Abstract

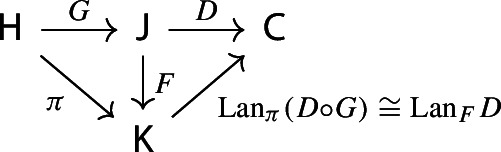

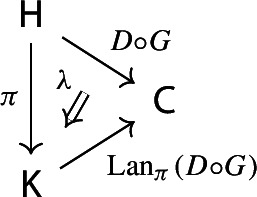

One way of interpreting a left Kan extension is as taking a kind of “partial colimit”, whereby one replaces parts of a diagram by their colimits. We make this intuition precise by means of the partial evaluations sitting in the so-called bar construction of monads. The (pseudo)monads of interest for forming colimits are the monad of diagrams and the monad of small presheaves, both on the (huge) category CAT of locally small categories. Throughout, particular care is taken to handle size issues, which are notoriously delicate in the context of free cocompletion. We spell out, with all 2-dimensional details, the structure maps of these pseudomonads. Then, based on a detailed general proof of how the restriction-of-scalars construction of monads extends to the case of pseudoalgebras over pseudomonads, we consider a morphism of monads between them, which we call image. This morphism allows in particular to generalize the idea of confinal functors, i.e. of functors which leave colimits invariant in an absolute way. This generalization includes the concept of absolute colimit as a special case. The main result of this paper spells out how a pointwise left Kan extension of a diagram corresponds precisely to a partial evaluation of its colimit. This categorical result is analogous to what happens in the case of probability monads, where a conditional expectation of a random variable corresponds to a partial evaluation of its center of mass.

Keywords: Kan extensions, Colimits, Presheaves, Partial evaluations

Introduction

Kan extensions are a prominent tool of category theory, to the extent that, already in the preface to the first edition of [21], Mac Lane declared that “all concepts of category theory are Kan extensions”, a claim reinforced more recently in [27, Chapter 1]. However, they are also considered to be a notoriously slippery concept, especially by newcomers to the subject. One of the most powerful pictures that help understanding how they work may be the idea that Kan extensions, especially in their pointwise form, “replace parts of a diagram with their best approximations, either from the right or from the left”. In other words, Kan extensions can be seen as taking limits or colimits of “parts” of a diagram. The scope of this paper is making this intuition mathematically precise.

We make use of the concept of partial evaluation, which was introduced in [9], and which is a way to formalize “partially computed operations” in terms of monads. The standard example is that “” may be evaluated to “10”, but also partially evaluated to “”, whereby parts of the given sum have been replaced by their sums.

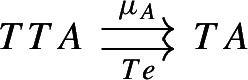

Just as monads on sets may be seen as encoding different algebraic structures and operations, here we consider pseudomonads on categories which encode the operation of taking colimits. We are in particular interested in two pseudomonads: the monad of diagrams and the monad of small presheaves (also known as the free (small) cocompletion monad). Both monads are known in the literature, but certainly not presented in sufficient detail as needed for our purposes. To make the paper more accessible, we therefore decided to spell out their definition in full detail, in Sects. 2 and 4.

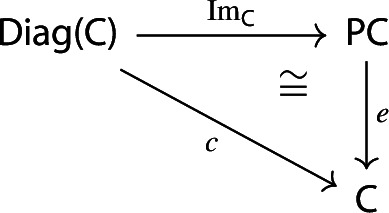

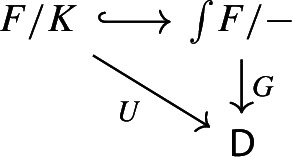

There is a functor connecting diagrams and presheaves, which we call the image presheaf, and which appears in the literature under the name of connected component functor [23] (at least for the case of small categories). This construction takes a diagram and forms a presheaf that can be considered the “free colimit” of the diagram. We describe the construction in detail in Sect. 3, taking care of the size issues we face when the codomain of diagrams is not small.

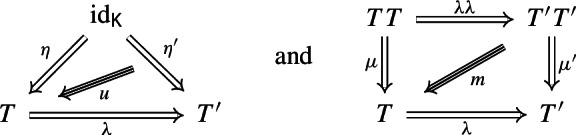

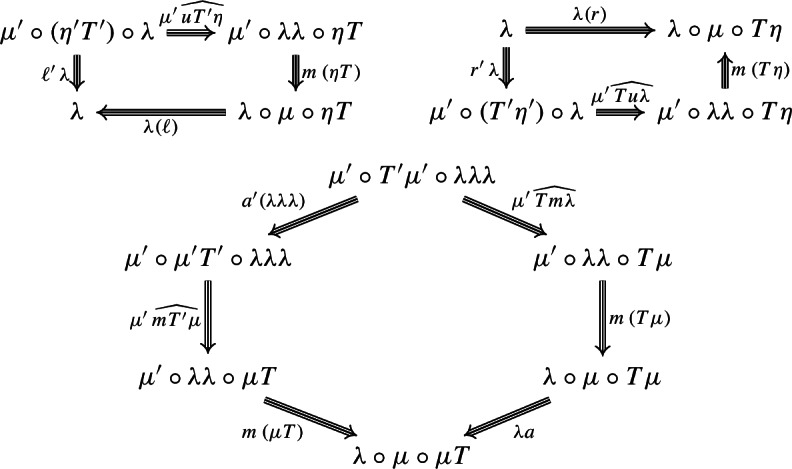

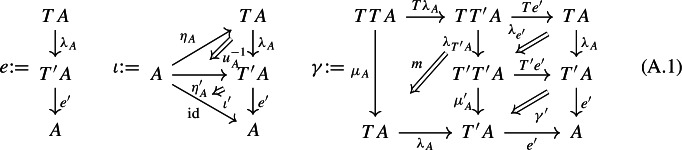

The definitions of pseudomonads, pseudoalgebras, and their morphisms are also hard to find in the literature in sufficient detail. For this reason, to avoid any ambiguity, we have given a detailed account of them in Appendix A. Readers who are familiar with these pseudomonads, and with the concepts of pseudomonads in general, may skip these sections, with the exception of Sects. 2.5, 4.6 and Appendix A.3, which contain new results.

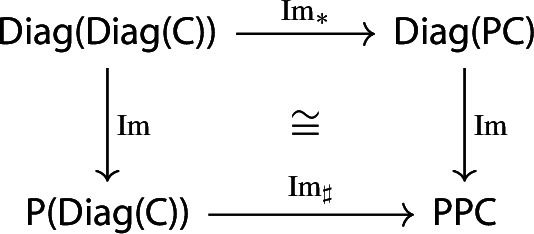

Here is what the novel content of this work consists of. First of all, we show that the image presheaf induces a morphism of monads from the monad of diagrams to the monad of small presheaves, which in turn gives a pullback functor between the categories of algebras (we prove the 2-dimensional version of this statement in Appendix A.3). This morphism of monads is not injective in any sense. Indeed, it turns out that diagrams with isomorphic image presheaves have the same colimit, in a very strong sense, analogous to “differing by a confinal functor”. We indeed generalize the theory of confinal functors, and connect it to the theory of absolute colimits – both because we need that in order to prove the subsequent statements, and because it should be interesting for its own sake.

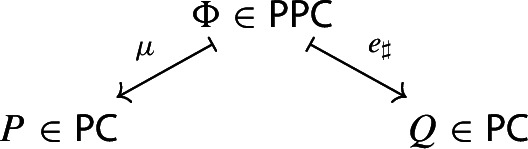

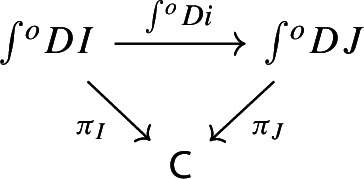

We then turn to the central topic of this paper and study partial evaluations for both monads. We prove that partial evaluations for the monad of diagrams correspond to pointwise left Kan extensions along split opfibrations, by invoking the Grothendieck correspondence between split opfibrations and functors into . For the monad of small presheaves, we show that partial evaluations correspond to pointwise left Kan extensions along arbitrary functors. This result may be summarized in the following way: given small presheaves P and Q on a locally small, small-cocomplete category, Q is a partial colimit of P if and only if they can be written as image presheaves of small diagrams D and , in such a way that is the left Kan extension of D along some functor. More concisely, Kan extensions are partial colimits, as claimed by the paper’s title.

This result is analogous to, and was motivated by, an analogous result in measure theory involving probability monads, where partial evaluations (or “partial expectations”) correspond exactly to conditional expectations (Theorem 5.13). Indeed, one could say that “if coends are like integrals, then Kan extensions are like conditional expectations”. (See Sect. 5.4 for more on this.)

As usual, when one talks about free cocompletion, one has to be very careful with size issues. This is why some parts of this work, such as the proof of Lemma 5.12, appear to be rather technical. The payoff is that the main theorems of this work will hold for arbitrary (small) colimits in arbitrary (locally small) categories, beyond the trivial case of preorders.

Outline. In Sect. 2 we study the category of diagrams in a given category, and show that the construction gives a pseudomonad on the 2-category of locally small categories. While this construction seems to be known, its details don’t seem to have been spelled out previously. The content of Sect. 2.5, however, seems to be entirely new. We show that cocomplete categories, equipped with a choice of colimit for each diagrams, are pseudoalgebras over this pseudomonad, and that not all pseudoalgebras are of that form.

In Sect. 3 we study the concept of image presheaf, which can be seen as a “free colimit of a diagram”, or as a “colimit blueprint”. We show that having the same image presheaf is a strong and consistent generalization both of the theory of confinal functors (Proposition 3.9), and of the concept of absolute colimit (Proposition 3.13). The main ideas are already known in the literature for the case of small categories. We restate some of them to take care of the size issues we face (since some of our categories are only locally small).

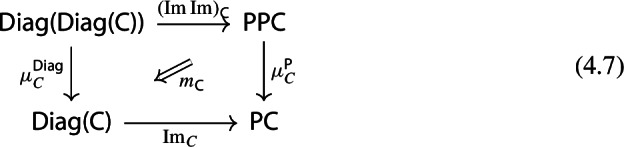

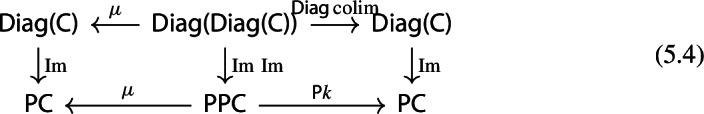

In Sect. 4 we study small presheaves and show that they form a pseudomonad. Again, this is known, but here we spell out the construction in much greater detail than previous accounts have done. This enables us to establish the new result presented in Sect. 4.6: the image presheaf construction forms a morphism of pseudomonads from diagrams to presheaves.

The principal new results of this paper appear in Sect. 5. Theorem 5.5 and Theorem 5.6 state that partial colimits for the monad of diagrams correspond to pointwise left Kan extensions of diagrams along split opfibrations. In Theorem 5.10 we prove that partial colimits for the free cocompletion monad correspond to pointwise left Kan extensions of diagrams along arbitrary functors. Then, in Sect. 5.4, we compare this categorical result to the analogous measure-theoretic fact that partial expectations for probability monads correspond (in some cases) to conditional expectations of random variables. This is in line with the famous analogy between coends and integrals.

Finally, in Appendix A we recall the (known) definition of pseudomonads and pseudoalgebras, and of the categories they form, which we use in the rest of the paper. We also provide a 2-dimensional version of the restriction of scalars construction (Theorem A.7), where a morphism of monads induces a functor between the categories of their algebras in opposite direction. As far as we know, this 2-dimensional version has not appeared in the literature previously.

Categorical setting, notation, and conventions. As it is to be expected when one talks about generic colimits, size issues are relevant. Here are our conventions.

All the categories in this work (except ) are assumed locally small. We denote by the 2-category of small categories, and by the 2-category of possibly large, locally small categories. Note that is itself larger than a large category (some authors call it a huge category).

When we say “category”, without specifying the size, we will always implicitly refer to a possibly large, locally small category.

Similarly, by “cocomplete category” we always mean a possibly large, locally small category which admits all small colimits.

The Monad of Diagrams

In this section we define the monad of diagrams. The first source for it that we are aware of is Guitart’s article [12], but without an explicit construction, and some concepts date back at least to Kock’s PhD thesis [16] (without the higher-dimensional aspects yet). We give in detail all the structure maps, and in Sect. 2.5 we prove that cocomplete categories with a choice of colimits are pseudoalgebras (but not all pseudoalgebras are in this form). The notions of pseudomonad and pseudoalgebra that we use are given in detail in Appendix A.

Note that, differently from some of the literature, we use the following slightly generalized notion of morphism of diagrams (also used in Guitart’s original work [12], and dating back to the origins of category theory [7, Section 23]). Moreover, in order to avoid size issues, we require every diagram to be small.

Definition 2.1

Let be a locally small category.

We call a diagram in a small category together with a functor . Throughout this work, all the diagrams will be implicitly assumed to be of this form (i.e. be small).

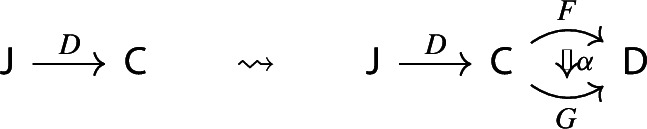

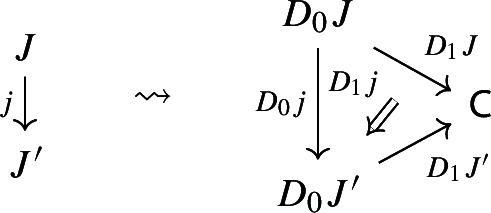

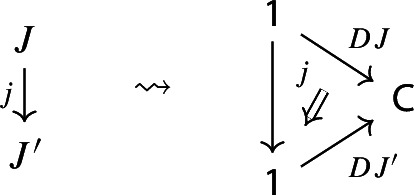

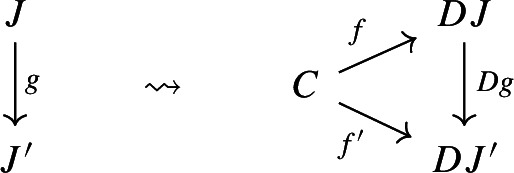

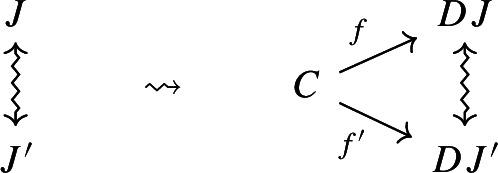

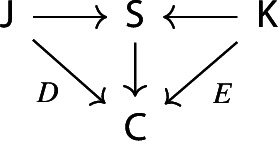

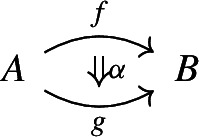

Given diagrams and in , we call a morphism of diagrams a functor together with a natural transformation , i.e. a diagram in as the following.

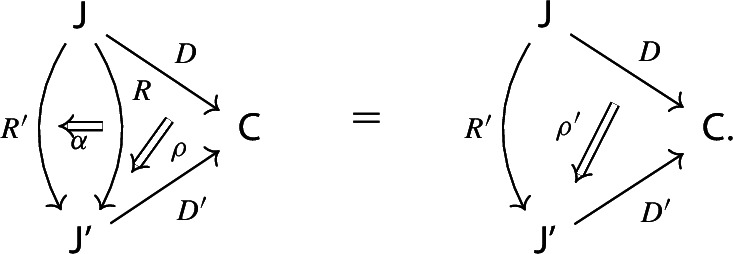

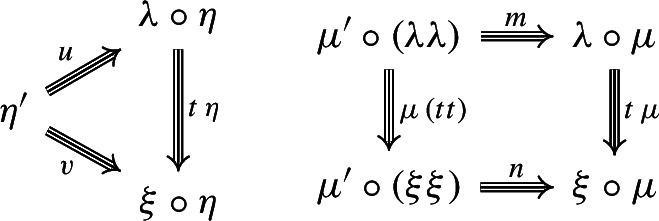

Given diagrams and in D and morphisms of diagrams , we call a 2-cell of diagrams a natural transformation such that the following 2-cells are equal.

