Abstract

BACKGROUND

Rubber band ligation (RBL) using rigid anoscope is a commonly recommended therapy for grade I-III symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Severe complications of RBL include pain, hemorrhage and sepsis. Flexible endoscopic RBL (ERBL) is now more commonly used in RBL therapy but few severe complications have been reported. Here we report on a case of massive bleeding after ERBL.

CASE SUMMARY

A 31-year-old female was admitted to the department of gastroenterology with a chief complaint of discontinuous hematochezia for 2 years. No previous history, accompanying diseases or drug use was reported. Physical examination and colonoscopy showed grade II internal hemorrhoids. The patient received ERBL therapy. Five days after ligation, the patient presented with mild hematochezia. On days 7 and 9 after ligation, she presented with a large amount of rectal bleeding, dizziness and weakness. Emergency colonoscopy revealed active bleeding and an ulcer in the anal wound. The patient received two sessions of hemoclipping on days 7 and 9 to treat the bleeding. No further bleeding was reported up to day 15 and she was discharged home. Although the hemorrhoid prolapse disappeared after ERBL, she was dissatisfied with the subsequent complications.

CONCLUSION

ERBL therapy is an effective treatment for symptomatic internal hemorrhoids with satisfactory short and long-term recovery. Pain and anal bleeding are the most frequently reported postoperative complications. Coagulation disorders complicate the increased risk of bleeding. Although rarely reported, our case reminds us that those patients without coagulation disorders are also at risk of massive life-threatening bleeding and need strict follow-up after ligation.

Keywords: Internal hemorrhoids, Endoscopy, Rubber band ligation, Complication, Bleeding, Case report

Core Tip: Endoscopic rubber band ligation (ERBL) is an effective treatment for symptomatic internal hemorrhoids and few severe complications have been found. A 31-year-old female with grade II internal hemorrhoids received ERBL therapy. No previous history or coagulation disorder was reported. Meanwhile, she presented with delayed massive rectal bleeding after the ligation. Colonoscopy showed active bleeding and ulcers in the anal wound. Coagulation disorders were previously reported in relation to bleeding after ligation. However, this case reminds us that patients without coagulation disorders are also at risk for massive life-threatening bleeding after ERBL.

INTRODUCTION

Internal hemorrhoids are a common lower gastrointestinal disease and a main cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding[1,2]. Rubber band ligation (RBL) is a commonly recommended therapy for grade I-III symptomatic internal hemorrhoids[1,3,4]. However, several life-threatening complications have been reported including massive hemorrhage and perirectal sepsis[5,6]. Due to the development of flexible endoscopy, it has been more widely used for the treatment of internal hemorrhoids. Flexible endoscopy is feasible for ligation in both forward-view and retroflexion. The advantage of the retroflexion procedure is its easy operation in the anal zone, though it may induce more pain[7]. Several complications (pain, anal discomfort, lower gastrointestinal bleeding and early detachment) have been reported in endoscopic RBL (ERBL)[7]. However, few severe complications have been reported.

Here, we report on a case of internal hemorrhoid therapy which caused rare massive hemorrhage after ERBL. Furthermore, we reviewed the latest article involving the effects and complications of ERBL hoping to provide clinical reference for this therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 31-year-old Asian female presented with a chief complaint of discontinuous hematochezia for 2 years at the Department of Gastroenterology.

History of present illness

The patient generally had lower gastrointestinal bleeding occurring at the end of defecation 3-4 times per week along with several drops of bright red blood in the past 2 years. She frequently experienced prolapsed hemorrhoids that automatically retracted after defecation. Her stool habit was normal with a frequency of 1-2 times per day. The patient adjusted her lifestyle by reducing sedentary behaviors, stress and maintaining regular stool habits. However, these measures failed to improve her symptoms. Warm water baths and ointments could temporarily reduce bleeding but the patient was dissatisfied and required more aggressive treatment which included endoscopic therapy.

