Abstract

There is no validated framework to evaluate health information technology (HIT) for diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES). AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors is a patient-centered DSMES designed by the American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE). We developed a codebook based on the AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors principles as an evaluation framework. In this commentary, we demonstrate the real-life applications of this codebook through three diabetes research studies. The first study analyzed features of mobile diabetes applications. The second study evaluated provider documentation patterns in electronic health records (EHRs) to deliver ongoing patient-centered DSMES. The third study analyzed feedback messages from diabetes apps. We found that this codebook, based on AADE7, can be instrumental as a framework for research, as well as real-life use in HIT for DSMES principles.

Keywords: diabetes, evaluation, framework, health information technology, self-management

Diabetes Self-Management Education in Health Information Technology

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic disease with an increasing burden globally. As a chronic disease, it has a significant impact on the person and the community in multiple ways, both health wise and economically. Diabetes self-management education (DSME) is the process of facilitating the knowledge, skill, and ability necessary for diabetes self-care. Diabetes self-management support (DSMS) refers to the support that is required for implementing and sustaining coping skills and behaviors needed to self-manage on an ongoing basis. 1 Consequently, diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) helps to maintain the desired self-care behavior change.2-4 It can lead to improvement in clinical control of glycemia5-11 and health outcomes such as quality of life.12-14 AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors, 15 first compiled in 1997, play a central role in delivering patient-centered DSMES to people with DM for more than 20 years. The framework helps providers deliver the key points of DSMES in an organized manner to people with DM. The AADE7 principles are widely adopted in clinical care as well as in the development of protocols and programs focused on DSMES. Revisions and updates to these principles allowed for adaptation to technological advances. 16 Many research studies17,18 in diabetes utilized the seven principles. However, few research studies have investigated the application of AADE7 in the area of health information technology (HIT). We want to take this commentary as an opportunity to share our three applied research studies, where we employed AADE7 as an evaluation framework for HIT for DM.

Framework for Codebook Development

At the University of Missouri Health Care, we formed an interdisciplinary team with diverse expertise of several distinct but related disciplines—informatics (Kim, Narindrarangkura, Ye), endocrinology (Khan), diabetes education (Boren), and implementation science (Simoes). The principal goal of our research team is to enhance use of electronic health records (EHRs) in self-care behaviors of people with DM. Our aim was to develop a mechanism to allow the clinically relevant evidence-based AADE7 principles to apply objectively in a research setting. Over a period of five years, the team took a stepwise approach to develop and apply a framework based on AADE7 principles to health information data.

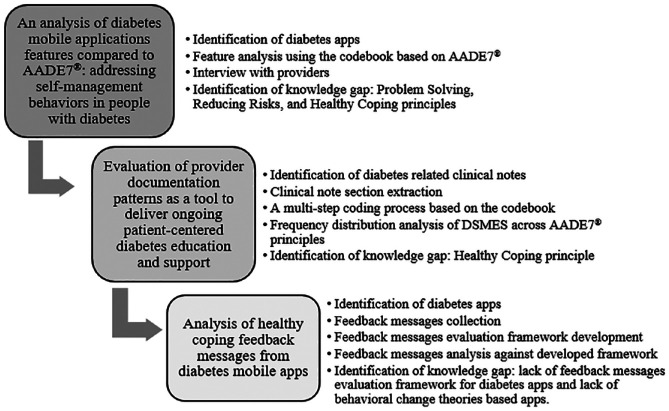

The research team developed and updated the framework by consulting the AADE7 guidelines for the most up-to-date education items. Each principle was systematically broken down into specific statements, and a code assigned to each statement. Through an iterative process, a code book was created with designated columns for “Category,” “ID,” “Statement,” and “Count” each statement (Table 1). Once we created the codebook, we explored its use in real-life research setting by applying to three research studies focusing on HIT in DMES. The results of each study allowed for a detailed review of the codebook in a stepwise fashion. We conducted revisions to the framework at each step. The sequential studies led to the current version that captures consistent and comprehensive DSMES items for application (Figure 1).

Table 1.

