Abstract

Background:

Vascular intimal hyperplasia (IH) is one of the key challenges in the clinical application of small-diameter vascular grafts. Current tissue engineering strategies focus on vascularization and antithrombotics, yet few approaches have been developed to treat IH. Here, we designed a tissue-engineered vascular scaffold with portulaca flavonoid (PTF) composition and biomimetic architecture.

Method:

By electrospinning, PTF is integrated with biodegradable poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) into a bionic vascular scaffold. The structure and functions of the scaffolds were evaluated based on material characterization and cellular biocompatibility. Human vascular smooth muscle cells (HVSMCs) were cultured on scaffolds for up to 14 days.

Results:

The incorporation of PTF and preparation parameters during fabrication influences the morphology of the scaffold, including fibre diameter, structure, and orientation. Compared to the PCL scaffold, the scaffolds integrated with bioactive PTF show better hydrophilicity and degradability. HVSMCs seeded on the scaffold alongside the fibres exhibit fusiform-like shapes, indicating that the scaffold can provide contact guidance for cell morphology alterations. This study demonstrates that the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold inhibits the excessive proliferation of HVSMCs without causing cytotoxicity.

Conclusion:

The study provides insights into the problem of restenosis caused by IH. This engineered vascular scaffold with complex function and preparation is expected to be applied as a substitute for small-diameter vascular grafts.

Keywords: Tissue-engineered vascular scaffold, Electrospinning, Intimal hyperplasia

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of mortality worldwide, which results in approximately 17.9 million deaths each year according to a report by the World Health Organization [1, 2]. Due to atherosclerosis (AS) and intimal hyperplasia (IH), it is estimated that by 2030, there will be nearly 202 million and 23.3 million people suffering from peripheral artery and coronary heart diseases, respectively [3–5]. For severe coronary and peripheral artery disease, treatment options using autologous or prosthetic graft transplantation are necessary and recognized as the gold standard clinically [4, 6, 7]. This results in a great need for vascular grafts capable of replacing and in turn repairing the diseased tissue, especially small-diameter vasculature [8]. Historically, vascular grafts (Dacron® and e-PTFE® [9]) have been explored for clinical use, with advantages of low preparation cost, high mechanical strength, and ease of operation. However, due to the material’s nondegradability, low regenerative potential, and mismatched mechanics, grafts can result in an adverse immunological response, thrombosis, and poor long-term patency[10]. The tissue-engineered biodegradable vascular scaffold can reduce chronic inflammation and promote vascular repair and regeneration for effective treatment in various vascular diseases [11, 12]. For instance, a biodegradable small-diameter vascular scaffold with porous architecture and heparin modification demonstrated successful tissue reconstruction of injured arteries [13]. In 2018, Xeltis company researched and developed a small diameter artificial vascular graft that can be absorbed into the preclinical testing stage [14]. Thus, biodegradable vascular scaffolds have the potential to become a clinical alternative to small-diameter vascular grafts.

The extracellular matrix of vascular media is composed of circumferentially oriented and cross-linking collagen and elastin fibres. This special architecture plays an essential role in maintaining mechanical strength and providing guidance for cell infiltration and vascular tissue repair [7]. Therefore, for a tissue-engineered biodegradable vascular scaffold, it is important to consider the structure and orientation depending on the extracellular matrix. At present, there are many studies on the construction of bionic vascular scaffolds [15]. Tamara et al. fabricated a vascular graft with native-inspired arrangements of poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) submicron fibres, which obtained a J-shaped mechanical response and compliance similar to human arteries [16]. Zhu et al. prepared an electrospun PCL scaffold composed of circumferentially oriented microfibres [17, 18]. However, these vascular scaffolds did not achieve the microstructure of the human extracellular matrix, which was constructed with net-like fibrous cross-linking.

On the other hand, avoiding stenosis of the small-diameter vascular scaffolds remains challenging due to the occurrence of severe AS and IH [11, 17, 19]. Studies have shown that human vascular smooth muscle cells (HVSMCs) play a significant role in IH, resulting in stenosis after excessive proliferation [20]. Under pathophysiological conditions, HVSMCs can be transformed into secretory or macrophage types and migrate to the intima to undergo proliferation or phagocytosis, which leads to vascular intima lesions [7]. A variety of medicines, such as nitric oxide (NO), MAKP inhibitory peptide (MK2i), and Chinese medicines, have been used to prevent vascular restenosis. For example, to prevent IH, Evans et al. [21] utilized MK2i and constructed MK2i NPs for scaffold modification to prevent the uncontrollable proliferation of HVSMCs. Wang et al. [22] prepared a vascular graft that can release NO sustainably and proved that it can inhibit AS. However, these methods have not achieved the desired objective of inhibiting IH, and it is difficult to ensure the stability of protein properties.

Flavones, as natural products, are well known for their biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anti-allergic, and antioxidant activities. In recent studies, researchers have proven that portulaca flavones (PTFs) can significantly inhibit IH and the formation of atherosclerotic stenosis [23–25]. It has been reported that flavones can inhibit the abnormal proliferation of VSMCs induced by platelet-derived growth factor (PBGF-BB) and inhibit the formation of atherosclerotic stenosis [26, 27]. Presently, PTF has not been applied for engineering functional vascular scaffolds.

In this work, we present the development of a small-diameter vascular scaffold with a combination of PTF loading and bionic fibrous alignment to provide contact guidance and growth control for HVSMCs. We established a biomimetic tissue-engineered vascular scaffold by electrospinning using a mixture of PCL and PTF. The results highlight the capability of the scaffold to inhibit excessive proliferation of HVSMCs established by the application of PTF. This system exhibited a significant enhancement of microstructural reconstruction of the extracellular matrix and mechanical matching between vascular scaffolds and natural vasculature. This study therefore provides insights into scaffold design with the integration of physicochemical matrix cues for regulating the proliferation of HVSMCs to inhibit IH.