We denote by the 2-category of diagrams in , their morphisms, and their 2-cells. (Sometimes we will still denote by the underlying 1-category.)

Note that the definition of morphism of diagrams is slightly more general than just a natural transformation between parallel functors. This is still compatible with the traditional intuitive picture of “deforming a diagram into another one”, provided that one notices the following. In principle R may be not essentially surjective, so one should visualize the natural transformation as “deforming” the figure drawn by D into a subfigure of the one drawn by .

Note moreover that:

For locally small, is locally small too;

The forgetful functor given by the domain is a fibration (via precomposition), and it is an opfibration (via left Kan extensions) if and only if is cocomplete (see for example [26, Proposition 2.8]).

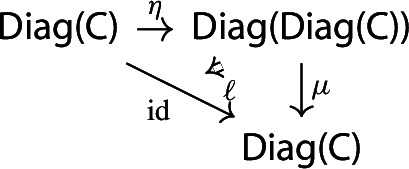

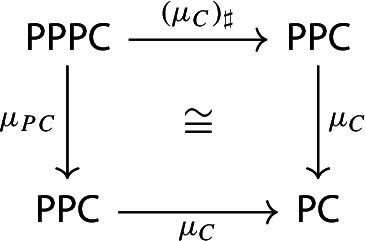

In the rest of this section we show that is part of a pseudomonad on , and that cocomplete categories with a choice of colimit for each diagram are pseudoalgebras, with the structure map given by such chosen colimits. For the precise definitions of pseudomonads and pseudoalgebras, see Appendix A.

Functoriality

We show that the assignment is part of a 2-functor on . First of all, let and be locally small categories, and let be a functor.

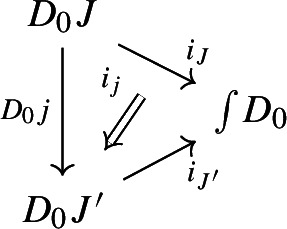

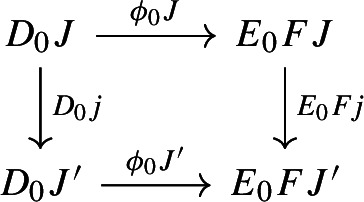

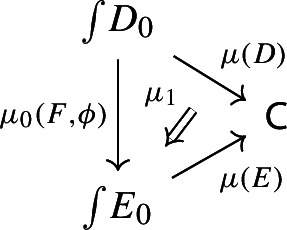

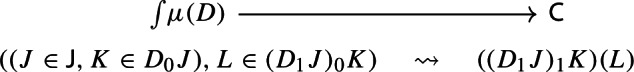

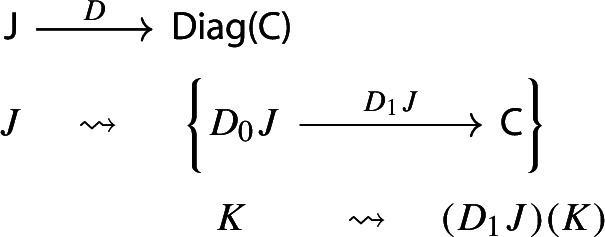

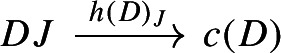

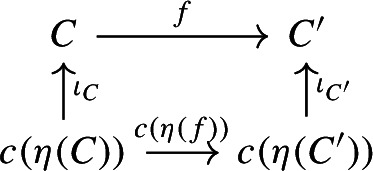

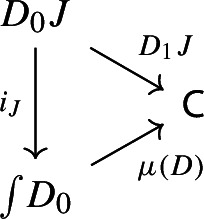

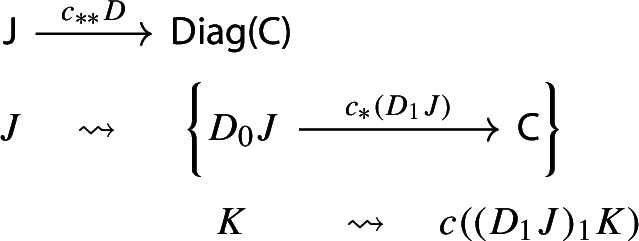

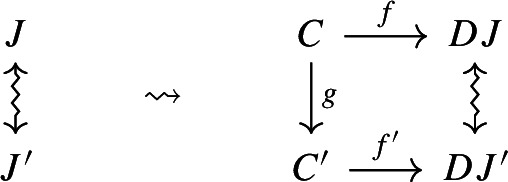

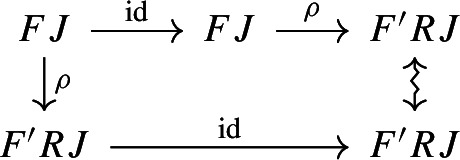

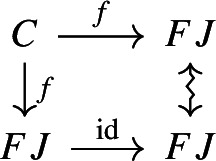

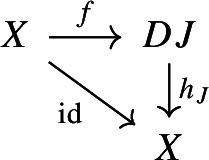

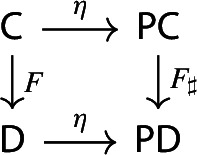

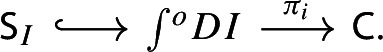

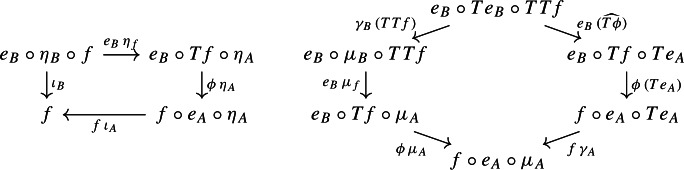

Consider now and as 1-categories. There is a (1-)functor induced by F via postcomposition and whiskering, as follows. ![]()

Therefore, is an endofunctor of .

Therefore, is an endofunctor of .

The functor extends to 2-cells giving a 2-functor, but we will not need this in order for to be a pseudomonad on .

On the other hand, we need to extend to the 2-cells of . So let and be locally small categories, let be functors, and let be a natural transformation. We have an induced natural transformation induced via whiskering, as follows. To each diagram in , we assign the morphism of diagrams of , i.e.  Naturality follows from naturality of . This makes a strict 2-functor .

Naturality follows from naturality of . This makes a strict 2-functor .

Unit and Multiplication

The Unit: One-Object Diagrams

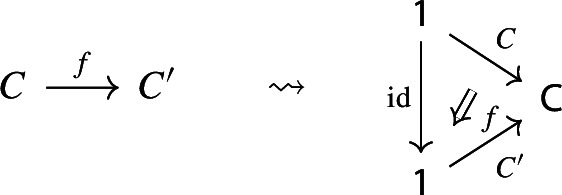

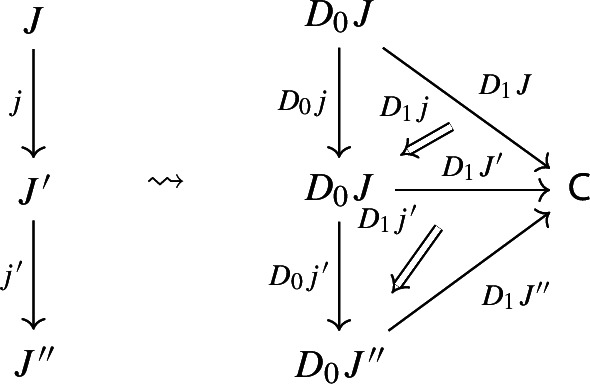

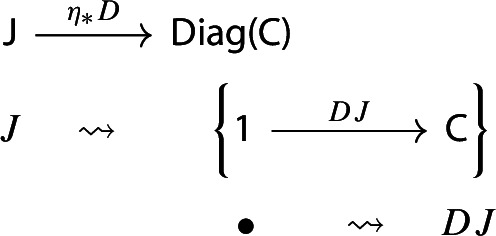

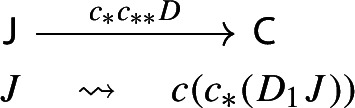

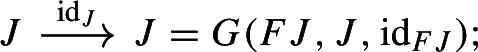

The unit of the monad is a map constructing “one-object diagrams”. In detail, let be a locally small category. We construct the functor as follows. ![]()

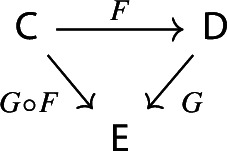

For brevity, we will denote simply by . This is (strictly) natural in the category : given a functor , the following diagram commutes strictly.

For brevity, we will denote simply by . This is (strictly) natural in the category : given a functor , the following diagram commutes strictly.  Indeed, both paths in the diagram give the following assignment,

Indeed, both paths in the diagram give the following assignment, ![]()

using the fact that if we view C as a functor , and that analogously Ff is given by whiskering f (seen as a natural transformation) with F.

using the fact that if we view C as a functor , and that analogously Ff is given by whiskering f (seen as a natural transformation) with F.

Diagrams of Diagrams are Lax Cocones

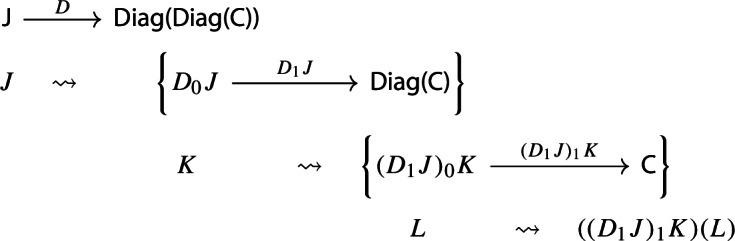

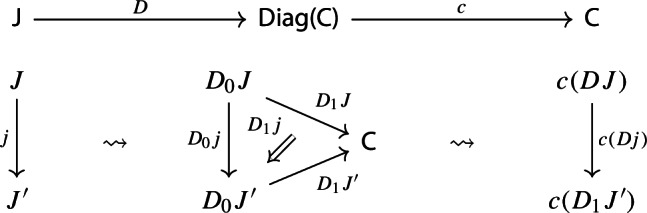

Let’s now turn to the multiplication. We first notice that an object of is the same as a lax cocone in with tip , where the indexing category and all the categories appearing in the cone except are required to be small. Let’s see how. Let be a small category. A functor assigns to each object J of a diagram in , i.e. a small category together with a functor :  and to each morphism of a morphism of diagrams, which amounts to a functor together with a natural transformation as below:

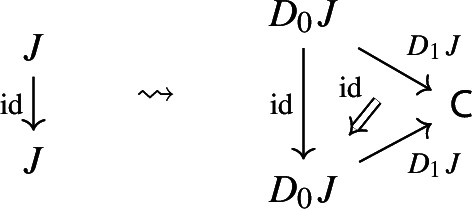

and to each morphism of a morphism of diagrams, which amounts to a functor together with a natural transformation as below:  Moreover, since we want D to be a functor, we need it to preserve identities and composition, i.e. needs to be a functor, and needs to satisfy the conditions and , which are exactly the conditions of lax naturality. In pictures,

Moreover, since we want D to be a functor, we need it to preserve identities and composition, i.e. needs to be a functor, and needs to satisfy the conditions and , which are exactly the conditions of lax naturality. In pictures,

In other words, a functor consists of a functor , together with a lax cocone in under with tip . A lax cocone is a lax natural transformation , where is the constant functor at . For brevity, we will also write constant functors simply as objects.

In other words, a functor consists of a functor , together with a lax cocone in under with tip . A lax cocone is a lax natural transformation , where is the constant functor at . For brevity, we will also write constant functors simply as objects.

The Multiplication: the Grothendieck Construction

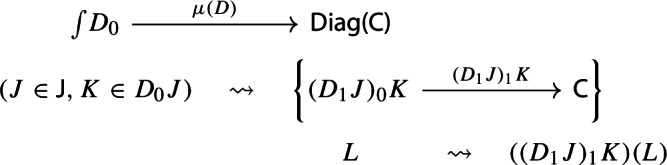

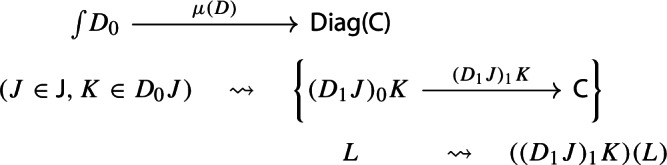

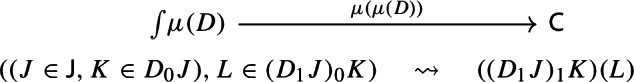

Given now as above, take the Grothendieck construction of , which we recall.

An object of consists of a pair (J, X) where J is an object of and X is an object of the category ;

A morphism of consists of a pair (j, f) where is a morphism of , and is a morphism of the category .

The short integral sign does not denote a coend here, it is standard for the Grothendieck construction (we use different sizes to avoid confusion, since both symbols are standard notation). Note that since and all the are small, is small too. Its set of objects is given by

Moreover:

For each object J of , the inclusion maps defined by the coproduct above can be canonically made into functors via

We will call the images of the the fibers of .

We will call the images of the the fibers of .For each morphism of , there is a natural transformation

whose component at each object X of is given by

whose component at each object X of is given by

The and assemble into a lax cocone , i.e. the identity and composition conditions are satisfied.

It is well known that is the oplax colimit of in , with the universal lax cocone given by the . We now show that it is so also in , and we also give a strict version of the universal property.1

Proposition 2.2

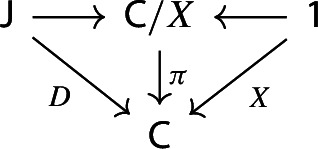

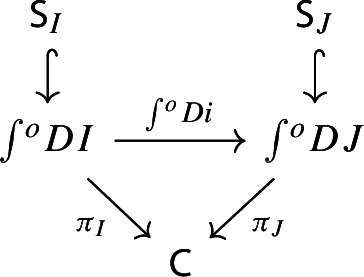

Let be a small diagram of small categories. Let be a lax cocone over in , with tip locally small (but not necessarily small). There is a unique functor such that

For all objects J of , the following triangle commutes (strictly);

Denote this functor by , or more briefly by . It is a diagram in . This will give the multiplication of the monad .

Proof of Proposition 2.2

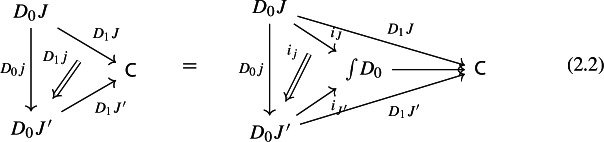

Since we want the diagram 2.1 to commute strictly, the only possibility to define on objects is as follows. For every object J of , and for every object X of ,

Just as well, for all the morphisms of in the fiber, i.e. in the form for a morphism of , we are forced to define

Moreover, since we want the condition (2.2) to hold, for all morphisms of we have to require that on the components of has to give the respective component of . Explicitly, for each object X of ,

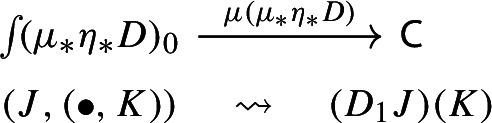

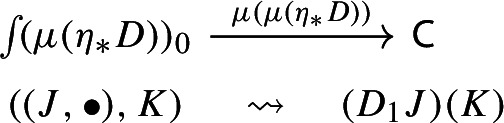

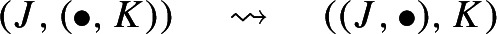

The generic morphism , for and can be decomposed as ![]() and so we have determined the action of for all morphisms of .

and so we have determined the action of for all morphisms of .

Functoriality of this assignment is routine.

