent: North America Mean age: 34 - 94 |

N: 742 F/M: 0.63 |

Community | DSM-IV and CID 10/IPDE | DSM-IV: UP = 1,2 (0.4), WP = 0,9 (0,5)/CID-10: UP = 1,1 (0.4), WP = 0,8 (0,4) DSM-IV N = 9/CID-10 N = 8 |

| Mike et al. (2017) | N: 1630 F/M: 0.55 Continent: North America Mean age: 59,53 ± 2,7 |

N: 1630 F/M: 0.55 |

Community | DSM-5/SIDP | 2.90% 47 |

| Chamberlain et al. (2017) | N: 1323 F/M: 0.616 Continent: North America/Africa Mean age: 28.5(13.0) |

N: 1323 F/M: 0.616 |

Community | DSM-5/OPQ | 71.50% 946 |

| Jalenques et al. (2017) | N: 178 F/M: 0.786 Continent: Europe |

N - Healthy Comparison Subjects (HCS): 118 Mean age: 46 ± 13.9 F/M: 0.788 |

Community | DSM-IV/PDQ-4+ | 6% 7 |

| N - Lupus patients: 60 Mean age: 47,5 ± 14 F/M: 0.783 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/PDQ-4+ | 13% 8 |

||

| Gawda and Czubak (2017) | N: 1460 F/M: 0.52 Continent: Europe Mean age: 18 - 65 |

N: 1460 F/M: 0.52 |

Community | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 9.66% 141 |

| Ansari and Fadardi (2016) | N: 110 F/M: - Continent: Asia Mean age: 29.55 |

N: 110 F/M: - |

Students | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 16.36% 18 |

| Nicoletti et al. (2016) | N: 65 F/M: 0.446 Continent: Europe |

N - HCS: 20 Mean age: 65,5 ± 6,0 F/M: 0.5 |

Community | DSM-IV/SCID-II and SCID-II-PQ | 10% 2 |

| N - Patients with Multiple Systems Atrophy: 15 Mean age: 62,9 ± 7,6 F/M: 0.466 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/SCID-II and SCID-II-PQ | 13.3% 2 |

||

| N - Patients with Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: 14 Mean age: 69,8 ± 4,4 F/M: 0.428 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/SCID-II and SCID-II-PQ | 35.7% 5 |

||

| Quirk et al. (2017) | N: 768 F/M: 1 Continent: Oceania Mean age: > 25 |

N - Essential Tremor Patients: 16 Mean age: 70,4 ± 6,4 F/M: 0.375 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/SCID-II and SCID-II-PQ | 12.5% 2 |

| Kayhan and Ilik (2016) | N: 205 F/M: 0.502 Continent: Europe |

N: 768 F/M: 1 |

Community | DSM-IV/SCID-II and SCID-II-PQ | 10.30% 77 |

| N - HCS: 100 Mean age: 31.18 ± 8.98 F/M: 0.5 |

Community | DSM III-R/SCID-II | 8% 8 |

||

| Black et al. (2015) | N: 579 F/M: - Continent: North America |

N - Chronic migraine patients: 105 Mean age: 35.63 ± 11.61 F/M: 0.505 |

Ambulatory | DSM III-R/SCID-II | 50.50% 53 |

| N - HCS: 91 Mean age: 49 ± 16 F/M: 0.63 |

Community | DSM-IV/SIDP | 3% 3 |

||

| N - Patients diagnosed with pathological gambling: 93 Mean age: 49,9 ± 14 F/M: 0.55 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/SIDP | 10% 9 |

||

| Yılmaz et al. (2014) | N: 187 F/M: 0.732 Continent: Europe |

N - 1st degree relatives of patients diagnosed with pathological gambling: 395 Mean age: ≥ 18 F/M: 0.63 |

Community? | DSM-IV/- | - - |

| N - HCS: 90 Mean age: 44,1 ± 12,1 F/M: 0.7 |

Community | DSM-III-R SCID-II |

6.60% 6 |

||

| Dereboy et al. (2014) | N: 774 F/M: 0.59 Continent: Europe Mean age: 18-75 |

N - Asthmatic patients: 97 Mean age: 42.7 ± 11.7 F/M: 0.763 |

Ambulatory | DSM-III-R SCID-II |

11.34% 11 |

| Sahingöz et al. (2013) | N: 146 F/M: 1 Continent: Europe |

N: 774 F/M: 0.59 |

Community | DSM-IV/CID-10 DIP-Q/TCI |

DSM-IV = 14,1% CID-10 = 18,1% DSM-IV = 107 CID-10 = 137 |

| N - HCS: 73 Mean age: 24.59 ± 4.71 F/M: 1 |

Community | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 1.40% 1 |

||

| Uguz et al. (2013) | N: 105 F/M: 0.914 Continent: Europe |

N - Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Patient: 73 Mean age: 23.82 ± 4.99 F/M: 1 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 8.20% 6 |

| N - HCS: 60 Mean age: 38.68 ± 7.54 F/M: 0.960 |

Community | DSM-III/SCID-II | 1.70% 1 |

||

| Kempke et al. (2013) | N: 276 F/M: 1 Continent: Europe |

N - Lupus patients: 45 Mean age: 39.24 ± 9.91 F/M: 0.933 |

Ambulatory | DSM-III/SCID-II | 20.00% 9 |

| Samuel and Widiger (2011) | N: 536 F/M: 0.627 Continent: North America Mean age: 18.8 |

