Abstract

Background:

Favorable prognosis for Human papillomavirus-associated (HPV+) oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) led to investigation of response-adaptive de-escalation, yet long-term outcomes are unknown. We present expanded experience and follow-up of risk/response adaptive treatment de-intensification in HPV+ OPC.

Methods:

A phase 2 trial (OPTIMA) and subsequent cohort of sequential off-protocol patients treated from September 2014 to November 2018 at the University of Chicago were reviewed. Eligible patients had T3-T4 or N2–3 (AJCC 7th edition) HPV+ OPC. Patients were stratified by risk: High-risk (HR) (T4, ≥N2c, or >10PYH), all others low-risk (LR). Induction chemotherapy (IC) included 3 cycles of carboplatin and nab-paclitaxel (OPTIMA) or paclitaxel (off-protocol). LR with ≥50% response received low-dose radiotherapy (RT) alone to 50 Gy (RT50). LR with 30–50% response and HR with ≥50% response received intermediate-dose chemoradiotherapy (CRT) to 45Gy (CRT45). All others received full-dose CRT to 75Gy (CRT75).

Results:

91 patients consented and 90 patients were treated, of which 31% had >10PYH, 34% had T3/4 disease, and 94% had N2b/N2c/N3 disease. 49% were LR and 51% were HR. Overall response rate to induction was 88%. De-escalated treatment was administered to 83%. Median follow-up was 4.2 years. Five-year OS, PFS, LRC, and DC were 90% (95% CI 81,95), 90% (95% CI 80,95), 96% (95% CI 90,99), and 96% (88,99) respectively. G-tube placement rates in RT50, CRT45, and CRT75 were 3%, 33%, and 80% respectively (p<0.05).

Conclusion:

Risk/response adaptive de-escalated treatment for an inclusive cohort of HPV+ OPC demonstrates excellent survival with reduced toxicity with long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, human papillomavirus, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, treatment de-intensification

Introduction

Oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) incidence rates have been rising rapidly over the past several decades in the United States and Europe, attributable to infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV)[1, 2]. HPV associated (HPV+) OPC is associated with a favorable prognosis, however standard multimodality treatment is associated with substantial morbidity[1, 3, 4]. This has led to interest in development of a treatment de-escalation strategy that optimizes oncologic control while minimizing acute and long-term treatment related toxicity[5]. A good response to induction chemotherapy predicts a favorable prognosis with reduced risk of locoregional and distant recurrence[6]. As such, response to induction therapy has been proposed as a strategy to select patients with HPV+ OPC for treatment de-escalation and has demonstrated favorable survival outcomes and toxicity[7–11]. In the E1308 trial, patients with a clinical complete response to induction at the primary site received radiotherapy dose reduction to 54 Gy, while other patients received a dose of 69.3 Gy[7]. At the University of Chicago, our group has explored response adapted volume de-escalation (RAVD) in which patients with a deep response to induction chemotherapy (≥50% tumor shrinkage per RECIST) were treated with a reduced radiotherapy field that eliminated elective nodal coverage[9]. These results led to development of an institutional de-escalation paradigm of induction therapy followed by risk and response stratified de-escalated (chemo)radiotherapy (OPTIMA paradigm), demonstrating excellent oncologic control with improved functional outcomes in patients who received de-escalated chemoradiotherapy (CRT)[10, 11]. The encouraging results of the OPTIMA trial led to further treatment of patients off-protocol using the same paradigm treated sequentially at the University of Chicago after completion of the OPTIMA clinical trial. Herein, the updated results and expanded experience of patients with locoregional HPV+ OPC treated with induction chemotherapy followed by risk and response stratified de-escalated chemoradiotherapy are presented with longer-term follow-up.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility

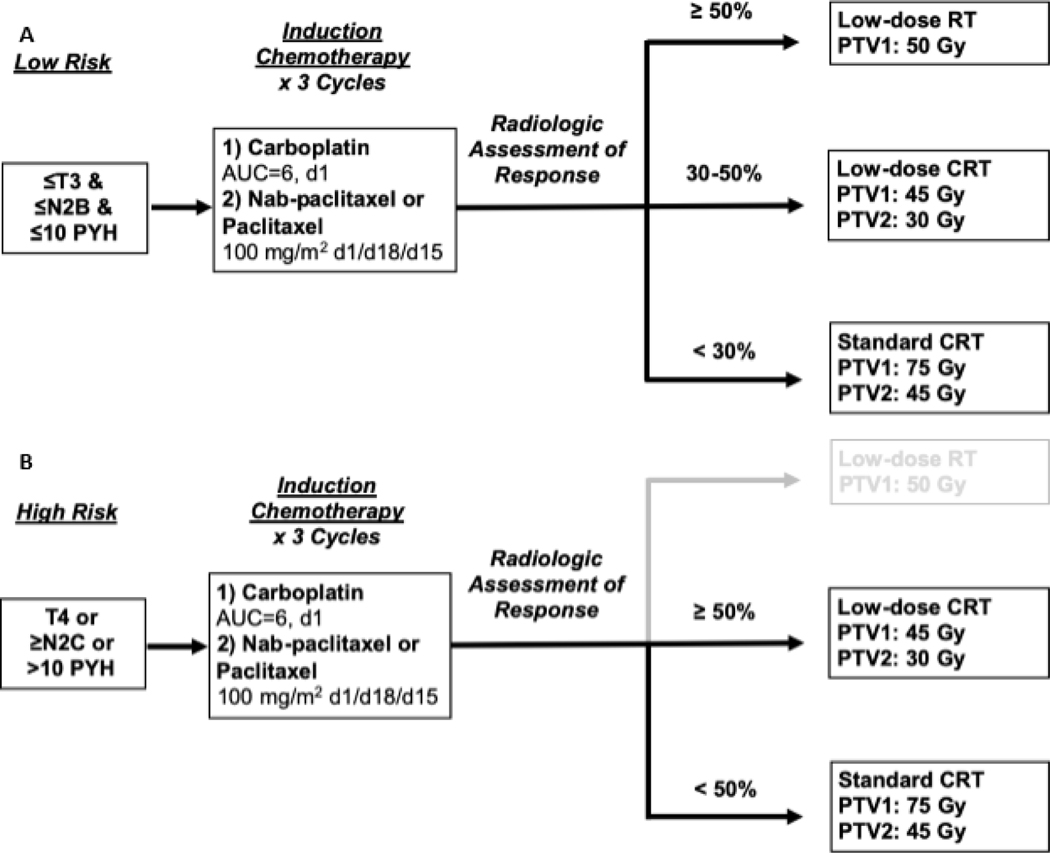

We conducted a retrospective review of patients with locoregional p16+ OPC treated at the University of Chicago with the OPTIMA paradigm, a response incorporated definitive treatment, from September 2014 to November 2018. The OPTIMA trial was a single arm, phase II trial of induction chemotherapy followed by risk and response stratified de-escalated (chemo)radiotherapy that has been described previously (NCT02258659)(Figure 1)[10]. A subsequent cohort of sequentially treated patients off-protocol according to the OPTIMA trial with identical monitoring and evaluation procedures was retrospectively evaluated (Figure 2). This retrospective study was approved by the University of Chicago institutional review board.

Figure 1:

OPTIMA paradigm treatment schema for (A) low risk and (B) high risk.

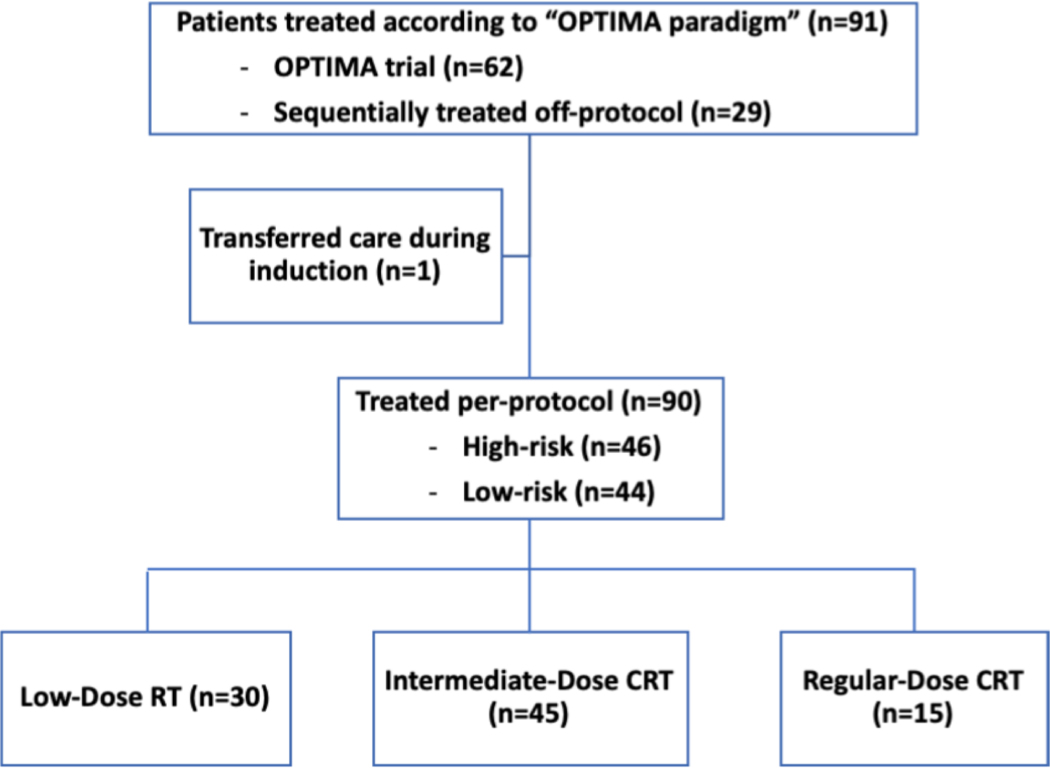

Figure 2:

Consort diagram with flow of patients treated per OPTIMA paradigm.

