Summary

Background

Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, have traditionally used the kānuka tree as part of their healing system, Rongoā Māori, and the oil from the kānuka tree has demonstratable anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial properties. This trial investigated the efficacy and safety of a 3% kānuka oil (KO) cream compared to vehicle control (VC) for the topical treatment of eczema. The trial was conducted through a nationwide community pharmacy research network.

Methods

This single-blind, parallel-group, randomised, vehicle-controlled trial was undertaken in 11 research trained community pharmacies across New Zealand. Eighty adult participants with self-reported moderate-to-severe eczema, assessed by Patient Orientated Eczema Measure (POEM) were randomised by blinded investigators to apply 3% KO cream or VC topically, twice daily, for six weeks. Randomisation was stratified by site and eczema severity, moderate versus severe. Primary outcome was difference in POEM scores at week six between groups by intention to treat. The study is registered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ANZCTR) reference number, ACTRN12618001754235.

Findings

Eighty participants were recruited between 17 May 2019 and 10 May 2021 (41 KO group, 39 VC group). Mean POEM score (standard deviation) improved between baseline and week six for KO group, 18·4 (4·4) to 6·8 (5·5), and VC group, 18·7 (4·5) to 9·8 (6·5); mean difference between groups (95% confidence interval) was -3·1 (-6·0 to -0·2), p = 0·036. There were three adverse events reported in the KO group related to the intervention and two in the control group.

Interpretation

The KO group had a significant improvement in POEM score compared to VC. Rates of adverse events and withdrawals were similar between groups with no serious adverse events reported. Treatment acceptability was high for both groups across all domains. Our results suggest that in adults with moderate-to-severe eczema, the addition of KO to a daily emollient regimen led to a reduction in POEM score compared to VC. KO may represent an effective, safe, and well tolerated treatment for moderate-to-severe eczema in adults.

Funding

Hikurangi Bioactives (Ruatoria, New Zealand) and HoneyLab (Tauranga, New Zealand), supported by a grant from Callaghan Innovation.

Keywords: Dermatology, Eczema, Dermatitis, Kānuka, Decentralised

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Prior to this study being conducted there were no randomised controlled trials on the use of kānuka oil for dermatological conditions. Existing in vitro evidence identified anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory properties of kānuka oil. Alongside were reports in scientific literature of traditional use of the kānuka tree by Māori for inflammatory conditions as part of the traditional healing system known as Rongoā Māori.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first randomised controlled trial to assess the therapeutic benefit of kānuka oil for a dermatological condition. The findings suggest an efficacy for reducing the frequency of eczema symptoms experienced by patients.

Implications of all the available evidence

Existing mechanistic data combined with the efficacy demonstrated in this study support the use of an emollient containing kānuka oil as a treatment option for eczema.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Eczema typically presents as a chronic, relapsing, pruritic rash affecting children and adults.1, 2, 3 In a 2010 global burden of disease survey, eczema ranked second in disability-adjusted life-years when compared to other common skin conditions.4 Patients and their families experience significant quality of life impact and financial burden from eczema.5,6 Patients often experience significant sleep disturbance caused by itching as well as limitations to their social life and everyday activities.5 A study assessing out of pocket cost for eczema patients across nine European countries found an average out of pocket cost of 927 euros (1,585 New Zealand Dollars) per year per patient with the primary cost purchase of emollients and moisturisers.6

Eczema lesions develop due to an impaired skin barrier, leading to exposure to environmental allergens which triggers a heightened cutaneous T-helper cell mediated immune response.7 There is no known cure for eczema and current treatments focus instead on long term symptom management, and disease control.7, 8, 9 Treatment is often based on the cyclical nature of the disease, with maintenance use of emollients and moisturisers to maintain skin integrity.7,8,10 Topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors, are typically used to dampen the inflammation that occurs during exacerbations, but they can also be used as a maintenance therapy.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 If topical anti-inflammatory treatments prove ineffective then phototherapy and systemic immune modulating therapies may be considered.7,8,10 Eczema lesions are also prone to secondary infection potentially resulting in the need for antiseptic or antibiotic therapy.7,8 Poor treatment adherence is a key reason for treatment failure in eczema,7,8,10 a particular issue for topical corticosteroids due to a negative patient perception around side effects.7, 8, 9, 10,13 Providing patients with novel non-steroidal options may be viewed more favourably, and lead to improved treatment adherence.

Usage of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is increasing globally and is common in patients with eczema.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 However, there is often no evidence of efficacy or limited data from inadequately powered clinical trials.15 New Zealand (NZ) ranks high globally in terms of prevalence of eczema in both children and adolescents, with the indigenous peoples, Māori, disproportionately affected.19,20 Māori have traditionally used the kānuka tree (Kunzea ericoides) to treat disease, including using the exudate of the tree for inflammatory conditions, as part of a traditional healing system, Rongoā Māori.21, 22, 23 The kānuka tree is endemic to NZ and its oil extract, characterized by high levels of a-pinene and p-cymene, has demonstrable anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antifungal properties.21,24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 These properties may confer prophylactic and therapeutic benefit for both the inflamed lesions and potential secondary infections.7 A study by Chen et al identified that kānuka oil significantly decreased the production of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) by antigen presenting cells.28 TNF-α has been shown to stimulate the T helper 2 (Th2) cell and T helper 17 (Th17) cell inflammatory response, both of which are involved in the development of eczema lesions.7,28,30 In vivo, kānuka oil may reduce T-cell mediated inflammation in eczematous skin.

Given the widespread use of CAM, both in NZ and internationally, and the pre-clinical evidence for an anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial effect for kānuka oil, there is an opportunity for a novel, steroid sparing, topical treatment for eczema.22,31 This randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigated the participant reported efficacy of kānuka oil in the topical treatment of moderate-to-severe eczema, through a nationwide community pharmacy based research network.

