Abstract

Background:

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) is a common diabetes treatment modality. Glycemic outcomes of patients using CSII in the first 24 hours of hospitalization have not been well studied. This timeframe is of particular importance because insulin pump settings are programmed to achieve tight outpatient glycemic targets which could result in hypoglycemia when patients are hospitalized.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort study evaluated 216 hospitalized adult patients using CSII and 216 age-matched controls treated with multiple daily injections (MDI) of insulin. Patients using CSII did not make changes to pump settings in the first 24 hours of admission. Blood glucose (BG) values within the first 24 hours of admission were collected. The primary outcome was frequency of hypoglycemia (BG < 70 mg/dL). Secondary outcomes were frequency of severe hypoglycemia (BG < 40 mg/dL) and hyperglycemia (BG ≥ 180 mg/dL).

Results:

There were significantly fewer events of hypoglycemia [incident rate ratio (IRR) 0.61, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.42–0.88, p = 0.007] and hyperglycemia (IRR 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.96, p = 0.02) in the CSII group compared to the MDI group. There was a trend toward fewer events of severe hypoglycemia in the CSII group (IRR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02–0.93, p = 0.06).

Conclusions:

Patients using CSII experienced fewer events of both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in the first 24 hours of hospital admission than those treated with MDI. Our study demonstrates that CSII use is safe and effective for the treatment of diabetes within the first 24 hours of hospital admission.

Keywords: glycemic targets, hospitalization, hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, insulin pump

Introduction

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) via an insulin pump has become a popular alternative to traditional forms of insulin therapy. Insulin pumps closely mimic the secretion of insulin from pancreatic islet cells, and is used to treat patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The rates of infusion can be optimized to the patient’s activity level or health status, resulting in reduced risk of activity-induced hypoglycemia and improved overnight glycemia. 1 Contraindications to use of CSII include impairment of consciousness, critical illness requiring intensive care, psychiatric illness preventing the patient from managing the pump, suicide risk, diabetic ketoacidosis, or lack of adequate pump supplies. 2

The number of people with diabetes has been steadily increasing worldwide, and people with diabetes are hospitalized more frequently than the general population.2,3 As a result, inpatient management of diabetes is increasingly important. Treatment with insulin for hospitalized patients is commonly prescribed as basal-bolus therapy via multiple daily injections (MDI), though the use of CSII for hospitalized patients is becoming more prevalent. 2 Prior studies found similar safety and efficacy of insulin pumps compared to MDI in hospitalized patients.4,5 However, the safety of CSII in hospitalized patients and the frequency of hypoglycemia within the first 24 hours of admission have not been well studied. We therefore conducted this study to evaluate the glycemic outcomes of hospitalized patients who used CSII compared to those who were treated with MDI, specifically focusing on the first 24 hours of hospital admission. We chose this specific period for several reasons. First, at our institution pump settings are rarely adjusted within the first 24 hours of admission; rather, adjustments are suggested, if needed, based on glycemic values from the first 24-48 hours of admission. Second, insulin pumps are typically programmed to achieve tight outpatient glycemic targets below the American Diabetes Association’s recommend inpatient target of 140–180 mg/dL. 6 This increases the potential for hypoglycemia early in the hospitalization. 3 Finally, expert consultation from an endocrinologist or other diabetes specialist is not always available in the first 24 hours of admission. As CSII therapy for hospitalized patients becomes more common, it is essential to evaluate its safety in this vulnerable phase of hospital admission.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients using CSII who were hospitalized at NYU Langone Hospital—Long Island with an age-matched comparison group who were treated with MDI. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

NYU Langone Hospital—Long Island has an institutional sanctioned insulin pump policy, which is in line with The Joint Commission Advanced Inpatient Diabetes Care Certification requirements for safe use of insulin pumps in the hospital 7 and the Diabetes Technology Society’s consensus statement on use of CSII in the hospital. 8 The policy requires all admitted patients who are using insulin pumps to sign an insulin pump agreement and have oversight by an inpatient Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialist (CDCES) and endocrinologist. Additionally, documentation of the following in the medical record is required: the patient’s ability to safely manage his or her insulin pump; an order for insulin pump therapy to continue while hospitalized; basal rates; bolus doses (including correctional doses); frequency at which to change infusion set; date of each infusion set change; date of insertion site change (if not the same as set change date); and location and condition of the insertion site. CSII is only discontinued if any of the following conditions that make the use of CSII unsafe are present: altered mental status, cognitive limitations, critical illness, diabetic ketoacidosis, lack of pump supplies or risk of self-harm.