Materials and methods

Materials

Polycaprolactone (PCL, MW = 80,000), ethanol, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and dichloromethane (DCM) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Portulaca total flavone (PTF) was provided by Hunan University of Chinese Medicine. Dulbecco's modified eagle’s medium (DMEM), foetal bovine serum (FBS), trypsin–EDTA (0.25%), penicillin–streptomycin solution (PS), AlamarBlue® medium, and flasks (75 mL, Nunc) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China). Cell culture plates (24 wells) were purchased from SuRui (Hangzhou, China). Fluorescein-diacetate (FDA), propidium iodide (PI), paraformaldehyde solution (PFA, 4%), and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from Solarbio Life Science (Beijing, China).

Fabrication of engineered vascular scaffolds

Tissue-engineered vascular scaffolds were fabricated through the previously described method of electrospinning [28]. Briefly, PTF powder (0, 0.025, 0.05, and 0.1 g) was dissolved in deionized water (200 ml) and ultrasonically dissolved for 20 min to obtain a solution. Ethanol (1.3 ml) and DCM (3.5 ml) were then added and subjected to ultrasonic dissolving for 20 min to obtain suspensions at different concentrations of PTF. Finally, PCL (0.5 g) was added to the suspensions, followed by ultrasonic dissolution to obtain a stable homogeneous PCL/PTF electrospinning solution.

For the fabrication of tubular scaffolds, a steel stick (4 mm in diameter) was used as a collector, with different rotating speeds of 0, 100, and 1000 rpm. Electrospinning was performed using predetermined parameters: needle size of 25 G, voltage of 12 kV, feed rate of 12 ml/min, collection distance of 9 cm, room temperature, and humidity of 60–80%. For testing, all the samples were peeled off from the steel stick and placed in a vacuum oven for one week to remove potential solvent residuals.

Material characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) The surface morphology of PCL/PTF (0%, 4.8%, 9.1%, and 16.7%) scaffolds was examined by field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, MIRA3 LMH, TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic). Briefly, testing samples were cut into 5 × 5 mm2 pieces and attached to the metal sample table with a conductive adhesive cloth. The samples were sputter-coated with gold at a current of 6 mA for 90 s. Images were taken at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV at different magnifications at three random areas on each sample. The images (fibre orientation and fibre diameter) were analysed with the built-in functions of ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD, USA). At least 50 fibres in each SEM image and three images of each sample were used to determine the average fibre diameter.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) characterization The crystal structures of the materials were determined by XRD (D8 Advance, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). Briefly, samples of the PTF powders, PCL scaffold, and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold were all loaded onto a flat plate (Size: 1 × 1 cm2). The test was performed under atmospheric conditions using Cu-Ka radiation in the scanning region of 2θ (10 − 80°) and a scanning speed of 2°/min. Data were collected step-by-step (Step width: 0.02° and lasting time: 1.2 s). Phase identification was carried out by comparing the diffraction patterns of the testing samples to the ICDD (JCPDS) standards of PCL and PTF. The structural parameters of the as-fabricated scaffolds were determined by Rietveld refinement of the X-ray diffraction data using Jade (MDI, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) characterization Material compositions were analysed using FTIR (NICOLET iS10, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). The experimental group included the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds. PCL scaffolds and PTF powder were used as control groups. Briefly, the samples were cut into 5 × 5 mm2 sections. The spectra of the samples were obtained by using FTIR in ATR mode in the range of 4000–400 cm−1. Finally, the composition of the material was analysed using the characteristic absorption peak of the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectra.

Water contact angle (WCA) Surface wettability was evaluated using a water contact angle (WCA) system (Contact Angle Analyser, SDC-200S, ShengDing, Dongguan, China). Briefly, PCL/PTF scaffolds with different percentages of PTF (0%, 4.8%, 9.1%, and 16.7%) were cut into rectangular strips (10 × 10 mm2) and loaded on glass slides to make the surface flat. To investigate surface dynamic hydrophilicity, images of WCAs were captured at 0, 10, 20, 30, and 40 s after the droplets contacted the sample’s surface. A water droplet of 1.0 μl was used, and 3 random positions of each sample were tested along the direction of fibre organization. Five samples were used for each investigation group.

Mechanical properties Mechanical properties of the as-fabricated scaffolds were investigated using a tensile testing machine (HYC-2011, Hongjin, Dongguan, China). Briefly, samples were cut into rectangular strips with dimensions of 10 mm (length) × 5 mm (width). The testing gauge length was 5 mm. The sample thickness was measured at three random positions via a digital micrometer (0–25 mm, Meinaite, Germany). Testing was performed at a pulling rate of 5 mm/min with a loading force of 100 N at room temperature. The PCL/PTF scaffolds containing different amounts of PTF (0%, 4.8%, 9.1%, and 16.7%) were tested along the transverse direction. In addition, PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds with different rotation speeds of 0, 100, and 1000 rpm were investigated along both the transverse and longitudinal directions. In this part, at least 5 samples were tested in each group, of which three curves were selected randomly to draw the stress–strain curve. An offset strain of 0.5% was used for all of the testing samples to determine their yield points.

Material degradation properties

To investigate the degradation properties, samples were degraded in a sodium hydroxide solution and weighed at predetermined times (0 d, 0.5 d, 1 d, 2 d, 4 d, and 8 d). Briefly, PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds with random fibres and PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds with aligned fibres were investigated. Samples (1 × 2 cm) were weighed to obtain the initial weights (W0) and incubated in a sodium hydroxide solution (5 mL, 0.5 mol/l) at room temperature. Then, the samples were imaged and rinsed with deionized water three times and air dried for 1 week to obtain the weights (Wd). The degradation degree of the as-fabricated scaffolds was presented as a percentage of weight loss and calculated using the following equation:

Five samples from each group were used at each predetermined time point.

Cell culture

Human vascular smooth muscle cells (HVSMC, China) were provided by Dr. Huang Mei from Central South University. Cell culture was performed at 37 °C with 5% CO2 using a flask containing D10 medium (DMEM + 10% FBS + 1% PS). The medium was changed every 3 days. Cells were passaged after reaching ~ 70% confluence using 0.25% trypsin and used between passages 3 and 5.