Study Treatment:

Prior to initiating treatment, patients were classified as either low-risk or high-risk. AJCC 7th edition staging was utilized. Low-risk patients had stage T3N0 or T1–3N2a/b, and cumulative smoking history of ≤10 pack-years (PY). High-risk patients had any one of the following high-risk features: Tumor stage T4, nodal stage N2c/3, or >10PY history. Patients received treatment with 3 cycles of induction chemotherapy which consisted of three cycles of carboplatin AUC 6 on day 1 and nab-paclitaxel (OPTIMA trial) or paclitaxel (off-protocol treated) 100mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 21-day cycle. Following induction therapy, all patients received dedicated anatomic neck imaging with either CT or MRI. Percent tumor shrinkage was determined using RECIST v1.1[12]. Subsequently, patients were stratified into one of three treatment arms. Patients who were low-risk and ≥50% response were treated on the low-dose radiotherapy-alone arm (RT50) and received 50 Gy in 25 daily fractions over 5 weeks without concurrent chemotherapy to initially involved gross disease plus margin. Patients who were low-risk with 30–50% response or high-risk with ≥50% response received intermediate-dose chemoradiotherapy (CRT45) to 45 Gy to initially involved gross disease plus margin and 30 Gy to a reduced elective nodal volume based on the primary site, with three cycles of TFHX (14-day cycle of paclitaxel 100mg/m2 on day 1, 5-fluorouracil continuous infusion 600mg/m2/day on days 0–5, and hydroxyurea 500mg twice daily on days 0–5 for total of 11 doses, with twice daily radiotherapy in 1.5 Gy fractions on days 1–5 and no treatment on days 6–13). Patients who were high-risk with <50% response received regular dose chemoradiotherapy (CRT75) with five cycles of TFHX for a total of 75 Gy to gross disease and 45 Gy to a reduced elective volume(Figure 1).

Patients who were enrolled on the OPTIMA trial underwent surgical evaluation with a selected neck dissection and/or biopsy of primary site as deemed appropriate by the treating surgeon. Off-protocol treated patients underwent either surgical evaluation as described above or PET scan at 12 weeks following completion of (chemo)radiotherapy. Patients underwent clinical and radiographic disease assessment every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for years 2–3, and annually during years 4 and 5.

Endpoints:

Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of enrollment until death from any cause. Surviving patients were censored as of the last known follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from time of enrollment until disease progression or death from any cause. Surviving patients without disease progression were censored as of the last negative evaluation. Time to locoregional failure was calculated as the time from enrollment until the development of locoregional recurrence as documented by pathologic documentation of recurrent disease. Time to distant failure was calculated as the time from enrollment until the development of distant metastasis by biopsy. For both time to locoregional and distant failure, patients were censored as of the last negative exam. Overall response rate (ORR) following induction is defined as the percentage of patients who had ≥ 30% tumor shrinkage. Deep response rate (DRR) was defined as the percentage of patients who had ≥ 50% tumor shrinkage. Percent tumor shrinkage was assessed per RECIST 1.1. Rates and duration of enteral feeding tube placement were calculated from data of tube placement and removal.

Statistical Analysis:

Summary statistics for baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Univariate Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed for the following survival outcomes: progression free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), locoregional control (LC) and distant control (DC) by treatment arm, risk group, and all subjects. Log-rank tests for survival differences between risk group and treatment arms and 5-year confidence intervals were also estimated. In addition, multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was performed with smoker, age, t-stage, n-stage, and ECOG score for OS outcomes. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4).

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | N=90 |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 63.0 (34–83) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 87 (97) |

| Female | 3 (3) |

| Tobacco hx, n (%) | |

| Never smoker | 39 (43) |

| <10 PY | 23 (26) |

| >10 PY | 28 (31) |

| Primary site, n (%) | |

| BOT | 48 (53) |

| Tonsil | 40 (44) |

| Soft palate | 1 (1) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) |

| Stage T, n (%) | |

| 1 | 19 (21) |

| 2 | 40 (44) |

| 3 | 20 (22) |

| 4 | 11 (12) |

| Stage N, n (%) | |

| 0 | 3 (3) |

| 1 | 2 (2) |

| 2a | 5 (6) |

| 2b | 63 (70) |

| 2c | 15 (17) |

| 3 | 2 (2) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 76 (84) |

| 1 | 12 (13) |

| 2 | 2 (2) |

| P16 status, n (%) | |

| Positive | 90 (100) |

| HPV subtype, n (%) | |

| Not performed | 30 (33) |

| Performed | 60 (67) |

| HPV16 | 54 (88) |

| HPV33 | 3 (5) |

| HPV DNA not detected | 3 (5) |

| Risk category, n (%) | |

| Low | 44 (49) |

| High | 46 (51) |

Results

Patient Characteristics:

From September 2014 to November 2018, 91 patients with locoregionally advanced p16+ OPC started treatment per the OPTIMA paradigm. Sixty-two patients were treated on the OPTIMA trial and twenty-nine patients were subsequently treated off-protocol (see Figure 2). One patient from the OPTIMA trial transferred care during induction and is not included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients were previous smokers (57%) and 31% had greater than 10 pack-year smoking history. Tumor stage T3/T4 was noted in 34% of patients, and a majority of patients (89%) had N2b/N2c/N3 nodal stage.