Patients with diabetes who were admitted to our institution between September 2016 and June 2018 and used CSII were evaluated for this study. We excluded patients under the age of 18, treated with an intravenous insulin infusion, admitted for elective surgeries, or pregnant. To evaluate the safety of continuing outpatient insulin pump settings when hospital admission is required, patients using CSII were excluded if they made any adjustments to the pump settings during the first 24 hours of admission (including temporary rates). For each included patient, we used an age-matched control patient with diabetes who was treated with MDI.

At NYU Langone Hospital—Long Island, hyperglycemia is only treated with insulin with rare exceptions. Patients with diabetes or hyperglycemia admitted to our institution who do not utilize CSII are treated with a hospital-wide weight-based protocol of basal, prandial and correctional insulin. Clinicians are provided guidance via the electronic health record in determining appropriate weight-based insulin doses and are advised against simply continuing outpatient insulin regimens. Endocrinology consultation is not required, but may be requested at the discretion of the primary treatment team.

The medical records of all patients included in the study were reviewed and demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected. The serum and capillary blood glucose (BG) values within the first 24 hours since admission were collected. We collected both glucose sources in order to mimic what is encountered in daily clinical practice, where both serum and capillary glucose values are used to determine the presence of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. For patients admitted multiple times during the study period, each admission was included as a distinct episode.

The primary outcome was events of hypoglycemia (defined as BG < 70 mg/dL) in the first 24 hours of hospitalization. Frequency of severe hypoglycemia (defined as BG < 40 mg/dL) and hyperglycemia (defined as BG ≥ 180 mg/dL) were also evaluated.

Data were summarized by groups using median (interquartile range) values and frequencies (percentage). Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov Smirnov test and visual graphs such as histograms and Q–Q plots were constructed. Demographics and clinical characteristics were compared between groups via the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher’s exact test.

A zero-inflated Poisson regression model was used to analyze the count of hypoglycemia and a negative binomial model was used to analyze the count of hyperglycemia per patient during the first 24 hours of the hospitalization. Deviance statistic (Pearson Chi-Square/Degrees of Freedom) and Akaike Information Criterion were used to assess the model fit. The statistical package SAS version 9.4 was used to perform all analyses and a p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

A total of 258 patients using CSII were admitted during the study period. Of these, 42 patients met at least one exclusion criteria. No patient in the CSII group (including the 42 excluded patients) made any adjustments to their pump settings during the first 24 hours of admission, and therefore no patients in the CSII group were excluded for this reason. The final cohort included 216 patients using CSII and 216 age-matched patients treated with MDI. Of the 432 patients included in the study, 263 (60.9%) were male and the mean age was 63 years. Demographic variables and clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. Compared to the MDI group, the CSII group had a higher prevalence of type 1 diabetes, lower admission creatinine and lower admission blood glucose. Patients using CSII were less frequently admitted to the medicine service and more frequently admitted to surgery and obstetrics than patients using MDI. The average blood glucose over the first 24 hours of hospital admission was lower in the CSII group, although the total number of glucose tests was lower in this group as well. Endocrinology consultations within the first 24 hours of admission were more frequent in the CSII group. Other variables were not significantly different between groups.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics.

| Variable | Overall (N = 432) | CSII (N = 216) | MDI (N = 216) | p-value † |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63 (53-70) | 63 (53-70) | 63 (53-70) | 1.000 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.554 | |||

| Male | 263 (60.9) | 135 (62.5) | 128 (59.3) | |

| Female | 169 (39.1) | 81 (37.5) | 88 (40.7) | |

| Diabetes type, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Type1 | 120 (28.2) | 100 (47.6) | 20 (9.3) | |