N - HCS: 92 Mean age: 42.4 ± 8.0 F/M: 1 |

Community | DSM-IV/ADP-IV | 7.60% 7 |

| Moore et al. (2012) | N: 1121 F/M: 0.444 Continent: Oceania |

N - Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: 92 Mean age: 42.5 ± 8.2 F/M: 1 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/ADP-IV | 8.70% 8 |

| N - General psychiatric patients: 92 Mean age: 42.6 ± 8.2 F/M: 1 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/ADP-IV | 25% 23 |

||

| Coolidge et al. (2011) | N: 1569 F/M: 0.693 Continent: North America |

N: 536 F/M: 0.627 |

Students | DSM-IV/PDQ-4+ and SCID-II PQ | 50.40% 270 |

| N - HCS: 572 Mean age: 41.8 F/M: 0.554 |

Community | CID-10/IPDEQ | 20.80% 120 |

||

| N - Schizophrenic/schizoaffective patients: 549 Mean age: 39.5 F/M: 0.329 |

Ambulatory | CID-10/IPDEQ | 35.60% 195 |

||

| Sassoon et al. (2011) | N: 59 F/M: 1 Continent: North America |

N - Women not incarcerated: 523 Mean age: 32.6, SD = 19.5 F/M: 1 |

Community | DSM-IV/CCI | 43% 225 |

| N - Incarcerated men: 523 Mean age: 33.6, SD = 9.6 F/M: 0 |

Prison | DSM-IV/CCI | 21% 110 |

||

| Cheng et al. (2010) | N: 7675 F/M: 0.57 Continent: Asia Mean age: ≥ 18 |

N - Incarcerated women: 523 Mean age: 35.0, SD = 8.7 F/M: 1 |

Prison | DSM-IV/CCI | 25% 131 |

| Crawford et al. (2005) | N: 1360 F/M: - Continent: North America Mean age: - |

N - HCS: 26 Mean age: 28.9 ± 7.2 F/M: 1 |

Community | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 0% 0 |

| Moldin et al. (1994) | N: 302 F/M: 0.473 Continent: North America Mean age: 18 - 77 |

N - Women with severe pre-mental disorder: 33 Mean age: 30.6 ± 6.9 F/M: 1 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 18% 6 |

| Maier et al. (1992) | N: 452 F/M: 0.515 Continent: Europe Mean age: 38.1 |

N: 357 F/M: 0.57 |

Students | CID-10/PDQ-4+ and IPDE | 21.84% 78 |

| Black et al. (1993) | N: 65 F/M: 0.60 Continent: North America |

N – AGE 33: 644 F/M: 0.53 Mean age: 33,1 (27,7–40,1) |

Community | DSM-IV/CIC-SR and SCID-II | CIC-SR = 1,4% e SCID II = 4,7% CIC-SR = 9/SCID II = 30 |

| N: 302 F/M: 0.473 |

Community | DSM-III/IPDE | 1.65% 5 |

||

| Aycicegi-Dinn et al. (2009) | N: 117 F/M: 0.683 Continent: North America Mean age: 18.51 (SD = 0.9) |

N: 452 F/M: 0.515 |

Community | DSM-III/SCID-II | 2.20% 10 |

| Echeburúa et al. (2007) | N: 381 F/M: 0.417 Continent: Europe |

N - HCS: 33 Mean age: 38,1 (DP = 10,0) F/M: 0.601 |

Community | DSM-III/SCID-II | 6.10% 2 |

| N - OCD patients: 32 Mean age: 38,3 (DP = 10,0) F/M: 0.594 |

Ambulatory | DSM-III/SCID-II | 28.10% 9 |

||

| N: 117 F/M: 0.683 |

Students | DSM-IV/PDQ-4+ | 17.94% 21 |

||

| N - HCS: 103 Mean age: 40.73 (24–64) F/M: 0.466 |

Community | DSM-IV/IPDE and MCMI-II | 1.9% 2 |

||

| Yang et al. (2007) | N: 1014 F/M: 0.401 Continent: Europe |

N - Alcohol-dependent patients: 158 Mean age: 43.42 (19–65) F/M: 0.348 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/IPDE and MCMI-II | 12% 19 |

| N - Psychiatric patients without alcohol dependence: 120 Mean age: 40.58 (18–65) F/M: 0.467 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/IPDE and MCMI-II | 9.20% 11 |

||

| Torres et al. (2006) | N: 8399 F/M: - Continent: Europe |

N - HCS: 544 Mean age: 42.4(11,9) F/M: 0.562 |

Community | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 1.80% 10 |

| N - Incarcerated: 470 Mean age: 29,5(9,2) F/M: 0.215 |

Prison | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 9.40% 44 |

||

| N - HCS: 6938 Mean age: 16 - 74 F/M: - |

Community | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 8.10% 562 |

||

| Larsson and Hellzén (2004) | N: 29 F/M: 1 Continent: Europe |

N - OCD patients: 108 Mean age: 16 - 74 F/M: - |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 28.60% 31 |

| N - Patients with other neuroses: 1353 Mean age: 16 - 74 F/M: - |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/SCID-II | 20.30% 275 |

||

| Anderluh et al. (2003) | N: 100 F/M: 1 Continent: Europe |

N - HCS: 10 Mean age: 24.6 F/M: 1 |

Community | DSM-IV/DIP-Q | 10% 1 |

| N - Women with Eating Disorders: 19 Mean age: 26.1 F/M: 1 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/DIP-Q | 63.15% 12 |

||

| N - HCS: 28 Mean age: 25.1 F/M: 1 |

Community | CID-10/MOCI | 4% 1 |

||

| Sinha and Watson (2001) | N: 293 F/M: 0.662 Continent: North America Mean age: 21 (SD = 5.5) |

N - Subjects With Anorexia Nervosa: 44 Mean age: 27.9 F/M: 1 |

Ambulatory | CID-10/MOCI | 61% 27 |

| N - Subjects With Bulimia Nervosa: 28 Mean age: 26.7 F/M: 1 |

Ambulatory | CID-10/MOCI | 46% 13 |

||

| Maggini et al. (2000) | N: 2889 F/M: 0.489 Continent: Europe Mean age: 17 ± 0.4 |

N: 293 F/M: 0.662 |

Students | DSM-III-R/CATI and MCMI-II and MMPI-PD | Women: MCMI-II:0,51%/MMPI-PD:0,51%/CATI:0,51%/Men: MCMI-II:0%/MMPI-PD:2,02%/CATI:6,06% Women: MCMI-II:1/MMPI-PD:0/CATI:1/Men: MCMI-II:0/MMPI-PD:2/CATI:6 |

| N: 2889 F/M: 0.489 |

Students | DSM-III/SCID-II | 30.50% 880 |

||

| Moran et al. (2000) | N: 303 F/M: 0.660 Continent: Europe Mean age: 41.8 (range 18 ± 74) |

