Abstract

Background

The latest European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) II is a well-accepted risk evaluation system for mortality in cardiac surgery in Europe.

Objectives

To determine the performance of this new model in Taiwanese patients.

Methods

Between January 2012 and December 2014, 657 patients underwent cardiac surgery at our institution. The EuroSCORE II scores of all patients were determined preoperatively. The short-term surgical outcomes of 30-day and in-hospital mortality were evaluated to assess the performance of the EuroSCORE II.

Results

Of the 657 patients [192 women (29.22%); age 63.5 ± 12.68 years], the 30-day mortality rate was 5.48%, and the in-hospital mortality rate was 9.28%. The discrimination power of this new model was good in all populations, regardless of 30-day mortality or in-hospital mortality. Good accuracy was also noted in different procedures related to coronary artery bypass grafting, and good calibration was noted for cardiac procedures (p value > 0.05). When predicting surgical death within 30 days, the EuroSCORE II overestimated the risk (observed to expected: 0.79), but in-hospital mortality was underestimated (observed to expected: 1.33). The predictive ability [area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve] and calibration of the EuroSCORE II for 30-day mortality (0.792) and in-hospital mortality (0.825) suggested that in-hospital mortality is a better endpoint for the EuroSCORE II.

Conclusions

The new EuroSCORE II model performed well in predicting short-term outcomes among patients undergoing general cardiac surgeries. For short-term outcomes, in-hospital mortality was better than 30-day mortality as an indicator of surgical results, suggesting that it may be a better endpoint for the EuroSCORE II.

Keywords: Cardiac surgery, EuroSCORE II, In-hospital mortality, Risk evaluation, 30-day mortality

INTRODUCTION

The European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) was introduced as a standardized tool to predict operative mortality after cardiac surgery in adults.1 After extensive validation, the EuroSCORE has been applied widely in clinical settings in European nations as well as in the Pacific region.2-4 The EuroSCORE has been validated in Taiwanese patients, with acceptable results reported in certain subgroups.5,6

The new version of EuroSCORE (EuroSCORE II) was updated in 2012 to provide a better risk prediction model. Investigators and patients from 43 countries were involved in this project, and the results confirmed that the tool could be applied to patients of different ethnicities and groups.7 Several studies in the United Kingdom8 and Italy9 have reported that the new version is an acceptable cardiac surgery risk model. One study indicated that the EuroSCORE II scoring system is a reasonable risk evaluation model for low-risk coronary artery bypass graft patients; however, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Predicted Risk of Mortality seemed to perform better in the United States.10

Although several years have passed since the introduction of this modern tool, the EuroSCORE II is still not commonly accepted by cardiovascular surgeons in Asian nations. Therefore, the first objective of this study was to validate expected mortality calculated using this scoring model with real outcomes after major cardiac procedures in adult patients.

Nashef et al.7 reported that when the in-hospital mortality rate was approximately 4%, adding 30-day mortality increased it by ~0.6%, indicating that the 30-day mortality rate was higher than the in-hospital mortality rate. Owing to differences in the healthcare delivery system and culture, variations in the length of hospital stay after surgery might exist. The insurance system in Taiwan may lead to a higher hospital stay of > 30 days, and the actual mortality rate may be underestimated if only 30-day mortality is used as the surgical outcome index. Therefore, our second objective was to examine whether the score could be extended to in-hospital mortality in a healthcare system in patients who died after 30 days of hospital admission for surgery.

METHODS

Patients and data collection

This was a retrospective data review. From January 2012 to December 2014, 657 adult patients [192 women (29.22%); age 63.5 ± 12.68 years] underwent major cardiac surgery in our hospital (Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan) and were included in this study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution. Considering the high mortality rate of aortic surgery, especially aortic dissection surgery, patients undergoing surgery involving the aorta were excluded from this study. The surgeries were performed by four surgeons at the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery. All adult patients who underwent the following procedures were included:

(i) Isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery: conventional CABG and off-pump CABG.

(ii) Isolated valve surgery: aortic, mitral, tricuspid, and pulmonary valve surgeries were included, with prosthetic replacement or repair via traditional or minimally invasive or robotic-assisted techniques.

(iii) Combined valve and coronary artery surgery.

The definitions of each risk factor and the scoring system were according to the official website of the EuroSCORE (http://www.euroscore.org/calc.html), and five categories were grouped by score: very low-risk (0-2.00), low-risk (2.01-4.00), medium risk (4.01-8.00), high-risk (8.01-15.00), and very high-risk (15.01+). Data on both 30-day mortality and in-hospital mortality were collected as short-term surgical outcomes.