Live and dead cell staining

Cellular cytotoxicity was examined using live/dead cell staining as described previously [29]. Briefly, samples were cut into squares (1 × 1 cm) and disinfected using 75% ethanol. PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds with random fibres and PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds with aligned fibres were investigated. Cells were seeded on the samples at a density of 5 × 103/cm2. After 1 and 14 days of culture, the cells were incubated in sequence with FDA (4 mg/mL in PBS, 8 min) and PI (5 mg/mL in PBS, 5 min) solutions at room temperature. The samples were then washed three times with PBS and visualized immediately by a fluorescence inverted microscope (DMI3000, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Live and dead cells were identified as FDA-labelled green and PI-labelled red colours, respectively.

Cellular metabolism

Cellular metabolism was examined using an alamarBlue® assay as reported [29]. Briefly, PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds with random fibres and PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds with aligned fibres were cut into squares (1 × 1 cm2). Samples were disinfected using 75% ethanol. HVSMCs were seeded on the samples at a density of 5 × 103/cm2 and cultured on D10 for 1, 3, 7, and 14 days. At each time point, the cells were incubated with alamarBlue® medium (alamarBlue® medium: D10, 1:9) for 4 h. Detection of the cell supernatant was performed using a microplate reader (2300, EnSpire, Singapore) at 570 (A570, absorbance wavelength) and 600 (A600, reference wavelength) nm. Cell metabolism was calculated by the relative absorbance intensity as follows:

where the control group refers to the alamarBlue® testing medium without a cell suspension. Five replicates were tested for each group at all time points.

Cellular adhesion and morphology

Cellular adhesion and morphology were investigated using SEM characterization [29]. Briefly, PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds with random fibres and PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds with aligned fibres were cut into squares (1 × 1 cm2). Samples were disinfected using 75% ethanol. HVSMCs were seeded onto the samples at a density of 5 × 103/cm2. After 1 and 14 days of culture, the cells were fixed with PFA (4%) for 30 min. The cells were then dehydrated with an increasingly concentrated series of ethanol solutions (10, 30, 50, 70, 90, and 100%). For SEM characterization, the samples were coated with gold (6 mA, 90 s). Cellular distribution, adhesion, and morphology on the luminal surface of scaffolds were captured by SEM at 2000 × and 10,000 × magnifications to analyse the influence of the surface micro pattern.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Prism 9 Software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical comparisons between the two groups were based on Student’s paired t test with a two-tailed distribution. At least five samples were taken for both materials and biological measurements. The results were reported as the mean ± SD. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Fabrication of vascular scaffold

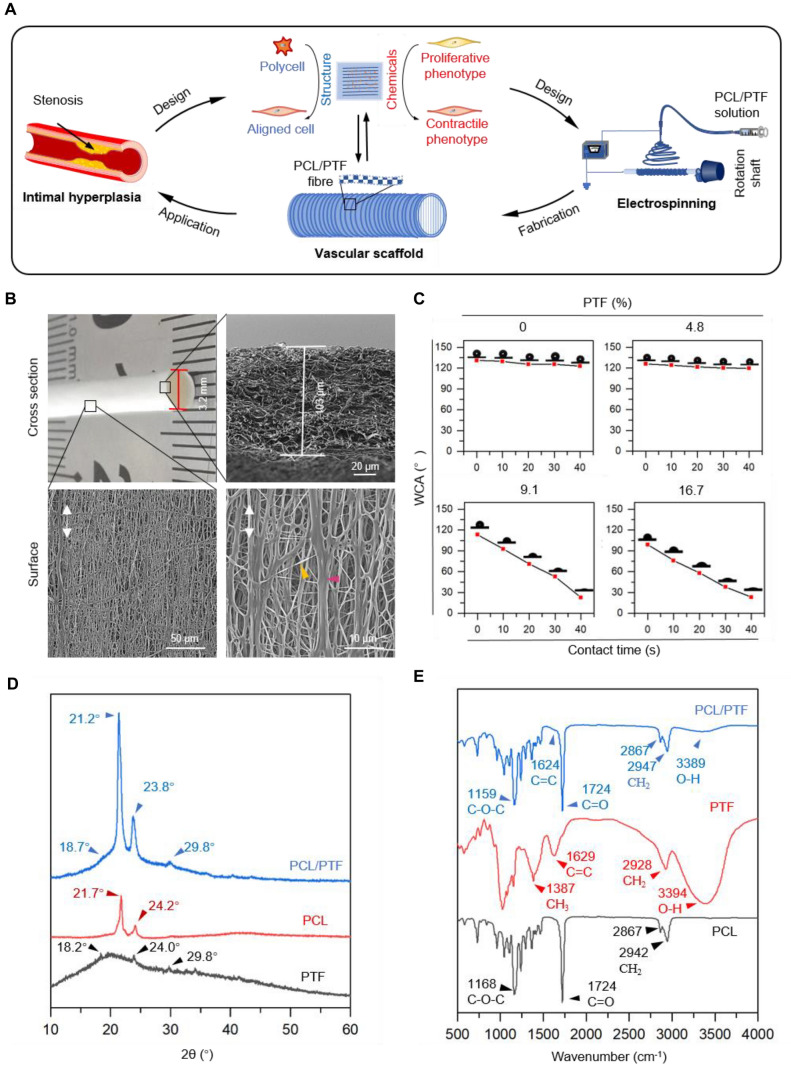

The bionic vascular scaffold was fabricated as shown in Fig. 1A. The cross-section of the as-fabricated PCL/PTF (9.1%) vascular scaffold shows an inner diameter of ~ 3.2 mm (Fig. 1B). The SEM image shows a wall thickness of ~ 103 μm and an interconnected porous fibre structure in the cross-section of the scaffold. The scaffold’s internal surface shows a net-like fibre structure consisting of aligned fibres and cross-linked fine fibres. The oriented fibres constitute the majority of the scaffold, while the fine fibres constitute the cross-linked structure.

