Abstract

Background

Pharmacist services in general practice are expanding worldwide, with evidence to show pharmacists’ presence in general practice has financial, workload, and clinical benefits. Yet, little is known globally about general practitioners’ (GPs’) views on their presence in general practice.

Objective

To synthesize the qualitative research evidence on GPs’ views of pharmacist services in general practice.

Methods

Qualitative evidence synthesis; 8 electronic databases were searched from inception to April 2021 for qualitative studies that reported the views of GPs regarding pharmacist services in general practice. Data from included studies were analyzed using thematic synthesis. The Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (CERQual) approach was used to assess the confidence in individual review findings.

Results

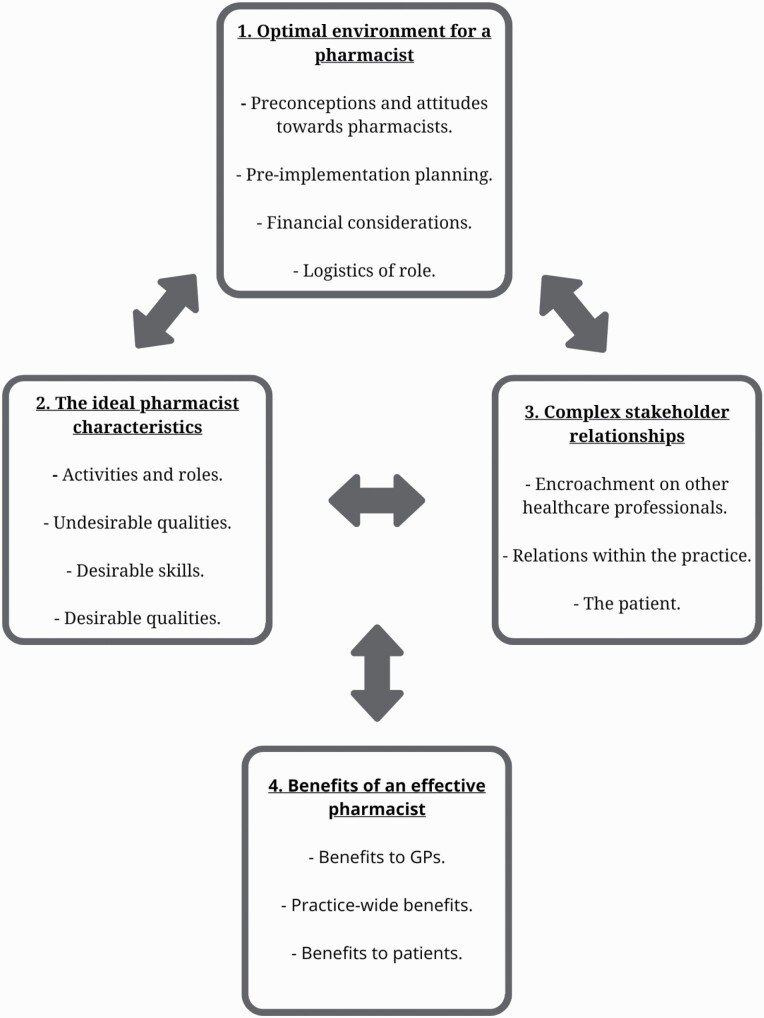

Nineteen studies were included, which captured the views of 159 GPs from 8 different countries. Four analytical themes describing the factors that should be considered in the development or optimization of pharmacist services in general practice, based on the views of GPs, were developed from the coded data and descriptive themes: (i) optimal environment for a pharmacist, (ii) the ideal pharmacist characteristics, (iii) complex stakeholder relationships, and (iv) benefits of an effective pharmacist.

Conclusion

Based on the synthesis of GPs’ views, we have created a conceptual model of factors that should be considered by policymakers, GPs, pharmacists, and other relevant stakeholders when developing or optimizing pharmacist services in general practice going forward.

Keywords: general practice, general practitioners, pharmacists, primary health care, qualitative research, systematic review

Key messages.

• General practitioners find pharmacists useful when optimizing complex patients´ medications.

• Role definition for pharmacists is key to avoid encroachment of others´ roles.

• Patient care is enhanced through safer and more efficient prescribing practices.

• External funding is likely required to support pharmacists in general practice.

Background

Medication usage is the most common healthcare intervention globally1 and continues to rise along with the increasing prevalence of chronic disease.2 The use of disease-specific guidelines by multiple physicians often results in multimorbid patients with complex medication regimens, which typically falls on the general practitioner (GP) to coordinate.3,4 Managing such patients places increased demands on GPs, who are already strained by issues with staff recruitment and retention.5 To alleviate some of this pressure, pharmacists have been integrated into general practice in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand, where they perform a range of activities like medication reviews and conducting medication reconciliation post hospitalization.6–13 A systematic review looking at health systems indicators and pharmacist integration into primary care teams demonstrated pharmacists’ potential to reduce GPs’ workloads, medication costs, and patient emergency department visits.14 Furthermore, pharmacists in nondispensing roles have led to improvements in several parameters associated with chronic disease states, including blood pressure, glycemic control, and blood lipid profiles.15

With a growing prevalence of pharmacists in general practice, it is vital to attain the relevant stakeholder views on such pharmacist services. GPs’ views are particularly pertinent given that pharmacist services in general practice in countries like England have shown significant growth, where GPs themselves have invested financially in the role.16 GPs are also considered to be local “opinion leaders” within practices,17 and any apprehension from GPs is associated with a high likelihood of influencing other practice staff members.17–19 To date, GPs’ views regarding pharmacist services in general practice have not been explored comprehensively or in any great depth. A realist review20 presented findings on GPs’ views amongst other topics. Findings in this review were from only 3 studies however,11,21,22 which were presented individually. Research around barriers and other seemingly important nuances were absent from the review.22–24 Given the increasing prevalence of such pharmacist roles as well as more recent publications in this field, there is a clear need to collate the up-to-date evidence in this regard. Therefore, the aim of this review was to address this knowledge gap by synthesizing, for the first time, the specific views of GPs of pharmacist services in general practice and use these findings to help optimize existing pharmacist services as well as to develop new pharmacist services in general practice.

Methods

The review protocol was registered in advance and is available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021224508.