AADE7-Based Codebook Used for Evaluating Diabetes-Related Health Information Technology.

| Category | ID | Code | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Healthy Eating | 1.1 | Develop an eating plan (how to plan a week of eating overall or how to plan each meal) | |

| 1.2 | Set goals for healthy eating | ||

| 1.3 | Remind to eat | ||

| 1.4 | Provide Recipes | ||

| 1.5 | Count carbohydrates | ||

| 1.6 | Read food labels | ||

| 1.7 | Prevent high or low blood sugar | ||

| 1.8 | Measure each serving (know how much you should eat and don’t overdo it) | ||

| 1.9 | Monitor eating (record what you eat and how much you eat) | ||

| 1.10 | Provide knowledge of healthy eating | ||

| 1.11 | Provide restaurants information | ||

| 1.12 | Share record of eating through forum or email | ||

| 2. Being Active | 2.1 | Set exercise plan/goal | |

| 2.2 | Remind to do exercise | ||

| 2.3 | Choose activities (think of things you like to do) | ||

| 2.4 | Start exercising (take it slow – start with five or 10 minutes of the activity and work your way up to 30 minutes at a time, five days a week) | ||

| 2.5 | Do exercise at personal pace (don’t overdo it! While you exercise, you should be able to talk, but not sing) | ||

| 2.6 | Check blood sugar level before and after exercise | ||

| 2.7 | Keep track of activities | ||

| 2.8 | Find a friend to exercise with | ||

| 2.9 | Take a physical exercise class | ||

| 2.10 | Join adult leagues | ||

| 2.11 | Mix activities up (try a few different things so you don’t get bored) | ||

| 2.12 | Provide knowledge of exercise | ||

| 2.13 | Share record of exercise through forum or email | ||

| 3. Monitoring | 3.1 | Learn how to use the glucometer | |

| 3.2 | Learn tips for the best/easiest way to monitor | ||

| 3.3 | Learn when to check the blood sugar | ||

| 3.4 | Learn what the results of blood sugar mean | ||

| 3.5 | Learn what to do if the results of blood sugar are off target | ||

| 3.6 | Learn how to record blood sugar results and keep track over time | ||

| 3.7 | Set goals for blood sugar | ||

| 3.8 | Monitor blood sugar levels | ||

| 3.9 | Record the spot of blood sugar testing or insulin injection | ||

| 3.10 | Provide knowledge of blood sugar | ||

| 3.11 | Monitor lab test results (other than blood sugar, cholesterol, and urine testing) | ||

| 3.12 | Monitor vital signs (other than blood pressure and pulse) | ||

| 3.13 | Monitor heart health (blood pressure, pulse, weight, BMI, and cholesterol level) | ||

| 3.14 | Monitor kidney health (urine and blood testing) | ||

| 3.15 | Monitor eye health (eye exams) | ||

| 3.16 | Monitor foot health (foot exams and sensory testing) | ||

| 3.17 | Share record of blood sugar through forum or email | ||

| 4. Taking Medication | 4.1 | Learn why take these medications | |

| 4.2 | Learn what will these medications do for patients | ||

| 4.3 | Learn how to fit medications into the schedule | ||

| 4.4 | Learn the side effects of these medications | ||

| 4.5 | Learn what to do for side effects of medications | ||

| 4.6 | Remember to take medications at the right time every day | ||

| 4.7 | Remind to take medication | ||

| 4.8 | Manage medication list | ||

| 4.9 | Calculate recommended insulin dosage | ||

| 4.10 | Rotate the sites if inject insulin (if the patient injects insulin, rotate the sites every day from the fattier part of the patient’s upper arm to outer thighs to buttocks to abdomen) | ||

| 4.11 | Record medicine adherence | ||

| 4.12 | Provide knowledge of medication | ||

| 4.13 | Share record of medication through forum or email | ||

| 5. Problem Solving | 5.1 | Don’t beat self up (managing diabetes doesn’t mean being “perfect.”) | |

| 5.2 | Analyze the day | ||

| 5.3 | Learn from experience (Figure out how to correct the problem in a way that works best for the patient, and apply that to similar situations moving forward) | ||

| 5.4 | Discuss possible solutions | ||

| 5.5 | Try the new solutions (try the new solutions and then evaluate whether they are working for the patient) | ||

| 5.6 | Use an alert or reminder for abnormal data | ||

| 6. Reducing Risks | 6.1 | Don’t smoke | |

| 6.2 | See the doctor regularly (plan to see the doctor about every three months, unless told otherwise) | ||

| 6.3 | Visit the eye doctor at least once a year | ||

| 6.4 | See the dentist every six months | ||

| 6.5 | Take care of the feet | ||

| 6.6 | Listen to the body (if the patient doesn’t feel well, or something just doesn’t seem right, contact the doctor to help figure out what’s wrong, and what the patient should do about it) | ||