N: 303 F/M: 0.660 |

Ambulatory | CID-10 and DSM-IV/SAP and IPDE | CID-10 = 7,9%/DSM IV = 6,3% CID-10 = 24/DSM-IV = 19 |

| Bodlund et al. (1998) | N: 587 F/M: 0.453 Continent: Europe |

N - HCS: 139 Mean age: 28.0 (SD = 8.1) F/M: 0.690 |

Community | DSM-IV/DIP-Q | 9% 13 |

| N - General psychiatric patients: 137 Mean age: 37.3 (SD = 12.0) F/M: 0.580 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/DIP-Q | 38% 52 |

||

| N - Forensic psychiatric sample: 217 Mean age: 35.5 (SD = 10.3) F/M: 0.070 |

Forensic Psychiatric Unit | DSM-IV/DIP-Q | 41% 90 |

||

| N - Sample of candidates for psychotherapy: 94 Mean age: 34.2 (SD = 8.1) F/M: 0.810 |

Ambulatory | DSM-IV/DIP-Q | 62% 58 |

||

| Ames and Molinari (1994) | N: 200 F/M: 0.500 Continent: Europe Mean age: 72.1 |

N: 200 F/M: 0.500 |

Community | DSM-III/SIDP-R | 0.50% 1 |

| Samuels et al. (1994) | N: 762 F/M: 0.652 Continent: North America Mean age: 18 - 64 |

N: 762 F/M: 0.652 |

Community | DSM-III/SPE | 1.70% 8 |

| Moran et al. (2006) | N: 2032 F/M: 0.510 Continent: Oceania Mean age: 24.1 |

N: 1943 F/M: 0.510 |

Community | CID-10/SAP | 5.80% 113 |

| Grant et al. (2004) | N: 43093 F/M: - Continent: North America Mean age: ≥ 18 |

N: 43093 F/M: - |

Community | DSM-IV/AUDADIS-IV | 7.90% 3261 |

| Wongpakaran (2005) | N: 99 F/M: 0.495 Continent: Asia Mean age: 22.56 (range 21–25; SD = 1.53) |

N: 99 F/M: 0.495 |

Students | CID-10/IPDE | 2% 2 |

| Ha et al. (2007) | N: 585 F/M: 0 Continent: Asia Mean age: 19,06 ± 0,26 |

N: 585 F/M: 0 |

Community | DSM-IV/PDQ-4+ | 39.80% 233 |

| Kulkarni et al. (2013) | N: 200 F/M: 0.480 Continent: Asia |

N - HCS: 100 Mean age: 27.7 ± 8.58 F/M: 0.480 |

Community | CID-10/IPDE | 4% 4 |

| Ekselius et al. (2001) | N: 557 F/M: 0.549 Continent: Europe Mean age: females 41.9 (SD 14.3)/males 43.2 (SD 13.8) |

N - Patients after first Suicide Attempt: 100 Mean age: 27.31 ± 8.68 F/M: 0.480 |

Hospital | CID-10/IPDE | 11% 11 |

| N: 557 F/M: 0.549 |

Community | CID-10 and DSM-IV/DIP-Q | DSM-IV = 7,7%/ICD-10 = 7,2% DSM-IV = 43/ICD-10 = 40 |

Note. (∗) PD scale abbreviations are shown in Table 4. Additionally, the font size was reduced to fit the page.