Methods

Study design

This study was a single blind, parallel group, superiority RCT in a community setting. The aim was to assess the efficacy of a 3% kānuka oil cream compared to vehicle control in adults with self-reported eczema. This study was conducted using the Medical Research Institute of New Zealand (MRINZ) Pharmacy Research Network (PRN), an established network of over 80 research trained community pharmacists in NZ overseen centrally by researchers at the MRINZ. Eleven pharmacies were selected to undertake all study related procedures. Recruitment of the 80 participants was done through social media advertising and opportunistic recruitment upon presentation to a study pharmacy. A small number of follow up visits were conducted remotely by MRINZ central investigators due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) restrictions during the study period.

Individual participation lasted eight weeks and involved two in-person pharmacy visits at baseline and week six, with a follow up by digital survey or telephone at week eight. Participants also completed weekly diaries.

Ethics Committee approval was obtained from the national Health and Disabilities Ethics Committee (HDEC) on the 5th of November 2018 (ref: 18/CEN/152). The Standing Committee on Therapeutic Trials (SCOTT) granted approval on the 21st of December 2018 (ref: 18/SCOTT/124).

Participants

All participants gave written informed consent to participate. Eligible participants were aged 18 to 65 years with a self-reported doctor's diagnosis of eczema. Other criteria included a Patient Orientated Eczema Measure (POEM) score between 8 (moderate eczema) and 24 (severe eczema), a presenting area of eczema below the clavicle the participant was comfortable to have photographed, willingness to replace all moisturiser and barrier creams with randomised treatment, and willingness to replace all soaps and body washes with supplied aqueous cream.32

Participants were required to have moderate to severe eczema in order to ensure the study had a higher chance of detecting a significant change in POEM score. Additionally, this criterion prevented a floor effect from occurring if the participant's eczema was too mild to improve beyond a certain point.

Exclusion criteria included use of any systemic or topical antibiotic, corticosteroid, antihistamine, or calcineurin inhibitor during the four weeks prior to enrolment. Additional exclusion criteria focused on other skin conditions which may have affected the assessment of the participants eczema. Specific exclusion criteria related to the COVID-19 pandemic were added partway through the study to ensure the safety of participants and investigators. These included a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, known contact with a COVID-19 positive case within the past 28 days, or current cold/flu like symptoms in the 14 days prior to screening.

Randomisation and masking

Participants were electronically randomised 1:1 with block size four, according to a statistician generated schedule with stratification by site and by severity of eczema as determined by POEM categories (moderate and severe).32 Participants were randomised by the pharmacy investigators who had no access to the randomisation schedule.

Active treatment and vehicle control were labelled by the MRINZ unblinded study pharmacist with ‘Treatment A’ and ‘Treatment B’ respectively. Only the unblinded MRINZ pharmacist knew which treatment was the active and which was the control. Investigators both at the MRINZ and at the pharmacies had no access to the randomisation schedule and were not told which label corresponded to which treatment. Participants were only told they were randomised to ‘Treatment A’ or ‘Treatment B’ and were not told if they received the active or control. However, kānuka oil has a distinctive smell which could not be matched in the control and may have resulted in participants determining their randomised treatment. The risk of participants being unblinded due to this smell was acknowledged by the study team and led to this study being conservatively classified as single blind rather than double blind.

Procedures

Active treatment was a 3% kānuka oil cream and comparator was vehicle control, identical in composition but not containing kānuka oil. Both treatments were expected to confer emollient effects through the ingredients of the base cream. Previous unpublished pre-clinical work undertaken by the sponsor had indicated that 3% kānuka oil would be sufficient to see antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus Aureus.

The kānuka oil was extracted by Hikurangi Bioactives Limited Partnership in the East Coast/Tairāwhiti region of NZ, and compounded into study treatments by Zealand Health Manufacturing, Tauranga, NZ. Both creams were manufactured to nutraceutical good manufacturing processes.

Participants were dispensed two 500g bottles of study treatment for liberal application to affected areas twice daily, morning and night, during the six-week study period. In addition, three 500g tubs of aqueous cream (Boucher & Muir Pty Ltd, Auckland NZ) were supplied to replace soap and body wash.

Potentially eligible participants were screened using a predefined summary statement and POEM score review followed by digital signing of the Participant Information Sheet and Consent Form (PIS-CF). Full inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed, eczema severity scores recorded, and a photograph of the representative eczema lesion taken using a custom clinical photography function within REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), which was also used to collect the study data.33 Following randomisation, enrolled participants were dispensed their allocated treatment and aqueous cream. Participants completed weekly, electronic diaries for five weeks assessing treatment compliance, adverse events, concomitant medication use, and POEM score. Paper back up diaries were available to all participants. Participants returned to the pharmacy six weeks after their first visit for investigator assessment of eczema severity and final recording of participant reported outcomes. At week eight, participants were emailed a follow up survey assessing adverse events and qualitative feedback.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was subjective symptoms at week six, as assessed by the difference in POEM scores.32, 34 The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of POEM, as calculated by Schram et al for adult populations, is 3.4 units with a standard deviation (SD) of 4.8.35 The POEM assesses eczema severity by asking about the frequency of symptoms over the last week and scores can range from 0 to 28, with a higher score indicating more severe eczema. The POEM score can be broken down into the following categories: Clear/Almost Clear (0-2); Mild (3-7); Moderate (8-16); Severe (17-24); Very Severe (25-28).

Secondary outcomes included the proportion of participants with a POEM score improvement ≥4, termed responders; Patient Oriented SCOring Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD) scores at Week Six; and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores at Week Six.36, 37, 38, 39, 40 The PO-SCORAD is a self-assessment of eczema severity with scores ranging from 0 to 103, higher scores indicate more severe eczema. The DLQI, an assessment of quality of life in adults with skin diseases, has a maximum score of 30 and a minimum of 0, higher scores indicate a greater impairment of quality of life.

Participant reported acceptability of treatment was assessed using the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) Version II, broken down into effectiveness, side effects, convenience, and global satisfaction domains.41 Each domain has a score range of 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating higher treatment satisfaction.

Treatment safety was assessed by comparing proportions of withdrawals due to worsening eczema, proportions of participants requiring treatment escalation, and proportions of cutaneous and systemic adverse events deemed to be related, or probably related, to randomised treatment.