Fig. 1.

A Schematic illustration shows the design and fabrication of the engineered vascular scaffold. The scaffold is designed with circumferentially aligned fibres that are fabricated from PCL/PTF (9.1%) composite by electrospinning (PCL, polycaprolactone; PTF, portulaca total flavone). B Microstructure of the as-fabricated scaffold. The scaffold shows a well-organized tubular structure with an inner diameter of 3.2 mm and a thickness of 103 μm. The microstructure of the inner surface shows that the fibres have oriented and reticulated structures. (1 k × and 5 k ×) C Surface hydrophilicity/water contact angles (WCAs) of the as-fabricated scaffolds with different weights of PTF (0%, 4.8%, 9.1%, and 16.7%). D X-ray diffraction pattern of the as-fabricated PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds showing the crystalline peaks assigned to PCL and PTF. E Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectra of the as-fabricated PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds showing characteristic absorbance peaks of PCL and PTF

Figure 1C shows the surface hydrophilicity of the as-fabricated scaffold with different PTF percentages. The PCL scaffold shows a surface WCA of 127.1°, which experiences no obvious changes within the testing period of 40 s, suggesting the hydrophobic nature of PCL. With the increase in PTF content, the vascular scaffold at 4.8% PTF showed a decreased WCA of 119.5°. When the percentage of PTF increased by 9.1% and 16.7%, the scaffolds showed a significant enhancement in hydrophilicity, with WCAs of 29.6° and 20.5°, respectively.

Figure 1D shows the XRD pattern of the PCL scaffold, which shows distinct crystalline 2θ peaks at 21.7° and 24.2° corresponding to the (110) and (200) reflection planes, respectively. The XRD pattern of PTF powder shows a very weak broad peak at a 2θ of approximately 20° and three weak peaks at 18.2°, 24.0° and 29.8°. Comparatively, the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold exhibits broad diffraction 2θ peaks at 18.7° and 29.8° similar to those of the PTF powder. The characteristic 2θ peaks of PCL shifted to lower values of 21.2° and 23.8° in the PCL/PTF scaffold, respectively. There was no generation of new peaks for the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold.

Figure 1E shows the FTIR spectra of the PCL, PTF, and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds. The characteristic absorbance peaks of the PCL scaffold are at 2942, 1724, and 1168 cm−1, corresponding to the CH2, C = O, and C–O–C groups, respectively [30]. The spectra of PTF show typical peaks at 3394, 1629, and 1387 cm−1 corresponding to the O–H, C = C, and CH3 groups, respectively. The FTIR spectrum of the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold has typical PCL absorbance peaks at 2947, 1724, and 1159 cm−1 corresponding to CH2, C = O, and C–O–C groups, respectively. Low absorbance peaks at approximately 3389 and 1624 cm−1 were observed in the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold spectra due to the O–H and C = C groups.

Effects of PTF on scaffold morphology

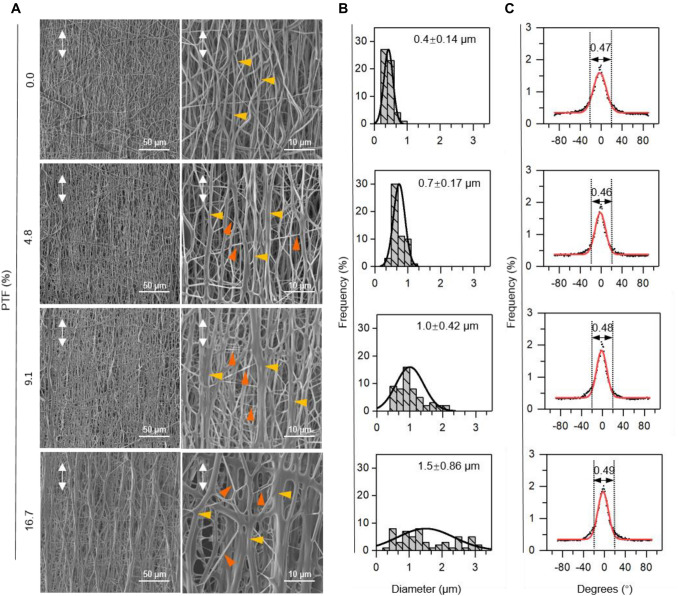

SEM images show that the scaffolds containing different percentages of PTF had smooth surfaces and obtained aligned fibre arrangements (Fig. 2A). Specifically, the SEM image of the PCL/PTF (0%) scaffold shows a smaller gap between fibres and uniform fibre diameter than in the other groups. There were no obvious net-like fibres on the scaffold. As the PTF percentage increased, hybrid fibres and net-like fibre structures appeared on the PCL/PTF (4.8% and 9.1%) scaffold surface. There were larger pores and more net-like fibres in the PCL/PTF (16.7%) scaffold surface than in the other groups. Diameter analysis (Fig. 2B) shows that the PCL/PTF (0%, 4.8%, 9.1%, and 16.7%) scaffolds have average fibre diameters of 0.4, 0.7, 1.0, and 1.5 μm, respectively. In addition, it is worth noting that the fibre diameter frequency shows two peaks in the diameter analysis of the PCL/PTF (16.7%) scaffold. Figure 2C shows the fibre orientation analysis of electrospun scaffolds with different percentages of PTF. Fibre orientation analysis showed that 46% ~ 49% of fibres of each group were all arranged within − 20° ~ 20°. The frequency of fibre orientation on all scaffold surfaces exhibited a peak at approximately 0°. This result indicated that most of the fibres aligned towards the main direction along the scaffold’s circumferential orientation.

Fig. 2.