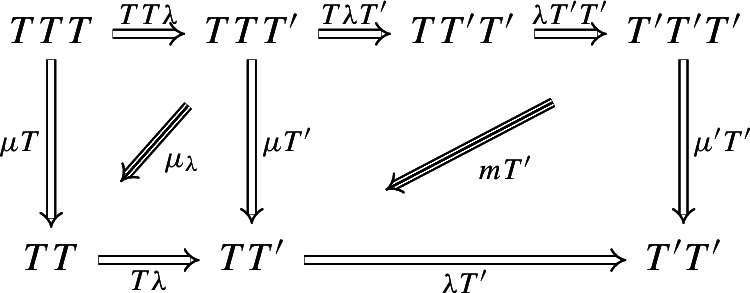

Functoriality and Naturality of the Multiplication

We now have to show that the assignment is functorial, and that it is natural in the category .

To address functoriality, we need to look at morphisms in .

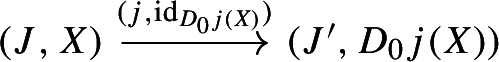

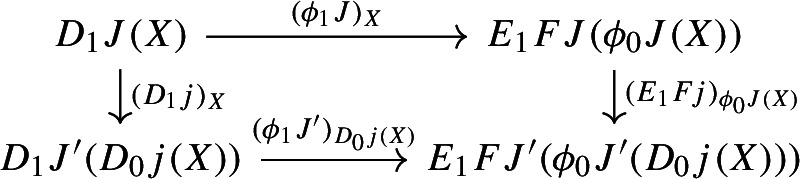

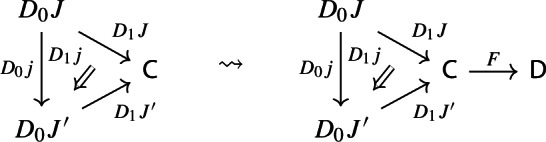

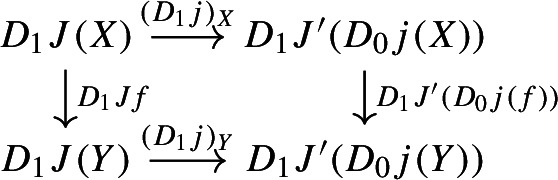

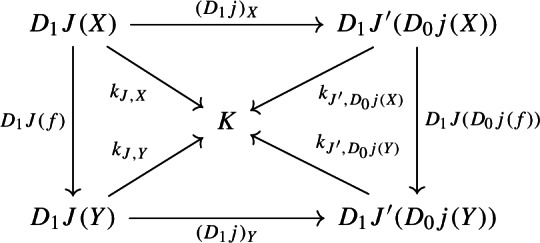

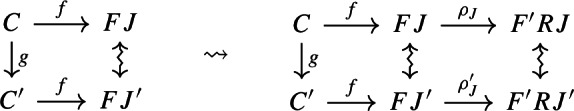

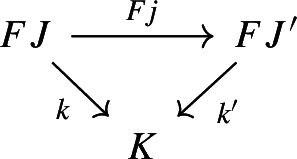

Given diagrams and , where and are small categories, a morphism of diagrams from D to E amounts to a functor together with a natural transformation  Explicitly, D consists of a functor and a lax cocone , and E has an analogous form. The natural transformation amounts to the following. For each object J of , we have a morphism of diagrams

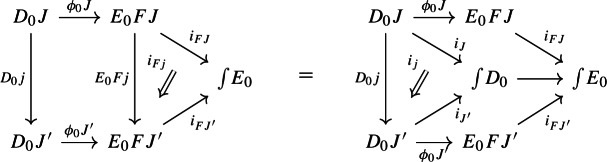

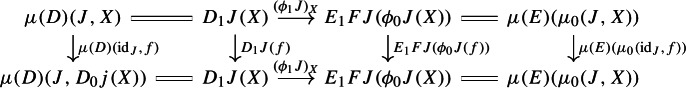

Explicitly, D consists of a functor and a lax cocone , and E has an analogous form. The natural transformation amounts to the following. For each object J of , we have a morphism of diagrams  and for each morphism of , the following diagrams have to commute. First of all, this diagram of functors has to commute strictly.

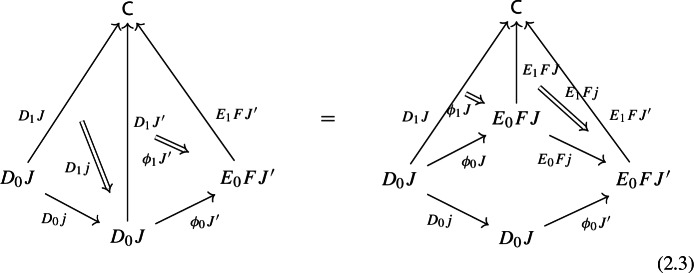

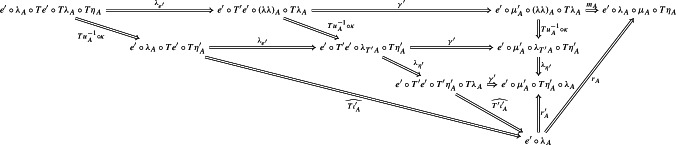

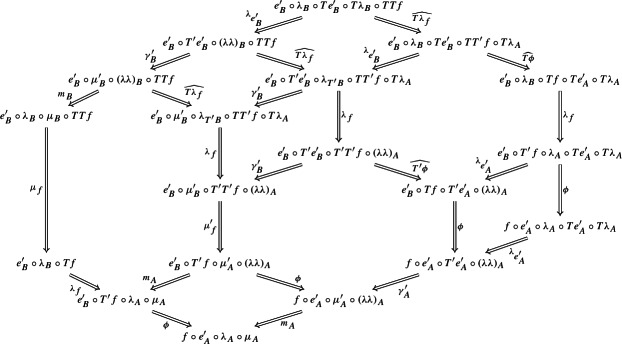

and for each morphism of , the following diagrams have to commute. First of all, this diagram of functors has to commute strictly.  Moreover, the following composite 2-cells have to coincide, forming a commutative pyramid with 2-cells as lateral faces, whose square base is the commutative square just described above.

Moreover, the following composite 2-cells have to coincide, forming a commutative pyramid with 2-cells as lateral faces, whose square base is the commutative square just described above.

Form now the Grothendieck construction of . We can form a lax cocone over with tip as follows.

Note that this is a lax cocone . By the universal property of the Grothendieck construction as an oplax colimit (Proposition 2.2), there is a unique functor such that

for all objects J of , the following square commutes;

for all morphisms of , the following composite 2-cells coincide.

Denote this functor by . This gives a triangle  which does not necessarily commute. In order to get a morphism of diagram we need to fill the triangle above with a 2-cell which we form as follows. Consider the object (J, X) of , where J is an object of and X is an object of . Note that, by the diagram (2.1), . Analogously, using the diagram (2.1) for E together with the diagram (2.4),

which does not necessarily commute. In order to get a morphism of diagram we need to fill the triangle above with a 2-cell which we form as follows. Consider the object (J, X) of , where J is an object of and X is an object of . Note that, by the diagram (2.1), . Analogously, using the diagram (2.1) for E together with the diagram (2.4),

We now assign to the object (J, X) the morphism of given by the component of at X, ![]() Let’s now show that this assignment is natural. We will again test this first along the fibers, and then on the opcartesian morphisms of . So let be a morphism of . The following diagram commutes simply by naturality of .

Let’s now show that this assignment is natural. We will again test this first along the fibers, and then on the opcartesian morphisms of . So let be a morphism of . The following diagram commutes simply by naturality of .  Let now be a morphism of . We have to prove that the following diagram commutes.

Let now be a morphism of . We have to prove that the following diagram commutes.  This is however exactly Equation (2.3), written out in components. Therefore we have a natural transformation, which we denote by , and we get a morphism of diagrams

This is however exactly Equation (2.3), written out in components. Therefore we have a natural transformation, which we denote by , and we get a morphism of diagrams  which makes functorial. (The identity and composition conditions follow by uniqueness.) Note that in particular this shows functoriality of the Grothendieck construction not only on strictly commutative triangles of functors (i.e. in ), but also more in general for lax-commutative triangles.

which makes functorial. (The identity and composition conditions follow by uniqueness.) Note that in particular this shows functoriality of the Grothendieck construction not only on strictly commutative triangles of functors (i.e. in ), but also more in general for lax-commutative triangles.

Proposition 2.3

The functor is strictly natural in .

Proof

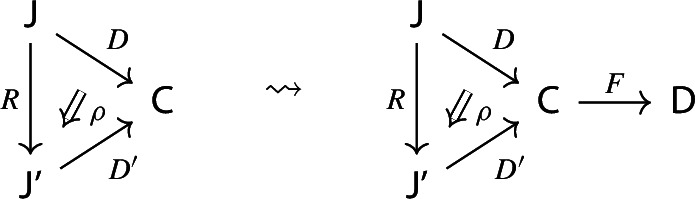

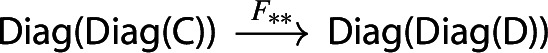

Let be a functor. The induced functor  maps a lax cocone with tip to the lax cocone with tip obtained simply via postcomposition with F.

maps a lax cocone with tip to the lax cocone with tip obtained simply via postcomposition with F.  In other words, . If we take the Grothendieck construction in both cases we get morphisms and . By uniqueness (Proposition 2.2), necessarily , and therefore is strictly natural.

In other words, . If we take the Grothendieck construction in both cases we get morphisms and . By uniqueness (Proposition 2.2), necessarily , and therefore is strictly natural.

Unitors and Associators

Left Unitor

Let be a diagram. We can apply to it the unit to form the diagram  corresponding to the following (rather trivial) lax cocone in with tip C.

corresponding to the following (rather trivial) lax cocone in with tip C. ![]() We view this as a lax cocone over the diagram which maps the unique object of to . If we form the Grothendieck construction as prescribed by the multiplication of the monad, we get the category which is isomorphic to , explicitly given as follows:

We view this as a lax cocone over the diagram which maps the unique object of to . If we form the Grothendieck construction as prescribed by the multiplication of the monad, we get the category which is isomorphic to , explicitly given as follows:

Objects are pairs , where is the unique object of and X is an object of ;

A morphism is simply a morphism of .

The functor maps then to DX and to Df in .

The functor given by is an isomorphism of categories. This defines an isomorphism of diagrams , in the category . Denote this isomorphism by . This is the map that we take as left unitor.

Proposition 2.4

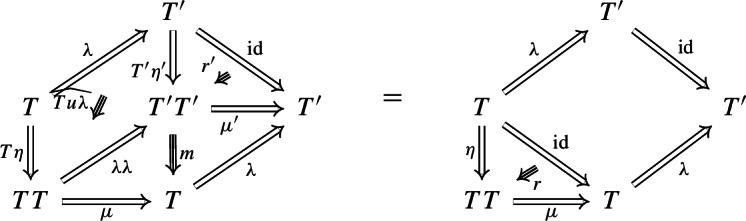

The map induces a modification .

Proof

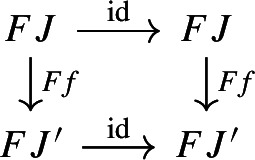

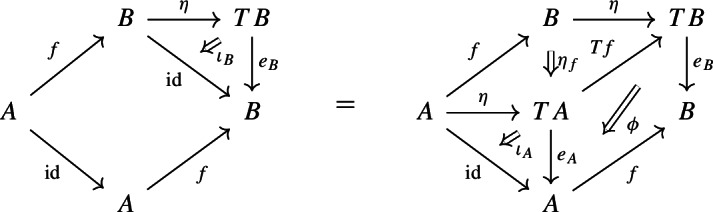

Let’s first show that is natural in the diagram D. If is a morphism of diagrams, it’s easy to see that this diagram commutes strictly,  where is the functor mapping to , and acting similarly on morphisms. This commutative diagram induces an analogous commutative diagram in , so that is a natural isomorphism of functors

where is the functor mapping to , and acting similarly on morphisms. This commutative diagram induces an analogous commutative diagram in , so that is a natural isomorphism of functors

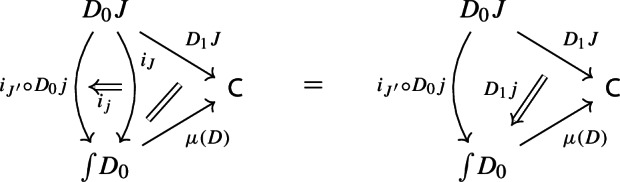

In order to show that is a modification, we have to show that is natural in the category as well, in the sense that for each functor the following composite 2-cells are equal,  where the squares without a 2-cell commute (by naturality).

where the squares without a 2-cell commute (by naturality).

Explicitly, we have to check that given a diagram , the following parallel functors coincide.  Note however that acts on the codomain of the diagram, by postcomposing with F, while acts on the domain of the diagram, mapping to its isomorphic copy . Therefore both arrows give the same morphism of diagrams, explicitly the following commutative diagram of ,

Note however that acts on the codomain of the diagram, by postcomposing with F, while acts on the domain of the diagram, mapping to its isomorphic copy . Therefore both arrows give the same morphism of diagrams, explicitly the following commutative diagram of ,  where , and the action on morphisms is similarly defined. Therefore is a modification.

where , and the action on morphisms is similarly defined. Therefore is a modification.

Right Unitor

Let be a diagram. This time we apply to it the map given by the functor image of under . Explicitly, the result is the following lax cocone in , with tip , indexed by via the constant functor at . In pictures,

If we form the Grothendieck construction, this time we get the category  which is again isomorphic to , explicitly given as follows:

which is again isomorphic to , explicitly given as follows:

Objects are pairs , where X is an object of and is the unique object of ;

A morphism is simply a morphism of .

The functor maps to DX and to Df in .

Analogously to the left unitor case, we have a functor given by which induces an isomorphism of categories. This defines in turn an isomorphism of diagrams , which we denote by (and its inverse by r. See Definition A.1 for the convention we are using). The map r is the one that we take as right unitor.

Proposition 2.5

The map r induces a modification .

We omit the proof, since it is analogous to the case of .

Associator

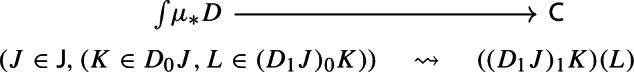

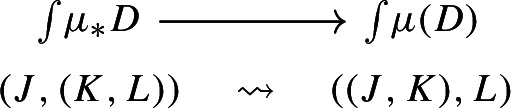

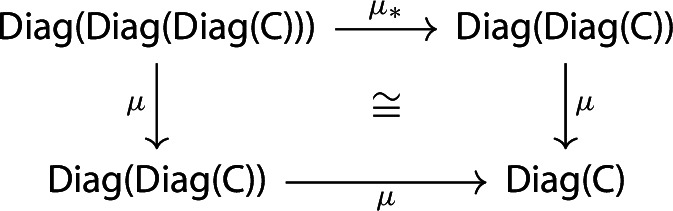

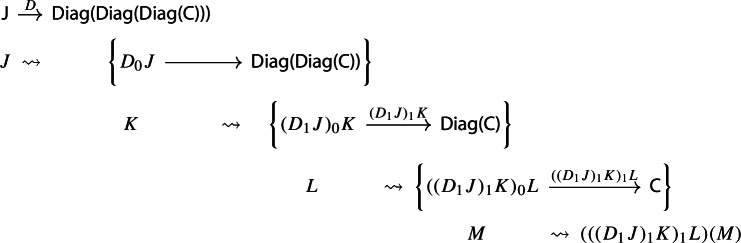

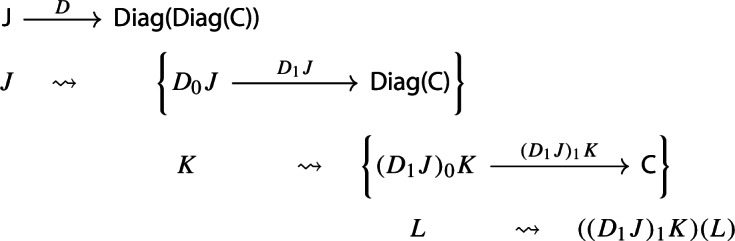

In order to define the associator, we have to look at . So let be a diagram which assigns to each object J of a diagram of diagrams , itself mapping the object K of to the diagram , which, in turn, maps an object L of to the object of . We could depict the situation as follows. For brevity we omit the action on morphisms, which is similarly constructed.  We can now take the Grothendieck construction at two different depths, which we can think of as “joining levels J and K” and “joining levels K and L”. The former way, which is , gives the following diagram of diagrams (only two levels).