Search strategy

The following electronic databases were searched from inception to 9 December 2020 for relevant studies: PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, and OpenGrey. The search strategy was adapted to suit the search capabilities of each database, as shown in the PRISMA-S Checklist (Supplementary Table 1). Only studies with full texts available in English were included, with no restrictions on publication date. The electronic search was rerun on 9 April 2021 to ensure the inclusion of all relevant publications. To identify further potentially eligible studies, the reference lists of included full texts were hand-searched, and citation searching of the included full texts was also conducted.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed studies were eligible for inclusion if they utilized qualitative research methods to evaluate GPs’ views of pharmacist services in the general practice setting. In order to capture the most conceptually rich data, surveys with open comment sections were excluded. Studies were not included where GPs’ views pertained to pharmacist services solely for academic detailing or in the management of specific conditions or medication classes. Where other stakeholders’ views were addressed, studies were only included if the data relating to GPs alone could be extracted. Where studies used a mixed methods approach, the qualitative data only were extracted.

Study selection

The references retrieved from database searching were imported into Zotero and duplicates removed. EH screened the titles of the remaining references to remove studies that were clearly not relevant to the review. All remaining titles and abstracts were then screened for inclusion independently by EH and LG. Thereafter, full-text articles were obtained and reviewed independently by EH and LG for inclusion. Any differences between the reviewers were resolved through discussion. Study characteristics were extracted by EH and cross-checked by LG.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of full texts was performed independently by EH and LG using the Critical Appraisals Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Studies Checklist.25 Studies were not excluded based on the quality assessment alone; it is possible that some studies’ failure to meet some of the CASP Checklist requirements may be due to inadequate reporting, and inadequately reported studies may still provide meaningful contributions to the synthesis.26 However, the quality assessment was taken into consideration when the confidence in the review findings was assessed by EH using the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) approach, whereby findings generated were assigned a confidence grade of high, moderate, low, or very low.27 Four components contribute to the confidence grade for each finding: methodological limitations of the primary qualitative studies, relevance, coherence, and adequacy of data. Confidence in review findings refers to the likelihood that the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest.27

Synthesis

Full-text papers were imported into NVivo 12 software to facilitate thematic synthesis—chosen for this qualitative evidence synthesis due to its largely epistemologically neutral stance, which may be more suited to health services research.28 This thematic synthesis involved 3 key steps: line-by-line coding, inductively developing descriptive themes from the codes, and then creating analytical themes which move beyond the descriptive themes resulting in interpretive models, explanations, or hypotheses.28

EH and LG independently performed line-by-line coding of all text in the results/findings section of each included full text (including themes, quotations, tables). A random portion of the coded text was then reviewed by 2 practising GPs (authors TF and EW) to ensure codes were truly rooted in the text of the studies; although none of the pharmacist authors (EH, LG, SB, and KD) previously worked in general practice, this step was taken to minimize bias that may have stemmed from EH and LG unconsciously seeking positive perceptions of pharmacists in the texts. The codes identified were grouped and findings were synthesized from grouped codes to facilitate the generation of the descriptive themes, followed by the development of the overarching analytical themes and a conceptual model was developed through iterative discussion amongst the review team to depict not only how the analytical themes were inter-related, but also to create an interactive system that could be manipulated to aid development or optimization of pharmacist services in general practice. The Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ) statement guided results reporting in this study (Supplementary Table 2).29

Results

Search results

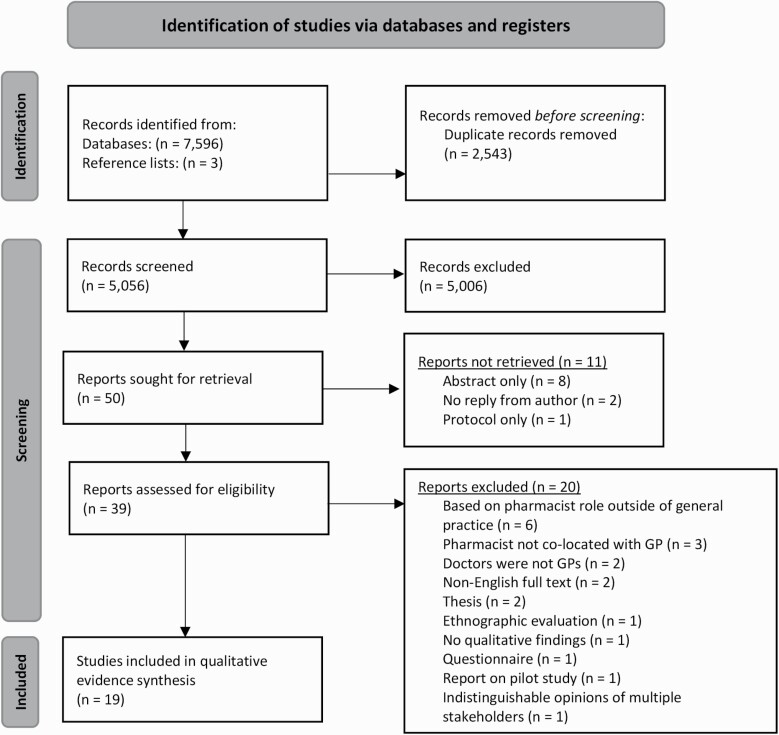

The flow of studies throughout the review is illustrated in Fig. 1, with reasons provided for the exclusion of full texts reviewed. After the review of 39 full texts, a total of 19 studies were included in this qualitative evidence synthesis, encompassing the views of 159 GPs from interviews and/or focus groups. The studies were conducted across 8 countries, with the majority from Australia (n = 6) and the United Kingdom (n = 4). Only 3 included studies in this review assessed the view of GPs prior to the implementation of a pharmacist in general practice23,30,31; of these 2 explored the views of GPs amongst other stakeholders,30,31 and the other assessed the views of GPs from private practice only.23 Detailed study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (published between 2008 and 2020).

| Author (year) | Country | Study aims | Qualitative data collection method and sampling approach | Timing of data collection | Methodology | Number of GPs in interviews and focus groups (n) | Data analysis approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajorek et al. (2015) (21) | Australia | To explore the perspectives of GP super clinic staff on current and potential (future) pharmacist-led services provided in this setting. | Semi-structured interviews Purposive |