Morphology of the as-fabricated scaffolds at different concentrations of PTF. A SEM images (1 k × and 5 k ×) showing that scaffolds have reticular crosslinked structures as the PTF concentration increases. B, C Fibre diameter analysis shows that the fibre diameter increases with increasing PTF concentration. Fibre orientation analysis shows aligned fibre distribution and no obvious difference between different groups. The white arrows represent the fiber direction of scaffolds; The yellow arrows represent oriented fibers; The red arrows represent the crosslinked fibrous structures

Mechanical properties of as-fabricated vascular scaffolds

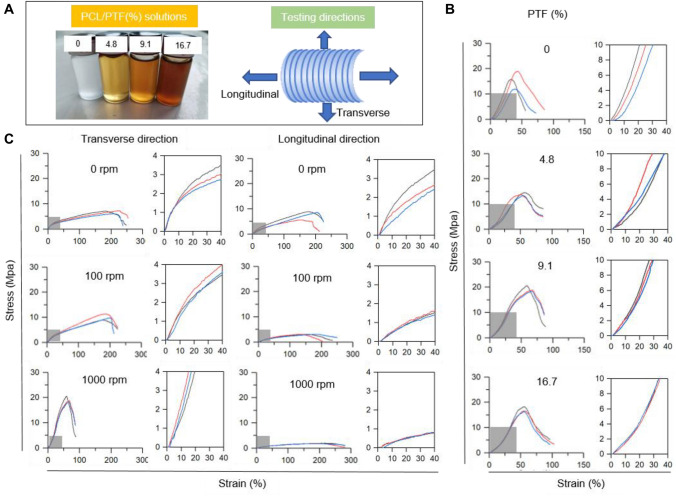

Figure 3A shows the appearance of spinning solution with different PTF concentration incorporation and the testing directions for as-fabricated vascular scaffolds. Figure 3B shows the stress–strain curves of the as-fabricated PCL/PTF scaffolds with different percentages of PTF (0%, 4.8%, 9.1%, and 16.7%). In the amplified pictures, the stress–strain curves of all PCL/PTF scaffolds present “J-shaped” behaviours in the elastic deformation stage. Quantitatively, with the increase in PTF percentage, the Young’s modulus of PCL/PTF scaffolds in the circumference direction was decreased (Table 1). The yield tensile strength, ultimate strength and break strain of PCL/PTF scaffolds tended to increase.

Fig. 3.

Mechanical properties of as-fabricated scaffolds. A The scheme illustrates the preparation and mechanics of the vascular scaffold. B Stress–strain curves of the scaffold at different concentrations of PTF. Testing was in a transverse direction. C Stress–strain curves of the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold at rotating speeds of 0, 100, and 1000 rpm. Testing was performed along both the transverse and longitudinal directions

Table 1.

The effects of PTF percentages on the mechanical properties of the scaffolds (n = 3)

| PTF(%) | Young’s modulus (MPa) | Yield stress (MPa) | Yield strain (%) | Ultimate stress (MPa) | Break strain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 24.9 ± 1.0 | 12.2 ± 2.2 | 28.5 ± 2.0 | 15.5 ± 2.9 | 39.3 ± 4.3 |

| 4.8 | 17.7 ± 4.9 | 9.8 ± 0.5 | 34.2 ± 5.1 | 13.9 ± 0.5 | 54.8 ± 1.3 |

| 9.1 | 19.3 ± 3.6 | 13.5 ± 3.1 | 39.8 ± 3.3 | 17.7 ± 2.5 | 66.6 ± 5.5 |

| 16.7 | 14.9 ± 2.2 | 17.6 ± 6.9 | 43.3 ± 5.0 | 17.1 ± 1.0 | 56.8 ± 0.4 |

*Testing was performed along the transverse direction of scaffolds

Figure 3C shows the stress–strain curves of PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds tested along the transverse and longitudinal directions, which exhibits the effects of different rotation speeds of 0, 100, and 1000 rpm. The increase in rotating speed resulted in a “J-shaped” elastic deformation in the stress–strain curve of the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold in the transverse direction. Specifically, in the transverse test direction, with the increase in uniaxial drawing (from 0 to 1000 rpm), the scaffolds’ Young's modulus, yield strength, yield strain, and ultimate stress tended to increase, and break strain tended to decrease. Without mechanical drawing during fibrogenesis, the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold (0 rpm) exhibited stress–strain curves that were similar in both the transverse and longitudinal directions, suggesting isotropic mechanics. With increased rotating speeds (from 100 to 1000 rpm), the scaffold’s Young's modulus and ultimate stress along the transverse direction were higher than those in the longitudinal direction (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of the PCL/PTF (9.1%) vascular scaffold along the transverse and longitudinal directions (n = 3)

| Rotating rate (rpm) | Testing direction | Young’s modulus (MPa) | Yield stress (MPa) | Yield strain (%) | Ultimate stress (MPa) | Break strain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | T* | 11.6 ± 2.4 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 22.7 ± 4.5 | 7.9 ± 1.6 | 184.9 ± 31.1 |

| L** | 11.2 ± 2.0 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 23.6 ± 5.5 | 6.8 ± 0.5 | 206.8 ± 17.0 | |

| 100 | T* | 16.7 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 25.7 ± 4.7 | 9.9 ± 1.0 | 186.7 ± 9.7 |

| L** | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 63.3 ± 9.5 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 158.9 ± 20.6 | |

| 1000 | T* | 19.3 ± 3.6 | 13.5 ± 3.1 | 39.8 ± 3.3 | 17.7 ± 2.5 | 66.6 ± 5.5 |

| L** | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 80.4 ± 18.7 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 197.9 ± 12.9 |

T* represents the scaffold’s transverse direction

L** Representing the scaffold longitudinal direction

Degradability of the as-fabricated scaffold

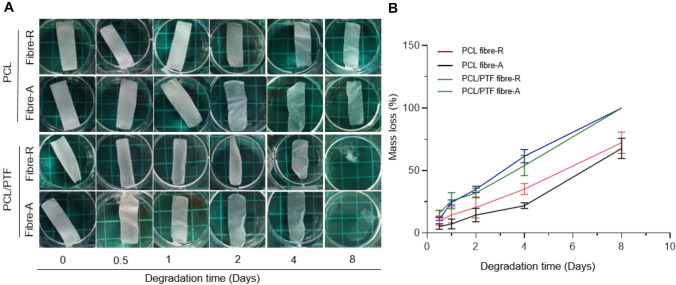

To study the degradation behaviours of the as-fabricated scaffolds, Fig. 4A shows the effects of PTF incorporation and fibre arrangement. After 8 days of immersion, vascular scaffolds showed different degrees of degradation. Images show that the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds degraded faster than the PCL scaffolds. There was no obvious difference between the scaffolds only with different fibre arrangements. Figure 4B shows the effects of PTF incorporation and fibre arrangement on scaffold degradation. The PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds exhibited a higher mass loss than the PCL scaffolds at 8 days. This may be due to the increase in hydrophilicity of the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold and the change in crystallinity after the combination of PTF.