Exploratory outcomes compared the scoring of the intensity section of the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) by the study pharmacists in person with the scores from the study dermatologist who scored remotely from clinical photographs.42

Statistical analysis

The MCID of 3·4 (SD of 4·8) for the change in POEM score was used to calculate the sample size.35 Both the MCID and SD were obtained from a paper by Schram et al and calculated using two studies in an adult population with severe eczema. Thirty-two participants in each treatment group were required to detect a difference between treatment groups with 80% power at 5% two-sided alpha. Accounting for an assumed withdrawal rate of 20%, based on previous community studies and the likelihood of symptom flares, the sample size was calculated to be 80 participants.43,44

Continuous data was summarised by mean, SD, median, inter-quartile range, and minimum to maximum. Categorical variables were summarised by counts and proportions expressed as percentages. The primary outcome of POEM scores at week six was analysed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with baseline POEM score as a continuous co-variate, treatment escalation as a categorical covariate, and randomised treatment as a categorical variable of interest. Participants who experienced an adverse event of worsening acne that led to withdrawal, or required corticosteroids or antibiotics to treat were deemed to have required treatment escalation.

The main analysis was by intention to treat (ITT) including all randomised participants with data. A per protocol (PP) analysis of the primary outcome for those with data was also undertaken that included all participants who: were eligible for the study; did not withdraw or get withdrawn from study; provided data at every time point; adhered to treatment instructions, as measured by ≥50% adherence; and did not use any concomitant medication. Adherence was measured as the number of days a participant reported exactly two uses a day. Both over adherent and under adherent participants were excluded from the PP analysis. The PP analysis used ANCOVA adjusted for baseline POEM score.

The proportion of participants with a ≥4-point improvement in POEM score (‘responders’) between baseline and week six, proportion of treatment escalations, and proportion of withdrawals for worsening eczema between groups was by estimation of relative risk (RR) and a Chi-square test. The difference in PO-SCORAD and DLQI scores at week six was assessed by ANCOVA with respective baseline measurements and randomised treatment as explanatory variables. A sub analysis of the POEM score was undertaken to assess any influence on the primary outcome due to COVID-19 behavioural changes, such as increased hand washing. The other continuous outcomes were analysed by ANCOVA with adjustment for baseline score and randomisation status. Change from baseline for each group was analysed by a paired t-test. Acceptability was measured by TSQM Version II over four domains: global acceptability, convenience, effectiveness, and side effects. The domains were compared between treatment groups using a t-test. Total and related adverse events were compared by Poisson regression for number of events and by estimation of RR and Chi-square test for the proportion of participants with at least one reported adverse event.

Agreement between the pharmacists and the study dermatologist scoring of SCORAD elements for baseline and week six was assessed using a generalised mixed linear model to estimate odds ratio for one assessor type versus the other, with the probability of rating the participants clinical response higher versus lower. The SCORAD element scores, the ordinal scales assessing each dimension of the response, were treated as a multinomial response with a cumulative logit specification, assessor type as a fixed effect and participant as a random effect, taking into account repeated measurements on the individual participant.

SAS version 9·4 was used for the analysis.

Registration

The study was prospectively registered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ANZCTR) on the 25th of October 2018 (ref: ACTRN12618001754235).

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, or reporting of this trial. All authors, both internal and external, were independent from the funders and were not precluded from accessing data in the study. Nicholas Shortt, Alexander Martin, Iva Vakalalabure, Kyley Kerse, Luke Barker, Joseph Singer, and Alex Semprini had full access to the study data. Nicholas Shortt and Alex Semprini had final responsibility to submit for publication.

Results

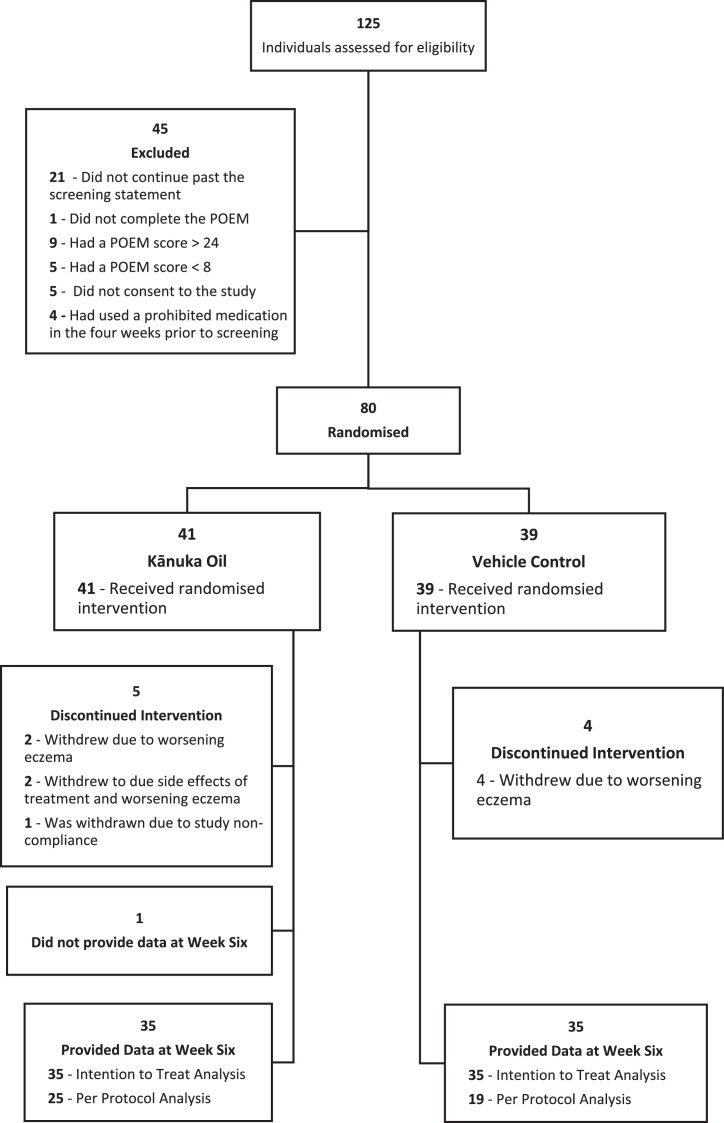

Of the 125 people screened for eligibility, 80 were eligible and were randomised to treatment (Figure 1). Forty-one participants were randomised to the kānuka oil and 39 to the vehicle control. Recruitment occurred between the 17th of May 2019 and the 10th of May 2021.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow diagram.