The EuroSCORE II scores and risk factors of all patients were entered into the critical medical chart system immediately after the surgery. The 30-day and in-hospital outcomes were collected from the electronic medical records of our institution.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the distribution. It revealed a p value > 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using a chi-square test for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The collected data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 software package (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA).

Discrimination (statistical accuracy) of the EuroSCORE II was analyzed by calculating the area under the curve (AUC or c-index) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.11 The model was considered excellent, very good, and good if the AUC was > 0.80, > 0.75, and > 0.70, respectively. Calibration (statistical precision) was tested using Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistics, where the higher the p value, the better the calibration of the model.12 The clinical performance of the EuroSCORE II model was assessed by comparing the observed and predicted mortality rates calculated using the EuroSCORE II according to the mean value with 95% confidence intervals.

With an α value of 0.05 and a β value of 0.2, the estimated overall sample size was 1035 (657 in this study), isolated CABG sample size was 808 (242 in this study), isolated aortic valve replacement (AVR) group sample size was 3234 (57 in this study), isolated mitral valve surgery group sample size was 674 (166 in this study), and the combined procedure sample size was 966 (169 in this study).

RESULTS

The prevalence of all risk factors included in the EuroSCORE II related to 30-day and in-hospital mortality are listed in Table 1. A total of 657 patients treated between January 2012 and December 2014 were included in this study. Thirty-six deaths occurred within 30 days postoperatively, and the 30-day mortality rate was 5.48%. There were 61 deaths during the same hospital admission period, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 9.28%. Of the overall cohort, 192 patients were women, and 465 were men. The mean age was 63.52 years, with a standard deviation of 12.68.

Table 1. Prevalence of risk factors compared with the 30-day and in-hospital mortality.

| Factors | Total | 30-day mortality | In-hospital mortality | |||||

| N | % | M* | % | p value# | M* | % | p value# | |

| Total | 657 | 36 | 5.48% | 61 | 9.28% | |||

| Patient-related factors | ||||||||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 63.5 ± 12.68 | 70.9 ± 13.63 | 71.6 ± 12.35 | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 192 | 29.22% | 12 | 6.20% | 0.872 | 21 | 10.90% | 0.906 |

| Male | 465 | 70.78% | 24 | 5.20% | 40 | 8.60% | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| < 50 | 93 | 14.16% | 3 | 3.20% | < 0.001 | 3 | 3.20% | < 0.001 |

| 51-70 | 367 | 55.86% | 13 | 3.50% | 21 | 5.70% | ||

| 71-80 | 143 | 21.77% | 10 | 7.00% | 22 | 15.40% | ||

| > 80 | 54 | 8.22% | 10 | 18.50% | 15 | 27.80% | ||

| Renal dysfunction | ||||||||

| Normal (CrCl rate > 85) | 94 | 14.31% | 2 | 2.10% | < 0.001 | 4 | 4.30% | < 0.001 |

| Moderate (CrCl rate 51-85) | 337 | 51.29% | 9 | 2.70% | 15 | 4.50% | ||

| Severe (CrCl rate < 50) | 179 | 27.25% | 21 | 11.70% | 36 | 20.10% | ||

| Dialysis (regardless of CrCl rate) | 47 | 7.15% | 4 | 8.50% | 6 | 12.80% | ||

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | 100 | 15.22% | 7 | 7.00% | 0.469 | 15 | 15.00% | 0.077 |

| Poor mobility | 50 | 7.61% | 6 | 12.00% | 0.141 | 11 | 22.00% | 0.026 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 26 | 3.96% | 4 | 15.40% | 0.168 | 6 | 23.10% | 0.103 |

| Chronic lung disease | 25 | 3.81% | 3 | 12.00% | 0.321 | 5 | 20.00% | 0.189 |

| Infective endocarditis | 22 | 3.35% | 1 | 4.50% | 0.845 | 2 | 9.10% | 0.975 |

| Critical preoperative state | 103 | 15.68% | 15 | 14.60% | 0.003 | 29 | 28.20% | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes on insulin | 71 | 10.81% | 10 | 14.10% | 0.026 | 17 | 23.90% | 0.002 |