We can now take the Grothendieck construction at two different depths, which we can think of as “joining levels J and K” and “joining levels K and L”. The former way, which is , gives the following diagram of diagrams (only two levels).  The latter way, which is , gives instead the following diagram of diagrams, which is in general not isomorphic to the former.

The latter way, which is , gives instead the following diagram of diagrams, which is in general not isomorphic to the former.  If we apply once again the Grothendieck construction to the two, we do obtain isomorphic diagrams:

If we apply once again the Grothendieck construction to the two, we do obtain isomorphic diagrams:  and

and  These are isomorphic as diagrams through the map

These are isomorphic as diagrams through the map  and so the following diagram commutes up to isomorphism.

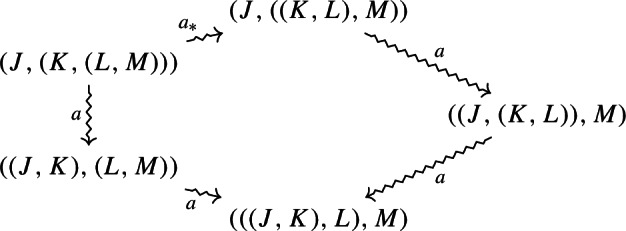

and so the following diagram commutes up to isomorphism.  We call this isomorphism the associator, and denote it by a. Again, analogously as for the unitors, we have:

We call this isomorphism the associator, and denote it by a. Again, analogously as for the unitors, we have:

Proposition 2.6

The associators assemble to a modification .

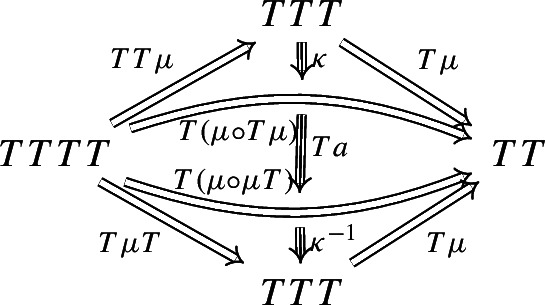

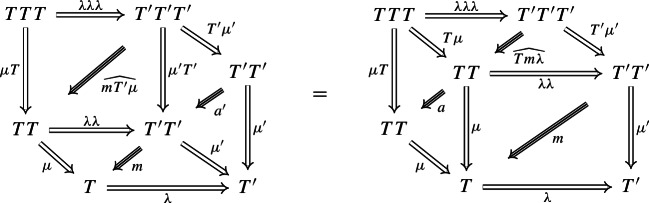

Higher Coherence Laws

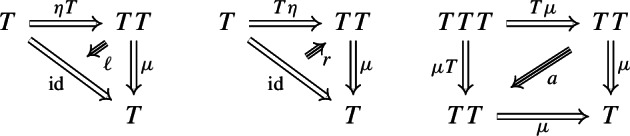

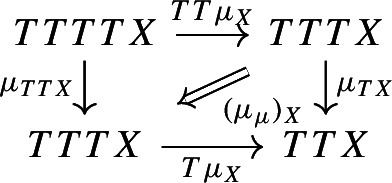

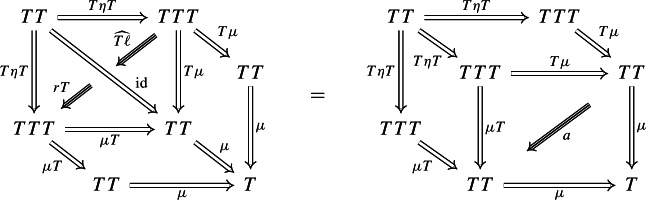

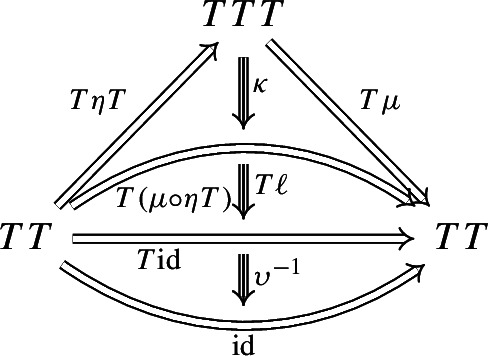

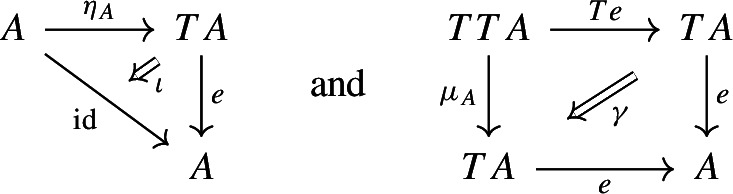

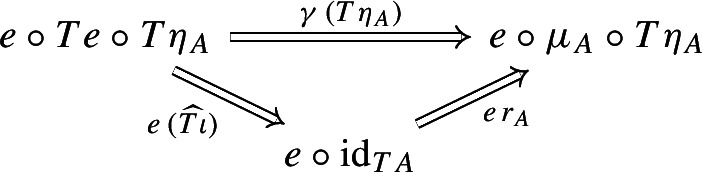

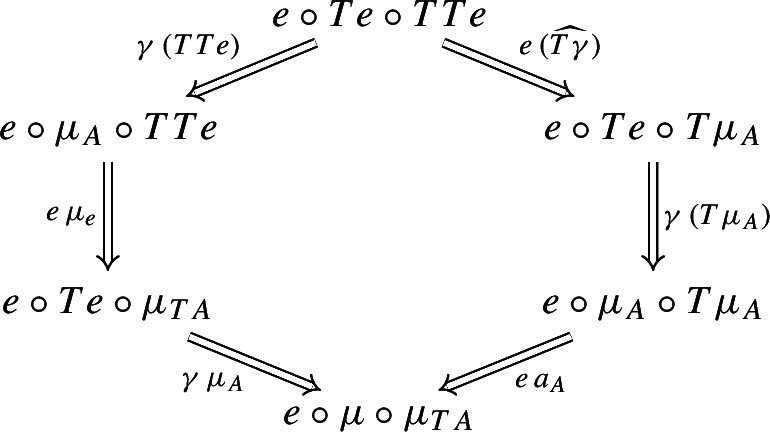

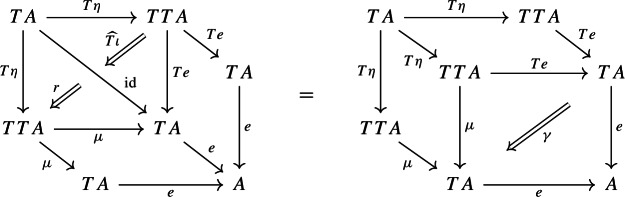

The associator and unitors satisfy coherence conditions that are analogous to the ones of monoidal categories (see Definition A.1 for the precise definition). We spell them out in detail for this case.

Unit Condition

Instantiating the unit condition of Definition A.1 in our case, we get the following statement, which reminds us of the unit condition of monoidal categories.

Consider a diagram of diagrams as follows.

Applying directly the Grothendieck construction we would have a diagram . However, we instead want to insert a “bullet” via the unitor, and this can be done in two ways.

Applying directly the Grothendieck construction we would have a diagram . However, we instead want to insert a “bullet” via the unitor, and this can be done in two ways.We can either apply the (inverse of the) left unitor at depth K, and then take the Grothendieck construction, obtaining the following diagram.

Alternatively, we can apply the right unitor r at depth J, and again take the Grothendieck construction, obtaining the following isomorphic diagram.

Now, not only are the two diagrams isomorphic, but the isomorphism relating them is exactly the associator,

which we can view as “rebracketing”.

which we can view as “rebracketing”.

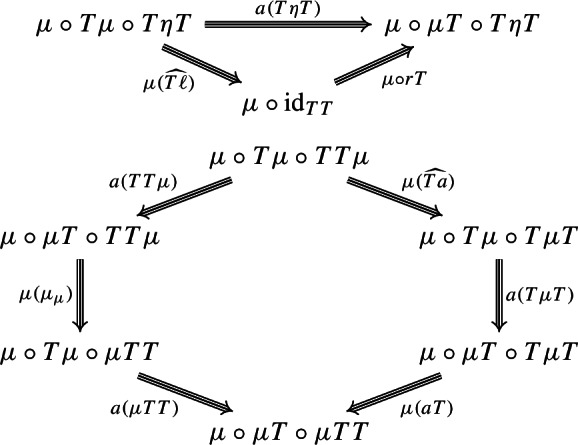

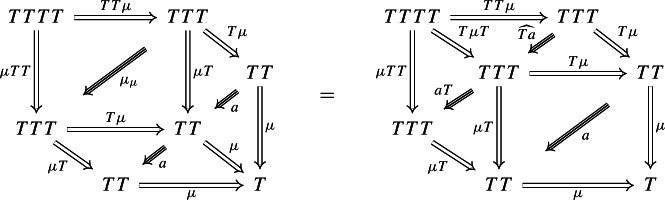

Pentagon Equation

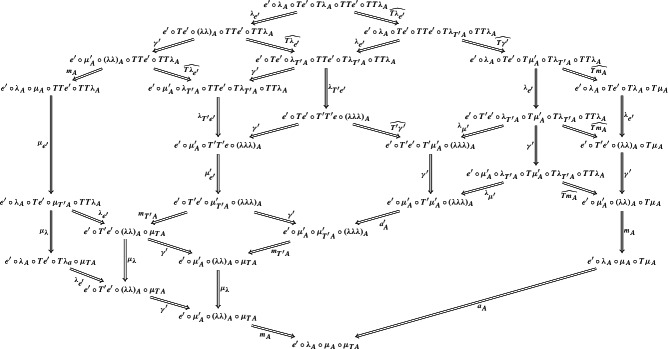

Instantiating the pentagon condition of Definition A.1 in our case, we get the following statement, which reminds us of the analogous condition for monoidal categories. Consider a four-level diagram, as follows.  There are several ways of obtaining a depth-one diagram via applying the Grothendieck construction three times, and they are related to one another via the associators. In particular, we can apply the Grothendieck construction repeatedly starting from the deepest (rightmost) level,

There are several ways of obtaining a depth-one diagram via applying the Grothendieck construction three times, and they are related to one another via the associators. In particular, we can apply the Grothendieck construction repeatedly starting from the deepest (rightmost) level,  or we can start from the outermost (leftmost) level.

or we can start from the outermost (leftmost) level.  There are now two ways of obtaining the former from the latter via associators, and they are equal. They are induced by the following rebracketings, which form a commutative pentagon (analogous to the one of monoidal categories).

There are now two ways of obtaining the former from the latter via associators, and they are equal. They are induced by the following rebracketings, which form a commutative pentagon (analogous to the one of monoidal categories).

Cocomplete Categories are Algebras

In this section we prove the following statements.

Theorem 2.7

Every cocomplete category equipped with a choice of colimit for each diagram has the structure of a pseudoalgebra over .

As shown in Sect. 2.5.4, the converse of the theorem does not hold: not all pseudoalgebras are in this form.

A definition of pseudoalgebra over a pseudomonad is given in Appendix A.

Structure Map

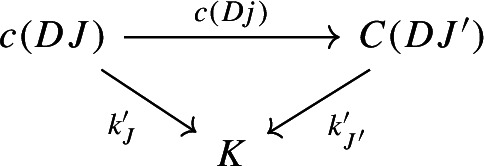

Let be a cocomplete category. For each diagram , choose a colimit (they are all isomorphic, pick one in each equivalence class). Let’s see why this construction is functorial. A colimit does not just consist of an object of , but also of the arrows of the colimiting cocone. Denote by c(D) the (chosen) colimit object of D, and by the colimiting cocone. In components, the cocone consists of arrows  for each object J of . Now consider a morphism of diagrams as follows.

for each object J of . Now consider a morphism of diagrams as follows.  Using and the colimit cocone we can construct a cocone under D, with tip : the one of components

Using and the colimit cocone we can construct a cocone under D, with tip : the one of components  for each J of . This cocone must then factor uniquely through c(D) by the universal property of c(D) as a colimit:

for each J of . This cocone must then factor uniquely through c(D) by the universal property of c(D) as a colimit:  Denote the resulting map by . It is the unique map that makes the diagram above commute for each J of . By uniqueness, this assignment preserves identities and composition, and so c is a functor . Technically speaking, for each diagram one can choose many possible colimits within the same equivalence class. However, once c(D) and are fixed, the map is unique. So any choice of such colimit objects gives rise to a functor, and all these functors will be naturally isomorphic, again by uniqueness.

Denote the resulting map by . It is the unique map that makes the diagram above commute for each J of . By uniqueness, this assignment preserves identities and composition, and so c is a functor . Technically speaking, for each diagram one can choose many possible colimits within the same equivalence class. However, once c(D) and are fixed, the map is unique. So any choice of such colimit objects gives rise to a functor, and all these functors will be naturally isomorphic, again by uniqueness.

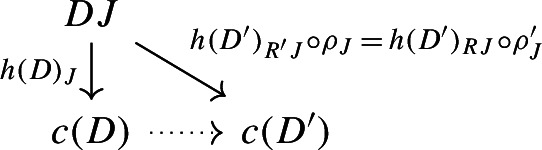

We can say even more: the map is even 2-functorial if we view as a 2-category (as in Definition 2.1), and (which is a 1-category) as a locally discrete 2-category. This is made precise by the following lemma.

Lemma 2.8

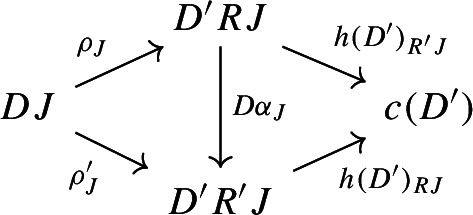

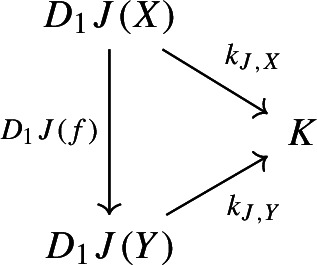

Let be a cocomplete category and a choice of colimit for each diagram. Consider diagrams and in , morphisms of diagrams , and suppose there exists a 2-cell of diagrams . Then .

Proof

Recall that consists of a natural transformation such that  This way, for each object J of , the following diagram commutes,

This way, for each object J of , the following diagram commutes,  where denotes the colimit cone of under . The maps and are both defined as the unique maps making the following diagram commute,

where denotes the colimit cone of under . The maps and are both defined as the unique maps making the following diagram commute,  and are therefore equal.

and are therefore equal.

Structure 2-Cells

We now give the structure 2-cells of the pseudoalgebras, namely the unitor and the multiplicator.

Lemma 2.9

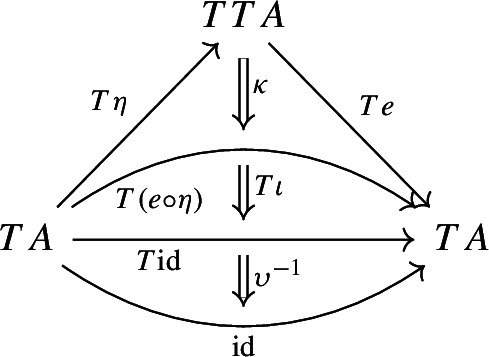

The following diagram commutes up to a canonical natural isomorphism.

We denote the natural isomorphism by .