| 6.7 | Provide knowledge of reducing risks | ||

| 6.8 | Share information with a diabetes forum or American Diabetes Association website, etc., with the patient | ||

| 6.9 | Vaccination | ||

| 7. Healthy Coping | 7.1 | Do exercise (when the patient is sad or worried about something, suggest going for a walk or bike ride. Research shows when people are active, the brain releases chemicals that make them feel better) | |

| 7.2 | Participate in faith-based activities or meditation | ||

| 7.3 | Pursue hobbies | ||

| 7.4 | Attend support groups | ||

| 7.5 | Thinking positive | ||

| 7.6 | Being good to self | ||

| 7.7 | Record mood | ||

| 7.8 | Share knowledge of healthy coping |

Abbreviation: BMI: body mass index.

Figure 1.

The codebook development and its applications.

These studies focused on creating and validating the codebook for use in a rigorous research setting. Based on our experience, we found the codebook was easy to use objectively, with excellent interoperator validity. This makes it useful not only in HIT-related research but also in real-world scenarios using digital technology in healthcare outcomes. New developments in EHR, including the use of clinical care pathways and patient portals, are areas where this codebook can be incorporated into programs for evaluating outcomes. We invite the utilization of the codebook for applying the AADE7 principles to improve clinical outcomes for people with DM.

Study 1: Application of the Codebook for Analysis of Features of Diabetes Mobile Application (Mobile Apps)

DSMES is a daily task and requires support between office visits on an ongoing basis. People with diabetes can benefit from using diabetes apps, and mobile apps are increasingly used in this area. However, few studies have evaluated the features of diabetes apps against evidence-based guidelines.

In the first study, 19 we systematically examined the content and functionality of current diabetes apps by utilizing a multi-step review process of two online stores with major market share (iTunes and Google Play). We analyzed and classified the features of each app according to the codebook developed by the team based on the AADE7 (Table 1). By applying the codebook, we confirmed a skewed app development trend in 179 eligible apps out of 750 apps searched. The majority of the apps were designed to support the principles of Healthy Eating (70%), Monitoring (70%), Taking Medication (51%), and Being Active (36%), all of which require quantitative information. On the other hand, few apps supported principles of Problem Solving (20%), Healthy Coping (9%), and Reducing Risks (4%), all of which need qualitative input to provide management guidance based on more patient-entered data.

Study 2: Using the Codebook to Evaluate Provider Documentation Patterns in EHR Regarding Patient-Centered DSMES for Long-Term Management

For people with diabetes to achieve the clinical and health benefits of DSMES, patients and providers must make decisions about DSMES together. The long-term management should be patient-centered and take into consideration comorbid conditions and social factors.