During pharmacist employment in practice | Qualitative | GPs (3) | Thematic analysis |

| Benson et al. (2018) (40) | Australia | To conduct a preliminary process evaluation to inform the adaptation of the integrated pharmacist intervention. | Semi-structured interviews Convenience |

Posttrial of pharmacist in general practice | Mixed methods | GPs (5) | Framework analysis |

| Blondal et al. (2017) (11) | Iceland | To introduce and study pharmacist-led pharmaceutical care into primary care clinics in Iceland in collaboration with GPs by presenting different setting structures. | Semi-structured interviews NS |

Posttrial of pharmacist in general practice | Action research | GPs (5) | Thematic/content analysis |

| Deeks et al. (2018) (24) | Australia | To explore stakeholder perception about the role of the pharmacist and the benefits, enablers and barriers to implementation. |

Semi-structured interviews Purposive |

Posttrial of pharmacist in general practice | Mixed methods | GPs (4) | Thematic analysis |

| Duncan et al. (2020) (32) | England and Scotland | To explore GP and pharmacist perspectives on collaborative working within the context of optimizing medications for patients with multimorbidity. | Semi-structured interviews Purposive |

Posttrial of pharmacist in general practice | Qualitative | GPs (13) | Thematic analysis |

| Freeman et al. (2012) (30) | Australia | To describe the opinions of local stakeholders in South-East Queensland on the integration of a pharmacist into the Australian general practice environment. | Semi-structured interviews Convenience |

Theoretical views of GPs, i.e. if a pharmacist were to work in general practice | Qualitative | GPs (4) | Content analysis |

| Hampson et al. (2019) (35) | England | To explore the perspectives of GPs with experience of fully funding a pharmacist in general practice, focusing on the value that GPs place on the role of the pharmacist. | Semi-structured interviews Purposive |

During pharmacist employment in practice | Qualitative | GPs (7) | Thematic analysis |

| James et al. (2020) (41) | Ireland | To explore the implementation of the general practice pharmacist (GPP) intervention (pharmacists integrating into general practice within a nonrandomized pilot study in Ireland), the experiences of study participants and lessons for future implementation. | Semi-structured interviews Purposive |

Posttrial of pharmacist in general practice | Descriptive qualitative | GPs (4) | Thematic analysis |

| Jorgenson et al. (2014) (33) | Canada | To evaluate the barriers and facilitators that were experienced as pharmacists were integrated into 23 existing primary care teams located in urban and rural communities in Saskatchewan, Canada. | Semi-structured interviews Purposive |

During pharmacist employment in practice | Qualitative | Family physicians (3) | Thematic analysis |

| Kozminski et al. (2011) (34) | United States | To determine the acceptance and attitudes of family medicine physicians, clinical and nonclinical office staff, pharmacists, and patients during pharmacist integration into a medical home. | Interviews Purposive |

Posttrial of pharmacist in general practice | Qualitative | Family medicine physicians (21) | Thematic analysis |

| Lauffenburger et al. (2012) (42) | United States | To explore older adults' experiences working with a clinical pharmacist in managing medications, physician perspectives on the role of clinical pharmacists in facilitating medication management, and key attributes of an effective MTM program and potential barriers from patient and provider perspectives. | Focus groups Purposive |

During pharmacist employment in practice | Qualitative | Physicians (8) | Thematic analysis using natural language processing |

| Medgysei et al. (2020) (36) | Canada | To examine the perspectives of physicians who had a relatively long-standing relationship with a colocated pharmacist to identify barriers and facilitators to integrating a clinical pharmacist. | Semi-structured interviews Convenience |

During pharmacist employment in practice | Qualitative | Physicians (8) | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Moreno et al. (2017) (37) | United States | To examine and explore physician opinions about the clinical pharmacist program and identify common themes among physician experiences as well as barriers to integration of clinical pharmacists into primary care practice teams. | Semi-structured interviews Convenience |

During pharmacist employment in practice | Mixed methods | Primary care physicians (13) | Content analysis |

| Nabhani-Gebara et al. (2020) (43) | England | To investigate and map the experiences, thoughts and perceptions of pharmacists, physicians and nurses working in GP clinics throughout the South East of England, with a focus specifically on interprofessional relationships, power dynamics, changing interprofessional roles, and barriers and facilitators to the integration of the pharmacist. | Semi-structured interviews Purposive and snowball |

During pharmacist employment in practice | Mixed methods | GPs (9) | Thematic analysis |

| Pottie et al. (2008) (38) | Canada | To explore family physicians’ perspectives on collaborative practice 12 months after pharmacists were integrated into their family practices. | Semi-structured interviews Purposive |

Posttrial of pharmacist in general practice | Qualitative | Family physicians (12) | Thematic analysis |

| Ryan et al. (2018) (39) | England | To explore the experiences of stakeholders in 8 general practices in the Ealing GP Federation, West London, where pharmacy services have been provided for several years. | Semi-structured interviews Purposive |

During pharmacist employment in practice | Qualitative | GPs (7) | Interpretive thematic analysis |

| Saw et al. (2017) (23) | Malaysia | To explore the views of private GPs in Malaysia on integration of pharmacists into private primary healthcare clinics. | Focus groups and Semi-structured interviews Purposive and snowball |

Theoretical views of GPs, i.e. if a pharmacist were to work in general practice | Qualitative | GPs (13) | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Tan et al. (2013) (44) | Australia | To explore general practice staff, pharmacist and patient experiences with pharmacist services in Australian general practice clinics within the Pharmacists in Practice Study. | Focus groups Purposive |

Posttrial of pharmacist in general practice | Qualitative | GPs (9) | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Tan et al. (2014) (31) | Australia | To elicit the views of GPs and pharmacists on the integration of pharmacists into general practice in Australia. | Semi-structured interviews Convenience, purposive and snowball |

Theoretical views of GPs i.e. if a pharmacist were to work in general practice | Qualitative | GPs (11) | Framework analysis |

GP: General practitioner; NS: Not specified.