Study participation by treatment group. Patient Orientated Eczema Measure (POEM) score between 8 and 24 indicated eligibility.

The study population (Table 1) was predominantly female (74%) with a mean (SD) age of 33 (11·36). Characteristics of the two randomised groups were very similar. Nine participants discontinued the intervention during the study for worsening eczema, treatment side effects, or non-compliance. One participant completed the study but did not provide data for the POEM, PO-SCORAD, and TSQM measure at week six due to COVID-19 restrictions (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| All | Kānuka oil | Vehicle control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 80 | n = 41 | n = 39 | |

| Continuous variables | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| [Range] | [Range] | [Range] | |

| Age | 33·0 (11·4) | 35·1 (13·2) | 30·8 (8·7) |

| [18–65] | [18–65] | [18–51] | |

| Categorical variables | N/80 (%) | N/41 (%) | N/39 (%) |

| Sex, Femalea | 59 (73·8) | 29 (70·7) | 30 (76·9) |

| Ethnicitya | |||

| • Asian | 6 (7·5) | 2 (4·9) | 4 (10·3) |

| • European | 52 (65·0) | 27 (65·9) | 25 (64·1) |

| • Māori | 20 (25·0) | 10 (24·4) | 10 (25·6) |

| • Pacific peoples | 2 (2·5) | 2 (4·9) | 0 (0) |

| Recruited during COVID-19 pandemicb | 27 (33·8) | 14 (34·2) | 13 (33·3) |

Self-reported.

The start of this period was defined by the date that New Zealand first started ‘level 4’ restrictions.

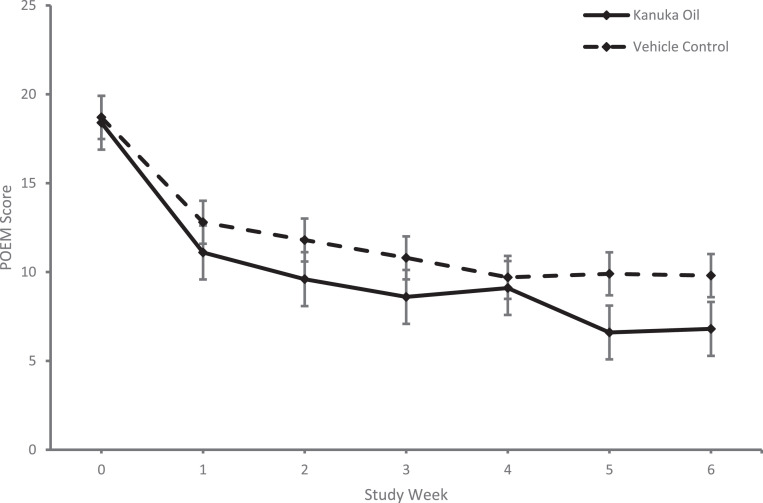

For the primary outcome there was a statistically significant difference in the mean week six POEM score between groups (Table 2) with a mean (SD) POEM score of 6·8 (5·5) for the kānuka oil group and 9·8 (6·5) for the vehicle control group, mean difference (95% Confidence Interval [CI]) -3·1 (-6·0 to -0·2), p = 0·036. This outcome data along with the other weekly POEM scores are shown in Figure 2. When the scores were analysed per protocol there was no significant difference between groups (Table 2). 43 participants were included in this per protocol analysis (Figure 1). 24 of these participants received kānuka oil and 19 vehicle control. The per protocol kānuka oil group had a mean (SD) POEM score of 6·4 (5·6) and the per protocol vehicle control group had a mean (SD) POEM score of 7·9 (5·9). There was a mean difference (95% CI) of -1·4 (-5·0 to 2·2), p = 0·43.

Table 2.

Poem scores – data are reported as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified.

| Baseline |

Week six |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of analysis | Kānuka oil | Vehicle control | Kānuka oil | Vehicle control | Mean difference (95% CI) p-value |

| Intention to treat | 18·4 (4·4) n = 41 |

18·7 (4·5) n = 39 |

6·8 (5·5) n = 35 |

9·8 (6·5) n = 35 |

−3·1 (−6·0 to −0·2) p = 0·036a |

| Per protocol | 18·4 (4·4) n = 41 |

18·7 (4·5) n = 39 |

6·4 (5·6) n = 24 |

7·9 (5·9) n = 19 |

−1·4 (−5·0 to 2·2) p = 0·43b |

POEM = Patient Orientated Eczema Measure.

ANCOVA adjusted for baseline POEM score, need for treatment escalation, and randomised treatment.

ANCOVA adjusted for baseline POEM score, and randomised treatment.

Figure 2.

Comparison of weekly mean Patient Orientated Eczema Measure (POEM) scores between treatment groups. Weekly Patient Orientated Eczema Measure (POEM) scores compared between treatment groups. Kānuka oil group represented by solid line and vehicle control group represented by dashed line. Error bars represent standard error.