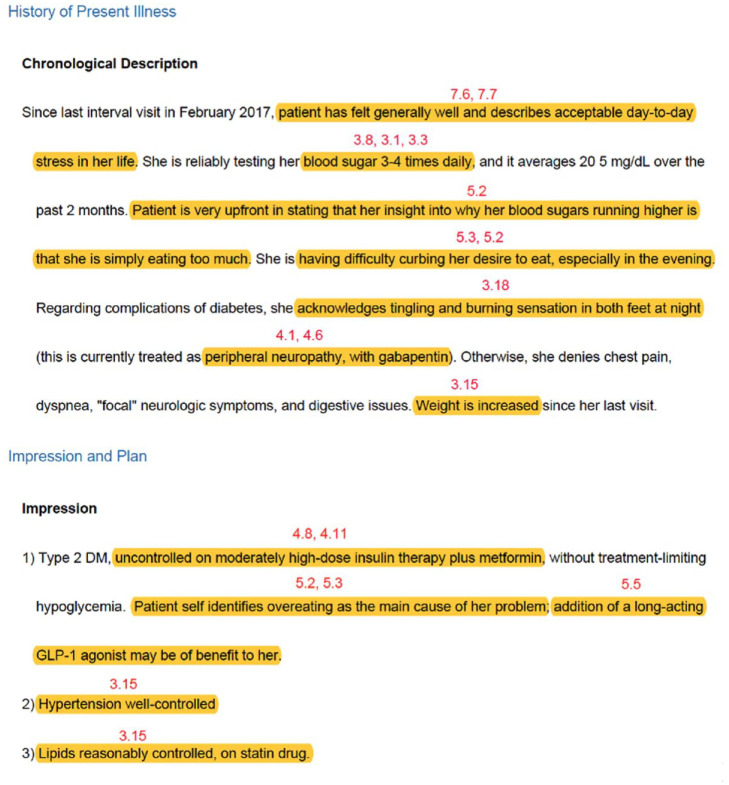

In the second study,20,21 we investigated whether providers delivered DSMES to adults with DM based on patient characteristics. We analyzed clinic notes of adults with diabetes that are stored in EHR. We compared DSMES items in clinic notes against the codebook based on AADE7 principles. We analyzed 200 clinic notes randomly selected from 2634 notes of adults with diabetes. Two specific sections “History of Present Illness (HPI)” and “Impression and Plan (I&P)” were deemed to be specific for provider-delivered DSMES and not resulting from auto population based on the computer program. A thematic analysis of these specific segments using the codebook revealed 3735 codes related to DSMES in the 200 notes (Figure 2). Monitoring (48%) was addressed most frequently, and Healthy Coping (2%) was addressed least frequently regardless of patient characteristics, including age, comorbidities, body mass index (BMI), and HbA1c. The study was limited to one center so findings cannot be generalized. Current studies do show that providers focus on clinical decision-making regarding drugs choices, rather than DSMES.22,23 We believe this information is thought-provoking and may indicate that in a busy clinic, it is a challenge for providers to deliver patient-centered DSMES effectively during the limited visit time.24-27 Consequently, the visit time may be fragmented and insufficient for providers to educate patients on individual DSMES topics. Further studies are needed to assess the clinic notes as an educational tool. The 21st Century Cures Act provides access to clinic notes for all patients. 28 This is also an opportunity to develop HIT protocol focusing on DSMES incorporated into clinic notes and provide an additional educational tool for patients.

Figure 2.

An example of clinical note analysis against the codebook.

Study 3: Analysis of Feedback Messages From Diabetes Mobile Apps Using the Codebook

Behavioral change theory-based feedback messages delivered in diabetes apps can be an effective way to provide DSMES to people with diabetes. Based on our experience as described in the previous two studies, we found that Healthy Coping, an important principle in DSMES, was underutilized. We evaluated the codebook to answer a targeted question to address Healthy Coping in mobile app messages.

In the third study,29,30 we focused on Healthy Coping-related feedback messages from diabetes mobile apps against the theoretical framework based on behavioral change theories. We used a framework by adopting validated behavioral change theory-based models and analyzed the feedback messages against three dimensions of timing, intention, and content (feedback response and feedback purpose). The feedback purposes were further categorized into seven purposes: warning, suggestion, self-monitoring, acknowledging, reinforcement, goal setting, and behavior contract. We identified 1749 apps from iTunes and Google Play stores, and found 156 eligible apps that generated a total of 473 feedback messages. The majority of feedback messages generated were about blood glucose under the diabetes-related measures domain (219, 46.3%), followed by messages about the mood domain (128, 27.0%). Only feedback messages on blood glucose under diabetes-related measures and mood domains encompassed all seven feedback purposes under the content dimension. Overall, few feedback messages generated supported the purposes of warning (39, 8.3%), suggestion (38, 8.0%), goal setting (36, 7.6%), behavioral contract (10, 2.1%), and reinforcement (8, 1.7%) across the three Healthy Coping domains.

Conclusion

We found that our codebook based on AADE7 could be instrumental in applying DSMES principles for the purposes of health data research and real-world management of people with diabetes. With the increasing prevalence of DM, and broader adoption of EHR by providers and patients, there is a need for evaluation DSMES in people with diabetes in both the research and clinical setting. Tools that allow for objective assessment in a variety of clinical settings may have a significant impact on patient-centered care in people with DM. We present this codebook based on AADE7 principles as a tool for HIT clinical research and incorporation into mobile applications and EHR-based clinical care pathways. We invite feedback from the healthcare provider community to extend the use of the validated AADE7 principles in a broad area of clinical application.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AADE7, American Association of Diabetes Educators; DM, diabetes mellitus; DSMES, diabetes self-management education and support; EHR; electronic health records; HIT, health information technology.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders (NIDDK) P30DK092950 from Center for Diabetes Translation Research (CDTR) Pilot & Feasibility (P&F) program grant and University of Missouri Research Council grant URC-19-153 were available when this project was conducted.