| Cardiac-related factors | ||||||||

| NYHA | ||||||||

| Class I | 162 | 24.66% | 5 | 3.10% | < 0.001 | 5 | 3.10% | < 0.001 |

| Class II | 348 | 52.97% | 14 | 4.00% | 26 | 7.50% | ||

| Class III | 118 | 17.96% | 10 | 8.50% | 17 | 14.40% | ||

| Class IV | 29 | 4.41% | 7 | 24.10% | 13 | 44.80% | ||

| CCS class 4 angina | 79 | 12.02% | 9 | 11.40% | 0.073 | 13 | 16.50% | 0.064 |

| LV dysfunction | ||||||||

| Mild (LVEF > 50%) | 412 | 62.71% | 13 | 3.20% | < 0.001 | 25 | 6.10% | < 0.001 |

| Moderate (LVEF 31%-50%) | 186 | 28.31% | 13 | 7.00% | 22 | 11.80% | ||

| Poor (LVEF 21%-30%) | 49 | 7.46% | 7 | 14.30% | 9 | 18.40% | ||

| Very poor (LVEF < 20%) | 10 | 1.52% | 3 | 30.00% | 5 | 50.00% | ||

| Recent MI | 136 | 20.70% | 18 | 13.20% | 0.001 | 27 | 19.90% | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | ||||||||

| No | 263 | 40.03% | 12 | 4.60% | 0.005 | 19 | 7.20% | 0.013 |

| Moderate (PASP 31-55 mmHg) | 245 | 37.29% | 8 | 3.30% | 19 | 7.80% | ||

| Severe (PASP > 55 mmHg) | 149 | 22.68% | 16 | 10.70% | 23 | 15.40% | ||

| Operation-related factors | ||||||||

| Urgency | ||||||||

| Elective | 458 | 69.71% | 12 | 2.60% | < 0.001 | 21 | 4.60% | < 0.001 |

| Urgency | 178 | 27.09% | 18 | 10.10% | 30 | 16.90% | ||

| Emergency | 15 | 2.28% | 4 | 26.70% | 7 | 46.70% | ||

| Salvage | 6 | 0.91% | 2 | 33.30% | 3 | 50.00% | ||

| Weight of the intervention | ||||||||

| Isolated CABG | 255 | 38.81% | 15 | 5.90% | 0.087 | 22 | 8.60% | 0.002 |

| Single non-CABG | 181 | 27.55% | 6 | 3.30% | 10 | 5.50% | ||

| 2 procedures | 174 | 26.48% | 9 | 5.20% | 18 | 10.30% | ||

| 3 procedures | 47 | 7.15% | 6 | 12.80% | 11 | 23.40% |

* M, mortality. # p values mean chi-square test of risk factors compared with the 30-days and in-hospital mortality.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CrCl rate, creatinine clearance rate; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; SD, standard deviation.

The percentages and short-term mortality rates according to the five categories of risk subgroups are shown in Table 2. Among the 657 patients, the 30-day mortality rate ranged from 1.4% to 23.20% by risk level, and the in-hospital mortality rate ranged from 2.10% to 40.20%. The discrimination power was not good in any of the subgroups, as the AUCs were all < 0.75. In the population whose expected mortality was > 4%, the EuroSCORE II model overestimated the 30-day postoperative mortality rate but underestimated the all-cause mortality rate during the same admission period.

Table 2. The EuroSCORE II subgroup compared with the 30-day and in-hospital mortality.

| N | %* | E.M† | 30-day mortality | In-hospital mortality | |||||||

| O.M.‡ | O/E ratio | p value# | AUC | O.M.‡ | O/E | p value | AUC | ||||

| EuroSCORE II | |||||||||||

| 0.00-2.00 | 280 | 42.62% | 1.20% | 1.40% | 1.167 | 0.268 | 0.599 | 2.10% | 1.751 | 0.290 | 0.716 |

| 2.01-4.00 | 138 | 21.00% | 2.85% | 3.60% | 1.263 | 0.316 | 0.394 | 4.30% | 1.509 | 0.401 | 0.473 |

| 4.01-8.00 | 99 | 15.07% | 5.49% | 3.00% | 0.546 | 0.097 | 0.405 | 8.10% | 1.474 | 0.778 | 0.291 |

| 8.01-15.00 | 58 | 8.83% | 10.90% | 8.60% | 0.789 | 0.001 | 0.683 | 13.80% | 1.266 | 0.035 | 0.632 |

| > 15.00 | 82 | 12.48% | 31.32% | 23.20% | 0.741 | 0.347 | 0.631 | 40.20% | 1.284 | 0.540 | 0.660 |

* Percentage of each subgroup. # p values mean the p value of Hosmer-Lemeshow test. † Expected mortality. ‡ Observed mortality.

