Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study is to report our experience with a case of punctate inner choroidopathy (PIC) reactivation following COVID-19.

Case report:

A 29-year-old caucasian woman with past ophthalmological history of bilateral PIC reported sudden visual acuity decrease in her right eye (RE) 3 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Her best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/32 in RE; fundus examination and multimodal imaging (including indocyanine-green angiography, fundus autofluorescence, and optical coherence tomography) was consistent with unilateral PIC reactivation. The active choroidal lesions responded to high-dose corticosteroids, with functional improvement.

Conclusion:

Sars-CoV-2 infection could induce autoimmune and autoinflammatory dysregulation in genetically predisposed subjects. We report a case of PIC reactivation following COVID-19.

Keywords: Retinal pathology, choroidal/retinal inflammation, immunology, retina

Introduction

COVID-19 is caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It is a highly infective RNA virus, transmitted primarily through respiratory droplets. Although SARS CoV-2 mainly affects the respiratory tract, it has been reported that other organs might be involved in the disease as part of a systemic inflammatory syndrome, such as skin, central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, and the eye.1,2

We report the case of a young female who suffered from punctate inner choroidopathy (PIC) reactivation after COVID-19 infection.

Case description

A 29-year-old caucasian woman presented to our Department reporting an acute decrease of visual acuity in her right eye (RE). Past medical history was unremarkable while past ophthalmological history was remarkable for bilateral PIC complicated by secondary choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in the left eye (LE). The disease was in a clinically quiescent phase for the past 2 years. The patient tested positive for SARS-Cov-2 after a nasopharyngeal swab 3 weeks earlier and presented a mild symptomatic disease, for which no drugs were prescribed. On initial observation best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/32 in the RE and 20/400 in the LE. Intraocular pressure with Goldmann applanation tonometry was 16 mmHg in the RE and 14 mmHg in the LE. Ophthalmological examination of the anterior segment was unremarkable, without presence of anterior chamber inflammation. Fundus examination of the RE showed multiple, small, scattered, yellowish punctate lesions at the level of the choroid and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). In the LE a large fibrotic scar in the macula and numerous various-sized pigmented atrophic foci in the posterior pole were seen. No vitritis was present in either eyes.

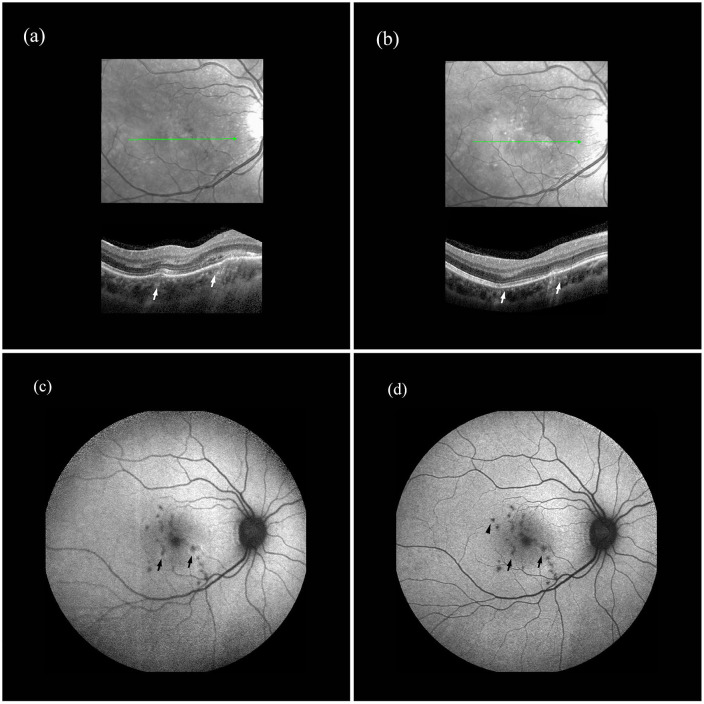

On the same day the patient underwent an enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI-OCT) that showed in the RE multiple macular RPE atrophic spots, two RPE elevations that were not present in the previous EDI-OCT, performed 2 months before, and a localized homogeneous hyperreflective signal below the RPE bumps (Figure 1). One of the two lesions presented also a disruption of the ellipsoid zone, with hyperreflective material extending anteriorly through the interdigitation zone, ellipsoid zone, and outer nuclear layer with intraretinal fluid. The EDI-OCT scan highlighted also a thick and congested choroid.