Fig. 4.

Degradation properties of the as-fabricated scaffold. A Morphological changes show the effects of fibre composition and organization on scaffold degradation. B Mass loss of the scaffolds shows the effects of fibre composition and organization on the scaffold degradation rate

Cellular biocompatibility and morphology

Here, FDA/PI staining was used to evaluate live/dead HVSMCs after culturing on scaffolds, as shown in Fig. 5A. The cells cultured on all the scaffold surfaces exhibited nearly 100% FDA-stained live cells, without the presence of PI-stained dead cells. This suggests that PTF incorporation induced no cell cytotoxicity. In addition, after 1 day of culture, the live (green) cells exhibited an even distribution on the surfaces of all PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds compared with the PCL scaffold. This is probably because the PTF/PCL (9.1%) scaffolds have better hydrophilicity, which is beneficial to cell adhesion. After 14 days of culture, the images show that the live (green) cells covered the surface of all the scaffolds. In addition, the density of live (green) cells was lower on PCL/PTF scaffolds than on PCL scaffolds. This indicates the different cell proliferation of HVSMCs on the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold and PCL scaffold.

Fig. 5.

Cell compatibility of the as-fabricated scaffold. A FDA/PI staining showing FDA-labelled live (green) and PI-labelled dead cells (5 k/cm2) seeded on PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds and cultured for 1 and 14 days (R, random; A, aligned). B Metabolism levels of the cells on PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds after 1, 3, 7, and 14 days of culturing. C Cellular morphologies on PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds after 1 and 14 days of culturing. The white arrows represent the fiber direction of scaffolds; The yellow arrows represent the cells’ protrusions along the fibre; The red arrows represent Human vascular smooth muscle cells (HVSMC) cultured on the scaffolds. A FDA/PI staining showing PI-labelled dead (red) cells. But there were no red stained cells on the stained samples. The reason is that there are no dead cells on our samples or dead cells are shed in the process of staining. This phenomenon is explained in the discussion section

The alamarBlue® assay was used to measure the metabolism levels of HVSMCs cultured on as-fabricated vascular scaffolds. As shown in Fig. 5B, HVSMCs showed increased metabolism levels after culturing in all groups. After 1, 3, and 7 days of culture, the test results showed that the metabolic activity of HVMCs on different scaffolds was not significantly different. The prolonged culture resulted in lower metabolic levels for the cells after 14 days of culturing on PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds compared to that of the PCL scaffolds. This indicates an inhibition in the cellular proliferation of HVSMCs on the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold surface. The metabolism of HVSMCs on aligned and randomly electrospun scaffolds showed no significant difference.

Figure 5C shows the morphology of HVSMCs grown on vascular scaffolds. After 1 day of culturing, HVSMCs cultured on PCL and PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds exhibited different morphologies, where the cells exhibited spreading adhesion on PCL/PTF (9.1%) fibres with more protrusions, while the cells possessed a round and oval morphology on PCL fibres. This may be attributed to the better hydrophilicity of PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffolds than PCL scaffolds. HVSMCs on aligned fibres tended to elongate along the fibres and show fusiform-like shapes. In contrast, the cells on random fibre scaffolds were polygon-like in shape. After 14 days of culture, the number of HVSMCs increased on all scaffold surfaces and tended to spread out along with alignment to form a cell sheet. In contrast, the cells were scattered on the random fibre scaffolds. These results indicate that the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold with biomimetic fibre structures could provide contact guidance for HVSMC growth.

Discussion

The biological functions of tissue engineering scaffolds have been extensively explored through the incorporation of medicines [19]. IH and restenosis are still important clinical problems for vascular scaffolds. To date, there is no perfect solution to inhibit vascular IH after vascular transplantation. Excessive proliferation and phenotypic changes in HVSMCs are considered to be important causes of IH [11]. Some Chinese medicines can regulate the proliferation and differentiation of HVSMCs, which has the potential to solve the problem of IH of small-diameter vascular scaffolds [11, 12]. As a component of flavonoids, PTF is well known for its function of inhibiting intimal hyperplasia and atherosclerosis caused by abnormal proliferation of HVSMCs [26, 27]. It can inhibit the abnormal proliferation of HVSMCs induced by platelet-derived growth factor (PBGF-BB) and inhibit the formation of atherosclerotic stenosis [26, 27]. Thus, we fabricated an engineered vascular scaffold that integrated PTF composition.

Anatomically, the extracellular matrix in a vascular medium is composed of circumferentially oriented and cross-linked collagen/elastin fibres, which play an essential role in maintaining mechanical strength and guiding cell infiltration [7]. Inspired by this, we designed an engineered vascular scaffold comprising physical and chemical cues (Fig. 1A). Material characterizations suggested that the PTF did not undergo chemical changes after being loaded in the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold, indicating the retention of bioactivity of PTF. Regarding the structure, characterization results showed that the scaffold exhibited biomimetic net-like fibre structures organizing along with a preferential anisotropy similar to the extracellular matrix of a vascular smooth muscle layer. These results indicate that the scaffold’s chemical and microstructure cues were engineered by electrospinning into the flavone-modified biomimetic architecture.