| Type2 | 305 (71.8) | 110 (52.4) | 195 (90.7) | |

| Endocrinology Consult, n (%) | 255 (59.0) | 216 (100) | 39 (18.1) | <0.0001 |

| Admitting Services, n (%) | 0.025 | |||

| Medicine | 305 (70.6) | 139 (64.3) | 166 (76.9) | |

| Surgery | 100 (23.1) | 60 (27.8) | 40 (18.5) | |

| Obstetrics | 10 (2.3) | 8 (3.7) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Neurology | 15 (3.5) | 8 (3.7) | 7 (3.2) | |

| Pediatrics | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | |

| ICU admission | 10 (2.3) | 6 (2.8) | 4 (1.8) | 0.751 |

| Steroid use, n (%) | 16 (7.6) | 11 (5.1) | 0.324 | |

| Hemoglobin A1c [%] | 7.6 (6.7-8.9) | 7.6 (6.8-8.3) | 7.6 (6.6-9.7) | 0.384 |

| Creatinine on admission, mg/dL | 1.3 (0.9-2.7) | 1.1 (0.8-2.3) | 1.5 (1.0-3.1) | <0.001 |

| Admission blood glucose, mg/dL | 182 (129-272) | 176 (129-229) | 192 (129-307) | 0.035 |

| Total number of glucose values over 24 hours | 7 (5-10) | 6 (4-9) | 8 (5-11) | <0.001 |

| Average blood glucose over 24 hours, mg/dL | 172 (136-214) | 165 (134-195) | 178 (139-234) | 0.009 |

p-values are from Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Values are listed as median [interquartile range] unless otherwise specified.

BG = blood glucose; CSII = continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; DM = diabetes mellitus; MDI, multiple daily injections.

Hypoglycemia

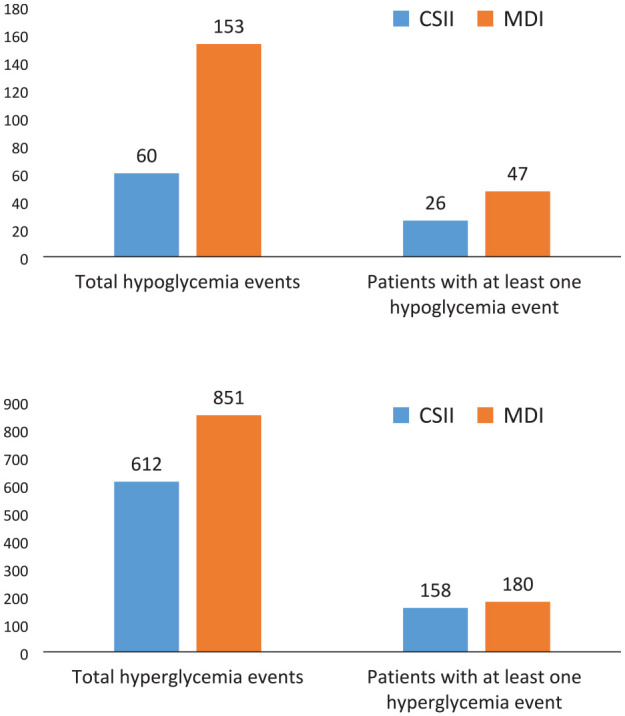

There were significantly less hypoglycemia in the CSII group compared to the MDI group. There were 60 total hypoglycemic events in 26 patients using CSII and 153 total hypoglycemic events in 47 patients using MDI (Figure 1). Adjusted for relevant covariates, the number of hypoglycemic events in patients using CSII is expected to decrease by 39% compared to patients treated with MDI [incident risk ratio (IRR) (95% CI) = 0.61 (0.42-0.88), p = 0.007]. Serum creatinine on admission and blood glucose on admission were also significantly associated with frequency of hypoglycemia. There was a 10% increase in hypoglycemic events for every 0.1 mg/dL increase in admission creatinine, and a 1% decrease in hypoglycemic events for every 10 mg/dL increase in admission BG. Type of diabetes (type 1 diabetes vs type 2 diabetes) was not associated with frequency of hypoglycemia (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Top graph: Distribution of hypoglycemia (blood glucose <70 mg/dL) in patients using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) vs patients using multiple daily injections (MDI) of insulin. Bottom graph: Distribution of hyperglycemia (blood glucose ≥180 mg/dL) in patients using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) vs patients using multiple daily injections (MDI) of insulin.