Efficacy:

The median follow-up for all patients was 4.2 years. Assessment of response following induction chemotherapy demonstrated an ORR and DRR of 88% and 68% respectively. De-escalated (C)RT was administered in 83% of patients, of which 33% were treated with RT50 and 50% were treated with CRT45 (see Figure 2). Median tumoral response per RECIST 1.1[12] for nab-paclitaxel and paclitaxel-treated patients were 60% and 61% respectively.

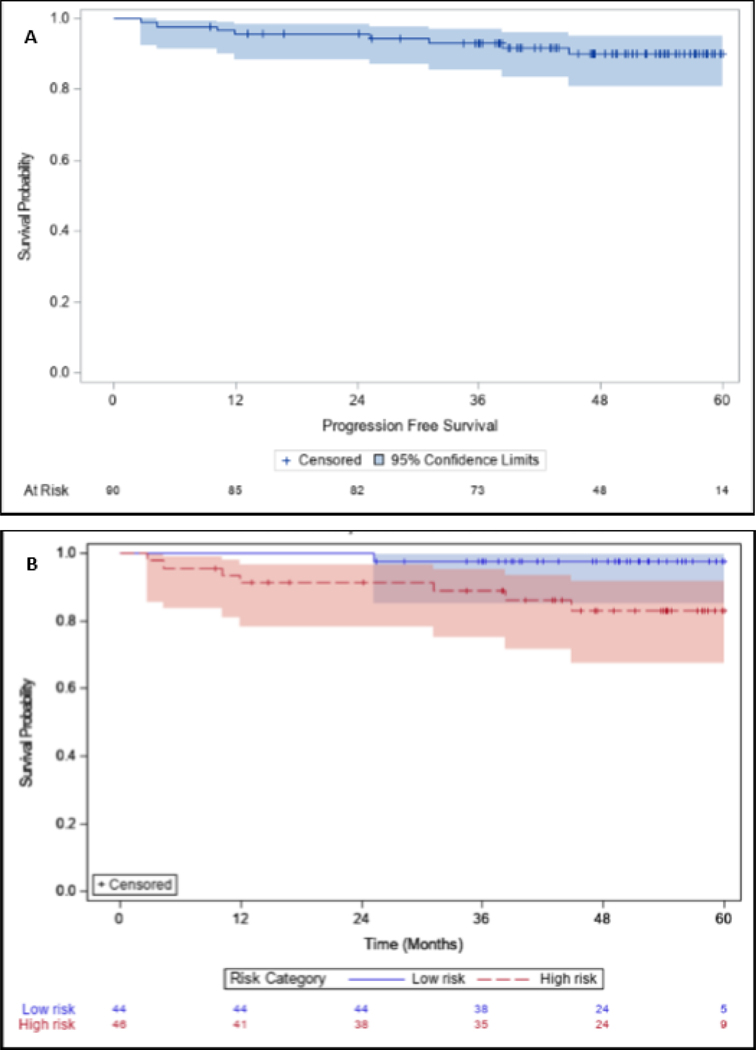

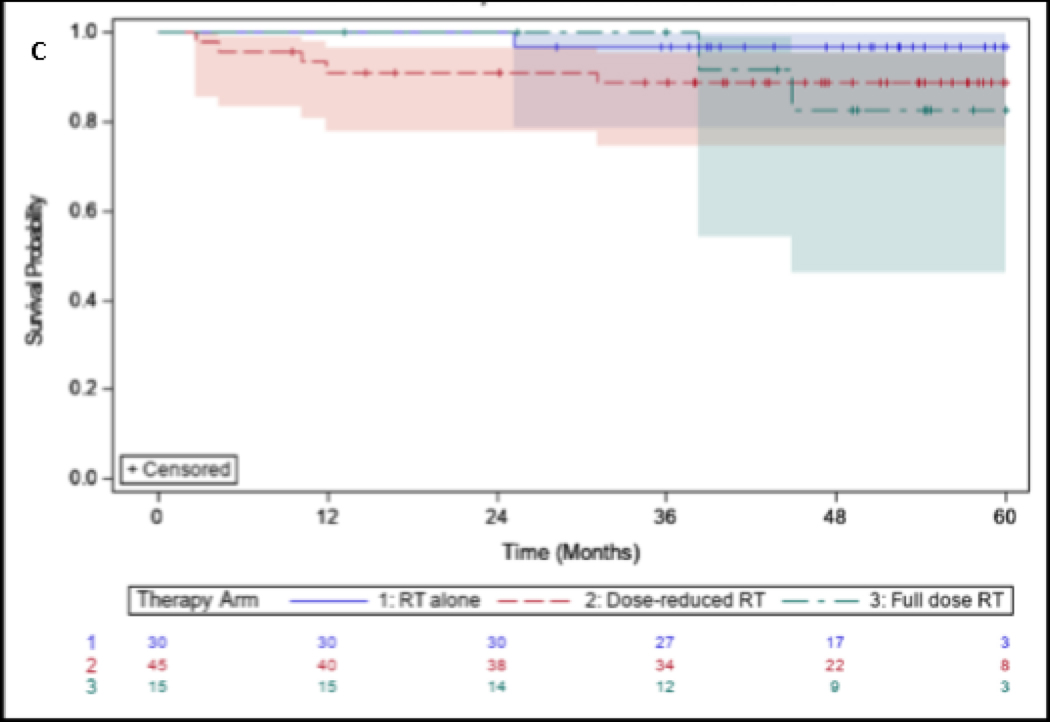

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS and PFS for the entire cohort, stratified by risk categories and treatment arms, can be observed in Figures 3–4. The 5-year OS and PFS for the entire cohort was 90% (95% CI 80,95) and 90% (95% CI 81,95), respectively. For low-risk and high-risk patients, 5-year OS was 98% (95% CI 85,100) and 82% (95% CI 66,91), respectively. There was a statistically significant difference for OS between low-risk and high-risk cohorts (p=0.03). 5-year LRC and DC were 96% and 96% respectively.