Proof

Let C be an object of . The diagram is the one-object diagram whose unique node is given by C. A colimit cocone over consists of an object together with a specified isomorphism . Therefore, for any choice of c, we get canonically an isomorphism . The maps assemble to a natural isomorphism , since for each of the following diagram commutes,  since the map is defined (by definition of how c acts on morphisms) as the unique map making the diagram above commute.

since the map is defined (by definition of how c acts on morphisms) as the unique map making the diagram above commute.

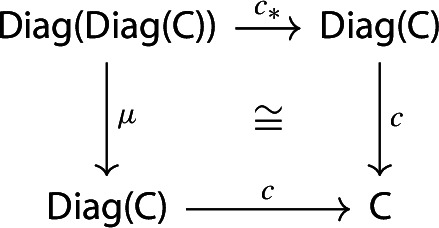

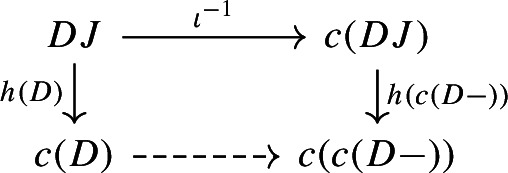

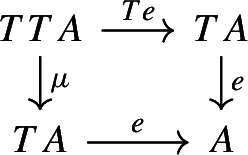

Lemma 2.10

The following diagram commutes up to a canonical natural isomorphism.

Denote the natural isomorphism by .

This statement is known in the literature, see for example [4, Section 40], as well as [26, Theorem 3.2]. Here we present a direct proof. In the proof we can see how the objects in the top right corner of the square are, in some sense, partial colimits of the objects in the bottom left corner. This will be made precise in Sect. 5.

Proof

Let . The diagram is given by the following postcomposition.  In other words, the nodes of D are diagrams (one for each object of ), and replaces them by their (chosen) colimit, obtaining a diagram in indexed by .

In other words, the nodes of D are diagrams (one for each object of ), and replaces them by their (chosen) colimit, obtaining a diagram in indexed by .

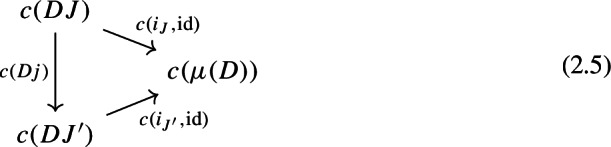

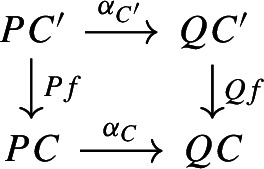

Recall that is given by the Grothendieck construction, so that is a diagram obtained by the union of the diagrams DJ for each J of , plus additional arrows between those subdiagrams, induced by the morphisms of . Specifically, for every morphism of and for every of , the following square commutes.  The object is a colimit of the resulting diagram involving all the j and the f as above. Recall now the universal property of the Grothendieck construction, and in particular diagrams (2.1) and (2.2). For each object J of , the morphism of diagrams given by the inclusion of the fiber over J,

The object is a colimit of the resulting diagram involving all the j and the f as above. Recall now the universal property of the Grothendieck construction, and in particular diagrams (2.1) and (2.2). For each object J of , the morphism of diagrams given by the inclusion of the fiber over J,  induces a map between their (chosen) colimits . The maps , for each J, assemble to a cocone under , with tip , meaning that for each morphism of , the following diagram commutes.

induces a map between their (chosen) colimits . The maps , for each J, assemble to a cocone under , with tip , meaning that for each morphism of , the following diagram commutes.  Indeed, we can rewrite (2.2) as follows,

Indeed, we can rewrite (2.2) as follows,  which is exactly the condition for a 2-cells of diagrams (see Definition 2.1). By Lemma 2.8, then, , which means that (2.5) commutes.

which is exactly the condition for a 2-cells of diagrams (see Definition 2.1). By Lemma 2.8, then, , which means that (2.5) commutes.

As we said, the maps , assemble to a cocone under , with tip . Therefore, by the universal property of as a colimit, there exists a unique arrow , which we denote by , making the following diagram commute for all J of ,  where the denote the arrows of the colimiting cocone. Note that for each object X of we can extend the diagram above to the following commutative diagram,

where the denote the arrows of the colimiting cocone. Note that for each object X of we can extend the diagram above to the following commutative diagram,  where and are the components at X of the colimiting cocones of c(DJ) and .

where and are the components at X of the colimiting cocones of c(DJ) and .

To show that is an isomorphism, we invoke the Yoneda embedding. Let K be any object of . We want to show that the function  which is natural in K, is a bijection. To this end, we note that by the universal property of colimits, the set on the left is naturally isomorphic (via composing with the components of ) to the subset

which is natural in K, is a bijection. To this end, we note that by the universal property of colimits, the set on the left is naturally isomorphic (via composing with the components of ) to the subset

whose elements are families of arrows such that for each of and each of the following diagram commutes.  Now, for each J of , the quantity appearing in S given by

Now, for each J of , the quantity appearing in S given by

and whose elements are arrows such that of the following diagram commutes,  is in natural bijection with

is in natural bijection with

by universal property of the colimit, via composing with the cocones h(DJ). In other words, S is in natural bijection with the subset of

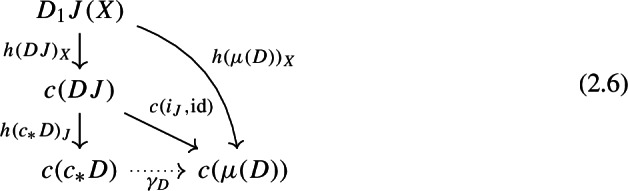

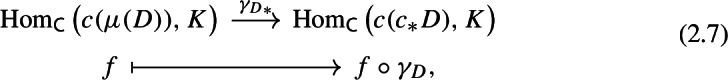

whose elements are arrows such that the following diagram commutes.  The subset , again by the universal property of the colimit, is in bijection (via composing with ) with , which is exactly at the right side of (2.7). Since (2.6) commutes, composing with has the same effect as applying the bijections given by (the inverse of) composing with and (all the bijections are invertible), and then composing with . Therefore (2.7) is a bijection too. By the Yoneda lemma, then, is an isomorphism.

The subset , again by the universal property of the colimit, is in bijection (via composing with ) with , which is exactly at the right side of (2.7). Since (2.6) commutes, composing with has the same effect as applying the bijections given by (the inverse of) composing with and (all the bijections are invertible), and then composing with . Therefore (2.7) is a bijection too. By the Yoneda lemma, then, is an isomorphism.

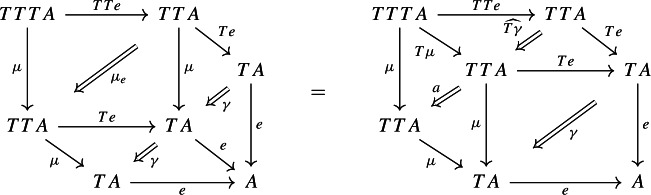

Coherence Laws

In order to prove Theorem 2.7 it remains to be checked that the unit and multiplication coherence conditions of Definition A.4 hold. Intuitively, such coherence conditions hold by the “uniqueness property of maps between colimits”. In other words, not only do objects satisfying the same universal property admit an isomorphism between them, but they admit a unique one compatible with the universal property (in our case, the cocone): while colimit objects of a diagram may have many automorphisms (as objects), colimit cocones over the same diagram form a contractible groupoid.

Let’s see this more explicitly. The unit condition of Definition A.4, instantiated in our case, says the following. Let be a cocomplete locally small category, and construct (choose) the functor as before. Consider now a diagram . We can apply the map as in Sect. 2.3.2 and obtain the diagram as follows.  Now we can either

Now we can either

apply to the map , which replaces each one-object diagram DJ with its chosen colimit c(DJ) (isomorphic to DJ via the unitor ), giving the diagram ; or

form the Grothendieck construction and obtain the diagram , with exactly the same image in as D, but indexed by a nominally different category, and isomorphic to D via the counit .

Both ways give isomorphic diagrams in , which then have isomorphic colimits. The isomorphism between the colimits can be written a priori in two ways:

It is the one induced by ;

It is the one induced by the isomorphism of diagrams of components for each object J of .

The unit condition of pseudoalgebras says that these two isomorphism should be equal. This is indeed the case, by uniqueness of the morphism : forming the colimit cocones of D and of , which are isomorphic diagrams via , we have a unique morphism making the following diagram commute for all J of ,  which can be seen as either the map (by definition), or as the map induced by , after suitably translating D into via the right unitor r.

which can be seen as either the map (by definition), or as the map induced by , after suitably translating D into via the right unitor r.

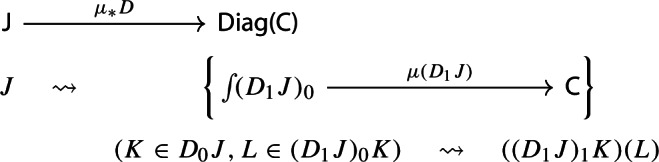

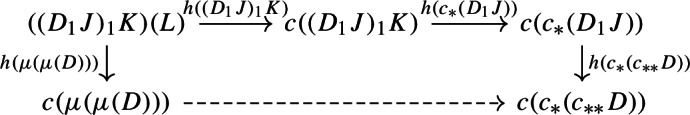

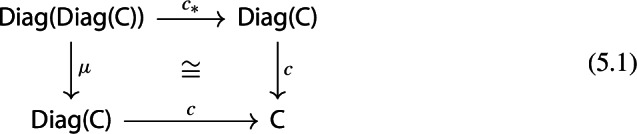

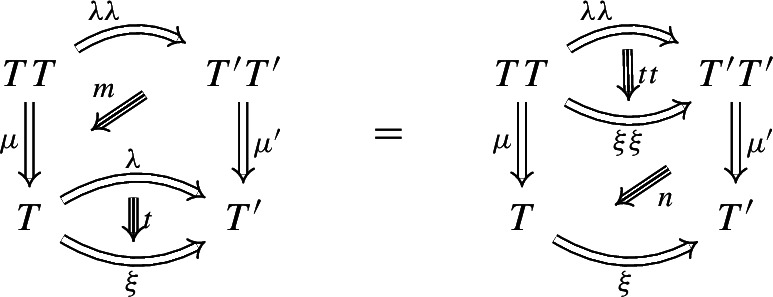

The multiplication condition of Definition A.4, again instantiated in our case, says the following. As in Sect. 2.3.3, let be a diagram as follows.  We can now take the colimit progressively, a priori in two ways: first of all, “from the inside out”, that is,

We can now take the colimit progressively, a priori in two ways: first of all, “from the inside out”, that is,

For each J of and K of , take the (chosen) colimits of the diagrams , obtaining the following diagram of diagrams;

Then, for each J of , take the (chosen) colimit of the remaining innermost level diagram , obtaining the following diagram;

Finally, take the colimit of the diagram just obtained.

Alternatively, we could

Form the Grothendieck construction of D joining levels J and K, obtaining the following diagram of diagrams;

Form again the Grothendieck construction, joining level L as well;

Finally, take the colimit of the resulting diagram.

The colimits constructed this way are isomorphic, a priori, in two different ways, using the maps obtained by in different orders (first inner level, then outer, or vice versa). However, the different ways coincide, since both colimits come equipped with the following cocones,  and there is a unique map making the diagram above commute for all J, K and L.

and there is a unique map making the diagram above commute for all J, K and L.

This finally proves that cocomplete categories are pseudoalgebras of (Theorem 2.7).

Not All Algebras are of this Form

We now want to show the following statement.

Proposition 2.11

Not every pseudoalgebra over is in the form of Theorem 2.7.

We use the following known result [26, Theorem 2.7].

Theorem 2.12

Let be a cocomplete category. Then the category is cocomplete too. Moreover, the functor which assigns to each diagram its domain preserves colimits.

We are now ready to prove the proposition. We will prove it by showing that for free pseudoalgebras, in the form , the map is in general not taking colimits of diagrams (of diagrams).

Proof of Proposition 2.11

Let be a cocomplete category with at least two non-isomorphic objects X and Y and a morphism . Consider now the morphism of , which can be seen as the morphism of diagrams,  and so, in particular, also as a diagram of diagrams (indexed by the walking arrow ). Denote by this diagram of diagrams. We have that , as given by the Grothendieck construction, is a diagram indexed again by . Instead, by Theorem 2.12, the colimit of D in is a diagram whose domain must be the colimit of in , which is . In particular, this colimit is not isomorphic to .

and so, in particular, also as a diagram of diagrams (indexed by the walking arrow ). Denote by this diagram of diagrams. We have that , as given by the Grothendieck construction, is a diagram indexed again by . Instead, by Theorem 2.12, the colimit of D in is a diagram whose domain must be the colimit of in , which is . In particular, this colimit is not isomorphic to .

Therefore, for the free algebra , the algebra structure map is not in the form of Theorem 2.7. (See the end of Appendix A.2 for why is indeed a pseudoalgebra.)

A structural reason for why not all -algebras arise this way will be given in Sect 4.6.1. Conjecturally, the generic -algebras may be given by taking oplax colimits, instead of strict (in 2-categories rather than categories).

Image Presheaves

In this section we define the notion of image presheaf of a diagram, which may be interpreted as its “free” or “prototype colimit”. As far as we can tell, it was first introduced by Paré under the name “connected component functor” [23]. This concepts allows to extend and generalize the theory of cofinal functors (which we call confinal, see Sect 3.2), giving conditions for when certain diagrams have isomorphic colimits even after applying a functor to them (Proposition 3.9), and it incorporates absolute colimits as a special case (see Proposition 3.13 and the subsequent discussion).

Diagrams and Presheaves

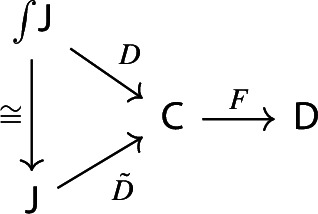

Given a diagram , we obtain a presheaf on canonically, as follows.

Definition 3.1

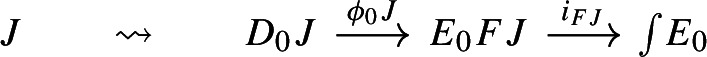

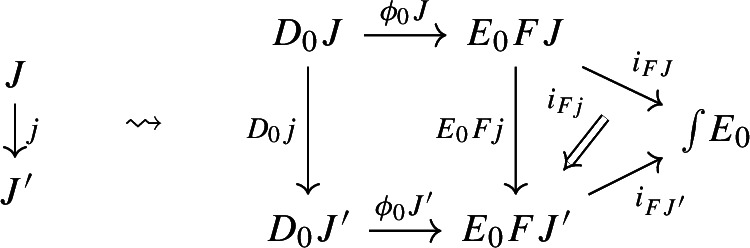

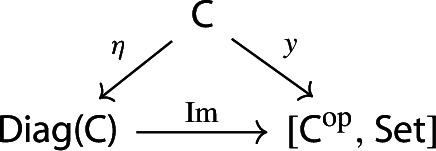

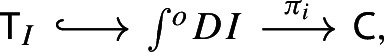

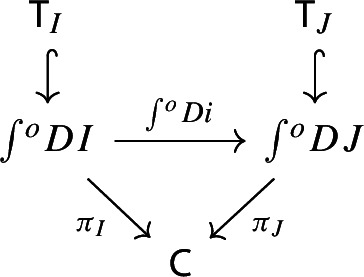

The image presheaf of the diagram D, which we denote by , is the colimit of the following composite functor, ![]() where y denotes the Yoneda embedding.

where y denotes the Yoneda embedding.

We can view the image as a “free colimit”, the presheaf obtained as the colimit of representables indexed by the diagram D. As usual, by the universal property of colimits this assignment is functorial. The terminology “image” is motivated by a factorization (see Sect 3.2.1), as well as by analogy with random variables (see Sect 5.4).