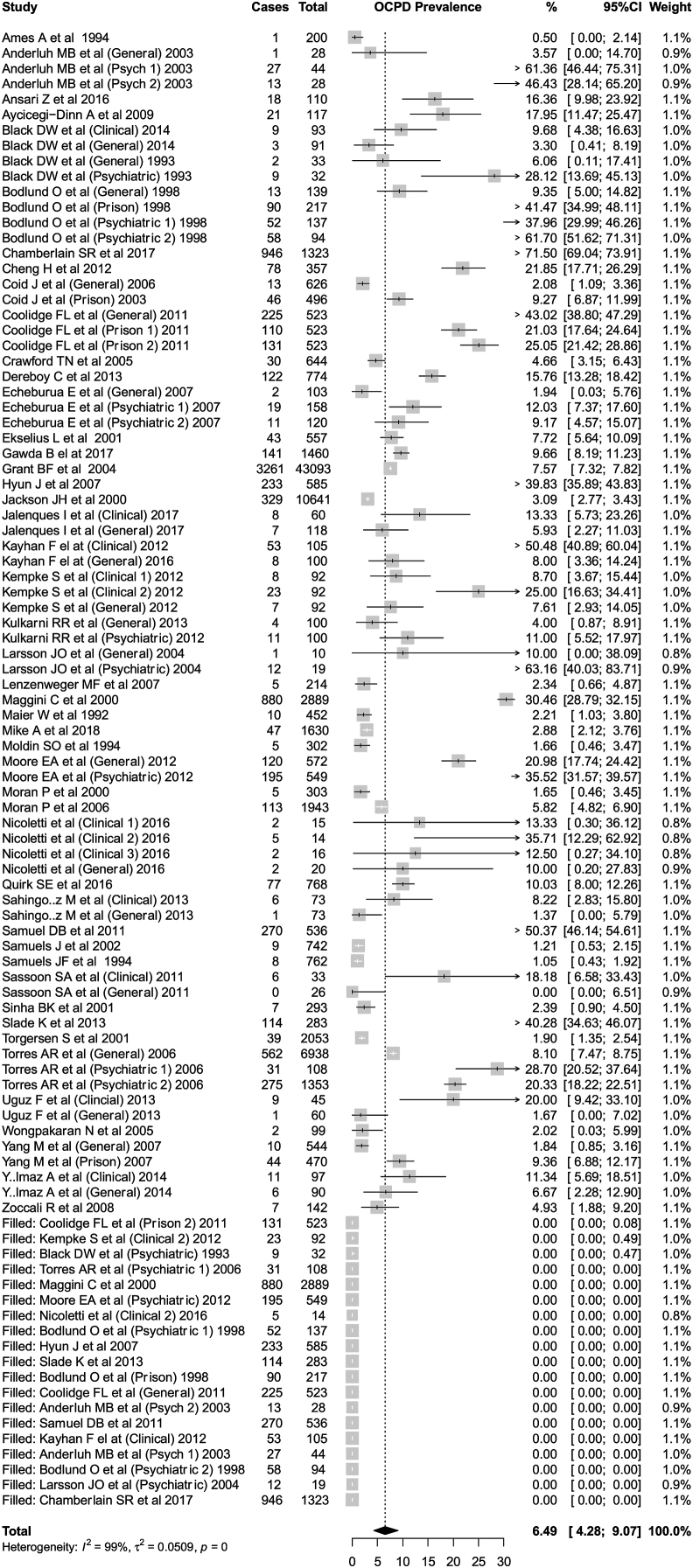

Eventually, 46 articles were included in this review (Figure 4). The meta-analytic sample included 89,264 individuals, with age ≥16 years old. The total sample is composed mainly of individuals from the general population (n = 78,429). There were also seven studies with students (n = 4,401), 13 studies with psychiatric patients (n = 2,835), seven with prisoners (n = 2,654) and 12 with clinical patients (n = 945). Figure 5 shows the adjusted forest plot in which we found an OCPD prevalence of 6.5% (95%CI = 4.3–9.1%). Non-adjusted meta-analysis models are presented in Figures 6, 7, and 8 (subgroup analysis by population type, global region, and diagnostic criteria).

Figure 5.

Adjusted Forest Plot. P.S.: Different subpopulation numbers (e.g., Psychiatric 1 and 2; Prison 1 and 2) refer to different type of subpopulations assessed in the same study (i.e., case-control design).

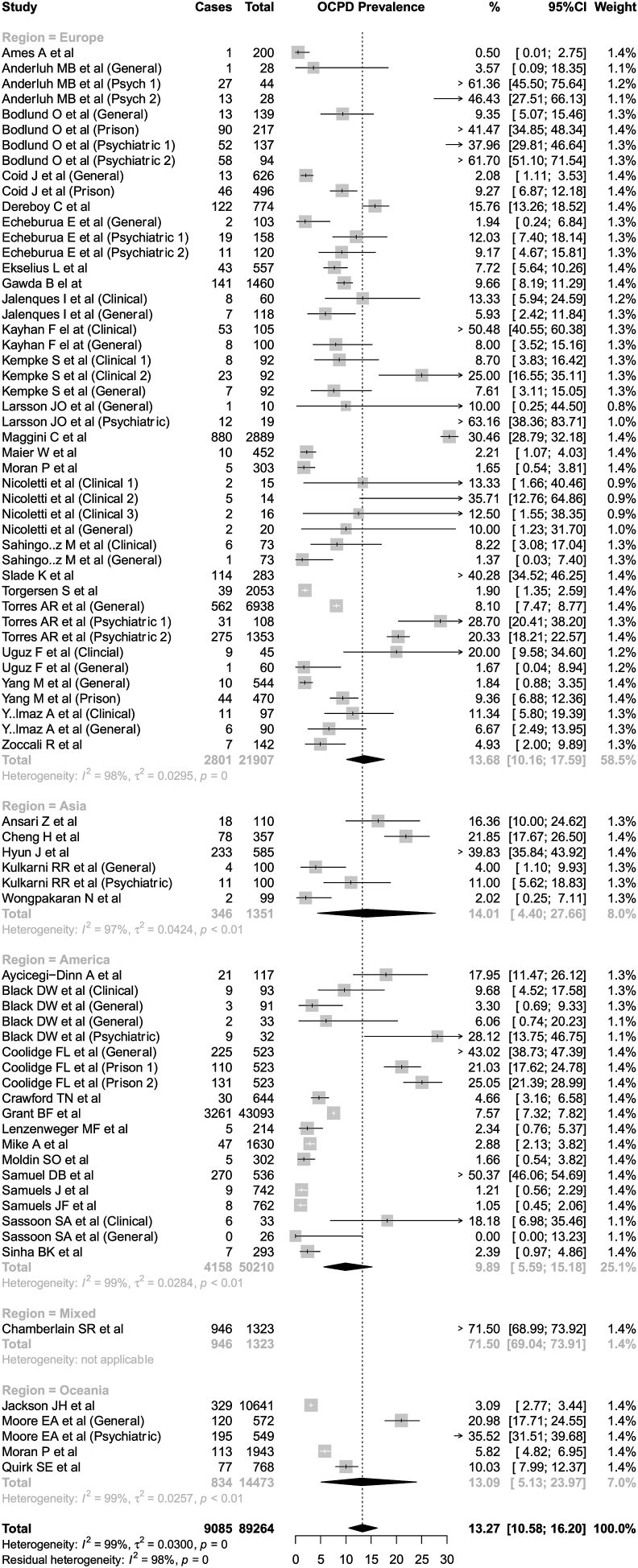

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis - population

Figure 7.

Subgroup analysis - region

Figure 8.

Subgroup analysis - criterion

Out of the 46 included articles, almost half were conducted in Europe, and a third of them in North America. One study included individuals from North America and Africa (Chamberlain et al., 2017). Diagnostic OCPD criteria in the studies were mostly based on DSM-IV (i.e., 26 studies were based on DSM-IV, 11 on ICD-10, 11 on DSM-III, and 2 on DSM-5). Four articles were based on two different criteria (i.e., DSM-IV and ICD-10). The Structured Clinical Interview for Axis II PD (SCID-II) was used in 15 studies; the International PD Examination (IPDE) was used in 9 studies, and the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire 4+ (PDQ-4+) was used in 5 studies.

The selected articles have been published from 1992 to 2018, with 6 of them from the 90s, 20 of them from the first 2000's decade, and 20 of them from the 2010s, as described in Table 3. Figure 6 shows that 6.9% (CI 95% = 4.5%–9.8%) of the general population was diagnosed with OCPD. Higher prevalences were found in clinical (16.2%), student (17.4%), prison (19.9%), and psychiatric (29.7%) samples. This lower prevalence in the general population was confirmed in the metaregression model (Table 4).