History of past illness

No other previous history or accompanied diseases were reported. The patient denied any use of anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs.

Personal and family history

The patient denied any history of smoking, alcohol use or food and drug allergies. She had no family history of gastrointestinal tumors or genetic diseases.

Physical examination

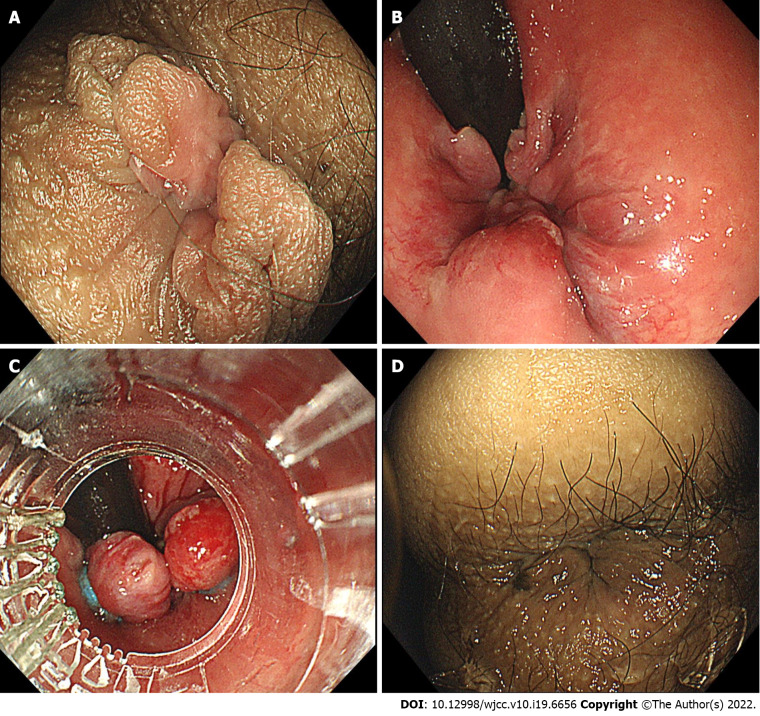

The patient’s temperature was 36.2 °C, heart rate was 80 bpm, breath rate was 18 bpm and blood pressure was 126/82 mmHg. Examination of the chest, lungs and abdomen showed no abnormalities. Examination of the anus showed prolapsed hemorrhoids during defecate movements (Figure 1A), and it was found to automatically retract after defecation. Digital rectal examination revealed enlarged hemorrhoids and no bloodstain was left on gloves.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic images of endoscopic rubber band ligation therapy. A: Prolapsed hemorrhoids in forward view before endoscopic rubber band ligation (ERBL); B: Retroflexion view of hemorrhoids before ERBL; C: Ligation of hemorrhoids during ERBL; D: the prolapsed hemorrhoid tissue was withdrawn into the anus after ERBL.

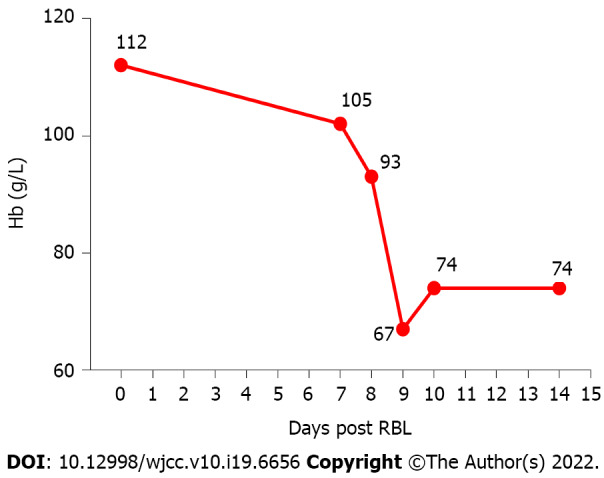

Laboratory examinations

Regular preoperative examination, including routine blood work, liver and kidney function tests, coagulation function and electrocardiography was performed before ERBL. The patient’s hemoglobin (Hb) was 112 g/L and no other abnormal results were reported.