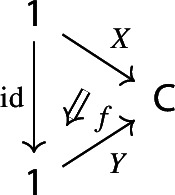

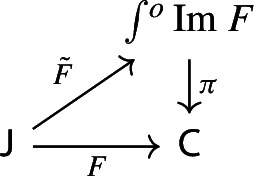

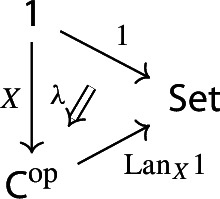

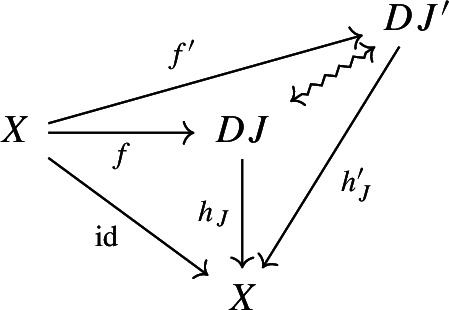

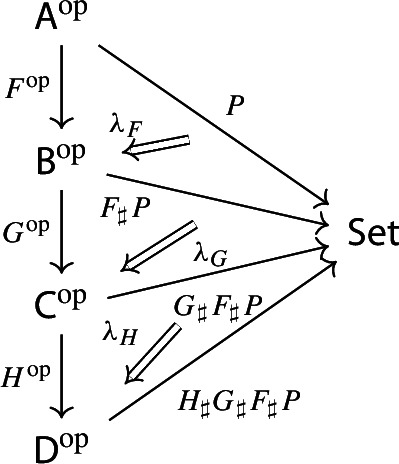

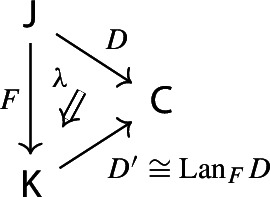

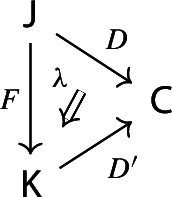

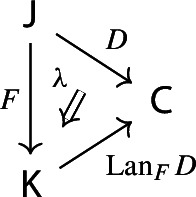

Equivalently, is the (pointwise) left Kan extension

as in the following diagram,  where is the constant presheaf at the singleton set 1, and denotes the universal 2-cell. This way one could generalize the definition to the case of weighted diagrams, which is however beyond the scope of the present paper.

where is the constant presheaf at the singleton set 1, and denotes the universal 2-cell. This way one could generalize the definition to the case of weighted diagrams, which is however beyond the scope of the present paper.

Concretely, given an object C of , the set is the set

Its elements are the equivalence classes of arrows of of the form , for some object J of , where we identify any two arrows and whenever there exists a morphism of such that , as in the following diagram.  Functoriality of , as a functor , is given by pasting arrows and commutative diagrams.

Functoriality of , as a functor , is given by pasting arrows and commutative diagrams.

In general, two arrows and are identified if there is a zig-zag of arrows of connecting J and , which we write as , such that the following diagram “commutes”.  By convention, we say that a triangle containing a zig-zag as the one above commutes if and only if each arrow in the zig-zag gives a commutative triangle. For later use, we denote by [J, f] the equivalence class in represented by .

By convention, we say that a triangle containing a zig-zag as the one above commutes if and only if each arrow in the zig-zag gives a commutative triangle. For later use, we denote by [J, f] the equivalence class in represented by .

This description in terms of equivalence classes of arrows can be stated more concisely as follows: the presheaf applied to the object C is the set of connected components of the comma category C/D. This is how this construction was first introduced (for small categories) in [23, Section 2], where it is called the “connected component functor” or . The equivalence of the two definitions is already proven in [23, Theorem 2.1].

The Category of Elements

Let be a presheaf. Recall the discrete fibration given by the category of elements

Note that we use again the short integral sign, as we had used for the Grothendieck construction – but here it denotes the category of elements, as we are using the contravariant version. The category is the category where

Objects consist of pairs (C, x), where C is an object of and is an element of the set PC.

A morphism is a morphism of such that the function sends to .

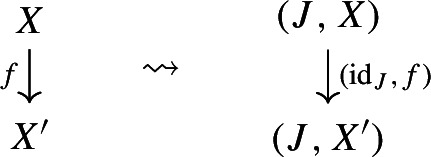

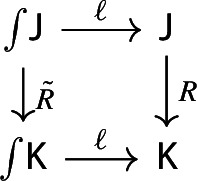

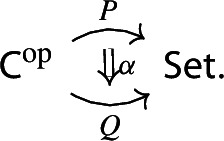

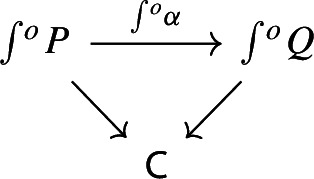

If C is small (resp. locally small), is small too (resp. locally small). The functor , which is a discrete fibration, maps (C, x) to C and a morphism of to the underlying morphism of C. The category of elements is functorial in the following way. Let be a morphism of presheaves, i.e. a natural transformation  we can construct a functor which makes the following diagram commute,

we can construct a functor which makes the following diagram commute,  where the morphisms into are the canonical discrete fibrations. The functor is constructed as follows.

where the morphisms into are the canonical discrete fibrations. The functor is constructed as follows.

It maps the object (C, p), where C is an object of and , to the object . Note that ;

It maps the morphism induced by the morphism of to the morphism again induced by f. Note that the following naturality diagram commutes.

Consider now a diagram , take its image presheaf and form its category of elements . Let’s see what we get explicitly.

An object of consists of an object C of together with an equivalence class [J, f] represented by an object J of and a morphism of .

A morphism consists of a morphism of such that . This means that there is a zig-zag of arrows of connecting J and , which we write as , such that the following diagram commutes.

Proposition 3.2

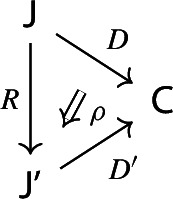

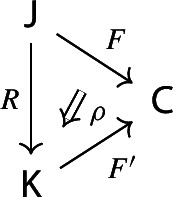

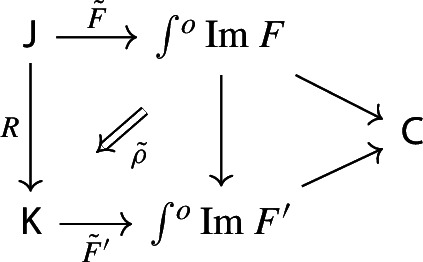

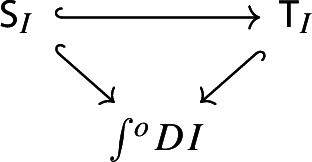

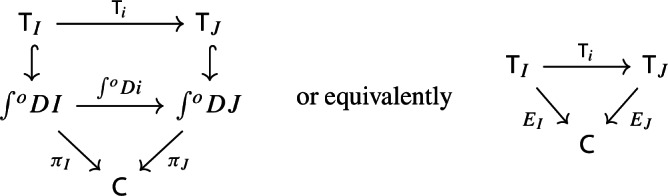

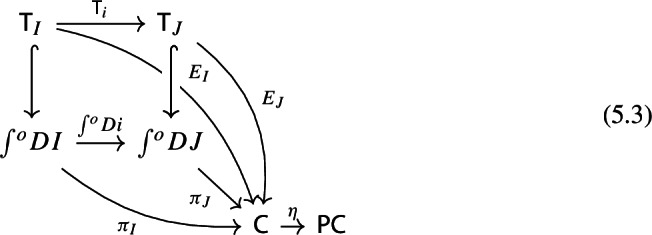

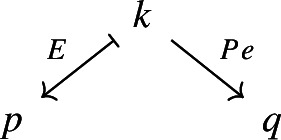

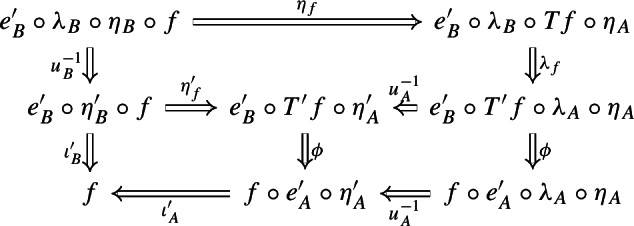

Given a morphism of diagrams  the 2-cell factors in the following form,

the 2-cell factors in the following form,  where the triangle on the right commutes, with the vertical arrow given by (recall that both and are functorial).

where the triangle on the right commutes, with the vertical arrow given by (recall that both and are functorial).

Before the proof, let’s see what the functor looks like. It maps an object

of to the object

of . On morphisms, given in and a zig-zag in making the diagram on the left commute, we get the diagram on the right.  The right-most square commutes by naturality of applied to the zig-zag.

The right-most square commutes by naturality of applied to the zig-zag.

Proof

Let J be an object of . Let’s give the component of at J explicitly. Note first that

and that

The morphism is then given by the following diagram,  with the zig-zag given by the identity. By construction, whiskering with the forgetful functor to we get back .

with the zig-zag given by the identity. By construction, whiskering with the forgetful functor to we get back .

Connecting Confinal Functors and Absolute Colimits

As shown in [23, Section 3], the concept of image presheaf allows us to extend a bit the theory of confinal functors,2 and unifies it with the theory of absolute colimits. Here we restate some of those ideas, since we have slightly different size conditions. A reference for the standard theory is for example given in [2, Section 2.11] (note that there the term “final functor” is used instead, for limit-invariant functors, rather than colimit-invariant).

Definition 3.3

A functor is called confinal if for every object D of , the comma category D/F is non-empty and connected.

Note that, if we view F as a (possibly large) diagram, for an object D of can be seen as the set of connected components of D/F. Therefore F is confinal if and only if is the terminal presheaf. (See also [23, Corollary 3.4].)

The importance of confinal functors is due to the following well-known statement, which is actually an equivalent characterization of confinality.

Proposition 3.4

If is confinal, for every functor admitting a colimit, the functor admits a colimit too, and the map between colimits

induced by the following morphism of (possibly large) diagrams  is an isomorphism.

is an isomorphism.

For a proof, see for example the proof of the very similar statement [2, Proposition 2.11.2] (again, note the different conventions there).

Refining the Comprehension Factorization

We would like now to prove the following statement.

Proposition 3.5

Let be (small-)cocomplete. The (large) colimit of the fibration

exists, and it coincides with the (small) colimit of the diagram .

This is almost an instance of the following known result, sometimes called the “comprehension factorization schema”.

Theorem 3.6

[28] There is an orthogonal (E, M)-factorization system on , where E are the confinal functors and M are the discrete fibrations.

However, in our case we are not requiring to be small, only locally small. Because of this, and because we need the construction explicitly, we give a dedicated proof. We construct a functor as follows.

- For each object J of , define

i.e. assign to J the equivalence class represented by the identity arrow of . For each morphism , take the map . Notice that we have the following commutative diagram,

so that we have a well-defined morphism of (the zig-zag is simply given by the morphism f).

so that we have a well-defined morphism of (the zig-zag is simply given by the morphism f).

Proposition 3.7

The functor is confinal.

This suffices to deduce Proposition 3.5, since the following diagram commutes.

Proof of Proposition 3.7

We need to show that for every object (C, [J, f]) of , the comma category is non-empty and connected. This is guaranteed by the way the category is constructed, as follows.

First, since is the equivalence class represented by the identity , we can consider f as an arrow of and, hence, an object of , as we have the trivially commuting diagram  with the zig-zag given by the identity. Now, given any other arrow in , we have . So there is a zig-zag in , which actually links with f in the comma category , as required.

with the zig-zag given by the identity. Now, given any other arrow in , we have . So there is a zig-zag in , which actually links with f in the comma category , as required.

Mutually Confinal Diagrams

We will make use of the following well-known fact:

Lemma 3.8

Consider the functors ![]() where , and are locally small categories. If is confinal and G is fully faithful, then F and G separately are confinal too.

where , and are locally small categories. If is confinal and G is fully faithful, then F and G separately are confinal too.

Proposition 3.9

Let be a locally small category. Let and be small diagrams. The following conditions are equivalent.

and are naturally isomorphic;

for every locally small category and every functor , the composite diagram admits a colimit if and only if does, and in that case the two colimits are isomorphic;

D and E are connected by a zigzag in such that all the arrows of the underlying zigzag in are confinal functors.

Definition 3.10

If the diagrams and satisfy any (and, hence, all) of the conditions above, we call them mutually confinal.

One should view the property of being mutually confinal as the absolute coincidence of their colimits: existence granted, their colimits remain the same even after applying any other functor.

This idea, minus the size issues, appears already in [23, Theorem 3.2].

Proof of Proposition 3.9

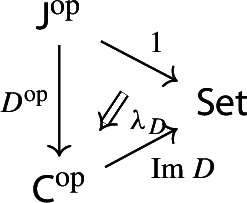

The statement (c)(b) is part of the standard theory of confinal functors (see the references). The statement (b)(a) follows from choosing for the Yoneda embedding .

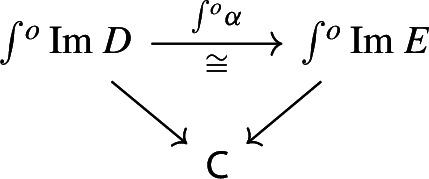

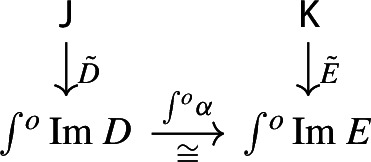

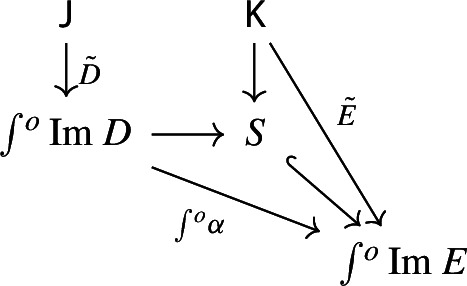

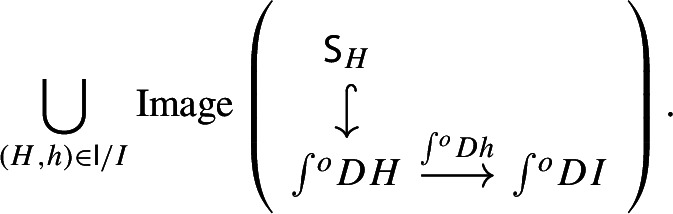

The real work is to prove (a)(c). To this end, suppose that is an isomorphism . We have an isomorphism between the corresponding categories of elements,  together with functors and which are confinal by Proposition 3.7. We have the following diagram of confinal functors.

together with functors and which are confinal by Proposition 3.7. We have the following diagram of confinal functors.  Denote now by the full subcategory of given by the joint full image of the two functors and . The situation is depicted in the following commutative diagram.

Denote now by the full subcategory of given by the joint full image of the two functors and . The situation is depicted in the following commutative diagram.  By construction, S is small, since its cardinality is bounded by the one of the disjoint union of the sets of objects of and , which are small. Moreover, the resulting functors and are confinal by Lemma 3.8. The resulting diagram

By construction, S is small, since its cardinality is bounded by the one of the disjoint union of the sets of objects of and , which are small. Moreover, the resulting functors and are confinal by Lemma 3.8. The resulting diagram  gives the desired zigzag (of length 2).

gives the desired zigzag (of length 2).

Absolute Colimits

An absolute colimit is a colimit which is preserved by every functor [24]. We can redefine the concept of absolute colimits in terms of mutually confinal functor as follows. As we will see, this is equivalent to the usual definition. Again, these ideas, minus size issues, already appear in [23], see Corollary 3.3 therein and the subsequent discussion.

Definition 3.11

Let be a locally small category, and let be a small diagram. An absolute colimit of D is an object X of such that the diagrams and are mutually confinal.

The image presheaf of a one-object diagram is the one given by the Yoneda embedding , as the following proposition show.

Proposition 3.12

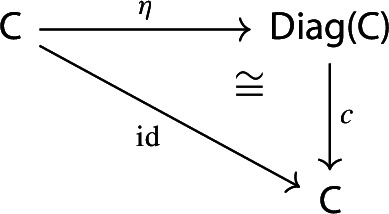

For each locally small category , the following diagram commutes up to natural isomorphism.