Quality appraisal of included studies

The quality appraisal results of the full texts are available in Supplementary Table 3. The 19 studies generally satisfied the 10 criteria set out by the CASP tool for judging the methodological quality of qualitative studies. However, author reflexivity was found to be a common issue, with only 5/19 studies (26%) reporting the impact of the relationship between the researcher and the participant during the study.24,31–34 Data analysis was flagged as a methodological weakness for 11/19 studies (58%) where there was uncertainty regarding the data analysis strategy; for example, it was unclear in some studies who had transcribed and/or coded the data.11,21,23,31,32,35–40 There was also a justification lacking for the research design in 7/19 studies (37%)—for example, the choice of focus groups over semi-structured interviews.21,24,31–34,36

Review findings

Four overarching analytical themes were identified to describe the factors that should be considered in the development or optimization of pharmacist services in general practice based on GPs’ views of pharmacist services in general practice. The conceptual model (Fig. 2) depicts how these analytical themes are inter-related and outlines the 14 descriptive themes that helped form each analytical theme. An overview of the conceptual model is provided underneath Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

A conceptual model of factors that should be considered in the development or optimization of pharmacist services in general practice based on the views of General practitioners. Each analytical theme—numbered above, with the corresponding descriptive themes as bullet points underneath—should be considered when developing or optimizing pharmacist services in general practice. The analytical themes 1, 2, 3 are inter-related (as indicated by the double-headed arrows) and represent targets for intervention or opportunities for modification in order to produce increased benefits from an effective pharmacist service. The benefits may then feed back (as indicated by the double-headed arrow) to the other factors and alter them (e.g. the benefit of reduced medication costs due to having pharmacists in general practice may stimulate further investment of government funding for additional pharmacist roles in this setting).

Under these descriptive themes, 54 individual findings were identified and are discussed below; of these, 12 findings were graded as high confidence, 21 as moderate confidence, 17 as low confidence, and 4 as very low confidence. Our level of confidence for each individual finding (from Sections “Preconceptions and attitudes toward pharmacists” to “Benefits to patient(s)” of the results) is outlined in Supplementary Table 4. A sample of illustrative quotations determined by the study authors to be the most representative of the descriptive themes is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Illustrative quotation.

| Descriptive theme | Quotations | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Preconceptions/attitudes of GPs toward pharmacists | “General practitioners stated that the intervention works best when general practitioners are enthusiastic and willing to collaborate.” Author | 40 |

| “They are doing consulting, examining, dispensing…What (is) the person(‘s) qualification?” GP | 23 | |

| Pre-implementation planning | “The interaction is only effective if medical records are viewed first.” GP | 42 |

| “There were mixed views on the level of training pharmacists should receive prior to working in general practice. Most felt that clinical experience and additional, ongoing training would be essential.” Author | 31 | |

| Financial considerations | “Some form of government remuneration for pharmacist services was collectively reported by all groups as a funding model.” Author | 30 |

| “And I think that is the difficult question. Everyone is feeling massively overloaded and are they going to see it as do you spend that money on a doctor or a nurse practitioner who can see patients or do you spend it on a pharmacist and go off on a different way.” GP | 43 | |

| Necessity/evidence for role | “To overcome these barriers, interviewees felt that a clear need for this position, and a well-defined role supported by local evidence, would be imperative.” Author | 31 |

| “I kind of didn’t really feel greatly engaged with changing that [the statin] particularly ‘cos, you know, if your cholesterol’s 3.4 I don’t think there’s a lot to be gained really.” GP | 32 | |

| Logistics of role | “Having somebody in house, (it) is the corridor talk and it’s difficult to quantify how helpful that is because you can say, “Can I just pick your brains on something?” If he wasn’t here, in the building, I don’t think I would.” GP | 39 |

| “Some GPs described the possibility that the thorough methodical approach of some pharmacists could tip the balance such that they were unable to complete the work at an appropriate pace to save GPs time or that they sometimes created additional work for the GPs which they viewed as unnecessary.” Author | 35 | |

| Activities/roles | “Physicians also had numerous ideas for expanded roles for pharmacists, including the development of “physician education seminars” in which pharmacists could periodically educate physicians and clinic staff on current medication issues and new medication guidelines.” Author | 37 |

| “We initiate insulin now. We have been doing that more in the office now that [the pharmacist] has been teaching the patients on how to use the syringes and how to use their glucometer.” GP | 38 | |

| Undesirable qualities | “I think that she [the pharmacist] would probably take twice or three times as long doing it as a GP.” GP | 32 |

| “I’m happy that they are focusing more on consumers that patients are important not just the pills.” GP | 11 | |

| Desirable skills | “I see the clinical pharmacist as having a special niche. Because of their detailed oriented training and medication management, they're much more fluent and immediately feel more comfortable with medicines.” GP | 42 |

| “Interviewees felt that it was important that the practice pharmacist has input into patient care and that this was complementary and nonjudgmental.” Author | 24 | |

| Desirable qualities | “Several general practitioners mentioned that they thought the pharmacist should be both clinically competent and pro-active, and effective communication skills were identified as a facilitator.” Author | 40 |

| “They need to be flexible and professional and adaptable and good communicators . . . All of the things we’d like all of our staff to be, or ourselves as well.” GP | 31 | |

| Encroach/threaten other healthcare professionals | “One GP compared this perceived threat to professional boundaries and identity to that observed during the introduction of nurse practitioners, although they suggested that this sentiment might be stronger since everything a nurse can do a GP can probably do, whereas anything a pharmacist can do the GP probably can’t.” Author | 39 |

| “I think GPs assume that this is the start of a slippery slope where pharmacists will try to expand their role and encroach on the GPs territory.” GP | 11 | |

| Relations within the practice | “I think that medicine is a whole team approach, and the more team members there are, the better care the patient gets, so it’s very good to have [the pharmacist] here.” GP | 34 |

| “There is a need to build a relationship of mutual trust between the clinical pharmacist and the physician so that the clinical pharmacist can understand the goals and approaches to treatment and the physician can have some knowledge of the clinical pharmacist’s skills.” GP | 42 | |

| The “patient” | “Patients love it. I mean the responses of patients have been uniformly positive. They like the fact that somebody else is involved with their care. It makes them feel important. And it also sort of empowers them. I mean [the pharmacist] has a way of giving back to them how they want to fix things up a little bit better.” GP | 38 |