Table 3.

Methodological characteristics and geographic locations of the studies (N = 46).

| Variable | No. of Studies |

|---|---|

| Geographic location | |

| North America | 15∗ |

| Europe | 22 |

| Asia | 5 |

| South America | 0 |

| Oceania | 4 |

| Africa |

1∗ |

| Origin of Sample | |

| Community | 39 |

| Students |

7 |

| Diagnostic criteria | |

| ICD-10 | 11∗ |

| DSM-5 | 2 |

| DSM-IV | 26∗ |

| DSM-III |

11 |

| Decades | |

| 1900 | 6 |

| 2000 | 20 |

| 2010 | 20 |

Note. (∗) indicates studies that included more than one geographic locality and studies that included more than one diagnostic criterion, as explained in methodology.

Table 4.

Results of the meta-regression model for OCPD prevalence.

| Estimate | 95%CI | z | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 0.001 | -0.007 | 0.009 | 0.225 | 0.822 |

| Age | -0.005 | -0.010 | 0.000 | -2.105 | 0.035 |

| Female | -0.028 | -0.247 | 0.191 | -0.253 | 0.800 |

| Quality | -0.042 | -0.115 | 0.032 | -1.112 | 0.266 |

| Population (Reference = General) | |||||

| Clinical | 0.177 | 0.031 | 0.322 | 2.381 | 0.017 |

| Prison | 0.174 | -0.022 | 0.369 | 1.743 | 0.081 |

| Psychiatric | 0.282 | 0.133 | 0.431 | 3.702 | <0.001 |

| Student | -0.005 | -0.220 | 0.211 | -0.041 | 0.967 |

| Region (Reference = Americas) | |||||

| Asia | -0.055 | -0.321 | 0.210 | -0.409 | 0.683 |

| Europe | 0.019 | -0.097 | 0.135 | 0.321 | 0.748 |

| Oceania | 0.107 | -0.134 | 0.349 | 0.871 | 0.384 |

| Mixed | 0.581 | 0.055 | 1.106 | 2.166 | 0.030 |

| Criterion (Reference = DSM-IV) | |||||

| DSM-5 | 0.018 | -0.360 | 0.396 | 0.095 | 0.925 |

| DSM-III | -0.039 | -0.164 | 0.085 | -0.621 | 0.535 |

| ICD-10 | -0.013 | -0.183 | 0.158 | -0.144 | 0.886 |

| Mixed | -0.070 | -0.293 | 0.153 | -0.616 | 0.538 |

OCPD presented a stable prevalence throughout several countries of the world in the last 28 years; the geographic location was not associated with a significant difference in prevalence. The following prevalence rates were found in the subgroup analysis (Figure 7): 14.0% in Asia (five studies); 13.1% in Oceania (four studies); 13.7% in Europe (22 studies), and 9.9% in America (14 studies). These differences were not significant in the metaregression models (Table 4). Studies based on ICD-10 criteria (that showed an OCPD prevalence rate of 17.6%) or on DSM-IV (15.9%) reported higher OCPD prevalence rates than those based on DSM-III criteria (8.1%) (Figure 8). However, these differences were not significant in the metaregression model. The leave-one-out meta-analysis model (Figure 9) found no significant difference when each study was excluded.

Figure 9.

Leave-one-out

No gender-related effect was found in the meta-regression model (Table 4), but it has been reported that the prevalence rates of OCPD decreased with the age increase of the subjects. As found in the subgroup analysis, studies with the general population had significantly lower prevalences of OCPD than those with clinical populations. No significant differences were found among specific regions.

4. Discussion

We conducted a comprehensive systematic review of studies reporting OCPD prevalence rates worldwide and a meta-regression analysis to evaluate its estimation variability. Our results showed a global OCPD prevalence rate of 6.5%. Significant higher levels were found in clinical and psychiatric populations. Younger age was also correlated with higher levels of OCPD.

Among the included studies, a study published in 2002 utilized data from the U.S. National Epidemiological Research about Alcohol and Correlated Conditions, which included over 43,000 individuals in a nationally representative sample. It was the largest study included in this review: OCPD was the most prevalent PD among the general population, affecting 7.9% of the individuals during lifetime; prevalence rates of OCPD were practically the same in males and females but significantly less common in young adults (Grant et al., 2004). Our results corroborated this study since no gender-related effect has been found. However, we found that OCPD prevalence decreased with the age increase of studied subjects.

According to Tyrer et al. (2015), due to the complexity of PDs, their evaluation seems to be a difficult task in clinical practice. Diagnosis should be made out of a life-long disorder. PD affects the interaction with other people, and there are no biological markers or other independent markers for its identification. Considering the high prevalence rate for OCPD found in this review, we must conclude that the diagnostic instruments used to assess this disease are sensible to cross-sectionally assess OCPD signs and symptoms. However, they cannot properly assess OCPD throughout patients’ lives (Tyrer et al., 2015). In addition, OCPD construct comprehension is debated between categorical and dimensional approaches (Rojas and Widiger, 2017). According to Matthews et al. (2009), there was a split between the categorical classification system and the dimensional one based on traces (Matthews et al., 2009), in which the pathological traits increase with the severity of the dimensions (Tyrer and Johnson, 1996).