Proof

Using the definition of image in terms of Kan extensions, and recalling that is the diagram that picks out the object X, we have that is given by the following Kan extension,  which is isomorphic to , i.e. the image of X under the Yoneda embedding. The isomorphism is moreover natural in X, by the universal property of (free) colimits.

which is isomorphic to , i.e. the image of X under the Yoneda embedding. The isomorphism is moreover natural in X, by the universal property of (free) colimits.

Therefore, equivalently, an object X is an absolute colimit of the diagram if and only if is naturally isomorphic to the representable presheaf .

If we instance Proposition 3.9 for this case, we get the following statement.

Proposition 3.13

Let be a locally small category. Let and be a small diagram, and let X be an object of . The following conditions are equivalent.

X is an absolute colimit of D (i.e. naturally);

for every locally small category and every functor , the object F(X) is the colimit in of the composite diagram ;

and are connected by a zigzag in such that all the arrows of the underlying zigzag in are confinal functors.

Note that condition (b) implies, in particular, that indeed X is a colimit of D (take F to be the identity). Denote the colimit cone by .

We can now rewrite condition (c) in a more elementary way. Recall that in the proof of Proposition 3.9 we had obtained condition (c) from (a) by forming the category of elements of the (common) image presheaf, and taking the joint image of the confinal functors from and from to this category of elements. The category of elements of the representable presheaf is isomorphic to the slice category . We therefore have to take the joint image in of the two functors at the top of this diagram,  where the functor maps an object to the arrow of the colimit cone . Just as in the proof of Proposition 3.9, denote this joint full image by . Now, the resulting functor is trivially confinal, since it maps the unique object of to . More interestingly, the proof of Proposition 3.9 says that also the resulting functor is confinal. The condition is nontrivial for the only object of that does not come from , which is the one coming from , namely . For this object, the confinality condition of the functor says the following:

where the functor maps an object to the arrow of the colimit cone . Just as in the proof of Proposition 3.9, denote this joint full image by . Now, the resulting functor is trivially confinal, since it maps the unique object of to . More interestingly, the proof of Proposition 3.9 says that also the resulting functor is confinal. The condition is nontrivial for the only object of that does not come from , which is the one coming from , namely . For this object, the confinality condition of the functor says the following:

-

(d)

There exist an object J of and an arrow of such that the following diagram commutes:

and such that moreover, for each object of and arrow making a similar diagram commute, there exists a zigzag in making the following diagram in commute.

and such that moreover, for each object of and arrow making a similar diagram commute, there exists a zigzag in making the following diagram in commute.

Intuitively, we can interpret this condition as “the colimit cone eventually has a section, which is in some sense unique”. This is similar to very well-known statements in the literature, see for example Theorems 2.1 and 4.1 in [24]. Therefore we can view our theory of mutually confinal functors as a joint generalization both of confinal functors and of absolute colimits.

The Monad of Small Presheaves

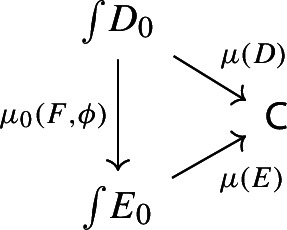

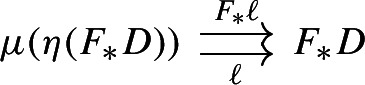

In this section we study small presheaves, and show that they also form a pseudomonad. Moreover, the image map of the previous section gives a morphism of pseudomonads (also explicitly defined in Appendix A). Again, cocomplete categories are pseudoalgebras of this monad, but this time, every pseudoalgebra is of this form. Indeed, considering the long history of (co)completion theory of categories (see [14, 18] for early contributions), one should view the monad of small presheaves as the “free small-cocompletion monad”. The fact that admits cocomplete categories as algebras is then to be thought of as an instance of the “restriction of scalars” construction, where algebras of a monad can be pulled back along a morphism of monads, see Appendix A.3.

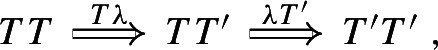

It is known that small presheaves form a pseudomonad [6]. However, we did not find an explicit construction in the literature, so we give one in the present section. Compared to the pseudomonad of Sect. 2, this one is weaker: the underlying pseudofunctor is not a strict 2-functor. A short review of the relevant basic definitions can be found in Appendix A. The fact that defines a morphism of pseudomonads (Sect. 4.6) seems to be new.

Small Presheaves

Definition 4.1

A presheaf is called small if it is (naturally isomorphic to) the image presheaf of a small diagram.

Denote by the full subcategory of whose objects are small presheaves.

The image presheaf of a (small) diagram is by definition a small presheaf, so that the functor actually lands in . We denote the resulting functor again by . This will not cause confusion, since from now on we will only consider small presheaves.

Despite the slightly new terminology, this is a known concept, see for example [6]. We recall the following facts.

A presheaf is small if and only if it can be written as a small colimit of representables [6, Section 2]. Therefore we can think of small presheaves as of forming the free small cocompletion of a category.

The category of small presheaves on a locally small category is itself locally small. This allows us to avoid several size issues when talking about the free cocompletion.

Notice also the following fact.

Remark 4.2

Let be a locally small category, and let be a small presheaf. Then we know (Proposition 3.7) that there exist a small category and a confinal functor . By Lemma 3.8, we can assume that is fully faithful, or equivalently that it is the inclusion of a full subcategory.

For later use in this section, we recall the following known statement, sometimes called the co-Yoneda lemma (see [15, Section 3.10], as well as [19, Section 2.2]).3

Proposition 4.3

Let be a category, and let be a functor. There is an isomorphism

for each object C of and natural in C, given by mapping each element to the equivalence class in the coend above the ordered pair .

The Pseudofunctor

Given locally small categories and and a functor , we would like to find an assignment , which maps small presheaves to small presheaves.

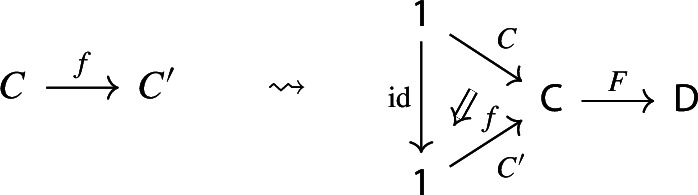

Definition 4.4

Let be a functor between locally small categories, and let P be a small presheaf on . The pushforward of

P

along

F is the presheaf on given by the following left Kan extension.  We denote the resulting presheaf by .

We denote the resulting presheaf by .

Equivalently, is given by the free colimit of F, weighted by P. By the universal property of (weighted) colimits, it is therefore functorial in F. Note that this definition specifies only up to isomorphism. As usual, the choice of a particular object within its isomorphism class is de facto irrelevant.

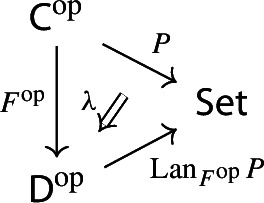

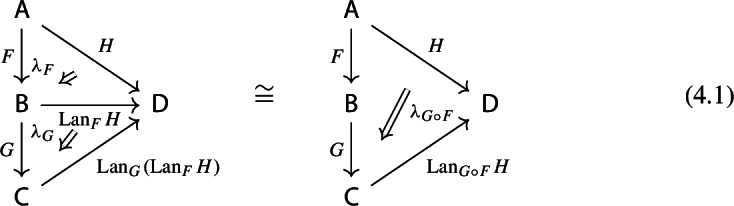

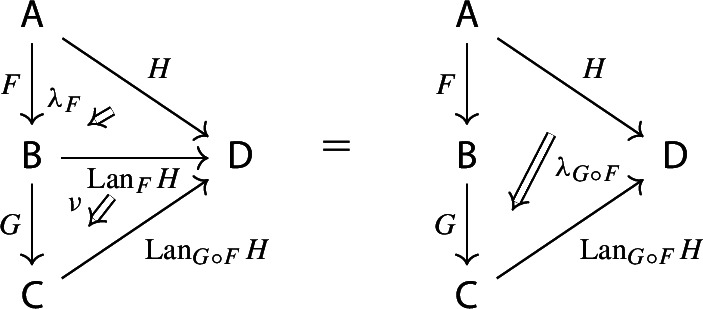

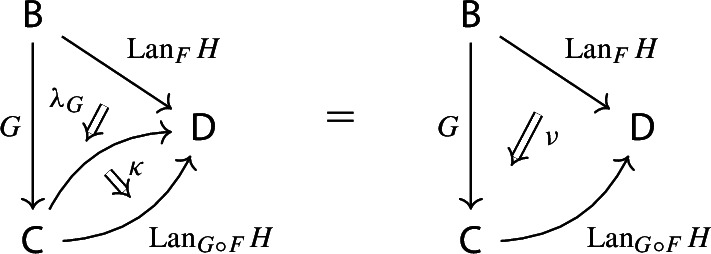

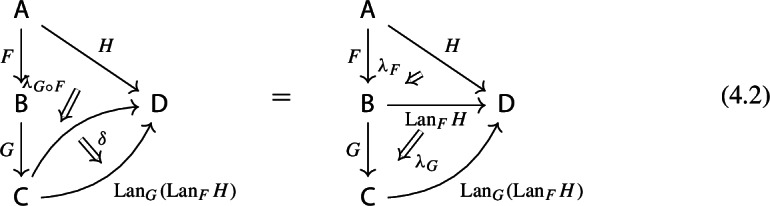

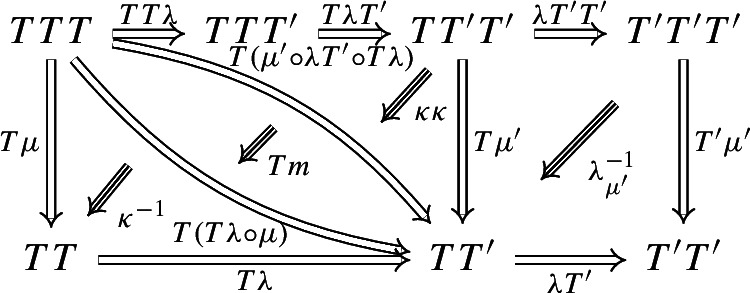

Recall the following fact, which says that Kan extension diagrams can be pasted vertically. While the statement is folklore and a consequence of the simple fact that universal arrows [21] compose in an obvious sense, we provide a proof because the explicit isomorphism given in the proof will be of use later.

Proposition 4.5

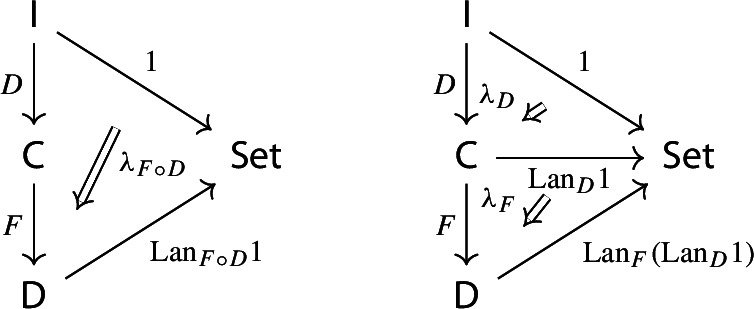

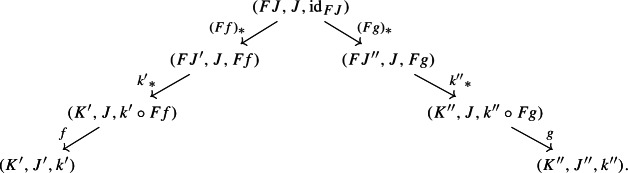

Let , , and be categories, and let , , be functors. The left Kan extensions and are naturally isomorphic.

Proof

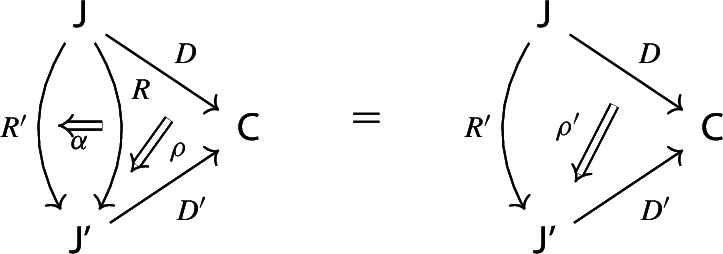

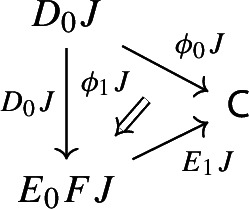

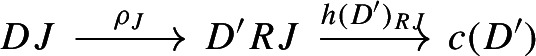

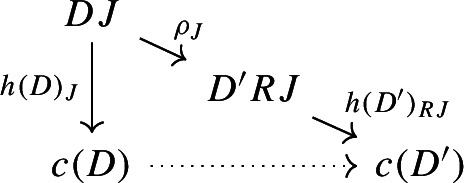

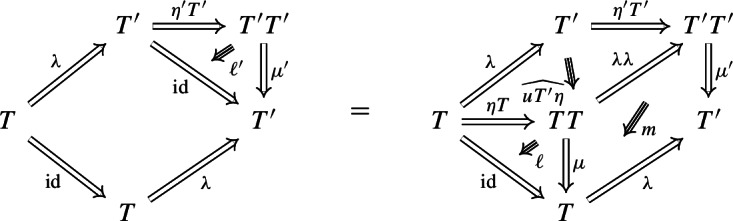

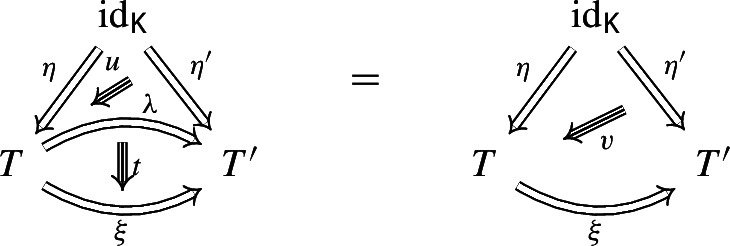

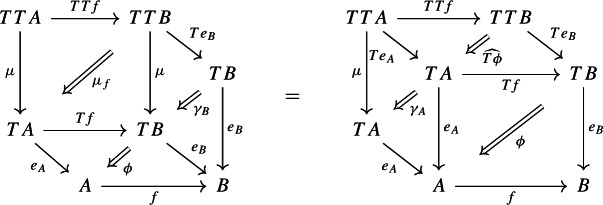

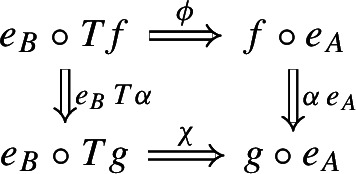

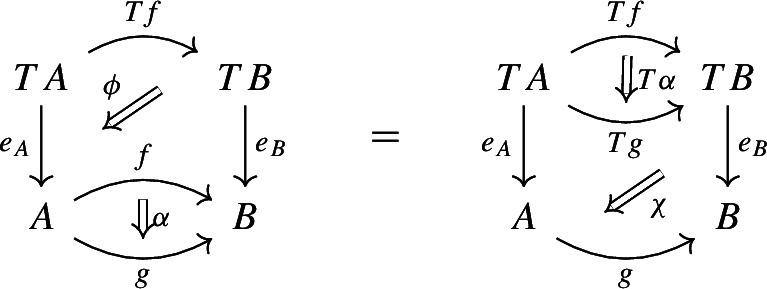

By the universal property of , the natural transformation on the right of (4.1) factors uniquely through , i.e. there exists a unique 2-cell such that the following 2-cells are equal.  Moreover, by the universal property of , the natural transformation factors uniquely through , meaning that there exists a unique natural transformation such that the following 2-cells are equal,

Moreover, by the universal property of , the natural transformation factors uniquely through , meaning that there exists a unique natural transformation such that the following 2-cells are equal,  where the unlabeled arrow (for reasons of space) denotes . We now show that is an isomorphism, by providing an inverse. By the universal property of , the composite natural transformation on the left of (4.1) factors uniquely through , meaning that there exists a unique natural transformation such that the following 2-cells are equal.

where the unlabeled arrow (for reasons of space) denotes . We now show that is an isomorphism, by providing an inverse. By the universal property of , the composite natural transformation on the left of (4.1) factors uniquely through , meaning that there exists a unique natural transformation such that the following 2-cells are equal.  where this time the unlabeled arrow denotes . By the universal properties of the respective Kan extensions, we then have that has to be the identity natural transformation at , and has to be the identity natural transformation at .

where this time the unlabeled arrow denotes . By the universal properties of the respective Kan extensions, we then have that has to be the identity natural transformation at , and has to be the identity natural transformation at .