AUC, area under the curve; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; O/E, observed to expected.

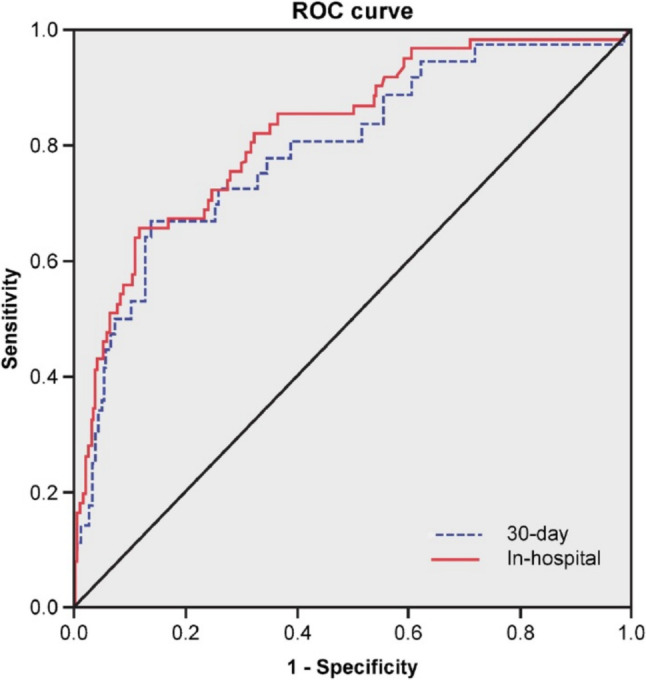

Performance of the EuroSCORE II for 30-day mortality and in-hospital mortality by procedure (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of the 30-day mortality and in-hospital mortality. Note: The 30-day mortality AUC is 0.792 (0.710-0.875), and the in-hospital mortality AUC is 0.825 (0.768-0.882). AUC, area under the curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

The predictive ability (AUC) and calibration of the EuroSCORE II for 30-day mortality according to surgical procedure are shown in Table 3. Of the 657 patients, the overall AUC was 0.792 for CABG and mitral valve replacement (MVR), with individual AUCs of 0.796 and 0.688 for isolated CABG and MVR, respectively. Because none of the patients undergoing AVR died within 30 days, the performance of the EuroSCORE II in AVR could not be evaluated. A high p value of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was shown in all procedure subgroups, including isolated procedures and combined surgery. The ratio of observed to expected mortality to predicted mortality was 0.79 for all included patients, 0.99 for isolated CABG, and 1.01 for isolated MVR surgery.

Table 3. The AUC and O/E ratios of the 30-day and in-hospital mortality by procedures.

| Procedure | N | E.M.* | 30-day mortality | In-hospital mortality | ||||||||

| Death | O.M.# | O/E ratio | p value† | AUC | Death | O.M.# | O/E | p value† | AUC | |||

| CABG and valve surgery | 657 | 6.97% | 36 | 5.48% | 0.79 | 0.573 | 0.792 | 61 | 9.28% | 1.33 | 0.573 | 0.825 |

| Single procedure | ||||||||||||

| Isolated CABG | 242 | 5.83% | 14 | 5.79% | 0.99 | 0.234 | 0.796 | 20 | 8.26% | 1.24 | 0.236 | 0.804 |

| Isolated AVR | 57 | 2.48% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00 | X | X | 1 | 1.75% | 0.71 | 1.000 | 0.982 |

| Isolated MV surgery | 166 | 4.78% | 8 | 4.82% | 1.01 | 0.435 | 0.688 | 12 | 7.23% | 1.51 | 0.470 | 0.748 |

| Combined procedure | 169 | 12.33% | 14 | 8.28% | 0.67 | 0.085 | 0.812 | 26 | 15.38% | 1.25 | 0.189 | 0.808 |

| DVR (AVR + MVR) | 31 | 6.00% | 3 | 9.68% | 1.61 | 0.281 | 0.679 | 3 | 9.68% | 1.61 | 0.281 | 0.679 |

| CABG + MV surgery | 89 | 15.33% | 9 | 10.11% | 0.66 | 0.184 | 0.803 | 19 | 21.35% | 1.39 | 0.213 | 0.744 |

| CABG + AVR | 24 | 9.24% | 1 | 4.17% | 0.45 | 1.000 | 0.957 | 2 | 8.33% | 0.90 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| CABG + AVR + MVR | 13 | 20.15% | 1 | 7.69% | 0.38 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2 | 15.38% | 0.76 | 1.000 | 0.909 |

* Expected mortality. # Observed mortality. † Hosmer-Lemeshow test p value.

