Abstract

Heparan sulfate (HS) and chondroitin sulfate (CS) are two structurally distinct natural polysaccharides. Here, we report the synthesis of a library of seven structurally homogeneous HS and CS chimeric dodecasaccharides (12-mers). The synthesis was accomplished using six HS biosynthetic enzymes and four CS biosynthetic enzymes. The chimeras contain a CS domain on the reducing end and a HS domain on the nonreducing end. The synthesized chimeras display anticoagulant activity as measured by both in vitro and ex vivo experiments. Furthermore, the anticoagulant activity of H/C 12-mer 5 is reversible by protamine, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved polypeptide to neutralize anticoagulant drug heparin. Our findings demonstrate the synthesis of unnatural HS-CS chimeric oligosaccharides using natural biosynthetic enzymes, offering a new class of glycan molecules for biological research.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Chondroitin sulfate (CS) and heparan sulfate (HS) are structurally complex and sulfated polysaccharides synthesized by all animal cells. HS contains disaccharide repeating units of glucuronic acid (GlcA) or iduronic acid (IdoA) linked to a glucosamine (GlcN) residue, with each capable of being modified by sulfation.1 HS is involved in the regulation of many physiological and pathological processes,2 such as regulation of embryonic development,3 inflammatory responses,4 viral/bacterial infections,5 and blood coagulation.6 Notably, heparin, a highly sulfated form of HS, is commonly used as an anticoagulant drug in clinics and is the treatment of choice for patients with thrombotic disorders. CS consists of a disaccharide repeating unit of N-acetylgalactosamine (Gal-NAc) linked to a GlcA, and both saccharide residues can carry sulfo groups. These modifications give rise to four different subtypes of CS polysaccharides. For example, chondroitin sulfate A (CS-A) has 4-O-sulfated GalNAc residues; chondroitin sulfate C (CS-C) has 6-O-sulfated GalNAc residues; chondroitin sulfate D (CS-D) consists of 2-O-sulfated GlcA and 6-O-sulfated GalNAc. Chondroitin sulfate E (CS-E) contains both 4-O- and 6-O-disulfate GalNAc residues. CS is usually linked to proteins on the cell surface to form proteoglycans.7,8 CS participates in signal transformation,9 cell adhesion and growth,10 cancer metastasis,11 and inflammation.

Synthesis of sequence pure HS oligosaccharides is very challenging and costly using a chemical method, especially with molecules larger than hexasaccharides with sulfations.13 Chemical synthesis of CS oligosaccharides was also reported.14,15 Another approach to prepare CS is to isolate oligosaccharides from enzyme-degraded CS polysaccharides.16 Enzymatic and chemoenzymatic approaches have become promising alternatives. The synthesis of HS involves specialized HS biosynthetic enzymes including glycosyltransferase, C5-epimerase, and sulfotransferases.17 The synthesis of CS involves another set of glycosyltransferase and sulfotransferases specialized in CS biosynthesis.18 The methods are efficient and scalable to prepare complex oligosaccharides for various applications. The number of HS and CS oligosaccharides obtained by the enzymatic and chemoenzymatic approaches has been continuously growing in recent years to support HS- and CS-related biological studies.

To expand the range of accessible oligosaccharides, we sought to develop a chemoenzymatic approach to synthesize a new class of unnatural HS-CS chimeric oligosaccharides. In this work, we reported for the first time the chemoenzymatic synthesis of chimeric HS-CS dodecasaccharides (12-mers). Different sulfation patterns were obtained to verify the robustness of the method for the synthesis of this novel class of glycans. We measured the anti-Factor Xa (FXa) activity in vitro of the oligosaccharides. Furthermore, the clearance in mouse plasma and the presence of anti-FXa in vivo were evaluated. The anti-FXa activity of H/C 12-mer 5 can be reversed with protamine. Our findings demonstrate the feasibility to synthesize HS-CS oligosaccharides using natural biosynthetic enzymes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Substrate Specificities of CS and HS Sulfotransferase.