Corollary 4.6

Pushforwards of small presheaves exist, are given by pointwise left Kan extensions, and are small.

Remark 4.7

Since we are dealing with pointwise Kan extensions, we can also express this vertical pasting law in terms of coends, where it is an instance of the co-Yoneda lemma (Proposition 4.3). In particular, let and be locally small categories, let be a functor, and let be a small presheaf. Then

Let moreover be locally small, and be a functor. Then

where the middle isomorphism, which in the proof Proposition 4.5 was denoted by , is given by the co-Yoneda lemma.

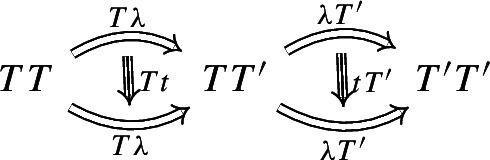

Now, given , we have a (chosen) mapping . For to be a pseudofunctor, we first of all need to be a functor. To this end, let be a natural transformation between small presheaves on . By the universal property of as a Kan extension, there is a unique 2-cell , which we denote by , which makes the following 2-cells equal.  This makes a functor , where functoriality holds by uniqueness of the cell . Uniqueness of such cell holds once a choice of has been made. (One can obtain this 2-cell also using the pointwise characterization of as a coend.)

This makes a functor , where functoriality holds by uniqueness of the cell . Uniqueness of such cell holds once a choice of has been made. (One can obtain this 2-cell also using the pointwise characterization of as a coend.)

Unitor and Compositor

The left Kan extension of along the identity functor is naturally isomorphic to P itself, and this isomorphism is natural in P as well. In other words, is naturally isomorphic to . Since we are free to choose within its isomorphism class, we can in particular pick , so that the unitor of our pseudofunctor is the identity (one speaks of a normal pseudofunctor).

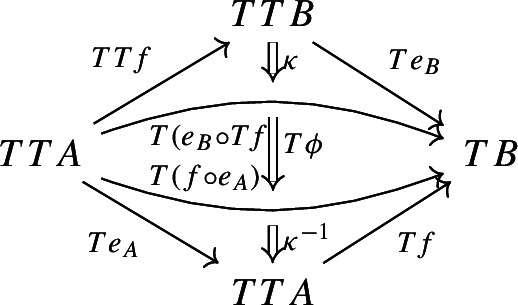

With composition, the matters are not so simple. By Proposition 4.5, or by Remark 4.7, we know that Kan extensions preserve compositions up to a specified natural isomorphism, which we had denoted by . In general we cannot assume that is the identity, we cannot make that choice consistently across the whole category. However, we can show that satisfies all the properties of a compositor, and so it makes pseudofunctorial.

As in Remark 4.7, let , and be locally small categories, and let and be functors. Let moreover P be a small presheaf on . The isomorphism of given by the co-Yoneda lemma, as in Remark 4.7, is (strictly) natural in P, in F, and in G, by the universal property of coends.

In order to have pseudofunctoriality it remains to be shown that the compositor is associative and unital. Unitality is guaranteed by our choice of unitor (identities), we now prove associativity.

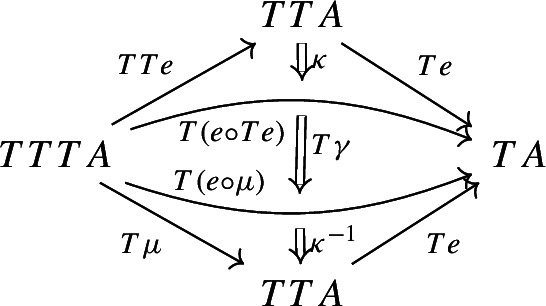

Proposition 4.8

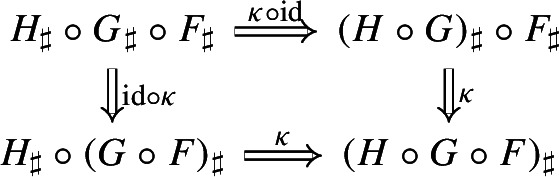

The following “associativity” diagram commutes for all locally small categories , , and and functors , and .

One could again invoke the co-Yoneda lemma, but it may be instructive to give a proof by explicitly pasting Kan extensions vertically. For simplicity, we equivalently prove the statement in terms of the inverse .

Proof

Let P be a small presheaf on . By iterating (4.2), both composite cells  are equal to the following composition.

are equal to the following composition.  By the universal property of as a Kan extension, then, the two composite 2-cells are equal.

By the universal property of as a Kan extension, then, the two composite 2-cells are equal.

This proves that is a pseudofunctor .

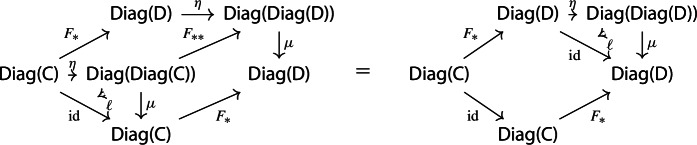

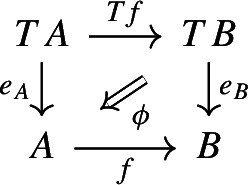

Naturality of the Image

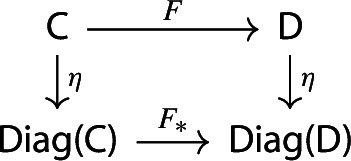

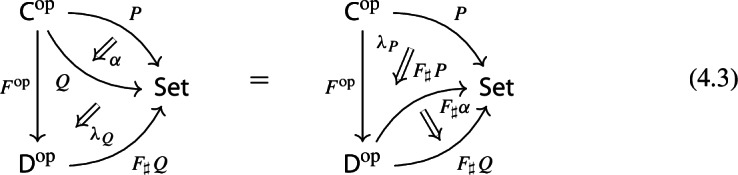

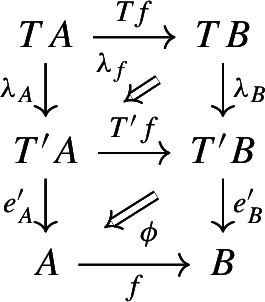

Consider a functor between locally small categories, and let be a (small) diagram in . One can either form the image presheaf of D and then push it forward along F, or one can first form the diagram , and then take the image presheaf. As we will see shortly, the result is the same, up to coherent isomorphism.

Proposition 4.9

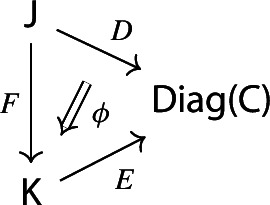

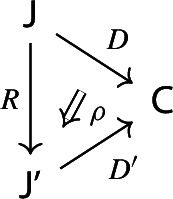

The functors form a pseudonatural transformation .

Proof

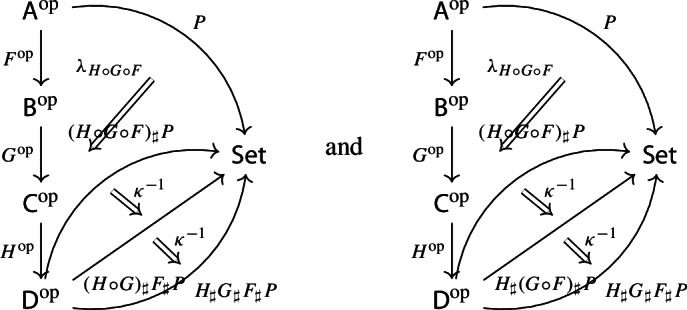

First of all, for each functor of we need a natural isomorphism in the following form.  Let now be a small diagram. Using the definition of image in terms of Kan extensions, the two routes of Equation (4.4) are given by the following Kan extensions, respectively,

Let now be a small diagram. Using the definition of image in terms of Kan extensions, the two routes of Equation (4.4) are given by the following Kan extensions, respectively,  which we know are naturally isomorphic via the map of Proposition 4.5 and Sect. 4.2.1, which is also natural both in D and in F. The unit and multiplication conditions correspond to the unitality and associativity condition for .

which we know are naturally isomorphic via the map of Proposition 4.5 and Sect. 4.2.1, which is also natural both in D and in F. The unit and multiplication conditions correspond to the unitality and associativity condition for .

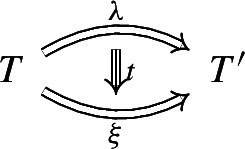

Unit and Multiplication

The Unit: the Yoneda Embedding

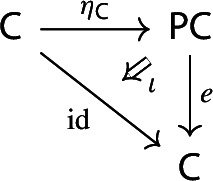

Let be a locally small category. By Proposition 3.12, the Yoneda embedding lands in : representable presheaves are small. We denote again by the functor induced by the Yoneda embedding . When this causes confusion because both monads and are present, we will denote the two units by and .

Proposition 4.10

The unit is canonically pseudonatural in .

Proof

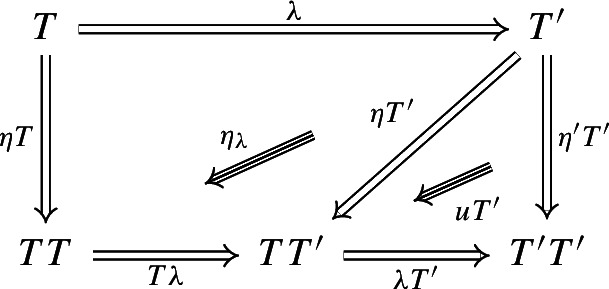

Let and be locally small, and let be a functor. We have to prove that the following diagram commutes up to coherent isomorphism.  In practice, using the coend description of (via Kan extensions), this amounts to a natural isomorphism of presheaves,

In practice, using the coend description of (via Kan extensions), this amounts to a natural isomorphism of presheaves,

which is given by the co-Yoneda lemma (Proposition 4.3), by setting . In particular, the isomorphism is given pointwise, for each object D of by mapping to the equivalence class of . It can be checked that, defined this way, the isomorphism respects identities and composition.

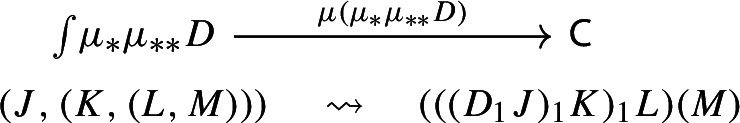

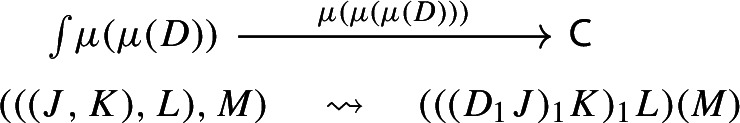

The Multiplication: Free Weighted Colimits

Let’s now turn to the multiplication of the monad. One could define it as the left-adjoint to the unit, since the monad turns out to be lax idempotent (a.k.a. Kock-Zöberlein). Here, instead, we define the multiplication directly.

Definition 4.11

Let be locally small, and let be an object of (i.e. a small presheaf on small presheaves). We define as the object of specified, up to isomorphism, by the following “free weighted colimit”,

for each object C of .

Remark 4.12

By functoriality of colimits, is a presheaf . Since PC is in general not small, let’s show why the coend exists. Since is small, there exists a small diagram such that . In other words,

which by Fubini and by the co-Yoneda lemma (Proposition 4.3) is naturally isomorphic to

This coend exists, since it is a coend in indexed by a small category, and it gives a small presheaf (since is cocomplete).

Therefore is a functor (as usual, defined up to natural isomorphism).

Proposition 4.13

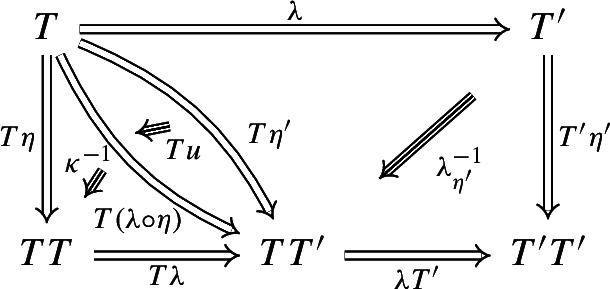

The functor is pseudonatural in the category .

Proof

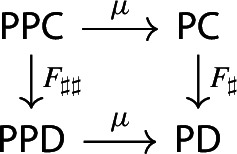

We have to prove that the following diagram commutes up to coherent natural isomorphism.  Given , the top right path gives the presheaf

Given , the top right path gives the presheaf

which (by Fubini) is isomorphic to

| 4.5 |

The bottom left path gives the presheaf

which by the co-Yoneda lemma (Proposition 4.3) is isomorphic to (4.5). One can check that this isomorphism respects identities and composition.

Unitors, Associators, Coherence

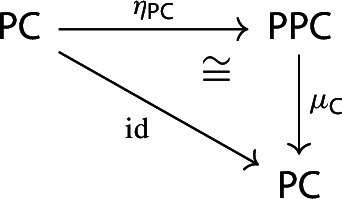

The left unitor  is given as follows. Starting with a presheaf P in , we can apply the unit to get the following representable presheaf on ,

is given as follows. Starting with a presheaf P in , we can apply the unit to get the following representable presheaf on ,

and then, applying the multiplication, we get the following presheaf,

where the last isomorphism, filling the diagram above, is given by the co-Yoneda lemma (Proposition 4.3), and defines the left unitor . Naturality in P follows from naturality of the co-Yoneda isomorphism. The modification property for against functors is again an instance of the coherence of colimits (uniqueness of the isomorphism), just as in Sect. 2.5.3 and Proposition 4.8, this time for weighted colimits.

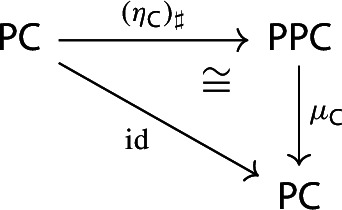

The right unitor  is given as follows. Again start with a presheaf P in . This time we apply the map , to get the following presheaf.

is given as follows. Again start with a presheaf P in . This time we apply the map , to get the following presheaf.

(Note that we cannot apply the Yoneda lemma to simplify the expression on the right.) We now apply the multiplication again, to obtain

where both isomorphisms are given again by the co-Yoneda lemma (Proposition 4.3). This gives the right unitor r, and the reason why it’s a modification is analogous to the one for the left unitor .

The associator  is again an instance of the co-Yoneda lemma (Proposition 4.3). Namely, given , the top-right path of the diagram gives the following presheaf

is again an instance of the co-Yoneda lemma (Proposition 4.3). Namely, given , the top-right path of the diagram gives the following presheaf

while the bottom-left path gives the following,

and the two differ by one application of the co-Yoneda lemma (over P). This gives the associator a, which is a modification for reasons analogous to the above.

Again, the higher coherence conditions hold by the uniqueness of isomorphisms given by the universal property, as in Sect. 2.5.3.

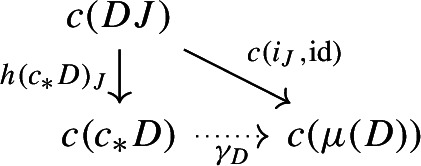

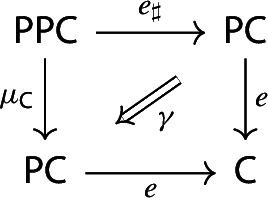

Algebras