| “One general practitioner stated that they had observed patient resistance to the service and that this was suggested to be a barrier to both recruitment of patients and the effectiveness of the intervention.” Author | 40 | |

| Benefits to GP(s) | “Everyone was getting incredibly stressed so we started to look around different ways that we could try and easy that burden so looked at things like nurse prescribers coming into the practice to work in these nurse practitioner clinics and a pharmacist to come in as well and that’s where it came from and it has made an enormous difference to the workload. It is now much more manageable.” GP | 43 |

| “So I got [the pharmacist] to look that up for me and really just to serve as a sounding board.… ‘Okay, is there anything here that you think could have been a problem?’ And [the pharmacist] was very reassuring, and that was great because number one, it gave me peace of mind, but it also served as reinforcement to my own thinking.” GP | 38 | |

| Practice-wide benefits | “One physician explained it as a more efficient use of health care resources because after a pharmacist consultation many of the patients did not return to the clinic as often as they would have otherwise.” Author | 23 |

| “It is real progress and a quality improvement that lifts up the operation of the primary care clinic.” GP | 11 | |

| Medication-related benefits | “Multiple physicians also commented on pharmacists’ influence on decreasing medication costs by contacting third parties for prior authorization in cases of potential claim rejections, informing patients about similar refill options.” Author | 37 |

| “We’ve been able to scale down the amount of medications and reduce the pill burden for these patients.” GP | 24 | |

| Benefits to patient(s) | “Complicated people, and sometimes when they come out of…hospital or if they’ve visited two or three specialists, then each one of them has made a small change, and getting [the practice pharmacist] to go over all the—what they are actually, really taking now, as opposed to what my computer thinks they’re taking – has been incredibly helpful.” GP | 24 |

| “[Pharmacists] have helped to educate patients and reinforce the adherence to medications.” GP | 37 |

Optimal environment for a pharmacist

Preconceptions and attitudes toward pharmacists

For a pharmacist to become integrated into a practice, there ideally should be at least one enthusiastic GP who is actively supportive of the pharmacist and has an appreciation for their skillset.23,36,40,41 GPs felt they need to act as a “visible champion” to explain or promote the pharmacist’s role to ensure understanding in order to avoid any misconceptions and encourage buy-in from patients and other practice staff.36,40 The presence of a pharmacist in the practice was often a new experience for GPs and tended to come with a sense of initial apprehension, which may have been linked with either a previous bad experience with a pharmacist or a lack of awareness of their training; this may be overcome as GPs observe pharmacists working within the practice.11,23,30,31,41 GPs felt more comfortable with such pharmacist roles when they or their colleagues had a positive experience working with pharmacists in general practice.23,36,41 There were mixed opinions about the usefulness of pharmacists’ prescribing recommendations in general (i.e. not specific to general practice settings); although they were mostly considered useful and well received, there were too many provided at times and some lacked significance.11,21,32,35,41,42 GPs were more receptive to the idea of pharmacists within their practice if there were allied healthcare professionals already working there.24

Pre-implementation planning

For a pharmacist to be able to work effectively within a practice, they should have confidentiality-bound access to patients’ electronic medical records (EMRs) as they may initially lack insight into the social and medical history of the practice patients.11,31,32,36,42 For a pharmacist to take up practice roles, GPs believed pharmacists should undergo additional ongoing training or accreditation.23,24,30,31 Any initial uncertainty about the pharmacist’s role could be mitigated by ensuring that the role is well defined ahead of time; however, role definition may vary from practice to practice and may require time to fully develop.11,23,30,31,34–36,40,42,43 Integration of a pharmacist may take time, GPs should anticipate this and plan to adjust their workflow to accommodate a pharmacist.36,38,39,41

Financial considerations

A sustainable funding model should be subsidized by governments, who first have to be convinced of health system benefits; asking GPs to fund pharmacist services in the practice themselves was considered unlikely to be feasible.23,24,30,31,35,41,42 Methods of reimbursement that would best support pharmacist services included remuneration for achieving set standards in quality measures and blended payment models.24,35,41,43 There was disagreement amongst GPs whether pharmacist services were cost effective; ultimately GPs reported that the costs of employing a pharmacist have to be counterbalanced against savings generated, improved task efficiency, and other patient-related outcome measures.32,35,36,39 Furthermore, the decision to hire a practice pharmacist should be weighed up against hiring another GP or practice nurse.32,43

Logistics of role

Physical space to accommodate pharmacists presented a barrier to the role in some practices.30,31,36,39 Co-location of pharmacists on site was crucial, so GPs can communicate face to face with them; however, GPs still felt it was important to receive some written communication as well.11,31,35–39,42 The optimal frequency of pharmacist presence in the practice was unclear. Everyday presence was likely to be optimal; however, some GPs preferred a part-time pharmacist or one pharmacist shared between multiple practices.31,34,35,39–41,44 Pharmacists should screen the practice’s EMR to identify suitable patients for pharmacist services and schedule patient appointments either side of GPs’ appointments.11,31,36,37,42,44

The ideal pharmacist characteristics

Activities and roles

GPs had a clear positive perception and were highly satisfied with the role of pharmacist services in general practice, which were perceived as helpful by GPs.11,24,31–33,35,36,38,41,44 GPs viewed pharmacists as having an important educational role, as they can provide medication-focused education to patients and practice staff11,30,33,36–39,41,44 and were considered notably useful in the management of complex patients.11,24,32,35,36,38,42 There were several activities that were deemed well suited to pharmacists performing in general practice, including repeat prescribing,32,37,39,41 auditing,31 medication reconciliation,24,31,35,42 medication reviews,21,31,32,38 liaising with community pharmacists,38,39 care of older adults,42 and chronic disease management35,38,39,41—particularly diabetes.37,38,42,43

Undesirable qualities

Some GPs were concerned pharmacists would be slower at performing the same tasks as GPs, follow guidelines too rigidly with an intolerance for uncertainty, struggle to think outside the box, tend to treat “the numbers,” and may be too technical and clerical.32,42 GPs in one study each from Australia and Malaysia found it difficult to see a separation from the role of the pharmacist as a dispenser of medication in a primary care setting.23,44