Before carrying out the synthesis of HS-CS chimeras, we conducted substrate specificity studies of HS and CS sulfotransferases using pure CS oligosaccharide and HS oligosaccharide substrates. The biosynthetic pathways of CS and HS are distinct, involving different sets of sulfotransferases. CS and HS sulfotransferases generally have low degrees of homology, and the substrate specificities between two do not overlap.18 However, this conclusion has not been confirmed using structurally homogeneous oligosaccharides. Here, we investigated the substrate specificities of three HS sulfotransferases, covering 2-O-, 3-O-, and 6-O-sulfotransferase, and three CS sulfotransferases covering 4-O-, 6-O-, and GalNAc4S 6-O-sulfotransferase (Supplementary Table S1). Three oligosaccharide model substrates were used, including one HS N-sulfated 6-mer (NS 6-mer), chondroitin 7-mer (CS 7-mer), and chondroitin 4-O-sulfate 7-mer (CS 7-mer-4S) in the studies. Representative data from the substrate specificities of two 6-O-sulfotranferases are shown (Figure 1). In this experiment, we examined the reactivities of three oligosaccharides to HS 6-O-sulfotrasnferase (6-OST-3) and CS 6-O-sulfotransferase (CS 6-OST). Incubation of NS 6-mer with 6-OST-3 resulted in a shift in retention time for a peak with absorbance at 310 nm, suggesting that NS 6-mer reacted with 6-OST-3 (Figure 1, panel a). However, incubation of NS 6-mer with CS 6-OST did not change the retention time of the peak, suggesting that NS 6-mer did not react with CS 6-OST (Figure 1, panel a). Similar analysis was carried out for CS 7-mer and CS 7-mer-4S toward 6-OST-3 and CS 6-OST modifications (Figure 1, panel b and 1c). The data suggest that CS 6-OST sulfated CS-7-mer, but 6-OST-3 did not (Figure 1, panel b). CS 6-OST also sulfated the CS 7-mer-4S substrate to add one 6-O-sulfo group to a GalNAc residue instead of nearby GalNAc4S residues (Figure 1, panel c). 6-OST-3 did not sulfate CS 7-mer-4S (Figure 1, panel c). The structures of the products by 6-OST-3 and CS 6-OST were confirmed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis (Figure 1, panel d). Taken together, our data demonstrated that 6-OST-3 specifically sulfates GlcNS residues, whereas CS 6-OST specifically sulfates GalNAc residues, but not GalNAc4S residues.

Figure 1.

Reactivities of oligosaccharide substrates to 6-OST-3 and CS 6-OST modifications. (a) HPLC chromatograms of NS 6-mer with or without 6-OST-3 modification (right) and NS 6-mer with or without CS 6-OST modification. The reaction catalyzed by 6-OST-3 is shown on top of the panel. (b) HPLC chromatograms of CS 7-mer with or without 6-OST-3 modification (left) and CS 7-mer with or without CS 6-OST modification. The reaction catalyzed by CS 6-OST is shown on top of the panel. (c) HPLC chromatograms of CS 7-mer-4S with or without CS 6-OST modification (left) and CS 7-mer-4S with or without CS 6-OST modification. The reaction catalyzed by CS 6-OST is shown on top of the panel. (d) MW of the products after the sulfotransferase modification. The analysis was carried out by LC–MS. The keys for the shorthand symbols are shown at the bottom of the figure.

In an expansive study, we examined the substrate specificities of HS 2-O-sulfotransferase and 3-O-sulfotransferase 1, as well as CS 4-O-sulfotransferase and GalNAc4S 6-O-sulfotransferase using the three oligosaccharides followed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and LC–MS analysis (Supplementary Figure S1-S6). To measure the substrate specificity of 3-OST-1, a highly sulfated 6-mer, known as NS2S6S 6-mer (Supplementary Figure S6), was used. The data suggest that HS sulfotransferases only react with HS substrates and CS sulfotransferases only react with CS substrates.

We also examined whether the activity of 6-OST-3 is inhibited by CS oligosaccharides. To this end, a mixture of three substrates, including NS 6-mer, CS 7-mer, and CS 7-mer-4S, was incubated with 6-OST-3. HPLC analysis of the reaction mixture revealed that NS 6-mer was converted to 6-O-sulfated 6-mer products, whereas neither CS 7-mer nor CS 7-mer-4S participated in the reaction. Furthermore, we observed a high degree of conversion of the NS 6-mer substrate in the presence of two CS 7-mers, suggesting that CS oligosaccharides do not inhibit the activity of 6-OST-3 (Supplementary Figure S7). Likewise, we examined if NS 6-mer inhibits the activities of CS 6-OST of CS 4-OST using a similar method. The results showed no inhibition from NS 6-mer to CS 4-OST and CS 6-OST (Supplementary Figure S7). These results confirmed that HS sulfotransferases and CS sulfotransferases operate independently when the enzymes come in contact with the mixture of CS and HS substrates.

Synthesis of HS-CS Chimeras.