Endoscopy

Flexible colonoscopy was performed under intraprocedural analgesia with Diprivan, which revealed normal colorectal mucosa and internal hemorrhoids with positive red color sign (Figure 1B).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The patient was diagnosed with grade II internal hemorrhoids and mild anemia.

TREATMENT

For the convenience of the patient, we performed ERBL with endoscopic examination continuously. In order to manage the patient with better postoperative care, the patient underwent hospital admission. Following the colonoscopy examination, the patient was treated with ERBL therapy using Multiple Band Ligator (Boston Scientific, Speedband Superview Super 7TM, 7 Bands). Five rubber bands were applied to the hemorrhoids (Figure 1C). She received Diprivan (Propofol Injection, 20 mL, 200 mg) for anesthesia during the endoscopic examination and ERBL therapy to avoid intraoperative pain. After ligation, the prolapsed hemorrhoid tissue was withdrawn into the anus (Figure 1D). After ERBL, the patient was advised to take a light diet to avoid bleeding and oral laxatives (10 mL, tid) were given to soften the stool.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Approximately 4 h after ligation, the patient felt mild anal pain and nausea. An intramuscular injection of 10 mg of Tramadol rapidly remitted the pain. 24 h after ligation, the patient was permitted to eat a light food diet. Lactulose (10 mL, tid, po) was given to soften the stool and to prevent post-ERBL bleeding. 5 d after ligation, the patient did not report rectal bleeding during defecation and the prolapse had significantly improved. Therefore, she was discharged to home following the doctors’ advice.