There was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of responders between treatment groups. With a responder defined as a participant that had a ≥4-point improvement in POEM score at week six compared to baseline. The kānuka oil group had 33 responders (94·3%) and vehicle control group had 27 (77·1%) RR 1·2 (95% CI 1·0 to 1·5), p = 0·04 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Efficacy & acceptability outcome measures - Data are reported as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified.

| Baseline |

Week six |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measure | Kānuka oil n = 41 | Vehicle control n = 39 | Kānuka oil n = 35 | Vehicle control n = 35 | Relative risk (95% CI) p-value | |

| Poem – number of responders (N [%]) | .. | .. | 33 (94·3) | 27 (77·1) | 1·2 (1·0 to 1·5) p = 0·040 |

|

| Mean difference (95% CI)p-value | ||||||

| PO-SCORAD | 44·2 (11·1) | 42.0 (12.8) | 24·8 (15·8) | 26·9 (15·2) | −2·9 (−10·0 to 4·1) p = 0·41 |

|

| DLQI | 9·9 (5·7) | 11·4 (5·5) | 4·0 (4·3) | 5·5 (4·5) | −1·0 (−3·1 to 1·0) p = 0·32 |

|

| TSQM VII | Global | ·· | ·· | 69·3 (24·2) | 61·9 (31·1) | 7·4 (−5·9 to 20·7) p = 0·27 |

| Effectiveness | ·· | ·· | 63·3 (23·0) | 54·5 (29·8) | 8·8 (−3·9 to 21·5) p = 0·17 |

|

| Convenience | ·· | ·· | 81·6 (13·7) | 81·4 (19·1) | 0·16 (−7·8 to 8·1) p = 0·97 |

|

| Side effects | ·· | ·· | 98·8 (5·0) | 96·4 (16·0) | 2·4 (−3·3 to 8·1) p = 0·40 |

|

POEM = Patient Orientated Outcome Measure.

PO-SCORAD = Patient Orientated Scoring Atopic Dermatitis.

DLQI = Dermatology Life Quality Index.

TSQM vII = Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication version II.

For the PO-SCORAD there was no statistically significant difference between treatment groups at Week Six. The mean (SD) for the kānuka oil group was 24·8 (15·8) and 26·9 (15·2) for the vehicle control group. The mean difference between treatment groups was -2·9 (95% CI -10·0 to 4·1), p = 0·41 (Table 3).

For change in DLQI scores at week six from baseline, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups with a mean (SD) change of -5·4 (5·1) for the kānuka oil group and -5·8 (6·7) for the vehicle control group (not shown). The mean difference between treatment groups was -1·0 (95% CI -3·1 to 1·0), p = 0·32 (Table 3). Of note, the mean change in both groups exceeded the MCID of 4·0 for the DLQI.39

There was no statistically significant difference in TSQM-II scores between groups. Both groups had high scores in all domains, with especially high scores reported in both the convenience and side effects domains (Table 3).

There was no significant difference in the number of withdrawals for worsening eczema between groups. Four (9·8%) participants in the kānuka oil group and four (10·3%) in the vehicle control group. Relative risk (95% CI) 1·0 (0·3 to 3·5), p = 0·94 (Table 4). Likewise, there was no significant difference in the proportion of participants requiring treatment escalation between groups (Table 4). Seven (17·1%) participants in the kānuka oil group required escalated treatment, compared with five (12·8%) in the vehicle control group. Relative risk (95% CI) 1·3 (0·5 to 3·8), p = 0·59 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Safety outcome measures - Data are reported as total number (%) unless otherwise specified.

| Outcome measure | Kānuka oil n = 41 | Vehicle control n = 39 | Relative risk (95% CI) p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawals for worsening eczema | 4 (9·8) | 4 (10·3) | 1·0 (0·3 to 3·5) p = 0·94 |

| Required treatment escalationa | 7 (17·1) | 5 (12·8) | 1·3 (0·5 to 3·8) p = 0·59 |

| Relative rate (95% CI)p-value | |||

| Reported adverse events | 22 | 15 | 1·4 (0·7 to 2·7) p = 0·32 |

| Reported related adverse events | 3 | 2 | 1·4 (0·2 to 8·5) p = 0·70 |

Experienced an adverse event of worsening eczema that resulted in withdrawal from the study or required the use of corticosteroids or antibiotics during the treatment period.

There were no reported serious adverse events in either treatment group. In the kānuka oil group there were 22 reported adverse events (AEs) compared to 15 in the vehicle control group, relative rate (95% CI) 1·4 (0·7 to 2·7) p = 0·32 (Table 4). Three AEs, one instance of transient stinging and two instances of worsening eczema, were defined as related in the kānuka oil group versus two AEs, both worsening of eczema, in the vehicle control group. Relative rate (95% CI) 1·4 (0·2 to 8·5), p = 0·70 (Table 4).

Exploratory analyses compared the remote dermatologist and pharmacist objective scoring of eczema using the intensity component of SCORAD. At baseline, pharmacists scored dryness, leathery, oozing, and scratched higher than the dermatologist. At week six, pharmacists scored dryness, leathery, oozing, and swelling higher than the dermatologist. There were statistically significant differences between the remote dermatologist and pharmacist for dryness, leathery, and oozing at both timepoints (Table 5).

Table 5.

Scorad interrater variability.

| Pharmacist versus Dermatologista Odds ratio of higher score (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Baseline | p-value | Week Six | p-value |

| Dryness | 22·3 (8·8 to 56·7) | <0·001 | 3·3 (1·6 to 6·6) | 0·001 |

| Leathery | 1·7 (0·9 to 3·2) | 0·08 | 0·5 (0·3 to 1·0) | 0·046 |

| Oozing | 3·1 (1·5 to 6·5) | 0·003 | 0·2 (0·1 to 0·7) | 0·006 |

| Redness | 1·0 (0·5 to 2·0) | 0·99 | 0·7 (0·3 to 1·8) | 0·49 |

| Scratched | 3·9 (2·0 to 7·5) | 0·001 | 1·5 (0·7 to 2·9) | 0·26 |

| Swelling | 0·6 (0·3 to 1·1) | 0·10 | 0·2 (0·1 to 0·5) | 0·001 |

SCORAD = Scoring Atopic Dermatitis.

Dermatologist scoring was conducted on a photo of the representative lesion. Photos were taken by the pharmacist immediatley after they scored the representative lesion.

Discussion

This randomised controlled trial of adults with self-reported moderate to severe eczema, found the use of a kānuka oil cream to be a safe and effective emollient therapy. Both creams were well tolerated by participants, with low rates of adverse events and withdrawals, and positive global acceptability ratings.