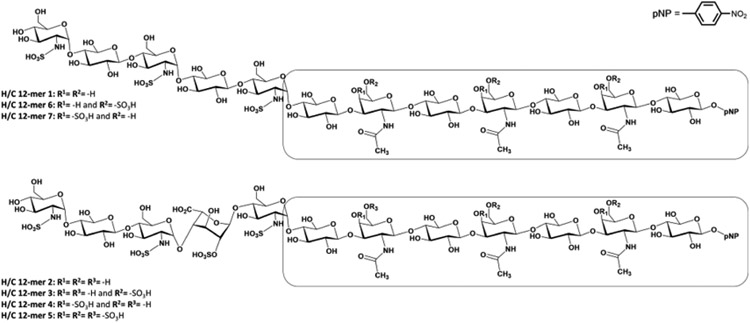

The highly regioselective substrate specificities of HS and CS sulfotransferases offer us an opportunity to examine the feasibility to synthesize HS-CS chimeras using the enzymes. For this purpose, we synthesized a total of seven chimeric HS-CS dodecasaccharides (H/C 12-mers) (Figure 2 and Table 1). Each 12-mer contains seven CS saccharide residues from the reducing end and five HS saccharides on the nonreducing end (Figure 2). The synthesis was started from a commercially available acceptor, 4-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucuronide (GlcA-pNP) and involved the use of 10 different enzymes, including two glycosyltransferases, one epimerase, and seven sulfotransferases (Supplementary Table S1). GlcA-pNP was first elongated to heptasaccharide CS 7-mer by KfoC, a glycosyltransferase from the Escherichia coli K4, with an overall yield of 85% (Figure 3, panel a). The 7-mer contains the disaccharide domain of →4)GlcA(β1 → 3)GalNAc(β1→.19 The product was further elongated to 12-mer using the Pasteurella multocida heparosan synthase 2 (PmHS2) to build the HS backbone using UDP-GlcNTFA and UDP-GlcA as sugar donors. The HS domain at the nonreducing end contains a disaccharide domain of → 4)GlcA(β1→ 4)GlcNTFA(α1→. The H/C 12-mer intermediate was subjected to mild base treatment followed by the modification by N-sulfotransferase (NST) to convert a GlcNTFA residue to a GlcNS residue to form H/C 12-mer 1. The structure of H/C 12-mer 1 was proved by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis for the numbers of saccharides and N-sulfo groups and one-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis to confirm the correct configuration of glycosidic linkages between saccharides (Supplementary Figures S8-S12).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of the HS-CS chimeras synthesized in the present study. The reducing end of each chimera contains a CS heptasaccharide domain, which is boxed for emphasis.

Table 1.

Summary of Synthesized Chimeric HS/CS Oligosaccharides Using the Chemoenzymatic Approacha

| compound ID | abbreviated saccharide sequence | calculated MW |

measured MW |

amount (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H/C 12-mer 1 | GlcNS-GlcA-GlcNS-GlcA-GlcNS-GlcA-GalNAc-GlcA-GalNAc-GlcA-GalNAc-GlcA-pnp | 252,909 | 252,831 | 100 |

| H/C 12-mer 2 | GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S-IdoA2S-GlcNS6S-GlcA-GalNAc-GlcA-GalNAc-GlcA-GalNAc-GlcA-pnp | 292,940 | 292,818 | 44 |

| H/C 12-mer 3 | GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S-IdoA2S-GlcNS6S-GlcA-GalNAc-GlcA-GalNAc6S-GlcA-GalNAc6S-GlcA-pnp | 308,953 | 308,844 | 11 |

| H/C 12-mer 4 | GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S-IdoA2S-GlcNS6S-GlcA-GalNAc4S-GlcA-GalNAc4S-GlcA-GalNAc4S-GlcA-pnp | 316,959 | 316,864 | 23 |

| H/C 12-mer 5 | GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S-IdoA2S-GlcNS6S-GlcA-GalNAc4S6S-GlcA-GalNAc4S6S-GlcA-GalNAc4S6S-GlcA-pnp | 340,978 | 340,892 | 15 |

| H/C 12-mer 6 | GlcNS-GlcA-GlcNS-GlcA-GlcNS-GlcA-GalNAc4S-GlcA-GalNAc4S-GlcA-GalNAc4S-GlcA-pnp | 276,928 | 276,832 | 11 |

| H/C 12-mer 7 | GlcNS-GlcA-GlcNS-GlcA-GlcNS-GlcA-GalNAc6S-GlcA-GalNAc6S-GlcA-GalNAc6S-GlcA-pnp | 276,928 | 276,836 | 9 |

| dekaparin | GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S-IdoA2S-GlcNS6S-IdoA2S-GlcNS6S-IdoA2S-GlcNS6S-IdoA2S-GlcNS6S-GlcA-pnp | the compound was prepared previously20 | ||

| fondaparinux | GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S-IdoA2S-GlcNS6S-OMe | purchased from local pharmacy | ||

The AT-binding region in each 12-mer is underscored.

Figure 3.