Diagnostic features of OCPD have been changing over the last decades (Pfohl and Blum, 1995; Costa et al., 2005). Thus, it is not surprising that the current rating scales conceptualize and evaluate OCPD differently. Nowadays, several different self-report measures include a scale for OCPD (McDermutt and Zimmerman, 2005) with a questionable convergent validity (Widiger and Boyd, 2009). According to the American Psychiatric Association (1952), DSM-I described a compulsive personality featured by overconcern “with adherence to standards of conscience or of conformity,” over inhibition, over conscientiousness, “an inordinate capacity for work,” rigidity, chronic tension, and a “lack (of) a normal capacity for relaxation” (American Psychiatric Association, 1952). There were no major changes in criteria from the first to the second edition of the manual (Pfohl and Blum, 1995; Costa et al., 2005). However, according to Douglas B. Samuel, DSM-III criteria did not include overconcern with morality, over conscientiousness, lack of capacity for relaxation, or chronic tension. DSM-III changed OCPD core feature to include a restricted capacity of expressing warm and tender emotions. All diagnostic criteria went through another substantial review for DSM-III-R since additional criteria were added to represent the original thrift, order, and obstinacy as constructs of the syndrome (Widiger et al., 1988). A generalized perfectionism pattern and inflexibility became the main characteristics (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). In the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), the restricted demonstration of emotions, a core feature in the DSM-III, was entirely removed from the diagnostic criteria alongside indecision (Pfohl and Blum, 1995). This would justify the results obtained in this study, as the lower prevalence rates based on DSM-III compared to those based on DSM-IV and ICD-10. Despite not finding significant differences in the meta-regression model, the present meta-analysis found higher prevalence rates in studies based on DSM-IV and ICD-10 when compared to those based on DSM-III. This may also suggest that the diagnostic threshold is lower with DSM-IV and ICD-10, leading to false-positive diagnoses.

As far as we know, this is the broadest systematic review about OCPD, including studies from far distant locations, the majority located in the Americas and Europe. The results showed that OCPD prevalence rates are stable worldwide. A few studies were conducted in Asia and Oceania (5 and 4, respectively), and no studies were found from Africa.

Our findings should be compared with the global prevalence data of other PD. According to DSM-5, the average prevalence rate of borderline PD (BPD) in the general population is around 1.6–5.9%, varying from primary care settings (6%), mental health outpatients centers (10%), and hospitalized psychiatric patients (20%) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). According to Wagner et al. (2013), BPD is a highly prevalent PD in the clinical setting with annual costs visibly higher than other mental and physical disorders: it has been estimated an average of approximately € 26.000 annually, when compared to depression (€2.900) and diabetes (€11.870), for example. Unfortunately, PD has not been included in the Global Burden of Disease Studies (Wagner et al., 2013; Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, 2017). We point out that it would be of great importance to estimate average costs generated by patients with OCPD, considering the impact on relational and work areas.

4.1. Limitations

Some limitations should be discussed. Firstly, our bibliographic research was limited to articles published in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Secondly, characteristics of countries involved, other than geographic location, were not analyzed. However, the geographical location of a country has been conceptually relevant for this study.

4.2. Conclusions

There was no significant variability in OCPD prevalence rates worldwide, affecting almost one over 15 adult individuals. Also, results indicate that more standardized epidemiological data on OCPD are needed. Future studies should also focus on the epidemiology of PD through the different classification systems, such as DSM-5 and ICD-11, and, in particular, on the DSM-5 alternate model, since only two studies were based on DSM-5 criteria (Moran et al., 2016; Bach et al., 2017). In addition, an evaluation based on a dimensional approach (Sharp et al., 2015), taking into account personality functioning and personality traits in healthy and clinically ill individuals, might be of interest (Volkert et al., 2018). Also, analytical factor studies are necessary to clarify which diagnostic features are relevant and how the prevalence of OCPD could be measured in a trustworthy manner. Finally, the present meta-analysis may suggest that the current diagnostic tools may detect OCPD in a cross-sectional assessment but not throughout the life of the person.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Marina Junqueira Clemente, Maria Olivia Pozzolo Pedro, Henrique Soares Paiva, Cintia de Azevedo Marques Périco, Julio Torales and Antonio Ventriglio: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Anderson Sousa Martins Silva: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

João Maurício Castaldelli-Maia: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- American Psychiatric Association . 1952. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . 1987. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) [Google Scholar]