The primary outcome was statistically significant between treatment groups at Week Six (Table 2), with the kānuka oil group improving to a greater degree than the control group, although the point estimate of the difference in POEM score between the groups was smaller than the prespecified MCID of 3·4.35 There was also a statistically significant difference in the number of ‘responder’ participants that improved by four or more points in their POEM score over the study period (Table 3). More participants experienced a clinically significant improvement of their POEM score in the kānuka oil group compared to the control group. Furthermore, the kānuka oil group had a mean improvement in POEM score of 11·6 points, representing a mean change from the severe to mild category (not shown), and the vehicle control group had a mean improvement of 8·9 points, a mean change from the severe to moderate category (not shown).

Improvement in both groups for the different efficacy and quality of life measures can be explained by the emollient and moisturising effects of the base cream present in both randomised treatments and points to the benefit of regular emollient treatment. However, the statistically significant improvement seen in the primary outcome, number of ‘responders’, and the difference in mean category improvement, provides evidence for a therapeutic benefit of kānuka oil when added to an emollient cream.

While not powered to detect a difference in the secondary outcomes, it should be noted that there was no statistically significant difference between the groups for the PO-SCORAD and DLQI which assess symptom severity and quality of life respectively (Table 3). This may suggest that the effect of the kānuka oil was limited to reducing the frequency of symptoms and not their overall severity. It also suggests that the effect may not have a significant impact on quality of life.

The exploratory outcome assessing interrater variability of the SCORAD intensity section between the in-person pharmacists and a remote dermatologist suggested assessor disagreement (Table 5). Pharmacist investigators consistently gave the eczema lesions a more severe score across every domain assessed. This disagreement may be influenced by the patient population typically seen by dermatologists. These patients are often experiencing severe eczema symptoms and consistent exposure to severe symptoms may skew the dermatologist's perception of the wider symptom spectrum, resulting in an underestimation of severity in the general public. The limitations of scoring from a photograph may have also contributed to the disagreement. Remote assessments do not have the benefit of being able to feel the skin to assess dryness and are unable to take other areas of the skin into context for comparison with the affected area.

Despite the disagreement between assessors, the tele-dermatology process resulted in good quality and acceptable photos. The study dermatologist rated each photograph for acceptability with a median score of 7 on a 10-point scale (not shown). However, there were key areas to be improved including consistent and correct lighting along with reducing blurring.

The symptom frequency (POEM) and treatment satisfaction (TSQM vII) scores reported in our study (Tables 2 & 3) are consistent with a recent observational study by Wei at al assessing currently prescribed systemic eczema treatments.45 In their study, the mean POEM score reported was 10·3, indicating that participants in our study experienced a similar level of symptom frequency at Week Six to those using existing systemic therapies. Additionally, both the kānuka oil and vehicle control groups reported higher treatment satisfaction scores across all TSQM vII domains compared to the reported values by Wei et al. This difference in acceptability scores may have been due to the fact that participants in Wei et al had been using their existing treatment for some time while participants in our study were using a treatment that was novel to them.

Participants in an observational study by Oosterhaven et al, investigating the efficacy of biologic treatment dupilimab, reported similar symptom frequency (POEM) and quality of life (DLQI) scores to those reported in our study (Tables 2 & 3).46 Participants in their study had a baseline mean (SD) POEM of 19·0 (6·6) and an on treatment mean (SD) POEM of 8·5 (5·8). For the DLQI, the mean (SD) baseline was 12·9 (6·9) and mean (SD) on treatment score was 4·1 (4·0). Participants in our study mirrored these results, demonstrating a similar improvement in quality of life and symptom control to those taking dupilimab. Comparison with these studies lends further support to the potential use of kānuka oil cream as an acceptable and convenient daily barrier treatment for eczema.

No difference between treatment groups was observed in the per protocol analysis (Table 2). However, the restrictive, pre-specified per protocol criteria may have selected towards those experiencing a clinical benefit. Future studies should use minimum thresholds for adherence, concomitant medication, and data collection versus absolute criteria. This should help to ensure external validity for the community-based study outcomes.

There were four participants who met the criteria for treatment escalation and did not withdraw from the study (not shown). Treatment escalation was measured by an adverse event of worsening eczema leading to withdrawal from the study, or use of corticosteroids or antibiotics during the treatment period. Three of these participants were in the active group, of which two required use of a corticosteroid cream while the third required antibiotics. The participant in the control group required a corticosteroid cream. Use of these medications may have impacted their final POEM score and resulted in bias of the primary outcome. However, the need for treatment escalation was included in the ITT analysis of the primary outcome as a categorical covariate to account for this. It could be argued that the primary outcome would have better analysed by a simple t-test for the reason that an explanatory factor derived from post-randomisation information was used in the model. However, ANCOVA can be considered an appropriate analytic method, as although the treatment escalation happened after the randomisation it occurred before the final measurement time, so the treatment escalation is on the causal path to the final measurement. This approach is also consistent with the intention to treat approach. In this event, both the magnitude of the difference and level of statistical significance were similar with the two statistical methods, -3.1 (-6.0 to -0.2), p = 0.036 (Table 2) for ANCOVA and -3.0 (-5.9 to -0.1), p = 0.044 (not shown) for the simple t-test.

There was a small amount of missing outcome data which has the potential to bias the estimate of treatment difference. However, the proportions of participants with missing data was small and although unable to be formally compared, the baseline characteristics of those with missing data seemed similar to those without missing data, and not different between treatment arms.

The MRINZ and pharmacist investigators were blinded to the allocation of treatment, but there was a risk of participants being unblinded due to the strong odour conferred by the addition of kānuka oil to the cream. This may have led to bias when reporting subjective scores both in the active and vehicle control groups. Future research should endeavour to match the smell of kānuka oil with the control. However, this may be difficult due to the strong distinctive nature of the smell.

Like many others, our study was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic which resulted in lost outcome data due to necessitated remote follow up visits; fortunately, missing data only impacted the SCORAD outcomes, and the primary outcome was unaffected. The study team were concerned that the increase in hand washing and sanitiser use during the pandemic may have also had an impact on participants eczema symptoms but an ad hoc analysis performed did not find any significant differences between those recruited prior to the start of the pandemic and those recruited during the pandemic (not shown).