Schemes for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of chimeric H/C 12-mers. (a) Shows the synthesis CS/HS backbone. KfoC was used to construct CS 7-mer, in which the linkage GlcA and GalNAc is β1 → 3, and the linkage between GalNAc and GlcA is β1 → 4. The CS 7-mer was further elongated to the H/C 12-mer intermediate. H/C 12-mer 1 was obtained by converting GlcNTFA to GlcNS. The glycosidic linkages in the HS domain of H/C 12-mer 1 are either →4)GlcA(β1 → 4)GlcNAc(α1 → and → 4)GlcNAc(α1 → 4)GlcA(β1→. (b) Synthesis of H/C 12-mer 6 and H/C 12-mer 7 was initiated from H/C 12-mer 1 using CS-6-OST and CS 4-OST, respectively. (c) Synthesis of H/C 12-mer 2, 3, 4, and 5. The synthesis of H/C 12-mer 2 was initiated from H/C 12-mer 1 using four HS biosynthetic enzymes. H/C 12-mer 2 was converted to H/C 12-mer 3, 4, and 5 with CS-6OST, CS-4OST, and GalNAc-4S-6OST, respectively. The abbreviations for enzymes are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

H/C 12-mer 1 was modified by CS 6-OST and CS 4-OST to form H/C 12-mer 6 and 7, respectively (Figure 3, panel b). CS 6-OST and CS 4-OST specifically transfer sulfo groups to the GalNAc residues, leaving the GlcNS residues untouched. The results from structural characterization of H/C 12-mer 6 and 7 confirmed the locations of sulfo groups (Supplementary Figures S13-S22). NMR analysis was employed to locate the 6-O-sulfo group in H/C 12-mer 6. The comparison of both 1H and 13C chemical shifts of C-6 GalNAcs in H/C 12-mer 6 with the same signals of H/C 12-mer 1 permitted us to locate 6-O-sulfo groups in H/C 12-mer 6. The sulfo groups deshield both protons and carbons with a consequent downfield of the signals of C6-position from 3.8/63.9 ppm to 4.22/70.2 ppm (Supplementary Figure S14) for GalNAc residues. Likewise, 2D heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectroscopy (1H-13C HSQC) proved the complete 4-O-sulfation of GalNAc residues (residues B, D, and F) to confirm the structure of H/C 12-mer-7 (Supplementary Figures S18-S22).

Synthesis of H/C 12-mer 2 was initiated from H/C 12-mer 1 to generate the HS domain consisting of a sulfated pentasaccharide sequence with an IdoA2S residue. It should be noted that this pentasaccharide domain is present in pharmaceutical heparins that bind to antithrombin (AT) to display the anticoagulant activity. Therefore, this domain is also referred to as the “AT-binding region” in H/C 12-mer 2 (Figure 3, panel c). The synthesis of H/C 12-mer 2 from H/C 12-mer 1 involved four different HS biosynthetic enzymes as described in a previous publication (Supplementary Table S1).20 As expected, the enzymes only reacted with the HS domain on the nonreducing end of H/C 12-mer 2. To further diversify the structures, H/C 12-mer 2 was subjected to the modifications by CS 6-OST, CS 4-OST, and the combination of CS 4-OST and GalNAc4S 6-OST to generate H/C 12-mer 3, 4, and 5, respectively (Figure 3, panel c). The modification by GalNAc4S 6-OST is to install disulfated GalNAc (GlcNAc4S6S) saccharides to make H/C 12-mer 5, forming the most heavily sulfated one among seven synthesized 12-mers. The purity analyses of H/C 12-mer-2, -3, -4, and -5 were completed using anion-exchange HPLC (Supplementary Figures S23, S28, S33 and S38). Structural characterization was carried out using 1D and 2D NMR (Supplementary Figures S24-S27, S29-S32, S34-S37, and S39-S42).

Determination of the Anticoagulant Activity of Chimeras.

We determined the inhibition of the activity of Factor Xa (anti-FXa) by synthesized HS-CS 12-mers, a measurement for the anticoagulant activity. Five 12-mers were chosen for the study as they all contain the AT-binding region. We sought to determine whether the CS domain affects the interaction with AT. Among tested 12-mers, H/C 12-mer 2 contains the nonsulfated CS domain, whereas H/C 12-mer 3, 4, and 5 contain 6-O-sulfated CS, 4-O-sulfated CS, and 4,6-O-disulfated CS, respeticely. Dekaparin, an anticoagulant heparin 12-mer (Table 1), was used used as a positive control in this experiment.20 H/C 12-mer 1 was used as a negative control because it lacks the AT-binding region. All chimeric 12-mers, with the exception of H/C 12-mer 1, displayed a similar level of anti-FXa activity to dekaparin in the in vitro assay (Figure 4, panel a). The results suggest that the presence of a hybrid saccharide sequence of the CS domain and the sulfation of this CS domain do not affect the ability to inhibit the activity of FXa.

Figure 4.

Determination of the anticoagulant activity of H/C 12-mers in vitro and ex vivo. (a) 12-mer products were assessed for anti-FXa activity in a standard chromogenic assay. The values of IC50 are showed in legenda. (b) Neutralization of the anticoagulant activity of H/C 12-mers by protamine sulfate. H/C 12-mer 4 and 5 were selected for this assay. Dekaparin and Fondaparinux were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (c) Anti-FXa effects of H/C 12-mer 5 after subcutaneous injection into 8-week-old C57BL/6 J male mice. The FXa activity measurements at different time points are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). (d) Plasma concentrations of H/C 12-mer 5 at different time points in the animals after injection. The concentration of H/C 12-mer 5 was obtained based on the standard curve of the anti-FXa activity plotted against the concentration of the drug.