AUC, area under the curve; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; DVR, double valve replacement; MV, mitral valve; MVR, mitral valve replacement; O/E, observed to expected.

For in-hospital mortality, the AUC was 0.825 for the entire study population. Good discrimination power of the EuroSCORE II was also shown for a single procedure, with an AUC of 0.804 for CABG, 0.982 for AVR, and 0.748 for isolated MVR surgery. However, the in-hospital mortality rate was underestimated as shown by the O/E ratio (1.33 for all patients, 1.24 for isolated CABG, and 1.51 for MVR surgery).

Logistic regression of the five levels of risk classification of the EuroSCORE II

Logistic regression analysis of the five levels of risk classification, 30-day mortality, and in-hospital mortality is shown in Table 4. In the analysis of postoperative 30-day mortality, the high-risk (8.01-15.00) and very high-risk patients (15.01+) had a significantly higher 30-day mortality rate with an obviously high odds ratio (OR) of 6.509 in the high-risk group and 20.810 in the very high-risk group. The Cox and Snell R2 value was 0.065, and the Nagelkerke R2 value was 0.189. In the analysis of in-hospital mortality, the median risk, high-risk, and very high-risk groups had significantly higher in-hospital mortality rates and ORs. The Cox and Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 values were 0.123 and 0.266, respectively, which were higher in the 30-day mortality group. Higher R2 values indicated better fitting of the model to these data.

Table 4. The EuroSCORE II in predicting the 30-day and in-hospital mortality.

| 30-day mortality | In-hospital mortality | |||||

| OR | 95% CI (lower-upper) | p value | OR | 95% CI (lower-upper) | p value | |

| EuroSCORE II | ||||||

| < 2 (ref) | ||||||

| 2.01-4.00 | 2.594 | (0.69-9.82) | 0.160 | 2.076 | (0.66-6.56) | 0.213 |

| 4.01-8.00 | 2.156 | (0.47-9.81) | 0.320 | 4.015 | (1.36-11.88) | 0.012 |

| 8.01-15.00 | 6.509 | (1.69-25.04) | 0.006 | 7.307 | (2.43-21.96) | < 0.001 |

| > 15.01 | 20.810 | (6.84-63.30) | < 0.001 | 30.755 | (12.24-77.29) | < 0.001 |

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.065 | 0.123 | ||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.189 | 0.266 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; ref, reference.

DISCUSSION

Despite differences in demographic characteristics, a universal scoring system is useful for both cardiac surgeons and patients. Since the EuroSCORE was introduced in the 1990s, it has become a popular risk stratification tool worldwide.4,13-15

In this 3-year study from a single public cardiac surgery unit in the southern region of Taiwan, the updated EuroSCORE II showed good accuracy in predicting both 30-day mortality and in-hospital mortality. There were no significant differences between the observed and estimated mortality rates in single or combined cardiac procedures. Guida et al.16 conducted a systematic review of English articles about the performance of the EuroSCORE II, and reported an AUC of 0.792 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.773-0.811] and an estimated O/E ratio of 1.019 (95% CI: 0.899-1.139). These results showed good overall prediction of operation mortality with the updated model.

Several studies have been conducted on CABG and the predictive power of the EuroSCORE II. Biancari et al.17 studied 1027 patients who underwent isolated CABG, and reported that the EuroSCORE II performed somewhat better than the original logistic EuroSCORE and its Finnish modified version in predicting operation mortality. However, Borracci et al.18 reported that both the discrimination and calibration of the EuroSCORE II and in-hospital mortality were worse than those of non-CABG subgroups. Nezic et al.19 reported that the O/E mortality ratio confirmed good calibration for the entire cohort with the EuroSCORE II (1.05, 95% CI: 0.81-1.29). In a study by Chalmers et al.20,21 conducted at a single center with more than 5000 patients, compared with the EuroSCORE model, the EuroSCORE II was a better model for combined valve and CABG, and the best for isolated mitral surgery, but that it had a poor predictive ability for isolated CABG. In our study, the accuracy and calibration of the EuroSCORE II in the CABG subgroups were good, with no differences in predicting 30-day and in-hospital mortality.