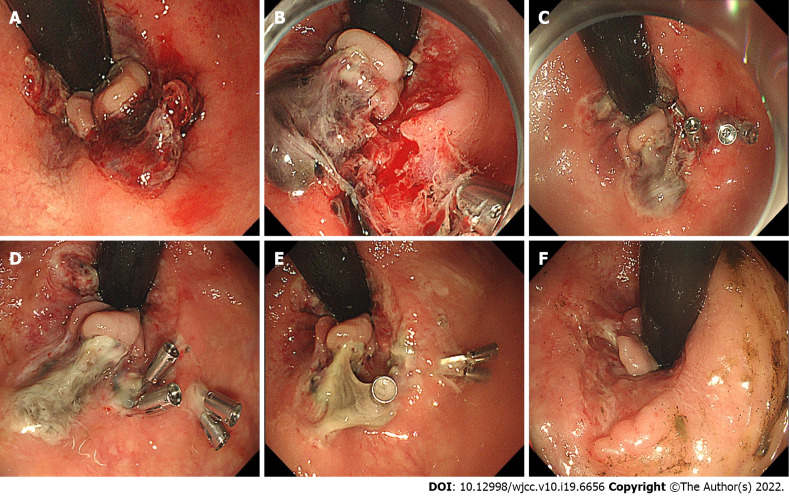

On day 7 after ligation, she was sent to the emergency department with significant painless fresh rectal bleeding of approximately 400 mL, accompanied by systemic symptoms of dizziness and weakness. Emergency colonoscopy showed active oozing of blood in the anal wound (Figure 2A). Endoscopic electrosurgical hemostatic forceps (FD-410LR, Olympus Corporation) was used first. However, it failed to stop the active bleeding. Then two hemoclips (ROCC-D-26-195-C, Micro-Tech (Nanjing) Co., Ltd, Maximum Span width = 10 mm) were applied to stop the bleeding. Finally, the patient was sent to the ward safely with a Hb level of 93 g/L (Figure 3). However, early on day 9, she suddenly presented with large amounts of rectal bleeding of over 800 mL and fainted during defecation. Blood pressure was 95/50 mmHg and pulse was 116 beats/min. Resuscitation with oxygen and intravenous fluids with electrolyte solution was initiated. She was immediately sent to the endoscopic department under electrocardiographic monitoring. Emergency colonoscopy showed that all rubber bands had slipped off leaving multiple bleeding ulcers in the anal wound (Figure 2B). Ischemic necrotic tissue containing 1 hemoclip was removed by forceps (FG-32L-1, Olympus Corporation), and 3 more hemoclips were placed and successfully stopped the bleeding (Figure 2C). The patient received fluid infusion for symptomatic treatment and omidazole (200 mg qd iv) was used to prevent infection. Although the routine blood test revealed a Hb of merely 67 g/L (Figure 3), the patient refused blood transfusion. No further bleeding was reported until 15 d after ligation. A re-examination by colonoscopy on days 12 and 15 showed a gradually healed wound covered by ischemic scabs (Figure 2D and E). The patient was discharged home with moderate anemia and her Hb was 74 g/L (Figure 3). Although hemorrhoids prolapse disappeared after ERBL, she was dissatisfied with the subsequent complications. The duration of the hospitalization was 17 d, and the cost of the procedure was 1500$, including endoscopy + ligation therapy (800$), drugs (200$) and hospitalization (500$).

Figure 2.

Endoscopic images during follow-up study. A: Active oozing of blood on 7 d post-endoscopic rubber band ligation (ERBL); B: Ulcer and active bleeding on 9 d post-ERBL; C: image after endoscopic hemostasis using clips; D: 12 d post-ERBL; E: 15 d post-ERBL; F: 3 mo post-ERBL.

Figure 3.

Curve of hemoglobin before and after endoscopic rubber band ligation therapy.

Of 1 mo after ligation, we investigated the patient through a telephone call. No bleeding or hemorrhoids prolapse was reported. 3 mo after ligation, the patient received a re-examination and her Hb had reached 132 g/L. Colonoscopy revealed that the anal wound had healed and no hemorrhoids were found (Figure 2F).

DISCUSSION

The use of RBL on internal hemorrhoids by grasping the hemorrhoidal tissue with an elastic rubber band and this ligation causes ischemic necrosis and cicatricial fixation of the hemorrhoidal tissue. Compared with surgical methods such as excisional hemorrhoidectomy, stapled hemorrhoidectomy and hemorrhoidal artery ligation, RBL with anoscopy causes fewer postoperative complications as well as a shorter hospitalization period[8-10]. Compared with other nonsurgical methods (sclerotherapy, infrared coagulation), RBL shows a higher efficacy and a lower recurrence rate and it is more effective for prolapsed hemorrhoids[10]. ERBL has been more commonly used in the treatment of grade I-III internal hemorrhoids. The therapeutic effects of ERBL have been verified by recent studies. In an observational study including 82 patients with grade I-IV internal hemorrhoids, Fukuda et al[11] reported a significant reduction in symptom scores within 4 wk after ERBL in the retroflexed position[11]. Su et al[12] enrolled 576 patients with grade II-IV internal hemorrhoids in a 1-year follow-up study which showed that 93.58% of patients experienced at least one grade reduction in the severity of hemorrhoids after ERBL[12]. Another follow-up study including 759 patients reported that 87.0% had controlled bleeding and 83.1% had controlled prolapse rates within 5 years[13]. These results indicated that ERBL is a simple and well-tolerated treatment for symptomatic internal hemorrhoids with satisfactory short and long-term recovery[12,13]. New devices for ERBL have been developed in recent years and the more flexible gastroscope and transparent cap are increasingly used to assist ERBL operation[14]. Paikos et al[15] reported that the O'Regan disposable bander device showed good response with low complication rates in outpatients with symptomatic hemorrhoids[15]. Su et al[16] demonstrated that both small (9 mm) and large (13 mm) diameter devices showed equivalent effects on 218 cases of grade II-IV internal hemorrhoids[16]. Furthermore, ERBL has been proven to be safe for certain patients including those with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension[17,18].