Next, we examined the susceptibility of the anticoagulant activity of H/C 12-mers to the neutralization by protamine. Protamine is a positively charged polypeptide and a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved reversal agent to neutralize the anticoagulant activity of unfractionated heparin. Incubation of protamine with depakarin clearly neutralized the anti-FXa from dekaparin, suggesting that the anti-FXa activity is reversible by protamine as demonstrated in a previous publication20 (Figure 4, panel b). The anti-FXa activity of H/C 12-mer 5 was also reversible by protamine although it required a higher concentration of protamine (Figure 4, panel b); however, the anti-FXa of H/C 12-mer 4 was only partially reversed by protamine. Fondaparinux is a synthetic heparin pentasaccharide approved by the FDA. Fondaparinux was used as a negative control as its anticoagulant activity is not neutralized by protamine21 (Figure 4, panel b). Our data suggest that a higher sulfation degree in the CS domain, that is, H/C 12-mer 5 displays stronger interaction with the protamine to make the 12-mer more sensitive to neutralization. Susceptibility to the neutralization by protamine reduces the bleeding risk associated with an anticoagulant drug. To investigate whether HIT patient antibodies, which recognize platelet factor 4 (PF4)/polyanion complexes, were crossreactive with the H/C 12-mer 5 when complexed PF4, we examined whether antibodies from HIT patient sera bound the H/C 12-mer 5 at various PF4: H/C 12-mer 5 molar ratios utilizing an ELISA binding assay. Here, HIT antibodies bound the H/C 12-mer 5 when PF4 was present in a range of molar ratios of monomeric PF4 to H/C 12-mer 5 (~10:1 to 2.5:1) (Supplementary Figure S43).

The anticoagulant acitvity of H/C 12-mer 5 was further examinated in vivo using a mouse model. To this end, the plasma samples were collected from the animals at different time points after H/C 12-mer 5 was administered subcutaneously. A substantial decrease in the activity of FXa was observed at 0.5 and 1.0 h time points, and the FXa acivity returned to background levels after 2 h (Figure 4, panel c). A similar clearance profile was found for enoxaparin, an FDA-approved low-molecular-weight heparin (Supplementary Figure S44). The data suggest that H/C 12-mer 5 displayed anticoagulant activity in vivo. Based on the anticoagulant activity, we also measured the concentration of the compound in the plasma, allowing us to estimate the clearance profile of the compound (Figure 4, panel d). The compound concentration reached its maximum concentration between 0.5 and 1.0 h and became undetectable after 2.0 h. This clearance profile is comparable with other HS oligosaccharides published previously.20

Preparation of chimeric proteins is a matured molecular biology technique that has transformed biological research. Here, we present a method to build chimeric glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides. CS and HS belong to two distinct families. Chimeric HS-CS oligosaccharides have not been found from biological sources so far. We describe an enzyme-based method to build HS-CS 12-mers with high efficiency. Enzymatic synthesis of hyaluronan-chondroitin chimeric oligosaccharides has been reported,22 and the oligosaccharides were used to study the mechanism of action of chondroitin lyases.23 However, the structures of hyaluronan-chondroitin oligosaccharides lack sulfo groups and thereby do not represent HS-CS chimeric oligosaccharides. In the present studies, the synthesis of seven 12-mers carrying low to high sulfation levels was achieved. We demonstrate that the chimeric oligosaccharides maintain the anticoagulant activity and the anticoagulant activity is reversible by protamine. In principle, the chemoenzymatic method is fully capable of synthesizing more complicated HS/CS chimeric oligosaccharides.

Our study demonstrates the use of two seemingly unrelated families of carbohydrate sulfotransferases to prepare a new class of glycosaminoglycan molecules, which has not been reported either using the chemical or the enzymatic methods. The process involves a total of 10 different enzymes and requires sophisticated knowledge on the substrate specificities for the enzymes to develop the synthetic schemes. Although we developed enzyme-based methods for the synthesis of homogeneous HS oligosaccharides17 and CS oligosaccharides,18 it is far from clear that combining two methods could result in the synthesis of HS-CS chimeras. Our success provides a unique set of reagents to investigate the interaction between glycosaminoglycans and proteins to display the biological functions.