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Incidence of Hypoglycemia.

| Variable | IRR (95% CI) † | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin Pump use | 0.61 (0.42–0.88) | 0.007 |

| Diabetes Type 1 vs Type 2 | 1.36 (0.97–1.89) | 0.077 |

| Creatinine on admission (per 0.1 mg/dL) | 1.10 (1.02–1.16) | <0.001 |

| Blood glucose on admission (per 10 mg/dL) | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.018 |

IRR (Incidence Rate Ratio) estimated via zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) model. This model considered the following variables: insulin pump use, sex, diabetes type, steroid use, hemoglobin A1c, admission creatinine, admission glucose.

Hyperglycemia

There were significantly less hyperglycemic events in patients using CSII. Fifty-eight patients (27%) using CSII did not have any hyperglycemic events as opposed to 36 patients (17%) using MDI (Figure 1). Adjusted for relative covariates, the number of hyperglycemic events is expected to decrease by 21% in patients using CSII [IRR (95% CI) = 0.79 (0.65-0.96), p = 0.02]. Type 1 diabetes and incremental increases in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and admission BG were also associated with a higher frequency of hyperglycemia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Incidence of Hyperglycemia.

| Variable | IRR (95% CI) ‡ | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin Pump use | 0.79 (0.65–0.96) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes Type 1 vs Type 2 | 1.40 (1.13–1.72) | 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | <0.0001 |

| Blood glucose on admission (per 10 mg/dL) | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.0001 |

IRR (Incidence Rate Ratio) estimated via Negative Binomial Regression. This model considered the following variables: insulin pump use, sex, diabetes type, steroid use, hemoglobin A1c, admission creatinine, admission glucose.

Severe Hypoglycemia

Severe hypoglycemia was identified in one patient (0.5%) using CSII who experienced two events, and in 7 patients (3.3%) using MDI with a total of 17 events. There was a trend toward fewer events of severe hypoglycemia in the CSII group ([IRR (95 % CI) = 0.15 (0.02-0.93)], but this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.06).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze glycemic outcomes within the first 24 hours of admission in patients using CSII. Our findings support the continuation of CSII when patients are admitted to the hospital, while maintaining their outpatient insulin pump settings. Patients using CSII were found to not only have fewer events of hypoglycemia (defined as BG < 70 mg/dL) but were also found to have lower average blood glucose over 24 hours and fewer events of hyperglycemia (BG ≥ 180 mg/dL) early in their hospitalization compared to patients using MDI. Adverse outcomes such as severe hypoglycemia (BG < 40 mg/dL) were seen infrequently in both groups, with a trend toward fewer events of severe hypoglycemia in the CSII group.

Not surprisingly, other findings of this study were higher rates of hypoglycemia in patients with higher creatinine levels and lower blood glucose on admission, and higher rates of hyperglycemia in those with higher HbA1c, higher blood glucose on admission and patients with type 1 diabetes.

As CSII becomes more popular, more users are admitted to the hospital and continue to use CSII while hospitalized. 9 Studies suggest that with standardized protocols and careful patient selection, insulin pumps can be safely used in the hospital. Cook et al. retrospectively analyzed the clinical course of hospitalized patients throughout hospitalization using CSII who either continued CSII throughout the hospitalization, discontinued CSII and converted to MDI on admission, or intermittently used CSII while hospitalized. 4 Events of severe hyperglycemia (>300 mg/dL) and hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL) were significantly less common among both continued and intermittent CSII users. Bailon et al. compared patients (n = 35 patients) who changed from CSII to MDI on admission to those who continued using CSII, and found a lower incidence of hypoglycemia in those who continued using CSII. 10 The study by Bailon and colleagues did not find a difference in the incidence of hyperglycemia between groups.

The American Diabetes Association, 11 Diabetes Technology Society, 8 and The Joint Commission Advanced Inpatient Diabetes Care Certification standards 7 recommend institutional insulin pump policies and expert consultation for use of insulin pumps in the inpatient setting. Many programs have established requirements for inpatient use of CSII including consultation with an endocrinologist or physician experienced in diabetes management. 7 However, specialist assistance is not always available early in a hospital admission, potentially increasing the risk of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia during that time. Our study demonstrates that in the initial phase of hospitalization, patients using CSII may safely maintain their outpatient pump settings while awaiting evaluation from a diabetes specialist. As our institution requires endocrinology consultation for all patients using CSII, all patients using CSII had an evaluation by a consulting endocrinologist within the first 24 hours of admission, compared to only a minority (18%) of patients in the MDI group. However, this is unlikely to be the reason for the superior glycemic outcomes in the former group, as no pump setting changes were made by patients using CSII within the 24-hour period evaluated in this study.