Isolated AVR and transcatheter aortic valve implantation for aortic stenosis have become popular issues in the last decade. However, a good risk stratification tool before surgical decision-making is still not available for either procedure. Silaschi et al.22 analyzed five logistic scoring systems (EuroSCORE, EuroSCORE II, STS, Ambler, and Parsonnet scores) in 457 patients, and found that none of the risk evaluation systems was acceptable. Moreover, they found that EuroSCORE II underestimated operative mortality in high-risk patients, and that the STS score overestimated operative mortality in low-risk patients.23 In our study, although good discrimination power (AUC = 0.982) was found for the EuroSCORE II in the isolated AVR subgroup, an underestimation of in-hospital mortality was observed with an O/E ratio of 0.71. As there were no surgical deaths within the first month, the performance of isolated AVR could not be evaluated for 30-day mortality. A specific model for the evaluation of isolated AVR remains unavailable.

According to hospital discharge policy, in-hospital mortality seems to be a more meaningful outcome index representing surgical quality based on patients’ opinions compared to 30-day mortality. Osswald et al.24 suggested that 30-day mortality systematically underestimated early risk, at least in the CABG group, and they recommended a standardized evaluation with a longer time period. In our study, the O/E ratio and AUC revealed that the EuroSCORE II could predict both 30-day and in-hospital mortality of major cardiac procedures quite well. However, accuracy for in-hospital mortality still seemed to be better with a higher AUC for all subgroups, although the EuroSCORE II seemed to underestimate in-hospital mortality. Table 4 shows the logistic regression analysis of comparisons between 30-day and in-hospital mortality by the five risk subgroups of the EuroSCORE II. Table 5 shows the risk factors of EuroSCORE II in predicting 30-day and in-hospital mortality. A higher EuroSCORE II indicated a higher surgical mortality rate in all populations in this study, with a significant increase in the OR in the high-risk populations (EuroSCORE II: 8.01-15.00 and > 15.01). Furthermore, in-hospital mortality represented a better endpoint than 30-day mortality for the EuroSCORE II, with an obviously higher R2 value (0.266 vs. 0.189, 0.123 vs. 0.065).

Table 5. Risk factors in predicting the 30-day and in-hospital mortality.

| Factors | 30-day mortality | In-hospital mortality | ||||

| OR | 95% CI (Lower-Upper) | p value | OR | 95% CI (Lower-Upper) | p value | |

| Patient-related factors | ||||||

| Sex (female ref) | 1.067 | (0.442-2.573) | 0.885 | 0.924 | (0.455-1.876) | 0.827 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| < 50 (ref) | ||||||

| 51-70 | 0.790 | (0.189-3.294) | 0.746 | 1.390 | (0.355-5.433) | 0.636 |

| 71-80 | 1.356 | (0.294-6.258) | 0.696 | 3.864 | (0.934-15.996) | 0.062 |

| > 80 | 4.625 | (0.919-23.285) | 0.063 | 5.523 | (1.194-25.550) | 0.029 |

| Renal dysfunction | ||||||

| Mild (CrCl ratio > 85) (ref) | ||||||

| Moderate (CrCl ratio 51-85) | 1.610 | (0.272-9.517) | 0.600 | 0.895 | (0.237-3.387) | 0.870 |

| Severe (CrCl ratio < 50) | 4.054 | (0.744-22.081) | 0.106 | 2.508 | (0.704-8.941) | 0.156 |

| Dialysis (regardless of CrCl ratio) | 2.324 | (0.252-21.445) | 0.457 | 0.979 | (0.170-5.643) | 0.981 |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | 0.603 | (0.165-2.205) | 0.445 | 0.945 | (0.378-2.363) | 0.904 |

| Poor mobility | 2.215 | (0.534-9.191) | 0.273 | 2.489 | (0.851-7.283) | 0.096 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 6.279 | (1.526-25.830) | 0.011 | 4.855 | (1.418-16.622) | 0.012 |

| Chronic lung disease | 0.980 | (0.188-5.099) | 0.981 | 0.940 | (0.236-3.748) | 0.931 |

| Infective endocarditis | 1.390 | (0.104-18.488) | 0.803 | 1.886 | (0.303-11.759) | 0.497 |

| Critical preoperative status | 0.575 | (0.176-1.879) | 0.360 | 1.327 | (0.525-3.354) | 0.550 |

| Diabetes on insulin | 1.987 | (0.703-5.615) | 0.195 | 2.548 | (1.086-5.976) | 0.032 |