Our data suggest that CS sulfotransferases or HS biosynthetic enzymes recognize the modification sites with high accuracy. Namely, the CS domain does not affect the actions of HS biosynthetic enzymes, including both sulfotransferases and C5-epimerase, and vice versa. The observation suggests that the sulfotransferases find a linear saccharide sequence in the sugar chain to execute the sulfation reaction. This conclusion is consistent with the binding of chimeric 12-mers to AT to display the anticoagulant activity. Those oligosaccharides containing the “AT-binding region” pentasaccharide sequence show strong anticoagulant activity regardless of the sulfation patterns on the reducing end CS domain. The finding for the binding of HIT patient antibody to H/C 12 mer 5, however, suggests that the chimeric oligosaccharide does not behave as two independent domains when it interacts with PF4. It is known that the AT-binding pentasaccharide does not activate platelets,24 nor does a chondroitin sulfate E 19-mer.12 The 19-mer has a repeating disaccharide sequence of →4)GlcA(β1 → 3)GalNAc4S6S-(β1→, the same disaccharide repeat found in H/C 12-mer 5. The H/C 12-mer 5, although it is a chimeric oligosaccharide with a fondaparinux-like domain and chondroitin sulfate E disaccharide domain, behaves like HS 12-mers with regard to binding PF4 and activating platelets.25

Using natural enzymes to synthesize unnatural biological active compounds has attracted substantial interest among researchers in the field of biocatalysis. We demonstrate the feasibility to conduct “out of box synthesis” of biologically active carbohydrates like glycosaminoglycans. Currently, researchers engaged in the synthesis of HS and CS are primarily focused on adding complexity on the sulfation patterns to the products. In our view, synthesis of HS-CS chimeric oligosaccharide is a new dimension for increasing the structural complexity of glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides. Mammalian cell lines, that is, Chinese hamster ovary cell (CHO) line, synthesize both CS and HS polysaccharides.26,27 Our in vitro synthesis data suggest that cellular HS and CS sulfotransferases are fully capable of generating HS-CS chimeras if the chimeric backbone is available. In fact, manipulation of the expression of different glycosaminoglycan biosynthetic enzymes in CHO cells has generated a library of polysaccharides.28 It remains to be seen if enabling CHO cells to synthesize a chimeric backbone would confer the ability to synthesize sulfated HS-CS chimeras in CHO cells. The success would offer a new set of glycan molecules for chemical and biological research.

METHODS

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Chimeric H/C 12-mer 1.

The synthesis of H/C 12-mer 1 was started from CS 7-mer. About 50 mg of CS 7-mer was elongated by incubating 80 μmol of UDP-GlcNTFA in a total 100 mL buffer with 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 15 mM MnCl2, and 3 mL PmHS2 (3.3 mg mL−1) overnight at 37 °C. HPLC equipped with an anion exchange column (ProPac PA1) was used to evaluate the completion of reaction. The product chimeric H/C 8-mer formed was purified by the C18 column (16 × 250 mm) eluted with a gradient of 0–85% buffer B (MeOH, 0.1% TFA) from buffer A (ddH2O, 0.1% TFA, pH 2.0) in 60 min, at a flow rate of 2 mL min−1 and confirmed by ESI-MS. Eluted solution was neutralized by TRIS base 1 M and then dried in a centrivap concentrator. Chimeric H/C 8-mer was then suspended in a total 100 mL buffer with 25 mM NaOAc (pH 5), 15 mM MnCl2, and 3 mL PmHS2 (3.3 mg mL−1) with 80 μmol of UDP-GlcA and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Complete reaction was purified by the C18 column using the same conditions as above. Crude chimeric H/C 9-mer was further elongated by adding 80 μmol of UDP-GlcNTFA in a 100 mL buffer solution containing 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 15 mM MnCl2, and 3 mL PmHS2 (3.3 mg mL−1). Overnight 37 °C incubation was carried out to complete reaction. The reaction mixture was centrifuged (Allegra XR-30 centrifuge) at 3000 rpm and filtered using a 0.45 μm membrane filter (Whatman). The filtered clear solution was treated with LiOH (final concentration 0.1 M) at 4 °C for 30 min to achieve the removal of the trifluoroacetyl group. The reaction completion was monitored using an anion exchange column (ProPac PA1). The reaction mixture was then neutralized using 1 M HCl. MOPS pH 7 (50 mM final concentration) was used to buffer the solution and GlcN residues were converted to GlcNS by adding 0.07 mg mL−1 NST and 140 μmol PAPS. The reaction mixture was gently shaken at room temperature for 10 min and then incubated overnight at 37 °C. HPLC equipped with an anion exchange column (ProPac PA1) was used to evaluate the completion of reaction. The product H/C 10-mer was purified using a 20 mL Giga Q column with a gradient elution; the concentration of NaCl in 20 mM NaOAc (pH 5.0) was increased from 0.05 M to 0.65 M in 240 min at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. H/C 12-mer 1 was synthesized using the same conditions as above. Briefly, H/C 10-mer was incubated overnight at 37 °C with 3 mL PmHS2 (3.3 mg mL−1) and 80 μmol of UDP-GlcA in a 100 mL buffer solution containing 25 mM NaOAc (pH 5), 15 mM MnCl2. The obtained H/C 11-mer, purified using a 20 mL Giga Q column, was subjected to the last elongation step using 80 μmol of UDP-GlcNTFA in a 100 mL buffer solution containing 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 15 mM MnCl2, and 3 mL PmHS2 (3.3 mg mL−1). Chemical detrifluoroacetylation, enzymatic sulfation, and purification were achieved as above. The purified oligosaccharide was subjected to structural characterization, MS, and NMR analysis, after removal of the salt by dialysis.