Figure 3:

Overall survival for (A) All patients treated, (B) Stratified by high risk and low risk patients, and (C) Stratified by treatment group with RT50, CRT45, or CRT75.

Figure 4:

Progression free survival for (A) All patients treated, (B) Stratified by high risk and low risk patients, and (C) Stratified by treatment group with RT50, CRT45, or CRT75.

The results of Cox regression analysis for OS are shown in Table 2. While none of the predictors were significant, history of smoking, Tumor (T) stage (T4 vs. <T4), Nodal (N) stage (N2c/N3 vs. ≤ N2b), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (1 or 2 vs. 0) demonstrated hazard ratios > 2, albeit was not statistically significant.

Table 2:

Cox regression analysis for OS

| Covariate | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 | 0.91,1.07 | 0.81 |

| Tobacco use (history of smoking vs. never smokers) | 2.25 | 0.41,12.30 | 0.35 |

| T-stage (T4 vs. <T4) | 2.88 | 0.54,15.38 | 0.22 |

| N-stage (N2c/3 vs. <N2c) | 2.01 | 0.45,8.88 | 0.36 |

| ECOG PS (1 or 2 vs. 0) | 2.07 | 0.40,10.72 | 0.39 |

Treatment failures:

Three out of ninety patients (3%) developed recurrent disease during the study. One patient was high-risk due to N3 nodal disease with a deep response to induction and treated with CRT45, developed locoregional recurrence 5 months following completion of CRT and underwent a salvage neck dissection but subsequently died of progressive disease. One low-risk patient with a deep response to induction and treated with RT50 developed distant failure with widespread metastases 22 months after completion of RT and died of disease. One patient was high-risk with a deep response to induction and treated with CRT45 and developed locoregional recurrence eight months following completion of CRT followed by salvage neck dissection and re-irradiation, but subsequently failed distantly and died.

Toxicity and feeding-tube rates:

During induction chemotherapy, the rate of grade 3 neutropenia was 40%, and granulocyte-colony stimulating factory (G-CSF) was administered in all patients. Grade 1 or greater peripheral sensory neuropathy developed at some point during treatment in 56% of patients overall, and in 54% and 59% of patients among nab-paclitaxel and paclitaxel treated patients respectively. Two patients died of treatment-related toxicity, both due to sepsis during chemoradiation. There were additional three patients that died without recurrent disease years following completion of treatment. Of these, one patient died of an acute myocardial infarction 2.8 years following completion of CRT, and two patients who were treated with CRT75 died of pneumonia and colitis 2.7 and 4.4 years, respectively, following completion of CRT.