Although the therapeutic advantages of ERBL on traditional RBL with anoscopy have not been evidently revealed, ERBL is increasingly preferred by operators. Endoscopy is strongly recommended to exclude other severe diseases including colorectal ulcers and cancer which share similar bleeding symptoms[19,20]. Simultaneous endoscopic examination with hemorrhoid treatments provides convenience for these patients. Flexible endoscopy is feasible for ligation in both forward-view and retroflexion. The advantage of the retroflexion procedure is its easy operation and controllability. Fukuda et al[21] demonstrated that using an endoscope in both the forward and retroflexed positions assisted with the treatment of internal hemorrhoids and allowed for an easier evaluation of range, form and red color signs which are closely related to hemorrhoid symptoms[21]. More importantly, retroflexion in the anal zone provides a better view which can help to ligate above the dentate line to avoid post-RBL pain[7]. In randomized trials performed by Cazemier et al[7], ERBL showed similar efficacy and safety compared with traditional RBL using anoscopy and the recurrence rate of bleeding symptoms using the two methods was also comparable[7]. However, the study reported that ERBL is significantly easier to perform and requires fewer treatment sessions[7].

Currently, limited research has analyzed the complications of ERBL. Pain and anal bleeding were the most frequently reported postoperative complications. In a long-term follow-up study enrolling 759 patients, Su et al[13] reported that 12.3% of patients experienced mild anal pain 1-3 d after treatment, which was relieved by oral analgesia. Overall, 6.3% of patients had mild bleeding (some blood noted in tissue papers) 1-14 d after treatment and were cured by epinephrine injection[13]. Schleinstein et al[14] reported that 55.2% of patients had pain and 29.3% of patients had mild bleeding at 2 h post-ERBL and the rate declined to 25.9% of patients having pain and 10.3% of patients having bleeding at 10-14 d with observation or symptomatic treatment[14]. When compared with other treatments, Cazemier et al[7] reported increased postoperative pain in ERBL than with traditional RBL using anoscopy[7], however, such findings remain controversial. Therefore, ERBL is generally considered a cost-effective treatment in which most complications are mild and self-confined. Severe complications are rarely reported in single cases. Jutabha et al[22] reported 2 cases of severe pain among patients who took narcotic agents but no hospitalization was needed[22]. Su et al[13,16] reported a 3 mo duration of pain that required analgesia[16] and a death due to hepatic failure[13].

In previous RBL using anoscopy, bleeding after RBL usually occurs 10-14 d after RBL when the rubber bands slough[23]. Coagulation disorders were demonstrated to increase the risk of bleeding related to RBL. Massive life-threatening post-RBL bleeding was rare but well documented (Table 1). In a prospective study enrolling 512 patients, Bat et al[23] reported 6 cases of massive post-RBL bleeding, of which 5 patients had a recent history of aminosalicylic acid (ASA) use[23]. Moreover, several case reports of life-threatening post-RBL bleeding had a history of ASA and clopidogrel[6,24,25]. Few cases of life-threatening post-ERBL bleeding have been reported and are also associated with coagulation disorders. Soetikno et al[26] reported 3 cases of severe bleeding after hemorrhoid ligation with a history of ASA/warfarin use. One of these patients accepted ERBL, resulting in an active bleeding vessel within the ulcer in the anal region[26]. Therefore, it is recommended that patients should stop anticoagulant/antiplatelet drugs in the perioperative period to prevent post-ERBL bleeding[6]. In contrast to previous reports, the patient in our case denied any use of anticoagulant/antiplatelet drug and the coagulation function examination was normal before ERBL. Furthermore, the patient underwent hospitalized observation and cautious postoperative care. She took a light diet and laxatives to soften the stool. However, all of those measures failed to prevent massive post-ERBL bleeding. No risk factors seemed to have been the clear cause of her massive bleeding.