Enzymatic Sulfation and Epimerization Modifications of the Chimeric Oligosaccharide Backbone.

The conversion of N-sulfo-oligosaccharides to the final products involved three steps, including C5-epimerization/2-O-sulfation, 6-O-sulfation, and 3-O-sulfation. H/C 12-mer 1 (22 mg) was incubated in a reaction mixture containing 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.0) and 0.05 mg mL−1 C5-epimerase in a total volume of 40 mL. After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, 2-OST (0.05 mg mL−1) and 20 μmol PAPS were added, and the reaction mixture was incubated overnight at 37 °C. The product IdoA2S containing H/C 12-mer 1 was purified using a 20 mL Giga Q column as described previously. For 6-O-sulfation, the substrate was incubated overnight at 37 °C in a reaction mixture containing 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.0) and 60 μmol PAPS in the presence of 6-OST-3 (0.06 mg mL−1) in a total volume of 40 mL. The product was purified using a 20 mL Giga Q column. For 3-O-sulfation, the substrate was incubated overnight at 37 °C in a reaction mixture containing 3-OST-1 (0.08 mg mL−1), 5 mM MnCl2, and 30 μmol PAPS in a total volume of 50 mL. Purification of the final product H/C 12-mer 2 was performed using a 20 mL Giga Q column with a gradient elution set as follows: NaCl concentration in 20 mM NaOAc (pH 5.0) was increased from 0.3 to 1 M in 240 min at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The purified compound was dialyzed to remove all the salts and then subjected to MS and NMR spectroscopy for complete characterization.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH grants (HL094463, HL144970, GM123792, GM134738, and HL158932) and Glycan Innovation grants from Eshelman Innovation Institute. This work was also supported by GlycoMIP, a National Science Foundation Materials Innovation Platform funded through Cooperative Agreement DMR-1933525.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschembio.2c00146.

Synthetic procedures and analytical methods and NMR and MS spectra and HPLC chromatograms are listed as compound characterization (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Y.X. and J.L. are founders of Glycan Therapeutics and have equity. G.S. and T.Q.P. are employees of Glycan Therapeutics. V.P. is an employee of Glycan Therapeutics and has the equity of Glycan Therapeutics. J.L. lab at UNC has received a gift from Glycan Therapeutics to support research in glycosciences. A.P. has equity ownership in Retham Technologies and serves on the advisory board of Veralox Therapeutics and has patents/pending patents assigned to Versiti Inc., Retham Technologies and Mayo Clinic. E.S., W.L., R.W., J.L., Z.W., and A.K. declare no competing interest.

Contributor Information

Eduardo Stancanelli, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, United States.

Wei Liu, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Druggability of Biopharmaceuticals, State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, School of Life Science and Technology, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, PR China.

Rylee Wander, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, United States.

Jine Li, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, United States; State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China.

Zhangjie Wang, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, United States.

Katelyn Arnold, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, United States.

Guowei Su, Glycan Therapeutics, Raleigh, North Carolina 27606, United States.

Adam Kanack, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota 55904, United States.

Truong Quang Pham, Glycan Therapeutics, Raleigh, North Carolina 27606, United States.

Vijayakanth Pagadala, Glycan Therapeutics, Raleigh, North Carolina 27606, United States.

Anand Padmanabhan, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota 55904, United States.

Yongmei Xu, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, United States.