Desirable skills

GPs valued pharmacists’ extensive guideline-orientated knowledge of medications and their usage.11,21,31,32,34–39,41,42,44 Pharmacists in general practice should have adequate non-judgmental communication skills.24,31,35,37,40–42,44 Having a mix of previous hospital and community experience was considered desirable for pharmacists in general practice,24 as was the skill of prioritizing the prescribing recommendations provided.42

Desirable qualities

A proactive pharmacist was desired for the role to be viable in a practice.24,31,33,34,38,40,43 GPs expressed a preference for pharmacists to be assertive and passivity should be avoided.33,44 A pharmacist should be adaptable to suit the needs of an individual practice.31,34,35,38 The accessibility and availability of pharmacists in general practice was a desirable quality that acted as a facilitator to the role.24,31,37,39,42,44

Complex stakeholder relationships

Encroachment on other healthcare professionals

Pharmacists may encroach on the role of the practice nurse, taking work away from them and leading to conflict in practices.24,30,43 Some GPs perceived that pharmacists in general practice encroached on their own role and, in some cases, threatened their role, especially when it came to maintaining control over prescribing decisions.23,30–32,38–40 Pharmacists in general practice may disrupt GP–patient or community pharmacist–patient relationships.31,36,40

Relations within the practice

Pharmacists were seen as important team members, who work well in practice teams and enhance patient care.11,23,24,31,32,34–38,41,44 GPs wished for a close working relationship between themselves and the pharmacist, where there is a mutual understanding of each other’s roles.23,33,42,44 GPs highlighted a need to build a trusting relationship with the pharmacist; this may take time, during which the GP may gradually become assured of the pharmacist’s clinical knowledge.39,42

The patient

GPs declared that pharmacists were generally well accepted by patients; however, some reported patient apprehension due to the pharmacist’s presence in the practice.23,31,33,36–38,40,42,44 The apprehension was attributed to patients still being “doctor centered,” and this professional hierarchy may have blocked pharmacist input as patients were unwilling to change specialist-initiated medication; however, this apprehension was overcome by increasing patient-pharmacist interactions.21,23,32,40 Pharmacists may indirectly enhance patient–GP relationships by managing medication-related issues instead of GPs, leading to GPs having more time for patient-facing activities.39

Benefits of an effective pharmacist

Benefits to GP(s)

Pharmacists acted as a resource for GPs, which gave GPs greater confidence and a sense of reassurance regarding medication-related issues, which increased the likelihood of patients accepting GPs’ recommendations regarding their medications.35,37–39,41,44 Pharmacists may reduce GP workload overall, freeing up their time; however, pharmacists may increase GPs’ administrative workload, particularly at the beginning.11,31,32,35–39,41,43 GPs found working with pharmacists in general practice professionally rewarding.41

Practice-wide benefits

Pharmacist presence was a driver for quality and process improvement within the practice,11,31,35,41 with co-location improving the comprehensiveness of patients’ EMRs.31,44 Pharmacists may elicit more efficient healthcare utilization, as it was indicated that patients who experienced pharmacist involvement paid less frequent visits to the practice.24,36 Practices in England benefitted from reductions in the amount spent from practice prescribing budgets.39

Benefits to patient(s)

GPs described that patient care was enhanced by the presence of pharmacists in general practice.23,34–38,41 Pharmacists’ presence may lead to decreases in the total number of medications taken by patients and an improvement in the overall appropriateness of medication regimens.24,39 Improvements in medication adherence occur secondary to additional counseling and reinforcement provided by the pharmacist around medication use.24,36,37,44 Patient safety is enhanced due to improvements in prescribing.32,35,39,41 Patients experience safer transitions of care—e.g. from secondary or tertiary back to primary care—owing to pharmacist involvement in medication reconciliation.24,38 Medication costs for patients were reported to decrease in one study from the United States.37

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review is novel in that it is the first to focus specifically on synthesizing GPs’ views of pharmacist services in general practice. The 4 main analytical themes identified were (i) the optimal environment for a pharmacist, (ii) the ideal pharmacist characteristics, (iii) complex stakeholder relationships, and (iv) benefits of an effective pharmacist. These themes have been encapsulated in a conceptual model, which should be considered by policymakers, GPs, pharmacists, and other relevant stakeholders when developing or optimizing pharmacist services within the general practice setting.

Strengths and limitations

This review has explored GPs’ views in depth across a range of geographical and cultural contexts. Its transferability is enhanced further by the utilization of CERQual to illustrate our confidence in the findings—adding credibility, reliability, and transparency—and by the use of thematic synthesis so that the findings are more directly relevant both to policymakers and practitioners.28

Although this review involved a comprehensive search strategy, a potential limitation could be the exclusion of studies that focused on GPs’ views of pharmacist services in general practice only for certain medications or medical conditions. This may have excluded potentially useful GP views, but was done in order to better reflect the reality of pharmacist–GP collaboration in general practice, where a breadth of pharmacist services are provided to a wide variety of patients.45 This review also did not include studies that used surveys with open comment sections as their qualitative method. Although this may have resulted in the potential omission of nuanced GPs’ views, previous research has highlighted that open comment sections at the end of surveys can lack context and conceptual richness due to the brevity of responses.46,47

Comparison with existing literature

The views of other stakeholders regarding pharmacist services in general practice have been described in other primary qualitative studies, including patients, community pharmacists and other pharmacy staff, pharmacists working in general practice, as well as other practice staff.33,39,41,48–51 The findings of these studies are broadly in line with this review; one distinctive commonality between GPs in this review and other stakeholders was a need for role awareness and definition, in order to avoid issues like confusion between the role of the community pharmacist and the pharmacist in general practice.33,39,41,49,50 Other stakeholder views that mirrored our review findings included concerns around funding pharmacist roles in general practice, needing to build trust and a relationship with pharmacists over time, and generally having positive and productive interactions with pharmacists working in general practice.33,39,41,48,50,51

While this review found some initial uncertainty from GPs regarding the roles pharmacists could undertake in general practice and concerns with encroachment on their roles at the beginning or prior to pharmacist integration, pharmacists working in general practice in one study reported that demands on them within the practice were high, with frequent requests for pharmacist services in the practice from both patients and GPs.39 However, pharmacists in that study had been well established in the practice at the time of interviews. Therefore, while GPs may initially feel uncertain about such pharmacist roles, there is evidence that there is sufficient work available for pharmacists in general practice, which may accumulate over time as pharmacist services establish themselves fully in the practice, tipping the balance toward pharmacists in the practice feeling overburdened with work39; this should be anticipated ahead of time to ensure adequate supports and staffing levels are in place to prevent pharmacist burnout.