Figure 1.

Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI-OCT) and fundus autofluorescence (FAF) of the right eye (RE) at presentation and after treatment: (a) EDI-OCT of the RE showing the two RPE elevations (arrows) and a localized homogeneous hyperreflective signal below the RPE bumps. One of the two lesions presents a disruption of the ellipsoid zone, with hyperreflective material extending anteriorly through the interdigitation zone, ellipsoid zone, and outer nuclear layer with intraretinal fluid. The scan highlights also a thick and congested choroid, (b) EDI-OCT of the RE after treatment, with complete regression of RPE elevation and a fainter hyperreflective signal under the RPE; the photoreceptor inner/outer segment junction discontinuities are less marked and the intraretinal fluid has disappeared. Moreover, a decrease in choroidal thickness can be appreciated, (c) FAF of the RE at baseline revealing multiple hypoautofluorescent spots in the macula. The two new-onset RPE lesions (arrows) appear as hypoautofluorescent spots surrounded by hyperautofluorescent margins, and (d) FAF of the RE after treatment, with disappearance of hyperautofluorescence at lesions’ margins (arrows). A new-onset hypoautofluorescent spot can be appreciated in the macula (arrowhead).

OCT of the LE showed confluent RPE atrophic lesions and subfoveal hyperreflective fibrotic material as a result of a previously active CNV.

Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) of the RE revealed multiple hypoautofluorescent spots in the macula. The two new-onset RPE lesions appeared as hypoautofluorescent spots surrounded by hyperautofluorescent margins (Figure 1). A confluent hypoautofluorescent area was seen at the posterior pole in the LE.

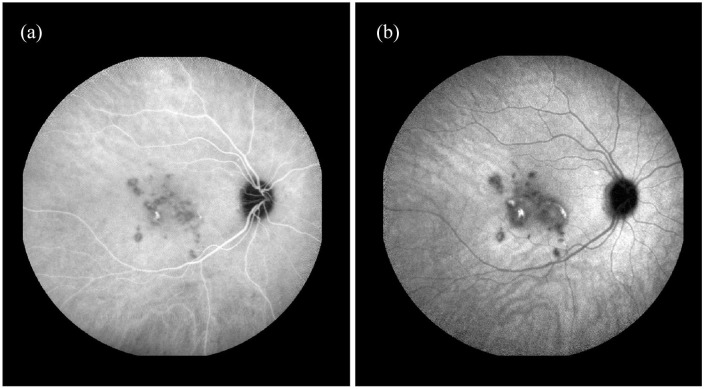

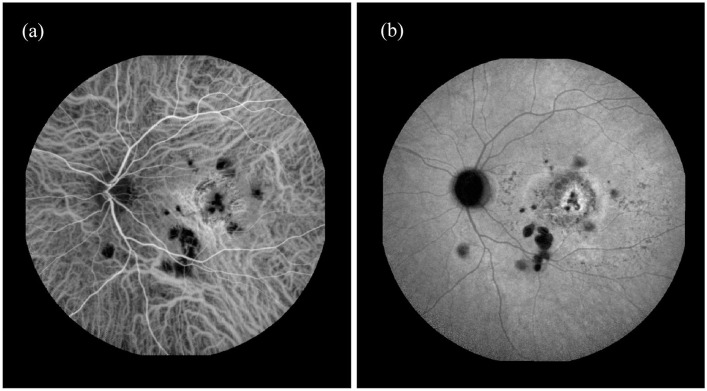

Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) showed multiple hypocyanescent lesions in the posterior pole in both eyes (Figures 2 and 3). In the RE, a mild central hypercyanescence was noted inside the two lesions during intermediate and late phases with an intense hypercyanescence crescent area at the margin (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Midphase Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) of right eye showing multiple hypocyanescent lesions in the posterior pole with mild central hypercianescence. Two active lesions show intense hypercianescence in the midphase with staining in the (b) late phase.

Figure 3.