| Cardiac-related factors | ||||||

| NYHA | ||||||

| Class I (ref) | ||||||

| Class II | 1.022 | (0.298-3.503) | 0.972 | 2.564 | (0.832-7.901) | 0.101 |

| Class III | 0.951 | (0.224-4.044) | 0.946 | 2.033 | (0.572-7.229) | 0.273 |

| Class IV | 2.016 | (0.333-12.221) | 0.446 | 9.219 | (1.918-44.312) | 0.006 |

| CCS class 4 angina | 1.371 | (0.454-4.140) | 0.576 | 0.894 | (0.335-2.386) | 0.824 |

| LV function | ||||||

| Mild (LVEF > 50%) (ref) | ||||||

| Moderate (LVEF 31%-50%) | 1.066 | (0.385-2.950) | 0.902 | 0.864 | (0.386-1.931) | 0.722 |

| Poor(LVEF 21%-30%) | 2.500 | (0.617-10.127) | 0.199 | 0.991 | (0.290-3.390) | 0.989 |

| Very poor (LVEF < 20%) | 4.349 | (0.552-34.273) | 0.163 | 2.970 | (0.492-17.937) | 0.235 |

| Recent MI | 2.768 | (0.951-8.053) | 0.062 | 1.327 | (0.552-3.189) | 0.527 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | ||||||

| No (PASP < 30 mmHg) (ref) | ||||||

| Moderate (PASP 31-55 mmHg) | 0.657 | (0.206-2.097) | 0.478 | 0.876 | (0.359-2.138) | 0.772 |

| Severe (PASP > 55 mmHg) | 2.777 | (0.880-8.758) | 0.081 | 1.783 | (0.710-4.478) | 0.218 |

| Operation-related factors | ||||||

| Urgency | ||||||

| Elective (ref) | ||||||

| Urgency | 1.933 | (0.691-5.409) | 0.209 | 1.920 | (0.822-4.485) | 0.132 |

| Emergency | 2.86 | (0.462-17.702) | 0.259 | 3.688 | (0.761-17.874) | 0.105 |

| Salvage | 1.722 | (0.107-27.642) | 0.701 | 2.971 | (0.217-40.599) | 0.414 |

| Weight of the intervention | ||||||

| Isolated CABG (ref) | ||||||

| Single non-CABG | 0.873 | (0.216-3.517) | 0.848 | 0.887 | (0.295-2.668) | 0.831 |

| 2 Procedures | 0.664 | (0.211-2.096) | 0.485 | 0.890 | (0.356-2.224) | 0.803 |

| 3 Procedures | 1.103 | (0.278-.381) | 0.889 | 1.698 | (0.547-5.263) | 0.359 |

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.105 | 0.166 | ||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.302 | 0.360 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCr, creatinine clearance rate; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CI, confidence interval; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OR, odds ratio; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; ref, reference.

Use of the EuroSCORE II in high-risk patients is another interesting issue, as the old model was widely criticized over this issue. The performance of the new EuroSCORE II model was studied by Howell et al.25 in two different European countries; however, the EuroSCORE II did not improve risk prediction in high-risk patients undergoing adult cardiac surgery when compared with the old additive and logistic EuroSCOREs. The limitation of this study is the retrospective collection of new variables that are not included in the EuroSCORE. Therefore, some patients may be misclassified as having a risk factor, and the EuroSCORE II may be slightly different.25 Although age is considered to be a predictor of mortality in certain high-risk surgeries, none of the existing EuroSCORE models include aortic calcification and diffuse coronary artery disease, which are important when determining mortality, especially in patients older than 70 years.20

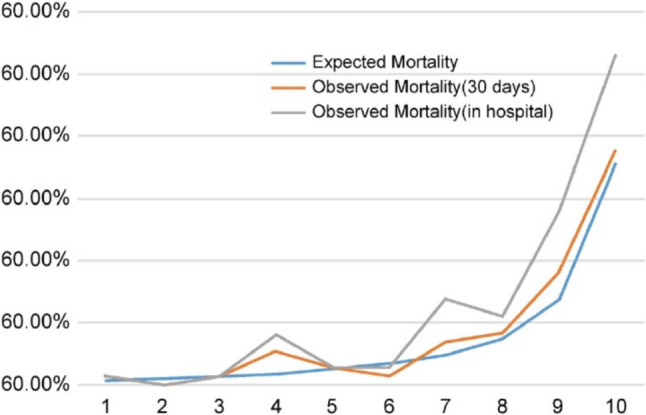

In our study population, the patients with a higher EuroSCORE II (EuroSCORE II < 4.00%) had a lower than predicted 30-day mortality rate after primary cardiac surgeries, but the surgical death rate remained higher than that predicted death rate by the EuroSCORE II model during the same admission (Figure 2). The limitation of our study population is the low number of AVR cases. However, the EuroSCORE II is still an acceptable tool for evaluating short-term surgical outcomes, especially in-hospital death, which may be a more appropriate marker for disease treatment.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the EuroSCORE II expected mortality rate with the 30-day and in-hospital mortality rates. EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation. X-axis: The score was divided into 1 to 10 groups based on the EuroSCORE II model; Y-axis: Mortality rate.