Overall, while not identical to GPs’ views, the perspectives of other stakeholders appear broadly similar to those of GPs with minor deviations, therefore reinforcing the transferability of our review findings.

Implications for research and practice

This review will inform policymakers, academics, GPs, and pharmacists when developing, implementing, evaluating, and optimizing pharmacist services in general practice. The findings of this review may be particularly useful in countries where little to no prior research or practical work has been undertaken to develop pharmacist services in general practice. To give a practical example of applying one of the CERQual-assessed findings (Supplementary Table 4): we have high confidence in the finding that GPs believe that such pharmacist services should be subsidized by governments as it would likely not be feasible for GPs to fund themselves; therefore, policymakers need to carefully consider a sustainable funding model going forward. This will be especially important in countries where such pharmacist roles have yet to gain traction, and where appropriate infrastructure and supports may not be in place. It may be prudent to emulate what has worked well in other countries regarding funding and acceptability of the role. In England, for example, a 2015 government-funded pilot scheme for pharmacists in general practice utilized a tapered funding model (where practices could apply for 60% of costs of employing pharmacists in year 1, 40% in year 2, and 20% in year 3), which was deemed acceptable by GPs due to its contribution to improved practice capacity, changes in workload, and medication optimization and safety.45 Although this may provide a template, it may be more difficult to replicate in countries that are more reliant on private health insurance for healthcare reimbursement.

Pharmacists were seen by GPs in this review as useful for managing complex patients; examples of this included diabetic patients, older adults, or those frequently hospitalized. This raises the question about other subsets of patients where pharmacists in general practice could prove particularly useful. This review has shown conflicting perspectives regarding pharmacists’ impact on workload in the practice. This aligns with the findings from a systematic review on the impact of pharmacists on health systems indicators in general practice, whereby the number of GP appointments appeared to decrease but overall primary healthcare use increased due to patient visits to the practice pharmacist—with the outcomes of such visits potentially increasing GPs’ workloads.14 Therefore, it may be beneficial to scrutinize this further and measure exactly in practice what is the actual impact of pharmacists on GPs’ daily workloads with respect to time, rather than relying solely on GPs’ subjective experiences of their workload.

As highlighted previously in the results, no primary qualitative study has focused only on exploring GPs’ views prior to implementation of pharmacist services, outside of a private practice setting. This gap in the literature could be addressed through interviews or focus groups to explore the views of GPs to identify further concerns, misconceptions, and opportunities with pharmacist roles in the general practice setting. The conceptual model developed in this review (Fig. 2) provides a framework that may inform the development of topic guides for further qualitative research studies. Furthermore, the conceptual model and review findings may also inform future feasibility studies in countries where the role is not well established as they allow study investigators to pre-empt and address some of the concerns and preferences of GPs ahead of time. For example, initial uncertainty regarding roles for pharmacists in general practice appeared almost ubiquitously throughout the included studies, even in countries like England where the role has become relatively widespread.

Conclusions

Although future pharmacist roles in general practice may need to be specifically tailored to individual countries or practices, this review has demonstrated the importance of having a well-defined role to dispel this initial uncertainty. Furthermore, the findings of this novel evidence synthesis show important considerations for creating the optimal conditions to host a pharmacist in general practice and navigating the complex stakeholder relationships—ultimately to achieve benefits to GPs and their practices, health systems, and most importantly to patients.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Eoin Hurley, Pharmaceutical Care Research Group, School of Pharmacy, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland.

Laura L Gleeson, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin, Ireland.

Stephen Byrne, Pharmaceutical Care Research Group, School of Pharmacy, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland.

Elaine Walsh, Department of General Practice, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland.

Tony Foley, Department of General Practice, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland.

Kieran Dalton, Pharmaceutical Care Research Group, School of Pharmacy, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland.

Funding

This work is supported by the Irish Research Council. EH is a Postgraduate (Government of Ireland) Scholarship Award Holder (GOIPG/2020/1070). The funders had no role in the review design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Data availability

Data were derived from sources in the public domain. All data were obtained from published papers.

References

- 1. National Institute for Health and care Excellence (NICE). Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. NICE Guideline NG5. [Published 2015. March 4; accessed 2021 June 23]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5/chapter/Introduction. [PubMed]