Table 1.

Documents of massive life-threatening post-rubber band ligation/endoscopic rubber band ligation bleeding1

|

Ref.

|

Number/total

|

Risk factor

|

| Bat et al[23], 1993 | 6/512 | 5 of 6 had history of oral ASA intake |

| Marshman et al[27], 1989 | 2/241 | Oral anti-coagulants |

| Lau et al[28], 1982 | 2/212 | Not documented |

| Odelowo et al[6], 2002 | 1/none2 | Oral ASA |

| Beattie et al[24], 2004 | 2/none | Oral clopidogrel |

| Patel et al[25], 2014 | 2/none | Oral ASA |

| Soetikno et al[26], 2016 | 3/none | Oral ASA/warfarin |

Massive bleeding means over 800 mL bleeding or symptomatic anemia that requires transfusion.

None means case reports.

ASA: Aminosalicylic acid.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, ERBL is a safe and effective therapy for internal hemorrhoids with rare severe complications. However, our case reminds us that those patients who are also at risk of life-threatening bleeding and need strict follow-up after ligation, even if no coagulation disorder is present.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the patient for her consent to share the whole diagnosis and treatment procedures.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient prior to the study, agreeing for publication of this report and accompanying material.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: December 20, 2021

First decision: March 10, 2022

Article in press: May 12, 2022

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bataga SM, Romania; Okasha H, Egypt; Tamburini AM, Italy S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia CL P-Editor: Fan JR

Contributor Information

Yu-Dong Jiang, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Ying Liu, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Jian-Di Wu, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Gang-Ping Li, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Jun Liu, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Xiao-Hua Hou, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Jun Song, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China. song111jun@126.com.