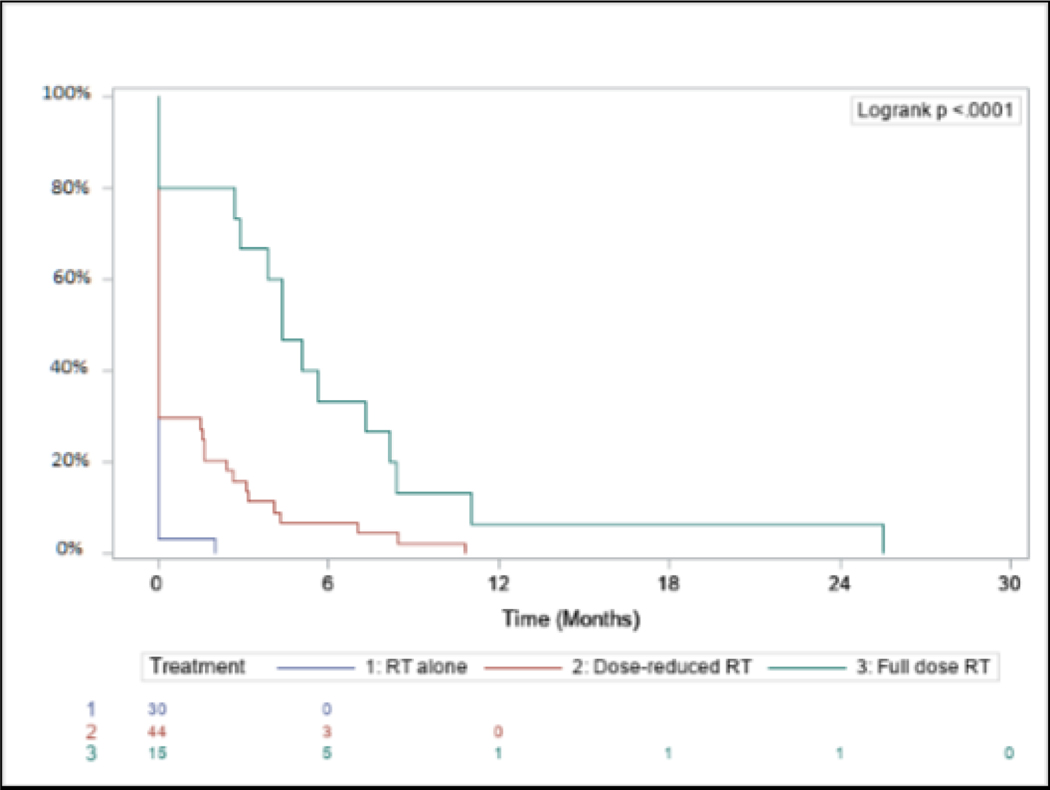

Enteral feeding dependency was observed in 31% overall at some point during the treatment course. Feeding tube dependency rates for RT50, CRT45, and CRT75 were 3%, 33%, and 80%, respectively (p<0.0001). All surviving patients who were feeding-tube dependent ultimately underwent removal and became independent from enteral feeding. Enteral feeding dependency for each arm from the end of CRT can be observed in Figure 5.

Figure 5:

Enteral feeding dependency from the end of (chemo)radiation by treatment arm.

Discussion

The expanded experience and long-term follow-up of our OPTIMA de-escalation paradigm for locoregionally advanced HPV+ OPC of risk and response adaptive (C)RT indicates this to be a feasible treatment strategy with encouraging results. The 5-year OS and PFS of 90% and 90% respectively was noted with de-escalated (C)RT administered to 83% of patients, with significantly lower enteral feeding dependency in de-escalated cohorts. These long-term outcomes expound upon our previous institutional reports[9–11].

Treatment de-intensification efforts in HPV-associated OPC include replacing or omitting cytotoxic chemotherapy, surgical resection with de-intensified adjuvant therapy, and response-adaptive de-intensification following induction chemotherapy. Attempts to de-escalate by replacing concurrent cisplatin with cetuximab have demonstrated worse OS, and no difference in overall severe toxicity[13, 14]. The RTOG 1016 study reported 5-year OS of 84.6% in the cisplatin arm versus 77.9% in the cetuximab arm[14]. Mehanna and colleagues reported 2-year OS of 97.5% in the cisplatin arm versus 89.4% in the cetuximab arm[13], however this trial was restricted to low-risk HPV+ OPC with <10PY smoking history in contrast to our study which includes high-risk HPV+ disease. The ARTSCAN III study which randomized patients with locoregional HNSCC to weekly cetuximab or weekly cisplatin concurrent with definitive RT, reported 3-year OS of 77% and 88% respectively[15]. The TROG 12.01 study randomized patients with HPV+ OPC to definitive radiation with weekly cisplatin or cetuximab demonstrating 3-year failure free survival rates of 93% and 80% respectively, p=0.015[16]. Recently, the NRG-HN002 study in which low-risk HPV+ OPC patients were randomized to 60Gy over 6 weeks with concurrent cisplatin or 60Gy over 5-weeks alone, reported 2-year PFS of 90.5% and 87.6% respectively[17]. De-escalated adjuvant (C)RT following transoral resection was evaluated in the ECOG 3311 study, suggesting that de-escalated adjuvant radiotherapy to 50 Gy without chemotherapy may be sufficient for intermediate pathologic risk with 2-year PFS of 95.0%, although this strategy has yet to be compared to non-surgical therapy in a randomized setting[18]. Response adapted locoregional therapy following induction was evaluated in the ECOG 1308 study that reported a 2-year PFS and OS of 78% and 91% respectively[7]. Chen and colleagues evaluated a strategy of induction carboplatin and paclitaxel followed by de-escalated CRT with paclitaxel to 54 Gy in patients who had a PR or CR and reported a 2-year PFS of 92%[8]. In another trial, Chera and colleagues have reported results of their de-escalated definitive CRT platform of weekly cisplatin 30mg/m2 and RT to 60 Gy, with 3-year OS of 95% and 2-year PFS of 88%. Our 5-year OS and PFS of 90% reflects longer follow-up and compares favorably with these results. Notably, these studies excluded high-risk HPV+ OPC[19, 20] in contrast to our OPTIMA paradigm cohort that included a significant number of high-risk patients, including T4, N2c/N3 nodal disease, and significant smoking history. The ICON-S study identified the prognostic significance of either T4 tumor stage or N3 nodal stage, which have subsequently been categorized as stage III in the AJCC 8th edition staging system.[21]

The cohort of patients treated with RT50 demonstrated excellent long-term survival with both 5-year OS and PFS of 97%. This subset of patients with low-risk disease (<T4, ≤N2b, <10PY smoking history) and favorable response to induction chemotherapy has excellent outcomes with our de-escalation strategy. While high-risk patients had significantly worse 5-year OS of 82% compared with low-risk patients, the outcome was comparable to a historical control of full dose CRT with concurrent cisplatin from RTOG 1016 of 84.6%. Of the three patients who developed recurrent disease, two had high risk disease with deep response to induction chemotherapy and were subsequently treated with de-escalated CRT45. While definitive conclusions are limited in light of small numbers of treatment failures in this study, this could indicate a cohort that may benefit from improved biomarkers for treatment de-escalation beyond tumor shrinkage per RECIST criteria. Alternative selective biomarkers such as quantitative HPV ctDNA, genomic or radiomic biomarkers, may be helpful with patient selection in this setting, and are currently under investigation (NCT04572100). Importantly, the elimination of elective volume in low risk responders nor the reduction in dose to elective nodal volume in high risk responders seemed to result in marginal or neck failures.