The outcome measures used will allow for robust comparison of these results with current and future interventional eczema trials. The POEM and DQLI are recommended by the Harmonising Outcome Measure for Eczema Initiative (HOME) as the preferred outcome variables for clinical trials reporting self-reported symptoms of eczema and quality of life, respectively.47,48 Whilst HOME recommends the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) for objective symptoms, this measure requires a complex full body assessment of disease and as such was not pragmatic for the community pharmacy setting.49 We instead used the intensity component of the Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), a widely used and validated objective outcome measure, that allowed pharmacists to score a single representative lesion, with remote corroboration by the dermatologist investigator.42 This was supported by the Patient Orientated Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD), a validated outcome measure that allows participant reported assessment of a specific lesion.40,50 Acceptability was scored by the TSQM Version II, a treatment acceptability measure validated in a pharmacy outpatient consumer population and a refinement of the original TSQM.41,51

The decentralised nature of this study allowed for a more robust and generalisable study population. Indigenous peoples are typically under-represented in clinical research.52 Reasons for this are multi-factorial, with a major driver being a ‘jurisdiction effect’ whereby the traditional studies conducted at major centres actively select against the recruitment of a representative, national population.53 In this study 25% of the participants self-identified as Māori, the indigenous peoples of NZ, higher than both the most recent census estimate of 16·5% and previous participation rates seen in other eczema studies in New Zealand.54,55 This is in part due to the decentralised nature of the study, providing nationwide enrolment through community pharmacy, an embedded healthcare setting that is accessible, trusted, and non-appointment based.56,57 Other contributing factors may include the higher prevalence of eczema in Māori, provision of bi-lingual study materials, the traditional medicine base of the active study intervention, and the strong social impact of the local industry producing the treatment.20 Through this increased equity in participation, the community pharmacy research infrastructure provides a representative study population that provides strong external validity, particularly important to consumer choice for products that are able to be marketed with no clinical data.58

A further strength of this design was the use of direct electronic data capture for consent, study data, and stock logging along with electronic study documentation and remote monitoring. This allowed for agile and resource efficient implementation of study amendments, as necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring minimal downtime in recruitment and minimised data loss.

In summary, this study recruiting a generalisable sample supports the use of a kānuka oil cream as an emollient therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe eczema in adults.

Contributors

The study was designed by N.S., A.S., K.K., M.W., and M.R. Data was collected by N.S., A.S., A.M., A.L., M.R., I.V., L.B., J.S., and the Pharmacy Research Network. N.S. and A.S. had access to all data. Statistical analysis was completed by M.W. and A.E. The paper was drafted by N.S. and A.S. with revision and final approval by all authors.

The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Data sharing statement

Inquiries about access to the original clinical data should be directed to the Corresponding Author.