Early and late phase indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) of left eye (LE): (a) early phase ICGA of LE showing multiple hypocyanescent lesions in the posterior pole with a central area of hypercyanescence caused by a window effect and (b) late phase ICGA of LE showing multiple hypocyanescent lesions in the posterior pole with hypo/hypercyanescent area and dye staining without leakage corresponding to fibrotic lesion as result of chorioretinal neovascularization.

Two days later, after administration of systemic methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/day), visual acuity of the RE improved to 20/20.

EDI-OCT of the RE showed complete regression of RPE elevation and a fainter hyperreflective signal under the RPE; the photoreceptor inner/outer segment junction discontinuities were less marked and the intraretinal fluid disappeared. Moreover a decrease in choroidal thickness could be seen, and on FAF hyperautofluorescence at lesions margins disappeared (Figure 1).

Conclusions

PIC is an idiopathic inflammatory multifocal chorioretinopathy that commonly affects young myopic women. The etiology of PIC is unknown, but it is proposed to be an autoimmune disease induced by an environmental stimulus, such as viral infection, that can act as a trigger in genetically susceptible individuals.3,4

SARS-CoV-2 is known to cause a massive activation of the immune system, and it could act as a trigger for the development of autoimmune and autoinflammatory dysregulation in genetically predisposed subjects. In fact, SARS-CoV-2 seems to create two different phases: the first represented by the primary infection which induces the triggering of the immune system, while the second phase has many features of an autoimmune disease. Suggested mechanisms of autoimmunity induction include both molecular mimicry as well as activation of antigen presenting cells leading to the production of pro-inflammatory mediators with consequential tissue damage.5

Despite the effort of the global scientific community, the etiopathology of the diseases induced by the SARS-CoV-2 infection and its collateral autoimmune pathologic sequelae remains unclear.5

Our patient had been suffering from bilateral PIC, her treatment with Cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/day had been stopped 6 months before, and her disease had been in phase of quiescence for about 2 years.

According to the temporal connection between Sars-CoV-2 infection and the reactivation of the choroidopathy, and excluding other possible causes, we can assume that COVID-19 could be the factor that led to autoimmune dysregulation and triggered the reactivation of the retinal pathology.

The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the human retina6 and retinal changes associated with COVID-19 were recently described.7 Although in literature other choriocapillaropathies and retinal pathologies have been described to recur or occur after COVID-19,8–10 to the best of our knowledge this is the first report of PIC reactivation after Sars-CoV-2 infection. Sars-CoV-2 infection could induce autoimmune and autoinflammatory dysregulation in genetically predisposed subjects. Further studies are needed in order to increase knowledge about ocular involvement in COVID-19 infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this report.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Michele Nicolai https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8302-6107

Nicola Vito Lassandro https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1151-7887

Paolo Pelliccioni https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6024-0183

Alessandro Franceschi https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8867-4488

References

- 1.Bertoli F, Veritti D, Danese C, et al. Ocular findings in COVID-19 patients: a review of direct manifestations and indirect effects on the eye. J Ophthalmol 2020; 2020: 4827304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machhi J, Herskovitz J, Senan AM, et al. The natural history, pathobiology, and clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infections. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2020; 15(3): 359–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jampol LM, Becker KG.White spot syndromes of the retina: a hypothesis based on the common genetic hypothesis of autoimmune/inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 135(3): 376–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borkar PP, Grassi MA.Unilateral multifocal choroiditis following EBV-positive mononucleosis responsive to immunosuppression: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol 2020; 9; 20(1): 273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrenfeld M, Tincani A, Andreoli L, et al. Covid-19 and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev 2020; 19(8): 102597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casagrande M, Fitzek A, Püschel K, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in human retinal biopsies of deceased COVID-19 patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2020; 28(5): 721–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marinho PM, Marcos AAA, Romano AC, et al. Retinal findings in patients with COVID-19. Lancet 2020; 395(10237): 1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Providência J, Fonseca C, Henriques F, et al. Serpiginous choroiditis presenting after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a new immunological trigger? Eur J Ophthalmol. Epub ahead of print 2 December 2020. DOI: 10.1177/1120672120977817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortiz-Seller A, Martínez Costa L, Hernández-Pons A, et al. Ophthalmic and neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2020; 28(8): 1285–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gascon P, Briantais A, Bertrand E, et al. Covid-19-associated retinopathy: a case report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2020; 28(8): 1293–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]