With longer follow-up, there were two patients who experienced late deaths from myocardial infarction (treated with CRT45) and pneumonia (treated with CRT75), 2.8 and 4.4 years following CRT respectively. Interestingly, 7/8 deaths (88%) were previous smokers, with 6/8 (75%) having over 10 pack year smoking history. While not statistically significant, this finding suggests a negative prognostic impact of cumulative tobacco use in the context of our de-escalation paradigm which aligns with previous reports.[7, 21, 22] It is also notable that late deaths and higher enteral feeding rates were observed on the intermediate and regular dose treatment arms. This suggests a need to explore further de-intensification of CRT among sub-optimal responders to induction such as additional dose and volume reduction, and daily rather than twice-daily radiation. Our long-term follow-up identified late deaths following definitive CRT stressing the importance of long-term follow-up of de-escalation trials for HPV+ OPC.

Possible limitations of this study include the induction related toxicities including common mild neuropathy related to use of taxanes both in the induction and definitive setting, potential for selection bias for patients eligible for an intensive induction therapy regimen, and single-institution experience. Despite the use of TFHX-based chemotherapy with twice daily radiation administered in a week-on week-off fashion, our results are likely generalizable to cisplatin-based chemoradiation regimens, and we are currently investigating this approach (NCT04572100). Prior randomized studies have demonstrated no difference in outcomes with altered RT fractionation in setting of chemotherapy[23, 24]. Finally, eligibility for the OPTIMA trial and subsequent off-protocol treated patients was based on the AJCC 7th edition staging system. The updated AJCC 8th edition staging system for HPV-associated cancer serves as a better prognostic tool and incorporation into de-intensification trials will be critical to improve patient selection[5, 21].

Despite these limitations, our OPTIMA paradigm of induction chemotherapy followed by risk and response stratified de-escalated (C)RT is feasible and demonstrates excellent long-term survival. The role of immunotherapy in the paradigm for treatment de-escalation for HPV+ OPC is evolving. A follow-up trial called OPTIMA II incorporates nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, has accrued with encouraging early results[25]. However, recent randomized data incorporating immune checkpoint inhibitors concurrently with CRT have been disappointing, raising the question of how to best incorporate immune checkpoint inhibition in the context of treatment de-escalation for HPV+ OPC[26, 27].

In conclusion, here we report long term follow-up and expanded institutional experience with our OPTIMA de-escalation paradigm of induction chemotherapy followed by risk and response adaptive de-escalated (C)RT. Our data supports this strategy as a feasible and rational approach to treatment de-escalation in locoregional HPV+ OPC with excellent long-term survival and reduced toxicity with reduced dose and volume (C)RT. Future definitive studies are needed comparing a risk/response stratified de-escalated strategy with standard of care full-dose concurrent chemoradiation in the setting of HPV+ OPC.

Highlights.

Long-term outcomes of response-based de-escalation for HPV+ HNSCC are unknown

Expanded cohort of induction and response adaptive de-intensification

Substantial treatment de-escalation with excellent 5-year survival

Lower Enteral feeding rates in patients receiving de-intensified treatment

This strategy warrants evaluation in a randomized setting.

Acknowledgments

AJR reports research support paid to the institution: Merck, BMS, Celgene; Consulting/Scientific Advisory Board: Nanobiotix, EMD-Serono. AP reports salary support NIH K08-DE026500 and NIH U01-CA243075, and serves on advisory board for Prelude Therapeutics. AJ reports research funding from AstraZeneca. TYS has received honoraria and institutional grants from Merck, Nanobiotix, and Regeneron; honoraria from Innate Pharma, eTheRNA, BioNTech, and Nektar; and institutional grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, and AstraZeneca, all outside the submitted work. EEV reports consultant/advisory roles for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Beigene, BioNTech, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Novartis.

Support:

This study was supported by Celgene, Alinea benefit supported by Grant Achatz/Nick Kokonas, and the National Cancer Institution of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through Grant Number P30 CA14599.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: This study was presented in part at the ASCO Virtual Scientific Program.

Clinical Trial Information: This study contains data from the OPTIMA trial (NCT02258659).