ORCID iD: Ploypun Narindrarangkura  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5737-2559

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5737-2559

References

- 1. Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, et al. Diabetes self-management education and support in type 2 diabetes: a joint position statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Clin Diabetes Publ Am Diabetes Assoc. 2016;34(2):70-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1159-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beverly EA, Fitzgerald S, Sitnikov L, Ganda OP, Caballero AE, Weinger K. Do older adults aged 60-75 years benefit from diabetes behavioral interventions? Diabetes Care. 2013;36(6):1501-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen L, Pei J-H, Kuang J, et al. Effect of lifestyle intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2015;64(2):338-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones H, Edwards L, Vallis TM. Changes in diabetes self-care behaviors make a difference in glycemic control: the Diabetes Stages of Change (DiSC) study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):732-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fan L, Sidani S. Effectiveness of diabetes self-management education intervention elements: a meta-analysis. Can J Diabetes. 2009;33(1):18-26. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wysocki T. Impact of blood glucose monitoring on diabetic control: obstacles and interventions. J Behav Med. 1989;12(2):183-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Halimi S. Benefits of blood glucose self-monitoring in the management of insulin-dependent (IDDM) and non-insulin-dependent diabetes (NIDDM). Analysis of the literature: mixed results. Diabetes Metab. 1998;3:35-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allemann S, Houriet C, Diem P. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in non-insulin treated patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(12):2903-2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malanda UL, Bot SD, Nijpels G. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in noninsulin-using type 2 diabetic patients: it is time to face the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(1):176-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McAndrew LM, Napolitano MA, Pogach LM. The impact of self-monitoring of blood glucose on a behavioral weight loss intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39(3):397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lau CY, Qureshi AK, Scott SG. Association between glycaemic control and quality of life in diabetes mellitus. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50(3):189-93,94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Testa MA, Simonson DC. Health economic benefits and quality of life during improved glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. JAMA. 1998;4;280(17):1490-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhu Y, Fish AF, Li F. Psychosocial factors not metabolic control impact the quality of life among patients with type 2 diabetes in China. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53(4):535-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE). AADE7 self-care behaviors. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(3):445-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE). An effective model of diabetes care and education: revising the AADE7 self-care behaviors ®. Diabetes Educ. 2020;46(2):139-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Breland JY, Yeh VM, Yu J. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines among diabetes self-management apps. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(3):277-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chomutare T, Fernandez-Luque L, Arsand E, Hartvigsen G. Features of mobile diabetes applications: review of the literature and analysis of current applications compared against evidence-based guidelines. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ye Q, Khan U, Boren SA, Simoes EJ, Kim MS. An analysis of diabetes mobile applications features compared to AADE7TM: addressing self-management behaviors in people with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(4):808-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ye Q, Boren S, Khan U, Kim MS. Evaluation of provider documentation patterns as a tool to deliver ongoing patient-centered diabetes education and support. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;74(3):e13451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ye Q, Khan U, Boren S, MS. Do people with diabetes receive balanced diabetes self-management education? An analysis of clinic notes against AADE7TM principles. Paper Presented at: AMIA 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Branda ME, LeBlanc A, Shah ND. Shared decision making for patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(301). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vivian E. PharmD. Shared decision-making in patients with type 2 diabetes. Consultant. 2016;56(5):417-423. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the patient–physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(S1):34-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Radecki SE, Kane RL, Solomon DH, Mendenhall RC, Beck JC. Do physicians spend less time with older patients? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36(8):713-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gottschalk A, Flocke SA. Time spent in face-to-face patient care and work outside the examination room. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):488-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Corbett J. 6 Questions Your Doctor Should Be Asking You; 2018. https://www.everydayhealth.com/columns/health-answers/questions-your-doctor-should-be-asking-you/.

- 28. Medscape. Patients Can Read Your Clinical Notes Starting Nov 2. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/939499. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- 29. Ye Q, Boren SA, Khan U, Simoes EJ, Kim MS. Message in an app: a survey of feedback messages about healthy coping in diabetes. Paper Presented at: American Diabetes Association’s 80th Scientific Sessions 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Narindrarangkura P, Ye Q, Boren SA, Khan U, Simoes EJ, Kim MS. Analysis of healthy coping feedback messages from diabetes mobile apps. In Preparation. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]