Other studies have evaluated the impact of specialist assistance throughout the hospitalization. Noschese and colleagues’ study of a quality improvement initiative compared the use of an inpatient insulin pump protocol (IIPP) (n = 12) with the use of an IIPP along with diabetes service consultation (n = 34) with a third control group receiving neither intervention (n = 4). 12 They found no difference in the incidence of hypoglycemia among the three groups. However, the control group had a higher incidence of hyperglycemia defined as capillary BG > 300 mg/dL.

Our study has several limitations. It is a single center retrospective study limited by a small pool of patients using insulin pumps who were matched with controls by age only. We did not examine potential confounding factors including differences in nutrition between the groups and insulin type and dosing of insulin through insulin pumps. In addition, because we studied the clinical course of patients within the first 24 hours of admission, oral antihyperglycemic agents taken prior to admission in the MDI group may have affected glycemic outcomes. Patients using CSII were also found to have a lower creatinine on admission, which may have contributed to their lower incidence of hypoglycemia. Also, we did not account for patient specific factors, such as prior formal diabetes education, which may determine which patients choose to use an insulin pump prior to admission and which choose to use MDI. These factors may also impact glycemic outcomes when patients are admitted to the hospital.

Another potential limitation is that we did not account for the impact of continuous glucose monitors (CGM) in conjunction with CSII. CGM can detect declining blood glucose and allow treatment or suspension of insulin delivery prior to the development of hypoglycemia, and can similarly help mitigate hyperglycemia by alerting users to rising glucose levels. CGM use is increasing, and future studies on the impact of CGM use on the safety of CSII in the hospital would be informative.

Conclusion

Patients using CSII in the first 24 hours of hospital admission experienced fewer events of both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia than those treated with MDI despite maintaining outpatient pump settings calculated for outpatient glucose targets. Our study demonstrates that CSII use is safe and effective for the treatment of diabetes within the first 24 hours of hospital admission when insulin is infusing based on outpatient insulin pump settings.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BG, Blood Glucose; CGM, Continuous glucose monitor; CSII, Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; MDI, Multiple Daily Injections.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Gary Rothberger  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4955-1458

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4955-1458

References

- 1. Bode BW, Sabbah HT, Gross TM, Fredrickson LP, Davidson PC. Diabetes management in the new millennium using insulin pump therapy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18(suppl 1):S14-S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Umpierrez GE, Klonoff DC. Diabetes technology update: use of insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitoring in the hospital. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(8):1579-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mendez CE, Umpierrez GE. Management of type 1 diabetes in the hospital setting. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17(10):98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cook CB, Beer KA, Seifert KM, Boyle ME, Mackey PA, Castro JC. Transitioning insulin pump therapy from the outpatient to the inpatient setting: a review of 6 years’ experience with 253 cases. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6(5):995-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kannan S, Satra A, Calogeras E, Lock P, Lansang MC. Insulin pump patient characteristics and glucose control in the hospitalized setting. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8(3):473-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Diabetes Association. 15. Diabetes care in the hospital: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S211-S220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arnold P, Scheurer D, Dake AW, et al. Hospital guidelines for diabetes management and the Joint Commission-American Diabetes Association inpatient diabetes certification. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351(4):333-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thompson B, Korytkowski M, Klonoff DC, Cook CB. Consensus statement on use of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion in the hospital. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(4):880-889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Houlden RL, Moore S. In-hospital management of adults using insulin pump therapy. Can J Diabetes. 2014;38(2):126-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bailon RM, Partlow BJ, Miller-Cage V, et al. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (insulin pump) therapy can be safely used in the hospital in select patients. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(1):24-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Diabetes Association. 7. Diabetes technology: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Noschese ML, DiNardo MM, Donihi AC, et al. Patient outcomes after implementation of a protocol for inpatient insulin pump therapy. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(5):415-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]