Declaration of interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form. R.B., A.S., and N.S. declare funding from Hikuangi Bioactives and Honeylab to the MRINZ for the submitted work. All other authors declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Hikurangi Bioactives (Ruatoria, New Zealand) and HoneyLab (Tauranga, New Zealand), supported by a grant from Callaghan Innovation. We thank the pharmacy research network investigators for their involvement in the conduct of the study and collection of the data. We also thank the participants who took part in this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101561.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Kantor R, Thyssen JP, Paller AS, Silverberg JI. Atopic dermatitis, atopic eczema, or eczema? A systematic review, meta-analysis, and recommendation for uniform use of ‘atopic dermatitis. Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;71(7):1480–1485. doi: 10.1111/all.12982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitt J, Langan S, Stamm T, Williams HC, on behalf of the Harmonizing Outcome Measurements in Eczema (HOME) Delphi panel Core outcome domains for controlled trials and clinical recordkeeping in eczema: International multiperspective delphi consensus process. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(3):623–630. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmitt J, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, Simpson E, Furue M. The harmonising outcome measures for eczema (HOME) statement to assess clinical signs of atopic eczema in trials. J Allergy Clinic Immunol. 2014;134(4):800–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet North Am Ed. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, Sevetson E, Block JK, Qureshi AA. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(1):26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zink A, Arents B, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for individuals with atopic eczema: a cross-sectional study in nine European countries. Acta Derm Venerol. 2019;99(3):263–267. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weidinger S, Novak N, Kiel C. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet North Am Ed. 2016;387(10023):1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00149-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong M, Fonacier L. Treatment of eczema: corticosteroids and beyond. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(3):249–262. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson EL. Atopic dermatitis: a review of topical treatment options. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(3):633–640. doi: 10.1185/03007990903512156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman SR, Cox LS, Strowd LC, et al. The challenge of managing atopic dermatitis in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2019;12(2):83–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JH, Son SW, Cho SH. A comprehensive review of the treatment of atopic eczema. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016;8(3):181–190. doi: 10.4168/aair.2016.8.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tier HL, Balogh EA, Bashyam AM, et al. Tolerability of and adherence to topical treatments in atopic dermatitis: a narrative review. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(2):415–431. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00500-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aubert-Wastiaux H, Moret L, Le Rhun A, et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a study of its nature, origins and frequency. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(4):808–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.See A, Teo B, Kwan R, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among dermatology outpatients in Singapore. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52(1):7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu C, Liu X, Stub T, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine for treatment of atopic eczema in children under 14 years old: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):260. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2306-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holm JG, Clausen M-L, Agner T, Thomsen SF. Use of complementary and alternative therapies in outpatients with atopic dermatitis from a dermatological university department. Dermatology. 2019;235(3):189–195. doi: 10.1159/000496274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koo K, Nagayah R, Begum S, Tuan Mahmood TM, Mohamed Shah N. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in children with atopic eczema at a tertiary care centre in Malaysia. Complement Ther Med. 2020;49 doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frass M, Strassl RP, Friehs H, Müllner M, Kundi M, Kaye AD. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner J. 2012;12(1):45–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, Robertson CF, Asher MI. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6) doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009. 1251–1258.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clayton T, Asher MI, Crane J, et al. Time trends, ethnicity and risk factors for eczema in New Zealand children: ISAAC Phase Three. Asia Pacific Allergy. 2013;3(3):161–178. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2013.3.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Essien SO, Baroutian S, Dell K, Young B. Value-added potential of New Zealand mānuka and kānuka products: a review. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;130:198–207. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koea J, Mark G. Is there a role for Rongoā Māori in public hospitals? The results of a hospital staff survey. N Z Med J. 2020;133(1513):8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM, York N. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population – based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1132–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Essien SO, Young B, Baroutian S. The antibacterial and antiproliferative ability of kānuka, Kunzea ericoides, leaf extracts obtained by subcritical water extraction. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2021;96(5):1308–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perry NB, Brennan NJ, Van Klink JW, et al. Essential oils from New Zealand manuka and kanuka: chemotaxonomy of Leptospermum. Phytochemistry. 1997;44(8):1485–1494. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter NG, Wilkins AL. Chemical, physical and antimicrobial properties of essential oils of Leptospermum scoparium and Kunzea ericoides. Phytochemistry. 1998;50(3):407–415. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(98)00548-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Vuuren SF, Docrat Y, Kamatou GPP, Viljoen AM. Essential oil composition and antimicrobial interactions of understudied tea tree species. S Afr J Bot. 2014;92:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CC, Yan SH, Yen MY, et al. Investigations of kanuka and manuka essential oils for in vitro treatment of disease and cellular inflammation caused by infectious microorganisms. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;49(1):104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lis-Balchin M, Hart SL, Deans SG. Pharmacological and antimicrobial studies on different tea-tree oils (Melaleuca alternifolia, Leptospermum scoparium or Manuka and Kunzea ericoides or Kanuka), originating in Australia and New Zealand. Phytother Res. 2000;14(8):623–629. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200012)14:8<623::aid-ptr763>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HS, Park H-W, Song W-J, et al. TNF-α enhance Th2 and Th17 immune responses regulating by IL23 during sensitization in asthma model. Cytokine. 2016;79:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mark G. Whakauae Research Services; Whanganui: 2014. Huarahi Rongoā Ki A Ngai Tātou: Māori Views on Rongoā and Primary Health. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spuls PI, Gerbens LAA, Simpson E, et al. Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), a core instrument to measure symptoms in clinical trials: a Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(4):979–984. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leshem YA, Chalmers JR, Apfelbacher C, et al. Measuring atopic eczema symptoms in clinical practice: the first consensus statement from the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema in clinical practice initiative. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):1181–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schram ME, Spuls PI, Leeflang MMG, Lindeboom R, Bos JD, Schmitt J. EASI, (objective) SCORAD and POEM for atopic eczema: responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2012;67(9):99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)-a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ali FM, Johns N, Finlay AY, Salek MS, Piguet V. Comparison of the paper-based and electronic versions of the Dermatology Life Quality Index: evidence of equivalence. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):1306–1315. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basra MKA, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994-2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(5):997–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basra MKA, Salek MS, Camilleri L, Sturkey R, Finlay AY. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the dermatology life quality index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27–33. doi: 10.1159/000365390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stalder JF, Barbarot S, Wollenberg A, et al. Patient-Oriented SCORAD (PO-SCORAD): a new self-assessment scale in atopic dermatitis validated in Europe. Allergy. 2011;66(8):1114–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atkinson MJ, Kumar R, Cappelleri JC, Mass SL. Hierarchical construct validity of the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM Version II) among outpatient pharmacy consumers. Value Health. 2005;8(suppl 1):S9–S24. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schallreuter KU, Levenig C, Berger J, et al. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD Index. DRM. 1993;186(1):23–31. doi: 10.1159/000247298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Semprini A, Singer J, Braithwaite I, et al. Kanuka honey versus aciclovir for the topical treatment of herpes simplex labialis: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Semprini A, Braithwaite I, Corin A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of topical kanuka honey for the treatment of acne. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei W, Ghorayeb E, Andria M, et al. A real-world study evaluating adeQUacy of Existing Systemic Treatments for patients with moderate-to-severe Atopic Dermatitis (QUEST-AD) Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(4) doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.07.008. 381–388.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oosterhaven JAF, Spekhorst LS, Zhang J, et al. Eczema control and treatment satisfaction in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab – a cross-sectional study from the BioDay registry. J Dermatol Treatm. 2022;33(4):1986–1989. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2021.1937485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spuls PI, Gerbens L a.A, Simpson E, et al. Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), a core instrument to measure symptoms in clinical trials: a Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(4):979–984. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmitt J, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, et al. The Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement to assess clinical signs of atopic eczema in trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;10(1):800–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanifin J, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte S, Graeber M. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2001;(8):11–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vourc'h-Jourdain M, Barbarot S, Taieb A, et al. Patient-oriented SCORAD: a self-assessment score in atopic dermatitis - a preliminary feasibility study. Dermatology. 2009;218(3):246–251. doi: 10.1159/000193997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, et al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glover M, Kira A, Johnston V, et al. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to participation in randomized controlled trials by Indigenous people from New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the United States. Glob Health Promot. 2015;22(1):21–31. doi: 10.1177/1757975914528961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gheorghe A, Roberts T, Hemming K, Calvert M. Evaluating the generalisability of trial results: introducing a centre- and trial-level generalisability index. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(11):1195–1214. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Māori population estimates: At 30 June 2020 | Stats NZ [cited 2021 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/maori-population-estimates-at-30-june-2020.

- 55.Wickens K, Black PN, Stanley TV, et al. A differential effect of 2 probiotics in the prevention of eczema and atopy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(4):788–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horsfield E, Sheridan J, Kelly F, Robinson E, Clark T, Ameratunga S. Filling the gaps: opportunities for community pharmacies to help increase healthcare access for young people in New Zealand. Int J Pharmacy Pract. 2014;22(3):169–177. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bajorek BV, LeMay KS, Magin PJ, Roberts C, Krass I, Armour CL. Management of hypertension in an Australian community pharmacy setting – patients’ beliefs and perspectives. Int J Pharmacy Pract. 2017;25(4):263–273. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rothwell PM. Factors that can affect the external validity of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1(1):e9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.