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest:

Conflict of Interest Statement:

ZG, EB, JC, DG, AH, JC, SK, CF, NC, ML, EI, and DH report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- [1].Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human Papillomavirus and Rising Oropharyngeal Cancer Incidence in the United States. 2011;29:4294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tota JE, Best AF, Zumsteg ZS, Gillison ML, Rosenberg PS, Chaturvedi AK. Evolution of the Oropharynx Cancer Epidemic in the United States: Moderation of Increasing Incidence in Younger Individuals and Shift in the Burden to Older Individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1538–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, Cmelak A, Ridge JA, Pinto H, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rosenberg AJ, Vokes EE. Optimizing Treatment De-Escalation in Head and Neck Cancer: Current and Future Perspectives. Oncologist. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [6].Salama JK, Stenson KM, Kistner EO, Mittal BB, Argiris A, Witt ME, et al. Induction chemotherapy and concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: a multi-institutional phase II trial investigating three radiotherapy dose levels. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1787–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marur S, Li S, Cmelak AJ, Gillison ML, Zhao WJ, Ferris RL, et al. E1308: Phase II Trial of Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Reduced-Dose Radiation and Weekly Cetuximab in Patients With HPV-Associated Resectable Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oropharynx— ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;35:490–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen AM, Felix C, Wang PC, Hsu S, Basehart V, Garst J, et al. Reduced-dose radiotherapy for human papillomavirus-associated squamous-cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: a single-arm, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2017;18:803–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vokes EE, De Souza JA, Hannigan N, Brisson RJ, Seiwert TY, Villaflor VM, et al. Response-adapted volume de-escalation (RAVD) in locally advanced head and neck cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2016;27:908–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Seiwert TY, Foster CC, Blair EA, Karrison TG, Agrawal N, Melotek JM, et al. OPTIMA: a phase II dose and volume de-escalation trial for human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Foster CC, Seiwert TY, MacCracken E, Blair EA, Agrawal N, Melotek JM, et al. Dose and Volume De-Escalation for Human Papillomavirus-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer is Associated with Favorable Posttreatment Functional Outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107:662–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mehanna H, Robinson M, Hartley A, Kong A, Foran B, Fulton-Lieuw T, et al. Radiotherapy plus cisplatin or cetuximab in low-risk human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (De-ESCALaTE HPV): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gillison ML, Trotti AM, Harris J, Eisbruch A, Harari PM, Adelstein DJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab or cisplatin in human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (NRG Oncology RTOG 1016): a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;393:40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gebre-Medhin M, Brun E, Engström P, Cange HH, Hammarstedt-Nordenvall L, Reizenstein J, et al. ARTSCAN III: A Randomized Phase III Study Comparing Chemoradiotherapy With Cisplatin Versus Cetuximab in Patients With Locoregionally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021;39:38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rischin D, King M, Kenny L, Porceddu S, Wratten C, Macann A, et al. Randomised trial of radiotherapy with weekly cisplatin or cetuximab in low risk HPV associated oropharyngeal cancer (TROG 12.01) - a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [17].Yom SS, Torres-Saavedra P, Caudell JJ, Waldron JN, Gillison ML, Xia P, et al. Reduced-Dose Radiation Therapy for HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Carcinoma (NRG Oncology HN002). Journal of Clinical Oncology.0:JCO.20.03128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [18].Ferris RL, Flamand Y, Weinstein GS, Li S, Quon H, Mehra R, et al. Transoral robotic surgical resection followed by randomization to low- or standard-dose IMRT in resectable p16+ locally advanced oropharynx cancer: A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E3311). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38:6500-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chera BS, Amdur RJ, Tepper JE, Tan X, Weiss J, Grilley-Olson JE, et al. Mature results of a prospective study of de-intensified chemoradiotherapy for low-risk human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2018;124:2347–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chera BS, Amdur R, Shen CJ, Gupta GP, Tan X, Knowles M, et al. Mature results of the LCCC1413 phase II trial of de-intensified chemoradiotherapy for HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37:6022-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].O’Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J, Garden AS, Sturgis EM, Dahlstrom K, et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): a multicentre cohort study. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17:440–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gillison ML, Zhang Q, Jordan R, Xiao W, Westra WH, Trotti A, et al. Tobacco smoking and increased risk of death and progression for patients with p16-positive and p16-negative oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nguyen-Tan PF, Zhang Q, Ang KK, Weber RS, Rosenthal DI, Soulieres D, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial to Test Accelerated Versus Standard Fractionation in Combination With Concurrent Cisplatin for Head and Neck Carcinomas in the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0129 Trial: Long-Term Report of Efficacy and Toxicity. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:3858–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Seiwert TY, Melotek JM, Blair EA, Stenson KM, Salama JK, Witt ME, et al. Final Results of a Randomized Phase 2 Trial Investigating the Addition of Cetuximab to Induction Chemotherapy and Accelerated or Hyperfractionated Chemoradiation for Locoregionally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:21–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rosenberg AJ, Agrawal N, Pearson A, Seiwert TY, Gooi Z, Blair E, et al. Low risk HPV associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with induction chemoimmunotherapy followed by TORS or radiotherapy. Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancers Symposium. Scottsdale, AZ. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tao Y, Sun X, Sire C, Martin L, Alfonsi, Prevost JB, et al. LBA38 - Pembrolizumab versus cetuximab, concomitant with radiotherapy (RT) in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (LAHNSCC): Results of the GORTEC 2015–01 “PembroRad” randomized trial. Annals of Oncology (2020) 31 (suppl_4): S1142–S1215 101016/annonc/annonc325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lee NY, Ferris RL, Psyrri A, Haddad RI, Tahara M, Bourhis J, et al. Avelumab plus standard-of-care chemoradiotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2021;22:450–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]