- Ames A., Molinari V. Prevalence of personality disorders in community-living elderly. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. Neurol. 1994;7(3):189–194. doi: 10.1177/089198879400700311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderluh M.B., Tchanturia K., Rabe-Hesketh S., Treasure J. Childhood obsessive-compulsive personality traits in adult women with eating disorders: defining a broader eating disorder phenotype. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2003;160(2):242–247. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari Z., Fadardi J.S. Enhanced visual performance in obsessive compulsive personality disorder. Scand. J. Psychol. 2016;57(6):542–546. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aycicegi-Dinn A., Dinn W.M., Caldwell-Harris C.L. Obsessive-compulsive personality traits: compensatory response to executive function deficit? Int. J. Neurosci. 2009;119(4):600–608. doi: 10.1080/00207450802543783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach B., Sellbom M., Kongerslev M., Simonsen E., Krueger R.F., Mulder R. Deriving ICD-11 personality disorder domains from dsm-5 traits: initial attempt to harmonize two diagnostic systems. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2017;136(1):108–117. doi: 10.1111/acps.12748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett B., Byford S. Costs and outcomes of an intervention programme for offenders with personality disorders. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2012;200(4):336–341. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.068643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barendregt J.J., Doi S.A., Lee Y.Y., Norman R.E., Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J. Epidemiol. Community. 2013;67(11):974–978. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black D.W., Coryell W.H., Crowe R.R. Personality disorders, impulsiveness, and novelty seeking in persons with DSM-IV pathological gambling and their first-degree relatives. J. Gambl. Stud. 2015;31(4):1201–1214. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9505-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black D.W., Jr., R. N., Pfohl B., Goldstein R.B., Blum N. Personality disorder in obsessive-compulsive volunteers, well comparison subjects, and their first-degree relatives. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1993;150(8):1226–1232. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodlund O., Grann M., Ottosson H., Svanborg C. Validation of the self-report questionnaire DIP-Q in diagnosing DSM-IV personality disorders: a comparison of three psychiatric samples. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1998;97(6):433–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain S.R., Leppink E.W., Redden S.A., Stein D.J., Lochner C., Grant J.E. Impact of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) symptoms in Internet users. Ann. Clin. Psychiatr. 2017;29(3):173–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H., Huang Y., Liu B., Liu Z. Familial aggregation of personality disorder: epidemiological evidence from high school students 18 years and older in Beijing, China. Compr. Psychiatr. 2010;51(5):524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C., Zhang M., Ho R. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in medical students: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatr. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.760911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid J., Yang M., Tyrer P., Roberts A., Ullrich S. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2006;5(188):423–431. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolidge F.L., Marle P.D., Horn S.A., Segal D.L. Clinical syndromes, personality disorders, and neurocognitive differences in male and female inmates. Behav. Sci. Law. 2011;29(5):741–751. doi: 10.1002/bsl.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P., Samuels J., Bagby R.M., Daffin L., Norton H. In: Personality Disorders. Maj M., Akiskal H.S., Mezzich J.E., Okasha A., editors. Wiley and Sons; New York: 2005. Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder: a review. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford T.N., Cohen P., Johnson J.G., Kasen S., First M.B., Gordon K., Brook J.S. Self-reported personality disorder in the children in the community sample: convergent and prospective validity in late adolescence and adulthood. J. Pers. Disord. 2005;19(1):30–52. doi: 10.1521/pedi.19.1.30.62179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereboy C., Güzel H.S., Dereboy F., Okyay P., Eskin M. Personality disorders in a community sample in Turkey: prevalence, associated risk factors, temperament and character dimensions. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 2014;60(2):139–147. doi: 10.1177/0020764012471596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeburúa E., Medina R.B., Aizpiri J. Comorbidity of alcohol dependence and personality disorders: a comparative study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42(6):618–622. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekselius L., Tillfors M., Furmark T., Fredrikson M. Personality disorders in the general population: DSM-IV and ICD-10 defined prevalence as related to sociodemographic profile. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2001;30(2):311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Foo S.Q., Tam W.W., Ho C.S., Tran B.X., Nguyen L.H., McIntyre R.S., Ho R.C. Prevalence of depression among migrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2018;15(9):1986. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlenza O.V., Miguel E.C. Manoele Ltda; Barueri: 2014. Clínica Psiquiátrica de Bolso. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbard G.O. American Psychiatric Publishing; Virginia: 2014. Psychodyanmic Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Gawda B., Czubak K. Prevalence of personality disorders in a general population among men and women. Psychol. Rep. 2017;120(3):503–519. doi: 10.1177/0033294117692807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network . Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2017. Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 (GBD 2016): Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability 1990-2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grant B.F., Stinson F.S., Dawson D.A., Chou S.P., Ruan W.J., Pickering R.P. Co-Occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2004;61(4):361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha J.H., Kim E.J., Abbey S.E., Kim T.-S. Relationship between personality disorder symptoms and temperament in the young male general population of South Korea. Psychiatr. Clin. Neurosci. 2007;61(1):59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroeh U., Appleby L., Mortensen P.B., Dunn G. Death by homicide, suicide, and other unnatural causes in people with mental illness: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;358(9299):2110–2112. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idris N.R.N. Performance of the trim and fill method in adjusting for the publication bias in meta-analysis of continuous data. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2012;9(9):1512. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson H.J., Burgess P.M. Personality disorders in the community: a report from the Australian national survey of mental health and wellbeing. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2000;35(12):531–538. doi: 10.1007/s001270050276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalenques I., Rondepierre F., Massoubre C., Bonnefond S., Schwan R., Labeille B., Perrot J.-L., Collange M., Mulliez A., D'Incan M. High prevalence of personality disorders in skin-restricted lupus patients. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2017;97(8):941–946. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayhan F., Ilik F. Prevalence of personality disorders in patients with chronic migraine. Compr. Psychiatr. 2016;68:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempke S., Eede F.V., Schotte C., Claes S., Wambeke P.V., Houdenhove B.V., Luyten P. Prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: a controlled study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2013;20(2):219–228. doi: 10.1007/s12529-012-9273-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni R.R., Rao K.N., Begum S. Comorbidity of psychiatric and personality disorders in first suicide attempters: a case-control study. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2013;6(5):410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson J.O., Hellzén M. Patterns of personality disorders in women with chronic eating disorders. Eat. Weight Disord. 2004;9(3):200–205. doi: 10.1007/BF03325067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger M.F. Epidemiology of personality disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. 2008;31(3):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger M.F., Lane M.C., Loranger A.W., Kessler R.C. DSM-IV personality disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol. Psychiatr. 2007;62(6):553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K.S., Wong C.H., McIntyre R.S., Wang J., Zhang Z., Tran B.X., Tan W., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16(22):4581. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggini C., Ampollini P., Marchesi C., Gariboldi S., Cloninger C.R. Relationships between tridimensional personality questionnaire dimensions and DSM-III-R personality traits in Italian adolescents. Compr. Psychiatr. 2000;41(6):426–431. doi: 10.1053/comp.2000.16559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier W., Lichtermann D., Klingler T., Heun R., Hallmayer J. Prevalences of personality disorders (DSM-III-R) in the community. J. Pers. Disord. 1992;6(3):187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Mancebo M.C., Eisen J.L., Grant J.E., Rasmussen S.A. Obsessive compulsive personality disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder: clinical characteristics, diagnostic difficulties, and treatment. Ann. Clin. Psychiatr. 2005;17(4):197–204. doi: 10.1080/10401230500295305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews G., Deary I.J., Whiteman M. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2009. Personality Traits. [Google Scholar]

- McDermutt W., Zimmerman M. In: The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Bender D., Oldham J., Skodol A., editors. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington DC: 2005. Assessment instruments and standardized evaluation; pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Meleiro A.M. Guanabara Koogan Ltda; Rio de Janeiro: 2018. Psiquiatria Estudos Fundamentais. [Google Scholar]