Jian Liu, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Esko JD; Selleck SB Order out of chaos: Assembly of ligand binding sites in heparan sulfate. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2002, 71, 435–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bishop J; Schuksz M; Esko JD Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology. Nature 2007, 446, 1030–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Büllow HE; Hobert O The molecular diversity of glycosaminoglycans shapes animal development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 2006, 22, 375–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Reitsma S; Slaaf DW; Vink H; van Zandvoort MAM; oude Egbrink MGA The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflugers Arch 2007, 454, 345–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Liu J; Thorp SC Heparan sulfate and the roles in assisting viral infections. Med. Res. Rev 2002, 22, 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Casu B; Naggi A; Torri G Re-visiting the structure of heparin. Carbohydr. Res 2015, 403, 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Yamaguchi Y Lecticans: organizers of the brain extracellular matrix. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2000, 57, 276–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kwok JCF; Warren P; Fawcett JW Chondroitin sulfate: A key molecule in the brain matrix. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 2012, 582–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kwok JCF; Dick G; Wang D; Fawcett JW Extracellular matrix and perineuronal nets in CNS repair. Dev. Neurobiol 2011, 71, 1073–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kastana P; Choleva E; Poimenidi E; Karamanos N; Sugahara K; Papadimitriou E Insight into the role of chondroitin sulfate E in angiogenesis. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 2921–2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Vallen MJE; Schmidt S; Oosterhof A; Bulten J; Massuger LFAG; van Kuppevelt TH Primary ovarian carcinomas and abdominal metastasis contain 4,6-disulfated chondroitin sulfate rich regions, which provide adhesive properties to tumour cells. PLoS One 2014, 9, No. e111806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Li J; Sparkenbaugh E; Su G; Zhang F; Xu Y; Xia K; He P; Baytas S; Pechauer S; Padmanabhan A; et al. Enzymatic synthesis of chondroitin sulfate E to attenuate bacteria lipopolysaccharide-induced organ failure. ACS Cent. Sci 2020, 6, 1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Liu J; Linhardt RJ Chemoenzymatic synthesis of heparan sulfate and heparin. Nat. Prod. Rep 2014, 31, 1676–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Tamura J-I; Nakada Y; Taniguchi K; Yamane M Synthesis of chondroitin sulfate E octasaccharide in a repeating region involving an acetamide auxiliary. Carbohydr. Res 2008, 343, 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Jacquinet J-C; Lopin-Bon C; Vibert A From Polymer to Size-Defined Oligomers: A Highly Divergent and Stereocontrolled Construction of Chondroitin Sulfate A, C, D, E, K, L, and M Oligomers from a Single Precursor. Chem. — Eur. J 2009, 15, 9575–9595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Zhang X; Liu H; Yao W; Meng X; Li Z Semisynthesis of Chondroitin Sulfate Oligosaccharides Based on the Enzymatic Degradation of Chondroitin. J. Org. Chem 2019, 84, 7418–7425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Xu Y; Masuko S; Takieddin M; Xu H; Liu R; Jing J; Mousa SA; Linhardt RJ; Liu J Chemoenzymatic synthesis of homogeneous ultra-low molecular weight heparin. Science 2011, 334, 498–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Li J; Su G; Liu J Enzymatic synthesis of homogeneous chondroitin sulfate oligosaccharides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 11784–11787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Arnold KM; Capuzzi SJ; Xu Y; Muratov EN; Carrick K; Szajek AY; Tropsha A; Liu J Modernization of enoxaparin molecular weight determination using homogeneous standards. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Xu Y; Chandarajoti K; Zhang X; Pagadala V; Dou W; Hoppensteadt DM; Sparkenbaugh E; Cooley B; Daily S; Key NS; et al. Synthetic oligosaccharides can replace animal-sourced low-molecular weight heparins. Sci. Transl. Med 2017, 9, No. eaan5954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Xu Y; Cai C; Chandarajoti K; Hsieh P; Lin Y; Pham TQ; Sparkenbaugh EM; Sheng J; Key NS; et al. Homogeneous and reversible low-molecular weight heparins with reversible anticoagulant activity. Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10, 248–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kakizaki I; Suto S; Tatara Y; Nakamura T; Endo M Hyaluronan-chondroitin hybrid oligosaccharides as new life science research tools. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2012, 423, 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Yin FX; Wang FS; Sheng JZ Uncovering the Catalytic Direction of Chondroitin AC Exolyase: From The Reducing End Towards The Non-Reducing End. J. Biol. Chem 2016, 291, 4399–4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Cuker A; Arepally GM; Chong BH; Cines DB; Greinacher A; Gruel Y; Linkins LA; Rodner SB; Selleng S; Warkentin TE; et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 3360–3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Nguyen TH; Xu Y; Brandt S; Mandelkow M; Raschke R; Strobel U; Delcea U; Zhou W; Liu J; Greinacher A Characterization of the interaction between platelet factor 4 and homogeneous synthetic molecular weight heparins. J. Thromb. Haemost 2019, 18, 390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Baik JY; Gasimli L; Yang B; Datta P; Zhang F; Glass CA; Esko JD; Linhardt RJ; Sharfstein ST Metabolic engineering of Chinese hamster ovary cells: towards a bioengineered heparin. Metab. Eng 2012, 14, 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Weiss RJ; Spahn PN; Toledo AG; Chiang AWT; Kellman BP; Li J; Benner C; Glass CK; Gordts PLSM; Lewis NE; et al. ZNF263 is a transcriptional regulator of heparin and heparan sulfate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2020, 117, 9311–9317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Qiu H; Shi S; Yue J; Xin M; Nairn A; Lin L; Liu X; Li G; Archer-Hartmann SA; Dela Rosa M; et al. A mutant-cell library for systematic analysis of heparan sulfate structure-function relationships Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 889–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.