References

- 1.Yamana T. Japanese Practice Guidelines for Anal Disorders I. Hemorrhoids. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2017;1:89–99. doi: 10.23922/jarc.2017-018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, Dellon ES, Eluri S, Gangarosa LM, Jensen ET, Lund JL, Pasricha S, Runge T, Schmidt M, Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Burden of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1731–1741.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Provenzale D, Ness RM, Llor X, Weiss JM, Abbadessa B, Cooper G, Early DS, Friedman M, Giardiello FM, Glaser K, Gurudu S, Halverson AL, Issaka R, Jain R, Kanth P, Kidambi T, Lazenby AJ, Maguire L, Markowitz AJ, May FP, Mayer RJ, Mehta S, Patel S, Peter S, Stanich PP, Terdiman J, Keller J, Dwyer MA, Ogba N. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Colorectal Cancer Screening, Version 2.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18:1312–1320. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Tol RR, Kleijnen J, Watson AJM, Jongen J, Altomare DF, Qvist N, Higuero T, Muris JWM, Breukink SO. European Society of ColoProctology: guideline for haemorrhoidal disease. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:650–662. doi: 10.1111/codi.14975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duchateau A, Huyghe M. Perirectal sepsis after rubber band ligation of haemorrhoids : a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2014;114:344–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odelowo OO, Mekasha G, Johnson MA. Massive life-threatening lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage following hemorrhoidal rubber band ligation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:1089–1092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cazemier M, Felt-Bersma RJ, Cuesta MA, Mulder CJ. Elastic band ligation of hemorrhoids: flexible gastroscope or rigid proctoscope? World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:585–587. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanmugam V, Thaha MA, Rabindranath KS, Campbell KL, Steele RJ, Loudon MA. Systematic review of randomized trials comparing rubber band ligation with excisional haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1481–1487. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grossi U, Gallo G, Di Tanna GL, Bracale U, Ballo M, Galasso E, Kazemi Nava A, Zucchella M, Cinetto F, Rattazzi M, Felice C, Zanus G. Surgical Management of Hemorrhoidal Disease in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review with Proportional Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/jcm11030709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown SR, Tiernan JP, Watson AJM, Biggs K, Shephard N, Wailoo AJ, Bradburn M, Alshreef A, Hind D HubBLe Study team. Haemorrhoidal artery ligation vs rubber band ligation for the management of symptomatic second-degree and third-degree haemorrhoids (HubBLe): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:356–364. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30584-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda A, Kajiyama T, Arakawa H, Kishimoto H, Someda H, Sakai M, Tsunekawa S, Chiba T. Retroflexed endoscopic multiple band ligation of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:380–384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02818-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su MY, Chiu CT, Wu CS, Ho YP, Lien JM, Tung SY, Chen PC. Endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:871–874. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su MY, Chiu CT, Lin WP, Hsu CM, Chen PC. Long-term outcome and efficacy of endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation for symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2431–2436. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i19.2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schleinstein HP, Averbach M, Averbach P, Correa PAFP, Popoutchi P, Rossini LGB. ENDOSCOPIC BAND LIGATION FOR THE TREATMENT OF HEMORRHOIDAL DISEASE. Arq Gastroenterol. 2019;56:22–27. doi: 10.1590/S0004-2803.201900000-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paikos D, Gatopoulou A, Moschos J, Koulaouzidis A, Bhat S, Tzilves D, Soufleris K, Tragiannidis D, Katsos I, Tarpagos A. Banding hemorrhoids using the O'Regan Disposable Bander. Single center experience. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:163–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su MY, Tung SY, Wu CS, Sheen IS, Chen PC, Chiu CT. Long-term results of endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation: two different devices with similar results. Endoscopy. 2003;35:416–420. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Awad AE, Soliman HH, Saif SA, Darwish AM, Mosaad S, Elfert AA. A prospective randomised comparative study of endoscopic band ligation vs injection sclerotherapy of bleeding internal haemorrhoids in patients with liver cirrhosis. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2012;13:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaher T, Ibrahim I, Ibrahim A. Endoscopic band ligation of internal haemorrhoids vs stapled haemorrhoidopexy in patients with portal hypertension. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2011;12:11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford AC, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Rodgers CC, Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. Diagnostic utility of alarm features for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2008;57:1545–1553. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.159723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madoff RD, Fleshman JW Clinical Practice Committee, American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1463–1473. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuda A, Kajiyama T, Kishimoto H, Arakawa H, Someda H, Sakai M, Seno H, Chiba T. Colonoscopic classification of internal hemorrhoids: usefulness in endoscopic band ligation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jutabha R, Jensen DM, Chavalitdhamrong D. Randomized prospective study of endoscopic rubber band ligation compared with bipolar coagulation for chronically bleeding internal hemorrhoids. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2057–2064. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bat L, Melzer E, Koler M, Dreznick Z, Shemesh E. Complications of rubber band ligation of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:287–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02053512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beattie GC, Rao MM, Campbell WJ. Secondary haemorrhage after rubber band ligation of haemorrhoids in patients taking clopidogrel--a cautionary note. Ulster Med J. 2004;73:139–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel S, Shahzad G, Rizvon K, Subramani K, Viswanathan P, Mustacchia P. Rectal ulcers and massive bleeding after hemorrhoidal band ligation while on aspirin. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:86–89. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i4.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soetikno R, Asokkumar R, Sim D, Sato T, Kaltenbach T. Use of the over-the-scope clip to treat massive bleeding at the transitional zone of the anal canal: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshman D, Huber PJ Jr, Timmerman W, Simonton CT, Odom FC, Kaplan ER. Hemorrhoidal ligation. A review of efficacy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:369–371. doi: 10.1007/BF02563683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lau WY, Chow HP, Poon GP, Wong SH. Rubber band ligation of three primary hemorrhoids in a single session. A safe and effective procedure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:336–339. doi: 10.1007/BF02553609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]