Mismatching of mechanical properties between natural arteries and vascular scaffolds can affect haemodynamics, which results in neointimal hyperplasia and restenosis [31]. Studies indicate that vascular grafts are suitable for vascular application, which requires an elastic modulus of 2–20 MPa, ultimate tensile stress > 2 MPa, and fracture strain > 60% in the transverse direction [32, 33]. For electrospinning vascular scaffolds, the fibre shape, structure, and alignment are crucial for maintaining appropriate mechanical properties. Therefore, we explored how PTF incorporation and fibre alignment influence the mechanical properties of the as-fabricated vascular scaffolds. The incorporation of PTF resulted in a reduction in the Young’s modulus of PCL/PTF scaffolds, indicating that the addition of PTF makes the scaffolds more flexible. With the increase in the rotation rate, the mechanical tension promoted the increased stretching of the fibres and their tendency to organize along the scaffolds’ circumferential direction. This allowed the mechanical properties of the as-fabricated scaffold to present a J-shaped stress–strain curve in the transverse direction and thereby match natural arteries [34].

The material degradation property is a key factor affecting the performance of tissue-engineered vascular scaffolds. PCL, as a widely used scaffolding material, shows slower degradation, which hinders cell infiltration into the scaffold, thereby inhibiting vessel regeneration [35, 36]. Zhao et al. found that the slow degradation properties of PCL grafts resulted in their limited biocompatibility and prolonged inflammation [37]. Meanwhile, the slow degradability of PCL was reported to cause the failure of artificial vascular scaffolds after transplantation in vivo [38]. Here, due to the addition of PTF, the scaffold obtained improved degradability compared with pure PCL scaffolds. This may be attributed to the addition of PTF significantly improving the hydrophilicity of the vascular scaffold, which promotes the hydrolysis process of a vascular scaffold. However, the actual degradation time of the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold cannot be shown in this experiment.

In this study, HVSMCs were cultured on vascular scaffolds for up to 14 days. With contact guidance by the scaffold’s bionic fibres, the cells cultured on the PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold obtained a contractile-function related morphology, with elongated fusiform-like shapes along the fibres. The PCL/PTF (9.1%) scaffold showed growth control of HVSMCs without causing any cytotoxicity, which has the potential to solve the problem of intimal hyperplasia for small-diameter vascular scaffolds. This engineered vascular scaffold with complex function and preparation is expected to be applied as a substitute for vascular grafts.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (S2011J5043). This research was supported partially by the Hunan Provincial Technology Innovation Platform and Talent Program (2017XK2047), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (531107050927). ZW received financial support from Hunan University for the Yuelu Young Scholars (JY-Q/008/2016).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Ethical statement

No human or animal experiments were carried out in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xianwei Wang, Email: wangxianweilq@163.com.

Ziyu Liu, Email: lzytcm@163.com.

Zuyong Wang, Email: wangzy@hnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale C, Grobbee R, Maniadakis N, Flather M, Wilkins E, Wright L, Vos R, Bax J, Blum M, Pinto F, Vardas P, Group ESCSD. European society of cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2017. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:508–579. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khatib R, McKee M, Shannon H, Chow C, Rangarajan S, Teo K, Wei L, Mony P, Mohan V, Gupta R, Kumar R, Vijayakumar K, Lear SA, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Lanas F, Yusoff K, Ismail N, Kazmi K, Rahman O, Rosengren A, Monsef N, Kelishadi R, Kruger A, Puoane T, Szuba A, Chifamba J, Temizhan A, Dagenais G, Gafni A, Yusuf S. Availability and affordability of cardiovascular disease medicines and their effect on use in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: an analysis of the PURE study data. Lancet. 2016;387:61–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Jordan LC, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, Lewis TT, Lichtman JH, Longenecker CT, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Martin SS, Matsushita K, Moran AE, Mussolino ME, O'Flaherty M, Pandey A, Perak AM, Rosamond WD, Roth GA, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Stokes A, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Turakhia MP, VanWagner LB, Wilkins JT, Wong SS, Virani SS, American Heart Association Council on E, Prevention Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e66. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander JH, Smith PK. Coronary-artery bypass grafting. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1954–1964. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Costa F, Jeppsson A, Juni P, Kastrati A, Kolh P, Mauri L, Montalescot G, Neumann FJ, Petricevic M, Roffi M, Steg PG, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Levine GN, Group ESCSD, Guidelines ESCCFP, Societies ESCNC 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:213–260. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink MEL, Bjorck M, Brodmann M, Cohnert T, Collet JP, Czerny M, De Carlo M, Debus S, Espinola-Klein C, Kahan T, Kownator S, Mazzolai L, Naylor AR, Roffi M, Rother J, Sprynger M, Tendera M, Tepe G, Venermo M, Vlachopoulos C, Desormais I, Group ESCSD. 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesEndorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO)The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:763–816. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durham AL, Speer MY, Scatena M, Giachelli CM, Shanahan CM. Role of smooth muscle cells in vascular calcification: implications in atherosclerosis and arterial stiffness. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:590–600. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stowell CET, Wang Y. Quickening: Translational design of resorbable synthetic vascular grafts. Biomaterials. 2018;173:71–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuzaki Y, John K, Shoji T, Shinoka T. The evolution of tissue engineered vascular graft technologies: from preclinical trials to advancing patient care. Appl Sci (Basel). 2019;9:1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Skovrind I, Harvald EB, Juul Belling H, Jorgensen CD, Lindholt JS, Andersen DC. Concise review: patency of small-diameter tissue-engineered vascular grafts: a meta-analysis of preclinical trials. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2019;8:671–680. doi: 10.1002/sctm.18-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei Y, Wu Y, Zhao R, Zhang K, Midgley AC, Kong D, Li Z, Zhao Q. MSC-derived sEVs enhance patency and inhibit calcification of synthetic vascular grafts by immunomodulation in a rat model of hyperlipidemia. Biomaterials. 2019;204:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z, Liu C, Zhu D, Gu X, Xu Y, Qin Q, Dong N, Zhang S, Wang J. Untangling the co-effects of oriented nanotopography and sustained anticoagulation in a biomimetic intima on neovessel remodeling. Biomaterials. 2019;231:119654. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu W, Allen RA, Wang Y. Fast-degrading elastomer enables rapid remodeling of a cell-free synthetic graft into a neoartery. Nat Med. 2012;18:1148–1153. doi: 10.1038/nm.2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xeltis. A novel bioabsorbable vascular graft in modified fontan procedure mid-term results. 2018. http://www.xeltis.com/technology/.