- Mike A., King H., Oltmanns T.F., Jackson J.J. Obsessive, compulsive, and conscientious? The relationship between OCPD and personality. J. Pers. 2017;86(6):1–49. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldin S.O., Rice J.P., Erlenmeyer-Kimling L., Squires-Wheeler E. Latent structure of DSM-III-R Axis II psychopathology in a normal sample. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1994;103(2):259–266. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore E.A., Green M.J., Carr V.J. Comorbid personality traits in schizophrenia: prevalence and clinical characteristics. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012;46(3):353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran P., Coffey C., Mann A., Carlin J.B., Patton G.C. Personality and substance use disorders in young adults. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2006;188:374–379. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran P., Jenkins R., Tylee A., Blizard R., Mann A. The prevalence of personality disorder among UK primary care attenders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000;102(1):52–57. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102001052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran P., Romaniuk H., Coffey C., Chanen A., Degenhardt L., Borschmann R. The influence of personality disorder on the future mental health and social adjustment of young adults: a population-based, longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2016;3(7):636–645. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto M.R., Cols T.A. Artmed; 2011. Transtorno da personalidade. Porto Alegre. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti A., Luca A., Luca M., Donzuso G., Mostile G., Raciti L., Contrafatto D., Dibilio V., Sciacca G., Cicero C., Vasta R., Petralia A., Zappia M. Obsessive compulsive personality disorder in progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system Atrophy and essential tremor. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016;30:36–39. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraventi F., Chaves A.C. 2016. Manual de psiquiatria clínica. Rio de Janeiro: Roca. [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B., Blum N. In: The DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Livesley W.J., editor. Guilford; New York: 1995. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder; pp. 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Quirk S.E., Berk M., Pasco J.A., Brennan-Olsen S.L., Chanen A.M., Koivumaa-Honkanen H., Burke L.M., Jackson H.J., Hulbert C., Olsson C.A., Moran P., Stuart A.L., W L.J. The prevalence, age distribution and comorbidity of personality disorders in Australian women. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatr. 2017;51(2):141–150. doi: 10.1177/0004867416649032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts L.W. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019. Textbook of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas S.L., Widiger T.A. Coverage of the DSM-IV-TR/DSM-5 section II personality disorders with the DSM-5 dimensional trait model. J. Pers. Disord. 2017;31(4):462–482. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2016_30_262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadock B.J., Sadock V.A., Ruiz P. Wolters Kluer; Philadelphia: 2015. Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/clinical Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Sahingöz M., Uguz F., Gezginc K., Korucu D.G. Axis I and Axis II diagnoses in women with PCOS. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatr. 2013;35(5):508–511. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel D.B., Widiger T.A. Conscientiousness and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Personal. Disorders: Theory Res. Treat. 2011;2(3):161–174. doi: 10.1037/a0021216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels J.F., Nestadt G., Romanoski A.J., Folstein M.F., McHugh P.R. DSM-III personality disorders in the community. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1994;151(7):1055–1062. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels J., Eaton W.W., Bienvenu O.J., Brown C.H., Jr P.T., Nestadt G. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorders in a community sample. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2002;180:536–542. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.6.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana G.L., Coelho B.M., Wang Y.-P., Filho A.D., Viana M.C., Andrade L.H. The epidemiology of personality disorders in the Sao Paulo Megacity general population. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassoon S.A., Colrain I.M., Baker F.C. Personality disorders in women with severe premenstrual syndrome. Arch. Wom. Ment. Health. 2011;14(3):257–264. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C., Wright A.G., Fowler J.C., Frueh B.C., Allen J.G., Oldham J., Clark L.A. The structure of personality pathology: both general ('g') and specific ('s') factors? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2015;124(2):387–398. doi: 10.1037/abn0000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Lin L. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: practical guidelines and recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicine. 2019;98(23) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha B.K., Watson D.C. Personality disorder in university students: a multitrait-multimethod matrix study. J. Pers. Disord. 2001;15(3):235–244. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.3.235.19205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol A.E. Personality pathology and population health. Lancet Psychiatr. 2016;3(7):595–596. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeteman D.I., Roijen L.H.-v., Verheul R., Busschbach J.J. The economic burden of personality disorders in mental health care. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2008;59(2):259–265. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup D.F., Berlin J.A., Morton S.C., Olkin I., Williamson G.D., Rennie D.…Thacker S.B. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute . 2017. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies.https://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Analytical_Cross_Sectional_Studies2017_0.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Torgersen S., Kringlen E., Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2001;58(6):590–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres A.R., Moran P., Bebbington P., Brugha T., Bhugra D., Coid J.W., Farrell M., Jenkins R., Lewis G., Meltzer H., Prince M. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and personality disorder: evidence from the British national survey of psychiatric morbidity 2000. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006;41(11):862–867. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P., Johnson T. Establishing the severity of personality disorder. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1996;153(12):1593–1597. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P., Reed G.M., Crawford M.J. Classification, assessment, prevalence, and effect of personality disorder. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):717–726. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61995-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uguz F., Kucuk A., Cicek E., Kayhan F., Tunc R. Mood, anxiety and personality disorders in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Compr. Psychiatr. 2013;54(4):341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkert J., Gablonski T.-C., Rabung S. Prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2018;213(6):709–715. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner T., Roepke S., Marschall P., Stiglmayr C., Renneberg B., Gieb D., Matthies S., Salbach-Andrae H., Flessa S., Fydrich T. Krankheitskosten der Borderline Persönlichkeitsstörung aus gesellschaftlicher Perspektive. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie. 2013;42(4):242–255. [Google Scholar]

- Widiger T.A., Boyd S. In: Oxford Handbook of Personality Assessment. Butcher J.N., editor. Oxford University Press; New York: 2009. Assessing personality disorders; pp. 336–363. [Google Scholar]

- Widiger T.A., Frances A., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The DSM-III-R personality disorders: an overview. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1988;145(7):786–795. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.7.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongpakaran N., Wongpakaran T. Personality disorders in medical students: measuring by IPDE-10. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2005;88(9):1278–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Medical Arts; Porto Alegre: 1993. ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Ullrich S., Roberts A., Coid J. Childhood institutional care and personality disorder traits in adulthood: findings from the British national surveys of psychiatric morbidity. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(1):67–75. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz A., Cumurcu B.E., Etikan İ., Hasbek E., Doruk S. The effect of personality disorders on asthma severity and quality of life. Iran. J. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2014;13(1):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.