CONCLUSIONS

The new EuroSCORE II model performed well in predicting the short-term outcomes of all patients who underwent cardiac surgery at our hospital in Taiwan. This modern risk evaluation tool was accurate for patients undergoing cardiac procedures related to CABG, but it was not suitable for single or combined valve procedures. For short-term outcomes, in-hospital mortality was better than 30-day mortality as an indicator of surgical results, suggesting that it may be a better endpoint for the EuroSCORE II.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to the Department of Medical Education and Research and the Research Center of Medical Informatics in Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital for inquiries and assistance in data processing.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roques F, Nashef SA, Michel P, et al. Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the EuroSCORE multinational database of 19030 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:816–822; discussion 822-3. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roques F, Nashef SA, Michel P, et al. Does EuroSCORE work in individual European countries? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;18:27–30. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00417-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawachi Y, Nakashima A, Toshima Y, et al. Risk stratification analysis of operative mortality in heart and thoracic aorta surgery: comparison between Parsonnet and EuroSCORE additive model. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:961–966. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nashef SA, Roques F, Hammill BG, et al. Validation of European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE) in North American cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:101–105. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih HH, Kang PL, Pan JY, et al. Performance of European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation in Veterans General Hospital Kaohsiung cardiac surgery. J Chin Med Assoc. 2011;74:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CC, Wang CC, Hsieh SR, et al. Application of European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE) in coronary artery bypass surgery for Taiwanese. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2004;3:562–565. doi: 10.1016/j.icvts.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:734–744; discussion 744-5. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant SW, Hickey GL, Dimarakis I, et al. How does EuroSCORE II perform in UK cardiac surgery; an analysis of 23,740 patients from the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland National Database. Heart. 2012;98:1568–1572. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paparella D, Guida P, Di Eusanio G, et al. Risk stratification for in-hospital mortality after cardiac surgery: external validation of EuroSCORE II in a prospective regional registry. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:840–848. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osnabrugge RL, Speir AM, Head SJ, et al. Performance of EuroSCORE II in a large US database: implications for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:400–408; discussion 408. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983;148:839–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW., Jr. A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115:92–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asimakopoulos G, Al-Ruzzeh S, Ambler G, et al. An evaluation of existing risk stratification models as a tool for comparison of surgical performances for coronary artery bypass grafting between institutions. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:935–941; discussion 941-2. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yap CH, Reid C, Yii M, et al. Validation of the EuroSCORE model in Australia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:441–446; discussion 446. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tjang YS, van Hees Y, et al. Predictors of mortality after aortic valve replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:469–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guida P, Mastro F, Scrascia G, et al. Performance of the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II: a meta-analysis of 22 studies involving 145,592 cardiac surgery procedures. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:3049–3057 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biancari F, Vasques F, Mikkola R, et al. Validation of EuroSCORE II in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1930–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borracci RA, Rubio M, Celano L, et al. Prospective validation of EuroSCORE II in patients undergoing cardiac surgery in Argentinean centres. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18:539–543. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nezic D, Spasic T, Micovic S, et al. Consecutive observaional study to validate EuroSCORE II performances on a single-center, contemporary cardiac surgical cohort. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30:345–351. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramani S. The current status of EuroSCORE II in predicting operative mortality following cardiac surgery. Ann Card Anaesth. 2020;23:256–257. doi: 10.4103/aca.ACA_32_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalmers J, Pullan M, Fabri B, et al. Validation of EuroSCORE II in a modern cohort of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:688–694. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silaschi M, Conradi L, Seiffert M, et al. Predicting risk in transcatheter aortic valve implantation: comparative analysis of EuroSCORE II and established risk stratification tools. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;63:472–478. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1389107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuwaki K, Inaba H, Yamamoto T, et al. Performance of the EuroSCORE II and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Score in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2015;56:455–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osswald BR, Blackstone EH, Tochtermann U, et al. The meaning of early mortality after CABG. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell NJ, Head SJ, Freemantle N, et al. The new EuroSCORE II does not improve prediction of mortality in high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a collaborative analysis of two European centres. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44:1006–1011; discussion 1011. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]