- 15.Arora S, Lin S, Cheung C, Yim EKF, Toh YC. Topography elicits distinct phenotypes and functions in human primary and stem cell derived endothelial cells. Biomaterials. 2020;234:119747. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akentjew TL, Terraza C, Suazo C, Maksimcuka J, Wilkens CA, Vargas F, Zavala G, Ocana M, Enrione J, Garcia-Herrera CM, Valenzuela LM, Blaker JJ, Khoury M, Acevedo JP. Rapid fabrication of reinforced and cell-laden vascular grafts structurally inspired by human coronary arteries. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3098. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu M, Wang Z, Zhang J, Wang L, Yang X, Chen J, Fan G, Ji S, Xing C, Wang K, Zhao Q, Zhu Y, Kong D, Wang L. Circumferentially aligned fibers guided functional neoartery regeneration in vivo. Biomaterials. 2015;61:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi B, Shen Y, Tang H, Wang X, Li B, Zhang Y. Stiffness of Aligned Fibers Regulates the Phenotypic Expression of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:6867–6880. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Ma B, Yin A, Zhang B, Luo R, Pan J, Wang Y. Polycaprolactone vascular graft with epigallocatechin gallate embedded sandwiched layer-by-layer functionalization for enhanced antithrombogenicity and anti-inflammation. J Control Release. 2020;320:226–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett MR, Sinha S, Owens GK. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:692–702. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans BC, Hocking KM, Osgood MJ, Voskresensky I, Dmowska J, Kilchrist KV, Brophy CM, Duvall CL. MK2 inhibitory peptide delivered in nanopolyplexes prevents vascular graft intimal hyperplasia. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:291ra95. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Lu Y, Qin K, Wu Y, Tian Y, Wang J, Zhang J, Hou J, Cui Y, Wang K, Shen J, Xu Q, Kong D, Zhao Q. Enzyme-functionalized vascular grafts catalyze in-situ release of nitric oxide from exogenous NO prodrug. J Control Release. 2015;210:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.05.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verma AK, Pratap R. The biological potential of flavones. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:1571–1593. doi: 10.1039/c004698c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hostetler GL, Ralston RA, Schwartz SJ. Flavones: Food Sources. Bioavailability, Metabolism, and Bioactivity, Adv Nutr. 2017;8:423–435. doi: 10.3945/an.116.012948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farag MA, Shakour ZTA. Metabolomics driven analysis of 11 Portulaca leaf taxa as analysed via UPLC-ESI-MS/MS and chemometrics. Phytochemistry. 2019;161:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan S, Tang Q, Liu W, Zhu R, Li B. Nobiletin Inhibits PDGF-BB-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration and attenuates neointimal hyperplasia in a rat carotid artery injury model. Drug Dev Res. 2014;75:489–496. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu K, Al-Ani MK, Pan X, Chi Q, Dong N, Qiu X. Plant-Derived Products for Treatment of Vascular Intima Hyperplasia Selectively Inhibit Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Functions. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:3549312. doi: 10.1155/2018/3549312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SJ, Liu J, Oh SH, Soker S, Atala A, Yoo JJ. Development of a composite vascular scaffolding system that withstands physiological vascular conditions. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2891–2898. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang ZY, Teoh SH, Johana NB, Khoon Chong MS, Teo EY, Hong MH, Yen Chan JK, San Thian E. Enhancing mesenchymal stem cell response using uniaxially stretched poly(epsilon-caprolactone) film micropatterns for vascular tissue engineering application. J Mater Chem B. 2014;2:5898–5909. doi: 10.1039/C4TB00522H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domingues RM, Chiera S, Gershovich P, Motta A, Reis RL, Gomes ME. Enhancing the Biomechanical Performance of Anisotropic Nanofibrous Scaffolds in Tendon Tissue Engineering: Reinforcement with Cellulose Nanocrystals. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5:1364–1375. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201501048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarkar S, Salacinski HJ, Hamilton G, Seifalian AM. The mechanical properties of infrainguinal vascular bypass grafts: their role in influencing patency. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:627–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasan A, Memic A, Annabi N, Hossain M, Paul A, Dokmeci MR, Dehghani F, Khademhosseini A. Electrospun scaffolds for tissue engineering of vascular grafts. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norouzi SK, Shamloo A. Bilayered heparinized vascular graft fabricated by combining electrospinning and freeze drying methods. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;94:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karimi A, Navidbakhsh M, Shojaei A, Faghihi S. Measurement of the uniaxial mechanical properties of healthy and atherosclerotic human coronary arteries. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2013;33:2550–2554. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim CH, Khil MS, Kim HY, Lee HU, Jahng KY. An improved hydrophilicity via electrospinning for enhanced cell attachment and proliferation. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006;78:283–290. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siddiqui N, Asawa S, Birru B, Baadhe R, Rao S. PCL-Based Composite Scaffold Matrices for Tissue Engineering Applications. Mol Biotechnol. 2018;60:506–532. doi: 10.1007/s12033-018-0084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao L, Li X, Yang L, Sun L, Mu S, Zong H, Li Q, Wang F, Song S, Yang C, Zhao C, Chen H, Zhang R, Wang S, Dong Y, Zhang Q. Evaluation of remodeling and regeneration of electrospun PCL/fibrin vascular grafts in vivo. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;118:111441. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.111441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, Cui Y, Wang J, Yang X, Wu Y, Wang K, Gao X, Li D, Li Y, Zheng XL, Zhu Y, Kong D, Zhao Q. The effect of thick fibers and large pores of electrospun poly(epsilon-caprolactone) vascular grafts on macrophage polarization and arterial regeneration. Biomaterials. 2014;35:5700–5710. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]