- 2. Balanda KP. Institute of Public Health in Ireland, Ireland and Northern Ireland’s Population Health Observatory. Making chronic conditions count: hypertension, stroke, coronary heart disease, diabetes: a systematic approach to estimating and forecasting population prevalence on the Island of Ireland. Institute of Public Health in Ireland: Ireland and Northern Ireland’s Population Health Observatory; 2010. [accessed 2021 March 9] http://www.inispho.org/files/file/Making%20Chronic%20Conditions.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3. von Buedingen F, Hammer MS, Meid AD, Müller WE, Gerlach FM, Muth C. Changes in prescribed medicines in older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vrdoljak D, Borovac JA. Medication in the elderly – considerations and therapy prescription guidelines. Acta Med Acad. 2015;44(2):159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baird B, Charles A, Honeyman M, Maguire D, Das P. Understanding pressures in general practice. London: The King’s Fund; 2016. p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haua R, Harrison J, Aspden T. Pharmacist integration into general practice in New Zealand. J Prim Health Care. 2019;11(2):159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baker S, Lee YP, Hattingh HL. An evaluation of the role of practice pharmacists in Australia: a mixed methods study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(2):504–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guénette L, Maheu A, Vanier MC, Dugré N, Rouleau L, Lalonde L. Pharmacists practising in family medicine groups: what are their activities and needs? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45(1):105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hazen ACM, Zwart DLM, Poldervaart JMet al. Non-dispensing pharmacists’ actions and solutions of drug therapy problems among elderly polypharmacy patients in primary care. Fam Pract. 2019;36(5):544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cardwell K, Smith SM, Clyne Bet al. ; General Practice Pharmacist (GPP) Study Group. Evaluation of the general practice pharmacist (GPP) intervention to optimise prescribing in Irish primary care: a non-randomised pilot study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e035087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blondal AB, Sporrong SK, Almarsdottir AB. Introducing pharmaceutical care to primary care in Iceland – an action research study. Pharm J Pharm Educ Pract. 2017;5(2):1–11. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy5020023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gums TH, Carter BL, Milavetz Get al. Physician-pharmacist collaborative management of asthma in primary care. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(10):1033–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Barra M, Scott CL, Scott NWet al. Pharmacist services for non-hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018(9):CD013102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hayhoe B, Cespedes JA, Foley K, Majeed A, Ruzangi J, Greenfield G. Impact of integrating pharmacists into primary care teams on health systems indicators: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(687):e665–e674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hazen ACM, de Bont AA, Boelman Let al. The degree of integration of non-dispensing pharmacists in primary care practice and the impact on health outcomes: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018;14(3):228–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mann C, Anderson C, Avery AJ, Waring J, Boyd M. Clinical pharmacists in general practice: pilot scheme: independent evaluation report: full report. 2018;1. doi: 10.17639/re5w-wp51 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Locock L, Dopson S, Chambers D, Gabbay J. Understanding the role of opinion leaders in improving clinical effectiveness. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(6):745–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fitzgerald L, Ferlie E, Hawkins C. Innovation in healthcare: how does credible evidence influence professionals? Health Soc Care Community. 2003;11(3):219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fitzgerald L, Ferlie E, Wood M, Hawkins C. Interlocking interactions, the diffusion of innovations in health care. Hum Relat. 2002;55(12):1429–1449. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anderson C, Zhan K, Boyd M, Mann C. The role of pharmacists in general practice: a realist review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(4):338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bajorek B, LeMay K, Gunn K, Armour C. The potential role for a pharmacist in a multidisciplinary general practitioner super clinic. Australas Med J. 2015;8(2):52–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Freeman C, Cottrell WN, Kyle G, Williams I, Nissen L. Does a primary care practice pharmacist improve the timeliness and completion of medication management reviews? Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20(6): 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saw PS, Nissen L, Freeman C, Wong PS, Mak V. Exploring the role of pharmacists in private primary healthcare clinics in Malaysia: the views of general practitioners. J Pharm Pract Res. 2017;47(1):27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deeks LS, Kosari S, Naunton Met al. Stakeholder perspectives about general practice pharmacists in the Australian Capital Territory: a qualitative pilot study. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(3):263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP qualitative checklist. [Published online 2018; 2020 Oct 31]. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf.

- 26. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas Het al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freeman C, Cottrell WN, Kyle G, Williams I, Nissen L. Integrating a pharmacist into the general practice environment: opinions of pharmacist’s, general practitioner’s, health care consumer’s, and practice manager’s. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tan EC, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Integration of pharmacists into general practice clinics in Australia: the views of general practitioners and pharmacists. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(1):28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duncan P, Ridd MJ, McCahon D, Guthrie B, Cabral C. Barriers and enablers to collaborative working between GPs and pharmacists: a qualitative interview study. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(692):e155–e163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jorgenson D, Laubscher T, Lyons B, Palmer R. Integrating pharmacists into primary care teams: barriers and facilitators. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(4):292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kozminski M, Busby R, McGivney MS, Klatt PM, Hackett SR, Merenstein JH. Pharmacist integration into the medical home: qualitative analysis. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2011;51(2):173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hampson N, Ruane S. The value of pharmacists in general practice: perspectives of general practitioners – an exploratory interview study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(2):496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Medgyesi N, Reardon J, Leung L, Min J, Yuen J. Family physician perceptions of barriers and enablers to integrating a co-located clinical pharmacist in a medical clinic: a qualitative study. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60(6):1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moreno G, Lonowski S, Fu Jet al. Physician experiences with clinical pharmacists in primary care teams. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57(6):686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pottie K, Farrell B, Haydt Set al. Integrating pharmacists into family practice teams: physicians’ perspectives on collaborative care. Can Fam Phys. 2008;54(12):1714–1717.e5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ryan K, Patel N, Lau WM, Abu-Elmagd H, Stretch G, Pinney H. Pharmacists in general practice: a qualitative interview case study of stakeholders’ experiences in a West London GP federation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Benson H, Sabater-Hernández D, Benrimoj SI, Williams KA. Piloting the integration of non-dispensing pharmacists in the Australian general practice setting: a process evaluation. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(2):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. James O, Cardwell K, Moriarty F, Smith SM, Clyne B. Pharmacists in general practice: a qualitative process evaluation of the General Practice Pharmacist (GPP) study. Fam Pract. 2020;37(5):711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lauffenburger JC, Vu MB, Burkhart JI, Weinberger M, Roth MT. Design of a medication therapy management program for Medicare beneficiaries: qualitative findings from patients and physicians. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(2):129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nabhani-Gebara S, Fletcher S, Shamim Aet al. General practice pharmacists in England: integration, mediation and professional dynamics. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16(1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tan EC, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Stakeholder experiences with general practice pharmacist services: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boyd M, Mann C, Anderson C, Avery A, Waring J. Evaluation of the NHS England Phase 1 pilot: clinical pharmacists in general practice. Int J Pharm Pract. 2019;27(S1):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Boulton M, Fitzpatrick R, Swinburn C. Qualitative research in health care: II. A structured review and evaluation of studies. J Eval Clin Pract. 1996;2(3):171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ. “Any other comments?” Open questions on questionnaires – a bane or a bonus to research? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Petty DR, Knapp P, Raynor DK, House AO. Patients’ views of a pharmacist-run medication review clinic in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(493):607–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morcos P, Dalton K. Exploring pharmacists’ perceptions of integrating pharmacists into the general practice setting. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2021;2:100027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Karampatakis GD, Patel N, Stretch G, Ryan K. Community pharmacy teams’ experiences of general practice-based pharmacists: an exploratory qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Karampatakis GD, Patel N, Stretch G, Ryan K. Patients’ experiences of pharmacists in general practice: an exploratory qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data were derived from sources in the public domain. All data were obtained from published papers.